Abstract

Introduction

As states make home- and community-based services (HCBS) more accessible, researchers have become more interested in understanding service use and spending. Because state Medicaid programs differ in the types of services they offer and in how they report these services, analyzing HCBS at the national level is challenging.

Objective

Describe the HCBS taxonomy and present findings on HCBS waiver expenditures and users.

Data

This brief analyzed fee-for-service claims from 28 approved states in 2010 Medicaid Analytic eXtract (MAX) files. We summed all expenditures and counted the unique number of users across each HCBS taxonomy service and category.

Methods

The taxonomy was developed jointly by Truven Health (at that time Thomson Reuters) and Mathematica Policy Research, with stakeholder input, and reviewed using procedure codes. Today, the taxonomy is organized by 18 categories and over 60 specific services.

Findings

For calendar year 2010, 28 states spent almost $23.6 billion on HCBS, with 80 percent of expenditures categorized as round-the-clock, home-based, and day services. Other services, such as case management, or equipment, modifications, and technology were widely used, but are not particularly costly and do not account for a large proportion of expenditures in every state.

Conclusions

By providing a common language, the taxonomy presents detailed information on services and makes it easier to assess and identify state-level variation for HCBS.

Keywords: Long Term Care, home care, nursing homes, Medicaid, administrative data uses

Introduction

Medicaid expenditures for long-term care services have gradually shifted from institutional-based care to home- and community-based care (Kaye, 2012; LaPlante, 2013; Eiken et al., 2011). Between 1997 and 2009, the share of Medicaid long-term care spending devoted to home-and community based services (HCBS) increased from 24 percent to 44 percent. In fiscal year 2009, Medicaid spending on HCBS reached over $55 billion and accounted for 15 percent of all Medicaid expenditures (Eiken et al., 2011). Section 1915(c) waivers (HCBS waivers), authorized in 1981, were among the first efforts by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to encourage states to provide optional HCBS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2000; Ng, Harrington, & O’Malley, 2009). By 2010, every state except Arizona and Vermont had implemented at least one HCBS waiver to provide more options for community-based long term care services. These waivers cover a variety of services, including residential services, home-based services, day services, case management, provision of equipment, respite care, and transportation (Borck et al., 2012; Shirk, 2006; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2000). Recent federal and state Medicaid policies, including the Money Follows the Person Demonstration (MFP) and the Balancing Incentive Program, were implemented to help states rebalance their long-term care systems and to reduce their dependence on institutional care. This larger policy focus on HCBS has led to increased interest in studying HCBS, both to better understand the quality of long-term services and supports (LTSS) being offered by states and to determine which approaches will help frail or disabled Medicaid enrollees live independently (Grabowski, 2006).

Until recently, studying HCBS expenditures and utilization was a challenging task, mainly because state control and reporting of HCBS made it difficult to determine exactly which services were being offered by which states (Rizzolo, Friedman, Lulinkski-Norris, & Braddock, 2013). States—not CMS—determine which types of LTSS are covered under waivers and state plan amendments; different states offer different services, and some states may offer certain LTSS only to specific populations. Moreover, information available through claims data may not always offer the detail researchers need. According to administrative billing claims, most HCBS waivers report the type of service as “other” (as opposed to private duty nursing or personal care, for example). This lack of specificity makes it impossible to distinguish individual waiver services. Nor can researchers seeking to identify and assess HCBS by type of service rely on the procedure codes that appear on claims records, since states vary significantly in how they define specific services. For example, “personal care” may also be labeled “attendant care,” “personal assistance,” or “personal attendant services.” Some states use national codes for personal care, and some create unique state-specific codes. What researchers needed was a taxonomy for procedure codes that made it possible to categorize waiver claims and understand services offered, including services indicated by state-specific procedure codes that did not supply a description.1

To fill this need and ensure that CMS could monitor the wide range of waivers and waiver services used by states, Truven Health Analytics, formerly known as Thomson Reuters, led the development of an HCBS taxonomy. Today, the taxonomy applies to services covered under HCBS waivers, as well as the State Plan HCBS benefits authorized by Section 1915(i). The utility of the taxonomy is that researchers can analyze HCBS use at the person-level, where other sources of HCBS analysis, based on information as CMS Form 372 or Form 64, were always at the aggregate level. Below, we describe the HCBS taxonomy, explain the construction of a crosswalk to map claims to taxonomy categories, and then present descriptive, exploratory, statistics on state-, service-, and person-level HCBS expenditures based on 28 states whose 2010 MAX data files had been approved by June 1, 2013 to showcase the application of the taxonomy.

