Abstract

A survey of Emergency Department (ED) clinicians (ie, physicians, nurses and clinical assistants) at a single hospital in Honolulu, Hawai‘i was conducted to assess the frequency of errors in charting, and entering orders on the wrong patient's chart in the electronic medical record (EMR), and clinician opinion was sought on whether a simple watermark of the patient's room number might help reduce the number of these EMR “wrong patient errors.” ED clinicians (68 total surveys) were asked if and how often they charted in the wrong patient's chart or entered an order (physicians only) in the wrong patient's chart. Physicians had a combined self-reported average error rate of 1.3%. Mean rate of patient charting errors occurred at 0.5 errors and 0.4 errors per 100 hours, for nurses and clinical assistants, respectively. The majority (81%) of the 68 clinicians surveyed felt that a room number watermark would eliminate most of the wrong patient errors. In conclusion, charting on the wrong patient and order entry on the wrong patient type errors occur with varying frequencies amongst ED clinicians. Nearly all the clinicians believe that a room number watermark might be an effective strategy to reduce these errors.

Introduction

Electronic medical records (EMRs) are becoming more common throughout medical systems.1–7 Each medical system and its services and departments have user displays and interfaces optimized for their specific needs. The hospital in which the present study was undertaken has used the Epic EMR (Epic Systems Corporation, Verona, WI) since November 2008 for charting and computerized physician order entry (CPOE). It has also utilized a computer-linked automated drug dispensing unit coupled to a triple scan system in which the patient's ID band code, the medication bar code, and the nurse's ID badge are electronically scanned to confirm that medication is being given to the correct patient. The Epic EMR has a special interface for the Emergency Department (ED). The unique aspects of ED patient care work flow include the following features:8,9

A large proportion of ED patients are new patients, or are presenting with new problems.

ED patients typically have a short length of stay.

A given room in the ED is serially assigned to approximately 5 to 20 patients during a 24 hour period (ie, rapid turnover).

Most ED patients are discharged to home, but some are hospitalized.

ED physicians and nurses manage several patients simultaneously.

Because of these factors, clinicians managing ED patients do not have the opportunity to get to know patients well by name. Most of the time spent with the patient is in acquiring their medical history, their physical exam findings, and carrying out diagnostic and treatment measures. In the ED, time limitation prioritizes medical information over getting to know patients socially and personally. Because of this, accurate identification of patients by ED clinical staff frequently relies on the patient's room number. However, the patient's name, and not his or her room number, is prominently displayed in the identification portion of the patient's chart (paper or EMR).

The room number layout in the ED is constant and well known to clinicians in the ED. A room number instantly identifies a patient, and is routinely used in place of name for communication about patients. For example, clinical staff may state: ”[The patient in] 6 needs to be taken to X-ray,” or “Is it OK for [the patient in] 2B to start drinking fluids now?” or “Can you please call respiratory therapy for [the patient in] 5B?” or “[The patient in] 9 is ready for discharge.” To hasten communication, the text in brackets is often left out. Therefore, ED staff knows the patient's clinical issues based on their room number. The patient's name is primarily used only when communicating with the patients and family directly or during other processes such as consent, procedure time-outs, medication administration, etc.

