Summary

Wild birds harbor a large gene pool of influenza A viruses that have the potential to cause influenza pandemics. Foreseeing and understanding this potential is important for effective surveillance. Our phylogenetic and geographic analyses revealed the global prevalence of avian influenza virus genes whose proteins differ only a few amino acids from the 1918 pandemic influenza virus, suggesting that 1918-like pandemic viruses may emerge in the future. To assess this risk, we generated and characterized a virus composed of avian influenza viral segments with high homology to the 1918 virus. This virus exhibited higher pathogenicity in mice and ferrets than an authentic avian influenza virus. Further, acquisition of seven amino acid substitutions in the viral polymerases and the hemagglutinin surface glycoprotein conferred respiratory droplet transmission to the 1918-like avian virus in ferrets, demonstrating that contemporary avian influenza viruses with 1918 virus-like proteins may have pandemic potential.

Introduction

Despite having conquered many infectious diseases, we continue to face a threat from novel, previously unrecognized infectious diseases. Most of these so-called ‘emerging infectious diseases’ are caused by zoonotic pathogens that originate in animals (Jones et al., 2008; Taylor et al., 2001). These pathogens are responsible for various human diseases, such as AIDS, SARS, and pandemic influenza. Animal-origin pathogens must overcome an immense hurdle to cause a zoonosis, that is, interspecies transmission from natural or intermediate hosts to humans. If such pathogens acquire the ability to transmit among humans, they become an appreciable threat to mankind.

The 1918 influenza pandemic, the most devastating disease outbreak recorded, killed an estimated 40–50 million people worldwide (Johnson and Mueller, 2002; Taubenberger and Morens, 2006). Sequence analyses identified the 1918 pandemic strain as an H1N1 influenza A virus of avian origin, although this conclusion remains controversial (Rabadan et al., 2006; Reid et al., 2004; Smith et al., 2009). Since avian species harbor a large influenza virus gene pool that may contain influenza viral segments encoding proteins with high homology to the 1918 viral proteins (designated as ‘1918 virus-like virus proteins’), the possibility exists for a 1918 virus-like avian virus to emerge in the human population as a pandemic virus; however, the likelihood of such an event remains unknown. To assess the risk of emergence of pandemic influenza viruses reminiscent of the 1918 influenza virus, we examined the properties of influenza viruses composed of avian influenza viral segments that encode proteins with high homology to the 1918 viral proteins (designated as ‘1918-like avian viruses’), which we generated by using reverse genetics.

Results

Generation of a 1918-like avian virus possessing avian influenza viral segments that encode proteins with high homology to the 1918 viral proteins

We first determined whether influenza A virus gene segments exist in the avian influenza virus gene pool that encode proteins with high homology to the 1918 viral proteins. We focused on amino acid sequence comparisons because our goal was to identify avian influenza viral proteins that closely resemble 1918 virus proteins in structure and function, and may therefore allow the emergence of a 1918-like virus. To this end, we performed a sequence similarity search using BLAST (blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) to identify the closest relatives to the 1918 viral proteins. Interestingly, for most viral proteins (except for HA, NA, and PB1-F2), we found avian influenza virus proteins that differed by only a limited number of amino acids from their 1918 counterparts (Table S1). For example, for PB2, we found one avian influenza PB2 protein that differed by 8 amino acids from 1918 PB2. Similarly, we found avian influenza PB1, PA, NP, M1, M2, NS1, and NS2 proteins that closely resembled their 1918 counterparts. Most of the viruses from which these proteins were derived were isolated recently, suggesting that 95 years after the devastating 1918 pandemic, avian influenza virus genes encoding 1918-like proteins continue to circulate in nature. For the 1918 HA and NA proteins, we identified the closest avian H1 and N1 relatives, respectively. These proteins differed by 33 and 31–33 amino acids, respectively, from the 1918 proteins, a finding that was expected due to the higher evolutionary rates in these genes relative to the other influenza viral genes.

To assess the risk of emergence of a 1918-like virus and to delineate the amino acid changes that are needed for such a virus to become transmissible via respiratory droplets in mammals, we attempted to generate an influenza virus composed of avian influenza viral segments that encoded proteins with high homology to the 1918 viral proteins. In particular, we selected the following genes to generate a 1918-like avian influenza virus (referred to as 1918-like avian virus) (see Supplemental Experimental Procedures): the PB2 segment of A/blue-winged teal/Ohio/926/2002 (H3N8), the PB1 segment of A/blue-winged teal/Alberta/286/77 (H3N6), the PA segment of A/pintail duck/ALB/219/77 (H1N1), the NP segment of A/blue-winged teal/Ohio/908/2002 (H1N1), the M segment of A/duck/Germany/113/95 (H9N2), the NS segment of A/canvasback duck/Alberta/102/76 (H3N6), the HA segment of A/duck/ALB/238/79 (H1N1), and the NA segment of A/mallard/duck/Alberta/46/77 (H1N1) as described in the Supplemental Results. The resulting virus differs by 8 (PB2), 6 (PB1), 20 (PB1-F2), 9 (PA), 7 (NP), 33 (HA), 31 (NA), 1 (M1), 5 (M2), 4 (NS1), and 0 (NS2) amino acids from the 1918 virus.

The 1918-like avian virus possessing these eight 1918-like avian viral segments was successfully recovered from 293T cells transfected with the plasmids required to generate this virus. The virus grew well in Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells and embryonated chicken eggs (8.3 ± 0.1 and 8.6 ± 0.2 log10 plaque forming units (PFU)/ml at 24 h post-infection, respectively) and its growth was comparable to that of the 1918 virus (8.8 ± 0.1 and 8.4 ± 0.2 log10 PFU/ml in MDCK cells and eggs, respectively, at 24 h post-infection).

The 1918-like avian virus exhibits intermediate pathogenicity compared with the 1918 virus and an authentic avian virus in mouse and ferret models

To assess the pathogenicity of the 1918-like avian virus, we first determined the mouse lethal dose 50 (MLD50; the dose required to kill 50% of infected mice) values of the 1918-like avian influenza virus and authentic 1918 virus. As a control for the authentic avian influenza virus, we used A/duck/Alberta/35/76 (H1N1; DK/ALB) because this avian strain was well-characterized in a previous study (Van Hoeven et al., 2009). The 1918-like avian influenza virus showed intermediate pathogenicity (with an MLD50 of 5.5 log10 PFU) compared with DK/ALB (with an MLD50 of 6.8 log10 PFU) and the 1918 virus (with an MLD50 of 2.7 log10 PFU). These data indicate that the avian influenza virus genes that were selected because of their close relationship with 1918 virus proteins not only cooperate at a functional level, but also support pathogenicity higher than that of an authentic avian influenza virus.

