Abstract

Introduction: In order to employ Nicotiana tabacum cells as a profitable natural bioreactor for production of bio-functional "Soluble human TRAIL" (ShTRAIL), endoplasmic reticulum (ER) targeted expression and innovative extraction procedures were exploited.

Methods: At first, the ShTRAIL encoding gene was sub-cloned into designed H2 helper vector to equip it with potent TMV omega leader sequences, ER sorting signal peptide, poly-histidine tag and ER retention signal peptide (KDEL). Then, the ER targeted ShTRAIL cassette was sequentially sub-cloned into "CaMV-35S" helper and "pGreen-0179" final expression vectors. Afterward, Agrobacterium mediated transformation method was adopted to express the ShTRAIL in the ER of N. tabacum . Next, the ShTRAIL protein was extracted through both phosphate and innovative ascorbate extraction buffers. Subsequently, oligomerization state of the ShTRAIL was evaluated through cross-linking assay and western blot analysis. Then, semi-quantitative western blot analysis was performed to estimate the ShTRAIL production. Finally, biological activity of the ShTRAIL was evaluated through MTT assay.

Results: The phosphate buffer extracted ShTRAIL was produced in dimmer form, whereas the ShTRAIL extracted with ascorbate buffer generated trimer form. The ER targeted ShTRAIL strategy increased the ShTRAIL’s production level up to about 20 μg/g of fresh weight of N. tabacum . MTT assay indicated that ascorbate buffer extracted ShTRAIL could prohibit proliferation of A549 cell line.

Conclusion: Endoplasmic reticulum expression and reductive ascorbate buffer extraction procedure can be employed to enhance the stability and overall production level of bio-functional recombinant ShTRAIL from transgenic N. tabacum cells.

Keywords: Molecular farming, TRAIL, Endoplasmic expression, Ascorbate extraction buffer, Nicotiana tabacum

Introduction

Molecular farming is a prospective field for the production of biopharmaceuticals. Numerous therapeutic enzymes, antibodies, cytokines, hormones, and vaccines have been manufactured in different plant species.1 Despite having the lowest production cost and no risk of contamination with human pathogens, plant based expression systems have not succeeded in markets for biopharmaceuticals.2 Indeed, the main reason for this failure may be attributed to the lowest production level in plants in comparison to other expression systems.3 Consequently, several strategies have been developed to enhance the recombinant protein production in plant expression systems.4

With respect to enhancement of transcription and translation level strategies, numerous molecular biotechnology techniques have been exploited, particularly: I) adapting either strong constitutive (e.g. CaMV 35S)5 or proper inducible promoter (e.g. Estradiol-inducible XVE promoter);6,7 II) employing enhancer heterologous 5’ untranslated region (e.g. TMV omega leader sequence);8 III) utilizing optimized codon usage;9 VI) applying stabilizer heterologous 3’ untranslated region.10 Note that the combination of these strategies was usually employed as reviewed in reference.11

Regarding minimizing the degradation and instability of recombinant proteins in plants, there are several remedial strategies including: I) targeting the expression of protein to a particular organ, for example, through adapting seed specific promoter;12 II) sorting the protein to subcellular locations by signal peptides such as endoplasmic reticulum13 and chloroplast;14 III) targeting the protein to the secretary pathways;15 VI) co-expression of protease inhibitors like Tomato Cathepsin D inhibitor;16 V) expressing fusion proteins.17 Each mentioned strategy shows its own strengths and limitations in improving the stability of recombinant proteins which are reviewed recently.18,19

Accordingly, in order to facilitate the recombinant protein purification, several approaches have been adopted mostly: I) choosing the proper host, as tomatoes for edible vaccine;20 II) targeting the protein to the secretary pathways ;21 III) targeting the protein to the subcellular compartment, for instance, oil bodies of oilseed crops;22 VI) employing appropriate purification system like affinity chromatography,23 and specific precipitation;24 V) optimizing extraction buffer and condition.25 According to the application of recombinant protein, the system of expression and the availability of purification systems, one or combination of the strategies is preferred.

Correspondingly, in the current study the combinations of these strategies were employed to enhance the production level of biopharmaceutical candidate “Soluble human TNF Related Apoptosis Inducing Ligand” (ShTRAIL) in Nicotiana tabacum (N. tabacum) cells. ShTRAIL is one of the immune system’s modulators with promising capability in targeted cancer therapy.26 Therefore, several attempts have been made on the production of the ShTRAIL in different expression systems.27-29 Wang and colleagues tackled the production of the ShTRAIL in N. tabacum varieties through chloroplast engineering. However, the western blot analysis indicated that chloroplast engineering was not effective strategy in accumulating the ShTRAIL in the N. tabacum.30 In another attempt, our groups produced the ShTRAIL in the N. tabacum through Agrobacterium-mediated nuclear transfection method.31 Although N. tabacum can produce and accumulate the ShTRAIL in this system, the total production level was relatively low (about 14 μg/g fresh weight) and there was not any significant detectable bio-functionality regarding MTT assay.

Consequently, in this study we evaluated the impact of endoplasmic reticulum expression and innovative protein extraction procedures on the production level and bio-functionality of the extracted recombinant ShTRAIL. In this regard, at first, the expression enhancer elements and the endoplasmic reticulum sorted KDEL signal peptide were added to the ShTRAIL encoding gene. Then, the ShTRAIL protein was extracted through new developed ascorbate buffer. Finally, western blot and MTT assay analyses were employed to evaluate these modifications.

Materials and methods

Reagents

General molecular biology reagents including Tris-Base, SDS, Acrylamide, Bisacrylamide and Agarose were purchased from CinnaGene, Iran. Most of the required enzymes including pfu DNA polymerase, T4 DNA Ligase, BamHI, BglII, EcoRV, EcoRI, HindIII and KpnI were obtained from Fermentase. 35S-CaMV plasmid and pGreen-0179 were purchased from John Innes Centre, UK. Agrobacterium tumefaciens LBA 4404 and N. tabacum cell line were kindly donated by NIGEB and Dr Ghanati (Tarbiat Modares University), respectively. All requirements for plant cell culture media including major and minor minerals, hormones (e.g., Indole acetic acid, Naphthyl acetic acid, Kinetin, Acetosyringon), vitamins and sugars (e.g., Ascorbic Acid, Myoinositol and Sucrose) were obtained from Merck, Germany. Antibiotics including Ampicillin, Kanamycin, Tetracycline, Hygromycin, Streptomycin and Cefotaxime were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Germany. Poly Vinyl Poly Pyrrolidone (PVPP), Dithiothreitol, glutaraldehyde and NaBH4 were also purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Germany. Phenyl Methyl Sulfonyl Fluoride (PMSF) protease inhibitor and nitrocellulose membrane were acquired from Roche, Germany. Bio-Rad DC protein assay Kit and Bovine Serum Albumin were used to determine protein concentration. Recombinant TRAIL (ab168898) as standard along with TRAIL polyclonal antibody (ab2435), anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibodies (ab131365 and ab97051) were purchased from Abcam, United States. A549 cell line (ATCC® CCL-185™) as a cancer model was obtained from Pasteur Institute of Iran.

