Abstract

Proneural basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) proteins initiate neurogenesis in both vertebrates and invertebrates. The Drosophila Achaete (Ac) and Scute (Sc) proteins are among the first identified members of the large bHLH proneural protein family. phyllopod (phyl), encoding an ubiquitin ligase adaptor, is required for ac- and sc-dependent external sensory (ES) organ development. Expression of phyl is directly activated by Ac and Sc. Forced expression of phyl rescues ES organ formation in ac and sc double mutants. phyl and senseless, encoding a Zn-finger transcriptional factor, depend on each other in ES organ development. Our results provide the first example that bHLH proneural proteins promote neurogenesis through regulation of protein degradation.

Keywords: E3 ligase, senseless, basic helix-loop-helix, neurogenesis

The basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) proneural proteins promote neurogenesis from flies to mammals (for reviews, see refs. 1 and 2). In Drosophila, the proneural proteins Achaete (Ac), Scute (Sc), Atonal (Ato), and Amos are bHLH transcriptional factors that are essential for the generation of neural precursors in the central and peripheral nervous systems (3-5). In mammals, the bHLH proteins Mash1, homolog of Ac and Sc, and Neurogenins, homologs of Ato and Amos, are essential for the initiation of neurogenesis (6, 7). Proneural genes are expressed in small clusters of cells, called proneural clusters, and they endow cells the potential to adopt neural fate, such as sensory organ precursors (SOPs) in the Drosophila peripheral nervous system. However, lateral inhibition mediated by the ligand Delta and the receptor Notch restricts the expression of proneural genes to only one or a few cells that differentiate into neural precursors, and prevents neighboring cells of the selected neural precursors from adapting the same fate (8).

The Drosophila proneural genes ac and sc function redundantly in the formation of external sensory (ES) organs; in ac and sc double mutants, formation of ES organs is disrupted, and misexpression of either ac or sc induces ectopic ES organs (9-12). The Ac and Sc proteins share 70% identity in their bHLH domains (3), and form heterodimers with the ubiquitously expressed bHLH protein Daughterless (Da) to activate transcription of downstream target genes (13, 14). One target gene of Ac and Sc, asense (ase), also encodes a bHLH protein that is specifically expressed in SOPs and involved in SOP differentiation (15-17). Likewise, NeuroD, the mammalian homolog of Ase, also plays an important role in neuronal differentiation (18). In addition to the bHLH genes, a number of Ac and Sc target genes have been identified. For example, senseless (sens) is expressed in SOPs and is required to maintain high levels of proneural proteins in SOPs (19, 20). Genes involved in lateral inhibition to select SOPs are also targets for Ac and Sc, including scabrous (sca), Delta (Dl), and those in the Enhancer of split [E(spl)] and Bearded (Brd) complexes (21, 22). However, target genes essential for SOP differentiation and the mechanism(s) by which they promote the differentiation process are relatively unknown.

Phyl is an adaptor protein that functions to link the ubiquitin ligase Seven in absentia (Sina) to the transcriptional repressor Tramtrack (Ttk) (23), leading to Ttk degradation. Phyl is required in the specification of SOPs and a subset of photoreceptors (24, 25). In this report, we show that phyl promotes SOP differentiation; in phyl hypomorphic mutants, expression of genes in SOP differentiation and lateral inhibition are affected. phyl is directly activated by Ac and Sc through their cognate binding sites in the phyl promoter region. phyl misexpression restores efficiently ES organ formation in the ac and sc double mutant. Taken together, our results suggest that Phyl executes the program of SOP differentiation directed by Ac and Sc proneural proteins. Lastly, we examine the relationship between phyl and sens in SOP differentiation.

Materials and Methods

Flies. phyl mutants (phyl1, phyl2, phyl2245, and phyl4) were described (26). sc10-1 is a compound mutation that inactivates both ac and sc function (3). scB57 is a small deletion in which ac, sc, l'sc, and ase genes are removed, and scB57 clones were generated by x-ray-induced recombination. sensE2 FRT80B/TM6B and FRT42d pwn phyl2 Bc/CyO were used to generate sens and phyl mutant clones, respectively. For misexpression experiment, Eq-GAL4 (26, 27), dpp-GAL4 (28), UAS-myc-phyl (26), UAS-sc (29), and UAS-sens (19) were used.

Plasmid Construction. The 4.1-, 3.4-, and 2.2-kb phyl promoter fragments were cloned into pStinger (30) to generate phyl4.1-GFP, phyl3.4-GFP, and phyl2.2-GFP, respectively, and 4.1- and 3.4-kb fragments were fused to phyl ORF to generate phyl4.1-ORF and phyl3.4-ORF rescue constructs.

For site-specific mutagenesis, the Ac/Da and Sc/Da binding consensus CANNTG was mutated to CCNNTT, and the Sens binding consensus AAATCA was mutated to AAATGA (19).

