Abstract

AIM: To study the association between irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) variants (constipation, diarrhea, or both) and personality traits in non-psychiatric patients.

METHODS: IBS was diagnosed using the Rome II diagnostic criteria after exclusion of organic bowel pathology. The entry of each patient was confirmed following a psychiatric interview. Personality traits and the score of each factor were evaluated using the NEO Five Factor Inventory.

RESULTS: One hundred and fifty patients were studied. The mean age (± SD) was 33.4 (± 11.0) year (62% female). Subjects scored higher in neuroticism (26.25 ± 7.80 vs 22.92 ± 9.54, P < 0.0005), openness (26.25 ± 5.22 vs 27.94 ± 4.87, P < 0.0005) and conscientiousness (32.90 ± 7.80 vs 31.62 ± 5.64, P < 0.01) compared to our general population derived from universities of Iran. Our studied population consisted of 71 patients with Diarrhea dominant-IBS, 33 with Constipation dominant-IBS and 46 with Altering type-IBS. Scores of conscientiousness and neuroticism were significantly higher in C-IBS compared to D-IBS and A-IBS (35.79 ± 5.65 vs 31.95 ± 6.80, P = 0.035 and 31.97 ± 9.87, P = 0.043, respectively). Conscientiousness was the highest dimension of personality in each of the variants. Patients with C-IBS had almost similar personality profiles, composed of higher scores for neuroticism and conscientiousness, with low levels of agreeableness, openness and extraversion that were close to those of the general population.

CONCLUSION: Differences were observed between IBS patients and the general population, as well as between IBS subtypes, in terms of personality factors. Patients with constipation-predominant IBS showed similar personality profiles. Patients with each subtype of IBS may benefit from psychological interventions, which can be focused considering the characteristics of each subtype.

Keywords: Irritable bowel syndrome, Personality, Conscientiousness, Neuroticism, Openness, Constipation-predominant

INTRODUCTION

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common functional gastrointestinal disorder with a wide variety of presentations that include abdominal pain, bloating, disturbed defecation (constipation and/or diarrhea) or alternating bowel habits, and the absence of any detectable organic pathological process[1]. Symptom-based criteria along with limited medical evaluation are used for diagnosis. Treatment is challenging because of the heterogeneity of the presenting symptoms, together with the unclear pathophysiology of the disorder. To date, treatment strategies are focused on specific symptoms, potential underlying disorders in stress responsiveness, and predisposing psychological features.

Regardless of the unclear etiology of the syndrome, it is commonly accepted as being a disorder closely influenced by affective factors. IBS seems to be influenced by psychosocial stressors and psychiatric comorbidity. The incidence of mood and anxiety disorders has been well studied in IBS patients. The high rates of psychiatric co-morbidity in IBS patients indicate that the affective symptoms may be specific and integral to the syndrome, rather than be a specific syndrome related to a chronic intestinal disease[2]. This has resulted in recommendations on how to best detect and integrate treatments to achieve better outcomes for these patients[3], and has led to significant improvements. Patients and physicians might benefit from detailed identification and psychotherapeutic intervention in patients with comorbid psychiatric disorders (as opposed to psychodynamic personality dysfunction).

However, the underlying personality structure might be misinterpreted at the present time because of the poor quality and dubious results of early research done in the area of personality factors as they relate to IBS[4]. The five-factor model of personality defines personality traits in terms of five basic dimensions: extraversion, which incorporates talkativeness, assertiveness and activity level; agreeableness, which includes kindness, trust and warmth; conscientiousness, which includes organization, thoroughness and reliability; neuroticism versus emotional stability, which includes nervousness, moodiness and temperamentality; and openness to experience, which incorporates imagination, curiosity and creativity. This model has been widely accepted because the structure of traits in it is consistent among highly diverse cultures with various languages, and between men and women, and older and younger adults[5].

