Abstract

Background

Ikaros is a DNA-binding protein that acts as master-regulator of hematopoiesis and a tumor suppressor. In thymocytes and T-cell leukemia, Ikaros negatively regulates transcription of terminal deoxynucleotide transferase (TdT), a key protein in lymphocyte differentiation. The signaling pathways that regulate Ikaros-mediated repression of TdT are unknown. Our previous work identified Casein Kinase II (CK2) and Protein Phosphatase 1 (PP1) as regulators of Ikaros DNA binding activity. Here we investigated the role of PP1 and CK2 in regulating Ikaros-mediated control of TdT expression.

Procedures

Ikaros phosphomimetic and phosphoresistant mutants and specific CK2 and PP1 inhibitors were used in combination with quantitative chromatin immunoprecipitation (qChIP) and quantitative reverse transcriptase-PCR (q RT-PCR) assays to evaluate the role of CK2 and PP1 in regulating the ability of Ikaros to bind the TdT promoter and to regulate TdT expression.

Results

We demonstrate that phosphorylation of Ikaros by pro-oncogenic CK2 decreases Ikaros binding to the promoter of the TdT gene and reduces the ability of Ikaros to repress TdT expression during thymocyte differentiation. CK2 inhibition and PP1 activity restore Ikaros DNA-binding affinity toward the TdT promoter, as well as Ikaros-mediated transcriptional repression of TdT in primary thymocytes and in leukemia.

Conclusion

These data establish that PP1 and CK2 signal transduction pathways regulate Ikaros-mediated repression of TdT in thymocytes and leukemia. These findings reveal that PP1 and CK2 have opposing effects on Ikaros-mediated repression of TdT and establish novel roles for PP1 and CK2 signaling in thymocyte differentiation and leukemia.

Keywords: leukemia, Ikaros, IKZF1, TdT, PP1, CK2

Introduction

The IKZF1 (Ikaros) gene encodes a DNA-binding protein that acts as master regulator of hematopoiesis and a tumor suppressor in leukemia [1]. The lack of Ikaros activity leads to the absence of B cells, impaired T cell differentiation and the development of leukemia in mice [1, 2]. In humans, deletion of a single Ikaros allele is associated with the development of high-risk leukemia [3] and primary immunodeficiency [3-5]. Inactivation of one IKZF1 allele occurs in at least 5% of T-ALL [6-9], although it is less common as compared to B-cell ALL (15%) [5] or BCR-ABL1 ALL and CRLF2+ Ph-like ALL (80%) [6, 10-12].

Posttranslational modifications, including phosphorylation, regulate Ikaros function [13-16]. Protein Phosphatase 1 (PP1) and Casein Kinase II (CK2) directly interact with Ikaros [14, 17]. Functional analyses show that PP1 and CK2 target the same phosphosites on the Ikaros protein and that they have opposing effects on Ikaros ability to bind and localize to pericentromeric heterochromatin in hematopoietic cells [17].

Here we report that PP1 and CK2 regulate Ikaros activity as a transcriptional repressor of the terminal deoxynucleotide transferase (TdT) gene in thymocytes and T-cell leukemia. TdT is a differentiation-associated gene whose expression is tightly regulated during B and T lymphocyte development. The expression of TdT in acute lymphoblastic leukemia is an indicator of blocked differentiation. Understanding pathways that control Ikaros activity in regulating TdT expression provides insights into their role in lymphocyte differentiation. Our data identify molecular mechanisms that control Ikaros function as a transcriptional repressor and establish a role for the PP1 and CK2 signaling pathways in T cell differentiation and leukemia.

Methods

Cells and Reagents

The murine VL3-3M2 T-cell leukemia line has been described [18]. The human 293T endothelial kidney cell line was obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). Murine thymocytes were isolated as described [19] under an Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee-approved protocol. Okadaic acid, tautomycin, and 4,5,6,7-tetrabromo-1H-benzotriazole (TBB) were purchased from Sigma. Calyculin and 5,6-dichloro-1-β-D-ribofuranosylbenzimidazole (DRB) were purchased from Calbiochem. Cells were treated with phosphatase or kinase inhibitors for 12 hrs.

Antibodies

Antibodies used to detect Ikaros and for qChIP were described previously [18].

Biochemical experiments

Nuclear extractions, Western blot, EMSA and TdT probe for EMSA were described previously [20, 21].

Plasmids, Ikaros mutants, and transfection of 293T cells were described previously [14, 17]. Primers and qRT-PCR as well as In vivo binding of Ikaros was tested by qChIP against the D' regulatory element in the TdT URE as described [19].

