Abstract

Paraprofessional home visitors trained to improve multiple outcomes (HIV, alcohol, infant health, and malnutrition) have been shown to benefit mothers and children over 18 months in a cluster randomised controlled trial (RCT). These longitudinal analyses examine the mechanisms which influence child outcomes at 18 months post-birth in Cape Town, South Africa. The results were evaluated using structural equation modelling, specifically examining the mediating effects of prior maternal behaviours and a home visiting intervention post-birth. Twelve matched pairs of neighbourhoods were randomised within pairs to: 1) the control condition, receiving comprehensive healthcare at community primary health care clinics (n=12 neighbourhoods; n=594 pregnant women), or 2) the Philani Intervention Program, which provided home visits by trained, paraprofessional community health workers, here called Mentor Mothers, in addition to clinic care (n=12 neighbourhoods; n=644 pregnant women). Recruitment of all pregnant neighbourhood women was high (98%) with 88% reassessed at six months and 84% at 18 months. Infants’ growth and diarrhoea episodes were examined at 18 months in response to the intervention condition, breastfeeding, alcohol use, social support, and low birth weight, controlling for HIV status and previous history of risk. We found that randomisation to the intervention was associated with a significantly lower number of recent diarrhoea episodes and increased rates and duration of breastfeeding. Across both the intervention and control conditions, mothers who used alcohol during pregnancy and had low birth weight infants were significantly less likely to have infants with normal growth patterns, whereas social support was associated with better growth. HIV-infection was significantly associated with poor growth and less breastfeeding. Women with more risk factors had significantly smaller social support networks. The relationships among initial and sustained maternal risk behaviours and the buffering impact of home visits and social support are demonstrated in these analyses.

Keywords: infant diarrhoea, HIV, perinatal health, home visitors

Introduction

Reducing child mortality and improving child health, Millennium Development Goal Number 4, is unlikely to be met in South Africa by 2015 (Bryce, Gilroy, Jones, Black, and Victoria, 2010). Having a low birth weight infant (< 2500 grams; LBW), slow growth (either stunting or malnutrition), and repeat bouts of diarrhoea are the primary causes of negative child outcomes in the first years of life (Black et al., 2010; Hayes & Sharif, 2009). This article aims to explore factors associated with improving these child outcomes in South Africa, including the provision of a home visiting intervention by paraprofessionals.

Infants’ birth weight and early growth impacts their lifelong health, especially for the 200 million children living in poverty in low and middle income countries (LMIC; Grantham-McGreggor, 2007; Walker et al., 2007). Even when rehabilitated, children remain at risk for deficits in normal growth and development (Aarnoudse-Moens, Weisglas-Kuperus, van Goudoever, & Oosterlan, 2009; Eichenwald & Stark, 2008). Children with low birth weights are more likely to be in special education classes at school age (Resnick et al. 1999), to have impaired cognitive functioning and social skills (Hogan and Park, 2000), to be stunted during early childhood, and are at increased risk of obesity in adulthood (Walker et al., 2007; Kimani-Kuragwi, et al., 2010). Stunting in early life is additionally associated with less economic success and lower rates of reproduction in adulthood (Dewey & Begum, 2011).

In South Africa, there are more than 5 million children under the age of four years old (UNICEF, 2007) and 15% – 17% of these infants have a LBW (le Roux et al., 2010), with some less than 1000 kg (Kalimba & Ballott, 2013). About 29% of pregnant women in South Africa are living with HIV (South African Department of Health, 2011), which additionally places infants at risk of being LBW and for slow growth over the first few years of life, even when mothers adhere to antiretroviral treatments to avoid perinatal transmission (Filteau, 2009; MacDonald et al, 2012). Given the large number of children impacted by low birth weight and stunting, interventions to improve these outcomes are critical.

Concurrent with the developmental damage associated with infants’ early growth, diarrhoea is the leading cause of child mortality for children under the age of 5 years (Black et al., 2010; Walker, Lamberti, Adair et al., 2012). Each bout of diarrhoea increases the likelihood of child mortality by a factor of five (Walker et al., 2012). This study reports predictors of having a LBW infant, and, at 18 months, healthy growth in height and weight, and episodes of diarrhoea among infants of Black township women in Cape Town, South Africa. In addition to LBW and HIV, infants are challenged by their mothers’ alcohol use. About 25% of South African mothers use alcohol prior to being aware that they are pregnant (O’Connor et al., 2011) and, without intervention, about 15% continue to use alcohol and even increase their use of alcohol during pregnancy (le Roux et al., 2013). South Africa has reported the highest rates of Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders globally (May et al., 2000). Alcohol use must be considered an additional risk factor for infants’ poor growth and development in South Africa.

The most robust intervention to date for low income, high risk mothers has been the study on nurse home visiting over the first two years of life conducted by Olds and colleagues in the United States (Olds et al. 2004). Early home visiting produces benefits lasting until early adulthood (Olds, Hill, & Rumsey, 1998). When community health workers (CHW) visit at-risk mothers in the U.S, the outcomes are perceived as less robust, compared to nurses (Olds et al., 2002). However, LMIC cannot afford nurses, and the personnel necessary to mount such support and the human resources will be insufficient until at least 2050 (World Health Organization, 2011). Task shifting will be necessary in LMIC from professional to paraprofessional staff if home visiting is to be successfully implemented to address children’s poor health outcomes (Alamo et al. 2012).

