Abstract

Background

Patients with cancer must make frequent visits to the clinic not only for chemotherapy but also for the management of treatment-related adverse effects. Neutropenia, the most common dose-limiting toxicity of myelosuppressive chemotherapy, has substantial clinical and economic consequences. Colony-stimulating factors such as filgrastim and pegfilgrastim can reduce the incidence of neutropenia, but the clinic visits for these treatments can disrupt patients' routines and activities.

Methods

We surveyed patients to assess how clinic visits for treatment with chemotherapy and the management of neutropenia affect their time and activities.

Results

The mean amounts of time affected by these visits ranged from approximately 109 hours (hospitalization for neutropenia) and 8 hours (physician and chemotherapy) to less than 3 hours (laboratory and treatment with filgrastim or pegfilgrastim). The visits for filgrastim or pegfilgrastim were comparable in length, but treatment with filgrastim requires several visits per chemotherapy cycle and treatment with pegfilgrastim requires only 1 visit.

Conclusions

This study provides useful information for future modelling of additional factors such as disease status and chemotherapy schedule and provides information that should be considered in managing chemotherapy-induced neutropenia.

Background

Cancer is a devastating disease that affects patients' quality of life. The treatment of cancer also causes problems for patients, such as nausea and vomiting, anemia, and neutropenia [1-6]. Moreover, a diagnosis of cancer necessitates a large number of medical visits for monitoring the disease, treating it, and providing supportive care.

The treatment of cancer may require that patients visit an outpatient clinic numerous times over a course of months or years. Those patients who have employment often have to take time off work for long periods to be treated and have to shift many of their activities and responsibilities because of the time required for treatment. Patients spend time preparing, travelling to the clinic, waiting at the clinic, and travelling from the clinic. These visits affect their normal life activities both in the time taken away from those activities and in their associated costs, such as lost work time. In addition, there can be logistical challenges in transportation and living arrangements and disruptions of work and daily living. The stress associated with these visits can also affect their psychological outlook.

The number of medical visits that are necessary with chemotherapy treatment depends on many factors, including the type and extent of the disease and the schedule of the chemotherapy. One of the factors that can greatly affect the number of visits is chemotherapy-induced neutropenia. Chemotherapy-induced neutropenia is the most common dose-limiting toxicity of myelosuppressive chemotherapy, and it has several economic and clinical consequences [7]. Neutropenia also puts patients at high risk for infection, and it can be life-threatening [7]. If not managed properly, neutropenia can result in a large number of medical visits for monitoring the neutrophil counts, outpatient intravenous antibiotics, physician and nurse visits, and hospitalization [8].

Supportive therapies such as colony-stimulating factors (CSFs) can reduce the incidence of chemotherapy-induced neutropenia [5]. The CSFs filgrastim and pegfilgrastim are indicated to decrease the incidence of infection, as manifested by febrile neutropenia, in patients with nonmyeloid malignancies treated with myelosuppressive anticancer drugs [9,10]. Both of these agents are effective in reducing the risks and incidence of neutropenia and its complications, but they too can affect patients' quality of life, by requiring additional medical visits.

Treatment with filgrastim can require up to 10 or more daily injections per chemotherapy cycle for its full benefits to be obtained; pegfilgrastim, however, is given only once per cycle [11]. The clinic visits that are necessary for managing chemotherapy-induced neutropenia with CSFs can also disrupt patients' lives and create stress.

The purpose of this study was to determine the amounts of time required for medical visits in treatment with chemotherapy and to better understand the implications of the strategies for managing chemotherapy-induced neutropenia.

Methods

Design

All study procedures were approved by the Western Institutional Review Board. The study design was a 20-site single-time-point survey of patients with cancer in community-based oncology practices. Patients were selected in a nonrandom fashion according to the inclusion criteria.

Patients

Patients were enrolled between May 2003 and July 2003. They were required to be at least 18 years old and must have been treated with primary prophylaxis with either filgrastim or pegfilgrastim 1 month before enrollment. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients, and they were not given any monetary incentives or compensations for participating in the study.

