Significance

Our sensory environment is teeming with complex rhythmic structure, but how do environmental rhythms (such as those present in speech or music) affect our perception? In a human electroencephalography study, we investigated how auditory perception is affected when brain rhythms (neural oscillations) synchronize with the complex rhythmic structure in synthetic sounds that possess rhythmic characteristics similar to speech. We found that neural phase in multiple frequency bands synchronized with the complex stimulus rhythm and interacted to determine target-detection performance. Critically, the influence of neural oscillations on target-detection performance was present only for frequency bands synchronized with the rhythmic structure of the stimuli. Our results elucidate how multiple frequency bands shape the effective neural processing of environmental stimuli.

Keywords: auditory perception, psychophysics, neuroscience

Abstract

Our sensory environment is teeming with complex rhythmic structure, to which neural oscillations can become synchronized. Neural synchronization to environmental rhythms (entrainment) is hypothesized to shape human perception, as rhythmic structure acts to temporally organize cortical excitability. In the current human electroencephalography study, we investigated how behavior is influenced by neural oscillatory dynamics when the rhythmic fluctuations in the sensory environment take on a naturalistic degree of complexity. Listeners detected near-threshold gaps in auditory stimuli that were simultaneously modulated in frequency (frequency modulation, 3.1 Hz) and amplitude (amplitude modulation, 5.075 Hz); modulation rates and types were chosen to mimic the complex rhythmic structure of natural speech. Neural oscillations were entrained by both the frequency modulation and amplitude modulation in the stimulation. Critically, listeners’ target-detection accuracy depended on the specific phase–phase relationship between entrained neural oscillations in both the 3.1-Hz and 5.075-Hz frequency bands, with the best performance occurring when the respective troughs in both neural oscillations coincided. Neural-phase effects were specific to the frequency bands entrained by the rhythmic stimulation. Moreover, the degree of behavioral comodulation by neural phase in both frequency bands exceeded the degree of behavioral modulation by either frequency band alone. Our results elucidate how fluctuating excitability, within and across multiple entrained frequency bands, shapes the effective neural processing of environmental stimuli. More generally, the frequency-specific nature of behavioral comodulation effects suggests that environmental rhythms act to reduce the complexity of high-dimensional neural states.

Low-frequency neural oscillations have recently been proposed to play a crucial role in perception (1–4). This is because low-frequency neural oscillations reflect fluctuations in local neuronal excitability, meaning they influence the likelihood of neuronal firing in a periodic fashion (4–6). The result is that the probability that a (near-threshold) stimulus will elicit a neuronal response is not a uniform function of time but, instead, depends on the phase of the neural oscillation into which the stimulation falls. Indeed, the dependence of behavioral performance on neural oscillatory phase has been demonstrated in the visual (7–11) and auditory (12–15) domains.

The role of neural oscillatory phase in perception is suggested to be of particular importance when stimuli possess temporal regularity (1, 11, 16, 17). Precise alignment of neural oscillations with rhythmic stimuli is accomplished via entrainment, which is a process by which two oscillations become synchronized, or phase-locked, through phase and/or period adjustments (18). Through entrainment, perception of rhythmic stimuli is optimized when high-energy portions of a signal are aligned with periods of high excitability, whereas low-energy portions of the signal are aligned with periods of low excitability. Because maintenance of a high-excitability state is metabolically more expensive than fluctuating between states of high and low excitability (6), “rhythmic-mode processing” constitutes a particularly efficient means of allocating neuronal resources to rhythmic stimuli (17). From an empirical perspective, rhythmic structure potentially acts to reduce the complexity of the neural state space such that the most informative (entrained) neural assemblies come to dominate the neural dynamics (19). Thus, the use of rhythmic stimulation allows for a hypothesis-driven investigation of neural phase effects on performance, specifically in the entrained frequency bands.

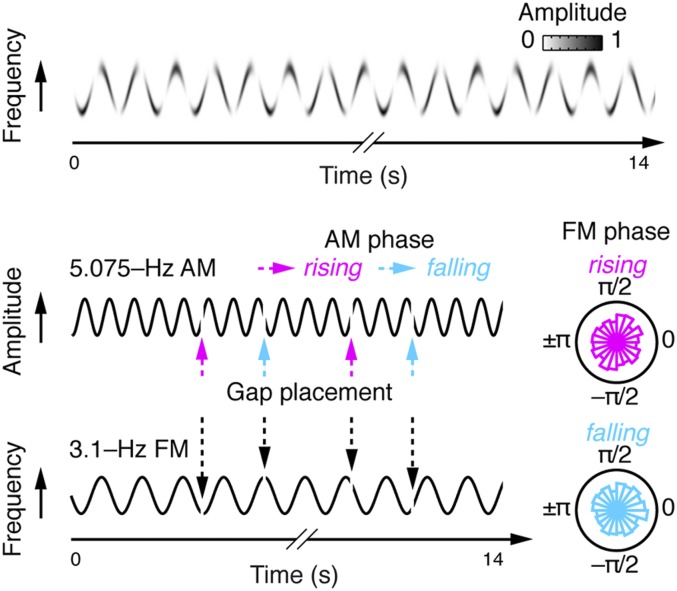

Critically, natural environmental stimuli are rarely perfectly isochronous and possess a complex rhythmic structure that results from variation along a number of dimensions simultaneously. However, the interactive effects of entrained neural phase in more than one frequency band on perception have not been demonstrated in any modality or species. Thus, in the current human electroencephalography (EEG) study, we examined perceptual effects of the phase–phase relations of neural oscillations entrained by slow acoustic pacemakers presented simultaneously at two different frequencies. We modeled our auditory stimuli after the rhythmic structure present in natural speech. In particular, we chose an amplitude modulation (AM) rate in the range of the speech syllable envelope (5.075 Hz, refs. 20–22) and a slower frequency modulation (FM) rate in the range of prosodic fluctuations (3.1 Hz, ref. 23; Fig. 1). Both modulations were applied simultaneously to narrow-band noise stimuli in which to-be-detected near-threshold targets were embedded. By taking into account neural phase in multiple frequency bands simultaneously, we aimed to take a first step toward characterizing the complex interactions among frequency bands that are likely to underlie processing of natural environmental stimuli.