Data

Our analysis used data available in Medicaid Analytic eXtract (MAX) 2010 files. MAX files are research-friendly Medicaid administrative files with information on Medicaid eligibility, service use, and payments (CMS, 2013). In order to capture corrections and adjustments for enrollment and claims records, as well as lagged claims, MAX collects three extra quarters of data beyond the calendar year. Adjustment business rules are applied to create final enrollment and claims records (Borck et al., 2012). We used data from 2010 because this is the most recent year for which MAX data are available and because 2010 was the first year that MAX included the HCBS taxonomy. Within the MAX Other Services (OT) file, which contains claim records for ambulatory services delivered and paid for by Medicaid (such as office-based physician services, lab/X-ray, clinic services, hospice, and outpatient hospital institutional claims), we identified all HCBS fee-for-service waiver service claims submitted by states and approved by CMS as of June 1, 2013. By that date, 32 states had approved 2010 MAX files. Of these, we excluded four—Michigan,2 Oregon,3 South Dakota,4 and Virginia5—because of data quality issues, limiting our analysis to 28 states.6 After linking all HCBS claims to the MAX Person Summary file, which includes monthly enrollment information and summary expenditure information, we excluded users and their associated claims if the enrollee’s Medicaid eligibility information was missing or if the enrollee was eligible only for a state’s separate Children’s Health Insurance Program. The latter group was excluded because their claims data are incomplete.

Methods

HCBS Taxonomy—Development and Application

The methods used to develop the taxonomy are described in detail elsewhere (Eiken, 2012 & Tribe, 2012). To paraphrase, in 2009, Truven Health (at that time Thomson Reuters) drafted the first version of the HCBS taxonomy, using literature reviews, expert interviews, and an analysis of service definition information provided by 159 HCBS waivers in the online Waiver Management System using the qualitative software program, NVivo. This draft taxonomy was tested by a working group of state associations, piloted using staff from 10 states and one Area Agency on Aging, and reviewed using the procedure codes submitted in Medicaid Statistical Information System (MSIS) 2008 claims records. MSIS files contain eligibility and claims records for Medicaid recipients, and they are the data source for the more research-friendly MAX files. A team from Mathematica Policy Research conducted the MSIS pilot test by applying taxonomy categories to Medicaid claims data and providing feedback to Truven. Mathematica and Truven then submitted a joint revised version two of the taxonomy to CMS in April 2011. Later revisions reflected additional feedback from CMS, state associations, and a 2012 pilot among states.

As part of the pilot, Mathematica developed an initial crosswalk between information on claims and the list of services included in the taxonomy developed by Truven (Wenzlow, Peebles, & Kuncaitis, 2011). The crosswalk mapped national Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) procedure codes, Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) procedure codes, and state-specific procedure codes to HCBS taxonomy services. Procedure code modifiers, place-of-service codes, and MAX type-of-service codes were also considered in order to extract additional detail about the services provided in the claims,7, 8 and thus, to categorize services more precisely. For example, place of service can help distinguish between the taxonomy services “respite, in-home” and “respite, out-of-home.” In cases where we could not fully differentiate the place of service, claims were mapped to a “respite unspecified” code. During the pilot, Mathematica staff also consulted with state staff to gather additional information on codes that represented a substantial percentage of waiver expenditures.

As we updated our crosswalk for MAX 2010, we consulted our past documentation from state contacts, sought additional input from states, and searched Internet sources for more information. For example, we were able to find a list of definitions of codes of home health rates used by New York that helped us identify certain state-specific code descriptions.9 The data collection process was comprehensive and unbiased to the extent possible. For all states, we used the same data sources (MSIS documentation and MAX data). Other data sources (state Medicaid Web sites and contacts) were only used when we found anomalies. Updating the taxonomy crosswalk is a continuously evolving process as each year states add new codes and services, and the meaning of codes change over time. The taxonomy crosswalk used for 2010 is based on the procedure codes present in 2010 claims data and should only be used for 2010 data. As the taxonomy crosswalk is applied to more recent claims files, the information on the claims should be reviewed in order to accurately map services.

The taxonomy categories and services were then applied to MAX claims data through an automated program, and the results were reviewed again for quality assurance. The HCBS taxonomy was applied to all HCBS fee-for-service waiver claims in the MAX OT file. Exhibit 1 shows how the taxonomy is organized by 18 categories, including an “unknown” category, and over 60 specific services. The ordering of the categories and services in Exhibit 1 reflects the order in which the crosswalk is applied in practice. If a service could be placed in either of two categories, the taxonomy was designed to assign the category that comes first in the taxonomy, which is helpful for a situation when a service may be classified into more than one category. For example, the national HCPCS code H0032, “mental health service plan development by non-physician,” could either be classified as case management or other mental health and behavioral services. Because case management is ordered first in the taxonomy, the procedure code is mapped to this category.

Exhibit 1.

HCBS Taxonomy Categories and Services

| HCBS Taxonomy Category | HCBS Taxonomy Service |

|---|---|

| Case management | Case management |

| Round-the-clock services | Group living, residential habilitation Group living, mental health services Group living, other Shared living, residential habilitation Shared living, mental health services Shared living, other |

| Round-the-clock services (cont.) | In-home residential habilitation In-home round-the-clock mental health services In-home round-the-clock services, other |

| Supported employment | Job development Ongoing supported employment, individual Ongoing supported employment, group Career planning |

| Day services | Prevocational services Day habilitation Education services Day treatment/ partial hospitalization Adult day health Adult day services (social model) Community integration Medical day care for children |

