Abstract

As a proliferative and restorative entity, Wnt1 inducible signaling pathway protein 1 (WISP1) is emerging as a novel target for a number of therapeutic strategies that are relevant for disorders such as traumatic injury, neurodegeneration, musculoskeletal disorders, cardiovascular disease, pulmonary compromise, and control of tumor growth as well as distant metastases. WISP1, a target of the wingless pathway Wnt1, oversees cellular mechanisms that include apoptosis, autophagy, cellular migration, stem cell proliferation, angiogenesis, immune cell modulation, and tumorigenesis. The signal transduction pathways of WISP1 are broad and involve phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI 3-K), protein kinase B (Akt), mitogen activated protein (MAP) kinase, c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), caspases, forkhead transcription factors, sirtuins, c-myc, glycogen synthase kinase -3β (GSK-3β), β-catenin, miRNAs, and the mechanistic target of rapamaycin (mTOR). Ultimately, these signal transduction pathways of WISP1 can result in varied and sometimes unpredictable outcomes especially for cell survival, tissue repair, and tumorigenesis that demand increased insight into the critical role WISP1 holds for cellular biology and clinical medicine.

Keywords: Akt, Alzheimer’s, amyloid, apoptosis, autophagy, β-catenin, bone, cancer, cardiac, caspase, CCN4, erythropoietin, fibrosis, forkhead transcription factor, FoxO3a, liver, lung, metastases, miRNA, mTOR, PRAS40, pulmonary, sirtuin, SIRT1, stem cell, WISP1, Wnt

DISCOVERY AND BACKGROUND OF WISP1

As a potential cellular protective entity, Wnt1 inducible signaling pathway protein 1 (WISP1) offers great promise for the development of novel therapeutic strategies against acute and chronic disorders throughout the body that may involve the nervous, musculoskeletal, cardiac, pulmonary, and vascular systems. However, as a proliferative agent, WISP1 can lead to complex biological outcomes and under some circumstances play a principal role during tumor formation. As a result, understanding the role of WISP1 in multiple disorders becomes critical prior to being able to successfully target this pathway for clinical therapies.

WISP1 was identified as a gene in a mouse mammary epithelial cell line [1] and subsequently determined to modulate gastric tumor growth [2]. The protein WISP1 is present in multiple sites throughout the body and is expressed in the epithelium, heart, kidney, lung, pancreas, placenta, ovaries, small intestine, spleen, and brain [3]. WISP1 is a matricellular protein that alters the signaling of other pathways to impact processes such as programmed cell death, extracellular matrix production, cellular migration, and mitosis [4]. WISP1 also can bind to leucine-rich proteoglycans that can impact the ability of other cells to anchor to the extracellular matrix [5].

As a member of the CCN family of proteins, WISP1 also is known as CCN4. The CCN family of proteins consists of six secreted extracellular matrix associated proteins and is defined by the first three members of the family that include Cysteine-rich protein 61, Connective tissue growth factor, and Nephroblastoma over-expressed gene [6]. Each family member contains four cysteine-rich modular domains that include insulin-like growth factor-binding domain, thrombospondin domain, von Willebrand factor type C module, and C-terminal cysteine knot-like domain. Overall, the CCN family has multiple cellular functions that include skeletal system development, vascular repair, cellular survival, and extracellular matrix growth.

WISP1 is a target of the wingless pathway Wnt1, a cysteine-rich glycosylated protein with signaling pathways that can modulate multiple processes that involve neuronal development, angiogenesis, immune cell modulation, tumorigenesis, and stem cell proliferation [7–16]. During injury paradigms, Wnt1 expression can be increased during spinal cord injury [17], ischemic brain injury [18], injury of vascular cells [19, 20], metabolic disturbance [19, 20], non-neuronal cell activation [21–26], and oxidative stress [15, 18, 24]. In addition, Wnt signaling in the brain also can be enhanced during physiological activity such as exercise [27] as well as play a role during mood disorders [28].

Wnt1 appears to be protective against toxic cellular environments. Several studies describe that loss of Wnt1 signaling can result in the cell death of osteoblast progenitors and differentiated osteoblasts [29], injury of human monocytes [8], increased ethanol-induced oxidative stress on bone formation [30], impaired bone repair [31], progressive spinal cord injury [16], loss of neurogenesis [32], enhanced cardiac aging [33], blockade of cellular proliferation [34], inhibition of wound healing with fibroblast to myofibroblast transition [35], increased nitrosative stress during diabetes [36], loss of stem cell differentiation [37], promotion of programmed cell death [3, 21, 38], and defective placental development [39]. In accordance with these studies, activation of Wnt1 or its down-stream signaling pathways can prevent cellular injury such as during experimental diabetes [19, 20, 40], ischemic stroke [18, 41], dopaminergic neuronal injury [7, 15, 23, 42], inflammatory cell loss during neurodegenerative disorders [21, 24, 26, 43], and neuronal synaptic dysfunction [44]. However, the protective and proliferative effects of Wnt1 can be detrimental especially in regards to the ability of Wnt1 signaling to assist with tumor progression. Wnt signaling activity can promote chemotherapy tumor resistance through noncoding RNAs [45] or through enhanced angiogenesis [46] and may be a stimulus for numerous cancer disorders that include breast cancer [47], leukemia [48], and gastrointestinal inflammation and tumorigenesis [49].

WISP1 SIGNALING

Initial work demonstrated that WISP1 can block p53 mediated DNA damage and prevent the induction of apoptosis [50]. However, WISP1 impacts multiple signal transduction pathways to affect cellular proliferation and cellular injury. WISP1 can modulate programmed cell death pathways such as autophagy [3, 51] and apoptosis [50, 52–54]. WISP1 can prevent apoptotic neuronal injury through mitochondrial pathways that minimize expression of the Bim/Bax complex while increasing the expression of Bclx(L)/Bax complex [55]. WISP1 also prevents phosphorylation of p38 mitogen activated protein (MAP) kinase and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) [52] and blocks c-Myc mediated apoptosis [54]. Ultimately, WISP1 can inhibit caspase activation [52, 53, 55].

WISP1 is intimately involved with other pathways that can drive cellular proliferation and survival. These include cellular protective pathways of phosphoinositide 3 –kinase (PI 3-K) and protein kinase B (Akt) [56–63] as well as forkhead transcription factors, sirtuins, and the mechanistic target of rapamaycin (mTOR). For example, activation of Akt limits cell injury and prevents the detrimental effects of amyloid (Aβ) toxicity [21, 64, 65] and oxidative stress [66–69]. PI 3-K and Akt also are critical for agents such as growth factors to promote cell survival. The growth factor and cytokine erythropoietin (EPO) activates Akt through its phosphorylation of serine473 [70, 71] and prevents vascular cell demise through silent mating type information regulator 2 homolog 1 (SIRT1) cell longevity pathways [72]. EPO utilizes Akt to block cell injury during Aβ exposure [26], promote the survival of retinal ganglion cells during N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) toxicity [73], enhance the myocardial protective function of mobilized peripheral blood mononuclear cells [74], foster anti-inflammatory effects [75], protect against sepsis [76], limit renal cell injury [77], and limit cellular injury during models of oxidative stress [78–81]. Similar to EPO, other trophic factors also rely upon the PI 3-K and Akt pathways to foster cellular survival during toxic environments such as insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) [56], insulin [82], and brain derived neurotrophic factor [83].

Mammalian forkhead transcription factors of the O class [FoxO1, FoxO3, FoxO4, and FoxO6) have multiple cellular functions that involve cell growth, cell-cycle regulation, tumorigenesis, metabolism, and cell survival [19, 24, 84–92]. Akt can block apoptosis by phosphorylating FoxO proteins, promoting the sequestration of FoxO proteins by 14-3-3 in the cytoplasm, and ultimately blocking their transcription [53, 78, 93]. Once forkhead transcription factor activity is inhibited, Aβ toxicity can be limited [92, 94], vascular survival is enhanced during experimental diabetes [95, 96], erythroid progenitors differentiation is promoted [97], smooth muscle proliferation is enhanced [98], and the detrimental effects of neonatal hypoxia-ischemic encephalopathy may be reduced [99]. However, it is important to note that forkhead transcription factor blockade also may be detrimental during unchecked tumor growth such as in gastric cancer [100] and lymphoma [101].

