Abstract

Background

Recent US and UK clinical practice guidelines recommend that second‐generation antidepressants should be considered amongst the best first‐line options when drug therapy is indicated for a depressive episode. Systematic reviews have already highlighted some differences in efficacy between second‐generation antidepressants. Citalopram, one of the first selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) introduced in the market, is one of these antidepressant drugs that clinicians use for routine depression care.

Objectives

To assess the evidence for the efficacy, acceptability and tolerability of citalopram in comparison with tricyclics, heterocyclics, other SSRIs and other conventional and non‐conventional antidepressants in the acute‐phase treatment of major depression.

Search methods

We searched The Cochrane Collaboration Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Controlled Trials Register and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials up to February 2012. No language restriction was applied. We contacted pharmaceutical companies and experts in this field for supplemental data.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials allocating patients with major depression to citalopram versus any other antidepressants.

Data collection and analysis

Two reviewers independently extracted data. Information extracted included study characteristics, participant characteristics, intervention details and outcome measures in terms of efficacy (the number of patients who responded or remitted), patient acceptability (the number of patients who failed to complete the study) and tolerability (side‐effects).

Main results

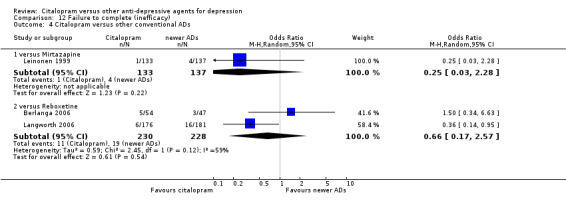

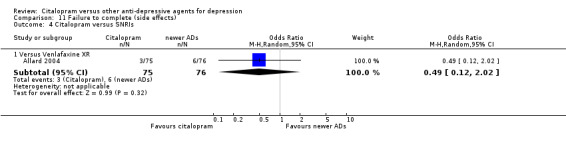

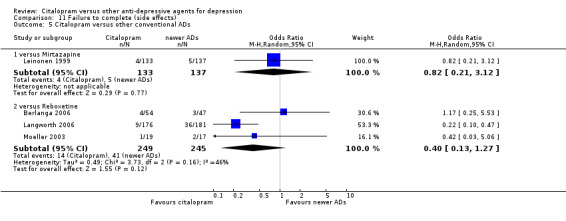

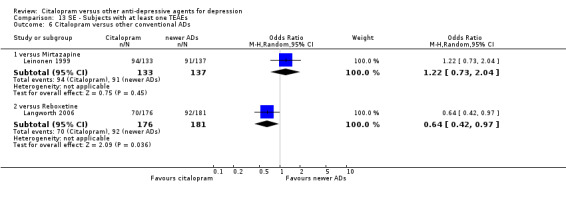

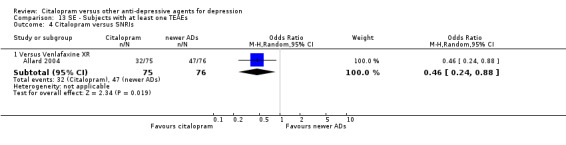

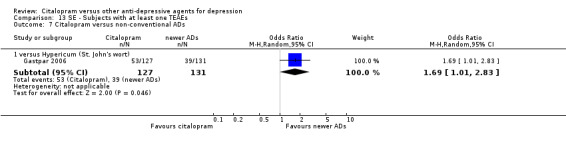

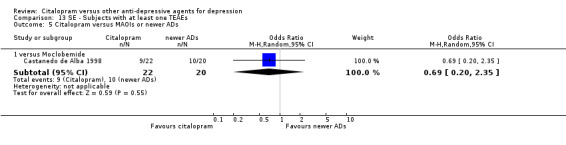

Thirty‐seven trials compared citalopram with other antidepressants (such as tricyclics, heterocyclics, SSRIs and other antidepressants, either conventional ones, such as mirtazapine, venlafaxine and reboxetine, or non‐conventional, like hypericum). Citalopram was shown to be significantly less effective than escitalopram in achieving acute response (odds ratio (OR) 1.47, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.08 to 2.02), but more effective than paroxetine (OR 0.65, 95% CI 0.44 to 0.96) and reboxetine (OR 0.63, 95% CI 0.43 to 0.91). Significantly fewer patients allocated to citalopram withdrew from trials due to adverse events compared with patients allocated to tricyclics (OR 0.54, 95% CI 0.38 to 0.78) and fewer patients allocated to citalopram reported at least one side effect than reboxetine or venlafaxine (OR 0.64, 95% CI 0.42 to 0.97 and OR 0.46, 95% CI 0.24 to 0.88, respectively).

Authors' conclusions

Some statistically significant differences between citalopram and other antidepressants for the acute phase treatment of major depression were found in terms of efficacy, tolerability and acceptability. Citalopram was more efficacious than paroxetine and reboxetine and more acceptable than tricyclics, reboxetine and venlafaxine, however, it seemed to be less efficacious than escitalopram. As with most systematic reviews in psychopharmacology, the potential for overestimation of treatment effect due to sponsorship bias and publication bias should be borne in mind when interpreting review findings. Economic analyses were not reported in the included studies, however, cost effectiveness information is needed in the field of antidepressant trials.

Keywords: Humans; Antidepressive Agents; Antidepressive Agents/therapeutic use; Antidepressive Agents, Second‐Generation; Antidepressive Agents, Second‐Generation/therapeutic use; Citalopram; Citalopram/therapeutic use; Cyclohexanols; Cyclohexanols/therapeutic use; Depression; Depression/drug therapy; Morpholines; Morpholines/therapeutic use; Paroxetine; Paroxetine/therapeutic use; Reboxetine; Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors; Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors/therapeutic use; Venlafaxine Hydrochloride

Plain language summary

Citalopram versus other antidepressants for depression

Major depression is a severe mental illness characterised by a persistent and unreactive low mood and loss of all interest and pleasure, usually accompanied by a range of symptoms including appetite change, sleep disturbance, fatigue, loss of energy, poor concentration, psychomotor symptoms, inappropriate guilt and morbid thoughts of death. Antidepressant drugs remain the mainstay of treatment in moderate‐to‐severe major depression. During the last 20 years, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have progressively become the most commonly prescribed antidepressants. Citalopram, one of the first SSRIs introduced in the market, is the racemic mixture of S‐ and R‐enantiomer. In the present review we assessed the evidence for the efficacy, acceptability and tolerability of citalopram in comparison with all other antidepressants in the acute‐phase treatment of major depression. Thirty‐seven randomised controlled trials (more than 6000 participants) were included in the present review. In terms of efficacy, citalopram was more efficacious than other reference compounds like paroxetine or reboxetine, but worse than escitalopram. In terms of side effects, citalopram was more acceptable than older antidepressants, like tricyclics. Based on these findings, we conclude that clinicians should focus on practical or clinically relevant considerations including differences in efficacy and side‐effect profiles.

Background

Description of the condition

Major depression is generally diagnosed when a persistent and unreactive low mood and/or loss of interest and pleasure are accompanied by a range of symptoms including appetite loss, insomnia, fatigue, loss of energy, poor concentration, psychomotor symptoms, inappropriate guilt and morbid thoughts of death (APA 1994). It was the third leading cause of burden among all diseases in the year 2004 and it is expected to be the greatest cause in 2030 (WHO 2006). This condition is associated with marked personal, social and economic morbidity, loss of functioning and productivity, and creates significant demands on service providers in terms of workload (APA 2000; NICE 2010). Although pharmacological and psychological interventions are both effective for major depression, in primary and secondary care settings antidepressant (AD) drugs remain the mainstay of treatment in moderate to severe major depression (APA 2006; NICE 2010). Amongst ADs many different agents are available, including tricyclics (TCAs), monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin‐noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs, such as venlafaxine, duloxetine and milnacipran), and other agents (mirtazapine, reboxetine, bupropion). During the last 20 years, ADs prescription has dramatically risen in western countries, mainly because of the increasing prescription of SSRIs which have progressively become the most commonly prescribed ADs (Ciuna 2004). SSRIs are generally more acceptable than TCAs, and there is evidence of similar efficacy (NICE 2010). However, head‐to‐head comparisons have provided contrasting findings (Cipriani 2006).

Description of the intervention

Citalopram hydrobromide is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) that has been available as an antidepressant since the 1980s in US and Europe. It is also available in many countries for anxiety disorders, including obsessive‐compulsive disorder and social anxiety disorder. Citalopram is a racemic dicyclic phthalane derivative designated (±)‐1‐(3‐dimethylaminopropyl)‐1‐(4‐fluorophenyl)‐1,3‐dihydroisobenzofuran‐5carbonitrile (www.fda.gov). Citalopram has a chemical structure unrelated to that of other SSRIs or of tricyclic, tetracyclic, or other available antidepressant agents. Therefore, some differential clinical potency may be expected, not only between the drugs classes but also among the SSRIs.

How the intervention might work

Inhibition of the neuronal transporter for serotonin has long been established as one of the mechanisms of action of numerous antidepressants (Barker 1995). Citalopram is a dicyclic phthalide derivative and its effect is due to a specific inhibition of the re‐uptake of serotonin in the brain (Stahl 1994). Citalopram is a highly selective and potent SSRI with minimal effects on the neuronal reuptake of norepinephrine (NE) and dopamine (DA). Citalopram has no or very low affinity for a series of receptors including serotonin 5‐HT1A, 5‐HT2, dopamine D1, and D2, a1‐, a2‐, b‐adrenergic, histamine H1, muscarinic cholinergic, benzodiazepine, gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA) and opioid receptors (Stahl 1998). Citalopram has a pronounced tissue distribution and its binding to human plasma proteins is about 80%. Maximum concentration in blood is reached after one to six hours and the steady state concentration in blood is reached after one to two weeks. Protein binding is about 14L/k and the half‐life is about 36 hours, (possibly longer for the elderly). The drug is metabolized before it is excreted. Citalopram is metabolized in the liver and the biotransformation of citalopram to its demethyl metabolites depends on both CYP2C19 and CYP3A4, with a small contribution from CYP2D6.

Why it is important to do this review

To shed light on the field of antidepressant trials and the treatment of major depression, a group of researchers agreed to join forces under the rubric of the Meta‐Analyses of New Generation Antidepressants Study Group (MANGA Study Group) to systematically review all available evidence for each specific newer antidepressant. We have up to now completed some individual reviews about fluoxetine (Cipriani 2005a), sertraline (Cipriani 2009b), escitalopram (Cipriani 2009c), milnacipran (Nakagawa 2009), fluvoxamine (Omori 2010), and a number of other reviews are now underway. Thus, the aim of the present review is to assess the evidence for the efficacy and tolerability of citalopram in comparison with TCAs, heterocyclics, MAOIs, SSRIs, SNRIs and other antidepressants in the acute‐phase treatment of major depression.

Objectives

(1) To determine the efficacy of citalopram in comparison with other antidepressants in alleviating the acute symptoms of major depressive disorder. (2) To review acceptability of treatment with citalopram in comparison with other antidepressants. (3) To investigate the adverse effects of citalopram in comparison with other antidepressants.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials that compared citalopram with all other active antidepressants as monotherapy in the acute phase treatment of depression. Quasi‐randomised trials, such as those allocating by using alternate days of the week, were excluded. For trials which have a cross‐over design, we only considered results from the first randomisation period.

Types of participants

The review included trials of patients 18 years or older, of both sexes, with a primary diagnosis of depression and studies adopting standardised criteria (DSM‐III / DSM‐III‐R, DSM‐IV (APA 2000), ICD‐10 (WHO 1992), Feighner criteria (Feighner 1972) or Research Diagnostic Criteria (Spitzer 1972) to define patients suffering from unipolar major depression. We excluded studies using ICD‐9, as it has only disease names and no diagnostic criteria. We included the following subtypes of depression: chronic, with catatonic features, with melancholic features, with atypical features, with postpartum onset, and with seasonal pattern. We also included studies in which up to 20% of patients presented depressive episodes in bipolar affective disorder. A concurrent secondary diagnosis of another psychiatric disorder was not considered an exclusion criterion. A concurrent primary diagnosis of Axis I or II disorders was an exclusion criterion. AD trials in depressive patients with a serious concomitant medical illness were excluded.

Types of interventions

We examined citalopram intervention in comparison with conventional treatment of acute depression. We also examined citalopram intervention in comparison with non‐conventional antidepressants (herbal products or other non‐conventional antidepressants. We excluded trials in which citalopram was compared with another type of psychopharmacological agent (i.e., anxiolytics, anticonvulsants, antipsychotics or mood‐stabilizers). We also excluded trials in which citalopram was used as an augmentation strategy.

Eligible intervention:

1. Citalopram: any dose and pattern of administration.

Eligible comparators:

2. Conventional antidepressants: any dose and mode or pattern of administration. 2.1 TCAs 2.2 Heterocyclics 2.3 SSRIs 2.4 SNRIs 2.5 MAOIs or newer ADs 2.6 Other conventional psychotropic drugs

3. Non‐conventional antidepressants 3.1 Herbal products 3.2 Other non‐conventional antidepressants

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

1. Response ‐ acute phase

We examined trials regarding the number of patients (1) who responded to treatment by showing a reduction of at least 50% on the Hamilton Rating Scale for depression (HRSD) (Hamilton 1960), Montgomery Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (Montgomery 1979), or any other depression scale, depending on the study authors' definition or (2) who were "much or very much improved" (score 1 or 2) on the CGI‐Improvement scale (Guy 1976) out of the total number of randomised patients. Where both were provided, we preferred the former criteria for judging response. The original authors' definitions of response and remission were not used in this review, to avoid possible outcome reporting bias (Furukawa 2007).

As studies report response rates at various time points throughout the trial period, we had determined a priori to subdivide the treatment indices ‐ since one systematic review suggested that SSRIs begin to have observable beneficial effects in depression during the first week of treatment ‐ as follows (Taylor 2006):

(i) Response ‐ early phase: between one and four weeks, with the time point closest to two weeks given preference. (ii) Response ‐ acute phase: between six and 12 weeks, with preference given to the time point given in the original study as the study endpoint. (iii) Response ‐ follow‐up phase: between four and six months, with the time point closest to 24 weeks given preference.

The acute phase treatment response rates were our primary outcome of interest.

Secondary outcomes

1. Response ‐ early phase, and follow‐up phase

2. Remission ‐ early phase, acute phase, and follow‐up phase

We were interested in the number of patients who achieved remission, (1) showing =< 7 on HRSD‐17, =< 8 on for all the other longer versions of HRSD, and =< 11 on MADRS or (2) who were "not ill or borderline mentally ill" (score 1 or 2) on the CGI‐Severity score out of the total number of randomised patients. Where both were provided, we preferred the former criterion for judging remission.

3. Group mean scores at the end of the trial and change score on depression scale

4. Social adjustment, social functioning, including the Global Assessment of Function (GAF) scores

5. Health‐related quality of life (QOL)

We limited ourselves to SF‐12 (Ware 1998), SF‐36 (Ware 1992), HoNOS (Wing 1998) and the WHO 2009‐QOL (WHOQOL Group 1998).

6. Costs to healthcare services

7. Acceptability

7.1 Total dropout

Number of patients who dropped out during the trial as a proportion of the total number of randomised patients.

7.2 Dropout due to inefficacy

Number of patients who dropped out during the trial because the fluvoxamine was ineffective as a proportion of the total number of randomised patients.

7.3 Dropout due to side effects

Number of patients who dropped out during the trial due to side effects, as a proportion of the total number of randomised patients.

7.4 Number of patients experiencing at least one side effect

7.5 Number of patients experiencing the following specific side effects was sought:

sleepiness/drowsiness

insomnia

dry mouth

constipation

problems urinating

hypotension

agitation/anxiety

suicide wishes/gestures/attempts

completed suicide

vomiting/nausea

diarrhoea

To avoid missing any relatively rare or unexpected side effects in the data extraction phase, we collected all side effect data reported in the literature and discussed ways to summarize them post hoc. Descriptive data regarding side‐effect profiles were extracted from all available studies. Only studies reporting the number of patients experiencing individual side effects were retained. Due to a lack of consistent reporting of side effects, which came primarily from the study authors' descriptions, we combined terms describing similar side effects; for example, we combined "dry mouth", "reduced salivation" and "thirst" into "dry mouth". All side‐effect categories were then grouped by organ system, such as neuropsychiatric, gastrointestinal, respiratory, sensory, genitourinary, dermatological and cardiovascular, in accordance with the advice of a previous study (Mottram 2006).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched The Cochrane Collaboration Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Controlled Trials Register and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CCDANCTR) up to February 2012, MEDLINE (1966 to 2012), EMBASE (1974 to 2012). We also searched trial databases of the following drug‐approving agencies for published, unpublished and ongoing controlled trials: the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the USA, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) in the UK, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in the EU, the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA) in Japan and the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) in Australia. In addition, we searched ongoing trial registers such as clinicaltrials.gov in the USA, International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number Register (ISRCTN) and the National Research Register in the UK, Nederland's Trial Register in the Netherlands, European Union Drug Regulating Authorities Clinical Trials (EudraCT) in the EU, UMIN‐CTR in Japan, the Australian Clinical Trials Registry in Australia and the clinical trial register of Lundbeck and Forest (citalopram manufacturer): http://www.lundbecktrials.com/ and http://www.forestclinicaltrials.com/CTR/CTRController/CTRHome, respectively These searches were undertaken in November 2010 and replicated in February 2012. No language restriction was applied.

CCDANCTR‐Studies were searched using the following search strategy: Diagnosis = Depress* or Dysthymi* or "Adjustment Disorder*" or "Mood Disorder*" or "Affective Disorder" or "Affective Symptoms" and Intervention = Citalopram

CCDANCTR‐References were searched using the following search strategy: Keyword = Depress* or Dysthymi* or "Adjustment Disorder*" or "Mood Disorder*" or "Affective Disorder" or "Affective Symptoms" and Free‐Text = Citalopram

Searching other resources

1. Handsearches Appropriate journals and conference proceedings relating to citalopram treatment for depression have already been handsearched and incorporated into the CCDANCTR databases.

2. Personal communication

We asked pharmaceutical companies and experts in this field if they knew of any study that met the inclusion criteria of this review.

3. Reference checking

We checked reference lists of the included studies, previous systematic reviews and major textbooks of affective disorder written in English for published reports and citations of unpublished research (Trespidi 2011).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently checked to ensure that studies relating to duloxetine generated by the search strategies of the CCDANCTR‐References and the other complementary searches met the rough inclusion criteria, firstly based on the title and abstracts. All of the studies that were rated as possible candidates by either of the two review authors were added to the preliminary list, and their full texts were retrieved. Review authors AC, GI, MP, AS and CT then assessed all of the full text articles in this preliminary list to see if they met the strict inclusion criteria. If the raters disagreed, the final rating was made by consensus with the involvement ‐ if necessary ‐ of another member of the review group (CB, NW or TAF). Considerable care was taken to exclude duplicate publications.

Data extraction and management

AC, GI, MP, AS and CT extracted data from the included studies. Again, any disagreement was discussed, and decisions were documented. If necessary, we contacted authors of studies for clarification. We extracted the following data:

(i) participant characteristics (age, sex, depression diagnosis, comorbidity, depression severity, antidepressant treatment history for the index episode, study setting); (ii) intervention details (intended dosage range, mean daily dosage actually prescribed, co‐intervention if any, duloxetine as investigational drug or as comparator drug, sponsorship); (iii) outcome measures of interest from the included studies.

The results were compared with those in the completed reviews of individual antidepressants in The Cochrane Library. If the trial was a three (or more)‐armed trial involving a placebo arm, the data were extracted from the placebo arm as well.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed trial quality in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). This set of criteria is based on evidence of associations between effect overestimation and a high risk of bias in an article, such as sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data and selective reporting. The categories are defined as:

low risk of bias;

high risk of bias;

unclear risk of bias.

If the raters disagreed, the final rating was made by consensus with the involvement (if necessary) of another member of the review group. Non‐congruence in quality assessment was reported as percentage disagreement. The ratings were also compared with those in the completed reviews of individual antidepressants in The Cochrane Library. If there were any discrepancies, these were fed back to the authors of the completed reviews.

Measures of treatment effect

All comparisons were performed between citalopram and comparator ADs as individual ADs. Citalopram was also compared with TCAs and heterocyclics as a class.

1. Dichotomous data

For dichotomous, or event‐like, data, odds ratios (ORs) were calculated with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For statistically significant results, we calculated the number needed to treat to provide benefit (NNTB) and the number needed to treat to induce harm (NNTH) as the inverse of the risk difference.

2. Continuous data

For continuous data, we calculated mean differences (MD), or standardised mean differences (SMD) where different measurement scales were used, with 95% CIs.

Unit of analysis issues

1. Cross‐over trials

A major concern of cross‐over trials is the carry‐over effect. It occurs if an effect (e.g., pharmacological, physiological or psychological) of the treatment in the first phase is carried over to the second phase. As a consequence, on entry to the second phase, the participants can differ systematically from their initial state, despite a wash‐out phase. For the same reason, cross‐over trials are not appropriate if the condition of interest is unstable (Elbourne 2002). As both effects are very likely in major depression, we only used data from the first phase of the cross‐over studies.

2. Cluster‐randomised trials

No cluster‐randomised trials were identified for this version of the review. Should they be identified in a future update, we plan to use the generic inverse variance technique, if such trials have been appropriately analysed taking into account intraclass correlation coefficients to adjust for cluster effects.

