Abstract

Background/Aims

To compare the efficacy and safety of prucalopride, a novel selective high-affinity 5-hydroxytryptamine type 4 receptor agonist, versus placebo, in Asian and non-Asian women with chronic constipation (CC).

Methods

Data of patients with CC, receiving once-daily prucalopride 2-mg or placebo for 12-weeks, were pooled from 4 double-blind, randomized, phase-III trials (NCT00488137, NCT00483886, NCT00485940 and NCT01116206). The efficacy endpoints were: average of ≥ 3 spontaneous complete bowel movements (SCBMs)/week; average increases of ≥ 1 SCBMs/week; and change from baseline in each CC-associated symptom scores (bloating, abdominal pain, hard stool and straining).

Results

Overall, 1,596 women (Asian [26.6%], non-Asian [73.4%]) were included in this analysis. Significantly more patients in the prucalopride group versus placebo experienced an average of ≥ 3 SCBMs/week in Asian (34% vs. 11%, P < 0.001) and non-Asian (24.6% vs. 10.6%, P < 0.001) subgroups. The number of patients reporting an increase of ≥ 1 SCBMs/week from baseline was significantly higher in the prucalopride group versus placebo among both Asian (57.4% vs. 28.3%, P < 0.001) and non-Asian (45.3% vs. 24.0%, P < 0.001) subgroups. The difference between the subgroups was not statistically significant. Prucalopride significantly reduced the symptom scores for bloating, hard stool, and straining in both subgroups.

Conclusions

Prucalopride 2-mg once-daily treatment over 12-weeks was more efficacious than placebo in promoting SCBMs and improvement of CC-associated symptoms in Asian and non-Asian women, and was found to be safe and well-tolerated. There were numeric differences between Asian and non-Asian patients on efficacy and treatment emergent adverse events, which may be partially due to the overlap with functional gastrointestinal disorders in non-Asian patients.

Keywords: Asian women, Chronic constipation, Non-Asian women, Prucalopride, Serotonin 5-HT4 receptor agonists

Introduction

Chronic constipation (CC) is a common disorder with prevalence rates reported between 2% to 27% in the general population.1,2 In developed countries, prevalence estimates range from 10% to 15%.3,4 Consistent with the observations from Western populations, constipation in Asian populations is more prevalent in women and the elderly, especially among those over 65 years of age.5-8 Previously defined by health care providers, mainly in terms of the reduction in the frequency of bowel movements (BMs), CC is currently viewed as a symptom complex encompassing such complaints as straining, difficulty in passing stool, discomfort during defecation and feeling of incomplete evacuation,9 which are included in the Rome III diagnostic criteria for CC.10,11 The nature and severity of CC-associated symptoms profoundly affect patients’ normal daily activities and overall quality of life.2,7 In addition, the economic impact of CC makes it an important health and social issue.3,7

Various guidelines with sufficient evidence recommend lifestyle and dietary changes, followed by fiber supplements for the management of constipation. Although bulk forming or stimulant and osmotic laxatives are recommended as the first-line drug treatment for constipation, evidence supporting their long-term use is limited.12 A significant number of patients report dissatisfaction with therapy; globally, women use laxatives at a greater frequency than men but the majority are dissatisfied.5,13 Therefore, there is an unmet need for a more effective and well-tolerated drug(s) to treat CC and its associated symptoms.

Prucalopride is a novel, selective, high-affinity, 5-hydroxytryptamine type 4 (5-HT4) receptor agonist with prokinetic activities mediated through the stimulation of colonic contractions that are closely associated with defecation.14 Prucalopride has no clinically relevant interactions at non-target site (e.g., 5-HT1 and 5-HT2) receptors, unlike other 5-HT4 agonists, such as tegaserod and cisapride.15,16 Most importantly, prucalopride has been shown to be effective and well-tolerated in the treatment of CC in a number of randomized controlled clinical trials and follow-up studies lasting as long as 18 months.9,15,17,18

Prucalopride is approved in many countries for the symptomatic treatment of CC in women, in whom laxatives have failed to provide adequate relief, at a recommended daily dose of 2 mg.19 To further evaluate the efficacy and safety of prucalopride in certain patient subgroups, an integrated analysis was performed on the pooled data from 4 phase-III, randomized multicenter studies, on CC-associated symptoms, normalization of bowel function and safety, in Asian and non-Asian women, over 12 weeks.

Materials and Methods

Data were pooled from the 4 phase-III, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel group prucalopride studies (3 pivotal studies: NCT00488137, NCT00483886 and NCT00485940, and one Asia-Pacific study, NCT01116206) with similar study designs. The methodologies for the original trials have been published earlier, and are briefly summarized in this paper.9,15,17,20

Study Population

All 4 studies recruited adults (≥ 18 years; ≥ 18–65 years, Asia-Pacific study) with a history of CC for at least 6 months before their enrollment. To be included in the study, patients should document ≤ 2 spontaneous complete bowel movements (SCBMs) (≤ 2 spontaneous bowel movements [SBMs], Asia-Pacific study) per week during the run-in period, as well as the occurrence of any one of the following: hard/very hard stools, a sensation of incomplete evacuation or straining during defecation on at least 25% of all efforts at defecation. The BMs were considered spontaneous when they occurred more than 24 hours after the last intake of a laxative. Patients were considered ineligible for participation, if constipation was secondary to either drugs or underlying medical disorders (endocrine, metabolic or neurologic), prior surgery, or to any organic disorder of the large intestine or megacolon; if uncontrolled cardiovascular disease, liver and lung diseases, psychiatric disorder, or impaired renal function (serum creatinine > 180 μmol/L) was present or abnormal laboratory values were evident. In addition, pregnant (a positive serum β-human chorionic gonadotropin test), breast-feeding women or women of child-bearing potential were excluded from the study.