One systematic review of the existing replications and adaptations of home visiting programs implemented by community health workers found promising benefits in promoting breastfeeding and reducing child morbidity and mortality (Lewin et al, 2010), while others have been somewhat more equivocal (Peacock, Konrad, Watson, Nickel, & Muhajarine, 2013; Sweet & Appelbaum, 2004). These programmes are usually vertical programmes focussing on one health outcome or one intervention. The Philani intervention is innovative in that it is a generalist model focussing on multiple health-related concerns.

Additional innovations were made in the home visiting model evaluated in this article. First, home visitors were selected who were community role models, that is, positive peer deviants (le Roux, et al., 2011). Second, the CHW were trained in basic strategies to change behaviours (problem solving, goal setting, rewards), as well as in the knowledge of protective care taking to improve health outcomes. Finally, the CHW were routinely supervised and randomly site visited, as well as reporting their visits on mobile phones and paper reports (Rotheram-Borus et al., 2012; Tomlinson, Rotheram-Borus, et al., 2013). These innovations have been found to improve maternal caretaking and infant outcomes over the first 18 months of life in a rigorous intention-to-treat analysis of a cluster RCT (Rotheram-Borus et al., 2011; le Roux et al., 2013). The current analyses uses structural equation modelling to examine the specific predictors and the intervening mediators of children’s poor health outcomes at 18 months (stunting and malnutrition, diarrhoea), controlling specifically for measures of intervening adjustment collected at an assessment at 6 months post-birth, including LBW.

Methods

Participants

At baseline, 24 matched township neighbourhoods outside Cape Town, South Africa, were randomised either to intervention or control groups for the Philani Project. The minimum number of pregnant women needed per neighbourhood to achieve 80% power to detect a standardised effect size of 0.40 set the sample size; the original size was 1 144. From May 2009 to September 2010, 12 township women residing within the two matched townships went house-to-house to identify all adult pregnant women (at least 18 years old) and obtained consent for them to be contacted by the assessment team. Only 2% of pregnant women refused participation. The neighbourhoods and pregnant women were highly similar across conditions. The Institutional Review Boards of University of California Los Angeles (UCLA), Stellenbosch University, and Emory University approved the study, whose methods have previously been published (Rotheram-Borus et al., 2011). Three independent teams conducted the assessment (Stellenbosch), intervention (Philani Project), and data analyses (UCLA).

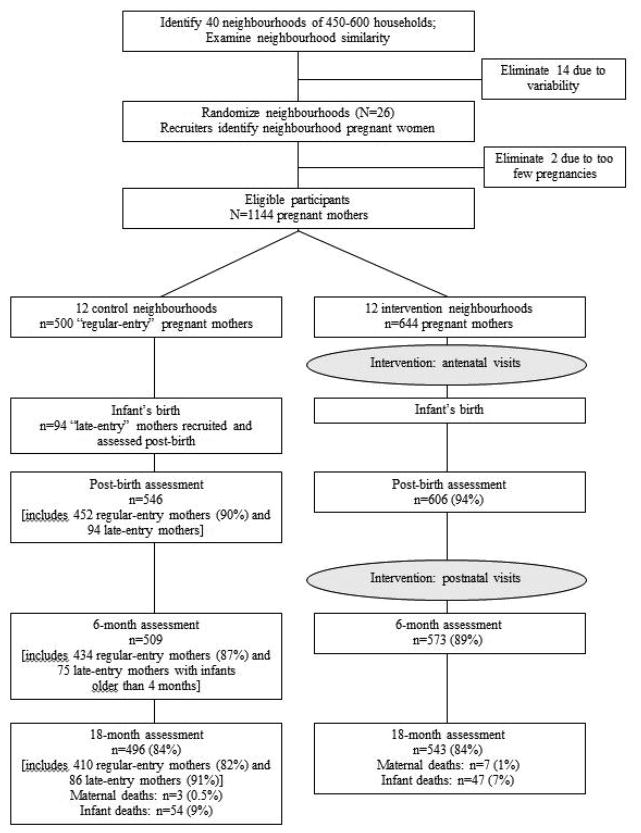

Figure 1 summarises participant flow through the study. Assessments were conducted at baseline, six months (88%; M=6.2 months, SD=0.7); and at 18 months (84%; M=19.1 months; SD=3.0). The current sample size comprising complete data from baseline, 6 months, and 18 months is 874.

Figure 1.

Movement of participants through the trial at each assessment point for mothers in the control and the intervention conditions.

Assessments

We recruited, trained, and certified data collectors to interview participants, entering responses on mobile phones. Interviewers monitored infants’ weight, length, and head circumference, and gathered data from the infant’s government-issued Road-to-Health card when available. Supervisors monitored and gave feedback on the data quality weekly.

