Abstract

Background

People with schizophrenia from families that express high levels of criticism, hostility, or over involvement, have more frequent relapses than people with similar problems from families that tend to be less expressive of emotions. Forms of psychosocial intervention, designed to reduce these levels of expressed emotions within families, are now widely used.

Objectives

To estimate the effects of family psychosocial interventions in community settings for people with schizophrenia or schizophrenia-like conditions compared with standard care.

Search strategy

We updated previous searches by searching the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group Trials Register (September 2008).

Selection criteria

We selected randomised or quasi-randomised studies focusing primarily on families of people with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder that compared community-orientated family-based psychosocial intervention with standard care.

Data collection and analysis

We independently extracted data and calculated fixed-effect relative risk (RR), the 95% confidence intervals (CI) for binary data, and, where appropriate, the number needed to treat (NNT) on an intention-to-treat basis. For continuous data, we calculated mean differences (MD).

Main results

This 2009-10 update adds 21 additional studies, with a total of 53 randomised controlled trials included. Family intervention may decrease the frequency of relapse (n = 2981, 32 RCTs, RR 0.55 CI 0.5 to 0.6, NNT 7 CI 6 to 8), although some small but negative studies might not have been identified by the search. Family intervention may also reduce hospital admission (n = 481, 8 RCTs, RR 0.78 CI 0.6 to 1.0, NNT 8 CI 6 to 13) and encourage compliance with medication (n = 695, 10 RCTs, RR 0.60 CI 0.5 to 0.7, NNT 6 CI 5 to 9) but it does not obviously affect the tendency of individuals/families to leave care (n = 733, 10 RCTs, RR 0.74 CI 0.5 to 1.0). Family intervention also seems to improve general social impairment and the levels of expressed emotion within the family. We did not find data to suggest that family intervention either prevents or promotes suicide.

Authors’ conclusions

Family intervention may reduce the number of relapse events and hospitalisations and would therefore be of interest to people with schizophrenia, clinicians and policy makers. However, the treatment effects of these trials may be overestimated due to the poor methodological quality. Further data from trials that describe the methods of randomisation, test the blindness of the study evaluators, and implement the CONSORT guidelines would enable greater confidence in these findings.

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH): *Expressed Emotion, *Family Therapy, *Social Support, Family Relations, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Recurrence [prevention & control], Schizophrenia [*therapy]

MeSH check words: Humans

BACKGROUND

In 1972 an influential study showed that people with schizophrenia from families that express high levels of criticism, hostility, or over involvement have more frequent relapses than people with similar problems from families that tend to be less expressive of their emotions (Brown 1972). A variety of psychosocial interventions designed to reduce these levels of expressed emotions within families now exist. The aim of using these psychosocial approaches is to decrease stress within the family as well as the rate of relapse. These interventions are proposed as adjuncts rather than alternatives to drug treatments.

Description of the condition

Schizophrenia is a chronic, relapsing mental illness and has a worldwide lifetime prevalence of about 1% irrespective of culture, social class and race. Schizophrenia is characterised by positive symptoms such as hallucinations and delusions and negative symptoms such as emotional numbness and withdrawal. One-quarter of those who have experienced an episode of schizophrenia recover and the illness does not recur. Another 25% experience an unremitting illness. Half do have a recurrent illness but with long episodes of considerable recovery from the positive symptoms. Current medication is effective in reducing positive symptoms, but negative symptoms are fairly resistant to treatment. In addition, drug treatments are associated with adverse effects and the overall cost of the illness to the individual, their carers and the community is considerable.

Description of the intervention

Psychosocial family interventions may have a number of different strategies. These include: (a) construction of an alliance with relatives who care for the person with schizophrenia; (b) reduction of adverse family atmosphere (that is, lowering the emotional climate in the family by reducing stress and burden on relatives); (c) enhancement of the capacity of relatives to anticipate and solve problems; (d) reduction of expressions of anger and guilt by the family; (e) maintenance of reasonable expectations for patient performance; (f) encouragement of relatives to set and keep to appropriate limits whilst maintaining some degree of separation when needed; and (g) attainment of desirable change in relatives’ behaviour and belief systems.

How the intervention might work

By reducing levels of expressed emotion, stress, family burden, and enhancing the capacity of relatives to solve problems, whilst maintaining patient compliance with medication, family intervention aims to reduce relapse and subsequent hospitalisation.

Why it is important to do this review

Many important qualitative reviews highlight the possible advantages of using family interventions for those with serious mental illnesses (Leff 1995). Quantitative reviews are less common (Mari 1994).

OBJECTIVES

To estimate the effects of family psychosocial interventions in community settings for the care of people with schizophrenia or schizophrenia-like conditions.

METHODS

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all relevant randomised or quasi-randomised controlled trials.

Types of participants

We included families of people who have a diagnosis of schizophrenia and/or schizoaffective disorder. As a result of Szmukler 2003, we reconsidered the inclusion criteria. This study evaluated family interventions for a group that included people without schizophrenia-like illnesses (less than 17%). It would seem harsh to exclude this study because everyone did not have schizophrenia, and therefore devalue the results of this review for clinicians dealing with a mixed group for whom they feel family intervention may be indicated. Because this decision is post hoc we have included and excluded the data from Szmukler 2003 in order to see if inclusion made a substantive difference. We have discussed the results of these sensitivity analyses below. The objectives of the review remain to estimate the effects of family psychosocial interventions in community settings for the care of people with schizophrenia or schizophrenia-like conditions. Entry criteria for this update have changed and now studies are eligible where most (more than 75%) families include one member with a diagnosis of schizophrenia and/or schizoaffective disorder.

Types of interventions

Any psychosocial intervention with relatives of those with schizophrenia that required more than five sessions.

Standard care, but this was not restricted to an in-patient context/environment.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

-

1

Suicide and all causes of mortality

-

2

Service utilisation

-

2.1

Hospital admission

-

3

Clinical global response

-

3.1

Relapse

Secondary outcomes

-

1

Service utilisation

-

1.2

Days in hospital

-

2

Clinical global response

-

2.2

Global state - not improved

-

2.3

Average change or endpoint score in global state

-

2.4

Leaving the study early

-

2.5

Compliance with medication

-

3

Mental state and behaviour

-

3.1

Positive symptoms (delusions, hallucinations, disordered thinking)

-

3.2

Negative symptoms (avolition, poor self-care, blunted affect)

-

3.3

Average change or endpoint score

-

4

Social functioning

-

4.1

Average change or endpoint scores

-

4.2

Social impairment

-

4.3

Employment status (employed/unemployed)

-

4.4

Work related activities

-

4.5

Unable to live independently

-

4.6

Imprisonment

-

5

Family outcome

-

5.1

Average score/change in family burden

-

5.2

Patient and family coping abilities

-

5.3

Understanding of the family member with schizophrenia

-

5.4

Family care and maltreatment of the person with schizophrenia

-

5.5

Expressed emotion

-

5.6

Quality of life/satisfaction with care for either recipients of care or their carers

-

6

Economic outcomes

-

6.1

Cost of care

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

1. Cochrane Schizophrenia Group Trials Register (update September 2008)

We searched the register using the phrase:

[(*family* or family*) in title, abstract, index terms of REFERENCE] or [(*family* or family*) in interventions of STUDY

This register is compiled by systematic searches of major databases, hand searches and conference proceedings (see Group Module).

2. Previous searches from earlier versions of this review

Please see (Appendix 1).

Searching other resources

1. Handsearching

We searched the reference lists of the review articles and the primary studies to identify possible articles missed by the computerised search.

2. Personal contact

We contacted authors for information regarding unpublished trials.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We independently inspected all reports. We resolved any disagreement by discussion, and where doubt remained, we acquired the full article for further inspection. Once we obtained the full articles, we independently decided whether the studies met the review criteria. If disagreement could not be resolved by discussion, we sought further information and added these trials to the list of those awaiting assessment.

Data extraction and management

We independently extracted data from selected trials. When disputes arose we attempted to resolve these by discussion. When this was not possible and further information was necessary to resolve the dilemma, we did not enter data and added the trial to the list of those awaiting classification.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed risk of bias using the tool described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008). This tool encourages consideration of how the sequence was generated, how allocation was concealed, the integrity of blinding at outcome, the completeness of outcome data, selective reporting and other biases.

If disputes arose as to which category a trial has to be allocated, again, we achieved resolution by discussion, after working with a third reviewer.

Earlier versions of this review used a different, less well-developed, means of categorising risk of bias (see Appendix 2).

Measures of treatment effect

1. Binary data

For binary outcomes we calculated the relative risk (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI) based on the fixed-effect model. Relative risk is more intuitive (Boissel 1999) than odds ratios, and odds ratios tend to be interpreted as RR by clinicians (Deeks 2000). This misinterpretation then leads to an overestimate of the impression of the effect. When the overall results were significant we calculated the number needed to treat (NNT) and the number needed to harm (NNH). Where people were lost to follow up at the end of the study, we assumed that they had had a poor outcome and once they were randomised they were included in the analysis (intention-to-treat/ITT analysis).