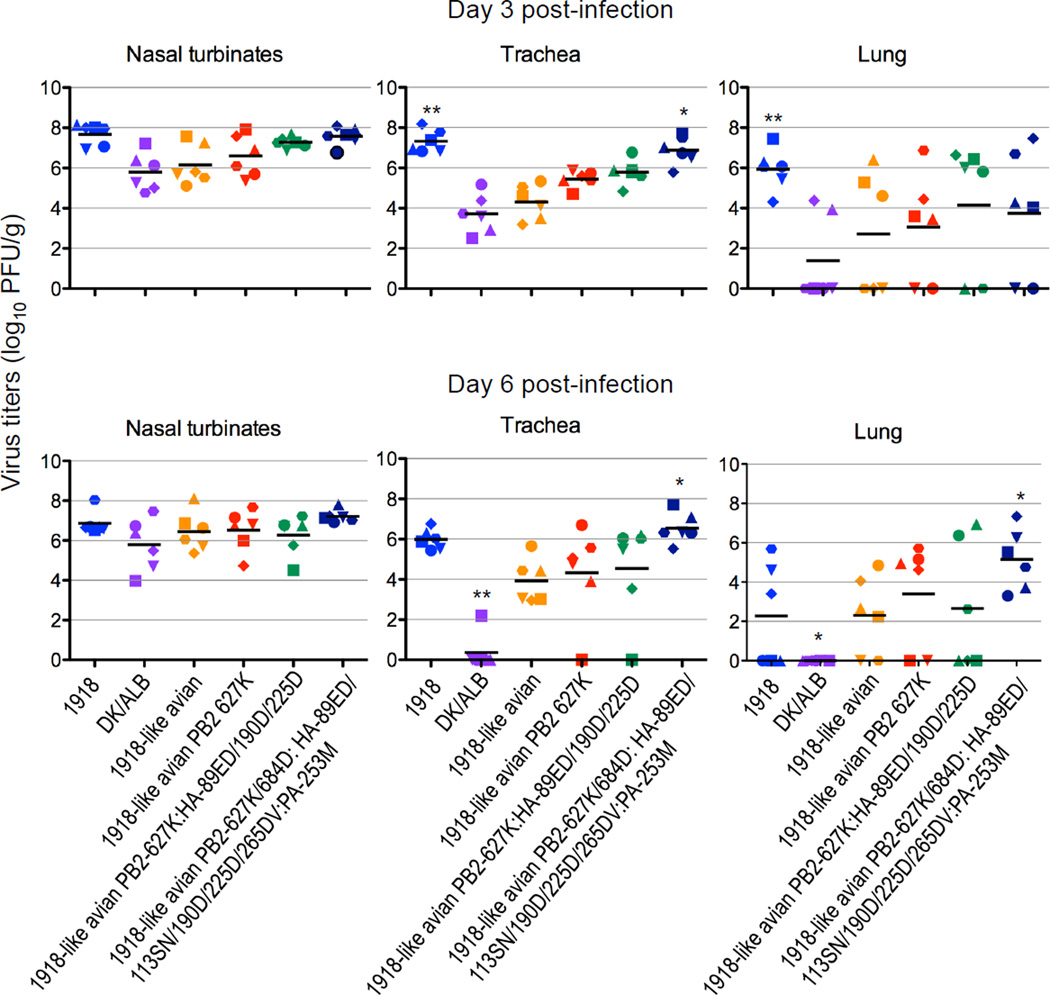

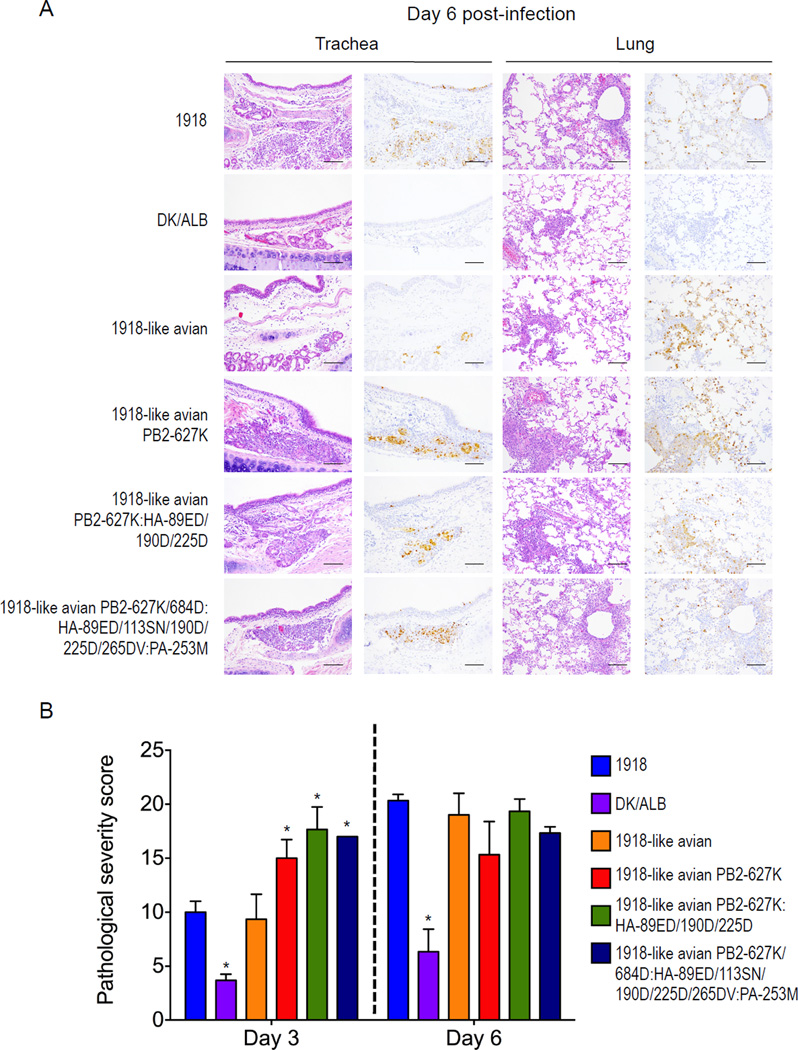

The ferret is considered the best current model for influenza virus infection because infected animals exhibit symptoms that resemble those of humans infected with influenza A virus. Therefore, we next tested the pathogenicity of the 1918-like avian virus in ferrets. Ferrets (3 animals per group) were intranasally inoculated with 106 PFU/500 µl of the 1918-like avian virus, the 1918 virus, or DK/ALB virus (Fig. S1). All animals infected with the 1918 virus became symptomatic; their body weights declined drastically (the mean maximum body weight loss was 17.5 ± 2.2%) and one of them died on day 8 post-infection (Fig. S1A). By contrast, none of the ferrets infected with DK/ALB exhibited noticeable clinical signs (no appreciable body weight loss in any of the animals; Fig. S1C), whereas animals infected with the 1918-like avian virus became symptomatic and showed substantial body weight loss (the mean maximum body weight loss was 11.9 ± 3.9%, see Table 1 and Fig. S1B). Of the three viruses tested, the 1918 virus replicated the most efficiently in the upper and lower respiratory tract (p < 0.01; Fig. 1 and Table S2). The 1918- and 1918-like avian virus-infected ferrets displayed numerous viral antigen-positive cells in tracheal, bronchial, bronchiolar, and glandular epithelial cells and necrotized changes in some trachea-bronchial glands on day 6 post-infection (Fig. 2A), whereas the 1918-like avian virus-infected ferrets presented few antigen-positive cells on day 3 post-infection (Fig. S2). In the lungs, no significant differences in pathologic changes were detected between the 1918 and 1918-like avian virus groups (Fig. 2A and B, and Fig. S2). In contrast, the DK/ALB infection caused only minimal-to-mild bronchitis or bronchiolitis with little viral antigen expression on days 3 and 6 postinfection (Fig. 2A and B, and Fig. S2). Taken together with the results of recent studies that showed no appreciable clinical signs in ferrets infected with more commonplace avian influenza viruses of various subtypes (Kocer et al., 2012; Watanabe et al., 2013), the finding that the 1918-like avian influenza virus is of intermediate pathogenicity in mammals may suggest that the progenitor of the 1918 virus was an unusual avian influenza virus whose pathogenicity in mammals was higher than that of most avian influenza viruses.

Table 1.

Pathogenicity and transmissibility of reassortants and mutants of 1918-like avian virus in ferretsa.

| Virus-inoculated ferrets |

Contact ferrets |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight loss (%)b |

Survival (No. of dead/total) |

Virus detection in nasal wash (positive and total numbers) |

Seroconversion (positive and total numbers)c |

|

| 1918 | 17.5 ± 2.2 | 1/3 | 2 of 3 | 2 of 3 |

| 1918-like aviand | 11.9 ± 3.9 | 0/3 | 0 of 3 | 0 of 3 |

| DK/ALB | 1.9 ± 3.3 | 0/3 | 0 of 3 | 0 of 3 |

| 1918 PB2/Avian | 17.8 ± 2.2 | 0/3 | 0 of 3 | 0 of 3 |

| 1918 HA/Avian | 16.9 ± 5.8 | 2/3 | 0 of 3 | 0 of 3 |

| 1918 PB2:HA/Avian | 18.7 ± 4.0 | 2/3 | 0 of 3 | 0 of 3 |

| 1918 PB2:HA:NA/Avian | 18.6 ± 3.7 | 0/3 | 2 of 3 | 2 of 3 |

| 1918(3P+NP):HA/Avian | 21.2 ± 4.4 | 2/3 | 1 of 3 | 1 of 3 |

| 1918-like avian PB2-627K |

10.3 ± 3.6 | 0/3 | 0 of 3 | 0 of 3 |

| 1918-like avian PB2-627K HA-89ED/190D/225D |

19.4 ± 9.2 | 1/3 | 1 of 3 | 1 of 3 |

| 1918-like avian PB2-627K/684D: HA-89ED/113SN /190D/225D/265DV: PA-253M |

21.0 ± 5.1 | 0/3 | 2 of 3 | 2 of 3 |

For each pair of ferrets, one animal was intranasally inoculated with 106 PFU of virus (0.5 ml) (virus-inoculated ferret) and one day later, a naïve ferret was placed in an adjacent cage (contact ferret). Virus-inoculated ferrets were monitored for 14 days to determine survival rates and body weight changes.

Maximum percentage weight loss (mean ± standard deviation) is shown.

Serum samples were collected 18 days after infection; HI assays were carried out with homologous virus and turkey red blood cells.

The 1918-like avian virus possessing the avian influenza viral segments that encoded proteins with high homology to the 1918 viral proteins described in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures was generated by using reverse genetics. The effectiveness of current vaccines and antiviral drugs against the 1918-like avian virus was examined (see Tables S4 and S5). See also Figs. S1 and S3, and Table S3.

