Abstract

Purpose

Augmentation rhinoplasty using alloplastic materials is a relatively common procedure among Asians. Silicon, expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (Gore-tex®), and porous high density polyethylene (Medpor®) are most frequently used materials. This study was conducted to analyze revisional rhinoplasty cases with alloplastic materials, and to investigate the usage of alloplastic materials and their complications. We also reviewed complications caused by various materials used in plastic surgery while operating rhinoplasty.

Materials and Methods

We report 581 cases of complications rhinoplasty with alloplastic implants and review of the literature available to offer plastic surgeons an overview on alloplastic implant-related complications.

Results

Among a total 581 revisional rhinoplasty cases reviewed, the alloplastic materials used were silicone implants in 376, Gore-tex® in 183, and Medpor® in 22 cases. Revision cases and complications differed according to each alloplastic implant.

Conclusion

Optimal alloplastic implants should be used in nasal structure by taking into account the properties of the materials for the goal of minimizing their complications and revision rates. A thorough understanding of the mechanism involved in alloplastic material interaction and wound healing is the top priority in successfully overcoming alloplastic-related complications.

Keywords: Rhinoplasty, implant, postoperative complications

INTRODUCTION

While reduction and corrective rhinoplasty are the most prevalent rhinoplastic surgery among Caucasians, augmentation rhinoplasty is one of the most commonly performed cosmetic procedures in Asians, and the materials used for augmentation is an important issue for debates among Asian plastic surgeons who perform rhinoplasty.

Although there is no argument that autologous tissues are the most ideal augmentation material, they have limited availability, unpredictable resorption rates, difficulty of handling, and frequently donor site morbidity. Hence, alloplastic materials are frequently used as an alternative.

Alloplastic materials are surely an attractive tool for augmentation rhinoplasty. However, there has been continued debate through various studies on their efficacy, complications and limited usage. Many materials had been introduced based on rhinoplastic surgeons' preferences, and various results had been proposed through many meta-studies.

We examined various problems encountered in Asians, using the most commonly used alloplastic materials including silicon, Gore-tex® (Surgiform Technology, SC, USA), and Medpor® (Stryker Corporate, MI, USA), in previous rhinoplasty cases to provide an overview to share with other rhinoplastic surgeons. This study is not about operation techniques of rivisional rhinoplasty. This is a review on complications caused by various materials used in plastic surgery while operating rhinoplasty.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study examined 581 cases of patients who had visited the department of plastic surgery at Dong-A University Hospital and Nose Aesthetic Plastic Surgery Clinic for the past 10 years from March 2003 to March 2013 and experienced complications associated with alloplastic materials. There were 56 men and 525 women. The patients' age ranged from 21 to 62 years (mean: 28 years). The follow-up period was 1.5 years to 13 years (mean: 3.4 years). All of these subjects came to our department for revisional rhinoplasty after augmentation rhinoplasty with alloplastic materials. Their clinical characteristics were analyzed retrospectively, including the types of alloplastic materials, the pattern of complications from each alloplastic material used through their medical charts and photo analyses, and histopathologic analyses. Until now, rhinoplastic surgeons mostly used silicone implant, expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (Gore-tex®), and porous high density polyethylene (Medpor®). Various journals were reviewed in regard with alloplastic materials.

RESULTS

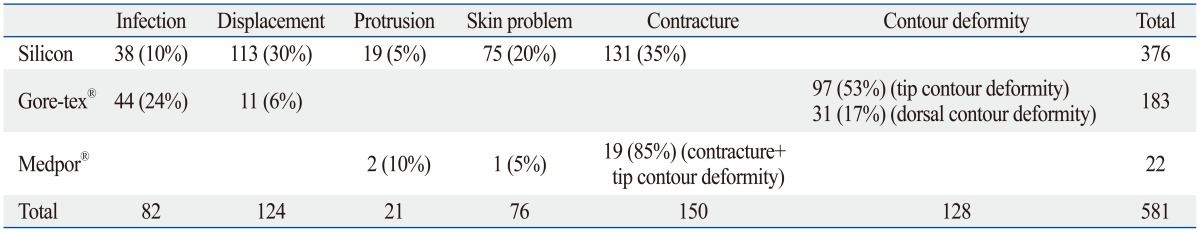

The number of revisional cases using each alloplastic material out of total 581 cases was 376 cases with silicone implant; 183, Gore-tex®; and 22, Medpor®; 122 (Table 1).

