Abstract

Introduction: Hyperglycemia is a serious health problem prevailing in diabetes patients. Treatment for hyperglycemia by various oral anti-hyperglycemic drugs have associated with side effects, hence there is growing awareness towards the use of herbal products due to their efficacy, minimal side effects and relatively low costs. This study is designed to evaluate anti-hyperglycemic activity of Caralluma umbellata Haw, which is used as a traditional medicinal plant all over India through in vitro studies.

Methods: Methanolic, aqueous and hydro methanolic extracts of Caralluma umbellata were prepared and studied for their anti hyperglycemic activity. The extracts were evaluated for glucose uptake in L6 myotubes in vitro. In addition, the inhibitory activity against alpha amylase and pancreatic lipase was also measured.

Results: The methanolic extract (MCU) was found to have significant glucose uptake. Further, MCU was also found to have promising role in inhibiting alpha amylase and pancreatic lipase.

Conclusion: The results of present study shows Caralluma umbellata has potential antidiabetic property, thus providing a further scope for study in animal model and understanding the mechanism of action.

Keywords: Diabetes mellitus, PI3 kinase, Wortmannin, Alpha amylase, Pancreatic lipase

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is a metabolic disorder which is associated by hyperglycemia with multiple disorders. A major metabolic defeat associated with diabetes is the failure of peripheral tissues in the body to utilize glucose that ultimately leads to chronic hyperglycemiaand further to other diabetes-related complications.1,2 Moreover disturbances in lipid metabolism as a result of obesity, a secondary complication arising during diabetes, may further worsen during diabetic condition. The current diabetic drugs have designed to alleviate diabetes, but not to cure it; hence targeting drugs having multiple actions for therapy is encouraging. Many plant based foods and medicines are found to be the potential sources for hypoglycemic drugs which are well documented to treat diabetes in Indian system of medicines. Even more number of traditional medicinal plants merit evaluation of therapeutic potential. Traditionally, Caralluma species claimed to have antidiabetic properties, but there are only few scientific reports to prove the same.3,4 Caralluma umbellata (C. umbellata) Haw (sub family Ascelpediaceae) belongs to Caralluma genus, distributed throughout the Indian subcontinent and widely used as vegetable. Pregnane glycosides such as carumbelloside-I to carumbelloside-V, and a flavone glycoside, luteolin-4’-O-neohesperidoside have been found to be major bioactive compounds in this species. The phytochemical study showed the presence of polyphenols suggesting it may have hypoglycemic activities,5 as the plant polyphenols are known to have hypoglycemic activities.6,7 In the present study we aimed at exploring antidiabetic potential of C. umbellata by evaluating its effect on glucose uptake in rat myotubes, inhibitory property against digestive enzymes, namely, α-amylase and pancreatic lipase.

Materials and methods

Collection and preparation of plant material

The plant material was collected from Tirupathy, Andhra Pradesh, India during May 2011. The plant material was authenticated by Dr. Madava Chetty, S .V University, Tirupathi and confirmed by comparing against the housed authenticated specimen. Aerial part was shade dried, powdered and extracted with methanol (MCU), water (ACU) successively and another set of powdered material was extracted with methanol: water (60:40) (HCU) using soxhlet apparatus. Then, MCU was dissolved in water and further fractionated by liquid-liquid extraction with ethyl acetate (EACU), chloroform (CHCU), n-butanol (BUCU) and remaining residue (RMCU). The extracted materials and separated fractions were dried under reduced pressure by rotary evaporator (Superfit, India).

In vitro cytotoxicity in L6 cell line

The cytotoxicity of test extracts and fractions were determined by MTT assay to select the non-toxic doses for glucose uptake studies.Briefly the cells were seeded in microtitre plates at a density of 2×104 cells/well, after attaining confluence the test extracts and fractions were added and incubated for 24 h. Percentage cytotoxicity was then determined as described earlier.8

Glucose uptake study of C.umbellata extracts in cultured myotubes

In vitro glucose uptake potentials of test extracts and fractions were performed in differentiated myotubes as described earlier with slight modification.9 Briefly, myotubes were serum deprived overnight, followed by incubation with glucose free medium for 1 h. The cells were treated with test extracts and fractions (500 µg/ml) and insulin (1 IU/ml) for 20 min followed by addition of 1 M glucose solution and incubated for 20 min at room temperature. At the end of the experiment cell bound glucose was measured by GOD-POD method using biochemical kit (ERBA diagnostics, Germany) at 505 nm. In the next step, bioactive sample (MCU) was evaluated for its glucose uptake potential in presence and absence of wortamannin (Sigma Aldrich, India), a PI 3-kinase inhibitor which was used to access the involvement of extract on translocation of GLUT4 to understand the mechanism of action.