Fig. 1.

Complex rhythmic stimulation and target placement. Schematic time-frequency representation of a complex rhythmic stimulus generated by simultaneously applying AM (5.075 Hz) and FM (3.1 Hz) to a narrow-band noise carrier. Near-threshold gaps fell randomly with respect to 3.1-Hz FM phase and fell equally often into the rising (magenta) or falling (cyan) phase of the 5.075-Hz AM.

Results

Behavioral Modulation by FM and AM Stimulus Phase.

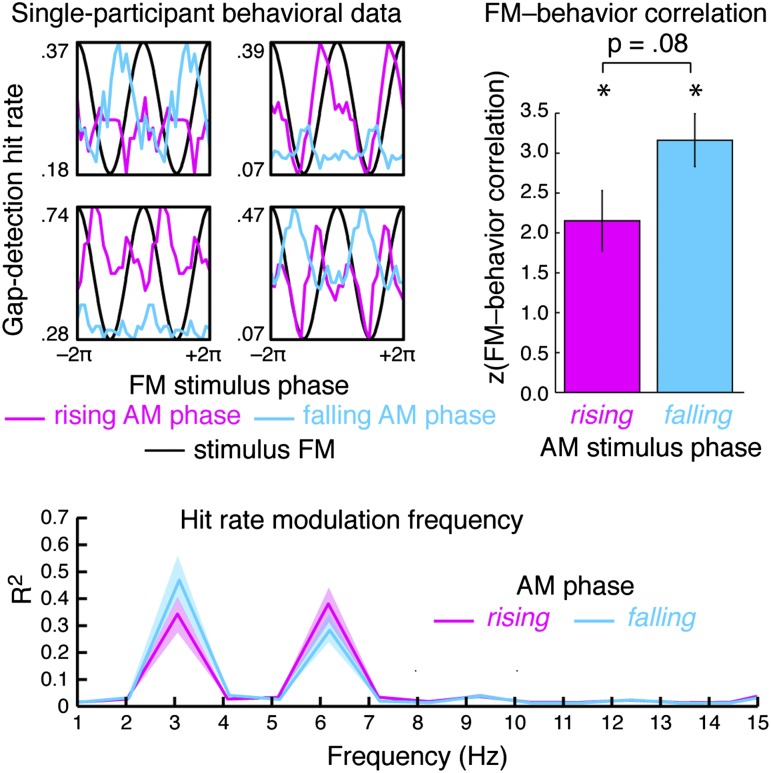

Participants (n = 17) detected near-threshold gaps embedded in rhythmically complex 14-s AM–FM sounds. Gaps fell randomly with respect to the FM phase (Fig. 1) and coincided with either the rising or falling phase of the AM to equalize stimulus energy at the two target locations. Individual participants’ behavioral performance (Fig. 2, Upper Left, and Fig. S1) showed strong and significant modulation by FM stimulus phase, as indexed by significant circular–linear correlations between FM stimulus phase and hit rate [rising AM stimulus phase: t(16) = 5.69, P < 0.001, effect size r = 0.82; falling AM stimulus phase: t(16) = 9.56, P < 0.001, r = 0.92; Fig. 2, Upper Right], that did not differ between rising and falling AM stimulus phases [t(16) = 1.90, P = 0.08, r = 0.43]. Moreover, estimated periodicity in behavioral performance patterns reflected the FM rate (3.1 Hz) and its harmonic (6.2 Hz; Fig. 2, Bottom). We ensured that the behavioral modulation was not driven by detectability differences attributable to stimulus acoustics (12, see SI Data, and Fig. S1).

Fig. 2.

Behavioral data for the gap-detection task. Single-participant hit rates as a function of FM stimulus phase for four exemplary listeners (Upper Left), shown separately for the rising (magenta) and falling (cyan) AM stimulus phases. All listeners showed quasi-periodic modulation of behavior by FM stimulus phase, as indicated by significant circular–linear correlations, for both AM stimulus phases (Upper Right; error bars indicate SEM). Asterisks denote significance at P ≤ 0.005. The periodicity present in the behavioral modulation was specific to the FM rate (3.1 Hz) and its harmonic (6.2 Hz; Lower).

Neural Oscillations Were Entrained by Simultaneous FM and AM.

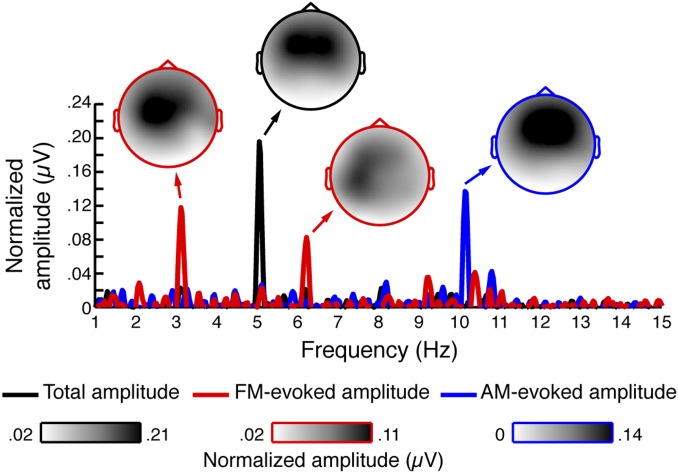

During performance of the gap-detection task, neural responses were recorded using EEG. Neural data were first examined independent of behavioral performance to test whether neural oscillations were entrained by the AM and FM in the stimulation. Fig. 3 shows amplitude spectra as a function of frequency resulting from fast Fourier transforms (FFTs) performed in two different ways to highlight entrained responses to either the AM or FM (SI Materials and Methods).

