Abstract

Prolactin (PRL) activates PRL receptor isoforms to exert regulation of specific neuronal circuitries, and to control numerous physiological and clinically-relevant functions including; maternal behavior, energy balance and food intake, stress and trauma responses, anxiety, neurogenesis, migraine and pain. PRL controls these critical functions by regulating receptor potential thresholds, neuronal excitability and/or neurotransmission efficiency. PRL also influences neuronal functions via activation of certain neurons, resulting in Ca2+ influx and/or electrical firing with subsequent release of neurotransmitters. Although PRL was identified almost a century ago, very little specific information is known about how PRL regulates neuronal functions. Nevertheless, important initial steps have recently been made including the identification of PRL-induced transient signaling pathways in neurons and the modulation of neuronal transient receptor potential (TRP) and Ca2+-dependent K+ channels by PRL. In this review, we summarize current knowledge and recent progress in understanding the regulation of neuronal excitability and channels by PRL.

Keywords: neuroendocrinology, prolactin receptor, neuronal channels, TRP channels, neuropeptides, Ca2+-dependent K+ channels

Introduction

Prolactin (PRL) represents a multifunctional endocrine hormone that was originally discovered in the 1930s as a factor controlling milk production and secretion. The vast number (> 300) of physiological functions influenced by PRL include reproduction, electrolyte balance, metabolism, regulation of the endocrine and immune systems, and modulation of the nervous system.1,2 The PRL-induced regulation of the nervous system is manifested in such important and relevant processes as maternal behavior, energy balance, food intake, stress and trauma responses, anxiety, neurogenesis, migraine and pain.3-14 To understand this wide spectrum of processes that potentially influences the etiology of a vast array of disease conditions affecting millions of people, it is essential to delineate the specific mechanisms responsible for the PRL control of function in various neuronal circuitries. The aim of the present review is to summarize the current knowledge and recent progress made in understanding mechanisms responsible for PRL-induced regulation of neuronal functions and the channels involved.

Prolactin in the Nervous System

To understand mechanisms responsible for the regulation of nervous system function by PRL on normal physiological processes and in pathological conditions, it is essential to outline PRL concentrations in the different regions of the nervous system during various conditions. Serum levels are important since PRL from the peripheral circulation can gain access to the CNS either via receptor-mediated mechanisms15 or through circumventricular structures that lack a blood–brain barrier.16 The major source of serum PRL is from specialized anterior pituitary cells called lactotrophs.2 Under normal conditions, concentrations of PRL in blood are closely regulated by estrogen and depend on sex, the reproductive cycle, pregnancy and lactation.2 In rodent and human males, blood PRL levels are 5–20 ng/ml. In female rodents, blood PRL levels peak at proestrous phase (12–14 h) and reach up to 120–150 ng/ml.17 After proestrous phase, PRL drops and plateaus for 25–27 h (estrous phase) to 60–80 ng/ml, and then declines even further to 30–60ng/ml during diestrous phase (55–57 h).17 In contrast, the blood PRL level in women is not strongly influenced by menstrual cycle and stays in a range of 10–60 ng/ml.2 The profile of PRL release during human pregnancy is entirely different from that in rodents.18,19 Nevertheless, in both rodents and humans, observed blood PRL levels are as high as 200–300 ng/ml during pregancy.2 During lactation, PRL remains as high as that found during pregnancy, but then gradually declines.20,21 PRL levels in blood are also significantly up-regulated in several notable pathological conditions, the first being inflammation. The inflammatory conditions associated with increased PRL serum levels include a severe form of progressive systemic sclerosis,22,23 the active phase of systemic lupus erythematosus,24,25 rheumatoid arthritis,26 polymyalgia rheumatica27 and autoimmune thyroid diseases.28 In contrast to these chronic inflammatory conditions, acute inflammation does not cause elevated levels of PRL in blood.29 The second pathological condition associated with elevated levels of PRL is physiological and physical stress (i.e., trauma). Burn,30 surgical procedures,31,32 osteoarthritis,33 migraine11,34 and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)35 are all associated with increased PRL serum levels. Although estrogen is important in the regulation of PRL, PRL could be considered as a dually regulated hormone, where both estrogen and a specific pathological condition, especially stress and inflammation, also control the levels of PRL in blood. This dual regulation is an important point and needs to be considered by investigators when studying the regulation of neuronal functions by PRL.

Circulating PRL in the blood from the anterior pituitary is not the only source of PRL in the nervous system, since extra-pituitary sources are known that include PRL from neurons and non-neuronal cells located in both the peripheral (PNS) and central nervous system (CNS).7,29,36-40 Dual regulation of extra-pituitary PRL by estrogen and pathological condition is not well studied. Therefore, direct measurements on alterations in PRL concentrations in relevant parts of the nervous system triggered by pathological conditions are important to consider. PRL concentrations can be measured from total protein extracts obtained from particular regions of the PNS or CNS and these extracts contain both extracellular and intracellular proteins. For example, rat male lumbar (L4-L6) spinal cord contains 2ng/ml PRL and 6 ng/ml PRL 24h after hindpaw surgery.7 In contrast, female rats in estrous phase have 8ng/ml PRL, but this is elevated to 40ng/ml 24h after surgery.7 The exact source(s) responsible for these elevated PRL levels seen in the spinal cord after surgical trauma is unknown. In addition, it is possible that PRL concentrations in the vicinity of neuronal synapses located in important pain processing regions of the spinal cord will be even higher than the concentrations obtained from total proteins. Nevertheless, although exact physiological PRL concentrations acting on particular neurons cannot be established, evaluations of total PRL protein concentrations in defined regions of the nervous system do offer fundamental information when considering possible contributions of changed PRL concentration levels to neuronal activation in pathological conditions.

