Summary

Pseudomyxoma peritonei (PMP) is a rare and intractable disease with an estimated incidence of one per million population per year. Many aspects of PMP need to be fully and precisely understood; these include its preoperative assessment, i.e. diagnosis, early diagnosis, pathologic classification, and staging according to the peritoneal cancer index, and its surgical treatment. This review focuses on elements of preoperative assessment and surgery using the Sugarbaker procedure to help improve the prognosis for patients with PMP. Accurate data on the incidence of PMP must be based on large populations rather than estimates, and much work needs to be done especially in China. Special attention should be paid to its preoperative assessment. Also proposed here are steps to manage PMP with an emphasis on preoperative assessment.

Keywords: Pseudomyxoma peritonei, preoperative assessment, prognosis

1. Introduction

Pseudomyxoma peritonei (PMP) is a rare and intractable disease. In 1884, Werth coined the term “pseudomyxoma peritonei” (1), which is characterized by excessive mucinous ascites and mucinous peritoneal implants, leading to progressive obliteration of the peritoneal cavity and intestinal obstruction (2,3). The accumulation of mucinous ascites and mucinsecreting epithelial nodules within the peritoneal cavity commonly results from the intraabdominal spread of invasive or non-invasive appendiceal tumors, and occasionally mucinous tumors at other sites, such as the colon (4,5) and ovaries (6–8) are responsible (9). PMP has frequently been classified as benign because it is almost noninvasive since it causes few lymphatic metastases and no hematogenic dissemination. However, the behavior of PMP over time suggests that it should be considered a borderline malignant condition with inevitable disease progression and a final terminal outcome. Recently, PMP has been referred to as a syndrome because of its different pathological types (10,11).

The clinical course of PMP is dictated by the volume of extracellular mucin that has accumulated and the degree of epithelial cellular atypia. Although PMP is less malignant and has a long clinical course, a radical resection is difficult and its prognosis is poor.

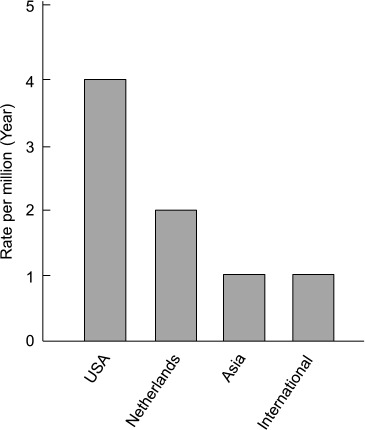

Because of its rarity, the incidence of PMP has yet to be fully determined. At present, there are no precise international data on PMP incidence, though an estimate is approximately 2 per 10,000 laparotomies or one per million population per year, with women mostly affected (2 to 3 times more frequently than men) (12–17). According to national data based on population, the annual incidence of PMP is 1,500 cases in the United States of America (USA) (18) and approximately 27 cases or 1.7 to 2 per million per year in the Netherlands (12,15). The incidence in Asia is about one per million per year and is presumed to be about a quarter of that in USA (19) (the estimated incidence of PMP is shown in Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The treatment of PMP has yet to be firmly established. Surgery is predominantly performed using the Sugarbaker procedure, but this procedure is controversial and not accepted globally. Clinicians lack a sufficient understanding of PMP and its surgical treatment in China. This review seeks to investigate surgery to treat PMP with a particular focus on its preoperative assessment.

2. Preoperative assessment: Diagnosis including pathologic classification and staging of PMP

Diagnosis, especially early diagnosis, is important to the success of surgery and prognosis for patients with PMP. Although rare, PMP covers a vast spectrum and has caused confusion over its identification and many errors in its diagnosis. The clinical manifestations of PMP are poorly defined due to few reports of large samples. Most patients are diagnosed during or after a laparotomy or laparoscopy for suspected appendicitis, peritonitis, or gynecological cancer. Wang et al. reported that patients in China are often misdiagnosed as having a malignant ovarian tumor, tuberculous peritonitis, or ascites resulting from liver cirrhosis; the misdiagnosis rate ranges from 18.8–100% according to the literature (20–25).