Table 1.

The Number of Complications Using Alloplstic Materials

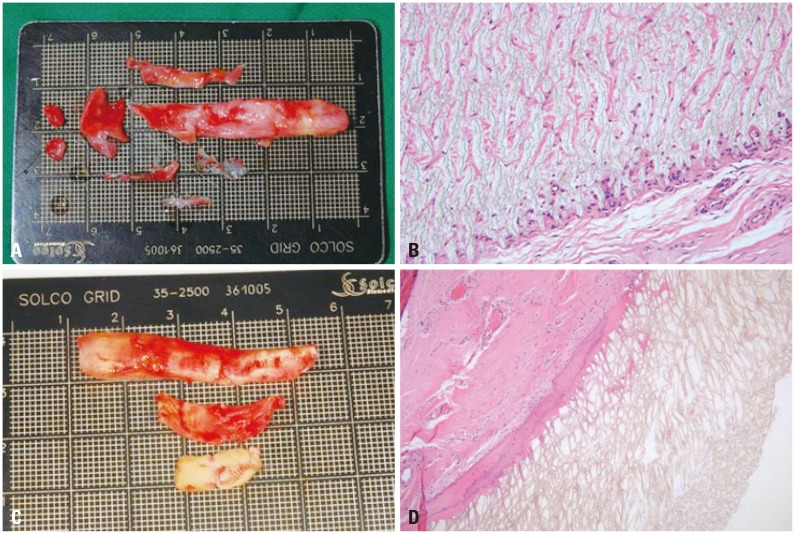

Complications from silicone implants included infection in 38 cases, deviation (implant shift) in 113 cases, protrusion in 19 cases, skin problem in 75 cases, and contracture in 131 cases; therefore, these complications were divided into five categories. The skin problem at the tip and protrusion were observed by using L-shape silicon. Protrusion through septal mucosa was observed in 6 cases and silicone implants were exposed from dorsal augmentation due to contracture. Most of the silicone implants were used for dorsal augmentation, and the majority of cases resulting from revision were short nose due to capsular contracture and an obvious deviation of the implants (Figs. 1 and 2).

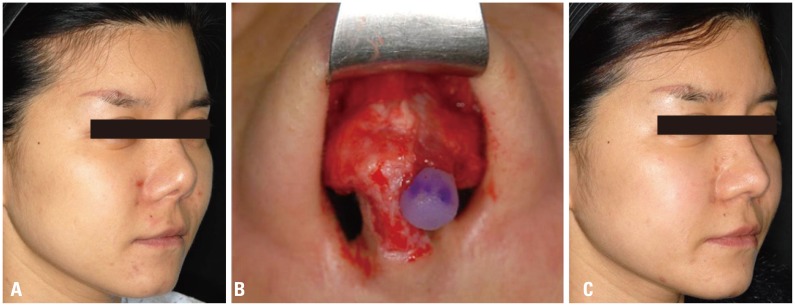

Fig. 1.

Removed silicone implants, gross and histopathologic findings. (A) Fibrous capsule with implant, 30 years, gross finding. (B) Fibrous capsule with implant, 30 years, histopathologic finding. (C) Calcified capsule with implant, 20 years, gross finding. (D) Calcified capsule with implant, 20 years, histopathologic finding (H-E, ×200).

Fig. 2.

Problem case associated with silicone implant. (A) Preoperative view, tissue contraction, implant shift. (B) Intraoperative view, contraction with implant shift. (C) Postoperative view.

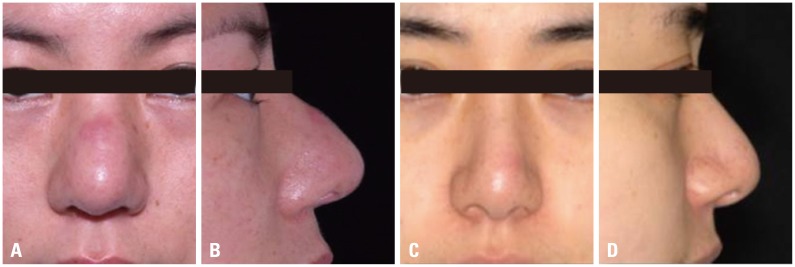

Complications from Gore-tex® were divided into infection, protrusion, displacement, tip problem, and dorsal problem with 44, 0, 11, 97, and 31 cases, respectively. With this material, the majority of revision were to correct contour deformity of the tip and dorsum. A patient who had undergone dorsal augmentation with Gore-tex® and revision three years later showed tissue focal ingrowth, so it was difficult to remove the implant cleanly (Figs. 3 and 4).