Prolactin Receptor in the Nervous System

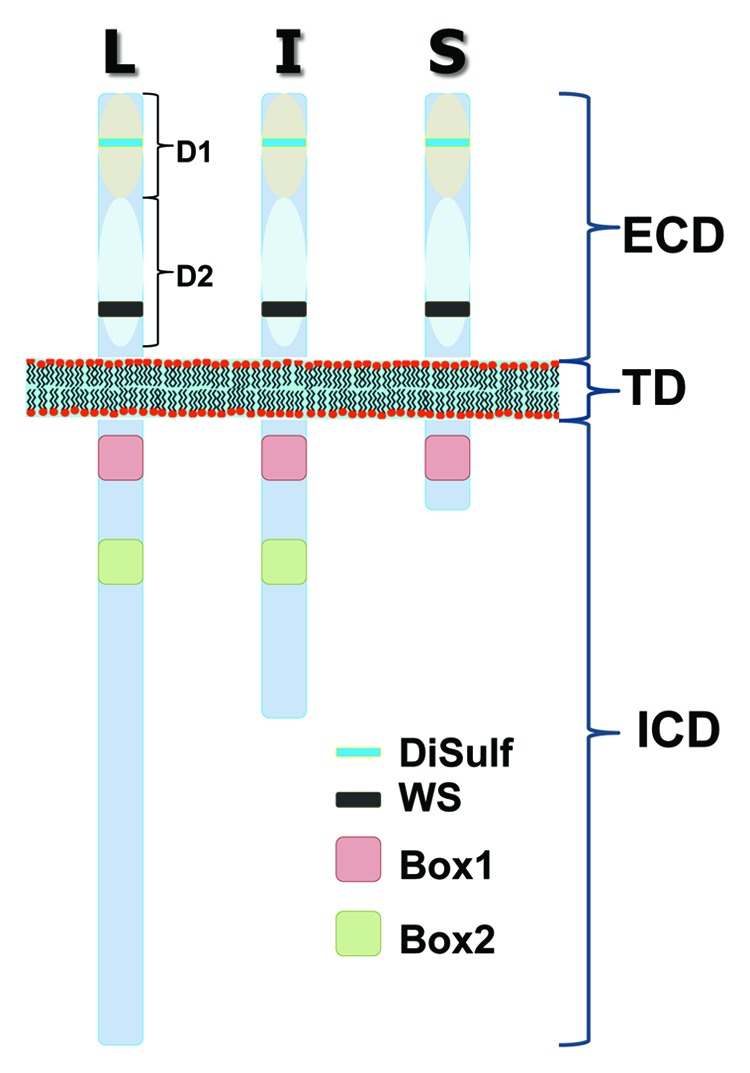

PRL actions are specifically mediated via the PRL receptor (PRLR).1 PRLR belongs to the cytokine type I subfamily, which also includes receptors for growth hormone, leptin, leukemia inhibiting factor and erythropoietin.41 Along with an extracellular domain (ECD) that binds PRL, PRLR also has a single trans-membrane domain (TD) and intracellular domain (ICD) (Fig. 1). PRLR is encoded by a single gene, but has numerous tissue and cell-specific splice variants. A complete gene structure of PRLR is presented in detail in several excellent reviews,1,2,41 and the exon-intron structure can be found on the website Atlas of Genetics and Cytogenetics. Briefly, PRLR has three isoforms: long (PRLR-L), intermediate (PRLR-I in rodents = S1a in humans) and short (PRLR-S in rodents = S1b in humans)2,42 (Fig. 1). PRLR exists either as a homodimer or heterodimer between PRLR-L and PRLR-S.43 Isoforms have identical ECD and TD, but differ in ICD lengths and sequences (Fig. 1). In this respect, the most noticeable difference between long and short forms is that PRLR-L and PRLR-I (an uncommon form) have Box-1 and Box-2 domains, while PRLR-S also has Box-1 but lacks the Box-2 domain (Fig. 1). Consequently, cellular signaling pathways via PRLR-L and PRLR-S are substantially different. For example, PRLR-L, but not PRLR-S, activates both Janus kinase2/signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 (JAK2/STAT5) pathways.44 PRL is the main mediator inducing phosphorylation of STAT5 (phospho-STAT5) in the nervous system, with dopamine D2 receptor (D2R) agonist-bromocriptine-treatment blocking a majority of basal phospho-STAT5 expression (Table 1).45 In addition to PRL, growth hormone and leptin have the capability of phosphorylating STAT5 in the hypothalamus.46,47 The phosphorylation of STAT5 likely controls long-term changes in the nervous system. The regulation of neuronal excitability and channels often requires the activation of a transient signaling pathway and the role of PRLR-L and -S in transient signaling in neurons will be discussed in detail below.

Figure 1. Schematic presentation of PRL receptor (PRLR) isoforms. PRLR has extracellular domain (ECD) and transmembrane domain (TD), which are identical between isoforms. In contrast, intracellular domain (ICD) of PRLR has variable length and composition between PRLR long (L), intermediate (I) and short (S) isoforms. Common features between PRLR isoforms are two extracellular sub-domains (D1 and D2), a disulfide bond (yellow box), WS motif (black box) that is critical for PRLR folding and trafficking, as well as Box 1 (reddish box) that is SH3-binding domains, recognized by signal transducers and critical for activation of JAK2 signal pathway. Box 2 (green box) is absent in short isoforms.

Table 1. The nervous system.

| The nervous system | PRLR-L | PRLR-S | pSTAT5 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anteroventral periventricular nucleus (AVPV) | +++ | ++++ | +++ |

| Medial preoptic nucleus (MPN) | +++ | +++ | + |

| Median preoptic nucleus (MEPO) | - | +++ | - |

| Anteroventral preoptic nucleus (ADP) | ++ | ? | ? |

| Parastrial nucleus (PS) | +++ | ? | ? |

| Supraoptic nucleus (SO) | ++ | +++ | ? |

| Medial septal nucleus (MS) | ++ | ? | ? |

| Rostral preoptic periventricular nuclei (rPVpo) | ++ | ? | + |

| Caudal preoptic periventricular nuclei (cPVpo) | ++ | ? | + |

| Choroid plexus (CP) | ++ | - | ++ |

| Anterior bed nuclei stria terminalis (aBST) | ++ | ++ | + |

| Posterior bed nuclei stria terminalis (pBST) | ++ | ++ | + |

| Lateral septum (LS) | ++ | +++ | + |

| Anterior hypothalamic area (AHA) | ++ | ? | - |

| Paraventricular nucleus thalamus (PVT) | + | +++ | - |

| Paraventricular nucleus (PVN) | + | +++ | - |

| Arcuate nucleus (ARN) | ++++ | +++ | +++ |

| Ventromedial nucleus, ventrolateral part (VMH) | ++ | +++ | + |

| Dorsomedial nucleus (DMN) | ++ | ? | + |

| Posterior hypothalamic nucleus (PH) | ++ | ? | - |

| The medial nucleus of the amygdale (MEA) | ++ | ++ | + |

| Dorsal supraoptic nucleus (SON) | + | ? | ? |

| Lateral hypothalamus (LHA) | + | ++ | ? |

| The lateral preoptic area (LPO) | + | ? | ? |

| Periaqueductal gray (PAG) | ++ | ? | ? |

| Interpeduncular nucleus (IPN) | + | ? | ? |

| Substantia nigra (SN) | - | ? | ? |

| Pontine gray (PG) | - | ? | ? |

| The dorsal horn of the spinal cord | +++ | ? | +++ |

| The ventral horn of the spinal cord | - | - | - |

| Trigeminal ganglion | + | ++++ | ? |

| Dorsal root ganglion | ++ | ++++ | +++ |

| The sympathetic nervous system | Celiac ganglion | ||

| The enteric nervous system | ? | ||

| The parasympathetic nervous system | ? | ||

Regular font, the central nervous system (CNS) regions, excluding brain stem and spinal cord. Underlined, the brain stem and spinal cord regions. Bold, the peripheral nervous system (PNS), including sensory, sympathetic, parasympathetic and enteric nervous systems.

