Significance

The discovery of V domain-containing Ig suppressor of T-cell activation (VISTA) as a novel immune-checkpoint regulator comes at an exciting time, as the field of cancer immunotherapy has made significant progress owing to the clinical success of targeting immune-checkpoint proteins such as cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 and programmed death 1 and ligand. Recent studies also show the promise of monoclonal antibody-mediated VISTA targeting for enhancing antitumor immunity in murine tumor models. The current study demonstrates the spectrum of immune alterations upon genetic disruption of VISTA in mice in the context of self-tolerance as well as immune response against neoantigen. These results enhance the understanding of the immune-regulatory role of VISTA and form the foundation for designing future clinical applications that target VISTA in treating human diseases.

Keywords: immune suppression, inflammation, autoimmunity, peripheral tolerance

Abstract

V domain-containing Ig suppressor of T-cell activation (VISTA) is a negative checkpoint regulator that suppresses T cell-mediated immune responses. Previous studies using a VISTA-neutralizing monoclonal antibody show that VISTA blockade enhances T-cell activation. The current study describes a comprehensive characterization of mice in which the gene for VISTA has been deleted. Despite the apparent normal hematopoietic development in young mice, VISTA genetic deficiency leads to a gradual accumulation of spontaneously activated T cells, accompanied by the production of a spectrum of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. Enhanced T-cell responsiveness was also observed upon immunization with neoantigen. Despite the presence of multiorgan chronic inflammation, aged VISTA-deficient mice did not develop systemic or organ-specific autoimmune disease. Interbreeding of the VISTA-deficient mice with 2D2 T-cell receptor transgenic mice, which are predisposed to the development of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, drastically enhanced disease incidence and intensity. Disease development is correlated with the increase in the activation of encephalitogenic T cells in the periphery and enhanced infiltration into the CNS. Taken together, our data suggest that VISTA is a negative checkpoint regulator whose loss of function lowers the threshold for T-cell activation, allowing for an enhanced proinflammatory phenotype and an increase in the frequency and intensity of autoimmunity under susceptible conditions.

Immune responses against foreign pathogens or self-antigens are regulated by multiple layers of positive and negative molecules and pathways, as exemplified by molecules of the B7 family. B7-1/2 and B7-H2 provide critical costimulatory signals for T-cell activation, whereas multiple “negative checkpoint” regulators, involving cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4), programmed death 1 (PD-1) and ligand (PD-L1), B7-H3, and B7-H4, down-regulate T-cell responses (1, 2). Disruption of these pathways leads to loss of peripheral tolerance and development of autoimmunity (3). For example, CTLA-4 genetic deficiency leads to a fatal lymphoproliferative disorder (4, 5), whereas PD-1–deficient mice develop autoimmune dilated cardiomyopathy or lupus-like autoimmune phenotypes depending upon the genetic background (6, 7). In addition, PD-L1 or PD-1 blockade either by antibody or genetic deletion, on autoimmune-susceptible backgrounds, promotes autoimmune diabetes (8–10) and exacerbates autoimmune kidney disease (11), autoimmune hepatitis (12), and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) (13, 14).

V domain-containing Ig suppressor of T-cell activation (VISTA) is a member of the B7 family that bears homology to PD-L1 and is exclusively expressed within the hematopoietic compartment (15). VISTA is highly expressed on CD11bhigh myeloid cells, and is also expressed at lower densities on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. A soluble VISTA–Ig fusion protein or VISTA expressed on antigen-presenting cells (APCs) acts as a ligand that suppresses T-cell proliferation and cytokine production via an unidentified receptor. VISTA-specific monoclonal antibody reversed VISTA-mediated T-cell suppression in vitro and in vivo (15, 16). The human homolog shares 90% homology with murine VISTA, and similar expression patterns and suppressive function were reported for human VISTA (17).

It is hypothesized that VISTA is an immune-checkpoint regulator that negatively regulates immune responses. To gain a comprehensive perspective on the immune-regulatory role of VISTA, we examined the impact of the genetic deletion of VISTA on the maintenance of self-tolerance as well as T-cell responses against neoantigens. The results show that VISTA-deficient mice demonstrate an age-related proinflammatory signature, spontaneous T-cell activation, as well as enhanced cell-mediated immune responses to neoantigen, and greatly promoted autoimmunity when interbred onto an autoimmune-susceptible background.

Results

Spontaneous T-Cell Activation and Chronic Multiorgan Inflammation in VISTA Knockout Mice.

VISTA knockout (ko) mice were obtained from the Mutant Mouse Regional Resource Centers (www.mmrrc.org; stock no. 031656-UCD) (18). The original VISTAko mice on a mixed genetic background were fully backcrossed onto the C57BL/6 background. VISTAko mice were born at normal size, maturation, and fertility, with normal thymic development and with populations of lymphocytes [T, B, natural killer (NK), and NK T cells] in the bone marrow, spleen, and lymph nodes (LNs) indistinguishable in number and frequency from their WT counterparts.