Intervention and control conditions

Intervention condition

In addition to standard clinic care described below, CHW (in this programme called Mentor Mothers) provided home visits to participants in the 12 intervention areas. CHW were trained for one month in cognitive-behavioural change strategies and role-playing. They also watched videotapes of common situations that CHW might face. CHW were selected to have good social and problem solving skills having raised healthy children through their own coping skills, and were trained to provide and apply health information about general maternal and child health, HIV/TB, alcohol use, and nutrition to township women. CHW were certified, and supervised biweekly with random observations of home visits.

The Philani Program implemented the intervention. Eight health messages were delivered on HIV/TB, prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT), alcohol, mental health, breastfeeding, and malnutrition. Intervention dose delivered by CHW was monitored on mobile phones that included a time stamp and brief summary visit reports. On average, mothers received 6 antenatal visits (SD=3.8), 5 postnatal visits between birth and 2 months post-birth (SD=1.9), and afterwards about 1.4 visits/month. Sessions lasted on average 31 minutes each.

Control condition

Standard clinic care in Cape Town is accessible, provides TB, HIV and CD4 testing, partner testing, dual regimen therapies for persons living with HIV (PLH), consistent access to milk tins (formula), co-trimoxazole for infants until HIV polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing at 6 weeks, and (inconsistent) postnatal visits at one week.

Measures

Baseline measures

-

1

A Risk Index was the sum of six (yes=1/no=0) items associated in prior research with worse infant outcomes (possible range=0–6). These six items included poor housing quality, maternal educational level less than 10th grade, income less than 2000 Rand/month, not being married, age greater than 34, and a significant depression score (>18 on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS); Chibanda et al., 2010).

-

2

A latent variable representing Social Support at baseline consisted of three measured items: (1) How many close friends and relatives do you have?, (2) In this past month, approximately how many times have you had contact with friends or relatives?, and (3) How many times in the past week has someone provided you with practical support?

-

3

Alcohol Use during Pregnancy was a latent variable indicated by three items (Dawson, Grant, & Stinson, 2005): (1) The frequency of drinking alcohol after she knew she was pregnant (0–9 scale ranging from 0=never to 9=every day), (2) Amount of alcohol on days after she knew she was pregnant (0–5 scale ranging from 0=none to 5=10 or more drinks), (3) Frequency of 3 or more drinks per day after knowledge of pregnancy (0–9 scale ranging from 0=never to 9=every day), and

-

4

HIV-positive status was a dichotomous variable (yes=1/no=0).

Six-month measures

-

5

Low birth weight (LBW) was defined as a baby that weighed less than 2500 grams at birth. This was a dichotomous variable (yes=1/no=0).

-

6

Social Support was assessed in exactly the same way as it was at baseline (see above).

-

7

Alcohol Use was assessed similarly to the way it was during pregnancy except that it indicated recent use after the birth of the child. The scales were constructed similarly to those reported above.

-

8

Breastfeeding only was considered desirable in the first 6 months. This dichotomous variable was scored 1 if the mother reported breastfeeding exclusively for 6 months, 0 otherwise.

Eighteen-month outcomes

-

9

Three measures were used as indicators of a latent variable representing Baby’s Growth and Development. Standardised weight/height measures were obtained by converting infant anthropometric data (collected from growth monitoring information) to z-scores based on the World Health Organization’s age- and gender-adjusted norms for weight, height/length, and weight-for-height (WHO Multicentre Growth reference Study Group, 2006; Cogill, 2003).

-

10

Recent diarrhoea (past 2 weeks) was assessed by a dichotomous variable (yes=1/no=0).

Intervention group status

-

11

A dichotomous variable (yes=1/no=0) indicated if the participant was in the intervention group.

Analysis

The confirmatory and predictive path analyses were performed using the EQS structural equations programme (Bentler, 2006). These analyses compare a proposed hypothetical model with a set of actual data. The closeness of the hypothetical model to the empirical data is evaluated statistically through various goodness-of-fit indexes. Goodness-of-fit was assessed with both maximum likelihood χ2 and the robust Satorra-Bentler χ2 (S-B χ2) values, the Comparative Fit Index, Robust Comparative Fit Index (RCFI), and the root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA; Bentler, 2006; Hu & Bentler, 1999). The Robust S-B χ2 was used in addition to normal maximum likelihood methods because it is appropriate when the data depart from multivariate normality. The multivariate kurtosis estimate was high in the data set (normalised Mardia z-statistic=211.86) rejecting multivariate normality. The CFI and RCFI range from 0 to 1 and reflect the improvement in fit of a hypothesised model over a model of complete independence among the measured variables. RCFI values at .95 or greater are desirable, indicating that the hypothesised model reproduces 95% or more of the covariation in the data. The RMSEA is a measure of lack of fit per degrees of freedom, controlling for sample size, and values less than .06 indicate a relatively good fit between the hypothesised model and the observed data.