Fig. 1. Replicative ability of 1918 virus, an authentic avian virus, 1918-like avian virus, and 1918-like avian mutant viruses.

Virus replication in respiratory organs of ferrets. Ferrets were intranasally infected with 106 PFU of virus. Six animals per group were euthanized on days 3 and 6 post-infection for virus titration. Virus titers in nasal turbinates, tracheae, and lungs were determined by plaque assay in MDCK cells. Horizontal bars indicate the mean virus titers. Asterisks indicate virus titers significantly different from those of the 1918-like avian virus (, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01). See also Table S2.

Fig. 2. Pathological analyses of 1918 virus, an authentic avian virus, 1918-like avian virus, and 1918-like avian mutant viruses.

(A) Histopathological findings in virus-infected ferrets. Shown are representative pathological changes in tracheae and lungs of ferrets infected with 106 PFU of the indicated viruses on day 6 post-infection. Three ferrets per group were infected intranasally with 106 PFU of virus, and tissues were collected on day 6 after infection for pathological examination. No virus was detected from the lungs of the DK/ALB-infected ferrets. Left panel, hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining. Right panel, immunohistochemical staining for influenza viral antigen (NP). Scale bars indicate 100 µm. (B) Pathological severity scores for infected ferrets. To represent comprehensive histological changes, respiratory tissue slides were evaluated by scoring pathological changes as described in Supplemental Experimental Procedures. The sum of the pathologic scores for all 5 lung lobes was calculated for each ferret. The means ± standard deviations from three ferrets are shown. Asterisks indicate virus pathological scores significantly different from that of the 1918-like avian virus (Dunnett’s test; p < 0.05). See also Fig. S2.

The 1918 PB2 and HA genes contribute to enhanced pathogenicity and transmissibility in ferrets

To identify the 1918 viral segments that are responsible for the intermediate pathogenicity of the 1918-like avian virus relative to the 1918 and authentic avian viruses, we examined the pathogenicity of reassortant viruses possessing 1918 viral genes in the genetic background of the 1918-like avian virus in ferrets. We focused on the HA and PB2 genes, which are known to play important roles in the adaptation of avian influenza viruses to mammals (Hatta et al., 2001; Li et al., 2005; Matrosovich et al., 2008; Neumann and Kawaoka, 2006; Subbarao et al., 1993). We generated 1918 PB2/Avian, 1918 HA/Avian, and 1918 PB2:HA/Avian viruses, which possess the PB2, HA, or PB2 and HA genes of the 1918 virus, respectively, and the remaining genes from the 1918-like avian virus (Fig. S3). We also created 1918 PB2:HA:NA/Avian and 1918(3P+NP):HA/Avian viruses, which possess the 1918 virus PB2, HA, and NA genes, or the 1918 virus PA, PB1, PB2, NP, and HA genes, respectively, and the remaining genes from the 1918-like avian virus (Fig. S3). All animals infected with these viruses became symptomatic; they lost appetite and body weight (Table 1 and Fig. S1). Two of three ferrets died upon infection with the 1918 HA/Avian, 1918 PB2:HA/Avian, and 1918(3P+NP):HA/Avian viruses (Table 1). In the ferret tracheae, the mean virus titers of all reassortant viruses possessing the 1918 PB2 gene or the 1918 HA gene were higher than that of the 1918-like avian virus on day 3 post-infection (Table S2), although these differences were not statistically significant. These results suggest that the 1918 PB2 and HA genes confer high pathogenicity to the 1918-like avian virus in the ferret model.

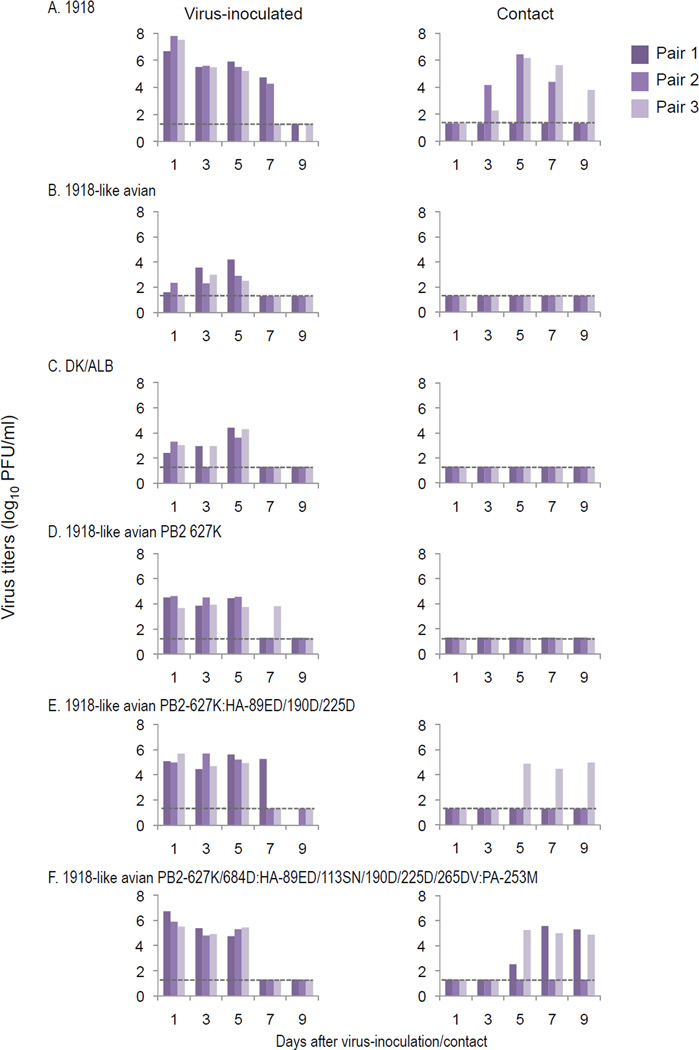

For an influenza virus to cause a pandemic, it must achieve efficient human-to-human transmission. Therefore, we tested transmissibility in ferrets of the authentic 1918 virus, as well as the 1918-like avian virus and its reassortants. Three animals were each intranasally inoculated with 106 PFU of virus. One day after infection, a naïve ferret was housed in a cage adjacent to each of the infected ferrets. This setup prevented direct contact between animals but allowed the spread of influenza virus through respiratory droplets. Viral titers were determined in nasal washes collected from both the inoculated and contact ferrets every other day post-infection/contact (for up to 9 days). The 1918 virus was recovered from two of the three contact ferrets (Fig. 3A), demonstrating respiratory droplet transmission of the 1918 virus. In contrast, the 1918-like avian and DK/ALB viruses failed to transmit among ferrets; no virus was detected in nasal washes collected from contact animals, although the inoculated animals did shed virus (Fig. 3B and C). Similarly, no virus was recovered from contact animals for the 1918 PB2/Avian, 1918 HA/Avian, and 1918 PB2:HA/Avian virus groups (Fig. S4A, B, and C). However, virus was recovered from one of the three contact animals in the 1918(3P+NP):HA/Avian and two of three contact ferrets in the 1918 PB2:HA:NA/Avian virus group (Fig. S4D and E), suggesting potential roles for the RNA replication complex, HA, and NA in virus transmission among ferrets. Taken together, our data suggest that the 1918 PB2 and HA genes confer enhanced pathogenicity and transmissibility to the 1918-like avian virus in ferrets.

Fig. 3. Respiratory droplet transmission in ferrets.

Groups of three ferrets were infected intranasally with 106 PFU of the indicated viruses. One day later, a naïve ferret (contact ferret) was placed in a cage adjacent to each infected ferret. Nasal washes were collected from infected ferrets on day 1 after inoculation and from contact ferrets on day 1 after co-housing, and then every other day (for up to 9 days) for virus titration. The lower limit of detection is indicated by the horizontal dashed line. See also Fig. S4 and Table S3.

