Abstract

Avian influenza virus subtype H9N2 has been circulating in the Middle East since the 1990s. For uncertain reasons, H9N2 was not detected in Egyptian farms until the end of 2010. Circulation of H9N2 viruses in Egyptian poultry in the presence of the enzootic highly pathogenic H5N1 subtype adds a huge risk factor to the Egyptian poultry industry. In this study, 22 H9N2 viruses collected from 2011 to 2013 in Egypt were isolated and sequenced. The genomic signatures and protein sequences of these isolates were analyzed. Multiple mammalian-host-associated mutations were detected that favor transmission from avian to mammalian hosts. Other mutations related to virulence were also identified. Phylogenetic data showed that Egyptian H9N2 viruses were closely related to viruses isolated from neighboring Middle Eastern countries, and their HA gene resembled those of viruses of the G1-like lineage. No reassortment was detected with H5N1 subtypes. Serological analysis of H9N2 virus revealed antigenic conservation among Egyptian isolates. Accordingly, continuous surveillance that results in genetic and antigenic characterization of H9N2 in Egypt is warranted.

Introduction

Avian influenza A H9N2 viruses were first isolated from turkeys in the United States in 1966 [26]. Since then, H9N2 viruses have been mainly detected in wild birds and turkeys. During the last two decades, H9N2 was detected in wild and domestic birds, pigs, and humans [6]. These viruses were also geographically widespread and found in North America, Eurasia, and Africa. H9N2 viruses are now enzootic in poultry of some Middle Eastern countries such as Israel and Iran [5, 17].

Poultry infected with H9N2 show no clinical illness or suffer mild respiratory signs and a drop in egg production unless the infection is complicated with other pathogens [40]. Based on previous genetic studies, two major lineages of H9N2 viruses circulated in poultry and wild birds; North American and Eurasian [21, 57]. The Eurasian lineage is subdivided into two major sub-lineages: A/quail/Hong Kong/G1/97-like (G1-like) and A/duck/Hong Kong/Y280/97-like (Y280-like) [61]. Based on evolutionary dynamics of complete genome sequences of H9N2 viruses circulating in nine Middle Eastern and Central-Asian countries from 1998 to 2010, H9N2 viruses were further divided into four distinct and co-circulating groups (A, B, C, and D). Each of these groups underwent widespread inter- and intra-subtype re-assortments, leading to the generation of viruses with unknown biological properties [15]. Groups A and B have circulated extensively in Middle Eastern countries and have been identified from 1999 to the present day. Previous H9N2 evolution studies suggested that the major source for the Middle Eastern H9N2 viruses is Eastern Asia but that evolution within countries and regions played an important role in shaping viral genetic diversity [5, 15]. H9N2 viruses are capable of infecting humans and have played a role in the genetic evolution of other avian influenza viruses that infect humans.

Previous sero-epidemiological studies showed that the prevalence of human H9N2 infection is higher than the number of confirmed cases reported [6, 20, 43, 50]. Throughout the viral genomes of H9N2 viruses, several apparent mutations associated with the adaptation of viruses to mammalian hosts were noted [46]. Importantly, a leucine substitution at amino acid position 226 in the HA receptor-binding site was found to be important for the transmission of H9N2 viruses in mammals [54]. Recent studies have shown that H9N2 viruses may have contributed to the genetic and geographic diversity of H5N1 viruses [19, 34]. H9N2 donated the internal genes to the currently circulating H5N1 and H7N9 viruses [18, 35]. Inter-subtype reassortment between co-circulating H9N2 virus and highly pathogenic H5N1 or H7N3 virus has been detected in China and Pakistan [19, 28]. H9N2 was recently detected in Egypt, a country where H5N1 viruses are enzootic [14, 38]. Co-circulation of H9N2 with H5N1 in susceptible host populations can increase the likelihood of generating novel reassortant viruses with public health implications. Previous studies of a few Egyptian H9N2 viruses showed that these viruses were G1-like and were closely related to H9N2 viruses from other Middle Eastern countries, especially Israel [2, 38]. In this study, the genetic and antigenic characteristics of H9N2 viruses that circulated in Egypt between 2011 and 2013 were examined. The evolutionary dynamics of these viruses were also studied.

Materials and methods

Virus isolation and propagation

Cloacal and oropharyngeal swabs were collected as part of an ongoing long-term surveillance of avian influenza in Egyptian poultry [33]. Viral RNA was extracted from 140 μL of each sample collected using a QIAamp viral RNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. To detect influenza A virus, extracted RNA was subjected to RT-PCR to amplify 244 bp of the M segment of influenza A viruses according to a WHO protocol [59]. Samples that were positive for the M segment were then subjected to additional RT-PCR to determine the HA and NA subtypes [58]. One hundred microliters of each sample that was positive for influenza A virus by RT-PCR was used to inoculate 10-day-old specific-pathogen-free embryonated chicken eggs (SPF Eggs Production Farm, Egypt), which were incubated for 48 h at 37 °C and then chilled at 4 °C for 4 h before harvesting. The allantoic fluid was harvested, clarified, tested for hemagglutination, and then stored at −80 °C until use. H9N2 isolates (n=22) collected from poultry flocks between December 2011 and April 2013 were included in this study (Table S1).

Amplification of the full genome and sequencing

Viral RNA was extracted from harvested allantoic fluid using a QIAamp Viral Mini Kit. The first-strand cDNA was synthesized using Superscript III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and Uni-12 primer (5′AGCRAAAGCAGG3′) as per the manufacturer’s protocol. Using a PhusionMaster Mix kit (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA), the full genomes of the isolates were amplified using universal primers [24]. Briefly, using gene-specific primers, 2 μL of each RT reaction was subjected to PCR with an initial denaturation step (98°C, 30 s), 40 cycles of 98 °C for 10 s, 57 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 2 min, and a final elongation step (72 °C, 10 min). Amplicons of the appropriate sizes were subsequently gel purified using a QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (QIAGEN). The purified PCR products were used directly for sequencing reactions using a BigDyeR Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) according to manufacturer’s instructions and were further amplified for 26 cycles at 95 °C for 30 s, 50 °C for 15 s, and 60 °C for 4 min. The reaction product was purified by exclusion chromatography in CentriSep columns (Princeton Separations, Adelphia, NJ). The recovered materials were sequenced using a 96-capillary 3730xl DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). Sequences were assembled using SeqMan DNA Lasergene 7 software (DNASTAR, Madison, WI, USA). The GenBank accession numbers for the submitted sequences are listed in Table S1.

Sequence analysis and phylogenetic tree construction

MegAlign (DNASTAR) and BioEdit 7.0 were used for multiple sequence alignment [23]. Percent identity matrices comparing the genes under study to each other were obtained. MEGA 5.0 was used for phylogenetic tree construction of all eight gene segments by applying the neighbor-joining method with Kimura’s two-parameter distance model and 1000 bootstrap replicates [48]. The trees included all Egyptian H9N2 virus sequences available in the GenBank database, closely related H9N2 viruses from other Middle Eastern countries, representative viruses from the groups A-D [15], major ancestral H9N2 strains, and other influenza virus subtypes with closely related H9N2 genes, as shown by a BLAST search. The BioEdit program version 7.0 was used for genomic signature analysis.

Hemagglutination inhibition assay

A hemagglutination inhibition (HI) assay using monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies with 0.5% chicken RBCs was used for antigenic characterization of 17 H9N2 isolates [58]. A panel of anti-H9 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) prepared against different antigenic epitopes of A/chicken/Hong Kong/G9/97(G9-25) (G9), A/quail/Hong Kong/G1/97(G1-26), A/Hong Kong/1073/99 (1073-9), and A/duck/Hong Kong/Y280/97 (18G4.B11.F9) was used. Polyclonal antibodies against three H9N2 viruses were also used (rat anti-A/chicken/Egypt/S4456B/2011, ferret anti-A/quail/D1556/UAE/2011, and chicken anti-A/quail/272/Lebanon/2010). The HI assay was performed at a starting dilution of 1:100 for the mAbs and 1:10 for polyclonal antibodies. HI data were then used to construct antigenic cartography using the integrative matrix completion multi-dimensional scaling (MC-MDS) method as described previously [7, 8].

Measurement of selection pressure

The number of base and amino acid substitutions per site was analyzed using the Kimura 2-parameter model and the Poisson correction model, respectively, by MEGA 5.0. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. To determine the selection pressure for each gene segment, the 22 whole genome sequences were analyzed by estimating the ratio of non-synonymous (dN) to synonymous (dS) substitutions (ω =dN/dS) across the lineages on a codon-by-codon basis. Selective pressure was defined as follows: ω=1 indicates neutral evolution, ω<1 indicates negative or purifying selective pressure, and ω>1 indicates positive selection. The mean values of ω were calculated by the single-likelihood ancestor counting method (SLAC) using the Data Monkey website (http://www.data-monkey.org) [13].