Fig. 3.

Gross and histopathologic findings of removed Gore-tex®, 3 yrs. (A) Gross finding of Gore-tex®, 3 yrs after rhinoplasty. (B) Histopathologic findings of tissue ingrowth into the Gore-tex® (H-E, ×200). (C) Gross finding of calcified capsule with Gore-tex®, 3 yrs after rhinoplasty. (D) Histopathologic findings of calcification of Gore-tex® (H-E, ×200).

Fig. 4.

Problem case associated with Gore-tex®. (A) Preoperative frontal view. (B) Preoperative lateral view. (C) Postoperative frontal view. (D) Postoperative lateral view.

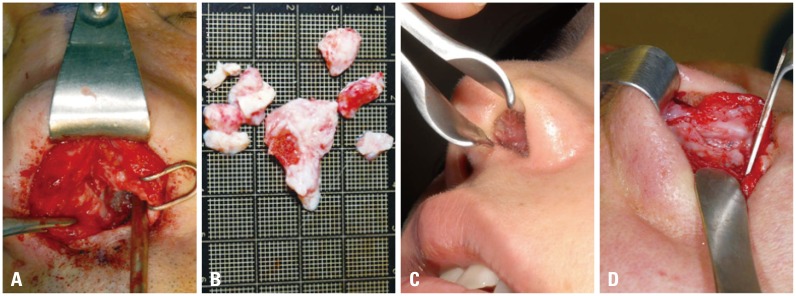

Those who had been referred to our hospital for revision with their initial rhinoplasty using Medpor® showed that they received a single or multiple procedures including septal extension graft (SEG), columellar strut, batten graft, and spreader graft. Their complications included protrusion of Medpor® onto the mucosa toward the septum in 2 cases. Excluding one case of spreader graft with Medpor® who visited our hospital three years ago because of skin problem from allergic dermatitis around the nose to the centers of both cheeks, 19 cases showed a combination of complications including skin problem, tip contour deformity, and contracture (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Problem case associated with Medpor®. (A) Intraoperative view. Firmly attached to adjacent tissue. (B) Removed Medpor® with adhesive tissue. (C) Protrusion of Medpor® to septal mucosa. (D) Tissue- Medpor® adhesion.

DISCUSSION

The most common rhinoplasty in Asians is augmentation rhinoplasty. And various alloplastic materials are used for tissue augmentation. Typically used materials are silicone implants, Gore-tex® and Medpor® with a great many studies on each material. We herein evaluated the usefulness of alloplastic materials and their pitfalls focusing on their complication.

Silicone implants are highly biocompatibile, non-toxic, non-immunogenic, easily formable, chemically stable, and inexpensive, therefore, they have been used widely for the plastic surgery field since the 1960's with many studies reporting the advantage of silicone implants for augmentation rhinoplasty.1,2,3 However, the complications, including infection, capsular contracture, extrusion, implant shift, and calcification, have been reported at certain rates with the issues arising from fibrous, calcified capsules. Many studies reported up to 36% of incidence of various complications such as infection, calcification, contracture, extrusion, and shift.1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8 We believe that calcification and capsule are the major culprit for the late complications including contracture, extrusion, and shift with time. However, there are revision cases where silicone implants were removed, wtill showing the fining of calcification due to warping and other alloplastic material used along with silicone; thus, individual differences in calcification, a normal tissue reaction, appear to affect complications.