Results

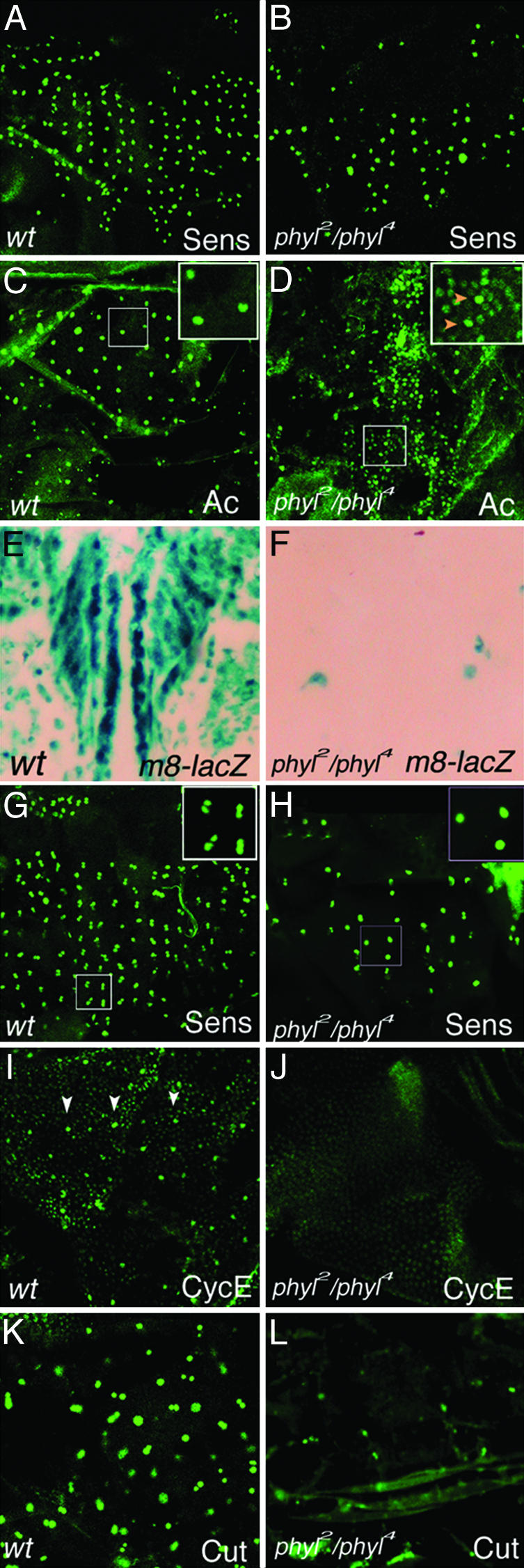

phyl in SOP Development. In phyl2-null mutant clones, adult ES organs are absent, and this defect is caused by a failure in SOP specification (26). In phyl2/phyl4 hypomorphic mutants, most ES organs are also absent, and expression of two SOP markers, ase-lacZ and the A101 enhancer trap line, are strongly compromised (26). However, Sens is expressed in single, selected SOPs at 12-14 h after puparium formation (APF) (Fig. 1B), suggesting a defect in SOP differentiation, but not in SOP selection in phyl hypomorphic mutants.

Fig. 1.

phyl is required for SOP differentiation. (A) Wild-type notum at 12-14 h APF stained with anti-Sens antibodies. (B)In phyl2/phyl4 mutants at 12-14 h APF, Sens is still expressed in single SOPs. (C) Ac protein is specifically expressed in single SOPs at 12-14 APF in wild type. (D) Ac protein is also expressed at a lower level in cells surrounding SOPs in phyl2/phyl4 mutants at 12-14 h APF. Red arrowheads in Inset indicate the Sens-positive cells. (E) In wild type, E(spl)m8-LacZ is expressed strongly in cells of proneural clusters at 12-16 h APF. (F) In phyl2/phyl4 mutants, E(spl)m8-LacZ expression is abolished at 12-16 h APF. (G) In wild type at 16-18 h APF, Sens is expressed in two cells in each ES organ. (H) In phyl2/phyl4 mutants even at 24-26 h APF, many Sens-positive cells are still at one-cell stage. (I)At12-16 h APF, CycE is expressed at a elevated level in Sens-positive SOPs (arrowheads, Sens expression is not shown). (J) In phyl2/phyl4 mutants at 12-16 h APF, only the uniform, low-level CycE expression is present in all cells. (K) Cut is expressed in single SOPs or SOP progenies (IIa and IIb cells) in wild-type ES organs at 14-16 h APF. (L) Only residual Cut expression is present in phyl2/phyl4 mutants at 14-16 h APF.

We then examined Ac expression, which is initially in proneural clusters and restricted in SOPs at 12-14 APF in wild type (Fig. 1C). However, in phyl2/phyl4 mutants, Ac expression was not only detected in SOPs (indicated by red arrowheads in Fig. 1D Inset), but also weakly in SOP-neighboring cells. Ac expression in SOP-neighboring cells is later diminished at 16-18 APF (data not shown). This result suggests that lateral inhibition is partially affected. To test this, E(spl)m8-lacZ was used as a reporter to monitor Notch signaling (31, 32). Although E(spl)m8-lacZ is strongly expressed in a proneural pattern in wild type (Fig. 1E), the expression is abolished in phyl2/phyl4 mutants (Fig. 1F), suggesting that activation of the Notch pathway in the SOP-neighboring cells is compromised in phyl mutants.

