Abstract

Introduction: The main objective of this study was preparation and characterization of solid dispersion of piroxicam to enhance its dissolution rate.

Methods: Solid dispersion formulations with different carriers including crospovidone, microcrystalline cellulose, Elaeagnus angustifolia fruit powder, with different drug to carrier ratios were prepared employing cogrinding method. Dissolution study of the piroxicam powders, physical mixtures and solid dispersions was performed in simulated gastric fluid and simulated intestinal fluid using USP Apparatus type II. The physical characterization of formulations were analyzed using powder X ray diffraction (PXRD), particle size analyzer and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC). Interactions between the drug and carriers were evaluated by Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopic method.

Results: It was revealed that all of three carriers increase the dissolution rate of piroxicam from physical mixtures and especially in solid dispersions compared to piroxicam pure and treated powders. PXRD and DSC results confirmed the reduction of crystalline form of piroxicam. FT-IR analysis did not show any physicochemical interaction between drug and carriers in the solid dispersion formulations.

Conclusion: Dissolution rate was dependent on the type and ratio of drug to carrier as well as pH of dissolution medium. Dissolution data of formulations were fitted well into the linear Weibull as well as non-linear logistic and suggested models.

Keywords: Piroxicam, Solid dispersion, Dissolution rate, Cogrinding

Introduction

The rate or extent of dissolution of drug from any solid dosage form is a rate limiting step in the poor process of water soluble drug absorption. Potential absorption problem is due to erratic and incomplete absorption from gastrointestinal tract and occurs if the aqueous solubility is less than 1mg/mL. Therefore, for better and quick absorption, dissolution rate enhancement is critical.1,2

Several techniques have been developed to enhance the solubility and overcome the problems associated with poorly water soluble drugs such as solid dispersion, inclusion complex, ultra rapid freezing process, melt sono crystallization, solvent change method, melt granulation technique, supercritical solvent, supercritical and cryogenic technique, micronization, cosolvent approach, salt formation, use of surfactant and use of pro-drug.3-8

Solid dispersion technique has been widely used to increase the solubility of a poorly water soluble drug. Based on this method, a drug is utterly dispersed in a hydrophilic carrier by appropriate methods of preparation. The main mechanism for increasing the solubility and the dissolution rate of the drug is the included reduction of particle size of drug to submicron size or molecular size. The particle size reduction is attributed to increased wettability within the dispersions which generally increases the rate of dissolution. Furthermore, the drug is changed from amorphous to crystalline form, the high energetic state, which is highly soluble. At last, wettability of drug particle is improved by the hydrophilic carrier.1,9-12

Solid dispersion, which was introduced in the early 1970s, is basically a multicomponent system, having drug dispersed in and around hydrophilic carrier (s) and can be prepared by various methods such as solvent evaporation, cogrinding and melting method.13-17 A cogrinding technique has been employed to prepare the formulations. The method has some advantages over other techniques of solid dispersion formulations in that it does not require the use of toxic solvent therefore environmentally favorable and economically less expensive.18

Different hydrophilic carriers, such as polyethylene glycols, polyvinylpyrrolidone, hydroxypropyl methylcellulose, gelucires, poloxamers, gums, sugar, mannitol and urea have been examined for improvement of dissolution characteristics and bioavailability of poorly water soluble drugs.10,11,19-27

Piroxicam (PRX) is one of the most potent non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs which is employed in musculoskeletal and joint disorders such as ankylosing spondylitis, osteoarthritis, and rheumatoid arthritis. Based on the Biopharmaceutical Classification System, PRX belongs to the class II, characterized by low solubility. A brief review of literature showed that many different carriers and methods were used to formulate solid dispersion formulations of PRX. However, Elaeagnus angustifolia fruit powder was not used in the formulation of solid dispersions before our investigation in 2010.1,18,28-30, Considering the abundance of Elaeagnus angustifolia in vast areas of central and western Asia including Iran, the anti-nociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects could potentiate the effects of ibuprofen. The major constituents of oleaster powder are glucose and fructose (more than 55% w/w) which confer a high degree of hydrophilicity to it.18 In this study, solid dispersions were formulated with three water soluble polymers including microcrystalline cellulose (MCC), crospovidone and Elaeagnus angustifolia fruit powder by cogrinding technique.

Materials and methods

Materials

PRX was a gift from Zahravi Pharmaceutical Company (Iran). Microcrystalline cellulose (Avicel PH-101) and crospovidone were supplied from Blanver (Korea) and BASF (Germany) Companies, respectively. Elaeagnus angustifolia fruit (vernacular name is senjed which is native to central and western Asia including Iran) powder (Tabriz product, Iran) was used as received. HCl, NaOH and KH2PO4 were obtained from Merck Company (Germany).

Methods

Preparation of physical mixtures

To prepare physical mixtures of drug and carriers with different ratios (1:0.5, 1:1, 1:2, 1:5 and 1:10), the calculated amounts of PRX and carriers were weighed and mixed by tumbling method in a glass bottle.

Preparation of solid dispersions

Solid dispersions of PRX with different carriers were prepared by cogrinding method. Accurately weighed quantities (10 g) of PRX and the respective carrier were located into a Ball Mill (Fritsch, Germany). The mixtures were then rotated (rpm=360) at room temperature for 3 h at different angles mostly in 45 º.

Characterization of solid dispersion

Powder X-Ray Diffraction (PXRD) studies

The powder X-ray diffraction analysis was conducted for pure and treated drug, polymers, physical mixtures and solid dispersions. X-ray diffractograms were obtained using the Siemens (Germany) X- ray diffractometer with Cu-Kα (λ= 1.54 Å) radiation at 40 kV and 30 mA. All samples were scanned over a 2θ range of 30-80 ° at a step size of 0.02 °.