Study Design

All 4 studies consisted of a 2-week, drug-free, run-in period followed by a 12-week double-blind treatment period wherein the patients were randomized (1:1:1) to receive prucalopride 2 mg, 4 mg or matching placebo tablets once-daily before breakfast; the Asia-Pacific study included only prucalopride 2 mg and placebo groups (1:1). For this integrated analyses, data from prucalopride 2 mg and placebo treatment groups were included. Patients did not receive a regular laxative, but bisacodyl up to 15 mg daily was allowed as a rescue medication if a patient did not have BMs for ≥ 3 consecutive days. If required, an enema could be administered. The administration of rescue medications was not permitted during the 48 hours before, and after the start of study treatment to avoid interference in the assessment of the time to the first BM after the treatment was started. The details about the use of rescue medication were documented in patient diaries. Imputations were performed for patients who had incomplete data but had ≥ 7 completed diary days after week 1 of the treatment period; the last 7 diary days with available data were carried forward to fill in the missing diary days.

All the studies were conducted in accordance with the Good Clinical Practice Guidelines of the International Conference on Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use, the Declaration of Helsinki, and local laws and regulations. Each clinical trial protocol was reviewed and approved by the respective institutional ethics committees or local independent review boards of participating centers. All the patients provided written informed consent.

Efficacy Evaluations and Endpoints

The efficacy data were collected using patient diary and validated questionnaire, where patients provided the details of study medications, stool frequency, and stool characteristics during the 2-week run-in, and the 12-week treatment periods. Also, the following variables were derived from the diary information: the proportion of patients with an average of ≥ 3 SCBMs/week over 12 weeks (primary endpoint in all 4 studies); the proportion of patients with an average of ≥ 3 SCBMs/week (1–4 weeks); the proportion of patients with an average increase of ≥ 1 SCBMs/week and ≥ 1 SBMs/week, over 12 weeks compared to baseline; the average number of SBMs and SCBMs/week; patients’ satisfaction with their bowel function and treatment, and their perception of the severity of constipation symptoms. Patient Assessment of Constipation-Symptoms (PAC-SYM) surveys21 for the presence of, and changes in constipation related symptoms (bloating, abdominal pain, hard stool and straining) were performed at weeks 2, 4, 8 and 12. Patient Assessments of Constipation-Quality of Life (PAC-QOL) subscales22 (physical discomfort, psychosocial discomfort, worries and concerns, and dissatisfaction) for the effect of constipation on their daily lives were performed at weeks 4 and 12.

In addition to the primary and secondary endpoints of the original studies, the associations between improvement in the subscale scores (≥ 1 point increase, baseline to Week 12) of PAC-SYM and PAC-QOL and efficacy response (increase of ≥ 1 SCBMs/week or ≥ 1 SBMs/week) in Asian and non-Asian women were also evaluated using the pooled data.

Safety Assessments

Safety and tolerability were continuously monitored throughout the study period by assessing treatment emergent adverse events (TEAEs), vital signs, clinically relevant changes in physical examination, laboratory tests (hematology, biochemistry and urinalysis), and electrocardiogram parameters. A follow-up of approximately 7 days post-treatment was conducted for all the patients to complete the evaluations.

Statistical Methods

Patient level data of Asian and non-Asian women from all 4 studies were pooled and analyzed using similar statistical tests, as those in the original published studies. For both the treatment groups, the efficacy and safety analyses included all randomized patients who received at least one dose of the study medication after randomization, i.e., the intent-to-treat analysis set. Missing data were imputed with the last observation carried forward (LOCF) method. Baseline demographic factors: race (discrete variable); age, weight, and duration of CC (continuous variables); and constipation history were summarized. The Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel Chi-square test controlling for baseline severity and study was performed to compare the treatment groups for categorical efficacy endpoints. Changes from baseline at prescribed endpoints in each of the 4 item scores of PAC-SYM sub-scales (on a 5-point Likert scale) were calculated; a negative value of change in scores indicated improvement in the symptoms from baseline. An analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model was applied in the analysis of the change from baseline in each symptom score, with treatment, study and baseline SBM frequency as factors, and baseline symptom score as a covariate for each subgroup. The associations between improvement of ≥ 1 point in each of the 4 items of PAC-SYM and PAC-QOL from baseline to week 12 and efficacy response (average increase of 1 SCBM/week and ≥ 1 SBMs/week) were evaluated by the estimated OR and the 95% CI of the OR.

All the reported P-values are two sided. The statistical tests were performed with 5% levels of significance. Patients who dropped out or discontinued early (< 14 days) or with insufficient diary data were considered non-responders for the primary endpoint.

