Abstract

Cigarette smoking has long been a target of public health intervention because it substantially contributes to morbidity and mortality. Individuals in different-sex marriages have lower smoking risk (i.e., prevalence and frequency) than different-sex cohabiters. However, little is known about the smoking risk of individuals in same-sex cohabiting unions. We compare the smoking risk of individuals in different-sex marriages, same-sex cohabiting unions, and different-sex cohabiting unions using pooled cross-sectional data from the 1997–2010 National Health Interview Surveys (N = 168,514). We further examine the role of socioeconomic status (SES) and psychological distress in the relationship between union status and smoking. Estimates from multinomial logistic regression models reveal that same-sex and different-sex cohabiters experience similar smoking risk when compared to one another, and higher smoking risk when compared to the different-sex married. Results suggest that SES and psychological distress factors cannot fully explain smoking differences between the different-sex married and same-sex and different-sex cohabiting groups. Moreover, without same-sex cohabiter’s education advantage, same-sex cohabiters would experience even greater smoking risk relative to the different-sex married. Policy recommendations to reduce smoking disparities among same-sex and different-sex cohabiters are discussed.

Keywords: Same-sex cohabitation, Smoking, National Health Interview Survey, Socioeconomic status, Psychological distress

Cigarette smoking is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the U.S. (Center for Disease Control and Prevention 2008; Hummer et al. 1998; World Health Organization 2008). Despite dramatic smoking rate reductions in most U.S. subpopulations over the last several decades, substantial disparities in smoking persist (Center for Disease Control and Prevention 2013; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2000a). A significant body of research shows that the different-sex married have diminished smoking risk, including lower smoking prevalence (i.e., are less likely be current smokers) and frequency (i.e., smoke fewer cigarettes when current smokers) than different-sex cohabiters (Bachman et al. 1997, 2001; Waite and Gallagher 2000). Research suggests this reduced smoking risk is at least partially the result of different-sex married individuals’ higher levels of socioeconomic status (SES) and lower levels of psychological distress relative to different-sex cohabiters (Carr and Springer 2010; Waite and Gallagher 2000)—factors strongly related to smoking risk (Galea et al. 2004; Pampel 2005, 2006; Pampel et al. 2010)

While the importance of union status for smoking has been consistently demonstrated in research on different-sex groups, it is unclear how the smoking patterns of different-sex married and cohabiting individuals compare to those of same-sex cohabiting individuals (Buffie 2011; Gruskin et al. 2007; Institute of Medicine of the National Academies (IOM) (2011); King and Bartlett 2006; Lee et al. 2009; Ryan et al. 2001). Does the marital advantage extend to same-sex cohabiting individuals, or are same-sex cohabiters more similar to different-sex cohabiters and thus disadvantaged relative to the different-sex married? In order to address this research gap, the present study compares the smoking risk, measured by smoking prevalence (i.e., risk of being a current, former, or never smoker) and smoking frequency (i.e., risk of being a current everyday or somedays smoker1) across different-sex married, same-sex cohabiting, and different-sex cohabiting persons in a large nationally representative sample drawn from the 1997–2010 U.S. National Health Interview Surveys (NHIS). We further examine the role of two factors previously identified as underlying the associations between union status and smoking: socioeconomic resources (e.g., education, income, employment status, and health insurance) and psychological distress.

Union Status and Smoking

No national population-based studies known to the authors examine the relationship between same-sex union status and smoking. Previous research demonstrates that the different-sex married have lower smoking prevalence and frequency than the different-sex cohabiting (Bachman et al. 1997, 2001; Umberson 1992; Waite 1995). Theoretically, this is because the married are advantaged on factors associated with reduced smoking risk—most predominately lower levels of psychological distress and higher SES—due to the selection of advantaged individuals into marriage and the accrual of resources within marriage (Carr and Springer 2010; Goldman 1993; Waite and Gallagher 2000). Building off this body of work, we develop hypotheses theorizing how the smoking risk of the different-sex married, same-sex cohabiting, and different-sex cohabiting differ; we further hypothesize how SES and psychological distress underlie these differences.

Socioeconomic Status

Marriage is associated with advantaged SES (e.g., education, income, employment status, health insurance); SES is a fundamental cause of smoking risk (Link and Phelan 1995). Marital selection processes play a central role in the SES and union status association. According to a selection approach, individuals with higher SES are selected into different-sex marriage because they are advantaged on the marriage market (Brown 2000; Fu and Goldman 1996; Goldman 1993; Sweeney 2002). Education is among the strongest SES selection factors (Ross and Mirowsky 2013), and educational status is in turn strongly related to smoking prevalence and frequency (Maralani 2013). Relative to their less educated counterparts, people with higher levels of education have more knowledge of smoking risk (Layte and Whelan 2009; Link 2008), have more non-smoking social contacts reducing the social desirability of smoking (Christakis and Fowler 2008; Pampel 2005, 2006), and are more likely to be employed in environments where smoking is restricted, providing disincentive for smoking initiation and incentive for smoking cessation (Cutler and Lleras-Muney 2010; de Walque 2007, 2010; Fagan et al. 2007b; Gilman et al. 2008; Pampel et al. 2010; Wetter et al. 2005). Recent evidence suggests that same-sex cohabiting individuals have similar or even higher levels of education when compared to the different-sex married and different-sex cohabiting (Andersson et al. 2006; Black et al. 2000, 2003; Gates 2013), possibly due to analogous selection effects into same-sex cohabitation and different-sex marriage. Advantaged education levels may contribute to similar or even lower smoking risk for the same-sex cohabiting relative to the different-sex married and cohabiting.

Although the selection of highly educated individuals into same-sex cohabiting unions may contribute to a reduced smoking risk for this group, other SES factors are likely associated with an increased smoking risk for same-sex cohabiters relative to those in different-sex marriages (Carr and Springer 2010; Umberson et al. 2010; Wu et al. 2003). Relative to the different-sex married, same- and different-sex cohabiters appear to be disadvantaged on full-time employment status and income (Ahituv and Lerman 2007; Ash and Badgett 2006; Badgett 2001; Phua and Kaufman 1999; Raley 1996; Thomson and Colella 1992; although see Gates 2013), experience higher rates of poverty, and are more likely to use food stamps (Badgett et al. 2013; Graefe and Lichter 1999; Lichter et al. 2003). Research suggests different-sex cohabiters are disadvantaged on these SES measures because those with advantaged income and full-time employment are selected into marriage rather than cohabitation. However, this is unlikely to be the case for same-sex cohabiters as they are legally restricted from selecting into marriage in most U.S. states. More likely, same-sex cohabiters may experience such disadvantage because they have restricted access to marital resources that enhance SES such as the legal, financial, and SES benefits accrued with state and federal marriage (IOM 2011; King and Bartlett 2006). Thus, same-sex cohabiting individuals do not accrue state- or federal-level economic benefits that enhance income such as the filing joint federal tax returns (Lau and Strohm 2011). Additionally, previous research suggests that relative to the different-sex married, individuals in same-sex cohabiting and different-sex cohabiting unions alike are less likely to pool their economic resources (Becker 1981; Waite and Gallagher 2000; Solomon et al. 2005) or specialize in paid/unpaid labor (Black et al. 2007; Brines and Joyner 1999; Chun and Lee 2001; Gupta 1999; Kurdek 2007; Solomon et al. 2005), potentially reducing the socioeconomic dividends of cohabitation. The different-sex married also have greater access to health insurance than same- and different-sex cohabiters (Buchmueller and Carpenter 2010; although see Heck et al. 2006 for contrary evidence), in part because married people are more likely than the cohabiting to have adequate incomes to purchase insurance and are more likely to be employed full-time in occupations that include employer- and spousal-based health insurance programs (Cohen and Martinez 2012; Meyer and Pavalko 1996; Zuvekas and Taliaferro 2003).