Where possible, we made efforts to convert outcome measures to binary data. This can be done by identifying cut-off points on rating scales and dividing participants accordingly into “clinically improved” or “not clinically improved”. It is generally assumed that if there is a 50% reduction in a scale-derived score such as the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS Overall 1962) or the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS, Kay 1986, this could be considered a clinically significant response (Leucht 2005a, Leucht 2005). It is recognised that for many people, especially those with chronic or severe illness, a less rigorous definition of important improvement (e.g. 25% on the BPRS) would be equally valid. If individual patient data are available, we used the 50% cut-off point for non-chronically ill people and a 25% cut-off point for those with chronic illness. If data based on these thresholds were not available, we used the primary cut-off presented by the original authors.

2. Continuous data

2.1 Skewed data

Continuous data on outcomes in mental health trials are often not normally distributed. To avoid the pitfall of applying parametric tests to non-parametric data, we applied the following standards to all endpoint data derived from continuous measures. The criteria were used before inclusion: (a) standard deviations and means had to be obtainable; and, for finite scores, such as endpoint measures on rating scales, (b) the standard deviation (SD), when multiplied by two, had to be less than the mean (as otherwise the mean was unlikely to be an appropriate measure of the centre of the distribution) (Altman 1996). If a scale starts from a positive value (such as PANSS, which can have values from 30 to 210) the calculation described above in (b) should be modified to take the scale starting point into account. In these cases skew is present if 2SD>(S-Smin), where S is the mean score and Smin is the minimum score.

We did not show skewed endpoint data from studies with fewer than 200 participants graphically, but added these to the ‘Other data’ tables and briefly commented on in the text. However, skewed endpoint data from larger studies (200 or more participants) pose less of a problem and we entered the data for analysis.

For continuous mean change data (endpoint minus baseline) the situation is even more problematic. In the absence of individual patient data it is impossible to know if change data are skewed. The RevMan meta-analyses of continuous data are based on the assumption that the data are, at least to a reasonable degree, normally distributed. Therefore we included such data, unless end-point data were also reported from the same scale.

2.2 Final endpoint value versus change data

Where both final endpoint data and change data were available for the same outcome category, we presented only final endpoint data. We acknowledge that by doing this much of the published change data may be excluded, but argue that endpoint data is more clinically relevant and that if change data were to be presented along with endpoint data, it would be given undeserved equal prominence. We have contacted authors of studies reporting only change data for endpoint figures.

2.3 Crossover design

Where we have included crossover design studies, we have negated the potential additive effect in the second or later stages on these trials by only analysing data from the first stage.

2.4 Scale-derived data

A wide range of instruments are available to measure mental health outcomes. These instruments vary in quality and many are not valid, and are known to be subject to bias in trials of treatments for schizophrenia (Marshall 2000). Therefore we included continuous data from rating scales only if the measuring instrument had been described in a peer-reviewed journal.

Whenever possible we took the opportunity to make direct comparisons between trials that used the same measurement instrument to quantify specific outcomes. Where continuous data were presented from different scales rating the same effect, we presented both sets of data and inspected the general direction of effect.

2.5 Tables and figures

Where possible we entered data into RevMan in such a way that the area to the left of the line of no effect indicated a favourable outcome for family intervention.

Unit of analysis issues

Studies increasingly employ cluster randomisation (such as randomisation by clinician or practice) but analysis and pooling of clustered data poses problems. Firstly, authors often fail to account for intra class correlation in clustered studies, leading to a unit-of-analysis error (Divine 1992) whereby P values are spuriously low, confidence intervals unduly narrow and statistical significance overestimated. This causes Type I errors (Bland 1997, Gulliford 1999).

Where clustering had not been accounted for in primary studies, we presented the data in a table, with a (*) symbol to indicate the presence of a probable unit of analysis error. In subsequent versions of this review we will seek to contact first authors of studies to obtain intra-class correlation co-efficients of their clustered data and to adjust for this using accepted methods (Gulliford 1999). Where clustering has been incorporated into the analysis of primary studies, we will also present these data as if from a non-cluster randomised study, but adjusted for the clustering effect.

We have sought statistical advice and have been advised that the binary data as presented in a report should be divided by a design effect. This is calculated using the mean number of participants per cluster (m) and the intraclass correlation co-efficient (ICC) (Design effect = 1+(m−1)*ICC) (Donner 2002). If the ICC was not reported we assumed it to be 0.1 (Ukoumunne 1999). If cluster studies had been appropriately analysed taking into account intraclass correlation coefficients and relevant data documented in the report, we synthesised these with other studies using the generic inverse variance technique.

Dealing with missing data

We excluded data from studies where more than 50% of participants in any group were lost to follow up (this did not include the outcome of ‘leaving the study early’). In studies with less than 50% dropout rate, people leaving early were considered to have had the negative outcome, For example, we treated those lost to follow up for the outcome of relapse as having relapsed in the analysis. We also treated suicide as relapse.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Firstly, we considered all the included studies within any comparison to judge for clinical heterogeneity. Then we visually inspected graphs to investigate the possibility of statistical heterogeneity. We supplemented this by using primarily the I2 statistic. This provides an estimate of the percentage of variability due to heterogeneity rather than chance alone. Where the I2 estimate was greater than or equal to 50%, we interpreted this as indicating the presence of considerable levels of heterogeneity (Higgins 2003).

Assessment of reporting biases

Reporting biases arise when the dissemination of research findings is influenced by the nature and direction of results. These are described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008). We are aware that funnel plots may be useful in investigating reporting biases, but are of limited power to detect small-study effects. We did not use funnel plots for outcomes where there were 10 or fewer studies, or where all studies were of similar sizes. In other cases, where funnel plots were possible, we sought statistical advice in their interpretation.

Data synthesis

Where possible, we used a fixed-effect model for analyses. We understand that there is no closed argument for preference for use of fixed-effect or random-effects models. The random-effects method incorporates an assumption that the different studies are estimating different, yet related, intervention effects. This does seem true to us, however, random-effects does put added weight onto the smaller studies - those trials that are most vulnerable to bias.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

When we found heterogeneous results, we investigated the reasons for this. Where heterogeneous data substantially altered the results and we identified the reasons for the heterogeneity, we did not summate these studies in the meta-analysis, but presented them separately and discussed them in the text.

Sensitivity analysis

Earlier versions of this review did not undertake any sensitivity analyses. This 2010 update also had not pre-planned any. However, because we have added so many new studies from China, and because of concern regarding the quality of trials from China (Wu 2006), we decided to undertake a sensitivity analysis testing, for the primary outcomes, to determine whether addition of the Chinese trials did have any substantial effect on the overall results.

RESULTS

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies.

For substantive descriptions of studies, please see Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies

Results of the search

1. The search

We found 855 references from 327 studies during the September 2008 search. In earlier searches, the 2002 update search yielded 1078 citations, and the June 2005 update identified 104 citations.

Included studies

1. Included trials

We were able to include 53 studies in total; this includes 21 added in the 2010 update.

2. Methods

All trials were described as ‘randomised’. Hogarty 1997, used a quasi-random method by allocating (‘on alternate weeks or months’) participants before they were admitted. The demographic data suggests that this process resulted in evenly balanced groups so we have included data, although they must be viewed with caution. Also, Gong 2007 and Liu 2003 used a quasi-randomised method of allocation. Ran 2003 block randomised participants into clusters using six different townships as units. Chen 2005 also used a cluster randomised design but did not report the number of clusters used. Szmukler 2003 (unpublished data) reports using an exploratory randomised controlled trial to evaluate the effectiveness of a carers intervention, using permuted blocks with varying block sizes and sample stratification. The majority of studies did not describe the method used to randomly allocate participants to treatment. However, some studies reported using computer generated randomisation, or block randomisation to achieve balanced groups. Carra 2007 described concealment of allocation by the use of an external statistician who was not involved in enrolling participants and was responsible for the method of sequence generation; all other included studies did not describe how sequence generation was concealed from the investigators and participants, and doubt remains as to how impervious all methods of allocation are to the introduction of bias.

Most trials did not achieve full blindness although many studies attempted to single blind at least some measurements (Barrowclough 2001; Falloon 1981; Goldstein 1978; Leavey 2004; Leff 1989;Linszen 1996; Merinder 1999; Tarrier 1988; Vaughan 1992; Xiong 1994; Zhang 1994).

3. Length of treatment

Length of treatment varied from six weeks (Bloch 1995; Goldstein 1978) to three years (Hogarty 1997). Hogarty 1997 also followed participants up for an additional three years.

4. Setting

Studies were conducted in Australia (two trials), Canada (one trial), Europe (12 trials), the People’s Republic of China (28 trials) and the USA (10 trials).

5. Participants

Participants in all the included trials (except Szmukler 2003 and Leavey 2004) were diagnosed as having schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Most studies used structured clinical assessments to determine the diagnosis (DSM 20 studies, CCMD 15 studies, ICD-10 seven studies, RDC two studies, New Haven Index one study, and PSE six studies). Szmukler 2003 included more than 80% with a diagnosis of schizophrenia-like illnesses, whilst the remainder suffered from bipolar affective disorder, or psychotic depression. Leavey 2004 included people described as having a psychotic illness. Overall, the age of participants ranged from 16 to 80 years. Of those studies which reported the sex of the participants, most included both men and women, although Glynn 1992, Liu 2007, Zhang 1994, and Zhang 2006a included only male patients. Patients had varied histories. Most studies involved families whose relatives had had multiple admissions, although three trials did involve substantial proportions of people with first episodes of illness (Goldstein 1978; Linszen 1996; Zhang 1994).

