Abstract

Purpose

The modified Glasgow Prognostic Score (mGPS) consisting of serum C-reactive protein and albumin levels, shows significant prognostic value in several types of tumors. We evaluated the prognostic significance of mGPS in 285 patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL), retrospectively.

Materials and Methods

According to mGPS classification, 204 patients (71.5%) had an mGPS of 0, 57 (20%) had an mGPS of 1, and 24 (8.5%) had an mGPS of 2.

Results

Our study found that high mGPS were associated with poor prognostic factors including older age, extranodal involvement, advanced disease stage, unfavorable International Prognostic Index scores, and the presence of B symptoms. The complete response (CR) rate after 3 cycles of R-CHOP chemotherapy was higher in patients with mGPS of 0 (53.8%) compared to those with mGPS of 1 (33.3%) or 2 (25.0%) (p=0.001). Patients with mGPS of 0 had significantly better overall survival (OS) than those with mGPS=1 and those with mGPS=2 (p=0.036). Multivariate analyses revealed that the GPS score was a prognostic factor for the CR rate of 3 cycle R-CHOP therapy (p=0.044) as well as OS (p=0.037).

Conclusion

mGPS can be considered a potential prognostic factor that may predict early responses to R-CHOP therapy in DLBCL patients.

Keywords: Modified Glasgow Prognostic Score, diffuse large B cell lymphoma, prognostic factor

INTRODUCTION

The most significant advance in the treatment of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) over the past 15 years has been the addition of rituximab to standard CHOP chemotherapy (R-CHOP).1,2 Before the rituximab era, the International Prognostic Index (IPI) was a widely accepted prognostic factor for patients with aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL) that were treated with the CHOP regimen, consisting of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone, or CHOP-like regimens.3,4 Because the R-CHOP regimen has become the current standard treatment for patients with DLBCL, the question of whether, and to what extent, prognostic factors change with novel treatment strategies has been debated.5

It is evident that inflammatory cells have powerful effects on tumor development. In neoplastic process, these cells are powerful tumor promoters, producing an attractive environment for tumor growth, facilitating genomic instability, and promoting angiogenesis.6,7 In particular, the systemic inflammatory response, evidenced by C-reactive protein (CRP), has an important role in the progression of a variety of tumors.8 The measurement of the systemic inflammatory response has subsequently been refined using a selective combination of CRP and albumin, and is termed the modified Glasgow Prognostic Score (mGPS). This score has been shown to have prognostic value in various tumors.9,10 Inflammatory cytokines play important roles in the pathogenesis of lymphoma and may reflect underlying biological processes, including tumor-host interactions with prognostic information.11,12 Recently, the prognostic significance of CRP in recurrent or refractory aggressive lymphoma as a response predictor of salvage therapy has been reported.13 It also has been shown that the mGPS is independent prognostic factor of survival outcome in extranodal natural killer (NK)/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type.14 To our knowledge, there are no reports on the significance of mGPS in DLBCL.

In this study, we evaluated the significance of mGPS as a predictor of response and survival in DLBCL patients treated with the R-CHOP regimen.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

We reviewed the clinical records of 285 newly-diagnosed DLBCL patients treated with the R-CHOP regimen at the Division of Hematology, Yonsei University Severance Hospital between October 2005 and 2010. None of the patients were infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Baseline serum CRP and albumin levels were available for all patients. Patients with clinical evidence of acute infection or chronic active inflammatory disease were excluded. Age (≤60 years vs. >60 years), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS, ≤1 vs. ≥2), B symptoms (present vs. absent), Ann Arbor clinical stage (≤2 vs. ≥3), extranodal involvement (numbers ≤1 vs. ≥2), bulky disease (largest diameter of the disease ≥10 cm, present vs. absent), bone marrow (BM) involvement at diagnosis (present vs. absent), serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels (normal vs. elevated), absolute lymphocyte count (ALC) at diagnosis (<1.0×109/L vs. ≥1.0×109/L), baseline serum CRP, albumin levels and IPI group (scored from 0 to 5 by age >60, stage ≥3, ECOG PS ≥2, LDH higher than upper limit of normal range and number of extranodal involvement ≥2) were collected and incorporated as potential prognostic factors in various analyses. We also collected data regarding comorbidities such as chronic hepatitis, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and hypertension that are associated with CRP elevation.15,16