These interrelated and interdependent socioeconomic differences (i.e., employment status, income, and health insurance status) across union status groups may in turn relate to differences in smoking risk (Gilman et al. 2003; Graham et al. 2006; Huisman et al. 2005). Smoking initiation and continuance is more prevalent and cessation attempts are less successful among the un- or under-employed, those with lower incomes, and those with lower rates of health insurance in comparison to their more advantaged counterparts (Fagan et al. 2007a, b; Molarius et al. 2001; Stronks et al. 1997). This is due in part to smoking restrictions, clear air rules, non-smoking norms, and insurance initiatives at full-time higher-income workplaces that reduce the availability and acceptability of smoking (Bauer et al. 2005; Sorensen et al. 2004). Moreover, individuals with higher income, who have health insurance, and/or are employed full-time have an increased sense of self-efficacy and personal control (Mirowsky and Ross 2007) and are able to afford and access more effective nicotine cessation programs (Cokkinides et al. 2005; Fagan et al. 2007a, b; Lillard et al. 2007; Manley et al. 2003); these factors deter smoking initiation, reduce smoking dependence, and promote smoking cessation. Additionally, low income and poverty, lack of health insurance, and un/under-employment are each related to increased stress (Arnetz et al. 2010; Finkelstein et al. 2012), in part because SES advantaged individuals are more likely to participate in stress-reducing activities (e.g., counseling services, physical activity) (Baker et al. 2004; Biddle and Mutrie 2008; Wang et al. 2005). High stress is associated with increased smoking risk (Barbeau et al. 2004; Cokkinides et al. 2009; Pampel et al. 2010; Wetter et al. 2005).

Taking previous research together, we hypothesize that:

-

H1

Same-sex cohabiting (H1a) and different-sex cohabiting (H1b) individuals will have higher smoking prevalence and frequency than the different-sex married. The same-sex cohabiting will have similar smoking risk as the different-sex cohabiting (H1c).

-

H2

Employment status, income and poverty, and health insurance status will at least partially account for smoking disparities across union status groups (H2a); same-sex cohabiters’ higher educational status relative to other union status groups will be protective against smoking risk (H2b).

Psychological Distress

The different-sex married experience lower levels of psychological distress relative to the different-sex cohabiting (Kohler et al. 2005; Uecker 2012). This is likely due to the selection of individuals with lower levels of psychological distress into marriage and more distressed people into cohabitation (Blekesaune 2008), but also because different-sex marriage confers psychologically enhancing resources such as social integration (e.g., feeling connected to others) and social support (e.g., instrumental, emotional, and financial care) from both one’s spouse and from other network members (Gove et al. 1983; Ross 1995; Stutzer and Frey 2006). For example, compared to the different-sex married, different-sex cohabiters make fewer relationship-specific emotional and financial investments, experience lower levels of social support (Haskey 2001; Heimdal and Houseknecht 2004; Liu and Reczek 2012; Waite 1995), are in less stable and less committed relationships (Brown 2000; Brown et al. 2008), are more likely to report strain in their relationships (Skinner et al. 2002; Horwitz and White 1998), and have shorter relationship durations (Heaton 2002). These factors shape psychological distress (Mirowsky and Ross 2003), and psychological distress is in turn related to higher smoking prevalence and frequency (Center for Disease Control and Prevention 2013; Galea et al. 2004).

It may be that there are analogous selection and marital resource factors that are present in different-sex marriage and same-sex cohabitation associated with advantaged psychological well-being (Kurdek 2004; Reczek and Umberson 2012; Wight et al. 2013); in this case, same-sex cohabiters would experience smoking rates comparable to the different-sex married and lower than the different-sex cohabiting. However, given the context within which same-sex cohabiters live, these psychological and distress-related processes likely operate differently across same-sex and different-sex unions. For example, psychological distress may not be a selection factor into same-sex cohabitation as is found among the heterosexual population due to the inability to select into same-sex marriage (Lau and Strom 2011). Additionally, same-sex cohabiters likely experience higher rates of overall psychological distress than the different-sex married (Meyer 2003), but perhaps similar rates to that of the different-sex cohabiting, due to the combination of a stigmatized same-sex relationship (Powell et al. 2010), their non-legalized and non-socially sanctioned cohabiting status (Cherlin 2004; Meyer 2003; Wight et al. 2013), lower levels of familial and network-member social support for their union (Balsam et al. 2008; Ocobock 2013; Solomon et al. 2005), shorter relationship durations (Lau 2012), and higher levels of intimate relationship conflict (Kurdek 2001, 2004) relative to the different-sex married. Each of these factors are associated with lower levels of psychological distress and, in turn, higher smoking prevalence and frequency (Galea et al. 2004; Ross et al. 1990).

Taken together, we hypothesize that:

-

H3

Psychological distress will at least partially account for smoking disparities across union status groups.

Methods

Data

We use pooled cross-sectional data from the 1997–2010 National Health Interview Surveys (NHIS) Sample Adult Core files obtained from the Integrated Health Interview Series website (MPC 2012). The NHIS is a cross-sectional household survey conducted annually by the U.S. National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). The NHIS is representative of the U.S. civilian non-institutionalized population in a given survey year (McCabe et al. 2010). One adult in each household is randomly selected to answer supplementary questions on smoking behavior and other additional health information contained in the Sample Adult questionnaire. We pool data from 1997 to 2010 to increase the number of same-sex cohabiting individuals. We limit our analyses to respondents between the ages of 18 and 65. Respondents older than age 65 are excluded to reduce potential biases related to mortality selection (Christopoulou et al. 2011), because marriage, cohabitation, and same-sex relationships may hold different meanings for older adults (Reczek et al. 2009; Brown et al. 2008), and because smoking prevalence and frequency has different meaning and consequences for older adults (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2012).2 We listwise deleted respondents with missing information on all variables in our models (except for poverty, see below).3 The final sample used in our analyses includes 168,514 respondents; among them 1,252 respondents are identified as same-sex cohabiters. The analyses are weighted and we used the survey data analysis commands in Stata (StataCorp 2012) to account for clustering and post-stratification.

Measures

Union Status

Union status is divided into three categories: different-sex married, different-sex cohabiting, and same-sex cohabiting. We use the different-sex married as our reference group in the main analyses, but also conduct additional analyses using the same-sex cohabiting as the reference group in order to compare the same-sex cohabiting with the different-sex cohabiting. In the structure of the NHIS, one “householder” is selected; “spouses” and “unmarried partners” are identified if present in the household. We combined information on the NHIS household roster with union status and gender to identify individuals in same-sex and different-sex unions. Specifically, we identify individuals as same-sex cohabiting if the “unmarried partner” is the same gender as the householder.4 This approach has the potential for misclassification bias due to miscoded gender and/or partnership status, but this possibility is reduced because NHIS is collected via face-to-face (Carpenter and Gates 2008; McCabe et al. 2010). This approach excludes observations where the respondent or his/her spouse/partner has missing values for their relationship to the household reference person and/or marital status (about 3.8 % of the sample ages 18–65).

Smoking Status

The dependent variable is self-reported cigarette use measured in four categories: never smoker (the reference), former smoker, current everyday smoker, and current somedays smoker. We excluded respondents with missing values for smoking status (about 1 % of respondents ages 18–65). We distinguish between current everyday and current somedays to identify gradation in the quantity of cigarettes smoked, allowing us to identify heavier (i.e., current everyday) and lighter (i.e., current somedays) smokers.

Socioeconomic Status

We examine four major components of SES: educational status, employment status, poverty status, and health insurance status. We categorized years of completed education into four groups: no high school diploma, high school graduate or GED (reference), some college education (no Bachelor’s degree), and college graduate (Bachelor’s degree of higher). We excluded a small number of respondents with missing reports of educational attainment (0.9 % of persons ages 18–65). Employment status in the last week is based on self-reports and was categorized into three groups: currently employed (reference), not employed, and not in labor force. Respondents who did not report their employment status were excluded (about 2 % of persons ages 18–65). Poverty status is based on federal poverty thresholds published annually by the U.S. Census Bureau. The variable was constructed by analysts at NCHS and takes into account self-reported total family income, family size, and the ages and number of children present. Persons who have a total family income below the poverty threshold for families of a given size and age composition are considered “in poverty.” Poverty status was missing for 17.9 % of sample adults ages 18–65. To retain these observations, we conducted the analyses with multiply imputed income to poverty data. Schenker et al. (2006) provide additional information about the procedures NCHS used to create the multiply imputed income to poverty data. The reference group includes persons “not in poverty.” A dichotomous variable indicates whether respondents currently have any private or public source of health insurance coverage (uninsured = 1, insured = 0). Observations with missing health insurance coverage information were listwise deleted (0.35 % of respondents ages 18–65).5

Psychological Distress

We use the Kessler-6 (K6) scale to measure psychological distress. The six items on the K6 have excellent internal consistency and reliability (Kessler et al. 2002). The questions on the K6 are as follows: “During the past 30 days, how often did you feel: (1) so sad that nothing could cheer you up, (2) nervous, (3) restless or fidgety, (4) hopeless, (5) that everything was an effort, and (6) worthless” (MPC 2012). The response options include “none of the time” (coded 0), “a little of the time” (coded 1), “some of the time” (coded 2), “most of the time” (coded 3), and “all of the time” (coded 4). The analyses exclude respondents missing any items on the scale (about 1.5 % of respondents ages 18–65). The K6 was scored by taking the unweighted sum of these six items. Respondents with higher scores on the K6 have higher levels of non-specific psychological distress (range: 0–24).