Alpha amylase inhibition

The α-amylase (Hi media, Mumbai) inhibition capacity was determined by the earlier described method with minor modifications with starch as substrate.10 Briefly, inhibitory activity was determined by incubating extracts (MCU, ACU and HCU) with amylase followed by starch and Dinitrosalicyclic acid reagent to estimate the residual activity of enzyme by colorimetric estimation at 540 nm. Acarbose was used as positive control. Percentage inhibition was calculated by comparing against control reaction without test sample and IC50 values were determined by the logarithmic regression analysis.

Porcine pancreatic lipase inhibition

Porcine pancreatic lipase (PPL type II, Sigma Aldrich, India) activity was measured using p-nitrophenyl butyrate (p-NPB) (Sigma Aldrich, India) as a substrate as described earlier.11 Briefly, inhibitory activity was determined by incubating extracts (MCU, ACU and HCU) with PPL followed by p-NPB. The percentage of residual activity of PPL was determined for the test samples by comparing against control reaction without test sample. Orlistat was used as a positive control. IC50 values were determined by the logarithmic regression analysis.

Statistical analysis

Statistical comparisons were tested using One-Way ANOVA and post Dunnet’s test and the differences were considered significant at the level of p<0.05.

Results

In vitro cytotoxicity

The cytotoxicity of test extracts and fractions was found to be moderate with CTC50 values ranging between 600 to >1000 µg/ml; hence for glucose uptake studies, a safe concentration of 500 µg/ml was fixed.

Glucose uptake study

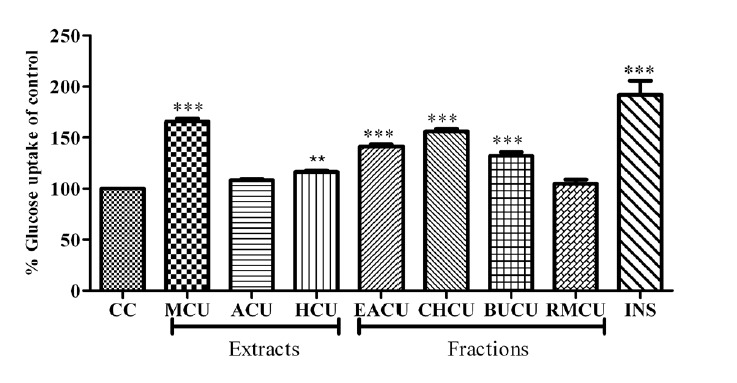

Among the extracts tested for glucose uptake, MCU showed a significant enhancement in glucose uptake with 66±2.58% uptake over basal control (Fig. 1, p<0.001). Other extracts, ACU and HCU showed moderate enhancements in glucose uptake with 8.2±1.49 and 16.3±1.3, respectively; hence MCU was further fractionated to obtain four fractions. Fractions of MCU also exhibited an increase in glucose uptake and among them, CHCU exhibited a significant uptake (Fig. 1) with 56±2.40% uptake over basal control and the rest of fractions showed moderate activity.

Fig. 1 .

Glucose uptake in myotubes by extracts and fractions of C. umbellate. Results represent Mean±SD, n=3. ** p<0.01 and ***p<0.001 compared to untreated control. MCU-methanolic extract, ACU-aqueous extract, HCU-hydro methanolic extract, EACU-ethylacetate fraction, CHCU-chloroform fraction, BUCU-butanol fraction, RMCU-remaining residue, INS-insulin.