Patients are often subclassified by their predominant bowel habits, that is, constipation-predominant, diarrhea-predominant, or alternating diarrhea and constipation. Patients with IBS share basic pathophysiological features, regardless of bowel habits; however, differences in perception, autonomic function, and symptom characteristics between constipation-predominant and diarrhea-predominant patients have been described[6-8]. Psychological treatment has been reported to be more effective for diarrhea- than constipation-predominant patients[9]. The association between psychological features and specific symptoms of IBS has been minimally explored. We hypothesized that personality traits are also associated with the dominant symptom of IBS. We sought to assess the distribution of personality traits in IBS patients in our cohort as a first step, and then define any relationship with dominant symptoms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Continuous patients attending our university outpatient clinics with a diagnosis of IBS were included. Diagnosis was established after a stool examination, clinical evaluation and endoscopy (in some cases) by a gastroenterologist using the ROME II criteria for IBS. All patients were clinically investigated to identify the presence of “alarm factors”. Patients were excluded if an organic cause of the condition were possible, or if there were a history of serious somatic disease. All patients gave informed written consent. Demographic information, severity and course of illness, abdominal pain severity over previous weeks, bowel habits and gastrointestinal symptoms were obtained. Patients described whether their symptoms arose with stress and if/how they disrupted their daily activities. Patients were divided into three groups: constipation-predominant (C-IBS), diarrhea-predominant (D-IBS) and altering diarrhea or constipation (A-IBS), according to their self-explanation of recent symptoms.

Patients were referred to the first author, who was blinded to characteristics of IBS, for psychiatric and psychosomatic assessments. A history or current symptoms of any DSM-IV psychiatric diagnosis[11] on axis I or seizure disorders led to exclusion from the study.

Personality dimensions in non- psychiatric IBS patients were evaluated by the NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI), a 60-item questionnaire which usually requires 10-15 min to complete. This questionnaire is rated on a five-point scale to yield scores in five major domains of personality and requires a sixth-grade reading level. Scores of five personality factors measured by NEO have previously been described in a survey of an Iranian population of all universities[10].

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the SPSS Statistical package ver.13 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Means ± SD were used to describe continuous variables and proportions for categorical data. Conditions were met for using two-tailed Student’s t test and Chi-square test, which were applied when appropriate. Within- and between-group comparisons were performed using ANOVA. The Bonferroni inequality test was used to affirm that significance was not reached by chance alone. Overall significance was set at 0.05.

RESULTS

One hundred and fifty patients age, mean ± SD was 33.4 ± 11.0 year (62% female), with IBS by ROME II criteria were enrolled in the study. Bowel problems that were provoked by distress in > 80% of patients interrupted daily activities in up to 70%.

NEO-FFI showed a significantly higher level of neuroticism and conscientiousness and a lower level of openness in the non-psychiatric IBS patients. Table 1 shows mean scores for five personality factors in our patients compared to the Iranian general population (by NEO FFI)[12]. Women with IBS had significantly higher levels of neuroticism, conscientiousness and extraversion compared to men (P = 0.032, 0.003 and 0.037 in that order) (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Mean (SD) scores of five personality factors measured by FFI in patients with irritable bowel syndrome compared to the Iranian general population