Methods

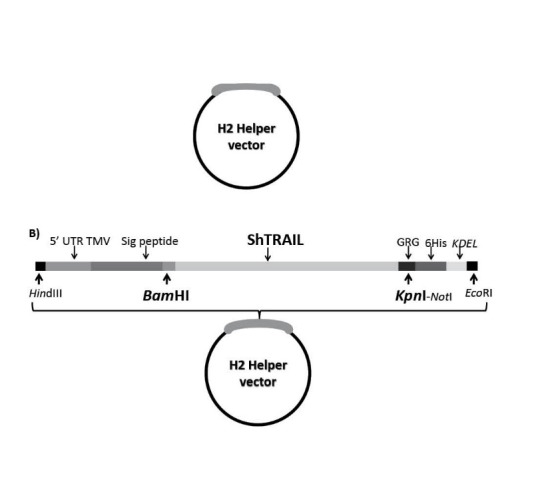

Construction of endoplasmic reticulum targeted helper expression vector

In order to facilitate the expression of recombinant protein in N. tabacum, several requirements were adjoined to each other through synthesizing H2 helper vector on the backbone of pGH vector. The H2 helper expression vector mainly contains strong ribosome binding site from 5’UTR of Tobacco Mosaic Virus (Omega leader sequence), endoplasmic reticulum targeted N. tabacum’s pathogenesis-related protein 1 N-terminal and C-terminal KDEL sequences, purification facilitator six-histidine tag and proper restriction enzymes digestion sites (Fig. 1.A).

Fig. 1 .

Schematic diagram of ShTRAIL cloning into endoplasmic sorter H2 helper vector to obtain endoplasmic targeted ShTRAIL gene. Panel A) represents different components of endoplasmic sorting H2 helper vector; 5’UTR form TMV; N terminal Signal peptide of N. tabacum’s pathogenesis-related protein 1; 6His-Tag and C-terminal KDEL signal peptide. Panel B) represents cloning of ShTRAIL gene between BamHI and KpnI regions of the H2 helper vector.

Cloning ShTRAIL encoding sequence into plant endoplasmic sorting expression vector

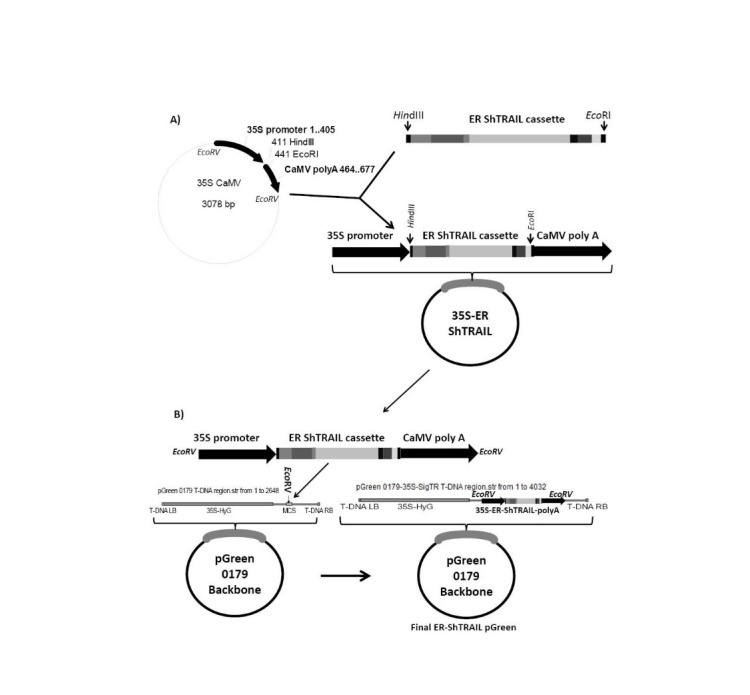

To express ShTRAIL in the ER of N. tabacum cells, initially the ShTRAIL’s encoding sequence from our last experiment31 was equipped with BamHI and KpnI digestion sites through conducting PCR by designed BamHI-TR and KpnI-TR primers (Table 1). Then through three sub-cloning steps, desired requirements were adjoined to ShTRAIL’s encoding sequence as follows. At first, to provide strong “omega leader sequence” and “ER sorting signal peptides”, the amplified ShTRAIL was sub-cloned between BamHI and KpnI restriction sites of the H2 helper vector (Fig. 1.B). Next, the obtained ER-ShTRAIL encoding cassette was sub-cloned into the HindIII and EcoRI regions of 35S-CaMV plasmid to provide plant specific promoter and terminator (Fig. 2.A). Finally, to provide both “selectable markers” and “T-DNA” regions, the 35S-ER-ShTRAIL expression construct was sub-cloned into the EcoRV region of “pGreen-0179” plant expression vector to produce “ER-ShTRAIL-pGreen” (Fig. 2.B). The accuracy of each sub-cloning step was confirmed through appropriate PCR (Table 1) and digestion reactions.

Table 1 . Primers for PCR amplification of TRAIL cloning procedure .

| Primers sequence from 5’ to 3’ | Descriptions | |

| BamHI-TR F | GGAAAAGGGATCCGTGAGAGAAAGAGGTCCTCAGAGAG | Providing BamHI and KpnI restriction sites to ShTRAIL |

| KpnI-TR R | GGAAAAAGGTACCTCCAACTAAAAAGGCCCCGAAAAAACT | |

| M13 Uni F | GTTTTCCCAGTCACGAC | M13 universal primers |

| M13 Uni R | CAGGAAACAGCTATGAC | |

| 35S F | GATATCGTACCCCTACTCCAAAAATGTC | CaMV 35S promoter-terminator specific primers |

| 35S R | GATATCGATCTGGATTTTAGTACTGGATTTTGG | |

| Restriction enzymes digestion sites were represented as Bold Underlined texts. | ||

Fig. 2 .