6. Interventions

6.1 Intervention group

All participants received family interventions and some had an educational component. Thirteen trials included family therapy in the presence of patients (Barrowclough 2001; De Giacomo 1997; Dyck 2002; Falloon 1981; Glynn 1992; Goldstein 1978;Herz 2000; Leff 1982; Leff 2001; Linszen 1996; Mak 1997;Xiong 1994; Zhang 1994) whilst eight restricted the groups to relatives (Bloch 1995; Buchkremer 1995; Chien 2004; Hogarty 1997; Leavey 2004; Posner 1992; Tarrier 1988; Vaughan 1992). Szmukler 2003 conducted family sessions mostly without the patient being present. Overall, the main aim of the family-based interventions, when reported, was to improve family atmosphere and reduce relapse of schizophrenia.

In addition to ‘standard’ family intervention (i.e. schizophrenia education and behavioural modification), the family intervention groups used other non-pharmacological approaches as part of their strategy. Barrowclough 2001 used motivational interviewing and cognitive behavioural intervention. Falloon 1981 provided 24-hour support for the family therapy group. Goldstein 1978 utilised a ‘crisis-orientated’ family intervention as part of the family intervention and Hogarty 1997 incorporated relaxation training for the intervention group and educated the ‘family’ on stressors for schizophrenia and prodromal symptoms. Role-play was used by Tarrier 1988 as a means of educating family members on how to manage schizophrenia, whereas Vaughan 1992 incorporated homework exercises for the family members.

6.2 Comparison group

The control groups were all given standard care or usual level of care that involved pharmacological interventions. Bloch 1995 provided the control group with a single session discussion about the study, and also gave participants educational material describing schizophrenia. Leff 2001 gave two sessions of education about schizophrenia to the control group. Szmukler 2003 provided a single one-hour session for the control group in which the study was described and the carers discussed their problems; carers were also provided with the same written and video information as the intervention group. Further measures were employed by Falloon 1981 who used supportive psychotherapy for the control arm of the study. Linszen 1996 and Merinder 1999 provided psychosocial support in an individualised context without family involvement.

7. Outcomes

Data we were able to extract included the outcomes of death, mental state, compliance (including compliance with medication and leaving the study early), quality of life, social functioning and measures of family functioning. Ran 2003 reported data as if from a non-cluster randomised study; the analyses were based on the numbers of individual families, with no account taken of the clustering effect. We sought statistical advice from the MRC Biostatistics Unit, Cambridge, UK. Dr Julian Higgins advised that the binary data as presented in the report should be divided by a ‘design effect’ and that this should be calculated using the mean number of families in the groups (m) and the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) (Design effect = 1+(m−1)*ICC). We contacted Dr Ran to obtain the ICC. Dr Ran kindly replied but ICC values were not available, so we assumed this to be 0.1 (Ukoumunne 1999). We have listed scales below that provided data for the review.

7.1 Global state

7.1.1 Global Assessment of Functioning - GAF

The GAF (APA 1987) allows the clinician to express the patient’s psychological, social and occupational functioning on a continuum extending from superior mental health, with optimal social and occupational performance to profound mental impairment when social and occupational functioning are precluded. Ratings are made on a scale of 0 to 90. Higher scores indicate a better outcome. Barrowclough 2001, Merinder 1999 and Xiong 1994 reported data from this scale.

7.2 Mental state

7.2.1 Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale - BPRS

The BPRS is an 18-item scale measuring positive symptoms, general psychopathology and affective symptoms (Overall 1962). The original scale has 16 items, but a revised 18-item scale is commonly used. Scores can range from 0-126. Each item is rated on a seven-point scale varying from ‘not present’ to ‘extremely severe’, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms. The BPRS was used in Linszen 1996, Fernandez 1998, Merinder 1999, Xiong 1994 and Zhang 1994 as part of the definition of relapse, and Magliano 2006, Merinder 1999 and Xiong 1994 reported BPRS mental state scores.

7.2.2 Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale - PANSS

This scale was developed to evaluate the positive, negative and general symptoms in schizophrenia (Kay 1987). It has 30 items, and each of these can be defined on a seven-point scoring system varying from one (absent) to seven (extreme). The scale can be divided into three sub-scales for measuring the severity of general psychopathology, positive symptoms (PANSS-P) and negative symptoms (PANSS-N). Higher scores indicate more symptoms. This scale was used by Barrowclough 2001, Dai 2007 and Liu 2003 to monitor treatment changes in schizophrenia.

7.2.3 Frankfurt Complaint Inventory - FBF-3

This is a 98-item self-application questionnaire in which the patient assesses the presence of subjective complaints on 10 clinical scales (loss of control, simple perception, complex perception, speech, cognition and thought, memory, motor behaviour, loss of automatisms, anhedonia, and anxiety and irritability due to stimuli overload) (Süllwold 1986). Higher scores indicate greater symptomology. A Spanish version of this scale (Jimeno 1996) was used in Fernandez 1998.

7.2.4 Insight Scale - IS

This is an eight-item questionnaire (Birchwood 1994). Three factors are scored: awareness of illness; need for treatment; and attribution of symptoms on a three-point scale. Higher scores indicate improvement in insight. This was used in Merinder 1999 to assess insight into psychosis and need for treatment.

7.2.5 Symptom Checklist 90 - SCL-90

The SCL-90 is a self-report clinical rating scale of psychiatric symptomatology (Derogatis 1976). It consists of 90 items, with 83 items representing nine sub-scales: somatization (n = 12 items), obsessive-compulsive (n = 10 items), interpersonal sensitivity (n = 9 items), depression (n = 13 items), anxiety (n = 10 items), angerhostility (n = 6 items), phobic anxiety (n = 7 items), paranoid ideation (n = 6 items) and psychoticism (n = 10 items). Seven additional items include disturbances in appetite and sleep. The SCL-90 also utilises three global distress indices: Global Severity Index (GSI), Positive Symptom Distress Index (PSDI), Positive Symptom Total (PST). Items are rated on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from “not at all distressing” (0) to “extremely distressing” (4), with higher scores indicating greater symptomatology. Li 2005a reported data from this scale.

7.2.6 Present State Examination - 9th Edition - PSE

This is a clinician-rated scale measuring mental status (Wing 1974). It rates 140 symptom items, which are combined to give various syndrome and sub-syndrome scores. Higher scores indicate greater clinical impairment. Tarrier 1988 and Vaughan 1992 used the PSE to help define relapse.

7.2.7 Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms - SANS

This scale was used in Bradley 2006 and Xiong 1994 to assess negative symptoms (Andreasen 1982). This is a six-point scale, providing a global rating of the following negative symptoms: alogia; affective blunting; avolition-apathy; anhedonia-asociality and attention impairment. Higher scores indicate more symptoms.

7.2.8 Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms - SAPS

This scale was used in Xiong 1994 to assess positive symptoms (Andreasen 1982). This is a six-point scale providing a global rating of positive symptoms such as delusions, hallucinations and disordered thinking. Higher scores indicate more symptoms.

7.3 Social functioning

7.3.1 Health of the Nation Outcome Scale - HoNOS

The HoNOS scale is used to rate various aspects of mental and social health, on a scale of 0-4 (Amin 1999). It is designed to be used by clinicians before and after interventions, so that changes attributable to the interventions can be measured. Higher scores indicate a worse outcome. Bradley 2006 reported data from this scale.

7.3.2 Social Disability Screening Schedule - SDSS

THE SDSS is a Chinese simplified version of the World Health Organization’s Disability Assessment Schedule and assesses 10 different aspects of social functioning (WHO 1988). Higher scores indicate a worse outcome. Dai 2007 and Tan 2007 reported data from this scale.

7.3.3 Social Functioning Scale - SFS

This scale (Birchwood 1990) was used in Barrowclough 2001, Fernandez 1998 and Leff 2001 to measure the ability of people with schizophrenia to function in the community.

7.4 Family outcome

7.4.1 Coping with Life Events and Difficulties Interview - COPI

A semi-structured interview with 29 items reflecting the carer’s subjective response or style of coping with a severe event or marked difficulty in terms of problem tackling, and cognitive and emotional responses (Bifulco 1996). A high score is poor. Szmukler 2003 reported data from this scale.

7.4.2 Family Support Service Index - FSSI

The Family Support Service Index measures the formal support services needed and their usage by psychiatric patients and their families (Heller 1991). Higher scores indicate a greater need for family support. This index was used by Chien 2004.

7.4.3 Family Assessment Device - FAD

The Family Assessment Device assesses multiple dimensions of family functioning for patients with mental disorders and other conditions (Epstein 1983). It consists of 60 items, each of which is rated on a four-point Likert scale (from 1= strongly disagree, to 4= strongly agree) along seven dimensions: problem solving; communication; roles; affective responsiveness; affective involvement; behavioural control and general functioning. The total scores range from four to 28, with higher scores reflecting poorer family functioning. This scale was used by Chien 2004.

