Abstract

Objective

To examine health care costs among patients with eating disorders using the Blue Cross Blue Shield of North Dakota (BCBSND) claims database system.

Method

Four groups of individuals enrolled between 1999 and 2005 were identified: 1) a group diagnosed with eating disorders at the beginning of the study period, in 2000 or 2001; 2) a group diagnosed with eating disorders later in the study period, in 2004 or 2005; 3) a comparison group with depression; and 4) a non-eating disordered comparison group.

Results

Health care costs were high for patients diagnosed with an eating disorder during the period when the diagnosis was made but remained elevated in the years following. Such costs were consistently higher than those for the non-eating disordered comparison group, but similar to the depression comparison group.

Conclusion

Health care costs remained elevated after a diagnosis of an eating disorder for an extended period of time.

Introduction

It is widely known that eating disorders (ED) are associated not only with psychiatric symptoms but with physical symptoms and medical complications as well1. It has been reported previously that general health care utilization among this group of patients is high1–5. The topic of health services utilization and costs by patients with eating disorders has been recently reviewed6. This review concluded that there were indications of elevated health services utilization among those with ED, with a cautionary note that the available studies probably provided underestimates of the costs involved since most studies have examined primarily in-patient utilization or have utilized limited data sets. Also, it is of note that only two studies7, 8 have examined EDNOS, which is a particularly important omission, given the fact that this is the most commonly encountered diagnosis in clinical practice9. The study by Striegel-Moore and colleagues is of perhaps of particular relevance to the current analysis8. In that study electronic records were used to capture data on out-patient, in-patient and medication expenses on a cohort of individuals 18–55 years of age who received a diagnosis of an eating disorder in the year 2003. This study found that cases with eating disorders had elevated health service utilization in all service lines compared to matched controls, including the year before and after the diagnosis, and the elevations were found to be similarly elevated across eating disorder diagnostic groupings including anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and EDNOS.

The current study reports an analysis of data obtained from the Blue Cross Blue Shield of North Dakota (BCBSND) claims data obtained between 1999 and 2005. We were interested in examining health care costs both before and after an ED diagnosis was made, and to compare these data to a psychiatric (depressed) comparison group and a non-ED comparison groups.

Method

The study population was identified as members of BCBSND who had a primary or secondary diagnosis of an eating disorder (ED; bulimia nervosa, BN; anorexia nervosa, AN; or eating disorder not otherwise specified, EDNOS) and two comparison groups. Those who were enrolled in Medicare, Federal Employee Programs, were out-of-state, 65 or older as of 2005 and younger than 18 were excluded from the analysis due to incomplete claims history in those categories. Due to the low number of males in the ED groups they were also excluded. Two patients in the ED groups were excluded with diagnoses of malignancies. Those included must have been continuously enrolled at BCBSND a minimum of 52.5 months between 2000 and 2005 to ensure complete claims histories and include the two periods of first ED diagnosis (Groups 1 and 2).

Group 1

ED post-diagnosis group (n = 167). These patients first had a primary or secondary diagnosis of an ED in either 2000 or 2001. In addition a second ED diagnosis must have occurred within 365 days of the first diagnosis. At least two such diagnoses were required to confirm the ED diagnosis. Costs were counted from the first diagnosis. This group allowed us to examine the types of conditions, services and expenditures these patients accrued when and after they were diagnosed with an ED.

Group 2

ED pre-diagnosis group (n = 155). These patients first had a primary or secondary ED diagnosis in either 2004 or 2005 with a second ED diagnosis having occurred within 365 days of the first diagnosis. Costs were counted from the first diagnosis. This group allowed us to examine the types of conditions, services and expenditures these patients accrued before, when and after they were diagnosed with an ED.

Group 3

Non-ED psychiatric comparison group with depression (n = 224). These patients were selected if they did not have a primary or secondary diagnosis of an ED between 1999 and 2005, but did have a first diagnosis of major depressive disorder in 2000 or 2001 along with a subsequent diagnosis within 365 days of the first diagnosis. Costs were counted from the first diagnosis. Patients in this category were matched by age groups, using a proportional (i.e. stratified) random sample using the age distributions of groups 1 and 2.