Schematic diagram of endoplasmic targeted ShTRAIL gene cloning into intermediate 35S CaMV vector and pGreen-0179 plant expression vector. Panel A) represents cloning of endoplasmic targeted ShTRAIL gene between HindIII and EcoRI regions of 35S-CaMV helper plasmid to obtain 35S promoter-ER ShTRAIL -CaMV polyA (1400 bp) fragment. Panel B) represents cloning of 35S promoter- ER ShTRAIL -CaMV polyA fragment into EcoRV region of the pGreen-0179 T-DNA to obtain final ER-ShTRAIL-pGreen vector. LB and RB stands for left border and right border, respectively.

Note that to evaluate the efficiency of the ShTRAIL production via ER-ShTRAIL-pGreen vector, the cytoplasmic expressing “ShTRAIL-pGreen” vector was also constructed as described in our last experiment.31

Transformation of N. tabacum

To transform N. tabacum cells, Agrobacterium mediated gene transfer method was employed. At first, each of “ER-ShTRAIL-pGreen” and “ShTRAIL-pGreen” expression vectors along with “replication facilitator pSoup helper plasmid” were co-transformed into A. tumefaciens LBA4404, using previously described freeze-thaw method.32 Next, the transformed Agrobacteriums were used for transformation of N. tabacum cells, using co-cultivation technique.33 Finally, the eighth week transformed N. tabacum cells, screened in the selection LS medium (Hygromycin 30 μg/mL; Sefotaxim 200 μg/mL), were used in the rest of the experiments.

Protein extraction and SDS-PAGE analysis

In order to extract total protein from both transformed and untransformed N. tabacum cells, two kinds of extraction buffer were utilized: phosphate buffer (0.085 M Na2HPO4–KH2PO4 buffer; NaCl 150 mM; 10% Glycerol, pH 7.85), and ascorbate buffer ( Ascorbic acid 0.1 M; NaCl 150 mM; 10% Glycerol, Adjusted to pH 5 by NaOH). At first, two grams of N. tabacum cells were suspended in 10 ml of ice cold freshly made extraction buffers. Next, freshly made phenol scavenger PVPP, protease inhibitor PMSF and reducing agent Dithiothreitol (with final concentration of 1% w/v, 1 mM and 5 mM, respectively) were added to the mixtures. Then, cells were homogenized using Heidolph silent crusher (20000 rpm, 45 seconds, three times, ice cold), and the cell debris was separated with centrifugation (12000 rpm, 15 min, 4 °C). Following another round of centrifugation (12000 rpm, 15 min, 4°C), the supernatant was filtrated through 0.45 μm filter to remove remaining solid materials. Then, total protein extracts of N. tabacum cells were concentrated ten times using Amicon (Millipore, United kingdom) centrifugal filter devices (cut-off: 10 kDa). Meanwhile, total protein concentration was measured by means of Bio-Rad DC protein assay kit (based on the protocol), using bovine serum albumin (Bio-Rad, United Kingdom) as a standard. Afterward, a total of 200 μg of each protein sample was separated on 15% SDS-PAGE, in the reducing condition. Finally, the SDS-PAGE was stained using previously described silver-staining method.34

Cross linking assay and Western blot analysis

Oligomerization state of cytoplasmic and endoplasmic expression of recombinant ShTRAIL was evaluated via cross linking assay, as described previously with some modifications.35 At first, total proteins of transformed N. tabacum cells were extracted using both phosphate and ascorbate buffers containing 1% glutaraldehyde as a cross-linking agent. After incubating the protein extracts on ice for 3 h, the cross-linked proteins were stabilized by means of NaBH4 with final concentration of 50 mM. Subsequently, the protein samples were concentrated by acetone precipitation method.36 Afterward, the cross-linked proteins were dissolved in reducing sample buffer (Qiagen) and 200 μg of the proteins were separated on 15% SDS-PAGE. Next, the separated proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membrane using semidry transfer technique (Towbin buffer, 200 mA, 2 h, Apelex PS 304). After blocking the membrane with 5% skimmed milk, the membrane was incubated with a rabbit TRAIL polyclonal antibody (1:1000; Abcam, ab2435) for 2 h. Then, following several rounds of washing steps with Tris-Buffered Saline (TBS: 20 mM Tris-HCl, 140 mM NaCl, pH 7.5) and TBS-T buffer (TBS plus 0.1% Tween-20, v/v), the membrane was further incubated with “alkaline phosphatase conjugated” anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (1: 5000; Abcam, ab131365) for 1 h. After several washings with TBS and TBS-T buffers, the membrane was incubated with Bromo Chloro Indolyl Phosphate (BCIP) and Nitro Blue Tetrazolium (NBT) reagents in alkaline phosphatase buffer (100 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, pH 9.5) for color development. Finally, the oligomerization state of ShTRAIL was evaluated by developed bands on nitrocellulose membrane.

Semi-quantitative western blot analysis

To assess the impact of endoplasmic reticulum expression of ShTRAIL on the stability and the production level, semi-quantitative western blot analysis was performed. First, from recombinant N. tabacum cells, a total of 200 μg ascorbate buffer extracted total protein was separated on reducing the 15% SDS-PAGE. Meanwhile, a total of 100 ng from recombinant human TRAIL (ab168898) was used as a standard. Then, the same western blot procedure was applied on the protein samples by using “Horseradish peroxidase conjugated” anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (1:5000; Abcam, ab97051). Then, the ECL substrates were utilized for generating subsequent chemiluminescent bands on the X-ray film. Finally, developed bands were analyzed densitometrically using “ImageJ” software (Free software from National Institute of Health).

Biological assay

Biological activity of plant made recombinant ShTRAIL was determined through MTT assay of total protein extracts of transformed and untransformed N. tabacum on sensitive A549 cell line as described previously.31 At first, ascorbate buffer protein extracts of both transformed and untransformed N. tabacum were dialyzed against treatment buffer (150 mM NaCl, 100 μM ZnCl2, 1mM DTT and 1% Glycerol) overnight at 4 oC. Then, the samples were concentrated using Amicon centrifugal filter devices (10 kDa cut-off), and about 200 μg of each total protein extract was used for the treatment of each well. Correspondingly, 100 ng recombinant human TRAIL (ab168898) and 50 μL of treatment buffer were utilized as positive and negative controls, respectively. After 24 h, the media were replenished by new one containing extra 50 μL of MTT solution (2mg/mL in PBS) and the cells were incubated for extra 4 h. Finally, developed formazon dye was dissolved in 200 μL DMSO and the absorbance of each well was measured using BioTek Synergy 3 micro plate reader at 570 nm. Obtained data were demonstrated as Mean ± SEM. Results were implemented by Microsoft office Excel (version 2007) and SPSS (version 16.00). Statistical analyses between mean values were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and post test of least significance difference (LSD). The p value less than 0.05 was considered as significant difference.