Fig. 3.

Neural oscillations were entrained by simultaneous FM and AM. Normalized grand-average total amplitude (black), FM-evoked amplitude (red), and AM-evoked amplitude (blue) plotted as a function of frequency. All amplitude peaks for which topographies are shown were statistically significant (P ≤ 0.001). The FFT data are plotted for electrode Cz.

We observed significant amplitude peaks corresponding to the AM stimulation frequency (5.075 Hz: z = 3.61, P < 0.001, r = 0.62, “total” amplitude) and its second harmonic (z = 3.61, P < 0.001, r = 62, “AM-evoked” amplitude), as well as to the FM stimulation frequency (3.1 Hz: z = 3.47, P < 0.001, r = 0.60, “FM-evoked” amplitude) and its second harmonic (z = 3.18, P = 0.001, r = 0.55, “FM-evoked” amplitude). Topographies for all entrained responses (Fig. 3) were consistent with auditory cortical generators (24, 25).

Entrained Neural Phase in Multiple Frequency Bands Comodulates Behavior.

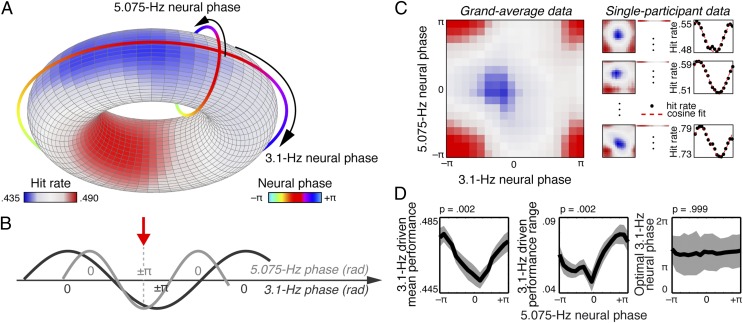

Entrained neural oscillatory phase for frequency bands centered on 3.1 and 5.075 Hz was extracted from single-trial neural responses just before the onset of the to-be-detected gap. Hit rates were then calculated as a function of joint 3.1-Hz and 5.075-Hz neural phase (Fig. 4; note that for analysis of neural phase, both 3.1-Hz and 5.075-Hz phase were treated as circular variables).

Fig. 4.

Entrained neural phase in multiple frequency bands comodulates behavior. (A) Toroidal representation of hit-rate modulation. 3.1-Hz neural phase is plotted on the larger, outer circle, and 5.075-Hz neural phase is plotted on the smaller, inner circle. (B) Schematic illustration of joint phase effects on behavioral performance. The red arrow indicates the combination of 3.1-Hz phase (dark gray) and 5.075-Hz phase (light gray) that yielded peak performance. (C) Analysis of single-participant hit-rate data for estimation of dependent measures. Single-trial hit rates as a function of 3.1-Hz neural phase were fit with cosine functions separately for each 5.075-Hz phase bin. (D) Dependent measures from cosine fits described in C. The 3.1-Hz driven mean performance (Left), performance range (Center), and optimal 3-Hz neural phase (Right), plotted as a function of 5.075-Hz neural phase. Plots of mean performance and performance range show mean ± SEM; plot of optimal 3.1-Hz neural phase shows mean ± circular SD.

Critically, gap-detection performance depended jointly on neural phase in the two frequency bands. Best hit rate across participants was consistently observed when the troughs of both entrained oscillations coincided (3.1 Hz: 2.72 ± 0.60 rad, mean ± variance; 5.075 Hz: −3.13 ± 0.75 rad, Fig. 4B), whereas the overall worst hit rate fell near the peak of both neural oscillations (3.1 Hz: −0.42 ± 0.60 rad; 5.075 Hz: 0.01 ± 0.75 rad).

Moreover, 3.1-Hz-driven mean performance and performance range were both strongly modulated by 5.075-Hz neural phase [performance range: F(17,272) = 2.89, P = 0.002, r = 0.37; mean performance: F(17,272) = 2.85, P = 0.002, r = 0.37; Fig. 4], confirming the interactive contributions of neural phase in the two frequency bands (see following). Optimal 3.1-Hz neural phase was not modulated by 5.075-Hz neural phase [F(17,288) = 0.19, P = 0.998, r = 0.13] because peak performance was always observed at the trough of the 3.1-Hz neural oscillation independent of the phase of the 5.075-Hz neural oscillation. The nonmodulation of optimal 3.1-Hz neural phase is consistent with best performance being associated with coincidence of the troughs in both entrained frequency bands.

We also analyzed potential effects of pre-gap phase on gap-evoked responses (ERPs). Notably, the magnitude of the auditory N1 component of the ERP was stronger for hits than misses and also exhibited a joint best pre-gap neural phase. The full analysis is included in the SI Data and Fig. S2.

Behavioral Comodulation Is Interactive and Frequency-Specific.