Results

During our active surveillance of domestic poultry in Egypt, 10% of >11,000 samples were positive for influenza A viruses. Subtyping of positive samples indicated the circulation of H5N1 and H9N2 viruses. These subtypes also co-infected the same host in 5–50% of the positive samples, depending on the month of detection [16]. The 22 Egyptian H9N2 viruses were isolated from sick and healthy broiler chickens in Egypt between December 2011 and April 2013. The details of isolation area, health status of the host, date of isolation, and GenBank accession numbers of these isolates are provided in Table S1.

Molecular characterization and phylogenetic analysis of the eight viral segments

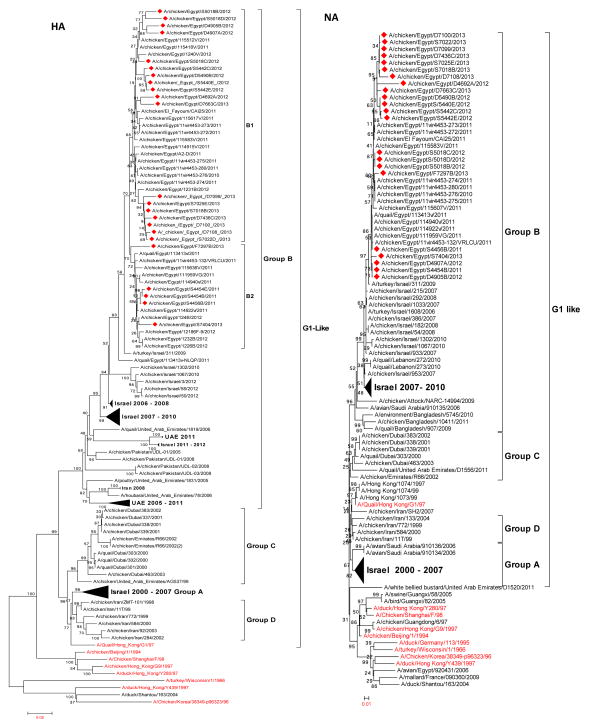

PB2

The nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequence similarities among Egyptian strains ranged from 96.5 to 99.9% and 95.9 to 99.7%, respectively. The PB2 genes of Egyptian isolates showed higher similarity to those of A/duck/Altai/1285/1991(H5N3) and A/duck/Mongolia/47/2001(H7N1) (92%) than to those of other ancestral H9N2 viruses such as G1 (85%) and Y280 (82%). All Egyptian isolates clustered in group A with isolates from Israel, Saudi Arabia, and Jordan (Fig. 1). Egyptian viruses clustered in two groups: viruses in one group had amino acids V and H at positions 176 and 357, while viruses of the second group had I and Q at these positions.

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic trees of the nucleotide sequences of PB2, PB1 and PA of H9N2 viruses. Isolates sequenced specifically for this study are indicated by a red rhomboid. Non-H9N2 subtypes are indicated in blue. The percentage of replicate trees in which the associated sequences clustered together in the bootstrap test (1000 replicates) is shown at the dendrogram nodes. The phylogenetic analysis was performed using MEGA version 5.2.

Except for 318R, which was detected in 14 Egyptian viruses, all other PB2 residues that are associated with host specificity were avian-like (Table 1). Substitution of E to K and D to N at position 627 and 701, respectively, was associated with virulence and virus transmission in mammals [55, 63]. These were not found in Egyptian strains that displayed V and D at positions 627 and 701, respectively, as shown in Table 2. The I504V substitution is associated with enhanced activity of the polymerase complex [44], and this substitution was observed in all isolates. All Egyptian strains had the mutations 355M and 453T, which were not previously described (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Analysis of genetic determinants of host range in the PB2,PB1-F2, PB1, PA, NP, M1, M2, NS1, and NS2 proteins in H9N2 viruses isolated from poultry in Egypt. The avian- or mammalian-preference markers are shown and compared to the distribution of these markers in Egyptian viruses and A/quail/Hong Kong/G1/97

| Protein | Site | Avian preference | Mammalian preference | Egyptian H9N2 | A/quail/Hong Kong/G1/97 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PB2 | 44 | A | S | A | A |

| 64 | M | T | I(3), M(19) | M | |

| 81 | T | M | T | T | |

| 199 | A | S | A | A | |

| 318 | K | R | K(7),S(1),R(14) | K | |

| 627 | E | K | V | E | |

| 661 | A | T | A | T | |

| 701 | D | N | D | D | |

| 702 | K | R | K | K | |

| PB1-f2 | 68 | T | I | T(21), I(1) | T |

| 73 | K | R | K | K | |

| 76 | V | A | V | V | |

| 79 | R | Q | R | R | |

| 82 | L | S | S | L | |

| PB1 | 13 | L | P | P | P |

| 336 | V | I | V | V | |

| 375 | N | S | N | N | |

| PA | 28 | P | L | P | P |

| 55 | D | N | D | D | |

| 57 | R | Q | R | R | |

| 100 | V | A | V | V | |

| 133 | E | G | E | E | |

| 225 | S | C | S | S | |

| 241 | C | Y | C | C | |

| 268 | L | I | L | L | |

| 312 | K | R | K | K | |

| 356 | K | R | K | K | |

| 382 | E | D | E | E | |

| 400 | Q/T/S | L | S | L | |

| 404 | A | S | A | A | |

| 409 | S | N | S | S | |

| 552 | T | S | T | T | |

| 556 | Q | R | Q | Q | |

| 615 | K | L | K | R | |

| NP | 31 | R | K | R | R |

| 33 | V | I | V(20), I(2) | V | |

| 34 | D | N | D | G | |

| 61 | I | L | I | I | |

| 100 | R | V | R | R | |

| 109 | I | V | I (21),V(1) | I | |

| 127 | E | D | E | E | |

| 136 | L | M | L | M | |

| 214 | R | K | K(21), N(1) | R | |

| 283 | L | P | L | L | |

| 293 | R | K | R | R | |

| 305 | R | K | R | R | |

| 313 | F | Y | F | F | |

| 357 | Q | K | Q | Q | |

| 372 | E | D | E | E | |

| 375 | D | G/E | D | D | |

| 398 | K | Q | Q | Q | |

| 422 | R | K | R | R | |

| 442 | T | A | T | T | |

| 455 | D | E | D(21), E(1) | D | |

| M1 | 15 | V | I | I | I |

| 115 | V | I | V | R | |

| 121 | T | A | T | T | |

| 137 | T | A | T | T | |

| M2 | 11 | T | I | T | T |

| 16 | E | G/D | G | G | |

| 20 | S | N | S | S | |

| 28 | I | I/V | V | V | |

| 57 | Y | H | Y | Y | |

| 55 | L | F | F | F | |

| 86 | V | A | V(21), A(1) | V | |

| NS1 | 227 | E | K/R | K | E |

Table 2.

Virulence determinants in the PB2, PB1-F2, PB1, PA, M2, NS1, and NS2 proteins in H9N2 viruses isolated from poultry in Egypt. The virulence markers are shown and compared to the distribution of these markers in Egyptian viruses and A/quail/Hong Kong/G1/97

| Protein | Site | Virulent | Avirulent | Egyptian H9N2 | A/quail/Hong Kong/G1/97 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PB2 | 627 | K | E | V | E |

| 147 | L | M | I | M | |

| 250 | G | V | V | V | |

| 504 | V | I | V | V | |

| 701 | N | D | D | D | |

| PB1 | 317 | I | M/V | I(19),M(3) | I |

| PB1-f2 | 66 | S | N | S | N |

| PA | 127 | V | I | V | V |

| 672 | L | F | L | L | |

| 550 | L | I | L | L | |

| M2 | 64 | S/A/F | P | S | S |

| 69 | P | L | P | P | |

| NS1 | 42 | S | A/P | S | S |

| 92 | E | D | D | E | |

| 103 | L | F | F | L | |

| 106 | I | M | M | I | |

| 189 | N | D/G | D | D | |

| NS2 | 31 | I | M | I | M |

| 56 | Y | H/L | H | H |

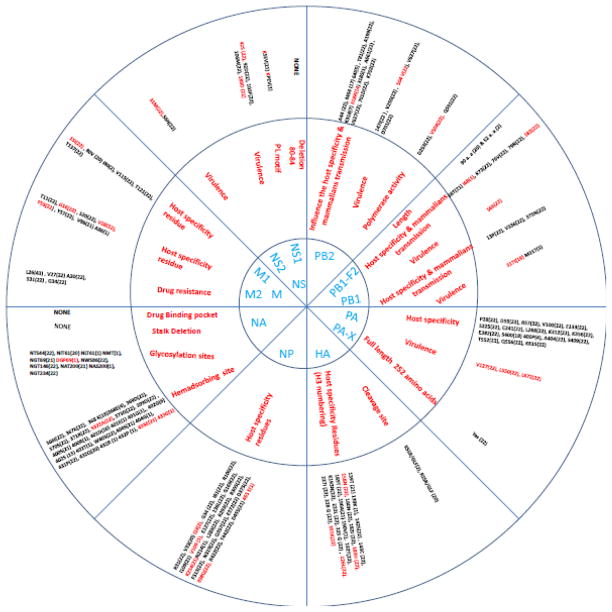

Fig. 2.