| IBS patients | General population | P | |

| Openness | 26.25 (5.22) | 27.94 (4.87) | < 0.0005 |

| Conscientiousness | 32.90 (7.80) | 31.62 (5.64) | < 0.0005 |

| Extraversion | 27.06 (6.09) | 26.89 (6.15) | 0.733 |

| Agreeableness | 28.97 (6.74) | 32.90 (7.00) | 0.344 |

| Neuroticism | 26.25 (7.80) | 22.92 (9.54) | < 0.0005 |

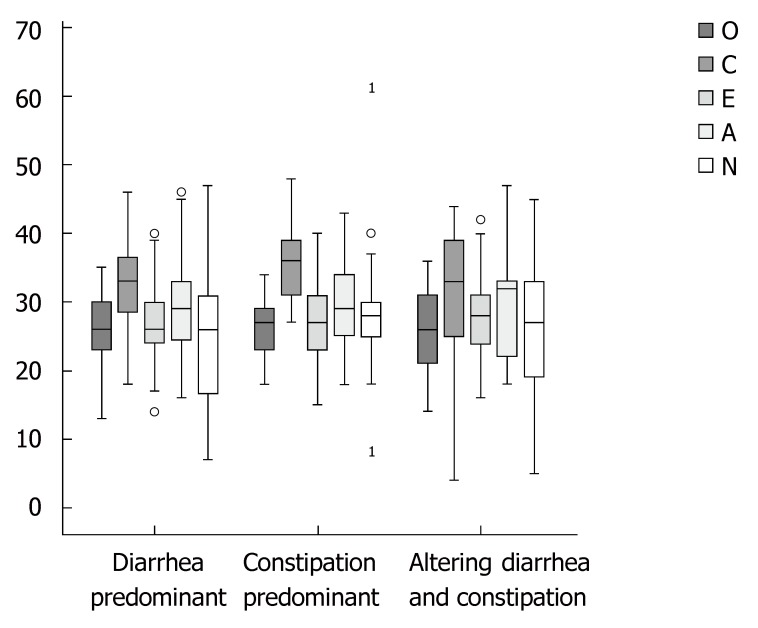

Figure 1.

Scores of personality factors in irritable bowel syndrome patients, defined by dominant symptom. Box plots show distribution of the scores, defining means, minimum, maximum, range, interquartile range and cases out of 95% confidence intervals( as1). O: Openness to Experience; C: Conscientiousness; E: Extraversion; A: Agreeableness; N: Neuroticism.

Our study population consisted of 71 patients with D-IBS, 33 with C-IBS and 46 with A-IBS. Patient occupation, educational level and marriage status had similar patterns among the groups. Symptoms reported by patients with C-IBS and A-IBS were more related to stressors (P = 0.004).

The score for conscientiousness was significantly higher in C-IBS (35.79 ± 5.65) than D-IBS (31.95 ± 6.80) and A-IBS (31.97 ± 9.87) (P = 0.035 and 0.043). Neuroticism had a higher score in C-IBS compared to the other groups (P = 0.044). Conscientiousness was the highest dimension of personality in each of the variants: 42% of C-IBS, 55% of D-IBS and 47% of A-IBS patients.

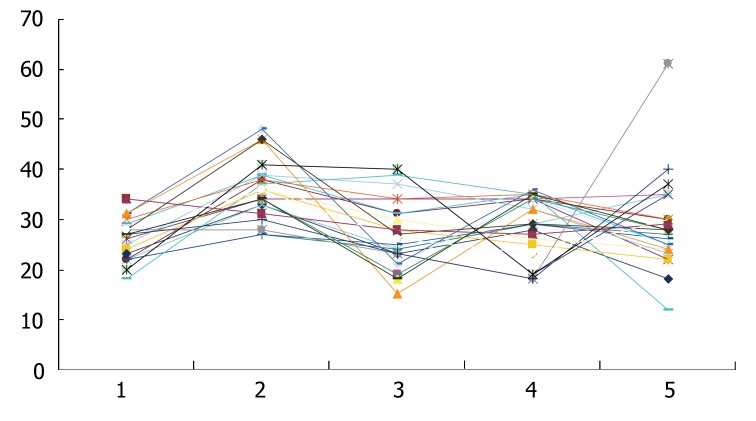

Personality profiles were somewhat capricious in patients with A-IBS and D-IBS. Whereas, patients with C-IBS had mostly similar personality profiles (Figure 2), which showed higher scores for neuroticism and conscientiousness, a low level of agreeableness, along with openness and extraversion close to those of the general population.

Figure 2.