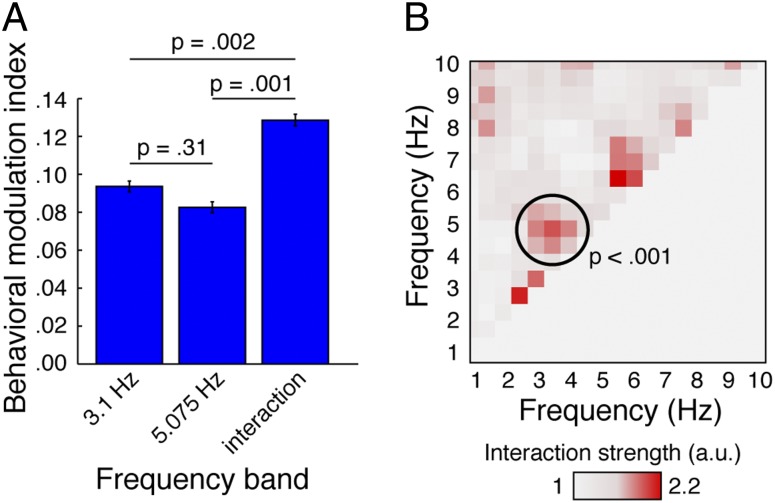

In a final analysis, we tested whether neural phase effects on gap-detection performance were both interactive and specific to the entrained frequency bands. To test for interactivity, we estimated the degree to which hit rates were modulated by neural phase in the 3.1-Hz frequency band alone, in the 5.075-Hz frequency band alone, and in the two frequency bands taken together (behavioral modulation index; Fig. 5A). Although behavioral modulation strength did not differ between the 3.1-Hz and 5.075-Hz frequency bands when considered independently [t(16) = 0.84, P = 0.41, r = 0.21], behavioral modulation was significantly stronger when taking both frequency bands together than for either frequency alone [versus 3.1 Hz: t(16) = 3.85, P = 0.001, r = 0.69; versus 5.075 Hz: t(16) = 5.88, P < 0.001, r = 0.83].

Fig. 5.

Behavioral comodulation was interactive and frequency-specific. (A) The behavioral modulation index was significantly larger for the combination of the 3.1-Hz and 5.075-Hz frequency bands than for either frequency band alone. Error bars indicate SEM. (B) Interaction strength (shown here normalized with respect to SD across participants) showed a peak at the combination of 3.1-Hz and 5.075-Hz frequency bands that was specific to the frequencies entrained by the stimulation.

To confirm interactivity was specific to the entrained neural frequency bands, we calculated an interaction strength metric for every pairwise combination of frequencies between 1 and 10 Hz (in 0.25-Hz steps). Critically, a peak in interaction strength was observed for the specific combination of 3.1 and 5.075 Hz (Fig. 5B). We confirmed the statistical significance of this effect by comparing interaction strength against all other pairwise combinations of frequencies using a permutation test [t(16) = 8.30, P < 0.001, r = 0.90]. It can be noted that interaction strength was also relatively high in two frequency–frequency bins falling near the diagonal. Interestingly, these relatively high interaction strengths also corresponded to entrained frequency bands; that is, to the interaction of the FM stimulation (3.1 Hz) and second harmonic (6.2 Hz) with themselves.

Behavioral Comodulation Does Not Depend on the Specific Frequencies of AM and FM.

Our choice of AM and FM frequencies was informed by knowledge of the characteristics of natural speech; that is, we chose a theta-band AM frequency in the range of the syllable envelope (20–22) and a delta-band FM frequency in the range of prosodic contour fluctuations (23). Thus, it might be argued that the observed comodulation of psychophysical performance was specific to our choice of a slow FM and a faster AM. To demonstrate the generalizability of our main result, we conducted another behavioral study that involved detecting gaps in rhythmically complex stimuli that exhibited an inverted AM–FM relation, in which modulation at a relatively slow AM rate (3.1 Hz) co-occurred with a relatively fast FM rate (5.075 Hz). Critically, we observed similar behavioral comodulation for these stimuli (SI Data and Fig. S3). Thus, the present results do not depend on our choice to mimic modulation rates in natural speech but, instead, generalize to more arbitrary and arguably less natural combinations of acoustic modulation.

Discussion

The current study demonstrates that the instantaneous phase of entrained neural oscillations in multiple frequency bands comodulates human listening behavior. Specifically, gap-detection hit rates were determined jointly by the specific phase–phase relationship of neural oscillations entrained by simultaneous 3.1-Hz FM and 5.075-Hz AM. Notably, behavioral comodulation was specific to frequencies that were entrained by the complex stimulus rhythm. Moreover, comodulation of performance was interactive, in that behavior was more strongly modulated by the combination of phases in both entrained frequency bands than by phase in either entrained frequency band alone.

Neural Entrainment by Complex Rhythmic Stimuli Comodulates Behavioral Performance.

In recent years, increasing scientific attention has been devoted to the hypothesis that entrainment of low-frequency neural oscillations by the temporal structure of time-varying stimuli supports perception through alignment of an oscillation’s excitable phase with predictable, and thus important, portions of the signal (1, 2, 16, 26). A limitation of these studies, however, is related to their exclusive focus on entrained neural phase in a single frequency band (7–10, 12, 14, 27). That is, although neural-phase effects on behavioral performance have been demonstrated for a wide range of frequencies covering the classic delta (2, 4, 12, 28), theta (7, 8), and alpha (7, 10, 14) bands, any single study has focused on only one frequency at a time. To be specific, although several studies have entrained neural oscillations at two or more different frequencies simultaneously (28, 29) or entertained the possibility of phase effects in multiple frequency bands (7), no study of which we are aware has examined phase–phase effects on behavioral performance.

In this regard, an important point to be made about the potential role of neural oscillations in perception is that natural environmental rhythms are complex. Hence, natural rhythms have the potential to act as pacemakers for neural oscillations in a number of frequency bands simultaneously (30). Consider, for example, speech processing, which is suggested to be supported by entrainment of theta-band neural oscillations by amplitude fluctuations corresponding to the syllable envelope (26, 31). Notably, however, speech is a rhythmically complex stimulus possessing not only theta-band amplitude fluctuations but also slower delta-band frequency fluctuations corresponding to prosodic contour (32, 33). Critically, the current data give credence to the potential of neural oscillations to be entrained by simultaneous environmental pacemakers (30) and support the role of neural phase in shaping perception in rhythmically complex situations.