Allocation of mGPS

Baseline serum CRP and albumin levels were collected by clinical routine measurements using nephelometric assays and bromocresol green dye-binding methods with an auto-analyzer according to the manufacturer's instructions. The mGPS was constructed, using CRP and albumin, as follows: patients with both elevated CRP (≥10 mg/L) and low albumin (<3.5 g/dL) levels were allocated a score of 2, patients with only CRP elevated (≥10 mg/L) were allocated a score of 1, and those with normal CRP levels were allocated a score of 0. The rationale and basis of the mGPS has been previously described.9

Treatment and response criteria

The standard R-CHOP regimen consists of rituximab (375 mg/m2) intravenously (IV), cyclophosphamide (750 mg/m2) IV, doxorubicin (50 mg/m2) IV, and vincristine (1.4 mg/m2; maximum dose of 2.0 mg) IV on day 1, followed by oral prednisolone (100 mg) on days 1 to 5. All patients received greater than 3 cycles of R-CHOP therapy. Eleven patients with stage I disease were treated with 3 cycles of R-CHOP followed by involved-field radiotherapy. In some patients that were not in complete remission (CR) after the last cycle of chemotherapy, residual masses were irradiated 4 weeks after completion of chemotherapy. Some patients (n=206) received 6 or 8 cycles of R-CHOP therapy.

Response was evaluated after at least 3 cycles of R-CHOP therapy. Evaluations were performed based on the following criteria. CR was defined as the disappearance of all clinical evidence of lymphoma, with no persistent disease-related symptoms. Partial response (PR) was defined as a decrease >50% in the sum of the products of the two longest diameters of all measurable lesions. Non-measurable lesions had to decrease by at least 50%. Progressive disease (PD) was defined as any increase >50% in the sum of the diameters of any measurable lesions or the appearance of new lesions. Stable disease (SD) was considered to be any condition intermediate between PR and PD.17

Statistical analyses

The statistical package SPSS 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all analyses. Differences between the groups were assessed using χ2-tests in cases of discrete variables or t-tests in cases of continuous variables. χ2-tests were used to analyze the relationship between mGPS and response rates. Overall survival (OS) was measured from the date of diagnosis to the date of death (from any cause) or to the last follow-up. Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined as the interval from the date of diagnosis to the date the patient experienced recurrence/progression of disease, death from any cause, or last follow-up. Univariate analyses of the effects of patient characteristics at diagnosis (including mGPS) upon survival were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and compared using log-rank tests. Cox proportional-hazards regression analyses were used to evaluate multivariate analyses. All factors associated with a p value <0.50 by univariate analyses were forced in multivariate analyses. p values <0.05 denoted statistically significant differences.