Personality profiles in patients with C-IBS. 1: Openness to Experience; 2: Conscientiousness; 3: Extraversion; 4: Agreeableness; 5: Neuroticism.

DISCUSSION

The present study was designed to investigate personality characteristics of non-psychiatric IBS patients considering their IBS subtype. Emotional states and personality traits may affect the physiology of the gut[13], and play a role in how symptoms are experienced and interpreted, and can thus influence treatment[14,15]. This can be an important issue when considering a management strategy to achieve a better outcome for an IBS patient. The prevalence of IBS has been reported to be 18.4% in the general Iranian population[16].

The five-factor model provides a dimensional account of the structure of normal personality traits, dividing personality into five broad dimensions. There has been little research examining the biological correlates of the dimensions and very little in known about the personality structure in IBS patients. Neuroticism and aggression are reported to be higher in patients with functional gastrointestinal disease without psychiatric comorbidity, and personality traits are believed to influence pain reporting[17]. A low level of neuroticism and little concealed aggressiveness is reported to predict treatment outcome with antidepressants in non-psychiatric patients, which are most prominent in women. These personality dimensions are better predictors of outcome than serotonergic sensitivity[18].

Differences between male and female patients with IBS have been reported; the significant differences found here in the traits of neuroticism, extraversion and conscientiousness were consistent with other studies that suggest women consistently score higher than men on self-reported trait anxiety[19,20]. The data for non-psychiatric individuals drawn from a pool prepared for standardization of the Iranian version of NEO PI-R are among the limitations of the present study. For a more appropriate comparison, the control individuals in future studies might be beneficially selected from the member of patients' family.

Studies on personality dimensions according to subtypes of IBS are limited. Similar personality dimensions (by the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory) have been reported in subgroups of IBS patients with predominant constipation and for those with predominant diarrhea[21].

In the current study, C-IBS patients scored higher on neuroticism and conscientiousness. Neuroticism is a personality trait characterized by overstated reactivity to physiological changes. According to Costa and McCrae[5], people with elevated scores on the neuroticism dimension are emotionally unstable with overwhelmingly negative emotions. Neuroticism is related to emotional intelligence, which involves emotional regulation, motivation, and interpersonal skills. Hans Eysneck theorized that neuroticism is a function of activity in the limbic system, and research suggests that people who score high on neuroticism have a more reactive sympathetic nervous system, and are more sensitive to environmental stimulation[22]. Centrally targeted medications, such as anxiolytics and low-dose tricyclic antidepressants, which involve inhibitory effects on the sensitivity of emotional motor system[23] are widely used for C-IBS patients[24] as they can balance the neuroticism dimension of such patients.

Individuals with high self-consciousness are not at ease with others, are sensitive to ridicule, and prone to feelings of inferiority. This is compatible with a lack of success in completing the “anal stage” of Freud’s theory of psychosexual development, which is supposed to result in an obsession with perfection and control. Such patients may benefit from selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors which increase the extracellular level of the neurotransmitter serotonin.

Personality disorders can be conceptualized as extreme variants of the normal personality dimensions[25]. Excluding such disorders, we sought the personality make up that can introduce vulnerable profiles for IBS in a cross-sectional manner. Research has focused on incorporating various forms of psychotherapy in the hope of alleviating symptoms. Psychological interventions have been aimed at individuals and at groups and include insight-oriented psychotherapy, hypnotherapy, behavior therapy and group psychotherapy. Such interventions try to address various unconscious conflicts in the subject and thereby help them re-establish a sense of emotional stability[26], modify maladaptive behavior and seek new solutions to problems[27], incorporate multi-component cognitive-behavioral therapy treatment programs[28], and have reported significant improvement in symptoms. It is felt that the profession of counseling psychology, which looks to develop wellness, strength and resources within individuals, has the potential to make a unique contribution to the prevention and alleviation of IBS[29]. Presently, the effectiveness of psychological treatments in IBS is being reviewed[30] in the light of conflicting evidence that supports the use of psychological treatment, an inadequate methodology for randomized controlled trials in this area, and the limited evidence of how to improve the global health of IBS patients with drug therapy[31]. The present study presents added evidence of the differences between subgroups of IBS. As such, this may help to focus management plans in each subgroup to obtain better outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Mrs. Maryam Akbari for her helpful assistance.