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)

Accurately weighed samples (pure PRX, treated PRX, carriers, physical mixtures and solid dispersions) were placed into the standard aluminum pans with lids. Subsequently, the physical status of PRX of the formulations was monitored using the differential scanning calorimetry (DSC60, Shimadzu, Japan). The heating rate was 20 ºC/min and the heat flow was recorded from 25 ºC to 250ºC. The aluminum oxide was used as reference.

Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopic analysis

FTIR spectra of the treated and pure powder of PRX and all carriers as well as physical mixtures and solid dispersions with drug to carrier ratio of 1:2 were obtained using a spectrophotometer (Bomem, USA) by potassium bromide (KBR, 150 bar) pellet method. The scanning range was 450–4000 cm−1, and the resolution was 4 cm−1.

Particle size analysis

The mean particle size and size distribution of the pure and treated powder of PRX were determined (n=3) using the laser diffraction particle size analyzer (Shimadzu, Japan) equipped with the Wing SALD software (version 2101).

In vitro release study

In vitro dissolution study was conducted using USP apparatus No. II (paddle method) in a speed of 100 rpm and a fixed amount of solid dispersions, physical mixtures and PRX powders (treated and nontreated) containing 20 mg equivalent of PRX. Nine hundred milliliters of simulated gastric fluid (SGF, pH 1.2) and simulated intestinal fluid (SIF, pH 6.8) at temperature of 37 ± 0.5 °C were used as dissolution media. The dissolution test was carried out for 60 min and 5 mL sample was withdrawn at predetermined intervals of 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 45 and 60 min. The dissolution samples were then analyzed by UV-VIS spectrophotometer (SHIMADZU, Japan) at λ max =234 nm (linear in the range of 2.5-20 µg/mL, R2= 0.9996 at pH 1.2 and R2= 0.9997 at pH 6.8).

Release kinetic analysis

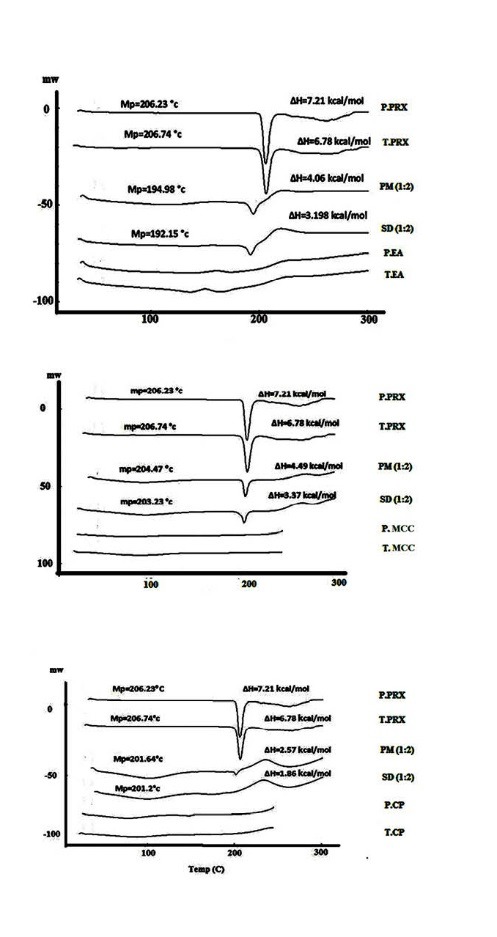

The release data obtained from in vitro dissolution studies were fitted to ten linear and seven non-linear kinetic equations to find out the best model of drug release (Table 1). The precision and prediction power of the models were evaluated by calculation of mean percent error (MPE) for each set as well as overall mean percent error (OMPE) for all sets using following equations:

Table 1 .

Mean squared correlation coefficients (MRSQ), mean percent error (MPE) and percent of total number of error (NE) of the kinetic models used for analysis of drug release data. F denotes fraction of drug released up to time t. k0, kf, kH, p, kP, k1/3, k1/2, k2/3, td, β, Z0, Z0’, q, q’, a and b are parameters of the models. Z and Z’ are probits of fraction of drug released at any time. Z0 and Z0’ are the values of Z and Z’ when t=0 and t=1 respectively. *See reference 31

| (1) |

Where Fobs and Fcal are the measured and calculated fraction of the drug released in each sampling time, and N is the number of sampling times.2,31

| (2) |

Where, 32 is the number of formulations.

Dissolution profile of different formulations were compared using calculation of mean percent dissolution (MPD) and time needed to release 50% of incorporated drug (t50%) in pH 1.2 and 6.8.

MPD was calculated according to the following equation:23,32

| (3) |

Where D is the percent of drug dissolved at different sampling times.

