Lundberg et al. show that a single hematopoietic stem cell carrying a mutation in JAK2 is able to initiate cancer in mice by promoting cell division and maintaining self-renewal.

Abstract

The majority of patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) carry a somatic JAK2-V617F mutation. Because additional mutations can precede JAK2-V617F, it is questioned whether JAK2-V617F alone can initiate MPN. Several mouse models have demonstrated that JAK2-V617F can cause MPN; however, in all these models disease was polyclonal. Conversely, cancer initiates at the single cell level, but attempts to recapitulate single-cell disease initiation in mice have thus far failed. We demonstrate by limiting dilution and single-cell transplantations that MPN disease, manifesting either as erythrocytosis or thrombocytosis, can be initiated clonally from a single cell carrying JAK2-V617F. However, only a subset of mice reconstituted from single hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) displayed MPN phenotype. Expression of JAK2-V617F in HSCs promoted cell division and increased DNA damage. Higher JAK2-V617F expression correlated with a short-term HSC signature and increased myeloid bias in single-cell gene expression analyses. Lower JAK2-V617F expression in progenitor and stem cells was associated with the capacity to stably engraft in secondary recipients. Furthermore, long-term repopulating capacity was also present in a compartment with intermediate expression levels of lineage markers. Our studies demonstrate that MPN can be initiated from a single HSC and illustrate that JAK2-V617F has complex effects on HSC biology.

The JAK2-V617F mutation is present in ∼80% of patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) and is considered an important driver mutation for the disease (Baxter et al., 2005; James et al., 2005; Kralovics et al., 2005; Levine et al., 2005). This mutation provides cytokine hypersensitivity to hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and manifests in three distinct MPN phenotypes: polycythemia vera (PV), essential thrombocythemia (ET), and primary myelofibrosis (PMF). Patients with ET or PMF that are negative for JAK2-V617F frequently carry acquired mutations in calreticulin (CALR; Klampfl et al., 2013; Nangalia et al., 2013) or MPL (Pikman et al., 2006). Mutations in JAK2, CALR, and MPL are in most cases mutually exclusive. Several factors influencing the phenotypic diversity in patients with JAK2-V617F have been proposed, including the presence of a subclone homozygous for JAK2-V617F (Scott et al., 2006), expression levels of the mutant JAK2-V617F allele in mice (Tiedt et al., 2008), and the activity of the interferon and Stat1 signaling pathway (Chen et al., 2010).

In contrast to solid tumors, where several somatic mutations are present at diagnosis (Lawrence et al., 2013), the number of somatic mutations in MPN patients appears to be low (Nangalia et al., 2013; Lundberg et al., 2014). Nevertheless, it has been questioned whether JAK2-V617F as the sole genetic alteration is sufficient to initiate MPN. Genes in which recurrent somatic mutations are found in MPN include TET2 (Delhommeau et al., 2009), DNMT3A (Abdel-Wahab et al., 2011), ASXL1 (Carbuccia et al., 2009), Cbl (Sanada et al., 2009), EZH2 (Ernst et al., 2010), and LNK (Oh et al., 2010). Some of these mutations have been shown to collaborate with JAK2-V617F. Clonal analyses in MPN patients revealed that JAK2-V617F can occur before or after these additional mutational events (Kralovics et al., 2006; Beer et al., 2009; Delhommeau et al., 2009; Schaub et al., 2010). Two models are being considered to explain the molecular mechanism of how these double mutants interact. The “fertile ground” hypothesis postulates that the JAK2-V617F mutation is more effective at expanding and initiating MPN if another synergistic mutation is present in the same cell (Jones et al., 2009). One of the predictions of this fertile ground model is that disease initiation by JAK2-V617F alone is possible, but inefficient, and disease initiation can be further enhanced by other synergistic mutations. In contrast, the “hypermutability hypothesis” predicts that the first mutation increases the likelihood of acquiring a second mutation event—i.e., the mutation rate is expected to be increased (Olcaydu et al., 2009). In this model, JAK2-V617F alone initiates MPN with high efficiency and the acquisition of JAK2-V617F is the rate-limiting step.

Several JAK2-V617F mouse models have been generated using retroviral transductions, transgenic methodologies, and knock-in methodologies (Li et al., 2011). Although these models nicely recapitulate the distinct phenotypes observed in patients, MPN in these mice is of polyclonal origin, whereas in MPN patients hematopoiesis is monoclonal. Recapitulation of the MPN phenotype from a monoclonal origin has not been achieved in mouse models. To directly assess the potential of single JAK2-V617F–positive stem cells to initiate clonally derived disease, we performed competitive limiting dilution and single-cell transplantations. We show that MPN can be initiated from a single hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) carrying only JAK2-V617F. Interestingly, we found that single HSCs transplanted into primary recipients showed self-renewal and expanded in numbers, as demonstrated by their ability to stably reconstitute several secondary recipients. This capacity for long-term engraftment and self-renewal correlated with lower expression of JAK2-V617F in progenitor and stem cells, whereas higher expression levels were associated with increased cycling, limited self-renewal capacity, and a short-term HSC (ST-HSC) gene expression signature in single cell expression assays.

RESULTS

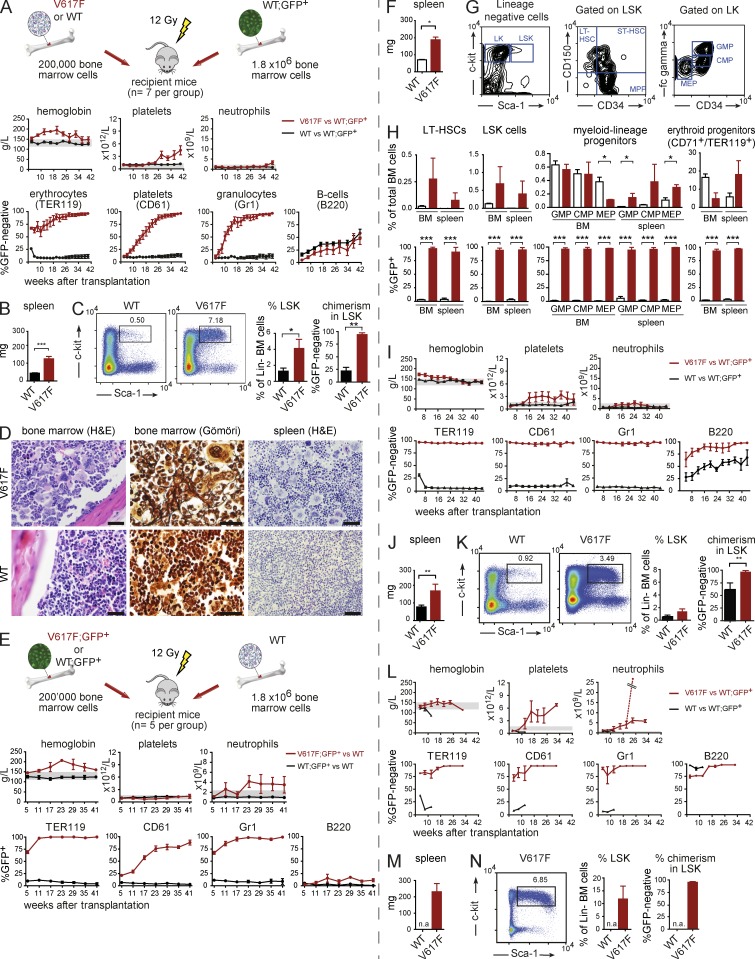

Competitive transplantation using JAK2-V617F BM cells

To study the initiation of MPN by JAK2-V617F–expressing cells, we established a competitive transplantation assay using our MxCre-loxP inducible mouse model (Tiedt et al., 2008). We used two different settings, one where JAK2-V617F–expressing cells were GFP-negative (hereafter called V617F; Fig. 1, A–D) and another where JAK2-V617F was coexpressed with GFP in the same cells (V617F;GFP+; Fig. 1, E–H). Lethally irradiated mice transplanted with a 1:10 mixture of mutant and WT BM cells in both settings rapidly developed a PV phenotype, and mutant cells outcompeted WT cells in peripheral blood (PB) myeloid lineages (Fig. 1, A and E). B cells expressing V617F showed no competitive advantage. Terminal workup at 40 and 41 wk, respectively, revealed myelofibrosis, splenomegaly, and infiltration of spleens by myeloid, erythroid, and megakaryocytic cells (Fig. 1, B–D and F–H). We observed an increase in the percentage of lineage-negative Sca-1+ c-Kit+ (LSK) cells (Fig. 1, C, G, and H). A similar trend was observed in long-term HSCs (LT-HSCs; Fig. 1 H). Myeloid progenitors were increased in the spleen (Fig. 1 H). Chimerism of V617F cells in all progenitor populations was >90% (Fig. 1 C and Fig. 1 H). The MPN phenotype from V617F donor mice was transplantable into secondary (Fig. 1, I–K) and tertiary recipients without signs of premature exhaustion of V617F-expressing cells (Fig. 1, L–N). Splenomegaly was also observed (Fig. 1, J and M) and high V617F chimerism persisted in both PB (Fig. 1, I and 1L) and BM (Fig. 1, K and N). Similar results, but less pronounced phenotypes, were observed in serial transplantations with BM from V617F;GFP+ donor mice (not depicted), suggesting that expression of GFP had a negative effect on the competitiveness of V617F-expressing cells.

Figure 1.

Competitive transplantations with JAK2-V617F (V617F) and WT BM cells. (A–D) Transplantation experiments in which GFP is expressed in the WT competitor cells, allowing indirect monitoring of the mutant allele burden. The experiment was performed twice, total n = 12 mice per group, one experiment with n = 7 is shown. (A) Schematic drawing showing the design of the experiment. The time course of PB parameters and chimerism were determined for the erythroid (TER119), platelet (CD61), granulocytic (Gr1), and B cell (B220) lineages. (B) Spleen weight at terminal workup at 40 wk (n = 7 per group). (C) Flow cytometry scattergrams showing the LSK gating. The bar graphs show the percentages of LSKs in lineage-negative cells in the BM and the chimerism within the LSK population (n = 5 per group). (D) Histopathology taken at 40 wk after transplantation (one representative mouse per group is shown). Bars, 50 µm. (E–H) Transplantation experiments in which V617F and GFP is coexpressed in the same cells, allowing direct monitoring of the mutant allele burden. The experiment was performed twice, total n = 10 of which one experiment is shown (n = 5). (E) Schematic drawing of the experimental design and results of blood counts and chimerism are shown. (F) Spleen weight at terminal workup at 41 wk (n = 5 for WT and n = 2 for V617F). (G) Gating strategy for the quantification of myeloid progenitors and HSCs. (H) Flow cytometry quantification of progenitor and stem cell populations in BM and spleen at 41 wk after transplantation (n = 5 for WT and n = 2 for V617F). (I–K) Transplantation of BM from experiment A into secondary recipients (n = 5 recipients per group, the experiment was performed once). (I) Blood counts and chimerism are shown. (J) Spleen weight of secondary recipients at 44 wk (n = 5 per group). (K) Gating and quantification of LSK cells and chimerism within the LSK population (n = 5 per group). (L–N) Transplantation of BM from experiment I into tertiary recipients (n = 5 recipients per group, the experiment was performed once). (L) Blood counts and chimerism are shown. The dashed line represents one mouse that developed a marked neutrophilia. (M) Spleen weight of tertiary recipients taken at 32 wk after transplantation (n = 3). (N) Gating and quantification of LSK cells and chimerism within the LSK population (for quantification n = 3). Statistical analysis was conducted using the Student’s t test or one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post-hoc multiple comparison test. Error bars represent ±SEM. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. n.a., not available.