With respect to the underlying neural source or sources of the observed effects, neural oscillations entrained by rates similar to those used in the current study have been localized to auditory cortex using magnetoencephalography (MEG) (34) and human electrocorticogram recordings (35), even for rhythmically complex speech stimuli (36). In general, the responsiveness of the auditory pathway to varying modulation rates is hierarchical in nature, with “higher” levels of the auditory pathway responding best to slower modulation rates (37). Thus, neural entrainment to stimuli with rates in the delta–theta bands would be unlikely at levels lower than primary auditory cortex, in which entrainment to delta-frequency tone sequences has been observed for macaque monkeys (2, 28). Although the current EEG data do not support a spatially precise localization of entrained neural oscillations, the topographies were consistent with auditory cortex generators (24, 25). We tentatively suggest that the interactive effect of phase in two frequency bands on gap-detection performance originates in primary/secondary auditory cortex. Slow neocortical oscillations originating in primary/secondary auditory cortices would become entrained by the complex modulation pattern of the stimulation (which would have been preserved by the auditory periphery), resulting in temporally complex fluctuations in excitability.

Phase Information Supports Stimulus Coding in Auditory Cortex.

In the current study, we probed for neural signatures of entrainment, using two different methods to calculate the amplitude spectrum of neural responses. Taking the results from both methods together, we observed significant peaks corresponding to both the FM (3.1 Hz) and AM (5.075 Hz) stimulation frequencies and their harmonics, confirming that neural oscillations were entrained simultaneously by both the AM and FM in our complex rhythmic stimulation. Notably, however, we did not observe a 5.075-Hz peak in the analysis of AM-aligned brain signals. The reason for this is that human auditory cortex relies on a phase-coding mechanism to efficiently code complex rhythmic signals containing simultaneous AM and FM (38–40); critically, the instantaneous phase of the entrained neural oscillation with respect to the AM codes for the instantaneous frequency of the FM.

More generally, neural phase information has been shown to be critically important for stimulus coding in auditory cortex (34, 41–44). In particular, a number of studies have shown that stimulus identity can be decoded on the basis of single-trial neural phase patterns, but not single-trial power envelopes. Because neural phase patterns evolve on a much faster timescale than neural power-envelope patterns, the capacity for information coding is much higher in the phase than in the power domain (42, 45, 46), making neural phase a highly effective medium for tracking and coding temporally complex auditory stimuli. The current data support the importance of time-varying neural phase patterns to code for complex stimuli early in auditory cortical processing.

Do Spectral Peaks at the Stimulation Frequencies Reflect Entrainment of Ongoing Neural Oscillations?

We have interpreted the presence of spectral peaks corresponding to the FM and AM stimulation frequencies (accompanied by oscillation of behavioral performance in these same frequency bands) as reflecting entrainment of ongoing (spontaneous) neural oscillations by rhythmic environmental stimulation (4, 18, 47). Evidence that environmental rhythmic structure interacts with ongoing brain rhythms comes from the satisfaction of a number of predictions derived from dynamic systems theory (18, 48). First, both empirical and modeling results demonstrate that the strength of the observed neural oscillation depends on the correspondence between the external stimulus rhythm and the ongoing neural rhythm. That is, stimulus-related neural oscillations are strongest and most quickly apparent when the environmental rhythm matches the natural frequency of the endogenous neural oscillator (47–50) and when the stimulation perturbs the ongoing neural oscillation in a specific phase (48, 49). Second, neural oscillations exhibit a self-sustaining quality (51) that can be observed in both neural recordings (28, 50) and behavioral fluctuations (52, 53). Additional support for the hypothesis that environmental rhythms entrain ongoing oscillations comes from the observation that the laminar distributions of entrained and ongoing neural oscillations are identical, suggesting a shared neural generator (4).

An alternative view assumes that the observed spectral peaks might instead reflect the summation of a series of invariant transient neural responses evoked by rhythmic stimulation independent of ongoing background activity (54). Evidence for this view comes from success in predicting the form of steady-state responses to isochronous auditory or visual stimuli from evoked responses to independent stimulus events embedded in temporally jittered sequences (54–56) and from failures to observe self-sustainment of neural oscillations after stimulus cessation (54). Moreover, a lack of evidence for ongoing oscillations at many frequencies at which a spectral peak can be observed is regarded as a further source of evidence for the “evoked” quality of the oscillatory activity (18). With respect to this latter point, it is important to note that an oscillatory system can display two characteristic behaviors in the absence of stimulation: the system will either oscillate spontaneously at its natural frequency or, in the case of a damped system, no ongoing oscillations will be visible (57). A damped oscillator can, however, be entrained by rhythmic stimulation. Thus, the absence of spontaneous neural oscillations is insufficient to conclude that neural oscillations do not reflect an interaction between the neural oscillatory system and the temporal structure in the environment.

Although the current data are insufficient to decide definitively in favor of one view or the other, we suggest mounting evidence supports the hypothesis that environmental rhythmic structure interacts with ongoing neural oscillations through entrainment. We expect that future work combining electrophysiology and computational modeling will further differentiate these alternatives and reveal the consequences for human perception and cognition.

Rhythm Reduces the Complexity of High-Dimensional Neural Dynamics.