| Nursing | Private duty nursing Skilled nursing |

| Home-delivered meals | Home delivered meals |

| Rent and food expenses for live-in caregiver | Rent and food expenses for live-in caregiver |

| Home-based services | Home-based habilitation Home health aide Personal care Companion Homemaker Chore |

| Caregiver support | Respite, out-of-home Respite, in-home Caregiver counseling and/or training |

| Other mental health and behavioral services | Mental health assessment Assertive community treatment Crisis intervention Behavior support Peer specialist Counseling Psychosocial rehabilitation Clinic services Other mental health and behavioral services |

| Other health and therapeutic services | Health monitoring Health assessment Medication assessment and/or management Nutrition consultation Physician services Prescription drugs Dental services Occupational therapy |

| Other health and therapeutic services (cont.) | Physical therapy Speech, hearing, and language therapy Respiratory therapy Cognitive rehabilitative therapy Other therapies |

| Services supporting participant direction | Financial management services in support of participant direction Information and assistance in support of participant direction |

| Participant training | Participant training |

| Equipment, technology, and modifications | Personal emergency response system Home and/or vehicle accessibility adaptations Equipment and technology Supplies |

| Nonmedical transportation | Nonmedical transportation |

| Community transition services | Community transition services |

| Other services | Goods and servicesInterpreter Housing consultationOther |

| Unknown | Unknown |

SOURCE: Truven Health Analytics/Mathematica Policy Research, 2012.

The services within a category provide more distinctive classifications; for example, the “supported employment” category is broken out into “job development,” “ongoing supported employment—individual,” “ongoing supported employment—group,” and “career planning.” If we were unable to determine whether an “ongoing supported employment” claim should be mapped to “group” or “individual,” the claim was mapped to “ongoing supported employment—unspecified.”

Approach

To quantify the utility of the taxonomy, we analyzed the proportion of claims mapped to the “unknown” taxonomy category compared to claims originally mapped to the “unknown” or “other” type of service in MAX. To summarize expenditures, we reviewed claims data for each of the 28 approved states in MAX with applicable data. We summed all expenditures for HCBS waiver recipients and counted the unique number of users across each HCBS taxonomy service and category. HCBS waiver services were identified as claims having a program type equal to 6 (home- and community-based care for disabled elderly and individuals age 65 and older) or 7 (home- and community-based care waiver services).10 Average amount paid per user was calculated by dividing the sum of all expenditures for a particular service by the number of unique users with a claim for that service. We reported use of services by category (see Exhibit 2) and defined expenditures using the Medicaid paid amount. Our analyses focused on the HCBS categories that account for the largest proportion of expenditures, both overall and per user. We calculated per-user expenditures by state to assess the variability in state waiver service offerings; heterogeneity is expected, because waivers must meet the needs of enrollees, and states vary in how they administer certain services (for example, some states use state administrative funds, which are not collected in MSIS, for case management). We also compared per-person expenditures to other information sources to assess the validity of our information.

Exhibit 2. Use of- and Expenditures for- Services, by HCBS Category.

| Category | Number of States Reporting | Total Expenditures (in Millions) | Percentage of Expenditures | Number of Users | Percentage of Users | Average Paid perUser |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 28 | 23,595.7 | 100 | 850,123 | >100 | $27,755 |

| Case management | 27 | 953.4 | 4 | 377,272 | 44 | $2,527 |

| Round-the-clock services | 27 | 10,758.2 | 46 | 198,734 | 23 | $54,134 |

| Supported employment | 24 | 321.3 | 1 | 41,463 | 5 | $7,749 |

| Day services | 27 | 3,3561.9 | 15 | 233,226 | 27 | $15,272 |

| Nursing | 23 | 260.0 | 1 | 50,127 | 6 | $5,186 |

| Home-delivered meals | 22 | 119.1 | 1 | 95,997 | 11 | $1,241 |

| Rent and food for live-in caregiver | 1 | 0.2 | <1 | NR | NR | NR |

| Home-based services | 28 | 4,331.0 | 18 | 355,118 | 42 | $12,196 |

| Caregiver support | 27 | 519.5 | 2 | 125,994 | 15 | $4,124 |

| Other mental health | 25 | 807.6 | 3 | 95,569 | 11 | $8,451 |

| Other health and therapeutic services | 25 | 118.8 | 1 | 74,425 | 9 | $1,596 |

| Services supporting participant direction | 9 | 161.2 | 1 | 31,808 | 4 | $5,066 |

| Participant training | 16 | 389.1 | 2 | 38,952 | 5 | — |

| Equipment, technology, and modifications | 28 | 208.2 | 1 | 234,566 | 28 | — |

| Nonmedical transportation | 24 | 265.8 | 1 | 125,643 | 15 | — |

| Community transition services | 12 | 4.1 | <1 | 3,011 | — | — |

| Other | 14 | 110.4 | 1 | 22,868 | 3 | — |

| Unknown | 25 | 705.8 | 3 | 93,543 | 11 | — |

NOTES: Number of users and average paid per user were not reported for the HCBS taxonomy category “rent and food for live-in caregiver” due to small sample sizes. The percentage of users equals the number of users reporting a claim in each category divided by the total number of HCBS waiver users. Waiver participants use more than one category of HCBS, therefore, the total percentage of users is greater than 100.