Procedures

Patients' disease status and treatment history were ascertained by chart review. Patients were administered the Patient Impact Survey, a semistructured interview created for the study by the primary author, which identified activities that were altered because of the types of medical visits that are typical with a 21-day chemotherapy cycle. See additional data file 1, Doctor and Chemo Survey.pdf, for a sample survey page. Patients were interviewed about 13 kinds of caregiver interactions; the results focus on data from 8 of those events, listed in Table 1. Patients were asked to list the activities that were affected by each visit and to estimate the time associated with them. The total amount of time affected included that for activities that would have normally been done during the time of the visit and the time before and after the visit (eg, travel to and from the medical office, time off work, rescheduled social activities). Data on the most recent medical visit of each type were collected.

Table 1.

Medical visits

| Physician and chemotherapy visit |

| Physician visit |

| Nurse practitioner visit |

| Laboratory visit |

| Intravenous antibiotics |

| Filgrastim visit |

| Pegfilgrastim visit |

| Neutropenia-related hospitalization |

Results

Patient demographics

A total of 189 patients participated. Their demographics are given in Table 2. Most of the patients were women and of white ethnicity; their mean age was 60 years; and 35.6% were employed at the time.

Table 2.

Patient demographics (N = 189)

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 59.9 (13.4) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 51 (27%) |

| Female | 138 (73%) |

| Ethnicity | |

| White | 157 (83.5%) |

| Hispanic | 8 (4%) |

| Black | 19 (10.1%) |

| Asian or Pacific Island | 1 (0.5%) |

| Native American or Alaska Native | 1 (0.5%) |

| Other | 2 (1.1%) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 22 (11.6%) |

| Separated | 1 (0.5%) |

| Divorced | 20 (10.6%) |

| Widowed | 23 (12.2%) |

| Remarried | 1 (0.5%) |

| Married | 122 (64.5%) |

| Work status | |

| Currently working | 67 (35.6%) |

| Unemployed, looking for work | 5 (2.7%) |

| Homemaker | 28 (14.9%) |

| Retired | 87 (46.3%) |

| Student | 1 (0.5%) |

| Education | |

| Less than high school | 2 (1%) |

| Some high school | 22 (11.6%) |

| High school diploma | 53 (28%) |

| Some college | 62 (32.8%) |

| College degree | 29 (15%) |

| Some graduate school | 5 (2.6%) |

| Graduate degree | 16 (8.5%) |

| Annual household income, US$ | |

| <15,000 | 27 (14.3%) |

| 15,000–30,000 | 35 (18.5%) |

| 30,000–50,000 | 39 (21%) |

| 50,000–75,000 | 24 (13%) |

| 75,000–100,000 | 15 (7.9%) |

| 100,000–150,000 | 9 (5%) |

| >150,000 | 10 (5.3%) |

| Prefer not to say | 30 (15.9%) |

Effects on patients

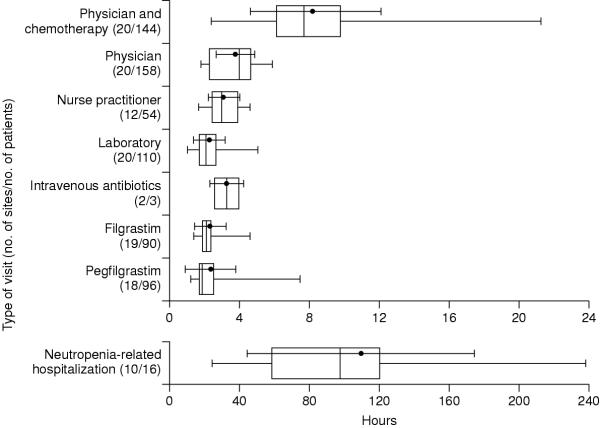

The total amounts of time that were affected by medical visits are shown in Figure 1. These times consist of the time before, during, and after the medical visit. Patients reported the time spent at the clinic, the time spent travelling to and from the clinic, and the time affected by work or social activities that were altered before and after the visit. Hospitalization for neutropenia-related complications accounted for the greatest amount of patient time, followed by a visit to the clinic to see the physician and be treated with chemotherapy. It should be noted that visits in which the procedures are relatively brief, such as laboratory visits and visits to be treated with filgrastim and pegfilgrastim, also accounted for substantial amounts of time. The values reported are for single visits, and it should also be noted that a complete course of treatment with intravenous antibiotics or filgrastim requires several visits and the total amount of time for such treatment would be much greater.

Figure 1.