Results

Characterization of the solid dispersions

Particle size analysis

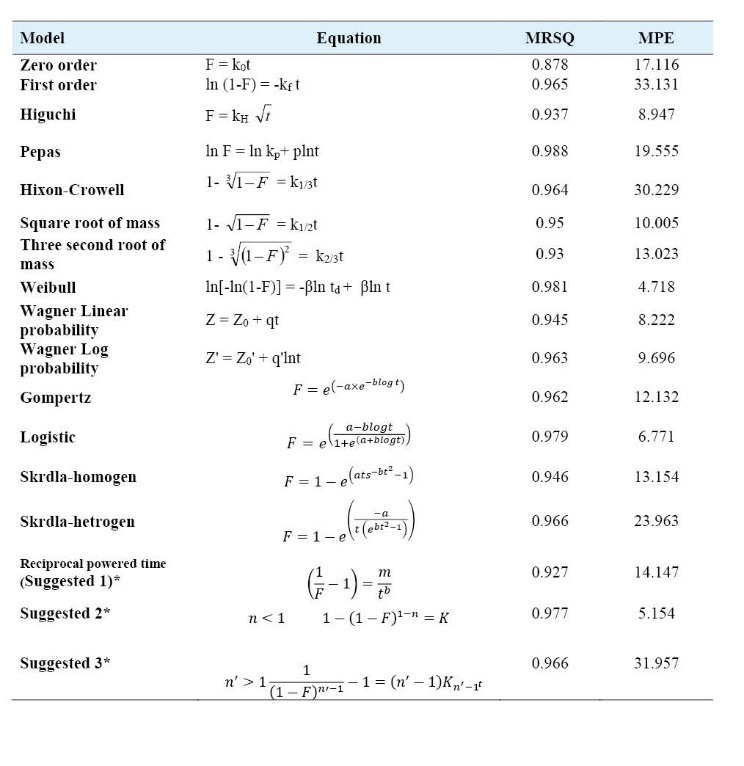

The particle size analysis results indicated that the mean particle size diameter of treated PRX powder was significantly (p<0.05) lower than pure drug (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 .

Particle size distribution of pure (Top) and treated PRX powder (Below)

Powder X-Ray Diffraction studies

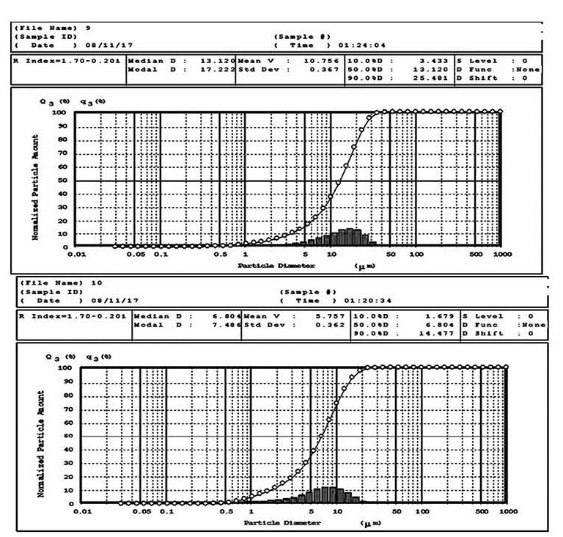

PXRD spectrum of pure PRX showed distinctive peaks in the 2θ= 8.99, 14.46, 17.67, 21.83 and 27.36 which indicate the crystalline form β of PRX (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 .

Powder X-Ray Diffraction patterns of pure PRX (P. PRX), treated FZM (T. PRX), physical mixtures (PM) 1:2, solid dispersions (SD) 1:2, pure microcrystalline cellulose (P. MCC) and treated microcrystalline cellulose (T. MCC), pure crospovidone (P.CP), treated crospovidone (T.CP), pure Elaeagnus angostifolia (P.EA) and treated Elaeagnus angostifolia (T.EA)

Differential Scanning Calorimetry

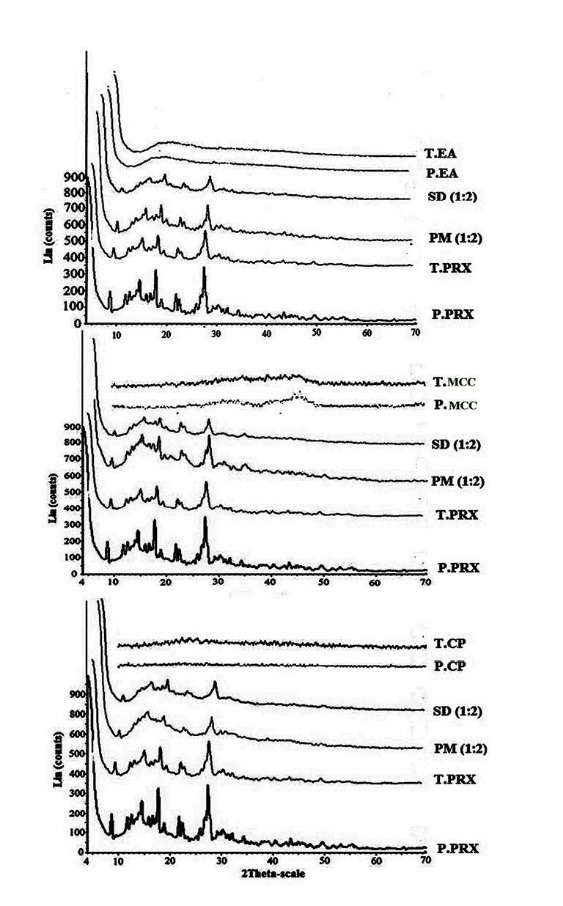

Differential scanning calorimetry pattern displayed a sharp endothermic peak at 206 ºC, corresponding to the melting point of PRX (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 .

