Abstract

Background

Protein cross-coupling reactions demand high yields, especially if the products are intended for bioanalytics, like enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays. Amongst other factors, the coupling yield depends on the concentration of the proteins being used for coupling. Protein supercharging of enzymes can increase the solubility dramatically, which could promote enzyme-antibody coupling reactions. A highly soluble, supercharged variant of the enzyme human enteropeptidase light chain was created by a site-directed mutagenesis of surface amino acids, used for the production of an antibody-enzyme conjugate and compared to the wild type enzyme.

Results

Wild type and mutant enzyme could successfully be cross-coupled to an antibody to give antibody-enzyme conjugates suitable for ELISA. Their assay performances and the analysis of the enzyme activities in solution demonstrate that the supercharged version could be coupled to a higher extent, which resulted in better assay sensitivities. The generated conjugate, based on the supercharged enzyme, was feasible as a reporter molecule in a sandwich ELISA and allowed the detection of epidermal growth factor with a detection limit of 15.63 pg (25 pmol/L).

Conclusion

The highly soluble, surface supercharged, human enteropeptidase light chain mutant provided better yields in coupling the enzyme to an antibody than the wild type. This is most likely related to the higher protein concentration during the coupling. The data suggest that supercharging can be applied favourably to other proteins which have to be covalently linked to other polymers or surfaces with high yields without losses in enzyme activity or specificity.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12896-014-0088-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: ELISA, Human enteropeptidase light chain, Protein-protein coupling, Surface supercharging

Background

The extraordinary feature of enzymes to catalyze reactions with a high selectivity is utilized in a broad field of applications, including the paper-, food- and pharmaceutical industry [1]. Besides this, enzymes are used as bioanalytical tools, such as in biosensors or as amplifying agents in immunoassays. One prominent application is the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), where an antibody-enzyme conjugate is used for the detection and quantification of analytes. Due to its compatibility to complex samples, this approach became a method of high significance in routine analysis and research [2]. Most applications have in common, that the enzyme has to be immobilized. Whilst adsorption, entrapment and covalent-cross coupling procedures are feasible for continuous flow-through processes in industry [3], the latter is essential for the production of ELISA conjugates. The application in this type of immunoassay requires a synthesis protocol which ideally results in a conjugate with an enzyme:antibody ratio of at least 1:1, without causing side-products and, more importantly, remaining unconjugated antibody [4].

Different coupling strategies have been developed, especially for the popular reporter enzymes horseradish peroxidase, alkaline phosphatase and β-galactosidase. The coupling reaction for the first enzyme-antibody conjugate applied in ELISA was based on the homobifunctional linker glutaraldehyde [5,6]. Although the resulting enzyme-protein complex partially retains its enzymatic activity and immunological specificity, it suffers from the formation of inactive homo-conjugates and polymers [4]. Thus, heterobifunctional linker molecules have been developed, which can react to two different functional groups, such as amino groups, cis-hydroxyl-groups in carbohydrates and thiol groups. As the coupling efficiency is also dependent on the amount of coupling sites on the proteins [7], the modification should occur to a large extend. Additionally, high concentrations of proteins will result in higher yields of coupling product, since diffusion- and orientation-controlled ligation processes become more likely. Although the commonly used enzymes in ELISA allow a satisfactory performance for most applications, the adoption of other enzymes might be interesting in terms of substrate diversity and sensitivity.

In 2007, Lawrence et al. presented a method to decrease protein aggregation tendencies by specific mutations of residues on protein surfaces. This specific replacement of surface amino acids with either acidic or basic amino acids was termed supercharging, as the net charge of the mutants were more positive or negative [8]. Supercharged proteins have been engineered to overcome limitations of macromolecule delivery into mammalian cells [9] and to increase thermal stability of antibody fragments [10]. This strategy might also be useful to improve the yield of protein-protein coupling reactions, especially the linking of enzymes to antibodies for immunological applications.

We adapted supercharging to the light chain of the human enteropeptidase in an earlier study and the resulting mutant, hEPl scC112S (N6D, G21D, G22D, C112S, N141D, K209E), showed a superior solubility and heat stability [11]. Here, we investigated the impact of enzyme supercharging on chemical crosslinking as exemplified for an antibody-enzyme conjugate. Therefore, hEPl scC112S and its wild type variant (hEPl wt) were conjugated to a secondary antibody and compared with respect to their assay performance.