3. Multiple intervention groups

Studies that compared more than two intervention groups were included in meta‐analysis by combining all relevant experimental intervention groups of the study into a single group, and all relevant control intervention groups into a single control group, as recommended in section 16.5 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Dealing with missing data

1. Dichotomous data

Responders and remitters to treatment were calculated on the strict intention‐to‐treat (ITT) basis: dropouts were included in this analysis. Where participants had been excluded from the trial before the endpoint, we assumed that they experienced a negative outcome by the end of the trial (e.g., failure to respond to treatment). We examined the validity of this decision in sensitivity analyses by applying worst‐ and best‐case scenarios. We applied the loose ITT analyses for continuous variables, whereby all the patients with at least one post‐baseline measurement were represented by their last observations carried forward (LOCF), with due consideration of the potential bias and uncertainty introduced.

When dichotomous outcomes were not reported but baseline mean, endpoint mean and the standard deviation (SD) of the HRSD (or other depression scale) were provided, we converted continuous outcome data expressed as mean and SD into the number of responding and remitted patients, according to the validated imputation method (Furukawa 2005). We examined the validity of this imputation in the sensitivity analyses. Where SDs were not reported, authors were asked to supply the data. When only the standard error (SE) or t‐statistics or P values were reported, SDs were calculated according to Altman (Altman 1996). In the absence of data from the authors, we substituted SDs by those reported in other studies in the review (Furukawa 2006).

2. Continuous data

When there were missing data and the method of LOCF had been used to do an ITT analysis, then the LOCF data were used. When SDs were missing, we presented data descriptively.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Skewed data and non‐quantitative data were presented descriptively. An outcome whose minimum score is zero could be considered skewed when the mean was smaller than twice the SD. Heterogeneity between studies was investigated by the I2 statistic (Higgins 2003) (an I2 equal to or more than 50% was considered indicative of heterogeneity) and by visual inspection of the forest plots. We performed subgroup analyses to investigate heterogeneity (see Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity).

Assessment of reporting biases

Data from included studies were entered into a funnel plot (trial effect against trial variance) to investigate small‐study effects (Sterne 2000). We used the tests for funnel plot asymmetry only when there were at least 10 studies included in the meta‐analysis, and results were interpreted cautiously, with visual inspection of the funnel plots (Higgins 2011). When evidence of small‐study effects was identified, we investigated possible reasons for funnel plot asymmetry, including publication bias.

Data synthesis

For the primary analysis we used a random‐effects model OR, which had the highest generalisability in our empirical examination of summary effect measures for meta‐analyses (Furukawa 2002a). The robustness of this summary measure was routinely examined by checking the fixed‐effect model OR and the random‐effects model risk ratio (RR). Material differences between the models were reported. A P value of less than 0.05 and a 95% CI were considered statistically significant. Fixed‐effect analyses were performed routinely for the continuous outcomes as well, to investigate the effect of the choice of method on the estimates. Material differences between the models were reported. Skewed data and non‐quantitative data were presented descriptively. An outcome was considered skewed when the mean was smaller than twice the SD. In terms of change score, data were difficult to depict as skewed or not, as the possibility existed for negative values; therefore, we entered all of the results of this outcome into a meta‐analysis.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We performed the following subgroup analyses for the primary outcome where possible, for the following a priori reasons. Results were interpreted with caution, since multiple comparisons could lead to false positive conclusions (Oxman 1992).

1. Citalopram dosing (fixed low dosage, fixed standard dosage, fixed high dosage; flexible low dosage, flexible standard dosage, flexible high dosage) Existing evidence implies that low dosage antidepressants may be associated with better outcomes ‐ both in terms of efficacy and side effects ‐ than standard or high dosage antidepressants (Bollini 1999; Furukawa 2002b). In addition, a fixed versus flexible dosing schedule may affect estimates of treatment effectiveness (Khan 2003). In the case of citalopram, based on the Defined Daily Dosage (DDD) by WHO (WHO 2009a), low dosage is referred to as < 20, standard dosage to >= 20 but < 40, and high dosage to >= 40 mg/day. We categorised studies by intended maximum dosage of citalopram.

2. Comparator dosing (low dosage, standard dosage, and high dosage) It is easy to imagine that people taking a comparator drug are less likely to complete a study if they are taking a high dosage of the comparator drug. We categorised studies by the intended maximum dose of the comparator based on the DDD.

3. Depression severity (severe major depression, moderate/mild major depression) "Severe major depression" was defined by a threshold baseline severity score for entry of 25 or more for HRSD and 31 or more for MADRS (Dozois 2004; Müller 2003).

4. Treatment settings (psychiatric in‐patients, psychiatric outpatients, primary care) Because depressive disorder in primary care has a different profile than that of psychiatric in‐patients or outpatients (Suh 1997), it is possible that results obtained from either of these settings may not be applicable to the other settings (Depression Guideline Panel 1993).

5. Elderly patients (>= 65 years of age), separately from other adult patients Older people may be more vulnerable to side effects associated with antidepressants and decreased dosage is often recommended for them (Depression Guideline Panel 1993).Because the number of a priori planned subgroup analyses now appears excessive in comparison with the identified studies, we will consider reducing the number of subgroup analyses or adjusting the level of significance to account for making multiple comparisons in the next update.

Sensitivity analysis

The following sensitivity analyses for primary outcome were planned a priori. By limiting the included studies to those with higher quality (analyses one to five) or to those free from some "bias" (analyses six to nine), we examined whether the results changed and we intended to check for the robustness of the observed findings.

We excluded trials with unclear concealment of random allocation and/or unclear double blinding.

We excluded trials with a dropout rate greater than 20%.

We performed the worst‐case scenario ITT: that all patients in the experimental group experienced the negative outcome and all those in the comparison group experienced the positive outcome.

We performed the best‐case scenario ITT: that all patients in the experimental group experienced the positive outcome and all those in the comparison group experienced the negative outcome.

We excluded trials for which the response rates had to be calculated based on the imputation method (Furukawa 2005) and for which the SD had to be borrowed from other trials (Furukawa 2006).

We examined a "wish bias" by comparing the trials where citalopram was used as an investigational drug, the drug that was used as a new compound, to the trials where citalopram was used as a comparator, since some evidence suggests that a new antidepressant might perform worse when used as a comparator than when used as an investigational agent (Barbui 2004).

We excluded trials funded by, or with at least one author affiliated with, a pharmaceutical company marketing citalopram. This sensitivity analysis is particularly important in light of the recent repeated findings that funding strongly affects outcomes of research studies (Als‐Nielsen 2003; Bhandari 2004; Lexchin 2003; Montgomery 2004; Perlis 2005; Procyshyn 2004) and because industry sponsorship and authorship of clinical trials have increased over the past 20 years (Buchkowsky 2004).

We excluded studies that included patients with bipolar depression.

We excluded trials that included patients with psychotic features.

Our routine application of random‐effects and fixed‐effect models, as well as our secondary outcomes of remission rates and continuous severity measures, may be considered additional forms of sensitivity analyses.

If the CIs of ORs in the groups did not overlap, potential sources of heterogeneity were investigated.

Results

Description of studies

See:Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of studies awaiting classification.

Results of the search

Initially, we identified 303 references. After reading the abstracts, 265 references were considered relevant for our review and retrieved for more detailed evaluation. The search found 37 additional studies written in Chinese. We commissioned a professional translator for the full translation of these papers. The translation process is still ongoing, so in the present review we considered all Chinese studies as awaiting assessment studies (we will include them in the next update of the review, which is expected to be in a two years time). An additional four studies were considered as awaiting assessment because the papers reported insufficient information to decide about inclusion or exclusion (Ahlfors 1988; Galecki 2004; Moeller 1986; Thomas 2008). We contacted corresponding authors and at the time the review has been submitted we are still waiting for their reply and further information. We identified two ongoing studies. Although the search was thorough, it is still possible that there are still unpublished studies which have not been identified.

Included studies

A total of 37 studies were included in this systematic review. Of these, four trials were unpublished (29060/785; Lu 10‐171, 83‐01; Lu 10‐171,79‐01; SCT‐MD‐02). Attempts to contact authors for additional information were successful in seven cases (with additional data provided by authors) and unsuccessful in 13.

Sample Size

The mean sample size per arm was 107 participants (range 17‐303). Sixteen studies recruited fewer than 100 participants overall.

Study design

The great majority of included studies were reported to be double‐blind (28 out of 37 RCTs, that is 75.6%).

Country

The great majority of included studies had been carried out in Europe or in the US (29 out of 37 RCTs, that is 78.4%). Two studies randomised patients in China (Hsu 2011; Ou 2010), three in India (Khanzode 2003; Lalit 2004; Matreja 2007) and one in Russia (Yevtushenko 2007).

Age

Four studies randomised only elderly patients (Allard 2004; Karlsson 2000; Kyle 1998; Navarro 2001) and 22 studies only patients aged between 18 and 65 years (59.4%). The remaining studies randomised both adult and elderly patients or it was unclear.

Diagnosis

Only three studies (8.1%) included patients with bipolar disorder (Bougerol 1997a; Hosak 1999; Timmerman 1993). As per protocol, RCTs were included in the present review only if patients with bipolar disorder were less than 20% in each study.

Setting/participants

Twenty trials enrolled only out‐patients, four studies only in‐patients (Andersen 1986; de Wilde 1985; Hosak 1999; Lu 10‐171,79‐01), seven recruited both in‐ and out‐patients (Bougerol 1997a; Gravem 1987; Karlsson 2000; Lu 10‐171, 83‐01; Navarro 2001; Ou 2010; Shaw 1986), three studies enrolled patients from general practice (Bougerol 1997b; Ekselius 1997; Lewis 2011). In the remaining three studies the setting was unclear. About two thirds of the participants were women. In 31 RCTs patients had a formal diagnosis of major depression (or major depressive disorder) according to DSM‐III, DSM‐III‐R, DSM‐IV or ICD‐10 criteria. In six studies the diagnosis was based on different standardized research criteria (i.e., Feighner criteria).

Interventions and comparators

We found RCTs comparing citalopram with TCAs (amitriptyline, imipramine and nortriptyline), tetracycles (mianserin and maprotiline), other SSRIs (escitalopram, fluoxetine, sertraline, fluvoxamine and paroxetine), one SNRI (namely, venlafaxine), one MAOI (moclobemide), other conventional ADs (mirtazapine and reboxetine) and also only one non‐conventional ADs (St John's wort, or hypericum). Hypericum, a member of the Hypericaceae family, has been used in folk medicine for a long time for a range of indications including depressive disorders. It is licensed and widely used in Germany for the treatment of depressive, anxiety and sleep disorders and in recent years it has also become increasingly popular in other European and non‐European countries (Linde 2008).

Details on the included studies are as follows: nine studies (overall 1277 participants) comparing citalopram with TCAs (four studies versus amitriptyline, two versus imipramine and two studies versus nortriptyline and one study versus clomipramine, respectively); three studies (overall 477 participants) comparing citalopram with tetracyclics (two studies versus mianserin and one study versus maprotiline); 18 studies (overall 4200 participants) comparing citalopram with SSRIs (seven studies versus escitalopram, four studies versus fluoxetine), four studies versus sertraline, one study versus fluvoxamine, one study versus paroxetine and one study versus either escitalopram or sertraline); six studies (overall 1137 participants) comparing citalopram with SNRIs (one study versus each of the following drugs: venlafaxine and mirtazapine), comparing citalopram with MAOI (one study versus moclobemide), comparing citalopram with other conventional psychotropic drugs (two studies versus reboxetine), comparing citalopram with non‐conventional antidepressants (one study versus hypericum).

There were four three‐arm trials: one study comparing citalopram (20 mg/day) with escitalopram 20 mg/day or escitalopram 10 mg/day; one study comparing citalopram (20‐60 mg/day) with amitriptyline (150‐300 mg/day) or fluoxetine (20‐60 mg/day); one study comparing citalopram 10‐30 mg/day with citalopram 20‐60 mg/day or imipramine (50‐150 mg/day); one study compared citalopram (20 mg/day) with escitalopram 10 mg/day or citalopram 10 mg/day. One four‐arm trial compared citalopram 20 mg/day with citalopram 40 mg/day or paroxetine controlled‐release 12.5 mg/day or paroxetine controlled‐release 25 mg/day.

Outcomes

Of the included 37 studies, one study (Andersen 1986) did not report efficacy data and one study reported split data according to different genotypes (Lewis 2011). We were not able to obtain further data for these trials because we could not contact the authors by any means and therefore, could not obtain extra information from these authors. By contrast, all 37 studies did report tolerability/acceptability data that could be entered into a meta‐analysis The great majority of the identified studies (34 out of 37 RCTs) used the MADRS or HRSD as the rating scale of choice for primary or secondary outcome measures. Among the 35 studies reporting dropouts due to any reason, 31 reported dropouts due to side effects. Twenty‐eight studies reported the number of patients experiencing individual side effects.

Excluded studies

Of the 265 references retrieved for more detailed evaluation, 214 articles did not meet our inclusion criteria and were excluded because of one of the following reasons: duplicate publications (eight articles), wrong diagnosis (24 articles), wrong population (51 articles), wrong comparison or intervention (63 articles) and non‐randomised or wrong design (68 articles). Fourteen additional studies were considered as awaiting assessment (overall we found 51 awaiting assessment studies ‐ see above).

Risk of bias in included studies

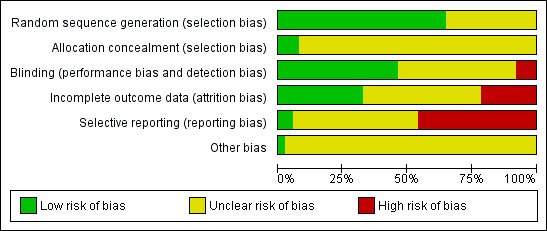

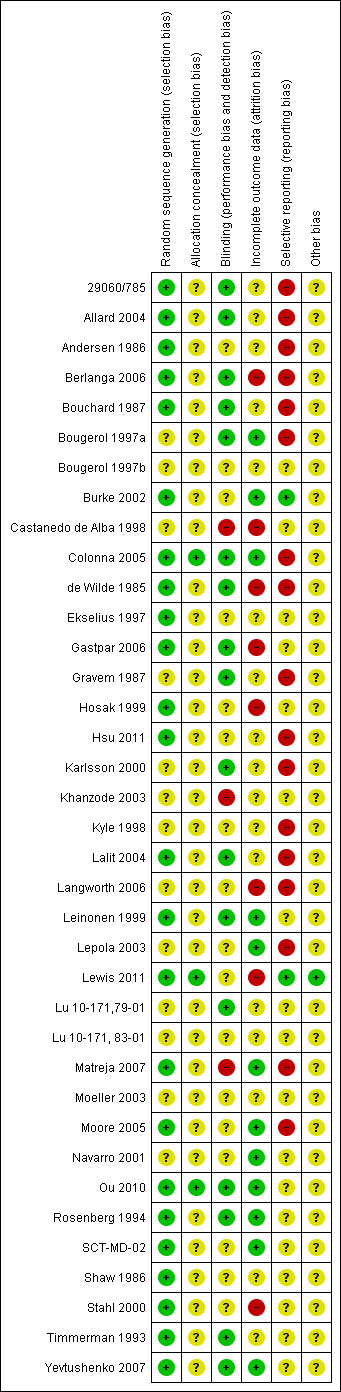

See: Included studies, Figure 1, Figure 2.

1.

Methodological quality graph: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

2.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Our judgment about the overall risk of bias in the individual studies is illustrated in Figure 1 and Figure 2. The methodological quality of these included studies was judged as poor, although judging articles from some time ago by today’s standard might be problematic (Begg 1996). Nevertheless, the reporting in these studies overall was not good. This type of reporting has been associated with an overestimate of the estimate of effect (Schulz 1995) and this should be considered when interpreting the results.

Allocation

The majority of studies reported the methods of generating random sequence, in which “a computer originated schedule” was used, however, only three studies reported enough details on allocation concealment (Colonna 2005; Lewis 2011; Ou 2010). We were not assured that bias was minimised during the allocation procedure in the other studies, yet the great majority of them reported that the participants allocated to each treatment group were “similar”, “the same”, “not significantly different”, “comparable” or “matched”.

Blinding

Thirty out of 37 RCTs (81.1%) described their design as “double‐blind”; however, no tests were conducted to ensure successful blinding. In the review we have included one “single‐blind” trial (Navarro 2001) which was rated as having a “high risk of bias” because it was unclear whether its outcome assessment was blinded to the medication. Four trials were open trials that did not seek blinding (Castanedo de Alba 1998; Hosak 1999; Lewis 2011; Matreja 2007) and in two studies the blinding was unclear (Moeller 2003; Ou 2010).

Incomplete outcome data

Total dropout rate was overall relatively high, ranging from 2% (Matreja 2007) to 56% (Stahl 2000). There were 23 studies (62.2%) where the total dropout rates were more than 20%.

Selective reporting

The study protocol was not available for almost all studies. Only six studies reported SDs of change scores (Burke 2002; Langworth 2006; Lepola 2003; Ou 2010; SCT‐MD‐02; Yevtushenko 2007); 10 studies (Allard 2004; Bouchard 1987; de Wilde 1985; Bougerol 1997a; Bougerol 1997b; Khanzode 2003; Lu 10‐171, 83‐01; Lu 10‐171,79‐01; Shaw 1986; Timmerman 1993) reported SDs of endpoint score of continuous efficacy variables.

Other potential sources of bias

Most of the included studies were funded by industry and only one study was clearly not funded by industry sponsor (Castanedo de Alba 1998). Among the trials comparing citalopram to TCAs or heterocyclics, the great majority (nine out of 11) were sponsored by, or had at least one author affiliated with, the pharmaceutical company marketing citalopram. Most of the studies comparing citalopram with other SSRIs (11 out of 16) were sponsored by the citalopram manufacturer, however, all the studies comparing citalopram with escitalopram (seven RCTs) were sponsored by their mutual manufacturer and in these studies citalopram was always considered as the reference drug. Among the six studies comparing citalopram with other ADs or non‐conventional antidepressant agents, only one was sponsored by the citalopram manufacturer (Berlanga 2006).

Effects of interventions

The included studies did not report on all the outcomes that were pre‐specified in the protocol of this review. Outcomes of clear relevance to patients and clinicians, in particular, patient's and their relatives' attitudes to treatment, their ability to return to work and resume normal social functioning, health‐related quality of life measures and costs to healthcare services were not reported in the included studies. Overall, 6147 patients were available for assessing efficacy (3183 participants randomised to citalopram and 3023 to another antidepressant) and 6960 for examining acceptability of treatments (3538 participants allocated to citalopram and 3378 to another antidepressant). Evidence of differences in efficacy, acceptability and tolerability was found and details are listed below. To obtain missing response rates and remission, we used validated imputation methods from continuous outcomes. We imputed SDs for some continuous outcomes of the following studies: Castanedo de Alba 1998; Colonna 2005; Ekselius 1997; Hosak 1999; Leinonen 1999; Moore 2005; Rosenberg 1994; Stahl 2000.

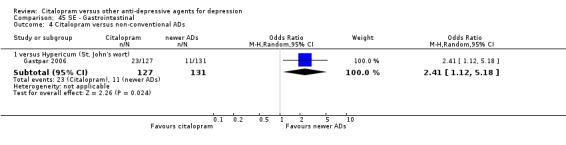

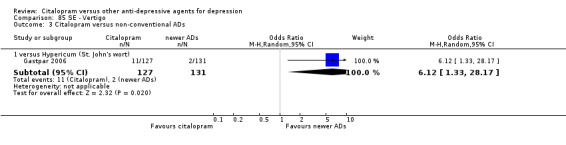

The results of the present systematic review were reported comparison by comparison (grouping them into different drug classes according to review protocol, see Methods section ‐ Types of interventions) and by outcome (following the review protocol ‐ for details see Imperadore 2007). The forest plots were organised according to the relevance of outcomes, as reported in the review protocol. For adverse events, all the retrieved information about the adverse events specified in the review protocol were reported (either statistically or non‐statistically significant). Remaining adverse events were only reported when statistically significant (non‐statistically significant results about adverse events are presented in Table 1).