Results

Phosphorylation by Casein Kinase II regulates Ikaros binding to upstream regulatory elements of the TdT gene

Previous studies have shown that Ikaros is phosphorylated at multiple sites by CK2 and dephosphorylated by PP1 (Fig. 1A). Phosphorylation of Ikaros by CK2 and dephosphorylation by PP1 regulate the ability of Ikaros to bind and localize to pericentromeric heterochromatin [17]. We hypothesize that CK2 and PP1 are the primary regulators of Ikaros binding to the upstream regulatory elements (URE) of its target genes.

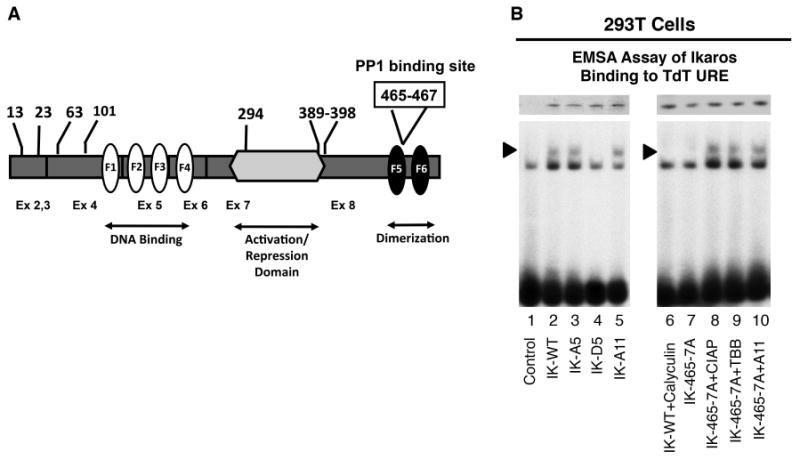

Figure 1. Phosphomimetic substitutions and the loss of PP1 interactions regulate the ability of Ikaros to bind the TdT URE.

(A) Ikaros protein map showing the location of CK2 phosphorylation and PP1 interaction sites. The phosphorylated amino acids are indicated by numbers at the top. The boxed numbers indicate the PP1 interaction site. The location of zinc fingers is indicated by white (F1-F4) and black (F5-F6) ovals. Exons (Ex) are indicated by numbers at the bottom. Exon 1 (untranslated) is not shown. (B) Nuclear extracts were prepared from 293T cells expressing wild type or mutant Ikaros (IK) proteins. Equal amounts of Ikaros proteins were used in electromobility shift assay (EMSA) as confirmed by Western blot (upper panel). Where indicated, 293Tcells were treated with calyculin (10 nM) or TBB (50 μM) (lanes 6 and 9 respectively) or CIAP, was added to the DNA binding reaction (lane 8). EMSA was performed using the TdT URE radiolabeled probe [20]. Arrow indicates Ikaros-containing complexes.

First, we tested this hypothesis in vivo in 293T cells, an embryonal kidney carcinoma cell line that does not express endogenous Ikaros. The role of phosphorylation by CK2 in regulating Ikaros DNA binding activity was studied using Ikaros mutants that mimic: 1) constitutive dephosphorylation (phosphoresistant mutants) - IK-A5 (alanine mutations at 5 phosphosites, at positions 13, 23, 63, 101, and 294 of the Ikaros protein that are phosphorylated by CK2, Fig. 1A); IK-A11 (alanine mutations at 11 phosphosites, positions 13, 23, 63, 101, 294 plus additional sites between 389 and 398 that are phosphorylated by CK2, Fig. 1A) and 2) constitutive phosphorylation (phosphomimetic mutants) IK-D5 (Aspartate mutations at the same phosphosites as the IK-5 mutant) [14, 17].