Results

Cloning ShTRAIL into plant endoplasmic reticulum sorting expression vector

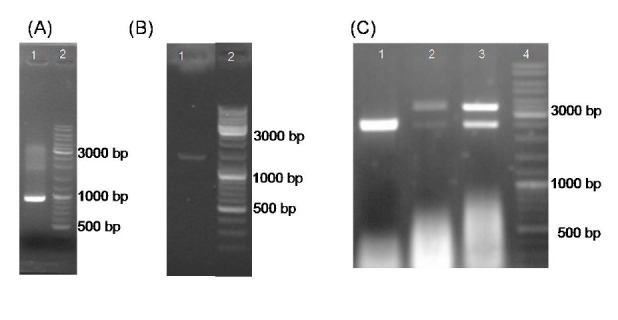

To express and accumulate ShTRAIL in the endoplasmic reticulum of N. tabacum cells, the desired requirements were provided through sequential sub-cloning steps of ShTRAIL gene into helper (H2, CaMV 35S) and expression (pGreen-0179) vectors (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2). The assembly of the ShTRAIL encoding gene with ER sorting and accumulating signal peptides in the H2 helper vector was confirmed through M13 Universal PCR (Fig. 3.A and Table 1). Likewise, the insertion of the ER sorting ShTRAIL cassette (730 bp) between plant specific CaMV 35S promoter and terminator regions (670 bp) in CaMV helper vector was confirmed by 35S specific PCR (Fig. 3.B and Table 1). Lastly, the integration of “35S CaMV promoter-ER ShTRAIL-CaMV terminator” cassette into T-DNA region of pGreen-0179 plant expression vector was confirmed through BglII enzymatic digestion (Fig. 3.C).

Fig. 3 .

Confirmation of ShTRAIL cloning procedures using electrophoresis on 2% Agarose gel. Panel (A) represents confirmation of cloning of ShTRAIL into H2 helper vector though obtaining a 1000 bp fragment via universal M13 PCR on pGH vector backbone. Panel (B) demonstrate verification of endoplasmic expression ShTRAIL gene (730 bp) cloning into 35S-CaMV helper vector expression cassette region (670 bp) through obtaining a 1400 bp fragment via 35S specific PCR. Panel (C) represents confirmation of “35S promoter-ER ShTRAIL -CaMV polyA” fragment cloning into pGreen-0179 expression plasmid through BglII digestion. Separation of the pGreen-0179 backbone (2495 bp) from the T-DNA region of the empty (2648 bp) and TRAIL contained (4032 bp) pGreen-0179 vector via BglII enzyme digestion. The empty pGreen-0179, ER-ShTRAIL-pGreen and TRAIL-pGreen were demonstrated in lane 1, lane 2 and lane3, respectively.

Protein extraction and SDS-PAGE analysis

In order to investigate the expression of ShTRAIL, total protein from both transformed and untransformed N. tabacum cells were extracted using both well established phosphate buffer25 and innovative ascorbate buffer. The optimized phosphate buffer extraction25 yielded about 1.8 mg/ml protein (Table 2). However, despite having desired capabilities to extract a large amount of protein, the optimized phosphate buffer (pH: 7.85) could facilitate oxidization of numerous plant derived phenolic compounds. Consequently, even through employing phenolic compound scavenger (PVPP 1% w/v) and reducing agent (DTT 5 mM) in the extraction buffer, the oxidized phenolic compounds led to some protein precipitation. This precipitation of proteins halted the proper protein concentrating process during employment of Amicon centrifugal filter devices.

Table 2 . Relative expression level of ShTRAIL in transformed N. tabacum cells .

| Different selected Callus cells | Total soluble protein in Crude extract (mg/ml) based on Lowry method | ShTRAIL in crude extract (μg/ml) semi quantitative western Blot | ShTRAIL % in Soluble protein Extract* | ShTRAIL (μg) in 1 g of fresh N. tabacum** |

| Cytoplasmic 8 th week | 1.6±0.1 | 3.1 | 0.19 | 15.5 |

| Endoplasmic 8 th week | 1.8±0.1 | 3.8 | 0.21 | 19.2 |

| Cytoplasmic 12 th week | 1.7±0.05 | 2.7 | 0.16 | 13.5 |

| Endoplasmic 12 th week | 1.7±0.1 | 4.8 | 0.28 | 24.5 |

* ShTRAIL % in soluble protein extract: ShTRAIL in crude extract/ Total soluble protein in Crude extract

** ShTRAIL (μg) in 1 g of fresh N. tabacum: ShTRAIL % in soluble protein extract × Total soluble protein in Crude extract × 5 (ml/ g)

Accordingly, an innovative “phenolic compound stabilizer” ascorbate extraction buffer was developed for the protein extraction. The Bio-Rad DC protein assay kit revealed that the ascorbate extraction buffer can extract about 1.7 mg/ml protein (Table 2). Indeed, through employing PVPP and DTT in ascorbate extraction buffer (pH: 5), a minimum protein precipitation occurred even in protein concentrating process.

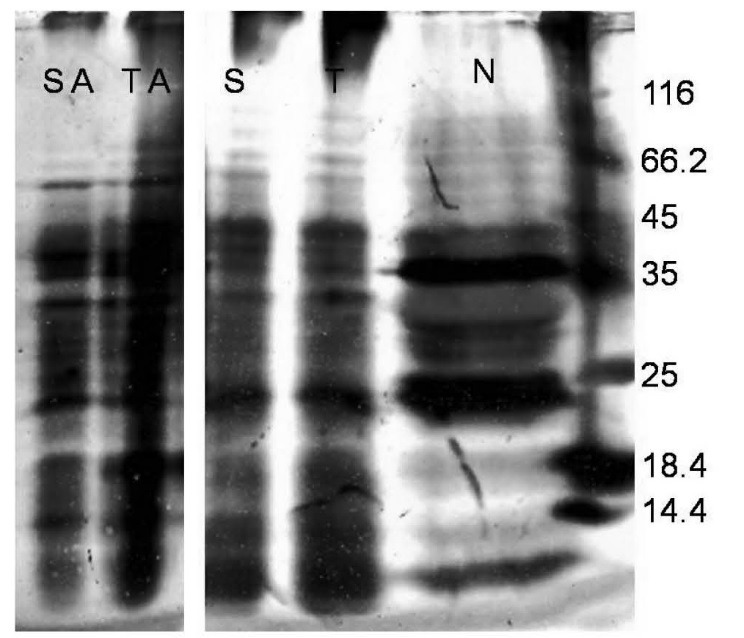

Silver stained SDS-PAGE analysis revealed that both phosphate and ascorbate buffer were able to extract N. tabacum proteins with somewhat similar pattern (Fig. 4). However, there is not any intense obvious band regarding the expression of the ShTRAIL in either cytoplasmic or endoplasmic sorted expression system in Silver stained SDS-PAGE analysis (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4 .