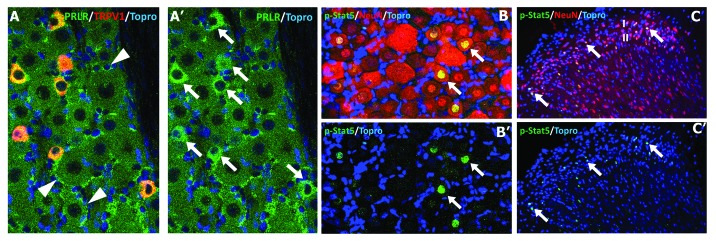

To understand the wide spectrum of PRL actions in the nervous system, it is essential to first identify PRL-sensitive neurons. PRLR-L and PRLR-S expression patterns in the CNS of female and male rodents have been characterized in detail45,48-51 and are summarized in Table 1. The PRLR expression pattern in the CNS is notably similar in rats and mice. Importantly, PRL can modulate the function of sensory neurons,39 and this modulation can help account for sex differences in pain mechanisms.7,8 A PRLR antibody, which does not discriminate between the different forms of PRLR, labels 50–60% of neurons in female rat trigeminal ganglia (TG) and a majority of the satellite glial cells (SGC) surrounding neuronal cell bodies.40 However, use of in situ hybridization showed that PRLR-L is only present in 3–5% of male and female rat TG neurons thus suggesting that much of the PRLR immunoreactivity is due to PRLR-S. Evaluation of human dental pulp tissue that is innervated by the trigeminal nerve, showed that PRLR-L is mostly absent in afferent nerves, but is present in the myelin sheath of peripheral glia that surrounds nerves.40 In contrast, the use of isoform-specific human antibodies, showed that both PRLR-S1a and 1b were present in both nerve axoplasm and glia.40 In the female rat dorsal root ganglia (DRG), PRLR staining as seen with the U5-clone 5 monoclonal antibody52 is also observed in many neurons and satellite glial cells (Fig. 2A) like seen in the female rat TG. In addition, many of the DRG sensory neurons with prominent PRLR-expression are small in size and almost all co-express TRPV1 (Fig. 2A), and both of these features are common in nociceptors. Interestingly, basal levels of activated phospho-STAT5 are present in ≈10–15% rat female DRG neurons labeled with phospho-STAT5 antibody (Fig. 2B), along with a subset of spinal cord neurons located primarily within the superficial laminae of the dorsal horn, an important region responsible for the modulation of nociceptive stimuli (Fig. 2C). In contrast, the satellite glial cells typically do not show significant phospho-STAT5 labeling under basal conditions. The phospho-STAT5 positive DRG neurons are also predominantly small in size. It is not yet clear if this basal expression of phospho-STAT5 in DRG and dorsal horn neurons is regulated by PRL as it is within other regions of the CNS.45 If this is the case, it would suggest that the DRG has a higher expression of PRLR-L than the TG. Nonetheless, it appears that the dominant PRLR isoform in sensory neurons is PRLR-S40 (Fig. 2). Results of other studies show that PRLR is also highly expressed in neurons within the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus (ARN) and anteroventral periventricular nucleus (AVPV), in addition to the expressions seen in sensory ganglia.40,45 In this respect, it comes as no surprise that a majority of studies on regulation of neuronal functions by PRL have been done on neurons from ARN, AVPV, DRG and TG.

Figure 2. Expression of PRLR and phospho-STAT5 in female DRG and spinal cord. (A)/(A’) PRLR (green; clone-U5, dilution 1:50, Thermo Scientific, Cat: MAI-160) is highly expressed in TRPV1-positive (A; red; 1:1000, Neuromics, GP14100) the dorsal root ganglion (DRG) sensory neurons (A’; arrows) and in satellite glial cells (A; arrowheads). (B)/(B’) For the nuclear expression of phospho-STAT5 (pSTAT5, 1:100, Cell Signaling Technology, Cat Number 9314) immunohistochemistry, a high temperature plus high pH antigen retrieval step were employed. The nuclear expression of pSTAT5 (arrows) is most commonly seen in small-diameter sensory neurons located in DRG and in (C)/(C’) NeuN (1:100, Millipore, MAB377) identified neurons located within the superficial laminae (I/II) of the dorsal horn. Topro (1:5000, Invitrogen, T3605) was used for nuclear staining.

Activation of Neurons by PRL

Activation of neurons can evoke action potentials and/or Ca2+ influx in neurons, culminating in the release of neurotransmitters or neuropeptides. An excellent example of this is the PRL-stimulated release of oxytocin or dopamine from hypothalamic neurons that control feedback mechanisms.53,54 In addition, PRL is capable of exerting action potential firing in different types of neurons. Thus, tuberoinfundibular dopamine (TIDA) neurons located in ARN provide a dopaminergic inhibitory tone on lactotrophs and fire action potentials upon application of 20nM (≈450ng/ml) PRL.55-58 TIDA neurons, identified as tyrosine hydroxylase-positive, display hallmark oscillation, when recorded in male rat hypothalamic slices using the whole-cell patch clamp technique.59 However, loose patch recording from mouse TIDA neurons, identified as dopamine transporter-expressing cells, found oscillation only in 20% neurons.60 Interestingly, these TIDA neurons displayed irregular spontaneous action potentials, and PRL-induced firing rates were not modified during lactation.60 PRL (20nM) is also capable of generating electrical firing in < 5% of female rat hypothalamic AVPV, but not gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH)-positive neurons.56

When rat male TIDA neurons are voltage clamped at resting membrane potentials (≈-65mV), exposure to high concentrations of PRL (40–500 nM, ≈1–12 μg/ml) generates small inward currents (IPRL; 15–25 pA).58 This depolarizing IPRL could change the membrane potential above threshold levels and produce action potentials, which are observed in TIDA neurons upon PRL application.58 The precise nature of the channels mediating IPRL in TIDA neurons is not known. However, it has a certain pharmacological profile. Thus, IPRL was abolished by 2-aminoethyl diphenylborinate (2-APB), but not by SKF96365, a TRPC6/TRPC7 channel antagonist. IPRL was also larger in the presence of low extracellular Ca2+ 58. These results imply that IPRL could be mediated by a TRP-like channel, probably one of the TRPC1-TRPC4 channels.61 To identify intracellular cascades involved in generation of IPRL, JAK and phosphoinositide 3 (PI3)-kinase pathways were blocked with AG490 and wortmannin (200nM), respectively.58 Neither JAK nor PI3-kinase pathways are engaged in generation of IPRL.58 Activation of TIDA neurons by PRL is similar in effect to that of leptin on ARN neurons, which is also mediated by TRPC-like channels.62 The difference is that leptin’s action is via a JAK pathway.62 PRL is also able to produce inward current (at resting membrane potentials) in non-neuronal, glioma cells.63 This IPRL appeared several minutes after PRL application, independent from intracellular Ca2+, but triggered by an unknown second messenger.63 In summary, even though the precise nature of PRL-activated channels in neuronal as well as non-neuronal cells is still unknown, there is evidence to suggest these channels may belong to TRP-like channel family. The signaling pathway involved in this activation of the TIDA neurons by PRL has also not been clearly identified. Furthermore, the activation of these neurons at resting membrane potentials required a substantial amount of PRL, which is typical of concentrations observed during pathological hyperprolactinaemia resulting from pituitary adenomas.64 Even so, PRL concentrations (20–40 nM) observed during pregnancy and lactation can produce action potential firing in TIDA neurons via an unknown mechanism.56 Interestingly, non-neuronal cells can be activated by PRL concentrations as low as 1nM.63,65

Activation of neurons can lead to action potential firing, inward currents at resting membrane potential as well as intracellular Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i) accumulation. Even though PRL-evoked [Ca2+]i rise has been studied in non-neuronal cells,63 similar studies in neurons are mostly lacking. In non-neuronal cells, PRL-evoked [Ca2+]i rise is mediated by intracellular stores and by an unknown plasma membrane channel activated by PRL (see above).63 In neurons, it is presumed that PRL can produce Ca2+ influx via both TRP-like channels and L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (Fig. 3).58 The role of intracellular stores in PRL-evoked [Ca2+]i rise in neurons is unknown. Moreover, PRL-induced [Ca2+]i rise depends on neuronal type. Thus, some data indicate that GABAergic, but not dopaminergic TIDA neurons, react to PRL with a rapid increase in [Ca2+]i.66