NR = not reported.

SOURCE: Analysis of MAX data for 28 states approved as of June 1, 2013, for services provided in calendar year 2010.

Findings

Application of the Taxonomy

For calendar year 2010, the 28 states included in our analysis spent almost $23.6 billion on HCBS for people in waiver programs. These numbers are comparable with preliminary calculations of fiscal year 2010 waiver expenditures—$24.2 billion—reported by Truven Health for the same set of states using CMS 64 (Eiken et al., 2011). We mapped 97 percent of HCBS waiver expenditures to an HCBS taxonomy category. The remaining 3 percent of expenditures were mapped to the “unknown” category, primarily because the procedure code on the claims could not be interpreted—most commonly because it was an unknown state-specific procedure code that was missing a description, or it was the national HCPCS code T2025, “waiver services; not otherwise specified.” Had we relied solely on the MSIS type-of-service field, we would have categorized only 20 percent of claims. MAX type-of-service categories expand those in MSIS to include adult day care, residential care, and durable medical equipment, and they allowed us to classify an additional 51 percent of the claims in our data set (data not shown). Applying the HCBS taxonomy increased the percentage of categorized claims from 71 to 97 percent of HCBS waiver claims.

Use of HCBS

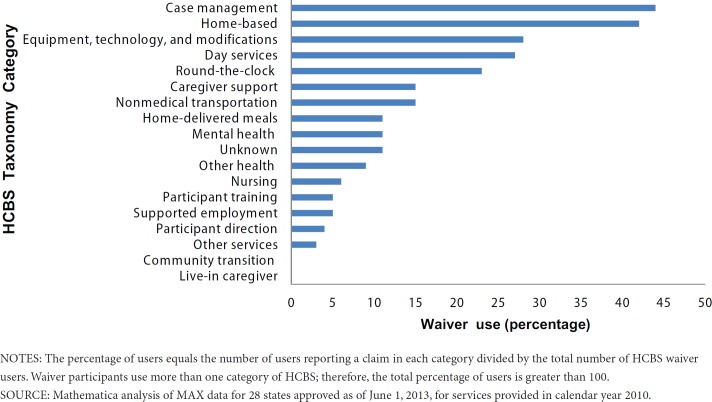

Based on the more than 850,000 users of HCBS waiver services across the 28 states, we find that no one type of HCBS was used by the majority of Medicaid waiver participants. Case management was the most commonly used taxonomy category, with 44 percent of all waiver service users receiving case management services (Exhibit 3). Home-based services—which include home health aides, personal care, homemaker, and chore services (see Exhibit 1)—were used by 42 percent of wavier service users. Services under the equipment, technology, and modifications category were provided to 28 percent of waiver service users. Few people utilized services that support rent and food expenses for live-in caregivers, community transitions, or participant direction. In fact, only one state had claims for the costs of food and rent for live-in caregivers, and only five total users received this service. This is an example of a category that may make sense to group with other taxonomy categories in the future, because claims data does not support the level of detail needed to differentiate this service. The overall lack of a dominant service category suggests that the HCBS users have a wide variety of care needs, although service use is also influenced by state policies and waiver type.

Exhibit 3. Waiver Use, by HCBS Taxonomy Category (Percentage).

HCBS Waiver Expenditures

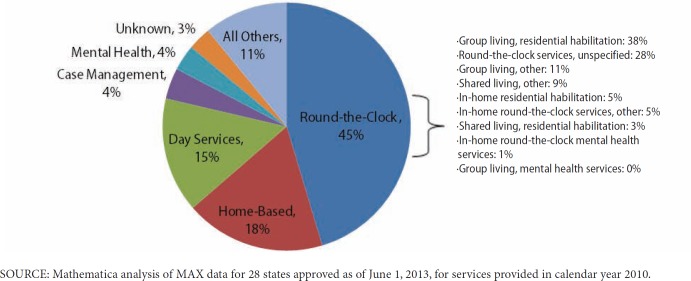

Although people who need LTSS use a variety of services, and no single service dominates, a few select services appear to drive overall HCBS expenditures. Out of the nearly $23.6 billion spent on HCBS waivers, 3 of the 18 HCBS categories— round-the-clock, home-based, and day services—accounted for nearly 80 percent of all waiver expenditures (Exhibit 4). The largest HCBS expenditure category was round-the-clock services, which accounted for 46 percent of total HCBS waiver expenditures, or $10.7 billion.11 Only 23 percent of users received this service (Exhibit 3), which suggests a high per-user cost for this service category. Round-the-clock services included “group living,” “shared living,” and “in-home residential habilitation.” Almost 40 percent of the expenditures for round-the-clock services were for “group living, residential habilitation,” and almost 90 percent of this spending occurred in Individual Residential Alternative settings in New York. Another 28 percent of the $10.7 billion was accounted for by “round-the-clock services, unspecified.” Unspecified categories are used in the taxonomy when more specific services, or subcategories, cannot be applied. For example, the national HCPCS code T2033—“residential care, not otherwise specified, waiver; per diem”—denotes a round-the-clock service, but a more specific distinction cannot be made. “Group living, other,” and “shared living, other” each represent about 10 percent of overall round-the-clock spending. The remaining round-the-clock categories, such as “in-home residential habilitation,” account for smaller shares of total expenditures for round-the-clock services.