Results

Patients’ Characteristics

Summary of demography and constipation history for all women included in this analysis are provided in Table 1. Overall 1,596 women (26.6% Asian, 73.4% non-Asian) were included in the analysis. Average age was 44.1 years and the mean body mass index was 24.3 kg/m2. At baseline, more severe constipation (< 1 average SBM/week) was present in 45% of Asian and 28.6% of non-Asian patients, mean (SD) SBMs/week was 1.1 (0.84) vs. 3.4 (3.79), respectively; and overall, the mean (SD) SCBMs/week was 0.4 (0.63). The average number of bisacodyl tablets used per week was 1.9 (Table 1). At baseline, bloating, abdominal pain, hard stool, and straining of severe to very severe category were present in 50.7%, 24.2%, 43.2% and 58.4% of patients, respectively. Abdominal pain was more prevalent in non-Asian patients (84.7%) than in Asian patients (47.1%) (Table 2).

Table 1.

Baseline Demographics and Disease Characteristics of Asian and Non-Asian Women (Intent-to-Treat Analysis Set)

| Variables | Asian (n = 424) | Non-Asian (n = 1,172) | Total (N = 1,596) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean [SD], yr) | 41.0 (12.92) | 45.2 (13.63) | 44.1 (13.57) |

| Baseline BMI (mean [SD], kg/m2) | 22.1 (3.07) | 25.2 (5.06)a | 24.3 (4.81)b |

| Average BMs/wk (mean [SD]) | 2.2 (0.98) | 5.3 (3.65)c | 4.5 (3.46)d |

| Average SBMs/wk (n [%]) | |||

| < 1 | 191 (45.0) | 334 (28.6)c | 525 (33.0)d |

| 1–2 | 213 (50.2) | 203 (17.4)c | 416 (26.1)d |

| > 2e | 20 (4.7) | 632 (54.1)c | 652 (40.9)d |

| Mean (SD) | 1.1 (0.84) | 3.4 (3.79)c | 2.8 (3.43)d |

| Average SCBMs/wk (mean [SD]) | 0.3 (0.45) | 0.4 (0.68)c | 0.4 (0.63)d |

| Average bisacodyl/wk (n [%]) | |||

| 0 | 121 (28.5) | 363 (31.1)c | 484 (30.4)d |

| < 2 | 161 (38.0) | 322 (27.5)c | 483 (30.3)d |

| ≥ 2 | 142 (33.5) | 484 (41.4)c | 626 (39.3)d |

| Mean (SD) | 1.6 (1.73) | 2.1 (2.46)c | 1.9 (2.30)d |

| Average enema/wk (mean [SD]) | 0.1 (0.30) | 0.1 (0.34)c | 0.1 (0.33)d |

| Average number of days with bisacodyl/wk (mean [SD]) | 0.9 (0.82) | 0.9 (0.91) | 0.9 (0.89) |

| Average number of days with bisacodyl or enema/wk (mean [SD]) | 1.0 (0.87) | 0.9 (0.94) | 0.9 (0.92) |

n = 1,170;

N = 1,594;

n = 1,169;

N = 1,593;

Based on patients’ diary data before the day of first dose, and the numbers of spontaneous bowel movements (SBMs)/week at baseline could be different from the investigator’s calculation at randomization in Asia-Pacific study.

n, sub-group population; N, total population; SD, standard deviation; yr, year; BMI, body mass index; BM, bowel movement; wk, week; SCBM, spontaneous complete bowel movement.

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics of Symptoms (Patient Assessment of Constipation-Symptom Subscales) (Intent-to-Treat Analysis Set)

| Symptoms | Asian (n = 424) | Non-Asian (n = 1,168) | Total (N = 1,592) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bloating (n [%]) | |||

| No | 63 (14.9) | 42 (3.6)a | 105 (6.6)b |

| Mild/moderate | 226 (53.3) | 454 (38.9)a | 680 (42.7)b |

| Severe/very severe | 135 (31.8) | 671 (57.5)a | 806 (50.7)b |

| Abdominal pain (n [%]) | |||

| No | 224 (52.8) | 177 (15.3)c | 401 (25.3)d |

| Mild/moderate | 160 (37.7) | 639 (55.1)c | 799 (50.5)d |

| Severe/very severe | 40 (9.4) | 343 (29.6)c | 383 (24.2)d |

| Hard stool (n [%]) | |||

| No | 76 (18.0) | 178 (15.3)e | 254 (16.0)f |

| Mild/moderate | 202 (47.8) | 445 (38.3)e | 647 (40.8)f |

| Severe/very severe | 145 (34.3) | 540 (46.4)e | 685 (43.2)f |

| Straining (n [%]) | |||

| No | 29 (6.8) | 60 (5.2)g | 89 (5.6)h |

| Mild/moderate | 159 (37.5) | 412 (35.5)g | 571 (36.0)h |

| Severe/very severe | 236 (55.7) | 689 (59.3)g | 925 (58.4)h |

n = 1,167;

N = 1,591;

n = 1,159;

N = 1,583;

n = 1,163;

N = 1,586;

n = 1,161;

N = 1,585.