In wild-type ES organ development, Sens staining appears in two SOP-daughter cells at 16-18 h APF (Fig. 1G) and in four daughter cells at 24-28 h APF (data not shown). In phyl2/phyl4 mutants, Sens is still maintained mostly in single cells even at 24-28 h APF (Fig. 1H). In wild-type animals, SOPs express elevated levels of the cell-cycle regulator Cyclin E (CycE) (Fig. 1I) (33). In phyl2/phyl4 mutants, SOPs fail to express a higher level of CycE (Fig. 1F), suggesting a failure in cell cycle progression. The SOPs and SOP daughter cells of ES organs express cut, a selector gene in the determination of ES organ identity (Fig. 1K and refs. 34-36). In phyl2/phyl4 mutants when SOP differentiation has been arrested, Cut expression is absent (Fig. 1L). Taken together, these data indicate that Phyl is required for gene expression in SOP differentiation and lateral inhibition, for SOP cell cycle progression and for ES organ identity.

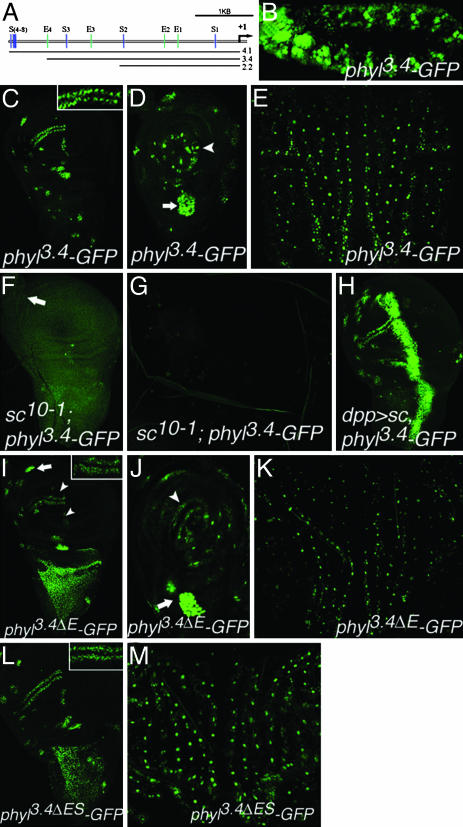

phyl Is a Direct Target Gene of Ac and Sc. Ac and Sc are bHLH transcriptional activators, and Ac/Da and Sc/Da heterodimers bind specifically to the E boxes CAG(G/C)TG with high affinity and CACGTG with low affinity (21). Within the 4.1-kb phyl promoter region, there are four such E boxes (E1-E3, CAGCTG; E4, CACGTG; Fig. 2A). We constructed three phyl reporter genes by fusing 4.1-, 3.4-, and 2.2-kb promoter regions of phyl to GFP, and all three reporters show similar expression patterns with difference in the GFP signal intensities (the 4.1-kb promoter being the strongest and 2.2-kb being the weakest). For example, the 3.4-kb region is sufficient to drive GFP expression in embryonic SOPs (Fig. 2B), SOPs of the late third-instar larval wing and leg disks (Fig. 2 C and D), and SOPs in early pupal nota (Fig. 2E). These phyl-GFP reporter genes are also expressed in the proneural clusters at earlier stages in both wing disks and pupal nota (Fig. 2C and data not shown).

Fig. 2.

phyl transcription depends on ac and sc activity. (A) Schematic diagram of the 4.1-kb upstream region of phyl.E1-E4 represent the Ac/Da and Sc/Da binding sites (E1-E3: CAGCTG, E4: CACGTG). S1-S8 represent the Sensbinding sites (S box, AAATGA). (B) phyl3.4-GFP is expressed in SOPs of the embryonic peripheral nervous system at stage 11. (C) phyl3.4-GFP is expressed in SOPs and proneural clusters in late third-instar larval wing disks. (C Inset) Magnified picture of wing margin SOPs. (D) phyl3.4-GFP is expressed in the SOPs of ES (arrowhead) and CH (arrow) organs in the late third-instar leg disks. (E) phyl3.4-GFP expression in the SOPs of pupal nota at 14 h APF. (F) In late third-instar wing disks of sc10-1, all phyl3.4-GFP expression in SOPs is abolished except for the ones for the CH organs (arrow) at the ventral radius. (G) phyl3.4-GFP expression is abolished in sc10-1 pupal nota at 14 h APF. (H) phyl3.4-GFP expression is strongly activated by sc misexpression driven by dpp-GAL4 at the anterior-posterior boundary. (I and J) phyl3.4ΔE-GFP with four E boxes mutated is expressed weakly in SOPs of ES organs (arrowheads) in the late third-instar wing (I) and leg (J) disks, but maintains strong expression in CH SOPs (arrows). (I Inset) Magnified picture of GFP expression in wing margin SOPs, which is reduced by 50% compared to C Inset. For unknown reasons, phyl3.4ΔE-GFP shows uniform expression in the perspective notal region (I). (K) phyl3.4ΔE-GFP expression in pupal nota at 14 h APF is reduced compared to phyl3.4-GFP in E. (L) Expression of phyl3.4ΔES-GFP in late third-instar wing disk. GFP intensity in wing margin SOPs (Inset) is increased by 20% compared to phyl3.4ΔE-GFP (I Inset). (M) phyl3.4ΔES-GFP in pupal nota at 14 h APF.