Silver stained SDS-PAGE analysis of ShTRAIL obtained from different transformed N. tabacum callus cells. A total of 200μg protein extract from Untransformed (N), Endoplasmic sorted (SA and S), and Cytoplasmic expressed (TA and T) ShTRAIL were separated on 15% SDS-PAGE. The lanes SA and TA represent ascorbate buffer extracted, and the lanes S and T represent phosphate buffer extracted total proteins.

Cross linking assay and Western blot analysis

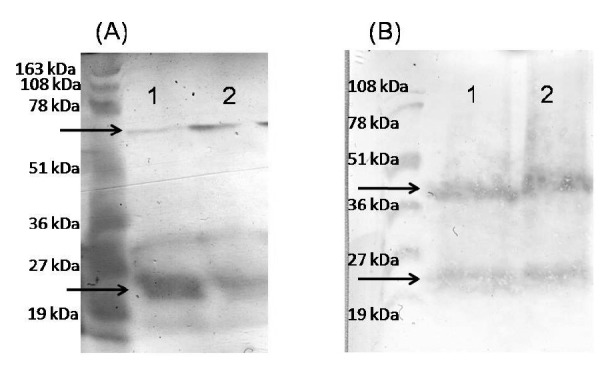

Proper self-assembly of cytoplasmic and ER produced ShTRAIL was evaluated through cross linking assay. Cross linking assay indicated that employing the ascorbate extraction buffer was in favor of ShTRAIL’s trimerization (Fig. 5.A), whereas utilizing the phosphate extraction buffer led to ShTRAIL dimmer formation (Fig. 5.B). Furthermore, regarding cross linking assay of ascorbate buffer extracted ShTRAIL, the trimerization state of the ER sorted ShTRAIL system was higher than the cytoplasmic expressed one (Fig. 5.A). However, concerning cross linking assay of phosphate buffer extracted ShTRAIL, there was a similar pattern of monomer and dimmer ShTRAIL bands in both ER sorted and cytoplasmic expression systems (Fig. 5.B).

Fig. 5 .

Cross linking assay and western blot analysis of ShTRAIL obtained from different transformed N. tabacum callus cells. Panel A) demonstrate ascorbate buffer extracted western blot analysis of glutaraldehyde mediated cross linked protein from transformed N. tabacum callus cells. Lane 1 represents cytoplasmic and Lane 2 represents reticulum endoplasmic expressed ShTRAIL. Panel B) demonstrates phosphate buffer extracted western blot analysis of glutaraldehyde mediated cross linked protein from transformed N. tabacum callus cells. Lane 1 represents cytoplasmic and Lane 2 represents reticulum endoplasmic expressed ShTRAIL.

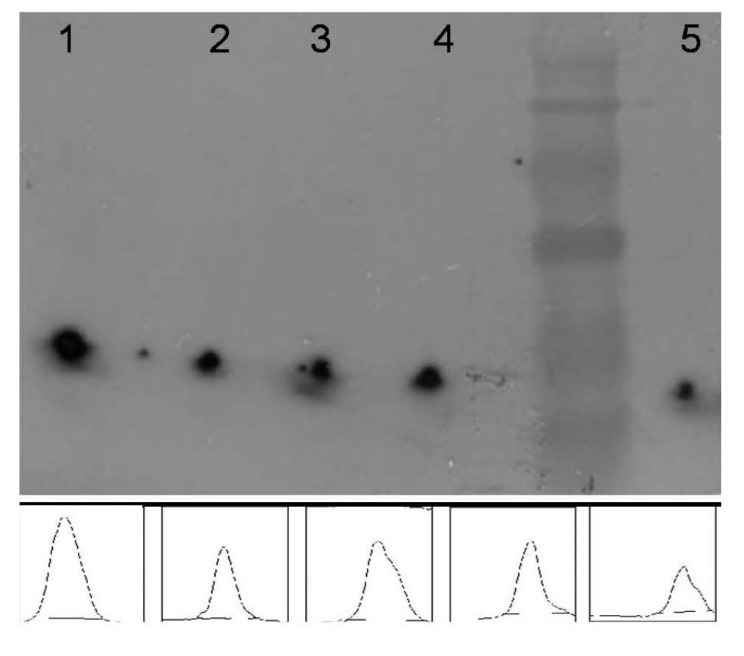

Semi-quantitative western blot analysis

To examine the implication of the ER targeting expression system on the stability and the production level of ShTRAIL in N. tabacum, chemiluminescence based semi-quantitative western blot analysis was performed (Fig. 6). The relative expression level of cytoplasmic and ER sorted ShTRAIL are presented in Table 2. Semi-quantitative western blot analysis on the ascorbate protein extract of the eighth week screened transformed N. tabacum cells implied that there was not considerable differences between cytoplasmic versus ER sorted expression systems (Fig. 6, Table 2). However, densitometry analysis of the twelfth week screened transformed N. tabacum cells suggested that the ER-sorted-ShTRAIL was more stable than the cytoplasmic one. Furthermore, the proportion of the ER-sorted-ShTRAIL in twelfth week screened transformed cells was higher than the eighth week counterpart (Fig. 6, Table 2).

Fig. 6 .

Estimation of N. tabacum produced ShTRAIL by semi-quantitative western blot analysis. Western blot analysis of 200 μg from ascorbate buffer mediated protein extracts of the twelfth week screened (Lanes 1 and 2) and the eighth week screened (Lanes 3 and 4) transformed N. tabacum cells beside 100 ng of recombinant TRAIL (Lane 5) as standard. Lanes 1 and 3 represent endoplasmic expressed ShTRAIL and Lanes 2 and 4 represent cytoplasmic expressed ShTRAIL.