2.1. Diagnosis with imaging assessment

Imaging assessment is crucial to initial diagnosis. A CT scan is considered to be optimal for diagnosing PMP. (26). However, the diagnostic procedure often used first is ultrasonography. Typical ultrasound findings are non-mobile, echogenic ascites with multiple semisolid masses and scalloping of the hepatic and splenic margins (27). The results of a CT scan are sometimes pathognomonic findings that are considered to be highly suggestive of PMP (28). The most common findings on a CT scan are a large volume of mucinous ascites with the density of fat that displace the small bowel and the normal mesenteric fat. Other characteristic findings are omental thickening, multiseptate lesions, scalloping of organs, and curvilinear calcifications (27–30).

2.2. Pathologic diagnosis and pathologic classification

The pathologic classification of PMP is also key to surgical assessment and prognosis. There is considerable variability in the pathologic criteria and terminology used by different pathologists. For lesions with the same morphology, the diagnosis may be “a ruptured mucinous adenoma of the appendix and PMP” or “a ruptured mucinous adenoma of the appendix and PMP” according to different pathologists, especially in China. Most pathologists lack sufficient understanding of the pathologic classification of PMP (21,31,32). Ronnett et al. (33) proposed that the pathology of PMP be separated into 3 categories: i) low-grade tumors as disseminated peritoneal adenomucinosis (DPAM), ii) high-grade tumors as peritoneal mucinous carcinomatosis (PMCA), and iii) peritoneal mucinous carcinomatosis with intermediate or discordant features (PMCA-I/D). They reported that patients in these categories had survival rates that differed significantly, and results of long-term follow-up indicated significant differences in prognosis for DPAM and PMCA (34). Given these findings, therapeutic approaches can be rationally considered based on homogeneous pathologic entities. Findings also suggested that tumor tissue should be subjected to CK20 and CK7 immunohistochemistry. CK20 is a cytokeratin and intestinal tumor marker while CK7 is also a cytokeratin and marker of gynecological malignancies (35). The pathologic classification of PMP described thus far is gaining global acceptance (36).

2.3. Staging of PMP according to the peritoneal cancer index score

Another preoperative assessment that relates to treatment and prognosis is the staging of PMP. The peritoneal cancer index (PCI) scoring system is recommended for the staging of PMP. PCI has been used to assess the extent of the peritoneal spread of intraabdominal and intrapelvic malignant tumors. PCI provides valuable information about the exact distribution of seeding and tumor volume, representing in detail the extent of the peritoneal spread (37–39). PCI can help to determine treatment regimens and prognosis. PCI scoring is as follows (37): first, one of the thirteen abdominal regions should be scored. If there are no tumor nodules, the score is 0; if the largest tumor nodule is up to 0.5 cm in size, the score is 1; if the largest tumor nodule is up to 5 cm, the score is 2; and if the largest tumor nodule is larger than 5 cm or tumors converge, the score is 3. Second, the scores for all thirteen regions are added together to yield the PCI score. Lower PCI scores are generally associated with a better prognosis and a greater likelihood of successful cytoreduction surgery. In some cases, a patient may have undergone surgery without intraperitoneal chemotherapy prior to cytoreduction surgery and intraperitoneal chemotherapy. The prior surgical score (PSS) gives a number value to surgeries done prior to the attempt at debulking/peritoneal chemotherapy treatment. However, Tentes et al. found that PSS was not related to survival for patients with PMP (37).

2.4. Serum tumor makers

In addition to clinical manifestations, imaging assessment, pathologic classification, and staging, several serum tumor markers, such as carcino-embryonic antigen (CEA), cancer antigen 125 (CA125), and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9), are also recommended to help diagnose PMP. The prognostic value of these tumor markers in patients undergoing surgery has been evaluated. Baratti reported that, according to univariate analysis, normal preoperative CA125 correlated with the likelihood of successful surgery and that, according to multivariate analysis, elevated baseline CA19-9 was an independent predictor of shorter progression-free survival (40). Van Ruth et al. (41) reported that elevated CA19-9 after surgery or during follow-up was related to disease recurrence.