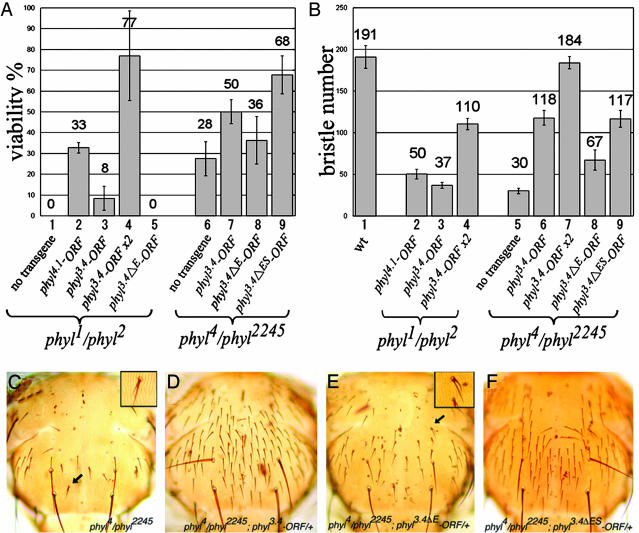

To test whether these promoter regions are sufficient for phyl in vivo function, we made phyl4.1-ORF and phyl3.4-ORF rescue constructs by fusing the 4.1- and 3.4-kb promoter regions, respectively, to the phyl ORF. The phyl1/phyl2 mutants die at late embryonic or first-instar larval stages. However, both phyl4.1-ORF and phyl3.4-ORF are sufficient to rescue the viability of phyl1/phyl2 animals to the adult stage (33 ± 3% and 8 ± 6%, respectively, Fig. 3A), with well developed ES organs on the notum (50 ± 6 and 37 ± 4, respectively, Fig. 3B). The inabilities to fully rescue the viability and ES organ number of phyl1/phyl2 are caused by insufficient expression levels of the transgenes, as suggested by the fact that two copies of phyl3.4-ORF further improve the viability of the phyl1/phyl2 mutants to 77% (Fig. 3A) and increase the bristle number to 110 ± 7 (Fig. 3B). Hypomorphic phyl4/phyl2245 mutants, which display a greatly reduced number of ES organs on the notum (30 ± 3), are completely rescued by two copies of phyl3.4-ORF (184 ± 7) (Fig. 3B). Therefore, all of these results show that both 4.1- and 3.4-kb regions of the phyl promoter contain sufficient temporal and spatial information in regulating phyl expression.

Fig. 3.

Mutations in E1-4 sites reduce phyl promoter activity. (A and B) Abilities of the phyl transgenes to rescue the viability (A) and ES organ number (B)of phyl mutants. At least three independent lines were used for each transgene. (A) The percentage of viability is calculated as the number of adult flies with indicated genotypes divided by the number of phyl2/+; transgene/+ flies or phyl2245/+; transgene/+ flies. (B) The ES organ numbers are averaged from six male nota for each independent line. (C-F) Adult nota of phyl4/phyl2245 (C), phyl4/phyl2245 with one copy of phyl3.4-ORF (D), one copy of phyl3.4ΔE-ORF (E), or one copy of phyl3.4ΔES-ORF (F). Double hair/socket phenotype indicated by arrows in C and E is magnified in Insets.

We then tested whether activity of the 3.4-kb promoter region is regulated by ac and sc. sc10-1 is a compound mutation in which both ac and sc are inactivated (3). Expressions of phyl3.4-GFP in sc10-1 wing disks and pupal nota are abolished (Fig. 2 F and G). In contrast, when sc is misexpressed by dpp-GAL4 at the anterior/posterior boundary of the wing disk, phyl3.4-GFP is strongly activated in this region (Fig. 2H). Similar results are also observed for phyl4.1-GFP (data not shown). Therefore, these results clearly show that proneural genes ac and sc are necessary and sufficient to activate phyl promoter activity.