Neural dynamics are necessarily complex and high dimensional, so that the neural system can flexibly restructure relations between oscillatory frequencies and brain regions to support different functions (19). One implication of this complexity is that it may be difficult to uncover the interactive effects that neural oscillations both within and across frequency bands exert on behavior. The approach taken here was to use rhythmic stimulation to reduce the dimensionality of neural dynamics and to constrain the state space within which information could be coded and processed. When we examined the degree to which behavior depended on neural phase in all pairwise combinations of frequency bands, we showed behavioral comodulation by neural phase that was specific to the frequencies that were present in our rhythmic stimulation and that, moreover, entrained neural oscillations.

We suggest that using rhythm as a means to organize neural oscillations is likely to reduce the complexity of neural phase effects on behavior. However, in the absence of rhythmic stimulation, that is, during continuous-mode processing (16, 17, 58), neural phase effects are likely to be much more complex than can be revealed by a singular focus on individual frequency bands. We suggest that the perspective adopted here (i.e., allowing for the possibility that complex interactions among frequency bands support perception and cognition) will in turn allow for a better understanding of these dynamics in potentially more complicated nonrhythmic situations.

Conclusions

The current study demonstrated a comodulation of human gap-detection performance by the phase–phase relationship of neural oscillations in two frequency bands entrained simultaneously by 3.1-Hz and 5.075-Hz acoustic modulations. In particular, best target-detection accuracy occurred when the respective troughs in both neural oscillations coincided. Critically, the interactive comodulation of behavior we observed was specific to the entrained frequencies, suggesting environmental rhythms reduce dimensionality of neural dynamics and clarify the relation of neural dynamics to psychophysical performance. In sum, the current results elucidate how fluctuating excitability in multiple entrained frequency bands shapes the effective neural processing of environmental stimuli.

Materials and Methods

Participants.

Seventeen native German speakers (8 female) with self-reported normal hearing took part in the study. All were right handed, and mean age was 25.2 y (SD = 2.7 y). Data for one additional participant were collected but were discarded because of a high number of rejected trials. All participants gave written informed consent and received financial compensation. The procedure was approved of by the ethics committee of the medical faculty of the University of Leipzig and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Stimuli.

Auditory stimuli were generated by MATLAB software (Mathworks, Inc.) at a sampling rate of 44,100 Hz. Stimuli were 14-s complex tones frequency modulated at a rate of 3.1 Hz and a depth of 37.5% (carrier-to-peak frequency distance normalized with respect to carrier frequency) and amplitude-modulated at a rate of 5.075 Hz and a depth of 100% (Fig. 1). The center frequency of the complex carrier signals was randomized from trial to trial (range, 800–1200 Hz). All stimuli were composed of 30 frequency components sampled from a uniform distribution with a 500-Hz range. The amplitude of each component decreased linearly with increasing distance to the center frequency. The onset phase of the stimulus was randomized from trial to trial, taking on one of eight equally spaced values between −π and π. All stimuli were peak-amplitude normalized and were presented at a comfortable level (∼60 dB SPL).

Two, three, or four near-threshold gaps were inserted into each 14-s stimulus (gap onset and offset were gated with half-cosine ramps) without changing the duration of the stimulus. Because gap detection is not equally easy in all phases of the AM (59), each gap was chosen to be centered either halfway up the rising phase or halfway down the falling phase of the AM, so that stimulus intensity was identical for the two gap locations, but phase was opposite. The result was that gaps fell randomly (approximately uniformly) into the phase of the FM. FM phase was sorted post hoc for analysis of behavioral data. Gaps never occurred in the first or final 1 s of the 14-s stimulus, and they were constrained to fall no closer to each other than 1.5 s.

Procedure.

Gap duration was first titrated for each individual listener such that detection performance was centered on 50%; the median individual threshold gap duration was 26 ms (± interquartile range = 9 ms). For the main experiment, EEG was recorded while listeners detected gaps embedded in 14-s long AM–FM stimuli by pressing a button when they detected a gap. Overall, each listener heard a total of 200 stimuli, and thus was presented with a total of 600 gaps. The experiment lasted about 3 h, including preparation of the EEG.

Data Acquisition and Analysis.

Behavioral data.

Behavioral data were recorded online by Presentation software (Neurobehavioral Systems, Inc.). “Hits” were defined as button-press responses that occurred no more than 1.5 s after the occurrence of a gap. Each gap occurrence was associated with a specific AM stimulus phase (rising; falling), simultaneously with a FM stimulus phase (approximately uniformly distributed). Hit rates were calculated separately for the rising phase and falling phase of the AM, and for each of 18 nonoverlapping phase bins of the frequency modulation, equally spaced between −π and π. Details regarding testing the relationship between behavioral performance and stimulus phase are provided in SI Materials and Methods.

Electroencephalography data.

The EEG was recorded from 26 Ag–AgCl scalp electrodes mounted on a custom-made cap (Electro-Cap International), according to the modified 10–20 system, and additionally from the left and right mastoids. Signals were recorded continuously with a passband of DC to 135 Hz and digitized at a sampling rate of 500 Hz (TMS international, Enschede, The Netherlands). Online reference was placed at the nose and the ground electrode was placed at the sternum. Electrode resistance was kept under 5 kΩ. All EEG data were analyzed offline, using custom Matlab scripts and Fieldtrip software (60).

Data were preprocessed twice: one pipeline was geared toward frequency-domain analysis of full-stimulus epochs, and the second was geared toward analysis of prestimulus phase in short epochs centered on targets (gaps, SI Materials and Methods and Fig. S4). To test for neural entrainment to the frequency and amplitude modulations in our stimulation, we examined amplitude spectra resulting from FFTs (SI Materials and Methods). To test changes in target (gap) detection performance resulting from the prestimulus phase in the entrained frequency bands, after conversion to the time-frequency domain using a wavelet convolution, trials were sorted into an 18 × 18 grid of overlapping bins (bin width = 0.6π) according to pre-gap neural phase in the frequency bands of interest (i.e., 3.1 Hz × 5.075 Hz). Then, we tested the joint effects of neural phase in both frequency bands on gap-detection hit rates using the procedure explained in the SI Materials and Methods.