3. Surgery to treat PMP

Since PMP is rare and intractable, patients with PMP have a poor long-term survival without definitive treatment, with 5-year and 10-year survival rates of 50% and 10–30%, respectively (42). Currently, there is no globally accepted standard treatment for PMP.

3.1. Sugarbaker procedure

The most satisfactory and effective treatment for PMP is surgical cytoreduction. Conventional surgical cytoreduction involved several surgeries until there were no further surgical options. Surgical debulking and appendectomy are widely regarded as the primary treatments for PMP. Sugarbaker developed and encouraged a complex approach involving cytoreduction and intraoperative hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy since the 1980s. A 5-year survival rate of 86% has been reported for some patients (43). Currently, the optimal therapy is complete macroscopic tumor removal (complete cytoreduction) combined with heated intraoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Known as the Sugarbaker procedure, this treatment is considered to be the standard of care for PMP due to a perforated tumor in the appendix particularly in USA and Europe. In cases where complete cytoreduction cannot be achieved, maximal tumor debulking can be utilized (44–49).

While the Sugarbaker procedure has been adopted globally and is considered the optimal treatment for PMP, an optimal or standard treatment for PMP has yet to be established in China. There are few reported cases of Chinese patients undergoing complete cytoreduction combined with heated intraoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy, and some clinicians complained of the lack of a unified standard for radical surgery (3,5,50). Kojimahara and Kitai et al. reported that radical cytoreduction and heated intraoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy are not widely used in Japan. Given the risks of treatment, the procedure should ideally be performed at a referral center or at least by an experienced surgeon. An optimal or standard treatment for PMP has yet to be established in Japan (51,52).

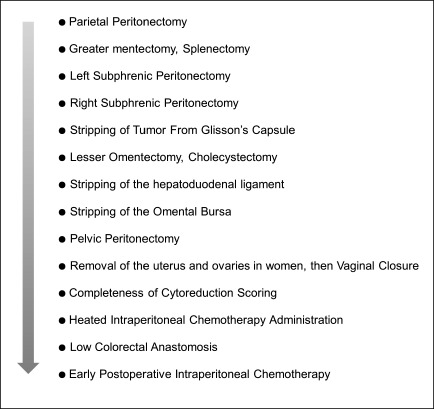

3.2. Sugarbaker procedure and its association with the CC score, morbidity, and mortality

Details on the Sugarbaker procedure (53–55) are shown in Figure 2. Intraoperative hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy is used in combination with cytoreduction surgery to kill microscopic cells released into the peritoneal cavity from tumors during surgery or to kill cells released into the abdomen in cases of appendiceal rupture. Immediate assessment at the end of the surgery using the Completeness of Cytoreduction (CC) score (Table 1) is recommended. This scoring is crucial to assess prognosis. Given the complexity of the procedure, its morbidity and mortality are considerable. Major morbidity is considered to include anastomotic leakage, enteric and pancreatic fistulation, pneumonia, thromboembolism, and intra-abdominal abscesses (21). Mortality rates range between 0% and 14% (56). However, Youssef et al. (57) recently reported that the Sugarbaker procedure can be performed with a mortality rate below 2% and excellent long-term outcomes can be achieved in specialized units.

Figure 2.

Chart of steps for the Sugarbaker procedure.

Table 1. Completeness of Cytoreduction (CC) Score (Ref. 53).

| Score | Completeness of Cytoreduction |

|---|---|

| CC-0 | All tumors are removed during cytoreduction surgery, and there is no visible cancer in the abdomen at the completion of the surgery. |

| CC-1 | Tumor nodules remain in the abdomen or pelvis after surgery but are less than 2.5 mm in size. |

| CC-2 | Tumor nodules remain in the abdomen or pelvis and are between 2.5 mm and 2.5 cm in size. |

| CC-3 | Tumor nodules greater than 2.5 cm or a confluence (merging) of non-removable tumor nodules remain at any site in the abdomen or pelvis after surgery. |