An initial confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) assessed the adequacy of the hypothesised measurement model and the associations among the latent variables and the single item variables without imputing any directionality. Then a directional latent variable path model positioned baseline variables of the Risk Index, baseline social support, alcohol use during pregnancy, and HIV-positive status as predictors of the 6-month intermediate measures of low birth weight, six-month social support, alcohol use, and breastfeeding only which in turn predicted 18-month outcomes of baby’s growth and development and recent diarrhoea. Intervention condition status predicted the 6-month intervening variables and the outcome variables. Non-significant paths and co-variances were gradually dropped until only significant paths and co-variances remained.

Because of random assignment we did not expect intervention condition membership to be correlated with any baseline predictors although we examined in the CFA whether by chance any of the baseline measures were associated significantly with intervention status. We also report whether there were significant indirect effects on 18-month outcomes of any baseline predictor or of intervention status mediated through the 6-month variables.

Results

Demographics of the sample

The average age of the women was 26.7 years (SD=5.7) and they ranged in age from 18 to 42. Regarding marital status, 41.8% were not married, 38.8% were married, and 19.4% were not married but were living with someone. Twenty-six percent had less than 10 years of education; 81% were not employed. Twenty-eight percent had incomes equal to or under 2 000 Rand/month (approximately $200).

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Table 1 reports the means, standard deviations, ranges, and standardised factor loadings for the measured variables. All measured variables loaded significantly (p ≤ .001) on their hypothesised latent factors. The fit indexes were highly acceptable [ML χ2 (139, N=874) =449.45; CFI=.97; RMSEA=0.05; S-B χ2 (139, N=874) =326.09; RCFI=.97, RMSEA=.04]. One correlated error residual was added between 2 of the standardised growth and development indicators, BMI for age and weight for length/height (which is not surprising considering the high correlations among the measures). This modification was performed based on a suggestion from the Lagrange Multiplier test (Chou & Bentler, 1990).

Table 1.

Summary Statistics and Factor Loadings in the Confirmatory Factor Analysis

| Variables (range) | Mean (or %) | SD | Factor Loading* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | |||

| Risk Index (0–6) | 2.11 | 1.18 | —— |

| Social Support | |||

| Number of friends (0–10) | 2.72 | 1.53 | .32 |

| Times have contact during month (0–60) | 13.40 | 11.46 | .35 |

| Times provided with practical support (0–30) | 2.19 | 2.59 | .41 |

| Alcohol Use during Pregnancy | |||

| Alcohol frequency (1–9) | 1.27 | 0.94 | .92 |

| Number of drinks/day (0–5) | 0.15 | 0.58 | .88 |

| Freq. 3 or more drinks/day (0–9) | 1.18 | 0.83 | .84 |

| HIV-positive | 26% | —— | |

| 6-month Follow-up | |||

| Low birth weight | 8% | —— | |

| Social Support | |||

| Number of friends (0–10) | 2.20 | 1.51 | .47 |

| Times have contact during month (0–31) | 10.85 | 10.89 | .34 |

| Times provided with practical support (0–10) | 2.67 | 2.29 | .59 |

| Alcohol Use | |||

| Alcohol frequency (1–9) | 1.14 | 0.90 | .90 |

| Number of drinks/day (0–5) | 0.14 | 0.52 | .82 |

| Freq. 3 or more drinks/day (0–9) | 0.27 | 0.99 | .99 |

| Breastfed exclusively | 16% | —— | |

| 18-month Baby Outcomes | |||

| Baby Growth and Development | |||

| Weight for age | 0.26 | 1.17 | .99 |

| Weight for length/height | 0.72 | 1.32 | .90 |

| BMI for age | 0.84 | 1.34 | .83 |

| Recent Diarrhoea | 22% | —— | |

| Intervention Group Member | 53% | —— |

All factor loadings significant, p ≤ .001.

Correlations among all of the latent and single-item variables are reported in Table 2. Of note, intervention membership was not significantly associated with any baseline variables as had been hypothesised. Interesting associations among many of the constructs in the model can be observed. The summative Risk Index was significantly associated with less social support at both baseline and at the 6-month follow-up, and with more alcohol use at both time periods. The Risk Index was also significantly associated with being HIV-positive, less likelihood of breastfeeding exclusively, and with poorer growth and development. Greater social support at baseline was most associated with its identically derived latent variable, 6-month social support, and with better growth and development. Alcohol use during pregnancy was significantly associated with LBW, alcohol use at 6-months, and poorer growth and development. HIV-positive status was significantly associated with LBW, less breastfeeding, and poorer growth and development. LBW was modestly associated with social support at 6-months, more alcohol use at 6-months, and poorer growth and development. More social support at 6-months was associated with exclusive breastfeeding, better growth and development, and with being part of the intervention group. More alcohol use at 6-months was associated with poorer growth and development and more likelihood of recent diarrhoea. Breastfeeding exclusively was associated significantly with less recent diarrhoea and being in the intervention group. Recent diarrhoea was associated with poorer growth and development and was less likely among those in the intervention group.

Table 2.