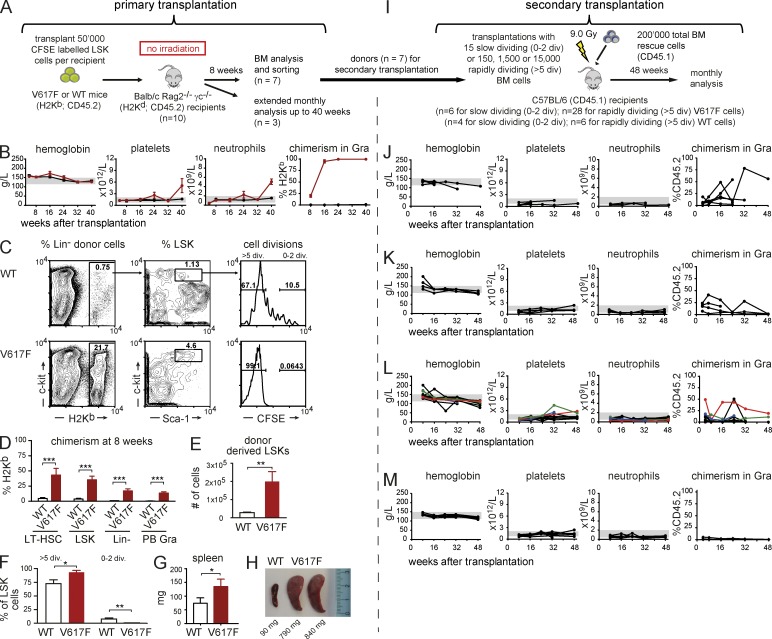

JAK2-V617F increases cycling properties of progenitor and stem cells

Because expression of JAK2-V617F increased the numbers of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (Fig. 1), we examined the cycling properties of LSKs with or without the presence of JAK2-V617F. To mimic steady-state homeostasis and avoid the effects of homeostatic expansion of HSCs in irradiated recipients and to avoid immune rejection, we performed transplantation of LSKs labeled with a fluorescent dye (CFSE) into nonconditioned BALB/c Rag2−/− γc−/− recipients (Fig. 2 A; Takizawa et al., 2011).

Figure 2.

Analysis of cell cycling of BM progenitor cells transplanted into nonconditioned immune-compromised BALB/c Rag2−/− γc−/− recipients. (A) Schematic drawing of the experimental setup (3 independent experiments, total n = 10 per group). At 8 wk, 7 mice per group were sacrificed and analyzed in detail (C–G), whereas the remaining 3 mice per group were kept for long-term analysis of blood counts, chimerism, and spleen size (B and H). (B) Time course of blood counts and chimerism in granulocytes for primary recipients. (C) Representative scattergrams showing gating strategy for chimerism and CFSE dilution analyses. (D) Quantification of chimerism, with the averages of 7 WT mice and 7 V617F mice in selected BM populations. (E) Numbers of donor-derived LSKs (n = 7 per group). (F) The percentages of LSKs with >5 cell divisions or 0–2 divisions. (G) Spleen weight at terminal workup 8 wk after transplantation (n = 7 per group). (H) Spleens at 40 wk after transplantation. (I) Schematic drawing of the experimental setup for secondary transplantations. (J) Blood counts and chimerism of secondary recipients receiving 15 slow-dividing (0–2 divisions) V617F LSKs per recipient competing with 2 × 105 WT BM rescue cells. Results of 3 independent experiments, total n = 6. (K) Same as in J, but with 15 slow-dividing WT cells. Total n = 4. (L) Blood counts and chimerism of secondary recipients receiving 150, 1,500, or 15,000 rapidly dividing V617F LSKs (>5 divisions) competing with 2 × 105 WT BM cells. Results of 3 independent experiments, total n = 28 and total n = 6 (M) for recipients of WT cells. Statistical analysis was conducted using either Student’s t test, or one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post-hoc multiple comparison test. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

Mice transplanted with V617F LSKs rapidly developed a PV phenotype, which at later time points switched to an ET phenotype with thrombocytosis and neutrophilia (Fig. 2 B). In recipients of V617F LSKs, we observed a rapid increase in chimerism reaching >90% in granulocytes. Chimerism in recipients of WT cells remained around 1% (Fig. 2 B), corresponding well with the estimated amount of empty niche space at any given time (Czechowicz et al., 2007). V617F recipients sacrificed at 8 wk after transplantation showed a dramatic increase in donor chimerism in all hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell compartments analyzed (Fig. 2, C and D). Furthermore, the number of donor-derived LSKs was markedly increased compared with mice transplanted with WT cells (Fig. 2 E). This could be explained by a significant increase in the percentage of LSKs with >5 cell divisions and a decrease in the percentage of LSKs in the 0–2 division fraction in the V617F recipients (Fig. 2, C and F). In accordance with the displayed MPN phenotype, a modest splenomegaly was observed already 8 wk after transplantation (Fig. 2 G), and a marked splenomegaly was noted at 40 wk (Fig. 2 H). These results show that expression of JAK2-V617F increases the cycling of LSKs, and that V617F LKS cells outcompete WT host BM cells even in a nonconditioned setting.

To assess whether slow- and rapidly dividing cells retained the ability to engraft and initiate MPN, slow-dividing cells (CFSE high, 0–2 divisions) and rapidly dividing cells (CFSE low, >5 divisions) were sorted and transplanted into lethally irradiated secondary recipients (Fig. 2 I). Overall, the slow-dividing LSKs from V617F donors (15 cells per mouse) engrafted more frequently than rapidly dividing LSKs (5/6 mice, 83% versus 7/28 mice, 25%, respectively, P ≤ 0.0001). Both fractions showed persistent chimerism for up to 48 wk, suggesting that they contained repopulating LT-HSCs (Fig. 2, J and L). As previously demonstrated (Takizawa et al., 2011), only the slow-dividing fraction of LSKs from WT donors gave persistent engraftment (Fig. 2, K and M). Mice transplanted with slow-dividing LSKs from V617F mice engrafted and displayed normal blood counts (Fig. 2 J). Due to low number of cells and transplantations, we cannot conclude whether the slow-dividing fraction may contain MPN initiating cells. Some mice transplanted with rapidly dividing LSKs from V617F donors showed increase in hemoglobin and later thrombocytosis compatible with MPN (Fig. 2 L). Thus, on a population basis, V617F-expressing LSKs showed increased cycling. A proportion of these rapidly dividing V617F cells, in contrast to control WT cells, were capable of retaining long-term repopulation and disease initiation capacity.

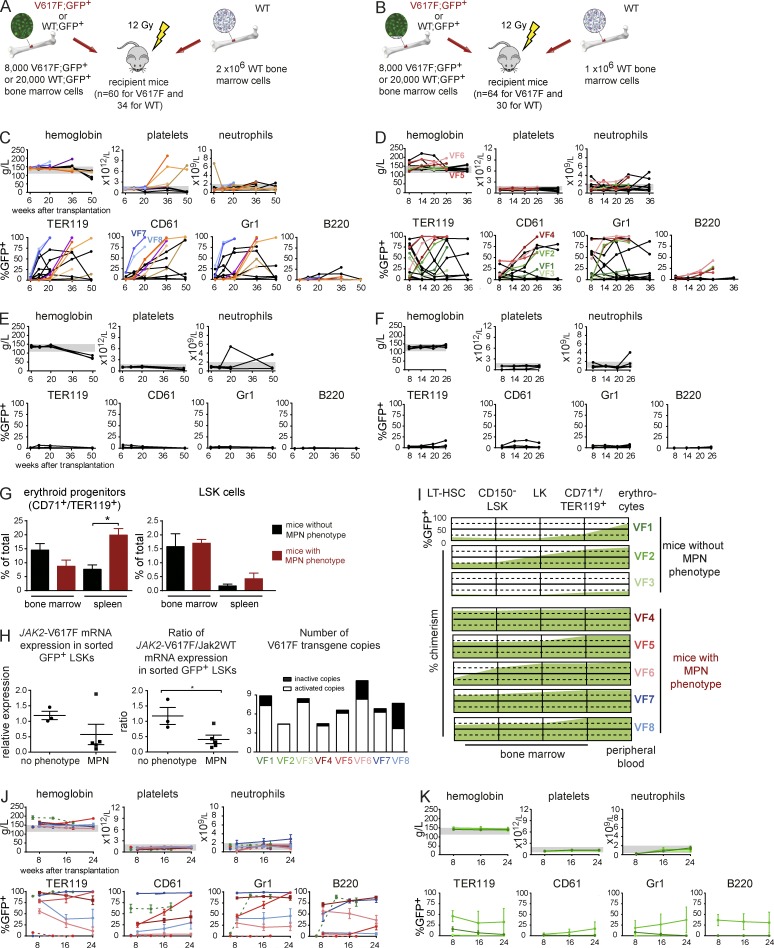

MPN disease initiation from single JAK2-V617F–expressing cells using limiting dilution transplantation

To study initiation of MPN at the single cell level, we performed several sets of transplantation experiments at increasingly limiting dilutions of V617F;GFP+ BM cells. The frequency of LT-HSCs in WT BM was reported to be 3 per 100,000 BM cells (Micklem et al., 1987; Spangrude et al., 1988; Kiel et al., 2005). However, JAK2-V617F–expressing mice showed an approximately threefold increase in phenotypically defined HSCs (Fig. 1). Therefore, we used higher dilutions of BM cells for the V617F;GFP+ transplantations to ensure that LT-HSCs become limiting (Table 1). The results of transplantations with 8,000 V617F;GFP+ BM cells competing with either 2 × 106 WT BM cells (ratio of 1:250; Fig. 3 A) or 1 × 106 (ratio of 1:125; Fig. 3 B) are presented. Similar results were obtained in transplantations with 20,000, 4,000, and 2,000 V617F;GFP+ BM cells (Table 1 and not depicted). Successful engraftment, defined as the presence of >1% GFP+ cells within Gr1+ cells in PB at 16–18 wk after transplantation, was observed in 16/60 (27%) of mice receiving 8,000 V617F;GFP+ competing with 2 × 106 cells (Fig. 3 C) and 17/64 (27%) in mice receiving 8,000 V617F;GFP+ competing with 1 × 106 cells (Fig. 3 D). Within the group of mice that engrafted, most recipients showed long-term chimerism simultaneously in erythroid, megakaryocytic, and myeloid cells, with variable B cell contribution. This is compatible with reconstitution from a LT-HSC or, in some cases, possibly by a myeloid restricted repopulating progenitor (MyRP; Yamamoto et al., 2013). The control group transplanted with 20,000 WT;GFP+ cells competing with either 2 × 106 cells or 1 × 106 cells, 3/30 mice (10%) or 5/30 mice (17%) showed engraftment and normal blood counts (Fig. 3, E and F).

Table 1.

Summary of competitive limiting dilution transplantation experiments

| Number of V617F;GFP+ or WT;GFP+ BM cells | Number of WT competitor BM cells | Ratio mutant/WT | WT;GFP+ | V617F;GFP+ | |

| Number and % of reconstituted mice | Number and % of reconstituted mice | Number and % of mice with MPN phenotype | |||

| 20,000 | 2,000,000 | 1:100 | 5/69 (7.2%)a | 15/40 (37.5%) | 4/15 (26.7%) |

| 8,000 | 2,000,000 | 1:250 | n.d. | 16/60 (26.7%) | 7/16 (43.8%) |

| 2,000 | 2,000,000 | 1:1000 | n.d. | 0/20 (0%) | 0/20 (0%) |

| Calculated frequency in total BMb | LT-HSC 1 in 265,000 | LT-HSC 1 in 35,000 | MPN initiating cell 1 in 113,000 | ||

| 20,000 | 1,000,000 | 1:50 | 5/30 (16.7%) | n.d. | n.d. |

| 8,000 | 1,000,000 | 1:125 | n.d. | 17/64 (26.6%) | 4/17 (23.5%) |

| 4,000 | 1,000,000 | 1:250 | n.d. | 3/20 (15%) | 1/3 (33.3%) |

| Calculated frequency in total BMb | LT-HSC 1 in 110,000 | LT-HSC 1 in 26,000 | MPN initiating cell 1 in 108,000 | ||

The indicated numbers of BM cells were injected into lethally irradiated recipients. Reconstitution was scored based on the presence of >1% GFP-positive cells in the PB Gr1+ cells at ∼4 mo after transplantation. n.d., not done.