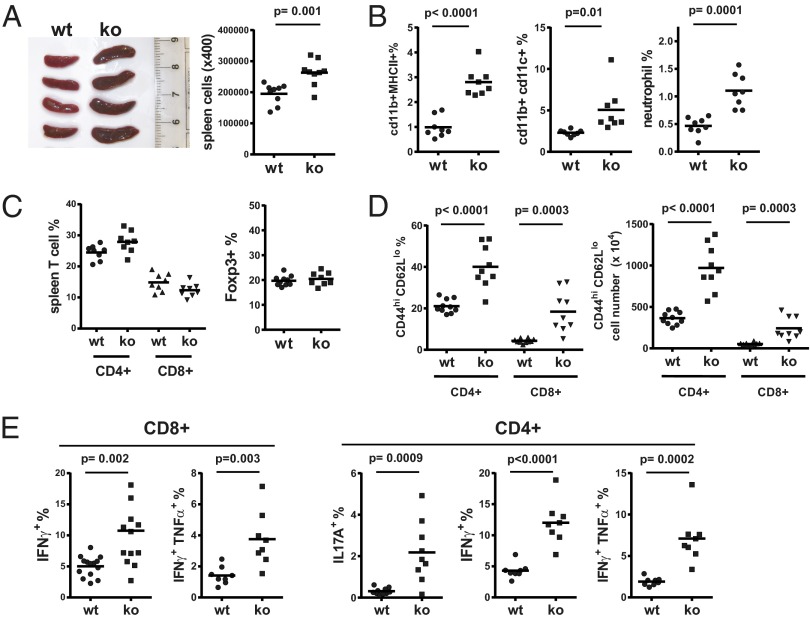

Changes in a wide variety of immunological parameters were compared in VISTAko and WT mice (7–10 mo of age). VISTAko mice showed moderate increases in spleen size, indicating heightened homeostasis of certain hematopoietic cell populations (Fig. 1A). Surface phenotypes of splenic cells confirmed that there were increased percentages of CD11b+ MHCII+ myeloid populations as well as CD11b+ CD11c+ myeloid dendritic cells (DCs) and CD11b+ Ly6G+ neutrophils (Fig. 1B). Such an increase of myeloid APCs and inflammatory cells such as neutrophils might indicate certain levels of ongoing inflammation in the naïve VISTAko mice.

Fig. 1.

Altered hematopoietic phenotypes in the spleens of VISTAko mice. Spleens from 8- to 9-mo-old age- and sex-matched WT and VISTAko mice were examined for the presence of hematopoietic lineages. The size of spleens and number of splenic cells from WT and VISTAko mice are shown (A). The percentages of myeloid lineage cells (such as myeloid DCs and neutrophils), T cells, and FOXP3+ CD4+ regulatory T cells are shown (B and C). Surface activation phenotype (CD44hi CD62Llo) and cytokine production of splenic T cells are shown (D and E). Shown are representative results of at least three independent experiments.

In contrast to WT mice, VISTAko mice showed significantly higher frequencies of activated peripheral T cells in both spleen and peripheral blood. This is manifested as increased populations of CD44hi CD62Llo T cells (Fig. 1D and Fig. S1A) as well as cytokine production, such as IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-17A from VISTAko T cells upon polyclonal stimulation (Fig. 1E and Fig. S1 B and C). The total T-cell percentage in the spleens of WT and VISTAko mice is similar (Fig. 1C).

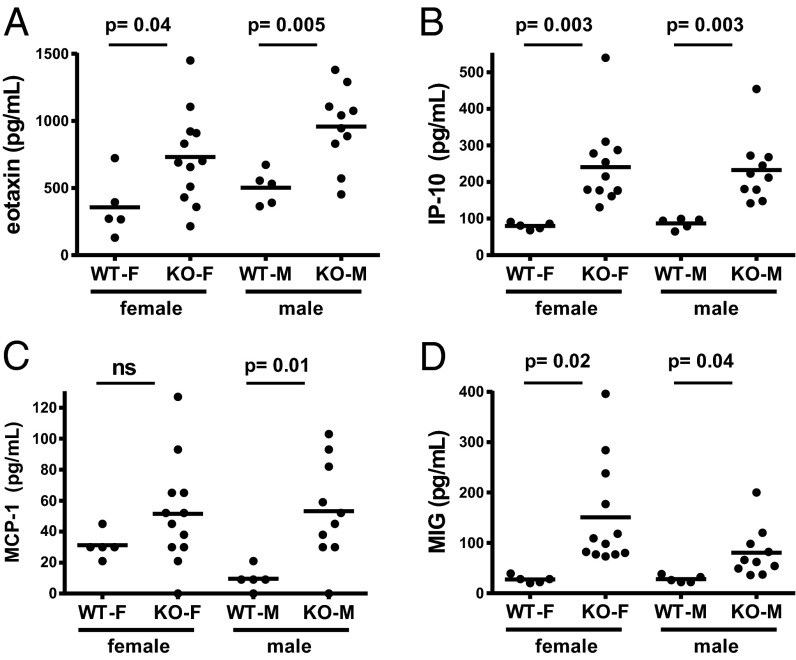

Several chemokines that are known to be induced by IFN-γ directly or indirectly, such as eotaxin, IP-10, MIG, and MCP-1, showed increased levels in the serum (Fig. 2). These data indicate a Th1-polarizing phenotype in the VISTAko mice compared with age-matched C57BL/6 controls. There are no significant differences in the serum levels of other inflammatory cytokines such as G-CSF, GM-CSF, IFN-γ, IL-1α/β, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-9, IL-13, IL-15, IL-17A, LIX, TNF-α, and RANTES.

Fig. 2.

Accumulation of inflammatory chemokines in aged VISTAko mice. Plasma from heparinized blood was collected from 8- to 9-mo-old KO mice. Increased levels of inflammatory chemokines, including eotaxin (A), IP-10 (B), MCP-1 (C), and MIG (D), were detected by the Luminex multiplex immunoassay (Millipore) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Shown are representative results of two independent experiments. ns, not significant.