Methods

Reagents

Enzymes (hEPl wt and hEPl scC112S) were expressed, refolded and purified in-house [11]. Polyclonal sheep-anti-mouse and donkey-anti-rabbit antibodies were from Dianova (Hamburg, Germany), monoclonal mouse-anti-EGF, EGF protein and polyclonal rabbit-anti-EGF were from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). Citric acid and Tween®20 were from Serva Electrophoresis (Heidelberg, Germany), Tris(hydroxymethyl)-aminomethan was from Applichem (Darmstadt, Germany). C6-Succinimidyl-4-formylbenzoate and C6-Succinimidyl-4-hydrazinonicotinate acetone hydrazone were from Acris Antibodies (Herford, Germany). Sodium chloride, hydrochlorid acid (conc.), Na2HPO4x12H2O, KH2PO4, GD4K-na and DMSO were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Taufkirchen, Germany) in the highest purities available. Roti®-Block was ordered from Roth (Karlsruhe, Germany). Bovine serum albumin standard was from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Rockford, USA). Deionized water was obtained from a Purelab Ultra water purification system (ELGA LabWater, Celle, Germany; 18.2 MΩ*cm).

Antibody-enzyme coupling

A 1.5-fold molar excess of enzyme (hEPl wt: 90 μg/mL or hEPl scC112S: 440 μg/mL) was coupled to a sheep-anti-mouse antibody (2.4 g/L) after dialysing the proteins against modification buffer (0.1 mol/L phosphate buffer, 0.15 mol/L NaCl, pH 8.0) separately for 16 hours at 4°C using a 12 kDa cut-off dialysis tube (Sigma-Aldrich). Afterwards, the antibody was mixed with 40 equivalents of C6-succinimidyl-4-formylbenzoate (9 g/L in DMF), while enzymes have been modified with 40 equivalents of C6-succinimidyl-4-hydrazinonicotinate acetone hydrazone (5.2 g/L in DMF). The reaction mixtures were incubated at room temperature for 3 hours and excess linker molecules were removed by dialysis against conjugation buffer (0.1 mol/L citric acid, 0.15 mol/L NaCl, pH 6.0) at 4°C. Antibody and enzyme solution were mixed and incubated at 4°C. After 20 hours, protein concentrations were determined using a Bradford assay according to standard protocols with bovine serum albumin as standard [12]. The solutions were used without further treatment.

The ELISA-conjugate was obtained by increasing the concentration of hEPl scC112S from 0.242 g/L to 3.6 g/L by lyophilisation from 5 mmol/L Tris-buffer (pH 8.0) and subsequent resolubilization of the enzyme in water. Coupling was performed as described above, using a donkey-anti-rabbit antibody (1.2 g/L) and a 10-fold molar excess of enzyme.

Enzyme assay

Kinetic characterization of the enzymes was performed in a 0.1 mol/L Tris–HCl buffer (pH 8.0, 10% DMSO) at room temperature using black 384-well plates (non-binding, Greiner Bio-one, Frickenhausen, Germany). GD4K-na in concentrations varying from 3.7 to 947 μmol/L was cleaved by addition of hEPl wt and hEPl scC112S (final concentration 10 nmol/L). The linear increase of released 2-naphthylamine was recorded on a Paradigm fluorescence reader (Molecular Devices, Ismaning, Germany) using a fluorescence cartridge (λex = 360/35 nm; λem = 465/35 nm; integration time 140 ms). All experiments were performed in triplicates.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

ELISA experiments were performed in black 384-well microtitre plates (high-binding, Greiner Bio-one, Frickenhausen, Germany) with an assay volume of 100 μL. All experiments were performed in triplicates.

Initial testing of the conjugate yield derived from the coupling with 1.5 equivalents hEPl wt or hEPl scC112S was determined using an affinity test. 100 μL of an in-house produced monoclonal antibody (HPT-104 [13], 2.25 μg/mL) were incubated at 4°C for 16 hours. After a threefold washing step using 200 μL washing buffer (phosphate buffered saline, 10 mmol/L phosphate, 0.3 mol/L NaCl, pH 7.4, 0.05% (v/v) Tween®20), free binding sites were blocked with 120 μL blocking buffer (0.5% (w/v) casein in washing buffer). After a further washing step, conjugate solutions were added with a total protein concentration of 2 μg/mL and incubated. After removal of unbound components by washing, signals were generated by addition of 50 μmol/L GD4K-na in assay buffer (0.1 mol/L Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 10% DMSO) and the fluorescence was monitored at 465 nm after excitation at 360 nm.