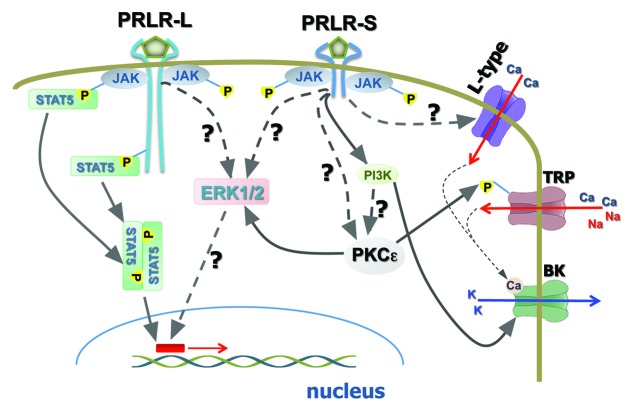

Figure 3. Schematic of cellular signaling pathways via PRLR-L and PRLR-S in neurons. PRLR long (PRLR-L) and PRLR short (PRLR-S) isoforms control different signaling pathways in neurons. PRLR-L, but not PRLR-S activates JAK/STAT5 and Src kinase (i.e., Fyn) pathways. MAPK is probably activated by both isoforms. PI3 and PKC kinases are likely activated by PRLR-S in neurons. PRLR-S mediated pathways are critical for rapid modulation of neuronal functions. Activation of neurons by PRL undergo via unknown pathways, which may involve PKC.

Regulation of TRP Channels by PRL in Sensory Neurons

Sensory neurons play a key role in nociception/pain. Certain TRP channels, especially TRPV1, TRPA1 and TRPM8 are highly expressed in sensory neurons and contribute to nociception/hypersensitivity/pain.67-71 Strong evidence links these channels to mediating sensory neuronal activities by modulating the neuronal threshold of activation and efficiency of neurotransmission between sensory and spinal cord neurons.72-75 A variety of pain conditions such as those associated with surgical procedures,9,76 migraine,11,34 burn,30 rheumatoid arthritis,26,27 and osteoarthritis33 trigger an increase in serum PRL levels in men, and even more so in women. Recent evidence also suggests that inflammation, tissue injury and trauma lead to a sex-dependent up-regulation in extra-pituitary PRL in the vicinity of peripheral and central terminals of sensory neurons.7,8 Interestingly, TRPV1 activities are enhanced by concentrations of PRL as low as 10–25ng/ml in DRG neurons from estrous female mice.8 In contrast, TRPV1 in DRG neurons from male mice requires > 0.8–1ug/ml PRL for up-regulation of activities.8 Similar contrasting results were observed in the regulation of TRPV1 activities by PRL in TG neurons from female ovariectomized (OVX) vs. OVX with estrogen replacement (OVX-E2) rats.39 These results showed that PRL (100ng/ml; ≈4nM) up-regulates the activity of TRPV1 in neurons from OVX-E2 rats, but not in rats with OVX alone,39 thus demonstrating influence of estrogen. Moreover, TRPV1 is not even sensitized by 1ug/ml PRL in sensory neurons from OVX rats.39 PRL is also capable of increasing TRPA1 and TRPM8 activities in a sex-dependent manner in a subset of DRG neurons from mice.8 In summary, PRL concentrations increase to 25–100ng/ml within both peripheral tissues and the lumbar spinal cord of females after inflammation and trauma,7,8,29 and this concentration is effective in enhancing TRPV1, TRPA1 and TRPM8 activities in sensory neurons of female, but not male rodents.8 Together, these findings suggest possible important contributions of PRL to the regulation of nociceptors after inflammatory and trauma in a sex-dependent manner.

PRL and Rapid Signaling Pathways in Neurons

Activation of PRLR initiates multiple second-messenger cascades, including JAK/STAT5, MAPK and PI3-kinase signaling pathways in non-neuronal cells.1,2 The role of these cascades in transcription control and endpoints such as cell differentiation, proliferation and survival of non-neuronal cells are relatively well studied.2 There is a general agreement that a majority of these long-lasting PRL effects in non-neuronal as well as neuronal cells are mediated via PRLR-L and a recruitment of the JAK/STAT5 pathway or at times the MAPK pathway (Fig. 3).1 Multiple studies performed in the nervous system suggest that besides long-lasting effects, neuronal responses to PRL can also be as fast as 1–5 min.8,40,56,58 These rapid responses are essential for the control of neuronal excitability as well as modulation of neuronal circuitries by PRL. In this section, we will present current views on the mechanisms underlying PRL-induced rapid signaling pathway in neurons.

PRLR expression in a heterologous system along with reconstitution of PRLR in PRLR KO sensory neurons showed that the transient/rapid effects of PRL on TRPV1 activities are mediated by PRLR-S.40 PRLR-L does not have any direct involvement in the transient modulation of TRPV1 by PRL. However, PRLR-L can suppress PRLR-S function, and this suppression can indirectly inhibit TRPV1 activity.40 The C-terminal portion of PRLR-L (290–540 aa rat clone), especially the 290–430aa domain containing Box2 (Fig. 1), contributes to inhibition of PRLR-S function.40 PRLR-S has a short and unique amino acid C-terminal sequence (30 aa) that does not contain any noticeable motifs for activation of kinases. This could suggest that perhaps both PRLR-L and PRLR-S have the potential for rapid signaling. However, this capability is suppressed for PRLR-L homodimers. Altogether, the rapid PRL effects in neurons could be mediated mainly by the PRLR-S homodimer (Fig. 3), which is extensively expressed in the nervous system (see Table 1). In sensory neurons, expressions of PRLR-L and PRLR-S seldom overlap.40 In the CNS, PRLR-L, and PRLR-S expression overlaps are common.48,49 In such circumstances, it is not clear which cellular mechanisms are responsible for separating the effects of PRLR-L and PRLR-S when expressed together in the same neurons.

Studies on signaling mechanisms responsible for the PRL (0.01–1ug/ml) regulation of hypothalamic neuroendocrine dopaminergic (NEDA) neurons demonstrated that PRL rapidly induces synthesis of catecholamine via protein kinase A (PKA) and C (PKC), but not Ca2+-dependent calmodulin kinase-II (CaMKII) pathways.77 PRL application also led to a PKC-dependent activation of ERK1/2 within the MAPK pathway (Fig. 3).77 Interestingly, PRL-activated transcription does not involve PKA, PKC, CaMKII, or ERK1/277. The role of PRL-triggered rapid signaling pathways in neurons was further studied in TRPV1 sensitization. Inhibition of several kinase pathways demonstrated that the transient actions of PRL on TRPV1 activities in sensory neurons are directed by PI3-kinase or PKC (Fig. 3).40 PKA and Src-kinase inhibitors however failed to affect TRPV1 activity enhancement by PRL.40 Detailed investigation showed that the main PKC isoform involved in mediating PRL effects on TRPV1 in sensory neurons is PKCε40. However, it is not clear whether the PKC pathway is downstream of the PI3-kinase pathway (Fig. 3). Rapid induction of PI3-kinase by PRL in neurons of the CNS has been reported, and includes the suppression of BK-type Ca2+-dependent K+-currents in TIDA neurons by way of the PI3-kinase pathway (Fig. 3).58 In summary, it appears that PRL activates two principally distinct signaling pathways in neurons. The first involves PRLR-L and the phosphorylation of STAT5, leading to long-lasting effects based on transcription activation (Fig. 3). The second pathway recruits PRLR-S, leading to rapid activation of PI3-kinase, ERK1/2 and/or PKC, with subsequent modulation of neuronal channels, excitability and neurotransmission (Fig. 3). The schematic presented in Figure 3 is a simplified pathway, but underscores the primary signaling events following activation of neurons by endogenous or exogenous PRL. PI3-kinase, PKC and ERK1/2 can regulate a variety of ligand- and voltage-gated channels in neurons. Thus, PKC activation results in production of diacylglycerol (DAG), a potent activator of many TRPC channels.78,79 This production of DAG may explain how PRL activates TIDA neurons at a resting membrane potential via TRPC-like channels.58 Finally, it must be taken into account that PRL regulation of certain pathways and kinase recruitments could be cell-dependent. Thus, kinases can influence each other’s activities, and in certain neurons, PI3-kinase or PKC could be directed by PRLR-L.