Virulence and host specificity determinants in Egyptian H9N2 viruses isolated from Egypt in the period 2011–2013. The numbers in parentheses indicate the number of H9N2 viruses that contain the specific residues. Red indicates that the residue is critical for virulence, host range determinants, antiviral resistance, or enzyme activity. Blue indicates the 12 viral proteins that were analyzed.

PB1

The percentage of similarity among Egyptian nucleotide sequences ranged from 96.3 to 100%. PB1-F2 is encoded by an open reading frame overlapping PB1 and is an important determinant of influenza virus virulence [10]. Egyptian isolates showed two variants of this protein that differed in length: 52 residues (2 isolates; A/chicken/Egypt/D7436C/2013 and A/chicken/Egypt/D7663C/2013) or 90 residues (20 isolates) (Fig. 2). Previous studies showed that the N66S mutation in the PB1-F2 protein is important for increasing viral pathogenicity [11]. This substitution was present in all of the isolates (Table 2). The mammalian-host-associated substitution L82S was also identified in all of the isolates. In a single H9N2 isolate (A/chicken/Egypt/F7297B/2013), the mammalian-host-associated substitution T68I was identified (Table 1).

Egyptian strains differed from the G1 strain in the PB1 protein by several mutations, including P64L, V114I, S152L, E178K, T182I, V200I, K211G, T213N, H253Y, A257T, V302T, R386K, E390M, E398D, G610C, and S633T. Based on site 317, the isolates were classified into two groups: 86.3% had I (virulent form) and 13.6% had M (avirulent form) (Table 2).

Phylogenetic analysis showed that Egyptian PB1 genes are related to A/Pekin robin/California/30412/1994(H7N1) rather than to an H9N2 progenitor. Egyptian isolates were closely related to Israeli H9N2 isolates and belonged to group A (Fig. 1). The clustering among the Egyptian viruses was not related to specific amino acids.

PA

The PA genes of the Egyptian isolates showed nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequence similarities that ranged from 97.4 to 100% and 97.8 to100%, respectively. The deduced PA amino acid sequence did not have any mammalian-host-associated substitutions at residues previously identified as important for changing host range from avian to human (Table 1). A previously undescribed mutation (S186) was found in all Egyptian isolates. Amino acid substitutions V127, L672, and L550, which are associated with virulence, were observed in all Egyptian H9N2 isolates (Table 2) [9, 44]. Phylogenetic analysis showed that the Egyptian isolates belonged to the Y439 lineage and clustered with isolates from Israel, Saudi Arabia, and Jordan in group A (Fig. 1). Analysis of the PA gene showed that all Egyptian isolates possessed previously recognized ribosomal frameshifting responsible for viral protein PA-X (Fig. 2). Two viruses, A/chicken/Egypt/S4454E/2011 and A/chicken/Egypt/S4456B/2011, branched together and had V13, A20, I30, and V308. A cluster of 2013 viruses had V54, I122, and T337.

HA

Analysis of the HA genes showed that the nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequence similarities among Egyptian strains ranged from 95.7 to 99.6% and 95.5 to 99.6%, respectively. The tested strains shared nucleotide and deduced amino acid homologies that ranged from 87 to 89.5% and 91.2 to 89.3%, respectively, with (G1) and 84.3 to 86% and 88.5 to 90%, respectively, with (Y280).

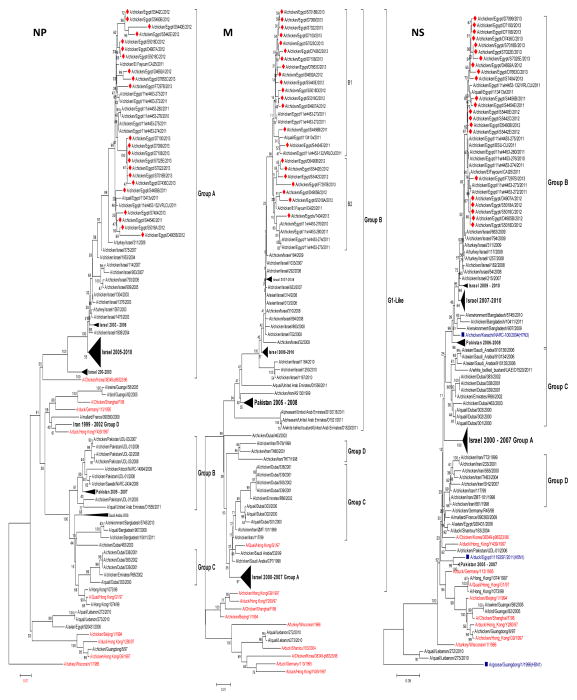

Based on phylogenetic analysis, the Egyptian H9N2 viruses cluster tightly with those of Israeli and Lebanese origin in group B and are related to G1-like viruses. Egyptian viruses can be divided into two groups (B1 and B2), which evolved and co-circulated between 2011 and 2013 (Fig. 3). Viruses in group B1 shared amino acids A357 and N428 (H9 numbering), and group B2 viruses had S357 and D428 (H9 numbering).

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic trees of the nucleotide sequences of HA and NA of H9N2 viruses. Isolates sequenced specifically for this study are indicated by a red rhomboid.

Changes in the HA are critical for determining host range and pathogenicity. The key molecular determinants of pathogenicity and viral transmission in the HA molecule are the HA1/HA2 cleavage site, the receptor binding site (RBS), and the presence or absence of glycosylation sites near the RBS [4]. All of the Egyptian isolates lacked a multibasic cleavage site characteristic of highly pathogenic influenza viruses, suggesting that all of the isolates were of low pathogenicity. The HA1/HA2 cleavage site possessed two cleavage motifs (Table 3). Two isolates from 2011 exhibited the cleavage site motif KSSR/GLF, and the remaining isolates had the RSSR/GLF motif, which is the signature of low pathogenicity H9N2 viruses isolated from the Middle East and Asia which are well adapted to the chicken host [1, 17, 49].

Table 3.

Comparison of amino acid sequences of the HA of H9N2 viruses isolated from poultry in Egypt between 2011 and 2013 with ancestor H9N2 viruses and isolates from Lebanon, UAE and Israel (H9 numbering)

| H9N2 virus | RBS | Cleavage site | Glycosylation (H9 numbering) |

Amino acid residues at receptor pocket (H9 numbering) |

Antigenic site (H9 numbering) |

|||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H9N2 numbering | 166 | 191 | 197 | 198 | 232 | 234 | 235 | 236 | 399 | 29 | 105 | 141 | 206 | 218 | 298 | 305 | 492 | Left edge2 | Binding site1 | Right edge3 | Site I4 | Site II5 | Overlapping site6 |

|

| H3Residues at HA RBS (H3 numbering)* |

158 | 183 | 189 | 190 | 224 | 226 | 227 | 228 | 391 | |||||||||||||||

| A/quail/Hong Kong/G1/97 | S | H | T | E | N | L | Q | G | K | RSSRGLF | NST | NGT | NVT | NDT | NRT | NST | NIS | NGT | NDLQGR | GWTHELY | GISRA | TSP | FNL | TN |

| A/chicken/Hong Kong/G9/97 | N | N | . | A | . | . | . | . | . | . . . . . . . | . . . | . .M | . . S | T . . | .. . | . T . | . V . | . . . | . G . . . . | . . . NA . . | . T. K . | SN . | . . . | . T |

| A/quail/Lebanon/272/2010 | N | . | . | V | . | . | I | . | . | . . . . . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | T . . | D . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | . G . I . . | . . . . V. . | . T .KS | . N . | . . . | . T |