The microtitre plate for the EGF sandwich ELISA was coated with monoclonal mouse-anti-EGF antibody by incubating the solution (100 μL, 1 mg/L) at 4°C for 16 hours. After washing, blocking was performed with 120 μL Roti®-Block and the plate was washed again before the addition of a four-fold serial dilution of EGF (10 ng/mL to 39.1 pg/mL) in E. coli cell lysate (protein concentration 6 mg/L). After incubation for 1 hour and washing, 100 μL of a polyclonal rabbit-anti-EGF antibody (250 ng/mL) was added. Subsequently, the plate was washed and 100 μL of the diluted (1:1000) antibody-enzyme conjugate was incubated for one hour. After washing, 50 μmol/L GD4K-na (in 0.1 mol/L Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 10% DMSO) was added for signal development. End-point measurement was performed 4 hours after incubation at 37°C with λex = 360 nm and λem = 465 nm. All experiments were performed in triplicates.

Results

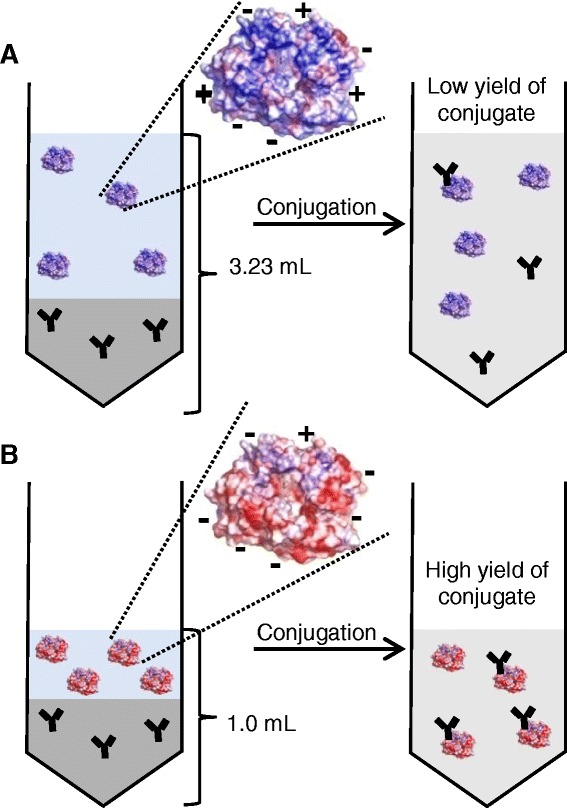

Low reaction volumes are favoured for antibody-enzyme coupling reactions to obtain high coupling yields. Hence, proteins with high solubility are favoured for coupling. We therefore investigated, if the method of protein supercharging can produce mutants that are more suitable for coupling reactions compared to their wild type enzymes using human enteropeptidase light chain (hEPl) as a model enzyme (Figure 1). The light chain of the enteropeptidase holoenzyme, a 26 kDa enzyme-fragment, contains the catalytic triade and is therefore sufficient for most enzymatic applications. In an earlier study, a rational design of a mutant with a high surface charge (N6D, G21D, G22D, C112S, N141D, K209E) resulted in a more than 100-fold increase in enzyme solubility [11], which should affect the coupling reaction positively.

Figure 1.

Schematic principle of the improvement of a protein-protein coupling reaction by enzyme surface supercharging. A high volume of wild type enzyme of the human enteropeptidase light chain is required due to its low solubility, resulting in a high total reaction volume and low yield of coupling product (A). Highly soluble surface supercharged human enteropeptidase light chain permits an increase of the enzyme concentration prior to the coupling process (B). Therefore the total reaction volume can be reduced to give a higher yield of desired product (antibody-enzyme conjugate).