RESULTS

Patients characteristics

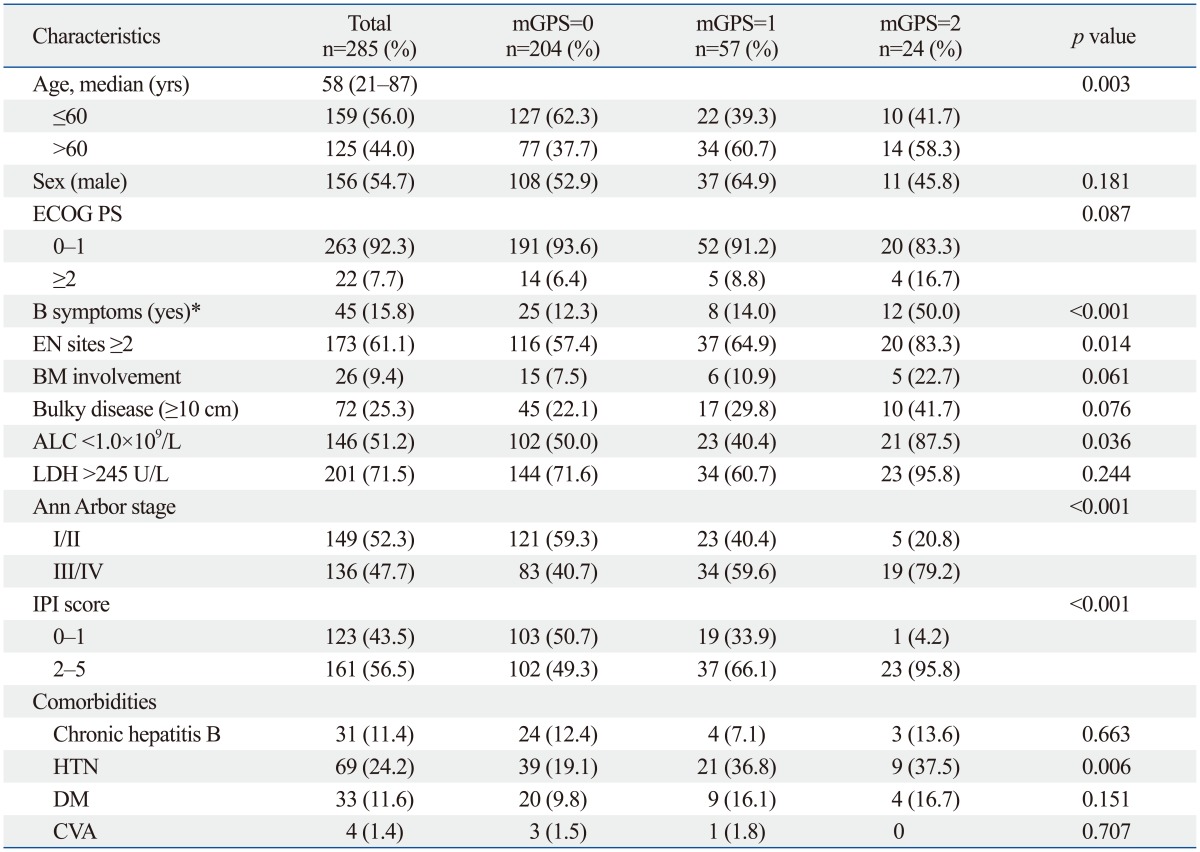

The study population included 285 patients (156 males and 129 females) with a median age of 58 years (range, 21-87 years). The characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 1. We classified the patients according to baseline serum CRP and albumin levels as mGPS=0 (n=204), mGPS=1 (n=57), and mGPS=2 (n=24) as described previously.9 Older age (>60 years) (p=0.003) and B symptoms (p<0.001) were more frequent in patients with GPS=2 compared to other patients. Patients with a higher GPS had significantly lower ALC (p=0.036), more than one extranodal (EN) site involvement (p=0.014), advanced disease stage, (p<0.001), and higher IPI risk group (p<0.001). Other characteristics showed no significant differences across groups with different mGPS (Table 1). No significant difference in the incidence of comorbidities associated with elevated CRP levels, such as chronic hepatitis B, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease (except hypertension) existed among the three groups. However, mean serum CRP levels were comparable among patients with hypertension versus patients without hypertension (mean±SD, 19.93±34.80 mg/L vs. 12.43±30.11 mg/L, p=0.084) (data not shown).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics According to mGPS Level

mGPS, modified Glasgow Prognostic Score; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance status; EN, extranodal; BM, bone marrow; ALC, absolute lymphocyte count; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; IPI, International Prognostic Index; HTN, hypertension; DM, diabetes mellitus; CVA, cardiovascular disease.

*B symptoms, presence of at least one of the following: night sweats, weight loss >10% over 6 months, and recurrent fever >38.3℃.