DSC thermogram of pure PRX (P. PRX), treated FZM (T. PRX), physical mixtures (PM) 1:2, solid dispersions (SD) 1:2, pure microcrystalline cellulose (P. MCC) and treated microcrystalline cellulose (T. MCC), pure crospovidone (P.CP), treated crospovidone (T.CP), pure Elaeagnus angostifolia (P.EA) and treated Elaeagnus angostifolia (T.EA)

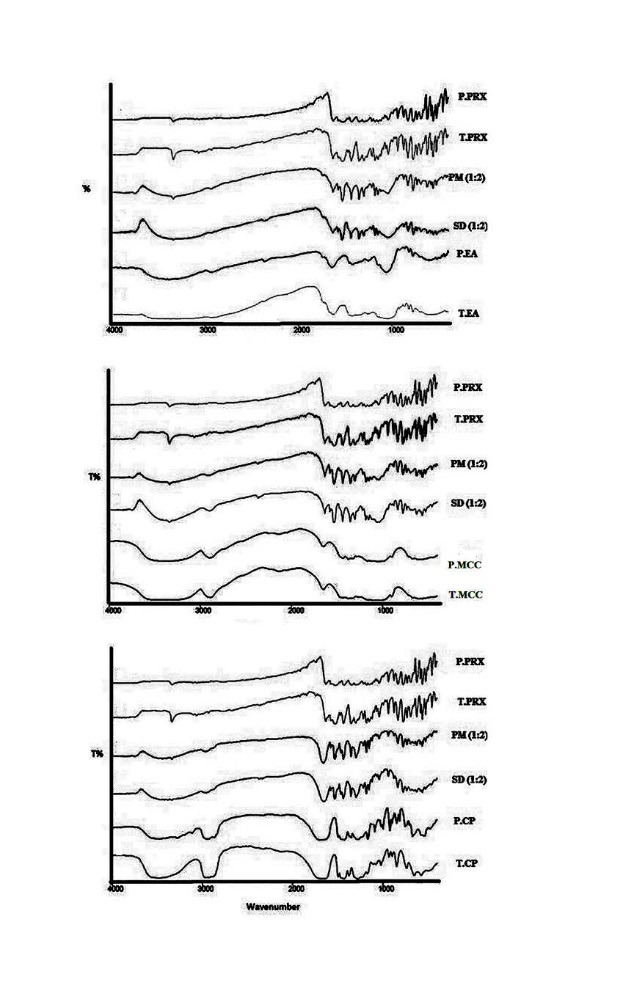

Fourier Transform Infrared spectroscopy

The FTIR studies were performed in order to find out the probable intermolecular interactions between the drug and carriers. The FTIR spectroscopy pattern of pure and treated PRX and carriers, as well as physical mixtures and solid dispersions (drug: carrier, 1:2) are presented in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4 .

FT-IR patterns of pure PRX (P. PRX), treated FZM (T. PRX), physical mixtures (PM) 1:2, solid dispersions (SD) 1:2, pure microcrystalline cellulose (P. MCC) and treated microcrystalline cellulose (T. MCC), pure crospovidone (P.CP), treated crospovidone (T.CP), pure Elaeagnus angostifolia (P.EA) and treated Elaeagnus angostifolia (T.EA)