As a first step for the characterization of the enzyme, the kinetic parameters of the wild type and mutated enzyme were determined (Table 1 and Additional file 1). GD4K-na was chosen as a specific substrate, because its cleavage can be detected with high sensitivity (λex = 360 nm, λem = 465 nm). The data indicate that the mutation of the enzyme resulted in a slightly decreased affinity towards the substrate, as the Michaelis constant Km was increased from 0.11 mmol/L (hEPl wt) to 0.65 mmol/L for hEPl scC112S. The insertion of aspartic acid and glutamic acid in the mutant decreased the net charge of the enzyme by a difference of 6. This could result in electrostatic repulsion between enzyme surface and the tetra-aspartyl-motif of the substrate, and could be an explanation for the slightly lower substrate affinity of the supercharged enzyme hEPl scC112S. On the other hand, the mutant enzyme possesses an increased turnover number for GD4K-na, which confirms the data obtained in earlier studies for another substrate, Z-Lys-SBzl [11]. This means that at high concentrations of substrate (>1 mmol/L), the mutated variant hEPl scC112S would result in a faster signal increase upon digestion than the wild type enzyme.

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters for the digestion of GD 4 K-na by hEPl wt and hEPl scC112S

| Enteropeptidase | K m [mmol/L] | k cat [s −1 ] | k cat / K m [(mmol/L) −1 s −1 ] | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| hEPl wt | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 81.9 ± 9.8 | 745 | This study |

| hEPl scC112S | 0.65 ± 0.09 | 169.3 ± 24.5 | 260 | This study |

| Human recombinant light chain | 0.16 ± 0.01 | 115 ± 5 | 719 | [14] |

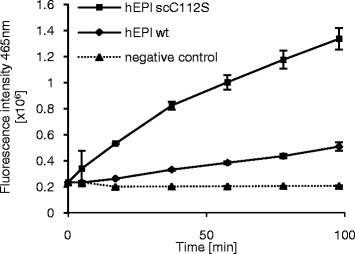

In order to analyze the coupling efficiencies of the two enzymes, both enzymes were coupled to a secondary antibody under the same coupling conditions and an ELISA experiment was carried out. Both enzyme conjugates led to signals that differed distinctly from the negative control. The signal increase for the supercharged conjugate (Ab-hEPl scC112S) was significantly higher than that for the wild type conjugate (Ab-hEPl wt) (Figure 2). While Ab-hEPl scC112S induced a signal increase of 15758 fluorescence intensity units per minute, application of the wild type conjugate resulted in a signal increase of only 2611 fluorescence intensity units per minute.

Figure 2.

Assay performances of hEPl wt and hEPl scC112S conjugate solutions. Detection of an immobilized model antigen (HPT-104 antibody [13]) was performed using 2 μg/mL total protein of untreated conjugate solution. After incubation and washing, signal was generated by addition of 50 μmol/L GD4K-na and monitored for 100 minutes. Errors = SD, n = 3.

This indicates a higher yield of supercharged enzyme-antibody conjugate. Control experiments without antigen did not show any signal differing from the negative control (Additional file 2). As the used substrate concentration for the ELISA experiment in this study is much lower (50 μmol/L) than the concentration needed to reach vmax (1 mmol/L), the faster cleavage in the ELISA obtained here can only origin from a higher amount of enzyme-antibody conjugates.

This demonstrates that the application of enzyme supercharging generated a highly soluble mutant, which is more suitable for coupling processes than its wild type form. Unfortunately, we were not able to further confirm this result via native or denaturing SDS-PAGE or Western Blot. Both methods did not show clear bands that could be used for a quantification of the coupling product (data not shown).

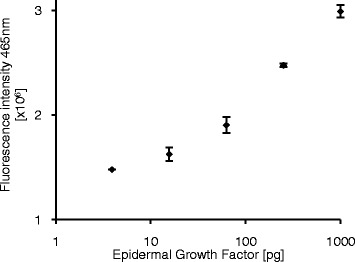

To further investigate possible bioanalytical applications of the synthesized conjugate, a coupling reaction with a 10-fold molar excess of enzyme (hEPl scC112S) was performed. The product was then utilized as a reporter molecule for the detection of epidermal growth factor (EGF). EGF is a low-molecular-weight polypeptide which affects many biochemical pathways by binding to its receptor and can be used as a cancer biomarker [15]. EGF was diluted in a complex mixture (E. coli cell lysate, 6 mg/L) and detected in a standard sandwich ELISA using two specific antibodies and the synthesized antibody conjugate (Ab-hEPl scC112S) was added for detection. The observed signals after addition of the peptide substrate GD4K-na were dependent on the amount of analyte present and permitted a detection of EGF down to 15.6 pg (Figure 3). This indicates that the hEPl scC112S mutant can be used as a reporter molecule in ELISA, while the wild type enzyme is not suitable for this application. This originates from the low solubility of the wild type which does not allow a high-yielding coupling protocol. In contrast to this, the supercharging surface modification of the enzyme results in an increased protein solubility as well as heat stability, which subsequently lead to higher yields of the desired antibody-enzyme conjugate.