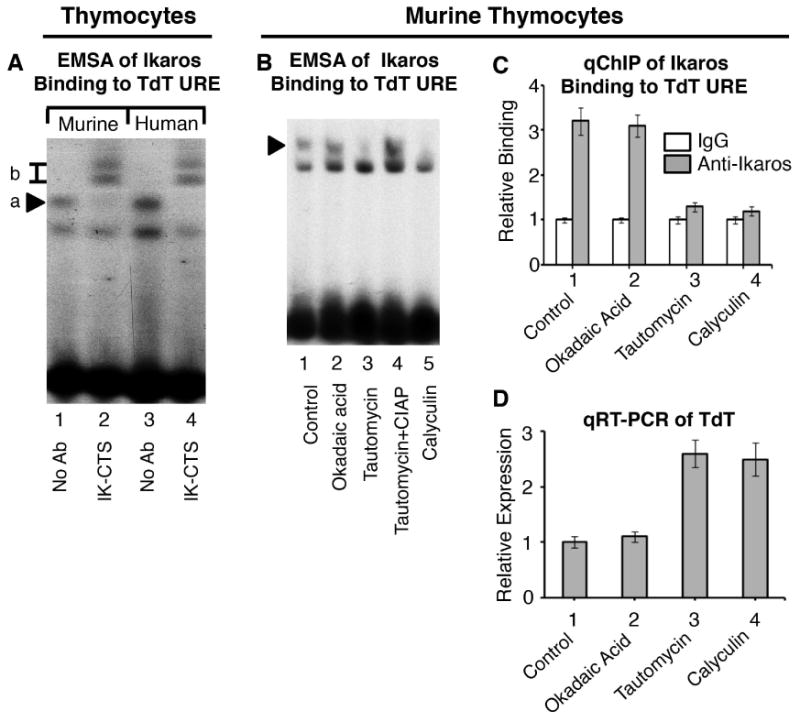

Figure 2. PP1 regulates Ikaros-mediated repression of TdT in thymocytes.

(A) Using antibodies generated against the C-terminus of the Ikaros protein (IK-CTS), as indicated below gel, EMSA was performed on nuclear extracts from murine and human thymocytes using the TdT URE probe. Ikaros-containing complexes are indicated by arrow a and supershifted complexes are indicated by box b. (B) Nuclear extracts were prepared from untreated primary murine thymocytes (lane 1), or following treatment with indicated phosphatase inhibitors (lanes 2-5). Where indicated, CIAP was added to the DNA binding reaction. EMSA was performed using radiolabeled probes derived from the TdT URE. Arrow indicates Ikaros-containing complexes. (C) qChIP analysis of Ikaros occupancy of the TdT URE in primary murine thymocytes following treatment with indicated phosphatase inhibitors. Ikaros binding (grey columns) are normalized to IgG (negative control-white columns) (D) qRT-PCR analysis of TdT expression in primary murine thymocytes treated with indicated phosphatase inhibitors.

To study the role of dephosphorylation by PP1 in regulating Ikaros function additional mutants were used. The IK-465/7A mutant (alanine substitutions at amino acids 465 and 467 that abolish Ikaros-PP1 interactions and result in Ikaros hyperphosphorylation; and the IK-465/7A+A11 mutant that cannot interact with PP1 and has phosphoresistant (alanine) mutations at the eleven CK2 phosphosites described above. Thus, this mutant cannot undergo dephosphorylation by PP1, but also cannot be phosphorylated by CK2 at 11 amino acids. 293T cells were transfected with wild-type Ikaros (IK-wt), empty vector as a negative control, or with above-described mutants. Using electromobility shift assay (EMSA), we tested the DNA binding activity of wild type and mutant Ikaros toward the URE of TdT, a known Ikaros target gene [21].

Results show that phosphoresistant Ikaros mutants bind the TdT URE with an affinity similar to that of wild type Ikaros (Fig.1B, lanes 3, 5 compared to lane 2). However, phosphomimetic Ikaros mutants, lose their ability to bind the TdT URE (Fig. 1B, lane 4). These data suggest that phosphorylation at N-terminal CK2 phosphosites reduces Ikaros DNA-binding affinity toward the TdT URE. Treatment with calyculin (an inhibitor of PP1 and PP2A phosphatases) abolishes Ikaros DNA binding to the TdT URE (Fig. 1B, lane 6). This suggests that dephosphorylation is required for Ikaros binding at the TdT URE. Mutation of Ikaros at its PP1 interaction site (the IK-465/7A mutant), resulted in a loss of Ikaros DNA binding toward the TdT URE (Fig. 1B, lane 7). However, the inhibition of CK2 with TBB, the treatment with the pan-phosphatase, calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase (CIAP), or the presence of phosphoresistant mutations at CK2 phosphosites restored Ikaros DNA binding to the TdT URE, despite the absence of Ikaros interaction with PP1 (Fig. 1B, lanes 8-10). These data suggest that PP1 regulates Ikaros DNA binding to the TdT URE by dephosphorylating CK2 phosphosites on the Ikaros protein and thus, counteracts the action of CK2. These results provide evidence that CK2 and PP1 have critical and opposing roles in the regulation of Ikaros binding to the TdT URE.