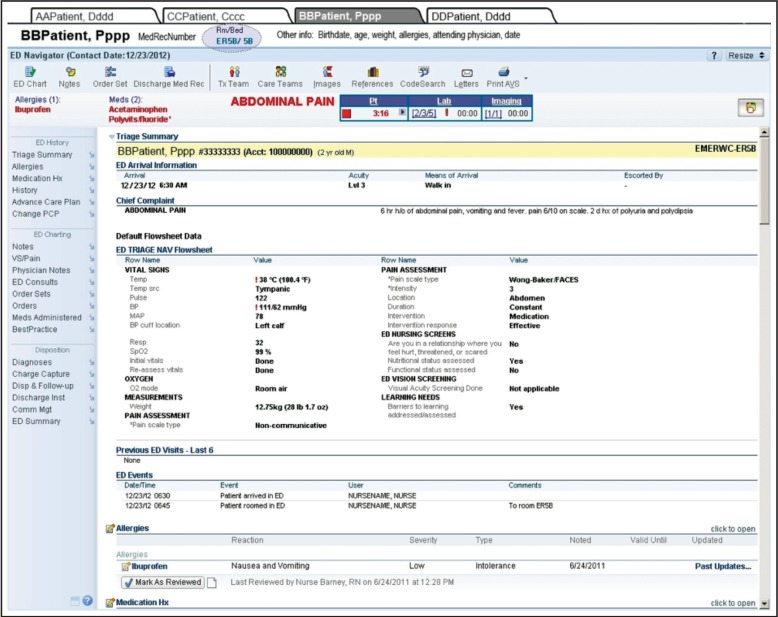

The ED track board is a tool which displays all the patients in the ED in real time (Figure 1). It is one of the main screens that is displayed on the user's screen. A de-identified version is also displayed on a large screen centrally within the ED nurse station. Because of this heavy reliance on the patient's room number, the display of the room number in the track board and other parts of the EMR is critical to the proper identification of ED patients.

Figure 1.

ED EMR trackboard (portion of screen). © 2013 Epic Systems Corporation.

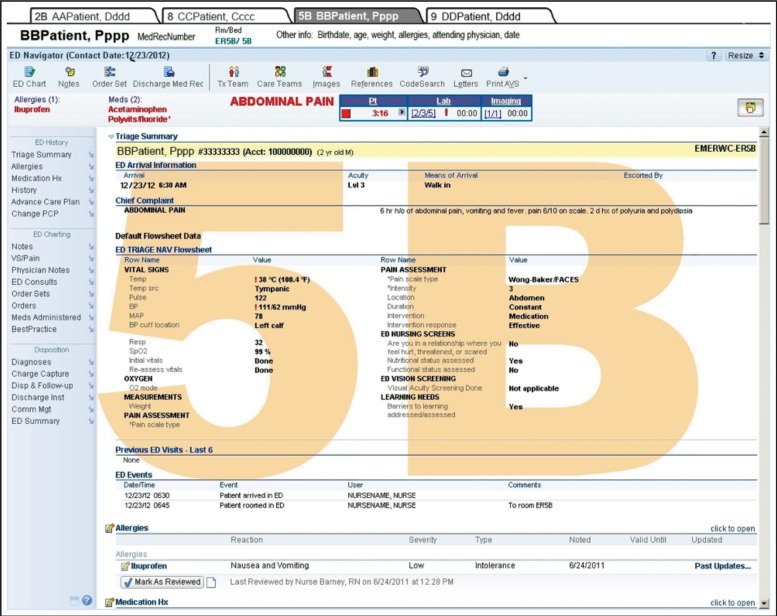

In the Epic EMR system, charting on patients and order entry are done by clicking a patient's row on the trackboard to open a full screen display of the patient's record, nested within a tab. In the Figure 2 screen shot, a maximum of 4 tabs that can be opened at any given time are displayed with charts of four fictitious patients (AAPatient, CCPatient, BBPatient, and DDPatient). In Figure 2, the active tab is that of BBPatient. While there are several indicators here that the patient tab that is open is BBPatient, the room number is fairly small (turquoise font in the upper left), and has been circled in Figure 2 for demonstrative purposes only. A clinician must click on the notes item or icon to enter a chart note. A clinician must click on Order Set or Orders to enter orders.

Figure 2.

Sample patient encounter screen. © 2013 Epic Systems Corporation.

When viewing the ED as a whole to get a perspective on task prioritization, the clinician views the track board (Figure 1). To enter a note or an order in BBPatient's chart, the clinician must double click on the track board line 5B to open the patient's tab. From the authors' personal experience, it is common for clinicians to double click on 5B and assume that the tab that is opened is the correct patient in 5B. However, the wrong tab can occasionally open. For example, the clinician may intend to open 5B, but open up 5A instead. Figure 2 demonstrates the potential for this error since, although the patient's name is prominently displayed, the room number is less readable. If the physician relied on the name, this would not be a problem; however, since it is common to rely on the room number, the small font size makes it difficult to spot this error. Note that the other 3 tabs (Figure 2) have the patient names only (without the room number).

Opening the wrong patient tab has several consequences. First, the patient information may be entered into the wrong chart. As a result, incorrect patient information is now visible to someone viewing a different chart. While incorrect entries may be erased, Epic does not permit users to permanently delete the wrong entry. Rather it stores the information as “deleted” in the wrong chart, which makes it potentially viewable (medical information in wrong chart). Next, orders may be entered on the wrong patient. Nursing, pharmacy, imaging, and respiratory therapy staff are able to catch some or most of these errors. However, errors may persist, and medications may be dispensed and charged to the wrong patient. Ultimately, the potential exists for medications to be administered to the wrong patient. As long as the error is caught, dangerous mistakes can be avoided; however, finding and rectifying errors is very time consuming for the staff; the impact on the patient could range from a mere inconvenience at best to life-threatening consequences.