7.4.4 Family Burden Interview Schedule - FBIS

The Family Burden Interview Schedule is a 25-item semi-structured interview schedule to assess the burden of care placed on families of a psychiatric patient living in the community (Pai 1981). It comprises six categories of perceived burden (with 2-6 items in each category): family finance, routine, leisure, interaction, physical and mental health. The items are rated on a three-point Likert scale (0 = no burden, 1 = moderate burden and 2 = severe burden). The total scores ranged from 0 to 50 with higher scores indicating higher burden or care. This scale was used by Chien 2004.

7.4.5 Camberwell Family Interview - CFI

The CFI is a measure of expressed emotions, of criticisms and of unfavourable attention (Vaughn 1976). The CFI is a long, complex and difficult structured interview for which extensive training is needed. Reliability is usually acceptable, but for ‘warmth’ it is low even after extensive training. Yet it seems to be superior to most alternative measures of expressed emotions and family atmosphere. The ratings are undertaken from videos of family interaction and focuses on the number of critical comments expressed. A high score is poor. Leff 2001 and Tarrier 1988 reported data from this scale.

7.4.6 Clinical Interview Schedule Revised - CIS-R

This scale provides a global score of psychological morbidity (Lewis 1992). The main purpose of the CIS-R is to identify the presence of neurosis and to establish the nature and severity of neurotic symptoms. There are 15 sections to the scale covering: somatic symptoms; fatigue; concentration and forgetfulness; sleep problems; irritability; worry about physical health; depression; depressive ideas; anxiety; phobias; panic; compulsions; obsessions and overall effects. A high score is poor. Szmukler 2003 reported data from this scale.

7.4.7 Experience of Care giving Inventory - ECI

A self-report measure of the experience of caring for a relative with a serious mental illness, with care giving conceptualised in a stress-appraisal-coping framework (Szmukler 1996). A 66-item version taps dimensions of care giving distinct from, but linked with, coping and psychological morbidity. This scale was dichotomised by the authors of Bloch 1995. A high score is poor. Continuous data from this scale were reported in Szmukler 2003.

7.4.8 Family Questionnaire - FQ

The Family Questionnaire is a brief self-rating scale for assessing the expressed emotional status of relatives of people with schizophrenia (Wiedemann 2002). The scale comprises 20 questions on a four-point scale with a low score indicating a better outcome, and was used by Merinder 1999.

7.4.9 Verona Service Satisfaction Scale - VSSS

This is a self-administered questionnaire that assesses satisfaction with services on a five-point scale across seven dimensions: overall satisfaction; professional skills and behaviour; information; access; efficacy; types of intervention and relatives’ involvement (Ruggeri 1993). The five points are 0-1 = “terrible”, 1-2 = “mostly dissatisfied”, 2-3 = “mixed”, 3-4 = “mostly satisfied”, 4-5 = “excellent”. This scale was used by Merinder 1999.

7.4.10 Ways of Coping - WOC

This scale describes cognitive and behavioural strategies for coping with stressful events over the preceding month (MacCarthy 1989b). Higher scores indicate poorer coping. This scale was dichotomised by the authors of Bloch 1995.

7.4.11 Self Evaluation and Social Support Schedule - SESS

This is a structured interview schedule to assess availability of confidants (Andrews 1991). It contains detailed questions about the relationship with the primary confidant, including closeness, confiding, intimacy, dependency, and negative interactions. This involves three to four hours administration time and extensive interviewer and rater training. It is not appropriate for large-scale epidemiologic studies. Szmukler 2003 reported data from this scale.

7.4.12 Adaptability, Partnership, Growth, Affection, and Resolve - APGAR

This scale assesses a family member’s perception of family functioning by examining his/her satisfaction with family relationships (Smilkstein 1978).The measure consists of five parameters of family functioning: Adaptability, Partnership, Growth, Affection, and Resolve. The response options were designed to describe frequency of feeling satisfied with each parameter on a 3-point scale ranging from 0 (hardly ever) to 2 (almost always).The items were developed on the premise that a family member’s perception of family functioning could be assessed by reported satisfaction with the five dimensions of family functioning listed above. Higher scores indicate better family functioning. Du 2005 reported data from this scale.

7.5 Behaviour

7.5.1 The Nurses’ Observation Scale for Inpatient Evaluation - NOSIE

The Nurses’ Observation Scale for Inpatient Evaluation (NOSIE) is a highly sensitive ward behaviour rating scale (Honigfeld 1965a). Final item selection includes the best 30 of an original pool of 100 items. Higher scores indicate a poor outcome. Dai 2007 reported data from this scale.

Two summary scales were used:

-

Confidents or Very Close Others (Brown 1986)

The Confidents or Very Close Others summary scale assesses the relationship between the carer and two core contacts, i.e. the first two people a carer would confide in about a problem. Seven questions cover degree of confiding, emotional support, absolution from guilt, practical support, negative verbal and behavioural response and perception of helpfulness. Szmukler 2003 reported data from this scale.

-

General Community Support (Brown 1986)

The General Community Support subscale comprises five questions on the broader network or more diffuse social contacts of the carer, e.g. non-core relatives and acquaintances including possible neighbours, local shop keepers, pub-owners and church personnel. An estimate is made of the number of people having a positive or negative attitude towards the patient’s illness and the degree of practical or emotional support given or negative response made. Szmukler 2003 reported data from this scale.

7.6 Quality of Life

7.6.1 Quality of Life - QoL

This is a 21 item scale which measures both quality of life and negative/deficit symptoms of schizophrenia in adults and utilises a semi-structured interview (Heinrichs 1984). The categories covered are physical functioning, occupational role, interpersonal relationships and psychological functioning. Each item is rated on a seven-point scale, which requires the clinical judgement of the interviewer. Data from this scale were reported by Bradley 2006 and Shi 2000.

7.7 Redundant data

A large number of scales were used in the studies. Many measures, even those within included studies, were reported in such a way as to render the results unusable. Data were either not reported at all or did not distinguish treatment groups. Where data were presented it was common not to have means or variances reported or inaccurate P values presented.

Excluded studies

1. Excluded studies

We excluded 79 studies. Of these, 21 (28%) were not randomised and 23 (30%) involved people in hospital or interventions that could not be described as family intervention compared with standard care. Thirty-one studies (42%) did not report outcome data or presented it in a form that we could not use.

2. Awaiting assessment

No studies are awaiting assessment.

3. Ongoing studies

We are not aware of any ongoing studies.

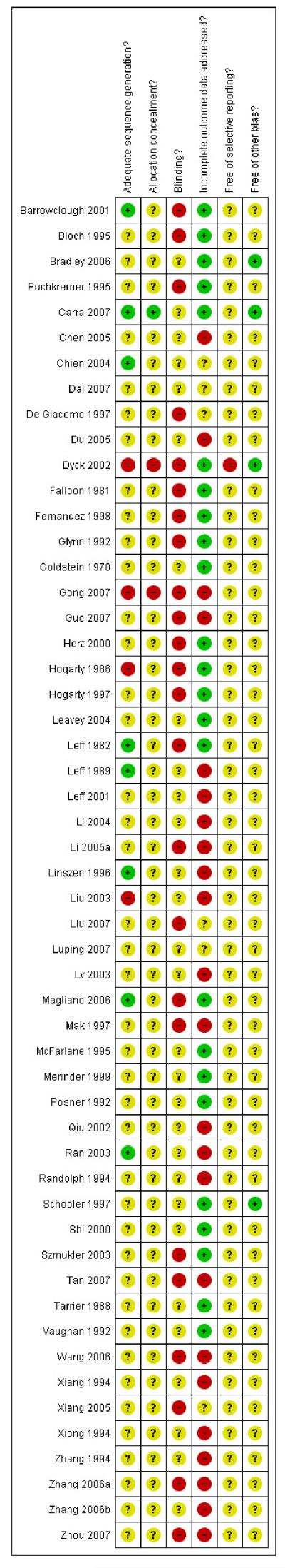

Risk of bias in included studies

Only eight studies, from the total of 53, described the method of randomisation, and only one was explicit about the method of allocation concealment. Blinding was not always possible for family intervention, although few studies attempted, or at least failed to report whether the investigators assessing the participants were blind to treatment allocation. Similarly, study attrition was often omitted from the results, yet it is unlikely that group sizes remained constant throughout the investigation period. We did not have access to the included studies protocols, and were therefore unable to judge whether various tests of effectiveness had been omitted from the published findings. The effect of these potential biases is that the outcomes in this review may overestimate effects.

Allocation

Random allocation to treatment group was only described in eight of the 53 included studies, although all included studies were stated to be randomised. Three trials used a quasi-randomisation technique (Gong 2007; Hogarty 1997; Liu 2003) and it is possible that these studies are unacceptably open to the introduction of bias at the point of allocation. Only Carra 2007 described measures to conceal the sequence of allocation from participants and investigators. Ran 2003 was a cluster randomised trial. This methodology is likely to become more common but should be accompanied by reporting of the intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC). We have been forced to estimate this coefficient and, as a result, may be underemphasising the importance of this study.

Blinding

Trialists were aware of the possibility of the introduction of observer bias by not blinding the raters to the group to which people or families were allocated. Ten studies reported that no form of blinding was used (Bloch 1995; Buchkremer 1995; De Giacomo 1997; Fernandez 1998; Glynn 1992; Herz 2000; Leavey 2004;Leff 1982; Shi 2000; Szmukler 2003). A further 16 studies did not mention whether blinding had been used. Hogarty 1997 was also not blinded but considerable efforts were made to ensure that decisions, for example regarding relapse, were both reliable and valid. In other studies an attempt was made to ensure that raters were blind for part or the entire recording of outcome. No study tested the integrity of this blinding.