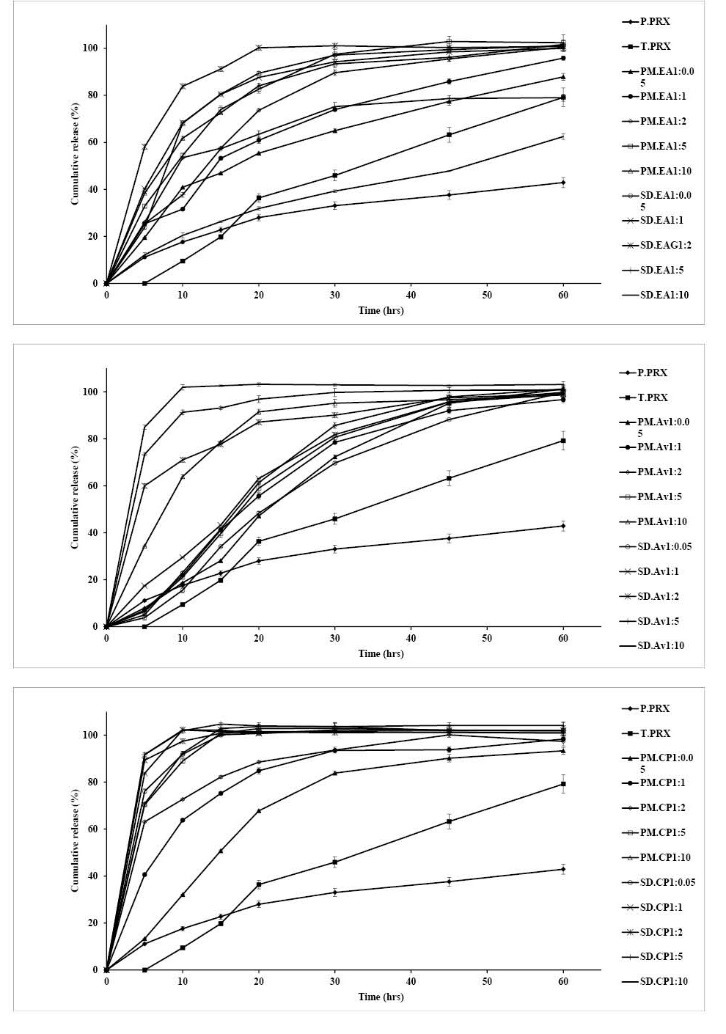

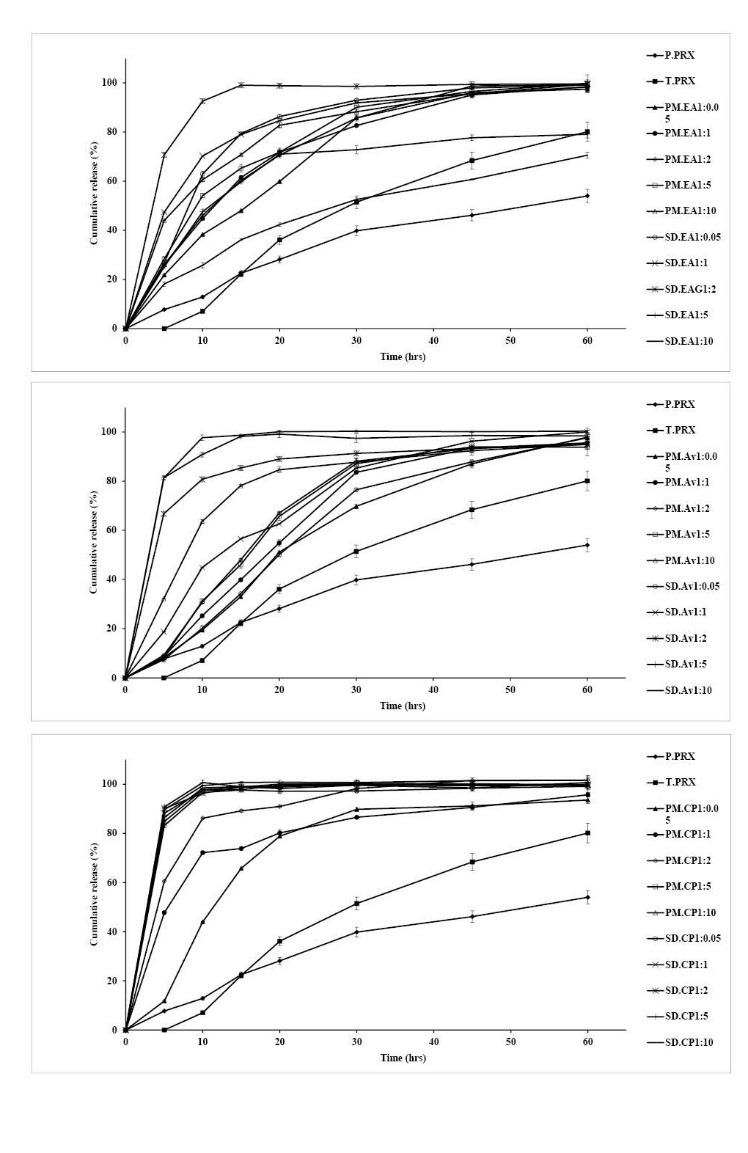

In vitro drug release

Dissolution profiles of physical mixtures and solid dispersions of PRX prepared with various drug to carrier ratios as well as treated and pure PRX powders at pH 1.2 and 6.8 are presented in Fig. 5 and 6, respectively. Dissolution rate of all physical mixtures were much higher than the pure PRX which may be because of high hydrophilicity of the polymers. Table 2 illustrates the time needed to release 50% of incorporated drug and the mean percent of dissolution from pure and treated PRX as well as physical mixtures and solid dispersions of PRX. Dissolution rate is considered faster, when the value of t50% is lower and MPD value is higher. In solid dispersions, drug release rate was enhanced as a consequence of increasing carrier concentration up to ratio of 1:2, while MCC containing solid dispersions showed the maximum release rate at the drug to carrier ratio of 1:2 (Table 2 and Fig. 5).

Fig. 5 .

Dissolution profiles of pure PRX (P. PRX), treated PRX (T. PRX) physical mixtures (PM) 1:2 and solid dispersions (SD) 1:1 containing microcrystalline cellulose (MCC), crospovidone (CP) and Elaeagnus angostifolia (EA) fruit powder in pH 1.2. (mean ± SD, n=3)

Fig. 6 .

Dissolution profiles of pure PRX (P. PRX), treated PRX (T. PRX) physical mixtures (PM) 1:2 and solid dispersions (SD) 1:1 containing microcrystalline cellulose (MCC), crospovidone (CP) and Elaeagnus angostifolia (EA) fruit powder in pH 6.8. (mean ± SD, n=3)

Table 2 . Mean percent dissolution (MPD) and time needed to release 50% of incorporated drug (t50%) of formulations in pH 1.2 and 6.8.