Regulation of Neuronal Excitability by PRL

To fulfill its function in the nervous system, PRL has to regulate spontaneous or evoked neuronal activities (i.e., firing rates). There are several well characterized neuronal circuitries in which PRL exhibits such regulations. The magnocellular neurons of the supraoptic (SON) and paraventricular (PVN) nuclei express oxytocin and demonstrate spontaneous firing.80 The magnocellular neurons are highly responsive to PRL, which up-regulates or inhibits oxytocin secretion depending on physiological conditions.54,81 Both PRLR-L and PRLR-S have been identified in the SON and PVN48,49 (Table 1). Spontaneous firing rates in oxytocin neurons, which are identified by responsiveness to cholecystokinin (CKK), are suppressed by PRL (1ug/ml) in non-pregnant and non-lactating diestrous rats.82 PRL (100 ng/ml) is also able to elicit hyperpolarizing currents in the magnocellular neurons of female rats at membrane potentials more negative than -60 mV,83 leading to the inhibition of firing rates. Interestingly, PRL shows both excitatory and inhibitory effects on spontaneous activities of SON oxytocin neurons of male rats.80 The mechanisms underlying the actions of PRL on spontaneous firing activities in oxytocin neurons of female and male rats are not known as yet.

In TIDA neurons, PRL (>40 nM) generates large inward currents at positive holding potentials that can influence action potential shape. Indeed, PRL broadens action potential width by ≈20% in TIDA neurons.58 Broadening of action potentials is a hallmark indicator for modulation of voltage-gated Ca2+ and/or BK-type Ca2+-dependent K+ channels.84 Even small changes in action potential width could lead to a several-fold rise of synaptic neurotransmitter release.85 Further, investigation into the mechanisms underlying an increase in action potential width and induction of inward currents by PRL at positive potentials revealed that PRL stimulates Ca2+ influx into TIDA neurons via L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channel (VGCC).58 PRL-activated inward current at +40 mV was blocked by paxilline, a BK-type Ca2+-dependent K+ channel blocker, but not affected by the SK-type Ca2+-dependent K+ channel blocker, UCL1684.58 Altogether, PRL modulates the shape of action potentials and can increase neurotransmitter release at pre-synaptic sites of TIDA neurons by inhibiting BK-type Ca2+-dependent K+ channels coupled to Ca2+ influx via L-type VGCC.58 Moreover, PRL modulation of BK channels via PI3-kinase does not involve a JAK2 pathway.58 This suggests that rapid effects of PRL in TIDA neurons may be mediated via PRLR-S, and may also involve PKC.

There is a substantial difference in the effects of PRL on BK and other K+ channels in non-neuronal cells compared with those in neurons. First, it appears that in non-neuronal cells PRL exerts transient effects through PRLR-L via the JAK2 pathway.63,86 Second, in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) and glioma cells, PRL (4 nM) increases activity of BK-type Ca2+-dependent K+ channels.63,86 PRL has also shown to activate other K+ currents and alter open probability in a prostate cancer cell line via a Fyn pathway.87 This difference in effect of PRL in neuronal as compared with non-neuronal cells suggests involvement either specialized adaptor proteins for PRLR or different cellular sub-domain organization (i.e., lipid rafts for example).

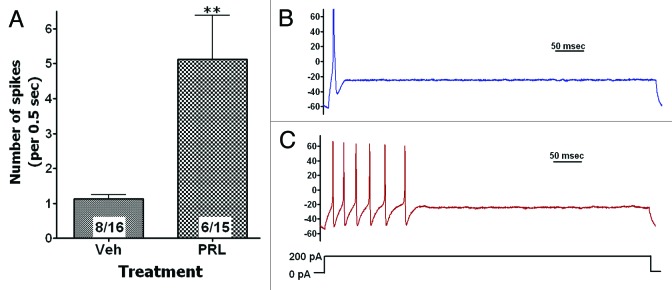

The regulation of evoked neuronal activities (i.e., firing rates) by PRL is the least studied property of this multifunctional hormone. Since PRLR is expressed on sensory neurons, they could be physiologically relevant and a suitable model to study regulation of evoked neuronal activities by PRL. Action potential firing in sensory neurons can be evoked by environmental cues acting on peripheral terminals, or by endogenous agents released in dorsal horn of spinal cord (or brain stem) and activating central terminals of sensory neurons.73 Under pathophysiological conditions, PRL can assess peripheral and central sensory neuronal terminals via an autocrine, paracrine and/or endocrine mechanisms.7,8,29 Action potential firing can be modeled by injecting current into neurons recorded in whole-cell configuration under current clamp mode88-90 (Fig. 4B). Acutely cultured DRG neurons from estrous rat females showed a low firing rate upon current injection (Fig. 4A and B). However, following pre-treatment (15 min) with PRL (4nM; 100ng/ml), DRG firing rates were substantially increased (Fig. 4A and C). Firing rates are controlled by a wide variety of voltage-gated channels. Thus, the post-translational or transcriptional inhibition of K+-channels, such as BK-type, SK-type and/or M-type by PRL can increase the firing rate of neurons.89-93 Since contribution of voltage-gated Na+ channels (VGSC) to firing rates are well documented,94,95 enhancement of VGSC activities or threshold of activation by PRL could likely lead to an increase in neuronal excitability.

Figure 4. PRL increases excitability of sensory neurons. (A) Pre-treatment of rat female DRG sensory neurons for 15 min with PRL (100ng/ml) increased frequency of evoked action potentials (AP or spikes). Whole-cell current clump recording at physiological conditions were performed by stepping current from 0 to 200pA for 500 msec. Numbers of analyzed cells and cells generating at least single AP are indicated within boxes. Statistic is un-paired t test (**P < 0.01). Representative traces from neurons treated with vehicle (B) or PRL (C) are shown. Y-axis is in mV. Neuron stimulation protocol is illustrated.

Conclusion

Although PRL controls a vast number of physiologically critical functions in the nervous system, we are still far from understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying these processes. Nonetheless, research on PRL mediated regulation of neuronal functions, excitability, neurotransmission and involved channels has recently made notable progress. We now know that PRL can generate small currents in neurons via putative TRP-like Ca2+ channels and influx Ca2+ into neurons via L-type VGCC. We also know that rapid PRL responses in neurons are probably mediated by the short PRLR isoform via PI3-kinase and PKC pathways. Importantly, PRL is able to rapidly modulate evoked firing rates and neurotransmission by suppressing certain K+ channels in neurons. This is a principal difference for neuronal PRL-induced pathways compared with non-neuronal pathways where PRL activates K+ channels that will lead to overall inhibition. Although we are now just beginning to understand the mechanisms responsible for PRL actions in the nervous system, there are numerous critically important unaddressed aspects regarding the regulation of neuronal functions by PRL. In this respect, several understudied issues include: (1) Mechanisms contributing to extra-pituitary PRL production in a variety of neurological disorders. (2) The role of PRL in orchestrating the regulation of neuronal excitability in physiological vs. pathophysiological conditions. (3) Differences in the regulation of PRL and PRLR expressions in neurons of males and females as compared with pregnant or lactating females. (4) Defining the specific cellular mechanisms involved in the PRL regulation of the different PRL-responsive neuronal subtypes. (5) Identifying mechanisms involved in regulation of a variety of ligand and voltage-gated channels by PRL in neurons. As our understanding of PRL actions continues to evolve, future research will hopefully focus on some of these important issues in attempts to even better understand the mechanisms of action of this exciting and intriguing hormone on a wide variety of physiological and pathophysiological conditions affecting the nervous system.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Dr Sergei Belugin, Dr Anibal Diogenes, Dr Vincent Goffin, Dr Shivani Ruparel, Phoebe Scotland, Jie Li, Dustin Green, and Mahuiyang Rong for fruitful discussion and suggestions for this review, and productive involvement in the projects related prolactin functions in the nervous system. Research was supported by grants AHA44081 (to M.J.P) from American Heart Association and DE014928 (to A.N.A.) from NIH/NIDCR.