Figure 3.

Use of a hEPl scC112S-antibody conjugate for the detection of EGF. Epidermal growth factor (in E. coli cell lysate as matrix) was detected using a sandwich ELISA and an in-house produced donkey-anti-rabbit/hEPl scC112S conjugate as secondary antibody. Signal was generated by addition of 50 μmol/L GD4K-na and an end-point measurement was performed after 4 hours of incubation at 37°C. The limit of detection (S/B >3xSD) was 15.63 pg EGF. Errors = SD, n = 3.

Discussion

Enzymes, like the serine protease enteropeptidase examined in this study, are widely used tools in biotechnology, industry and bioanalytics due to their catalytic function and their high specificity. However, many applications require the immobilization of these proteins on insoluble surfaces or on other biomolecules, such as other proteins. A very prominent example for enzyme-protein couplings are enzyme-antibody couplings and their subsequent use in enzyme immunoassays. As discussed earlier, various methods for enzyme-antibody couplings exist. However, the central problem of unsatisfactory protein solubility affects all of those coupling methods in a negative way.

One way to improve protein solubility is to optimize the buffer components of the coupling buffer by applying different ionic compounds or osmolytic stabilizers like sugars and polymers [16]. However, proteins are very sensitive to these conditions and slight modifications can cause protein precipitation, a loss in enzyme activity or antibody affinity. Other methods for the improvement of protein solubility exist, though they are not always suitable for the described problem. In 2009 Golovanov et al. showed, that protein solubility can be increased by a simple addition of charged amino acids. Addition of arginine and glutamic acid made several proteins accessible to NMR-studies by suppression of their aggregation tendencies [17]. Nevertheless, this method may not be suitable for protein-protein coupling reactions, since the additives possess the same reactive moieties as the proteins (e.g. amino groups). In case of protein modification with commonly used NHS-ester based linker molecules, linker reactivity would be quenched, as the reaction cannot occur specifically with the protein. This would decrease the protein modification degree and impact the overall coupling process negatively.

Also the introduction of a solubility-enhancement tag, as described in Lee et al. [18] and Zhou et al. [19] may have undesired effects, because it might alter the enzyme’s activity and selectivity. In principle, a mutation of surface amino acids of proteins can of course also lead to undesired side-effects. However, a careful design of suitable amino acids can leave the enzyme unaffected. This has been shown by us before for the mutation of surface amino acids of the human enteropeptidase light chain by site-directed mutagenesis [11].

Site-directed mutagenesis was found not only to be a tool for tailoring enzyme activity and stability, but also to improve immobilization reactions. Methods were reviewed in detail before and are for example based on the production of mutants that were capable of site-directed immobilization via specific tags [20,21]. Such methods include the incorporation of particular amino acid sequences for affinity fixation (anti-tag antibody to tagged enzyme, avidin to biotinylated protein) or the addition of a Lys-containing tags for the covalent linkage via transglutaminase cross-coupling.

Coupling procedures for the synthesis of antibody-enzyme conjugates require particularly high yields, since any unlabeled antibody fraction decreases the assay sensitivity, especially because it is difficult to purify the resulting coupling product from unmodified antibody. In addition to that, the preparation of highly pure and active enzymes is enormously laborious, which makes them an expensive material. Therefore high coupling yields are desired not only in terms of assay performance, but also with regard to material costs.

In this study, we were able to demonstrate that site-directed mutagenesis can be used to optimize coupling reactions due to an enhancement of the protein solubility. For that purpose, we tested the potential of a supercharged version of human enteropeptidase light chain with respect to its antibody-coupling yield and could show that the method of supercharging can evolve highly soluble proteins that are suitable for coupling reactions. As proven by us earlier, the site-directed surface modification of the human enteropeptidase light chain resulted in a more than 100-fold increased solubility which allowed the use of a highly concentrated enzyme solution without causing protein aggregation. This allowed the covalent linkage to an antibody with significantly higher yields compared to the wild type enzyme. Lee and coworkers demonstrated earlier that the resulting enteropeptidase-antibody conjugates are attractive components for heterogeneous immunoassays [22]. With the new coupling strategy, we showed here that the medium-scale synthesis of this kind of enzyme-antibody conjugates is possible, if a highly soluble supercharged version of the enzyme is used.