Exhibit 4. HCBS Waiver Expenditures, by Taxonomy Category (Percentage).

Home-based services, the second largest category of spending, accounted for 18 percent of HCBS expenditures. Unlike round-the- clock services, home-based services were widely used by 42 percent of waiver service users. Day services, which include adult day health and day habilitation, made up 15 percent of total HCBS expenditures, and more than a quarter of waiver service users received this service.

The data indicate that some services, such as round-the-clock, account for a large share of total HCBS expenditures, but are not widely used while other services are widely used but account for a small share of total expenditures. Case management is an example of the latter. Although 44 percent of waiver service users received this service, it accounted for only 4 percent of total HCBS expenditures in 2010. The equipment, technology, and modifications service category is another example of a widely used service (utilized by 28 percent of waiver service users) that accounts for only a small fraction of HCBS expenditures, in this case less than 1 percent of expenditures.

Per-User Expenditures

Per-user expenditures help us assess the amount Medicaid paid for HCBS provided to waiver service users on average; they also show the variations in state waiver programs and the populations they serve. In 2010, the 28 states in the study provided an average of $27,755 in HCBS on a per-user basis. This average is consistent with reports from 2008 (Borck et al., 2012), when expenditures for HCBS provided through waivers were about $21,000 per waiver enrollee (this calculation includes all enrolled individuals, even those who did not use any waiver services). This average is also consistent with per-person estimates for waiver participants of $24,675 in 2009 done by Kaiser (this calculation is based on analysis of CMS Form 372 data, which states complete on aggregate expenditure data by target group; Ng et al., 2009).

An analysis of HCBS users with similar grantee data in the MFP program showed considerably higher per-person spending—over $37,000 in 2012 (Irvin, 2013). MFP per-person expenditures vary from our estimates for a number of reasons. First, the MFP figures are based on a different mix of states, and they are calculated by dividing MFP programs’ total HCBS expenditures by the total number of MFP participants, adjusted for the number of days that a participant was enrolled in the program. Our data divides total expenditures by the total number of users with an HCBS claim, but does not account for the duration of waiver enrollment; accounting for duration would increase annual per enrollee expenditures because not all individuals had a full year of enrollment; however, duration information was not available. Second, the characteristics of these two populations may differ. MFP participants are more likely to be younger and have physical disabilities than the general HCBS user population. Participants in MFP have recently transitioned from an institution to a community setting and may have had above-average needs for HCBS, whereas HCBS waiver enrollees may have been living in the community for several years and have different care needs. The MFP evaluation compared per-person- per-month costs for the first 30 days to overall costs and found that monthly service expenditures during the 30 days after the initial transition are, on average, more than 54 percent higher than those for the remainder of the year (Irvin, 2013); this difference reflects the one-time services participants receive when transitioning to community living. Finally, the MFP program provides additional HCBS that would not be available to regular Medicaid beneficiaries, such as extra hours of personal assistance services (Irvin, 2013).

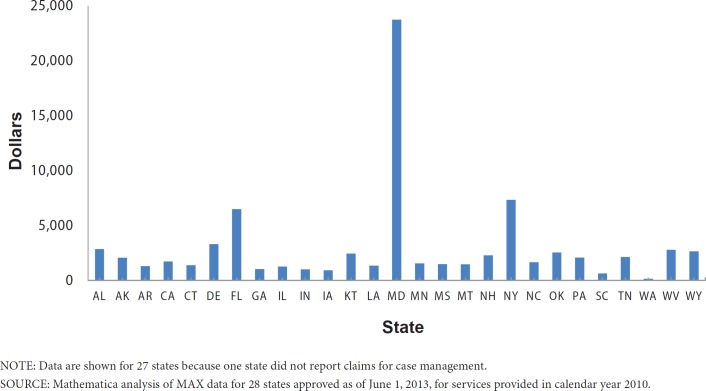

Per-user expenditures varied considerably across the 28 states, from a low of $8,200 to over $75,000 (data not shown). The average expenditures per user also varied across the different HCBS taxonomy categories, from a low of almost $900 for equipment, technology, and modifications to over $50,000 for round-the-clock services (Exhibit 2). The number of waiver participants varied across states, and knowing the average paid per user can help researchers spot state-specific data anomalies. For example, the average per-user amount paid for case management services is typically around $2,000 (Exhibit 5), but Maryland’s $24,000 per user amount paid stands out. Further investigation revealed that Maryland claims are allocated to a service described as “coordinated care fee, risk-adjusted maintenance.” This description suggests a Medicaid managed care service that should be excluded from analysis, but the information on the claim indicated fee-for-service. When noting these anomalies, researchers should use caution and consider looking into individual states’ waiver applications to learn more about what the state program covers, because each waiver is unique even when compared to waivers of the same type in different states (for example, waivers for older adults or persons with physical disabilities). In the case of spending on case management services, the anomaly may represent the actual per-user spending in the state—that is, it may show that the state’s case management services are more extensive than those of other states and the issue warrants further research; alternatively, the figure may be a data anomaly that warrants excluding the state from analysis.