PAC-SYM, Patient Assessment of Constipation-Symptoms; n, sub-group population; N, total population in intent-to-treat analysis set, 4 patients in pivotal studies did not have PAC-SYM data at baseline.

Primary and Secondary Endpoints

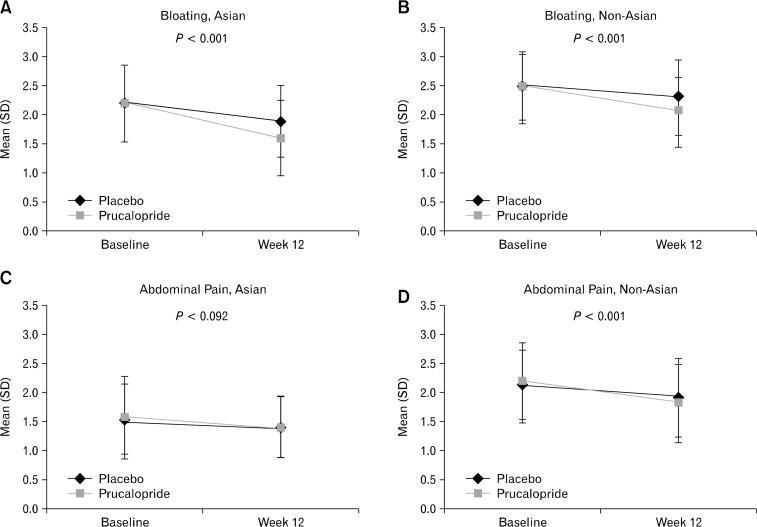

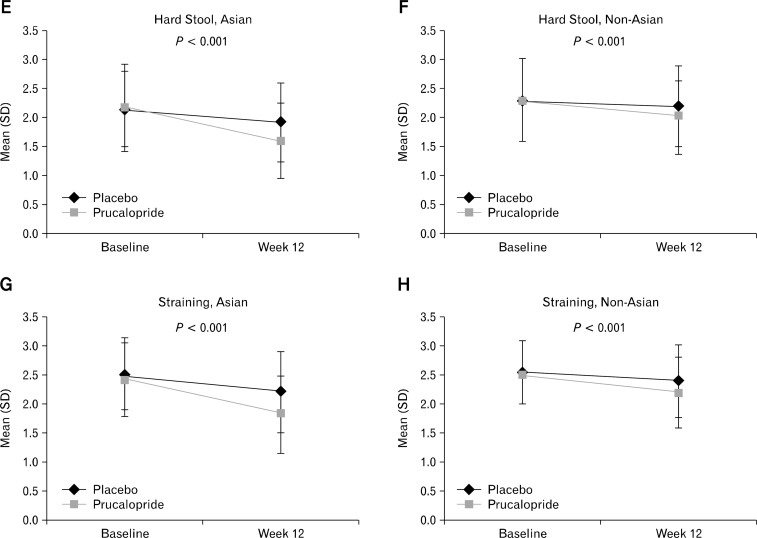

The results from the analyses of the primary and secondary endpoints in Asian and non-Asian women are presented in Table 3. Significantly more (P < 0.001) patients in both subgroups experienced ≥ 3 SCBMs/week in the prucalopride group compared with placebo (Asian [34% vs. 11%], non-Asian [24.6% vs. 10.6%]) over 12 weeks; however, no significant difference was observed between the Asian and non-Asian subgroups in the prucalopride group (P = 0.693). Also, averaged over the first 4 weeks of treatment, prucalopride group had significantly more patients (P < 0.001) reporting ≥ 3 SCBMs/week versus placebo in both Asian (36.3% vs. 12.0%) and non-Asian (29.2% vs. 9.8%) subgroups with no statistical significance between the subgroups in the prucalopride group (P = 0.380). Furthermore, significantly more prucalopride-treated patients reported an increase of ≥ 1 SCBMs/week above baseline, than patients in the placebo group in both Asians (treatment difference, 29.1%; 95% CI, 20.0–38.2) and non-Asians (21.4%; 95% CI, 16.0–26.8) (both, P < 0.001) at week 12 (Table 3); with no statistical significance between the Asian vs. non-Asian subgroups in the prucalopride group (P = 0.725). In addition to the improvement in bowel frequency, prucalopride significantly (P < 0.001) reduced symptom scores for bloating, hard stool, and straining versus placebo in Asian and non-Asian women over 12 weeks, and reduced abdominal pain in non-Asian women (Figure).

Table 3.

Percentage of Patients With ≥ 3 Spontaneous Complete Bowel Movements/Week and Average Increase of ≥ 1 Spontaneous Complete Bowel Movements/Week Over 4 and 12 Weeks in Asian and Non-Asian Women (Intent-to-Treat Analysis Set)

| Variable | Asian (n [%]) | Non-Asian (n [%]) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≥ 3 SCBMs/wk (1–12 wk) | |||

| Prucalopridea (n [%]) | 73 (34.0) | 142 (24.6) | 0.693e |

| Placebob (n [%]) | 23 (11.0) | 63 (10.6) | |

| Prucalopride minus placebo (difference % [95% CI]) | 22.9 (15.3–30.6)f | 14.0 (9.7–18.3)f | |

| ≥ 3 SCBMs/wk (1–4 wk) | |||

| Prucalopridea (n [%]) | 78 (36.3) | 169 (29.2) | 0.380e |

| Placebob (n [%]) | 25 (12.0) | 58 (9.8) | |

| Prucalopride minus placebo (difference % [95% CI]) | 24.3 (16.5, 32.1)f | 19.5 (15.1–23.9)f | |

| Increase ≥ 1 SCBMs/wk (1–12 wk) | |||

| Prucalopridec (n [%]) | 120 (57.4) | 252 (45.3) | 0.725e |

| Placebod (n [%]) | 58 (28.3) | 139 (24.0) | |

| Prucalopride minus placebo (difference % [95% CI]) | 29.1 (20.0–38.2)f | 21.4 (16.0–26.8)f |