Incomplete outcome data

Study attrition was often not reported and these trials may have carried forward the last observation of the participants, which may have introduced some uncertainty into the results, as it is unlikely that the participants clinical state remained stable.

Selective reporting

We identified no under reporting of outcomes that had been collected by the trialists, although we did not have access to the protocols of the studies to determine whether all the outcome measures were reported.

Other potential sources of bias

A large number of Chinese trials were added to this review. Evidence has emerged that many trials from the People’s Republic of China which were stated to be randomised are not (Wu 2006). We did not contact the authors to verify the process by which they randomised but took the descriptions and statements as being correct. Nor did we identify any overt bias in the results. However, inclusion of these studies may increase the risk of biased data favouring family intervention.

Effects of interventions

I. Comparison I. Any family based interventions (more than five sessions) versus standard care

More information on this comparison is available in Summary of findings for the main comparison.

I.I Service utilisation

1.1.1 Hospital admission

Hospital admissions at six months were equivocal (n = 132, three RCTs, RR 0.85 CI 0.4 to 1.7). In the 2002 update of this review, the evidence that family intervention reduces hospital admission at one year was equivocal, and this was a change from earlier versions of the review which found family intervention to significantly reduce hospital admission (Mari 1996). In this 2010 update, however, there is again some suggestion that family intervention does significantly reduce hospital admission at one year (n = 481, eight RCTs, RR 0.78 CI 0.6 to 1.0, NNT 8 CI 6 to 13). Longer follow up (to 18 months) also finds that family intervention does significantly reduce admission (n = 228, three RCTs, RR 0.46 CI 0.3 to 0.7, NNT 4 CI 3 to 8), although data beyond that time (two years, n = 145, five RCTs, RR 0.83 CI 0.7 to 1.1; three years, n = 122, 2 RCT, RR 0.91 CI 0.7 to1.2) are equivocal. Removing trials from China from the analyses for this outcome made no substantive difference.

1.1.2 Days in hospital

The total number of days spent in hospital at three months was significantly lower in the family intervention group (Chien 2004, n = 48, MD −6.67 CI −11.6 to −1.8). Xiong 1994 also reported data for the time spent in hospital. These data are not normally distributed (skewed) and are not presented on a graph. In this study the 33 people in the intervention group spent an average of 7.9 days in hospital by the end of the 12-month follow-up period (SD 22.4). The 28 people in the control group spent an average of 24 days in hospital (SD 43.6). These findings were reported by the authors to be statistically significantly different (P = 0.03), favouring the group given family intervention.

1.2 Global state

1.2.1 Relapse

Please see Analysis 1.4.

For the purposes of this review, suicide is considered as a relapse. There is, however, no universally accepted definition of relapse (please see Characteristics of included studies). Some definitions required the recurrence of symptoms for patients with full remission at discharge, and others required a deterioration of symptoms for people who presented residual symptoms at baseline assessment. Finally, some studies stipulated that relapse was indicated by a managerial event such as hospitalisation or substantial change of medication.