To test whether Ac and Sc directly regulate phyl expression, we mutated all four E boxes in the 3.4-kb promoter region (Fig. 2 A) to make the phyl3.4ΔE-GFP. The expression of phyl3.4ΔE-GFP in the SOPs of ES organs in late third-instar wing and leg disks (Fig. 2 I and J, arrowheads) and in pupal nota (Fig. 2K) is strongly reduced when compared to the expression of phyl3.4-GFP. When the GFP intensity was quantified in the anterior wing margin SOPs, E box mutations in the 3.4-kb promoter region contribute to a 50% reduction (see Insets in Fig. 2 C and I). In contrast, the expression level of phyl3.4ΔE-GFP in the SOPs of chordotonal (CH) organs promoted by the proneural gene ato is comparable to that of phyl3.4-GFP (Fig. 2 I and J, arrows). These results indicate that the phyl promoter is activated by Ac and Sc through these four E boxes. To test the in vivo significance of the four E boxes, we compare the rescue abilities between phyl3.4-ORF and phyl3.4ΔE-ORF. Although phyl3.4-ORF can rescue phyl1/phyl2 to the adult stage, phyl3.4ΔE-ORF-rescued animals only survive to the third-instar larval stage (Fig. 3A). The abilities of phyl3.4ΔE-ORF to rescue the viability and the notal ES organ of phyl4/phyl2245 mutants are strongly reduced to 36 ± 11% and 67 ± 12, respectively (Fig. 3 A and B). Many of the rescued ES organs show abnormal configuration such as double hair/double socket (Fig. 3E, arrow and Inset), which is a phenotype frequently observed in hypomorphic phyl mutants (Fig. 3C, arrow and Inset) (22). Therefore, these results suggest that these four E boxes are required for full phyl promoter activity in SOPs.

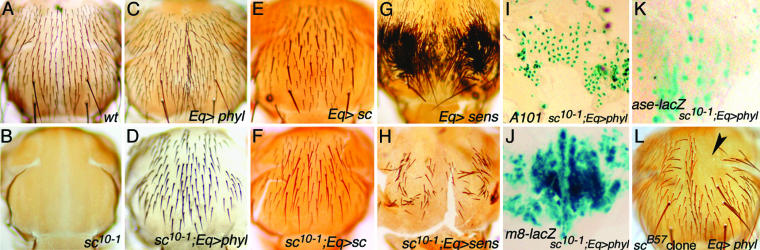

phyl Is Sufficient to Induce ES Organ Development in the Absence of Proneural Genes ac and sc. In sc10-1 flies, phyl expression is diminished and ES organ development is disrupted (Fig. 4B). We then asked whether forced expression of phyl can functionally substitute for the absence of ac and sc activities. Misexpression of phyl by Eq-GAL4 in sc10-1 flies efficiently rescues ES organ formation (Fig. 4D), to a level similar to that rescued by misexpression of the proneural gene sc (Fig. 4F). The rescued ES organs by phyl are arranged in a pattern similar to that of the wild-type flies; the ES organs are aligned in rows and well separated. SOP-specific expressions of neu-LacZ (A101), ase-LacZ, Sens, and Cut, as well as expression of E(spl)m8-LacZ, are restored (Fig. 4 I-K and data not shown). As a comparison, we misexpressed sens, whose expression also depends on ac and sc (19), by Eq-GAL4 and found that it poorly rescues sc10-1 in ES organ formation (Fig. 4H), although sens is more effective than phyl and sc in inducing ES organs in wild-type background (Fig. 4 C, E, and G). Therefore, these results suggest that phyl is able to execute the developmental program of ES organs in the absence of proneural genes ac and sc.

Fig. 4.

phyl rescues ac and sc mutants in ES organ development. (A) Wild-type notum. (B)Inthe sc10-1 notum, all ES organs are missing. (C) Expression of phyl by Eq-GAL4 (indicated by Eq>phyl) induces ectopic ES organs. (D) Misexpression of phyl restores ES organs in sc10-1. (E) Expression of sc by Eq-GAL4 in a Sb background. (F) Expression of sc by Eq-GAL4 restores ES organs in sc10-1.(G) Expression of sens by Eq-GAL4 induces numerous ES organs. (H)In sc10-1, only a few ES organs are restored by sens misexpression. (I-K) Expression of phyl by Eq-GAL4 restores A101 (I), E(spl)m8-lacZ (J), and ase-LacZ (K) expression in sc10-1. (L) Misexpression of phyl is unable to rescue the ES organ-missing phenotype in scB57 mutant clone (the balding region is indicated by the arrow).

Ac and Sc activate the bHLH gene ase in SOPs to promote SOP differentiation. Misexpression of ase or another bHLH gene lethal of scute (l'sc) (37) is capable to generate ES organs independent of ac and sc (15). We then tested whether phyl can rescue ES organ formation in the absence of all four bHLH genes, ac, sc, ase, and l'sc, in scB57 mutant clones. Although, in a control experiment, misexpression of sc can rescue the ES organ formation in scB57 mutant clones (data not shown), misexpression of phyl fails to rescue (Fig. 4L). From this result, we infer that phyl requires ase (and/or l'sc) in inducing ES organ formation.