Protein phosphatase 1 regulates Ikaros-mediated repression of TdT in primary thymocytes

Next, we tested the role of PP1 in regulating Ikaros function in primary thymocytes where Ikaros is expressed abundantly [21]. Ikaros binding to the TdT URE in murine and human thymocytes was demonstrated by EMSA (Fig. 2A, lanes 1 and 3). The presence of antibodies against the C-terminal domain of Ikaros produced a supershift, providing further evidence of Ikaros binding to the TdT URE (Fig. 2A, lanes 2 and 4). Next, we tested the role of PP1 in regulating Ikaros binding to the TdT URE using EMSA (Fig. 2B). We used: 1) tautomycin, a phosphatase inhibitor with a 10-fold higher affinity toward PP1 over PP2A in concentrations (10 μM) that inhibit PP1, but not PP2A [22]; 2) okadaic acid, a phosphatase inhibitor with 100-fold higher activity against PP2A as compared to PP1 in concentration (2 nM) that is specific for PP2A [22] and 3) calyculin (10 nM), an inhibitor of both PP1 and PP2A. Results show that in untreated thymocytes, and in thymocytes treated with okadaic acid, Ikaros binds the TdT URE with a high affinity (Fig. 2B, lanes 1-2). Treatment of thymocytes with tautomycin or calyculin resulted in the loss of Ikaros binding to the TdT URE (Fig. 2B, lanes 3 and 5). Dephosphorylation of nuclear extract with calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase (CIAP), restored Ikaros binding to the TdT URE in thymocytes where PP1 activity was inhibited (Fig. 2B, lane 4). These results demonstrate that PP1, but not PP2A, is critical for Ikaros binding to the TdT URE in thymocytes.

We tested the role of PP1 in regulating Ikaros binding to the TdT URE in thymocytes using quantitative chromatin immunoprecipitation (qChIP) (Fig. 2C). Results showed that Ikaros binds the TdT URE in untreated thymocytes and following inhibition of PP2A with okadaic acid. Treatment of thymocytes with the PP1 inhibitor tautomycin or calyculin, abolishes Ikaros binding to the TdT URE. The results obtained by qChIP are consistent with data obtained using EMSA, demonstrating that PP1 regulates Ikaros binding to the TdT URE in primary thymocytes.

We tested whether the PP1 signaling pathway regulates TdT transcription in thymocytes. Okadaic acid treatment of thymocytes has a minimal effect on TdT transcription (Fig. 2D, lane 2 compared to lane 1). In contrast, the treatment of thymocytes with calyculin or tautomycin, results in elevated levels of TdT transcription as measured by quantitative Reverse-Transcriptase PCR (qRT-PCR). These results, together with data obtained using EMSA and qChIP, demonstrate that PP1 activity regulates Ikaros binding to the TdT URE, as well as TdT transcription, in primary thymocytes.

Casein Kinase II regulates Ikaros-mediated repression of TdT in thymocytes

We hypothesize that the effect of PP1 inhibition on Ikaros DNA binding to the TdT URE in thymocytes is due to Ikaros phosphorylation by CK2. To test this hypothesis, we determined whether the inhibition of CK2 could restore Ikaros ability to bind the TdT URE in the absence of PP1 activity. The PP1 inhibition in thymocytes with tautomycin abolished Ikaros binding to the TdT URE (Fig. 3A, lane 2 compared to lane 1). However, treatment of thymocytes with tautomycin and inhibitors of CK2 activity (TBB (50 μM) or DRB (50 μM), Fig. 3A, lanes 3-4) restored Ikaros binding to the TdT URE. These data suggest that the PP1 and CK2 signaling pathways regulate and have opposing effects on Ikaros binding to the TdT URE.

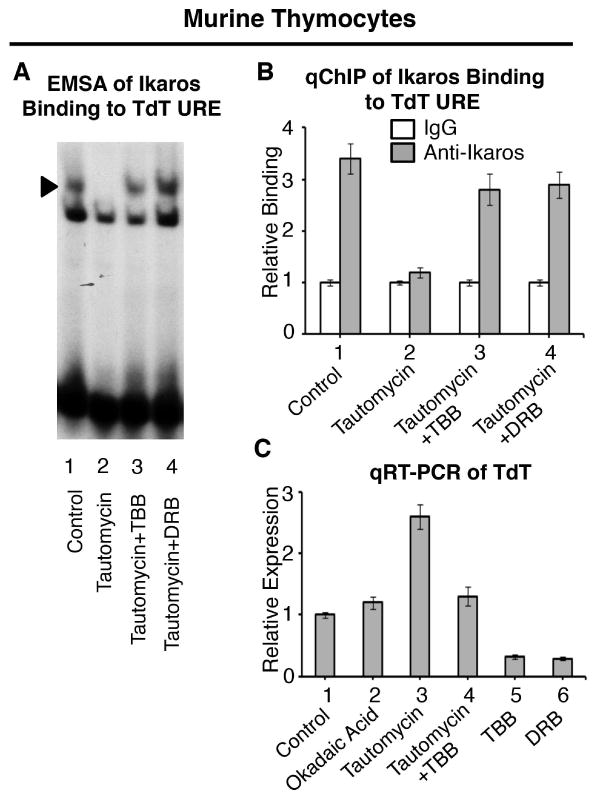

Figure 3. CK2 regulates Ikaros-mediated repression of TdT in thymocytes.