Other Demographic Covariates

Analyses also control for other demographic characteristics associated with smoking risk and union status, including age in years (centered at the mean) (Brown et al. 2008; U.S. DHHS 2012), gender (Galea et al. 2004; McCabe et al. 2010; Waite and Gallagher, Liu and Reczek 2012), race-ethnicity (non-Hispanic white (reference), non-Hispanic black, Hispanics, and non-Hispanic others) (Galea et al. 2004; Liu and Reczek 2012; Liu et al. 2013), nativity status (native-born (reference) and foreign-born) (Oropesa and Landale 2004; Wilkinson et al. 2005), region of residence (Northwest (reference), Midwest, South, West) (Shopland et al. 1996), and survey year. We listwise deleted a small number of observations with missing information on the demographic control variables (about 0.18 % of respondents ages 18–65).

Statistical Methods

We estimated four multinomial logistic regression models that compare the risk of being an “everyday smoker,” “somedays smoker,” or “former smoker” relative to being a “never smoker” (the baseline category) across union status. In the first model, we assess the relationship between union status and smoking net of basic demographic covariates (e.g., age, gender, race-ethnicity, nativity, region, and survey year). In the second model, we add education as an additional covariate to see how education contributes to the union status differences in smoking. In the third model, we add other SES measures (i.e., employment status, poverty status, and health insurance coverage) as additional covariates to examine the extent to which these SES factors explains any smoking differences by union status. We include education separately from other SES factors for two primary reasons. First, research suggests education and other SES factors work differently to contribute to the relationship between union status and smoking. Education is more likely to be a selection factor into marriage (Ross and Mirowsky 2013), while other SES factors are likely both selection factors and resources accrued in marriage. Second, same-sex cohabiters appear to have higher levels of education, but not necessarily other aspects of SES, than the different-sex married and cohabiting. Therefore, education processes may operate distinctly from other SES factors for same-sex cohabiters. Thus, we hypothesize that same-sex cohabiters’ higher levels of education may be protective against smoking risk while same-sex cohabiters’ disadvantage on other aspects of SES may contribute to smoking risk. We control for education when examining other SES factors because education is more likely to be a precursor to other SES factors. In the final model, in addition to our demographic and SES covariates, we include psychological distress to examine the extent to which psychological distress explain any smoking differences by union status. We control for all SES factors when examining psychological distress because there is an established connection between SES and psychological factors; greater SES is associated with lower levels of psychological distress (Mirowsky and Ross 2003) and in tandem SES and psychological distress relate to lower cigarette use (Galea et al. 2004; Ross et al. 1990). A reduction in the significance level and/or magnitude of the effect of union status across models would suggest that the potential mechanism variables explain the association between union status and smoking. We used partial F tests (Chow 1960) to evaluate the statistical significance of any changes observed in the association between union status and smoking across models; F tests results suggest that all changes in union status differences in smoking are significant across models. Because our analyses incorporated multiply imputed poverty status data, we used the multiple imputation commands available in Stata 12.1 (StataCorp 2012). Additional methodological information on multiple imputation is available elsewhere (Acock 2005; Little and Rubin 1987; Schafer 1999).

Results

Table 1 shows that the distribution of smoking risk, as well as other demographic covariates, vary across union status groups. Table 1 reveals that the proportion of current everyday and somedays smokers is significantly higher among different-sex cohabiters (everyday, 34.2 %; somedays, 6.7 %) and same-sex cohabiters (everyday, 27.4 %; somedays, 6.1 %) than different-sex marrieds (everyday 15.7 %; somedays, 3.5 %); while the proportion of being a never smoker is significantly lower among both different-sex cohabiters (43.1 %) and same-sex cohabiters (43.9 %) than different-sex marrieds (58.0 %); the proportion of being a former smoker is significantly lower among different-sex cohabiters (15.9 %) than different-sex marrieds (22.8 %). Table 1 also shows that compared to the different-sex married, different-sex cohabiters are less likely to be non-Hispanic white or foreign-born, are younger, have lower levels of education, are more likely to be unemployed, uninsured, and in poverty, and experience higher levels of psychological distress. In comparison to the different-sex married, same-sex cohabiters are more likely to be non-Hispanic white, less likely to be foreign-born, are younger, less likely to live in Midwest, more likely to be college graduates, employed, uninsured, and have higher levels of psychological distress.6 When compared with different-sex cohabiters, same-sex cohabiters are less likely to be current everyday smokers but more likely to be former smokers. Same-sex cohabiters are also more likely than different-sex cohabiters to be non-Hispanic white (and less likely to be non-Hispanic black or Hispanic), less likely to be foreign-born or live in Midwest (but more likely to live in Northeast and West), more likely to be college graduates and employed, and less likely to be in poverty or uninsured. Moreover, same-sex cohabiters are older and experience higher level of psychological distress than different-sex cohabiters.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for respondents ages 18–65 by union status, NHIS 1997–2010 (N = 168,514)

| Overall (N = 168,514) %/Mean (95% CI) |

Different-sex married (N = 150,179) %/Mean (95% CI) |

Different-sex cohabiter (N = 17,083) %/Mean (95% CI) |

Same-sex cohabiter (N = 1,252) %/Mean (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking status | ||||

| Current Everyday Smoker | 17.7 (17.4, 18.0) | 15.7+ (15.5, 16.0) | 34.2*+ (33.4, 35.1) | 27.4* (24.4, 30.5) |

| Current Somedays Smoker | 3.8 (3.7, 3.9) | 3.5+ (3.4, 3.6) | 6.7* (6.3, 7.1) | 6.1* (4.6, 7.6) |

| Former Smoker | 22.1 (21.9, 22.4) | 22.8 (22.5, 23.1) | 15.9*+ (15.3, 16.6) | 22.6 (20.0, 25.2) |

| Never Smoked | 56.4 (56.0, 56.7) | 58.0+ (57.6, 58.3) | 43.1* (42.2, 44.0) | 43.9* (40.4, 47.3) |

| Female | 50.7 (50.5, 51.0) | 50.9 (50.6, 51.1) | 50 (49.1, 50.8) | 47.9 (44.4, 51.4) |

| Race-Ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 74.9 (74.4, 75.4) | 75.5+ (75.0, 76.0) | 69.0*+ (68.0, 70.0) | 79.1* (76.7, 81.5) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 8.0 (7.7, 8.3) | 7.4 (7.1, 7.7) | 13.3*+ (12.5, 14.0) | 8.4 (6.7, 10.1) |

| Hispanic | 12.3 (11.9, 12.6) | 12.1+ (11.7, 12.4) | 14.3*+ (13.6, 15.0) | 8.5* (7.0, 10.1) |

| Non-Hispanic other | 4.9 (4.7, 5.0) | 5.0 (4.8, 5.2) | 3.4* (3.1, 3.8) | 4.0 (2.9, 5.1) |

| Foreign-born | 15.8 (15.5, 16.2) | 16.3+ (15.9, 16.7) | 12.0*+ (11.4, 12.6) | 9.0* (7.4, 10.7) |

| Age (mean) | 42.7 (42.6, 42.8) | 43.7+ (43.6, 43.8) | 34.4*+ (34.2, 34.6) | 39.9* (39.2, 40.7) |

| Region | ||||

| Northeast | 17.9 (17.4, 18.4) | 17.8 (17.4, 18.3) | 17.9+ (17.0, 18.9) | 20.8 (17.7, 23.9) |

| Midwest | 25.3 (24.7, 25.9) | 25.2+ (24.5, 25.8) | 27.1*+ (25.9, 28.2) | 18.6* (16.1, 21.1) |

| South | 36.0 (35.3, 36.7) | 36.3 (35.6, 37.0) | 33.4* (32.3, 34.5) | 34.4 (30.7, 38.1) |

| West | 20.8 (20.3, 21.3) | 20.7 (20.1, 21.2) | 21.6+ (20.6, 22.6) | 26.2 (23.2, 29.3) |

| Education | ||||

| No high school diploma | 12.8 (12.4, 13.1) | 12.2+ (11.9, 12.5) | 18.3*+ (17.5, 19.0) | 6.3* (4.9, 7.8) |