Identification of amino acid substitutions potentially associated with the efficient transmission of the 1918-like avian virus in ferrets

HA and PB2 are known to play important roles in restricting viral transmission from avian species to humans (Van Hoeven et al., 2009). The receptor-binding specificity of the HA protein is a major determinant of influenza viral host range (Matrosovich et al., 2008). Glu-to-Asp and Gly-to-Asp mutations at positions 190 and 225 of HA (H3 numbering), respectively, are essential for avian virus HAs of the H1 subtype to bind to human-type receptors (Matrosovich et al., 2000). In addition, Lys at position 627 of the PB2 protein is important for avian viruses to efficiently replicate in mammalian cells and at the lower temperatures of the upper human airway (Hatta et al., 2001; Hatta et al., 2007; Subbarao et al., 1993). To test whether these mammalian-adapting mutations in HA and PB2 affect the replicative ability, pathogenicity, and transmissibility of the 1918-like avian virus, we attempted to generate mutant 1918-like reassortant avian viruses possessing these amino acid substitutions (i.e., 1918-like avian PB2–627K, and 1918-like avian PB2–627K:HA-190D/225D viruses). 1918-like avian PB2–627K virus was generated upon inoculation of the supernatant of transfected 293T cells into embryonated chicken eggs (Fig. S3). We were unable to generate 1918-like avian PB2–627K:HA-190D/225D virus in embryonated chicken eggs, but were able to obtain this virus after propagation of 293T cell supernatant in MDCK cells. However, this virus consisted of a mixed virus population possessing E or D at position 89 of HA (89ED) in addition to the PB2–627K and HA-190D/225D mutations (designated as ‘1918-like avian PB2–627K:HA-89ED/190D/225D’; Fig. S3 and Table 2). These mutant viruses replicated well in the nasal turbinates and tracheal tissues of ferrets (Fig. 1 and Table S2). Infection of ferrets with 1918-like avian PB2–627K and 1918-like avian PB2–627K:HA-89ED/190D/225D caused substantial body weight loss (10.3 ± 3.6% and 19.4 ± 9.2%, respectively; Table 1) and appreciable pathologic changes in the trachea and lungs of the infected animals (Fig. 2A and Fig. S2). We tested the transmissibility of these viruses and found that no virus was recovered from contact ferrets for the 1918-like avian PB2–627K virus group. Interestingly, for the 1918-like avian PB2–627K:HA-89ED/190D/225D virus group, virus and seroconversion were detected for one of the three contact ferrets (Table 1, Fig. 3E, Fig. S4F and Table S3), indicating its partial transmissibility in this animal model.

Table 2.

Amino acid changes in viral proteins acquired during the transmission of 1918-like avian viruses in ferrets.

| Amino acid sequence and position |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HAa |

PB2 |

PA |

NP |

||||||||

| 89 | 113 | 187 | 190 | 225 | 265 | 627 | 684 | 253 | 232 | ||

| 1918 b | E | S | T | D | D | G | K | A | V | T | |

| 1918-like avian b | E | S | I | E | G | D | E | A | V | T | |

| 1918-like avian PB2- 627K:HA- 89ED/190D/225D c |

E/De | S | I | D | D | D | K | A | V | T | |

| 1918-like avian PB2- 627K/684D:HA- 89ED/113SN/190D/225D: PA253M d |

E/De | S/Ne | I | D | D | D | K | D | M | T | |

| 1918-like avian PB2- 627K/684D:HA89ED/ 113SN/190D/225D/265DV :PA253M f |

E/De | S/Ne | I | D | D | D/Ve | K | D | M | T | |

| Pair 1 | Inoculated | E/De | S/Ne | I/Te | D | D | D/Ve | K | D | M | T |

| Contact | E/De | S | T | D | D | V | K | D | M | T | |

| Pair 3 | Inoculated | E/De | S/Ne | I | D | D | D/Ve | K | D | M | T |

| Contact | E/De | N | I | D | D | D | K | D | M | I | |

Amino acid positions of HA are based on H3 HA numbering.

The stock of this egg-grown virus was sequenced.

The stock of this MDCK-grown virus was sequenced.

Virus isolated from the nasal washes of the contact ferret in this 1918-like avian PB2-627K:HA-89ED/190D/225D virus group was sequenced.

Indicates a mixed population.

Virus isolated from the nasal washes of the contact ferret in this 1918-like avian PB2-627K:HA-89ED/190D/225D virus group was propagated in MDCK cells and the resulting virus stock was sequenced.

See also Figs. S3 and S4.

We sequenced the virus isolated on days 5 and 9 post-contact from the nasal washes of the contact ferret in the 1918-like avian PB2–627K:HA-89ED/190D/225D virus group and found three additional mutations, HA-S113N, PB2-A684D, and PA-V253M (Table 2). After propagating this virus in MDCK cells, the virus stock possessed the following mutations: PB2–627K, PB2–684D, PA-253M, HA-190D, HA-225D, HA-89E/D, HA-113S/N, and HA-265D/V (the mixed populations of amino acids were found at positions 89, 113, and 265) (designated as ‘1918-like avian PB2–627K/684D:HA-89ED/113SN/190D/225D/265DV:PA-253M’) (Table 2 and Fig. S3).

The 1918-like avian PB2–627K/684D:HA-89ED/113SN/190D/225D /265DV:PA-253M virus replicated more efficiently in trachea and lungs than did the 1918-like avian virus (p < 0.05; Fig. 1 and Table S2) and caused severe weight loss in the infected ferrets (maximum body weight loss was 21.0 ± 5.1%) although no infected animals died (Table 1). The 1918-like avian PB2–627K/684D:HA-89ED/113SN/190D/225D/265DV:PA-253M infection caused more progressive inflammation in the lungs of ferrets on day 3 post-infection compared with that caused by the 1918-like avian virus (Dunnett’s test; p <0.05; Fig. 2B and Fig. S2). The ferrets infected with this mutant virus presented numerous viral antigen-positive cells in tracheal, bronchial, bronchiolar, and glandular epithelial cells both on days 3 and 6 post-infections (Fig. 2A and Fig. S2). We then tested the transmissibility of this virus and found that two of the three contact ferrets were positive for virus between days 5 and 9 after contact; these animals were also seropositive (Fig. 3F, Fig. S4F and Table S3). Sequence analysis showed that the virus recovered from the contact animal for pair 1 possessed an additional I-to-T amino acid substitution at position 187 of HA (Table 2), which is located at the receptor-binding site of HA (Fig. 4A). For the pair 3 contact ferret, the recovered virus possessed an additional T-to-I mutation at position 232 of NP (Table 2). Taken together, our results demonstrate that ten amino acid substitutions (E627K and A684D in PB2; E89D, S113N, I187T, E190D, G225D, and D265V in HA; V253M in PA; and T232I in NP) may be associated with efficient 1918-like avian virus transmission in ferrets.

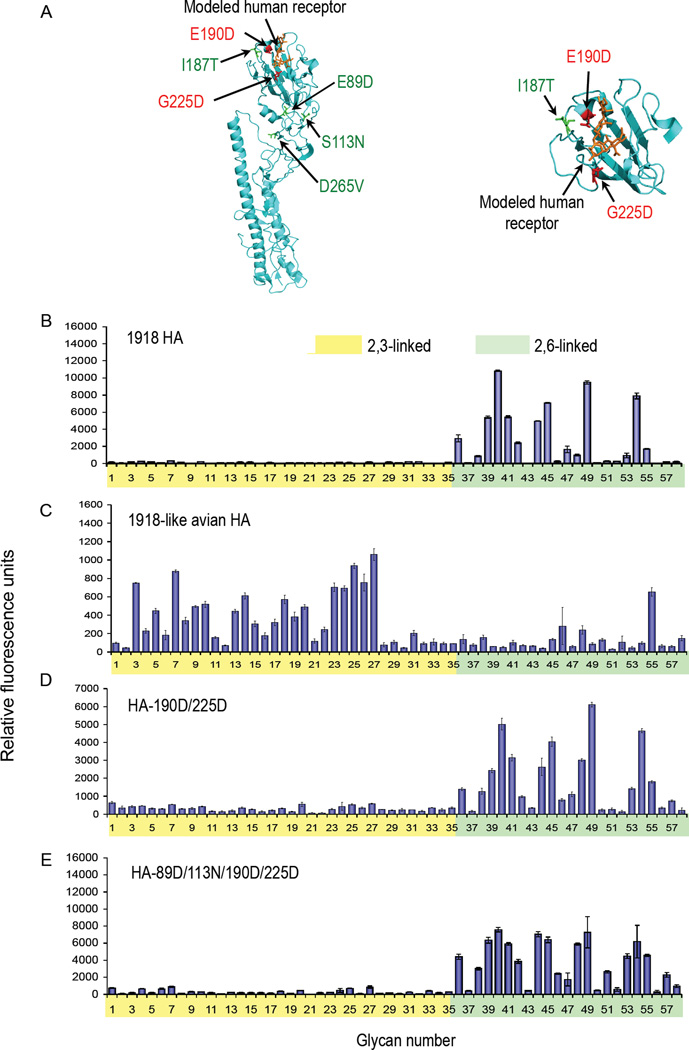

Fig. 4. HA structural analysis and glycan microarray analysis.