In summary, we could show that the supercharged human enteropeptidase light chain can be effectively used for the production of an antibody-enzyme conjugate. This procedure allows the use of the mutant enzyme as a reporter molecule in a sensitive ELISA system, while the wild type enzyme failed for this application. We furthermore suggest that this strategy can in principle be used for the coupling of any desired enzyme to other proteins. Examples of such enzymes which may be used for establishing novel ELISA systems may include subtilisin [23], acetylcholinesterase [24] and lipase [25].

Conclusion

This study showed that surface supercharging of proteins is a suitable method for the improvement of protein-protein cross coupling reactions. Hence, the biotechnologically improved, highly soluble mutant hEPl scC112S could be utilized as a reporter molecule for a sensitive ELISA system. In contrast, the wild type enzyme could not be coupled to a satisfactory extend and is therefore not suitable for this application.

Acknowledgment

We gratefully acknowledge the expert technical assistance from Stefanie Langanke. This work was supported by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) Innoprofile project no. 03IP604 to R.H. and the BMBF Go-Bio project no. 0315988 to T.Zu.

Abbreviations

- EGF

Epidermal growth factor

- ELISA

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- FI

Fluorescence intensity

- hEPl

Human enteropeptidase light chain

- kcat

Turnover number

- Km

Michaelis constant

- scC112S

Surface charged mutant

- SD

Standard deviation

- SDS-PAGE

Sodium dodecyl sulphate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- vmax

Maximum rate

- wt

Wild type

Additional files

Characterization of enzyme kinetics for hEPl wt and hEPl scC112S. Measurements were performed in 0.1 mol/L Tris-buffer (pH 8.0, 10% DMSO) with a GD4K-na substrate concentration range from 3.7 to 947 μmol/L. Enzymes were added to a final concentration of 10 nmol/L and fluorescence was recorded at 465 nm (λex = 360 nm). K m values were obtained from the fitted curves and were 0.11 mmol/L for hEPl wt and 0.65 mmol/L for hEPl scC112S. Errors = SD, n = 3.

Negative controls in ELISA. In the absence of antigen, no unspecific binding by both conjugate mixtures could be detected. Conjugate solutions with a total protein concentration of 2 μg/mL were used; signal development was carried out by addition of 50 μmol/L GD4K-na. Errors = SD, n = 3.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

AAP designed and performed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. TZa designed the antibody-enzyme coupling strategy. KB provided all enzymes and helped with determination of enzyme kinetics. RH helped with the design of enzyme coupling and ELISA experiments. TZu helped with design of all experiments and wrote the manuscript. All authors corrected the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Agneta A Prasse, Email: agneta.prasse@uni-leipzig.de.

Thomas Zauner, Email: T.Zauner@wolfener-analytik.de.

Karin Büttner, Email: karin.buettner@uni-leipzig.de.

Ralf Hoffmann, Email: hoffmann@chemie.uni-leipzig.de.

Thole Zuchner, Email: Thole.Zuechner@octapharma.com.

References

- 1.Leisola M, Jokela J, Pastinen O, Turunen O. Physiology and Maintenance - Vol. II. Oxford: EOLSS Publishers; 2001. Industrial Use of Enzymes. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lequin RM. Enzyme Immunoassay (EIA)/Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) Clin Chem. 2005;51:2415–2418. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.051532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Datta S, Christena LR, Rajaram YRS. Enzyme immobilization: an overview on techniques and support materials. 3 Biotech. 2013;3:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s13205-012-0071-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haugland RP. Coupling of monoclonal antibodies with enzymes. Methods Mol Biol. 1995;45:235–243. doi: 10.1385/0-89603-308-2:235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Avrameas S. Coupling of enzymes to proteins with glutaraldehyde. Immunochemistry. 1969;6:43–52. doi: 10.1016/0019-2791(69)90177-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Engvall E, Perlmann P. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) quantitative assay of immunoglobulin G. Immunochemistry. 1971;8:871–874. doi: 10.1016/0019-2791(71)90454-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tresca JP, Ricoux R, Pontet M, Engler R. Comparative activity of peroxidase-antibody conjugates with periodate and glutaraldehyde coupling according to an enzyme immunoassay. Ann Biol Clin (Paris) 1995;53:227–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lawrence MS, Phillips KJ, Liu DR. Supercharging proteins can impart unusual resilience. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:10110–10112. doi: 10.1021/ja071641y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thompson DB, Cronican JJ, Liu DR: Protein Engineering for Therapeutics, Part B. In Protein Engineering for Therapeutics, Part B. ᅟ: Elsevier; 2012.