Asian (n = 215), Non-Asian (n = 578);

Asian (n = 209), Non-Asian (n = 594);

Asian (n = 209), Non-Asian (n = 556);

Asian (n = 205), Non-Asian (n = 580);

Between subgroup difference (Asian vs. non-Asian) in the prucalopride group;

For all the differences, P < 0.001: normal approximation to binomial distribution; generalized Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel Chi-square test for general association controlling for baseline severity and study.

n, sub-group population; SCBMs, spontaneous complete bowel movements; wk, week; CI, confidence interval.

Figure.

Symptom Changes (Patient Assessment of Constipation-Symptoms scores) from Baseline after treatment (week 12, last observation carried forward) for Asian and Non-Asian women (intent-to-treat analysis set) (A-H). The statistical tests were performed for no difference between treatments from ANCOVA model with factor(s) treatment, base, trial and baseline severity (type III SS); lower scores reflect improvement.

Associations of Patient Assessment of Constipation-Symptoms and Patient Assessments of Constipation-Quality of Life Subscale Scores With Response in Efficacy

Table 4 illustrates an association between improvements in the PAC-SYM or PAC-QOL subscale scores and each of the responses in constipation outcomes (average increase of ≥ 1 SCBMs/week and ≥ 1 SBMs/week) in both subgroups at week 12 (LOCF). Associations were significant if the estimated OR was > 1 and 95% CIs excluded the value 1 for both the subgroups. Improvements in each item of PAC-SYM subscales scores (≥ 1 points, yes/no) were significantly associated with clinical efficacy in both subgroups, with the exception of the association between abdominal pain, and average increase of ≥ 1 SCBMs/week (yes/no) in Asian patients. Furthermore, the response in efficacy was significantly associated with improvements (≥ 1 points, yes/no) in PAC-QOL subscales in both Asian and non-Asian patients with the exception of physical discomfort, psychosocial discomfort, and worries and concerns in relation to an average increase of ≥ 1 SCBMs/week (yes/no) in Asian patients.

Table 4.

Association Between Improvement in the Patient Assessment of Constipation-Symptom/Patient Assessment of Constipation-Quality of Life Subscale Scores and Response in the Efficacy Variables Among Asian and Non-Asian Women at Week 12 (Last Observation Carried Forward)

| Variables | Asian | Non-Asian |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| PAC-SYM subscales scores, increase of ≥ 1/< 1 point (OR [95% CI]) | ||

| Increase of ≥ 1/< 1 SCBM/wk | ||

| Bloating | 1.6 (1.06–2.34) | 3.9 (2.96–5.07) |

| Abdominal pain | 1.3 (0.88–2.07) | 2.0 (1.58–2.61) |

| Hard stool | 2.7 (1.81–4.11) | 2.5 (1.95–3.24) |

| Straining | 3.2 (2.07–4.81) | 3.2 (2.44–4.11) |

| Increase of ≥ 1/< 1 SBM/wk | ||

| Bloating | 1.7 (1.13–2.65) | 2.9 (2.25–3.65) |

| Abdominal pain | 1.7 (1.06–2.83) | 1.9 (1.53–2.46) |

| Hard stool | 2.5 (1.63–3.85) | 2.0 (1.60–2.57) |

| Straining | 2.7 (1.74–4.12) | 2.1 (1.68–2.71) |

| PAC-QOL subscales scores, increase of ≥ 1/< 1 point (OR [95% CI]) | ||

| Increase of ≥ 1/< 1 SCBM/wk | ||

| Physical discomfort | 1.3 (0.89–2.00) | 5.1 (3.94–6.72) |

| Psychosocial discomfort | 1.2 (0.74–1.81) | 2.6 (1.94–3.47) |

| Worries and concerns | 1.4 (0.91–2.10) | 3.6 (2.78–4.70) |

| Dissatisfaction | 3.5 (2.26–5.28) | 9.0 (6.74–11.90) |

| Increase of ≥ 1/< 1 SBM/wk | ||

| Physical discomfort | 2.6 (1.62–4.29) | 4.1 (3.14–5.23) |

| Psychosocial discomfort | 2.7 (1.50–4.71) | 2.6 (1.95–3.59) |

| Worries and concerns | 2.3 (1.37–3.73) | 3.5 (2.65–4.54) |

| Dissatisfaction | 4.2 (2.46–7.27) | 8.1 (5.99–11.03) |

PAC-SYM, Patient Assessment of Constipation-Symptom; PAC-QOL, Patient Assessment of Constipation-Quality of Life; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; SCBMs, spontaneous complete bowel movements; wk, week; SBMs: spontaneous bowel movements.