4. Patient eligibility for the Sugarbaker procedure

The Sugarbaker procedure has a relatively high morbility and mortality, so many clinicians wonder about the patient benefits of the Sugarbaker procedure. The benefits of this procedure must be evaluated in terms of the risks involved. According to a report (58) by Akshat Saxena et al., patients who were < 80 years old, with good performance status (World Health Performance Status B2), and adequate hematological, hepatic, cardiac, and liver function were eligible. Patients with extra-abdominal metastasis were ineligible. They also found that patients with an American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grade of 3 or higher were significantly more likely to have severe complications and that perioperative mortality was significantly associated with a peritoneal cancer index (PCI) > 24. In detail, the ASA grade is as follows: a normal healthy patient is regarded as ASA grade 1, a patient with mild or severe systemic disease is regarded as ASA grade 2 or 3, a patient with an incapacitating systemic disease that is a constant threat to life is regarded as ASA grade 4, and a moribund patient who is not expected to survive for 24 hours without the operation is regarded as ASA grade 5 (59). Sugarbaker (53) reported that asymptomatic patients with a small volume of peritoneal surface malignancies must be selected for combined treatment.

5. Discussion and prospects for the future

PMP is a rare syndrome but affects a larger number of patients. However, the international incidence of PMP remains unclear. The data are estimates, and few studies have examined the incidence of PMP in large populations, especially in China. The PubMed database and Chinese CNKI database revealed few studies at multiple centers or with large samples of Chinese patients. Therefore, a specific and specialized website should be created to collect information on and determine the incidence of PMP, and this website can help to educate doctors in China. A peritoneal malignancy treatment center should also be established in China to help treat PMP and rare and intractable conditions like it (57,60).

PMP is not only rare but also intractable, which is the cause of its poor prognosis. The treatment of PMP is controversial and lacking in hard scientific evidence. Such evidence is unlikely ever to be available due to the rare heterogeneity of the disease (61). Although controversial, the Sugarbaker procedure is gaining internationally acceptance as the standard treatment for PMP. Mortality associated with the Sugarbaker procedure can reportedly be reduced to less than 2% and excellent long-term outcomes can be achieved in specialized units (57), representing substantial progress in the treatment of PMP. The outcomes of initial surgery are significantly related to prognosis, so the preoperative assessment of PMP in relation to surgical outcomes should be comprehensively and carefully considered.

First, PMP should be diagnosed early. Since PMP involves unspecified clinical manifestations and ultrasonography is frequently performed as the initial diagnostic procedure, sonographers should be informed about PMP. Screening for serum tumor markers such as CEA, CA125, and CA19-9 is also suggested for early diagnosis. Surgeons and general physicians who diagnosis patients with “a malignant mucocele or malignant mucocele with peritoneal dissemination” must promptly refer those patients to a specialist (57). If these patients are promptly referred, surgery is less extensive, morbidity and mortality rates will be lower and hospital stays will be shorter, and long-term results will improve.

Second, preoperative pathologic classification of PMP must be precise and definite. However, the definition of PMP has been a source of much confusion, with different reports including patients with ovarian, colon and other primary tumors, in addition to appendiceal tumors (62–64). Thus, the pathologic description and classification of PMP is unclear. Most Chinese pathologists lack a sufficient understanding of the pathologic classification of PMP, so PMP must be described according to a unified pathologic descriptive terminology. The currently accepted pathologic classification is the 3-category classification, i.e. DPAM/PMCA/PMCA-I/D, proposed by Ronnett et al. (33). This pathologic classification of PMP is significantly related to the treatment and prognosis of PMP, so it should be utilized in the pathologic classification of PMP. CK20 and CK7 immunohistochemistry should also be utilized. The question then is how to reach a preoperative pathologic diagnosis. A CT or ultrasound-guided biopsy or a laparoscopic examination and biopsy should be performed on patients suspected of having PMP.