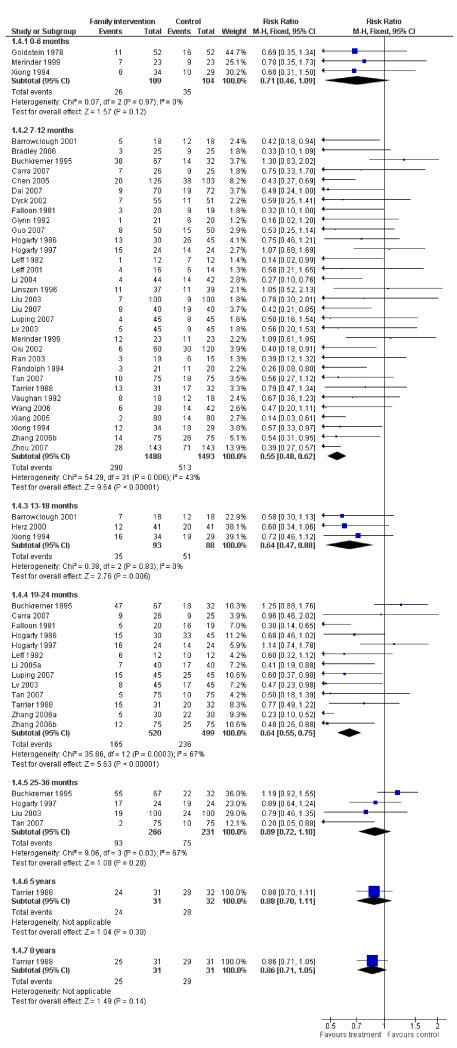

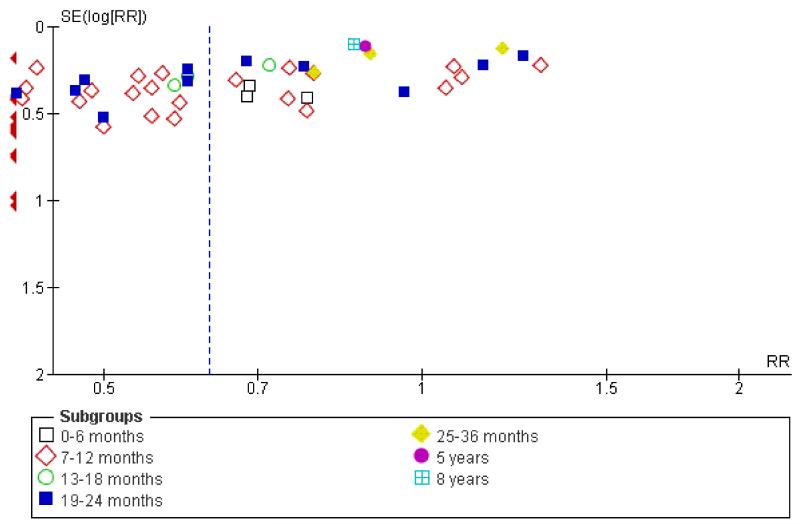

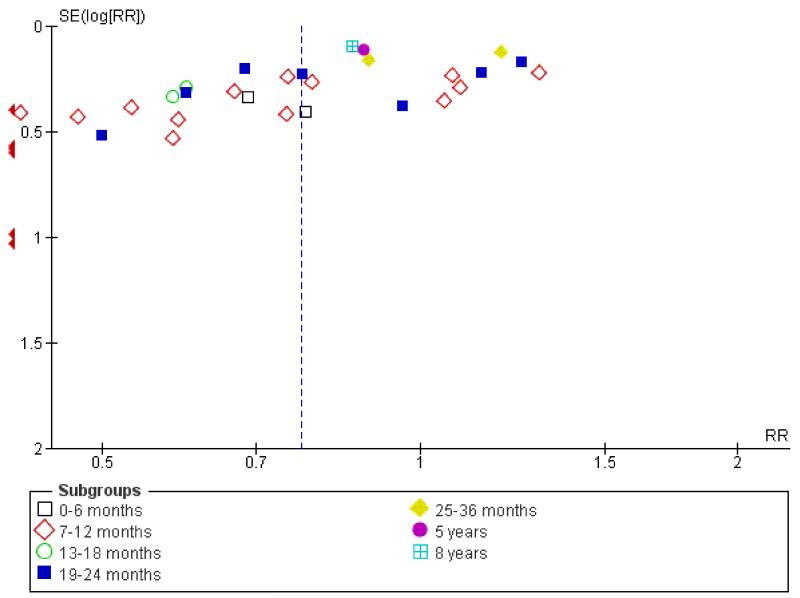

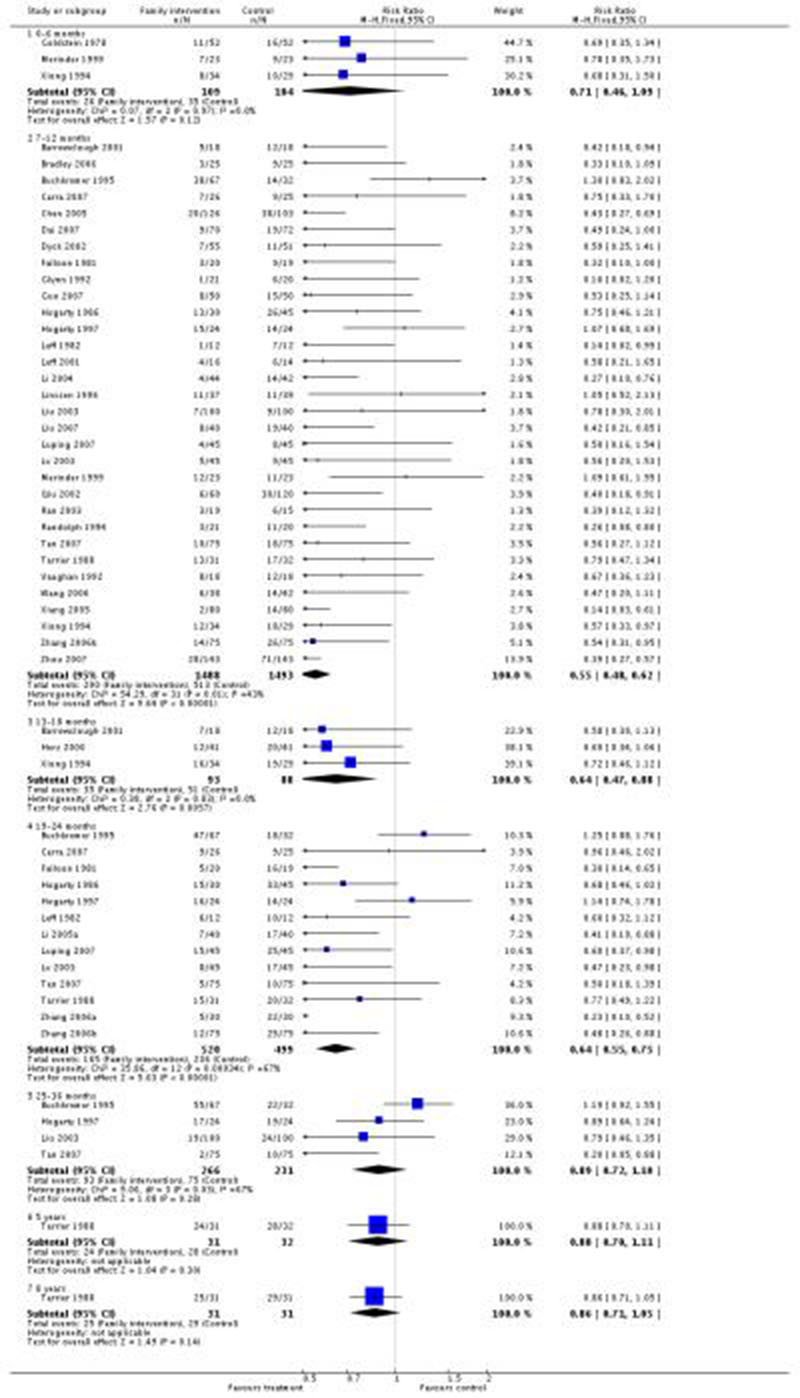

Family intervention did not reduce the rate of these ‘relapse events’ at six months (n = 213, 3 RCTs, RR 0.71 CI 0.5 to 1.1). By 12 months, family intervention did reduce relapse events (n = 2981, 32 RCTs, RR 0.55 CI 0.5 to 0.6, NNT 7 CI 6 to 8), as well as at 18 months (n = 181, 3 RCTs, RR 0.64 CI 0.5 to 0.9, NNT 5 CI 4 to 15) and at 24 months (n = 1019, 13 RCTs, RR 0.64 CI 0.6 to 0.8), although data are heterogeneous (I2 = 67%). When trials from China are removed findings tend to be a little less positive (Figure 1) but not dramatically so. Funnel plots of this outcome - before (Figure 2) and after (Figure 3) removal of the Chinese studies does not really suggest that there is a ‘small study bias’ operating.

Figure 1. Forest plot of comparison: 1 ANY FAMILY-BASED INTERVENTIONS (> 5 sessions) vs STANDARD CARE, outcome: 1.4 Global state: 1. Relapse (without use of data from China).

Figure 2. Funnel plot of comparison: 1 ANY FAMILY-BASED INTERVENTIONS (> 5 sessions) vs STANDARD CARE, outcome: 1.4 Global state: 1. Relapse.

Figure 3. Funnel plot of comparison: 1 ANY FAMILY-BASED INTERVENTIONS (> 5 sessions) vs STANDARD CARE, outcome: 1.4 Global state: 1. Relapse (minus Chinese trials).

Data regarding relapse at three years are not significantly different (n = 497, 4 RCTs, RR 0.89 CI 0.7 to 1.1). Data from longer follow up (five and eight years) are, in each case, reported by a single small study, and are non-significant.

1.2.2 ‘Not improved’

Xiang 1994 and Ran 2003 continue to suggest significantly fewer people in the control group improved than in the family intervention group (n = 112, 2 RCTs, RR 0.40 CI 0.2 to 0.7, NNT 2 CI 2 to 4).

1.2.3 Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF)

Average endpoint scores on the GAF scale at one year (Barrowclough 2001, n = 32, MD −10.28 CI −20.3 to −0.2) were borderline significant (0.05) for family intervention. Average endpoint scores by two years also favoured family intervention (n = 90, 2 RCTs, MD −8.66 CI −14.4 to −2.9). Merinder 1999 reported mean change data after eight family intervention sessions and at 12 months. Both sets of data contain considerable skew and are not significantly different.

1.2.4 Self-reported psychiatric symptom scores (SCL-90)

Self-reported psychiatric symptom scores favoured family intervention (Li 2005a, n = 80, MD −22.01 CI −30.9 to −13.0) compared with the control group.

1.3 Mental state

1.3.1 Average scores - Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale

BPRS data favoured family intervention at one year (n = 170, 3 RCTs, MD −8.32 CI −10.9 to −5.7), although data were heterogeneous (I2 = 79%). BPRS negative scores (n = 62, 1 RCT, MD −0.30 CI −0.9 to 0.3) are equivocal. We found, skewed, BPRS change data were not significantly different (n = 156, 3 RCTs, MD −0.30 CI −0.8 to 0.2). In Merinder 1999 we found no significant difference in the short term skewed data.

1.3.2 Average scores - Positive and Negative Symptom Score

We found PANSS endpoint total scores (n = 174, 2 RCTs, MD −7.90 CI −11.9 to −3.8) favoured family intervention compared with the control group at one year. However, PANSS positive and negative scores were not significant. PANSS general psychopathology data favoured family intervention (Dai 2007, n = 142, MD -3.60 CI -5.8 to -1.4). Barrowclough 2001 reported 18-month outcome data, and we found PANSS total and positive scores were not significant. But PANSS negative scores did favour the family intervention (n = 29, MD −5.23 CI −8.4 to −2.0) group. One Chinese study (Liu 2003, n = 149) reported data at three years, and we found PANSS total scores (MD −10.20 CI −13.6 to −6.9), PANSS positive scores (MD −2.60 CI −4.1 to −1.1) and PANSS negative scores (MD −3.70 CI −4.9 to −2.5) favoured family intervention. We found PANSS positive change scores (Dai 2007, n = 142, MD −2.00 CI −3.5 −0.5) and PANSS negative change scores (Dai 2007, n = 142, MD −4.00 CI −5.8 to −2.2) favoured the family intervention group compared with the control group.

1.3.3 Average scores - SAPS/SANS

Xiong 1994 used Chinese versions of the SAPS and SANS scales. Data at 18 months however, were skewed for both, with the SANS-CV outcome not statistically significant, although the SAPS-CV outcome was significant (P = 0.03), favouring family intervention. Bradley 2006 also reported SANS endpoint scores, but the data were too skewed to report here.

1.3.4 Insight

Average change in general mental state scores for insight were only reported by Merinder 1999. Data for an unspecified period after eight sessions of family intervention and at one year were both equivocal.

1.3.5 Average scores - Frankfurt scale

Finally, Fernandez 1998 reported on the average endpoint score of the mental state rating scale, the Frankfurt Scale. Data were too skewed to present graphically. They were not statistically significant.

1.4 Behaviour

1.4.1 Average scores - Nursing observation (NOSIE)

We found NOSIE endpoint scores favoured the control group (Dai 2007, n = 142, MD 59.10 CI 54.6 to 63.6) compared with participants given family intervention. NOSIE positive factor scores also failed to show any benefit for the family intervention group (Dai 2007, n = 142, MD 33.40 CI 30.5 to 36.3) over the 12-month assessment period.

1.5 Compliance

1.5.1 Leaving the study early

No studies reported data for the short term (0 to 12 weeks). By three months, study attrition was occurring but was no greater for the family intervention group than for the control (n = 552, 7 RCTs, RR 0.92 CI 0.6 to 1.4). Results from seven months to one year were not significant (n = 733, 10 RCTs, RR 0.74 CI 0.5 to 1.0) but revealed a trend in favour of family intervention (P = 0.07). Loss to follow up from 13 months to two years (n = 887, 10 RCTs, RR 0.74 CI 0.6 to 1.0) favoured family intervention NNT 22 to prevent one participant leaving the study (CI not estimable). Long-term data from 25 months to three years favoured family intervention (n = 290, 3 RCTs, RR 0.42 CI 0.3 to 0.7, NNT 6 CI 5 to 10), but results for more than three years (Tarrier 1988, n = 63, RR 1.72 CI 0.7 to 4.2) were equivocal. Tarrier 1988 reported loss to follow-up data at eight years and we found no significant difference between groups (n = 63, RR 1.72 CI 0.7 to 4.2).

1.5.2 Compliance with medication

Compliance with medication improved for people whose relatives received family intervention (n = 695, 10 RCTs, RR 0.60 CI 0.5 to 0.7, NNT 6 CI 5 to 9).

1.5.3 Compliance with community care

No significant differences were found in compliance with community care at one year (Carra 2007, n = 29, RR 0.68 CI 0.4 to 1.1), or by two years (Carra 2007, n = 29, RR 0.85 CI 0.6 to 1.3).