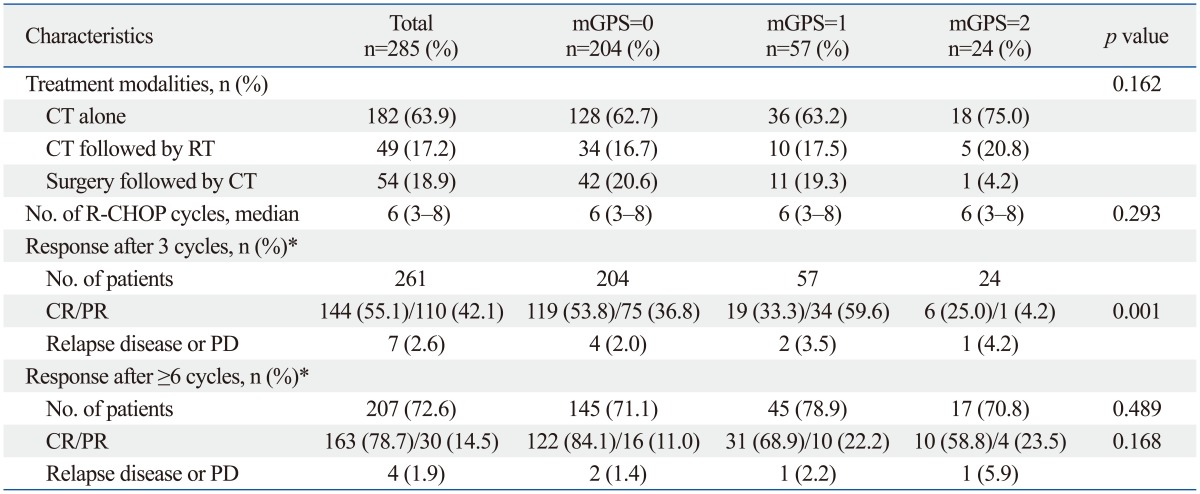

Treatment modalities and response

The primary treatment modalities were as follows: 49 cases (17.2%) received chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy, 182 cases (63.9%) received chemotherapy alone, and 54 cases (18.9%) received surgery (i.e., total or partial removal of apparent lymphoma) followed by chemotherapy (Table 2). No significant differences were found in the treatment modalities according to mGPS (p=0.162).

Table 2.

Response to R-CHOP Therapy According to mGPS Level

mGPS, modified Glasgow Prognostic Score; CT, chemotherapy; RT, radiotherapy; CR, complete response; PR, partial response; PD, progressive disease.