Group 4

Non-ED comparison group (n = 6,866). These patients did not have a primary or secondary diagnosis of an ED between 1999 and 2005. Members found in Group 3 could be included. Since no additional diagnostic exclusions were applied, these patients represent a randomly selected group without eating disorders. Patients in this category were also matched by age groups, using a proportional (i.e. stratified) random sample using the age distributions of groups 1 and 2.

Results

The results willl first present diagnostic information for the two ED groups and then data on age ranges and mean ages. We will then turn to the cost data comparisons among the 4 groups. The breakdown by diagnosis for the 2 ED groups was as follows: Group 1 (post ED group) AN = 11, BN = 72 and EDNOS = 84; Group 2 (Pre ED group) AN = 6, BN = 50, EDNOS = 99. The numbers are greater than the total number of cases because some patients received more than one ED diagnosis over time. For example some patients with AN crossed over to BN. Data on mean age and age ranges by group are shown in Table 1 As can be seen, the mean age in all four groups was early 30’s with the largest number of patients in the age 30 or less categories.

Table 1.

Age ranges and mean ages.

| Age Range | Group 1 ED Post | Group 2 ED Pre | Group 3 Depressed | Group 4 Non-ED | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| 18 to 23 | 73 | 43.7% | 71 | 45.8% | 100 | 44.6% | 3,073 | 44.8% |

| 24 to 30 | 25 | 15.0% | 13 | 8.4% | 26 | 11.6% | 802 | 11.7% |

| 31 to 40 | 26 | 15.6% | 24 | 15.5% | 35 | 15.6% | 1,066 | 15.5% |

| 41 to 50 | 25 | 15.0% | 2 | 18.7% | 38 | 17.0% | 1,156 | 16.8% |

| 51 to 63 | 18 | 10.8% | 18 | 11.6% | 25 | 11.6% | 769 | 11.2% |

| Total | 167 | 100.0% | 155 | 100.0% | 224 | 100.0% | 6,866 | 100.0% |

| Avg. Age | 31.4 | 32.2 | 32.2 | 31.7 | ||||

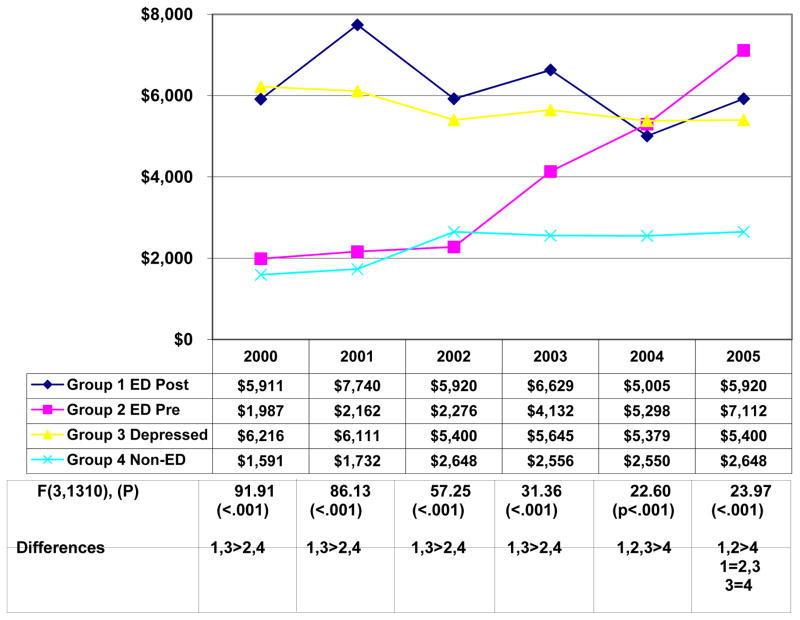

The data points for overall cost by group for each year were examined in an ANOVA, which was significant for each year (p<.001). Pair-wise comparisons between groups were made on the basis of Tukey’s HSD post hoc tests. Average costs overall including professional costs (e.g. office visits, diagnostics), institutional costs (e.g. hospital, facilities) and pharmacy costs are shown in Figure 1. The overall ANOVA was significant for each year. Pair wise comparisons are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Average expenditures per patient by year.