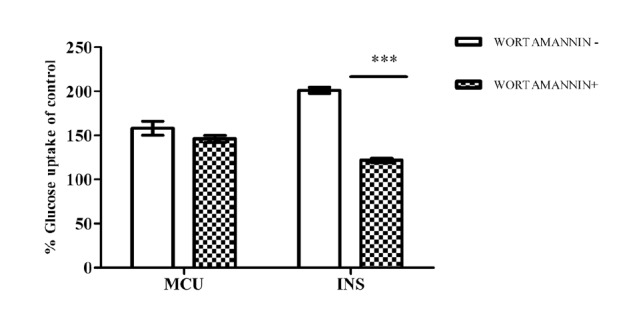

In the next set of experiments, the potent extract MCU was evaluated to understand the mechanism of action and experiments were performed in presence and absence of wortmannin. In presence of wortmannin, the glucose uptake by MCU was found to be at lower level with 39±2.09% over basal control whereas in absence of wortmannin, MCU exhibited 58±7.97% uptake. Insulin (INS) also showed a significant reduction in uptake in the presence of wortmannin as shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2 .

The effect of inhibition of PI3 kinase on glucose uptake by MCU. Myotubes were incubated with wortamannin 100 nm for 20 min followed by treatment with MCU for 30 min. Results represent Mean±SD of three independent experiments. ***p<0.001 compared to untreated control without wortmannin. (+) with wortamannin, (-) without wortamannin.

Alpha amylase and pancreatic lipase inhibition

The extracts (MCU, ACU and HCU) were also evaluated for their activity against digestive enzymes and all the three extracts showed inhibitory action against both alpha amylase and pancreatic lipase in a dose dependent manner. Among the extracts, MCU showed the highest activity at 1000 µg/ml with the IC50 found to be at 853±10.41 µg/ml. The standard acarbose showed potent inhibition with the IC50 of 323.97±4.91 µg/ml against alpha amylase (Table 1). Against pancreatic lipase, HCU showed a better activity with the IC50 which was found to be at >1000 µg/ml and standard orlistat IC50 was found to be 0.15±0.03 µg/ml (Table 1).

Table 1 . Alpha amylase and pancreatic lipase inhibition .

| Sl. No | Test sample |

Test concentration

(µg/ml) |

% Alpha amylase inhibition | % Pancreatic lipase Inhibition |

| 1 | MCU | 1000 | 52.27±1.12 | 21.6±0.61 |

| 500 | 40.68±1.24 | 7.1±3.74 | ||

| 250 | 39.23±1.73 | 4.3±2.13 | ||

| 2 | ACU | 1000 | 37.08±1.09 | 26.3±03.20 |

| 500 | 34.59±1.01 | 22.5±02.58 | ||

| 250 | 31.18±1.93 | 19.2±01.87 | ||

| 3 | HCU | 1000 | 45.33±0.90 | 29.6±2.49 |

| 500 | 39.41±5.47 | 20.6±1.60 | ||

| 250 | 37.13±4.13 | 15.0±2.36 | ||

| 4 | Acarbose | 1000 | 68.00±1.17 | ND |

| 500 | 52.07±2.39 | ND | ||

| 250 | 44.49±1.69 | ND | ||

| 5 | Orlistat | 10 | ND | 85.0±0.82 |

| 5 | ND | 81.5±0.25 | ||

| 2.5 | ND | 80.7±1.62 |

Result represented in Mean±SD (n=3), MCU-methanolic extract, ACU-aqueous extract, HCU- hydro methanolic extract, ND- not determined.

Discussion

C. umbellata has been used as a traditional medicinal plant for treating stomach disorders and abdominal pains.12 Very few attempts were made to evaluate its pharmacological efficacy. Recent scientific reports have suggested that this plant has hepatoprotective, antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory properties,12,5 however other traditional claims and possible pharmacological benefits of C. umbellata were not been explored. Other species from the same genus were reported to have different biological properties, which suggest the therapeutic potential of caralluma genus. In present study, C. umbellata showed promising antidiabetic properties, especially the methanolic extract of whole plant (MCU) exhibited potential glucose uptake enhancement in myotubes, hence this extract may regulate the blood glucose level.9 Comparable significant activities were also reported from other medicinal plants such as A. cepa, Z .officinale, G. lucidum showing promising activity up to 95% glucose uptake over control, hence suggesting the potential use of medicinal plants for diabetic treatment.13,14 ACU and HCU showed moderate uptake comparable to MCU which the differences in uptake may be due to the presence of certain class of phytochemicals. As stated earlier, polyphenols have been reported to have antidiabetic effect and such polyphenols have been found highly in methanolic extracts as suggested by various authors,15 however the exact chemical constituents which may be responsible for hypoglycemic effect of extracts still remains speculative. Previous studies also support this data where alcoholic extracts from different species of similar genus, C. attenuata, C. fimbriata and C. sinaica, had shown potent antidiabetic properties.4,6