References

- 1.Bole-Feysot C, Goffin V, Edery M, Binart N, Kelly PA. Prolactin (PRL) and its receptor: actions, signal transduction pathways and phenotypes observed in PRL receptor knockout mice. Endocr Rev. 1998;19:225–68. doi: 10.1210/edrv.19.3.0334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ben-Jonathan N, LaPensee CR, LaPensee EW. What can we learn from rodents about prolactin in humans? Endocr Rev. 2008;29:1–41. doi: 10.1210/er.2007-0017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Larsen CM, Grattan DR. Prolactin, neurogenesis, and maternal behaviors. Brain Behav Immun. 2012;26:201–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.07.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grattan DR, Kokay IC. Prolactin: a pleiotropic neuroendocrine hormone. J Neuroendocrinol. 2008;20:752–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2008.01736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mena F, González-Hernández A, Navarro N, Castilla A, Morales T, Rojas-Piloni G, Martínez-Lorenzana G, Condés-Lara M. Prolactin fractions from lactating rats elicit effects upon sensory spinal cord cells of male rats. Neuroscience. 2013;248C:552–61. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noel MB, Woodside B. Effects of systemic and central prolactin injections on food intake, weight gain, and estrous cyclicity in female rats. Physiol Behav. 1993;54:151–4. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(93)90057-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patil MJ, Green DP, Henry MA, Akopian AN. Sex-dependent roles of prolactin and prolactin receptor in postoperative pain and hyperalgesia in mice. Neuroscience. 2013;253:132–41. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.08.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patil MJ, Ruparel SB, Henry MA, Akopian AN. Prolactin regulates TRPV1, TRPA1, and TRPM8 in sensory neurons in a sex-dependent manner: Contribution of prolactin receptor to inflammatory pain. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2013;305:E1154–64. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00187.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sakellaris G, Petrakis I, Makatounaki K, Arbiros I, Karkavitsas N, Charissis G. Effects of ropivacaine infiltration on cortisol and prolactin responses to postoperative pain after inguinal hernioraphy in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39:1400–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cavestro C, Rosatello A, Marino MP, Micca G, Asteggiano G. High prolactin levels as a worsening factor for migraine. J Headache Pain. 2006;7:83–9. doi: 10.1007/s10194-006-0272-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bosco D, Belfiore A, Fava A, De Rose M, Plastino M, Ceccotti C, Mungari P, Iannacchero R, Lavano A. Relationship between high prolactin levels and migraine attacks in patients with microprolactinoma. J Headache Pain. 2008;9:103–7. doi: 10.1007/s10194-008-0016-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larsen CM, Grattan DR. Exposure to female pheromones during pregnancy causes postpartum anxiety in mice. Vitam Horm. 2010;83:137–49. doi: 10.1016/S0083-6729(10)83005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mak GK, Weiss S. Paternal recognition of adult offspring mediated by newly generated CNS neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:753–8. doi: 10.1038/nn.2550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pathipati P, Gorba T, Scheepens A, Goffin V, Sun Y, Fraser M. Growth hormone and prolactin regulate human neural stem cell regenerative activity. Neuroscience. 2011;190:409–27. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walsh RJ, Slaby FJ, Posner BI. A receptor-mediated mechanism for the transport of prolactin from blood to cerebrospinal fluid. Endocrinology. 1987;120:1846–50. doi: 10.1210/endo-120-5-1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Login IS, MacLeod RM. Prolactin in human and rat serum and cerebrospinal fluid. Brain Res. 1977;132:477–83. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(77)90196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freeman ME, Kanyicska B, Lerant A, Nagy G. Prolactin: structure, function, and regulation of secretion. Physiol Rev. 2000;80:1523–631. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.4.1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ben-Jonathan N, Mershon JL, Allen DL, Steinmetz RW. Extrapituitary prolactin: distribution, regulation, functions, and clinical aspects. Endocr Rev. 1996;17:639–69. doi: 10.1210/edrv-17-6-639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soares MJ. The prolactin and growth hormone families: pregnancy-specific hormones/cytokines at the maternal-fetal interface. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2004;2:51. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-2-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Noel GL, Suh HK, Frantz AG. Prolactin release during nursing and breast stimulation in postpartum and nonpostpartum subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1974;38:413–23. doi: 10.1210/jcem-38-3-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cox DB, Owens RA, Hartmann PE. Blood and milk prolactin and the rate of milk synthesis in women. Exp Physiol. 1996;81:1007–20. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1996.sp003985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Straub RH, Zeuner M, Lock G, Schölmerich J, Lang B. High prolactin and low dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate serum levels in patients with severe systemic sclerosis. Br J Rheumatol. 1997;36:426–32. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/36.4.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hilty C, Brühlmann P, Sprott H, Gay RE, Michel BA, Gay S, Neidhart M. Altered diurnal rhythm of prolactin in systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol. 2000;27:2160–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jimena P, Aguirre MA, López-Curbelo A, de Andrés M, Garcia-Courtay C, Cuadrado MJ. Prolactin levels in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a case controlled study. Lupus. 1998;7:383–6. doi: 10.1191/096120398678920361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walker SE. Modulation of hormones in the treatment of lupus. Am J Manag Care. 2001;7(Suppl):S486–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mateo L, Nolla JM, Bonnin MR, Navarro MA, Roig-Escofet D. High serum prolactin levels in men with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1998;25:2077–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Straub RH, Georgi J, Helmke K, Vaith P, Lang B. In polymyalgia rheumatica serum prolactin is positively correlated with the number of typical symptoms but not with typical inflammatory markers. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2002;41:423–9. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/41.4.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Bellis A, Bizzarro A, Pivonello R, Lombardi G, Bellastella A. Prolactin and autoimmunity. Pituitary. 2005;8:25–30. doi: 10.1007/s11102-005-5082-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scotland PE, Patil M, Belugin S, Henry MA, Goffin V, Hargreaves KM, Akopian AN. Endogenous prolactin generated during peripheral inflammation contributes to thermal hyperalgesia. Eur J Neurosci. 2011;34:745–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07788.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dugan AL, Malarkey WB, Schwemberger S, Jauch EC, Ogle CK, Horseman ND. Serum levels of prolactin, growth hormone, and cortisol in burn patients: correlations with severity of burn, serum cytokine levels, and fatality. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2004;25:306–13. doi: 10.1097/01.BCR.0000124785.32516.CB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reiner Z, Oresković M, Ribarić K. Endocrine responses to head and neck surgery in men. Acta Otolaryngol. 1987;103:665–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chan V, Wang C, Yeung RT. Pituitary-thyroid responses to surgical stress. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) 1978;88:490–8. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.0880490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fojtíková M, Tomasová Studýnková J, Filková M, Lacinová Z, Gatterová J, Pavelka K, Vencovský J, Senolt L. Elevated prolactin levels in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: association with disease activity and structural damage. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2010;28:849–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cassidy EM, Tomkins E, Sharifi N, Dinan T, Hardiman O, O’Keane V. Differing central amine receptor sensitivity in different migraine subtypes? A neuroendocrine study using buspirone. Pain. 2003;101:283–90. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00335-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cohen H, Benjamin J, Kaplan Z, Kotler M. Administration of high-dose ketoconazole, an inhibitor of steroid synthesis, prevents posttraumatic anxiety in an animal model. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2000;10:429–35. doi: 10.1016/S0924-977X(00)00105-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.DeVito WJ, Avakian C, Stone S, Ace CI. Estradiol increases prolactin synthesis and prolactin messenger ribonucleic acid in selected brain regions in the hypophysectomized female rat. Endocrinology. 1992;131:2154–60. doi: 10.1210/endo.131.5.1425416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Griffond B, Deray A, Fellmann D, Ciofi P, Croix D, Bugnon C. Colocalization of prolactin- and dynorphin-like substances in a neuronal population of the rat lateral hypothalamus. Neurosci Lett. 1993;156:91–5. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90447-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Griffond B, Deray A, Jacquemard C, Fellmann D, Bugnon C. Prolactin immunoreactive neurons of the rat lateral hypothalamus: immunocytochemical and ultrastructural studies. Brain Res. 1994;635:179–86. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91437-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Diogenes A, Patwardhan AM, Jeske NA, Ruparel NB, Goffin V, Akopian AN, Hargreaves KM. Prolactin modulates TRPV1 in female rat trigeminal sensory neurons. J Neurosci. 2006;26:8126–36. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0793-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Belugin S, Diogenes AR, Patil MJ, Ginsburg E, Henry MA, Akopian AN. Mechanisms of transient signaling via short and long prolactin receptor isoforms in female and male sensory neurons. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:34943–55. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.486571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kossiakoff AA. The structural basis for biological signaling, regulation, and specificity in the growth hormone-prolactin system of hormones and receptors. Adv Protein Chem. 2004;68:147–69. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3233(04)68005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boutin JM, Jolicoeur C, Okamura H, Gagnon J, Edery M, Shirota M, Banville D, Dusanter-Fourt I, Djiane J, Kelly PA. Cloning and expression of the rat prolactin receptor, a member of the growth hormone/prolactin receptor gene family. Cell. 1988;53:69–77. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90488-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qazi AM, Tsai-Morris CH, Dufau ML. Ligand-independent homo- and heterodimerization of human prolactin receptor variants: inhibitory action of the short forms by heterodimerization. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:1912–23. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goupille O, Daniel N, Bignon C, Jolivet G, Djiane J. Prolactin signal transduction to milk protein genes: carboxy-terminal part of the prolactin receptor and its tyrosine phosphorylation are not obligatory for JAK2 and STAT5 activation. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1997;127:155–69. doi: 10.1016/S0303-7207(97)04005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brown RS, Kokay IC, Herbison AE, Grattan DR. Distribution of prolactin-responsive neurons in the mouse forebrain. J Comp Neurol. 2010;518:92–102. doi: 10.1002/cne.22208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bennett E, McGuinness L, Gevers EF, Thomas GB, Robinson IC, Davey HW, Luckman SM. Hypothalamic STAT proteins: regulation of somatostatin neurones by growth hormone via STAT5b. J Neuroendocrinol. 2005;17:186–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2005.01296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mütze J, Roth J, Gerstberger R, Hübschle T. Nuclear translocation of the transcription factor STAT5 in the rat brain after systemic leptin administration. Neurosci Lett. 2007;417:286–91. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.02.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bakowska JC, Morrell JI. The distribution of mRNA for the short form of the prolactin receptor in the forebrain of the female rat. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2003;116:50–8. doi: 10.1016/S0169-328X(03)00213-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bakowska JC, Morrell JI. Atlas of the neurons that express mRNA for the long form of the prolactin receptor in the forebrain of the female rat. J Comp Neurol. 1997;386:161–77. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19970922)386:2<161::AID-CNE1>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chiu S, Wise PM. Prolactin receptor mRNA localization in the hypothalamus by in situ hybridization. J Neuroendocrinol. 1994;6:191–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.1994.tb00572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mann PE, Bridges RS. Prolactin receptor gene expression in the forebrain of pregnant and lactating rats. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2002;105:136–45. doi: 10.1016/S0169-328X(02)00401-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Perrot-Applanat M, Gualillo O, Buteau H, Edery M, Kelly PA. Internalization of prolactin receptor and prolactin in transfected cells does not involve nuclear translocation. J Cell Sci. 1997;110:1123–32. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.9.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sarkar DK. Evidence for prolactin feedback actions on hypothalamic oxytocin, vasoactive intestinal peptide and dopamine secretion. Neuroendocrinology. 1989;49:520–4. doi: 10.1159/000125161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Parker SL, Armstrong WE, Sladek CD, Grosvenor CE, Crowley WR. Prolactin stimulates the release of oxytocin in lactating rats: evidence for a physiological role via an action at the neural lobe. Neuroendocrinology. 1991;53:503–10. doi: 10.1159/000125764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nishihara M, Kimura F. Postsynaptic effects of prolactin and estrogen on arcuate neurons in rat hypothalamic slices. Neuroendocrinology. 1989;49:215–8. doi: 10.1159/000125117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brown RS, Piet R, Herbison AE, Grattan DR. Differential actions of prolactin on electrical activity and intracellular signal transduction in hypothalamic neurons. Endocrinology. 2012;153:2375–84. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Davidowa H, Plagemann A. Action of prolactin, prolactin-releasing peptide and orexins on hypothalamic neurons of adult, early postnatally overfed rats. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2005;26:453–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lyons DJ, Hellysaz A, Broberger C. Prolactin regulates tuberoinfundibular dopamine neuron discharge pattern: novel feedback control mechanisms in the lactotrophic axis. J Neurosci. 2012;32:8074–83. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0129-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lyons DJ, Horjales-Araujo E, Broberger C. Synchronized network oscillations in rat tuberoinfundibular dopamine neurons: switch to tonic discharge by thyrotropin-releasing hormone. Neuron. 2010;65:217–29. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Romanò N, Yip SH, Hodson DJ, Guillou A, Parnaudeau S, Kirk S, Tronche F, Bonnefont X, Le Tissier P, Bunn SJ, et al. Plasticity of hypothalamic dopamine neurons during lactation results in dissociation of electrical activity and release. J Neurosci. 2013;33:4424–33. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4415-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Clapham DE. TRP channels as cellular sensors. Nature. 2003;426:517–24. doi: 10.1038/nature02196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Qiu J, Fang Y, Rønnekleiv OK, Kelly MJ. Leptin excites proopiomelanocortin neurons via activation of TRPC channels. J Neurosci. 2010;30:1560–5. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4816-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ducret T, Vacher AM, Vacher P. Effects of prolactin on ionic membrane conductances in the human malignant astrocytoma cell line U87-MG. J Neurophysiol. 2004;91:1203–16. doi: 10.1152/jn.00710.