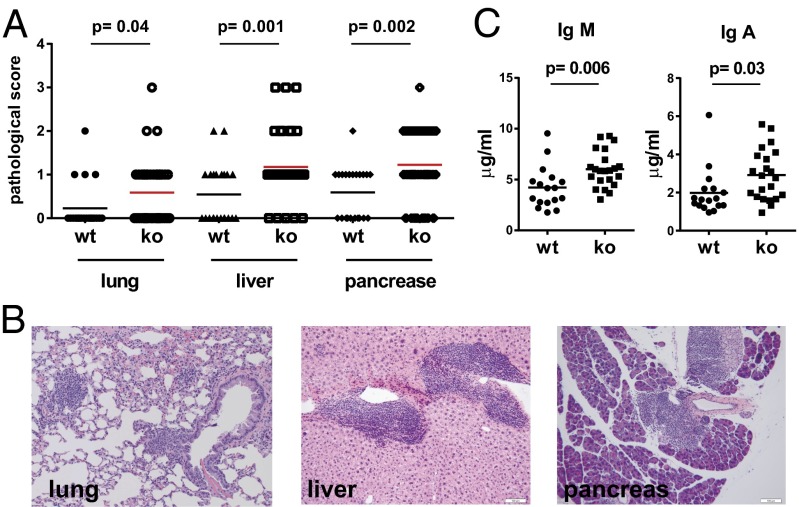

To further determine whether aged VISTAko mice developed any systemic or organ-specific autoimmune disease, a comprehensive multiorgan pathological analysis was performed. H&E sections from heart, lung, liver, kidney, pancreas, salivary glands, small and large intestines, and brain were quantified for immune cell infiltration and potential structural damage due to immune cell-mediated destruction. Three organs (lung, liver, and pancreas) were found to contain significant numbers of immune cell infiltrates (Fig. 3 A and B). However, despite the presence of chronic inflammation in multiple tissues, aged VISTAko mice (∼1-y-old) did not develop overt organ-specific autoimmune disease. There is no statistically significant increase of antinuclear autoantibodies in the serum, nor immune-complex deposition in the glomeruli. Islets from inflamed VISTAko pancreas were mostly intact, even when surrounded by infiltrating immune cells. Levels of IgM and IgA, but not IgG subtypes (i.e., IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, and IgG3), were moderately elevated in the serum of 1-y-old VISTAko mice (Fig. 3C). Together, these data indicate that VISTAko does not result in any overt autoimmunity in the absence of other predisposing factors.

Fig. 3.

Pathological analysis of aged VISTAko mice. Necropsy was performed on 1-y-old WT (n = 22) and VISTAko mice (n = 39). Organs were fixed, paraffin-embedded, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The inflammatory state of the tissues was evaluated based on a semiquantitative method that describes the level of the immunological cell infiltration (A). Representative H&E sections show the infiltration of immune cells within lung, liver, and pancreas (B). (Scale bars: 50 μm.) Levels of serum IgA and IgM were quantified by the ELISA method and were shown to be elevated in VISTAko mice (C).

VISTA Deficiency Enhances the Development of Th1/17-Mediated Autoimmune Disease.