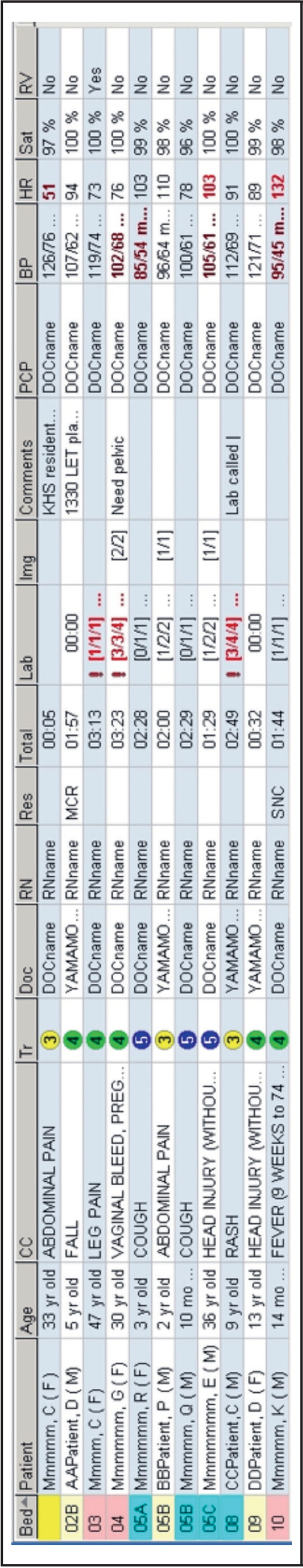

Implementing systems that prevent these errors is therefore critical. With the current Epic trackboard and patient tab layout, these errors continue to occur. The hypothesis of this study was that these errors can be reduced by displaying the room number on the EMR screen, as shown in the Figure 3 sample patient screen. The proposed change is a colored transparent watermark that does not block any information. As the screen scrolls up and down or different screen information is displayed, the watermark remains fixed as long as the information pertains to the patient in that room. The inclusion of the watermark makes it quite obvious that one is viewing the chart of the patient in 5B. A clinician making a chart entry or entering orders would be more likely to notice the patient's room number, potentially increasing the likelihood of avoiding a wrong patient error. A less noticeable proposed change in Figure 3 is that the four tabs at the top also have the patient's room numbers next to the patient's name. This permits the clinician to click on these tabs directly.

Figure 3.

Sample patient encounter screen. (© 2013 Epic Systems Corporation) with room number watermark (overlay).

The purpose of this study was to survey ED clinicians in a single hospital in Hawai‘i on the frequency of self-reported charting and order entry errors (“wrong patient errors”) and to assess whether they believed that a simple watermark of the patient's room number might reduce the number of EMR wrong patient errors.

Methods

During calendar year 2012, attending general emergency physicians, attending pediatric emergency physicians, ED nurses, and ED clinical assistants were asked in person to participate in a voluntary survey as a study subject. Participant responses were collected in person by the study investigator after verbal consent was obtained. This study protocol was determined to be exempt from regulations for category 2 research using the guidelines set by the Office of Human Research Protection (45 CFR 46.101(b)) by a designee of the Institutional Official of the hospital system.

The survey recorded the number of years of clinical experience of the study subjects. Nurses and clinical assistants were asked to approximate the number of hours worked during the previous 3 months. Physicians were asked to approximate the number of patient encounters during the previous 3 months. The different responsibilities of the physicians, nurses, and clinical assistants required the protocol to assess errors within their scope of respective responsibilities. The survey asked study subjects if they had ever made an error in which charting or order entry (physicians only) was done in the wrong patient's chart. The survey then asked study subjects for an approximate number of times this occurred in the last 3 months. Nurses were also asked if they noticed an ordering error (made by the physician) on the wrong patient's chart and to approximate the number of times this occurred in the last 3 months.

A charting error was defined as key stroke into a note on the wrong patient's chart, even if the error was then discovered immediately and the note was purged. An ordering error was defined as entering an order on the wrong patient even if it was discovered immediately and the order was cancelled. Ordering error counts were defined in terms of episodes rather than the actual number of orders. For example, if a physician ordered three medications on the wrong patient at the same time, this was considered to be one error episode.