Glucose uptake in skeletal muscle through GLUT4 translocation is an important step in controlling blood glucose level. Other way PI3 kinase regulates GLUT4 translocation and plays a major role in blood glucose management. Thus to understand the mechanism of action, experiments were performed in presence and absence of a specific blocker of PI3 kinase, wortmannin. The observed difference was marginal in presence of wortamannin, hence the uptake from MCU may be partially through PI3 kinase mediated GLUT4 translocation and may also act at multiple pathways in enhancing uptake of glucose in myotubes.16,17

Inhibiting the target enzyme responsible for glucose metabolism is one among the key approaches in controlling diabetes. Alpha amylase is one among such enzymes involved in carbohydrate metabolism. Inhibition of amylase may lead to delay in glucose metabolism and hence a net reduction of available glucose for absorption and thus controlling glucose level.18-20 Apart from targeting enzymes related to carbohydrate metabolism, another enzyme responsible for the hydrolysis of total dietary fats is the pancreatic lipase which breaks down fats to triacylglycerols.21 Inhibiting pancreatic lipase reflects in reduced absorption of monoglycerides and fatty acids.22,23 Hence pancreatic lipase inhibition is found to be a valuable target for the treatment of diet-induced hyperglycemia in humans, thus indicating its beneficial role in managing obesity related complications occurring in diabetes.24 Interestingly, MCU also inhibited both pancreatic lipase and alpha amylase in vitro in a dose dependent manner. Hence the observed inhibitory activity may be due to polyphenols present in the extracts as suggested by various authors.24,25 These observations indicate that MCU has got a potential to act at multiple points viz stimulating glucose uptake and inhibiting alpha amylase and pancreatic lipase.

Conclusion

The glucose uptake activity of C. umbellata may be partially attributed to the GLUT4 translocation as well as to other pathways which has to be studied thoroughly by gene expression studies and also it may be necessary to investigate type of mechanism involved in inhibition of amylase and pancreatic lipase by kinetic studies. Furthermore identifying active phytoconstituents responsible for such activities which can strengthen the use for therapeutic applications are in progress in our laboratory.

Ethical Issues

There is none to be applied.

Competing interests

There is none to be declared.