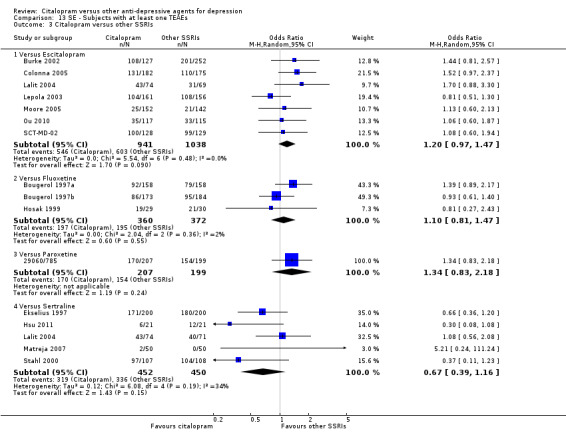

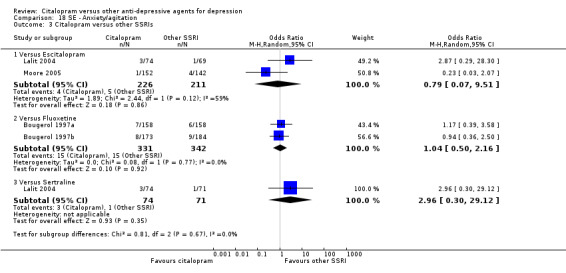

1. Adverse events.

| Adverse event | Study | CItalopram | Comparator | Odds Ratio, Random [95% CI] | ||

| Events | Total | Events | Total | |||

| Citalopram versus TCAs | ||||||

| Citalopram vs amitriptyline | ||||||

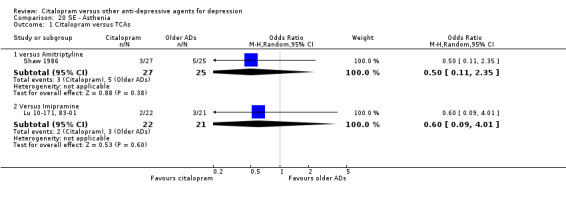

| Asthenia | Shaw 1986 | 3 | 27 | 5 | 25 | 0.50 [0.11, 2.35] |

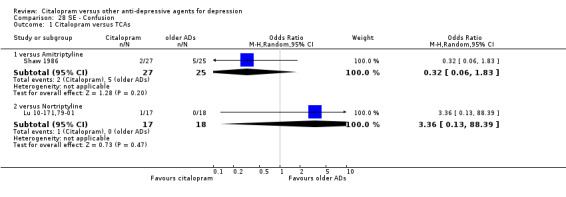

| Confusion | Shaw 1986 | 2 | 27 | 5 | 25 | 0.32 [0.06, 1.83] |

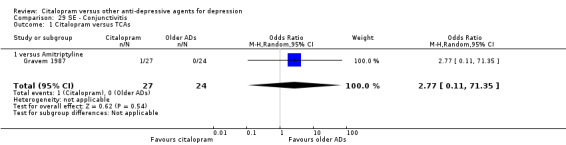

| Conjunctivitis | Gravem 1987 | 1 | 27 | 0 | 24 | 2.77 [0.11, 71.35] |

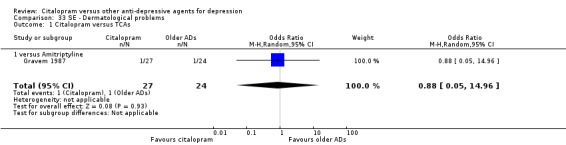

| Dermatological problems | Gravem 1987 | 1 | 27 | 1 | 24 | 0.88 [0.05, 14.96] |

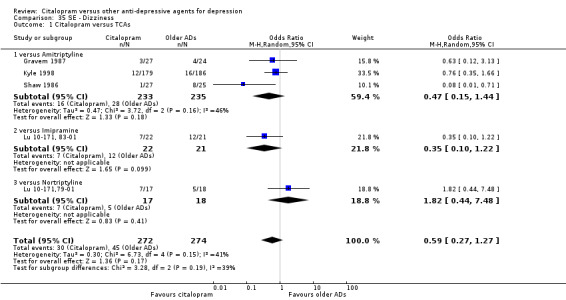

| Dizziness | Gravem 1987; Kyle 1998; Shaw 1986 | 16 | 233 | 28 | 235 | 0.47 [0.15, 1.44] |

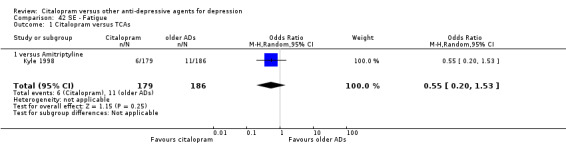

| Fatigue | Kyle 1998 | 6 | 179 | 11 | 186 | 0.55 [0.20, 1.53] |

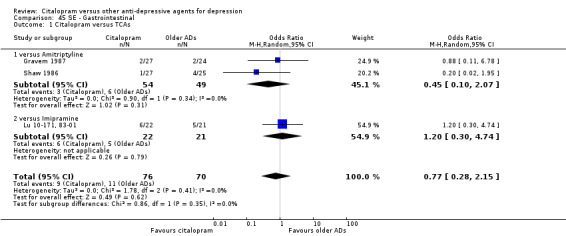

| Gastrointestinal | Gravem 1987; Shaw 1986 | 3 | 54 | 6 | 49 | 0.45 [0.10, 2.07] |

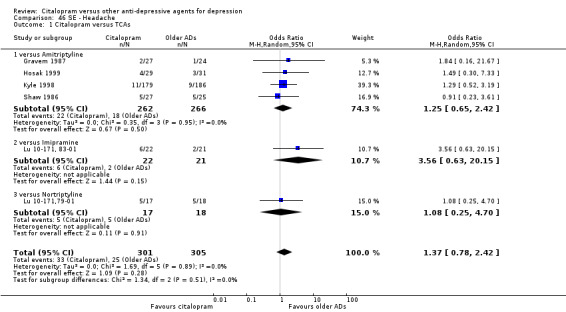

| Headache | Gravem 1987; Hosak 1999; Kyle 1998; Shaw 1986 | 22 | 262 | 18 | 266 | 1.25 [0.65, 2.42] |

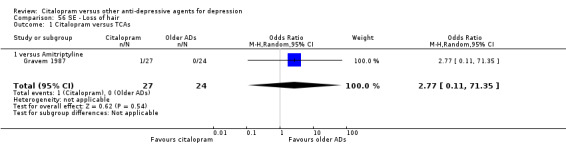

| Loss of hair | Gravem 1987 | 1 | 27 | 0 | 24 | 2.77 [0.11, 71.35] |

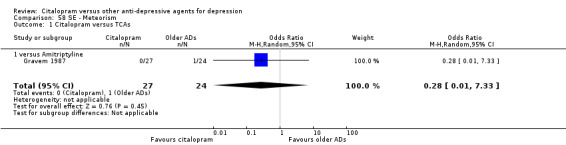

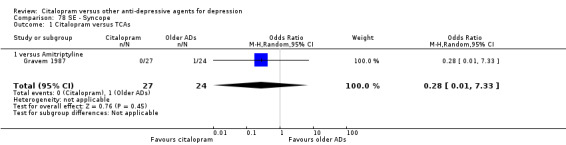

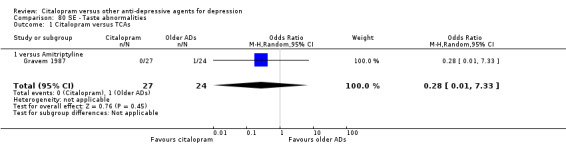

| Meteorism | Gravem 1987 | 0 | 27 | 1 | 24 | 0.28 [0.01, 7.33] |

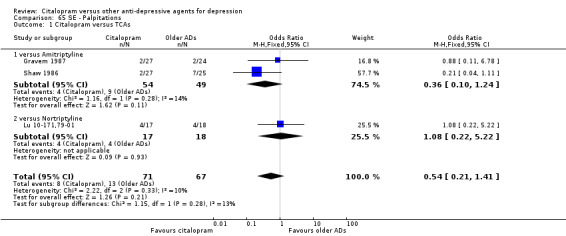

| Palpitations | Gravem 1987; Shaw 1986 | 4 | 54 | 9 | 49 | 0.36 [0.10, 1.24] |

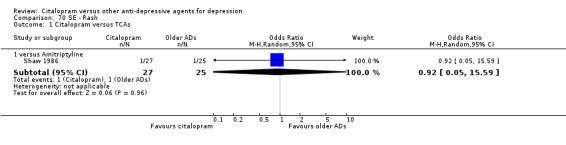

| Rash | Shaw 1986 | 1 | 27 | 1 | 25 | 0.92 [0.05, 15.59] |

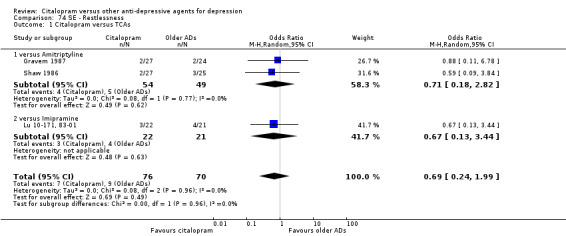

| Restlessness | Gravem 1987; Shaw 1986 | 4 | 54 | 5 | 49 | 0.71 [0.18, 2.82] |

| Sweating | Gravem 1987 | 2 | 27 | 3 | 24 | 0.56 [0.09, 3.67] |

| Syncope | Gravem 1987 | 0 | 27 | 1 | 24 | 0.28 [0.01, 7.33] |

| Taste abnormalities | Gravem 1987 | 0 | 27 | 1 | 24 | 0.28 [0.01, 7.33] |

| Tremor | Gravem 1987 | 1 | 27 | 1 | 24 | 0.88 [0.05, 14.96] |

| Visual problems | Gravem 1987 | 0 | 27 | 3 | 24 | 0.11 [0.01, 2.28] |

| Citalopram vs imipramine | ||||||

| Asthenia | Lu 10‐171, 83‐01 | 2 | 22 | 3 | 21 | 0.60 [0.09, 4.01] |

| Dizziness | Lu 10‐171, 83‐01 | 7 | 22 | 12 | 21 | 0.35 [0.10, 1.22] |

| Gastrointestinal | Lu 10‐171, 83‐01 | 6 | 22 | 5 | 21 | 1.20 [0.30, 4.74] |

| Headache | Lu 10‐171, 83‐01 | 6 | 22 | 2 | 21 | 3.56 [0.63, 20.15] |

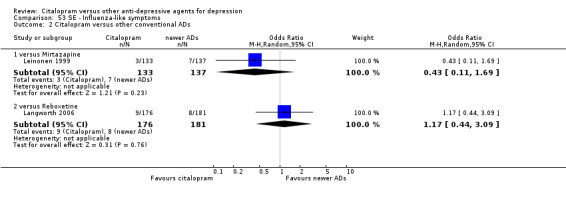

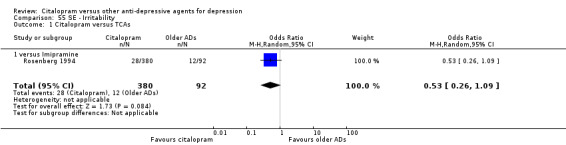

| Irritability | Rosenberg 1994 | 28 | 380 | 12 | 92 | 0.53 [0.26, 1.09] |

| Restlessness | Lu 10‐171, 83‐01 | 3 | 22 | 4 | 21 | 0.67 [0.13, 3.44] |

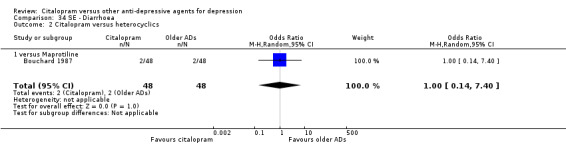

| Citalopram vs maprotiline | ||||||

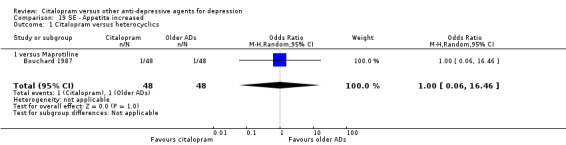

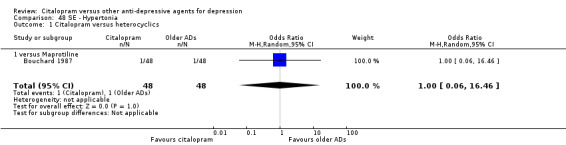

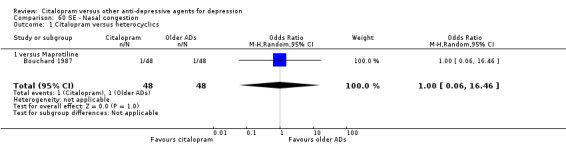

| Appetite increased | Bouchard 1987 | 1 | 48 | 1 | 48 | 1.00 [0.06, 16.46] |

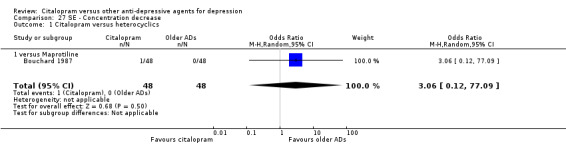

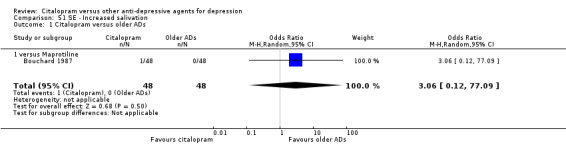

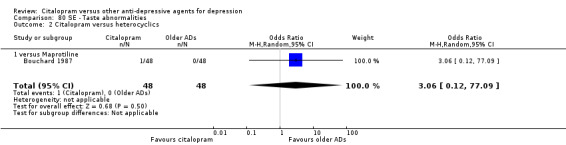

| Concentration decrease | Bouchard 1987 | 1 | 48 | 0 | 48 | 3.06 [0.12, 77.09] |

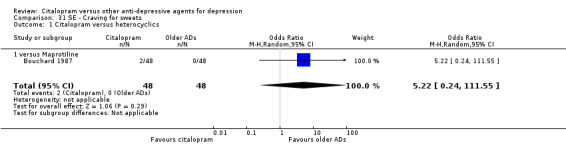

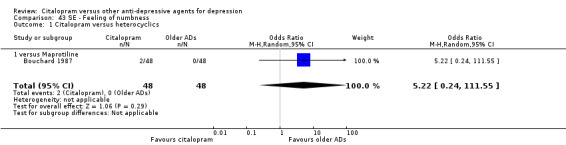

| Craving for sweets | Bouchard 1987 | 2 | 48 | 0 | 48 | 5.22 [0.24, 111.55] |

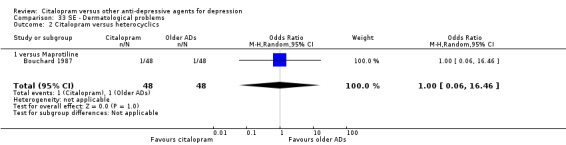

| Dermatological problems | Bouchard 1987 | 1 | 48 | 1 | 48 | 1.00 [0.06, 16.46] |