- 10.Miklos AE, Kluwe C, Der BS, Pai S, Sircar A, Hughes RA, Berrondo M, Xu J, Codrea V, Buckley PE, Calm AM, Welsh HS, Warner CR, Zacharko MA, Carney JP, Gray JJ, Georgiou G, Kuhlman B, Ellington AD. Structure-based design of supercharged, highly thermoresistant antibodies. Chem Biol. 2012;19:449–455. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2012.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simeonov P, Berger-Hoffmann R, Hoffmann R, Sträter N, Zuchner T. Surface supercharged human enteropeptidase light chain shows improved solubility and refolding yield. Protein Eng Des Sel. 2011;24:261–268. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzq104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singer D, Lehmann J, Hanisch K, Härtig W, Hoffmann R. Neighbored phosphorylation sites as PHF-tau specific markers in Alzheimer’s disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;346:819–828. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.05.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gasparian ME, Ostapchenko VG, Schulga AA, Dolgikh DA, Kirpichnikov MP. Expression, purification, and characterization of human enteropeptidase catalytic subunit in Escherichia coli. Protein Expr Purif. 2003;31:133–139. doi: 10.1016/S1046-5928(03)00159-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yarden Y. The EGFR family and its ligands in human cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37:3–8. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(01)00230-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schein CH. Solubility as a function of protein structure and solvent components. Bio/technology (Nature Publishing Company) 1990;8:308–317. doi: 10.1038/nbt0490-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Golovanov AP, Hautbergue GM, Wilson SA, Lian L. A simple method for improving protein solubility and long-term stability. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:8933–8939. doi: 10.1021/ja049297h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee EN, Kim YM, Lee HJ, Park SW, Jung HY, Lee JM, Ahn Y, Kim J. Stabilizing peptide fusion for solving the stability and solubility problems of therapeutic proteins. Pharm Res. 2005;22:1735–1746. doi: 10.1007/s11095-005-6489-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou P, Lugovskoy AA, Wagner G. A solubility-enhancement tag (SET) for NMR studies of poorly behaving proteins. J Biomol NMR. 2001;20:11–14. doi: 10.1023/A:1011258906244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hernandez K, Fernandez-Lafuente R. Control of protein immobilization: coupling immobilization and site-directed mutagenesis to improve biocatalyst or biosensor performance. Enzym Microb Technol. 2011;48:107–122. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steen Redeker E, Ta DT, Cortens D, Billen B, Guedens W, Adriaensens P. Protein engineering for directed immobilization. Bioconjug Chem. 2013;24:1761–1777. doi: 10.1021/bc4002823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee Y, Jeong Y, Kang HJ, Chung SJ, Chung BH. Cascade enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (CELISA) Biosens Bioelectron. 2009;25:332–337. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2009.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang W, Wang J, Bhattacharyya D, Bachas LG. Improving the activity of immobilized subtilisin by site-specific attachment to surfaces. Anal Chem. 1997;69:4601–4607. doi: 10.1021/ac970390g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ivanov Y, Marinov I, Gabrovska K, Dimcheva N, Godjevargova T. Amperometric biosensor based on a site-specific immobilization of acetylcholinesterase via affinity bonds on a nanostructured polymer membrane with integrated multiwall carbon nanotubes. J Mol Catal B Enzym. 2010;63:141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.molcatb.2010.01.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kimura Y, Tanaka A, Sonomoto K, Nihira T, Fukui S. Application of immobilized lipase to hydrolysis of triacylglyceride. Eur J Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1983;17:107–112. doi: 10.1007/BF00499860. [DOI] [Google Scholar]