Study subjects were then shown the standard EMR screen (what they normally see) (Figure 2), then an identical EMR screen with room number watermarks added to the patient chart and tabs, as depicted in Figure 3. In addition, a verbal description of how the two screens differed was provided. Subjects were asked if they thought that the addition of the room number watermark and the room number on the tabs (Figure 3) could potentially reduce the number of wrong patient charting/ordering errors. If they responded yes, then they were asked whether they thought this would eliminate just a few, roughly half, or most of the errors.

Data from each study subject survey form was manually entered into a spreadsheet (Microsoft Excel, Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA). Descriptive statistics were tabulated using the built-in functions of the spreadsheet.

Results

The results are tabulated in Table 1; 100% of those who were approached consented to participate in the study. Of the 68 clinician study subjects who completed the survey, all but two (both were clinical assistants) had made a wrong patient charting or ordering error. Six (25%) of 24 physicians reported never making a wrong patient charting error, but 100% noted one or more wrong patient ordering errors (although not necessarily in the most recent 3 month study period). The highest numbers of wrong patient errors reported by physicians were 6.7, 10, 13.3, and 20 errors per month, respectively (one physician each) during the previous 3 month period. Other than these four physicians, total physician errors in the previous 3 months ranged from zero to 3.3 errors per month. Overall, the 3 month self-reported mean error rate was 4.8 per month (median: 1.7 errors per month). Total nurse errors ranged from zero to 1.7 errors per month in the past 3 months (zero to 2.8 errors per 100 hours). Most (97%) of the 31 nurses reported noticing wrong patient ordering errors by physicians, with observed error rates ranging from zero to 3.3 errors per month during the past 3 months (zero to 2.1 errors per 100 hours). Total 3-month error rates among clinical assistants also ranged from zero to 3.3 errors per month with a mean of 0.9 errors per month (median: 0.7 errors per month).

Table 1.

Clinical experience, EMR experience, wrong patient error frequency and error reduction opinions amongst emergency physicians (EPs), nurses (RNs), and clinical assistants (CAs). SD = standard deviation. *ordering errors do not apply to RNs or CAs.

| Emergency Physicians (EP) | Nurses (RN) | Clinical Assistants (CA) | |

| n | 24 | 31 | 13 |

| Years of total clinical experience in this position (mean +/− SD) | 11.1 ±/− 10.6 | 9.1 ±/− 9.9 | 4.5 ±/− 3.2 |

| <1 year | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 to <=5 years | 7 | 17 | 8 |

| >5 to <=10 years | 6 | 4 | 3 |

| >10 years | 9 | 9 | 1 |

| Years of experience using Epic ED EMR (mean ±/− SD) | 2.5 ±/− 1.1 | 2.6 ±/− 1.0 | 2.2 ±/− 1.3 |

| <1 year | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| 1 to <=2 years | 5 | 5 | 1 |

| >2 years | 15 | 23 | 8 |

| Mean activity level (patients for EP, hours for RN/CA) for most recent 3 months (mean ±/− SD) | 780 + 287 patients | 423 + 112 hours | 447 + 58 hours |

| Ever made a wrong patient charting or ordering* error? | yes=24, no=0 | yes=31, no=0 | yes=11, no=2 |

| How many errors in most recent 3 months ? (mean ±/− SD) | 9.5 ±/−14.4 | 1.9 ±/− 1.3 | 2.6 ±/− 2.7 |

| RNs only: Ever noticed a wrong patient ordering error? | yes=30, no=1 | ||

| How many times in most recent 3 months ? (mean ±/− SD) | 2.7 ±/− 2.3 | ||

| Do you think the EMR room number watermark will reduce wrong patient errors? | yes=23, no=1 | yes=31, no=0 | yes=13, no=0 |

| If yes to above question, how many wrong patient errors would be eliminated? | |||

| Just a few errors would be eliminated | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (8%) |

| About half the errors would be eliminated | 5 (22%) | 3 (10%) | 2 (15%) |

| Most of the errors would be eliminated | 17 (74%) | 28 (90%) | 10 (77%) |

Using the estimated number of patient encounters during the previous 3 months, physicians made wrong patient charting or ordering errors ranging from 0 to 8.6 per 100 patients (0% to 8.6%). The mean error rate of 1.3% was calculated as the mean of the individual error rates or 1.2% calculated as total errors divided by total number of patients seen by the 24 physicians. Extrapolating this to the 40,000 patients seen annually in the ED where the study was conducted,10 a 1.3% estimated error rate suggests that there may be approximately 520 wrong patient charting or ordering errors made annually by physicians.