Correlations among Measured and Latent Variables in Model

| Variables | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| 1. Risk Index | — | |||||||||

| 2. Social Support | −.22*** | — | ||||||||

| 3. Alcohol Use during Pregnancy | .08* | −.05 | — | |||||||

| 4. HIV-Positive | .13*** | −.04 | .02 | — | ||||||

| 6-month Follow-up | ||||||||||

| 5. Low birth weight | .04 | −.01 | .07* | .09* | — | |||||

| 6. Social Support | −.16*** | .63*** | −.04 | .01 | .11* | — | ||||

| 7. Alcohol Use | .11*** | .01 | .26*** | .03 | .12** | .08 | — | |||

| 8. Breastfed exclusively | −.07* | .01 | −.01 | −.21*** | −.01 | .10* | −.03 | — | ||

| 18-month Outcome | ||||||||||

| 9. Baby Growth and Development | −.17*** | .13* | −.11** | −.11*** | −.20*** | .13** | −.11** | −.03 | — | |

| 10. Recent Diarrhoea | −.01 | .00 | .02 | .01 | .05 | −.05 | .08* | −.07* | −.11** | – |

| Group Membership | ||||||||||

| 11. Intervention member | .04 | −.05 | .00 | −.01 | .03 | .21*** | .01 | .19*** | .03 | −.09** |

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Path model

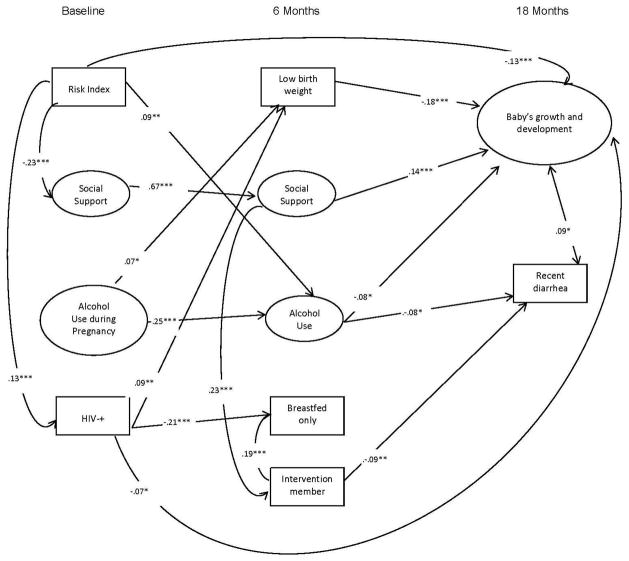

The final path model has excellent fit statistics (ML χ2 (176, N=874) =494.94; CFI=.97; RMSEA=0.05; S-B χ2 (176, N=874) =380.68; RCFI=.97, RMSEA=.04). Results of the analysis with all significant paths included are depicted in Figure 2. Latent variables are represented by circles; measured variables are depicted in rectangles. Significant correlations among the predictors are also depicted in the figure as well as a negative correlation between the error residuals of recent diarrhoea and development and growth. Only significant direct effects are shown in the figure.

Figure 2.

Significant regression paths predicting infant outcomes among 874 South African women. Large circles represent latent variables; rectangles represent single-item indicators. Single-headed arrows represent regression coefficients. Regression coefficients are standardized (* = p ≤.05, **= p ≤. .01, *** = p ≤ .001).

Direct effects

Some associations that were significant in the CFA did not emerge as significant in the path model. Alcohol use during pregnancy and HIV-positive status predicted LBW. Baseline social support and Intervention membership predicted greater social support at 6-months. Greater alcohol use at 6-months was predicted by the Risk Index and alcohol use during pregnancy. Breastfeeding only was predicted by intervention membership and was less likely among the women who were HIV-positive. Growth and development was predicted by LBW (negatively), greater social support at 6-months, less alcohol use at 6-months, a lower Risk Index, and HIV-positive status (negatively). Recent diarrhoea was less likely for Intervention members and was more likely among mothers reporting more alcohol use at 6-months.

Indirect effects

There also were significant indirect effects of baseline variables and intervention status on the 18-month outcome variables mediated through the 6-month variables. Significant indirect effects on growth and development include baseline social support (p<.01), less alcohol use during pregnancy (p<.01), and not being HIV-positive (p<.05). Furthermore, being in the intervention group had a significant indirect effect through its substantial impact on social support at 6-months (p<.01). The only significant indirect effect on recent diarrhoea was an indirect effect of alcohol use during pregnancy (p<.05) mediated through alcohol use at 6-months.

Conclusions

A CHW home-based intervention can significantly improve maternal and child health outcomes during a woman’s pregnancy and the first vulnerable months of a child’s life, although the influence does not appear as durable as previous research with nurses in the US would have led us to expect (Sweet & Appelbaum, 2004; Haines et al., 2007). We observed that reductions in diarrhoea were observed at 18 months in the intervention group. More alcohol use at six months and less breastfeeding resulted in significantly more recent diarrhoea episodes and diarrhoea was negatively associated with growth and development. It is not clear whether there is less diarrhoea because intervention mothers are using clean water (control mothers have the same access to clean water), know how to make the ORT solution themselves, or are better caretakers. However, the result is clear; the intervention was associated with fewer recent episodes of diarrhoea.