| High school graduate | 28.4 (28.0, 28.7) | 27.9+ (27.5, 28.2) | 33.5*+ (32.6, 34.3) | 18.6* (16.2, 21.1) |

| Some college | 28.8 (28.5, 29.1) | 28.6 (28.3, 28.9) | 30.6* (29.8, 31.4) | 30.1 (27.3, 32.9) |

| College graduate | 30.1 (29.6, 30.6) | 31.3+ (30.8, 31.8) | 17.7*+ (16.9, 18.5) | 44.9* (41.6, 48.3) |

| Employment Status | ||||

| Employed | 76.0 (75.7, 76.3) | 75.9+ (75.5, 76.2) | 76.6+ (75.8, 77.4) | 82.2* (79.8, 84.6) |

| Unemployed | 2.7 (2.6, 2.8) | 2.3 (2.2, 2.4) | 6.4*+ (5.9, 6.8) | 3.2 (2.1, 4.2) |

| Not in the labor force | 21.3 (21.0, 21.6) | 21.8+ (21.5, 22.1) | 17.0*+ (16.3, 17.7) | 14.6* (12.3, 16.9) |

| In poverty | 7.3 (7.1, 7.5) | 6.5 (6.3, 6.7) | 14.7*+ (14.0, 15.3) | 7.8 (5.9, 9.6) |

| Uninsured | 14.0 (13.7, 14.2) | 11.9+ (11.6, 12.2) | 32.2*+ (31.3, 33.0) | 17.7* (15.1, 20.3) |

| Psychological distress (mean) | 2.1 (2.1, 2.1) | 2.0+ (2.0, 2.1) | 2.9*+ (2.8, 3.0) | 3.0* (2.7, 3.2) |

Difference comparing with the different-sex married is significant at p < 0.05

Difference comparing with the same-sex cohabiting is significant at p < 0.05

Table 2 shows the adjusted relative risk ratios (ARRR) of reporting being a current “everyday smoker,” current “somedays smoker,” or “former smoker” versus “never smoker” by union status from the multinomial logistic regression models. When interpreting these results, the adjusted relative risk ratios of greater than 1 indicate that in comparison to the different-sex married, individuals from the specific union status group have higher risk of being a current “everyday smoker,” “current somedays smoker,” or a “former smoker” rather than “never smoker”; a relative risk ratios of less than 1 indicates that they have lower risks of having such a smoking status.

Table 2.

Adjusted relative risk ratios of current everyday, current somedays, or former smoking vs. never smoking by union status for respondents ages 18–65, NHIS 1997–2010 (N = 168,514)

| Model 1 | Mode 2 | Model 3 | Mode 4 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Everyday Smoker |

Somedays Smoker |

Former Smoker |

Everyday Smoker |

Somedays Smoker |

Former Smoker |

Everyday Smoker |

Somedays Smoker |

Former Smoker |

Everyday Smoker |

Somedays Smoker |

Former Smoker |

|

| Union Status | ||||||||||||

| Same-sex cohabiter | 2.410* | 2.235* | 1.515* | 3.248* | 2.526* | 1.639* | 3.098* | 2.476* | 1.654* | 2.887* | 2.321* | 1.608* |

| Different-sex cohabiter | 3.294* | 2.324* | 1.430* | 2.773* | 2.172* | 1.362* | 2.523* | 2.067* | 1.384* | 2.447* | 2.006* | 1.363* |

| Female | 0.664* | 0.610* | 0.610* | 0.634* | 0.595* | 0.596* | 0.633* | 0.596* | 0.587* | 0.612* | 0.579* | 0.579* |

| Race-Ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic black | 0.624* | 0.983 | 0.511* | 0.500* | 0.885* | 0.474* | 0.482* | 0.865* | 0.474* | 0.488* | 0.872* | 0.476* |

| Hispanic | 0.539* | 1.390* | 0.682* | 0.312* | 1.103 | 0.583* | 0.289* | 1.066 | 0.592* | 0.296* | 1.080 | 0.595* |

| Non-Hispanic other | 0.780* | 0.778* | 0.603* | 0.878* | 0.855 | 0.637* | 0.880* | 0.863 | 0.636* | 0.880* | 0.861 | 0.637* |

| Foreign-born | 0.533* | 0.718* | 0.700* | 0.517* | 0.700* | 0.703* | 0.478* | 0.668* | 0.712* | 0.499* | 0.690* | 0.720* |

| Age (centered at mean) | 1.006* | 0.991* | 1.042* | 1.004* | 0.991* | 1.041* | 1.006* | 0.992* | 1.040* | 1.006* | 0.992* | 1.041* |

| Region | ||||||||||||

| Midwest | 1.169* | 1.058 | 0.887* | 1.073* | 1.006 | 0.855* | 1.060* | 0.998 | 0.856* | 1.053 | 0.991 | 0.853* |

| South | 1.203* | 0.925 | 0.825* | 1.072* | 0.878* | 0.798* | 1.024 | 0.859* | 0.800* | 1.025 | 0.861* | 0.802* |

| West | 0.757* | 0.896* | 0.838* | 0.755* | 0.866* | 0.819* | 0.734* | 0.853* | 0.820* | 0.724* | 0.844* | 0.816* |

| Year | 0.966* | 0.986* | 0.976* | 0.977* | 0.990* | 0.979* | 0.973* | 0.988* | 0.979* | 0.972* | 0.987* | 0.979* |

| Education | ||||||||||||

| No high school diploma | 1.675* | 1.266* | 1.119* | 1.526* | 1.197* | 1.125* | 1.461* | 1.165* | 1.110* | |||

| Some college | 0.621* | 0.967 | 1.009 | 0.643* | 0.987 | 1.008 | 0.641* | 0.984 | 1.007 | |||

| College graduate | 0.158* | 0.509* | 0.626* | 0.171* | 0.532* | 0.625* | 0.176* | 0.544* | 0.632* | |||

| Employment status | ||||||||||||

| Unemployed | 1.733* | 1.703* | 1.254* | 1.553* | 1.555* | 1.198* | ||||||

| Not in the labor force | 1.032 | 1.013 | 1.096* | 0.932* | 0.940 | 1.061* | ||||||

| In poverty | 1.242* | 1.124* | 0.922* | 1.162* | 1.073 | 0.900* | ||||||

| Uninsured | 1.604* | 1.284* | 0.889* | 1.566* | 1.263* | 0.882* | ||||||

| Psychological distress | 1.081* | 1.071* | 1.038* | |||||||||

| Constant | 0.476* | 0.090* | 0.713* | 0.849* | 0.115* | 0.853* | 0.810* | 0.113* | 0.851* | 0.718* | 0.101* | 0.806* |

The reference groups in the models are as follows: Smoking (Never Smoked), Union Status (Different-Sex Married), Gender (Male), Race-Ethnicity (Non-Hispanic white), Nativity Status (U.S. Born), Region (Northeast), Education (High School Graduate), Employment Status (Currently Employed), Poverty Status (Not in poverty), and Health Insurance Coverage (Insured). Our additional analysis using same-sex cohabiters as the reference group suggests that after controlling for all covariate, there are no significant differences in the risk of being a current somedays and everyday smoker when comparing the same-sex cohabiting and different-sex cohabiting; the different-sex cohabiting are less likely to be former smokers than the same-sex cohabiting

p < 0.05

Results from Model 1, which controls for basic demographic covariates, suggest that both same-sex cohabiters and different-sex cohabiters have a higher risk of being an everyday, somedays, and former smoker in comparison to their different-sex married counterparts. Specifically, the relative risk of reporting being a current everyday smoker is 141.0 % [i.e., (2.410 − 1) × 100 %] higher for same-sex cohabiters and 229.4 % higher for different-sex cohabiters compared to their different-sex married counterparts net of basic demographic covariates. The relative risk of reporting being a current somedays smoker is 123.3 % higher for same-sex cohabiters and 132.4 % higher for different-sex cohabiters compared to their different-sex married counterparts. The relative risk of reporting being a former smoker is 51.5 % higher for same-sex cohabiters and 43.0 % higher for different-sex cohabiters compared to their different-sex married counterparts.