Using the estimated number of hours worked during the previous 3 months, nurses made wrong patient charting errors ranging from 0 to 2.8 (mean 0.5, median 0.43) per 100 hours, and clinical assistants made wrong patient charting errors ranging from 0 to 2.3 (mean 0.57, median 0.43) per 100 hours. Nurses noted wrong patient ordering errors (by physicians) during the previous three months ranging from 0 to 2.1 (mean 0.66, median 0.46) per 100 hours.

Of the 68 clinician study subjects surveyed, all except one felt that the room number watermark would reduce the number of wrong patient errors. The majority (81%) of the 68 clinicians surveyed felt that the room number watermark would eliminate most of the wrong patient errors.

Discussion

In a 2005 study of CPOE, more than 50% of physician providers made order entry errors because they were not able to quickly identify the patient because of a poor CPOE display.11 In a 2006 study of retrospectively identified pediatric medication errors related to CPOE, wrong patient type of error was not found to be common.12 Our study surveyed attending clinicians in an ED, did not include residents, and defined “errors” differently; it was limited to attending physicians, and not residents, because attending physicians have greater patient responsibility than residents, and greater experience with the ED work flow, ordering schemes, the specific ED features of Epic, and the trackboard view available to ED staff. Our study indicated that nearly 100% of clinicians made wrong patient EMR errors (charting and ordering) at some point with an average of 9.5 errors in the past 3 months suggesting that these errors are common.

The findings of this study confirm that ED clinicians who are routine users of the system believe that improving the information display in a way that heightens awareness of the most commonly utilized ED patient identifier (the room number) would be an effective means of reducing wrong patient errors. The room number watermark can be built into the EMR to display automatically and passively without clinician intervention. Other options to enlarge the room number would reduce the available screen display area, whereas the watermark method makes the room number very prominent without compromising screen display availability. In doing so, it could save time by avoiding the need to undo the error and then to repeat the task in the correct patient's chart.

A 2012 children's hospital study confirmed that patient identification error events occurred, though their numbers were small. The authors utilized a photographic image of the patient displayed in all order entry screens to reduce the number of wrong patient orders.13 This is a similar concept to the room number watermark in that it provides a passive display to confirm that the clinician is ordering or charting on the correct patient. Acquiring a picture image takes some time and it must be linked to the correct patient (which itself has potential for error). While this is feasible for inpatients, it may not be feasible for the faster patient throughput and workflow of an ED. The room number watermark takes up no additional viewing space on the computer display and it can be automated with no special user intervention.

A room number watermark may reduce wrong patient errors by providing a second identifier check. The administration of medication and performing a procedure at the bedside requires an identification process to review the patient's identification band with at least two patient identifiers. However, this identification verification is not stressed for the charting or the order entry process. One study confirmed that providers do not verify patient identity during computer order entry.14 In place of these established verification systems, the inclusion of the patient's picture or the patient's room number in the EMR would serve as an appropriate secondary identifier. Neither are infallible but they provide secondary confirmation that is fast, automated, and passively effective.

Another study by Adelman, et al, demonstrated that identification confirmation/verification during the order entry process was effective in reducing wrong patient errors.15 However, identification verification during order entry takes additional time; moreover, wrong patient errors occur in the charting function in addition to the order entry function, creating the need for additional identification confirmation/verification. It would be better if this can be done in a more passive and automated fashion without the additional burden on the clinician, which may be accomplished by a room number watermark.

While some checks exist in our current system, it would be far better to employ a technologically incorporated passive strategy (such as a room number watermark) that prevents these errors in the first place. In the opinion of nearly all the clinicians surveyed in this study, a room number watermark had the potential to reduce these errors.

Limitations of This Study

Wrong patient errors could have been theoretically estimated by examining keystrokes, order cancelations, note deletions, and related modifications that could suggest a “wrong patient” error. This would require each cancelation, deletion, and modification to be identified by the information technology (IT) staff, and then reviewed to determine if the change could be attributed to wrong patient error. The complexity of the task, and its inherent flaws led the author to choose an alternative strategy for the study. A survey asking each clinician to estimate the number of errors is subjective and it is potentially embarrassing to admit that errors were made. Thus, it is likely that the study underestimated the incidence of wrong patient errors. We did ask the survey participants to be honest. We pointed out that the survey was anonymous, the information was not shared with anyone, and that this information could not be used for anything related to employment purposes. The study was unable to identify errors that went unnoticed, providing another reason why it may have underestimated these errors.