Since its application in rhinoplasty in 1989 by Rothstein and Jacob, Gore-tex® has been used by many practitioners for its good biocompatibility, no allergenic property, ease in formation, and structural stability. Gore-tex® has 10-30 µm size pores and capillaries, collagen, and connective tissues, including fibroblasts, which grow into the pores, therefore, it has been attractive materials to surgeons due to little inflammatory response and capsular contracture. However, various complications have been reported regarding the application of Gore-tex® in rhinoplasty. Godin, et al.9 reported a 3.2% complication rate in 309 patients with nasal augmentation using Gore-tex® during a 10 year period. Conrad and Gillman10 reported a 3.7% infection rate for 6 years. A 2006 multicenter evaluation of 853 patients in Korea found a 2.5% complication rate.11 Jang, et al.12 examined the foreign body reaction, focal tissue ingrowth, calcification, decomposition and thickness changes with Gore-tex®, with findings similar to our histopathologic results. Yang, et al.13 stated that the use of this material needs to be reconsidered, because of its weakness against physical shock, no confirmation of ingrowth of the fibrovascular tissue into its pores, difficulty in removal, and volume reduction. Based on their cases and most literature study, Hong, et al.14 concluded that the use of Gore-tex® would have similar complications rates to those from silicone implant.

For its good tissue biocompatibility, ingrowth of connective tissue, and no donor site morbidity porous high density polyethylene (pHDPE, Medpor®), has been used in rhinoplasty since the 1980s,15 however, caused controversy over its use due to extrusion and infection problems. All the Medpor®-related problems encountered in our revisional rhinoplasty cases come from the use of pHDPE as the columellar strut. Most literatures indicate that pHDPE was used as a spreader graft, and that the complication rates were significantly lower compared to when pHDPE was used as a columellar strut.16,17,18,19,20 Based on their bivariate analysis, Winkler, et al.21 reported that the relative risk of postoperative infection from the use of pHDPE as a columellar strut was 21.24%, being approximately 5 times higher than 4.11% shown with the use of expanded polytetrafluoroethylene as the dorsal onlay. Our own experiences indicate that the surgical removal of Medpor® was extremely complicated compared to that of other alloplastic materials. This material adheres very sturdily to mucosa and perichondrium, indicating a thriving surrounding tissue and vascular ingrowth. When used as a columellar strut and a SEG, pHDPE adhered so solidly to lateral lower cartilage and septal cartilage that its removal was very difficult, and pHDPE was found to no longer function as a strong support structure.

Although not included in the alloplastic materials, irradiated homologous costal cartilage (IHCC), acellular cadaveric dermis (Alloderm®, LifeCell Corporation, NJ, USA), and injectable fillers have also been used for augmentation rhinoplasty. The clinical application of IHCC was first reported in 1961 by Dingman and Grabb22,23 and IHCC has since been applied as a substitute to autologous costal cartilage. There is no doubt that autogenous costal cartilage is the most stable material, however, because of its drawbacks including a lengthy operation time and an increased donor site morbidity, IHCC can be more attractive and recommendable. IHCC is typically required as a SEG for correcting short noses and used when not much autologous septal cartilage is available. Infection in its entirety, however, is doubtlessly the most disastrous complication to melt adjacent septal cartilage. Once infection develops, the surgical site has to be reopened immediately to remove IHCC to prevent infection from destroying adjacent septum and other normal tissues. Alloderm® has been used in various reconstructive surgery since 1995, and there are many multivariate studies on complications in soft tissue reconstruction.24,25,26 The major complaints of Alloderm® are bulkiness and depression of the tip and the dorsum. In specific cases, we recommend the use of Alloderm® to camouflage the gap at the supratip. Injectable fillers are injected for augmentation of the nose, glabella, and nasolabial fold line.27 As early complications, skin necrosis may occur when particles block subdermal artery directly, vessels are damaged due to the use of needle, or vessels are compressed by the volume of filler.28,29,30,31 In most cases, however, late or delayed complications, develop, including granuloma, nodule and chronic repetitive suppurative infection.32,33 Naturally, various wound healing methods can be applied to ameliorate the complications. There are reports that adipose-derived stem cell therapy was used to treat nasal skin necrosis, and satisfactory results of healing were obtained.34,35,36,37,38