In examining Group 1, the post-ED group, health care costs were elevated relative to groups 2 and 4 and similar to the depressed controls in group 3 in the first two years, but continued elevated relative to the Group 4 comparison group throughout the study until the last year. Group 2 patients who received a diagnosis of an ED in 2004 or 2005, experienced a significant elevation in costs in the first two years of first diagnosis and this elevation continued beyond these 2 years. Costs for patients with major depressive disorder (Group 3) were elevated throughout the study period. The most common types of professional costs for both Groups 1 and 2 was “chem/psych office”, meaning professional costs for mental health/chemical dependency outpatient visits.

Average costs by diagnosis for Groups 1 and 2 for the years 2000–2005 are shown in Table 2. Of interest overall costs were highest for those with BN and EDNOS, and lowest for those with AN, in both groups. However, the sample size of AN patients was quite small in both groups. Pharmacy costs were highest for those with EDNOS and lowest for those with AN. The types of drugs most utilized by those in Groups 1 and 2 were “Central Nervous System Agents”. The highest cost psychotropic drugs were Effexor® and Zoloft®.

Table 2.

Costs by Diagnosis

| DX | Group 1 ED Post | Group 2 ED Pre | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Avg. Expenditures | Avg. Expenditures | ||

| AN | Institutional a | $1,193 | $276 |

| Professional b | $1,720 | $1,193 | |

| Pharmacy c | $492 | $603 | |

| Total | $3,405 | $2,072 | |

| BN | Institutional a | $2,962 | $2,836 |

| Professional b | $2,660 | $1,803 | |

| Pharmacy c | $1,017 | $615 | |

| Total | $6,639 | $5,254 | |

| EDNOS | Institutional a | $2,376 | $1,461 |

| Professional b | $3,035 | $1,984 | |

| Pharmacy c | $1,476 | $1,205 | |

| Total | $6,887 | $4,650 |

Institutional = Hospital, Clinic

Professional = Health Care Provider

Pharmacy = Prescription Medication

Discussion

The results of this study can be best compared to the study by Striegel-Moore and colleagues8 which examined health care utilization in a series of adults age 18–55 diagnosed with an eating disorder during 2003 with the time of focus being 2002–2004 in order to capture the period leading up to and following the eating disorder diagnosis. Similar to the current study elevation in health services were seen during and after the diagnosis of eating disorder compared to a matched comparison of health plan members. That study found evidence of increasing health utilization before the diagnosis as well, a finding we apparently did not replicate, although this was a non-significant suggestion of an increase in the year prior to diagnosis. However, the Striegel-Moore et al. study8 used utilization data, while the present study used cost data, and therefore the two studies are not directly comparable, and similarities and differences may be explainable by that difference. These authors found that patients with eating disorders were being treated not only in primary care but also received more ancillary services such as specialty care and emergency/urgent care. They did not find significant variability among diagnostic groupings but stressed the importance of the EDNOS population in terms of both the number of individuals and their health care utilization patterns. These findings were similar to the ones to emerge from the current analysis.

Group 1 (post-diagnosis) patients had elevated health care cost that persisted until nearly the end of the observation period, suggesting continued problems that persisted until the last year of the study period.

Group 2 (pre-diagnosis) patients also saw a rise and peak in costs during the years of diagnosis of an ED. Although there was a suggestion of increasing costs prior to the ED diagnosis, this was not significant. This suggests the interesting possibility that they were being seen for complaints that may have been related to an eating disorder but at that point remained undiagnosed. Again, the findings in Groups 1 and 2 are similar to those in the study by Striegel-Moore and colleagues8. However, in that study, clear significant increases were seen both before and after the diagnosis.