Sirtuins are the mammalian homologues of Sir2 and are class III histone deacetylases. These histone deacetylases are nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide [NAD+) dependent and transfer acetyl groups from ε-N-acetyl lysine amino acids that exist on the histones of DNA to regulate transcription. Although histone deacetylases primarily oversee DNA transcription, they also can affect post-translational changes of proteins such as the ability of the sirtuin SIRT1 to control the post-translational phosphorylation of forkhead transcription factors [95, 96]. Of the seven mammalian homologues of Sir2 that include SIRT1 through SIRT7, SIRT1 plays a significant role in oxidative stress, cell metabolism, genomic stability, cell survival, neurodegenerative disease, infection, and cardiovascular disease [102–107]. In regards to cytoprotection, SIRT1 activation can prevent hypoxic injury in retinal ganglion cells [108], modulate cell longevity [109, 110], protect against high-fat diet-induced metabolic abnormalities [111, 112], increase cellular survival during anoxia and ischemia [113, 114], reduce Aβ toxicity [115], reverse impaired fat and glucose metabolism [12, 116–118], maintain mitochondrial processing and quality through autophagy [119], foster cellular protection against radiation [120], protect against renal cell aging [121], block apoptotic pathways in preadipocytes [122], and modulate forkhead mediated apoptotic pathways [53, 72, 96, 118, 123–126]. Yet, other studies suggest that to achieve cytoprotection through sirtuin pathways, the level of sirtuin activity may be critical [53, 72, 115, 127], since SIRT1 gene polymorphisms may affect protein expression during cardiovascular disease [105], SIRT1 activity can promote tumor growth [128, 129], and reduction in SIRT1 activity has been reported to enhance the cytoprotective effects of IGF-1 [130].

mTOR, also known as the mammalian target of rapamycin and FK506-binding protein 12-rapamycin complex-associated protein 1, is a 289-kDa serine/threonine protein kinase that oversees multiple functions that include gene transcription, protein formation, cellular metabolism, cytoskeleton components, tumor growth, and cellular survival [131–135]. mTOR is a critical component of the protein complexes mTOR Complex 1 [mTORC1) and mTOR Complex 2 [mTORC2) [136, 137]. Rapamycin, a macrolide antibiotic from Streptomyces hygroscopicus, inhibits the target of rapamycin [TOR) activity in yeast. In mammals, mTORC1 is more sensitive to the inhibitory effects of rapamycin than mTORC2 [138]. mTORC1 is composed of Raptor (Regulatory-Associated Protein of mTOR), the proline rich Akt substrate 40 kDa (PRAS40), Deptor (DEP domain-containing mTOR interacting protein), and mLST8/GbL (mammalian lethal with Sec13 protein 8, termed mLST8). mTORC2 also includes mLST8 and Deptor, but has additional components that are Rictor (Rapamycin-Insensitive Companion of mTOR), the mammalian stress-activated protein kinase interacting protein (mSIN1), and the protein observed with Rictor-1 (Protor-1) [136, 137]. Similar to WISP1, mTOR signaling is associated with PI 3-K, Akt, forkhead transcription factors, PRAS40, AMP activated protein kinase (AMPK), and p70 ribosomal S6 kinase (p70S6K) to affect cellular survival through programmed cell death pathways that involve apoptosis, autophagy, and necroptosis [60, 62, 63, 76, 79, 139–149]. For example, Akt can control mTORC1 activity through the modulation of hamartin (tuberous sclerosis 1)/tuberin (tuberous sclerosis 2) (TSC1/TSC2) complex, an inhibitor of mTORC1 [150–152]. Akt can phosphorylate TSC2 on multiple sites that leads to the destabilization of TSC2 and disruption of its interaction with TSC1. Control of the TSC1/TSC2 complex principally occurs though the phosphorylation of TSC2 by Akt, extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERKs), activating protein p90 ribosomal S6 kinase 1 (RSK1), AMPK, and glycogen synthase kinase -3β (GSK-3β). In regards to programmed cell death with mTOR signaling, these pathways do not always function independently and can influence one another. Therapies that target mTORC1 and mTORC2 to overcome leukemic cell resistance may require the induction of apoptosis with the repression of autophagy [3, 153]. In addition, WISP1 can prevent cell death primarily through inhibition of GSK-3β and apoptotic pathways with additional pathways that require inhibition of autophagy [51]. Inhibition of mTOR in acute lymphoblastic leukemia leads to autophagy dependent cell loss with features that are consistent with necroptosis [154].

WISP1 can block cellular injury through the PI 3-K and Akt pathways. Activation of Akt in association with WISP1 occurs during DNA damage [50], mechanical strain in osteoblasts [155], fibroblast proliferation in airway remodeling [156], cardiomyocyte injury [52], vascular smooth muscle proliferation [157], oxidative stress [51, 53, 55], and Aβ exposure [152]. Following Akt activation, WISP1 results in the inhibitory phosphorylation of GSK-3β [51, 52, 55, 156]. During the inhibition of GSK-3β, β-catenin is not phosphorylated, ubiquinated, or degraded which allows translocation of this “anti-apoptotic” protein to the nucleus [8, 10, 15, 21, 27, 158, 159]. As a result, WISP1 during GSK-3β inhibition maintains the integrity of β-catenin and promotes the translocation of β-catenin to the nucleus in neurons [51], cardiomyocytes [52], hepatocytes [160], epithelial lung cells [161], and growth plate cartilage [31] that can lead to tissue repair. Interestingly, β-catenin that also is dependent upon Wnt signaling promotes the expression of WISP1 [162, 163]. However, it should be noted that WISP1 maintenance of β-catenin also can lead to tumor progression [164], metastatic disease [165], and represent a poor clinical prognosis during cancer diagnosis [166].

As previously described, the Wnt signaling pathway can protect cells during a number of injury paradigms. In such cases, cytoprotection may be afforded through forkhead transcription post-translational phosphorylation and inhibition. During oxidative stress, osteoblastic differentiation is preserved through up-regulation of Wnt signaling and inhibition of FoxO3a activity [167]. In hepatic cells that are exposed to chronic oxidative injury, Wnt signaling blocks FoxO3a activity to prevent apoptotic cell death [168]. Furthermore, trophic factors such as EPO have been shown to use a Wnt1 dependent mechanism to phosphorylate FoxO3a and block the trafficking of FoxO3a to the cell nucleus to prevent apoptotic demise [19]. Wnt signaling also affords protection of inflammatory microglial cells through forkhead transcription factor inhibition [24]. Through similar pathways, WISP1 protects neurons through the posttranslational phosphorylation of FoxO3a, by sequestering FoxO3a in the cytoplasm with protein 14-3-3, and by limiting deacytelation of FoxO3a [53].

Sirtuins, such as SIRT1, are effective mediators of cell survival during toxic insults if these histone deacetylases remain intact during cellular insults. Loss of sirtuin activity can be a result of the nuclear degradation of the sirtuin SIRT1 [127] and lead to the subsequent activation of caspases [108, 127]. SIRT1 degradation may be mediated by apoptotic pathways linked to p38 [169] and JNK1 [170]. WISP1 cytoprotection appears to be dependent upon SIRT1 pathways. WISP1 maintains SIRT1 expression and increases SIRT1 activity during oxidative stress to afford cellular protection [53]. In addition, WISP1 also fosters SIRT1 nuclear translocation [53] that is usually necessary for protection against apoptotic injury [72, 96, 171]. WISP1 relies upon the modulation of FoxO3a and caspase activity during oxidative stress to maintain the integrity of SIRT1 [53] similar to other injury paradigms [123, 126, 172]. Over-expression of FoxO3a leads to increased caspase 1 and caspase 3 activity during oxidant stress [95, 173]. WISP1 blocks FoxO3a activity through the inhibitory post-translational phosphorylation of FoxO3a and prevents caspase 1 and caspase 3 activation during oxidative stress that would otherwise lead to the degradation of SIRT1.

Wnt signaling that includes WISP1 employs several components of the mTOR pathway that can oversee cellular survival and proliferation [174, 175]. In injury models that involve cultured macrophages or neurons exposed to hypoxia, Wnt1 expression is increased [18, 176]. Enhancement of Wnt signaling results in increased Akt activity that promotes cellular protection [18, 21] and also leads to elevated mTOR activity to foster human β-cell proliferation [177] and epithelial stem cell growth [178]. Without mTOR activation, Wnt1 has been shown to lose the ability to support cellular proliferation [179]. The growth factor EPO requires Wnt1, mTOR, and p70S6K to foster cytoprotection for microglial cells during oxidant stress [25] and during Aβ toxicity [26].

In regards to WISP1 and mTOR, WISP1 targets several pathways of mTOR by activating mTOR and phosphorylating p70S6K and 4EBP1 through the control of the regulatory mTOR component PRAS40 [180]. WISP1 controls PRAS40 by sequestering this protein in the intracellular compartment. WISP1 also drives the post-translational phosphorylation of AMPK by differentially decreasing phosphorylation of TSC2 at Ser1387, a target of AMPK, and increasing phosphorylation of TSC2 at Thr1462, a target of Akt1 [152]. WISP1 increases TSC2 activation by limiting AMPK activation. When active, AMPK can phosphorylate TSC2 on serine1387 to ultimately inhibit the activity of mTOR and the mTORC1 complex [181]. The ability of WISP1 to limit TSC2 (Ser1387) phosphorylation appears to allow WISP1 to increase the activity of downstream mTOR components, such as p70S6K. During Aβ exposure, WISP1 can phosphorylate mTOR, p70S6K and the eukaryotic initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1 (4EBP1) [180] which is indicative of increased mTOR activity [182]. However, during gene silencing of TSC2, phosphorylation of p70S6K is further enhanced during Aβ exposure alone and in the presence of WISP1, suggesting that down-regulation of phosphorylation of the TSC2 (Ser1387) by WISP1 contributes to enhanced activity of the mTOR pathway [152]. On the other end, WISP1 also increases TSC2 activity by promoting the Akt pathway through phosphorylation of TSC2 at Thr1462. However, it appears that a minimal level of TSC2 activity is necessary to modulate WISP1 cytoprotection, since gene knockdown of TSC2 impairs the ability of WISP1 to provide cytoprotection [152].