To assess how education, other SES factors, and psychological distress contribute to smoking differences by union status, we add these measures in Models 2–4 and compare the estimated effects of union statuses across models. In Model 2, we add education as an additional covariate. A comparison of results between Models 1 and 2 suggest that after controlling for education, the size of smoking differences between same-sex cohabiters and different-sex marrieds all increased, while the size of smoking differences between different-sex cohabiters and different-sex marrieds all reduced to some extent. This suggest that when compared to the different-sex married, education partially (but not fully) explains different-sex cohabiters’ higher risk of being a current or former smoker, but education does not explain same-sex cohabiters’ higher risk of being a current or former smoker. Education appears to protect same-sex cohabiters from reporting even higher smoking risk.

Next, to assess whether employment status, poverty status, and insurance coverage explain smoking differences by union status, we add these additional covariates in Model 3. A comparison of results between Models 2 and 3 suggests that after controlling for these other SES measures, the size of the difference in both current everyday and somedays smoking for same-sex and different-sex cohabiters significantly decreased, although the size of the difference in former smoking increased for both same-sex and different-sex cohabiters, in comparison to different-sex married. These results suggest that employment status, poverty status, and insurance coverage partially (but not fully) explained the higher risk of being a current (but not former) smoker for both same-sex and different-sex cohabiters when compared with the different-sex married.

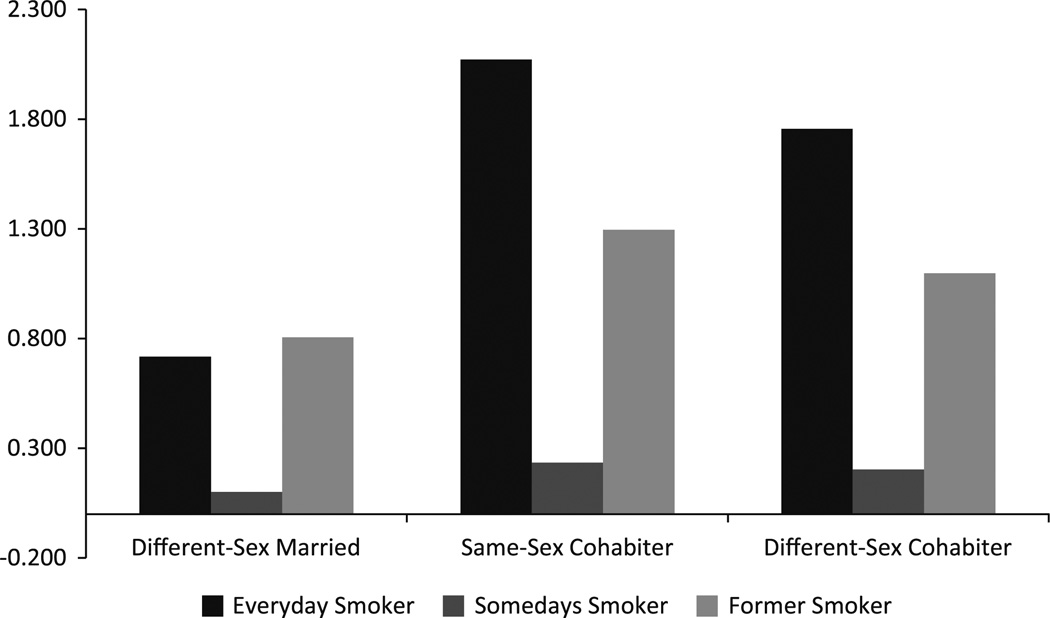

Finally, we add psychological distress as an additional covariates in Model 4. A comparison of results between Models 3 and 4 suggest that after controlling for psychological distress, the size of the difference in all smoking categories between the different-sex married and both same-sex and different-sex cohabiters decreased. This suggests that psychological distress partially (but not fully) explains the higher risk of being a current and former smoker for both same-sex and different-sex cohabiters when compared with the different-sex married. The predicted relative risks of being a current everyday, current somedays, and former smoker rather than never smoker based on the final Model 4 with all covariates controlled are shown in Fig. 1. As shown in Fig. 1, after all covariates are controlled, both same-sex and different-sex cohabiters have higher risks of being in a smoker (current or former) than their different-sex married counterparts. Our additional analysis comparing same-sex cohabiters and different-sex cohabiters controlling for all covariates suggests there are no significant differences in the risk of being a current somedays and everyday smoker; the different-sex cohabiting are less likely to be former smokers than the same-sex cohabiting.

Fig. 1.

Predicted relative risks of being a smoker versus never smoker by union status. The predicted relative risks are based on Model 4 in Table 2. The covariates in Model 4 were fixed to the following values to generate the predicted relative risks: male, Non-Hispanic white, U.S. born, mean age, northeastern U.S., year 1997, high school education, currently employed, not in poverty, has health insurance coverage, and the zero level of psychological distress

Discussion

This study is among the first to compare the smoking prevalence (i.e., never, former, and current smoker) and frequency (i.e., somedays and everyday current smoker) of individuals in different-sex marriages to those in same-sex and different-sex cohabiting unions using data from a nationally representative sample. This study further extends previous research with an examination of whether two central marital resources—SES and psychological distress—explain any of smoking differences across union status. Our results reveal important smoking and union status patterns, calling attention to significant policy and research implications in the linkages between union status, SES, psychological distress, and smoking when considering same-sex unions.

Consistent with our hypotheses (H1a,b), we find that both same-sex and different-sex cohabiters report a higher risk of smoking prevalence and frequency than the different-sex married. Moreover, consistent with our hypothesis (H1c) we find that the same-sex and different-sex cohabiting report similar smoking rates with the exception of former smoking wherein the same-sex cohabiting are at a disadvantage. These findings dovetail with recent research suggesting that cohabiters—both different-sex and same-sex—have similar health outcomes to one another and worse health outcomes than the different-sex married (Denney et al. 2013; Liu and Reczek 2012; Liu et al. 2013). Additionally, our analyses provide new insight into how the role of SES and psychological distress exacerbate and protect from health behavior disparity across union status. Three main findings on the role of SES and psychological distress are discussed below.

First, in regards to the role of education, consistent with our hypothesis (H2b) we found that adding education into our models increased the size of all smoking differences between same-sex cohabiters and different-sex married; in contrast, adding education modestly decreased all differences between different-sex cohabiters and different-sex married. This suggests that when compared to the different-sex married, education partially (but not fully) explains different-sex cohabiters’ higher risk of being a current or former smoker, but education protects same-sex cohabiters’ from experiencing even higher risk of being a current or former smoker. This finding confirms previous work suggesting that same-sex cohabiters’ are protected from even more pronounced health disparities due to their high educational levels (Denney et al. 2013; Liu et al. 2013). Theoretically, same-sex cohabiters likely experience higher levels of education due to selection effects. A majority of same-sex couples have no access to same-sex marriage during the study period (1997–2010). Therefore, the same-sex cohabiting group likely includes those who are highly educated and in committed unions who wish to legally marry but cannot (Reczek et al. 2009; Reczek and Umberson 2012). Thus, while advantaged same-sex cohabiters cannot legally marry and thus remain cohabiters, advantaged different-sex cohabiters select into marriage and out of cohabitation. Importantly, however, the legalization of same-sex marriage in all U.S. states may change the composition of the same-sex cohabiting group to one more similar to the different-sex cohabiting, as more advantaged same-sex cohabiters would be able to select into marriage and out of cohabitation (Lau 2012). Future qualitative and population-based research should attempt to address how cultural, legal, and social changes around same-sex marriage shape SES and health behavior outcomes for individuals in same-sex unions.

Second, when including our other SES factors (i.e., poverty status, employment status, and insurance status) along with education into the model, findings reveal that the size of the difference in both current everyday and somedays smoking for same-sex and different-sex cohabiters significantly decreased, although the size of the difference in former smoking increased, in comparison to different-sex married (consistent with H2a). Results suggest that these SES measures in tandem partially (but not fully) explain the higher risk of being a current smoker for both same-sex and different-sex cohabiters. Our sample clearly shows both same-sex and different-sex cohabiters have lower rates of health insurance, while cohabiters—especially different-sex cohabiters—suffer relatively high rates of poverty and unemployment compared to the different-sex married. Rates of poverty, employment status, and health insurance may promote cohabiters’ greater current smoking risk relative to their different-sex married counterparts with more advantaged SES because these factors are associated with increased self-efficacy (Mirowsky and Ross 2007), access to smoking cessation programs (Cokkinides et al. 2005; Fagan et al. 2007a; Lillard et al. 2007), and workplaces and health insurance initiatives that reduce smoking acceptability and availability (Bauer et al. 2005). Notably, these SES factors do not reduce the risk of being a former smoker—an unexpected finding given the particular importance of access to nicotine dependence and smoking cessation programs that are associated with these SES factors (Manley et al. 2003). Future research should examine other factors (e.g., timing of smoking initiation and access to smoking cessation programs) to explain the results for former smoking.