Numbers of mice from two separate experiments were pooled.

The frequencies of LT-HSC and MPN initiating cells were calculated by Poisson distribution based on the frequencies of reconstituted mice, and the frequencies of mice developing an MPN phenotype, respectively.

Figure 3.

Competitive transplantations at limiting dilutions. (A and B) Schematic drawing of the 1:250 and 1:125 limiting dilution experiments (4 limiting dilution experiments were performed, n = 30–64 mice per group, see Table 1). (C and D). Blood counts and PB chimerism of the 1:250 and 1:125 transplantations. Mice showing elevated blood counts were individually colored. (E and F) Blood counts and PB chimerism in mice transplanted with 20,000 WT;GFP+ BM cells at 1:100 and 1:50 dilutions. (G) Analysis of CD71+/TER119+ erythroid progenitors and LSKs in BM and spleen are shown as percentages of all BM cells or percentage of lineage-negative cells, respectively (n = 3–5 mice per group). (H) Quantification of JAK2-V617F expression in GFP+ LSKs (n = 3–5 mice per group) shown either as expression compared with the Gusb gene (left) or as a ratio between human JAK2-V617F and mouse WT Jak2 mRNA expression (middle). The right panel shows the copy number and proportion of the activated V617F transgene in LSK cells. (I) Graph showing the engraftment of V617F;GFP+ cells at different stages of HSC, progenitor, or erythroid cell differentiation. The percentages of GFP+ cells indicate the size of the JAK2-V617F clone for nonphenotypic mice at the top (VF1-3) and mice that developed an MPN phenotype below (VF4-8). VF1-VF6 mice are from the experiment displayed in D, whereas mice VF7 and VF8 are from the experiment in C. (J) Blood counts and chimerism of secondary recipients transplanted with BM cells from donors that displayed an MPN phenotype. BM for secondary transplantation was taken from mice VF4-8 or from 3 additional mice (dotted lines) that were transplanted at 1:100 dilution in a separate experiment (see Table 1; n = 4 per group). (K) Blood counts and chimerism of secondary recipients of BM cells from donor mice that did not display MPN phenotype. BM from the 3 primary recipients VF1, VF2, and VF3 was transplanted into (n = 4 per group). Statistical analysis was conducted using Student’s t test. Error bars represent ±SEM. *, P < 0.05.

In all V617F transplantations, only a subset of mice with chimerism developed MPN (Table 1 and Fig. 3, C and D). In the 1:125 experiment, MPN developed solely as PV in 4/17 (24%) of mice, whereas the 1:250 dilution experiment showed either ET or PV in 7/16 (44%) of the mice, reflecting differences between individual donors (Fig. 3, C and D), which at the time of sacrifice displayed a PV phenotype. Interestingly, in all limiting dilution experiments, erythrocytosis and thrombocytosis were mutually exclusive in individual mice—i.e., we did not observe recipients that simultaneously displayed erythrocytosis and thrombocytosis. The frequency of long-term repopulating cells was calculated using the L-Calc software according to Poisson statistics (Table 1). The estimated probability that hematopoiesis was derived from a single V617F;GFP+ cell was calculated to be 86% for the experiment shown in Fig. 3 C and 84% for the experiments shown in Fig. 3 D. Thus, the majority of mice engrafted with GFP+ cells were reconstituted from a single stem cell.

At ∼20 wk, 3 mice with high chimerism but normal blood counts (VF1-VF3) and 5 mice with high PB chimerism and MPN phenotype (VF4-VF8) from the experiments shown in Fig. 3, C and D were sacrificed for detailed analysis (Fig. 3, G–I). Mice with MPN showed normal numbers of BM erythroid progenitors and a significant increase of splenic erythroid progenitors (Fig. 3 G). No significant change in the number of LSKs was observed, although a trend toward an increase in splenic LSK was present in the group that displayed an MPN phenotype (Fig. 3 G).

To determine whether the MPN phenotype correlated with differences in JAK2-V617F expression, we sorted GFP+ LSKs and measured expression at the RNA level. Surprisingly, in the group with MPN phenotype, a trend toward lower absolute JAK2-V617F expression and a significant decrease in the ratio of JAK2-V617F to WT mouse Jak2 mRNA were found (Fig. 3 H). We found no differences in the number of active transgene copies in LSKs from phenotypic versus nonphenotypic mice (Fig. 3 H, right). Analysis of GFP chimerism at various stages of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell and erythroid maturation revealed that mice with an MPN phenotype (VF4-VF8) displayed expansion of the V617F;GFP+ clone already in early hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells, whereas mice with a normal blood count (VF1-3) mainly showed an expansion in the later stages of erythroid differentiation (Fig. 3 I).

To test whether self-renewal of HSCs had occurred in the primary recipients that were reconstituted with limiting dilutions of BM-containing single HSCs, we selected 8 phenotypic and 3 nonphenotypic mice and transplanted their BM into 4 secondary recipients per donor (Fig. 3, J and K). Multilineage long-term engraftment with V617F cells was observed in 6/8 groups that received BM from the phenotypic donors (Fig. 3 J), and within these 6 groups all 24 individual mice showed engraftment, whereas the two remaining phenotypic donors did not engraft in any of the 8 individual recipients. 2 of the 6 groups that engrafted also developed MPN phenotype, and in both cases these groups of secondary recipients recapitulated the PV phenotype observed in the donor. When considering individual recipient mice within the groups, 5/6 donors transferred MPN to at least one of the recipients (unpublished data). In contrast, none of the 3 groups of secondary recipients of BM from nonphenotypic donors showed long-term engraftment of V617F cells (Fig. 3 K). One of the 3 donors (VF2) showed engraftment in 1/4 recipient mice, and this recipient also displayed a PV phenotype (unpublished data). Because these donor mice were reconstituted with single V617F;GFP+ HSCs, these HSCs must have undergone extensive self-renewal, as demonstrated by the capacity of their BM to long-term engraft in multiple secondary recipients. Overall, these experiments demonstrate that MPN can initiate from a single cell expressing JAK2-V617F in a competitive transplantation setting and in some but not all cases, MPN is also transplantable into secondary hosts.

To investigate whether MPN in mice reconstituted from single cells is due to the acquisition of additional somatic mutations, we performed whole exome sequencing of DNA from sorted GFP+ BM cells from three phenotypic mice (VF4, VF5, and VF6) and one nonphenotypic mouse (VF2) from the limiting dilution series shown in Fig. 3. We did not find any mutations in genes known to be linked to MPN pathogenesis. The only somatic sequence aberrations in the mice with MPN phenotype were D10Bwg1379e-R175W in mouse VF4, Clrn1-G133R, and Sp110-(intron potential splice site) in mouse VF5 and Polg-E148fs in mouse VF6. In the nonphenotypic mouse VF2 we found sequence alterations in four genes: Hjurp-P591L, Vmn1r47-A232T, Olfr747-I197indel, and Naip3-(intron potential splice site). These genes have no known function in hematopoiesis and the functional significance of these sequence alterations is questionable. We therefore conclude that the development of an MPN phenotype is not dependent on the acquisition of additional somatic mutations in any of the genes previously linked to MPN pathogenesis.