If the 95% CI of OR excludes 1, then the association is statistically significant, otherwise it is insignificant (P > 0.05).

Safety and Tolerability

TEAEs were observed in 35.9% and 68.5% (Asian and non-Asian) patients in the placebo group and 58.1% and 78.2% (Asian and non-Asian) patients in the prucalopride group. A significant difference was observed between the Asian and non-Asian subgroups in the prucalopride group for total patients reporting at least 1 TEAE (P < 0.001). Non-Asian patients showed a higher percentage of nausea, abdominal pain, and headache in the prucalopride group as well as in the placebo group; by contrast, diarrhea was seen more in the Asian group than in the non-Asian group, irrespective of the treatment they received. Other TEAEs, including dizziness, vomiting, flatulence and upper abdominal pain were also more common in the non-Asian group (Table 5). The majority of TEAEs were transient, and mild to moderate in severity.

Table 5.

Treatment-emergent Adverse Events in at Least 2% of Patients in Any Treatment Group in Asian and Non-Asian Women (Intent-to-Treat Analysis Set)

| Variables | Asian (n [%]) | Non-Asian (n [%]) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| Placebo (n = 209) | Prucalopride 2 mg (n = 215) | Placebo (n = 594) | Prucalopride 2 mg (n = 578) | |

| Total patients with at least one adverse eventa | 75 (35.9) | 125 (58.1) | 407 (68.5) | 452 (78.2) |

| Nausea | 5 (2.4) | 27 (12.6) | 62 (10.4) | 120 (20.8) |

| Abdominal pain | 5 (2.4) | 15 (7.0) | 67 (11.3) | 72 (12.5) |

| Diarrhoea | 17 (8.1) | 48 (22.3) | 27 (4.5) | 77 (13.3) |

| Abdominal distension | 5 (2.4) | 7 (3.3) | 31 (5.2) | 42 (7.3) |

| Headache | 4 (1.9) | 23 (10.7) | 90 (15.2) | 159 (27.5) |

| Dizziness | 4 (1.9) | 3 (1.4) | 14 (2.4) | 30 (5.2) |

| Vomiting | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.4) | 21 (3.5) | 33 (5.7) |

| Flatulence | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 22 (3.7) | 29 (5.0) |

| Abdominal pain upper | 3 (1.4) | 4 (1.9) | 21 (3.5) | 28 (4.8) |

| Dyspepsia | 3 (1.4) | 3 (1.4) | 18 (3.0) | 20 (3.5) |

| Abdominal tenderness | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 13 (2.2) | 14 (2.4) |

| Abnormal gastrointestinal sounds | 0 (0.0) | 5 (2.3) | 2 (0.3) | 4 (0.7) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 9 (4.3) | 7 (3.3) | 26 (4.4) | 27 (4.7) |

| Influenza | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 23 (3.9) | 24 (4.2) |

| Sinusitis | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 20 (3.4) | 24 (4.2) |

| Urinary tract infection | 5 (2.4) | 2 (0.9) | 17 (2.9) | 17 (2.9) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 4 (1.9) | 6 (2.8) | 16 (2.7) | 17 (2.9) |

| Back pain | 1 (0.5) | 2 (0.9) | 20 (3.4) | 19 (3.3) |

| Muscle spasms | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (1.5) | 16 (2.8) |

| Fatigue | 1 (0.5) | 2 (0.9) | 8 (1.3) | 19 (3.3) |

| Insomnia | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 10 (1.7) | 12 (2.1) |

Incidence is based on the number of patients experiencing at least one adverse event, not the number of events; preferred terms used for adverse events.

Statistically significant difference between Asian and non-Asian subgroups in prucalopride group (P < 0.001).

Discussion

The results of this integrated analysis of 4, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase-III studies showed that once-daily prucalopride 2 mg significantly improved stool frequency and reduced the severity of CC-associated symptoms compared with placebo in Asian and non-Asian women, over 12 weeks. In both subgroups, prucalopride resulted in a significantly (P < 0.001) higher percentage of patients with an average of ≥ 3 SCBMs/week and an increase of ≥ 1 SCBMs/week compared with placebo; differences between the Asian and non-Asian subgroups were not statistically significant, when compared for these improvements (P > 0.05). However, achieving primary efficacy endpoint (average of ≥ 3 SCBMs/week) with 12-week prucalopride treatment in approximately 25%–34% (non-Asian, 24.6% vs. 10.6%; Asian, 34% vs. 11%) of the overall patients, representing respective therapeutic gain of 14% (95% CI, 9.7–18.3; P < 0.001) to 23% (95% CI, 15.3–30.6; P < 0.001) over placebo is clinically relevant, as accepted in the 3 pivotal studies and the Asia-Pacific study.9,17,18,20

Although, there was no head-to-head statistical comparison of the demographics of the two populations at baseline, Asian patients had numerically more severe constipation (average SBMs, 1.1 vs. 3.4), less abdominal pain (9.4% vs. 29.6%) and lower levels of bloating (31.8% vs. 57.5%) compared to non-Asians. The presence of more abdominal pain and a higher level of bloating in the non-Asian group at baseline suggest the possible overlap with functional gastrointestinal disorders in some patients. Also, it could explain the observed better responses to prucalopride for the clinical symptom outcomes in Asians compared with non-Asian populations, despite more severe constipation at baseline in Asian patients.