Patient time affected by medical visits Patient times affected by medical visits, with the point and bar indicating the mean and standard deviation, the vertical line indicating the median, the limits of the box indicating the 25th and 75th percentiles, and the extensions indicating the range. Not all types of visits were reported at all sites (N = 20) or by all patients (N = 189).

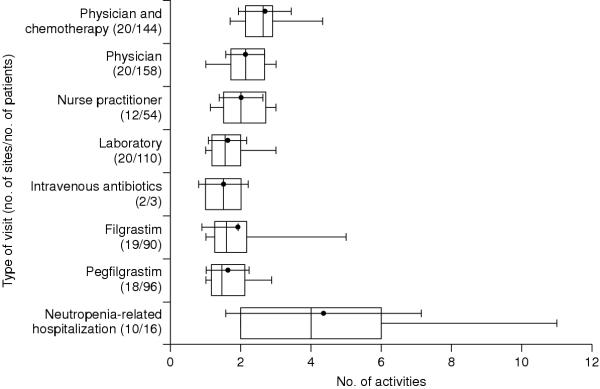

The numbers of life activities that were affected by the visits are shown in Figure 2. The activities most frequently cited by patients were work, community activities, family obligations, and daily responsibilities such as housework and family care. All visits affected at least 1 life activity. As would be expected, neutropenia-related hospitalizations and physician and chemotherapy visits affected the greatest number of life activities. And, as noted above, a course of treatment with intravenous antibiotics or filgrastim would require several visits and would thus be expected to affect a greater number of life activities.

Figure 2.

Life activities affected by medical visits Life activities affected by medical visits, with the point and bar indicating the mean and standard deviation, the vertical line indicating the median, the limits of the box indicating the 25th and 75th percentiles, and the extensions indicating the range. Not all types of activities were reported at all sites (N = 20) or by all patients (N = 189).

Discussion

This study shows that, from the point of view of the patient, there is no such thing as a short clinic visit. As expected, patient time was affected most by neutropenia-related hospitalizations, but even visits for relatively simple procedures, such as laboratory draws, take a lot of time. Clinic visits for these purposes cause patients to deviate from their normal activities and prevent them from pursuing their normal life activities.

This study looked at patient time and life activities that were affected before and after the actual visit, as well as the time of the visit itself. Lindley and colleagues also reported that patient time was affected after a visit in addition to the visit itself [12]. For example, rescheduling trips or extending work activities can result in a large amount of time being affected by medical visits. Meehan and colleagues found that the average time spent travelling to a clinic was 40 minutes [13]. The time spent travelling for treatment can be a potential barrier to patients' seeking treatment and keeping their medical appointments. Patients must have reliable transportation [14], which can be difficult if they have limited access to transportation or if long distances are involved [15,16]. Transportation can be especially problematic if the patient cannot drive, does not have a car, or uses a wheelchair [14]. Public transportation is often unreliable and time-consuming. Patients also often make alternative living arrangements so that they can have better access to a caregiver or to the clinic [14]. The effects of travelling to the clinic can be so great that impaired access to transportation may cause patients to forgo treatment [17,18].

In addition to the logistical inconveniences and economic hardships of travel [16], it can be another source of stress and can have negative psychological effects on patients [19]. This stress could even affect their willingness to undergo further treatment [12]. Worrying about going to the clinic decreases patients' energy levels and functionality for daily activities. Patients' stress, anxiety, and depression may increase, especially if they do not understand why they must visit the clinic numerous times. Managing this stress can improve patients' well-being [20].

In addition to the costs associated with travelling to the clinic [15,16], the costs associated with lost work time may be an economic burden for patients [14]. Overnight accommodations may be required, and out-of-pocket expenses can be substantial. Patients often have little or no insurance coverage for out-of-pocket or incidental expenses such as lodging, gas, and meals [14,21,22]. Meehan and colleagues reported that not only were clinic visits time-consuming and inconvenient for both patients and their caregivers, but they also generated no reimbursable costs [13]. Other studies have also found that transportation is the largest out-of-pocket expense for treatment, followed by meals [21,23].

In addition to time, each clinic visit affects several life activities, which results in patients' changing, postponing, or cancelling those activities. At least 1 life activity was affected by each type of medical visit. As expected, the medical visit that accounted for the most time, neutropenia-related hospitalization, also affected more life activities than the other types of visits.