The third point is the staging of PMP in accordance with the preoperative peritoneal cancer index (PCI). PCI is a clinical integration of both peritoneal implant size and distribution of nodules on the peritoneal surface. It is crucial to prognosis and also helpful in determining which patients with PMP are eligible for surgery. It should be used in the decision-making process as the abdomen is completely explored, but can the PCI be determined noninvasively before surgery? Is a CT PCI possible? Studies have unanimously concluded that CT sensitivity increases markedly with larger implants (26,65). The results of a study by Jacquet et al. are comparable to other studies: 28% for nodules < 0.5 cm in diameter compared to 90% for ones > 5 cm (65). Additionally, de Bree et al. found that CT rather inaccurately represented the actual size of peritoneal nodules (66). A CT scan's ability to detect peritoneal implants is influenced by lesion size and CT PCI significantly underestimates the clinical PCI. The mean operative PCI is nearly double that approximated by CT. A reasonable approach may be for patients with a preoperative CT PCI > 15 to be considered ineligible for combined treatment because their clinical PCI may be much higher (67). Thus, the preoperative PCI should be determined by laparotomy just before the Sugarbaker procedure or laparoscopy.

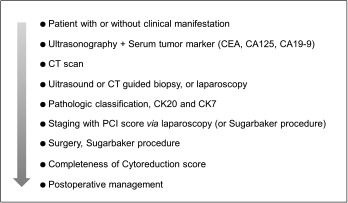

In conclusion, PMP is a rare and intractable entity. Special attention should be paid to its preoperative assessment, including early diagnosis, pathologic classification, and peritoneal cancer index. Proposed here are steps for managing PMP that include preoperative assessment (Figure 3). Currently, PMP is treated with complete cytoreduction combined with heated intraoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy (Sugarbaker procedure) as a widely accepted and even standard curative treatment in Europe and the US. In Asia, however, this treatment is not as widely accepted as conventional surgery. If patients are appropriately selected, the Sugarbaker procedure can provide excellent long-term outcomes. In the absence of animal models or randomized controlled trials, further efforts should be made to obtain evidence and improve treatment outcomes for this challenging, though rare condition.

Figure 3.

Proposed chart of steps in the management of PMP.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Fund for Young Scholars of China (81000177, Yuesi Zhong) and supported in part by the Japan-China Medical Association.