References

- 1.Rother KI. Diabetes treatment bridging the divide. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1499–501. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp078030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clements RS Jr, Bell DS. Complications of diabetes: prevalence, detection, current treatment, and prognosis. Am J Med. 1985;79:2–7. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(85)90503-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Habibuddin M, Daghriri HA, Humaira T, Qahtani M, Hefzi A. Antidiabetic effect of alcoholic extract of Caralluma sinaica Lon streptozotocin-induced diabetic rabbits. J Ethnopharmacol. 2008;117:215–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Latha S, Rajaram K, Suresh Kumar P. Hepatoprotective and antidiabetic effect of methanol extract of Caralluma fimbriata in streptatozocin induced diabetic albino rats. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2004;6:665–68. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shanmugam G, Ayyavu M, Dowlathabad MR, Thangadurai D, Ganesan S. Hepatoprotective effect of Caralluma umbellata against acetaminophen induced oxidative stress and liver damage in rat. Journal of Pharmacy Research. 2013;6:342–45. [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Sousa E, Zanatta IS, Pizzolatti MG, Szpoganicz B, Barreto Silva FRM. Hypoglycemic effect and antioxidant potential of Kaempferol-3, 7-O-(r)-di rhamnoside from Bauhinia forficata leaves. J Nat Prod. 2004;6:829–32. doi: 10.1021/np030513u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanamura T, Toshihiko H, Hirokazu K. Structural and functional characterization of polyphenols isolated from Acerola (Malpighia emarginata DC) fruit. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2005;69:280–6. doi: 10.1271/bbb.69.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bellamakondi P, Godavarthi A, Ibrahim M, Kulkarni S, Naik RM, Maradam S. In vitro cytotoxicity of caralluma species by MTT and trypan blue dye exclusion. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2014;7:17–19. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kawanoa A, Nakamurab H, Hatab S, Minakawaa M, Miuraa Y, Yagasaki K. Hypoglycemic effect of aspalathin, a rooibos tea component from Aspalathus linearis, in type 2 diabetic model db/db mice. Phytomedicine. 2009;16:437–43. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oboh G, Ademiluyi AO, Faloye YM. Effect of combination on the antioxidant and inhibitory properties of tropical pepper varieties against α-amylase and α-glucosidase activities in vitro. J Med Food. 2011;14:1152–58. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2010.0194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bustanji Y, Issa A, Mohammad M, Hudaib M, Tawah K, Alkhatib H. et al. Inhibition of hormone sensitive lipase and pancreatic lipase by Rosmarinus officinalis extract and selected phenolic constituents. J Med Plants Res. 2010;4:2235–42. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramesh M, Nageshwara RY, Rama KM, Rao A, Prabhakar MC, Madhava Reddy B. Antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory activity of carumbelloside-I isolated from Caralluma umbellata. J Ethnopharmacol. 1999;68:349–52. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(99)00122-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Noipha K, Ratanachaiyavong S, Ninla-aesong P. Enhancement of glucose transport by selected plant foods in muscle cell line L6. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;89:e22–e26. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2010.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jung KH, Ha E, Kim MJ, Uhm YK, Kim HK, Hong SJ. et al. Ganoderma lucidum extract stimulates glucose uptake in L6 rat skeletal muscle cells. Acta Biochim Pol. 2006;53:597–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khoddami A, Wilkes MA, Roberts TH. Techniques for Analysis of Plant Phenolic Compounds. Molecules. 2013;18:2328–75. doi: 10.3390/molecules18022328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng Z, Pang T, Gu M, Gao AH, Xie CM, Li JY. et al. Berberine-stimulated glucose uptake in L6 myotubes involves both AMPK and p38 MAPK. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1760:1682–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wijesekara N, Thong FSL, Antonescu CN, Klip A. Diverse Signals Regulate Glucose Uptake into Skeletal Muscle. Can J Diabetes. 2006;30:80–8. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rhabasa-Lhoret R, Chiasson JL. Alpha-glucosidase inhibitiors. 3rd edition. In: Defronzo RA, Ferrannini E, Keen H, Zimmet P, editors. International Textbook of Diabetes Mellitus. Chichester:John Wiley; 2004.

- 19.Bhandari MR, Nilubon JA, Hong G, Kawabata J. α-Glucosidase and α- amylase inhibitory activities of Nepalese medicinal herb Pakhanbhed (Bergeniaciliata, Haw) Food Chem. 2004;106:247–52. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim JS, Hyun TK, Kim MJ. The inhibitory effects of ethanol extracts from sorghum, foxtail millet and proso millet on α-glucosidase and α-amylase activities. Food Chem. 2011;124:1647–51. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Birari RB, Bhutani KK. Pancreatic lipase inhibitors from natural sources: unexplored potential. Drug Discov Today. 2007;12:879–9. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2007.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lowe ME. Pancreatic triglyceride lipase and colipase: insights into dietary fat digestion. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:1524–36. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90559-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim TH, Kim JK, Ito H, Jo C. Enhancement of pancreatic lipase inhibitory activity of curcumin by radiolytic transformation. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2011;21:1512–14. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.12.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu S, Li D, Huang B, Chen Y, Lu X, Wang Y. Inhibition of pancreatic lipase, α-glucosidase, α-amylase, and hypolipidemic effects of the total flavonoids from Nelumbo nucifera leaves. J Ethnopharmacol. 2013;149:263–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sugiyama H, Akazome Y, Shoji T, Yamaguchi A, Yasue M, Kanda T. et al. Oligomeric procyanidins in apple polyphenol are main active components for inhibition of pancreatic lipase and triglyceride absorptionJ. Agric Food Chem. 2007;55:4604–09. doi: 10.1021/jf070569k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]