*Response to treatment were categorized as defined by Cheson, et al.17

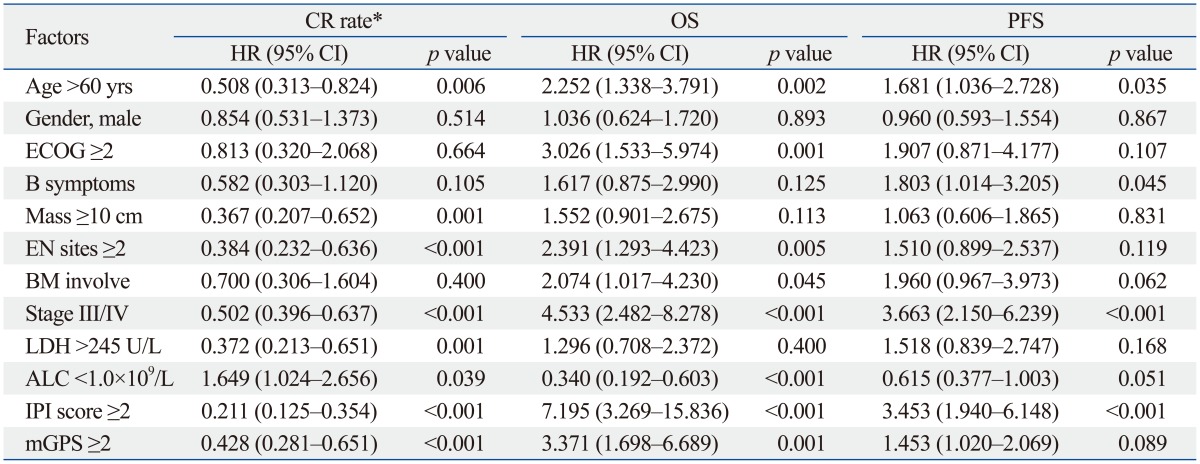

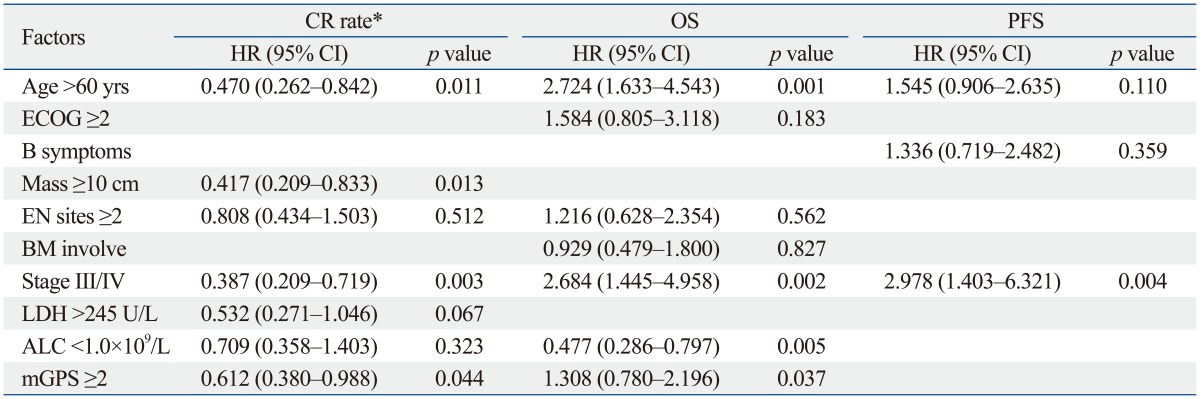

The responses to R-CHOP therapy are summarized in Table 2. The median number of cycles of R-CHOP therapy was 6 (range, 3-8 cycles). The median response duration was 39.1 months (range, 28.5-49.8 months). The responses after 3 cycles of R-CHOP therapy were evaluated in 261 patients, and the CR rate was 55.1%. CR rates inpatients with mGPS=0, mGPS=1, and mGPS=2 were 53.8% (119/204), 33.3% (19/57), and 25.0% (6/24), respectively. The CR rate in response to 3 cycles of R-CHOP therapy in patients with mGPS=2 group was significantly lower compared to patients in the other groups (p=0.001). In univariate analyses, older age (>60 years) (p=0.006), bulky disease (largest diameter of the disease ≥10 cm) (p=0.001), ≥2 EN involved (p<0.001), advanced stage (p<0.001), elevated LDH (p=0.001), baseline ALC <1.0×109/L (p=0.039), and mGPS=2 (p<0.001) significantly influenced CR rate after 3 cycles of R-CHOP therapy (Table 3). In multivariate analyses, older age [hazard ratio (HR)=0.470; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.262 to 0.842; p=0.011], advanced stage (HR=0.387; 95% CI, 0.209 to 0.719; p=0.003), bulky disease (HR=0.417; 95% CI, 0.209 to 0.833; p=0.013), and mGPS ≥2 (HR=0.612; 95% CI, 0.380 to 0.988; p=0.044) retained independent adverse prognostic values for the CR rate to 3 cycles of R-CHOP therapy (Table 4).

Table 3.

Univariate Analyses Based on CR Rate and Survival

CR, complete response; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; EN, extranodal; BM, bone marrow; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; ALC, absolute lymphocyte count; IPI, International Prognostic Index; mGPS, modified Glasgow Prognostic Score; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

*CR rate compared to 3 cycles of R-CHOP therapy.

Table 4.

Multivariate Analyses on CR Rate and Survival

CR, complete response; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; EN, extranodal; BM, bone marrow; LDH, serum lactate dehydrogenase level; ALC, absolute lymphocyte count; mGPS, modified Glasgow Prognostic Score; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

*CR rate compared to 3 cycles of R-CHOP therapy.

Some patients (n=207, 72.6%) received greater than 5 cycles of R-CHOP therapy. Response after 6 or more cycles of R-CHOP therapy was evaluated in 197 patients. The CR rates (58.8%) in patients with mGPS=2 tend to be lower than in those with mGPS=0 and mGPS=1 (84.1% vs. 68.9%), although it was not statistically significant (p=0.168) (Table 2).