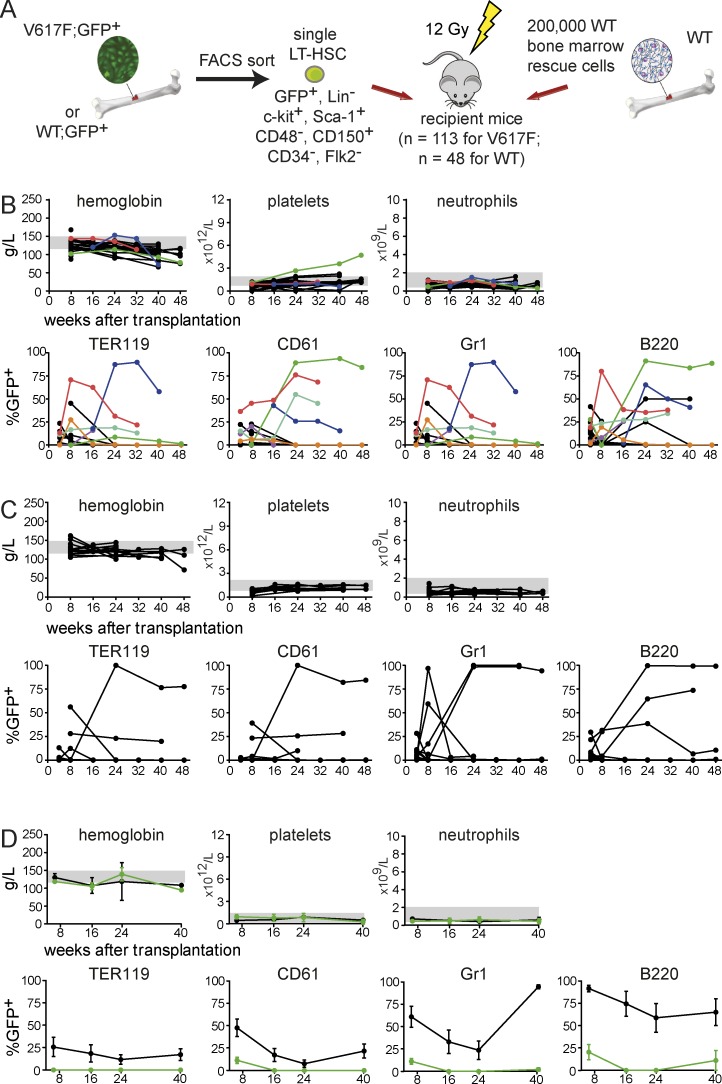

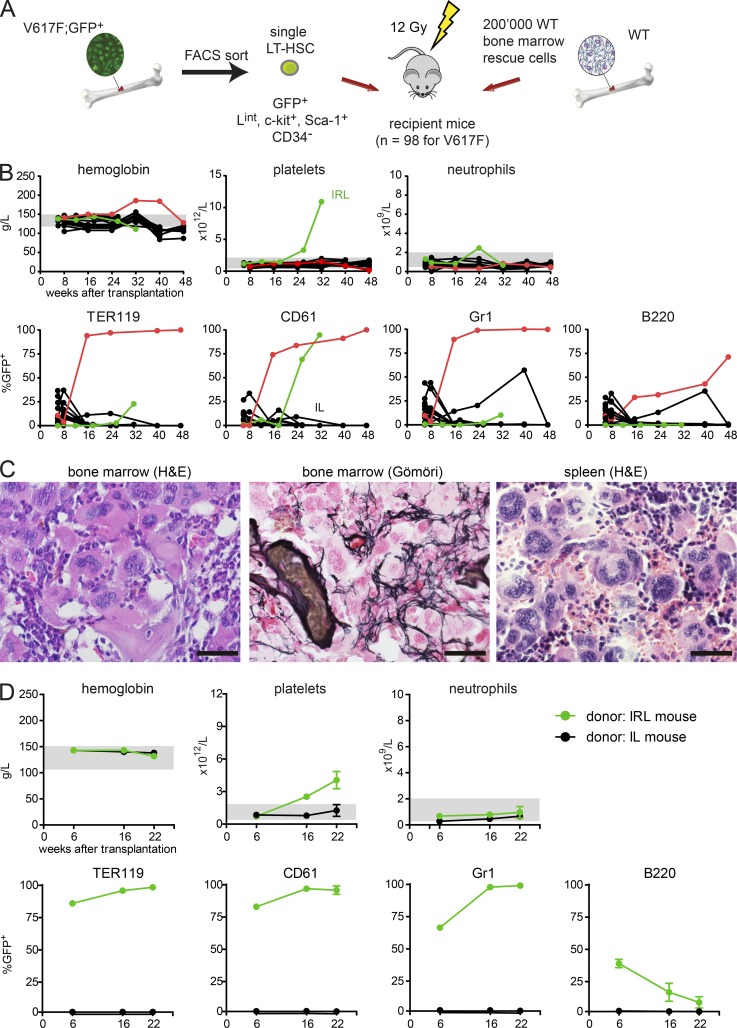

MPN initiation by a single LT-HSC–expressing JAK2-V617F

To more directly demonstrate that MPN can be initiated from a single V617F-positive cell, we FACS-sorted single V617F;GFP+ LT-HSCs (lineage negative, c-Kit+, Sca-1+, CD34−, Flk2−, CD48−, CD150+). After visual confirmation that a single cell was present per well, 2 × 105 WT BM cells were added and the mixture was injected in lethally irradiated recipients (Fig. 4 A). A total of 113 mice in 4 independent experiments were transplanted with a single V617F;GFP+ LT-HSC (Table 2). As a control, 48 mice receiving a single WT;GFP+ LT-HSC were studied. At 6 wk after transplantation, chimerism >1% GFP+ was detected in 28/113 (25%) of V617F;GFP+ recipients, and in 6/113 (5.3%) mice, high chimerism persisted beyond 24 wk (Fig. 4 B). One mouse (green line) developed an ET phenotype with sustained thrombocytosis until sacrifice at 48 wk. Two other mice (blue and red) displayed transient high chimerism in erythrocytes and/or platelets but did not develop MPN. In the control group, chimerism >1% GFP+ was observed in 17/48 (35%) recipients after 6 wk and long-term chimerism persisted in 5/48 (10.4%). All control mice displayed normal blood counts (Fig. 4 C). Transplantation of BM from the mouse with ET phenotype (green) into secondary recipients resulted in rapid loss of chimerism and no MPN phenotype (Fig. 4 D), suggesting that the MPN initiating cell did not sufficiently expand to allow transfer into secondary hosts. Alternatively, the MPN initiating cells exhausted their self-renewing capacity, or MPN was initiated from a long-term progenitor cell that lacks the capacity to repopulate secondary recipients. Thus, transplantation of a single FACS-sorted V617F-positive cell was able to sustain high chimerism and ET phenotype in one primary recipient, confirming the conclusions of the limiting dilution experiments that JAK2-V617F is sufficient to initiate MPN.

Figure 4.

Competitive transplantations with single HSCs. (A) Schematic drawing of the experimental setup. Data from four independent transplantations for the V617F;GFP+ group (total n = 113) and for the WT;GFP+ group (total n = 48) is shown. (B) Blood counts and chimerism for mice transplanted with a single V617F;GFP+ LT-HSC. Individual mice that displayed chimerism >1% are color coded. (C) Blood counts and chimerism for mice transplanted with a single WT;GFP+ LT-HSC. (D) Secondary recipients (n = 4 per group) of BM from the mouse with ET phenotype in B (green symbols) and from a WT control mouse with the highest chimerism taken from the group displayed in C.

Table 2.

Summary of transplantation of individually sorted Lineage− c-kit+ sca-1+ CD34− CD48− Flk2− CD150+ cells

| Experiment number | WT;GFP+ | V617F;GFP+ | |||

| Number and % of mice with short-term reconstitution | Number and % of mice with long-term reconstitution | Number and % of mice with short-term reconstitution | Number and % of mice with long-term reconstitution | Number and % of mice with MPN | |

| Exp. 1 | 6/15 (40.0%) | 2/15 (13.3%) | 6/17 (35.2%) | 2/17 (11.8%) | 0/2 (0%) |

| Exp. 2 | 4/16 (25.0%) | 1/16 (6.3%) | 6/27 (22.2%) | 2/27 (7.4%) | 1/2 (50%) |

| Exp. 3 | 7/11 (63.6%) | 2/11 (18.2%) | 13/38 (34.2%) | 1/38 (2.6%) | 0/1 (0%) |

| Exp. 4 | 0/6 (0%) | 0/6 (0%) | 3/31 (9.7%) | 1/31 (3.2%) | 0/1 (0%) |

| Total | 17/48 (35.4%) | 5/48 (10.4%) | 28/113 (24.8%) | 6/113 (5.3%) | 1/6 (16.7%) |

| Calculated frequencies | |||||

| ST-HSC | LT-HSC | ST-HSC | LT-HSC | MPN initiating cells | |

| 1 in 2.8 | 1 in 9.6 | 1 in 4.5 | 1 in 18.8 | 1 in 6 | |

Single-sorted GFP-positive HSCs were injected into lethally irradiated recipients together with 200,000 GFP-negative WT BM cells. Reconstitution was scored based on the presence of >1% GFP-positive cells in the PB Gr1+ cells at ∼4 mo after transplantation. n.a., not applicable.

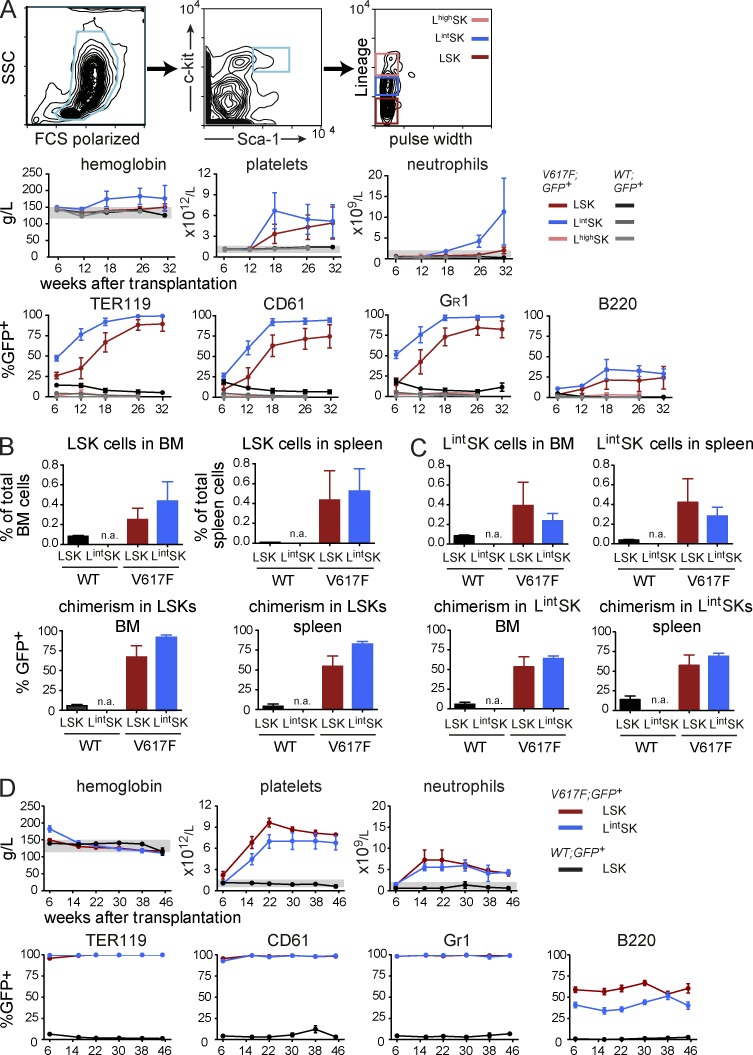

The competitive repopulating and MPN initiating capacity is increased in a c-Kit+/Sca-1+ population with an intermediate level of lineage commitment markers

Because the frequency of MPN initiation in the limiting dilution experiments was considerably higher than observed with single FACS-sorted LT-HSCs, we hypothesized that MPN initiating cells carrying JAK2-V617F may have an altered expression of the cell surface markers used for FACS sorting. Transplantation of 1,000 sorted LSKs yielded only a weak phenotype with low penetrance (unpublished data), consistent with the hypothesis that markers used for the depletion of lineage-positive cells could be responsible for the decreased efficiency of MPN initiation. Therefore, we sorted three subsets of c-Kit/Sca-1–positive cells that differ in the expression of lineage markers (Fig. 5 A) and performed competitive transplantations with these three cell populations. Lineage intermediate c-Kit+ Sca-1+ (LintSK) and lineage high c-Kit+ Sca-1+ (LhighSK) cells from WT;GFP+ donors failed to engraft, as expected (Fig. 5 A). In contrast, the recipients of V617F;GFP+ LintSK cells displayed a PV phenotype with thrombocytosis, whereas recipients of V617F;GFP+ LSKs showed a pure ET phenotype (Fig. 5 A). Interestingly, the competitive potential of LintSK cells was greater than that of LSKs, which was reflected in a faster rise and higher maximal percentage of V617F chimerism (Fig. 5 A). Terminal workup at 32 wk revealed that the transplanted LintSK cells were able to replenish the LSK population to numbers similar to those found in recipients transplanted with LSKs (Fig. 5 B, top). Furthermore, the percentage of GFP+ LSKs was comparable between recipients of LintSK and LSK BM grafts, perhaps even with a trend to higher chimerism in the LintSK recipients (Fig. 5 B, bottom). The analysis of the LintSK compartment in the transplanted mice did not yield any significant differences between the recipients of LintSK and LSK transplants (Fig. 5 C). Thus, the LintSK compartment of V617F mice contains MPN initiating cells, which in some aspects seem to be more efficient than cells from the LSK compartment. BM donors initially transplanted with either LSK or LintSK were able to sustain both high levels of chimerism and an ET phenotype in secondary transplantations (Fig. 5 D).

Figure 5.

Comparison of competitive advantage and disease initiating capacity between different subsets of FACS-sorted progenitor cells. (A) Mice were transplanted with either 1,000 LSKs (dark red color), 1,000 lineage-intermediate (Lint) SK cells (blue color), or 1,000 lineage-positive (Lhigh) SK cells (pink color) that were mixed with 1 × 106 WT BM competitor cells (GFP-negative). Blood counts and chimerism, presented as the percentage of GFP+ cells, are shown (the experiment was performed twice, total n = 10 per group). (B) Quantification of LSKs in spleen and BM, and assessment of GFP chimerism in these populations (n = 5 per group). (C) Quantification of LintSK cells in spleen and BM, and assessment of GFP chimerism in these populations (n = 5 per group). (D) Transplantation of BM into secondary recipients. BM cells (2 × 106) from primary hosts were harvested at 32 wk, pooled, and transplanted into secondary recipients (n = 5 mice per group in two independent experiments). Statistical analysis was conducted using Student’s t test. Error bars represent ±SEM.

Disease initiation with single cells sorted using a lineage intermediate SK sorting strategy

We next sought to determine whether single LT-HSCs FACS-sorted using the LintSK strategy could initiate MPN in lethally irradiated recipients. We sorted single GFP+ LintSK CD34− cells and transplanted them together with 2 × 105 WT BM competitor cells to a total of 98 mice (Fig. 6 A and Table 3). Chimerism >1% GFP+ cells at 6 wk was observed in 23/98 recipients (23%) but persisted beyond 24 wk in only 4/98 mice (4.1%; Fig. 6 B). The engraftment was similar to the long-term engraftment observed in Fig. 4 but lower than in the limiting dilution experiments. Interestingly, two mice with long-term engraftment also developed MPN: one mouse called “IRL” (green line) had ET, whereas the other mouse (red line) developed PV. The IRL mouse showed thrombocytosis and high chimerism in platelets only, compatible with reconstitution from a platelet-biased MyRP, whereas the mouse with erythrocytosis at 48 wk reached ∼100% chimerism in erythrocytes, platelets, and granulocytes and also displayed ∼75% chimerism in B-cells, compatible with reconstitution from a LT-HSC (Fig. 6 B). Terminal work-up of the IRL mouse showed massive increase of megakaryocytes in both BM and spleen, and grade 3 myelofibrosis with osteosclerosis in BM (Fig. 6 C). All 3 secondary recipients transplanted with BM cells from the IRL mouse developed ET phenotype that was still present at last follow-up 22 wk after transplantation (Fig. 6 D), demonstrating extensive self-renewal of the originally transplanted Lint LT-HSC. Although the IRL mouse displayed high chimerism only in platelets, the secondary recipients transplanted with IRL BM reached ∼100% chimerism in erythrocytes, platelets, and granulocytes. BM from a nonphenotypic mouse called “IL,” which at 32 wk showed only minimal chimerism in granulocytes (0.1%) did not engraft in secondary recipients (Fig. 6 D). Transplantations of single cells sorted using the LintSK strategy further support the conclusion that MPN can be initiated from single cells that express JAK2-V617F only and demonstrate that long-term repopulating activity in V617F mice is found in cell populations that in WT donors are incapable of promoting engraftment.