Pursuit for an ideal nasal implant still continues. Since North39 first defined what the ideal grafting material is in 1953, many alloplastic materials have been introduced and discarded because of their serious complications. In the present meta-study, we analyzed our revisional rhinoplasty cases, based on complications and problems due to alloplastic materials used in nasal augmentation, in the hope of helping those contemporary rhinoplasty surgeons in selecting appropriate materials. Rhinoplasty is recognized as the hardest procedure in plastic surgery, therefore, a thorough understanding of nasal architecture, patient demand, and respiratory system is the utmost priority. Upon considering what and how to support in the applicable nasal structure, and what technique to use, the second priority is to find the most suitable alloplastic material according to each case.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by research funds from Dong-A University.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Deva AK, Merten S, Chang L. Silicone in nasal augmentation rhinoplasty: a decade of clinical experience. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;102:1230–1237. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199809040-00052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zeng Y, Wu W, Yu H, Yang J, Chen G. Silicone implant in augmentation rhinoplasty. Ann Plast Surg. 2002;49:495–499. doi: 10.1097/00000637-200211000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moon KM, Cho G, Sung HM, Jung MS, Tak KS, Jung SW, et al. Nasal anthropometry on facial computed tomography scans for rhinoplasty in Koreans. Arch Plast Surg. 2013;40:610–615. doi: 10.5999/aps.2013.40.5.610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tham C, Lai YL, Weng CJ, Chen YR. Silicone augmentation rhinoplasty in an Oriental population. Ann Plast Surg. 2005;54:1–5. doi: 10.1097/01.sap.0000141947.00927.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Graham BS, Thiringer JK, Barrett TL. Nasal tip ulceration from infection and extrusion of a nasal alloplastic implant. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44(2 Suppl):362–364. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.101590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pak MW, Chan ES, van Hasselt CA. Late complications of nasal augmentation using silicone implants. J Laryngol Otol. 1998;112:1074–1077. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100142495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Erlich MA, Parhiscar A. Nasal dorsal augmentation with silicone implants. Facial Plast Surg. 2003;19:325–330. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-815652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCurdy JA., Jr The Asian nose: augmentation rhinoplasty with L-shaped silicone implants. Facial Plast Surg. 2002;18:245–252. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-36492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Godin MS, Waldman SR, Johnson CM., Jr Nasal augmentation using Gore-Tex. A 10-year experience. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 1999;1:118–121. doi: 10.1001/archfaci.1.2.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conrad K, Gillman G. A 6-year experience with the use of expanded polytetrafluoroethylene in rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;101:1675–1683. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199805000-00040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jin HR, Lee JY, Yeon JY, Rhee CS. A multicenter evaluation of the safety of Gore-Tex as an implant in Asian rhinoplasty. Am J Rhinol. 2006;20:615–619. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2006.20.2948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jang TY, Choi JY, Jung DH, Park HJ, Lim SC. Histologic study of Gore-Tex removed after rhinoplasty. Laryngoscope. 2009;119:620–627. doi: 10.1002/lary.20158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang SJ, Lee JH, Tark MS. Problems of expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (Gore-Tex(R)) in augmentation rhinoplasty. J Korean Soc Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;31:28–33. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hong JP, Yoon JY, Choi JW. Are polytetrafluoroethylene (Gore-Tex) implants an alternative material for nasal dorsal augmentation in Asians? J Craniofac Surg. 2010;21:1750–1754. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3181f40426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Romo T, 3rd, Kwak ES. Nasal grafts and implants in revision rhinoplasty. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2006;14:373–387. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mendelsohn M. Straightening the crooked middle third of the nose: using porous polyethylene extended spreader grafts. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2005;7:74–80. doi: 10.1001/archfaci.7.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gürlek A, Celik M, Fariz A, Ersöz-Oztürk A, Eren AT, Tenekeci G. The use of high-density porous polyethylene as a custom-made nasal spreader graft. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2006;30:34–41. doi: 10.1007/s00266-005-0119-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Romo T, 3rd, Sclafani AP, Sabini P. Use of porous high-density polyethylene in revision rhinoplasty and in the platyrrhine nose. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1998;22:211–221. doi: 10.1007/s002669900193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim JG, Rhee SC, Cho PD, Kim DJ, Lee SH. Absorbable plate as a perpendicular strut for acute saddle nose deformities. Arch Plast Surg. 2012;39:113–117. doi: 10.5999/aps.2012.39.2.