At six months, there was significantly more exclusive breastfeeding and greater perception of social support among intervention mothers compared to the mothers in the control neighbourhoods. Breastfeeding protects infants from diseases (specifically diarrhoea) through transmitted immunity from the mother and less risk for contaminations by unclean bottles, promotes closeness between the mother and child, and reduces the costs of healthy living for children (Davis, 2011; Lamberti et al., 2011; McKee, Zayas, & Jankowski, 2004; Ball & Wright, 1999). There was less breastfeeding in the HIV positive group. This is important considering the new WHO guidelines promoting exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months for both HIV negative and positive mothers (World Health Organization, 2012). Although the intervention did not have a direct effect on growth and development, its significant indirect effect, mediated through greater social support, is notable.

The Risk Index was a viable construct and useful as a control for prior behaviours and also a predictor in its own right. Increased risk is associated with a range of negative outcomes for children over both 6 and 18 months: with more alcohol use there is worse growth and development, and less social support. Being an HIV-infected mother does have long term impact on infants’ growth, even though the infants are not HIV-infected. Only 1.4% of infants were HIV-infected post birth. The HIV-positive mothers may have been fearful of breastfeeding even though it is recommended. HIV positive women remain vulnerable, and intervention support should be sustained over the lifespan of these mothers.

LBW exerts a long-term influence on infants’ health and development outcomes and is initially impacted by risk factors such as maternal HIV+ status and alcohol use. It needed to be included as an important control in the analysis, but the effect could also be mitigated if interventions start pre-pregnancy, encouraging less or no alcohol use if sexually active or actively trying to become pregnant. This would also lessen HIV-risk behaviours. In summary – CHW intervention, social support as defined in this paper, breastfeeding, HIV negative status, and no alcohol intake are associated with significant health benefits for women and children.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This study was funded by NIAAA Grant # 1R01AA017104 and supported by NIH grants MH58107, 5P30AI028697, and UL1TR000124. Mark Tomlinson is supported by the National Research Foundation (South Africa).

Footnotes

Trial Registration ClinicalTrials.gov registration # NCT00996528

Ethics statement

All research involving human participants was approved by the UCLA Institutional Review Board (# 10-000386) and the Stellenbosch University Institutional Review Board (N08/08/218), and the Emory University Institutional Review Board (IRB00008003).

Conflict of interest

No authors have any conflicts of interest. All authors declare: support was received from the National Institutes of Health to conduct this research, but no support from any organisation with a vested interest in the outcomes of the work was provided to any author, nor were there any financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years, no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, interpretation of data, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The Corresponding Author has the right to grant on behalf of all authors and does grant on behalf of all authors, a worldwide licence to the Publishers and its licensees in perpetuity, in all forms, formats and media (whether known now or created in the future), to i) publish, reproduce, distribute, display and store the Contribution, ii) translate the Contribution into other languages, create adaptations, reprints, include within collections and create summaries, extracts and/or abstracts of the Contribution, iii) create any other derivative work(s) based on the Contribution, iv) to exploit all subsidiary rights in the Contribution, v) the inclusion of electronic links from the Contribution to third party material wherever it may be located; and, vi) licence any third party to do any or all of the above.