The time that was required for a single visit for treatment with filgrastim was the same as that for a visit for treatment with pegfilgrastim, but treatment with filgrastim requires several daily visits during a cycle of chemotherapy and treatment with pegfilgrastim requires only 1 visit. If patients are given 10 daily injections of filgrastim, which may be necessary for their ANC to reach the recommended 10 × 109/L [9], the time required would be 24 hours, whereas equivalent treatment with pegfilgrastim would take less than 3 hours.

Patient care can be optimized by reducing the number of clinic visits. Nurses play a central role in minimizing the disruptions that treatment has on the lives of patients and their families and caregivers, and patients often perceive nurses as being a liaison between themselves and their physicians [5]. Nurses can educate and instruct patients on how to manage their symptoms, such as what symptoms to report and how and when to take their temperature. Implementing protocols and guidelines can improve the management of neutropenia and can help nurses conduct patient assessments more efficiently [24,25]. Telephone triage in particular can be effective, convenient, and practical, by helping determine which patients should be seen frequently and which patients can be managed by telephone [26].

The choice of the treatment can also help reduce the number of clinic visits. Moore and colleagues reported that the amount of time actually spent at the clinic may be inconsequential, because patients still have to interrupt their routines to go to the clinic [14]. The CSF used to manage neutropenia can be important and can affect the number of clinic visits and amount of patient time. Decreasing the number of clinic visits can have a positive effect on patients by improving their functional [2,3,21], social [2,21], and financial well-being [14,21,23], in addition to decreasing their emotional stress [1,14,27]. The greater convenience of fewer clinic visits could also increase patient adherence and lessen the likelihood that patients might put themselves at greater risk for neutropenia by not going to the clinic for their treatment.

Conclusions

This study provides new data on how medical visits affect patients. It is clear that treatment with chemotherapy – as well as the management of adverse events – involves a great number of medical visits and that these visits have substantial effects on patient time and activities. The study is based solely on patient self-reports, however, and the extent to which patients can accurately recall this type of information is not certain. Future studies might use other methods, such as prospective observation or patient diaries, to confirm and extend these findings.

Competing interests

This study is supported by an unrestricted grant from Amgen Inc. Davis Templeton is a consultant to Amgen Inc.

Authors' contributions

BF served as study chair and was instrumental to all aspects of the study. KT served as the principal investigator and contributed to the study concepts and interpretation. LZ conducted all data analysis. TO contributed to the core analysis design and statistical model. KM was a key project manager in executing the study. DT was a key project manager in executing the study. LS was a key contributor to the study concept and interpretation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Supplementary Material

Sample survey page. Sample page from the patient impact survey in PDF format, viewable with Adobe Reader.

Contributor Information

Barry V Fortner, Email: bfortner@sosacorn.com.

Kurt Tauer, Email: ktauer@westclinic.com.

Ling Zhu, Email: lzhu@sosacorn.com.

Theodore A Okon, Email: taokon@sosacorn.com.

Kelley Moore, Email: kmoore@sosacorn.com.

Davis Templeton, Email: dtempleton@sosacorn.com.

Lee Schwartzberg, Email: lschwartzberg@westclinic.com.

References

- Ashley J, Taylor D, Houts A, Fortner B, Durrence H. The experience of chemotherapy-induced neutropenia: quality-of-life interviews with adult cancer patients [abstract] Oncol Nurs Forum. 2003;30:120. [Google Scholar]