(A) Localization of amino acid changes identified in viruses recovered from ferrets in the transmission study. Shown is the three-dimensional structure of the monomer of A/Brevig Mission/1/18 (H1N1) HA in complex with human receptor analogues [Protein Data Bank (PDB) code, 2WRG]. A close-up view of the globular head is also shown to the right. Mutations known to increase affinity to human-type receptors are shown in red (E190D and G225D). Mutations that emerged in HA during replication and/or transmission in ferrets are shown in green (E89D, S113N, I187T, and D265V). The amino acid changes at positions 89 and 113 are located close to an amino acid at position 110 (103 with H5 numbering) that was previously found to be associated with the transmissibility of an H5 virus (Herfst et al., 2012). Images were created with MacPymol [http://www.pymol.org/]. (B–E) The receptor specificities of viruses possessing 1918 HA (B), 1918-like avian HA (C), 1918-like avian HA-190D/225D (D), and 1918-like avian HA-89D/113N/190D/225D (E) were assessed by using a glycan microarray containing a diverse library of α2–3 and α2–6 sialosides (Xu et al., 2013). Viruses, directly labeled with biotin, were applied at 128 hemagglutination units/ml for 1 h, and, after washing, were incubated with Streptavidin-AlexaFluor647 (1 µg/ml) for 1 h to detect bound virus. Error bars represent the standard deviation calculated from 6 replicate spots of each glycan. A complete list of glycans is found in Table S6. See also Fig. S5.

The effects of amino acid changes in the HA of the transmissible 1918-like avian viruses on receptor-binding specificity and HA stability

To better understand the molecular mechanisms behind the enhanced replicative ability and transmissibility of 1918-like avian virus carrying HA and PB2 with the amino acid substitutions found in the transmissible 1918-like avian viruses, we examined the effects of these amino acid changes on the functions of HA and the viral polymerases. First, we conducted a glycan microarray to examine the receptor specificity of the 1918-like avian virus HA possessing human-type amino acid substitutions. For this experiment, we used reassortant viruses possessing HA segments derived from 1918, DK/ALB, 1918-like avian HA-190D/225D, 1918-like avian HA-89D/190D/225D, or 1918-like avian HA-89D/113N/190D/225D virus, their NA segment from 1918-like avian virus, and their remaining genes from A/Puerto Rico/8/34 (H1N1; PR8); however, the 1918-like avian virus HA and NA genes were tested in the background of 1918-like avian virus since these genes could not be rescued in the background of PR8. The 1918 HA bound to α2,6-linked sialosides (human-type receptor) (Fig. 4B), whereas the 1918-like avian (Fig. 4C) and DK/ALB (Fig. S5A) HAs bound to α2,3-linked sialosides (avian-type receptor). As reported previously (Chutinimitkul et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2010; Matrosovich et al., 2000; Watanabe et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2010), Gly residues at positions 190 and 225 of HA can confer binding to avian-type receptors, whereas Asp residues at these positions confer binding to human-type receptors. Indeed, the 1918-like avian mutant HAs possessing Asp at positions 190 and 225 efficiently bound to α2,6Gal-sialylated glycans (human-type receptor) (Fig. 4D). In addition, mutant HA possessing the additional mutations found in the virus recovered from the contact ferret infected with transmitted 1918-like avian PB2–627K:HA-89ED/190D/225D virus (i.e., HA-89D and −113N) also bound to the human-type receptor (Fig. 4E and Fig. S5B). The 1918-like avian mutant HAs exhibited remarkably similar glycan-binding specificity. For HAs possessing the E-to-D change at position 89 (i.e., HA-89D/113N/190D/225D and HA-89D/190D/225D), there was weak binding to glycan #51 that was not detected with HA-190D/225D (Fig. 4 and Fig. S5), however, the biological significance is currently unknown.

In addition to receptor binding, another critical function of HA is membrane fusion. A recent study showed a difference between transmissible and non-transmissible viruses in the pH at which HA is activated for fusion (de Vries et al., 2014; Imai et al., 2012). Therefore, we next examined HA fusion activity under different pH conditions by testing the polykaryon formation efficiency of HeLa cells expressing 1918 HA, the 1918-like avian HA, the 1918-like avian mutant HAs, or DK/ALB HA (Fig. S5C). The 1918-like avian HA induced membrane fusion at pH 5.3 or below, whereas membrane fusion was observed at pH 5.6 or below in the cells expressing 1918 or DK/ALB HA (Fig. S5C). None of the amino acid changes at positions 89, 113, 190, or 225 affected the fusion pH of the 1918-like avian HA (i.e., the pH values at which HA was activated was pH 5.3) (Fig. S5C), suggesting that the amino acid changes found in the HA of the 1918-like avian transmissible mutant have no effect on the pH at which fusion of the 1918-like avian HA is activated.

Our previous studies demonstrated that H5 transmissible mutants exhibit considerable tolerance to high temperature compared with a non-transmissible H5 mutant, suggesting a role for HA stabilization in efficient replication and transmission in ferrets (de Vries et al., 2014; Imai et al., 2012). Therefore, we next tested whether the identified amino acid changes in HA affect its heat stability. For this experiment, we used the same set of recombinant viruses that were used in the glycan array described earlier. We tested the loss of hemagglutination activity and infectivity after incubation at 50°C for various times (Fig. S5D, E). Introduction of the 190D/225D mutation into 1918-like HA resulted in faster loss of hemagglutination activity, whereas the additional introduction of the HA-89D or HA-89D/113N mutation reversed this trend (Fig. S5D). The HA-190D/225D virus lost its infectivity rapidly after a 180-min incubation at 50°C (6.8-log10 decrease in virus titers; Fig. S5E), whereas the HA-89D/190D/225D and the HA-89D/113N/190D/225D viruses were more tolerant of high temperature (3.7- and 4.2-log10 decreases in virus titers under the same conditions, respectively; Fig. S5E). These results suggest that mutations critical for human-type receptor binding (i.e., HA-190D/225D) reduced HA stability, which was restored by additional mutations associated with respiratory droplet transmissibility (i.e., HA-89D and HA-89D/113N). This trend (i.e., loss of HA stability due to mutations conferring human virus receptor recognition and recovery of HA stability by the acquisition of an additional mutation) is consistent with our previous findings (de Vries et al., 2014; Imai et al., 2012). However, the HA heat stability of 1918 HA, as evaluated by hemagglutination activity, was similar to that of the HA-190D/225D virus (Fig. S5D), indicating complex interplay among receptor binding-specificity, HA stability, and virus transmissibility in ferrets.

The effects of amino acid changes in the viral RNA polymerase complex of the transmissible 1918-like avian viruses on polymerase activity

The viral polymerase complex affects viral replicative ability and pathogenicity (de Vries et al., 2014; Gabriel et al., 2008; Hatta et al., 2001; Li et al., 2005; Subbarao et al., 1993). To determine whether amino acid changes in PA and/or PB2 affect the viral polymerase activity of the 1918-like avian virus, we conducted a luciferase activity-based minireplicon assay in human 293T cells as described previously (Ozawa et al., 2007). The polymerase activity of the 1918 polymerase complex was significantly greater than that of the 1918-like avian polymerase complex at 33°C and 37°C (Fig. S5F, p < 0.05). The PB2–627K mutation strongly increased the polymerase activity of the 1918-like avian polymerase complex (p < 0.05), whereas neither PB2–684D nor PA-253M appreciably affected the polymerase activity (Fig. S5F). These findings suggest that only the PB2–627K mutation contributes to the enhanced polymerase activity.

The effectiveness of current vaccines and antiviral drugs against the 1918-like avian virus

From a biosafety perspective, it is important to know whether current control measures (vaccines and antiviral drugs) are effective against the 1918-like avian virus. We therefore examined the reactivity of sera from humans vaccinated with the current influenza vaccine, which includes A/California/04/2009 (H1N1), against the 1918-like avian virus and its mutants. The HI test results revealed that these sera reacted poorly with 1918-like avian virus, that is, to the same extent as the negative control virus A/mallard/Gurjev/263/82 (H14N5), which possess an HA that is antigenically distant from that of the current vaccine strains (Table S4). In contrast, the sera reacted robustly with the 1918 virus and the mutant 1918-like avian viruses that possessed additional mutations associated with respiratory droplet transmissibility (i.e., the 1918-like avian PB2–627K:HA-89ED/190D/225D and 1918-like avian PB2–627K/684D:HA-89ED/113SN/190D/225D/265DV:PA-253M viruses), although the HI titers against the 1918-related viruses were substantially lower than those against the homologous strain (i.e., A/California/04/2009) (Table S4). Given that the amino acids at positions 190 and 225 are located close to the antigenic sites of HA, the amino acid substitutions at these positions may alter the antigenicity of the 1918-like avian virus. We next examined the oseltamivir sensitivity of our test viruses. A previous study showed that 1918 virus was highly susceptible to the NA inhibitor oseltamivir (Tumpey et al., 2002). The IC50 [half maximal (50%) inhibitory concentration] value of the 1918 like-avian virus (<10 nM) was similar to that of the 1918 virus and that of A/Kawasaki/UT-K25/2008 (H1N1; an oseltamivir-sensitive control; Table S5). In contrast, the IC50 values of the oseltamivir-resistant controls, A/Kawasaki/IMS22B-955/2003 (H3N2) and A/Osaka/180/2009 (H1N1), were 34,600 and 1,360 nM, respectively (Table S5). Because all of the viruses tested in this study possess the NA gene from either the 1918 virus or the 1918-like avian virus, these viruses should be highly susceptible to oseltamivir, so appropriate control measures would be available to combat the 1918-like avian virus used in this study.