| A/turkey/Israel/1567/2004 | . | . | . | A | . | . | . | . | . | . . . . . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | T . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | . G . . . . | . . . . A. . | . T. K . | . . . | . . . | . T |

| A/turkey/Israel/311/2009 | N | . | . | A | . | . | I | . | . | . . . . . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | T . . | D . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | . G . I . . | . . . . A. . | . T. KS | . N . | . . . | . T |

| A/Hong Kong/1073/99 | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . . . . . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | . G . . . . | . . . . . . . | . T. . . | . N . | . . . | . . |

| A/duck/Hong Kong/Y280/97 | N | N | . | T | . | . | . | . | . | . . . . . . . | . . . | . . L | . . S | T . . | . . . | . T . | . V . | . . . | . G . . . . | . . . NT. . | . T .K . | SN . | . . . | . T |

| A/quail/UAE/D1556/2011 | R | . | . | I | G | Q | F | G | K | . . R . . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | D . . | . . . | . V . | . . . | . GQF. . | . . . . I. . | . T. SS | . R . | S . | |

| A/chicken/Egypt/S4454E/2011 | N | . | . | A | . | . | I | . | . | K. . . . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | I . . | D . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | . G . I . . | . . . . A. . | . T .KS | . N . | . . . | . I |

| A/chicken/Egypt/S4456B/2011 | N | . | . | A | . | . | I | . | . | K. . . . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | I . . | D . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | . G . I . . | . . . . A. . | . T .KS | . N . | . . . | . I |

| A/chicken/Egypt/D4692A/2012 | N | . | . | A | . | . | I | . | . | . . . . . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | T . . | D . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | . G . I . . | . . . . A. . | . T .KS | . N . | . . . | . T |

| A/chicken/Egypt/D4905B/2012 | N | . | . | A | . | . | I | . | . | . . . . . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | T . . | D . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | . G . I . . | . . . . A. . | . T .KS | . N . | . . . | . T |

| A/chicken/Egypt/D4907A/2012 | N | . | . | A | . | . | I | . | . | . . . . . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | T . . | D . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | . G . I . . | . . . . A. . | . T .KS | . N . | . . . | . T |

| A/chicken/Egypt/S5018A/2012 | N | . | . | A | . | . | I | . | . | . . . . . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | T . . | D . . | . . S | . . . | . . . | . G . I . . | . . . . A. . | . T .KS | . N . | . . . | . T |

| A/chicken/Egypt/S5018C/2012 | N | . | . | A | . | . | I | . | . | . . . . . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | T . . | D . . | . . S | . . . | . . . | . G . I . . | . . . . A. . | . T .KS | . N . | . . . | . T |

| A/chicken/Egypt/S5018D/2012 | N | . | . | A | . | . | I | . | . | . . . . . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | T . . | D . . | . . S | . . . | . . . | . G . I . . | . . . . A. . | . T .KS | . N . | . . . | . T |

| A/chicken/Egypt/S5440E/2012 | N | . | . | A | . | . | I | . | . | . . . . . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | T . . | D . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | . G . I . . | . . . . A. . | . T .KS | . N . | . . . | . T |

| A/chicken/Egypt/S5442C/2012 | N | . | . | A | . | . | I | . | . | . . . . . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | T . . | D . . | . . . | . . . | . . A | . G . I . . | . . . . A. . | . T .KS | . N . | . . . | . T |

| A/chicken/Egypt/S5442E/2012 | N | . | . | A | . | . | I | . | . | . . . . . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | T . . | D . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | . G . I . . | . . . . A. . | . T .KS | . N . | . . . | . T |

| A/chicken/Egypt/D5490B/2012 | N | . | . | A | . | . | I | . | . | . . . . . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | T . . | D . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | . G . I . . | . . . . A. . | . T .KS | . N . | . . . | . T |

| A/chicken/Egypt/S7018B/2013 | N | . | . | A | . | . | I | . | . | . . . . . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | T . . | D . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | . G . I . . | . . . . A. . | . T .KS | . N . | . . . | . T |

| A/chicken/Egypt/S7022D/2013 | N | . | . | A | . | . | I | . | . | . . . . . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | T . . | D . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | . G . I . . | . . . . A. . | . T .KS | . N . | . . . | . T |

| A/chicken/Egypt/S7025E/2013 | N | . | . | A | . | . | I | . | . | . . . . . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | T . . | D . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | . G . I . . | . . . . A. . | . T .KS | . N . | . . . | . T |

| A/chicken/Egypt/D7099/2013 | N | . | . | A | . | . | I | . | . | . . . . . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | T . . | D . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | . G . I . . | . . . . A. . | . T .KS | . N . | . . . | . T |

| A/chicken/Egypt/D7100/2013 | N | . | . | A | . | . | I | . | . | . . . . . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | T . . | D . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | . G . I . . | . . . . A. . | . T .KS | . N . | . . . | . T |

| A/chicken/Egypt/D7108E/2013 | N | . | . | A | . | . | I | . | . | . . . . . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | T . . | D . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | . G . I . . | . . . . A. . | . T .KS | . N . | . . . | . T |

| A/chicken/Egypt/F7297B/2013 | N | . | . | V | . | . | I | . | . | . . . . . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | T . . | D . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | . G . I . . | . . . . V. . | . K .KS | . N . | . . . | . T |

| A/chicken/Egypt/S7404/2013 | N | . | . | A | . | . | I | . | . | . . . . . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | T . . | D . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | . G . I . . | . . . . A. . | . T .KS | . N . | . . . | . T |

| A/chicken/Egypt/D7436C/2013 | N | . | . | A | . | . | I | . | . | . . . . . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | T . . | D . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | . G . I . . | . . . . A. . | . T .KS | . N . | . . . | . T |

| A/chicken/Egypt/D7663C/2013 | N | . | . | A | . | . | I | . | . | . . . . . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | T . . | D . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | . G . I . . | . . . . A. . | . T .KS | . N . | . . . | . T |

Amino acid residues at position 106, 161, 163, 191, 198, 202, and 203, respectively.

Amino acid residues at position 232–237

Amino acid residues at position 146–150.

Amino acid residues at position 143, 166, and 170, respectively

Amino acid residues at position 155, 201, and 234, respectively

Amino acid residues at position 197, and 206, respectively

H3 numbering according to ref. 22

The RBS is critical for host cellular receptor specificity and influences the generation of human viruses from avian precursors. Amino acid substitutions at positions located within the RBS (Q183/191H, T189/197A, A190/198E, and Q226/234L [H3/H9 numbering]) are essential for respiratory droplet transmission of avian H9N2 viruses in ferrets [54]. Within the RBS, all Egyptian isolates had H183/191 and L226/234 (H3/H9 numbering), which are associated with preferential binding to a cellular receptor present in different respiratory epithelial cells in humans. Avian-receptor-specific substitutions were identified at 189/197 T and 190/198A (H3/H9 numbering).

Glycosylation sites of HA play an important role in host-cell receptors, shielding antigenic epitopes, and virulence of influenza viruses [32, 52, 56]. Potential glycosylation sites with the N-X-T/S-X sequence, where X is any amino acid other than proline, were identified. Five glycosylation sites (29, 105,141, 298, and 305) were found in the HAs of all Egyptian isolates. The glycosylation site NGT at position 492 was present in all Egyptian isolates except A/chicken/Egypt/S5442C/2012. On the other hand, three isolates, A/chicken/Egypt/D4905B/2012, A/chicken/Egypt/D4907A/2012, and A/chicken/Egypt/D7099/2013, lost the glycosylation site at position 551. Glycosylation sites 206 and 218 were lost from all Egyptian isolates when compared with G1-like viruses (Table 3).

NP

The amino acid sequence identity of the NP of the 22 Egyptian isolates was 95 to 100%. Phylogenetic analysis showed that all of these genes are closely related to those of Korean-like viruses and cluster with recent Israeli viruses in group A. Clustering within the Egyptian viruses was not related to specific amino acids (Fig. 4). Sequence analysis showed mammalian-host-associated markers at V33I (two isolates), I109V (one isolate), R214K (21 isolates), K398Q (22 isolates), and D455E (one isolate) (Table 1).

Fig. 4.

Phylogenetic tree of the nucleotide sequences of NP, M, and NS of H9N2 viruses. Isolates sequenced specifically for this study are indicated by a red rhomboid. Non-H9N2 subtypes are indicated in blue.