(A) Nuclear extracts were prepared from untreated primary murine thymocytes (lane 1), or following treatment with tautomycin (lanes 2-4) along with CK2 inhibitors TBB (lane 3) or DRB (lane 4). Gel shifts were performed using radiolabeled probes derived from the TdT URE. Arrow indicates Ikaros-containing complexes. (B) qChIP analysis of Ikaros occupancy of the TdT URE in untreated primary murine thymocytes or following treatment with indicated phosphatase and/or kinase inhibitors. Ikaros binding (grey columns) are normalized to IgG (negative control-white columns) (C) qRT-PCR analysis of TdT expression in untreated primary murine thymocytes or following treatment with phosphatase and/or kinase inhibitors as indicated.

The use of qChIP shows that the inhibition of CK2 activity in thymocytes with TBB or DRB restores Ikaros binding, even in the absence of PP1 activity (Fig. 3B). These results are consistent with data in Fig. 3A and confirm the importance of the PP1 and CK2 pathways in regulating Ikaros binding to the TdT URE in thymocytes.

We tested the importance of PP1 and CK2 activity for expression of TdT in thymocytes. The treatment of thymocytes with okadaic acid has minimal effect on TdT expression, while treatment with tautomycin results in the upregulation of TdT transcription (Fig. 3C, lanes 2-3 compared to lane 1). The effect of tautomycin was attenuated with the CK2 inhibitor TBB, suggesting that CK2 and PP1 signaling pathways have opposing effects on TdT transcription (Fig. 3C, lane 4). The treatment of thymocytes with CK2 inhibitors alone resulted in reduced transcription of TdT (Fig. 3C, lanes 5-6).

Overall, the results presented in Figs. 1-3 suggest that both PP1 and CK2 signaling pathways have an important role in the regulation of TdT transcription in thymocytes. The changes in the level of TdT transcription inversely correlate with Ikaros binding to the TdT URE, which suggests that the PP1 and CK2 pathways control TdT transcription in thymocytes by regulating Ikaros binding to the TdT URE.

Casein Kinase II (CK2) and Protein Phosphatase 1 (PP1) regulate Ikaros-mediated repression of TdT in T-cell leukemia

TdT is a key gene whose activity is essential for normal differentiation of lymphoid cells. The etiology of leukemia often involves impaired differentiation. Since Ikaros and PP1 act as tumor suppressors, while CK2 is a tumor promoter in hematopoietic malignancies [23], we tested whether PP1 and CK2 can regulate Ikaros-mediated repression of TdT in T-cell leukemia.

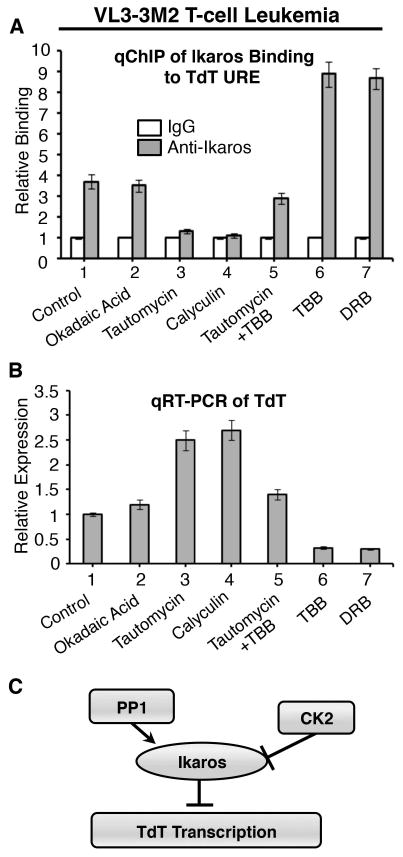

For analysis, we used VL3-3M2 cells, a murine T-cell leukemia line that expresses TdT and Ikaros [21], and has characteristics that most closely resemble primary thymocytes [19]. The role of Ikaros in the regulation of TdT has been extensively studied in these cells. Thus, the use of this established model facilitates comparisons of our results to previously published data [19]. Treatment with okadaic acid did not impair Ikaros binding to TdT URE as compared to untreated, control VL3-3M2 cells as measured by qChIP (Fig. 4A, lanes 1-2). However, treatment with tautomycin, or calyculin, resulted in the loss of Ikaros binding to the TdT URE (Fig. 4A, lanes 3-4). These results suggest that PP1 regulates Ikaros binding to TdT URE in T-cell leukemia.