1.5.4 Months on medication

The data on months taking medication are from a single study (Xiong 1994). This small study (n = 63) suggests that those receiving family therapy do stay on medication for longer, although no findings are statistically significant.

1.6 Adverse events - death

The majority of deaths were due to suicide. Of the 377 people in the studies that reported death as an outcome, 17 (5%) committed suicide. There were five deaths due to other causes. Family intervention had no clear effect on the numbers of people who killed themselves during the studies (n = 377, 7 RCTs, RR 0.79 CI 0.4 to 1.8). Personal communication with Professor Tarrier suggested that there might be a few more deaths in the long-term follow up of Tarrier 1988, but numbers and group of allocation have not been clarified.

1.7 Social functioning

1.7.1 Generally socially impaired

Falloon 1981 and Xiang 1994 report on a rating of overall social impairment up to nine months. Results suggest that family intervention does significantly reduce general social impairment (n = 116, 2 RCTs, RR 0.51 CI 0.4 to 0.7). Data are heterogeneous (I2 = 75%). We also found general social functioning scores (n = 90, 3 RCTs, MD −8.05 CI −13.3 to −2.8) favoured family intervention, however, again data are heterogeneous (I2 = 63%).

1.7.2 Work

The majority of the studies did not provide data for specific aspects of social functioning. Four, however, reported on employment. The results at one year are equivocal (n = 285, 5 RCTs, RR unemployed 1.06 CI 0.9 to 1.3) as are those at two years (Carra 2007, n = 51, RR 1.33 CI 0.8 to 2.1), and three years (Buchkremer 1995, n = 99, RR unemployed 1.19 CI 0.9 to 1.6). Xiang 1994 (n = 77) evaluated whether family intervention helped with a person’s abilities to perform work tasks. It did not (RR 0.31 CI 0.1 to 1.0). Similarly, Ran 2003 also reported no differences in a person’s ability to perform work tasks (n = 35, RR 1.68 CI 0.2 to 16.9). Xiong 1994 reported skewed data for months spent in employment. At the end of a year in this study, the 33 people in the intervention group spent an average of 5.6 months in employment (SD 5.0) compared with the 28 in the control group who spent 3.1 months employed (SD 5.1). This was statistically significant.

1.7.3 Living independently

Three studies reported whether or not patients whose families received family intervention were able to move towards more independent living. The results for this show a trend towards increased ability to live independently at one year (n = 164, 3 RCTs, RR 0.83 CI 0.7 to 1.0) but total numbers are small and the results are not statistically significant. Three-year data (Buchkremer 1995) also did not indicate increased ability to live independently for either group.

1.7.4 Imprisonment

A single small study reported on imprisonment (Falloon 1981, n = 39) and we found no clear effect of family intervention for this outcome (RR 0.95 CI 0.2 to 4.1).

1.7.5 Disability Assessment Scale

Only skewed data were available, and data suggest that participants given family intervention had worse levels of disability.

1.7.6 Social Disability Screening Schedule (SDSS)

Participants given family intervention for two years did not reveal any significant differences between groups (Tan 2007, n = 150, MD −0.51 CI −1.4 to 0.4) based on the Social Disability Screening Schedule. However, at three years, results favoured family intervention (n = 150, MD −1.94 CI −2.90 to −1.0). Further endpoint data favouring family intervention at one year were reported by Wang 2006, and contained wide confidence intervals. Bradley 2006 also reported skewed data from the HoNOS scales and data are added to other data tables.

1.8 Family outcomes

1.8.1 Ability to cope

Bloch 1995 reports on the families’ ability to cope. This is not clearly increased by the experimental intervention (n = 63, RR 0.79 CI 0.6 to 1.0). Falloon 1981 suggests that there is no difference in the ability of the patient to cope with the key relative within the family as a result of the intervention (n = 39, RR 1.11 CI 0.5 to 2.7). Regarding families’ ability to understand the patients’ needs, only Bloch 1995 reported this outcome and suggested that family intervention decreases poor understanding of patients’ needs (n = 63, RR 0.58 CI 0.4 to 0.9). Insufficient care or maltreatment by the family was reported by two studies, Xiang 1994 at six months and Ran 2003 at nine months. The results suggests a trend favouring family intervention, although this is not statistically significant (P = 0.06) and a larger study may have rendered the outcome significant (n = 111, 2 RCT, RR 0.49 CI 0.2 to 1.0).

Szmukler 2003 reported on continuous measures of coping by the carers (Coping with Life-events & Difficulties Interview). Coping skills were all equivocal (n = 49, MD effective coping −0.5 CI −1.9 to 0.9; MD ineffective coping 0.30 CI -0.7 to 1.3), with no benefit being shown for the carers in the intervention group compared with those in the control group.

In Chien 2004, using the Family Support Service Index scale, we found the family intervention group required significantly more support than the control group (n =48, MD 0.86 CI 0.2 to 1.5).Chien 2004 also reported data from the Family Assessment Device scale and we found those receiving family intervention had significantly better outcomes in family functioning (n = 48, MD −6.56 CI −10.50 CI −10.5 to −2.6).

1.8.2 Burden

In Chien 2004 we found participants given family intervention were perceived as less of a burden according to the Family Burden Interview Schedule (n = 48, MD −7.01 CI −10.8 to −3.3). Data from Xiong 1994 also suggests a significant reduction in the burden felt by family carers (n = 60, MD −0.4 CI −0.7 to −0.1). Carra 2007 reported dichotomous data (n = 51) on burden and all data were equivocal. Leff 2001 and Bradley 2006 reported continuous data for burden but these were skewed and are not reported in the text.

1.8.3 Expressed emotion within the family

In Hogarty 1986 we found the overall level of expressed emotion was equivocal. However, we found families given the intervention reported a statistically significant decreases in levels of over-involvement (Tarrier 1988, n = 63, RR 0.40 CI 0.2 to 0.7, NNT 3 CI 2 to 6) and criticism (n = 63, RR 0.44 CI 0.2 to 0.8, NNT 3 CI 3 to 9). Hostility was also significantly lower in the family intervention group (n = 87, 2 RCTs, RR 0.35 CI 0.2 to 0.7, NNT 3 CI 3 to 6). When we combined the results of three studies, significant findings in favour of family intervention for high expressed emotion became evident (n = 164, 3 RCTs, RR 0.68 CI 0.5 to 0.9) but data were heterogeneous (I2 = 68%). Leff 2001 reported equivocal results for expressed emotion on continuous scores, and skewed data on critical comments, and over-involvement. Merinder 1999 reported (skewed data) expressed emotion from the Family Questionnaire which were also equivocal. Knowledge Scores reported by Leff 2001 were skewed and could not be reported due to the wide variations around the mean.

1.8.4 Psychological morbidity of carers

Szmukler 2003 reported continuous data for this outcome. Data were skewed with no statistically significant difference between carers in the family intervention or standard care group.

1.8.5 Care giving

Szmukler 2003 provided data on the family’s experience of care giving. These data were also skewed and did not show clear differences between the experiences of the different groups of families.

1.8.6 Social support

Szmukler 2003 reported on the role of support given to carers by close confidants and the attitudes of people in the wider community. The data were too skewed to present graphically, but the study report stated that no significant differences were found between the two groups.

1.8.7 Stress of care giving

Szmukler 2003 reported on the amount of stress experienced, but data were skewed and are not presented here.

1.8.8 Change in expressed emotion by the caregiver

Merinder 1999 reported on change in expressed emotion by caregivers but only skewed data were available, and are not presented.

1.8.9 Satisfaction

Merinder 1999 (n = 46) rated the satisfaction of carers and patients using the Verona Service Satisfaction Scale. All data are skewed and difficult to interpret. None are statistically significant but there is a consistent impression that carers in the family intervention group are more satisfied with care than those allocated to standard care.

1.8.10 Family APGAR

We found family APGAR (Du 2005, n = 146, MD −2.90 CI −3.4 to −2.4) scores favoured participants given family intervention during 12 months’ assessment.

1.8.11 Quality of life

In Shi 2000 we found families in the family intervention group had significantly higher level of quality of life than family members of the control group (n = 213, MD 19.18 CI 9.8 to 28.6) at the two-year endpoint. However, no significant differences in quality of life were found one small study (n = 50) at one year (MD −5.05 CI −15.4 to 5.3).

1.9 Economic analyses

Falloon 1981, Tarrier 1988 and Xiong 1994 include an economic analysis. In Falloon 1981 and Xiong 1994 direct and indirect costs of community management to patients, families, health, welfare, and community agencies were recorded, while Tarrier 1988 restricted the economic analysis to direct costs. Falloon 1981 suggests that, after one year, the overall costs of the family approach were approximately 20% less than those of the control condition (Cardin 1985). In Tarrier 1988 there was a decrease of 27% in the mean cost per patient in family intervention group. In Xiong 1994 the intervention resulted in a net saving of 58% of the per capita yearly income (in China), but the proportion of this saving that directly benefited the family would vary depending on whether or not the patient had medical insurance and received work disability payment.

2. COMPARISON 2. BEHAVIOURAL FAMILY-BASED versus SUPPORTIVE FAMILY BASED INTERVENTIONS (>5 sessions)

2. Comparison 2. Behavioural family-based versus supportive family-based interventions (more than five sessions)

2.1 Service utilisation

2.1.1 Hospital admission

The single large study in this comparison, Schooler 1997, reported equivocal results at two years (n = 528, RR 0.98, CI 0.9 to 1.1).