Exhibit 5. Case Management Services: Average HCBS Waiver Amount Paid per User, by State.

State-Specific Findings

The analyses presented in this brief are most likely sensitive to the states included. The overall expenditure and user estimates are heavily influenced by the states with the largest number of users. A few states make up a disproportionately large share of total waiver expenditures in our findings. Out of the $23.6 billion reported across the 28 states in our data set, the state of New York accounted for 24 percent of overall expenditures (data not shown). Other states with large shares of total expenditures included Pennsylvania (10 percent), California (9 percent), and Minnesota (7 percent). Based on other published reports of national HCBS expenditures, New York is consistently the state with the largest share of expenditures (Eiken et al., 2011).

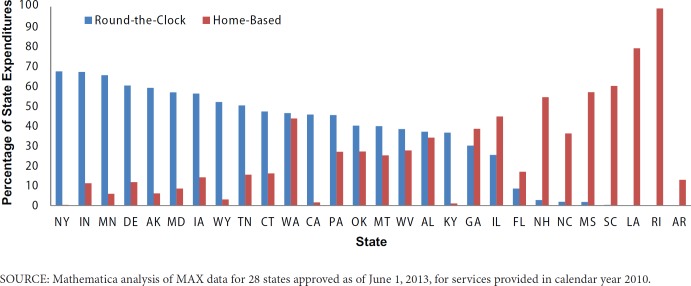

As was true for overall HCBS expenditures, most HCBS expenditures at the state level were accounted for by round-the-clock, home-based, and day services. Almost all states fell into one of two groups—those that spent most on round-the-clock services and those that spent most on home-based services. Round-the-clock services were the largest share of HCBS waiver expenditures in 18 of the 28 states studied; expenditures among those 18 states for these services ranged from 37 to 67 percent of the states’ total expenditures for waiver services (Exhibit 6). In contrast, home-based services were the largest share of HCBS waiver expenditures in eight states. In the remaining two states (Arkansas and Florida), other mental health services and case management were the largest share of HCBS expenditures (data not shown).

Exhibit 6. Percentage of Expenditures for Round-the-Clock and Home-Based Services, by State.

Most Common Categories of HCBS Provided by States

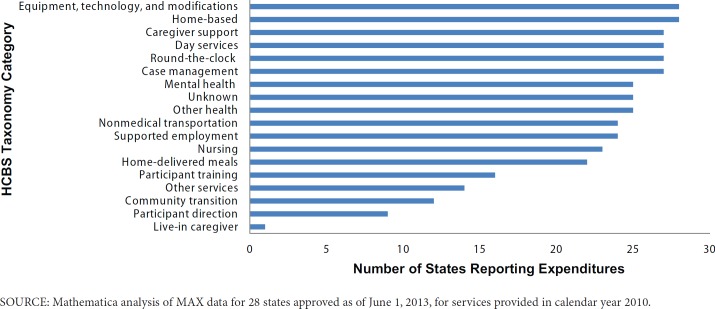

A number of services were provided by most or all states. In all 28 states, at least some waiver participants received equipment, technology, and modifications—a category that includes personal emergency response systems, home and vehicle accessibility adaptations, and supplies—as well as home-based services (Exhibit 7). All but one state reported waiver claims for caregiver support, day, round-the-clock, and case management services. Some services, including live-in caregiver, community transition, and supports for participant direction, were not commonly observed among states; it is possible that these services are more difficult to identify in claims records because they may be bundled with other services. Services supporting participant direction included only services that help participants manage self-directed services, such as financial management or training to manage self-directed services. Live-in caregiver services include only payments for rent and food for direct support workers and do not include payment for the direct support worker’s actual services, which would be covered under personal care. There are no national HCPCS or CPT codes to identify services that support participant direction or live-in caregiver services. There is a national code T2038, which specifies “community transition, waiver; per service, for community transition services,” but less than half of the states in our data set used this code.

Exhibit 7. Number of States Reporting Waiver Claims for Each HCBS Taxonomy Category.

Limitations

Because this brief analyzes only 28 states, we are careful not to present our findings as representative of the national HCBS landscape. Our caution is especially warranted because the findings are dominated by expenditures in a few states and because waiver services are only a part of the overall Medicaid HCBS landscape, which includes HCBS provided as a State Plan service and available to all Medicaid enrollees who may need them.

Our ability to differentiate taxonomy services varied greatly across the states because of variation in the quality of state reporting. Differentiating services across states was difficult when states used inconsistent terminology or state-specific procedure codes. We discovered that Pennsylvania replaced one or more of its information systems in 2009 or 2010, which caused changes in its state-specific service code definitions. We were able to obtain updated definitions for Pennsylvania, but other states may have implemented similar changes without our having detected them, and the taxonomy may have misclassified certain codes. The taxonomy crosswalk developed for this analysis should only be used for 2010 and should be updated if used for any other time period. At the same time, the state-specific procedure codes are not without their advantages; many of the descriptions contained detail not present in the national codes, which enhanced our ability to map claims to taxonomy services. Washington, for example, used state-specific procedure codes that usually indicated place of service.