Figure 4. PP1 and CK2 play opposing roles in regulating Ikaros-mediated repression of TdT in T-cell leukemia.

(A) qChIP analysis of Ikaros occupancy of the TdT URE in untreated VL3-3M2 leukemia cells or following treatment with indicated phosphatase and/or kinase inhibitors. Ikaros binding (grey columns) are normalized to IgG (negative control-white columns) (B) qRT-PCR analysis of TdT expression in untreated VL3-3M2 or following treatment with indicated phosphatase and/or kinase inhibitors. (C) Proposed model for the regulation of TdT transcription by PP1, CK2 and Ikaros. The repressor activity of Ikaros is potentiated by PP1-mediated dephosphorylation and inhibited by CK2-mediated phosphorylation.

The inhibitory effect of tautomycin on Ikaros binding to the TdT URE was alleviated when VL3-3M2 cells were simultaneously treated with both tautomycin and the CK2 inhibitor, TBB (Fig. 4A, lane 5), suggesting that CK2 inhibition enhances Ikaros binding toward the TdT URE. Treatment of VL3-3M2 cells with the CK2 inhibitors, TBB or DRB alone, showed enhanced Ikaros binding to the TdT URE (Fig. 4A, lanes 6-7). These results demonstrate that in T-cell leukemia PP1 and CK2 have opposing effects on Ikaros binding to the TdT URE that are very similar to those we observed in thymocytes.

We tested the role of PP1 and CK2 in regulating TdT transcription in T-cell leukemia. Treatment of VL3-3M2 cells with okadaic acid did not alter TdT transcription as compared to untreated VL3-3M2 cells (Fig. 4B, lanes 1-2). In contrast, treatment with tautomycin or calyculin resulted in increased transcription of TdT as measured by qRT-PCR (Fig. 4B, lanes 3-4). Dual treatment of VL3-3M2 cells with tautomycin and TBB did not significantly alter transcription of TdT (Fig. 4B, lane 5), while treatment with TBB or DRB alone resulted in repression of TdT transcription (Fig. 4B, lanes 6-7).

These results show that both PP1 and CK2 have important roles in regulating Ikaros control of TdT transcription in leukemia. Changes in the level of TdT transcription inversely correlate with Ikaros binding to the TdT URE, which suggests that PP1 and CK2 control TdT transcription in T-cell leukemia by regulating the binding of Ikaros to the TdT URE. Our results show that the roles of PP1 and CK2 in Ikaros-mediated repression of TdT are similar in T-cell leukemia and in thymocytes.

Discussion

Ikaros binds DNA at the URE of its target genes to regulate their transcription [24]. The mechanisms that regulate Ikaros activity remain largely unknown. Ikaros is abundantly expressed during the different stages of differentiation, thus, it has been hypothesized that posttranslational modifications have a large role in the regulation of Ikaros function in differentiation and as a tumor suppressor [25, 26]. Phosphorylation, sumoylation and ubiquitination regulate Ikaros DNA-binding affinity, subcellular localization, protein stability, and function in cell cycle control [13-17, 27]. However, the role of posttranslational modification in Ikaros function as a transcriptional regulator has not been established. Here we provide the first report that PP1 and CK2, two enzymes that directly interact with Ikaros, regulate its ability to control transcription of its target gene, TdT.

TdT expression in mice and humans is limited to developing T and B lymphocytes. TdT is a DNA polymerase that adds nucleotides at the sites of DNA breaks that occur during immunoglobulin and T cell receptor gene rearrangement. The non-templated nucleotides added by TdT are a major mechanism for generating diversity in antibodies and in T cell receptors [28]. The expression of TdT in T and B cell precursor ALL is a characteristic of the of blocked differentiation in these cells. The tightly controlled and differentiation-associated expression of TdT in both mice and humans make it an excellent model for studying the mechanisms that control Ikaros function in regulating lymphocyte differentiation in normal and malignant lymphocyte precursors.

The binding of Ikaros to the TdT promoter and the molecular mechanisms of Ikaros repression of TdT transcription have been studied in great detail in the mouse model. [19, 21, 29-31]. Our studies were performed on TdT in mouse cells to determine the role of Ikaros phosphorylation as well as CK2 and PP1 signaling pathways in the regulation of TdT transcription with a high level of confidence. Promoter sequences of human and murine TdT gene are highly conserved, Ikaros recognition sequences are identical and Ikaros binding to identical sites at the TdT locus have been demonstrated [29]. The use of various Ikaros mutants, in a cell system without endogenous Ikaros, and experiments on primary mouse and human thymocytes reveal a mechanism through which PP1 and CK2 regulate lymphopoiesis–via the regulation of Ikaros activity as a transcriptional repressor of TdT.