Statistical testing.

For all parametric statistical tests, we first confirmed that the data conformed to normality assumptions using a Shapiro-Wilk test. When the normality assumption was violated, we used appropriate nonparametric tests. Effect sizes are reported as requivalent (61) (throughout, r), which is equivalent to a Pearson product-moment correlation for two continuous variables, to a point-biserial correlation for one continuous and one dichotomous variable, and to the square root of η2 (eta-squared) for ANOVAs. The only exception is for circular Rayleigh tests, where we report resultant vector length, r, as the corresponding effect size measure.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dunja Kunke and Steven Kalinke for assistance with data collection. This work was supported by a Max Planck Research Group grant from the Max Planck Society (to J.O.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1408741111/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Schroeder CE, Lakatos P. Low-frequency neuronal oscillations as instruments of sensory selection. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32(1):9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lakatos P, Karmos G, Mehta AD, Ulbert I, Schroeder CE. Entrainment of neuronal oscillations as a mechanism of attentional selection. Science. 2008;320(5872):110–113. doi: 10.1126/science.1154735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lakatos P, et al. The leading sense: Supramodal control of neurophysiological context by attention. Neuron. 2009;64(3):419–430. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lakatos P, et al. An oscillatory hierarchy controlling neuronal excitability and stimulus processing in the auditory cortex. J Neurophysiol. 2005;94(3):1904–1911. doi: 10.1152/jn.00263.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bishop GH. Cyclic changes in the excitability of the optic pathway of the rabbit. Am J Physiol. 1933;103:213–224. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buzsáki G, Draguhn A. Neuronal oscillations in cortical networks. Science. 2004;304(5679):1926–1929. doi: 10.1126/science.1099745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Busch NA, Dubois J, VanRullen R. The phase of ongoing EEG oscillations predicts visual perception. J Neurosci. 2009;29(24):7869–7876. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0113-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Busch NA, VanRullen R. Spontaneous EEG oscillations reveal periodic sampling of visual attention. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(37):16048–16053. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004801107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mathewson KE, Gratton G, Fabiani M, Beck DM, Ro T. To see or not to see: Prestimulus alpha phase predicts visual awareness. J Neurosci. 2009;29(9):2725–2732. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3963-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drewes J, VanRullen R. This is the rhythm of your eyes: The phase of ongoing electroencephalogram oscillations modulates saccadic reaction time. J Neurosci. 2011;31(12):4698–4708. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4795-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cravo AM, Rohenkohl G, Wyart V, Nobre AC. Temporal expectation enhances contrast sensitivity by phase entrainment of low-frequency oscillations in visual cortex. J Neurosci. 2013;33(9):4002–4010. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4675-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henry MJ, Obleser J. Frequency modulation entrains slow neural oscillations and optimizes human listening behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(49):20095–20100. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213390109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stefanics G, et al. Phase entrainment of human delta oscillations can mediate the effects of expectation on reaction speed. J Neurosci. 2010;30(41):13578–13585. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0703-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neuling T, Rach S, Wagner S, Wolters CH, Herrmann CS. Good vibrations: Oscillatory phase shapes perception. Neuroimage. 2012;63(2):771–778. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ng BSW, Schroeder T, Kayser C. A precluding but not ensuring role of entrained low-frequency oscillations for auditory perception. J Neurosci. 2012;32(35):12268–12276. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1877-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henry MJ, Herrmann B. Low-frequency neural oscillations support dynamic attending in temporal context. Timing & Time Perception. 2014;2:62–86. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schroeder CE, Wilson DA, Radman T, Scharfman H, Lakatos P. Dynamics of Active Sensing and perceptual selection. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2010;20(2):172–176. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2010.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thut G, Schyns PG, Gross J. Entrainment of perceptually relevant brain oscillations by non-invasive rhythmic stimulation of the human brain. Front Psychol. 2011;2:170. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singer W. Cortical dynamics revisited. Trends Cogn Sci. 2013;17(12):616–626. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greenberg S, Carvey H, Hitchcock L, Chang S. Temporal properties of spontaneous speech – A syllable-centric perspective. J Phonetics. 2003;31:465–485. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Houtgast T, Steeneken HJM. A review of the MTF concept in room acoustics and its use for estimating speech intelligibility in auditoria. J Acoust Soc Am. 1985;77:1069–1077. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krause JC, Braida LD. Acoustic properties of naturally produced clear speech at normal speaking rates. J Acoust Soc Am. 2004;115(1):362–378. doi: 10.1121/1.1635842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Munhall KG, Jones JA, Callan DE, Kuratate T, Vatikiotis-Bateson E. Visual prosody and speech intelligibility: Head movement improves auditory speech perception. Psychol Sci. 2004;15(2):133–137. doi: 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.01502010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Näätänen R, Picton T. The N1 wave of the human electric and magnetic response to sound: A review and an analysis of the component structure. Psychophysiology. 1987;24(4):375–425. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1987.tb00311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Picton TW, John MS, Dimitrijevic A, Purcell D. Human auditory steady-state responses. Int J Audiol. 2003;42(4):177–219. doi: 10.3109/14992020309101316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giraud A-L, Poeppel D. Cortical oscillations and speech processing: Emerging computational principles and operations. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15(4):511–517. doi: 10.1038/nn.3063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vanrullen R, Busch NA, Drewes J, Dubois J. Ongoing EEG phase as a trial-by-trial predictor of perceptual and attentional variability. Front Psychol. 2011;2:60. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lakatos P, et al. The spectrotemporal filter mechanism of auditory selective attention. Neuron. 