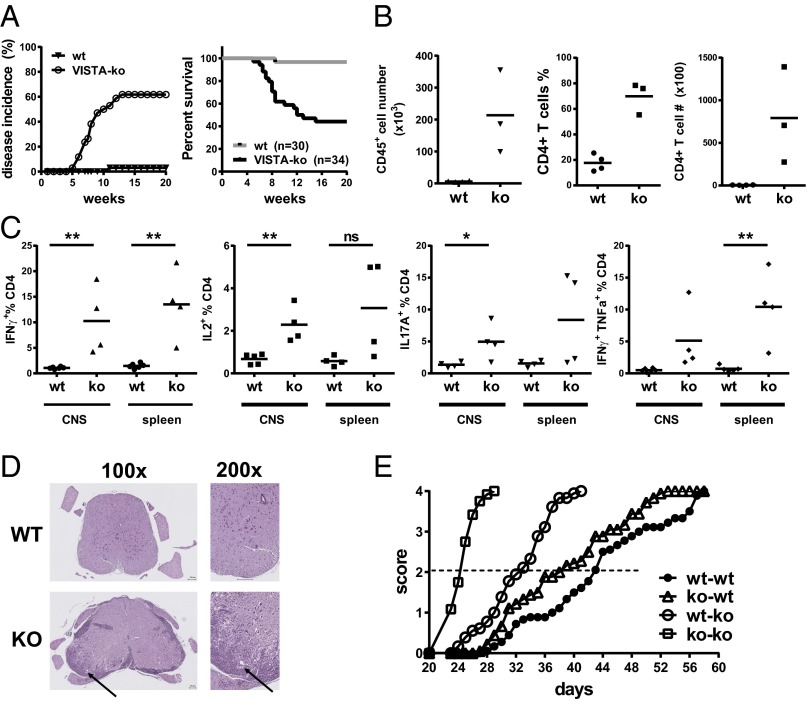

The activated T-cell phenotypes observed in aging VISTAko mice pointed to the fact that VISTAko may lower the threshold of T-cell receptor (TCR) activation to self-antigens. As such, it was hypothesized that VISTAko would greatly increase the predisposition to the development of autoimmunity when interbred onto a background where there was a high frequency of self-reactive T cells. VISTAko mice were interbred with the 2D2 TCR transgenic strain that expresses a TCR recognizing the self-antigen myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG35–55) (19). Previous studies reported that 4% of 2D2 TCR mice develop spontaneous EAE between 3 and 5 mo of age. A similar incidence and onset time of spontaneous EAE (∼3%; 1 out of 30 mice) was observed in our colony of WT 2D2 mice (Fig. 4A). In sharp contrast, VISTA deficiency accelerated disease onset, such that ∼61% (21 out of 34 mice) of 2D2 TCR x VISTAko mice rapidly succumbed to complete hind limb paralysis within 2–3 mo of age (Fig. 4A). As summarized in Table 1, the age of disease onset in the knockout 2D2 mice was between 5 and 13 wk (SEM 0.48). Among diseased knockout 2D2 mice (a total of 21 mice), 19 mice reached the maximum disease score (3.5) approved by the institutional animal care and use committee (IACUC). Two diseased VISTAko mice developed atypical EAE, manifested as unilateral limb paralysis, rather than typical bilateral ascending paralysis. Two diseased mice developed hind limb paresis around 8 wk of age, but failed to progress and partially recovered from the disease by 20 wk of age. Analysis of CNS and spleen further confirmed heightened frequencies of activated IFN-γ+– and IL-17A+–producing CD4+ T cells in the CNS of VISTAko 2D2 TCR mice compared with WT controls (Fig. 4 B and C). Histological analysis confirmed significant leukocyte infiltration into the CNS (Fig. 4D) and demyelination (Fig. S2) in the VISTAko 2D2 mice at the peak of the disease. On the other hand, VISTA deficiency moderately enhanced the incidences of spontaneous optic neuritis in the 2D2 transgenic mice (Table 1). The overall disease incidences were low, most likely due to the younger age group (within 20 wk of age) in our analysis than previously described (19).

Fig. 4.

Genetic deficiency of VISTA exacerbates autoimmune disease development. EAE disease incidence and mortality in 2D2 TCR transgenic mice bred onto the VISTAko background were drastically increased compared with WT 2D2 mice; nwt = 30, nko = 34 (A). Analysis of CNS and spleen revealed accumulation of pathogenic CD4+ T cells expressing IFN-γ and IL-17A (B and C); **P < 0.025, *P < 0.05. Representative H&E sections of a spinal cord sample from paralyzed 2D2 x VISTAko mice are shown (D). (Scale bar: 100 μm.) Black arrows indicate a representative area with dense infiltration of lymphocytes. An adoptive-transfer model of EAE was established to examine the role of VISTA on T cells and non-T cells for disease development (E). WT and VISTAko naïve 2D2 CD4+ T cells (80,000) were adoptively transferred into naïve WT and VISTAko immune-deficient RAGko hosts. The development of CNS disease was monitored over time and recorded as described in Materials and Methods. Shown are representative results of at least three independent experiments.

Table 1.

Comparison of disease onset, severity, incidence, mortality, and occurrence of atypical EAE symptoms and optic neuritis in the absence of EAE in WT and VISTAko 2D2 transgenic mice

| Genotype | Disease-onset age range, wk | Disease severity, lowest to highest score range | Disease incidence | Mortality | Atypical EAE symptom | Optic neuritis without EAE |

| WT 2D2 | 11 (1 mouse) | 3.5 (1 mouse) | 1/30 | 1/30 | 0/30 | 1/30 |

| Ko 2D2 | 5–13 (SEM 0.48) | 2–3.5 (SEM 0.098) | 21/34 | 19/34 | 2/34 | 2/34 |

VISTA is expressed on both T cells and myeloid cells. To gain a perspective on the relative contribution of VISTA in each of these lineages to controlling the development of autoimmunity, the functional role of VISTA in these lineages was evaluated in a passive-transfer model of EAE, where naïve MOG-specific CD4+ 2D2 T cells were adoptively transferred into the immune-deficient RAGko hosts (Fig. 4E). This model offered the opportunity to restrict VISTA deficiency on either the transferred T cells or the host, neither, or both. Upon transfer of 2D2 T cells into a RAGko host, T cells were activated and expanded, resulting in hind limb paralysis over a period of 1–2 mo. Disease progression was observed without the need for immunization with adjuvant or exogenous administration of peptide. Transfer of VISTAko 2D2 cells into VISTAko RAGko hosts recapitulated the occurrence of aggressive disease observed in the intact 2D2 VISTAko mice, so that the medium disease score was reached with much faster kinetics in the VISTAko RAGko hosts (23–32 d) compared with VISTAwt RAGko hosts (38–40 d), regardless of whether WT or VISTAko 2D2 cells were transferred (Fig. 4E). Such an acceleration of disease development established an important negative immune-regulatory role of VISTA expressed on myeloid cells. Loss of VISTA on T cells also impacted on disease progression, as transfer of VISTAko 2D2 T cells into VISTAko RAGko hosts led to rapid disease progression, with a medium disease score reached around 23 d, versus 32 d when WT 2D2 T cells were transferred. Together, these data indicate that VISTA deficiency on both T and myeloid cells contributes to the control of autoimmunity.

Enhanced T-Cell Responses in VISTA-Deficient Mice in Response to Acute Immune Challenge.