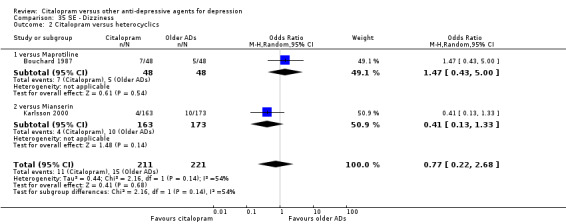

| Dizziness | Bouchard 1987 | 7 | 48 | 5 | 48 | 1.47 [0.43, 5.00] |

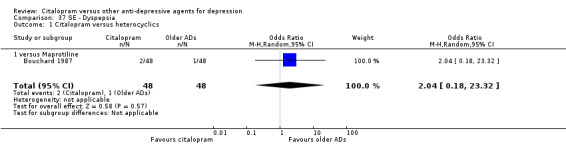

| Dyspepsia | Bouchard 1987 | 2 | 48 | 1 | 48 | 2.04 [0.18, 23.32] |

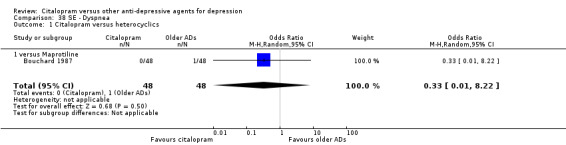

| Dyspnea | Bouchard 1987 | 0 | 48 | 1 | 48 | 0.33 [0.01, 8.22] |

| Feeling of numbness | Bouchard 1987 | 2 | 48 | 0 | 48 | 5.22 [0.24, 111.55] |

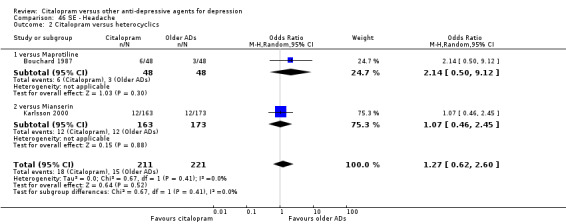

| Headache | Bouchard 1987 | 6 | 48 | 3 | 48 | 2.14 [0.50, 9.12] |

| Hypertonia | Bouchard 1987 | 1 | 48 | 1 | 48 | 1.00 [0.06, 16.46] |

| Increased salivation | Bouchard 1987 | 1 | 48 | 0 | 48 | 3.06 [0.12, 77.09] |

| Nasal congestion | Bouchard 1987 | 1 | 48 | 1 | 48 | 1.00 [0.06, 16.46] |

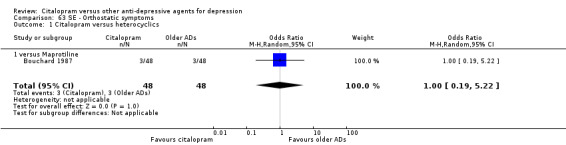

| Orthostatic symptoms | Bouchard 1987 | 3 | 48 | 3 | 48 | 1.00 [0.19, 5.22] |

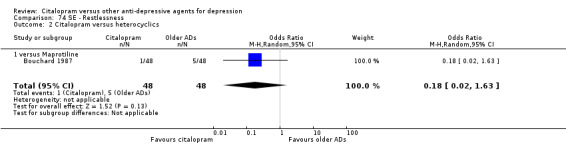

| Restlessness | Bouchard 1987 | 1 | 48 | 5 | 48 | 0.18 [0.02, 1.63] |

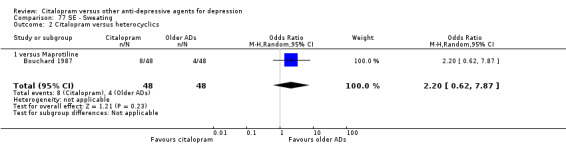

| Sweating | Bouchard 1987 | 8 | 48 | 4 | 48 | 2.20 [0.62, 7.87] |

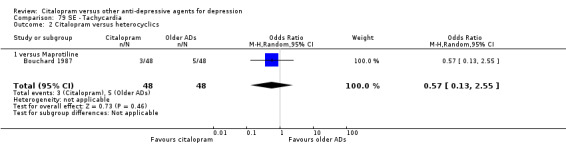

| Tachycardia | Bouchard 1987 | 3 | 48 | 5 | 48 | 0.57 [0.13, 2.55] |

| Taste abnormalities | Bouchard 1987 | 1 | 48 | 0 | 48 | 3.06 [0.12, 77.09] |

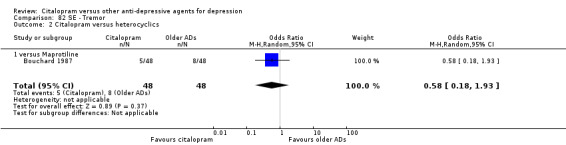

| Tremor | Bouchard 1987 | 5 | 48 | 8 | 48 | 0.58 [0.18, 1.93] |

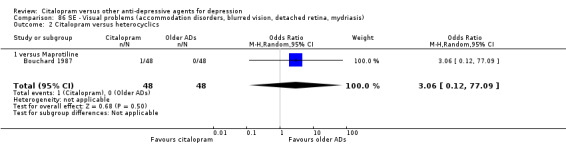

| Visual problems | Bouchard 1987 | 1 | 48 | 0 | 48 | 3.06 [0.12, 77.09] |

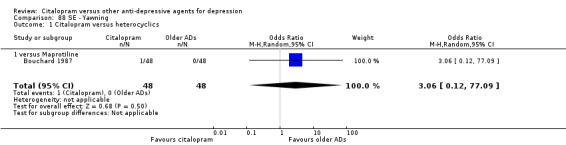

| Yawning | Bouchard 1987 | 1 | 48 | 0 | 48 | 3.06 [0.12, 77.09] |

| Citalopram vs nortriptyline | ||||||

| Confusion | Lu 10‐171,79‐01 | 1 | 17 | 0 | 18 | 3.36 [0.13, 88.39] |

| Headache | Lu 10‐171,79‐01 | 5 | 17 | 5 | 18 | 1.08 [0.25, 4.70] |

| Palpitations | Lu 10‐171,79‐01 | 4 | 17 | 4 | 18 | 1.08 [0.22, 5.22] |

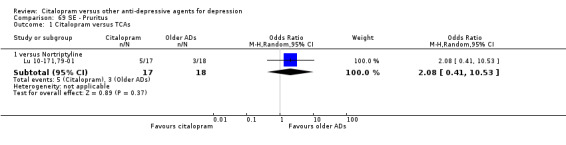

| Pruritus | Lu 10‐171,79‐01 | 5 | 17 | 3 | 18 | 2.08 [0.41, 10.53] |

| Citalopram versus heterocyclics | ||||||

| Citalopram vs mianserin | ||||||

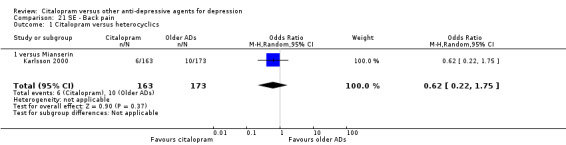

| Back pain | Karlsson 2000 | 6 | 163 | 10 | 173 | 0.62 [0.22, 1.75] |

| Dizziness | Karlsson 2000 | 4 | 163 | 10 | 173 | 0.41 [0.13, 1.33] |

| Headache | Karlsson 2000 | 12 | 163 | 12 | 173 | 1.07 [0.46, 2.45] |

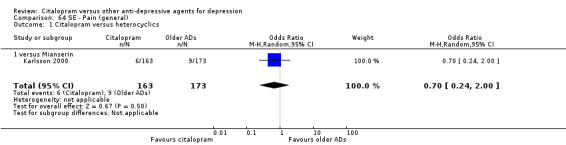

| Pain (general) | Karlsson 2000 | 6 | 163 | 9 | 173 | 0.70 [0.24, 2.00] |

| Citalopram versus other SSRIs | ||||||

| Citalopram vs escitalopram | ||||||

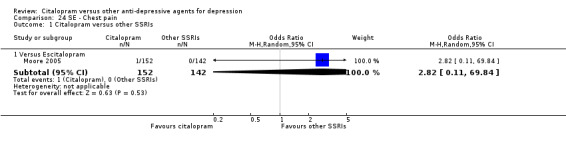

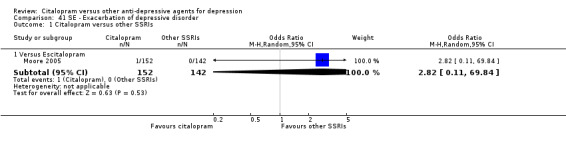

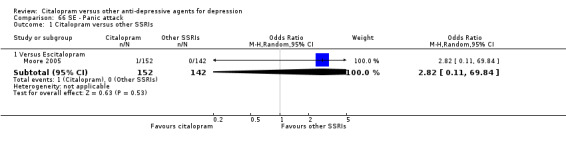

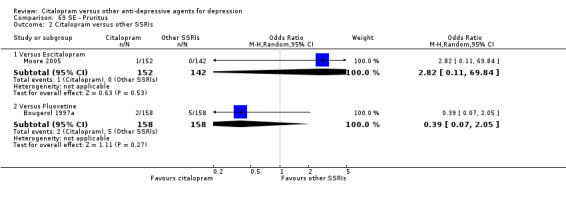

| Abdominal pain | Moore 2005 | 1 | 152 | 0 | 142 | 2.82 [0.11, 69.84] |

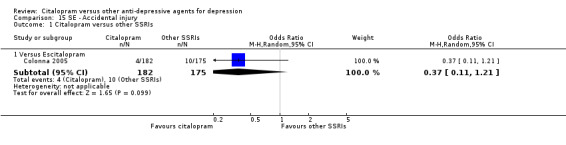

| Accidental injury | Colonna 2005 | 4 | 182 | 10 | 175 | 0.37 [0.11, 1.21] |

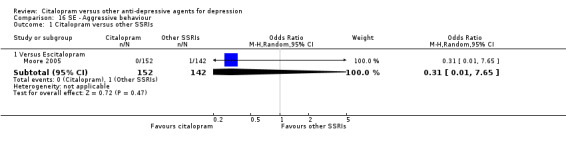

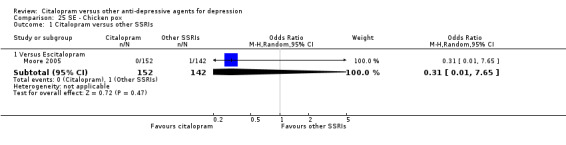

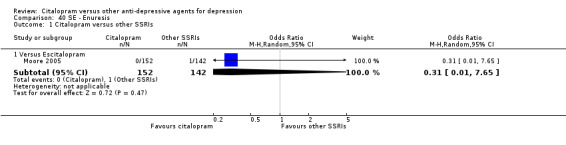

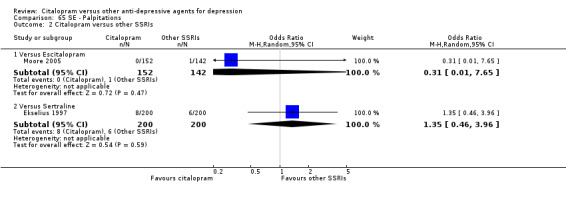

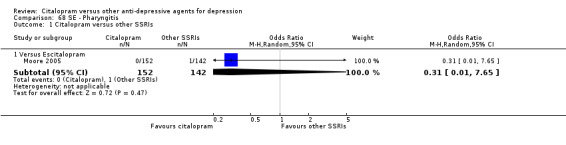

| Aggressive behaviour | Moore 2005 | 0 | 152 | 1 | 142 | 0.31 [0.01, 7.65] |

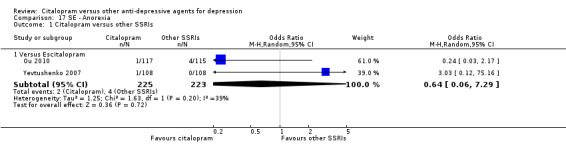

| Anorexia | Ou 2010; Yevtushenko 2007 | 2 | 225 | 4 | 223 | 0.64 [0.06, 7.29] |

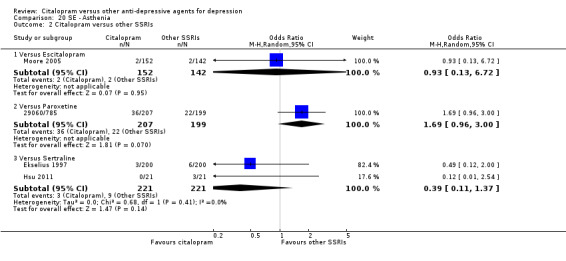

| Asthenia | Moore 2005 | 2 | 152 | 2 | 142 | 0.93 [0.13, 6.72] |

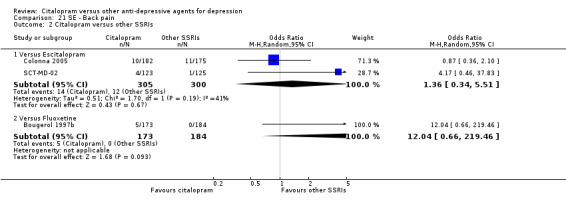

| Back pain | Colonna 2005; SCT‐MD‐02 | 14 | 305 | 12 | 300 | 1.36 [0.34, 5.51] |

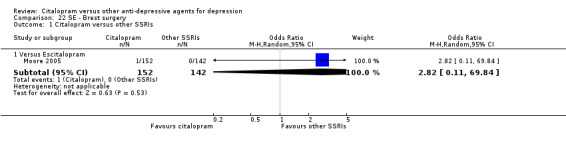

| Breast surgery | Moore 2005 | 1 | 152 | 0 | 142 | 2.82 [0.11, 69.84] |

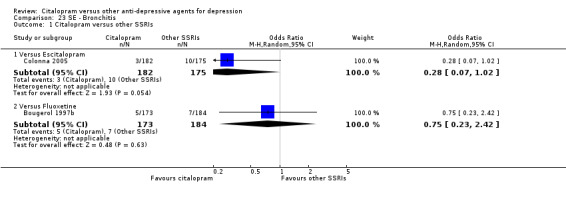

| Bronchitis | Colonna 2005 | 3 | 182 | 10 | 175 | 0.28 [0.07, 1.02] |

| Chest pain | Moore 2005 | 1 | 152 | 0 | 142 | 2.82 [0.11, 69.84] |

| Chicken pox | Moore 2005 | 0 | 152 | 1 | 142 | 0.31 [0.01, 7.65] |

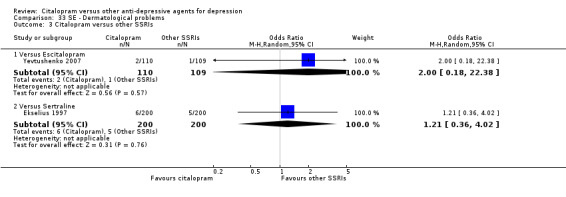

| Dermatological problems | Yevtushenko 2007 | 2 | 110 | 1 | 109 | 2.00 [0.18, 22.38] |

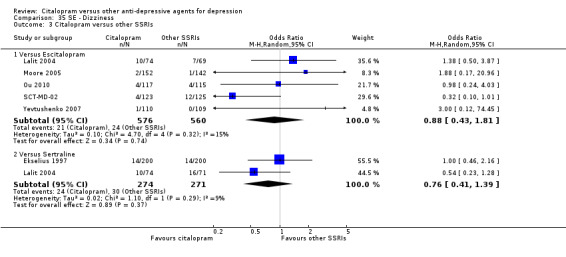

| Dizziness | Moore 2005; Ou 2010; SCT‐MD‐02; Yevtushenko 2007 | 11 | 502 | 17 | 491 | 0.69 [0.28, 1.71] |

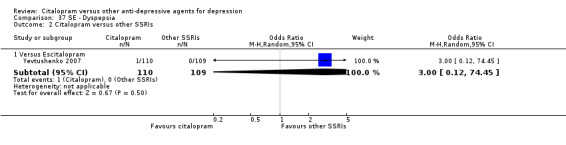

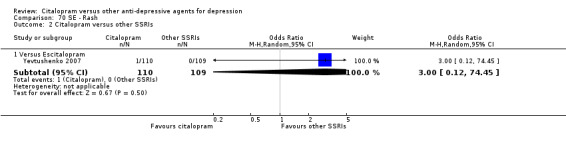

| Dyspepsia | Yevtushenko 2007 | 1 | 110 | 0 | 109 | 3.00 [0.12, 74.45] |

| Enuresis | Moore 2005 | 0 | 152 | 1 | 142 | 0.31 [0.01, 7.65] |

| Exacerbation of depression | Moore 2005 | 1 | 152 | 0 | 142 | 2.82 [0.11, 69.84] |

| Gastrointestinal | Ou 2010 | 14 | 117 | 16 | 115 | 0.84 [0.39, 1.81] |

| Headache | Colonna 2005; Moore 2005; SCT‐MD‐02; Yevtushenko 2007 | 45 | 567 | 46 | 551 | 0.96 [0.49, 1.88] |

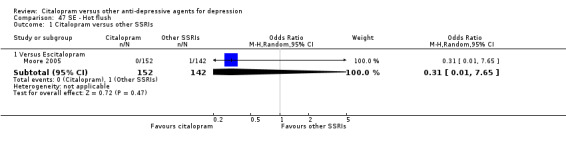

| Hot flash | Moore 2005 | 0 | 152 | 1 | 142 | 0.31 [0.01, 7.65] |

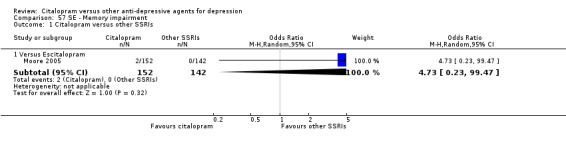

| Memory impairment | Moore 2005 | 2 | 152 | 0 | 142 | 4.73 [0.23, 99.47] |

| Palpitations | Moore 2005 | 0 | 152 | 1 | 142 | 0.31 [0.01, 7.65] |

| Panic attack | Moore 2005 | 1 | 152 | 0 | 142 | 2.82 [0.11, 69.84] |

| Pharyngitis | Moore 2005 | 0 | 152 | 1 | 142 | 0.31 [0.01, 7.65] |

| Pruritus | Moore 2005 | 1 | 152 | 0 | 142 | 2.82 [0.11, 69.84] |

| Rash | Yevtushenko 2007 | 1 | 110 | 0 | 109 | 3.00 [0.12, 74.45] |

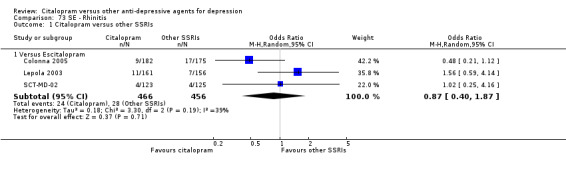

| Rhinitis | Colonna 2005; Lepola 2003; SCT‐MD‐02 | 24 | 466 | 28 | 456 | 0.87 [0.40, 1.87] |

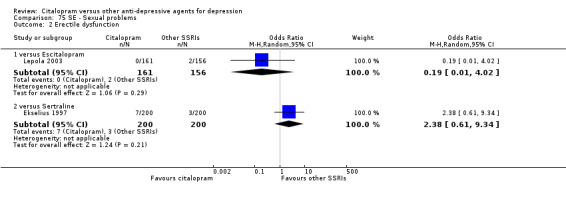

| Sexual problems: erectile dysfunction | Lepola 2003 | 0 | 161 | 2 | 156 | 0.19 [0.01, 4.02] |

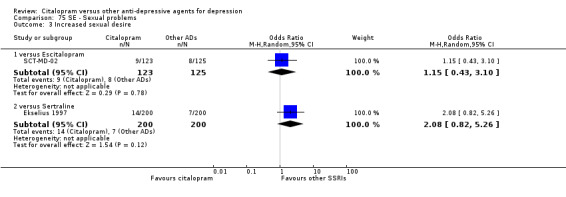

| Sexual problems: increased sexual desire | SCT‐MD‐02 | 9 | 123 | 8 | 125 | 1.15 [0.43, 3.10] |

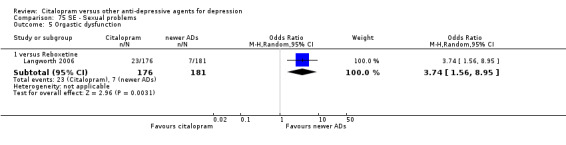

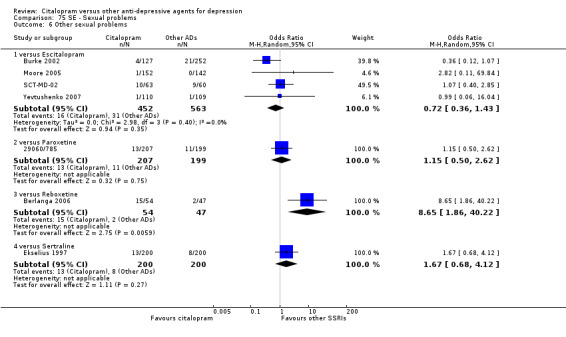

| Sexual problems: other | Burke 2002; Moore 2005; SCT‐MD‐02; Yevtushenko 2007 | 16 | 452 | 31 | 563 | 0.72 [0.36, 1.43] |

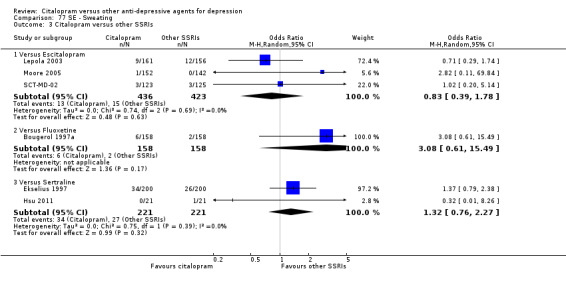

| Sweating | Lepola 2003; Moore 2005; SCT‐MD‐02 | 13 | 436 | 15 | 423 | 0.83 [0.39, 1.78] |

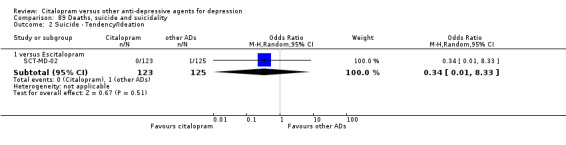

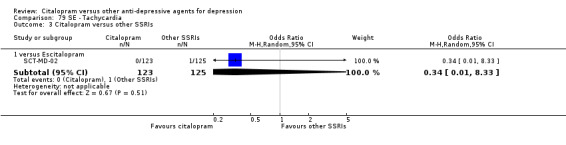

| Tachycardia | SCT‐MD‐02 | 0 | 123 | 1 | 125 | 0.34 [0.01, 8.33] |

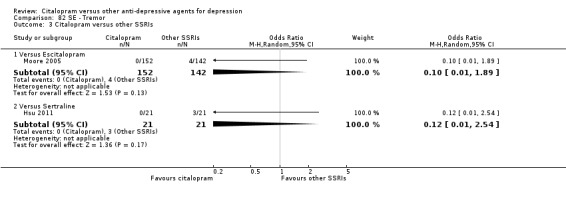

| Tremor | Moore 2005 | 0 | 152 | 4 | 142 | 0.10 [0.01, 1.89] |

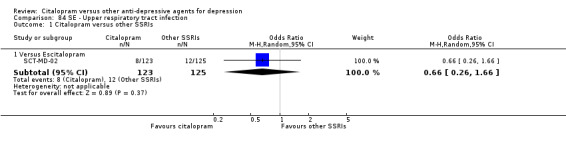

| Upper respiratory tract infection | SCT‐MD‐02 | 8 | 123 | 12 | 125 | 0.66 [0.26, 1.66] |

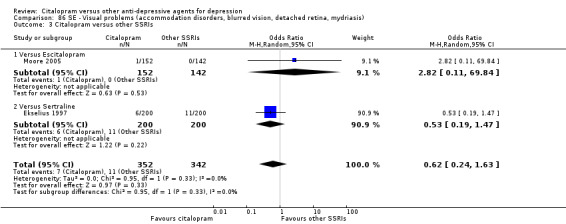

| Visual problems | Moore 2005 | 1 | 152 | 0 | 142 | 2.82 [0.11, 69.84] |

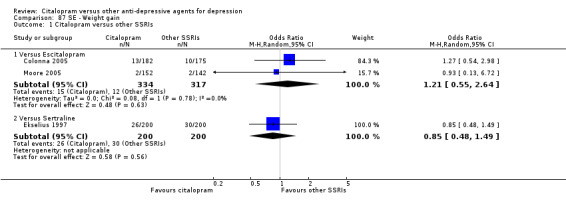

| Weight gain | Colonna 2005; Moore 2005 | 15 | 334 | 12 | 317 | 1.21 [0.55, 2.64] |

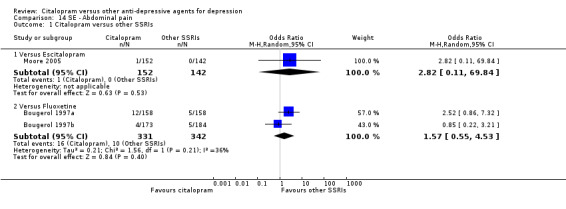

| Citalopram vs fluoxetine | ||||||

| Abdominal pain | Bougerol 1997a; Bougerol 1997b | 16 | 331 | 10 | 342 | 1.57 [0.55, 4.53] |

| Back pain | Bougerol 1997b | 5 | 173 | 0 | 184 | 12.04 [0.66, 219.46] |

| Bronchitis | Bougerol 1997b | 5 | 173 | 7 | 184 | 0.75 [0.23, 2.42] |

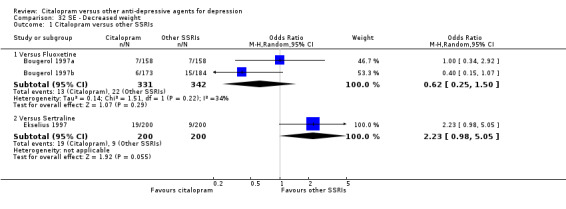

| Decreased weight | Bougerol 1997a; Bougerol 1997b | 13 | 331 | 22 | 342 | 0.62 [0.25, 1.50] |

| Headache | Bougerol 1997a; Bougerol 1997b; Hosak 1999 | 25 | 360 | 28 | 372 | 0.90 [0.51, 1.60] |

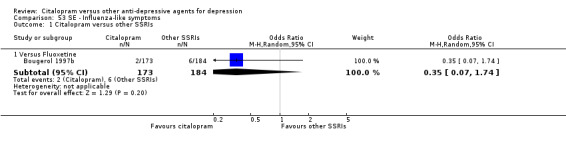

| Influenza‐like symptoms | Bougerol 1997b | 2 | 173 | 6 | 184 | 0.35 [0.07, 1.74] |

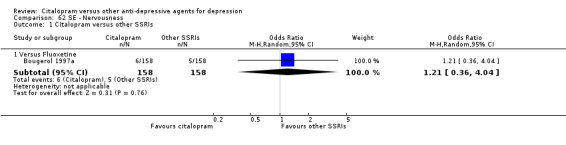

| Nervousness | Bougerol 1997a | 6 | 158 | 5 | 158 | 1.21 [0.36, 4.04] |

| Pruritus | Bougerol 1997a | 2 | 158 | 5 | 158 | 0.39 [0.07, 2.05] |

| Sweating | Bougerol 1997a | 6 | 158 | 2 | 158 | 3.08 [0.61, 15.49] |

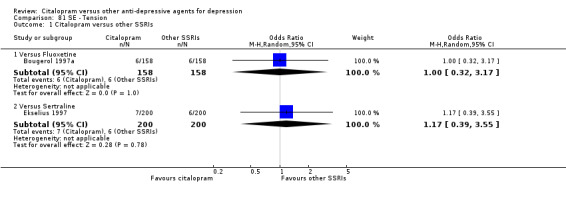

| Tension | Bougerol 1997a | 6 | 158 | 6 | 158 | 1.00 [0.32, 3.17] |

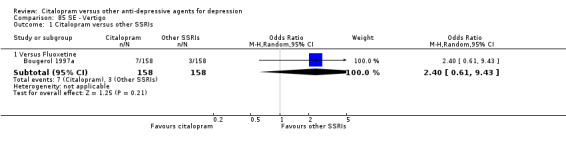

| Vertigo | Bougerol 1997a | 7 | 158 | 3 | 158 | 2.40 [0.61, 9.43] |

| Citalopram vs paroxetine | ||||||

| Asthenia | 29060/785 | 36 | 207 | 22 | 199 | 1.69 [0.96, 3.00] |

| Headache | 29060/785 | 54 | 207 | 44 | 199 | 1.24 [0.79, 1.96] |

| Sexual problems: other | 29060/785 | 13 | 207 | 11 | 199 | 1.15 [0.50, 2.62] |

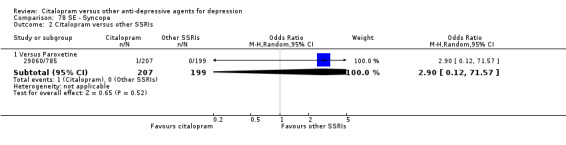

| Syncope | 29060/785 | 1 | 207 | 0 | 199 | 2.90 [0.12, 71.57] |

| Citalopram vs sertraline | ||||||

| Asthenia | Ekselius 1997 | 3 | 200 | 6 | 200 | 0.49 [0.12, 2.00] |

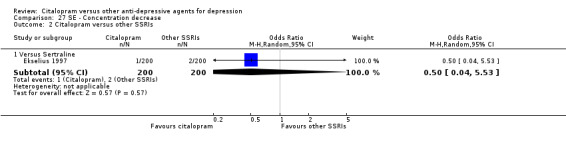

| Concentration decrease | Ekselius 1997 | 1 | 200 | 2 | 200 | 0.50 [0.04, 5.53] |

| Decreased weight | Ekselius 1997 | 19 | 200 | 9 | 200 | 2.23 [0.98, 5.05] |

| Dermatological problems | Ekselius 1997 | 6 | 200 | 5 | 200 | 1.21 [0.36, 4.02] |

| Dizziness | Ekselius 1997 | 14 | 200 | 14 | 200 | 1.00 [0.46, 2.16] |

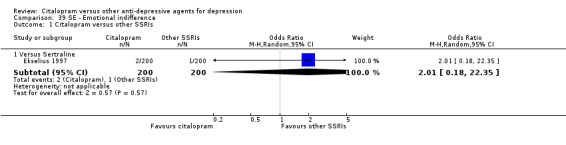

| Emotional indifference | Ekselius 1997 | 2 | 200 | 1 | 200 | 2.01 [0.18, 22.35] |