A study with a watermark versus control group would have been better, but it was not possible to change the actual EMR screens for the purpose of this study. A simulation would not sufficiently mimic the actual ED work flow and patient encounters. Thus, the next best thing was to use a survey method by asking the ED providers about these errors. Emergency clinicians know and admit that the errors are attributable only in part to a poor information display, as confirmed by other studies. Hence, this study does not demonstrate that these errors can be reduced by a room number watermark; rather only that nearly all the clinicians in this survey who work in the field believe that this might be an effective error reduction strategy.

Conclusion

In conclusion, charting on the wrong patient and order entry on the wrong patient type errors are relatively common and occur with varying frequencies amongst ED clinicians. Nearly all the clinicians believe that a room number watermark might be an effective strategy to reduce these errors.

Conflict of Interest

The author reports no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Ward MJ, Landman AB, Case K, Berthelot J, Pilgrim RL, Pines JM. The effect of electronic health record implementation on community emergency department operational measures of performance. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;63(6):723–730. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2013.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ward MJ, Froehle CM, Hart KW, Collins SP, Lindsell CJ. Transient and sustained changes in operational performance, patient evaluation, and medication administration during electronic health record implementation in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;6(3):320–328. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2013.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perry JJ, Sutherland J, Symington C, Dorland K, Mansour M, Stiell IG. Assessment of the impact on time to complete medical record using an electronic medical record versus a paper record on emergency department patients: a study. Emerg Med J. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2013-202479. Pbulished Online First: 23 Aug 2013 [I cannot find it in the actual journal yet. PDF document instructs readers to cite the article as above] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dexheimer JW, Kennebeck S. Modifications and integration of the electronic tracking board in a pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2013;29(7):852–857. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e31829ba7ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park SY, Lee SY, Chen Y. The effects of EMR deployment on doctors' work practices: a qualitative study in the emergency department of a teaching hospital. Int J Med Inform. 2012;81(3):204–217. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones SS, Adams JL, Schneider EC, Ringel JS, McGlynn EA. Electronic health record adoption and quality improvement in US hospitals. Am J Mang Care. 2010;16(12 Suppl HIT):SP64-71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bukata WR. Electronic Health Records - Where's the Beef? Emergency Medicine and Acute Care Essays. 2011;35(2):1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamamoto LG, Khan ANGA. Challenges of Electronic Medical Record Implementation in the Emergency Department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2006;22(3):184–191. doi: 10.1097/01.pec.0000203821.02045.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khan A. Chapter 153. Electronic Medical Record. In: Schafermeyer RW, Tenenbein M, Macias GC, Sharieff G, Yamamoto LG, editors. Strange and Schafermeyer's Pediatric Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. Fourth Edition. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical; 2014. pp. 824–829. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kapi‘olani Medical Center For Women & Children medical staff statistics.

- 11.Walsh KE, Adams WG, Bauchner H, Vinci RJ, Chessare JB, Cooper MR, Hebert PM, Schainker EG, Landrigan CP. Medication Errors Related to Computerized Order Entry for Children. Pediatrics. 2006;118(5):1872–1879. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koppel R, Metlay JP, Cohen A, Abaluck B, Localio AR, Kimmel SE, Strom BL. Role of Computerized Physician Order Entry Systems in Facilitating Medication Errors. JAMA. 2005;293(10):1197–203. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.10.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hyman D, Laire M, Redmond D, Kaplan DW. The Use of Patient Pictures and Verification Screens to Reduce Computerized Provider Order Entry Errors. Pediatrics. 2012;130(1):e211–e219. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henneman PL, Fisher DL, Henneman EA, Pham TA, Mei YY, Talati R, Nathanson BH, Roche J. Providers do not verify patient identity during computer order entry. Acad Emerg Med. 2008 Jul;15(7):641–648. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adelman JS, Kalkut GE, Schechter CB, Weiss JM, Berger MA, Reissman SH, Cohen HW, Lorenzen SJ, Burack DA, Southern WN. Understanding and Preventing Wrong-Patient Electronic Orders: a Randomized Controlled Trial. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2013;20(2):305–310. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2012-001055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]