| Formulation | pH 1.2 | pH 6.8 | |||

| MPD | t 50% | MPD | t 50% | ||

| P.PRX | 27.6 | 75 | 30.3 | 53 | |

| T.PRX | 48.9 | 24 | 51.2 | 24.2 | |

| Avicel | PM 1:0.5 | 41.2 | 22 | 51.9 | 20 |

| PM 1:1 | 49.4 | 18 | 57.3 | 18 | |

| PM 1:2 | 54.4 | 17 | 61.2 | 15 | |

| PM 1:5 | 57.5 | 16 | 60.9 | 14 | |

| PM 1:10 | 76.7 | 9 | 76.2 | 7 | |

| SD 1:0.5 | 42.8 | 20 | 53.4 | 20 | |

| SD 1:1 | 55.1 | 16 | 62.2 | 13.8 | |

| SD 1:2 | 80.6 | 5 | 85.9 | 3 | |

| SD 1:5 | 85.9 | 3 | 89.9 | 2 | |

| SD 1:10 | 84.9 | 2.8 | 70.2 | 2 | |

| Crospovidone | PM 1:0.5 | 61.6 | 15 | 67.8 | 11.5 |

| PM 1:1 | 76.3 | 9 | 71.57 | 5.5 | |

| PM 1:2 | 80 | 4 | 90.83 | 3 | |

| PM 1:5 | 79.7 | 4 | 90.37 | 3 | |

| PM 1:10 | 81.6 | 4 | 91.2 | 3 | |

| SD 1:0.5 | 68.2 | 4 | 73.94 | 2.8 | |

| SD 1:1 | 83.7 | 3 | 89.9 | 2.6 | |

| SD 1:2 | 92.6 | 3 | 93.2 | 2.8 | |

| SD 1:5 | 93 | 2.8 | 92.9 | 2.8 | |

| SD 1:10 | 91.7 | 2.5 | 90.8 | 2.8 | |

| Elaeagnus angostifolia | PM 1:0.5 | 56.2 | 17 | 64.26 | 15 |

| PM 1:1 | 61 | 15 | 68.9 | 11.8 | |

| PM 1:2 | 66 | 10 | 69.6 | 11 | |

| PM 1:5 | 68.3 | 9 | 73.7 | 9 | |

| PM 1:10 | 79 | 7.5 | 77.7 | 6 | |

| SD 1:0.5 | 71.8 | 8 | 80.5 | 6.5 | |

| SD 1:1 | 75.8 | 6.4 | 81.8 | 5 | |

| SD 1:2 | 78 | 4.5 | 86.2 | 3.5 | |

| SD 1:5 | 59.6 | 14 | 61.9 | 11 | |

| SD 1:10 | 34.3 | 47 | 43.7 | 28 | |

P=Pure, T=Treated, PM=Physical mixture, SD=Solid dispersion

Fig. 6 shows that the dissolution of PRX is remarkably influenced by pH of the dissolution media in the presence or absence of a carrier.

Solid dispersions prepared by crospovidone with ratios of 1:0.5 and 1:1 showed a higher dissolution rate compared to MCC and Elaeagnus angustifolia fruit powder. Increasing the ratios of crospovidone from 1:1, Elaeagnus angustifolia fruit powder from 2:2 and MCC from 1:5 did not result in further increasing in dissolution rate. Therefore the best ratios for drug to carriers were as follows: crospovidone; 1:1, EA; 1:2 and MCC; 1:5.

The percentage of drug released at pH 6.8 is obviously higher than the amount of drug dissolved at pH 1.2. This could be due to the better solubility of the weak acid PRX because of a greater ionization at higher pH values.

Release kinetics

The in vitro release data of prepared solid dispersions were fitted to 10 linear and 7 non-linear kinetic models to clarify the mechanism of drug release. Results are presented in Table 1.

Discussion

The treated powder had a reduced geometric diameter and as a result, a higher surface area than that of pure PRX. According to the Noyes–Whitney equation, the amount of solid drug per unit time, dM/dt, is related to the surface area of the solid (S).

| (4) |

Where D is the diffusion coefficient of the solute in solution, h stands for the thickness of the diffusion layer, Cs and C are the solubility and the concentration of the solute in the solution, respectively.1,2,24 Therefore, the main reason of higher dissolution rate of the treated PRX compared to pure PRX may be described by particle size reduction during grinding process.

The treated PRX showed a different PXRD pattern with lower crystallinity indicating the effect of grinding on crystallinity. Comparing peaks height in the physical mixtures (drug: carrier, 1:2) indicated a reduction in the magnitude of peaks due to the dilution effect of the carriers. Reduction in the height of peaks and absence of some major peaks seen in PXRD patterns of the solid dispersions containing MCC and Elaeagnus angustifolia powder indicated a decrease of PRX crystallinity in these formulations (Fig. 2). Conversely, the PXRD patterns of physical mixtures and solid dispersions containing crospovidone did not show any reduction in crystallinity.

The DSC spectrum of the treated PRX also exhibited endothermic melting peak at 206 ºC. The lower intensity of peaks in physical mixtures of carriers and PRX compared to the pure PRX, and reduction of molar melting enthalpy could be explained by lower amount of PRX in PMs and dissolving of PRX in melted carriers. The reduction of molar melting enthalpy value and melting point in DSC spectra of the solid dispersions indicated the lower crystallinity of PRX in the solid dispersions. These results together with PXRD results confirmed that the majority of crystalline PRX was altered to the amorphous state in the solid dispersions prepared with all carriers by cogrinding methods.

Absorption peaks of 3333 cm-1and 3338 cm-1inFTIR spectroscopy pattern are related to the OH and NH bond, respectively. Absence of any other new peaks in the physical mixture and solid dispersions, and lack of elimination of these peaks and change in the positions of the absorption bands pointed to the absence of any significant interaction between PRX and carriers during cogrinding process.

Hydrophilic polymers cause aggregation reduction, wettability improvement and local solubilization by the carrier in the diffusion layer and hence increasing the dissolution rate. Although a direct relationship between the amount of carrier and PRX dissolution rate was found, increasing the carrier ratio more than 1:5 did not significantly affect the dissolution rate of different physical mixtures. On the other hand, the solid dispersion particles with different drug to polymer ratios showed the higher drug release rate compared to the related physical mixtures and pure drug.

Both of model independent parameters verified that the release rate is faster from the solid dispersions.

Piroxicam occurs as a white crystalline solid, sparingly soluble in water, dilute acid, and a most organic solvent. It is slightly soluble in alcohol and in aqueous solutions. It exhibits a weakly acidic 4-hydroxy proton (pKa 5.1) and a weakly basic pyridyl nitrogen (pKa 1.8). The improved drug release rate could be attributed to the drug crystallinity reduction in the PRX solid dispersions prepared by MCC, crospovidone and Elaeagnus angustifolia fruit powder. The amorphous form of a drug has a higher thermodynamic activity than its crystalline form, resulting in the rapid dissolution of the drug. It is usually believed that a drug in a solid dispersion system commonly exists in an amorphous form. Furthermore, the reduced particle size and accordingly elevated surface area could elevate the dissolution rate of PRX in the solid dispersions.33-35 Plus latter evidences, increasing drug wettability and solubility besides deaggregation of the drug particles caused by the polymers could be the reasons for enhanced drug release rate from the solid dispersions.