References

- Aarnoudse-Moens CSH, Weisglas-Kuperus N, van Goudoever JB, Oosterlaan J. Meta-analysis of neurobehavioral outcomes in very preterm and/or very low birth weight children. Pediatrics. 2009;124(2):717–728. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alamo S, Wabwire-Mangen F, Kenneth E, Sunday P, Laga M, Colebunders RL. Task-shifting to community health workers: evaluation of the performance of a peer-led model in an antiretroviral program in Uganda. AIDS patient care and STDs. 2012;26(2):101–107. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.0279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball TM, Wright AL. Health care costs of formula-feeding in the first year of life. Pediatrics. 1999;103(Supplement 1):870–876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. EQS structural equations program manual. Encino, CA: Multivariate Software, Inc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Black RE, Cousens S, Johnson HL, Lawn JE, Rudan I, Bassani DG, Jha P, Campbell H, Walker CF, Cibulskis R, Eisele T, Liu L, Mathers C. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2008: a systematic analysis. The Lancet. 2010;375(9730):1969–1987. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60549-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryce J, Gilroy K, Jones G, Hazel E, Black RE, Victoria CG. The Accelerated Child Survival and Development Programme in West Africa: a Retrospective Evaluation. The Lancet. 2010 Feb 13;375(9714):572–82. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62060-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chibanda D, Mangezi W, Tshimanga M, Woelk G, Rusakaniko P, Stranix-Chibanda L, Midzi S, Maldonado Y, Shetty AK. Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale among women in a high HIV prevalence area in urban Zimbabwe. Archives of women’s mental health. 2010;13(3):201–206. doi: 10.1007/s00737-009-0073-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou CP, Bentler PM. Model modification in covariance structure modeling: A comparison among likelihood ratio, Lagrange multiplier, and Wald tests. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1990;25(1):115–136. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr2501_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cogill B. Anthropometric indicators measurement guide. Washington DC: Food and Nutritional Technical Assistance Project; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper PJ, Tomlinson M, Swartz L, Woolgar M, Murray L, Molteno C. Post-partum depression and the mother-infant relationship in a South African peri-urban settlement. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;175(6):554–558. doi: 10.1192/bjp.175.6.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis MK. Breastfeeding and chronic disease in childhood and adolescence. Pediatric Clinics of North America. 2001;48(1):125–141. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(05)70289-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS. The AUDIT-C: screening for alcohol use disorders and risk drinking in the presence of other psychiatric disorders. Comprehensive psychiatry. 2005;46(6):405–416. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewey KG, Begum K. Long-term consequences of stunting in early life. Maternal & Child Nutrition. 2011;7(s3):5–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2011.00349.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichenwald EC, Stark AR. Management and outcomes of very low birth weight. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;358(16):1700–1711. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0707601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filteau S. The HIV-exposed, uninfected African child. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2009;14(3):276–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer Walker CL, Lamberti L, Adair L, Guerrant RL, Lescano AG, Martorell R, Pinkerton RC, Black RE. Does childhood diarrhea influence cognition beyond the diarrhea-stunting pathway? PloS One. 2012;7(10):e47908. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grantham-McGregor S. Early child development in developing countries. The Lancet. 2007;369(9564):824. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60404-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haines A, Sanders D, Lehmann U, Rowe AK, Lawn JE, Jan S, Walker DG, Bhutta Z. Achieving child survival goals: potential contribution of community health workers. The Lancet. 2007;369(9579):2121–2131. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60325-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes B, Sharif F. Behavioural and emotional outcome of very low birth weight infants–literature review. Journal of Maternal-Fetal and Neonatal Medicine. 2009;22(10):849–856. doi: 10.1080/14767050902994507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan DP, Park JM. Family factors and social support in the developmental outcomes of very low-birth weight children. Clinics in Perinatology. 2000;27(2):433–459. doi: 10.1016/s0095-5108(05)70030-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6(1):1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kalimba EM, Ballo DE. Survival of extremely low-birth-weight infants. South African Journal of Child Health. 2013;7(1):13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Kimani-Murage EW, Kahn K, Pettifor JM, Tollman SM, Dunger DB, Gómez-Olivé XF, Norris SA. The prevalence of stunting, overweight and obesity, and metabolic disease risk in rural South African children. BMC Public Health. 2010;10(1):158. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamberti LM, Walker CLF, Noiman A, Victora C, Black RE. Breastfeeding and the risk for diarrhea morbidity and mortality. BMC public health. 2011;11(Suppl 3):S15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-S3-S15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- le Roux IM, le Roux K, Comulada WS, Greco EM, Desmond KA, Mbewu N, Rotheram-Borus MJ. Home visits by neighborhood Mentor Mothers provide timely recovery from childhood malnutrition in South Africa: results from a randomized controlled trial. Nutr J. 2010;9(56):1–10. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-9-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- le Roux IM, le Roux K, Mbeutu K, Comulada WS, Desmond KA, Rotheram-Borus MJ. A randomized controlled trial of home visits by neighborhood mentor mothers to improve children’s nutrition in South Africa. Vulnerable children and youth studies. 2011;6(2):91–102. doi: 10.1080/17450128.2011.564224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- le Roux IM, Tomlinson M, Harwood JM, O’Connor MJ, Worthman CM, Mbewu N, Stewart J, Hartley M, Swendeman D, Comulada WS, Weiss RE, Rotheram-Borus MJ. Outcomes of home visits for pregnant mothers and their infants: a cluster randomized controlled trial. AIDS. 2013;27(9):1461–1471. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283601b53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin S, Munabi-Babigumira S, Glenton C, Daniels K, Bosch-Capblanch X, van Wyk BE, Odgaard-Jensen J, Johansen M, Aja GN, Zwarenstein M, Scheel IB. Lay health workers in primary and community health care for maternal and child health and the management of infectious diseases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010:3. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004015.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May PA, Brooke L, Gossage JP, Croxford J, Adnams C, Jones KL, Viljoen D. Epidemiology of fetal alcohol syndrome in a South African community in the Western Cape Province. American journal of public health. 2000;90(12):1905–1912. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.12.1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbonu NC, van den Borne B, De Vries NK. Stigma of people with HIV/AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa: a literature review. Journal of tropical medicine. 2009;2009 doi: 10.1155/2009/145891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald CM, Kupka R, Manji KP, Okuma J, Bosch RJ, Aboud S, Kisenge R, Spiegelman D, Fawzi WW, Duggan CP. Predictors of stunting, wasting and underweight among Tanzanian children born to HIV-infected women. European journal of clinical nutrition. 2012;66(11):1265–1276. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2012.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee MD, Zayas LH, Jankowski KRB. Breastfeeding intention and practice in an urban minority population: relationship to maternal depressive symptoms and mother–infant closeness. Journal of reproductive and infant psychology. 2004;22(3):167–181. [Google Scholar]