- Carelle N, Piotto E, Bellanger A, Germanaud J, Thuillier A, Khayat D. Changing patient perceptions of the side effects of cancer chemotherapy. Cancer. 2002;95:155–163. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cella D. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Anemia (FACT-An) Scale: a new tool for the assessment of outcomes in cancer anemia and fatigue. Semin Hematol. 1997;34:13–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curt GA, Breitbart W, Cella D, Groopman JE, Horning SJ, Itri LM, Johnson DH, Miaskowski C, Scherr SL, Portenoy RK, Vozelgang NJ. Impact of cancer-related fatigue on the lives of patients: new findings from the Fatigue Coalition. Oncologist. 2000;5:353–360. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.5-5-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houston D. Supportive therapies for cancer chemotherapy patients and the role of the oncology nurse. Cancer Nurs. 1997;20:409–413. doi: 10.1097/00002820-199712000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yellen SB, Cella DF, Webster K, Blendowski C, Kaplan E. Measuring fatigue and other anemia-related symptoms with the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) measurement system. J Pain Symptom Manage . 1997;13:63–74. doi: 10.1016/S0885-3924(96)00274-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford J, Dale DC, Lyman GH. Chemotherapy-induced neutropenia: risks, consequences, and new directions for its management. Cancer. 2004;100:228–237. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozer H, Armitage JO, Bennett CL, Crawford J, Demetri JD, Pizzo PA, Schiffer CA, Smith TJ, Somlo G, Wade JC, Wade JL, 3rd, Winn RJ, Wozniak AJ, Somerfield MR. 2000 update of recommendations for the use of hematopoietic colony-stimulating factors: evidence-based, clinical practice guidelines. American Society of Clinical Oncology Growth Factors Expert Panel. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:3558–3585. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.20.3558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neupogen (filgrastim) prescribing information. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Amgen; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Neulasta (pegfilgrastim) prescribing information. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Amgen; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Green MD, Koelbl H, Baselga J, Galid A, Guillem V, Gascon P, Siena S, Lalisang RI, Samonigg H, Clemens MR, Zani V, Liang BC, Renwick J, Piccart M. A randomized double-blind multicenter phase III study of fixed-dose single-administration pegfilgrastim versus daily filgrastim in patients receiving myelosuppressive chemotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:29–35. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindley C, Vasa S, Sawyer WT, Winer EP. Quality of life and preferences for treatment following systemic adjuvant therapy for early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:1380–1387. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.4.1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meehan K, Tchekmedyian S, Ciesla G, Kallich J, Erder MH, Smith R. The burden of weekly epoetin alfa injections to patients and their caregivers [abstract] Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2003;22:543. [Google Scholar]

- Moore K, Fortner B, Okon T. The impact of medical visits on patients with cancer [abstract] Oncol Nurs Forum. 2003;30:128. [Google Scholar]

- Hinds G, Moyer A. Support as experienced by patients with cancer during radiotherapy treatments. J Adv Nurs. 1997;26:371–379. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.1997026371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junor EJ, Macbeth FR, Barrett A. An audit of travel and waiting times for outpatient radiotherapy. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 1992;4:174–176. doi: 10.1016/s0936-6555(05)81082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin JS, Hunt WC, Samet JM. Determinants of cancer therapy in elderly patients. Cancer. 1993;72:594–601. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930715)72:2<594::aid-cncr2820720243>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidry JJ, Aday LA, Zhang D, Winn RJ. Transportation as a barrier to cancer treatment. Cancer Practice. 1997;5:361–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne S, Jarrett N, Jeffs D. The impact of travel on cancer patients' experiences of treatment: a literature review. Eur J Cancer Care. 2000;9:197–203. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2354.2000.00225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen PB, Meade CD, Stein KD, Chirikos TN, Small BJ, Ruckdeschel JC. Efficacy and costs of two forms of stress management training for cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2851–2862. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.08.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore KA. Breast cancer patients' out-of-pocket expenses. Cancer Nurs. 1999;22:389–396. doi: 10.1097/00002820-199910000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce S, Kelly D, Stevens W. 'More than just money' – widening the understanding of the costs involved in cancer care. J Adv Nurs . 2001;33:371–379. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houts PS, Lipton A, Harvey HA, Martin B, Simmonds MA, Dixon RH, Longo S, Andrews T, Gordon RA, Meloy J. Nonmedical costs to patients and their families associated with outpatient chemotherapy. Cancer. 1984;53:2388–2392. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19840601)53:11<2388::aid-cncr2820531103>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glynn-Tucker EM. A multidisciplinary performance improvement project for the management of febrile neutropenia [abstract] Oncol Nurs Forum. 2002;29:354. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell C, Winkler L, Lottenberg M. Nurse driven neutropenia management guidelines: improving patient outcomes through evidence-based practice [abstract] Oncol Nurs Forum. 2002;29:371. [Google Scholar]

- Anastasia PJ, Blevins MC. Outpatient chemotherapy: telephone triage for symptom management. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1997;24:13–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallich JD, Tchekmedyian NS, Damiano AM, Shi J, Black JT, Erder MH. Psychological outcomes associated with anemia-related fatigue in cancer patients. Oncology (Huntingt) 2002;16:117–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Sample survey page. Sample page from the patient impact survey in PDF format, viewable with Adobe Reader.