References

- 1. Werth R. Klinische and Anastomische Untersuchungen Zur Lehre von der Bauchgeswullsten und der laparotomy. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 1884; 84:100-118 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Moran BJ, Cecil TD. The etiology, clinical presentation, and management of pseudomyxoma peritonei. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2003; 12:585-603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chua TC, Yan TD, Smigielski ME, Zhu KJ, Ng KM, Zhao J, Morris DL. Long-term survival in patients with pseudomyxoma peritonei treated with cytoreductive surgery and perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy: 10 years of experience from a single institution. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009; 16:1903-1911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bruin SC, Verwaal VJ, Vincent A, van't Veer LJ, van Velthuysen ML. A clinicopathologic analysis of peritoneal metastases of colorectal and appendiceal origin. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010; 17:2330-2340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Evers DJ, Verwaal VJ. Indication for oophorectomy during cytoreduction for intraperitoneal metastatic spread of colorectal or appendiceal origin. Br J Surg. 2011; 98:287-292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shen DH, Ng TY, Khoo US, Xue WC, Cheung AN. Pseudomyxoma peritonei - A heterogenous disease. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1998; 62:173-182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lee KR, Scully RE. Mucinous tumors of the ovary: A clinicopathologic study of 196 borderline tumors (of intestinal type) and carcinomas, including an evaluation of 11 cases with ‘seudomyxoma peritonei’. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000; 24:1447-1464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lee JK, Song SH, Kim I, Lee KH, Kim BG, Kim JW, Kim YT, Park SY, Cha MS, Kang SB. Retrospective multicenter study of a clinicopathologic analysis of pseudomyxoma peritonei associated with ovarian tumors (KGOG 3005). Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2008; 18:916-920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Takeuchi M, Matsuzaki K, Yoshida S, Nishitani H, Uehara H. Localized pseudomyxoma peritonei in the female pelvis simulating ovarian carcinomatous peritonitis. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2003; 27:622-625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Smeenk RM, Verwaal VJ, Zoetmulder FA. Toxicity and mortality of cytoreduction and intraoperative hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in pseudomyxoma peritonei - A report of 103 procedures. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2006; 32:186-190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hinson FL, Ambrose NS. Pseudomyxoma Peritonei. Br J Surg. 1998; 85:1332-1339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Smeenk RM, van Velthuysen ML, Verwaal VJ, Zoetmulder FA. Appendiceal neoplasms and pseudomyxoma peritonei: A population based study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2008; 34:196-201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mann WJ, Jr, Wagner J, Chumas J, Chalas E. The management of pseudomyxoma peritonei. Cancer. 1990; 66:1636-1640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moran BJ. Establishment of a peritoneal malignancy treatment centre in the United Kingdom. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2006; 32:614-618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mukherjee A, Parvaiz A, Cecil TD, Moran BJ. Pseudomyxoma peritonei usually originates from the appendix: A review of the evidence. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2004; 25:411-414 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Smith JW, Kemeny N, Caldwell C, Banner P, Sigurdson E, Huvos A. Pseudomyxoma peritonei of appendiceal origin. The Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center experience. Cancer. 1992; 70:396-401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sherer DM, Abulafia O, Eliakim R. Pseudomyxoma peritonei: A review of current literature. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2001; 51:73-80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Choudry HA, O'Malley ME, Guo ZS, Zeh HJ, Bartlett DL. Mucin as a Therapeutic Target in Pseudomyxoma Peritonei. J Surg Oncol. 2012; 14:1-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Katayama K, Yamaguchi A, Murakami M, Koneri K, Nagano H, Honda K, Hirono Y, Goi T, Iida A, Ito H. Chemo-hyperthermic peritoneal perfusion (CHPP) for appendiceal pseudomyxoma peritonei. Int J Clin Oncol. 2009; 14:120-124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wang YR, Zhang QZ, Yang Q, Wang XR. Diagnosis and Misdiagnosis of Pseudomyxoma Peritonei in Chinese Patients (Review of the Literature 2000–2008). Clinical Misdiagnosis & Mistherapy. 2009; 22:1-4 (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 21. Guo AT, Li YM, Wei LX. Pseudomyxoma peritonei of 92 Chinese patients: Clinical characteristics, pathological classification and prognostic factors. World J Gastroenterol. 2012; 18:3081-3088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Xu T, Sun G, Lu XH. The analysis of misdiagnosis of pseudomyxoma peritonei. Clinical Misdiagnosis & Mistherapy. 2001; 14:35-36 (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shi SH, Zhang ZR, Li S, Ding ZM. Experience of diagnosis and treatment in 7 cases of pseudomyxoma peritonei. J of Wannan Medical University. 