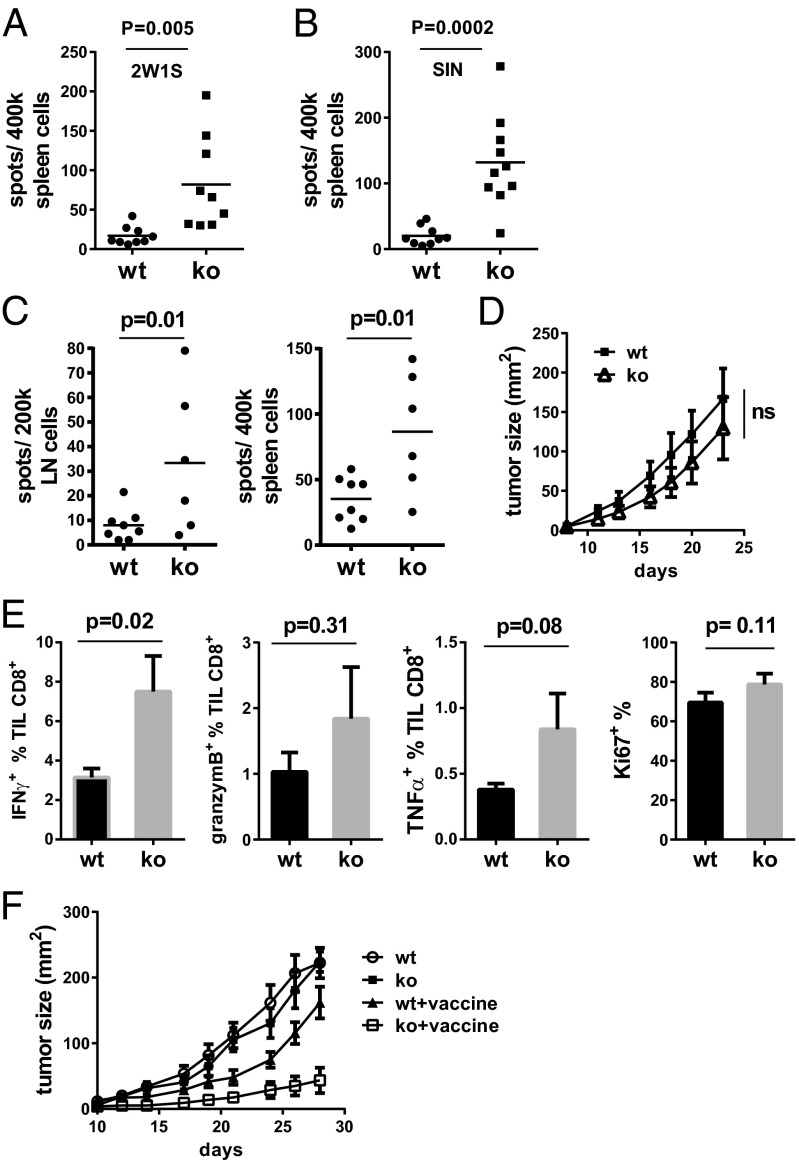

Spontaneous T-cell activation in aged VISTAko mice and the enhanced autoimmunity observed in the absence of VISTA expression in autoimmune-prone mice indicate that VISTA contributes to the control of T-cell responsiveness toward either self-antigens or environmental antigens. As such, the question of whether VISTA deficiency could enhance T-cell activation in response to acute immune challenge with neoantigens was evaluated. The cell-mediated immune responses of WT and VISTAko mice to a soluble model antigen peptide mixed with Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonist polyI:C as adjuvant were compared (Fig. 5 A and B). 2W1S is an MHC class II-restricted peptide, and SIN is an MHC class I-restricted peptide. On day +7 postimmunization, spleen cells were examined for the production of IFN-γ when restimulated with peptide. Significantly increased numbers of IFN-γ–producing cells were observed in cells derived from VISTAko mice in response to 2W1S (Fig. 5A) and SIN peptide immunization (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

VISTA deficiency enhances T-cell responses against acute immune challenges. WT and VISTAko mice (6- to 7-wk-old) were immunized with the soluble peptides (100 μg) 2W1S (A) and SIN (B) mixed with TLR3 agonist polyI:C (100 μg) as adjuvant. Splenocytes were harvested on day +7 postimmunization and restimulated with the relevant peptides. IFN-γ–producing cells were enumerated by the ELISPOT assay. To analyze tumor-specific T-cell responses, B16OVA tumor cells (200,000) were inoculated into the flank of WT and VISTAko mice on day 0. Tumor-draining LN and spleen cells were harvested on day +12 and restimulated with radiated tumor cells. IFN-γ–producing cells from tumor-draining LNs and spleen were enumerated by the ELISPOT assay (C). Tumor size was measured by a caliper and is shown (D). The production of IFN-γ, TNF-α, and granzyme B, as well as the proliferation of CD8+ TILs, was analyzed by flow cytometry and is shown (E). (F) B16BL6 cells (25,000) were inoculated into the flank of WT and VISTAko mice on day 0. Tumor-bearing mice were treated with a peptide vaccine on days +5 and +12, as described in Materials and Methods. Tumor size was measured by a caliper. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean (SEM). Shown are representative results from two or three independent experiments.