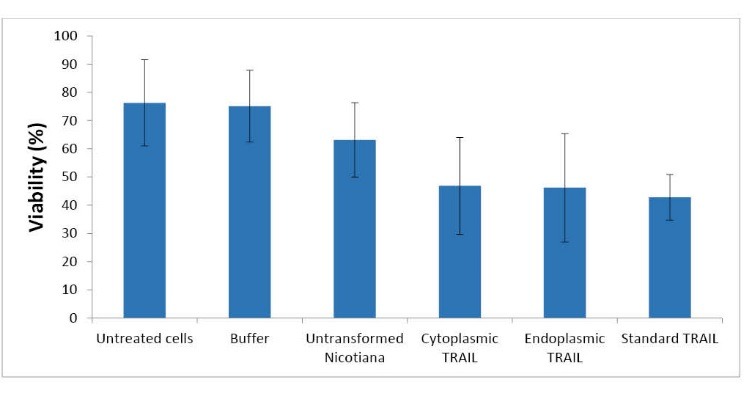

Biological assay

To evaluate the biological activity of N. tabacum produced ShTRAIL, cell proliferation inhibition MTT assay was performed on A549 cell line. Both cytoplasmic and endoplasmic expressed ShTRAIL had significant antiproliferative effect on the A549 cell line in comparison with the negative controls at 24 h after the treatment (Fig. 7). Through employing a total of 200 μg ascorbate extracted crude protein (corresponded to about 400 ng recombinant ShTRAIL) of both cytoplasmic and endoplasmic expressed ShTRAILs, the viability of the A549 cell line decreased to approximately 40-50%. However, neither ascorbate extracted crude protein of untransformed N. tabacum cells, nor treatment buffer showed significant activity on the A549 proliferation rate (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7 .

Evaluation of biological activity of N. tabacum expressed ShTRAIL by MTT assay. MTT assay of a 200 μg from ascorbate buffer mediated total protein extracts of untransformed N. tabacum (as negative control), and transformed N. tabacum cells (cytoplasmic expressed ShTRAIL and endoplasmic reticulum expressed ShTRAIL), besides standard TRAIL as positive control and buffer as negative controls. “*” indicates significant differences (p< 0.05).

Discussion

A variety of strategies have been utilized to improve recombinant gene expression, accumulation and purification in the transgenic plants.4,11 Accordingly, in this study improving the expression of the biologically active “Soluble human TRAIL” via the endoplasmic reticulum production in N. tabacum cells was tackled. Initially, powerful CaMV-35S plant promoter, powerful TMV omega leader sequence, ER sorting signal peptides, and hygromycin selectable marker were employed through subsequent cloning steps. Afterward, to extract and purify the ShTRAIL from transformed N. tabacum cells, the optimized phosphate extraction buffer and the innovative ascorbate extraction buffer were utilized. The protein assay results indicated that both the optimized phosphate extraction buffer and the innovative ascorbate extraction buffer could extract higher amounts of protein than commercial PBS based extraction buffer which was utilized in our last experiments (1.6 mg/milt vs. 1.4 mg/milt).31

The results of “total protein extraction” and “silver-stained SDS-PAGE” analyses indicated that both phosphate and ascorbate buffers could extract the ShTRAIL recombinant N. tabacum proteins with somewhat similar pattern. However, some differences between these extraction patterns may attribute to diverse pI of N. tabacum proteins and their different solubility in the pH of extraction (5 vs. 7.85). Although, the phosphate extraction buffer could slightly solubilize the higher amount of N. tabacum proteins than the ascorbate buffer, the phosphate buffer extracted proteins were subjected to phenolic compounds mediated instabilities. Indeed, plants phenolic compounds interact either covalently (cross-linking reactions) or non-covalently (especially hydrophobic interaction) with extracted proteins and increase the susceptibility of protein aggregation and precipitation.37,38 Moreover, plant phenolic compounds can be oxidized either enzymically (e.g., by polyphenoloxidases) or non-enzymically (in alkaline condition) to produce reactive quinines which can initiate oxidizing cascade reactions (browning reactions).39-43 Consequently, to minimize the browning reaction, the innovative ascorbate buffer was exploited. The Ascorbic acid-Ascorbate buffer by providing both acidic pH and anti-oxidizing properties restrains phenolic compounds from the browning reactions.44,45 Therefore, minimal protein precipitations occurred during ShTRAIL extraction procedure. Furthermore, regarding the pI of ShTRAIL (pI: 9), the pH of ascorbate buffer (pH: 5) is in favor of ShTRAIL’s solubilization and extraction than the pH of phosphate buffer (pH: 7.85).

However, regarding the silver stained SDS-PAGE analysis, there were not any intense obvious ShTRAIL bands neither in the phosphate nor in the ascorbate buffer extracted proteins of both types of expression systems. This lack of intense band of recombinant TRAIL may be attributed to the low expression level of plant expression systems. Therefore, western blot analysis was performed to evaluate the benefits of employing the expression systems and the extraction methods.

The results of cross-linking assay implied that although both cytoplasmic and ER sorted production systems had the capability to generate trimer TRAIL, the proportion of trimer to monomer in the ER targeted expression system was higher than that in the cytoplasmic counterpart. This higher capability may refer to the aid of abundant ER chaperons in proper folding and assembly of multimeric proteins.46-48

However, as cross-linking results indicated, it seems that the proper selection of the extraction buffer plays the main role in ShTRAIL trimerization outcome. While employing the ascorbate extraction buffer was in favor of TRAIL trimerization, utilizing the phosphate extraction buffer, as in our past experiment, led to TRAIL dimmer formation.31 Actually, these differences arise from the availability of reduced Cys230 on TRAIL structure. As Bodmer et al indicated,49 TRAIL trimerization depends on the suitable chelation of zinc ion by reduced Cys230 on TRAIL structure. As a result, inter-chain disulfide bridge formation between TRAIL’s Cys230 counterparts prohibits TRAIL trimerization. Correspondingly, it seems that antioxidant property of ascorbate buffer diminished the oxidizing features of the extraction environment, and disulfide bond formation between TRAIL monomers was prevented. Therefore, through employing ER targeted expression strategy and exploiting proper ascorbate buffer extraction, the higher amount of trimer ShTRAIL can be attained. However, further care should be exercised about employment of ascorbate buffer in neutral or alkaline pH, high temperatures, and in the presence of divalent cations regarding probable Maillard reaction of ascorbate with proteins.50,51

Similarly, according to the results of the semi-quantitative western blot analysis, ER sorted expression strategy increased the stability and overall production level of the ShTRAIL. Probably the improvement in the ShTRAIL production level was more attributed to the stability rather than translation improvement. Since, as semi-quantitative western blot analysis of the eighth week screened N. tabacum cells indicated utilizing omega sequence of TMV (in H2 cassette) did not significantly enhance the TRAIL production level in comparison with plant optimized Kozak sequence (in cytoplasmic expression system). It is very likely that through employing strong 35S-CaMV promoter and elevated transcription level, there was no significant difference between “TMV omega sequence” and “optimized Kozak sequence” in TRAIL’s translational level. However, as semi-quantitative western blot analysis of the twelfth week screened N. tabacum cells indicated, ER sorted ShTRAIL was more stable than the cytoplasmic expressed one. Probably the cytoplasmic expressed ShTRAIL proteins were subjected to proteolysis through the proteasome machinery activity of the N. tabacum, whereas the resident ER ShTRAIL proteins were relatively protected from proteolytic degradation. These data are in agreement with the recent reports regarding the employment of ER targeted expression system in increasing the recombinant protein production level in plant expression systems.52-54