NA

The homology between the nucleotide sequences of the NA segment ranged from 94.7 to 99.9%. The enzyme active site, stalk length, hemadsorbing site, and number of glycosylation sites have a potential role in neuraminidase activity. Longer stalk length of viral NA enhances replication of influenza virus, as concluded previously [37]. Analysis of stalk length revealed that no stalk deletions at sites 38–39 were present – a characteristic of G1-like viruses. The specific stalk deletion at amino acids 46–50, which is important for poultry adaptation of the virus [28], was also not found. Sequence analysis of binding-pocket residues involved in interactions with antiviral drugs revealed that no mutations were present. The sialic-acid-binding pocket of the hemadsorbing site (366–373, 399–404, and 431–433) revealed mutations in several forms, as shown in Fig. 2. The NA genes of the Egyptian viruses contained seven glycosylation sites, at positions 44, 61, 69, 86, 146, 200, and 234 (Fig. 2). The glycosylation site at 402, which was described previously as a characteristic of H9N2 viruses, was not found in the Egyptian isolates [51].

A phylogenetic tree showed that Egyptian viruses clustered together in group B within the G1 sublineage and that the clustering among the Egyptian viruses was not related to specific amino acids (Fig. 3). Egyptian isolates showed a close relationship to isolates from Israel and Lebanon.

M

The amino acid sequences of the Egyptian M1 (252 amino acid residues) proteins showed 98.8 to 100% similarity. Similarly, the M2 (97 amino acid residues) proteins had 95.9 to 100% homology. Alignment of the M2 protein showed the conserved L10 residue, which defines the G1 lineage. None of the Egyptian isolates contained substitutions at amino acid positions 26, 27, 30, 31 or 34, suggesting the absence of resistance to the adamantane class of antiviral drugs. Mammalian transmission markers (G16, V28, and F55 of M2; and I15 of M1) were found in all isolates, and marker A86 was found only in A/chicken/Egypt/S7404/2013 (Table 1). All Egyptian isolates possessed the virulent form of residues at 64 and 69 in the M2 gene (Table 2).

Phylogenetic analysis showed that all of these genes are closely related to those of G1-like viruses and cluster with recent Israeli viruses in group B. Egyptian viruses evolved into two subgroups, B1 and B2, but clustering within the subgroups was not related to specific amino acids (Fig. 4).

NS

The nucleotide sequence homology of the NS segments of the Egyptian isolates ranged between 97.1 and 100%. The amino acid sequences of the NS1 (230 amino acid residues) and NS2 (121 amino acid residues) proteins showed 93.9 to 100% and 94.2 to 100% identity, respectively. All isolates had the PDZ (X-S/T-X-V) KSEV C-terminal motif, except one isolate, A/chicken/Egypt/F7297B/2013, which possessed a KPEV sequence. The NS1 protein of all isolates harbored the mammalian-specific E227K substitution (Fig. 2). Also, all isolates had S and N instead of P and D at position 42 and 189, respectively; this is associated with increased virulence [30]. In addition, Egyptian strains exhibited no substitutions at position 92, which is related to virulence of H5N1 and cytokine resistance when changed to E [45]. F103L and M106I amino acid substitutions, which are known to be genetic determinants of pathogenicity and virulence in both human and avian hosts, were not observed in NS1 [12]. Phylogenetic analysis of NS genes showed that the Egyptian H9N2 isolates are highly homogenous and cluster together with Israeli isolates in group B, which are closely related to an H7N3 virus isolated from Pakistan in 2004 (Fig. 4). A cluster of Egyptian 2012 viruses were characterized by L28 and N171 in the NS1 gene.

Selection pressure

In order to determine the evolution rate in Egyptian H9N2 viruses, we conducted selection pressure analysis. The analysis revealed that H9N2 genes in Egypt were under selective pressure, with an ω value ranging from 0.109293 (for the M1 gene) to 2.0889 (for the PB1-F2 gene). PB1-F2 and M2 genes seem to be under positive natural selection. The nucleotide sequence diversity of each gene segment was calculated on the basis of Kimura distances, ranging from 0.3% (for M2) to 2.4% (for HA). Amino acid divergence in each gene segment ranged from 0.3% (for M1) to 4.8% (for NA) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Selection pressure analysis for Egyptian H9N2 isolates

| Viral gene | Kimura mean distance (%) (nt) | Distance (%)(aa) | ω (dN/dS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PB2 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 0.284509 |

| PB1 | 1.7 | 2 | 0.437339 |

| PB1-F2 | 1.5 | 2.2 | 2.0889 |

| PA | 1.5 | 1 | 0.126966 |

| PA-X | 1.6 | 1.4 | 0.203 |

| HA | 2.4 | 2.7 | 0.420623 |

| NP | 1.8 | 1.5 | 0.257767 |

| NA | 1.3 | 4.8 | 0.483129 |

| M1 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.109293 |

| M2 | 0.3 | 1.1 | 1.07102 |

| NS1 | 1.5 | 1.8 | 0.391888 |

| NS2 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 0.39648 |

Antigenic analysis

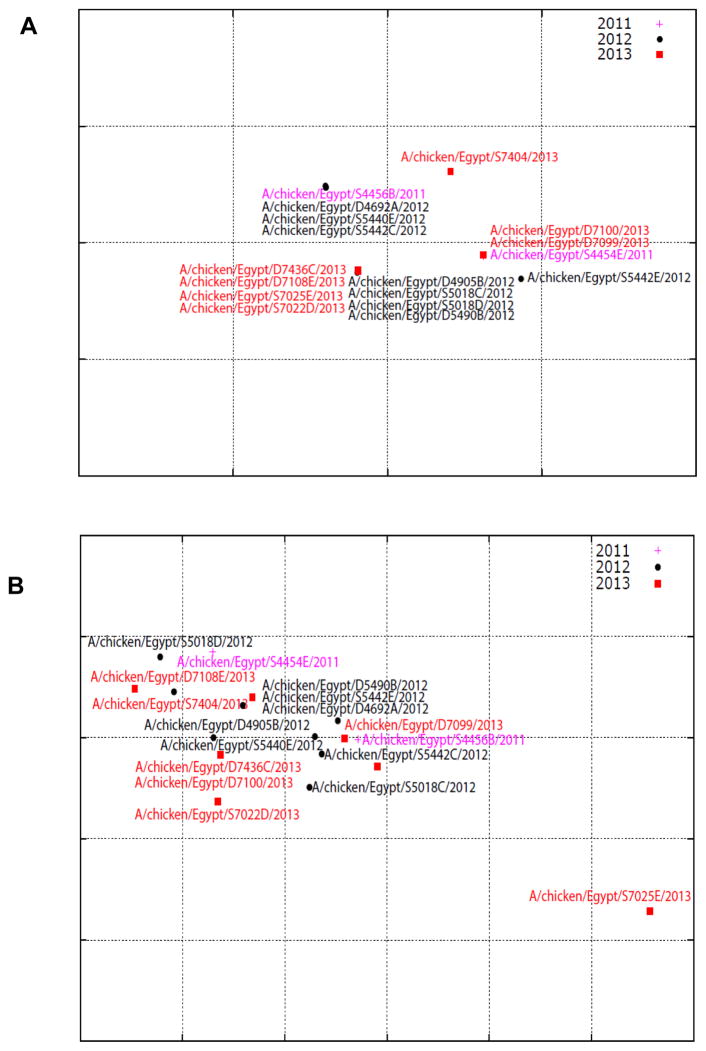

HI titers against polyclonal antibodies showed that all Egyptian isolates had the same reactivity pattern. All reacted well with antisera against the Egyptian virus and did not react with antiserum against the A/quail/UAE/D1556/2011(H9N2) virus. Moderate reactivity to antiserum against the A/quail/Lebanon/272/2010 (H9N2) virus was observed (Table 5). The cartography of the HI results showed that the Egyptian H9N2 viruses fell into one cluster (Fig. 5A).

Table 5.