As was found by Striegel-Moore and colleagues8, the EDNOS patients accrued significantly higher costs than other groups of ED. This finding, coupled with the fact that EDNOS represents the most common diagnosis in eating disorder clinics9 and in some community samples10, speaks to the need to better characterize and perhaps classify these patients.

To ensure that this sample wasn’t contaminated by those receiving bariatric surgery, patients who had undergone such procedures were examined separately, and it was found that seven of the patients in Group 1 (4.2%) and ten of the patients in Group 2 (6.5%) had undergone a bariatric surgery procedure during the timeframe of the analysis. These patients had an insignificant impact on expenditures (between 0.75% and 3.13% decrease in all expenditures if excluded).

The fact that professional, institutional, and pharmacy costs were lowest for patients diagnosed as having AN is in some ways surprising, although the small sample size may be an issue. One possible explanation is that the patients diagnosed as having the disorder may not continue to seek treatment and therefore the utilization pattern may be low despite their having a very serious illness. Also of note is the fact that costs were high overall for all years in Group 1 and a pattern of increasing healthcare costs could be seen in Group 2 over the years after the diagnosis of an ED was made compared to Group 4. The costs for those with major depressive disorder (Group 3) were more stable year to year, despite the fact that these individuals were first diagnosed in 2000 or 2001. This suggests that depression is a chronic condition and requires ongoing management.

There are several limitations that need to be considered, in addition to the small number of AN patients. First, diagnoses were clinical rather than research based. Second, continuous enrollment for 52.5 months or more was required; therefore severe cases that resulted in loss of benefits or death would not have been ascertained. Third, patients may have utilized services that were not paid for by BCBSND and therefore we would not have had access to those data. Another possible limitation of this study is our inability to disentangle health care that was received because of the comorbidity seen in patients with eating disorders as was also noted in the Striegel-Moore et al. study8. Such a differentiation would be impossible given this kind of data base analysis.

Acknowledgments

Support by RO1 MH058820 from the National Institute of Health

References

- 1.Pritts SD, Susman J. Diagnosis of Eating Disorder in Primary Care. American Family Physician. 2003;67:297–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walsh JME, Wheat ME, Freund K. Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of Eating Disorders. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:577–590. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.02439.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sansone RA, Wiederman MW, Sansone LA. Healthcare Utilization among Women with Eating Disordered Behavior. Am J Man Care. 1997;3:1721–1723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ogg EC, Millar HR, Pusztai EE, Thom AS. General Practice Consultation Patterns Preceding Diagnosis of Eating Disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 1997;22:89–93. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199707)22:1<89::aid-eat12>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson JG, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. Health problems, impairment and illnesses associated with bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder among primary care and obstetric gynecology patients. Psychol Medicine. 2001;31:1455–1466. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701004640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simon J, Schmidt U, Pilling S. The health service use and cost of eating disorders. Psychol Medicine. 2005;35:L1543–1551. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705004708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Striegel-Moore RH, Leslie D, Petrill SA, Garvin V, Rosenheck RA. One-year use and cost of inpatient and outpatient services among female and male patients with an eating disorder: evidence from a national database of health insurance claims. Int J Eat Disord. 2000;27:381–389. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(200005)27:4<381::aid-eat2>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Striegel-Moore RH, DeBar L, Wilson GT, Dickekrson J, Rosselli F, Perrin N, Lynch F, Kraemer HC. Health services use in eating disorders. Psychol Medicine. 2007:1–10. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707001833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fairburn CG, Bohn K. Eating disorders NOS (EDNOS): an example of the troublesome “not otherwise specified” (NOS) category in DSM-IV. Beh Res Therapy. 2005:691–701. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Machado PP, Machado BC, Goncalves S, Hoek HW. The prevalence of eating disorders not otherwise specified. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40:212–217. doi: 10.1002/eat.20358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]