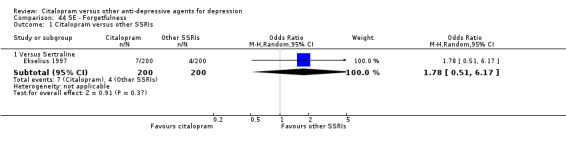

| Forgetfulness | Ekselius 1997 | 7 | 200 | 4 | 200 | 1.78 [0.51, 6.17] |

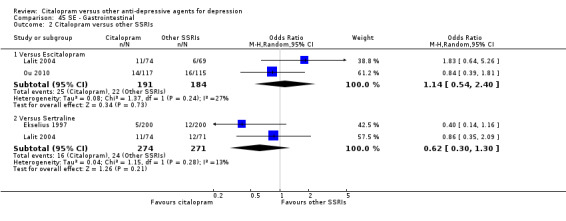

| Gastrointestinal | Ekselius 1997 | 5 | 200 | 12 | 200 | 0.40 [0.14, 1.16] |

| Headache | Ekselius 1997 | 13 | 200 | 18 | 200 | 0.70 [0.33, 1.48] |

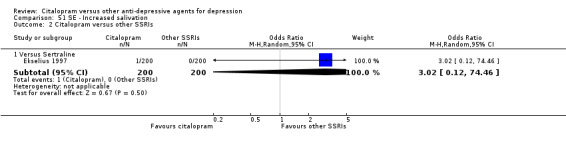

| Increased salivation | Ekselius 1997 | 1 | 200 | 0 | 200 | 3.02 [0.12, 74.46] |

| Palpitations | Ekselius 1997 | 8 | 200 | 6 | 200 | 1.35 [0.46, 3.96] |

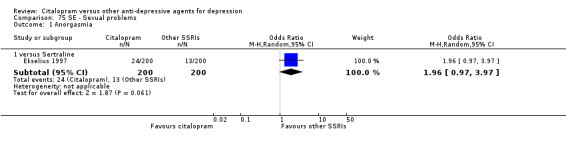

| Sexual problems: anorgasmia | Ekselius 1997 | 24 | 200 | 13 | 200 | 1.96 [0.97, 3.97] |

| Sexual problems: erectile dysfunction | Ekselius 1997 | 7 | 200 | 3 | 200 | 2.38 [0.61, 9.34] |

| Sexual problems: increased sexual desire | Ekselius 1997 | 14 | 200 | 7 | 200 | 2.08 [0.82, 5.26] |

| Sexual problems: loss of sexual interest | Ekselius 1997 | 16 | 200 | 19 | 200 | 0.83 [0.41, 1.66] |

| Sexual problems: other | Ekselius 1997 | 13 | 200 | 8 | 200 | 1.67 [0.68, 4.12] |

| Sweating | Ekselius 1997 | 34 | 200 | 26 | 200 | 1.37 [0.79, 2.38] |

| Tension | Ekselius 1997 | 7 | 200 | 6 | 200 | 1.17 [0.39, 3.55] |

| Visual problems | Ekselius 1997 | 6 | 200 | 11 | 200 | 0.53 [0.19, 1.47] |

| Weight gain | Ekselius 1997 | 26 | 200 | 30 | 200 | 0.85 [0.48, 1.49] |

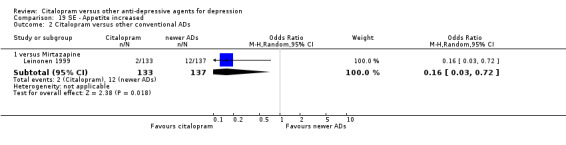

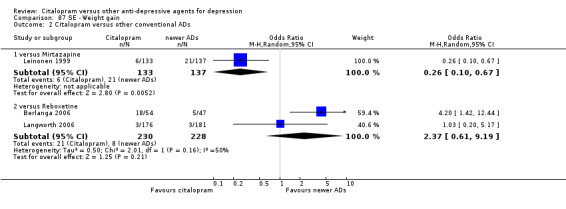

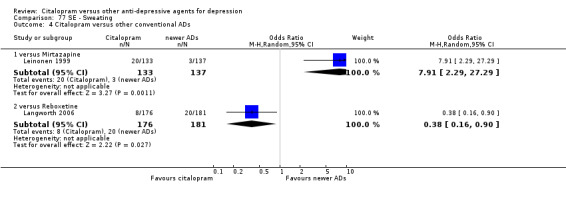

| Citalopram versus other antidepressants | ||||||

| Citalopram vs mirtazapine | ||||||

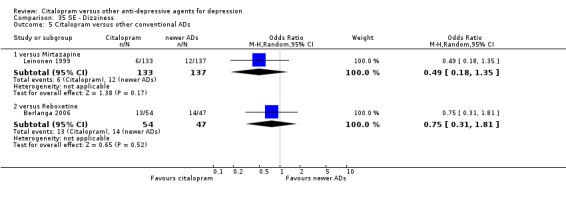

| Dizziness | Leinonen 1999 | 6 | 133 | 12 | 137 | 0.49 [0.18, 1.35] |

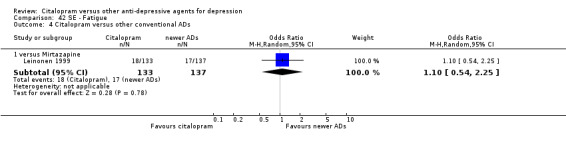

| Fatigue | Leinonen 1999 | 18 | 133 | 17 | 137 | 1.10 [0.54, 2.25] |

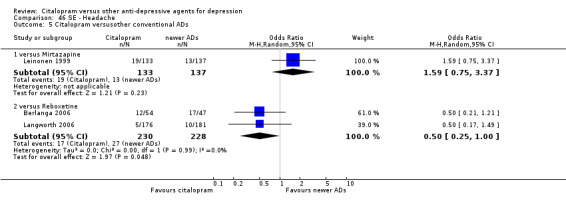

| Headache | Leinonen 1999 | 19 | 133 | 13 | 137 | 1.59 [0.75, 3.37] |

| Influenza‐like symptoms | Leinonen 1999 | 3 | 133 | 7 | 137 | 0.43 [0.11, 1.69] |

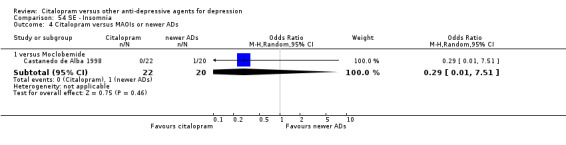

| Citalopram vs moclobemide | ||||||

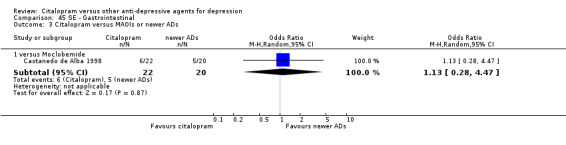

| Gastrointestinal | Castanedo de Alba 1998 | 6 | 22 | 5 | 20 | 1.13 [0.28, 4.47] |

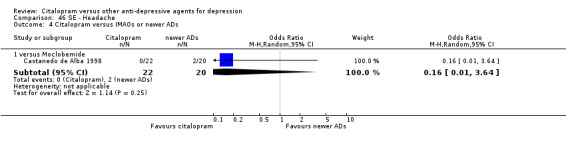

| Headache | Castanedo de Alba 1998 | 0 | 22 | 2 | 20 | 0.16 [0.01, 3.64] |

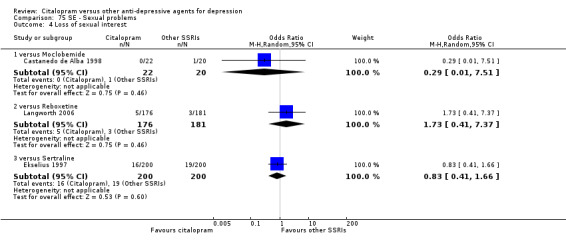

| Sexual problems: loss of sexual interest | Castanedo de Alba 1998 | 0 | 22 | 1 | 20 | 0.29 [0.01, 7.51] |

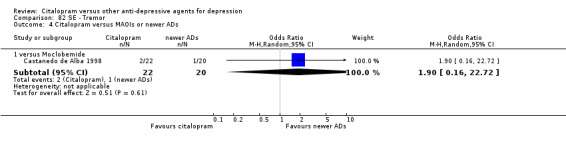

| Tremor | Castanedo de Alba 1998 | 2 | 22 | 1 | 20 | 1.90 [0.16, 22.72] |

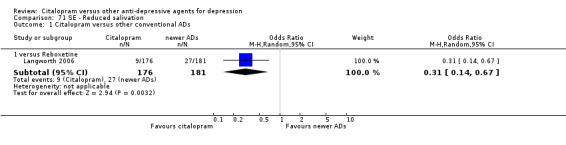

| Citalopram vs reboxetine | ||||||

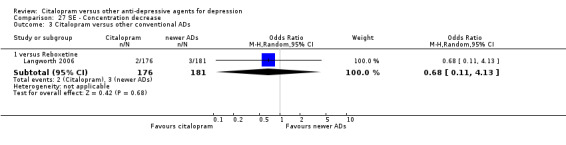

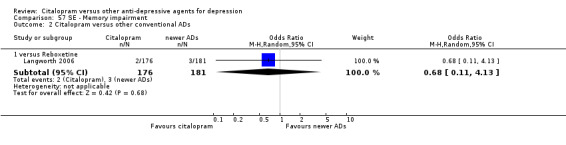

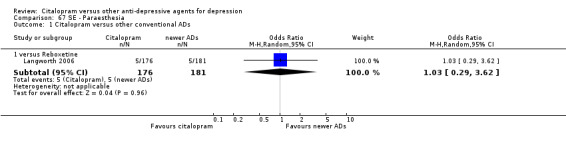

| Concentration decrease | Langworth 2006 | 2 | 176 | 3 | 181 | 0.68 [0.11, 4.13] |

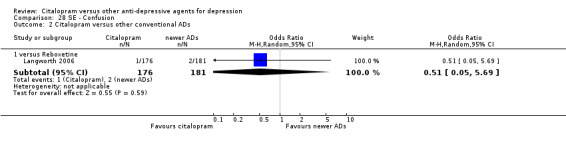

| Confusion | Langworth 2006 | 1 | 176 | 2 | 181 | 0.51 [0.05, 5.69] |

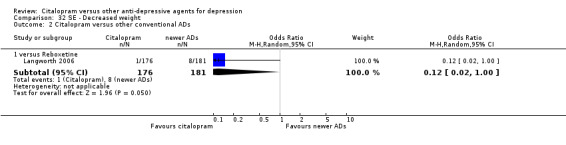

| Decreased weight | Langworth 2006 | 1 | 176 | 8 | 181 | 0.12 [0.02, 1.00] |

| Dizziness | Berlanga 2006 | 13 | 54 | 14 | 47 | 0.75 [0.31, 1.81] |

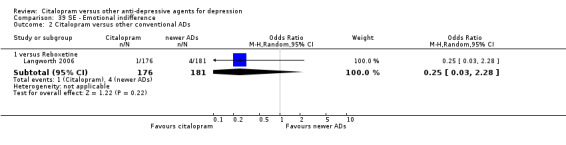

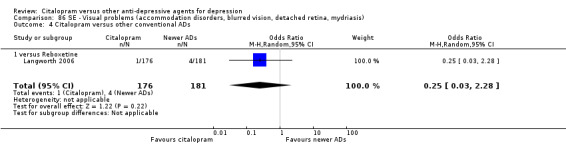

| Emotional indifference | Langworth 2006 | 1 | 176 | 4 | 181 | 0.25 [0.03, 2.28] |

| Headache | Berlanga 2006; Langworth 2006 | 17 | 230 | 27 | 228 | 0.50 [0.25, 1.00] |

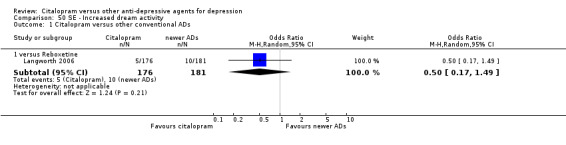

| Increased dream activity | Langworth 2006 | 5 | 176 | 10 | 181 | 0.50 [0.17, 1.49] |

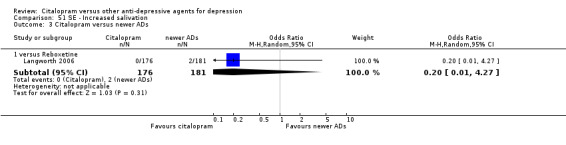

| Increased salivation | Langworth 2006 | 0 | 176 | 2 | 181 | 0.20 [0.01, 4.27] |

| Influenza‐like symptoms | Langworth 2006 | 9 | 176 | 8 | 181 | 1.17 [0.44, 3.09] |

| Memory impairment | Langworth 2006 | 2 | 176 | 3 | 181 | 0.68 [0.11, 4.13] |

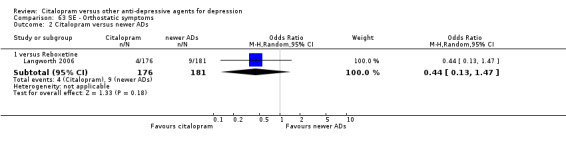

| Orthostatic symptoms | Langworth 2006 | 4 | 176 | 9 | 181 | 0.44 [0.13, 1.47] |

| Paraesthesia | Langworth 2006 | 5 | 176 | 5 | 181 | 1.03 [0.29, 3.62] |

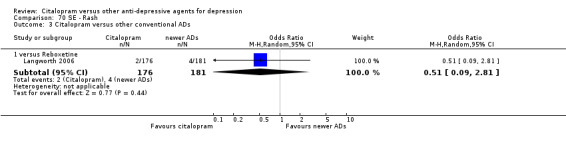

| Rash | Langworth 2006 | 2 | 176 | 4 | 181 | 0.51 [0.09, 2.81] |

| Sexual problems: loss of sexual interest | Langworth 2006 | 5 | 176 | 3 | 181 | 1.73 [0.41, 7.37] |

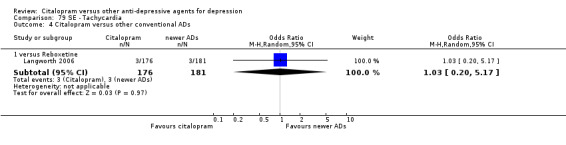

| Tachycardia | Langworth 2006 | 3 | 176 | 3 | 181 | 1.03 [0.20, 5.17] |

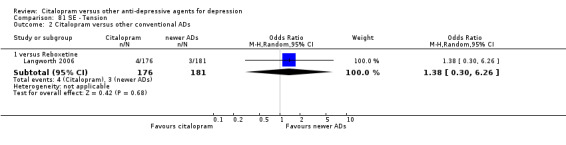

| Tension | Langworth 2006 | 4 | 176 | 3 | 181 | 1.38 [0.30, 6.26] |

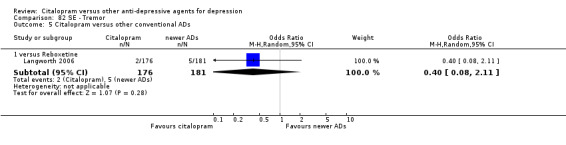

| Tremor | Langworth 2006 | 2 | 176 | 5 | 181 | 0.40 [0.08, 2.11] |

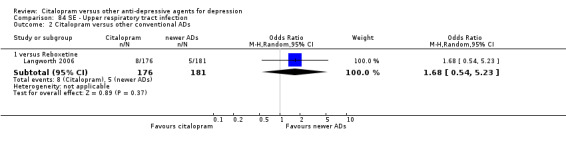

| Upper respiratory tract infection | Langworth 2006 | 8 | 176 | 5 | 181 | 1.68 [0.54, 5.23] |

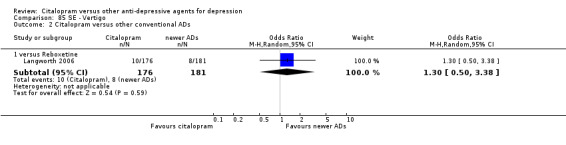

| Vertigo | Langworth 2006 | 10 | 176 | 8 | 181 | 1.30 [0.50, 3.38] |

| Visual problems | Langworth 2006 | 1 | 176 | 4 | 181 | 0.25 [0.03, 2.28] |

| Weight gain | Berlanga 2006; Langworth 2006 | 21 | 230 | 8 | 228 | 2.37 [0.61, 9.19] |

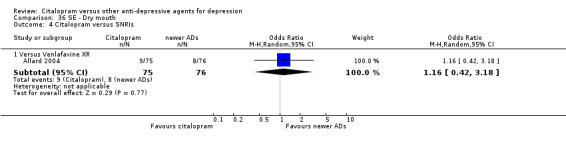

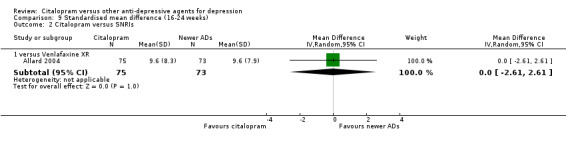

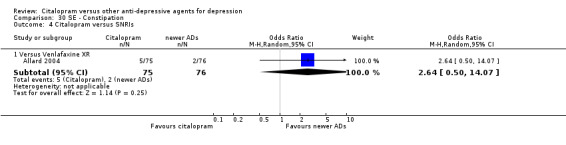

| Citalopram vs venlafaxine XR | ||||||

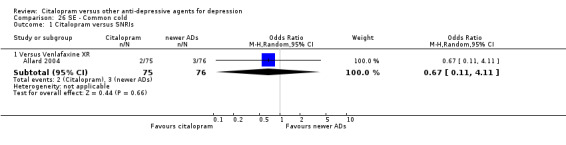

| Common cold | Allard 2004 | 2 | 75 | 3 | 76 | 0.67 [0.11, 4.11] |

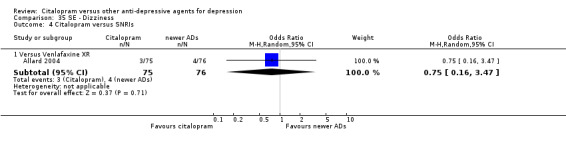

| Dizziness | Allard 2004 | 3 | 75 | 4 | 76 | 0.75 [0.16, 3.47] |

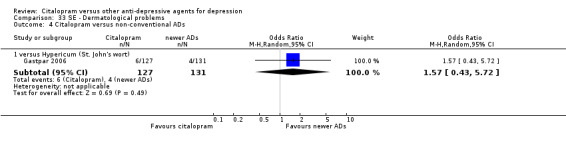

| Citalopram vs hypericum (St. John's wort) | ||||||

| Dermatological problems | Gastpar 2006 | 6 | 127 | 4 | 131 | 1.57 [0.43, 5.72] |

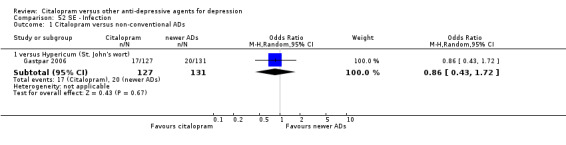

| Infection | Gastpar 2006 | 17 | 127 | 20 | 131 | 0.86 [0.43, 1.72] |

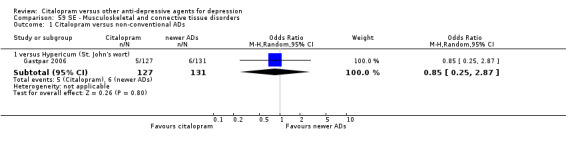

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | Gastpar 2006 | 5 | 127 | 6 | 131 | 0.85 [0.25, 2.87] |

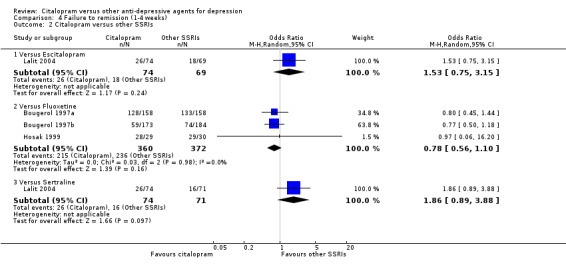

1. CITALOPRAM versus TCAs

PRIMARY OUTCOME

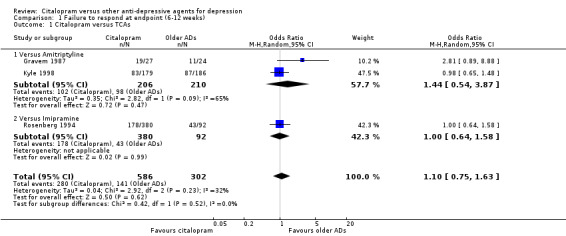

EFFICACY ‐ Number of patients who responded to treatment (six to 12 weeks)

The analysis found no difference in terms of efficacy between citalopram and TCAs in total (OR 1.10, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.63, P = 0.62; 3 trials, 888 participants) nor in head‐to‐head comparisons (Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Failure to respond at endpoint (6‐12 weeks), Outcome 1 Citalopram versus TCAs.