Figure 6.

Competitive transplantation of sorted single cells with intermediate expression of lineage markers (Lint). (A) Schematic drawing of the experimental setup. Lethally irradiated recipient mice were transplanted with a single V617F;GFP+ Lint LT-HSC (n = 98, in 2 independent experiments) mixed with 2 × 105 WT competitor cells. (B) Blood counts and chimerism of mice transplanted with a single V617F;GFP+ cell. (C) Histopathology at 32 wk after transplantation of mouse IRL that displayed an ET phenotype. Bars, 50 µm. (D) Secondary recipients (n = 3) of BM from the mouse IRL with ET in Fig. 6 B (green symbols) and a control littermate with low chimerism.

Table 3.

Transplantation of individually sorted Lineageint c-kit+ sca-1+ CD34− cells

| WT;GFP+ | V617F;GFP+ | ||||

| Exp. 1 | n.a. | n.a. | 18/40 (45%) | 2/40 (5.0%) | 1/2 (50%) |

| Exp. 2 | n.a. | n.a. | 5/58 (8.6%) | 2/58 (3.4%) | 1/2 (50%) |

| Total | n.a. | n.a. | 23/98 (23.5%) | 4/98 (4.1%) | 2/4 (50%) |

| Calculated frequencies | |||||

| ST-HSC | LT-HSC | ST-HSC | LT-HSC | MPN initiating cells | |

| n.a. | n.a. | 1 in 4.3 | 1 in 24.4 | 1 in 2 | |

Single sorted GFP-positive HSCs were injected into lethally irradiated recipients together with 200,000 GFP-negative WT BM cells. Reconstitution was scored based on the presence of >1% GFP-positive cells in the PB Gr1+ cells at ∼4 mo after transplantation. n.a., not applicable.

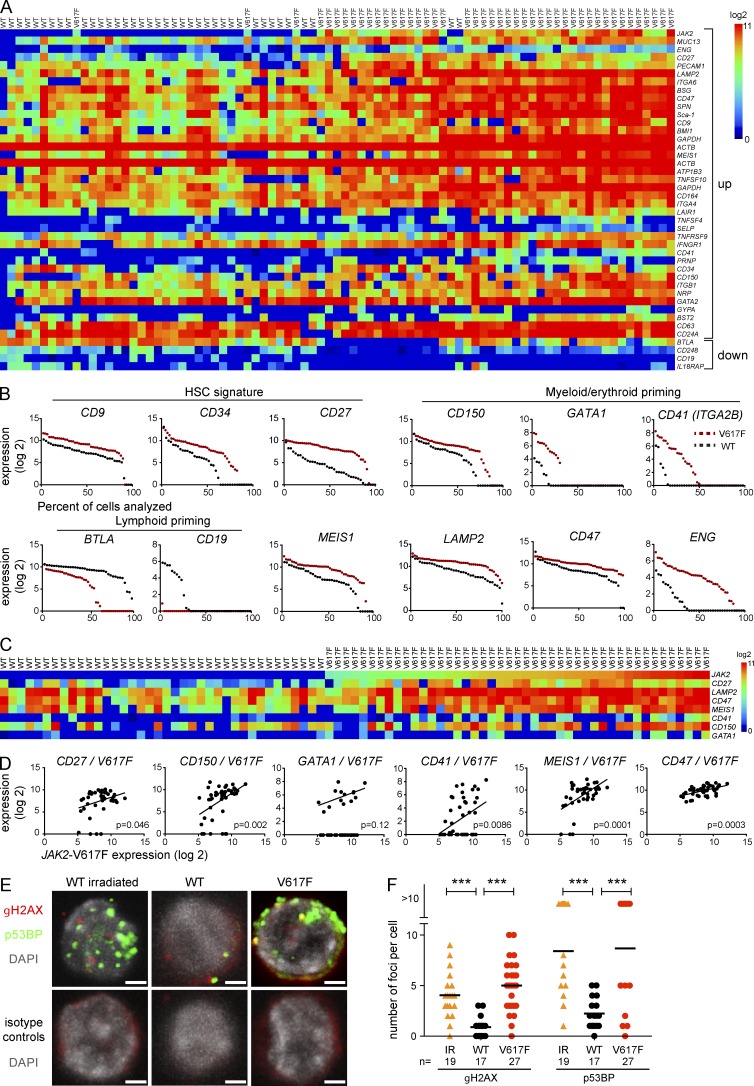

Characterization of JAK2-V617F–expressing HSCs by single cell expression profiling

Because JAK2-V617F altered the cycling behavior of HSCs and extended the MPN initiating capacity to cells that express intermediate levels of lineage markers, we suspected that V617F also altered the gene expression in HSCs. We therefore performed gene expression analysis in sorted single LT-HSCs (Fig. 7 A). LT-HSCs (n = 45) from two JAK2-V617F mice or two WT mice (n = 38) were FACS-sorted using LSK/CD34− markers and deposited as single cells into 96-well plates. The expression levels of a selected panel of 284 genes (Table S1) were determined as previously described (Guo et al., 2013).

Figure 7.

Characterization of JAK2-V617F LT-HSCs by single-cell expression profiling. (A) Heat map of the hierarchical clustering showing expression levels of all genes differentially expressed between FACS-sorted V617F and WT single cells with a cutoff of P ≤ 0.01. Top rows show genes up-regulated in V617F cells and bottom rows genes that are down-regulated. Data from two independent experiments are shown (total n = 38 for WT cells and n = 45 for V617F cells). (B) Expression levels and percentages of expressing cells of selected genes implicated in self-renewal and myeloid/lymphoid priming. Dots represent single cells and they are arranged according to decreasing expression. (C) Genes whose expression levels correlated with expression levels of JAK2-V617F. (D) Correlations between up-regulated genes and V617F. (E) DNA damage in LT-HSCs from V617F mice and controls. Immunofluorescence images of nuclei showing γH2AX and p53BP foci in LT-HSCs from irradiated WT mice, WT controls, and V617F mice are shown. LT-HSC from WT and JAK2-V617F mice were co-stained with antibodies against p53BP and γH2AX (top) or isotype matched antibodies (bottom). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. As a positive control, LSKs were isolated from mice 1 h after 2Gy irradiation (IR). Images of cells were acquired on confocal microscopy and numbers of foci within nuclei were counted. Bars, 2 µm. (F) Quantification of the numbers of γH2AX and p53BP foci. Data from one experiment is shown, n = 19 (irradiated control), n = 17 (WT control), and n = 27 (V617F). Statistical analysis was conducted using Wilcoxon, Mann-Whitney Test, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post-hoc multiple comparison, or Student’s t test. ***, P ≤ 0.001.

LT-HSCs expressing JAK2-V617F mainly clustered together (Fig. 7 A). Markers that correlate with the loss of LT-HSC properties (e.g., CD34 and CD27) were expressed at higher levels in JAK2-V617F–expressing LT-HSCs (Fig. 7 A), and these cells also showed significantly increased expression of genes associated with myeloid/erythroid differentiation (CD150 and CD41 in Fig. 7 A; and GATA1 in Table S1) and lower expression of genes associated with lymphopoiesis (BTLA and CD19 in Fig. 7 A). The differences in expression levels, and in some cases also in the percentages of expressing or nonexpressing cells, are visualized in Fig. 7 B. Overall, compared with the WT controls, V617F-expressing LT-HSCs displayed a signature of myeloid-biased ST-HSCs. Also among genes significantly up-regulated in JAK2-V617F–expressing LT-HSCs were CD47 and LAMP2, two potential therapeutic targets (Majeti et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2012; Sukhai et al., 2013), MEIS1, a gene implicated in AML pathogenesis (Li et al., 1999; Wong et al., 2007), and ENG, a component of the TGF-β receptor.

Several of the significantly up-regulated genes also showed correlation with the levels of JAK2-V617F in individual cells (Fig. 7, C and D). CD150 and CD41, genes reported to be expressed on myeloid-biased HSCs (Morita et al., 2010; Gekas and Graf, 2013), as well as CD27, a marker associated with decreased self-renewal of LT-HSCs (Wiesmann et al., 2000), correlated well with JAK2-V617F expression (Fig. 7 D). Thus, increased expression of JAK2-V617F at the single cell level was associated with a more myeloid-biased short-term LT-HSC signature.

We also performed single cell expression analysis of LT-HSCs FACS-sorted using the LintSK strategy (Fig. S1). As expected, this population of cells was more heterogeneous, and the number of genes that were significantly different between V617F and WT (cutoff of P ≤ 0.01) was smaller than in the LT-HSC series. Nevertheless, the V617F-expressing Lint LT-HSCs clustered largely together, whereas the WT Lint LT-HSCs were split into several subgroups (Fig. S1 A). Some of these genes also correlated with the JAK2-V617F expression levels (Fig. S1, C and D).

JAK2-V617F–expressing cells show signs of increased DNA damage

Because HSCs that express V617F on a population basis divide faster than WT controls (Fig. 2) and many of the genes up-regulated in LT-HSCs (Fig. 7, A–D) are linked to loss of quiescence, we hypothesized that these changes could result in increased DNA damage. We assessed DNA damage by determining the number of γH2AX and p53BP foci in nuclei of sorted LT-HSCs using immunofluorescence confocal microscopy (Fig. 7 E). Cells irradiated with 2 Gy are known to show an increase in γH2AX and p53BP foci and served as positive controls. Our results show that V617F-expressing LT-HSCs show a similar increase in γH2AX and p53BP foci to cells irradiated with γ-rays, indicating that a substantial increase in DNA damage can be found due to V617F expression in these cells.

DISCUSSION

JAK2-V617F is found in >80% of patients with MPN and is considered a phenotypic driver mutation responsible for the manifestation of the MPN phenotype. However, in some MPN patients, mutations in other genes have been shown to precede the acquisition of JAK2-V617F (Beer et al., 2009; Delhommeau et al., 2009; Schaub et al., 2009, 2010; Lundberg et al., 2014). These reports raised the question of whether JAK2-V617F is capable of initiating MPN alone or whether additional mutations are necessary for disease initiation. Furthermore, the JAK2-V617F mutation was detected in blood cells from healthy controls/non-MPN cases, suggesting that JAK2-V617F may not be sufficient (Sidon et al., 2006; Xu et al., 2007; Nielsen et al., 2011). These data support the hypothesis that acquisition of JAK2-V617F does not invariably result in MPN. In this study, we show that initiation of MPN can be achieved from a single HSC expressing JAK2-V617F, and that other genetic events are most likely not required for induction of a full MPN phenotype. This is the first report of initiation of a hematologic malignancy from a single cell in a mouse model. Because only a minority of mice that stably reconstituted from single cells also developed MPN, our data also support the notion that additional mutations could increase the efficiency of MPN disease initiation.