- Nannan N, Norman R, Hendricks M, Dhansay MA, Bradshaw D the South African Comparative Risk Assessment Collaborating Group. Estimating the burden of disease attributable to childhood and maternal undernutrition in South Africa in 2000. South African Medical Journal. 2007;97(8):733–739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor M, Tomlinson M, LeRoux IM, Stewart J, Greco E, Rotheram-Borus MJ. Predictors Of Alcohol Use Prior To Pregnancy Recognition Among Township Women In Cape Town, South Africa. Social Science & Medicine. 2011;72(1):83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.09.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olds D, Hill P, Rumsey E. Prenatal and Early Childhood Nurse Home Visitation. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Olds DL, Robinson J, O’Brien R, Luckey DW, Pettitt LM, Henderson CR, Jr, Ng RK, Sheff KL, Korfmacher J, Hiatt S, Talmi A. Home visiting by paraprofessionals and by nurses: a randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2002;110(3):486–496. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.3.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olds DL, Robinson J, Pettitt L, Luckey DW, Holmberg J, Ng RK, Isacks K, Sheff K, Henderson CR., Jr Effects of home visits by paraprofessionals and by nurses: age 4 follow-up results of a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2004;114(6):1560–1568. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peacock S, Konrad S, Watson E, Nickel D, Muhajarine N. Effectiveness of home visiting programs on child outcomes: a systematic review. BMC public health. 2013;13(1):17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick MB, Gueorguieva RV, Carter RL, Ariet M, Sun Y, Roth J, Bucciarelli RL, Curran JS, Mahan CS. The impact of low birth weight, perinatal conditions, and sociodemographic factors on educational outcome in kindergarten. Pediatrics. 1999;104(6):e74–e74. doi: 10.1542/peds.104.6.e74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Borus MJ, le Roux IM, Tomlinson M, Mbewu N, Comulada WS, le Roux K, Stewart J, O’Connor MJ, Hartley M, Desmond K, Greco E, Worthman CM, Idemundia F, Swendeman D. Philani Plus (+): a Mentor Mother community health worker home visiting program to improve maternal and infants’ outcomes. Prevention Science. 2011;12(4):372–388. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0238-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Borus MJ, Tomlinson M, Swendeman D, Lee A, Jones E. Standardized functions for smartphone applications: examples from maternal and child health. International journal of telemedicine and applications. 2012;2012:21. doi: 10.1155/2012/973237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shisana O, Rehle T, Simabayi LC, Zuma K, Jooste S, Pillay-van-Wyk V, Mbelle N, Van Zyl J, Parker W, Zungu NP, Pezi S the SABSSM III Implementation Team. South African national HIV prevalence, incidence, behaviour and communication survey 2008: A turning tide among teenagers? Cape Town: HSRC Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- South African Department of Health. The National Antenatal Sentinel HIV and Syphilis Prevalence Survey, 2011. Pretoria, South Africa: National Department of Health; 2011. [accessed September 2013]. http://www.doh.gov.za/docs/presentations/2013/Antenatal_Sentinel_survey_Report2012_final.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Sweet MA, Appelbaum MI. Is Home Visiting an Effective Strategy? A Meta-Analytic Review of Home Visiting Programs for Families With Young Children. Child development. 2004;75(5):1435–1456. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson M, O’Connor MJ, le Roux IM, Stewart J, Mbewu N, Harwood J, Rotheram-Borus MJ. Multiple Risk Factors During Pregnancy in South Africa: The Need for a Horizontal Approach to Perinatal Care. Prevention Science. 2013:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s11121-013-0376-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson M, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Doherty T, Swendeman D, Tsai AC, Ijumba P, le Roux IM, Jackson D, Stewart J, Friedman A, Colvin M, Chopra M. Value of a mobile information system to improve quality of care by community health workers. SA Journal of Information Management. 2013;15(1):9. doi: 10.4102/sajim.v15i1.528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udjo EO. A re-look at recent statistics on mortality in the context of HIV/AIDS with particular reference to South Africa. Current HIV research. 2008;6(2):143–151. doi: 10.2174/157016208783884994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. Young Lives: Statistical Data on the Status of Children Aged 0-4 in South Africa. 2007 Retrieved from: http://www.unicef.org/southafrica/SAF_resources_younglives.pdf.

- USAID. [Accessed on December 14, 2011];Maternal Health in South Africa. n.d http://www.usaid.gov/our_work/global_health/mch/mh/countries/southafrica.html.

- Victoria CG, Bryce J, Fontaine O, Monasch R. Reducing deaths from diarrhoea through oral rehydration therapy. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2000;78(10):1246–1255. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker SP, Wachs TD, Meeks Gardner J, Lozoff B, Wasserman GA, Pollitt E, Carter JA, International Child Development Steering Group Child development: risk factors for adverse outcomes in developing countries. The Lancet. 2007;369(9556):145–157. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60076-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. The Work of WHO in the African Region 2010 Annual Report for the Regional Director. Brazzaville: WHO; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group. WHO Child Growth Standards: Length/height-for-age, weight-for-age, weight-for-length, weight-for-height and body mass index-for-age: Methods and development. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. [Accessed on January 5, 2014];WHO Guidelines on HIV and Infant Feeding 2010: An updated framework for Priority Action. 2012 http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/75152/1/FWC_MCA_12.1_eng.pdf?ua=1.