2008; 27:212-214 (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 24. Li JY, Li T, Deng Q, Zhang XQ. Diagnosis of 9 patients with pseudomyxoma peritonei via laparoscopic biopsy. Chinese Journal of Digestive Endoscopy. 2005; 22:205-206 (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lv YG, Cao DY, Tao KS, Wang L. Diagnosis and treatment experience of 12 cases of PMP. Modern Oncology. 2006; 14:1133-1135 (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jacquet P, Jelinek JS, Chang D, Koslowe P, Sugarbaker PH. Abdominal computed tomographic scan in the selection of patients with mucinous peritoneal carcinomatosis for cytoreductive surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 1995; 181:530-538 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Seshul MB, Coulam CM. Pseudomyxoma peritonei: Computed tomography and sonography. Am J Roentgenol. 1981; 136:803-806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Matsumi H, Kozuma S, Osuga Y, Yano T, Yoshikawa H, Tsutsumi O, Taketani Y. Ultrasound imaging of pseudomyxoma peritonei with numerous vesicles in ascitic fluid. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1999; 13:378-379 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Low RN, Barone RM, Lacey C, Sigeti JS, Alzate GD, Sebrechts CP. Peritoneal tumor: MR imaging with dilute oral barium and intravenous gadolinium-containing contrast agents compared with unenhanced MR imaging and CT. Radiology. 1997; 204:513-520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sait KH. Pseudomyxoma peritonei: Diagnosis and management. JKAU-Medical Sciences. 2006; 13:21-32 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhang RY. Clinicopathological analysis of pseudomyxoma peritonaei. Chin J Clin Oncol Rehabil. 2005; 12:197-199 (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dong Y, Li T, Zhou WZ, Liang Y, Lu W. Pseudomyxoma peritonei: Report of 11 cases with a literature review. Chin J Pathol. 2002; 31:522-525 (in Chinese) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ronnett BM, Zahn CM, Kurman RJ, Kass ME, Sugarbaker PH, Shmookler BM. Disseminated peritoneal adenomucinosis and peritoneal mucinous carcinomatosis. A clinicopathologic analysis of 109 cases with emphasis on distinguishing pathologic features, site of origin, prognosis, and relationship to “pseudomyxoma peritonei”. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995; 19:1390-1408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ronnett BM, Yan H, Kurman RJ, Shmookler BM, Wu L, Sugarbaker PH. Patients with pseudomyxoma peritonei associated with disseminated peritoneal adenomucinosis have a significantly more favorable prognosis than patients with peritoneal mucinous carcinomatosis. Cancer. 2001; 92:85-91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ronnett BM, Shmookler BM, Diener-West M, Sugarbaker PH, Kurman RJ. Immunohistochemical evidence supporting the appendiceal origin of pseudomyxoma peritonei in women. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1997; 16:1-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bevan KE, Mohamed F, Moran BJ. Pseudomyxoma peritonei. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2010; 2:44-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tentes AA, Tripsiannis G, Markakidis SK, Karanikiotis CN, Tzegas G, Georgiadis G, Avgidou K. Peritoneal cancer index: A prognostic indicator of survival in advanced ovarian cancer. Eur J Surg Onco. 2003; 29:69-73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sugarbaker PH, Jablonski K. Prognostic features of 51 colorectal and 130 appendiceal cancers with peritoneal carcinomatosis treated by cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Ann Surg. 1995; 221:124-132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jacqeut P, Sugarbaker P. Clinical research methodologies in diagnosis and staging of patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis. In: Sugarbaker PH. (ed.), Peritoneal Carcinomatosis: Principles of Management. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers. 1996; pp. 359-374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Baratti D, Kusamura S, Martinetti A, Seregni E, Laterza B, Oliva DG, Deraco M. Prognostic value of circulating tumor markers in patients with pseudomyxoma peritonei treated with cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007; 14:2300-2308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Van Ruth S, Hart AA, Bonfrer JM, Verwaal VJ, Zoetmulder FA. Prognostic value of baseline and serial carcinoembryonic antigen and carbohydrate antigen 19.9 measurements in patients with pseudomyxoma peritonei treated with cytoreduction and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002; 9:961-967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sugarbaker PH, Chang D. Results of treatment of 385 patients with peritoneal surface spread of appendiceal malignancy. Ann Surg Oncol. 1999; 6:727-731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sugarbaker PH. Cytoreductive surgery and peri-operative intraperitoneal chemotherapy as a curative approach to pseudomyxoma peritonei syndrome. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2001; 27:239-243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Witkamp AJ, de Bree E, Kaag MM, Boot H, Beijnen JH, van Slooten GW, van Coevorden F, Zoetmulder FA. Extensive cytoreductive surgery followed by intraoperative hyperthermic intraperito-neal chemotherapy with mitomycin-C in patients with perito-neal carcinomatosis of colorectal origin. Eur J Cancer. 