SECONDARY OUTCOMES

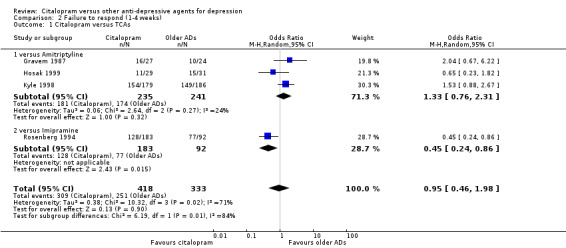

1) EFFICACY ‐ Number of patients who responded to treatment

a) Early response (one to four weeks)

There was no evidence that citalopram was more effective than TCAs in total in terms of early response (OR 0.95, 95% CI 0.46 to 1.98, P = 0.90; 4 trials, 751 participants) (Analysis 2.1). In head‐to‐head comparisons citalopram was more efficacious than imipramine (OR 0.45, 95% CI 0.24 to 0.86, P = 0.01; one trial, 275 participants; NNTB 4, 95% CI 4 to 25) (Analysis 2.1).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Failure to respond (1‐4 weeks), Outcome 1 Citalopram versus TCAs.

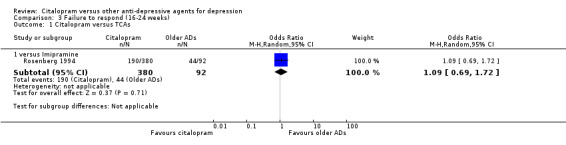

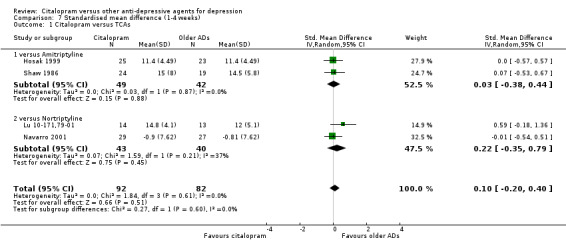

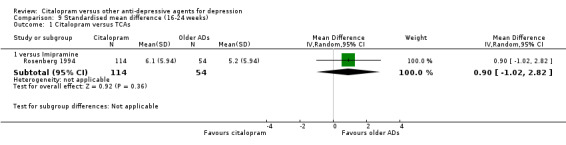

b) Follow‐up response (16 to 24 weeks)

There was no evidence that citalopram was more effective than imipramine (Analysis 3.1).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Failure to respond (16‐24 weeks), Outcome 1 Citalopram versus TCAs.

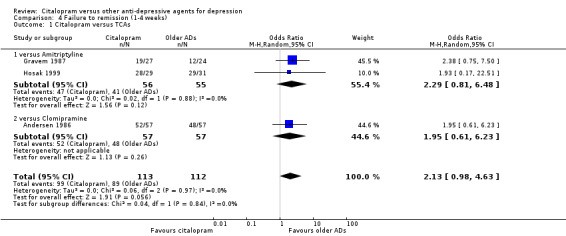

2) EFFICACY ‐ Number of patients who remitted

a) Acute phase treatment (six to 12 weeks)

There was no difference between citalopram and TCAs, neither as a group (5 trials, 256 participants) nor as individual drugs in terms of remission (Analysis 5.1).

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Failure to remission (6‐12 weeks), Outcome 1 Citalopram versus TCAs.

b) Early remission (one to four weeks)

There was no difference between citalopram and TCAs, neither as a group (3 trials, 225 participants) nor as individual drugs (see Analysis 4.1).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Failure to remission (1‐4 weeks), Outcome 1 Citalopram versus TCAs.

c) Follow‐up remission (16 to 24 weeks)

No data available.

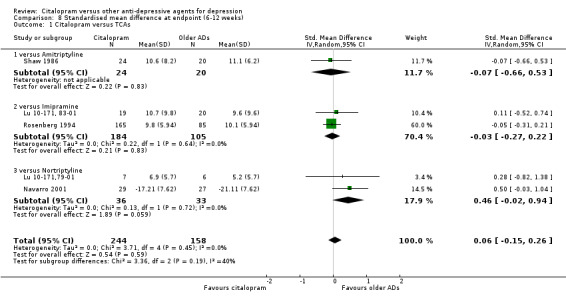

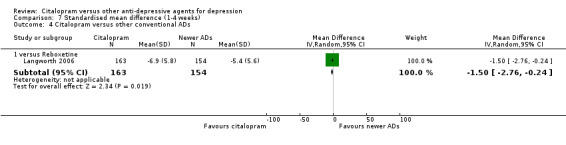

3) EFFICACY ‐ Mean change from baseline

a) Acute phase treatment: between six and 12 weeks

Using rating scale scores, there was no evidence that citalopram was different from TCAs, neither as a group (5 trials, 402 participants) nor as individual drugs (see Analysis 8.1).

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Standardised mean difference at endpoint (6‐12 weeks), Outcome 1 Citalopram versus TCAs.

b) Early response (one to four weeks)

There was no difference between citalopram and TCAs neither individually nor as a class (see Analysis 7.1).

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Standardised mean difference (1‐4 weeks), Outcome 1 Citalopram versus TCAs.

c) Follow‐up response (16 to 24 weeks)

There was no evidence that citalopram was less effective than imipramine (Analysis 9.1).

9.1. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Standardised mean difference (16‐24 weeks), Outcome 1 Citalopram versus TCAs.

4) EFFICACY‐ Social adjustment, social functioning, health‐related quality of life, costs to healthcare services

No data available.

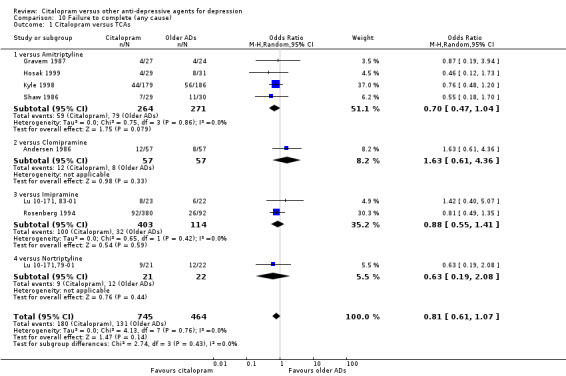

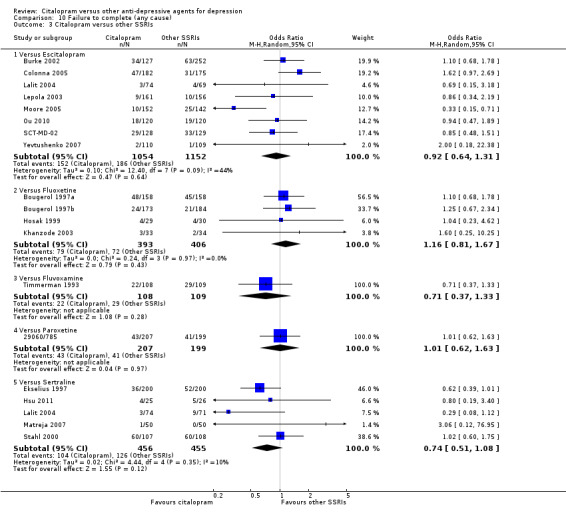

5) ACCEPTABILITY ‐ Dropout rate

a) No statistically significant difference was found between citalopram and TCAs in terms of discontinuation due to any cause. However, even though not significant, we observed a trend in favour of citalopram (OR 0.81 95% CI 0.61 to 1.07, P = 0.14; 8 studies, 1209 participants) (Analysis 10.1).

10.1. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Failure to complete (any cause), Outcome 1 Citalopram versus TCAs.

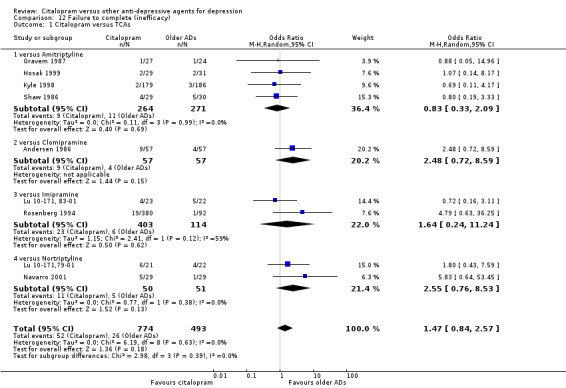

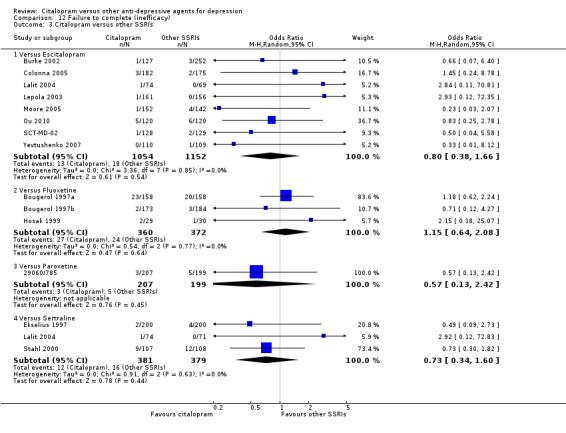

b) No differences were found in terms of discontinuation due to inefficacy (Analysis 12.1).

12.1. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Failure to complete (inefficacy), Outcome 1 Citalopram versus TCAs.

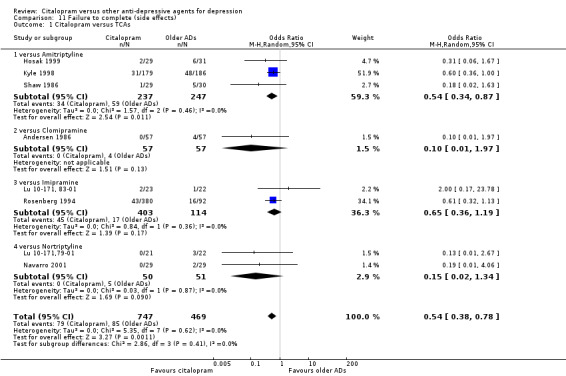

c) Differences were found in terms of discontinuation due to side effects: patients allocated to citalopram were less likely to withdraw than patients allocated to amitriptyline (OR 0.54, 95% CI 0.34 to 0.87, P = 0.01; 3 studies, 484 participants; NNTH 10, 95% CI 6 to 34) and to TCAs as a group (OR 0.54, 95% CI 0.38 to 0.78, P = 0.001; 8 studies, 1216 participants; NNTH 15, 95% CI 9 to 25) (Analysis 11.1; Figure 3)

11.1. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Failure to complete (side effects), Outcome 1 Citalopram versus TCAs.

3.

Forest plot of comparison: 11 Failure to complete (side effects), outcome: 11.1 Citalopram versus TCAs.

6) TOLERABILITY

Total number of patients experiencing at least some side effects.

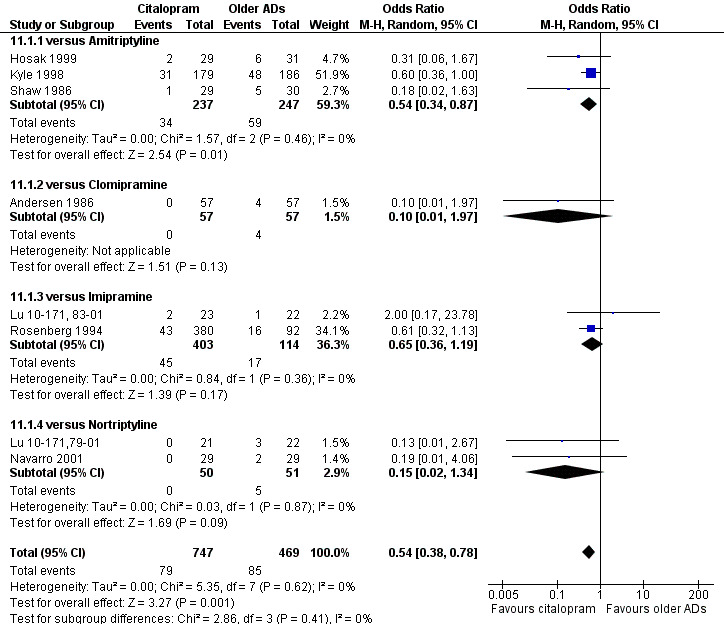

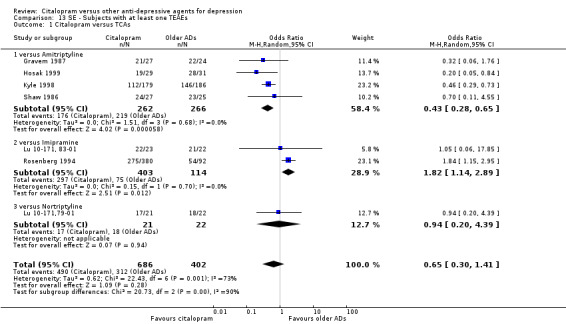

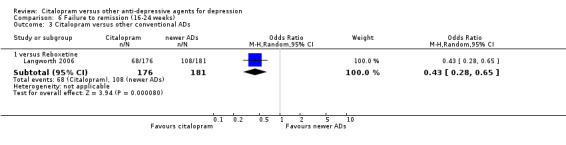

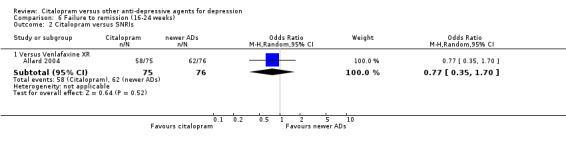

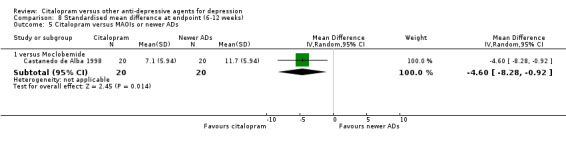

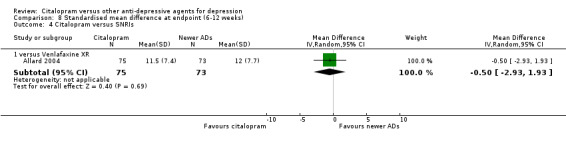

There was evidence that citalopram was associated with a lower rate of adverse events than amitriptyline (OR 0.43, 95% CI 0.28 to 0.65, P < 0.0001; 4 studies, 528 participants; NNTH 8, 95% CI 5 to 15 ‐ Analysis 13.1) and with a higher rate of adverse events than imipramine (OR 1.82, 95% CI 1.14 to 2.89, P = 0.01; 2 studies 517 participants ‐ Analysis 13.1). By contrast, there was no evidence that citalopram was associated with a smaller or higher rate of adverse events than nortriptyline (OR 0.94, 95% CI 0.20 to 4.39; 1 study 43 participants ‐ Analysis 13.1).

13.1. Analysis.

Comparison 13 SE ‐ Subjects with at least one TEAEs, Outcome 1 Citalopram versus TCAs.

Number of patients experiencing specific side effects (only figures for statistically significant differences were reported in the text)

a) Anxiety/agitation

There was no evidence that citalopram was associated with a lower rate of participants experiencing agitation/anxiety than nortriptyline (Analysis 18.1).

18.1. Analysis.

Comparison 18 SE ‐ Anxiety/agitation, Outcome 1 Citalopram versus TCAs.

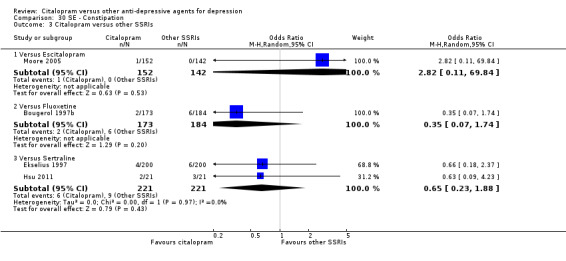

b) Constipation

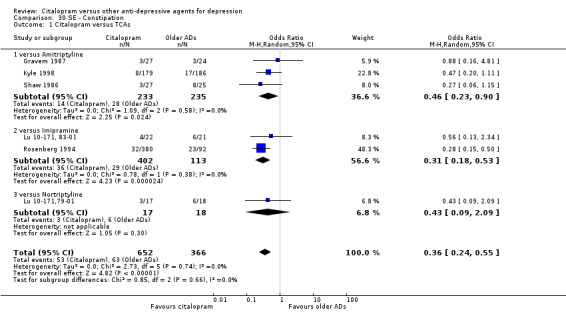

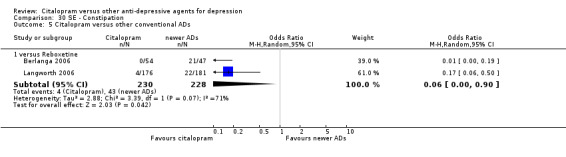

There was evidence that citalopram was associated with a lower rate of participants experiencing constipation than TCAs (OR 0.36, 95% CI 0.24 to 0.55, P < 0.00001; 6 trials, 1018 participants; NNTH 10, 95% CI 6 to 34 ‐ Analysis 30.1). In head‐to‐head comparison, the difference was statistically significant in favour of citalopram when compared with amitriptyline (OR 0.46, 95% CI 0.23 to 0.90, P = 0.02; 3 studies, 468 participants ‐ Analysis 30.1) and imipramine (OR 0.31, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.53, P < 0.0001; 2 studies, 515 participants; NNTH 7, 95% CI 4 to 15 ‐ Analysis 30.1), respectively.

30.1. Analysis.

Comparison 30 SE ‐ Constipation, Outcome 1 Citalopram versus TCAs.

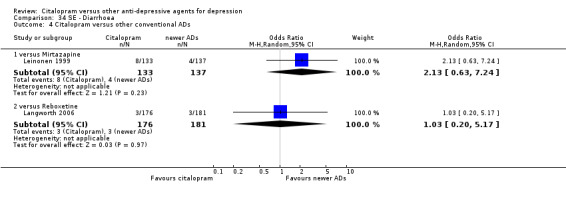

c) Diarrohea

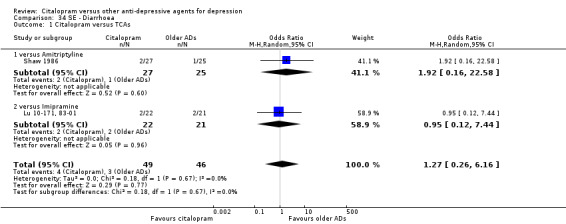

There was no evidence that citalopram was associated with a different rate of participants experiencing diarrhoea than amitriptyline or imipramine (Analysis 34.1).

34.1. Analysis.

Comparison 34 SE ‐ Diarrhoea, Outcome 1 Citalopram versus TCAs.

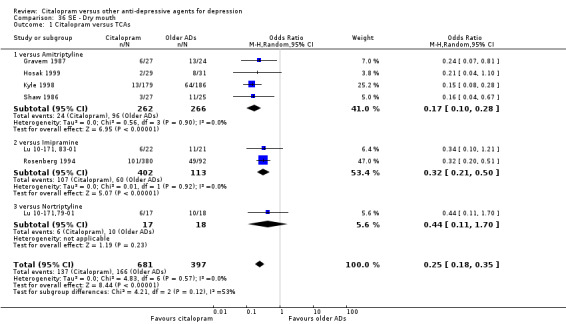

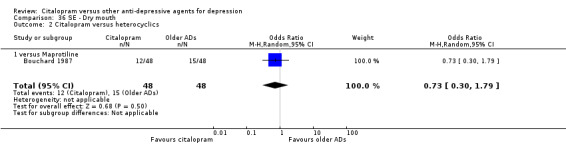

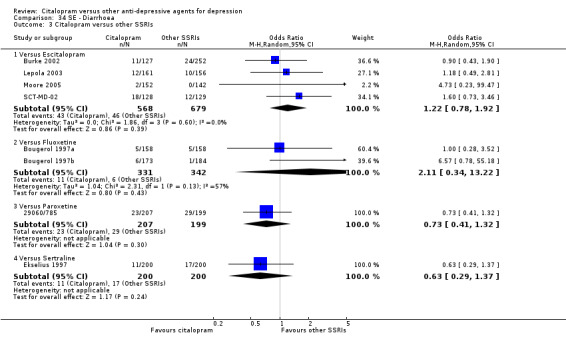

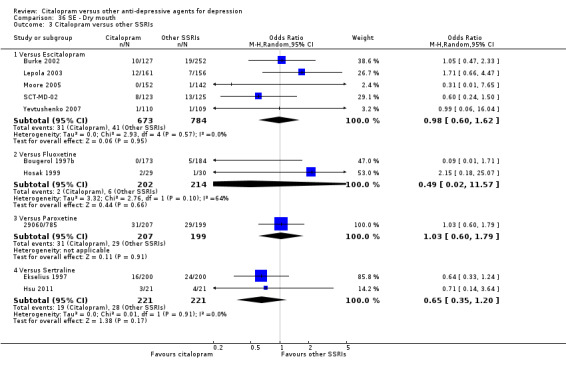

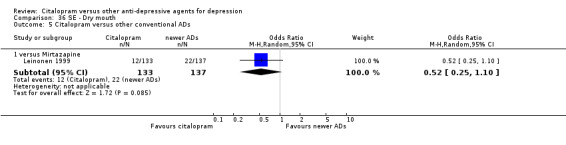

d) Dry mouth

There was evidence that citalopram was associated with a lower rate of participants experiencing dry mouth than TCAs (OR 0.25, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.35, P < 0.00001; 7 trials, 1078 participants; NNTH 4, 95% CI 3 to 5 ‐ Analysis 36.1). In head‐to‐head comparisons, the difference between citalopram and imipramine was statistically significant in favour of citalopram (OR 0.32, 95% CI 0.21 to 0.50, P < 0.00001; 2 trials, 515 participants; NNTH 4, 95% CI 3 to 7); furthermore, citalopram was associated with a lower rate of patients experiencing dry mouth than amitriptyline (OR 0.17, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.28, P < 0.00001; 4 trials, 528 participants; NNTH 4, 95% CI 3 to 5 ‐ Analysis 36.1).

36.1. Analysis.

Comparison 36 SE ‐ Dry mouth, Outcome 1 Citalopram versus TCAs.