Expression of JAK2-V617F in LSKs increased their cycling dramatically, and after 8 wk there were very few cells left that retained CFSE (Fig. 2). Increased cycling was also observed in two other reports using JAK2-V617F mouse knock-in models (Hasan et al., 2013; Mullally et al., 2013) but was reported to be reduced in a mouse knock-in model expressing human JAK2-V617F (Li et al., 2010). As a potential consequence of increased cycling and the nuclear functions of Jak2, we also found increased numbers of γH2AX and p53BP foci in the nuclei of V617F-expressing LT-HSCs indicating increased DNA damage (Fig. 7, E and F; Plo et al., 2008). Despite increased cycling, the rapidly dividing fraction of V617F-expressing cells retained the capacity to repopulate secondary hosts and in some of the recipients initiated MPN (Fig. 2 L). Expression of JAK2-V617F also conferred long-term repopulating activity to LintSK cells. Up-regulation of cell-surface lineage antigens could be related to increased cycling, as has been reported in fetal liver HSCs (Morrison et al., 1995) and in adult BM after 5-FU treatment (Randall and Weissman, 1997).

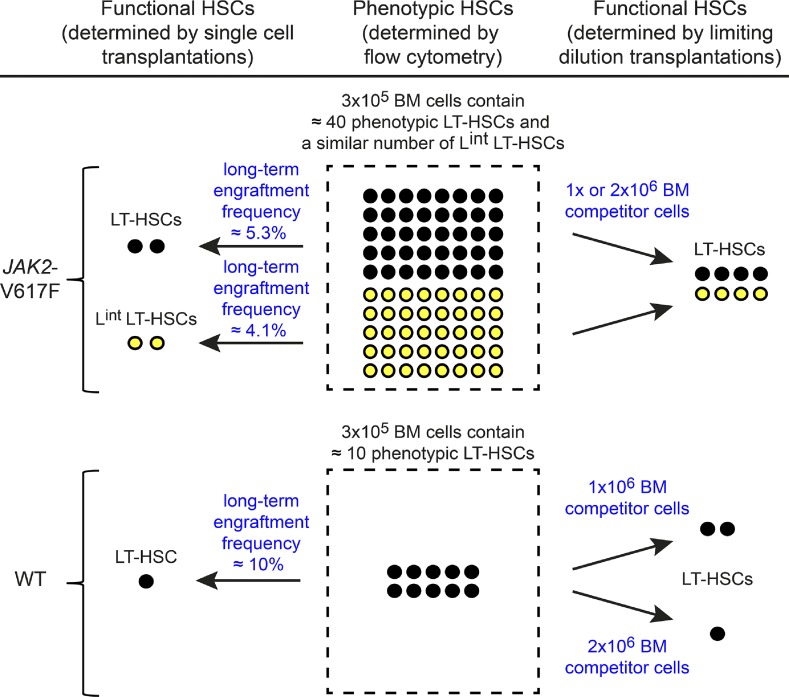

The numeric alterations of the HSC compartment observed in V617F mice are summarized in Fig. 8. The number of phenotypic LT-HSCs was increased approximately fourfold in V617F mice compared with WT controls. Other V617F mouse models showed either normal or increased HSC numbers (Akada et al., 2010; Marty et al., 2010; Mullally et al., 2010, 2012, 2013; Hasan et al., 2013). In contrast, the mouse model described by Li et al. (2010) displayed a decrease in LSK cell numbers. In the single cell transplantations of V617F-expressing LT-HSCs, we observed a 50% decreased likelihood of short- and long-term reconstitution compared with WT LT-HSCs (Tables 2 and 3), possibly reflecting reduced engraftment. However, in our V617F mice this reduced efficiency was more than compensated by the fourfold increase in phenotypic HSC numbers. Thus, overall we found an approximately twofold increase of functional HSCs (Fig. 8, left). Because the LintSK compartment in V617F mice also contained long-term repopulating cells, the total increase in functional HSCs compared with WT mice is approximately fourfold. The conclusion that the total number of functional HSCs is increased in V617F mice is further supported by the limiting dilution experiments (Fig. 8, right). Estimated by Poisson distribution, the LT-HSC pool in V617F mice was expanded ∼4.2- or 7.6-fold compared with BM from WT;GFP+ controls, depending on whether 1 × 106 or 2 × 106 WT competitor BM cells were used, respectively (Table 1).

Figure 8.

Summary of the observed numeric alterations in the HSC compartment of JAK2-V617F mice. The middle panel shows the numbers of phenotypic LT-HSCs (black circles) per 3 × 105 BM cells (dashed box), as determined by flow cytometric analysis. V617F mice also have LT-HSCs with intermediate expression levels of lineage markers (Lint) that are capable of long-term engraftment (yellow circles). Lint LT-HSCs with long-term engraftment potential do not exist in WT mice. The left panel shows the numbers of functional HSCs per 3 × 105 BM cells calculated from transplantations of sorted single cells using the frequencies of long-term engraftment (derived from Tables 2 and 3). The right panel shows the number of functional LT-HSCs per 3 × 105 BM cells derived from limiting dilution transplantations and calculated by Poisson distribution (see Table 1).

The V617F-expressing cells in all our competitive transplantations displayed a dramatic advantage over the WT competitor cells. The percentage of chimerism reached by sorted single WT;GFP+ cells or limiting dilutions of WT;GFP+ BM cells was strongly suppressed when the number of WT competitor cells increased from 0.2 × 106 BM cells (Fig. 4) to 1 × 106 BM cells (Fig. 3 F) to 2 × 106 BM cells (Fig. 3 E). In contrast, V617F;GFP+ cells, once they engrafted, frequently showed high chimerism (>90%) irrespective of the number of WT competitor BM cells. A similarly drastic advantage for the V617F-expressing LSK cells compared with the WT LSKs was observed in the nonconditioned transplantation experiments (Fig. 2, C and D). Other MPN mouse models also showed a competitive advantage of V617F cells in primary recipient mice (Hasan et al., 2013; Mullally et al., 2013), but this advantage was not observed in secondary transplantations. In a human Jak2-V617F knock-in model, whole BM displayed a reduced competitiveness in primary transplants (Li et al., 2010) and mice had decreased numbers of phenotypic HSCs that also displayed reduced self-renewal (Kent et al., 2013).

Once long-term engraftment of V617F;GFP+ cells was obtained, the likelihood of developing an MPN phenotype was ∼30%, with no difference between the limiting dilution and sorted single cell transplantation experiments. In the limiting dilution experiments, the presence of MPN phenotype correlated with lower expression ratio of V617F;WT Jak2 mRNA and with high chimerism that extended into the progenitor and stem cell compartment (Fig. 3). Differences in the expression levels of JAK2-V617F in individual cells could play a major role in determining behavior and fate of HSCs. Hierarchical clustering grouped the V617F-expressing cells together and revealed that genes associated with a ST-HSC signature were up-regulated in these cells (Fig. 7, A and B). When aligned according to increasing levels of JAK2-V617F expression, the high V617F-expressing cells again displayed a ST-HSC signature (Fig. 7, C and D). In particular, CD27, a marker enriched for in ST-HSCs (Wiesmann et al., 2000), correlated well with JAK2-V617F expression (Fig. 7). This is consistent with the model that HSCs with high expression of JAK2-V617F are more likely to lose their self-renewal capacity and exhaust, whereas low JAK2-V617F–expressing HSCs are more likely to retain their long-term repopulation capacity. Accordingly, secondary recipients of BM from the nonphenotypic donors with a high expression of JAK2-V617F showed signs of exhaustion and decline of chimerism (Fig. 3 K). A similar correlation was described in experiments with human CD34+ cells, where high Stat5a activity favored differentiation and induction of erythropoiesis, whereas lower Stat5a activity had moderate effects on differentiation but increased self-renewal of progenitors and HSCs (Wierenga et al., 2008). Interestingly, a recent study demonstrated that mutant Nras was able to drive both self-renewal and proliferation in distinct HSC populations. Activated Stat5 was observed in cells expressing mutant Nras and deletion of one Stat5 allele decreased both proliferation and self-renewal driven by mutant Nras (Li et al., 2013). Thus, the correlation of elevated V617F expression with increased cycling and decreased self-renewal is comparable with the effects of activated Stat5 signaling on HSCs in other systems. Similarly, hyperactive tyrosine kinases other than JAK2—for example, BCR-ABL and FLT3-ITD—have been shown to compromise HSC self-renewal (Schemionek et al., 2010; Chu et al., 2012).

The pattern of lineage contributions in most mice reconstituted from single-cell or limiting dilution transplantations is compatible with being reconstituted from a LT-HSC. Nevertheless, in a few of the single-cell reconstituted mice we observed patterns that resemble the characteristics of myeloid-restricted repopulating progenitors with self-renewal capacity, MyRPs, that have been recently shown to directly derive from HSCs (Yamamoto et al., 2013). These mice show chimerism in erythrocytes, platelets, and granulocytes but not in lymphocytes (Fig. 3, C and D). The HSC compartment is now recognized to have a high degree of heterogeneity with distinct populations of HSCs that are primed toward producing a certain lineage (Sieburg et al., 2006; Dykstra et al., 2007; Morita et al., 2010; Benz et al., 2012; Gekas and Graf, 2013), and our data suggests that this could also be the case for malignant HSCs. However, it remains to be determined whether mice with high chimerism in erythrocytes, platelets, and granulocytes in our experiment are reconstituted from a true LT-HSC or a cell with MyRP characteristics. Mice reconstituted by single MPN initiating cells always displayed either erythrocytosis or thrombocytosis that were mutually exclusive and PV phenotype appeared consistently earlier than ET (Figs. 3 and 6). In mice with ET and an almost exclusively high chimerism in platelets, it is conceivable that disease was derived either from a later progenitor or the previously reported LT-HSC with strong platelet bias (Sanjuan-Pla et al., 2013). The switch from PV to ET that occurs after 16–20 wk (Fig. 1) could in part also be due to an early dominance of the HSCs with erythroid bias, which subsequently exhaust or are outcompeted by HSCs with megakaryocytic bias.

Our data support the notion that JAK2-V617F in addition to being able to drive erythropoiesis and thrombopoiesis also critically regulates the balance between self-renewal and differentiation of HSCs. When expressed at adequate levels, JAK2-V617F can initiate disease from a single cell as the sole genetic alteration. The ability to generate clones of mutant cells and follow their behaviors (e.g., lineage preference or cell cycle status) in the mouse offers new opportunities to determine the cellular mechanisms of tumor initiation and progression and more accurately model human cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Transgenic mice.

Mice with Cre-recombinase inducible human JAK2-V617F transgene (FF1) were generated directly in the C57BL/6 background in our laboratory (Tiedt et al., 2008). The FF1 mice were crossed with MxCre transgenic mice to allow inducible activation of the FF1 transgene. The MxCre mice had been backcrossed into the C57BL/6 background for 12 generations. Cre expression in MxCre;FF1 transgenic mice was induced by a single intraperitoneal injection of 300 µg polyinosine-polycytosine (pIpC). BM cells of UBC-GFP transgenic mice that that were made directly in the C57BL/6 background and constitutively express enhanced GFP in all hematopoietic lineages were used for competitive transplantation assays (Schaefer et al., 2001). In some competitive transplantation assays, BM cells from MxCre;FF1;UBC-GFP triple transgenic mice were used. The recipient C57BL/6 mice used for competitive transplantations were purchased from Harlan Laboratories. All mice in this study were kept under specific pathogen-free conditions with free access to food and water in accordance to Swiss Federal Regulations.

Cell isolation.

Total BM cells were harvested from long bones and, when needed, red blood cells were lysed with ACK lysis buffer (150 mM NH4Cl, 10 mM KHCO3, and 0.1 mM EDTA). The debris was removed with 70-µm cell strainers (BD).

Competitive BM transplantations.