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Eljarmak D, Lis M, Cantin M, Carrière PD, Collu R. Effects of chronic bromocriptine treatment of an estrone-induced, prolactin-secreting rat pituitary adenoma. Horm Res. 1985;21:160–7. doi: 10.1159/000180041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ducret T, Boudina S, Sorin B, Vacher AM, Gourdou I, Liguoro D, Guerin J, Bresson-Bepoldin L, Vacher P. Effects of prolactin on intracellular calcium concentration and cell proliferation in human glioma cells. Glia. 2002;38:200–14. doi: 10.1002/glia.10056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kolbinger W, Beyer C, Föhr K, Reisert I, Pilgrim C. Diencephalic GABAergic neurons in vitro respond to prolactin with a rapid increase in intracellular free calcium. Neuroendocrinology. 1992;56:148–52. doi: 10.1159/000126222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Caterina MJ, Schumacher MA, Tominaga M, Rosen TA, Levine JD, Julius D. The capsaicin receptor: a heat-activated ion channel in the pain pathway. Nature. 1997;389:816–24. doi: 10.1038/39807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kwan KY, Allchorne AJ, Vollrath MA, Christensen AP, Zhang DS, Woolf CJ, Corey DP. TRPA1 contributes to cold, mechanical, and chemical nociception but is not essential for hair-cell transduction. Neuron. 2006;50:277–89. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Colburn RW, Lubin ML, Stone DJ, Jr., Wang Y, Lawrence D, D’Andrea MR, Brandt MR, Liu Y, Flores CM, Qin N. Attenuated cold sensitivity in TRPM8 null mice. Neuron. 2007;54:379–86. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tai C, Zhu S, Zhou N. TRPA1: the central molecule for chemical sensing in pain pathway? J Neurosci. 2008;28:1019–21. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5237-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tominaga M, Tominaga T. Structure and function of TRPV1. Pflugers Arch. 2005;451:143–50. doi: 10.1007/s00424-005-1457-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gregus AM, Doolen S, Dumlao DS, Buczynski MW, Takasusuki T, Fitzsimmons BL, Hua XY, Taylor BK, Dennis EA, Yaksh TL. Spinal 12-lipoxygenase-derived hepoxilin A3 contributes to inflammatory hyperalgesia via activation of TRPV1 and TRPA1 receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:6721–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110460109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Patwardhan AM, Scotland PE, Akopian AN, Hargreaves KM. Activation of TRPV1 in the spinal cord by oxidized linoleic acid metabolites contributes to inflammatory hyperalgesia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:18820–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905415106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Grace MS, Belvisi MG. TRPA1 receptors in cough. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2011;24:286–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chun JN, Lim JM, Kang Y, Kim EH, Shin YC, Kim HG, Jang D, Kwon D, Shin SY, So I, et al. A network perspective on unraveling the role of TRP channels in biology and disease. Pflugers Arch. 2014;466:173–82. doi: 10.1007/s00424-013-1292-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Noel GL, Suh HK, Stone JG, Frantz AG. Human prolactin and growth hormone release during surgery and other conditions of stress. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1972;35:840–51. doi: 10.1210/jcem-35-6-840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ma FY, Grattan DR, Goffin V, Bunn SJ. Prolactin-regulated tyrosine hydroxylase activity and messenger ribonucleic acid expression in mediobasal hypothalamic cultures: the differential role of specific protein kinases. Endocrinology. 2005;146:93–102. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Montell C. The TRP superfamily of cation channels. Sci STKE. 2005;2005:re3. doi: 10.1126/stke.2722005re3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Montell C, Birnbaumer L, Flockerzi V. The TRP channels, a remarkably functional family. Cell. 2002;108:595–8. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00670-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Townsend J, Cave BJ, Norman MR, Flynn A, Uney JB, Tortonese DJ, Wakerley JB. Effects of prolactin on hypothalamic supraoptic neurones: evidence for modulation of STAT5 expression and electrical activity. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2005;26:125–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Carter DA, Lightman SL. Oxytocin responses to stress in lactating and hyperprolactinaemic rats. Neuroendocrinology. 1987;46:532–7. doi: 10.1159/000124876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kokay IC, Bull PM, Davis RL, Ludwig M, Grattan DR. Expression of the long form of the prolactin receptor in magnocellular oxytocin neurons is associated with specific prolactin regulation of oxytocin neurons. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;290:R1216–25. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00730.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sirzen-Zelenskaya A, Gonzalez-Iglesias AE, Boutet de Monvel J, Bertram R, Freeman ME, Gerber U, Egli M. Prolactin induces a hyperpolarising current in rat paraventricular oxytocinergic neurones. J Neuroendocrinol. 2011;23:883–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2011.02207.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Shao LR, Halvorsrud R, Borg-Graham L, Storm JF. The role of BK-type Ca2+-dependent K+ channels in spike broadening during repetitive firing in rat hippocampal pyramidal cells. J Physiol. 1999;521:135–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00135.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sabatini BL, Regehr WG. Control of neurotransmitter release by presynaptic waveform at the granule cell to Purkinje cell synapse. J Neurosci. 1997;17:3425–35. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-10-03425.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Prevarskaya NB, Skryma RN, Vacher P, Daniel N, Djiane J, Dufy B. Role of tyrosine phosphorylation in potassium channel activation. Functional association with prolactin receptor and JAK2 tyrosine kinase. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:24292–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.41.24292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Van Coppenolle F, Skryma R, Ouadid-Ahidouch H, Slomianny C, Roudbaraki M, Delcourt P, Dewailly E, Humez S, Crépin A, Gourdou I, et al. Prolactin stimulates cell proliferation through a long form of prolactin receptor and K+ channel activation. Biochem J. 2004;377:569–78. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Linley JE, Rose K, Patil M, Robertson B, Akopian AN, Gamper N. Inhibition of M current in sensory neurons by exogenous proteases: a signaling pathway mediating inflammatory nociception. J Neurosci. 2008;28:11240–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2297-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Pagadala P, Park CK, Bang S, Xu ZZ, Xie RG, Liu T, Han BX, Tracey WD, Jr., Wang F, Ji RR. Loss of NR1 subunit of NMDARs in primary sensory neurons leads to hyperexcitability and pain hypersensitivity: involvement of Ca(2+)-activated small conductance potassium channels. J Neurosci. 2013;33:13425–30. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0454-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Liu B, Linley JE, Du X, Zhang X, Ooi L, Zhang H, Gamper N. The acute nociceptive signals induced by bradykinin in rat sensory neurons are mediated by inhibition of M-type K+ channels and activation of Ca2+-activated Cl- channels. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:1240–52. doi: 10.1172/JCI41084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mucha M, Ooi L, Linley JE, Mordaka P, Dalle C, Robertson B, Gamper N, Wood IC. Transcriptional control of KCNQ channel genes and the regulation of neuronal excitability. J Neurosci. 2010;30:13235–45. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1981-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Crest M, Gola M. Large conductance Ca(2+)-activated K+ channels are involved in both spike shaping and firing regulation in Helix neurones. J Physiol. 1993;465:265–87. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Nelson AB, Krispel CM, Sekirnjak C, du Lac S. Long-lasting increases in intrinsic excitability triggered by inhibition. Neuron. 2003;40:609–20. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00641-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Eijkelkamp N, Linley JE, Baker MD, Minett MS, Cregg R, Werdehausen R, Rugiero F, Wood JN. Neurological perspectives on voltage-gated sodium channels. Brain. 2012;135:2585–612. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Momin A, Wood JN. Sensory neuron voltage-gated sodium channels as analgesic drug targets. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2008;18:383–8. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2008.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]