Global distribution and evolution of 1918-like avian viruses

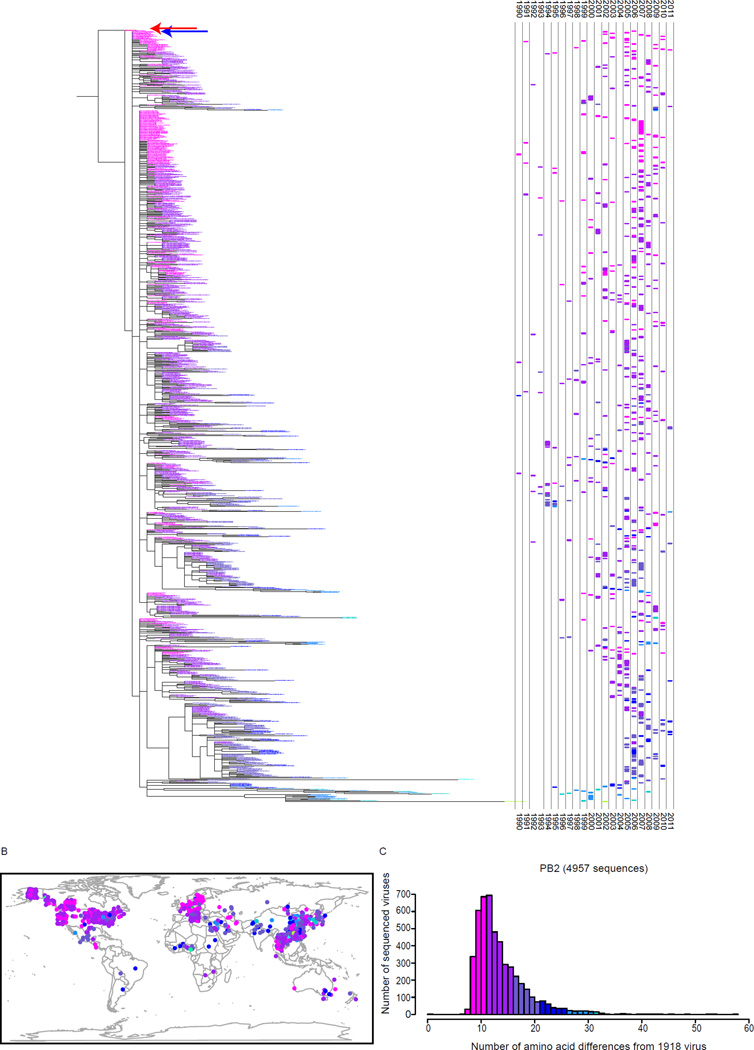

Wild birds harboring a large pool of influenza A virus genomes facilitate the global spread of viruses. Here, we experimentally demonstrated that an avian influenza virus encoding proteins with high homology to the 1918 viral proteins and possessing a limited number of additional mutations exhibited relatively high pathogenicity in mammals and transmissibility between ferrets (Fig. 3 and Table 1), suggesting its potential to cause a pandemic. To assess the risk of the emergence of such avian influenza viruses, we examined the prevalence of avian influenza viruses encoding viral proteins that differed by a few amino acids from the 1918 virus proteins. We constructed phylogenetic trees, with a time-series of virus isolation (from 1990 to 2011), of amino acid sequences for each viral protein by using the 1918 viral protein as the root sequence (Fig. 5A and Fig. S6). To assess the spatial patterns and divergence of the 1918-like avian viruses, we also generated geographic maps and histograms to show the distribution of the amino acid differences from their respective 1918 viral proteins (Fig. 5B and C, and Fig. S6). The geographic patterns of amino acid sequence similarity by gene segment showed that avian viruses encoding PB2, PB1, NP, M, and NS genes of closest similarity to those of the 1918-like avian virus have predominantly circulated in North America and Europe, with mostly sporadic circulation in other parts of the world (Fig. 5 and Fig. S6).

Fig. 5. Global patterns of PB2 proteins derived from avian influenza viruses.

(A) Phylogenetic tree of 1,022 randomly selected amino acid sequences of PB2 genes derived from avian influenza viruses. The tree was rooted to the PB2 sequence of the 1918 virus, A/Brevig Mission/1/18 (H1N1) (red arrow). The PB2 from A/blue-winged teal/Ohio/926/2002 (H3N8), which is expressed by the 1918-like avian virus, is indicated by the blue arrow. The year in which the strains were isolated is indicated by horizontal bars to the right of the tree drawn at the same vertical position as the position of the strain in the tree. The tree and time-series are color-coded according to the number of amino acid differences from the 1918 virus defined in the histogram shown in (C). (B) Geographic map indicating locations where the respective viruses shown in (A) were isolated. The map is color-coded according to the number of amino acid differences defined in the histogram shown in (C). (C) Histogram showing the distribution of the amino acid differences of all avian influenza PB2 proteins from the 1918 PB2 protein and color scheme for panels (A) and (B) (red = 0–5 amino acid substitutions; magenta = 6–10; purple =11–15; etc). See also Fig. S6 and Tables S1 and S7.

Further, we examined whether there are any avian influenza viruses possessing human-type amino acids, such as PB2–627K, HA-190D, or HA-225D. We found that 168 of 4293 avian PB2 genes (~4%) possess the PB2–627K mutation and that 142 of those 168 are from H5N1 viruses that were isolated mainly from wild and domestic birds in Europe, the Middle East, and Africa; the others are H1N1 viruses isolated from poultry in the USA (Table S7). The HA-190D mutation was found in 9 of 266 avian H1 HA sequences (about 3% of avian H1 HA genes), one which also possessed HA-225D (Table S7). Our BLAST search revealed that all of the avian viruses possessing either HA-190D or HA-225D or both probably originated from swine or human viruses that infected an avian species (Table S7).

Taken together, our results reveal the global distribution of avian influenza virus genes encoding proteins that differ by only a few amino acids from the 1918 virus proteins, and the existence of avian influenza viruses possessing human-type amino acid residues (i.e., PB2 E627K; HA E190D and G225D). Considering the fact that many of these avian influenza viruses were isolated in recent years (i.e., from 1990 to 2011), our study demonstrates the continued circulation of avian influenza viruses that possess 1918 virus-like proteins and may acquire 1918 virus-like properties.

Discussion

Here, we conducted experiments to assess the risk represented by avian influenza viral genes encoding proteins that closely resemble 1918 virus proteins that still circulate in the avian influenza viral gene pool. We found that a 1918-like avian virus exhibited higher pathogenicity in mice and ferrets than did an authentic avian virus. Moreover, we demonstrated that acquisition of only a few amino acid substitutions can confer respiratory droplet transmission to 1918-like avian influenza viruses in a ferret model, suggesting that the potential exists for a 1918-like pandemic virus to emerge at any time from the avian virus gene pool.

Generally, in experimental infections, avian influenza viruses replicate poorly in humans and vice versa (Beare and Webster, 1991; Hinshaw et al., 1984; Murphy et al., 1984; Webster et al., 1978) because host restriction constrains interspecies transmission. Recently, however, a newly emerged H7N9 avian influenza virus appeared to break this host barrier and directly infect humans in China, resulting in a total of 238 confirmed cases and 57 fatalities as of 26 Jan 2014 (unofficial statement; http://www.cidrap.umn.edu/news-perspective/2014/01/eleven-new-h7n9-cases-include-one-beijing). We and others demonstrated that H7N9 viruses isolated from Chinese patients possess human-adaptive mutations in PB2 and HA, which possibly confer efficient replication of avian influenza viruses in the upper respiratory tract of humans, and caused limited respiratory droplet transmission in ferrets (Belser et al., 2013; Richard et al., 2013; Watanabe et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2013), raising concerns about the pandemic potential of the H7N9 virus. Similarly, other avian influenza viruses, including the 1918-like avian viruses described in this study, have the potential to cause a pandemic if they acquire such human-adaptive mutations. The worst-case scenario is the emergence of a novel avian influenza virus that exhibits high pathogenicity in human, like highly pathogenic avian H5N1 viruses, and efficient transmissibility in humans, like seasonal influenza viruses. To prepare for such a scenario, it is important to understand the molecular mechanisms of pathogenicity and transmissibility of avian influenza viruses. Such information provides support for pandemic preparedness activities (vaccines and antivirals are effective control measures), demonstrates the value of continued surveillance of avian influenza viruses, and emphasizes the need for evaluation and integration of improved risk assessment measures.