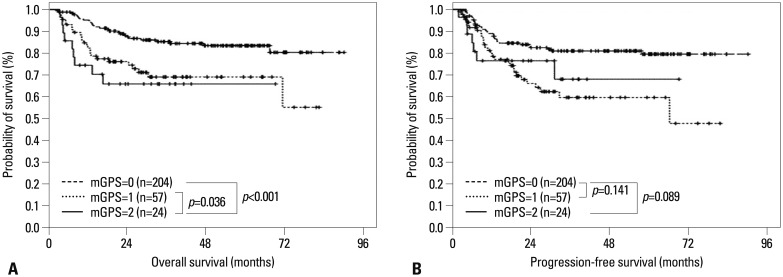

Overall survival

The median follow-up period was not achieved in all patients and 60 patients (21.1%) died. Fig. 1 shows Kaplan-Meier curves for OS stratified according to mGPS. The 5-year OS rates for patients with mGPS=0, mGPS=1, and mGPS=2 were 80.9%, 74.1%, and 54.7%, respectively (p=0.001) (Fig. 1A, Table 3). Patients with mGPS=0 had a significantly better OS than those with mGPS=2 (p<0.001). Moreover, the 5-year OS rate for patients with mGPS=1 was better than patients with mGPS=2 (74.1% vs. 54.7%, p=0.036). The OS rate was significantly worse in elderly patients and patients with poor PS, increased LDH, multiple EN involvement sites, BM involvement, advanced stage, low ALC at diagnosis, unfavorable IPI, and mGPS ≥2 (Table 3). Multivariate analyses for OS revealed that older age (HR=2.724; 95% CI, 1.633 to 4.543; p=0.001), advanced stage (HR=2.684; 95% CI, 1.445 to 4.958; p=0.002), lower ALC (HR=0.477; 95% CI, 0.286 to 0.797; p=0.005), and mGPS ≥2 (HR=1.308; 95% CI, 0.780 to 2.196; p=0.037) were independently associated with shorter OS.

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves of overall survival and progression-free survival comparisons. (A) Overall survival and (B) progression-free survival according to mGPS levels in DLBCL patients treated with the R-CHOP regimen. mGPS, modified Glasgow Prognostic Score; DLBCL, diffuse large B cell lymphoma.

Progression-free survival

The 5-year PFS rate was 76.1% in patients with mGPS=0, 62.3% in patients with mGPS=1, and 66.4% in patients with mGPS=2. Patients with lower mGPS tended to have a longer PFS compared to those with higher mGPS, although it was statistically insignificant (p=0.112) (Fig. 1B, Table 3). Patients with stage III or higher disease had inferior PFS compared to those with stage I or II disease (5-year PFS, 84.4% vs. 59.2%; p<0.001), and disease stage was the only prognostic factor for PFS in Cox's proportional hazard model (HR=2.978; 95% CI, 1.403 to 6.321; p=0.004). Although patients who were older had B symptoms at diagnosis, or unfavorable IPI score showed a tendency of lower PFS (Table 3), stepwise multiple logistic regression analyses did not identify any other independent prognostic factors for PFS (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

Since the introduction of the R-CHOP regimen, it has become the standard treatment for patients with DLBCL.1,2 However, this raises concerns regarding the utility of previously identified prognostic factors, such as the IPI. In large cohort studies, the systemic inflammatory response, as evidenced by the mGPS, is a powerful prognostic factor in patients with cancer. mGPS is simple to measure, routinely available, and well standardized worldwide.10,18 It also has been shown that the mGPS is an independent prognostic factor of survival outcome in extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type.14 In this study, we observed for the first time that mGPS was significantly associated with the response rate to R-CHOP therapy and survival outcomes in DLBCL patients treated with the R-CHOP regimen.

B-cell lymphoma present as tumors with a variable inflammatory infiltrate that includes effector and regulatory T cells, macrophages, and dendrite cells.19,20,21,22 Recent studies demonstrate that the role of the host inflammatory response is not limited to solid tumors but also shapes the biological characteristics of B-cell lymphoma, including DLBCL.23,24

CRP is a member of the class of acute-phase reactants, and due to its sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility in hospital laboratories, is commonly used to assess the magnitude of the systemic inflammatory response. Elevated CPR concentration has prognostic value in gastrointestinal, urinary, bladder, pancreas, renal, and lung cancer,9 as well aslymphoma.13 CRP synthesis in liver is promoted by several proinflammatory cytokines, including interleukin-1, tumor necrosis factor-1, and interleukin-6 (IL-6).25,26,27 IL-6 plays an important role in the pathogenesis of lymphoma and is an independent indicator of long-term outcome in NHL.28,29,30 Evaluation of serum CRP levels constitutes a powerful and interesting biomarker to evaluate inflammatory prognostic factors that appear to be associated with IL-6.13,31

There was a negative correlation between CRP and albumin levels in cancer patients, reflecting both systemic inflammation and the amount of lean tissue.9,32 Loss of lean tissue in cancer patients has been recognized to result in poor performance status.32 Poor performance status (ECOG PS ≥2) was one of five factors in the IPI score.3