WISP1: A PROLIFERATIVE AND REPARATIVE AGENT

Increasing focus upon WISP1 and its cellular pathways has fueled enthusiasm for new therapeutic strategies for this CCN family member. In models of third degree burns in mouse models, WISP1 mRNA transcripts are up-regulated during wound healing, suggesting that WISP1 may be a key element for tissue repair [183]. Bone formation following growth plate cartilage injury also has been shown to involve expression of the WISP1 gene [31]. During mechanical stretch injury of lung epithelial cell injury, WISP1 is up-regulated in stretched cells and loss of WISP1 prevents mesenchymal transition necessary for the repair of lung epithelial cells [184]. WISP1 through β-catenin/p300 may be necessary for epithelial cell repair during inflammatory lung injury [161]. WISP1 also promotes mesenchymal cell proliferation and osteoblastic differentiation with the repression of chondrocytic differentiation to further bone development [185] and fracture repair [186]. WISP1 may enhance osteogenesis through bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP-2) [187]. Bone formation through parathyroid hormone treatment also may proceed through increased WISP1 expression [188]. However, in some cases, WISP1 may be considered a factor for the progression of osteoarthritis since WISP1 can result in chondrocyte hypertrophy through transforming growth factor-β signaling and activin-like kinase (ALK)5 [189].

In the nervous system, WISP1 may have a vital role in blocking cell death and promoting tissue repair. During oxidant stress with oxygen-glucose deprivation, WISP1 expression is up-regulated and WISP1 is necessary to confer neuronal protection by limiting the expression of the Bim/Bax complex, increasing the expression of Bclx[L)/Bax complex, and blocking cytochrome c release and caspase 3 activation [55]. WISP1 autoregulates its own expression that is dependent upon increased β-catenin activity [51, 190]. WISP1 prevents the phosphorylation and degradation of β-catenin to maintain the activity of β-catenin. This promotion of β-catenin activity also serves to limit the induction of autophagy [51]. Through an autoregulatory loop, WISP1 also has been shown to enhance neuronal survival by limiting FoxO3a deacytelation, blocking caspase 1 and 3 activation, and fostering SIRT1 nuclear trafficking [53]. In regards to immune mediated therapies that may be effective against neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease [133, 191–196], WISP1 can protect central nervous system microglial cells against Aβ toxicity by employing mTOR downstream pathways that modulate PRAS40 [180] and TSC2 [152] to increase mTOR activity [197].

WISP1 also may be a significant factor for vascular and cardiovascular repair. Following saphenous vein crush injury, WISP1 expression is selectively up-regulated and may support vascular repair and regeneration [198]. WISP1 also promotes vascular smooth muscle proliferation that may be important for tissue repair during injury or affect restenosis following vascular grafting [157, 199]. Yet, WISP1 does not appear to lead to cellular proliferation in aging vascular cells [200] and may promote senescence [201]. WISP1 has been shown to be effective in rescuing cardiomyocytes from doxorubicin toxicity, a chemotherapeutic agent that leads to acute and chronic cardiac and renal injury [202]. Through PI3-K, Akt, and survivin, WISP1 prevents cardiomyocyte cell death [52].

The reparative properties of WISP1 may be the result of the ability of WISP1 to influence stem cell proliferation, migration, and differentiation. WISP1 is up-regulated during stem cell migration [183] and WISP1 may be one of several components that affect induced pluripotent stem cell reprogramming [203, 204]. WISP1 is differentially regulated during human embryonic stem cell and adipose-derived stem cell differentiation. For example, WISP1 is up-regulated in human embryonic stem cells and repressed in adipose-derived stem cells during hepatic differentiation [205]. WISP1 in conjunction with β-catenin also may be necessary for the differentiation of marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells [206].

Although the proliferative nature of WISP1 may play a vital role during cell recovery and tissue repair, evidence also exists for CCN family members [207] and WISP1 to lead to fibrotic tissue injury such as during cardiac remodeling following infarction [208]. WISP1 expression also is significantly elevated in primary fibroblasts during idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis [209] with WISP1 expression potentially regulated by the microRNA [miRNA) miR-92a [210]. WISP1 expression has been correlated with fibrosis in models of liver fibrogenesis [211], asthma airway remodeling [156], and in murine models of alveolar epithelial cell hyperplasia [212].

THE VARIABLE IMPACT OF WISP1 IN TUMORIGENESIS

WISP1 may play a role in tumor cell development and progression. Early studies identified that the genomic DNA of WISP1 was amplified in colon cancer cell lines as well as in human colon tumors [1]. Subsequent work has suggested an association of WISP1 with chronic inflammatory bowel disease such as ulcerative colitis [162]. The increased expression of Wnt1, WISP1, survivin, and cyclin-D1 observed in colorectal cancer may be suggestive that these pathways work synergistically to promote cell cycle progression and tumor growth while blocking apoptosis [213]. WISP1 expression may be suggestive of more advanced progression in some tumors, such as those associated with breast cancer [214, 215] and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma [216]. During chronic ethanol consumption, WISP1 has been implicated in hepatic cell proliferation that can result in liver cancer [160]. WISP1 has been associated with abnormal expression and gene fusion during lung adenocarcinoma [217]. In the nervous system, WISP1 expression is increased in neurofibromatosis type 1 tumorigenesis [218].

Although variants of WISP1 have been described to be extremely aggressive in promoting cell growth in scirrhous gastric carcinomas [219] and cholangiocarcinoma [220] leading to striking cellular transformation and rapid piling-up growth, non-variant WISP1 expression in lung cancer cells has been shown to be significantly less invasive, may inhibit lung metastases, and may block tumor cell invasion and motility [221]. Differential expression of CCN family members in breast cancer also has suggested that WISP1 may function to limit breast cancer growth [222]. Furthermore, Notch1 activation that results in increased WISP1 expression can suppress melanoma growth [223]. Suppression of melanoma tumor growth is lost during WISP1 gene knockdown [223]. However, this ability of WISP1 to limit metastatic disease may be tissue specific since WISP1 expression and activity in experimental models may promote early prostate cancer and foster distant bone metastatic disease [224].

FUTURE PROSPECTIVES AND CONSIDERATIONS

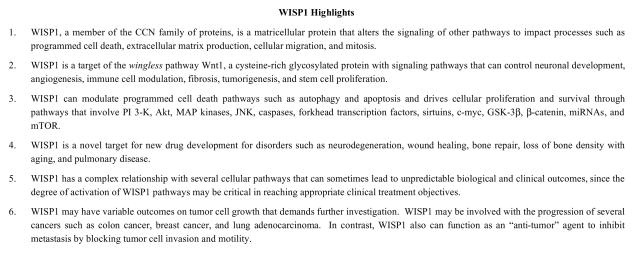

As both a proliferative and restorative entity, WISP1 holds promise for a number of emerging therapeutic strategies that can address traumatic injury, neurodegeneration, musculoskeletal disorders, cardiopulmonary and vascular disease, and the control of tumor growth as well as distant metastases (Fig. 1). WISP1 is a target of the wingless pathway Wnt1 that is closely tied to pathways of neuronal and vascular development, cytoprotection, inflammatory modulation, and cancer cell growth. WISP1 is linked to multiple signal transduction pathways that include PI 3-K, Akt, MAP kinases, JNK, caspases, forkhead transcription factors, sirtuins, c-myc, GSK-3β, β-catenin, miRNAs, and mTOR. Through these pathways, WISP1 signaling can ultimately alter the course of programmed cell death pathways such as apoptosis and autophagy to promote cytoprotection and tissue repair.

Fig. 1.

Topical Highlights for the Restorative and Proliferative Effects of WISP1.

However, WISP1 has a complex relationship with several cellular pathways that can lead to variable biological and clinical outcomes. For example, trophic factors such as insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) [56], insulin [82], brain derived neurotrophic factor [83], and EPO [70, 73, 75–77, 225–228] rely upon Akt activation to protect cells against toxic cellular insults. In particular, EPO activates Akt using Wnt signaling pathways to phosphorylate FoxO proteins, promote the sequestration of these proteins by 14-3-3 in the cytoplasm, and block the transcription of FoxO proteins [19, 72, 78, 97, 229]. WISP1 also affords cytoprotection through the post-translational phosphorylation and inhibition of FoxO3a [53]. Under some conditions, blockade of these signal transduction pathways may be detrimental since inhibition of FoxO proteins can promote unwanted tumor growth such as in gastric cancer [100], lymphoma [101], and hepatic cancer [230]. Furthermore, agents such as EPO that are used for the treatment of anemia can be contraindicated in patients with hypertension, since both acute and long-term administration of EPO can significantly elevate mean arterial pressure [231]. These observations may be tied to Wnt signaling and WISP1. Polymorphisms of WISP1 have been associated with hypertension in Japanese men related to both systolic and diastolic pressure [232].