2.2 Global state

Schooler 1997 rated the stability of a person’s global state. By six months there was no difference in the numbers of people being rated as unstable (n = 528, RR 1.08 CI 0.9 to 1.3).

2.3 Compliance: leaving the study early or poor compliance with treatment protocol

Seventy-nine percent of people left Schooler 1997 early or did not/could not adhere to the treatment protocol. Family intervention did not change this attrition (n = 528, RR 0.96 CI 0.9 to 1.1).

3. Comparison 3. Group family-based interventions versus individual family-based interventions (more than five sessions)

3.1 Global state

Leff 1989 and McFarlane 1995 provide data for relapse at one year (n = 195, 2 RCTs, RR 0.70 CI 0.4 to 1.2). At two years results were also not statistically significant (n = 197, 3 RCTs, RR 0.71 CI 0.5 to 1.1). McFarlane 1995 reported data for the outcome of ‘more than one relapse’ between 19 and 24 months. Wide confidence intervals render the result equivocal (n = 172, RR 0.71 CI 0.3 to 1.5).

3.2 Compliance

Leff 1989 and McFarlane 1995 report data for people leaving the study early with no clear difference between group-based and individual-based family intervention techniques (n = 195, 2 RCTs, RR 1.35, CI 0.8 to 2.2). Only McFarlane 1995 provided data for poor compliance with medication and these too were equivocal (n = 172, RR 1.0 CI 0.5 to 2.0).

3.3 Social functioning

Leff 1989 found a statistically favourable outcome for the individual family based intervention. More people allocated to individual family intervention were able to live independently compared with those who had been randomised to the group-based family intervention (n = 23, RR 2.18 CI 1.1 to 4.4).

3.4 Family outcomes

Leff 1989 reported on the amount of expressed emotion by relatives. Data comparing the interventions are equivocal (n = 23, RR 0.94 CI 0.5 to 1.9), although the authors reported a significant (P < 0.05) reduction in expressed emotion between baseline and at two years.

DISCUSSION

Summary of main results

1. Comparison 1. Any family-based interventions (more than five sessions) versus standard care

1.1 Service utilisation

Previous versions of this review produced equivocal data suggesting that family intervention does not reduce hospital admission by one year compared with standard care (seven RCTs, n = 374 families) (Pharoah 2000; Pharoah 2003). Even earlier versions suggested that family intervention did reduce hospital admission significantly more than standard care alone (Mari 1994a; Mari 1996). Again, in this 2010 update, the evidence suggests that family intervention significantly reduces hospital admission at one year, with one patient out of every eight treated with family intervention prevented from hospitalisation compared with standard care.

We do recognise the enormous difficulty of conducting randomised trials in this area, but, nevertheless as family intervention is widely used, it could be expected that its implementation should be based on more stable and convincing data than these. The data reported by Falloon 1981 (n = 39) Xiong 1994 (n = 63) and Zhang 1994 (n = 83) strongly favours family intervention, and when these studies are excluded from the meta-analysis hospital admission becomes non-significant at all time points. Days spent in hospital is reduced but this outcome is based on one small study (Chien 2004).

1.2 Global state

Despite the definition of relapse varying across studies, we felt that the summation of data to be reasonable as definitions in routine clinical practice may also vary. Inclusion of the cluster randomised trial Ran 2003, with data managed as described in the ‘Unit of analysis issues’ section above also made little difference to the overall finding. People allocated to family interventions may relapse less compared with those in the standard care group. It is a concern that these findings may contain an element of small study bias (Figure 1). Small, less positive studies may remain unpublished or inaccessible. This must weaken the findings but currently the best available evidence suggests that the approximate number of families needed to be given family intervention in order to avoid one relapse at the end of a year is about seven. These figures could be seen as supportive of the general use of family intervention or prohibitive of its introduction into everyday use. Data from the People’s Republic of China (Xiang 1994), support the impression of better overall global improvement in the family intervention group compared with the control. Continuous scores from the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) and the (SCL-90) also support this in favour of family intervention.

1.3 Mental state

Participants and trialists invested time and effort rating mental state using several scales. It is difficult to know if the result justifies the effort on the part of everyone concerned. The overall impression is mixed with both favourable and equivocal findings for family intervention. Some agreement across trials on design of study could have rendered these data more useful.

1.4 Behaviour

Family intervention was not beneficial in terms of behavioural measures from the NOSIE scale compared with those patients given standard care, although this result is based on a single study (Dai 2007).

1.5 Compliance

About 14% of participants left the study before completion by one year. The addition of several Chinese trials has resulted in retention rates further improving from the finding reported previously (17%). Compared with other trials for the care of people with schizophrenia, this level of follow up is excellent (Thornley 1998). Family intervention did not seem to promote or hinder this attrition. The experimental intervention did, however, promote compliance with medication. It can be speculated that it is by this means that family intervention has its main effect. Hogarty 1997 did suggest that although compliance with medication was indeed improved by family intervention, this did not fully account for the findings favouring family intervention. In the short term, however, compliance with medication is predictive of a better outcome (Dencker 1986) and this could well be the means by which family intervention contributes to decreased relapse.

1.6 Adverse events - death

That 5% of the 377 people in the studies which reported death as an outcome committed suicide during the follow-up period suggests that these studies were dealing with a disturbed group of people. It is expected that the life-time rate of suicide for people with schizophrenia is about 14-20% (Jablensky 2000). From the limited data we have, there is no suggestion that family intervention makes any difference to this outcome.

1.7 Social functioning

Measuring social impairment is difficult, but from the different ratings there is an impression that family intervention does improve general functioning in this domain. Interpreting the various scale-derived outcomes is problematic. Continuous data from the Social Functioning Scale is in favour of the family intervention group, but doubts remain for its robustness given the small numbers of participants. The outcome of employment is more readily understandable and family intervention did not seem to have much of an effect, if any. Other clear outcomes relating to social functioning, living independently and imprisonment were also equivocal. This may be an example of rating scales being sensitive to slight changes that may not have repercussions for routine life.

1.8 Family outcomes

The numerous measures used in this area by several trialists suggest that this is seen as an important area for research but that there is no consensus on what to measure. A small study (n = 63) suggests that family intervention may help increase the families’ understanding of the patients’ needs. Measures of insufficient care or maltreatment by the family did not suggest family intervention lowers levels of maltreatment, although perhaps larger powered studies would have shown a treatment effect. Similarly, coping with life events was equivocal and underpowered. Need of service usage was found to be significantly lower in the standard care group. However, data from the same study found family functioning to be significantly improved in the family intervention group. Two small studies both found family intervention lessened burden, but again this family outcome is weakened by small numbers. The levels of emotion expressed within the family may indeed be reduced by family intervention.

1.9 Quality of life

Finally, the overall quality of life of family members may be increased by the family intervention package but we are unsure of the practical meaning and applicability of the result (MD 19.18 CI 9.8 to 28.6). The measure was a scale referenced in Mandarin, for which we have no adequate description and additional change data were equivocal (Bradley 2006).

1.10 Economic analyses

Reports that include an economic analysis all favour family intervention in terms of net saving in direct or indirect costs (Falloon 1981; Tarrier 1988; Xiong 1994). This is a consistent and important finding.

2. Comparison 2. Behavioural family-based versus supportive family-based interventions (more than five sessions)

Schooler 1997 involved more than 500 families. For the simple and clear outcomes reported (hospital admission and global state) there is no clear difference between the two forms of family intervention. The enormous attrition (79% by 30 months) is a major concern as regards the design and applicability of the results of this trial.

3. Comparison 3. Group family-based interventions versus individual family-based interventions (more than five sessions)

Group-based family interventions should be more economical than an individual approach. However, no economic data were reported. For global outcomes, no clear differences are apparent, with wide confidence intervals precluding firm conclusions. The same applies for outcomes related to compliance. The small trial Leff 1989 found that more people allocated to individual family intervention were able to live independently compared with those who had been randomised to the group-based family intervention (n = 23, RR 2.18 CI 1.1 to 4.4). This important outcome should be replicated.

4. Sensitivity analyses

Studies from the People’s Republic of China now make up the majority of the included studies, and evidence has emerged that many trials from China are not randomised even when stated to be (Wu 2006). We did not find any clear evidence that these studies were not truly randomised, although the absence of demographic data made judgements difficult. Nevertheless, the potential remains that these trials could contain biases. Where relevant for key outcomes, we added and subtracted these studies. Inclusion certainly tightened confidence intervals but never materially affected the direction of result or the conclusion drawn.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Participants in studies that contributed to the results were not only from several types of care-cultures, but also involved both men and women, with a wide range of ages, people with long histories of illness and those in their first episode. There were no clear dissimilarities between the trials from Australia, Europe, the People’s Republic of China and the USA. Even Buchkremer 1995, which did add heterogeneity to certain results (see below), had similar methods, inclusion criteria, interventions and outcomes to the other studies. The provision of health care for mentally ill people in the countries in which the trials were undertaken is diverse, but the relative consistency of results suggests that their outcomes may be generalised to other health service traditions.

Quality of the evidence