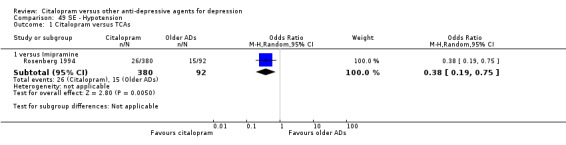

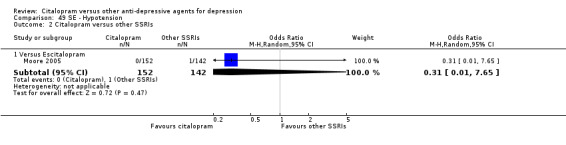

e) Hypotension

Citalopram was associated with lower rate of patients experiencing hypotension than imipramine (OR 0.38, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.75, P = 0.005; 1 trial, 472 participants ‐ Analysis 49.1).

49.1. Analysis.

Comparison 49 SE ‐ Hypotension, Outcome 1 Citalopram versus TCAs.

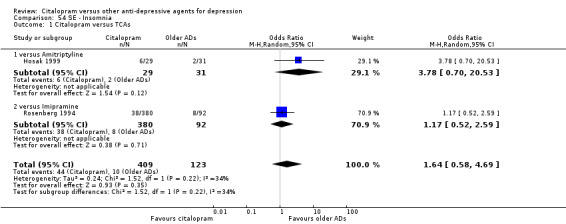

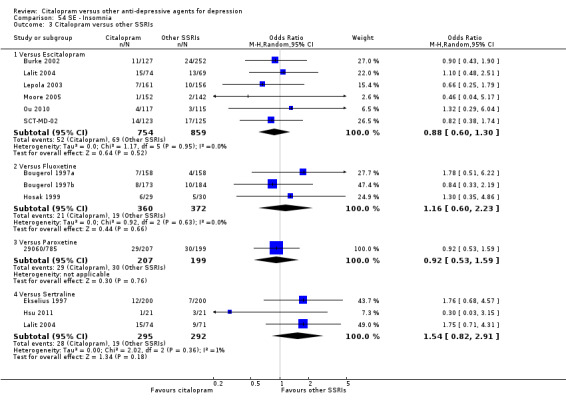

f) Insomnia

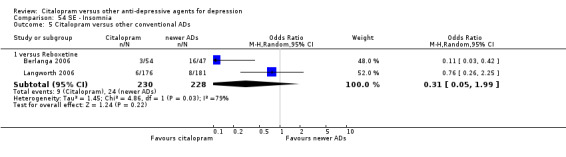

There was no evidence that citalopram was associated with a higher rate of participants experiencing insomnia than TCAs (Analysis 54.1).

54.1. Analysis.

Comparison 54 SE ‐ Insomnia, Outcome 1 Citalopram versus TCAs.

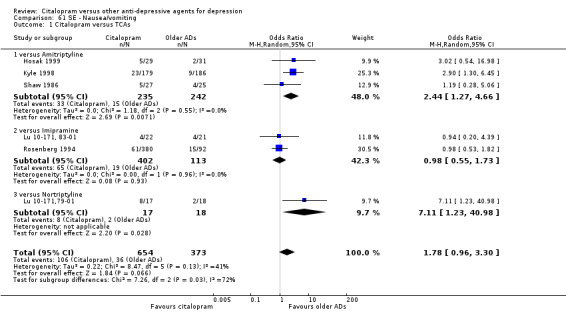

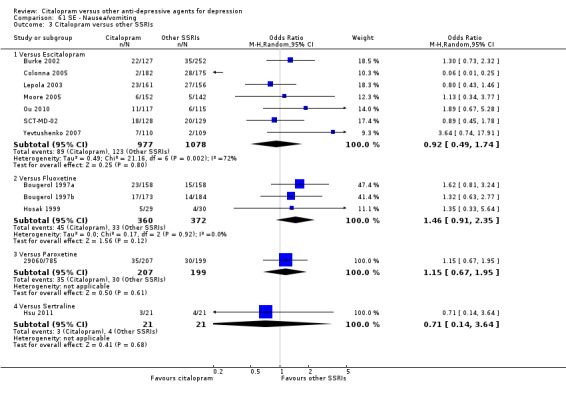

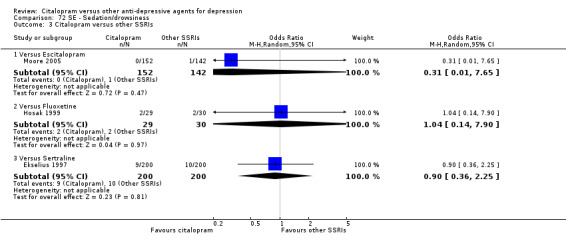

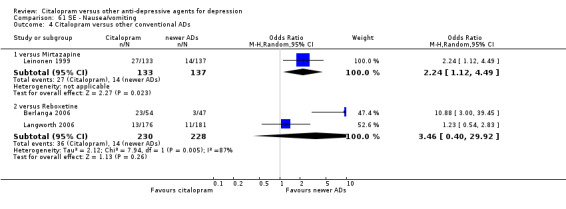

g) Nausea/vomiting

There was evidence that citalopram was associated with a higher rate of participants experiencing nausea than amitriptyline (OR 2.44, 95% CI 1.27 to 4.66, P = 0.007; 3 trials, 477 participants ‐ Analysis 61.1) and nortriptyline (OR 7.11, 95% CI 1.23 to 40.98; 1 trial, 35 participants ‐ Analysis 61.1 ).

61.1. Analysis.

Comparison 61 SE ‐ Nausea/vomiting, Outcome 1 Citalopram versus TCAs.

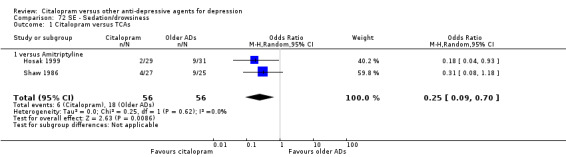

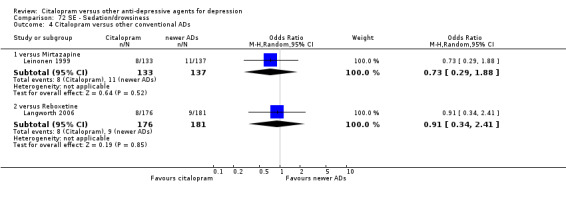

h) Sedation/drowsiness

In head‐to‐head comparisons, citalopram was associated with a lower rate of patients experiencing sedation/drowsiness than amitriptyline (OR 0.25, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.70, P = 0.009; 2 studies, 112 participants ‐ Analysis 72.1).

72.1. Analysis.

Comparison 72 SE ‐ Sedation/drowsiness, Outcome 1 Citalopram versus TCAs.

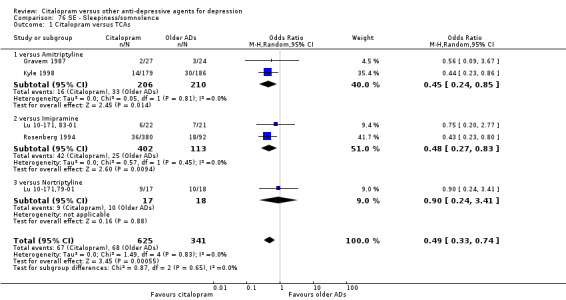

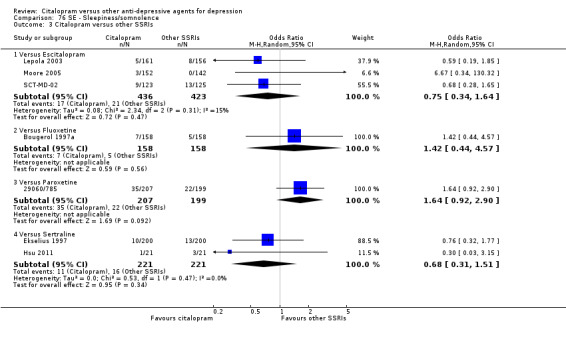

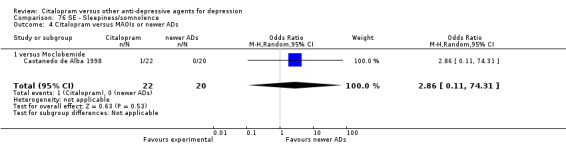

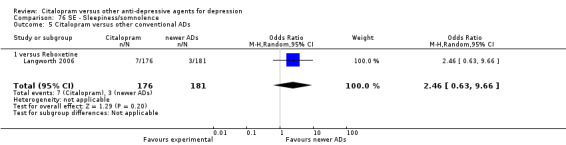

i) Sleepiness/somnolence

There was evidence that citalopram was associated with a lower rate of participants experiencing sleepiness/somnolence than TCAs (OR 0.49, 95% CI 0.33 to 0.74, P = 0.0006; 5 trials, 966 participants ‐ Analysis 76.1). In head‐to‐head comparisons, the difference between citalopram and amitriptyline was statistically significant in favour of citalopram (OR 0.45, 95% CI 0.24 to 0.85, P < 0.00001; 2 trials, 416 participants); furthermore, citalopram was associated with a lower rate of patients experiencing sleepiness than imipramine (OR 0.48, 95% CI 0.27 to 0.83, P = 0.009; 2 studies, 515 participants ‐ Analysis 76.1).

76.1. Analysis.

Comparison 76 SE ‐ Sleepiness/somnolence, Outcome 1 Citalopram versus TCAs.

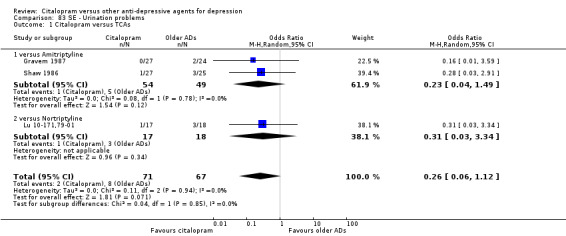

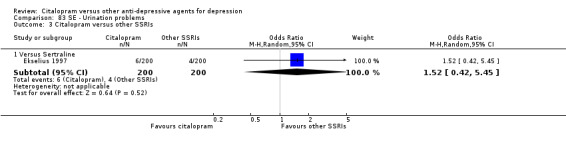

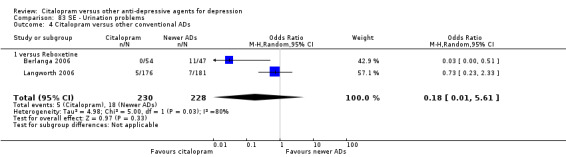

j) Urination problems

There was no evidence that citalopram was associated with a lower rate of participants experiencing urination problems than TCAs (Analysis 83.1).

83.1. Analysis.

Comparison 83 SE ‐ Urination problems, Outcome 1 Citalopram versus TCAs.

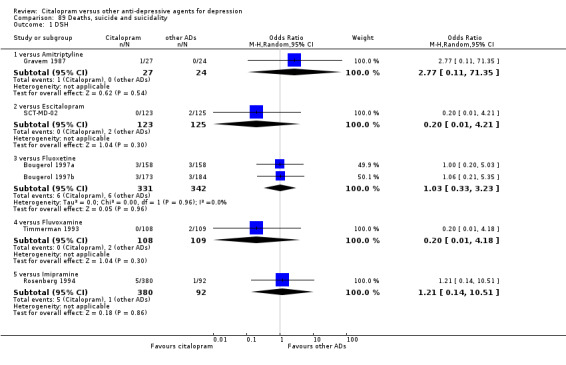

k) Suicide wishes/gestures/attempts

There was no difference between citalopram and TCAs, neither as a group nor as individual drugs (Analysis 89.1).

89.1. Analysis.

Comparison 89 Deaths, suicide and suicidality, Outcome 1 DSH.

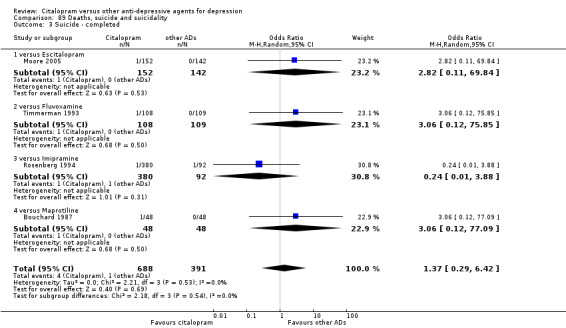

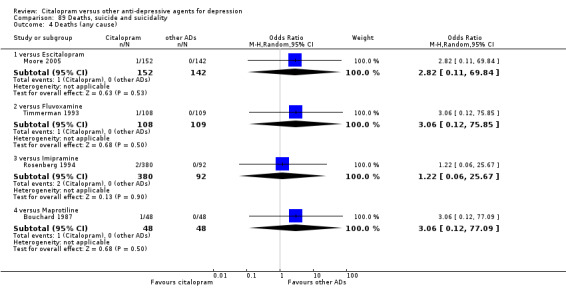

l) Deaths (all cause)/Completed suicide

There was no difference between citalopram and imipramine (Analysis 89.3; Analysis 89.4).

89.3. Analysis.

Comparison 89 Deaths, suicide and suicidality, Outcome 3 Suicide ‐ completed.

89.4. Analysis.

Comparison 89 Deaths, suicide and suicidality, Outcome 4 Deaths (any cause).

m) Other adverse events

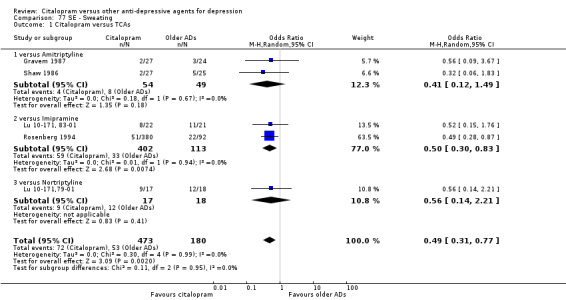

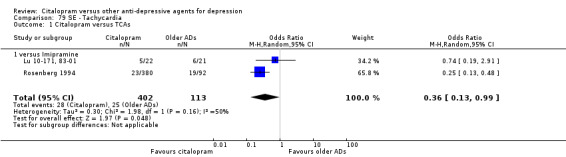

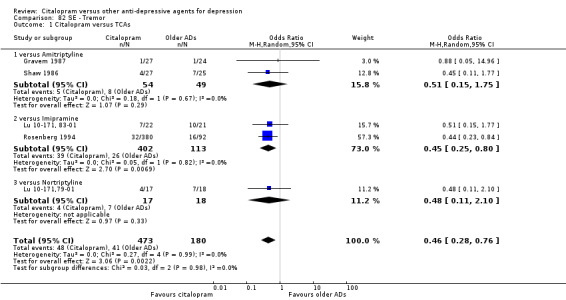

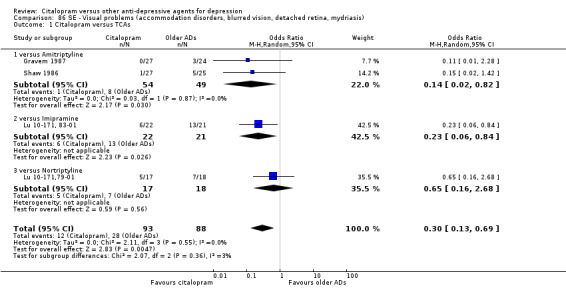

Citalopram was associated with a lower rate of participants experiencing sweating (OR 0.50, 95% CI 0.30 to 0.83, P = 0.007; two studies, 515 participants ‐ Analysis 77.1), tachycardia (OR 0.36, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.99, P = 0.05; 2 trials, 515 participants ‐ Analysis 79.1), tremor (OR 0.45, 95% CI 0.25 to 0.80, P = 0.007; 2 studies, 515 participants ‐ Analysis 82.1) and visual problems (OR 0.23, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.84, P = 0.03; 1 study, 43 participants ‐ Analysis 86.1) than imipramine. Citalopram was associated with a lower rate of participants experiencing visual problems (OR 0.14, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.82, P = 0.03; 2 studies, 103 participants ‐ Analysis 86.1) than amitriptyline.

77.1. Analysis.

Comparison 77 SE ‐ Sweating, Outcome 1 Citalopram versus TCAs.

79.1. Analysis.

Comparison 79 SE ‐ Tachycardia, Outcome 1 Citalopram versus TCAs.

82.1. Analysis.

Comparison 82 SE ‐ Tremor, Outcome 1 Citalopram versus TCAs.

86.1. Analysis.

Comparison 86 SE ‐ Visual problems (accommodation disorders, blurred vision, detached retina, mydriasis), Outcome 1 Citalopram versus TCAs.

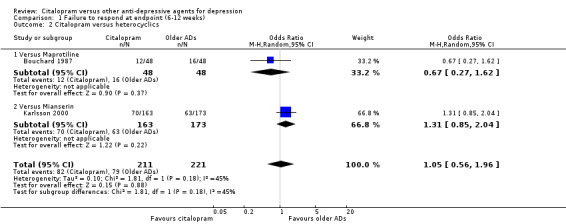

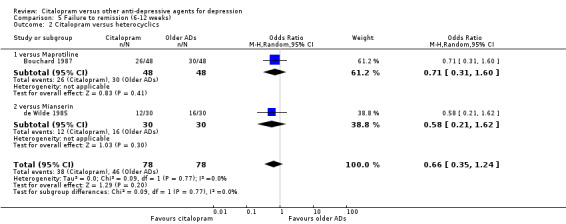

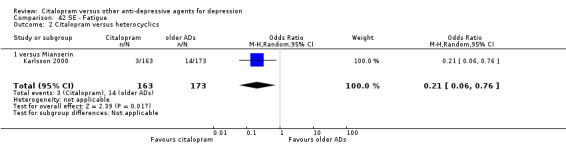

2. CITALOPRAM versus HETEROCYCLICS

PRIMARY OUTCOME

EFFICACY ‐ Number of patients who responded to treatment (six to 12 weeks)

The analysis found no difference in terms of efficacy between citalopram and heterocyclics in total (OR 1.05, 95% CI 0.56 to 1.96, P = 0.88; 2 trials, 432 participants) nor in head‐to‐head comparisons (Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Failure to respond at endpoint (6‐12 weeks), Outcome 2 Citalopram versus heterocyclics.

SECONDARY OUTCOMES

1) EFFICACY ‐ Number of patients who responded to treatment

a) Early response (one to four weeks)

No data available.

b) Follow‐up response (16 to 24 weeks)

No data available.

2) EFFICACY ‐ Number of patients who remitted

a) Acute phase treatment (six to 12 weeks)

There was no difference between citalopram and heterocyclics, neither as a group (5 trials, 256 participants) nor as individual drugs in terms of remission (Analysis 5.2).

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Failure to remission (6‐12 weeks), Outcome 2 Citalopram versus heterocyclics.

b) Early remission (one to four weeks)

No data available.

c) Follow‐up remission (16 to 24 weeks)

No data available.

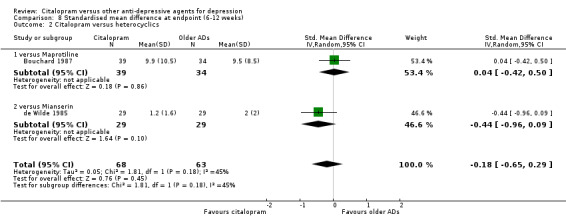

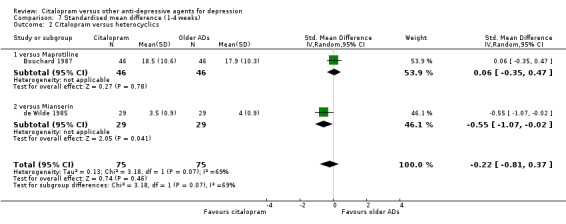

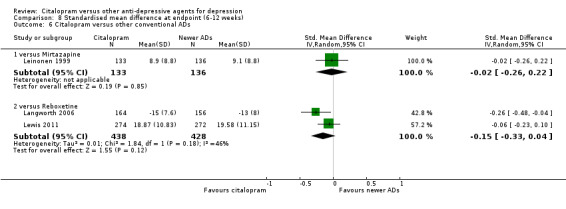

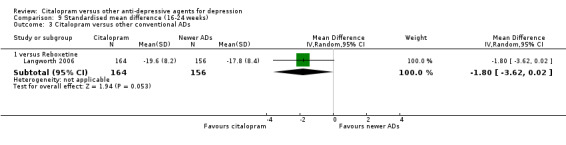

3) EFFICACY ‐ Mean change from baseline

a) Acute phase treatment: between 6 and 12 weeks

Using rating scale scores, there was no evidence that citalopram was different from heterocyclics, neither as a group (2 trials, 131 participants) nor as individual drugs (Analysis 8.2).

8.2. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Standardised mean difference at endpoint (6‐12 weeks), Outcome 2 Citalopram versus heterocyclics.

b) Early response (1 to 4 weeks)

There was evidence that citalopram was more effective than mianserin (SMD ‐0.55, 95% CI ‐1.07 to ‐0.02, P = 0.04, 1 trial, 58 participants) (see Analysis 7.2). There was no difference between citalopram and heterocyclics as a class.

7.2. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Standardised mean difference (1‐4 weeks), Outcome 2 Citalopram versus heterocyclics.

c) Follow‐up response (16 to 24 weeks)

No data available.

4) EFFICACY‐ Social adjustment, social functioning, health‐related quality of life, costs to healthcare services

No data available.