2001; 37:979-984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Deraco M, Baratti D, Inglese MG, Allaria B, Andreola S, Gavazzi C, Kusamura S. Peritonectomy and intraperitoneal hyperthermic perfusion (IPHP): A strategy that has confirmed its efficacy in patients with pseudomyxoma perito-nei. Ann Surg Oncol. 2004; 11:393-398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Loungnarath R, Causeret S, Bossard N, Faheez M, Sayag-Beaujard AC, Brigand C, Gilly F, Glehen O. Cytoreductive surgery with intraperitoneal chemohyperthermia for the treatment of pseudomyxoma peritonei: A prospective study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005; 48:1372-1379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Yan TD, Links M, Xu ZY, Kam PC, Glenn D, Morris DL. Cytoreductive surgery and perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy for pseudomyxoma peritonei from appendiceal mucinous neoplasms. Br J Surg. 2006; 93:1270-1276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Stewart JH, 4th, Shen P, Russell GB, Bradley RF, Hundley JC, Loggie BL, Geisinger KR, Levine EA. Appendiceal neoplasms with peritoneal dissemination: Outcomes after cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006; 3:624-634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gough DB, Donohue JH, Schutt AJ, Gonchoroff N, Goellner JR, Wilson TO, Naessens JM, O'Brien PC, van Heerden JA. Pseudomyxoma peritonei: Long-termpatient survival with an aggressive regional approach. Ann Surg. 1994; 219:112-119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Liu MC. Surgical treatment experience of 2 cases with pseudomyxoma peritonei. Modern Medicine & Health. 2007; 23:1362 (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kojimahara T, Nakahara K, Shoji T, Sugiyama T, Takano T, Yaegashi N, Yokoyama Y, Mizunuma H, Tase R, Satou H, Tanaka T, Motoyama T, Kurachi H. Identifing prognostic factors in Japanese women with pseudomyxoma peritonei: A retrospective clinic-pathological study of the tohoku gynecologic cancer unit. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2011; 223:91-96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kitai T, Kawashima M, Yamanaka K, Ichijima K, Fujii H, Mashima S, Shimahara Y. Cytoreductive surgery with intraperitoneal chemotherapy to treat pseudomyxoma peritonei at nonspecialized hospitals. Surg Today. 2011; 41:1219-1223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sugarbaker PH, Surgical responsibilities in the management of peritoneal carcinomatosis. J Surg Oncol. 2010; 101:713-724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sugarbaker PH. Parietal peritonectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012; 19:1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Mirnezami AH, Moran BJ, Cecil TD. Sugarbaker procedure for pseudomyxoma peritonei. Tech Coloproctol. 2009; 13:373-374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Smeenk RM, Bruin SC, van Velthuysen ML, Verwaal VJ. Pseudomyxoma peritonei. Curr Probl Surg. 2008; 45:527-575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Youssef H, Newman C, Chandrakumaran K, Mohamed F, Cecil TD, Moran BJ. Operative findings, early complications, and long-term survival in 456 patients with pseudomyxoma peritonei syndrome of appendiceal origin. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011; 54:293-299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Saxena A, Yan TD, Chua TC, Morris DL. Critical assessment of risk factors for complications after cytoreductive surgery and perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy for pseudomyxoma peritonei. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010; 17:1291-1301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Owens WD, Felts JA, Spitznagel EL, Jr. ASA physical status classification: A study of consistency of ratings. Anesthesiology. 1978; 49:239-243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Sugarbaker PH. Twenty-three years of progress in the management of a rare disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011; 54:265-266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Bender MD, Ockner RK. Diseases of the peritoneum, mesentery and diaphragm. In: Sleisenger MH, Fordtran JS. (eds). Gastrointestinal disease. Philadelphia: WB Saunders. 1983; pp. 1569-1596 [Google Scholar]

- 62. Sulkin TV, O'Neill H, Amin AI, Moran B. CT in pseudomyxoma peritonei: A review of 17 cases. Clin Radiol. 2002; 57:608-613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Sugarbaker PH, Ronnett BM, Archer A, et al. Pseudomyxoma peritonei syndrome. Adv Surg. 1996; 30:233-280 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Hinson FL, Ambrose NS. Pseudomyxoma peritonei. Br J Surg. 1998; 85:1332-1339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Jacquet P, Jelinek JS, Steves MA, Sugarbaker PH. Evaluation of computed tomography in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis. Cancer. 1993; 72:1631-1636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. de Bree E, Koops W, Kröger R, van Ruth S, Witkamp AJ, Zoetmulder FA. Peritoneal carcinomatosis from colorectal or appendiceal origin: Correlation of preoperative CT with intraoperative findings and evaluation of interobserver agreement. J Surg Oncol. 2004; 86:64-73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Koh JL, Yan TD, Glenn D, Morris DL. Evaluation of preoperative computed tomography in estimating peritoneal cancer index in colorectal peritoneal carcinomatosis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009; 16:327-333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]