Improvement in stool frequency (SCBM) is the most relevant endpoint to evaluate the therapeutic efficacy; however this parameter alone may not accurately estimate the effectiveness of constipation therapy, as patients often equate constipation with stool consistency, feeling of completeness, straining and urge of defecation.23 Furthermore, individual CC-associated symptoms are often severe; among those, bloating, straining and hard stool are the most bothersome.1 These symptoms affect QOL in more than 50% of patients, with most being dissatisfied with laxatives and traditional therapies.1 Thus in order to achieve overall clinical efficacy, all CC-associated symptoms present at baseline must be relieved effectively in addition to the improvement of SCBMs. In this integrated analyses, treatment with prucalopride more significantly (P < 0.001) reduced the symptom scores for bloating, hard stool and straining than placebo in both subgroups, over 12 weeks, and symptom scores for abdominal pain was reduced significantly (P < 0.001) in non-Asian patients who had higher pain scores at baseline.

Effectiveness of therapy for CC should emphasize, in addition to the proportionate improvement of bowel frequency, on predominant symptoms and psychosocial distress.10,24,25 This post hoc analysis demonstrated positive associations between improvement in symptoms (improvement of ≥ 1 point) and efficacy response (average increase of ≥ 1 SCBMs/week and average increase of ≥ 1 SBMs/week) with prucalopride treatment. Significant associations were established between improvements in bloating, hard stools and straining and responses in efficacy variables in Asian and non-Asian patients. Also, the improvements in PAC-QOL subscales were significantly associated with the efficacy response (average increase of ≥ 1 SCBMs/week and average increase of ≥ 1 SBMs/week) in both Asian and non-Asian women, except for associations between improvements in physical discomfort, psychosocial discomfort, and worries and concerns.

The incidence of TEAEs were similar between the placebo and prucalopride treatment groups, except for the most frequently reported TEAEs including nausea, diarrhea and headache, which were more commonly reported in patients treated with prucalopride. Overall, prucalopride had an acceptable safety and tolerability profile, which is consistent with those observed in a series of studies.18,26–30 However, there were some differences observed in these analyses in TEAEs between Asians and non-Asians (Table 5); significantly more non-Asian women complained at least 1 TEAE in both the treatment groups (P < 0.001). This may be due to the differences in genetic factors (different pharmacokinetic profile) or cultural factors (tendency to report adverse events) between Asian and non-Asian patients. More non-Asian patients reported abdominal pain at baseline, with some of them possibly having overlapping functional gastrointestinal disorders.

The percentage of non-Asian women included in this analysis was higher (73.4%) than that of Asian women (26.6%); however, this number was sufficient for the exploratory analysis. Based on the present results, prucalopride appears to be an important addition to the therapeutic agents for treating CC, especially in women poorly responding to laxatives.

Conclusion

This integrated analysis showed that once-daily 2 mg prucalopride treatment over 12 weeks was more efficacious than placebo in promoting stool frequency and improvement of CC-associated symptoms in both Asian and non-Asian women, and was found to be safe and well-tolerated. The efficacy of prucalopride was supported by significant associations between improvement of symptoms and quality of life.The numeric differences between Asian and non-Asian women on efficacy and TEAEs may be partially explained by the presence of the overlap of functional gastrointestinal symptoms in non-Asian women.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Mr Onkar Rathod (SIRO Clinpharm Pvt. Ltd.) for providing writing assistance and Dr Venugopal Madhusudhana (SIRO Clinpharm Pvt. Ltd.) for additional editorial support for the development of this manuscript. The authors also thank the study participants of the four studies, without whom the studies would never have been accomplished, and the investigators for their participation in the studies.

Footnotes

Financial support: The studies presented in this report are supported by Janssen Research and Development. The Janssen companies are members of the Johnson & Johnson companies. The sponsor also provided a formal review of this manuscript.

Conflicts of interest: JinYong Kim is an employee of Janssen Asia-Pacific. Andy Liu is a contract employee of Janssen Research and Development, Shanghai, China. Jan Tack has served as an advisor to Shire-Movetis, Johnson & Johnson and Almirall, and has received honoraria for speaking engagements from Abbott, Almirall, AstraZeneca, Danone, Janssen, Menarini, Novartis, Shire-Movetis, Takeda and Zeria. Jan Tack had also received consultancy fees from Almirall, AstraZeneca, Cosucra, Danone, GI Dynamics, GlaxoSmithKline, Ironwood, Janssen, Menarini, Novartis, Rhythm, Shire, Takeda, Theravance, Tranzyme, Tsumura, Will Pharma and Zeria. Eamonn M M Quigley has served as an advisor to Janssen and Shire-Movetis, and has received honoraria for speaking engagements from Almirall, Janssen and Shire-Movetis.