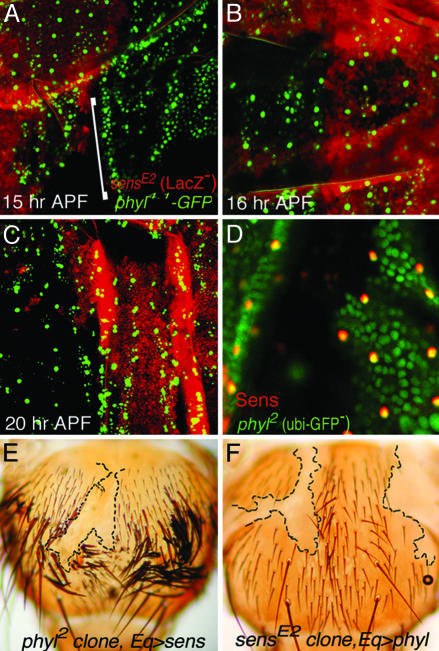

Relationship Between phyl and sens in ES Organ Development. Our promoter analysis suggests that phyl expression in SOPs might be activated by factors other than Ac and Sc. Within the 4.1-kb promoter region, eight putative Sens-binding sites (AAATCA, S box) were identified, with three sites distributed within the 3.4-kb proximal region and five sites in a cluster located in a very distal region (see Fig. 2 A). We then tested whether Sens plays a role in phyl activation in SOPs, using phyl4.1-GFP as a reporter. At 10-12 h APF, phyl4.1-GFP is expressed in dorsoventral stripes along the notum in a pattern analogous to early Ac and Sc expression patterns (data not shown). At 15 h APF, phyl4.1-GFP expression is restricted in SOPs (Fig. 5A, LacZ-positive tissue). In sensE2-null clones (LacZ-negative tissue), phyl4.1-GFP is expressed in dorsoventral stripes (indicated by a bracket in Fig. 5A), and this expression is quickly restricted to single SOPs at 16 h APF, identical to that in wild-type tissue (Fig. 5B). At 20 h APF, when wild-type SOPs have divided to two daughter cells, phyl4.1-GFP expression in sensE2 clones is still maintained in single SOPs (Fig. 5C), and mostly in two cells at 23 h APF when wild-type cells are in GFP-positive clusters containing three or four cells (data not shown). Therefore, these results suggest that, in the absence of sens activity, SOP development is delayed, but phyl4.1-GFP expression is minimally affected.

Fig. 5.

Relationship between phyl and sens in expression and function in ES organ development. (A) The phyl4.1-GFP expression pattern at 15-h APF. When GFP expression is restricted to single SOPs in wild-type tissue (LacZ-positive in red), the phyl4.1-GFP expression in the sensE2 clone (lack of LacZ staining) remains in stripes. (B) phyl4.1-GFP is expressed in SOPs in a similar pattern and level in both wild-type and sensE2 mutant tissues at 16 h APF. (C) When GFP is expressed in two SOP daughter cells in wild-type tissue at 20 h APF, the phyl4.1-GFP is still expressed in single cells in sensE2 mutant tissue. (D) Sens expression in SOPs is strongly reduced in phyl2 mutant clones. Anti-Sens staining is shown in red, and the mutant clone is marked by the lack of ubi-nGFP expression (green). (E) Expression of sens by Eq-GAL4 fails to rescue the ES organ-missing defect in phyl2 mutant clones. Clone is identified by the presence of trichome phenotype (pwn-), and clone boundary is marked by black dashed lines. (F) Similarly, expression of phyl by Eq-GAL4 fails to rescue the ES organ-missing defect in sensE2 mutant clones, which are identified by the absence of y+ expression in epidermis.

To determine the contribution of Sens binding sites to phyl expression, we used the 3.4-kb phyl promoter region whose expression pattern is analogous to the 4.1-kb promoter in both wild-type and sens mutant background (Fig. 2 and data not shown). The phyl3.4ΔS-GFP reporter with all three S boxes mutated expresses little difference in the GFP pattern and intensity when compared to phyl3.4-GFP (data not shown). However, the reporter with mutations in all four E boxes and three S boxes (phyl3.4ΔES-GFP) enhances GFP intensity by 20% when compared to phyl3.4ΔE-GFP with mutations only in four E boxes (Fig. 2 L and M). This 20% increase in GFP intensity reflects an increase in the phyl activity in vivo because phyl3.4ΔES-ORF shows stronger abilities than phyl3.4ΔE-ORF in rescuing both the viability and the ES organ number of phyl4/phyl2245 flies (Fig. 4 A, B, E, and F). Therefore, these data suggest that these S boxes play a negative role in regulation of phyl activity.

To test whether phyl regulates sens expression, we examined Sens protein expression in phyl mutants. In phyl2-null clones, Sens expression is almost diminished in all stages examined, including the single-SOP stage (Fig. 5D), the two-cell stage and the four-cell stage (data not shown), suggesting that phyl is required for Sens expression in ES organ development.