Similar caveats hold true for WISP1 with SIRT1 and mTOR. WISP1 maintains SIRT1 expression and increases SIRT1 activity during oxidative stress to foster cellular protection [53]. Yet, enhanced SIRT1 activity may lead to tumor growth [128, 129]. In addition, some protective mechanisms appear to require a limited activation of SIRT1 [53, 72, 115, 127] and others may necessitate an actual reduction in SIRT1 activity, such as those with IGF-1 [130]. In consideration of mTOR, WISP1 requires activation of mTOR signaling with inhibition of specific pathways such as PRAS40 to offer cellular protection against Aβ exposure [152, 180]. Although these studies suggest a role for WISP1 in disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease through the activation of mTOR pathways, one must proceed with caution since the degree of mTOR activation may be critical in treating neurodegenerative disorders [133, 137]. In favor of mTOR activation, mTOR activation has been shown to protect neuronal networks controlling memory [233]. Activity of mTOR also may be required for long-term memory formation [234], the reconsolidation phase of traumatic memory [235], and memory restoration during vascular dementia [236]. Loss of mTOR activity can impair long-term potentiation and synaptic plasticity in animal models of Alzheimer’s disease [237]. Increased mTORC1 activity may necessary to regulate the β-site amyloid precursor protein (APP)-cleaving enzyme 1 (β-secretase, BACE1) that promotes Aβ accumulation in Alzheimer’s disease, since high mTORC1 activity depletes BACE1 and is able to reduce Aβ generation [238]. Yet, other work suggests that that inhibition of mTOR may be necessary for the treatment of epilepsy [137, 239, 240], some stages of Alzheimer’s disease [133, 137, 241, 242], and drug addiction associated memories [243]. In studies with Alzheimer’s disease, blockade of mTOR can lead to a reduction in BACE1 to reduce Aβ accumulation [149], enhance Aβ clearance in cell lines and animal models, and improve spatial learning through the induction of autophagy [244].

In addition to the nervous system, WISP1 is a novel target for new drug development for disorders such as wound healing, bone repair, loss of bone density with aging, and pulmonary disease. Targeting WISP1 also may be critical for repair of vascular trauma as well as preventing stenosis of vessels following grafting [157, 199]. WISP1 may be effective as a co-treatment to prevent cardiomyocyte injury during chemotherapy regimens that lead to cardiotoxicity [52]. Yet, developing WISP1 for such disorders must be carefully focused since increased WISP1 expression may have clinical side effects such as fibrotic tissue injury that result in liver fibrogenesis [211], asthma airway remodeling [156], and alveolar epithelial cell hyperplasia [212].

As a proliferative agent, WISP1 also can impact tumor cell growth by increasing the risk for disorders that can lead to tumorigenesis [162] and also directly resulting in several types of cancer such as colon cancer [1], breast cancer [214, 215], neurofibromatosis type 1 tumorigenesis [218], lung adenocarcinoma [217], and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma [216]. However, the relationship of WISP1 to tumor cell development and progression requires further investigation. Although variants of WISP1 can lead to aggressive tumor cell growth [219], non-variant WISP1 expression can be less invasive and may inhibit metastases by blocking tumor cell invasion and motility [221]. In addition, other studies provide additional support for WISP1 to act as an “anti-tumor” agent in breast cancer [222] and melanoma [223]. The mechanisms that determine the ability of WISP1 to affect cell cycle pathways as well as programmed cell death may be one consideration to provide further insight into the necessary signal transduction pathways of WISP1 for developing clinically effective cancer treatments.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the following grants to Kenneth Maiese: American Diabetes Association, American Heart Association [National), Bugher Foundation Award, Janssen Neuroscience Award, LEARN Foundation Award, NIH NIEHS, NIH NIA, NIH NINDS, and NIH ARRA.