Regarding the MTT assay results, both cytoplasmic and endoplasmic reticulum expressed ShTRAILs could successfully inhibit the proliferation of the A549 cell line. Furthermore, there was not a significant difference between biological activities of the cytoplasmic or endoplasmic reticulum expressed ShTRAILs. These results may be attributed to the capability of both expression systems on functional trimer ShTRAIL production. However, this antiproliferative activity of the N. tabacum produced ShTRAIL was only detectable through employing the ascorbate buffer extraction procedure which yielded the trimer ShTRAIL. As our previous study indicated, employing phosphate buffer for extraction of ShTRAIL from recombinant N. tabacum yielded non-functional dimmer TRAIL.31 Therefore, overcoming oxidative environment of N. tabacum extract is essential for the functional extraction of the oxidization sensitive ShTRAIL.

Conclusion

Employment of endoplasmic reticulum expression strategy could increase the stability and overall production level of the ShTRAIL up to about a 20 μg/g of fresh weight of N. tabacum. However, functional trimer extraction of ShTRAIL from oxidative environment of N. tabacum required utilizing the reductive and anti-oxidative extraction buffer.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Ahmad Yari Khosroushahi and Dr Ghanati for all their supports during this study. This article is extracted from Hamid Reza Heidari PhD thesis and was supported by research affair of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (grant No. 6735).

Ethical issues

There is none to be declared.

Competing interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Melnik S, Stoger E. Green factories for biopharmaceuticals. Curr Med Chem. 2013;20:1038–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Basaran P, Rodriguez-Cerezo E. Plant molecular farming: opportunities and challenges. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2008;28:153–72. doi: 10.1080/07388550802046624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Obembe OO, Popoola JO, Leelavathi S, Reddy SV. Advances in plant molecular farming. Biotechnol Adv. 2011;29:210–22. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Streatfield SJ. Approaches to achieve high-level heterologous protein production in plants. Plant Biotechnol J. 2007;5:2–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2006.00216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Datla R, Anderson JW, Selvaraj G. Plant promoters for transgene expression. In: El-Gewely MR, editor. Biotechnology Annual Review. Elsevier; 1997. p. 269-96.