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dhong ES, Kim YJ, Suh MK. L-shaped columellar strut in East asian nasal tip plasty. Arch Plast Surg. 2013;40:616–620. doi: 10.5999/aps.2013.40.5.616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Winkler AA, Soler ZM, Leong PL, Murphy A, Wang TD, Cook TA. Complications associated with alloplastic implants in rhinoplasty. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2012;14:437–441. doi: 10.1001/archfacial.2012.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dingman RO, Grabb WC. Costal cartilage homografts preserved by irradiation. Plast Reconstr Surg Transplant Bull. 1961;28:562–567. doi: 10.1097/00006534-196111000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dingman RO, Grabb WC. [Follow-up clinic] Costal cartilage homografts presered by radiation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1972;50:516–517. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wainwright DJ. Use of an acellular allograft dermal matrix (AlloDerm) in the management of full-thickness burns. Burns. 1995;21:243–248. doi: 10.1016/0305-4179(95)93866-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davila AA, Seth AK, Wang E, Hanwright P, Bilimoria K, Fine N, et al. Human acellular dermis versus submuscular tissue expander breast reconstruction: a multivariate analysis of short-term complications. Arch Plast Surg. 2013;40:19–27. doi: 10.5999/aps.2013.40.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee JH, Park KR, Kim TG, Ha JH, Chung KJ, Kim YH, et al. A comparative study of CG CryoDerm and AlloDerm in direct-to-implant immediate breast reconstruction. Arch Plast Surg. 2013;40:374–379. doi: 10.5999/aps.2013.40.4.374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glaich AS, Cohen JL, Goldberg LH. Injection necrosis of the glabella: protocol for prevention and treatment after use of dermal fillers. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:276–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2006.32052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lazzeri D, Agostini T, Figus M, Nardi M, Pantaloni M, Lazzeri S. Blindness following cosmetic injections of the face. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129:995–1012. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182442363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oh S. Multiple embolism after injection of hyaluronic acid filler in nasal dorsum: a case report of skin necrosis, blindness, oculomotor palsy and cerebral infraction. Arch Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2012;18:138–141. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peter S, Mennel S. Retinal branch artery occlusion following injection of hyaluronic acid (Restylane) Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2006;34:363–364. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2006.01224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sung MS, Kim HG, Woo KI, Kim YD. Ocular ischemia and ischemic oculomotor nerve palsy after vascular embolization of injectable calcium hydroxylapatite filler. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;26:289–291. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e3181bd4341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Christensen L. Normal and pathologic tissue reactions to soft tissue gel fillers. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33(Suppl 2):S168–S175. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.33357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lemperle G, Gauthier-Hazan N, Wolters M, Eisemann-Klein M, Zimmermann U, Duffy DM. Foreign body granulomas after all injectable dermal fillers: part 1. Possible causes. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123:1842–1863. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31818236d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sung HM, Suh IS, Lee HB, Tak KS, Moon KM, Jung MS. Case reports of adipose-derived stem cell therapy for nasal skin necrosis after filler injection. Arch Plast Surg. 2012;39:51–54. doi: 10.5999/aps.2012.39.1.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Choi J, Minn KW, Chang H. The efficacy and safety of platelet-rich plasma and adipose-derived stem cells: an update. Arch Plast Surg. 2012;39:585–592. doi: 10.5999/aps.2012.39.6.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang JD, Choi DS, Cho YK, Kim TK, Lee JW, Choi KY, et al. Effect of amniotic fluid stem cells and amniotic fluid cells on the wound healing process in a white rat model. Arch Plast Surg. 2013;40:496–504. doi: 10.5999/aps.2013.40.5.496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee JW, Kwon OH, Kim TK, Cho YK, Choi KY, Chung HY, et al. Platelet-rich plasma: quantitative assessment of growth factor levels and comparative analysis of activated and inactivated groups. Arch Plast Surg. 2013;40:530–535. doi: 10.5999/aps.2013.40.5.530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salibian AA, Widgerow AD, Abrouk M, Evans GR. Stem cells in plastic surgery: a review of current clinical and translational applications. Arch Plast Surg. 2013;40:666–675. doi: 10.5999/aps.2013.40.6.666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.North JF. The use of preserved bovine cartilage in plastic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg (1946) 1953;11:261–274. doi: 10.1097/00006534-195304000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]