Third, in line with our hypothesis (H3), we find that psychological distress partially, but does not fully, explains the higher smoking prevalence and frequency of the same-sex and different-sex cohabiting when compared to the different-sex married. Same-sex and different-sex cohabiters likely experience heightened levels of psychological distress and thus higher smoking risk (Baker et al. 2004) than their different-sex married counterparts because of the selection of more stressed individuals into cohabitation rather than marriage, as well as because cohabiting unions experience less stability (Brown 2000; Lau 2012), lower levels of social support from their partner and external network members (Balsam et al. 2008; Meyer 2003; Solomon et al. 2005; Weston 1991), and higher levels of relationship conflict (Kurdek 2001, 2004)—factors associated with psychological distress and in turn higher smoking risk. Additionally, discrimination due to a same-sex status may contribute to higher levels of psychological distress among the same-sex cohabiting (Meyer 2003), playing a role in this smoking disparity. Markers of prestige and greater social support that come with participating in a highly regarded social status such as marriage (Cherlin 2004; Reczek et al. 2009; Lau and Strohm 2011) may alleviate psychological distress. Public health interventions should attempt to ameliorate the higher levels of psychological distress of same and different-sex cohabiters if attempts to reduce smoking among this population are to be successful.

Taken together, when examining all SES and psychological distress variables in our final model, we find that same-sex and different-sex cohabiters still have a higher risk of being in any smoking category compared to the different-sex married. If these tested marital resource factors do not explain smoking disparities across union status, what, then, might account for these differences? It may be that selection factors that are untested in this study are at play. For example, research shows that sexual minorities smoke at higher rates than heterosexuals in the general population (Burgard et al. 2005; IOM 2011). This may be the result of greater smoking initiation as a stress response to discrimination (IOM 2011). Because of this trend, smoking may be considered more normative and thus not seen as a deterrent to selection into a same-sex relationship as is shown among the different-sex married. Additionally, there are important resources beyond SES and psychological distress accrued in different-sex marriage that may contribute to smoking disparities (Cherlin 2004; King and Bartlett 2006; Lau and Strohm 2011). For example, research on different-sex marriage shows that marriage promotes lower levels of substance use via spousal directives to stop smoking (i.e., direct social control) and the introduction of new norms to “clean up one’s act” (i.e., indirect social control) (Derrick et al. 2013; DiMatteo 2004; Duncan et al. 2006; Laub et al. 1998; Reczek and Umberson 2012; Umberson 1987). Same-sex and different-sex cohabiting individuals may not experience analogous social control onto their smoking habits as do their different-sex married counterparts (Reczek 2012), and therefore would not see analogous reductions in smoking. Our study is unable to fully explain why same-sex and different-sex cohabiters experience higher rates of smoking compared to the different-sex married; public policy and future research should work towards determining what factors account for higher rates of cigarette use among these cohabiting populations beyond those tested in this study (Mays et al. 2002).

Limitations and Conclusion

This study is among the first to address disparities in smoking prevalence and frequency across same-sex and different-sex married and cohabiting unions at the population level, however, it has important limitations that provide future research directives. We note that the in-person NHIS design may make individuals reluctant to report a same-sex person as a “partner.” This may be particularly the case for racial-ethnic minorities and those with lower SES (Moore 2011). Therefore our sample may underestimate and skew the same-sex cohabiting population in the U.S. However, our percentages of individuals in same-sex unions is in line with other national data (see footnote 6; Gates 2013; U.S. Census 2011). Due to the cross-sectional nature of our data, we are unable to measure causality; future longitudinal data collection efforts should be undertaken to fully examine both causality and selection processes in these associations for same-sex cohabiters. A measure of relationship duration (i.e., years cohabiting) would also provide additional insights into the relationship between union status and smoking that we cannot address due to data limitations. In addition, the NHIS does not currently collect data on sexual minority identity, thus, we are unable to identify gay and lesbian self-identified respondents who are not in cohabiting relationships (i.e., never-married single, divorced, widowed). Therefore, we excluded these single groups from the present study. Research suggests gay and lesbian identified people have higher rates of smoking and other risky health behaviors than heterosexuals (Austin et al. 2013; Burgard et al. 2005; IOM 2011; Meyer 2003) and future work should attempt to understand how risky health behavior, including smoking risk, of individuals in same-sex unions compare to that of the general sexual minority population (IOM 2011).

This study is also limited in that we restrict our sample to adults under the age of 65. We do so because previous research suggests that union status (Brown et al. 2008), same-sex relationships (Reczek et al. 2009), and smoking prevalence and frequency have different meaning and consequences for older adults (U.S. DHHS 2012; Dube et al. 2010; Kandel et al. 2011). However, future research should examine how age and cohort differences influence the relationship between same-sex union status and smoking risk. Moreover, there are significant gender and race-ethnicity differences in smoking status (Galea et al. 2004; McCabe et al. 2010), the health consequences of marriage (Liu and Reczek 2012; Waite and Gallagher 2000), and the meaning of a same-sex relationships (Moore 2011). We performed race-ethnicity and gender interactions (available upon request, results reported in footnote 7), however, these interactions should be interpreted with caution given the small sample size of the some racial-ethnic same-sex cohabiting groups.7 These interactions lay the groundwork for future research to examine the racial-ethnic and gender differences in the relationship between union status and smoking status. Finally, we do not include an analysis of same-sex married individuals in the present study due to the small sample size of the same-sex married in the NHIS. However, additional analysis (not shown in this paper, but available upon request) show that the same- and different-sex married report a similar risk of being in each smoking prevalence and frequency category. Moreover, none of our tested mechanisms alter this association (see footnote 4). This preliminary analysis on same-sex married individuals serves as a first step in research on same-sex marriage and health behavior, revealing the possibility that some of the central marital benefits hypothesized to promote decreased smoking risk in different-sex marriage may be also present in same-sex marriage (Lau and Strohm 2011). Future research should attempt to confirm these preliminary findings with other national datasets.

Despite limitations, this study makes important contributions that inform policy and scholarship on smoking prevalence and frequency disparities across same-sex and different-sex union statuses (Ayanian et al. 2000; Heck and Jacobson 2006; Wilper et al. 2008). This study advances a line of research suggesting that same-sex and different-sex cohabiters experience disadvantage that is not fully explained by SES and psychological factors; same-sex cohabiters may in fact be protected by their advantaged education status (Lau and Strohm 2011; Gruskin et al. 2001; Mayer et al. 2008). Same-sex cohabiters may additionally experience disadvantage on other health behaviors and facets of health—such as diet, exercise, alcohol use, and body weight (Austin et al. 2013; Denney et al. 2013; Liu et al. 2013; U.S. DHHS 2000b)—and future research should address these critical areas of health. It is important to note that because same-sex cohabiters do not have the option to marry in most U.S. states, same-sex cohabiters may be at amplified avoidable risk. Future research and subsequent public policy initiatives should examine how the effects of legal and institutional policies shape the smoking risk of same-sex and different-sex cohabiters in order to promote lower smoking rates among this population.

Footnotes

We include both everyday and somedays smoker as measures for “heavy” and “moderate” smoking.

We ran our analysis with a sample composed of individuals 25–65 in order to confine our analysis to those less likely to be transitional smokers (i.e., young adults), and to those most likely to have completed their highest level of education. This analysis allowed us to more securely test the role of SES with completed education data. Results in the main analysis were consistent with results in this secondary analysis (available upon request).

Multiple imputation was performed by NCHS to impute missing values on poverty status, which has relatively high nonresponse rate in the 1997–2010 NHIS (about 24.6 percent overall). We chose not to multiply impute missing values for the other variables in our models because these variables had very low nonresponse rates, and because listwise deletion introduces minimal bias when data missing completely at random (MCAR) or missing at random (MAR)—especially when nonresponse rates are low (Allison 2002; Pigott 2001). Ancillary analyses (available upon request) suggest that missing values in the 1997–2010 NHIS Sample Adult Files are more or less randomly distributed.