References

- 1.Johanson JF, Kralstein J. Chronic constipation: a survey of the patient perspective. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:599–608. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanchez MIP, Bercik P. Epidemiology and burden of chronic constipation. Can J Gastroenterol. 2011;25(suppl B):11B–15B. doi: 10.1155/2011/974573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dennison C, Prasad M, Lloyd A, Bhattacharyya SK, Dhawan R, Coyne K. The health-related quality of life and economic burden of constipation. Pharmacoeconomics. 2005;23:461–476. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200523050-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stewart WF, Liberman JN, Sandler RS, et al. Epidemiology of constipation (EPOC) study in the United States: relation of clinical sub-types to sociodemographic features. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:3530–3540. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wald A, Scarpignato C, Mueller-Lissner S, et al. A multinational survey of prevalence and patterns of laxative use among adults with self-defined constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:917–930. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Higgins PD, Johanson JF. Epidemiology of constipation in North America: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:750–759. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peppas G, Alexiou VG, Mourtzoukou E, Falagas ME. Epidemiology of constipation in Europe and Oceania: a systematic review. BMC Gastroenterol. 2008;8:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-8-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Talley NJ, O’Keefe EA, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ., 3rd Prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms in the elderly: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:895–901. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)90175-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Camilleri M, Kerstens R, Rykx A, Vandeplassche L. A placebo-controlled trial of prucalopride for severe chronic constipation. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2344–2354. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0800670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, Houghton LA, Mearin F, Spiller RC. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1480–1491. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lacy BE, Levenick JM, Crowell M. Chronic constipation: new diagnostic and treatment approaches. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2012;5:233–247. doi: 10.1177/1756283X12443093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones MP, Talley NJ, Nuyts G, Dubois D. Lack of objective evidence of efficacy of laxatives in chronic constipation. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:2222–2230. doi: 10.1023/a:1020131126397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muller-Lissner S, Tack J, Feng Y, Schenck F, Specht Gryp R. Levels of satisfaction with current chronic constipation treatment options in Europe - an internet survey. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37:137–145. doi: 10.1111/apt.12124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Schryver AM, Andriesse GI, Samsom M, Smout AJ, Gooszen HG, Akkermans LM. The effects of the specific 5HT4 receptor agonist, prucalopride, on colonic motility in healthy volunteers. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:603–612. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quigley EM, Vandeplassche L, Kerstens R, Ausma J. Clinical trial: the efficacy, impact on quality of life, and safety and tolerability of prucalopride in severe chronic constipation--a 12-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:315–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tack J, Camilleri M, Chang L, et al. Systematic review: cardiovascular safety profile of 5-HT4 agonists developed for gastrointestinal disorders. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:745–767. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05011.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tack J, van Outryve M, Beyens G, Kerstens R, Vandeplassche L. Prucalopride (Resolor) in the treatment of severe chronic constipation in patients dissatisfied with laxatives. Gut. 2009;58:357–365. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.162404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Camilleri M, Van Outryve MJ, Beyens G, Kerstens R, Robinson P, Vandeplassche L. Clinical trial: the efficacy of open-label prucalopride treatment in patients with chronic constipation - follow-up of patients from the pivotal studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:1113–1123. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Italy: Janssen Cilag S.P.A; 2011. Annex 1: Summary of product characteristics. Available 1. URL: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/001012/WC500053998.pdf (Accessed 5 December, 2013) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ke M, Zou D, Yuan Y, et al. Prucalopride in the treatment of chronic constipation in patients from the Asia-Pacific region: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24:999, e541. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2012.01983.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frank L, Kleinman L, Farup C, Taylor L, Miner P., Jr Psychometric validation of a constipation symptom assessment questionnaire. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999;34:870–877. doi: 10.1080/003655299750025327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marquis P, De La Loge C, Dubois D, McDermott A, Chassany O. Development and validation of the Patient Assessment of Constipation Quality of Life questionnaire. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:540–551. doi: 10.1080/00365520510012208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pare P, Ferrazzi S, Thompson WG, Irvine EJ, Rance L. An epidemiological survey of constipation in canada: definitions, rates, demographics, and predictors of health care seeking. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:3130–3137. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.05259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leung L, Riutta T, Kotecha J, Rosser W. Chronic constipation: an evidence-based review. J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24:436–451. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2011.04.100272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lindberg G, Hamid SS, Malfertheiner P, et al. World Gastroenterology Organisation global guideline: Constipation-a global perspective. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45:483–487. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31820fb914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Everhart JE, Go VL, Johannes RS, Fitzsimmons SC, Roth HP, White LR. A longitudinal survey of self-reported bowel habits in the United States. Dig Dis Sci. 1989;34:1153–1162. doi: 10.1007/BF01537261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quigley EM. Prucalopride: safety, efficacy and potential applications. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2012;5:23–30. doi: 10.1177/1756283X11423706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poen AC, Felt-Bersma RJ, Van Dongen PA, Meuwissen SG. Effect of prucalopride, a new enterokinetic agent, on gastrointestinal transit and anorectal function in healthy volunteers. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:1493–1497. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1999.00629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tack J, Muller-Lissner S, Stanghellini V, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of chronic constation--a European perspective. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;23:697–710. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2011.01709.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tack J, Corsetti M. Prucalopride: evaluation of the pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, efficacy and safety in the treatment of chronic constipation. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2012;8:1327–1335. doi: 10.1517/17425255.2012.719497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]