Hemagglutination inhibition assay titres of monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies against different Egyptian H9N2 isolates

| Virus | Monoclonal antibodies | Polyclonal antibodies | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | 1073 | G9 | Y280 | Ferret | Rat | Chicken | |

| (G1-26) | (1073-9) | (G9-25) | 18G4 | A/quail/UAE/D1556/2011 | A/CH/EG/S4456B/11 | A/quail/Lebanon/272/2010 | |

| A/chicken/Egypt/S4454E/2011 | 51200 | 6400 | 204800 | 800 | <10 | 4096 | 128 |

| A/chicken/Egypt/S4456B/2011 | 25600 | 400 | 51200 | 800 | <10 | 2048 | 64 |

| A/chicken/Egypt/D4692A/2012 | 25600 | 800 | 204800 | 200 | <10 | 2048 | 64 |

| A/chicken/Egypt/D4905B/2012 | 12800 | 6400 | 204800 | 200 | <10 | 4096 | 64 |

| A/chicken/Egypt/S5018C/2012 | 12800 | 800 | 25600 | 800 | <10 | 4096 | 64 |

| A/chicken/Egypt/S5018D/2012 | 25600 | 12800 | 204800 | 1600 | <10 | 4096 | 64 |

| A/chicken/Egypt/S5440E/2012 | 12800 | 800 | 102400 | 800 | <10 | 2048 | 64 |

| A/chicken/Egypt/S5442C/2012 | 12800 | 800 | 102400 | 400 | <10 | 2048 | 64 |

| A/chicken/Egypt/S5442E/2012 | 25600 | 3200 | 102400 | 800 | <10 | 4096 | 256 |

| A/chicken/Egypt/D5490B/2012 | 25600 | 12800 | 204800 | 400 | <10 | 4096 | 64 |

| A/chicken/Egypt/S7022D/2013 | 26500 | 12800 | 204800 | <100 | <10 | 4096 | 64 |

| A/chicken/Egypt/S7025E/2013 | 12800 | <100 | 51200 | <100 | <10 | 4096 | 64 |

| A/chicken/Egypt/D7099/2013 | 25600 | 800 | 204800 | 100 | <10 | 4096 | 128 |

| A/chicken/Egypt/D7100/2013 | 12800 | 400 | 204800 | 100 | <10 | 4096 | 128 |

| A/chicken/Egypt/D7108E/2013 | 25600 | 25600 | 204800 | 400 | <10 | 4096 | 64 |

| A/chicken/Egypt/S7404/2013 | 25600 | 3200 | 204800 | 400 | <10 | 2048 | 128 |

| A/chicken/Egypt/D7436C/2013 | 12800 | 6400 | 204800 | 100 | <10 | 4096 | 64 |

| A/turkey/Israel/1567/2004 | 51200 | 3200 | 51200 | 6400 | <10 | <10 | 512 |

| A/quail/Lebanon/272/2010 | 1600 | 3200 | 51200 | 100 | <10 | 128 | 2048 |

| A/quail/UAE/D1556/2011 | - | - | - | - | 320 | - | - |

“-”Not done. Bold font indicates cross-reactivity of the antibody with its homologous virus.

Fig. 5.

Antigenic cartography representation of the hemagglutination inhibition data generated using a panel of polyclonal (A) and monoclonal (B) antibodies. The map was produced using AntigenMap (http://sysbio.cvm.msstate.edu/AntigenMap). One unit (grid) represents a twofold change in the HI results. Isolates of each year are indicated by symbols and colors.

All isolates reacted well with mAbs G1-26 and G9-25. Less reactivity was observed with 18G4.B11.F9. The 1073-9 mAb differentiated isolates into three groups (HI titer >800, ≤800, and <100). The results revealed that mAb G9-25 is ten times more reactive than G1-26 (Table 5). The antigenic cartography generated using the HI titers against the mAbs revealed that the Egyptian viruses cluster together, with only one strain excluded from this cluster (Fig. 5B).

Discussion

Since the 1990s, avian influenza H9N2 viruses have continuously circulated in domestic poultry in the Middle East. Active surveillance studies in Egypt identified H9N2 virus infection in a broiler chicken in December 2010 [38]. The delayed emergence of H9N2 in Egypt remains unclear. Circulation of H9N2 in the presence of the enzootic H5N1 subtype provides an opportunity for genetic reassortment and emergence of new viruses with pandemic potential. This situation warrants active surveillance and characterization of the circulating H9N2 and H5N1 viruses in farmed poultry.

Phylogenetic analysis showed that the Egyptian H9N2 viruses are very homogenous and are closely related to recently characterized H9N2 viruses from neighboring Middle Eastern countries. This indicates that the emergence of H9N2 in Egypt might have been due to the importation of this virus through wild birds, legal or illegal trade of poultry, or another unidentified mechanism.

Our study showed that the recently isolated H9N2 viruses from Egypt contain four gene segments (HA, NA, NS and M) belonging to cluster B, and the remaining segments belong to cluster A, as shown previously [38]. The PB2, HA, NA and M segments of Egyptian isolates share the same progenitor, A/quail/HK/G1/1997(H9N2). The Egyptian NP gene was closely related to that of another ancestor, A/chicken/Korea/38349-p96323/96(H9N2). The PB1 genes grouped with A/Pekin robin/California/30412/1994(H7N1). Egyptian PA had the progenitor A/duck/Hong Kong/Y439/1997 (H9N2). The NS genes were closely related to A/chicken/Karachi/NARC-100/2004(H7N3), with about 94% sequence identity. The closer relationship of the internal genes of recently identified H9N2 viruses in the Middle East to other subtypes such as H7N1, H7N3, and H5N1, with identity ranging from 92 to 95%, than to older H9N2 viruses indicated intra-subtype reassortment among these viruses. Several previous studies showed reassortment between H9N2 viruses and highly pathogenic H7N3 and H5N1 viruses [28, 39, 62]. Although Egyptian H9N2 viruses were isolated from a country where H5N1 is enzootic, no evidence of reassortment was identified.

Several human sero-epidemiological studies have provided evidence of H9N2 infection in several countries [41, 43, 50, 60]. It has been reported that H9N2 viruses have acquired receptor-binding characteristics typical of human strains that might increase the potential for reassortment in both human and pig respiratory tracts [54]. The RBS of HA of Egyptian H9N2 viruses had the Q234L substitution, which has been implicated in human-virus-like receptor specificity and is critical for replication and direct transmission of H9N2 viruses in ferrets [27, 53]. L234 changes receptor specificity to mammalian cells, and experimentally, this substitution has been shown to increase replication in human cells in vitro (with 100-fold higher peak titers) [36]; this substitution was identified in all Egyptian isolates. The combination of H191, E198 and L234, which was typical of early human H3N2 isolates, is observed in Egyptian isolates [47]. Furthermore, various studies have shown that internal viral proteins are important in determining the host range of influenza A viruses [9]. Several distinct molecular markers that are associated with virus transmission and adaptation to mammalian host were identified in Egyptian isolates [3, 38]. H9N2 viruses have acquired many substitutions associated with virulence in mammals. All of the Egyptian isolates have the PDZ domain of “K/RSEV” and S42 in NS1, which can increase the virulence of avian influenza virus in mammalian models [30, 42]. Several residues in the PB1, PB2, PA, and M genes associated with virulence of Egyptian H9N2 viruses in mammals were observed. Analysis of HA cleavage sequences of Egyptian isolates revealed K/RSSR motifs, indicating low pathogenicity in chickens. Substitution of one or two serines at the C-terminus of HA1 with basic amino acids may increase the pathogenicity of the virus in poultry as described previously [46]. Low-pathogenic avian influenza viruses bearing the avirulent-type sequence RXXR have the potential to become highly pathogenic while circulating in chickens [29]. Egyptian H9N2 viruses possess basic amino acids at P1 and P4 and thus need minor mutations at P2 and P3 to acquire a polybasic site and become highly pathogenic. In the HA of nearly all of the isolates that we analyzed, two potential glycosylation sites were lost. Previous studies showed a relationship between the addition of glycosylation sites on the HA and a loss of H5N1 virulence as well as a decrease in receptor-binding specificity of H2 viruses [31]. Also, a change in the glycosylation pattern may represent an adaptation of H9N2 within poultry [4].

Antigenic analysis of 17 Egyptian isolates showed the relationship of Egyptian H9N2 viruses to members of the G1 and G9 lineages. None of the Egyptian isolates reacted well with antiserum against A/quail/UAE/D1556/2011. HA analysis of this UAE isolate revealed that this virus was genetically distinct when compared to Egyptian viruses, which may explain the low reactivity of antibodies raised against this virus with Egyptian strains.

Among the H9N2 genes, the PB1-F2 and M2 genes seem to be under positive natural selection, but, as discussed by Holmes et al. [25], this is probably due to the overlap of the PB1 and PB1-F2 ORFs (a shift of 1 nt compared with PB1 ORF) and therefore is likely to represent an artifact [25].

Our analysis indicated that H9N2 viruses in Egypt possess several genetic markers that enhance virulence in poultry and transmission to humans. This was previously shown in other studies in which Egyptian H9N2 viruses were analyzed [2, 3, 38]. However, these studies were based on the analysis of the full or partial genome of a single strain [2, 3] or a small number of completely sequenced viruses [38]. Our analysis included a larger number of viruses isolated over a longer period of time and included more-detailed analysis.