Same-sex married individuals are also identifiable in the NIHS when the “spouse” is identified as the same gender as the householder. The cross-sectional pooled data extends from 1997 to 2010, therefore, there is varied same-sex marriage legality across the study period. For example, a minority of U.S. states legally recognize same-sex marriage, and the first state to legalize same-sex marriage did so in 2004. Due to data limitations, we have no way to determine whether individuals are legally married in the state they currently reside. Therefore, it is plausible that some individuals in the same-sex married group are not legally married. This especially applies to persons interviewed prior to 2004, before marriage was legal in any state in the U.S. Because of these factors, we exclude the same-sex married (N = 196) from our analysis. However, we perform secondary analyses including the same-sex married group. We find that there are no differences in smoking risk when comparing the same-sex married and different-sex married.

The meaning of having or not having health insurance in the analyzed data is complex given the varying state-based laws for domestic partner health insurance. A lack of health insurance may be the result of lack of access to domestic partnership or marriage, a lack of employer-based insurance, or low income. Future work should attempt to clarify the meaning of this measure among same- and different-sex cohabiters.

Descriptive statistics reported here are generally consistent with previous population-based estimates of same-sex cohabiters (Denney et al. 2013; Gates 2013; Liu et al. 2013).

In terms of race interactions, we found that the difference in everyday smoking between the different-sex cohabiting and different-sex marrieds is smaller among blacks and Hispanics than whites; difference in someday smoking between different-sex cohabiting and different-sex marrieds is smaller among Hispanics and larger among the “other” racial-ethnic group than whites; difference in former smoking between different-sex cohabiting and different-sex married is smaller among blacks and larger among “other” racial groups races than whites. There were no racial differences in terms of our findings comparing same-sex cohabiting to different-sex married. In terms of gender interactions, the differences in everyday, someday, and former smoking between different-sex cohabiting and different-sex married is stronger among women than men; difference in former smoking between the same-sex cohabiting and different-sex married is stronger among women than men.

Contributor Information

Corinne Reczek, Email: Reczek.2@osu.edu, Departments of Sociology and Women’s, Gender, and Sexualities Studies, The Ohio State University, 164 Townshend Hall, 1885 Neil Avenue Mall, Columbus, OH 43210-1222, USA.

Hui Liu, Email: liuhu@msu.edu, Department of Sociology, Michigan State University, Berkey Hall, 509 E. Circle Drive 316, East Lansing, MI 48824, USA.

Dustin Brown, Email: dustin.c.brown2@gmail.com, Population Studies Center, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, 426 Thompson Street, Ann Arbor, MI 48104-1248, USA.

References

- Acock AC. Working with missing values. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:1012–1028. [Google Scholar]

- Ahituv A, Lerman RI. How do marital status, work effort, and wage rates interact? Demography. 2007;44:623–647. doi: 10.1353/dem.2007.0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison PD. Missing data. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson G, Noack T, Seierstad A, Weedon-Fekjaer H. The demographics of same-sex marriages in Norway and Sweden. Demography. 2006;43:79–98. doi: 10.1353/dem.2006.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnetz BB, Brenner SO, Levi L, Hjelm R, Petterson IL, Wasserman J, et al. Neuroendocrine and immunologic effects of unemployment and job insecurity. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 2010;55:76–80. doi: 10.1159/000288412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ash MA, Badgett MVL. Separate and unequal: The effect of unequal access to employment-based health insurance on same sex and unmarried different sex couples. Contemporary Economic Policy. 2006;24:582–599. [Google Scholar]

- Austin SB, Nelson LA, Birkett MA, Calzo JP, Everett B. Eating disorder symptoms and obesity at the intersections of gender, ethnicity, and sexual orientation in US high school students. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103:e16–e22. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayanian JZ, Weissman JS, Schneider EC, Ginsburg JA, Zaslavsky AM. Unmet health needs of uninsured adults in the United States. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284:2061–2069. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.16.2061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachman JG, O’Malley PM, Schulenberg JE, Johnston LD, Ludden AB, Merline AC. The decline of substance use in young adulthood: Changes in social activities, roles, and beliefs. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bachman JG, Wadsworth KN, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD, Schulenberg JE. Smoking, drinking, and drug use in young adulthood. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Badgett MVL. Money, myths, and change: The economic lives of lesbians and gay men. New York: NYU Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Badgett MVL, Durso LE, Schneemaum A. New patterns of poverty in the lesbian, gay, bisexual community. The Williams Institute UCLA School of Law. [Retrieved online 6/4/2013];2013 from http://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/LGB-Poverty-Update-Jun-2013-2013.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Baker TB, Brandon TH, Chassin L. Motivational influences on cigarette smoking. Annual Review of Psychology. 2004;55:463–491. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.142054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsam KF, Beauchaine TP, Rothblum ED, Solomon SE. Three-year follow-up of same-sex couples who had civil unions in Vermont, same-sex couples not in civil unions, and heterosexual married couples. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:102–116. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbeau EM, Krieger N, Soobader M-J. Working class matters: Socioeconomic disadvantage, race/ethnicity, gender, and smoking in NHIS 2000. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94:269–278. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.2.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer JE, Hyland A, Li Q, Steger C, Cummings KM. A longitudinal assessment of the impact of smoke-free worksite policies on tobacco use. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95:1024–1029. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.048678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker H. A treatise on the family. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Biddle S, Mutrie N. Psychology of physical activity: Determinants, well-being and interventions. Psychology Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Black D, Gates G, Sanders SG, Taylor L. Demographics of the gay and lesbian population in the United States: Evidence from available systematic data sources. Demography. 2000;37:139–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black DA, Makar HR, Sanders SG, Taylor LJ. The effects of sexual orientation on earnings. Industrial and Labor Relations Review. 2003;56:449–469. [Google Scholar]

- Black DA, Sanders SG, Taylor LJ. The economics of lesbian and gay families. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2007;21:53–70. [Google Scholar]

- Blekesaune M. Partnership transitions and mental distress: Investigating temporal order. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2008;70:879–890. [Google Scholar]

- Brines J, Joyner K. The ties that bind: Principles of cohesion in cohabitation and marriage. American Sociological Review. 1999;64:333–355. [Google Scholar]

- Brown SL. The effect of union type on psychological well-being: Depression among cohabitors versus marrieds. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2000;41:241–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SL, Van Hook J, Glick JE. Generational differences in cohabitation and marriage in the U.S. Population Research and Policy Review. 2008;27:531–550. doi: 10.1007/s11113-008-9088-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchmueller T, Carpenter CS. Disparities in health insurance coverage, access, and outcomes for individuals in same-sex versus different-sex relationships, 2000–2007. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:489–495. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.160804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffie WC. Public health implications of same-sex marriage. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101:986–990. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgard SA, Cochran SD, Mays VM. Alcohol and tobacco use patterns among heterosexually and homosexually experienced California women. Drug and Alcohol Dependency. 2005;77:61–70. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter C, Gates GJ. Gay and lesbian partnerships: Evidence from California. Demography. 2008;45:573–590. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr D, Springer KW. Advances in families and health research in the 21st century. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72:743–761. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital Signs: Smoking-attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and productivity losses—United States, 2000–2004. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2008;57:1226–1228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital signs: current cigarette smoking among adults aged > 18 years with mental illness—United States, 2009–2011. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2013;62:81–87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin A. The deinstitutionalization of American marriage. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;66:848–861. [Google Scholar]

- Chow GC. Tests of equality between sets of coefficients in two linear regressions. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society. 1960;28:591–605. [Google Scholar]

- Christakis NA, Fowler JH. The collective dynamics of smoking in a large social network. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;358:2249–2258. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0706154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopoulou R, Ha J, Jaber A, Lillard DR. Dying for a smoke: How much does differential mortality of smokers affect estimated life-course smoking prevalence? Preventive Medicine. 2011;52:66–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun H, Lee I. Why do married men earn more: Productivity or marriage selection? Economic Inquiry. 2001;39:307–319. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen RA, Martinez ME. Health insurance coverage: Early release of estimates From the National Health Interview Survey, January–March 2012. NOTES, 2007. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Cokkinides V, Bandi P, McMahon C, Jemal A, Glynn T, Ward E. Tobacco control in the United States—recent progress and opportunities. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2009;59:352–365. doi: 10.3322/caac.20037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cokkinides VE, Ward E, Jemal A, Thun MJ. Under-use of smoking-cessation treatments: Results from the national health interview survey, 2000. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2005;28:119–122. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler DM, Lleras-Muney A. Understanding differences in health behaviors by education. Journal of Health Economics. 2010;29:1–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Walque D. Does education affect smoking behaviors?: Evidence using the Vietnam draft as an instrument for college education. Journal of Health Economics. 2007;26:877–895. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Walque D. Education, information, and smoking decisions: Evidence from smoking histories in the United States, 1940–2000. Journal of Human Resources. 2010;45:682–717. [Google Scholar]