In all competitive transplantations, either mutated or WT cells express GFP, thus allowing tracking of chimerism in all hematopoietic lineages. Transplantations were performed with BM or sorted cells of mice 6–8 wk after pIpC injections at an age of 12–14 wk. For the first set of competitive transplantation experiments, total BM cells isolated from MxCre;FF1 JAK2-V617F donor mice were mixed in a ratio of 1:10 (mutant/WT) with UBC-GFP BM cells as competitors and transplanted into lethally irradiated C57BL/6 female recipients. In consecutive rounds of competitive transplantations, the MxCRE;FF1 strain was crossed with UBC-GFP so that JAK2-V617F–expressing cells were also GFP positive (hereafter called V617F;GFP+). Total BM cells isolated from V617F;GFP+ donor mice were mixed in different ratios (1:10, 1:50, 1:100, 1:125, 1:250, and 1:1,000, mutant/WT) with C57BL/6 BM cells and transplanted into lethally irradiated female recipients. The total number of transplanted cells was either 2 × 106 (experiments shown in Fig. 3 A and Table 1, top) or 1 × 106 (experiments shown in Fig. 3 B or Table 1, bottom). Control mice were injected with WT C57BL/6 and UBC-GFP BM cells using the same ratio. Blood samples were taken every 4–6 wk to determine the percentage of GFP-positive versus -negative cells in the PB and for complete blood analysis. Secondary and tertiary transplantations were performed with BM from primary or secondary recipients harvested at 40 and 41 wk, respectively. BM from all five recipients alive at the day of termination was pooled and 2 × 106 cells were injected into each secondary or tertiary recipient (groups of five mice per genotype). In the final phase of the experiment, the recipients were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation and the tissue/blood samples were taken for further analysis.

PB analysis.

Blood was collected from the tail vein or by cardiac puncture and complete blood counts (CBC) were determined on an Advia120 Hematology Analyzer using Multispecies Version 5.9.0-MS software (Bayer).

Flow cytometry.

The whole blood was stained with PE or allophycocyanin (APC) monoclonal antibodies against TER119 (PE), CD61 (PE or APC), B220 (APC), Gr1 (PE), and Mac1 (APC; BD and BioLegend) and lysed with FACS Lysing Solution (BD). Single-cell suspensions from BM and spleen were stained with PE-conjugated monoclonal antibodies against Gr1, Mac1, TER119, and biotin-conjugated anti–mouse CD71 antibody (BD and BioLegend), followed by APC-conjugated streptavidin (BioLegend). After lysis, the cells were analyzed on a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACSCalibur; BD). For the stem/progenitor cell analysis, antibodies against c-Kit (PE-Cy7), Sca-1 (APC-Cy7), CD150 (PE-Cy5), CD34 (Alexa Fluor 660), and Fc-gamma receptor (PE) were used. In the experiments where lineage staining or depletion was performed, the mouse hematopoietic cell depletion kit (R&D Systems) with antibodies against CD5, CD11b, CD45R (B220), Ly-6G (Gr1), and TER-119 was used.

Whole exome sequencing of genomic DNA.

Exome enrichment was performed using the SureSelect Mouse All Exon kit and samples were prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Sequencing was performed with the HiSeq 2000 using paired-end 100 reads yielding ∼70 million reads/sample. All samples were sequenced in duplicates (two lanes in total). The mean exon coverage per duplicate was ∼70-fold. The presence/absence of variants was assessed using the CLC Genomics Workbench in comparison to the C57BL/6 genome dataset. Germline variations were excluded on the basis of the following criteria: Because all four mice (three with MPN phenotype and one without MPN) were reconstituted with BM from the same donor, we expect that germline variants that were present in the BM donor will be present in all four of the recipients. Conversely, a somatic mutation, which occurred during BM engraftment and clonal expansion, will be present in only one of the four mice. Using these criteria we found a total of 414 sequence differences with the C57BL/6 genome dataset, and of these 407 were germline because they were present in all four recipient mice. The remaining seven sequence aberrations were found in only one of the four recipients and these are reported in the results section as being acquired somatic SNVs.

Single cell transplantation.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting was performed using an InFlux or FACSAria III Cell Sorter (BD). BM was depleted from lineage-committed cells using a mouse hematopoietic cell depletion kit (R&D Systems) with antibodies against CD5, CD11b, CD45R (B220), Ly-6G (Gr1), and TER-119 and stained for remaining lineage+ cells (streptavidin–Pacific blue), c-Kit (PE-Cy7), Sca-1 (APC-Cy7), CD150 (PE-Cy5), CD34 (Alexa Fluor 660), Flk2 (PE), and CD48 (Pacific blue). The cells were sorted into 96-well plates and the presence of a single cell was confirmed by ocular inspection. In the wells where the presence of a single cell was confirmed, 2 × 105 competitor cells were added and the cells were i.v. transplanted into lethally irradiated female C57BL/6 mice. In all single cell transplantation experiments, BM cells from V617F;GFP+ were used.

LSK cycling experiments.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting was performed using a FACSAria III. Sorted LSK cells were labeled for 7 min at 37°C with 2 µM CFSE (Life Technologies) in Dulbecco’s PBS (D-PBS; Invitrogen) supplemented with 1% FCS. The same volume of ice-cold PBS with 10% FCS was then added to stop the reaction. After washing with Mg2+/Ca2+-free PBS, 105 CFSE-labeled LSK cells (H2Kb+) were i.v. transplanted into nonirradiated BALB/c Rag2−/− γc−/− (H2Kd+) mice. Nondivided cell fraction was determined based on CFSE intensity of nondividing control CD4+CD62L+ cells that had been transplanted into nonirradiated congenic mice in parallel, as shown previously (Takizawa et. al., 2011).

Real-time PCR analysis.

The number of transgene copies in the individual BM and PB populations were determined by real-time PCR (7500 Fast Real-Time PCR system; Applied Biosystems) using the Power SYBR Green PCR Master mix with the following primers: 5′-GTGGCAGCAACAGAGCCTATC-3′ and 5′-GGAGCTTCAGCACCTCGAGAT-3′ for human JAK2 and 5′-TGGCAGCAGCAGAACCTACA-3′ and 5′-GGAGCTTCAGCCCCACG-3′ for mouse Jak2. To calculate the number of transgene copies in the native orientation, the primers 5′-GCTGCAGCACAGAGATTAAATAGC-3′ and 5′-TGGATCGACATAACTTCGTATAATGTATG-3′ were used. Real-time PCR efficiency of these primers was very similar to the efficiency of primers that were used to determine the total human JAK2. Based on this, the expression in the BM and blood samples was performed by real-time PCR (7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System, Applied Biosystems) using the primers 5′-TCACCAACATTACAGAGGCCTACTC-3′ and 5′-GCCAAGGCTTTCATTAAATATCAAA-3′ for human JAK2, and 5′-CCACGGCCCAATATCAATG-3′ and 5′-CCCGCCTTCTTTAGTTTGCTA-3′ for mouse Jak2. The primers for the mouse Gusb were 5′-ATAAGACGCATCAGAAGCCG-3′ and 5′-ACTCCTCACTGAACATGCGA-3′. The calculations of human and mouse JAK2 ratio were based on the standard curves prepared from linearized pMSCV-IRES GFP plasmids containing either human or mouse JAK2.

High throughput single-cell qPCR.

Single-cell qPCR was performed as previously described (Guo et al., 2013). In brief, individual primer sets were pooled to a final concentration of 0.1 µM for each primer. Individual cells were sorted directly into 96-well PCR plates loaded with 10 µl RT-PCR master mix (2.5 µl CellsDirect reaction mix [Invitrogen], 0.5 µl primer pool; 0.1 µl RT/Taq enzyme [Invitrogen]; 1.9 µl nuclease-free water) in each well. Sorted plates were immediately frozen on dry ice. Cell lysis and sequence-specific reverse transcription were performed at 50°C for 60 min. The reverse transcription was inactivated by heating to 95°C for 3 min. Subsequently, in the same tube, cDNA went through sequence-specific amplification by denaturing at 95°C for 15 s, and annealing and amplification at 60°C for 15 min for 20 cycles. These preamplified products were diluted fivefold before analysis with Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems), EvaGreen Binding Dye (Biotium), and individual qPCR primers in 96.96 Dynamic Arrays on a BioMark System (Fluidigm). Ct values were calculated from the system’s software (BioMark Real-time PCR Analysis; Fluidigm).

DNA damage measurement by quantification of γH2AX and p53BP foci.

LT-HSCs (Lint/Lin− c-Kit+ Sca-1+ CD41− CD48− CD150+) from nonirradiated WT or JAK2-V617F, or LKS from the mice 1 h after 2Gy x-ray irradiation were sorted onto a slide precoated with 0.01% poly-L-lysine (Sigma-Aldrich) and incubated for >40 min at room temperature until cells were settled down on the slide. The cells were fixed with 4% PFA for 10 min at room temperature and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 20 min at room temperature, followed by blocking with 10% goat serum in 0.1% Triton X-100/PBS for 60 min at room temperature. The resultant cells were stained with antibodies against phospho-H2AX (clone JBW301; Millipore) and p53BP (Novus Biotechnologies) overnight at 4°C, and subsequently stained with goat anti–mouse antibody conjugated with Alexa Fluor 647 and goat anti–rabbit antibody Alexa Fluor 488 (Life Technologies) for 60 min at room temperature, followed by nuclei counterstaining with 10 µg/ml DAPI (Life Technologies) for 5 min at room temperature. The images were acquired on confocal microscopy (SP5; Leica) and the number of foci on nuclei was counted manually using the image software Imaris (Bitplane).

Online supplemental material.

Table S1 contains the complete gene list of differentially expressed transcripts found in the single cell expression analyses. Fig. S1 shows the single cell expression data obtained with LT-HSCs FACS-sorted using the LintSK strategy. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jem.org/cgi/content/full/jem.20131371/DC1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Claudia Lengerke and Takafumi Shimizu for helpful comments on the manuscript.

S.H. Orkin is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. This work was supported by grants 310000-120724/1 and 32003BB_135712/1 from the Swiss National Science Foundation and the Swiss Cancer League (KLS-2950-02-2012) to R.C. Skoda and by Swiss National Science Foundation grant 310030_146528/1 to M.G. Manz.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used:

- APC

- allophycocyanin

- ET

- essential thrombocythemia

- HSC

- hematopoietic stem cell

- LintSK

- lineage intermediate c-Kit+ Sca-1+

- LSK

- lineage-negative c-Kit+ Sca-1+

- LT-HSC

- long-term HSC

- MPN

- myeloproliferative neoplasm

- MyRP

- myeloid restricted repopulating progenitor

- PB

- peripheral blood

- PV

- polycythemia vera

- ST-HSC

- short-term HSC

References

- Abdel-Wahab, O., Pardanani A., Rampal R., Lasho T.L., Levine R.L., and Tefferi A.. 2011. DNMT3A mutational analysis in primary myelofibrosis, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia and advanced phases of myeloproliferative neoplasms. Leukemia. 25:1219–1220. 10.1038/leu.2011.82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akada, H., Yan D., Zou H., Fiering S., Hutchison R.E., and Mohi M.G.. 2010. Conditional expression of heterozygous or homozygous Jak2V617F from its endogenous promoter induces a polycythemia vera-like disease. Blood. 115:3589–3597. 10.1182/blood-2009-04-215848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter, E.J., Scott L.M., Campbell P.J., East C., Fourouclas N., Swanton S., Vassiliou G.S., Bench A.J., Boyd E.M., Curtin N., et al. Cancer Genome Project. 2005. Acquired mutation of the tyrosine kinase JAK2 in human myeloproliferative disorders. Lancet. 365:1054–1061. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71142-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beer, P.A., Jones A.V., Bench A.J., Goday-Fernandez A., Boyd E.M., Vaghela K.J., Erber W.N., Odeh B., Wright C., McMullin M.F., et al. 2009. Clonal diversity in the myeloproliferative neoplasms: independent origins of genetically distinct clones. Br. J. Haematol. 144:904–908. 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07560.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benz, C., Copley M.R., Kent D.G., Wohrer S., Cortes A., Aghaeepour N., Ma E., Mader H., Rowe K., Day C., et al. 2012. Hematopoietic stem cell subtypes expand differentially during development and display distinct lymphopoietic programs. Cell Stem Cell. 10:273–283. 10.1016/j.stem.2012.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbuccia, N., Murati A., Trouplin V., Brecqueville M., Adélaïde J., Rey J., Vainchenker W., Bernard O.A., Chaffanet M., Vey N., et al. 2009. Mutations of ASXL1 gene in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Leukemia. 23:2183–2186. 10.1038/leu.2009.141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, E., Beer P.A., Godfrey A.L., Ortmann C.A., Li J., Costa-Pereira A.P., Ingle C.E., Dermitzakis E.T., Campbell P.J., and Green A.R.. 2010. Distinct clinical phenotypes associated with JAK2V617F reflect differential STAT1 signaling. Cancer Cell. 18:524–535. 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.10.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu, S.H., Heiser D., Li L., Kaplan I., Collector M., Huso D., Sharkis S.J., Civin C., and Small D.. 2012. FLT3-ITD knockin impairs hematopoietic stem cell quiescence/homeostasis, leading to myeloproliferative neoplasm. Cell Stem Cell. 11:346–358. 10.1016/j.stem.2012.05.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czechowicz, A., Kraft D., Weissman I.L., and Bhattacharya D.. 2007. Efficient transplantation via antibody-based clearance of hematopoietic stem cell niches. Science. 318:1296–1299. 10.1126/science.1149726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delhommeau, F., Dupont S., Della Valle V., James C., Trannoy S., Massé A., Kosmider O., Le Couedic J.P., Robert F., Alberdi A., et al. 2009. Mutation in TET2 in myeloid cancers. N. Engl. J. Med. 360:2289–2301. 10.1056/NEJMoa0810069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dykstra, B., Kent D., Bowie M., McCaffrey L., Hamilton M., Lyons K., Lee S.J., Brinkman R., and Eaves C.. 2007. Long-term propagation of distinct hematopoietic differentiation programs in vivo. Cell Stem Cell. 1:218–229. 10.1016/j.stem.2007.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst, T., Chase A.J., Score J., Hidalgo-Curtis C.E., Bryant C., Jones A.V., Waghorn K., Zoi K., Ross F.M., Reiter A., et al. 2010. Inactivating mutations of the histone methyltransferase gene EZH2 in myeloid disorders. Nat. Genet. 42:722–726. 10.1038/ng.621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gekas, C., and Graf T.. 2013. CD41 expression marks myeloid-biased adult hematopoietic stem cells and increases with age. Blood. 121:4463–4472. 10.1182/blood-2012-09-457929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo, G., Luc S., Marco E., Lin T.W., Peng C., Kerenyi M.A., Beyaz S., Kim W., Xu J., Das P.P., et al. 2013. Mapping cellular hierarchy by single-cell analysis of the cell surface repertoire. Cell Stem Cell. 13:492–505. 10.1016/j.stem.2013.07.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, S., Lacout C., Marty C., Cuingnet M., Solary E., Vainchenker W., and Villeval J.L.. 2013. JAK2V617F expression in mice amplifies early hematopoietic cells and gives them a competitive advantage that is hampered by IFNα. Blood. 122:1464–1477. 10.1182/blood-2013-04-498956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James, C., Ugo V., Le Couédic J.P., Staerk J., Delhommeau F., Lacout C., Garçon L., Raslova H., Berger R., Bennaceur-Griscelli A., et al. 2005. A unique clonal JAK2 mutation leading to constitutive signalling causes polycythaemia vera. Nature. 434:1144–1148. 10.1038/nature03546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, A.V., Chase A., Silver R.T., Oscier D., Zoi K., Wang Y.L., Cario H., Pahl H.L., Collins A., Reiter A., et al. 2009. JAK2 haplotype is a major risk factor for the development of myeloproliferative neoplasms. Nat. Genet. 41:446–449. 10.1038/ng.334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent, D.G., Li J., Tanna H., Fink J., Kirschner K., Pask D.C., Silber Y., Hamilton T.L., Sneade R., Simons B.D., and Green A.R.. 2013. Self-renewal of single mouse hematopoietic stem cells is reduced by JAK2V617F without compromising progenitor cell expansion. PLoS Biol. 11:e1001576. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiel, M.J., Yilmaz O.H., Iwashita T., Yilmaz O.H., Terhorst C., and Morrison S.J.. 2005. SLAM family receptors distinguish hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and reveal endothelial niches for stem cells. Cell. 121:1109–1121. 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D., Wang J., Willingham S.B., Martin R., Wernig G., and Weissman I.L.. 2012. Anti-CD47 antibodies promote phagocytosis and inhibit the growth of human myeloma cells. Leukemia. 26:2538–2545. 10.1038/leu.2012.141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klampfl, T., Gisslinger H., Harutyunyan A.S., Nivarthi H., Rumi E., Milosevic J.D., Them N.C., Berg T., Gisslinger B., Pietra D., et al. 2013. Somatic mutations of calreticulin in myeloproliferative neoplasms. N. Engl. J. Med. 369:2379–2390. 10.1056/NEJMoa1311347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kralovics, R., Passamonti F., Buser A.S., Teo S.S., Tiedt R., Passweg J.R., Tichelli A., Cazzola M., and Skoda R.C.. 2005. A gain-of-function mutation of JAK2 in myeloproliferative disorders. N. Engl. J. Med. 352:1779–1790. 10.1056/NEJMoa051113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kralovics, R., Teo S.S., Li S., Theocharides A., Buser A.S., Tichelli A., and Skoda R.C.. 2006. Acquisition of the V617F mutation of JAK2 is a late genetic event in a subset of patients with myeloproliferative disorders. Blood. 108:1377–1380. 10.1182/blood-2005-11-009605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, M.S., Stojanov P., Polak P., Kryukov G.V., Cibulskis K., Sivachenko A., Carter S.L., Stewart C., Mermel C.H., Roberts S.A., et al. 2013. Mutational heterogeneity in cancer and the search for new cancer-associated genes. Nature. 499:214–218. 10.1038/nature12213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine, R.L., Wadleigh M., Cools J., Ebert B.L., Wernig G., Huntly B.J., Boggon T.J., Wlodarska I., Clark J.J., Moore S., et al. 2005. Activating mutation in the tyrosine kinase JAK2 in polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia, and myeloid metaplasia with myelofibrosis. Cancer Cell. 7:387–397. 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.03.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, J., Shen H., Himmel K.L., Dupuy A.J., Largaespada D.A., Nakamura T., Shaughnessy J.D. Jr, Jenkins N.A., and Copeland N.G.. 1999. Leukaemia disease genes: large-scale cloning and pathway predictions. Nat. Genet. 23:348–353. 10.1038/15531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, J., Spensberger D., Ahn J.S., Anand S., Beer P.A., Ghevaert C., Chen E., Forrai A., Scott L.M., Ferreira R., et al. 2010. JAK2 V617F impairs hematopoietic stem cell function in a conditional knock-in mouse model of JAK2 V617F-positive essential thrombocythemia. Blood. 116:1528–1538. 10.1182/blood-2009-12-259747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, J., Kent D.G., Chen E., and Green A.R.. 2011. Mouse models of myeloproliferative neoplasms: JAK of all grades. Dis. Model. Mech. 4:311–317. 10.1242/dmm.006817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q., Bohin N., Wen T., Ng V., Magee J., Chen S.C., Shannon K., and Morrison S.J.. 2013. Oncogenic Nras has bimodal effects on stem cells that sustainably increase competitiveness. Nature. 504:143–147. 10.1038/nature12830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg, P., Karow A., Nienhold R., Looser R., Hao-Shen H., Nissen I., Girsberger S., Lehmann T., Passweg J., Stern M., et al. 2014. Clonal evolution and clinical correlates of somatic mutations in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood. 123:2220–2228. 10.1182/blood-2013-11-537167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majeti, R., Chao M.P., Alizadeh A.A., Pang W.W., Jaiswal S., Gibbs K.D. Jr, van Rooijen N., and Weissman I.L.. 2009. CD47 is an adverse prognostic factor and therapeutic antibody target on human acute myeloid leukemia stem cells. Cell. 138:286–299. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marty, C., Lacout C., Martin A., Hasan S., Jacquot S., Birling M.C., Vainchenker W., and Villeval J.L.. 2010. Myeloproliferative neoplasm induced by constitutive expression of JAK2V617F in knock-in mice. Blood. 116:783–787. 10.1182/blood-2009-12-257063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micklem, H.S., Lennon J.E., Ansell J.D., and Gray R.A.. 1987. Numbers and dispersion of repopulating hematopoietic cell clones in radiation chimeras as functions of injected cell dose. Exp. Hematol. 15:251–257 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita, Y., Ema H., and Nakauchi H.. 2010. Heterogeneity and hierarchy within the most primitive hematopoietic stem cell compartment. J. Exp. Med. 207:1173–1182. 10.1084/jem.20091318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, S.J., Hemmati H.D., Wandycz A.M., and Weissman I.L.. 1995. The purification and characterization of fetal liver hematopoietic stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 92:10302–10306. 10.1073/pnas.92.22.10302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullally, A., Lane S.W., Ball B., Megerdichian C., Okabe R., Al-Shahrour F., Paktinat M., Haydu J.E., Housman E., Lord A.M., et al. 2010. Physiological Jak2V617F expression causes a lethal myeloproliferative neoplasm with differential effects on hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Cancer Cell. 17:584–596. 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.05.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullally, A., Poveromo L., Schneider R.K., Al-Shahrour F., Lane S.W., and Ebert B.L.. 2012. Distinct roles for long-term hematopoietic stem cells and erythroid precursor cells in a murine model of Jak2V617F-mediated polycythemia vera. Blood. 120:166–172. 10.1182/blood-2012-01-402396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullally, A., Bruedigam C., Poveromo L., Heidel F.H., Purdon A., Vu T., Austin R., Heckl D., Breyfogle L.J., Kuhn C.P., et al. 2013. Depletion of Jak2V617F myeloproliferative neoplasm-propagating stem cells by interferon-α in a murine model of polycythemia vera. Blood. 121:3692–3702. 10.1182/blood-2012-05-432989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nangalia, J., Massie C.E., Baxter E.J., Nice F.L., Gundem G., Wedge D.C., Avezov E., Li J., Kollmann K., Kent D.G., et al. 2013. Somatic CALR mutations in myeloproliferative neoplasms with nonmutated JAK2. N. Engl. J. Med. 369:2391–2405. 10.1056/NEJMoa1312542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, C., Birgens H.S., Nordestgaard B.G., Kjaer L., and Bojesen S.E.. 2011. The JAK2 V617F somatic mutation, mortality and cancer risk in the general population. Haematologica. 96:450–453. 10.3324/haematol.2010.033191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh, S.T., Simonds E.F., Jones C., Hale M.B., Goltsev Y., Gibbs K.D. Jr, Merker J.D., Zehnder J.L., Nolan G.P., and Gotlib J.. 2010. Novel mutations in the inhibitory adaptor protein LNK drive JAK-STAT signaling in patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood. 116:988–992. 10.1182/blood-2010-02-270108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olcaydu, D., Harutyunyan A., Jäger R., Berg T., Gisslinger B., Pabinger I., Gisslinger H., and Kralovics R.. 2009. A common JAK2 haplotype confers susceptibility to myeloproliferative neoplasms. Nat. Genet. 41:450–454. 10.1038/ng.341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pikman, Y., Lee B.H., Mercher T., McDowell E., Ebert B.L., Gozo M., Cuker A., Wernig G., Moore S., Galinsky I., et al. 2006. MPLW515L is a novel somatic activating mutation in myelofibrosis with myeloid metaplasia. PLoS Med. 3:e270. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plo, I., Nakatake M., Malivert L., de Villartay J.P., Giraudier S., Villeval J.L., Wiesmuller L., and Vainchenker W.. 2008. JAK2 stimulates homologous recombination and genetic instability: potential implication in the heterogeneity of myeloproliferative disorders. Blood. 112:1402–1412. 10.1182/blood-2008-01-134114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall, T.D., and Weissman I.L.. 1997. Phenotypic and functional changes induced at the clonal level in hematopoietic stem cells after 5-fluorouracil treatment. Blood. 89:3596–3606 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]