To analyze the functional relationship between phyl and sens further, we performed rescue experiments. Misexpression of sens by Eq-GAL4 fails to induce ES organ formation in phyl2 mutant clones (Fig. 5E). Similarly, ES organ formation induced by phyl misexpression is blocked in sensE2 mutant clones (Fig. 5F). This result suggests that although Sens expression depends on phyl activity, they function in parallel to promote ES organ development.

Discussion

It is generally thought that neurogenesis in both vertebrates and invertebrates is regulated by a cascade of bHLH proteins for the specification and differentiation of neural precursors (38, 39); however, phyl is a non-bHLH gene that can functionally substitute for proneural bHLH genes to execute neural developmental program. This ability of phyl is also manifested from the analysis of phyl loss-of-function phenotypes: sens and ase required for SOP differentiation are inactivated, and neuralized (A101 insertion locus) in the activation and E(spl)-m8 in the transduction of the Notch pathway are not expressed. Furthermore, SOP cell division, a prerequisite step to generate distinct daughter cells for constructing a complete ES organ, is blocked in phyl mutants. This defect likely reflects a role for phyl in controlling cell cycle progression, because CycE expression in SOPs maintains at a basal level. Therefore, although SOPs have been selected from proneural clusters in phyl hypomorphs, they are associated with several defects as described.

Studies of proneural genes have shown that ac and sc promote ES organ identity, whereas ato promotes CH organ identity (29). cut is the selector gene to specify the ES organ identity; in its absence ES organs are transformed into CH organs and misexpression of cut transforms CH organs into ES organs (34, 35). The absence of Cut expression in phyl mutants suggests that specification of ES organ identity may be through a regulation of cut expression by Phyl. Although phyl is expressed in SOPs for both ES and CH organs, we found that, in phyl2/phyl4 and phyl1/phyl4 mutants, A101 expression in leg CH organ precursors remained normal. Also, misexpression of phyl fails to rescue ato mutants in CH organ formation (H.P. and C.-T.C., unpublished data). These results suggest that phyl only mediates functions of ac and sc in ES organ development.

In the rescue experiment for the lack of proneural activity in sc10-1, expression driven by Eq-GAL4 gave a uniform expression of Phyl on the developing notum, as visualized by the expression of a Myc-tagged Phyl (data not shown). However, the global expression of Phyl leads to patterned ES organ formation in the adult (Fig. 4D). SOP-specific expression of neu-LacZ (A101), ase-LacZ, and Sens was observed in the developing notum, suggesting that it is the activity of the Phyl protein being subjected to further regulation to activate SOP formation, but not the activity of Sens or Ase. This patterning activity was also observed when global expression of the proneural gene sc in sc10-1 mutants, although these spaced ES organs are less organized (Fig. 4F). We think that lateral inhibition in the developing tissue, in this case the developing notum, operates under the global expression of Sc and Phyl, even in the wild-type background (Fig. 4 C and E), to generate spaced SOPs. However, when Sens is ubiquitously expressed by Eq-GAL4, this lateral inhibition process is inhibited, leading to the formation of tufted ES organs on the notum (Fig. 4G). One mechanism can be mediated through antagonizing the activity of members of E(spl)-C by Sens (19, 20).

Both sens and phyl are expressed specifically in SOPs, and essential for ES organ formation. However, phyl and sens should play some distinct roles in ES organ development, as suggested by our rescue experiment (Fig. 5). sens is required for the augment of proneural protein expression, antagonism of lateral inhibition, and maintenance of cell survival (19). The result that lose of phyl activity could not be rescued by sens misexpression suggests that, although sens misexpression may activate ac and sc expression, the activity of ac and sc to promote ES organ development relies on some specific functions of phyl that cannot be substituted by sens. phyl is involved in controlling gene expression, including Sens and Ase, in SOP differentiation. Misexpression of phyl rescues ES organ development in ac and sc but not sens mutants indicates that, in addition to proneural gene enhancement, sens plays additional roles downstream of phyl. Therefore, phyl and sens have different functions, and they depend on each other in promoting ES organ formation.

One well characterized function of Phyl is to bring the Ttk protein to the ubiquitin-protein ligase Sina for degradation (40, 41). During SOP development, phyl is expressed in SOPs, and Ttk is expressed ubiquitously except in the SOPs and the proneural clusters (42). Our genetic studies among phyl, sina, and ttk suggest that phyl and sina promote ES organ development by antagonizing ttk activity (26). Ttk contains a BTB/POZ domain and functions as a transcriptional repressor (43). Therefore, degradation of Ttk can lead to the derepression of SOP-specific genes. Our studies suggest that degradation of a general transcriptional repressor play a crucial role in regulating gene expression in different aspects of neural precursor differentiation.

Acknowledgments

We thank H. J. Bellen, Y. N. Jan, J. W. Posakony, H. Richardson, the Bloomington Stock Center, and the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank for fly stocks and reagents. We are grateful to S.-D. Yeh and all members of the Chien laboratory for advice and technical support. H.P. is supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from National Science Council (NSC) of Taiwan. This study is supported by grants from NSC, National Health Research Institute, and Academia Sinica of Taiwan.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: bHLH, basic helix-loop-helix; SOP, sensory organ precursor; ES, external sensory; APF, after puparium formation; CH, chordotonal.