One HCBS category that was difficult to identify in claims data was rent and food expenses for live-in caregivers. Only one state reported expenditures that were mapped to this category and for only five users in the state. This category includes only payments for rent and food for direct support workers; payment for the actual services of the direct support worker would be covered under personal care. Further research would be required to understand whether this service is offered infrequently by the particular states in our analysis or whether these services are frequently bundled with personal care services in these states and were, therefore, captured in the home-based services category.

It is unclear whether state-level variation in spending is accurate or is a symptom of a data anomaly. For example, in most states (13 out of the 16 states reporting expenditures for participant training), expenditures accounted for 2 percent or less of total HCBS expenditures in the state, but in 3 states this category accounted for over 10 percent of total expenditures (data not shown). It is also unclear whether these 3 states actually spent more on this service or whether this service was under-identified in other states or masked by a data anomaly. Lastly, our findings rely solely on services reported via claims data. Some services, such as case management, may be paid out of a state’s administrative funds, which are not collected in our dataset. Thus, our findings may be underreporting the number of total users and expenditures.

Conclusions

The HCBS taxonomy has started to provide more detailed information on what home- and community-based services entail, which services are widely used, and which services drive overall expenditures. Among the 28 states in our analysis, nearly 80 percent of the total $23.6 billion spent on HCBS waiver services was for round-the-clock, home-based, and day services. Case management, along with equipment, modifications, and technology, were widely used services, but they are not particularly costly and do not account for a large proportion of expenditures in every state. On the other hand, some services, such as round-the-clock, are used by only a small proportion of waiver service users but account for a disproportionate share of total HCBS expenditures because of their high per-user costs (over $54,000 per user in the case of round-the-clock services).

The taxonomy makes it easier to assess and identify state-level variation for HCBS. Although it is unclear whether variation represents differences in the prices states pay for a service, differences in how states define a specific service, or differences in how states report on services, the finer detail provided by the taxonomy helps to pinpoint and explain the variation. The taxonomy also allows researchers to ask research questions that could not be answered previously. For example, the taxonomy can help to answer whether the variations in spending on HCBS categories (for example, day services, group living, or mental health services) are driven by state policy or the needs of Medicaid enrollees. The key advantage of the taxonomy is that it can summarize service use and expenditures for Medicaid enrollee-level analyses. Researchers are already using the taxonomy to answer specific research questions and further investigate the use of HCBS. One study used the taxonomy to compare personal care assistance services across states and to look at how accessible those services are when they are offered as a State Plan optional service (Ruttner & Irvin, 2013). Having an existing crosswalk made it easy for that study to identify personal assistance services through both national and state-specific procedure codes. The MFP demonstration also used the taxonomy in a slightly modified form to allocate MFP financed services to taxonomy categories (Irvin, 2013).

As CMS implements the HCBS taxonomy in other Medicaid systems, we expect to see improved reporting of HCBS and increased standardization of service definitions across states. Once the HCBS taxonomy is implemented in the new expanded version of MSIS, known as the Transformed Medicaid Statistical Information System (T-MSIS), states will take over responsibility of mapping services to taxonomy categories, thereby replacing the MAX crosswalk. Because state staff is more familiar with the types of services offered and how they are reported, we expect the implementation of the taxonomy in T-MSIS to result in more reliable information. The current taxonomy crosswalk is based almost exclusively on the minimal information available through claims data, which are often incomplete. Outside of claims data, the taxonomy seeks to facilitate a common language across other Medicaid business operations. CMS intends to integrate the HCBS taxonomy into its electronic system for HCBS waiver applications in the future. Once it has done so, waiver applications, claims data, and waiver expenditures will more consistently identify HCBS.

Disclaimer

The contents of this brief were released within an issue brief completed under Task VII of contract number HHSM-500-2005-00025I, Task Order HHSM-500-T0002—Recovery Comparative Effectiveness Research Data Infrastructure Medicaid Analytic eXtract Production, Enhancement and Data Quality (MAX-PDQ). The related issue brief is available here: http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Computer-Data-and-Systems/MedicaidDataSourcesGenInfo/MAXGeneralInformation.html. The views contained within this data brief are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of MMRR, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, or the Department of Health & Human Services.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to thank Julie Sykes and Carol Irvin for providing helpful comments. We also wish to thank Cara Petroski in the Office of Information Products and Data Analytics, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, for her commitment to the development and continual improvement of MAX for Medicaid research.

Footnotes

States also submit CMS 64 reports to CMS; these provide expenditure data for HCBS waivers by state, but do not include information about the number of recipients served.

In Michigan, 75 percent of HCBS waiver claims were reported as managed care, but our study focused on HCBS provided by fee-for-service payments.

Oregon reported state-specific codes, and almost 60 percent of these codes did not have descriptions available and could not be classified.