Footnotes

Send Orders for Reprints to reprints@benthamscience.net

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Pennica D, Swanson TA, Welsh JW, Roy MA, Lawrence DA, Lee J, et al. WISP genes are members of the connective tissue growth factor family that are up-regulated in wnt-1-transformed cells and aberrantly expressed in human colon tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998 Dec 8;95(25):14717–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davies SR, Davies ML, Sanders A, Parr C, Torkington J, Jiang WG. Differential expression of the CCN family member WISP-1, WISP-2 and WISP-3 in human colorectal cancer and the prognostic implications. Int J Oncol. 2010 May;36(5):1129–36. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maiese K, Chong ZZ, Shang YC, Wang S. Targeting disease through novel pathways of apoptosis and autophagy. Expert opinion on therapeutic targets. 2012 Dec;16(12):1203–14. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2012.719499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yeger H, Perbal B. The CCN family of genes: a perspective on CCN biology and therapeutic potential. J Cell Commun Signal. 2007 Dec;1(3–4):159–64. doi: 10.1007/s12079-008-0022-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Desnoyers L, Arnott D, Pennica D. WISP-1 binds to decorin and biglycan. J Biol Chem. 2001 Dec 14;276(50):47599–607. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108339200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berschneider B, Konigshoff M. WNT1 inducible signaling pathway protein 1 (WISP1): a novel mediator linking development and disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2010 Mar;43(3):306–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berwick DC, Harvey K. The regulation and deregulation of Wnt signaling by PARK genes in health and disease. J Mol Cell Biol. 2014 Feb;6(1):3–12. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjt037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borrell-Pages M, Romero JC, Badimon L. LRP5 negatively regulates differentiation of monocytes through abrogation of Wnt signalling. J Cell Mol Med. 2014 Feb;18(2):314–25. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li F, Chong ZZ, Maiese K. Winding through the WNT pathway during cellular development and demise. Histol Histopathol. 2006 Jan;21(1):103–24. doi: 10.14670/hh-21.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loilome W, Bungkanjana P, Techasen A, Namwat N, Yongvanit P, Puapairoj A, et al. Activated macrophages promote Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in cholangiocarcinoma cells. Tumour biology : the journal of the International Society for Oncodevelopmental Biology and Medicine. 2014 Feb 19; doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-1698-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maiese K. Triple play: Promoting neurovascular longevity with nicotinamide, WNT, and erythropoietin in diabetes mellitus. Biomed Pharmacother. 2008 Apr-May;62(4):218–32. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maiese K, Chong ZZ, Shang YC, Wang S. Translating cell survival and cell longevity into treatment strategies with SIRT1. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2011;52(4):1173–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maiese K, Li F, Chong ZZ, Shang YC. The Wnt signaling pathway: Aging gracefully as a protectionist? Pharmacol Ther. 2008 Apr;118(1):58–81. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uzdensky AB, Demyanenko SV, Bibov MY. Signal transduction in human cutaneous melanoma and target drugs. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2013 Oct;13(8):843–66. doi: 10.2174/1568009611313080004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wei L, Sun C, Lei M, Li G, Yi L, Luo F, et al. Activation of Wnt/beta-catenin Pathway by Exogenous Wnt1 Protects SH-SY5Y Cells Against 6-Hydroxydopamine Toxicity. J Mol Neurosci. 2013 Jan;49(1):105–15. doi: 10.1007/s12031-012-9900-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu D, Zhao W, Pan G, Qian M, Zhu X, Liu W, et al. Expression of Nemo-like kinase after spinal cord injury in rats. J Mol Neurosci. 2014 Mar;52(3):410–8. doi: 10.1007/s12031-013-0191-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gonzalez-Fernandez C, Fernandez-Martos CM, Shields S, Arenas E, Rodriguez FJ. Wnts are expressed in the spinal cord of adult mice and are differentially induced after injury. J Neurotrauma. 2013 Dec 24; doi: 10.1089/neu.2013.3067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chong ZZ, Shang YC, Hou J, Maiese K. Wnt1 neuroprotection translates into improved neurological function during oxidant stress and cerebral ischemia through AKT1 and mitochondrial apoptotic pathways. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2010 Mar-Apr;3(2):153–65. doi: 10.4161/oxim.3.2.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chong ZZ, Hou J, Shang YC, Wang S, Maiese K. EPO Relies upon Novel Signaling of Wnt1 that Requires Akt1, FoxO3a, GSK-3beta, and beta-Catenin to Foster Vascular Integrity During Experimental Diabetes. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2011 May 1;8(2):103–20. doi: 10.2174/156720211795495402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chong ZZ, Shang YC, Maiese K. Vascular injury during elevated glucose can be mitigated by erythropoietin and Wnt signaling. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2007 Aug;4(3):194–204. doi: 10.2174/156720207781387150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chong ZZ, Li F, Maiese K. Cellular demise and inflammatory microglial activation during beta-amyloid toxicity are governed by Wnt1 and canonical signaling pathways. Cell Signal. 2007 Jun;19(6):1150–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.L’Episcopo F, Tirolo C, Testa N, Caniglia S, Morale MC, Cossetti C, et al. Reactive astrocytes and Wnt/beta-catenin signaling link nigrostriatal injury to repair in 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine model of Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2011 Feb;41(2):508–27. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marchetti B, L’Episcopo F, Morale MC, Tirolo C, Testa N, Caniglia S, et al. Uncovering novel actors in astrocyte-neuron crosstalk in Parkinson’s disease: the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling cascade as the common final pathway for neuroprotection and self-repair. Eur J Neurosci. 2013 May;37(10):1550–63. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shang YC, Chong ZZ, Hou J, Maiese K. Wnt1, FoxO3a, and NF-kappaB oversee microglial integrity and activation during oxidant stress. Cell Signal. 2010 Sep;22(9):1317–29. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shang YC, Chong ZZ, Wang S, Maiese K. Erythropoietin and Wnt1 Govern Pathways of mTOR, Apaf-1, and XIAP in Inflammatory Microglia. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2011 Oct 19;8(4):270–85. doi: 10.2174/156720211798120990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shang YC, Chong ZZ, Wang S, Maiese K. Prevention of beta-amyloid degeneration of microglia by erythropoietin depends on Wnt1, the PI 3-K/mTOR pathway, Bad, and Bcl-xL. Aging (Albany NY) 2012 Mar 3;4(3):187–201. doi: 10.18632/aging.100440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bayod S, Menella I, Sanchez-Roige S, Lalanza JF, Escorihuela RM, Camins A, et al. Wnt pathway regulation by long-term moderate exercise in rat hippocampus. Brain Res. 2014 Jan 16;1543:38–48. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pilar-Cuellar F, Vidal R, Diaz A, Castro E, dos Anjos S, Pascual-Brazo J, et al. Neural plasticity and proliferation in the generation of antidepressant effects: hippocampal implication. Neural Plast. 2013;2013:537265. doi: 10.1155/2013/537265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Almeida M, Han L, Bellido T, Manolagas SC, Kousteni S. Wnt proteins prevent apoptosis of both uncommitted osteoblast progenitors and differentiated osteoblasts by beta-catenin-dependent and -independent signaling cascades involving Src/ERK and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT. J Biol Chem. 2005 Dec 16;280(50):41342–51. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502168200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen JR, Lazarenko OP, Shankar K, Blackburn ML, Badger TM, Ronis MJ. A role for ethanol-induced oxidative stress in controlling lineage commitment of mesenchymal stromal cells through inhibition of Wnt / beta-catenin signaling. J Bone Miner Res. 2010 Jan 8; doi: 10.1002/jbmr.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Macsai CE, Georgiou KR, Foster BK, Zannettino AC, Xian CJ. Microarray expression analysis of genes and pathways involved in growth plate cartilage injury responses and bony repair. Bone. 2012 May;50(5):1081–91. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2012.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.L’Episcopo F, Tirolo C, Testa N, Caniglia S, Morale MC, Deleidi M, et al. Plasticity of Subventricular Zone Neuroprogenitors in MPTP (1-Methyl-4-Phenyl-1,2,3,6-Tetrahydropyridine) Mouse Model of Parkinson’s Disease Involves Cross Talk between Inflammatory and Wnt/beta-Catenin Signaling Pathways: Functional Consequences for Neuroprotection and Repair. J Neurosci. 2012 Feb 8;32(6):2062–85. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5259-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li Q, Hannah SS. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling is downregulated but restored by nutrition interventions in the aged heart in mice. Archives of gerontology and geriatrics. 2012 Nov;55(3):749–54. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2012.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin F, Chen Y, Li X, Zhao Q, Tan Z. Over-expression of circadian clock gene Bmal1 affects proliferation and the canonical Wnt pathway in NIH-3T3 cells. Cell Biochem Funct. 2013 Mar;31(2):166–72. doi: 10.1002/cbf.2871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu J, Wang Y, Pan Q, Su Y, Zhang Z, Han J, et al. Wnt/beta-catenin pathway forms a negative feedback loop during TGF-beta1 induced human normal skin fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition. J Dermatol Sci. 2012 Jan;65(1):38–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2011.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu Q, Li J, Cheng R, Chen Y, Lee K, Hu Y, et al. Nitrosative stress plays an important role in wnt pathway activation in diabetic retinopathy. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013 Apr 1;18(10):1141–53. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shah N, Morsi Y, Manasseh R. From mechanical stimulation to biological pathways in the regulation of stem cell fate. Cell Biochem Funct. 2014 Feb 27; doi: 10.1002/cbf.3027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.He B, Reguart N, You L, Mazieres J, Xu Z, Lee AY, et al. Blockade of Wnt-1 signaling induces apoptosis in human colorectal cancer cells containing downstream mutations. Oncogene. 2005 Apr 21;24(18):3054–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kohan-Ghadr HR, Smith LC, Arnold DR, Murphy BD, Lefebvre RC. Aberrant expression of E-cadherin and beta-catenin proteins in placenta of bovine embryos derived from somatic cell nuclear transfer. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2012 May;24(4):588–98. doi: 10.1071/RD11162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pandey S, Chandravati Targeting Wnt-Frizzled signaling in cardiovascular diseases. Mol Biol Rep. 2013 Oct;40(10):6011–8. doi: 10.1007/s11033-013-2710-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xing Y, Zhang X, Zhao K, Cui L, Wang L, Dong L, et al. Beneficial effects of sulindac in focal cerebral ischemia: a positive role in Wnt/beta-catenin pathway. Brain Res. 2012 Oct 30;1482:71–80. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.08.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.L’Episcopo F, Serapide MF, Tirolo C, Testa N, Caniglia S, Morale MC, et al. A Wnt1 regulated Frizzled-1/beta-Catenin signaling pathway as a candidate regulatory circuit controlling mesencephalic dopaminergic neuron-astrocyte crosstalk: Therapeutical relevance for neuron survival and neuroprotection. Molecular neurodegeneration. 2011;6:49. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-6-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marchetti B, Pluchino S. Wnt your brain be inflamed? Yes, it Wnt! Trends Mol Med. 2013 Mar;19(3):144–56. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sowers LP, Loo L, Wu Y, Campbell E, Ulrich JD, Wu S, et al. Disruption of the non-canonical Wnt gene PRICKLE2 leads to autism-like behaviors with evidence for hippocampal synaptic dysfunction. Mol Psychiatry. 2013 Oct;18(10):1077–89. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang Y, Li H, Hou S, Hu B, Liu J, Wang J. The noncoding RNA expression profile and the effect of lncRNA AK126698 on cisplatin resistance in non-small-cell lung cancer cell. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e65309. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cui J, Jiang W, Wang S, Wang L, Xie K. Role of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in drug resistance of pancreatic cancer. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18(17):2464–71. doi: 10.2174/13816128112092464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang Y, Ding L, Wang X, Zhang J, Han W, Feng L, et al. Pterostilbene simultaneously induces apoptosis, cell cycle arrest and cyto-protective autophagy in breast cancer cells. Am J Transl Res. 2012;4(1):44–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Doubravska L, Simova S, Cermak L, Valenta T, Korinek V, Andera L. Wnt-expressing rat embryonic fibroblasts suppress Apo2L/TRAIL-induced apoptosis of human leukemia cells. Apoptosis. 2008 Apr;13(4):573–87. doi: 10.1007/s10495-008-0191-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee G, Goretsky T, Managlia E, Dirisina R, Singh AP, Brown JB, et al. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase signaling mediates beta-catenin activation in intestinal epithelial stem and progenitor cells in colitis. Gastroenterology. 2010 Sep;139(3):869–81. 81 e1–9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Su F, Overholtzer M, Besser D, Levine AJ. WISP-1 attenuates p53-mediated apoptosis in response to DNA damage through activation of the Akt kinase. Genes Dev. 2002 Jan 1;16(1):46–57. doi: 10.1101/gad.942902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang S, Chong ZZ, Shang YC, Maiese K. WISP1 (CCN4) autoregulates its expression and nuclear trafficking of beta-catenin during oxidant stress with limited effects upon neuronal autophagy. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2012 Apr 4;9(2):89–99. doi: 10.2174/156720212800410858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Venkatesan B, Prabhu SD, Venkatachalam K, Mummidi S, Valente AJ, Clark RA, et al. WNT1-inducible signaling pathway protein-1 activates diverse cell survival pathways and blocks doxorubicin-induced cardiomyocyte death. Cell Signal. 2010 May;22(5):809–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang S, Chong ZZ, Shang YC, Maiese K. WISP1 neuroprotection requires FoxO3a post-translational modulation with autoregulatory control of SIRT1. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2013 Nov 12;10(1):54–60. doi: 10.2174/156720213804805945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.You Z, Saims D, Chen S, Zhang Z, Guttridge DC, Guan KL, et al. Wnt signaling promotes oncogenic transformation by inhibiting c-Myc-induced apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 2002 Apr 29;157(3):429–40. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200201110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang S, Chong ZZ, Shang YC, Maiese K. Wnt1 inducible signaling pathway protein 1 (WISP1) blocks neurodegeneration through phosphoinositide 3 kinase/Akt1 and apoptotic mitochondrial signaling involving Bad, Bax, Bim, and Bcl-xL. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2012 Feb;9(1):20–31. doi: 10.2174/156720212799297137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen C, Xu Y, Song Y. IGF-1 gene-modified muscle-derived stem cells are resistant to oxidative stress via enhanced activation of IGF-1R/PI3K/AKT signaling and secretion of VEGF. Mol Cell Biochem. 2014 Jan;386(1–2):167–75. doi: 10.1007/s11010-013-1855-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chong ZZ, Kang J, Li F, Maiese K. mGluRI Targets Microglial Activation and Selectively Prevents Neuronal Cell Engulfment Through Akt and Caspase Dependent Pathways. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2005 Jul;2(3):197–211. doi: 10.2174/1567202054368317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chong ZZ, Kang JQ, Maiese K. AKT1 drives endothelial cell membrane asymmetry and microglial activation through Bcl-xL and caspase 1, 3, and 9. Exp Cell Res. 2004 Jun 10;296(2):196–207. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gezginci-Oktayoglu S, Sacan O, Bolkent S, Ipci Y, Kabasakal L, Sener G, et al. Chard (Beta vulgaris L. var. cicla) extract ameliorates hyperglycemia by increasing GLUT2 through Akt2 and antioxidant defense in the liver of rats. Acta histochemica. 2014 Jan;116(1):32–9. doi: 10.1016/j.acthis.2013.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gubern C, Camos S, Hurtado O, Rodriguez R, Romera VG, Sobrado M, et al. Characterization of Gcf2/Lrrfip1 in experimental cerebral ischemia and its role as a modulator of Akt, mTOR and beta-catenin signaling pathways. Neuroscience. 2014 Mar 14;268C:48–65. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jiang Y, Li L, Liu B, Zhang Y, Chen Q, Li C. Vagus Nerve Stimulation Attenuates Cerebral Ischemia and Reperfusion Injury via Endogenous Cholinergic Pathway in Rat. PLoS One. 2014;9(7):e102342. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Maiese K, Chong ZZ, Wang S, Shang YC. Oxidant Stress and Signal Transduction in the Nervous System with the PI 3-K, Akt, and mTOR Cascade. International journal of molecular sciences. 2013;13(11):13830–66. doi: 10.3390/ijms131113830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang Y, Wang YX, Liu T, Law PY, Loh HH, Qiu Y, et al. mu-Opioid Receptor Attenuates Abeta Oligomers-Induced Neurotoxicity Through mTOR Signaling. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2014 Aug 21; doi: 10.1111/cns.12316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chong ZZ, Li F, Maiese K. Stress in the brain: novel cellular mechanisms of injury linked to Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2005 Jul;49(1):1–21. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zara S, De Colli M, Rapino M, Pacella S, Nasuti C, Sozio P, et al. Ibuprofen and lipoic acid conjugate neuroprotective activity is mediated by Ngb/Akt intracellular signaling pathway in Alzheimer’s disease rat model. Gerontology. 2013;59(3):250–60. doi: 10.1159/000346445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chong ZZ, Lin SH, Maiese K. The NAD+ precursor nicotinamide governs neuronal survival during oxidative stress through protein kinase B coupled to FOXO3a and mitochondrial membrane potential. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2004 Jul;24(7):728–43. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000122746.72175.0E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li F, Chong ZZ, Maiese K. Microglial integrity is maintained by erythropoietin through integration of Akt and its substrates of glycogen synthase kinase-3beta, beta-catenin, and nuclear factor-kappaB. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2006 Aug;3(3):187–201. doi: 10.2174/156720206778018758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schluesener JK, Zhu X, Schluesener HJ, Wang GW, Ao P. Key network approach reveals new insight into Alzheimer’s disease. IET systems biology. 2014 Aug;8(4):169–75. doi: 10.1049/iet-syb.2013.0047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Uranga RM, Katz S, Salvador GA. Enhanced phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt signaling has pleiotropic targets in hippocampal neurons exposed to iron-induced oxidative stress. J Biol Chem. 2013 Jul 5;288(27):19773–84. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.457622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chong ZZ, Kang JQ, Maiese K. Erythropoietin is a novel vascular protectant through activation of Akt1 and mitochondrial modulation of cysteine proteases. Circulation. 2002 Dec 3;106(23):2973–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000039103.58920.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Maiese K, Li F, Chong ZZ. New avenues of exploration for erythropoietin. Jama. 2005 Jan 5;293(1):90–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.1.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hou J, Wang S, Shang YC, Chong ZZ, Maiese K. Erythropoietin Employs Cell Longevity Pathways of SIRT1 to Foster Endothelial Vascular Integrity During Oxidant Stress. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2011 Aug 1;8(3):220–35. doi: 10.2174/156720211796558069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chang ZY, Yeh MK, Chiang CH, Chen YH, Lu DW. Erythropoietin protects adult retinal ganglion cells against NMDA-, trophic factor withdrawal-, and TNF-alpha-induced damage. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e55291. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kang J, Yun JY, Hur J, Kang JA, Choi JI, Ko SB, et al. Erythropoietin Priming Improves the Vasculogenic Potential of G-CSF mobilized Human Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells. Cardiovasc Res. 2014 Jul 31; doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvu180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kwon MS, Kim MH, Kim SH, Park KD, Yoo SH, Oh IU, et al. Erythropoietin exerts cell protective effect by activating PI3K/Akt and MAPK pathways in C6 Cells. Neurol Res. 2014 Mar;36(3):215–23. doi: 10.1179/1743132813Y.0000000284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang GB, Ni YL, Zhou XP, Zhang WF. The AKT/mTOR pathway mediates neuronal protective effects of erythropoietin in sepsis. Mol Cell Biochem. 2014 Jan;385(1–2):125–32. doi: 10.1007/s11010-013-1821-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nakazawa Y, Nishino T, Obata Y, Nakazawa M, Furusu A, Abe K, et al. Recombinant human erythropoietin attenuates renal tubulointerstitial injury in murine adriamycin-induced nephropathy. J Nephrol. 2013 May-Jun;26(3):527–33. doi: 10.5301/jn.5000178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chong ZZ, Maiese K. Erythropoietin involves the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway, 14-3-3 protein and FOXO3a nuclear trafficking to preserve endothelial cell integrity. Br J Pharmacol. 2007 Apr;150(7):839–50. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chong ZZ, Shang YC, Wang S, Maiese K. PRAS40 Is an Integral Regulatory Component of Erythropoietin mTOR Signaling and Cytoprotection. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(9):e45456. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mao W, Iwai C, Liu J, Sheu SS, Fu M, Liang CS. Darbepoetin alfa exerts a cardioprotective effect in autoimmune cardiomyopathy via reduction of ER stress and activation of the PI3K/Akt and STAT3 pathways. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008 Aug;45(2):250–60. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wu Y, Shang Y, Sun S, Liu R. Antioxidant effect of erythropoietin on 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium-induced neurotoxicity in PC12 cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007 Jun 14;564(1–3):47–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ramalingam M, Kim SJ. The role of insulin against hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative damages in differentiated SH-SY5Y cells. Journal of receptor and signal transduction research. 2014 Jan 24; doi: 10.3109/10799893.2013.876043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chen A, Xiong LJ, Tong Y, Mao M. Neuroprotective effect of brain-derived neurotrophic factor mediated by autophagy through the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. Molecular medicine reports. 2013 Oct;8(4):1011–6. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2013.1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lee SJ, Seo BR, Choi EJ, Koh JY. The role of reciprocal activation of cAbl and Mst1 in the Oxidative death of cultured astrocytes. Glia. 2014 Apr;62(4):639–48. doi: 10.1002/glia.22631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Li S, Dong G, Moschidis A, Ortiz J, Benakanakere MR, Kinane DF, et al. P. gingivalis modulates keratinocytes through FOXO transcription factors. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e78541. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Maiese K, Chong ZZ, Shang YC. OutFOXOing disease and disability: the therapeutic potential of targeting FoxO proteins. Trends Mol Med. 2008 May;14(5):219–27. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Maiese K, Chong ZZ, Shang YC, Hou J. A “FOXO” in sight: targeting Foxo proteins from conception to cancer. Med Res Rev. 2009 May;29(3):395–418. doi: 10.1002/med.20139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ozel Turkcu U, Solak Tekin N, Gokdogan Edgunlu T, Karakas Celik S, Oner S. The association of FOXO3A gene polymorphisms with serum FOXO3A levels and oxidative stress markers in vitiligo patients. Gene. 2014 Feb 15;536(1):129–34. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.11.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Puthanveetil P, Wan A, Rodrigues B. FoxO1 is crucial for sustaining cardiomyocyte metabolism and cell survival. Cardiovasc Res. 2013 Mar 1;97(3):393–403. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Qi XF, Li YJ, Chen ZY, Kim SK, Lee KJ, Cai DQ. Involvement of the FoxO3a pathway in the ischemia/reperfusion injury of cardiac microvascular endothelial cells. Experimental and molecular pathology. 2013 Oct;95(2):242–7. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Scodelaro Bilbao P, Boland R. Extracellular ATP regulates FoxO family of transcription factors and cell cycle progression through PI3K/Akt in MCF-7 cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013 Oct;1830(10):4456–69. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Shang YC, Chong ZZ, Hou J, Maiese K. The forkhead transcription factor FoxO3a controls microglial inflammatory activation and eventual apoptotic injury through caspase 3. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2009 Feb;6(1):20–31. doi: 10.2174/156720209787466064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Dong S, Kang S, Gu TL, Kardar S, Fu H, Lonial S, et al. 14-3-3 integrates prosurvival signals mediated by the AKT and MAPK pathways in ZNF198-FGFR1-transformed hematopoietic cells. Blood. 2007 Jul 1;110(1):360–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-065615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hong YK, Lee S, Park SH, Lee JH, Han SY, Kim ST, et al. Inhibition of JNK/dFOXO pathway and caspases rescues neurological impairments in Drosophila Alzheimer’s disease model. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012 Mar 2;419(1):49–53. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.01.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hou J, Chong ZZ, Shang YC, Maiese K. FoxO3a governs early and late apoptotic endothelial programs during elevated glucose through mitochondrial and caspase signaling. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010 Mar 4;321(2):194–206. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2010.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hou J, Chong ZZ, Shang YC, Maiese K. Early apoptotic vascular signaling is determined by Sirt1 through nuclear shuttling, forkhead trafficking, bad, and mitochondrial caspase activation. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2010 May;7(2):95–112. doi: 10.2174/156720210791184899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kaushal N, Hegde S, Lumadue J, Paulson RF, Prabhu KS. The regulation of erythropoiesis by selenium in mice. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011 Apr 15;14(8):1403–12. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mahajan SG, Fender AC, Meyer-Kirchrath J, Kurt M, Barth M, Sagban TA, et al. A novel function of FoxO transcription factors in thrombin-stimulated vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. Thromb Haemost. 2012 Jul 3;108(1):148–58. doi: 10.1160/TH11-11-0756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Rong Z, Pan R, Xu Y, Zhang C, Cao Y, Liu D. Hesperidin pretreatment protects hypoxia-ischemic brain injury in neonatal rat. Neuroscience. 2013 Dec 26;255:292–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Su L, Liu X, Chai N, Lv L, Wang R, Li X, et al. The transcription factor FOXO4 is down-regulated and inhibits tumor proliferation and metastasis in gastric cancer. BMC Cancer. 2014 May 28;14(1):378. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Trinh DL, Scott DW, Morin RD, Mendez-Lago M, An J, Jones SJ, et al. Analysis of FOXO1 mutations in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2013 May 2;121(18):3666–74. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-01-479865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Bagul PK, Banerjee SK. Insulin resistance, oxidative stress and cardiovascular complications: role of sirtuins. Curr Pharm Des. 2013;19(32):5663–77. doi: 10.2174/13816128113199990372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Chong ZZ, Shang YC, Wang S, Maiese K. SIRT1: New avenues of discovery for disorders of oxidative stress. Expert opinion on therapeutic targets. 2012 Feb;16(2):167–78. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2012.648926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Chong ZZ, Wang S, Shang YC, Maiese K. Targeting cardiovascular disease with novel SIRT1 pathways. Future Cardiol. 2012 Jan;8(1):89–100. doi: 10.2217/fca.11.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kilic U, Gok O, Bacaksiz A, Izmirli M, Elibol-Can B, Uysal O. SIRT1 Gene Polymorphisms Affect the Protein Expression in Cardiovascular Diseases. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e90428. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ng F, Tang BL. When is Sirt1 activity bad for dying neurons? Frontiers in cellular neuroscience. 2013;7:186. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2013.00186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zheng W. Sirtuins as emerging anti-parasitic targets. European journal of medicinal chemistry. 2013 Jan;59:132–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Balaiya S, Ferguson LR, Chalam KV. Evaluation of sirtuin role in neuroprotection of retinal ganglion cells in hypoxia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53(7):4315–22. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-9259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Balan V, Miller GS, Kaplun L, Balan K, Chong ZZ, Li F, et al. Life span extension and neuronal cell protection by Drosophila nicotinamidase. J Biol Chem. 2008 Oct 10;283(41):27810–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804681200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Banerjee KK, Ayyub C, Ali SZ, Mandot V, Prasad NG, Kolthur-Seetharam U. dSir2 in the adult fat body, but not in muscles, regulates life span in a diet-dependent manner. Cell reports. 2012 Dec 27;2(6):1485–91. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Canto C, Houtkooper RH, Pirinen E, Youn DY, Oosterveer MH, Cen Y, et al. The NAD(+) Precursor Nicotinamide Riboside Enhances Oxidative Metabolism and Protects against High-Fat Diet-Induced Obesity. Cell Metab. 2012 Jun 6;15(6):838–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Duan W. Sirtuins: from metabolic regulation to brain aging. Frontiers in aging neuroscience. 2013;5:36. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2013.00036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Chong ZZ, Lin SH, Li F, Maiese K. The sirtuin inhibitor nicotinamide enhances neuronal cell survival during acute anoxic injury through Akt, Bad, PARP, and mitochondrial associated “anti-apoptotic” pathways. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2005 Oct;2(4):271–85. doi: 10.2174/156720205774322584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Yang Y, Duan W, Li Y, Jin Z, Yan J, Yu S, et al. Novel role of silent information regulator 1 in myocardial ischemia. Circulation. 2013 Nov 12;128(20):2232–40. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.002480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Zhang J, Feng X, Wu J, Xu H, Li G, Zhu D, et al. Neuroprotective effects of resveratrol on damages of mouse cortical neurons induced by beta-amyloid through activation of SIRT1/Akt1 pathway. BioFactors (Oxford, England) 2013 Oct 17; doi: 10.1002/biof.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Halperin-Sheinfeld M, Gertler A, Okun E, Sredni B, Cohen HY. The Tellurium compound, AS101, increases SIRT1 level and activity and prevents type 2 diabetes. Aging (Albany NY) 2012 Jul;4(6):436–47. doi: 10.18632/aging.100468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Maiese K, Chong ZZ, Shang YC, Wang S. Novel directions for diabetes mellitus drug discovery. Expert opinion on drug discovery. 2013 Jan;8(1):35–48. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2013.736485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Shao S, Yang Y, Yuan G, Zhang M, Yu X. Signaling molecules involved in lipid-induced pancreatic Beta-cell dysfunction. Dna Cell Biol. 2013 Feb;32(2):41–9. doi: 10.1089/dna.2012.1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Jang SY, Kang HT, Hwang ES. Nicotinamide-induced mitophagy: event mediated by high NAD+/NADH ratio and SIRT1 protein activation. J Biol Chem. 2012 Jun 1;287(23):19304–14. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.363747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Li J, Feng L, Xing Y, Wang Y, Du L, Xu C, et al. Radioprotective and antioxidant effect of resveratrol in hippocampus by activating sirt1. International journal of molecular sciences. 2014;15(4):5928–39. doi: 10.3390/ijms15045928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Lim JH, Kim EN, Kim MY, Chung S, Shin SJ, Kim HW, et al. Age-associated molecular changes in the kidney in aged mice. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2012;2012:171383. doi: 10.1155/2012/171383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Pang WJ, Xiong Y, Wang Y, Tong Q, Yang GS. Sirt1 attenuates camptothecin-induced apoptosis through caspase-3 pathway in porcine preadipocytes. Exp Cell Res. 2013 Mar 10;319(5):670–83. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2012.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Lai CS, Tsai ML, Badmaev V, Jimenez M, Ho CT, Pan MH. Xanthigen suppresses preadipocyte differentiation and adipogenesis through down-regulation of PPARgamma and C/EBPs and modulation of SIRT-1, AMPK, and FoxO pathways. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry. 2012 Feb 1;60(4):1094–101. doi: 10.1021/jf204862d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Shi J, Yin N, Xuan LL, Yao CS, Meng AM, Hou Q. Vam3, a derivative of resveratrol, attenuates cigarette smoke-induced autophagy. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2012 Jul;33(7):888–96. doi: 10.1038/aps.2012.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Wang F, Chan CH, Chen K, Guan X, Lin HK, Tong Q. Deacetylation of FOXO3 by SIRT1 or SIRT2 leads to Skp2-mediated FOXO3 ubiquitination and degradation. Oncogene. 2012 Mar 22;31(12):1546–57. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Wang W, Yan C, Zhang J, Lin R, Lin Q, Yang L, et al. SIRT1 inhibits TNF-alpha-induced apoptosis of vascular adventitial fibroblasts partly through the deacetylation of FoxO1. Apoptosis. 2013 Jun;18(6):689–701. doi: 10.1007/s10495-013-0833-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Kozako T, Aikawa A, Shoji T, Fujimoto T, Yoshimitsu M, Shirasawa S, et al. High expression of the longevity gene product SIRT1 and apoptosis induction by sirtinol in adult T-cell leukemia cells. Int J Cancer. 2012 Nov 1;131(9):2044–55. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Knight JR, Allison SJ, Milner J. Active regulator of SIRT1 is required for cancer cell survival but not for SIRT1 activity. Open biology. 2013 Nov;3(11):130130. doi: 10.1098/rsob.130130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Zhang JG, Zhao G, Qin Q, Wang B, Liu L, Liu Y, et al. Nicotinamide prohibits proliferation and enhances chemosensitivity of pancreatic cancer cells through deregulating SIRT1 and Ras/Akt pathways. Pancreatology : official journal of the International Association of Pancreatology (IAP) [et al] 2013 Mar-Apr;13(2):140–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Sansone L, Reali V, Pellegrini L, Villanova L, Aventaggiato M, Marfe G, et al. SIRT1 silencing confers neuroprotection through IGF-1 pathway activation. J Cell Physiol. 2013 Aug;228(8):1754–61. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Barbieri F, Albertelli M, Grillo F, Mohamed A, Saveanu A, Barlier A, et al. Neuroendocrine tumors: insights into innovative therapeutic options and rational development of targeted therapies. Drug Discov Today. 2014 Apr;19(4):458–68. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2013.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Maiese K. Cutting through the Complexities of mTOR for the Treatment of Stroke. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2014 Apr 7; doi: 10.2174/1567202611666140408104831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Maiese K. Taking aim at Alzheimer’s disease through the mammalian target of rapamycin. Ann Med. 2014 Aug 8;:1–10. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2014.941921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Martinez de Morentin PB, Martinez-Sanchez N, Roa J, Ferno J, Nogueiras R, Tena-Sempere M, et al. Hypothalamic mTOR: the rookie energy sensor. Curr Mol Med. 2014 Jan;14(1):3–21. doi: 10.2174/1566524013666131118103706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Wang C, Yu JT, Miao D, Wu ZC, Tan MS, Tan L. Targeting the mTOR Signaling Network for Alzheimer’s Disease Therapy. Mol Neurobiol. 2014 Feb;49(1):120–35. doi: 10.1007/s12035-013-8505-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Chong ZZ, Shang YC, Wang S, Maiese K. Shedding new light on neurodegenerative diseases through the mammalian target of rapamycin. Prog Neurobiol. 2012 Aug 15;99(2):128–48. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Maiese K, Chong ZZ, Shang YC, Wang S. mTOR: on target for novel therapeutic strategies in the nervous system. Trends Mol Med. 2013 Jan;19(1):51–60. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, Sengupta S, Sheen JH, Hsu PP, Bagley AF, et al. Prolonged rapamycin treatment inhibits mTORC2 assembly and Akt/PKB. Mol Cell. 2006 Apr 21;22(2):159–68. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Chong ZZ, Li F, Maiese K. The pro-survival pathways of mTOR and protein kinase B target glycogen synthase kinase-3beta and nuclear factor-kappaB to foster endogenous microglial cell protection. Int J Mol Med. 2007 Feb;19(2):263–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Ji YF, Zhou L, Xie YJ, Xu SM, Zhu J, Teng P, et al. Upregulation of glutamate transporter GLT-1 by mTOR-Akt-NF-small ka, CyrillicB cascade in astrocytic oxygen-glucose deprivation. Glia. 2013 Dec;61(12):1959–75. doi: 10.1002/glia.22566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Koh PO. Ferulic acid attenuates focal cerebral ischemia-induced decreases in p70S6 kinase and S6 phosphorylation. Neurosci Lett. 2013 Oct 25;555:7–11. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Liu X, Chhipa RR, Nakano I, Dasgupta B. The AMPK Inhibitor Compound C Is a Potent AMPK-Independent Antiglioma Agent. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014 Mar;13(3):596–605. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Maiese K. Therapeutic targets for cancer: current concepts with PI 3-K, Akt, & mTOR. The Indian journal of medical research. 2013 Feb;137(2):243–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Noseda R, Belin S, Piguet F, Vaccari I, Scarlino S, Brambilla P, et al. DDIT4/REDD1/RTP801 is a novel negative regulator of Schwann cell myelination. J Neurosci. 2013 Sep 18;33(38):15295–305. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2408-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Xie R, Wang P, Ji X, Zhao H. Ischemic post-conditioning facilitates brain recovery after stroke by promoting Akt/mTOR activity in nude rats. J Neurochem. 2013 Dec;127(5):723–32. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Xiong X, Xie R, Zhang H, Gu L, Xie W, Cheng M, et al. PRAS40 plays a pivotal role in protecting against stroke by linking the Akt and mTOR pathways. Neurobiol Dis. 2014 Feb 27; doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.You H, Li T, Zhang J, Lei Q, Tao X, Xie P, et al. Reduction in Ischemic Cerebral Infarction is Mediated through Golgi Phosphoprotein 3 and Akt/mTOR Signaling following Salvianolate Administration. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2014 Mar 7; doi: 10.2174/1567202611666140307124857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Zhou W, Dong L, Wang N, Shi JY, Yang JJ, Zuo ZY, et al. Akt Mediates GSK-3beta Phosphorylation in the Rat Prefrontal Cortex during the Process of Ketamine Exerting Rapid Antidepressant Actions. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2014;21(4):183–8. doi: 10.1159/000356517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Zhu Z, Yan J, Jiang W, Yao XG, Chen J, Chen L, et al. Arctigenin effectively ameliorates memory impairment in Alzheimer’s disease model mice targeting both beta-amyloid production and clearance. J Neurosci. 2013 Aug 7;33(32):13138–49. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4790-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Hwang SK, Kim HH. The functions of mTOR in ischemic diseases. BMB Rep. 2011 Aug;44(8):506–11. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2011.44.8.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Potter CJ, Pedraza LG, Xu T. Akt regulates growth by directly phosphorylating Tsc2. Nat Cell Biol. 2002 Sep;4(9):658–65. doi: 10.1038/ncb840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Shang YC, Chong ZZ, Wang S, Maiese K. Tuberous sclerosis protein 2 (TSC2) modulates CCN4 cytoprotection during apoptotic amyloid toxicity in microglia. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2013 Feb;10(1):29–38. doi: 10.2174/156720213804806007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Carayol N, Vakana E, Sassano A, Kaur S, Goussetis DJ, Glaser H, et al. Critical roles for mTORC2- and rapamycin-insensitive mTORC1-complexes in growth and survival of BCR-ABL-expressing leukemic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010 Jul 13;107(28):12469–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005114107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Bonapace L, Bornhauser BC, Schmitz M, Cario G, Ziegler U, Niggli FK, et al. Induction of autophagy-dependent necroptosis is required for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells to overcome glucocorticoid resistance. J Clin Invest. 2010 Apr;120(4):1310–23. doi: 10.1172/JCI39987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Case N, Ma M, Sen B, Xie Z, Gross TS, Rubin J. Beta-catenin levels influence rapid mechanical responses in osteoblasts. J Biol Chem. 2008 Oct 24;283(43):29196–205. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801907200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Yang M, Zhao X, Liu Y, Tian Y, Ran X, Jiang Y. A role for WNT1-inducible signaling protein-1 in airway remodeling in a rat asthma model. International immunopharmacology. 2013 Oct;17(2):350–7. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2013.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Reddy VS, Valente AJ, Delafontaine P, Chandrasekar B. Interleukin-18/WNT1-inducible signaling pathway protein-1 signaling mediates human saphenous vein smooth muscle cell proliferation. J Cell Physiol. 2011 Dec;226(12):3303–15. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Chong ZZ, Li F, Maiese K. Group I Metabotropic Receptor Neuroprotection Requires Akt and Its Substrates that Govern FOXO3a, Bim, and beta-Catenin During Oxidative Stress. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2006 May;3(2):107–17. doi: 10.2174/156720206776875830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Maiese K. The Many Facets of Cell Injury: Angiogenesis to Autophagy. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2012 Apr 19;9(2):1–2. doi: 10.2174/156720212800410911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Mercer KE, Hennings L, Sharma N, Lai K, Cleves MA, Wynne RA, et al. Alcohol consumption promotes diethylnitrosamine-induced hepatocarcinogenesis in male mice through activation of the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway. Cancer prevention research (Philadelphia, Pa) 2014 Jul;7(7):675–85. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-13-0444-T. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Zemans RL, McClendon J, Aschner Y, Briones N, Young SK, Lau LF, et al. Role of beta-catenin-regulated CCN matricellular proteins in epithelial repair after inflammatory lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2013 Mar 15;304(6):L415–27. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00180.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Wang H, Zhang R, Wen S, McCafferty DM, Beck PL, MacNaughton WK. Nitric oxide increases Wnt-induced secreted protein-1 (WISP-1/CCN4) expression and function in colitis. Journal of molecular medicine (Berlin, Germany) 2009 Apr;87(4):435–45. doi: 10.1007/s00109-009-0445-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Xu L, Corcoran RB, Welsh JW, Pennica D, Levine AJ. WISP-1 is a Wnt-1- and beta-catenin-responsive oncogene. Genes Dev. 2000 Mar 1;14(5):585–95. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Schneider S, Kloimstein P, Pammer J, Brannath W, Grasl M, Erovic BM. New diagnostic markers in salivary gland tumors. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology : official journal of the European Federation of Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Societies (EUFOS) : affiliated with the German Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology - Head and Neck Surgery. 2014 Jul;271(7):1999–2007. doi: 10.1007/s00405-013-2740-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]