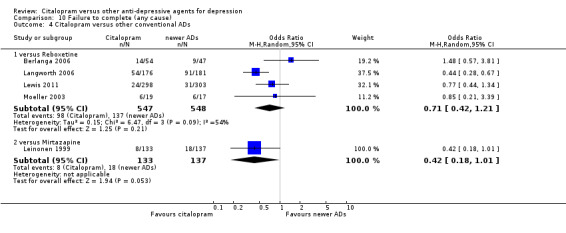

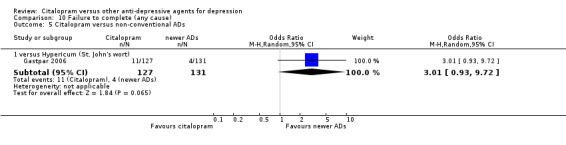

5) ACCEPTABILITY ‐ Dropout rate

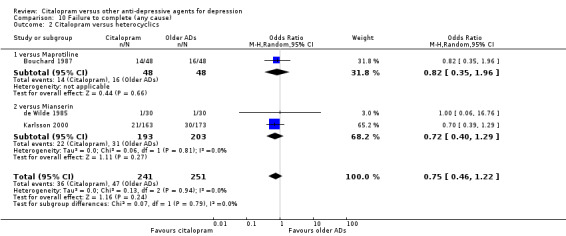

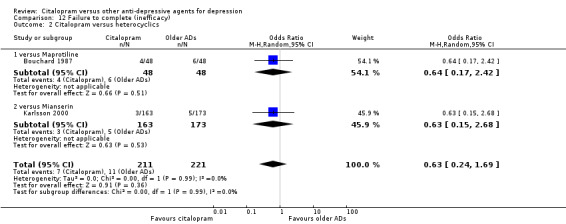

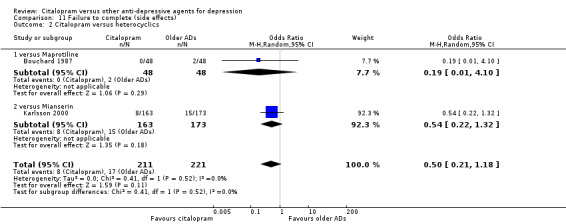

a) No statistically significant difference was found between citalopram and heterocyclics in terms of discontinuation due to any cause (Analysis 10.2), due to inefficacy (Analysis 12.2) or due to side effects (Analysis 11.2)

10.2. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Failure to complete (any cause), Outcome 2 Citalopram versus heterocyclics.

12.2. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Failure to complete (inefficacy), Outcome 2 Citalopram versus heterocyclics.

11.2. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Failure to complete (side effects), Outcome 2 Citalopram versus heterocyclics.

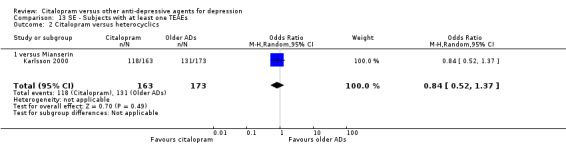

6) TOLERABILITY

Total number of patients experiencing at least some side effects.

There was no evidence that citalopram was associated with a smaller or higher rate of adverse events than mianserin (OR 0.84, 95% CI 0.52 to 1.37; 1 study, 336 participants ‐ Analysis 13.2).

13.2. Analysis.

Comparison 13 SE ‐ Subjects with at least one TEAEs, Outcome 2 Citalopram versus heterocyclics.

Number of patients experiencing specific side effects (only figures for statistically significant differences were reported in the text)

a) Anxiety/agitation

There was no evidence that citalopram was associated with a lower rate of participants experiencing agitation/anxiety than heterocyclics (Analysis 18.2).

18.2. Analysis.

Comparison 18 SE ‐ Anxiety/agitation, Outcome 2 Citalopram versus heterocyclics.

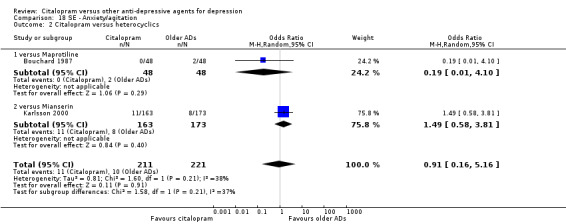

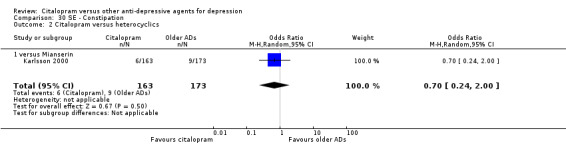

b) Constipation

There was no evidence that citalopram was associated with a lower rate of participants experiencing constipation than mianserin (Analysis 30.2)

30.2. Analysis.

Comparison 30 SE ‐ Constipation, Outcome 2 Citalopram versus heterocyclics.

c) Diarrohea

There was no evidence that citalopram was associated with a lower rate of participants experiencing diarrhoea than maprotiline (Analysis 34.1).

d) Dry mouth

There was no evidence that citalopram was associated with a lower rate of participants experiencing diarrhoea than maprotiline (Analysis 36.2).

36.2. Analysis.

Comparison 36 SE ‐ Dry mouth, Outcome 2 Citalopram versus heterocyclics.

e) Hypotension

No data available.

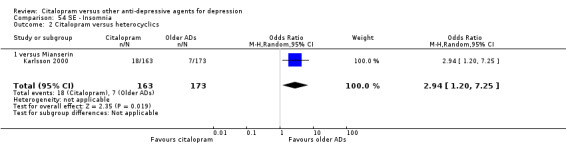

f) Insomnia

Citalopram was associated with higher rate of patients experiencing insomnia than mianserin (OR 2.94, 95% CI 1.20 to 7.25; 1 trial, 336 participants ‐ Analysis 54.2).

54.2. Analysis.

Comparison 54 SE ‐ Insomnia, Outcome 2 Citalopram versus heterocyclics.

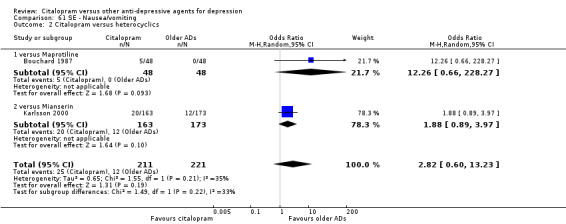

g) Nausea/vomiting

There was no evidence that citalopram was associated with a higher rate of participants experiencing nausea than heterocyclics (Analysis 61.2).

61.2. Analysis.

Comparison 61 SE ‐ Nausea/vomiting, Outcome 2 Citalopram versus heterocyclics.

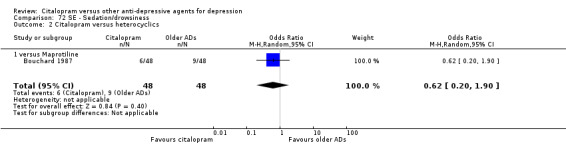

h) Sedation/drowsiness

There was no evidence that citalopram was associated with a higher rate of participants experiencing nausea than maprotiline (Analysis 72.2).

72.2. Analysis.

Comparison 72 SE ‐ Sedation/drowsiness, Outcome 2 Citalopram versus heterocyclics.

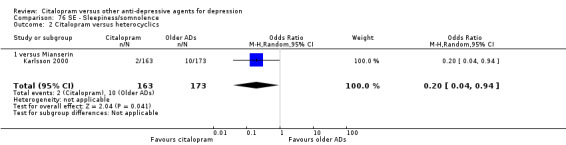

i) Sleepiness/somnolence

Citalopram was associated with a lower rate of patients experiencing sleepiness than mianserin (OR 0.20, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.94; 1 trial, 336 participants ‐ Analysis 76.2).

76.2. Analysis.

Comparison 76 SE ‐ Sleepiness/somnolence, Outcome 2 Citalopram versus heterocyclics.

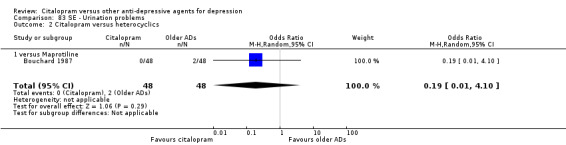

j) Urination problems

There was no evidence that citalopram was associated with a higher rate of participants experiencing urination problems than maprotiline (Analysis 83.2).

83.2. Analysis.

Comparison 83 SE ‐ Urination problems, Outcome 2 Citalopram versus heterocyclics.

k) Suicide wishes/gestures/attempts

No data available

l) Deaths (all cause)/Completed suicide

There was no difference between citalopram and maprotiline (Analysis 89.3; Analysis 89.4).

m) Other adverse events

Citalopram was associated with a lower rate of participants experiencing fatigue than mianserin (OR 0.21, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.76, P = 0.02; 1 trial, 336 participants ‐ Analysis 42.2).

42.2. Analysis.

Comparison 42 SE ‐ Fatigue, Outcome 2 Citalopram versus heterocyclics.

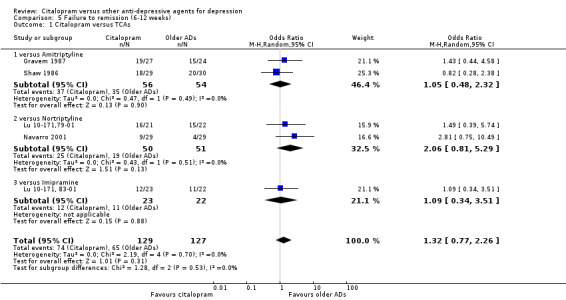

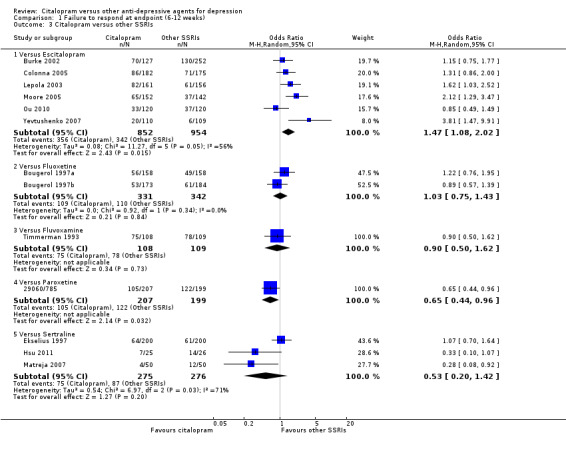

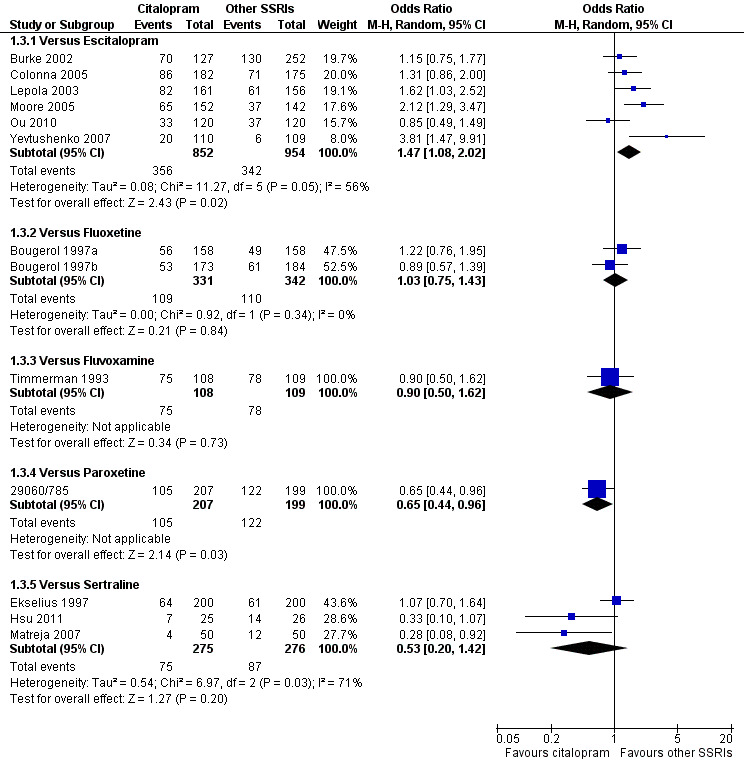

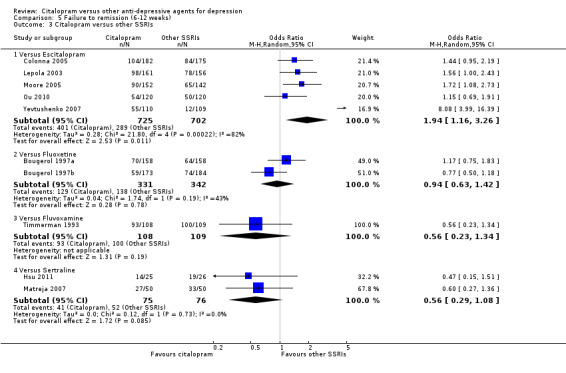

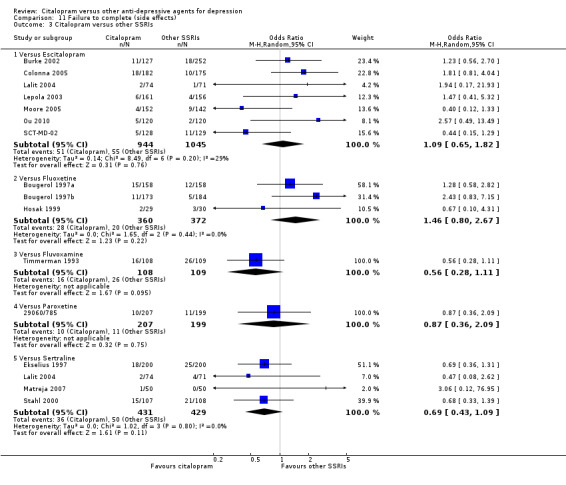

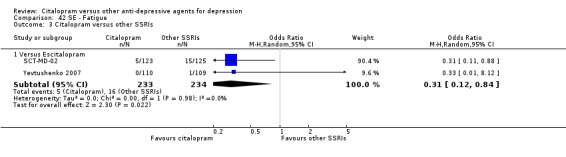

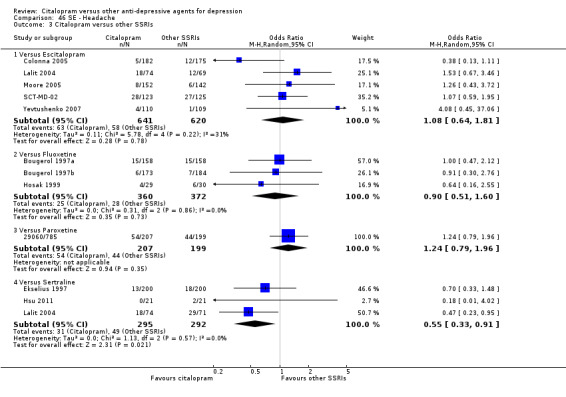

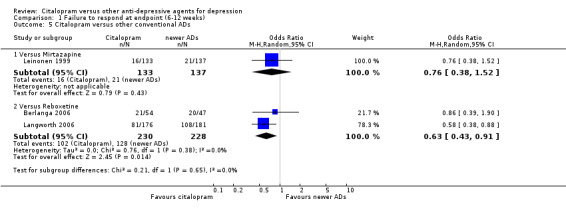

3. CITALOPRAM versus other SSRIs

PRIMARY OUTCOME

EFFICACY ‐ Number of patients who responded to treatment (six to 12 weeks)

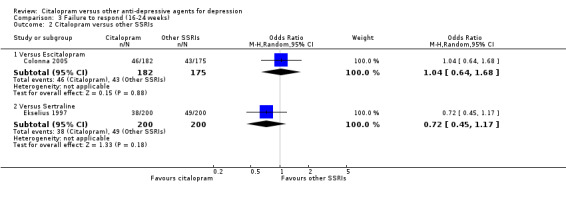

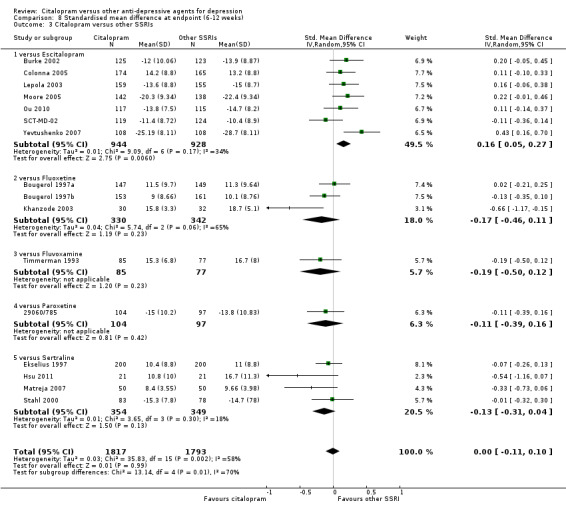

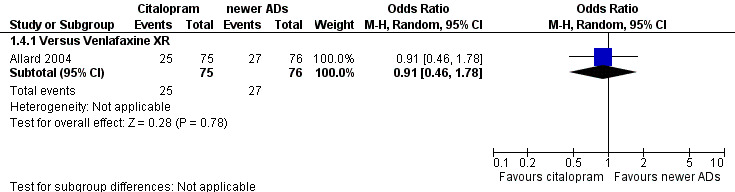

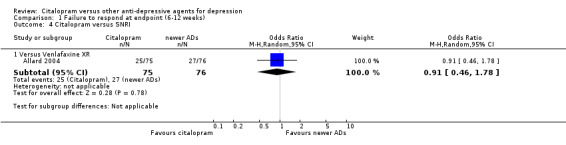

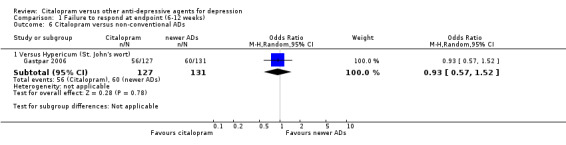

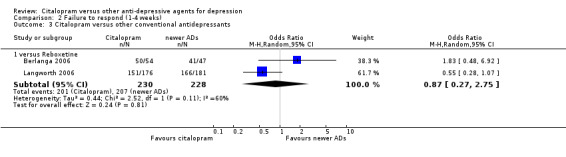

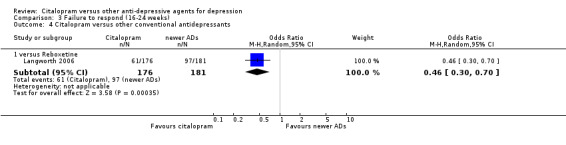

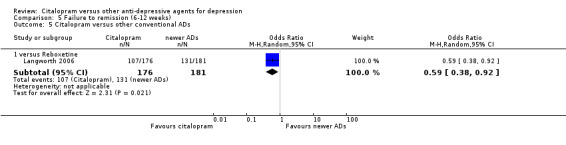

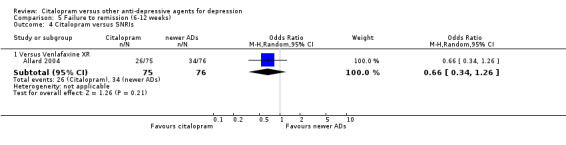

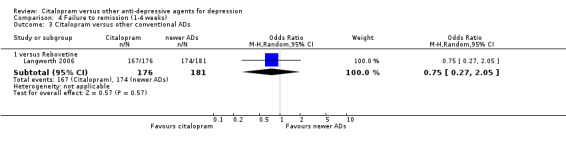

The analysis found that citalopram was less effective than escitalopram (OR 1.47, 95% CI 1.08 to 2.02, P = 0.02, six trials, 1806 participants; NNTB 13, 95% CI 8 to 34) but more effective than paroxetine (OR 0.65, 95% CI 0.44 to 0.96, P = 0.03, 1 trial, 406 participants; NNTB 9, 95% CI 5 to 100) ( Analysis 1.3; Figure 4).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Failure to respond at endpoint (6‐12 weeks), Outcome 3 Citalopram versus other SSRIs.

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Failure to respond at endpoint (6‐12 weeks), outcome: 1.3 Citalopram versus other SSRIs.

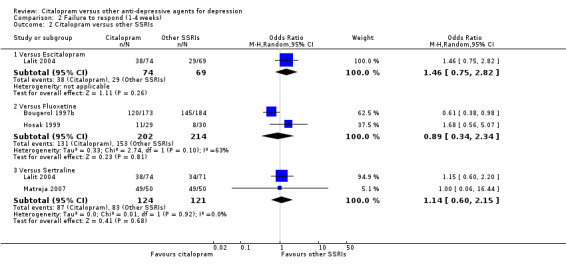

SECONDARY OUTCOMES

1) EFFICACY ‐ Number of patients who responded to treatment

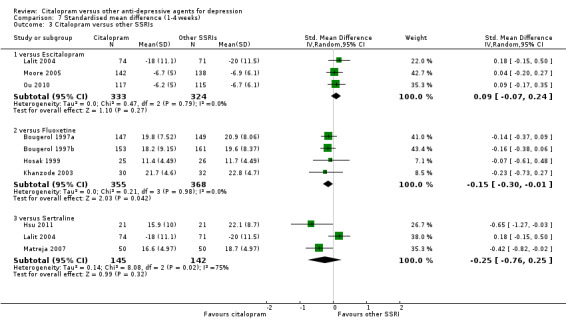

a) Early response (one to four weeks)

There was no evidence that citalopram was more effective than other SSRIs (Analysis 2.2).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Failure to respond (1‐4 weeks), Outcome 2 Citalopram versus other SSRIs.

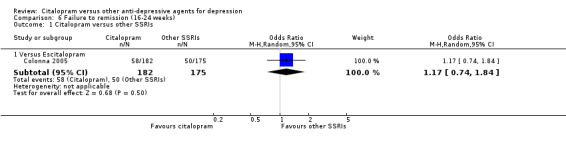

b) Follow‐up response (16 to 24 weeks)

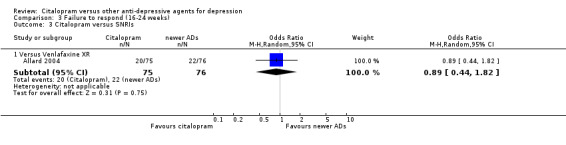

There was no evidence that citalopram was more effective than other SSRIs (Analysis 3.2).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Failure to respond (16‐24 weeks), Outcome 2 Citalopram versus other SSRIs.