The accuracy and prediction of the models were assessed by calculation of mean squared correlation coefficients (MRSQ) and mean percent error (MPE).2,18,31 With the MRSQ and MPE values in mind, release data of all the formulations were fitted best to the Weibull, suggested No.1 and logistic models with MPE values of 4.74, 5.15 and 6.77.

Conclusion

Solid dispersions of piroxicam were prepared with crospovidone, MCC and Elaeagnus angustifolia fruit powder with different ratios employing cogrinding method and characterized by PXRD, FT-IR spectroscopy, DSC, particle size analysis and in vitro dissolution tests. The solid state studies employing DSC and PXRD confirmed that solid dispersion of PRX with all carriers can decrease crystallinity or increase amorphousness of the drug. Results of FT-IR spectroscopy indicated the absence of any interaction between drug and carriers. Obtained solid dispersions had reduced size and were dissolved quickly in simulated gastric fluid and simulated intestinal fluid compared to the pure PRX, treated PRX and physical mixtures. The dissolution study results showed that solid dispersions can be beneficially applied to enhance the dissolution rate of the PRX. Furthermore, drug to carrier ratio, type of carriers and dissolution medium pH had the major roles in the dissolution rate in the solid dispersion. The maximum dissolution rate was obtained in the solid dispersions with drug to crospovidone ratio of 1:1, drug to Elaeagnus angustifolia fruit powder ratio of 1:2 and drug to MCC ratio of 1:5, where further increase of carriers did not increase the dissolution rate of PRX. Generally, solid dispersion formulations can increase the dissolution rate by several factors including the increasing of surface area, increase in drug wettability, prevention of drug aggregation, and creation of amorphous polymorph of the drug in the solid dispersions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Drug Applied Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran. This article is based on a thesis submitted for Pharm.D degree (No. 3450) in Faculty of Pharmacy, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran.