COMMENTS

Background

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common functional gastrointestinal disorder that is commonly accepted as a disorder closely related to psychological factors. Patients might benefit from detailed identification and psychotherapeutic interventions.

Research frontiers

Mood and anxiety disorders are well studied in IBS patients but information about any underlying personality structure is lacking. Additionally, differences in subtypes of IBS (according to dominant symptom) have been described in perception, autonomic function, and symptom characteristics, which are recommended for evaluation in IBS patients according to their presenting symptoms. This report elucidates personality characteristics of IBS patients according to their dominant symptom using a well-designed personality questionnaire.

Innovations and breakthroughs

IBS patients scored higher on neuroticism, openness and conscientiousness compared to the general Iranian population. Conscientiousness was the highest dimension of personality in each of the variants. The scores for conscientiousness and neuroticism were significantly higher in C-IBS compared to D-IBS and A-IBS. An analogous personality profile was noted in patients with C-IBS composed of the higher scores of neuroticism and conscientiousness, a low level of agreeableness, and with openness and extraversion similar to those of the general population.

Applications

Overstated personality dimensions of IBS patients (especially the constipation-dominant subtype) can be balanced by the use of well-known medications, like anxiolytics, low-dose tricyclic antidepressants and selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors. Given the added evidence of the differences between subtypes of IBS and vulnerable personality profiles, future studies on drug or psychotherapy may achieve more reliable outcomes.

Terminology

IBS is a gastrointestinal disorder that has a wide variety of presentations that include abdominal pain, bloating, disturbed defecation (constipation and/or diarrhea or alternating bowel habits) and the absence of any detectable organic pathological process. NEO-FFI is a questionnaire with a five-point scale to yield scores in five major domains of personality: openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness and neuroticism

Peer review

The results and conclusions of the paper are reliable. The presentation is adequate and easy to read. There are no ethics problems. This is a good manuscript with an interesting approach to the subject.