In addition to soluble antigens, the immune responses against tumor-associated antigens were measured in WT and VISTAko mice (Fig. 5 C–E). Mice were administered B16 melanoma cells expressing neoantigen chicken OVA. On day +7 posttumor administration, cell preparations from tumor-draining LNs and spleen were restimulated with tumor antigen and the number of IFN-γ–producing cells was quantified by the enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay. Significantly enhanced tumor-specific IFN-γ responses were observed in T cells from spleen and tumor-draining LNs, as well as within the tumor tissue (tumor-infiltrating T cells; TILs) of VISTAko tumor-bearing mice compared with WT mice (Fig. 5C). However, tumor growth was not significantly reduced (Fig. 5D). Consistently, there was no significant increase of granzyme B and TNF-α production or of the proliferation (Ki67 expression) of tumor-infiltrating T cells in VISTAko mice (Fig. 5E). In an attempt to further boost the magnitude of tumor-specific T-cell responses, B16 melanoma tumor-bearing mice were treated with a peptide vaccine using TLR agonists as adjuvant (16). Consistent with our hypothesis, tumor growth was significantly inhibited in the VISTAko mice upon vaccine treatment compared with WT mice (Fig. 5F). Collectively, these data suggest that VISTA deficiency enhances T-cell responses against neoantigens in the absence and presence of induced inflammation such as via TLR agonists.

Discussion

The spontaneous activation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in aged VISTAko mice, as well as the chronic inflammation in multiple tissues, indicates the loss of peripheral tolerance upon disruption of the VISTA pathway. In contrast to the lethal phenotype of CTLA-4ko mice, VISTA deficiency did not lead to severe systemic autoimmune pathology, suggesting that other immune-regulatory pathways mitigated the development of inflammation and autoimmunity induced by VISTA deficiency. In that regard, multiple other immune checkpoints, namely CTLA-4, PD-1, B7-H3, and B7-H4, might compensate for the genetic loss of VISTA and might play a role in suppressing the ongoing inflammation in VISTAko mice.

VISTA deficiency overcame additional immune-regulatory mechanisms, and significantly enhanced the development and progression of EAE on a disease-prone transgenic background (Fig. 4). This result is similar to studies showing that PD-L1 deficiency exacerbates autoimmunity only under disease-prone conditions (8, 11). Our study therefore affirms the notion that VISTA is a nonredundant immune-checkpoint regulator that maintains peripheral tolerance and controls autoimmunity.

Similar to PD-L1, VISTA is expressed on both APCs and T cells. Although our previous study demonstrated that VISTA expressed on APCs inhibited T-cell activation by engaging an unidentified receptor on T cells (15), the physiological role of VISTA expressed on T cells remains unclear. We established an adoptive-transfer model of EAE to address the relative contribution of VISTA expressed on T cells and non-T cells (Fig. 4E). Our data show a dominant role of VISTA expressed on non-T cells, because VISTA expression in the host effectively suppressed disease progression, regardless of whether WT or knockout 2D2 encephalitogenic T cells were transferred. On the other hand, VISTA expression on 2D2 T cells played a clear role in regulating disease progression, particularly in VISTAko hosts. These data indicate that VISTA expression on both APCs and T cells contributes to its immune-regulatory role. In that regard, a recent study showed that VISTA might be an inhibitory receptor on T cells (20). Alternatively, VISTA on T cells might exert its immunosuppressive function via engaging a receptor expressed on APCs. Future studies will focus on distinguishing these potential mechanisms.

Enhanced T-cell response, manifested as IFN-γ production, was observed toward neoantigen immunization in the VISTAko mice (Fig. 5 A and B). Although a similar increase of IFN-γ production was observed in the B16 melanoma-bearing VISTAko mice, KO TILs failed to produce significantly higher amounts of granzyme B and TNF-α, and tumor growth was not significantly impaired either (Fig. 5 C–E). We speculate that the relatively weak production of TNF-α and granzyme B contributed to the lack of tumor control. In addition, it has been shown that IFN-γ might limit antitumor T-cell responses via up-regulating noncognate MHC class I on tumor cells (21). This result is, however, in contrast to our previous study demonstrating the efficacy of a VISTA-specific monoclonal antibody in the B16 melanoma model (16). We hypothesize that the engagement of Fc receptors by a VISTA-specific antibody might further enhance tumor-specific immune responses. Similar Fc receptor-dependent mechanisms have been shown to be critical for the therapeutic efficacies of antibodies targeting CTLA-4 and GITR (22, 23). On the other hand, a recent study described the impaired growth of murine brain glioma cells in VISTAko mice, as well as the role of VISTA-deficient CD4+ T cells in mediating tumor suppression (20). We speculate that the unique immunogenicity of the glioma tumor model might have contributed to the stronger tumor-specific T-cell responses than those seen in the B16 melanoma model. In conclusion, our study using VISTA genetic-deficient mice has confirmed the immune-suppressive function of VISTA and warrants further studies to tease apart the cellular and molecular mechanisms of VISTA-mediated immune regulation.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

C57BL/6 mice were purchased from the National Cancer Institute. VISTA-deficient mice on a fully backcrossed C57BL/6 background were obtained from the Mutant Mouse Regional Resource Centers (18). 2D2 TCR transgenic mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. All animals were maintained in a pathogen-free facility at The Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth. All animal protocols were IACUC-approved at Dartmouth College.

Antibodies, Cell Lines, and Reagents.