- Denney JT, Gorman BK, Barrera CB. Families, resources, and adult health where do sexual minorities fit? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2013;54:46–63. doi: 10.1177/0022146512469629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derrick JL, Leonard KE, Homish GG. Perceived partner responsiveness predicts decreases in smoking over the first nine years of marriage. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2013 doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMatteo M. Social support and patient adherence to medical treatment: A meta-analysis. Health Psychology. 2004;23:207–218. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.2.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube SR, McClave A, James C, Caraballo R, Kaufmann R, Pechacek T. Vital signs: Current cigarette smoking among adults aged ≥ 18 years. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2010;59:1135–1140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Wilkerson B, England P. Cleaning up their act: The effects of marriage and cohabitation on licit and illicit drug use. Demography. 2006;43:691–710. doi: 10.1353/dem.2006.0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan P, Moolchan ET, Lawrence D, Fernander A, Ponder PK. Identifying health disparities across the tobacco continuum. Addiction. 2007a;102:5–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01952.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan P, Shavers V, Lawrence D, Gibson JT, Ponder P. Cigarette smoking and quitting behaviors among unemployed adults in the United States. Nicotine Tobacco Research. 2007b;9:241–248. doi: 10.1080/14622200601080331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein A, Taubman S, Wright B, Bernstein M, Gruber J, Newhouse JP, et al. The Oregon Health Insurance Experiment: Evidence from the first year. The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2012;127:1057–1106. doi: 10.1093/qje/qjs020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu H, Goldman N. Incorporating health into models of marriage choice: Demographic and sociological perspectives. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1996;58:740–758. [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Nandi A, Vlahov D. The social epidemiology of substance use. Epidemiologic Reviews. 2004;26:36–52. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxh007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates GJ. Same-sex and different-sex couples in the American Community Survey: 2005–2011. [Retrieved on March 1, 2013];The Williams Institute. 2013 from http://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/research/census-lgbt-demographics-studies/ss-and-ds-couples-in-acs-2005-2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gilman SE, Abrams DB, Buka SL. Socioeconomic status over the life course and stages of cigarette use: Initiation, regular use, cessation. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2003;57:802–808. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.10.802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman SE, Martin LT, Abrams DB, Kawachi I, Kubzansky L, Loucks EB. Educational attainment and cigarette smoking: A causal association? International Journal of Epidemiology. 2008;37:615–624. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman N. Marriage selection and mortality patterns: Inferences and fallacies. Demography. 1993;30:189–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gove WR, Hughes M, Style CB. Does marriage have positive effects on the psychological well-being of the individual? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1983;24:122–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graefe DR, Lichter DT. Life course transitions of American children: Parental cohabitation, marriage, and single motherhood. Demography. 1999;36:205–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham H, Inskip HM, Francis B, Harman J. Pathways of disadvantage and smoking careers: Evidence and policy implications. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2006;60(suppl 2):ii7–ii12. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.045583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruskin EP, Greenwood GL, Matevia M, Pollack LM, Bye LL. Disparities in smoking between the lesbian, gay, bisexual population and the general population in California. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:1496–1502. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.090258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruskin EP, Hart S, Gordon N, Ackerson L. Patterns of cigarette smoking and alcohol use among lesbians and bisexual women enrolled in a large health maintenance organization. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:976–979. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S. The effects of transitions in marital status transitions on men’s performance of housework. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1999;61:700–711. [Google Scholar]

- Haskey J. Cohabitation in Great Britain: Past, present and future trends-and attitudes. Population Trends-London. 2001;103:4–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton TB. Factors contributing to increasing marital stability in the United States. Journal of Family Issues. 2002;23:392–409. [Google Scholar]

- Heck JE, Jacobson JS. Asthma diagnosis among individuals in same-sex relationships. Journal of Asthma. 2006;43:579–584. doi: 10.1080/02770900600878289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heck JE, Sell RL, Gorin SS. Health care access among individuals involved in same-sex relationships. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:1111–1118. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.062661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimdal KR, Houseknecht SK. Cohabiting and married couples’ income organization: Approaches in Sweden and the United States. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;65:525–538. [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz AV, White HR. The relationship of cohabitation and mental health: A study of a young adult cohort. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1998;60:505–514. [Google Scholar]

- Huisman M, Kunst AE, Mackenbach JP. Inequalities in the prevalence of smoking in the European Union: Comparing education and income. Preventive Medicine. 2005;40:756–764. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummer RA, Nam CB, Rogers RG. Adult mortality differentials associated with cigarette smoking in the USA. Population Research and Policy Review. 1998;17:285–304. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine of the National Academies (IOM) The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: Building a foundation for better understanding. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel D, Schaffran C, Hu M-C, Thomas Y. Age-related differences in cigarette smoking among whites and African-Americans: evidence for the crossover hypothesis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;118:280–287. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, Hiripi E, Mroczek DK, Normand SLT, et al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine. 2002;32:959–976. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King M, Bartlett A. Continuing professional education: What same-sex civil partnerships may mean for health. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2006;60:188–191. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.040410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler HP, Behrman JR, Skytthe A. Partner + children = happiness? The effects of partnerships and fertility on well-being. Population and Development Review. 2005;31:407–445. [Google Scholar]

- Kurdek LA. Differences between heterosexual-nonparent couples and, gay, lesbian, and heterosexual-parent couples. Journal of Family Issues. 2001;22:727–754. [Google Scholar]

- Kurdek LA. Are gay and lesbian cohabiting couples “really” different from heterosexual married couples? Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;66:880–900. [Google Scholar]

- Kurdek LA. The allocation of household labor by partners in gay and lesbian couples. Journal of Family Issues. 2007;28:132–148. [Google Scholar]

- Lau CQ. The stability of same-sex cohabitation, different-sex cohabitation, and marriage. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2012;74:973–988. [Google Scholar]

- Lau H, Strohm CQ. The effects of legally recognizing same-sex unions on health and well-being. Law and Inequality. 2011;29:509–528. [Google Scholar]

- Laub J, Nagin DS, Sampson RJ. Trajectories of change in criminal offending: Good marriages and the desistence process. American Sociological Review. 1998;64:225–238. [Google Scholar]

- Layte R, Whelan CT. Explaining social class inequalities in smoking: the role of education, self-efficacy, and deprivation. European Sociological Review. 2009;25(4):399–410. [Google Scholar]

- Lee JGL, Griffin GK, Melvin CL. Tobacco use among sexual minorities in the USA, 1987 to May 2007: A systematic review. Tobacco Control. 2009;18:275–282. doi: 10.1136/tc.2008.028241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichter DT, Graefe DR, Brown JB. Is marriage a panacea? Union formation among economically disadvantaged unwed mothers. Social Problems. 2003;50(1):60–86. [Google Scholar]

- Lillard DR, Plassmann V, Kenkel D, Mathios A. Who kicks the habit and how they do it: Socioeconomic differences across methods of quitting smoking in the USA. Social Sciences and Medicine. 2007;64:2504–2519. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.02.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG. Epidemiological sociology and the social shaping of population health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2008;49:367–384. doi: 10.1177/002214650804900401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;30:80–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJ, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. New York: Wiley; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Reczek C. Cohabitation and U.S. adult mortality: An examination by gender and race. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2012;74:794–811. [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Reczek C, Brown D. Same-sex cohabitors and health: The role of race-ethnicity, gender, and socioeconomic status. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2013;54:25–45. doi: 10.1177/0022146512468280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manley MW, Griffin T, Foldes SS, Link CC, Sechrist RAJ. The role of health plans in tobacco control. Annual Review of Public Health. 2003;23:237–266. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.24.100901.140838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maralani V. Educational inequalities in smoking: The role of initiation versus quitting. Social Science and Medicine. 2013;84:129–137. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer KH, Bradford JB, Makadon HJ, Stall R, Goldhammer H, Landers S. Sexual and gender minority health: What we know and what needs to be done. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98:989–995. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.127811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mays VM, Yancey AK, Cochran SD, Weber M, Fielding JE. Heterogeneity of health disparities among African American, Hispanic, and Asian American women: Unrecognized influences of sexual orientation. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92:632–639. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.4.632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Bostwick WB, Hughes TL, West BT, Boyd CJ. The relationship between discrimination and substance use disorders among lesbian, gay, bisexual adults in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:1946–1952. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.163147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]