South Dakota did not report procedure codes for over 99 percent of HCBS waiver claims, and we classified these services as unknown.

Virginia reported nonwaiver services as waiver claims; therefore, waiver claims could not be uniquely identified.

Given the variation within our sample, it is likely that our results are not generalizable to states outside of our sample, including Ohio, Texas, and Oregon, which report waiver expenditures.

The MSIS and MAX type-of-service codes are usually the same except for four special MAX type-of-service categories: durable medical equipment and supplies, residential care, psychiatric services, and adult day services.

Type-of-service is used to classify claims into approximately 30 service types in MSIS and MAX. Procedure codes refer to a more detailed classification according to national or state-specific classification systems.

These health home rate code definitions are available at http://www.health.ny.gov/health_care/medicaid/program/medicaid_health_homes/docs/rate_code_definitions.pdf

States did not always differentiate between the two programs, so we identified waiver claims by either code.

Round-the-clock services are “services by a provider that has round-the-clock responsibility for the health and welfare of residents, except during the time other services are furnished” (Truven Health Analytics/Mathematica Policy Research, 2012).

References

- Borck R, Dodd AH, Zlatinov A, Verghese S, Malsberger R, Petroski C. The Medicaid Analytic eXtract 2008 Chartbook. Washington, DC: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- CMS (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services) Medicaid Analytic eXtract (MAX) General Information. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Computer-Data-and-Systems/MedicaidDataSourcesGenInfo/MAXGeneralInformation.html.

- Eiken S. HCBS Taxonomy Development. NASUAD HCBS Conference. 20122012 Retrieved from http://www.nasuad.org/documentation/hcbs_2012/HCBS%202012%20Presentations1/HCBS%202012%20Presentations1/Thursday/1130/Potomac%202/2012HCBSTaxonomyConfSlides.pdf.

- Eiken S, Sredl K, Burwell B, Gold L. Medicaid Expenditures for Long-Term Services and Supports: 2011 Update. Cambridge, MA: Thomson Reuters; 2011. Oct, [Google Scholar]

- Grabowski DC. The Cost-Effectiveness of Noninstitutional Long-Term Care Services: Review and Synthesis of the Most Recent Evidence. Medical Care Research and Review. 2006;63(1):3–28. doi: 10.1177/1077558705283120. Retrieved from http://mcr.sagepub.com/content/63/1/3.full.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvin CV. Techniques to Support Rapid Cycle Evaluation: The National Evaluation of the Money Follows the Person Demonstration Presented at the Academy. Health Annual Research Meeting; Baltimore, MD: 2013. June. [Google Scholar]

- Kaye HS. Gradual Rebalancing of Medicaid Long-Term Services and Supports Saves Money And Serves More People, Statistical Model Shows. Health Affairs. 2012 June;31(6):1195–1203. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaPlante MP. The Woodwork Effect in Medicaid Long-Term Services and Supports. Journal of Aging & Social Policy. 2013 Apr;25(2):161–180. doi: 10.1080/08959420.2013.766072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng T, Harrington C, O’Malley M. Medicaid home and community-based service programs: Data update Report prepared for the Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. Washington, DC: The Kaiser Family Foundation; 2009. Retrieved from http://www.kff.org/medicaid/upload/7720-03.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzolo MC, Friedman C, Lulinkski-Norris A, Braddock D. Home and Community Based Services (HCBS) waivers: a nationwide study of the states. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. 2013 Feb;51(1):1–21. doi: 10.1352/1934-9556-51.01.001. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23360405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruttner L, Irvin CV. Implications of State Methods for Offering Personal Assistance Services. (MAX Medicaid Policy Brief 18) Washington, DC: Mathematica Policy Research; 2013. Jun, [Google Scholar]

- Shirk c. Rebalancing Long-Term Care: The Role of the Medicaid HCBS Waiver Program. National Health Policy Forum; Washington, DC: 2006. Mar, Retrieved from: http://www.w.nhpf.org/library/background-papers/BP_HCBS.Waivers_03-03-06.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Tribe S. Online Training and HCBS Taxonomy. NASUAD HCBS Conference 2012. 2012 Mar; Retrieved from http://www.nasuad.org/documentation/nasuad_materials/airs%20conference/PDFs/6.%20NASUAD%20I&R%20Support%20Center%20Services,%20Online%20Training%20and%20HCBS%20Taxonomy.pdf.

- Truven Health Analytics/Mathematica Policy Research. Medicaid Home and Community-Based Services (HCBS) Taxonomy. Ann Arbor, MI: Truven Health Analytics; 2012. 2012. Retrieved from http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Computer-Data-and-Systems/MedicaidDataSourcesGenInfo/MAXGeneralInformation.html. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. Understanding Medicaid Home and Community Services: A Primer. Washington, DC: DHHS, ASPE; 2000. Oct, Retreived from http://aspe.hhs.gov/daltcp/reports/primer.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Wenzlow A, Peebles V, Kuncaitis S. The Application of the Taxonomy in Claims Data: A First Look at Expenditures for Medicaid HCBS. Ann Arbor, MI: Mathematica Policy Research; 2011. May, [Google Scholar]