Ethical issues

There is none to be declared.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Adibkia K, Barzegar-Jalali M, Maheri-Esfanjani H, Ghanbarzadeh S, Shokri J, Sabzevari A. et al. Physicochemical characterization of naproxen solid dispersions prepared via spray drying technology. Powder Technology. 2013;246:448–55. doi: 10.1016/j.powtec.2013.05.044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adibkia K, Barzegar-Jalali M, Mohammadi G, Ebrahimnejhad H, Alaei-Beirami M. Effect of sodium alginate chain length and Ca2+and Al 3+on the release of diltiazem from matrices. Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2011;16:221–8. [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Zordi N, Moneghini M, Kikic I, Grassi M, Del Rio Castillo AE, Solinas D. et al. Applications of supercritical fluids to enhance the dissolution behaviors of Furosemide by generation of microparticles and solid dispersions. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2012;81:131–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moneghini M, Kikic I, Voinovich D, Perissutti B, Filipović-Grčić J. Processing of carbamazepine–PEG 4000 solid dispersions with supercritical carbon dioxide: preparation, characterisation, and in vitro dissolution. Int J Pharm. 2001;222:129–38. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5173(01)00711-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reverchon E, Adami R, Caputo G, De Marco I. Spherical microparticles production by supercritical antisolvent precipitation: Interpretation of results. J Supercrit Fluids. 2008;47:70–84. doi: 10.1016/j.supflu.2008.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rogers TL, Overhoff KA, Shah P, Santiago P, Yacaman MJ, Johnston KP. et al. Micronized powders of a poorly water soluble drug produced by a spray-freezing into liquid-emulsion process. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2003;55:161–72. doi: 10.1016/S0939-6411(02)00193-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sarkari M, Brown J, Chen X, Swinnea S, Williams Iii RO, Johnston KP. Enhanced drug dissolution using evaporative precipitation into aqueous solution. Int J Pharm. 2002;243:17–31. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5173(02)00072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vo CL, Park C, Lee BJ. Current trends and future perspectives of solid dispersions containing poorly water-soluble drugs. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2013;85:799–813. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2013.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barmpalexis P, Koutsidis I, Karavas E, Louka D, Papadimitriou SA, Bikiaris DN. Development of PVP/PEG mixtures as appropriate carriers for the preparation of drug solid dispersions by melt mixing technique and optimization of dissolution using artificial neural networks. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2013;85:1219–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2013.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karavas E, Georgarakis E, Sigalas MP, Avgoustakis K, Bikiaris D. Investigation of the release mechanism of a sparingly water-soluble drug from solid dispersions in hydrophilic carriers based on physical state of drug, particle size distribution and drug–polymer interactions. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2007;66:334–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2006.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paudel A, Worku ZA, Meeus J, Guns S, Van den Mooter G. Manufacturing of solid dispersions of poorly water soluble drugs by spray drying: Formulation and process considerations. Int J Pharm. 2013;453:253–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2012.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sjökvist E, Nyström C. Physicochemical aspects of drug release VI Drug dissolution rate from solid particulate dispersions and the importance of carrier and drug particle properties. Int J Pharm. 1988;47:51–66. doi: 10.1016/0378-5173(88)90215-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Broman E, Khoo C, Taylor LS. A comparison of alternative polymer excipients and processing methods for making solid dispersions of a poorly water soluble drug. Int J Pharm. 2001;222:139–51. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5173(01)00709-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cui F, Yang M, Jiang Y, Cun D, Lin W, Fan Y. et al. Design of sustained-release nitrendipine microspheres having solid dispersion structure by quasi-emulsion solvent diffusion method. J Control Release. 2003;91:375–84. doi: 10.1016/S0168-3659(03)00275-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joe JH, Lee WM, Park Y-J, Joe KH, Oh DH, Seo YG. et al. Effect of the solid-dispersion method on the solubility and crystalline property of tacrolimus. Int J Pharm. 2010;395:161–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2010.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim E-J, Chun M-K, Jang J-S, Lee I-H, Lee K-R, Choi H-K. Preparation of a solid dispersion of felodipine using a solvent wetting method. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2006;64:200–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zajc N, Obreza A, Bele M, Srčič S. Physical properties and dissolution behaviour of nifedipine/mannitol solid dispersions prepared by hot melt method. Int J Pharm. 2005;291:51–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2004.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mohammadi G, Barzegar-Jalali M, Valizadeh H, Nazemiyeh H, Barzegar-Jalali A, Siahi-Shadbad MR. et al. Reciprocal powered time model for release kinetic analysis of ibuprofen solid dispersions in oleaster powder, microcrystalline cellulose and crospovidone. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2010;13:152–61. doi: 10.18433/j3jg61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Hamidi H, Edwards AA, Mohammad MA, Nokhodchi A. To enhance dissolution rate of poorly water-soluble drugs: Glucosamine hydrochloride as a potential carrier in solid dispersion formulations. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces. 2010;76:170–8. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2009.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guns S, Kayaert P, Martens JA, Van Humbeeck J, Mathot V, Pijpers T. et al. Characterization of the copolymer poly(ethyleneglycol-g-vinylalcohol) as a potential carrier in the formulation of solid dispersions. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2010;74:239–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Papadimitriou SA, Barmpalexis P, Karavas E, Bikiaris DN. Optimizing the ability of PVP/PEG mixtures to be used as appropriate carriers for the preparation of drug solid dispersions by melt mixing technique using artificial neural networks: I. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2012;82:175–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watanabe T, Hasegawa S, Wakiyama N, Kusai A, Senna M. Comparison between polyvinylpyrrolidone and silica nanoparticles as carriers for indomethacin in a solid state dispersion. Int J Pharm. 2003;250:283–6. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5173(02)00549-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barzegar Jalali M, Dastmalchi S. Kinetic Analysis of Chlorpropamide Dissolution from Solid Dispersions. Drug Development and Industrial Pharmacy. 2007;33:63–70. doi: 10.1080/03639040600762636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mohammadi G, Barzegar-Jalali M, Siahi Shadbad MR, Azarmi S, Barzegar-Jalali A, Rasekhian M. et al. The effect of inorganic cations Ca2+ and Al3+ on the release rate of propranolol hydrochloride from sodium carboxymethylcellulose matrices. Daru. 2009;17:131. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barzegar-Jalali M, Adibkia K, Mohammadi G, Zeraati M, Bolagh B, Nokhodchi A. Propranolol hydrochloride osmotic capsule with controlled onset of release. Drug Deliv. 2007;14:461–8. doi: 10.1080/10717540701603639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barzegar-Jalali M, Nayebi A, Valizadeh H, Hanaee J, Barzegar-Jalali A, Adibkia K. et al. Evaluation of in vitro-in vivo correlation and anticonvulsive effect of carbamazepine after cogrinding with microcrystalline cellulose. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2006;9:307–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dastmalchi S, Garjani A, Maleki N, Sheikhee G, Baghchevan V, Jafari-Azad P. et al. Enhancing dissolution, serum concentrations and hypoglycemic effect of glibenclamide using solvent deposition technique. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2005;8:175–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aquino RP, Auriemma G, d’Amore M, D’Ursi AM, Mencherini T, Del Gaudio P. Piroxicam loaded alginate beads obtained by prilling/microwave tandem technique: Morphology and drug release. Carbohydr Polym. 2012;89:740–8. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rasetti-Escargueil C, Grangé V. Pharmacokinetic profiles of two tablet formulations of piroxicam. Int J Pharm. 2005;295:129–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shojaee SA, Rajaei H, Hezave AZ, Lashkarbolooki M, Esmaeilzadeh F. Experimental measurement and correlation for solubility of piroxicam (a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)) in supercritical carbon dioxide. J Supercrit Fluids. 2013;80:38–43. doi: 10.1016/j.supflu.2013.03.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barzegar-Jalali M, Adibkia K, Valizadeh H, Shadbad MRS, Nokhodchi A, Omidi Y. et al. Kinetic analysis of drug release from nanoparticles. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2008;11:167–77. doi: 10.18433/j3d59t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barzegar-Jalali M. A model for linearizing drug dissolution data. Int J Pharm. 1990;63:9–11. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guo Y, Shalaev E, Smith S. Physical stability of pharmaceutical formulations: solid-state characterization of amorphous dispersions. Trends Analyt Chem. 2013;49:137–44. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2013.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gurunath S, Pradeep Kumar S, Basavaraj NK, Patil PA. Amorphous solid dispersion method for improving oral bioavailability of poorly water-soluble drugs. J Pharm Res. 2013;6:476–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jopr.2013.04.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rumondor ACF, Taylor LS. Application of Partial Least-Squares (PLS) modeling in quantifying drug crystallinity in amorphous solid dispersions. Int J Pharm. 2010;398:155–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2010.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]