Antibodies αCD3 (2C11), αCD28 (PV-1), αCD4 (GK1.5), αCD8 (53-6.7), αCD11b (M1/70), αF4/80 (BM8), αCD11c (N418), αNK1.1 (PK136), αGr1 (RB6-8C5), αIFN-γ (XMG1.2), αIL-17A (eBio17B7), and αTNF-α (MP6-XT22) were purchased from eBioscience. TLR agonists polyI:C, R848, and CpG (ODN1826) were from InvivoGen, and recombinant murine IFN-γ and human IL-2 were from PeproTech. All peptides were synthesized by Atlantic Peptides. Melanoma cell line B16BL6 was as described (24). B16F10 expressing chicken ovalbumin (B16OVA) was generated as described previously (25).

Mice Necropsy and Semiquantitative Pathological Analysis.

Age- and sex-matched WT and VISTAko mice were killed by CO2 asphyxiation. Organs were harvested and fixed in 10% (vol/vol) buffered formalin. Hematoxylin and eosin staining was performed on tissue sections. Tissue inflammatory status was scored in a blind manner by a pathologist using the following semiquantitative scoring criteria: 0, normal; 1, mild/small foci of dense lymphocytic infiltrate; 2, moderate/multiple foci of dense/large activated lymphocytic infiltrate with/without a germinal center; 3, marked reactive/activated or atypical lymphocytic infiltrate.

T-Cell Cytokine Production Analysis.

Cells from spleens, lymph nodes, or blood were stimulated overnight in complete Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium (IMDM) supplemented with polyclonal stimuli αCD3 antibody 2C11 (5 μg/mL), αCD28 antibody PV1 (500 ng/mL), 10% FBS, 2 mM l-glutamine, 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, 1% penicillin/streptavidin, 1 mM nonessential amino acids, 1× monensin (eBioscience), and 1× brefeldin A (BioLegend). Cells were then stained for intracellular cytokines as indicated and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Peptide Immunization and ELISPOT Assay.

Peptides 2W1S (EAWGALANWAVDSA) (26) and SIN (SIINFEKL) were synthesized by Atlantic Peptides. Peptides (100 μg) were dissolved in PBS, mixed with TLR3 agonist polyI:C (100 μg), and injected intraperitoneally. Splenocytes were harvested on day +7 postimmunization and restimulated with the relevant peptides in complete IMDM as described above. IFN-γ–producing cells were enumerated by the ELISPOT assay.

Monitoring the Spontaneous Disease Phenotypes in 2D2 Transgenic Mice.

Spontaneous development of EAE and optic neuritis phenotypes was monitored as previously described (19). Clinical assessment of EAE was performed according to the following criteria: 0, no disease; 1, limp tails; 2, hind limb paresis or partial paralysis; 3, complete hind limb paralysis; 3.5, front limb paresis; 4, front and hind limb paralysis and moribund state. Disease onset was recorded when mice showed limp tails. The clinical assessment of optic neuritis is based on the following criteria: eyelid redness and swelling associated with tearing, and signs of atrophy of the eye.

Tumor Models, Tumor Vaccine, and Treatment.

B16OVA and B16BL6 tumor cells were inoculated into the right flank of WT or VISTAko mice. Tumor vaccine consisted of CD40 agonistic antibody FGK (27) (100 µg), polyI:C (50 µg), CpG (ODN1826; 20 µg), R848 (50 µg), tumor antigen peptide TRP1 (106–130; 100 µg), and a mutated TRP2 peptide, DeltaV-TRP2 (180–188; 100 µg) (Atlantic Peptides) (28–30). The vaccine mixture was applied with split dose s.c. on the indicated days. Tumor size was measured by a caliper every 2–3 d.

To examine the tumor-specific T-cell responses in tumor-draining lymph nodes and spleen, cells were harvested and restimulated with irradiated tumor cells overnight in complete IMDM as described above. IFN-γ–producing cells were enumerated by the ELISPOT assay. To examine the responses of TILs, B16OVA tumor tissues were harvested and digested with liberase (0.4 mg/mL) and DNase I (0.2 mg/mL) for 20 min at 37 °C. Tumor tissues were mashed with a syringe through 70-μm cell strainers. TILs were enriched through a gradient of 40% and 80% Percoll and restimulated overnight in complete IMDM with 10% FBS, 2 mM l-glutamine, 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, 1% penicillin/streptavidin, 1 mM nonessential amino acids, human IL-2 (5 U/mL; PeproTech), 1× monensin (eBioscience), 1× brefeldin A (BioLegend), OVA peptide OVA323–339 (10 µg/mL), and OVA257–264 (2.5 µg/mL) (AnaSpec). The expression of IFN-γ, TNF-α, and granzyme B was examined by flow cytometry.

Flow Cytometry and Analysis.

Flow cytometry analysis was performed either on a FACScan using CellQuest software (BD Biosciences) or on a MACSQuant 7 color analyzer (Miltenyi Biotec). Data analysis was performed using FlowJo software (Tree Star).

Graphs and Statistical Analysis.