References

- 1.Bertrand, N., Castro, D. S. & Guillemot, F. (2002) Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3, 517-530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hassan, B. A. & Bellen, H. J. (2000) Genes Dev. 14, 1852-1865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Villares, R. & Cabrera, C. V. (1987) Cell 50, 415-424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jarman, A. P., Grau, Y., Jan, L. Y. & Jan, Y. N. (1993) Cell 73, 1307-1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang, M. L., Hsu, C. H. & Chien, C. T. (2000) Neuron 25, 57-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma, Q., Kintner, C. & Anderson, D. J. (1996) Cell 87, 43-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cau, E., Gradwohl, G., Fode, C. & Guillemot, F. (1997) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 124, 1611-1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Artavanis-Tsakonas, S., Rand, M. D. & Lake, R. J. (1999) Science 284, 770-776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cubas, P., de Celis, J. F., Campuzano, S. & Modolell, J. (1991) Genes Dev. 5, 996-1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Skeath, J. B. & Carroll, S. B. (1991) Genes Dev. 5, 984-995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campuzano, S., Balcells, L., Villares, R., Carramolino, L., Garcia-Alonso, L. & Modolell, J. (1986) Cell 44, 303-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rodriguez, I., Hernandez, R., Modolell, J. & Ruiz-Gomez, M. (1990) EMBO J. 9, 3583-3592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cabrera, C. V. & Alonso, M. C. (1991) EMBO J. 10, 2965-2973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Caudy, M., Vassin, H., Brand, M., Tuma, R., Jan, L. Y. & Jan, Y. N. (1988) Cell 55, 1061-1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brand, M., Jarman, A. P., Jan, L. Y. & Jan, Y. N. (1993) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 119, 1-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jarman, A. P., Brand, M., Jan, L. Y. & Jan, Y. N. (1993) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 119, 19-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Culi, J. & Modolell, J. (1998) Genes Dev. 12, 2036-2047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miyata, T., Maeda, T. & Lee, J. E. (1999) Genes Dev. 13, 1647-1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nolo, R., Abbott, L. A. & Bellen, H. J. (2000) Cell 102, 349-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jafar-Nejad, H., Acar, M., Nolo, R., Lacin, H., Pan, H., Parkhurst, S. M. & Bellen, H. J. (2003) Genes Dev. 17, 2966-2978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singson, A., Leviten, M. W., Bang, A. G., Hua, X. H. & Posakony, J. W. (1994) Genes Dev. 8, 2058-2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kunisch, M., Haenlin, M. & Campos-Ortega, J. A. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91, 10139-10143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li, S., Xu, C. & Carthew, R. W. (2002) Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 6854-6865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chang, H. C., Solomon, N. M., Wassarman, D. A., Karim, F. D., Therrien, M., Rubin, G. M. & Wolff, T. (1995) Cell 80, 463-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dickson, B. J., Dominguez, M., van der Straten, A. & Hafen, E. (1995) Cell 80, 453-462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pi, H., Wu, H. J. & Chien, C. T. (2001) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 128, 2699-2710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tang, C. Y. & Sun, Y. H. (2002) Genesis 34, 39-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Masucci, J. D., Miltenberger, R. J. & Hoffmann, F. M. (1990) Genes Dev. 4, 2011-2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chien, C. T., Hsiao, C. D., Jan, L. Y. & Jan, Y. N. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 13239-13244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barolo, S., Carver, L. A. & Posakony, J. W. (2000) BioTechniques 29, 726, 728, 730, 732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bailey, A. M. & Posakony, J. W. (1995) Genes Dev. 9, 2609-2622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lecourtois, M. & Schweisguth, F. (1995) Genes Dev. 9, 2598-2608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Knoblich, J. A., Sauer, K., Jones, L., Richardson, H., Saint, R. & Lehner, C. F. (1994) Cell 77, 107-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blochlinger, K., Bodmer, R., Jan, L. Y. & Jan, Y. N. (1990) Genes Dev. 4, 1322-1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blochlinger, K., Jan, L. Y. & Jan, Y. N. (1991) Genes Dev. 5, 1124-1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blochlinger, K., Jan, L. Y. & Jan, Y. N. (1993) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 117, 441-450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jlmenez, F. & Campos-Ortega, J. A. (1990) Neuron 5, 81-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee, J. E. (1997) Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 7, 13-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kintner, C. (2002) J. Neurosci. 22, 639-643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tang, A. H., Neufeld, T. P., Kwan, E. & Rubin, G. M. (1997) Cell 90, 459-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li, S., Li, Y., Carthew, R. W. & Lai, Z. C. (1997) Cell 90, 469-478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Badenhorst, P., Finch, J. T. & Travers, A. A. (2002) Mech. Dev. 117, 87-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harrison, S. D. & Travers, A. A. (1990) EMBO J. 9, 207-216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]