Our study showed that regarding the response to therapy and survival outcome, high mGPS was associated with poor prognostic factors including older age (>60 years), multiple EN involved, advanced disease stage, and the presence of B symptoms. These results indicate that mGPS may reflect a tumor's growth and invasive potential (tumor stage and number of EN sites), the patient's response to the tumor (status for B symptoms), and the patient's ability to tolerate intensive therapy (age). In this study, mGPS, bulky disease, and disease stage were shown to be significant prognostic parameters on the CR rate after 3 cycles of R-CHOP therapy. However, after 6 or more cycles of R-CHOP therapy, there was no significant difference in CR rate among each mGPS group. The comparable PFS according to mGPS may be explained by the result of comparable CR rates after 6 or more cycles of R-CHOP therapy. Consistent with previous studies,3,4,33,34 our results reveal that IPI score, age, and baseline ALC were predictive factors of OS. Additionally, high mGPS was associated with inferior OS independent of other prognostic factors (p=0.037).

In the present study, patients with clinical evidence of acute infection or chronic active inflammatory disease that was associated with elevated CRP levels were excluded. There were no significant differences in the incidence of comorbidities that can increase serum CRP levels,15,16 such as chronic hepatitis B, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease (except hypertension) among mGPS groups. However, the mean value of serum CRP levels was comparable among patients with hypertension compared to those without hypertension (mean±SD, 19.93±34.80 mg/L vs. 12.43±30.11 mg/L, p=0.084).

In conclusion, to our knowledge, we have demonstrated for the first time that mGPS can be considered a potential prognostic factor that may predict early responses to R-CHOP therapy in DLBCL patients. We also demonstrated mGPS can predict overall survival in patients with DLBCL treated with the R-CHOP regimen. These findings may be clinically useful for predicting survival outcomes in DLBCL. A more accurate assessment would be likely if mGPS is combined with other prognostic factors. Additional prospective studies are needed to confirm the clinical potential of mGPS as prognostic factor in DLBCL.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