Footnotes

S- Editor Zhu LH L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Liu Y

References

- 1.Camilleri M, Choi MG. Review article: irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11:3–15. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1997.84256000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walker EA, Katon WJ, Jemelka RP, Roy-Bryne PP. Comorbidity of gastrointestinal complaints, depression, and anxiety in the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) Study. Am J Med. 1992;92:26S–30S. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(92)90133-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drossman DA, Corazziari E, Talley NJ, Thompson WG, Whitehead WE. Rome II: a multinational consensus document on functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gut. 1999;45 Suppl II:II1–II81. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.2008.ii1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olden KW. Irritable bowel syndrome: What is the role of the psyche? Dig Liver Dis. 2006;38:200–201. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Costa PT, McCrae RR. Stability and change in personality assessment: the revised NEO Personality Inventory in the year 2000. J Pers Assess. 1997;68:86–94. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6801_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elsenbruch S, Orr WC. Diarrhea- and constipation-predominant IBS patients differ in postprandial autonomic and cortisol responses. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:460–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aggarwal A, Cutts TF, Abell TL, Cardoso S, Familoni B, Bremer J, Karas J. Predominant symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome correlate with specific autonomic nervous system abnormalities. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:945–950. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90753-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heitkemper M, Jarrett M, Cain KC, Burr R, Levy RL, Feld A, Hertig V. Autonomic nervous system function in women with irritable bowel syndrome. Dig Dis Sci. 2001;46:1276–1284. doi: 10.1023/a:1010671514618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tillisch K, Labus JS, Naliboff BD, Bolus R, Shetzline M, Mayer EA, Chang L. Characterization of the alternating bowel habit subtype in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:896–904. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garousi MT. Application of the NEO PIR test and analytic evaluation of its characteristics and factorial structure among Iranian university students. Human Sci Alzahra Uni. 2001;11:30–38. [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Psychiatric Association. American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. pp. 320–327. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guthrie E, Creed F, Dawson D, Tomenson B. A controlled trial of psychological treatment for the irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:450–457. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90215-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wood JD, Alpers DH, Andrews PL. Fundamentals of neurogastroenterology. Gut. 1999;45 Suppl 2:II6–II16. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.2008.ii6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bennett EJ, Piesse C, Palmer K, Badcock CA, Tennant CC, Kellow JE. Functional gastrointestinal disorders: psychological, social, and somatic features. Gut. 1998;42:414–420. doi: 10.1136/gut.42.3.414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drossman DA, Creed FH, Olden KW, Svedlund J, Toner BB, Whitehead WE. Psychosocial aspects of the functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gut. 1999;45 Suppl 2:II25–II30. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.2008.ii25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghannadi K, Emami R, Bashashati M, Tarrahi MJ, Attarian S. Irritable bowel syndrome: an epidemiological study from the west of Iran. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2005;24:225–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tanum L, Malt UF. Personality and physical symptoms in nonpsychiatric patients with functional gastrointestinal disorder. J Psychosom Res. 2001;50:139–146. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(00)00219-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tanum L, Malt UF. Personality traits predict treatment outcome with an antidepressant in patients with functional gastrointestinal disorder. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:935–941. doi: 10.1080/003655200750022986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fock KM, Chew CN, Tay LK, Peh LH, Chan S, Pang EP. Psychiatric illness, personality traits and the irritable bowel syndrome. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2001;30:611–614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tran Y, Craig A, Boord P, Connell K, Cooper N, Gordon E. Personality traits and its association with resting regional brain activity. Int J Psychophysiol. 2006;60:215–224. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2005.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Talley NJ, Phillips SF, Bruce B, Twomey CK, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ. Relation among personality and symptoms in nonulcer dyspepsia and the irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1990;99:327–333. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)91012-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sato T. The Eysenck Personality Questionnaire Brief Version: factor structure and reliability. J Psychol. 2005;139:545–552. doi: 10.3200/JRLP.139.6.545-552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Drossman DA, Camilleri M, Mayer EA, Whitehead WE. AGA technical review on irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:2108–2131. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.37095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jailwala J, Imperiale TF, Kroenke K. Pharmacologic treatment of the irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review of randomized, controlled trials. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:136–147. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-2-200007180-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saulsman LM, Page AC. The five-factor model and personality disorder empirical literature: A meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2004;23:1055–1085. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2002.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Creed F, Guthrie E. Psychological treatments of the irritable bowel syndrome: a review. Gut. 1989;30:1601–1609. doi: 10.1136/gut.30.11.1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Creed F, Guthrie E, Ratcliffe J, Fernandes L, Rigby C, Tomenson B, Read N, Thompson DG. Does psychological treatment help only those patients with severe irritable bowel syndrome who also have a concurrent psychiatric disorder? Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005;39:807–815. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2005.01686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Svedlund J, Sjödin I, Dotevall G, Gillberg R. Upper gastrointestinal and mental symptoms in the irritable bowel syndrome. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1985;20:595–601. doi: 10.3109/00365528509089702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blanchard EB, Schwarz SP, Radnitz CR. Psychological assessment and treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Behav Modif. 1987;11:348–372. doi: 10.1177/01454455870113006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Wit N, Zijdenbosch I, van der Heijden G, Quartero O, Rubin G. Psychological treatments for the management of irritable bowel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;2:CD006442. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006442.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quartero AO, Meineche-Schmidt V, Muris J, Rubin G, de Wit N. Bulking agents, antispasmodic and antidepressant medication for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005:CD003460. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003460.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]