In a country where H5N1 is enzootic and causes human cases, circulation of H9N2 may hinder H5N1 control efforts and increase the burden on human health. Thus, monitoring the genetic and antigenic signatures of circulating avian influenza viruses by active surveillance programs are needed to obtain more information on the virulence and antigenic properties of the new strains in avian and mammalian hosts.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, under contract number HHSN266200700005C, and by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Aamir UB, Wernery U, Ilyushina N, Webster RG. Characterization of avian H9N2 influenza viruses from United Arab Emirates 2000 to 2003. Virology. 2007;361:45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.10.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abdel-Moneim AS, Afifi MA, El-Kady MF. Isolation and mutation trend analysis of influenza A virus subtype H9N2 in Egypt. Virology journal. 2012;9:173. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-9-173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arafa AS, Hagag N, Erfan A, Mady W, El-Husseiny M, Adel A, Nasef S. Complete genome characterization of avian influenza virus subtype H9N2 from a commercial quail flock in Egypt. Virus genes. 2012;45:283–294. doi: 10.1007/s11262-012-0775-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baigent SJ, McCauley JW. Influenza type A in humans, mammals and birds: determinants of virus virulence, host-range and interspecies transmission. BioEssays: news and reviews in molecular, cellular and developmental biology. 2003;25:657–671. doi: 10.1002/bies.10303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bashashati M, Vasfi Marandi M, Sabouri F. Genetic diversity of early (1998) and recent (2010) avian influenza H9N2 virus strains isolated from poultry in Iran. Archives of virology. 2013;158:2089–2100. doi: 10.1007/s00705-013-1699-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butt KM, Smith GJ, Chen H, Zhang LJ, Leung YH, Xu KM, Lim W, Webster RG, Yuen KY, Peiris JS, Guan Y. Human infection with an avian H9N2 influenza A virus in Hong Kong in 2003. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2005;43:5760–5767. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.11.5760-5767.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cai Z, Zhang T, Wan XF. A computational framework for influenza antigenic cartography. PLoS computational biology. 2010;6:e1000949. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cai Z, Zhang T, Wan XF. Concepts and applications for influenza antigenic cartography. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2011;5(Suppl 1):204–207. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen GW, Chang SC, Mok CK, Lo YL, Kung YN, Huang JH, Shih YH, Wang JY, Chiang C, Chen CJ, Shih SR. Genomic signatures of human versus avian influenza A viruses. Emerging infectious diseases. 2006;12:1353–1360. doi: 10.3201/eid1209.060276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen W, Calvo PA, Malide D, Gibbs J, Schubert U, Bacik I, Basta S, O’Neill R, Schickli J, Palese P, Henklein P, Bennink JR, Yewdell JW. A novel influenza A virus mitochondrial protein that induces cell death. Nature medicine. 2001;7:1306–1312. doi: 10.1038/nm1201-1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conenello GM, Tisoncik JR, Rosenzweig E, Varga ZT, Palese P, Katze MG. A single N66S mutation in the PB1-F2 protein of influenza A virus increases virulence by inhibiting the early interferon response in vivo. Journal of virology. 2011;85:652–662. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01987-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dankar SK, Wang S, Ping J, Forbes NE, Keleta L, Li Y, Brown EG. Influenza A virus NS1 gene mutations F103L and M106I increase replication and virulence. Virology journal. 2011;8:13. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-8-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delport W, Poon AF, Frost SD, Kosakovsky Pond SL. Datamonkey 2010: a suite of phylogenetic analysis tools for evolutionary biology. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2455–2457. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.El-Shesheny R, Kayali G, Kandeil A, Cai Z, Barakat AB, Ghanim H, Ali MA. Antigenic diversity and cross-reactivity of avian influenza H5N1 viruses in Egypt between 2006 and 2011. The Journal of general virology. 2012;93:2564–2574. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.043299-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fusaro A, Monne I, Salviato A, Valastro V, Schivo A, Amarin NM, Gonzalez C, Ismail MM, Al-Ankari AR, Al-Blowi MH, Khan OA, Maken Ali AS, Hedayati A, Garcia Garcia J, Ziay GM, Shoushtari A, Al Qahtani KN, Capua I, Holmes EC, Cattoli G. Phylogeography and evolutionary history of reassortant H9N2 viruses with potential human health implications. Journal of virology. 2011;85:8413–8421. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00219-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghazi Kayali AK, El-Shesheny Rabeh, Kayed Ahmed S, Gomaa Mokhtar M, Maatouq Asmaa M, Shehata Mahmoud M, Moatasim Yassmin, Bagato Ola, Cai Zhipeng, Rubrum Adam, Kutkat Mohamed A, McKenzie Pamela P, Webster Robert G, Webby Richard J, Ali Mohamed A. Active Surveillance for Avian Influenza Virus, Egypt, 2010–2012. Emerging Infectious Disease Journal. 2014:20. doi: 10.3201/eid2004.131295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Golender N, Panshin A, Banet-Noach C, Nagar S, Pokamunski S, Pirak M, Tendler Y, Davidson I, Garcia M, Perk S. Genetic characterization of avian influenza viruses isolated in Israel during 2000–2006. Virus genes. 2008;37:289–297. doi: 10.1007/s11262-008-0272-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guan Y, Shortridge KF, Krauss S, Webster RG. Molecular characterization of H9N2 influenza viruses: were they the donors of the “internal” genes of H5N1 viruses in Hong Kong? Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96:9363–9367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.9363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guan Y, Shortridge KF, Krauss S, Chin PS, Dyrting KC, Ellis TM, Webster RG, Peiris M. H9N2 influenza viruses possessing H5N1-like internal genomes continue to circulate in poultry in southeastern China. Journal of virology. 2000;74:9372–9380. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.20.9372-9380.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guo Y, Li J, Cheng X. Discovery of men infected by avian influenza A (H9N2) virus. Zhonghua shi yan he lin chuang bing du xue za zhi = Zhonghua shiyan he linchuang bingduxue zazhi = Chinese journal of experimental and clinical virology. 1999;13:105–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guo YJ, Krauss S, Senne DA, Mo IP, Lo KS, Xiong XP, Norwood M, Shortridge KF, Webster RG, Guan Y. Characterization of the pathogenicity of members of the newly established H9N2 influenza virus lineages in Asia. Virology. 2000;267:279–288. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.0115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ha Y, Stevens DJ, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. X-ray structures of H5 avian and H9 swine influenza virus hemagglutinins bound to avian and human receptor analogs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:11181–11186. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201401198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hall TA. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp. 1999;41:95–98. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoffmann E, Stech J, Guan Y, Webster RG, Perez DR. Universal primer set for the full-length amplification of all influenza A viruses. Archives of virology. 2001;146:2275–2289. doi: 10.1007/s007050170002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holmes EC, Lipman DJ, Zamarin D, Yewdell JW. Comment on “Large-scale sequence analysis of avian influenza isolates”. Science. 2006;313:1573. doi: 10.1126/science.1131729. author reply 1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Homme PJ, Easterday BC. Avian influenza virus infections. I. Characteristics of influenza A-turkey-Wisconsin-1966 virus. Avian diseases. 1970;14:66–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Imai M, Herfst S, Sorrell EM, Schrauwen EJ, Linster M, De Graaf M, Fouchier RA, Kawaoka Y. Transmission of influenza A/H5N1 viruses in mammals. Virus research. 2013;178:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2013.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iqbal M, Yaqub T, Reddy K, McCauley JW. Novel genotypes of H9N2 influenza A viruses isolated from poultry in Pakistan containing NS genes similar to highly pathogenic H7N3 and H5N1 viruses. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e5788. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ito T, Goto H, Yamamoto E, Tanaka H, Takeuchi M, Kuwayama M, Kawaoka Y, Otsuki K. Generation of a highly pathogenic avian influenza A virus from an avirulent field isolate by passaging in chickens. Journal of virology. 2001;75:4439–4443. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.9.4439-4443.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jiao P, Tian G, Li Y, Deng G, Jiang Y, Liu C, Liu W, Bu Z, Kawaoka Y, Chen H. A single-amino-acid substitution in the NS1 protein changes the pathogenicity of H5N1 avian influenza viruses in mice. Journal of virology. 2008;82:1146–1154. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01698-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaverin NV, Smirnov YA, Govorkova EA, Rudneva IA, Gitelman AK, Lipatov AS, Varich NL, Yamnikova SS, Makarova NV, Webster RG, Lvov DK. Cross-protection and reassortment studies with avian H2 influenza viruses. Archives of virology. 