2013;77(4):750–761. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.John MS, Dimitrijevic A, van Roon P, Picton TW. Multiple auditory steady-state responses to AM and FM stimuli. Audiol Neurootol. 2001;6(1):12–27. doi: 10.1159/000046805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gross J, et al. Speech rhythms and multiplexed oscillatory sensory coding in the human brain. PLoS Biol. 2013;11(12):e1001752. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peelle JE, Davis MH. Neural oscillations carry speech rhythm through to comprehension. Front Psychol. 2012;3:320. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bourguignon M, et al. The pace of prosodic phrasing couples the listener’s cortex to the reader’s voice. Hum Brain Mapp. 2013;34(2):314–326. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Obleser J, Herrmann B, Henry MJ. Neural oscillations in speech: Don't be enslaved by the envelope. Front Hum Neurosci. 2012;6(250):250. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Herrmann B, Henry MJ, Grigutsch M, Obleser J. Oscillatory phase dynamics in neural entrainment underpin illusory percepts of time. J Neurosci. 2013;33(40):15799–15809. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1434-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Besle J, et al. Tuning of the human neocortex to the temporal dynamics of attended events. J Neurosci. 2011;31(9):3176–3185. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4518-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zion Golumbic EM, et al. Mechanisms underlying selective neuronal tracking of attended speech at a “cocktail party”. Neuron. 2013;77(5):980–991. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.12.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Giraud A-L, et al. Representation of the temporal envelope of sounds in the human brain. J Neurophysiol. 2000;84(3):1588–1598. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.84.3.1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luo H, Wang Y, Poeppel D, Simon JZ. Concurrent encoding of frequency and amplitude modulation in human auditory cortex: MEG evidence. J Neurophysiol. 2006;96(5):2712–2723. doi: 10.1152/jn.01256.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patel AD, Balaban E. Temporal patterns of human cortical activity reflect tone sequence structure. Nature. 2000;404(6773):80–84. doi: 10.1038/35003577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Patel AD, Balaban E. Human auditory cortical dynamics during perception of long acoustic sequences: Phase tracking of carrier frequency by the auditory steady-state response. Cereb Cortex. 2004;14(1):35–46. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhg089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ng BSW, Logothetis NK, Kayser C. EEG phase patterns reflect the selectivity of neural firing. Cereb Cortex. 2013;23(2):389–398. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhs031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cogan GB, Poeppel D. A mutual information analysis of neural coding of speech by low-frequency MEG phase information. J Neurophysiol. 2011;106(2):554–563. doi: 10.1152/jn.00075.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Luo H, Poeppel D. Phase patterns of neuronal responses reliably discriminate speech in human auditory cortex. Neuron. 2007;54(6):1001–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kayser C, Montemurro MA, Logothetis NK, Panzeri S. Spike-phase coding boosts and stabilizes information carried by spatial and temporal spike patterns. Neuron. 2009;61(4):597–608. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schyns PG, Thut G, Gross J. Cracking the code of oscillatory activity. PLoS Biol. 2011;9(5):e1001064. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Howard MF, Poeppel D. Discrimination of speech stimuli based on neuronal response phase patterns depends on acoustics but not comprehension. J Neurophysiol. 2010;104(5):2500–2511. doi: 10.1152/jn.00251.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kanai R, Chaieb L, Antal A, Walsh V, Paulus W. Frequency-dependent electrical stimulation of the visual cortex. Curr Biol. 2008;18(23):1839–1843. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ali MM, Sellers KK, Fröhlich F. Transcranial alternating current stimulation modulates large-scale cortical network activity by network resonance. J Neurosci. 2013;33(27):11262–11275. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5867-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fröhlich F, McCormick DA. Endogenous electric fields may guide neocortical network activity. Neuron. 2010;67(1):129–143. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zaehle T, Rach S, Herrmann CS. Transcranial alternating current stimulation enhances individual alpha activity in human EEG. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(11):e13766. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Glass L. Synchronization and rhythmic processes in physiology. Nature. 2001;410(6825):277–284. doi: 10.1038/35065745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.de Graaf TA, et al. Alpha-band rhythms in visual task performance: Phase-locking by rhythmic sensory stimulation. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(3):e60035. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Landau AN, Fries P. Attention samples stimuli rhythmically. Curr Biol. 2012;22(11):1000–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Capilla A, Pazo-Alvarez P, Darriba A, Campo P, Gross J. Steady-state visual evoked potentials can be explained by temporal superposition of transient event-related responses. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(1):e14543. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bohórquez J, Özdamar O. Generation of the 40-Hz auditory steady-state response (ASSR) explained using convolution. Clin Neurophysiol. 2008;119(11):2598–2607. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Santarelli R, et al. Generation of human auditory steady-state responses (SSRs). II: Addition of responses to individual stimuli. Hear Res. 1995;83(1-2):9–18. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(94)00185-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Large EW. Resonating to musical rhythm: Theory and experiment. In: Grondin S, editor. Psychology of Time. Emerald Group Publishing Limited; Bingley, UK: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Henry MJ, Herrmann B. A precluding role of low-frequency oscillations for auditory perception in a continuous processing mode. J Neurosci. 2012;32(49):17525–17527. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4456-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moore BC. An Introduction to the Physiology of Hearing. 4th Ed Elsevier; London: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Oostenveld R, Fries P, Maris E, Schoffelen J-M. FieldTrip: Open source software for advanced analysis of MEG, EEG, and invasive electrophysiological data. Comput Intell Neurosci. 2011;2011:156869. doi: 10.1155/2011/156869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rosenthal R, Rubin DB. r equivalent: A simple effect size indicator. Psychol Methods. 2003;8(4):492–496. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.8.4.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.