Experimental Procedures

Cells and viruses

Human embryonic kidney 293T cells and Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) and in minimal essential medium (MEM) containing 5% newborn calf serum, respectively. HeLa cells were maintained in MEM containing 10% FCS. All cells were maintained at 37°C in 5% CO2.

All viruses used in this study, except for A/duck/Alberta/35/76 (H1N1; DK/ALB), were generated by using plasmid-driven reverse genetics as described in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures and a previous report (Neumann et al., 1999). Virus growth in cells and eggs was examined as described in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Experimental infection of mice and ferrets

Five- to six-week-old female BALB/c mice (Jackson laboratory, Bar Harbor, MA, USA) were used to determine MLD50 values. Under anaesthesia, four mice per group were intranasally inoculated with viruses. Body weight and survival were monitored daily for 14 days.

Five- to eight-month-old female ferrets (Triple F Farms, Sayre, PA), which were serologically negative by hemagglutination inhibition (HI) assay for currently circulating human influenza viruses, were used in this study. Under anaesthesia, six ferrets per group were intranasally inoculated with 106 PFU (0.5 ml) of viruses. Three ferrets per group were euthanized on days 3 and 6 post-infection for virological and pathological examinations. The virus titers in various organs were determined by use of plaque assays in MDCK cells. For the transmission study, pairs of ferrets were individually housed in adjacent wireframe cages (Showa Science CO., LTD, Japan) that prevented direct and indirect contact between the animals but allowed spread of influenza virus by respiratory droplets, and virus titers in nasal washes collected from each animal were determined by use of plaque assays in MDCK cells as described elsewhere (Imai et al., 2012) and in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

All experiments with mice and ferrets were performed in accordance with the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Regulations for Animal Care and Use and approved by the Animal Experiment Committee of the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Glycan arrays

Glycan array analysis was performed on a glass slide microarray containing 6 replicates of 58 diverse sialic acid-containing glycans including terminal sequences and intact N-linked and O-linked glycans found on mammalian and avian glycoproteins and glycolipids (Xu et al., 2013). Virus samples were directly labeled with biotin (Ramya et al., 2013) and then applied to the slide array; slide scanning to detect virus bound to glycans was conducted as described previously (Watanabe et al., 2013) and in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures. A complete list of glycans present on the array is provided in Table S6.

Pathological examination

Excised tissues of animal organs preserved in 10% phosphate-buffered formalin were processed for paraffin embedding and cut into 3-µm-thick sections. One section from each tissue sample was stained using a standard hematoxylin-and-eosin procedure, whereas another one was processed for immunohistological staining with a rabbit polyclonal antibody for type A influenza nucleoprotein (NP) antigen (prepared in our laboratory) that reacts comparably with all of the viruses tested in this study. Specific antigen–antibody reactions were visualized with 3,3’-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride staining by using the DAKO LSAB2 system (DAKO Cytomation, Copenhagen, Denmark). Pathological scores were determined as described in Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Serological tests

Human serum samples obtained from individuals vaccinated with the A/California/07/2009 (H1N1) hemagglutinin (HA) split vaccine in Japan were used for serological testing. Hemagglutination inhibition titers were determined as described in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures. All experiments with human sera were approved by the Research Ethics Review Committee of the Institute of Medical Science, the University of Tokyo (approval number: 21–38–1117) and the Institutional Review Board of the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Neuraminidase (NA) inhibition assay

The sensitivity of viral NA to oseltamivir carboxylate was evaluated by using an NA enzyme inhibition assay based on the methylumbelliferyl-N-acetylneuraminic acid (MUNANA) method as described in previous studies (Gubareva et al., 2001; Kiso et al., 2004) and in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Polykaryon formation assay

HeLa cells were transfected with expression plasmids expressing various HAs. Polykaryon formation was induced by exposing cells to low-pH buffer and was observed as described in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Thermostability of HA

Viruses (128 hemagglutination units in PBS) were incubated at 50°C for the times indicated. Infectivity and hemagglutination activity were determined by using plaque assays in MDCK cells and the hemagglutination assay with 0.5% turkey blood cells, respectively.

Luciferase-based minigenome assay

A luciferase-based minigenome assay was performed to examine viral polymerase activity as described previously (Ozawa et al., 2007). Briefly, 293T cells were transfected with plasmids for the expression of viral proteins PA, PB1, PB2, and NP derived from 1918-like avian virus or its mutants, and with pPolI-WSN-NA-firefly-luciferase. Plasmid pGL4.74[hRuc/TK] (Promega, Madison, WI) served as an internal control for the dual-luciferase assay. After transfection, the cells were incubated at 33°C or 37°C for 24 h, and then luciferase activity was measured with the dual-luciferase reporter system (Promega, Madison, WI) on a Glomax microplate luminometer (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed by using analysis of variance (ANOVA) in GraphPad Prism version 5.0 (GraphPad software Inc. La Jolla, CA); p-values of < 0.05 were considered significant.

Biosafety and biosecurity

All experiments with 1918-related viruses were performed in BSL3-Agriculture containment laboratories. In vitro experiments were conducted in Class II biological safety cabinets and transmission experiments were conducted in HEPA-filtered ferret isolators (Imai et al., 2012). The research program, procedures, occupational health plan, documentation, security and facilities are reviewed annually by the University of Wisconsin-Madison Responsible Official and at regular intervals by the CDC and the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) as part of the University of Wisconsin-Madison Select Agent Program. More detailed information on Biosecurity and Biosafety is described in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Phylogenetic analysis

For each viral gene segment, all nearly complete sequences from avian viruses were downloaded from the Influenza Research Database (http://www.fludb.org). These sequences were compared with the corresponding gene sequences of the 1918 virus to determine the number of amino acid sequence differences from the 1918 virus. Due to the large number of avian influenza gene sequences (n = 3,031–5,836 sequences for the PB2, PB1, PA, NP, M, and NS segments), roughly 1,000 sequences per gene were randomly selected to enable efficient phylogenetic analysis.

Phylogenetic trees for each segment were constructed with PhyML software package version 3.0 using subtree pruning and regrafting to optimize tree topology. The randomly selected subsets of amino acid sequences for each gene segment were aligned by using MAFFT (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/mafft/).

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Current circulating avian flu viruses encode proteins similar to the 1918 virus

A 1918-like virus composed of avian influenza virus segments was generated

The 1918-like virus is more pathogenic in mammals than an authentic avian flu virus

7 amino acid substitutions were sufficient to confer transmission in ferrets

Acknowledgements

We thank Kelly Moore, Naomi Fujimoto, Izumi Ishikawa and Yuko Sato for technical support. We thank Dr. Susan Watson for editing the manuscript. Several glycans in the glycan array were provided by the Consortium for Functional Glycomics (http://www.functionalglycomics.org/) funded by NIGMS grant GM62116. This work was also supported by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Public Health Service research grants, by RO1 AI080598 and R56 AI099275, by ERATO (Japan Science and Technology Agency), and by the Strategic Basic Research Programs of Japan Science and Technology Agency, Japan. CAR was supported by a University Research Fellowship from the Royal Society.

Footnotes

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Contributions

T.W., G.N. and Y.K. designed the study; T.W., G.Z., M.H., A.H., R.M., S.F., Y.T., and S.W. performed the experiments; C.A.R., D.F.B., and D.J.S. conducted phylogenetic analysis; N.N., K.T. and H.H. conducted pathologic examination; T.W., G.Z., C.A.R., N.N., M.H., R.M., S.W., M.I., G.N., H.H., J.C.P., D.J.S., and Y.K. analyzed the data; T.W., C.A.R., N.N., R.M., E.A.M., S.W., M.I., G.N., H.H., J.C.P. and Y.K. wrote the manuscript; and Y.K. oversaw the project. T.W., G.Z., C.A.R. contributed equally to this work.