Ikaros acts as a tumor suppressor in ALL. A common mechanism of malignant transformation in hematopoietic malignancies involves altered function of genes that regulate hematopoietic differentiation. Ikaros-mediated repression of TdT is a normal step in thymocyte differentiation. Thus, optimal Ikaros activity as a transcriptional regulator of TdT is essential for normal hematopoiesis. Based on results presented in this report we propose a model for the regulation of TdT by PP1, CK2, and Ikaros in both thymocytes and leukemia (Fig. 4C).

Although the results presented here are derived from murine cells, the high homology between murine and human TdT promoters, and the evidence that Ikaros binds to both human and murine TdT promoters (Fig. 2A), suggest that these results are relevant for pediatric T-ALL and B-ALL. Additional validation of the proposed model in human cells will provide insights into the regulatory mechanisms of Ikaros tumor suppressor function. The work presented here provides a foundation for understanding of the tumor suppressor and pro-oncogenic activities of PP1 and CK2, respectively, in human leukemia.

CK2 inhibitors are emerging as targeted chemotherapeutics [32]. A novel class of CK2-specific inhibitor (CX-4945) exhibits strong anti-cancer effects in preclinical models [33, 34] and has been tested in phase I clinical trial. The presented data identifies mechanisms by which CK2 inhibitors can have therapeutic effects in leukemia – by enhancing the transcriptional repressor function of Ikaros.