2000;145:1059–1066. doi: 10.1007/s007050070109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kawaoka Y, Webster RG. Sequence requirements for cleavage activation of influenza virus hemagglutinin expressed in mammalian cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1988;85:324–328. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.2.324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kayali G, El-Shesheny R, Kutkat MA, Kandeil AM, Mostafa A, Ducatez MF, McKenzie PP, Govorkova EA, Nasraa MH, Webster RG, Webby RJ, Ali MA. Continuing threat of influenza (H5N1) virus circulation in Egypt. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:2306–2308. doi: 10.3201/eid1712.110683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin YP, Shaw M, Gregory V, Cameron K, Lim W, Klimov A, Subbarao K, Guan Y, Krauss S, Shortridge K, Webster R, Cox N, Hay A. Avian-to-human transmission of H9N2 subtype influenza A viruses: relationship between H9N2 and H5N1 human isolates. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97:9654–9658. doi: 10.1073/pnas.160270697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu D, Shi W, Shi Y, Wang D, Xiao H, Li W, Bi Y, Wu Y, Li X, Yan J, Liu W, Zhao G, Yang W, Wang Y, Ma J, Shu Y, Lei F, Gao GF. Origin and diversity of novel avian influenza A H7N9 viruses causing human infection: phylogenetic, structural, and coalescent analyses. Lancet. 2013;381:1926–1932. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60938-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matrosovich MN, Matrosovich TY, Gray T, Roberts NA, Klenk HD. Human and avian influenza viruses target different cell types in cultures of human airway epithelium. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:4620–4624. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308001101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mitnaul LJ, Matrosovich MN, Castrucci MR, Tuzikov AB, Bovin NV, Kobasa D, Kawaoka Y. Balanced hemagglutinin and neuraminidase activities are critical for efficient replication of influenza A virus. Journal of virology. 2000;74:6015–6020. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.13.6015-6020.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Monne I, Hussein HA, Fusaro A, Valastro V, Hamoud MM, Khalefa RA, Dardir SN, Radwan MI, Capua I, Cattoli G. H9N2 influenza A virus circulates in H5N1 endemically infected poultry population in Egypt. Influenza and other respiratory viruses. 2013;7:240–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2012.00399.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Monne I, Yamage M, Dauphin G, Claes F, Ahmed G, Giasuddin M, Salviato A, Ormelli S, Bonfante F, Schivo A, Cattoli G. Reassortant avian influenza A(H5N1) viruses with H9N2-PB1 gene in poultry, Bangladesh. Emerging infectious diseases. 2013;19:1630–1634. doi: 10.3201/eid1910.130534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Naeem K, Ullah A, Manvell RJ, Alexander DJ. Avian influenza A subtype H9N2 in poultry in Pakistan. The Veterinary record. 1999;145:560. doi: 10.1136/vr.145.19.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ninomiya A, Takada A, Okazaki K, Shortridge KF, Kida H. Seroepidemiological evidence of avian H4, H5, and H9 influenza A virus transmission to pigs in southeastern China. Veterinary microbiology. 2002;88:107–114. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(02)00105-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Obenauer JC, Denson J, Mehta PK, Su X, Mukatira S, Finkelstein DB, Xu X, Wang J, Ma J, Fan Y, Rakestraw KM, Webster RG, Hoffmann E, Krauss S, Zheng J, Zhang Z, Naeve CW. Large-scale sequence analysis of avian influenza isolates. Science. 2006;311:1576–1580. doi: 10.1126/science.1121586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pawar SD, Tandale BV, Raut CG, Parkhi SS, Barde TD, Gurav YK, Kode SS, Mishra AC. Avian influenza H9N2 seroprevalence among poultry workers in Pune, India, 2010. PLoS One. 2012;7:e36374. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rolling T, Koerner I, Zimmermann P, Holz K, Haller O, Staeheli P, Kochs G. Adaptive mutations resulting in enhanced polymerase activity contribute to high virulence of influenza A virus in mice. Journal of virology. 2009;83:6673–6680. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00212-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seo SH, Hoffmann E, Webster RG. The NS1 gene of H5N1 influenza viruses circumvents the host anti-viral cytokine responses. Virus research. 2004;103:107–113. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2004.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shanmuganatham K, Feeroz MM, Jones-Engel L, Smith GJ, Fourment M, Walker D, McClenaghan L, Alam SM, Hasan MK, Seiler P, Franks J, Danner A, Barman S, McKenzie P, Krauss S, Webby RJ, Webster RG. Antigenic and molecular characterization of avian influenza A(H9N2) viruses, Bangladesh. Emerging infectious diseases. 2013:19. doi: 10.3201/eid1909.130336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sorrell EM, Wan H, Araya Y, Song H, Perez DR. Minimal molecular constraints for respiratory droplet transmission of an avian-human H9N2 influenza A virus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:7565–7570. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900877106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Molecular biology and evolution. 2011;28:2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tosh C, Nagarajan S, Behera P, Rajukumar K, Purohit K, Kamal RP, Murugkar HV, Gounalan S, Pattnaik B, Vanamayya PR, Pradhan HK, Dubey SC. Genetic analysis of H9N2 avian influenza viruses isolated from India. Archives of virology. 2008;153:1433–1439. doi: 10.1007/s00705-008-0131-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Uyeki TM, Nguyen DC, Rowe T, Lu X, Hu-Primmer J, Huynh LP, Hang NL, Katz JM. Seroprevalence of antibodies to avian influenza A (H5) and A (H9) viruses among market poultry workers, Hanoi, Vietnam, 2001. PLoS One. 2012;7:e43948. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vatandour S, MB, HS, SC, Bakhtiari aS. Molecular characterization and phylogenetic analysis of neuraminidase gene of avian Influenza H9N2 viruses isolated from commercial broiler chicken in Iran during a period of 1998–2007. African Journal of Microbiology Research. 2011;5:4182–4189. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wagner R, Wolff T, Herwig A, Pleschka S, Klenk HD. Interdependence of hemagglutinin glycosylation and neuraminidase as regulators of influenza virus growth: a study by reverse genetics. Journal of virology. 2000;74:6316–6323. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.14.6316-6323.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wan H, Perez DR. Amino acid 226 in the hemagglutinin of H9N2 influenza viruses determines cell tropism and replication in human airway epithelial cells. Journal of virology. 2007;81:5181–5191. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02827-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wan H, Sorrell EM, Song H, Hossain MJ, Ramirez-Nieto G, Monne I, Stevens J, Cattoli G, Capua I, Chen LM, Donis RO, Busch J, Paulson JC, Brockwell C, Webby R, Blanco J, Al-Natour MQ, Perez DR. Replication and transmission of H9N2 influenza viruses in ferrets: evaluation of pandemic potential. PloS one. 2008;3:e2923. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang J, Sun Y, Xu Q, Tan Y, Pu J, Yang H, Brown EG, Liu J. Mouse-adapted H9N2 influenza A virus PB2 protein M147L and E627K mutations are critical for high virulence. PloS one. 2012;7:e40752. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wanzeck K, Boyd KL, McCullers JA. Glycan shielding of the influenza virus hemagglutinin contributes to immunopathology in mice. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2011;183:767–773. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201007-1184OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Webster RG, Bean WJ, Gorman OT, Chambers TM, Kawaoka Y. Evolution and ecology of influenza A viruses. Microbiological reviews. 1992;56:152–179. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.1.152-179.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.WHO. WHO Manual on Animal Influenza Diagnosis and Surveillance. Geneva, Switzerland: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 59.WHO. WHO Information for Laboratory Diagnosis of New Influenza A (H1N1) Virus in Humans, 21 May 2009. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Woo JT, Park BK. Seroprevalence of low pathogenic avian influenza (H9N2) and associated risk factors in the Gyeonggi-do of Korea during 2005–2006. Journal of veterinary science. 2008;9:161–168. doi: 10.4142/jvs.2008.9.2.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xu KM, Li KS, Smith GJ, Li JW, Tai H, Zhang JX, Webster RG, Peiris JS, Chen H, Guan Y. Evolution and molecular epidemiology of H9N2 influenza A viruses from quail in southern China, 2000 to 2005. Journal of virology. 2007;81:2635–2645. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02316-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhao G, Gu X, Lu X, Pan J, Duan Z, Zhao K, Gu M, Liu Q, He L, Chen J, Ge S, Wang Y, Chen S, Wang X, Peng D, Wan H, Liu X. Novel reassortant highly pathogenic H5N2 avian influenza viruses in poultry in China. PloS one. 2012;7:e46183. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhou B, Pearce MB, Li Y, Wang J, Mason RJ, Tumpey TM, Wentworth DE. Asparagine substitution at PB2 residue 701 enhances the replication, pathogenicity, and transmission of the 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza A virus. PloS one. 2013;8:e67616. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.