References

- Beare AS, Webster RG. Replication of avian influenza viruses in humans. Arch Virol. 1991;119:37–42. doi: 10.1007/BF01314321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belser JA, Gustin KM, Pearce MB, Maines TR, Zeng H, Pappas C, Sun X, Carney PJ, Villanueva JM, Stevens J, et al. Pathogenesis and transmission of avian influenza A (H7N9) virus in ferrets and mice. Nature. 2013;501:556–559. doi: 10.1038/nature12391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chutinimitkul S, Herfst S, Steel J, Lowen AC, Ye J, van Riel D, Schrauwen EJ, Bestebroer TM, Koel B, Burke DF, et al. Virulence-associated substitution D222G in the hemagglutinin of 2009 pandemic influenza A(H1N1) virus affects receptor binding. J Virol. 2010;84:11802–11813. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01136-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries RP, Zhu X, McBride R, Rigter A, Hanson A, Zhong G, Hatta M, Xu R, Yu W, Kawaoka Y, et al. Hemagglutinin Receptor Specificity and Structural Analyses of Respiratory Droplet-Transmissible H5N1 Viruses. J Virol. 2014;88:768–773. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02690-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel G, Herwig A, Klenk HD. Interaction of polymerase subunit PB2 and NP with importin alpha1 is a determinant of host range of influenza A virus. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e11. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0040011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubareva LV, Kaiser L, Matrosovich MN, Soo-Hoo Y, Hayden FG. Selection of influenza virus mutants in experimentally infected volunteers treated with oseltamivir. J Infect Dis. 2001;183:523–531. doi: 10.1086/318537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatta M, Gao P, Halfmann P, Kawaoka Y. Molecular basis for high virulence of Hong Kong H5N1 influenza A viruses. Science. 2001;293:1840–1842. doi: 10.1126/science.1062882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatta M, Hatta Y, Kim JH, Watanabe S, Shinya K, Nguyen T, Lien PS, Le QM, Kawaoka Y. Growth of H5N1 influenza A viruses in the upper respiratory tracts of mice. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:1374–1379. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herfst S, Schrauwen EJ, Linster M, Chutinimitkul S, de Wit E, Munster VJ, Sorrell EM, Bestebroer TM, Burke DF, Smith DJ, et al. Airborne transmission of influenza A/H5N1 virus between ferrets. Science. 2012;336:1534–1541. doi: 10.1126/science.1213362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw VS, Bean WJ, Webster RG, Rehg JE, Fiorelli P, Early G, Geraci JR, St Aubin DJ. Are seals frequently infected with avian influenza viruses? J Virol. 1984;51:863–865. doi: 10.1128/jvi.51.3.863-865.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai M, Watanabe T, Hatta M, Das SC, Ozawa M, Shinya K, Zhong G, Hanson A, Katsura H, Watanabe S, et al. Experimental adaptation of an influenza H5 HA confers respiratory droplet transmission to a reassortant H5 HA/H1N1 virus in ferrets. Nature. 2012;486:420–428. doi: 10.1038/nature10831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson NP, Mueller J. Updating the accounts: global mortality of the 1918–1920 "Spanish" influenza pandemic. Bull Hist Med. 2002;76:105–115. doi: 10.1353/bhm.2002.0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones KE, Patel NG, Levy MA, Storeygard A, Balk D, Gittleman JL, Daszak P. Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature. 2008;451:990–993. doi: 10.1038/nature06536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiso M, Mitamura K, Sakai-Tagawa Y, Shiraishi K, Kawakami C, Kimura K, Hayden FG, Sugaya N, Kawaoka Y. Resistant influenza A viruses in children treated with oseltamivir: descriptive study. Lancet. 2004;364:759–765. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16934-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocer ZA, Krauss S, Stallknecht DE, Rehg JE, Webster RG. The potential of avian H1N1 influenza A viruses to replicate and cause disease in mammalian models. PLoS One. 2012;7:e41609. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Chen H, Jiao P, Deng G, Tian G, Li Y, Hoffmann E, Webster RG, Matsuoka Y, Yu K. Molecular basis of replication of duck H5N1 influenza viruses in a mammalian mouse model. J Virol. 2005;79:12058–12064. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.18.12058-12064.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Childs RA, Matrosovich T, Wharton S, Palma AS, Chai W, Daniels R, Gregory V, Uhlendorff J, Kiso M, et al. Altered receptor specificity and cell tropism of D222G haemagglutinin mutants from fatal cases of pandemic A(H1N1) 2009 influenza. J Virol. 2010;84:12069–12074. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01639-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matrosovich M, Tuzikov A, Bovin N, Gambaryan A, Klimov A, Castrucci MR, Donatelli I, Kawaoka Y. Early alterations of the receptor-binding properties of H1, H2, and H3 avian influenza virus hemagglutinins after their introduction into mammals. J Virol. 2000;74:8502–8512. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.18.8502-8512.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matrosovich MN, Gambaryan AS, Klenk H-D. In: Receptor Specificity of Influenza Viruses and Its Alteration during Interspecies Transmission. Influenza Avian, Klenk H-D, Matrosovich MN, Stech J., editors. Basel, Karger: 2008. pp. 134–155. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy BR, Buckler-White AJ, London WT, Harper J, Tierney EL, Miller NT, Reck LJ, Chanock RM, Hinshaw VS. Avian-human reassortant influenza A viruses derived by mating avian and human influenza A viruses. J Infect Dis. 1984;150:841–850. doi: 10.1093/infdis/150.6.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann G, Kawaoka Y. Host range restriction and pathogenicity in the context of influenza pandemic. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:881–886. doi: 10.3201/eid1206.051336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann G, Watanabe T, Ito H, Watanabe S, Goto H, Gao P, Hughes M, Perez DR, Donis R, Hoffmann E, et al. Generation of influenza A viruses entirely from cloned cDNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:9345–9350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.9345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozawa M, Fujii K, Muramoto Y, Yamada S, Yamayoshi S, Takada A, Goto H, Horimoto T, Kawaoka Y. Contributions of two nuclear localization signals of influenza A virus nucleoprotein to viral replication. J Virol. 2007;81:30–41. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01434-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabadan R, Levine AJ, Robins H. Comparison of avian and human influenza A viruses reveals a mutational bias on the viral genomes. J Virol. 2006;80:11887–11891. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01414-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramya TN, Weerapana E, Cravatt BF, Paulson JC. Glycoproteomics enabled by tagging sialic acid- or galactose-terminated glycans. Glycobiology. 2013;23:211–221. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cws144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid AH, Taubenberger JK, Fanning TG. Evidence of an absence: the genetic origins of the 1918 pandemic influenza virus. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:909–914. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard M, Schrauwen EJ, de Graaf M, Bestebroer TM, Spronken MI, van Boheemen S, de Meulder D, Lexmond P, Linster M, Herfst S, et al. Limited airborne transmission of H7N9 influenza A virus between ferrets. Nature. 2013;501:560–563. doi: 10.1038/nature12476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GJ, Bahl J, Vijaykrishna D, Zhang J, Poon LL, Chen H, Webster RG, Peiris JS, Guan Y. Dating the emergence of pandemic influenza viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:11709–11712. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904991106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subbarao EK, London W, Murphy BR. A single amino acid in the PB2 gene of influenza A virus is a determinant of host range. J Virol. 1993;67:1761–1764. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.4.1761-1764.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taubenberger JK, Morens DM. 1918 Influenza: the mother of all pandemics. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:15–22. doi: 10.3201/eid1201.050979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor LH, Latham SM, Woolhouse ME. Risk factors for human disease emergence. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2001;356:983–989. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2001.0888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tumpey TM, Garcia-Sastre A, Mikulasova A, Taubenberger JK, Swayne DE, Palese P, Basler CF. Existing antivirals are effective against influenza viruses with genes from the 1918 pandemic virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:13849–13854. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212519699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hoeven N, Pappas C, Belser JA, Maines TR, Zeng H, Garcia-Sastre A, Sasisekharan R, Katz JM, Tumpey TM. Human HA and polymerase subunit PB2 proteins confer transmission of an avian influenza virus through the air. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:3366–3371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813172106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe T, Kiso M, Fukuyama S, Nakajima N, Imai M, Yamada S, Murakami S, Yamayoshi S, Iwatsuki-Horimoto K, Sakoda Y, et al. Characterization of H7N9 influenza A viruses isolated from humans. Nature. 2013;501:551–555. doi: 10.1038/nature12392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe T, Shinya K, Watanabe S, Imai M, Hatta M, Li C, Wolter BF, Neumann G, Hanson A, Ozawa M, et al. Avian-type receptor-binding ability can increase influenza virus pathogenicity in macaques. J Virol. 2011;85:13195–13203. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00859-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster RG, Yakhno M, Hinshaw VS, Bean WJ, Murti KG. Intestinal influenza: replication and characterization of influenza viruses in ducks. Virology. 1978;84:268–278. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(78)90247-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu R, Krause JC, McBride R, Paulson JC, Crowe JE, Jr., Wilson IA. A recurring motif for antibody recognition of the receptor-binding site of influenza hemagglutinin. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2013;20:363–370. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Carney P, Stevens J. Structure and Receptor binding properties of a pandemic H1N1 virus hemagglutinin. PLoS Curr. 2010:RRN1152. doi: 10.1371/currents.RRN1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Shi J, Deng G, Guo J, Zeng X, He X, Kong H, Gu C, Li X, Liu J, et al. H7N9 influenza viruses are transmissible in ferrets by respiratory droplet. Science. 2013;341:410–414. doi: 10.1126/science.1240532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H, Wang D, Kelvin DJ, Li L, Zheng Z, Yoon SW, Wong SS, Farooqui A, Wang J, Banner D, et al. Infectivity, transmission, and pathology of human-isolated H7N9 influenza virus in ferrets and pigs. Science. 2013;341:183–186. doi: 10.1126/science.1239844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.