In summary, we present evidence that the PP1 and CK2 pathways play a critical role in regulating Ikaros-mediated repression of TdT in both normal thymocytes and in leukemia. A critical question for future studies concerns the potential role of the PP1-CK2-Ikaros axis in regulating other Ikaros target genes. The elucidation of signaling pathways that regulate Ikaros target genes will provide important insights into the pathogenesis of leukemia and aid in the design of novel targeted treatments for this disease.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant R01 HL095120, a St. Baldrick's Foundation Career Development Award, a Hyundai Hope on Wheels Scholar Grant Award, the Four Diamonds Fund of the Pennsylvania State University, and the John Wawrynovic Leukemia Research Scholar Endowment (SD). It was also supported by NIH grant R21CA162259, by the National Institute of Health Disparities and Minority Health P20MD006988, and a St. Baldrick's Foundation Research Grant (KJP).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: None of the authors has a conflict of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Georgopoulos K, Bigby M, Wang JH, et al. The Ikaros gene is required for the development of all lymphoid lineages. Cell. 1994;79:143–156. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90407-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winandy S, Wu P, Georgopoulos K. A dominant mutation in the Ikaros gene leads to rapid development of leukemia and lymphoma. Cell. 1995;83:289–299. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90170-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mullighan CG, Su X, Zhang J, et al. Deletion of IKZF1 and prognosis in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:470–480. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldman FD, Gurel Z, Al-Zubeidi D, et al. Congenital pancytopenia and absence of B lymphocytes in a neonate with a mutation in the Ikaros gene. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;58:591–597. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mullighan CG, Goorha S, Radtke I, et al. Genome-wide analysis of genetic alterations in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nature. 2007;446:758–764. doi: 10.1038/nature05690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mullighan CG, Miller CB, Radtke I, et al. BCR-ABL1 lymphoblastic leukaemia is characterized by the deletion of Ikaros. Nature. 2008;453:110–114. doi: 10.1038/nature06866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maser RS, Choudhury B, Campbell PJ, et al. Chromosomally unstable mouse tumours have genomic alterations similar to diverse human cancers. Nature. 2007;447:966–971. doi: 10.1038/nature05886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuiper RP, Schoenmakers EF, van Reijmersdal SV, et al. High-resolution genomic profiling of childhood ALL reveals novel recurrent genetic lesions affecting pathways involved in lymphocyte differentiation and cell cycle progression. Leukemia. 2007;21:1258–1266. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marcais A, Jeannet R, Hernandez L, et al. Genetic inactivation of Ikaros is a rare event in human T-ALL. Leuk Res. 2010;34:426–429. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2009.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martinelli G, Iacobucci I, Storlazzi CT, et al. IKZF1 (Ikaros) deletions in BCR-ABL1-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia are associated with short disease-free survival and high rate of cumulative incidence of relapse: a GIMEMA AL WP report. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5202–5207. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.6408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iacobucci I, Storlazzi CT, Cilloni D, et al. Identification and molecular characterization of recurrent genomic deletions on 7p12 in the IKZF1 gene in a large cohort of BCR-ABL1-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients: on behalf of Gruppo Italiano Malattie Ematologiche dell'Adulto Acute Leukemia Working Party (GIMEMA AL WP) Blood. 2009;114:2159–2167. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-08-173963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harvey RC, Mullighan CG, Wang X, et al. Identification of novel cluster groups in pediatric high-risk B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia with gene expression profiling: correlation with genome-wide DNA copy number alterations, clinical characteristics, and outcome. Blood. 2010;116:4874–4884. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-239681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dovat S, Ronni T, Russell D, et al. A common mechanism for mitotic inactivation of C2H2 zinc finger DNA-binding domains. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2985–2990. doi: 10.1101/gad.1040502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gurel Z, Ronni T, Ho S, et al. Recruitment of ikaros to pericentromeric heterochromatin is regulated by phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:8291–8300. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707906200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gomez-del Arco P, Maki K, Georgopoulos K. Phosphorylation controls Ikaros's ability to negatively regulate the G(1)-S transition. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:2797–2807. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.7.2797-2807.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gomez-del Arco P, Koipally J, Georgopoulos K. Ikaros SUMOylation: switching out of repression. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:2688–2697. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.7.2688-2697.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Popescu M, Gurel Z, Ronni T, et al. Ikaros stability and pericentromeric localization are regulated by protein phosphatase 1. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:13869–13880. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M900209200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ronni T, Payne KJ, Ho S, et al. Human Ikaros function in activated T cells is regulated by coordinated expression of its largest isoforms. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:2538–2547. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605627200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Su RC, Brown KE, Saaber S, et al. Dynamic assembly of silent chromatin during thymocyte maturation. Nat Genet. 2004;36:502–506. doi: 10.1038/ng1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cobb BS, Morales-Alcelay S, Kleiger G, et al. Targeting of Ikaros to pericentromeric heterochromatin by direct DNA binding. Genes and Development. 2000;14:2146–2160. doi: 10.1101/gad.816400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trinh LA, Ferrini R, Cobb BS, et al. Down-regulation of TdT transcription in CD4+CD8+ thymocytes by Ikaros proteins in direct competition with an Ets activator. Genes and Development. 2001;15:1817–1832. doi: 10.1101/gad.905601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Favre B, Turowski P, Hemmings BA. Differential inhibition and posttranslational modification of protein phosphatase 1 and 2A in MCF7 cells treated with calyculin-A, okadaic acid, and tautomycin. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:13856–13863. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.21.13856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seldin DC, Leder P. Casein kinase II alpha transgene-induced murine lymphoma: relation to theileriosis in cattle. Science. 1995;267:894–897. doi: 10.1126/science.7846532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown KE, Guest SS, Smale ST, et al. Association of transcriptionally silent genes with Ikaros complexes at centromeric heterochromatin. Cell. 1997;91:845–854. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80472-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dovat S, Song C, Payne KJ, et al. Ikaros, CK2 kinase, and the road to leukemia. Mol Cell Biochem. 2011;356:201–207. doi: 10.1007/s11010-011-0964-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Song C, Li Z, Erbe AK, et al. Regulation of Ikaros function by casein kinase 2 and protein phosphatase 1. World J Biol Chem. 2011;2:126–131. doi: 10.4331/wjbc.v2.i6.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Z, Song C, Ouyang H, et al. Cell cycle-specific function of Ikaros in human leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;59:69–76. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thai TH, Kearney JF. Isoforms of terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase: developmental aspects and function. Adv Immunol. 2005;86:113–136. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(04)86003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ernst P, Hahm K, Smale ST. Both LyF-1 and an Ets protein interact with a critical promoter element in the murine terminal transferase gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:2982–2992. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.5.2982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ernst P, Hahm K, Trinh L, et al. A potential role for Elf-1 in terminal transferase gene regulation. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:6121–6131. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.11.6121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ernst P, Hahm K, Cobb BS, et al. Mechanisms of transcriptional regulation in lymphocyte progenitors: insight from an analysis of the terminal transferase promoter. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1999;64:87–97. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1999.64.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siddiqui-Jain A, Drygin D, Streiner N, et al. CX-4945, an orally bioavailable selective inhibitor of protein kinase CK2, inhibits prosurvival and angiogenic signaling and exhibits antitumor efficacy. Cancer Res. 2010;70:10288–10298. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zanin S, Borgo C, Girardi C, et al. Effects of the CK2 Inhibitors CX-4945 and CX-5011 on Drug-Resistant Cells. PLoS One. 2012;7:e49193. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Siddiqui-Jain A, Bliesath J, Macalino D, et al. CK2 inhibitor CX-4945 suppresses DNA repair response triggered by DNA-targeted anticancer drugs and augments efficacy: mechanistic rationale for drug combination therapy. Mol Cancer Ther. 2012;11:994–1005. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]