CJW was the principal investigator and takes primary responsibility for the paper. MYH, CJW, KJS, and KSJ recruited patients to the study. KYD and HDY participated in the statistical analyses. KYR, HSY, and JJE coordinated the research. KYD wrote the paper. There is no funding to declare.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Coiffier B, Lepage E, Briere J, Herbrecht R, Tilly H, Bouabdallah R, et al. CHOP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CHOP alone in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:235–242. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Habermann TM, Weller EA, Morrison VA, Gascoyne RD, Cassileth PA, Cohn JB, et al. Rituximab-CHOP versus CHOP alone or with maintenance rituximab in older patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3121–3127. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.A predictive model for aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. The International Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Prognostic Factors Project. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:987–994. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309303291402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shipp MA. Prognostic factors in aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: who has "high-risk" disease? Blood. 1994;83:1165–1173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loeffler M, Shipp M, Stein H. 2. Report on the workshop: "Clinical consequences of pathology and prognostic factors in aggressive NHL". Ann Hematol. 2001;80(Suppl 3):B8–B12. doi: 10.1007/pl00022797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature. 2002;420:860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature01322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mantovani A, Romero P, Palucka AK, Marincola FM. Tumour immunity: effector response to tumour and role of the microenvironment. Lancet. 2008;371:771–783. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60241-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roxburgh CS, McMillan DC. Role of systemic inflammatory response in predicting survival in patients with primary operable cancer. Future Oncol. 2010;6:149–163. doi: 10.2217/fon.09.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McMillan DC. Systemic inflammation, nutritional status and survival in patients with cancer. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2009;12:223–226. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e32832a7902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Proctor MJ, Morrison DS, Talwar D, Balmer SM, Fletcher CD, O'Reilly DS, et al. A comparison of inflammation-based prognostic scores in patients with cancer. A Glasgow Inflammation Outcome Study. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:2633–2641. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levens JM, Gordon J, Gregory CD. Micro-environmental factors in the survival of human B-lymphoma cells. Cell Death Differ. 2000;7:59–69. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Voorzanger N, Touitou R, Garcia E, Delecluse HJ, Rousset F, Joab I, et al. Interleukin (IL)-10 and IL-6 are produced in vivo by non-Hodgkin's lymphoma cells and act as cooperative growth factors. Cancer Res. 1996;56:5499–5505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suzuki K, Terui Y, Nishimura N, Mishima Y, Sakajiri S, Yokoyama M, et al. Prognostic value of C-reactive protein, lactase dehydrogenase and anemia in recurrent or refractory aggressive lymphoma. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2013;43:37–44. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hys194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li YJ, Jiang WQ, Huang JJ, Xia ZJ, Huang HQ, Li ZM. The Glasgow Prognostic Score (GPS) as a novel and significant predictor of extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type. Am J Hematol. 2013;88:394–399. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gortney JS, Sanders RM. Impact of C-reactive protein on treatment of patients with cardiovascular disease. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2007;64:2009–2016. doi: 10.2146/ajhp060542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee CC, Adler AI, Sandhu MS, Sharp SJ, Forouhi NG, Erqou S, et al. Association of C-reactive protein with type 2 diabetes: prospective analysis and meta-analysis. Diabetologia. 2009;52:1040–1047. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1338-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheson BD, Horning SJ, Coiffier B, Shipp MA, Fisher RI, Connors JM, et al. NCI Sponsored International Working Group. Report of an international workshop to standardize response criteria for non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1244. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.4.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Forrest LM, McMillan DC, McArdle CS, Angerson WJ, Dunlop DJ. Evaluation of cumulative prognostic scores based on the systemic inflammatory response in patients with inoperable non-small-cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:1028–1030. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dunn GP, Bruce AT, Sheehan KC, Shankaran V, Uppaluri R, Bui JD, et al. A critical function for type I interferons in cancer immunoediting. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:722–729. doi: 10.1038/ni1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dunn GP, Koebel CM, Schreiber RD. Interferons, immunity and cancer immunoediting. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:836–848. doi: 10.1038/nri1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morse HC, 3rd, Kearney JF, Isaacson PG, Carroll M, Fredrickson TN, Jaffe ES. Cells of the marginal zone--origins, function and neoplasia. Leuk Res. 2001;25:169–178. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(00)00107-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zangani MM, Frøyland M, Qiu GY, Meza-Zepeda LA, Kutok JL, Thompson KM, et al. Lymphomas can develop from B cells chronically helped by idiotype-specific T cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1181–1191. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lech-Maranda E, Baseggio L, Bienvenu J, Charlot C, Berger F, Rigal D, et al. Interleukin-10 gene promoter polymorphisms influence the clinical outcome of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2004;103:3529–3534. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-06-1850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lech-Maranda E, Bienvenu J, Michallet AS, Houot R, Robak T, Coiffier B, et al. Elevated IL-10 plasma levels correlate with poor prognosis in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Eur Cytokine Netw. 2006;17:60–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Balkwill F, Mantovani A. Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow? Lancet. 2001;357:539–545. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008;454:436–444. doi: 10.1038/nature07205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell. 2010;140:883–899. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seymour JF, Talpaz M, Cabanillas F, Wetzler M, Kurzrock R. Serum interleukin-6 levels correlate with prognosis in diffuse large-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:575–582. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.3.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fayad L, Cabanillas F, Talpaz M, McLaughlin P, Kurzrock R. High serum interleukin-6 levels correlate with a shorter failure-free survival in indolent lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 1998;30:563–571. doi: 10.3109/10428199809057568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamamura M, Yamada Y, Momita S, Kamihira S, Tomonaga M. Circulating interleukin-6 levels are elevated in adult T-cell leukaemia/ lymphoma patients and correlate with adverse clinical features and survival. Br J Haematol. 1998;100:129–134. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1998.00538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Legouffe E, Rodriguez C, Picot MC, Richard B, Klein B, Rossi JF, et al. C-reactive protein serum level is a valuable and simple prognostic marker in non Hodgkin's lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 1998;31:351–357. doi: 10.3109/10428199809059228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McMillan DC. An inflammation-based prognostic score and its role in the nutrition-based management of patients with cancer. Proc Nutr Soc. 2008;67:257–262. doi: 10.1017/S0029665108007131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim DH, Baek JH, Chae YS, Kim YK, Kim HJ, Park YH, et al. Absolute lymphocyte counts predicts response to chemotherapy and survival in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Leukemia. 2007;21:2227–2230. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oki Y, Yamamoto K, Kato H, Kuwatsuka Y, Taji H, Kagami Y, et al. Low absolute lymphocyte count is a poor prognostic marker in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and suggests patients' survival benefit from rituximab. Eur J Haematol. 2008;81:448–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2008.01129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]