- 6.Corrado G, Karali M. Inducible gene expression systems and plant biotechnology. Biotechnol Adv. 2009;27:733–43. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moore I, Samalova M, Kurup S. Transactivated and chemically inducible gene expression in plants. Plant J. 2006;45:651–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sugio T, Satoh J, Matsuura H, Shinmyo A, Kato K. The 5ˊ-untranslated region of the Oryza sativa alcohol dehydrogenase gene functions as a translational enhancer in monocotyledonous plant cells. J Biosci Bioeng. 2008;105:300–2. doi: 10.1263/jbb.105.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hiwasa-Tanase K, Nyarubona M, Hirai T, Kato K, Ichikawa T, Ezura H. High-level accumulation of recombinant miraculin protein in transgenic tomatoes expressing a synthetic miraculin gene with optimized codon usage terminated by the native miraculin terminator. Plant Cell Rep. 2011;30:113–24. doi: 10.1007/s00299-010-0949-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ortega JL, Moguel-Esponda S, Potenza C, Conklin CF, Quintana A, Sengupta-Gopalan C. The 3ˊ untranslated region of a soybean cytosolic glutamine synthetase (GS1) affects transcript stability and protein accumulation in transgenic alfalfa. Plant J. 2006;45:832–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02644.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jamal A, Ko K, Kim H-S, Choo Y-K, Joung H, Ko K. Role of genetic factors and environmental conditions in recombinant protein production for molecular farming. Biotechnology Advances. 2009;27:914–23. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arun M, Subramanyam K, Theboral J, Sivanandhan G, Rajesh M, Kapil Dev G. et al. Transfer and Targeted Overexpression of gamma-Tocopherol Methyltransferase (gamma-TMT) Gene Using Seed-Specific Promoter Improves Tocopherol Composition in Indian Soybean Cultivars. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2014;172:1763–76. doi: 10.1007/s12010-013-0645-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lindh I, Wallin A, Kalbina I, Savenstrand H, Engstram P, Andersson S. et al. Production of the p24 capsid protein from HIV-1 subtype C in Arabidopsis thaliana and Daucus carota using an endoplasmic reticulum-directing SEKDEL sequence in protein expression constructs. Protein Expr Purif. 2009;66:46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2008.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fletcher SP, Muto M, Mayfield SP. Optimization of recombinant protein expression in the chloroplasts of green algae. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;616:90–8. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-75532-8_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumari A, Sharma G, Bhat S, Bhat RS, Krishnaraj PU, Kuruvinashetti MS. Enhancement of Trichoderma endochitinase secretion in tobacco cell cultures using an alpha-amylase signal peptide. Plant Cell Tissue and Organ Culture. 2011;107:215–24. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lison P, Rodrigo I, Conejero V. A novel function for the cathepsin D inhibitor in tomato. Plant Physiol. 2006;142:1329–39. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.086587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Obregon P, Chargelegue D, Drake PM, Prada A, Nuttall J, Frigerio L. et al. HIV-1 p24-immunoglobulin fusion molecule: a new strategy for plant-based protein production. Plant Biotechnol J. 2006;4:195–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2005.00171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benchabane M, Goulet C, Rivard D, Faye L, Gomord V, Michaud D. Preventing unintended proteolysis in plant protein biofactories. Plant Biotechnol J. 2008;6:633–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2008.00344.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doran PM. Foreign protein degradation and instability in plants and plant tissue cultures. Trends Biotechnol. 2006;24:426–32. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2006.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chowdhury K, Bagasra O. An edible vaccine for malaria using transgenic tomatoes of varying sizes, shapes and colors to carry different antigens. Med Hypotheses. 2007;68:22–30. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2006.04.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaneko S, Kobayashi H. Purification and characterization of extracellular beta-galactosidase secreted by supension cultured rice (Oryza sativa L) cells. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2003;67:627–30. doi: 10.1271/bbb.67.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhatla SC, Kaushik V, Yadav MK. Use of oil bodies and oleosins in recombinant protein production and other biotechnological applications. Biotechnol Adv. 2010;28:293–300. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Platis D, Labrou NE. Affinity chromatography for the purification of therapeutic proteins from transgenic maize using immobilized histamine. J Sep Sci. 2008;31:636–45. doi: 10.1002/jssc.200700481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tian L, Sun SS. A cost-effective ELP-intein coupling system for recombinant protein purification from plant production platform. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24183. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fu H, Machado P, Hahm T, Kratochvil R, Wei C, Lo Y. Recovery of nicotine-free proteins from tobacco leaves using phosphate buffer system under controlled conditions. Bioresour Technol. 2010;101:2034–42. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2009.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cretney E, Shanker A, Yagita H, Smyth MJ, Sayers TJ. TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand as a therapeutic agent in autoimmunity and cancer. Immunol Cell Biol. 2006;84:87–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1711.2005.01413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fan QL, Wei W, Zou WY, Song LH. Cloning expression purification and cytotoxic assay of sTRAIL in A549 cell line. Zhongguo Yaolixue Tongbao. 2006;22:228–33. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Y, Wan L, Yang H, Liu S, Cai H, Lu X. Cloning and recombinant expression of human soluble TRAIL in Pichia pastoris. Sheng Wu Yi Xue Gong Cheng Xue Za Zhi. 2010;27:1307–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang D, Shi L. High-Level Expression, Purification, and In Vitro Refolding of Soluble Tumor Necrosis Factor-Related Apoptosis-Inducing Ligand (TRAIL) Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2009;157:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s12010-007-8079-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang D, Bai X, Liu Q, Zhu Y, Bai Y, Wang Y. Expression of human soluble tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-related apoptosis-inducing ligand in transplastomic tobacco. African Journal of Biotechnology. 2011;10:6816–23. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Heidari HR, Bandehpour M, Vahidi H, Barar J, Naderimanesh H, Kazemi B. Cloning and expression of TNF related apoptosis inducing ligand in Nicotiana tabacum. Iranian Journal of Pharmaceutical Researches 2014; In press. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Chen H, Nelson R, Sherwood J. Enhanced recovery of transformants of Agrobacterium tumefaciens after freeze-thaw transformation and drug selection. Biotechniques. 1994;16:664–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marton L, Wullems G, Molendijk L, Schilperoort R. In vitro transformation of cultured cells from Nicotiana tabacum by Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Nature. 1979;277:129–131. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shevchenko A, Wilm M, Vorm O, Mann M. Mass spectrometric sequencing of proteins silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. Anal Chem. 1996;68:850–8. doi: 10.1021/ac950914h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mischke R, Kleemann R, Brunner H, Bernhagen J. Cross-linking and mutational analysis of the oligomerization state of the cytokine macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) FEBS Lett. 1998;427:85–90. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00400-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crowell AM, Wall MJ, Doucette AA. Maximizing recovery of water-soluble proteins through acetone precipitation. Anal Chim Acta. 2013;796:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Charlton AJ, Baxter NJ, Khan ML, Moir AJ, Haslam E, Davies AP. et al. Polyphenol/peptide binding and precipitation. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50:1593–601. doi: 10.1021/jf010897z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baxter NJ, Lilley TH, Haslam E, Williamson MP. Multiple interactions between polyphenols and a salivary proline-rich protein repeat result in complexation and precipitation. Biochemistry. 1997;36:5566–77. doi: 10.1021/bi9700328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mishra BB, Gautam S, Sharma A. Free phenolics and polyphenol oxidase (PPO): the factors affecting post-cut browning in eggplant (Solanum melongena) Food Chem. 2013;139:105–14. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.01.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ciou JY, Lin HH, Chiang PY, Wang CC, Charles AL. The role of polyphenol oxidase and peroxidase in the browning of water caltrop pericarp during heat treatment. Food Chem. 2011;127:523–7. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chisari M, Barbagallo RN, Spagna G. Characterization and role of polyphenol oxidase and peroxidase in browning of fresh-cut melon. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56:132–8. doi: 10.1021/jf0721491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spagna G, Barbagallo RN, Chisari M, Branca F. Characterization of a tomato polyphenol oxidase and its role in browning and lycopene content. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:2032–8. doi: 10.1021/jf040336i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hisaminato H, Murata M, Homma S. Relationship between the enzymatic browning and phenylalanine ammonia-lyase activity of cut lettuce, and the prevention of browning by inhibitors of polyphenol biosynthesis. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2001;65:1016–21. doi: 10.1271/bbb.65.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Landi M, Degl’Innocenti E, Guglielminetti L, Guidi L. Role of ascorbic acid in the inhibition of polyphenol oxidase and the prevention of browning in different browning-sensitive Lactuca sativa varcapitata (L) and Eruca sativa (Mill) stored as fresh-cut produce. J Sci Food Agric. 2013;93:1814–9. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.5969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arias E, Gonzalez J, Peiro JM, Oria R, Lopez-Buesa P. Browning prevention by ascorbic acid and 4-hexylresorcinol: different mechanisms of action on polyphenol oxidase in the presence and in the absence of substrates. J Food Sci. 2007;72:C464–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2007.00514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arrigo AP. [Heat shock proteins as molecular chaperones] Med Sci (Paris) 2005;21:619–25. doi: 10.1051/medsci/2005216-7619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gething MJ, Sambrook J. Transport and assembly processes in the endoplasmic reticulum. Semin Cell Biol. 1990;1:65–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang Y, Williams DB. Assembly of MHC class I molecules within the endoplasmic reticulum. Immunol Res. 2006;35:151–62. doi: 10.1385/IR:35:1:151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bodmer JL, Meier P, Tschopp J, Schneider P. Cysteine 230 is essential for the structure and activity of the cytotoxic ligand TRAIL. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:20632–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M909721199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reihl O, Lederer MO, Schwack W. Characterization and detection of lysine-arginine cross-links derived from dehydroascorbic acid. Carbohydr Res. 2004;339:483–91. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Grandhee SK, Monnier VM. Mechanism of formation of the Maillard protein cross-link pentosidineGlucose, fructose, and ascorbate as pentosidine precursors. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:11649–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goojani HG, Javaran MJ, Nasiri J, Goojani EG, Alizadeh H. Expression and large-scale production of human tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA) in transgenic tobacco plants using different signal peptides. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2013;169:1940–51. doi: 10.1007/s12010-013-0115-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Juarez P, Huet-Trujillo E, Sarrion-Perdigones A, Falconi EE, Granell A, Orzaez D. Combinatorial Analysis of Secretory Immunoglobulin A (sIgA) Expression in Plants. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:6205–22. doi: 10.3390/ijms14036205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee JH, Park DY, Lee KJ, Kim YK, So YK, Ryu JS. et al. Intracellular reprogramming of expression, glycosylation, and function of a plant-derived antiviral therapeutic monoclonal antibody. PLoS One. 2013;8:e68772. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]