All graphs and statistical analysis were generated using Prism 4 (GraphPad Software). A Student t test (two-tailed) was used for the data analyses. ***P < 0.005, **P < 0.025, *P < 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the DartLab flow cytometry core facility for technical support. This work is supported by National Institutes of Health Grant CA164225 (to L.W.), a Melanoma Research Foundation Career Development Award (to L.W.), a Hitchcock Foundation Research Grant (to L.W.), AI048667 (to R.J.N.), the Wellcome Trust (R.J.N.), and the Medical Research Council Centre for Transplantation and Biomedical Research Center at King’s College London (R.J.N.).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: L.W. and R.J.N. are involved with ImmuNext, Inc. and receive financial support for the development of anti-VISTA for immunotherapy.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. C.G.D. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1407447111/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Greenwald RJ, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH. The B7 family revisited. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:515–548. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yi KH, Chen L. Fine tuning the immune response through B7-H3 and B7-H4. Immunol Rev. 2009;229(1):145–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00768.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fife BT, Bluestone JA. Control of peripheral T-cell tolerance and autoimmunity via the CTLA-4 and PD-1 pathways. Immunol Rev. 2008;224(1):166–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waterhouse P, et al. Lymphoproliferative disorders with early lethality in mice deficient in CTLA-4. Science. 1995;270(5238):985–988. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5238.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tivol EA, et al. Loss of CTLA-4 leads to massive lymphoproliferation and fatal multiorgan tissue destruction, revealing a critical negative regulatory role of CTLA-4. Immunity. 1995;3(5):541–547. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90125-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nishimura H, Nose M, Hiai H, Minato N, Honjo T. Development of lupus-like autoimmune diseases by disruption of the PD-1 gene encoding an ITIM motif-carrying immunoreceptor. Immunity. 1999;11(2):141–151. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80089-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nishimura H, et al. Autoimmune dilated cardiomyopathy in PD-1 receptor-deficient mice. Science. 2001;291(5502):319–322. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5502.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keir ME, et al. Tissue expression of PD-L1 mediates peripheral T cell tolerance. J Exp Med. 2006;203(4):883–895. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin-Orozco N, Wang YH, Yagita H, Dong C. Cutting Edge: Programmed death (PD) ligand-1/PD-1 interaction is required for CD8+ T cell tolerance to tissue antigens. J Immunol. 2006;177(12):8291–8295. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.12.8291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ansari MJ, et al. The programmed death-1 (PD-1) pathway regulates autoimmune diabetes in nonobese diabetic (NOD) mice. J Exp Med. 2003;198(1):63–69. doi: 10.1084/jem.20022125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Menke J, et al. Programmed death 1 ligand (PD-L) 1 and PD-L2 limit autoimmune kidney disease: Distinct roles. J Immunol. 2007;179(11):7466–7477. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.11.7466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dong H, et al. B7-H1 determines accumulation and deletion of intrahepatic CD8(+) T lymphocytes. Immunity. 2004;20(3):327–336. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(04)00050-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salama AD, et al. Critical role of the programmed death-1 (PD-1) pathway in regulation of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Exp Med. 2003;198(1):71–78. doi: 10.1084/jem.20022119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu B, et al. Differential role of programmed death-ligand 1 [corrected] and programmed death-ligand 2 [corrected] in regulating the susceptibility and chronic progression of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2006;176(6):3480–3489. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.6.3480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang L, et al. VISTA, a novel mouse Ig superfamily ligand that negatively regulates T cell responses. J Exp Med. 2011;208(3):577–592. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Le Mercier I, et al. VISTA regulates the development of protective antitumor immunity. Cancer Res. 2014;74(7):1933–1944. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lines JL, et al. VISTA is an immune checkpoint molecule for human T cells. Cancer Res. 2014;74(7):1924–1932. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang T, et al. A mouse knockout library for secreted and transmembrane proteins. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28(7):749–755. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bettelli E, et al. Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein-specific T cell receptor transgenic mice develop spontaneous autoimmune optic neuritis. J Exp Med. 2003;197(9):1073–1081. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flies DB, et al. Coinhibitory receptor PD-1H preferentially suppresses CD4+ T cell-mediated immunity. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(5):1966–1975. doi: 10.1172/JCI74589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cho HI, Lee YR, Celis E. Interferon γ limits the effectiveness of melanoma peptide vaccines. Blood. 2011;117(1):135–144. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-298117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bulliard Y, et al. Activating Fc γ receptors contribute to the antitumor activities of immunoregulatory receptor-targeting antibodies. J Exp Med. 2013;210(9):1685–1693. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simpson TR, et al. Fc-dependent depletion of tumor-infiltrating regulatory T cells co-defines the efficacy of anti-CTLA-4 therapy against melanoma. J Exp Med. 2013;210(9):1695–1710. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Elsas A, Hurwitz AA, Allison JP. Combination immunotherapy of B16 melanoma using anti-cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) and granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF)-producing vaccines induces rejection of subcutaneous and metastatic tumors accompanied by autoimmune depigmentation. J Exp Med. 1999;190(3):355–366. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.3.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang L, et al. Programmed death 1 ligand signaling regulates the generation of adaptive Foxp3+CD4+ regulatory T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(27):9331–9336. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710441105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moon JJ, et al. Naive CD4(+) T cell frequency varies for different epitopes and predicts repertoire diversity and response magnitude. Immunity. 2007;27(2):203–213. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahonen CL, et al. Combined TLR and CD40 triggering induces potent CD8+ T cell expansion with variable dependence on type I IFN. J Exp Med. 2004;199(6):775–784. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McWilliams JA, McGurran SM, Dow SW, Slansky JE, Kedl RM. A modified tyrosinase-related protein 2 epitope generates high-affinity tumor-specific T cells but does not mediate therapeutic efficacy in an intradermal tumor model. J Immunol. 2006;177(1):155–161. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ahonen CL, et al. Enhanced efficacy and reduced toxicity of multifactorial adjuvants compared with unitary adjuvants as cancer vaccines. Blood. 2008;111(6):3116–3125. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-114371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muranski P, et al. Tumor-specific Th17-polarized cells eradicate large established melanoma. Blood. 2008;112(2):362–373. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-11-120998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.