Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To analyze the prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding and the association with the Breastfeeding-Friendly Primary Care Unit Initiative.

METHODS

Cross-sectional study, whose data source were research on feeding behaviors in the first year of life conducted in the vaccination campaigns of 2003 and 2006, at the municipality of Barra Mansa, RJ, Southeastern Brazil. For the purposes of this study, infants under six months old, accounting for a total of 589 children in 2003 and 707 children in 2006, were selected. To verify the relationship between being followed-up by Breastfeeding-Friendly Primary Care Unit Initiative units and exclusive breastfeeding practice, only data from the 2006 inquiry was used. Variables that in the bivariate analysis were associated (p-value ≤ 0.20) with the outcome (exclusive breastfeeding practice) were selected for multivariate analysis. Prevalence ratios (PR) of exclusive breastfeeding were obtained by Poisson Regression with robust variance through a hierarchical model. The final model included the variables that reached p-value ≤ 0.05.

RESULTS

The prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding increased from 30.2% in 2003 to 46.7% in 2006. Multivariate analysis showed that mother's low education level reduced exclusive breastfeeding practice by 20.0% (PR = 0.798; 95%CI 0.684;0.931), cesarean delivery by 16.0% (PR = 0.838; 95%CI 0.719;0.976), and pacifier use by 41.0% (PR = 0.589; 95%CI 0.495;0.701). In the multiple analysis, each day of the infant's life reduced exclusive breastfeeding prevalence by 1.0% (PR = 0.992; 95%CI 0.991;0.994). Being followed-up by Breastfeeding-Friendly Primary Care Initiative units increased exclusive breastfeeding by 19.0% (PR = 1.193; 95%CI 1.020;1.395).

CONCLUSIONS

Breastfeeding-Friendly Primary Care Unit Initiative contributed to the practice of exclusive breastfeeding and to the advice for pregnant women and nursing mothers when implemented in the primary health care network.

Keywords: Breast Feeding, Infant Nutrition, Maternal-Child Health Centers, Quality of Health Care, Primary Health Care, Cross-Sectional Studies

INTRODUCTION

Studies have shown the advantages of breastfeeding, as breast milk contains the perfect balance of nutrients and the ideal bio-availability for the baby's development, as well as its emotional aspect and the species specific protection human milk provides. 13 Breastfeeding may contribute to preventing morbidities in adulthood. 21 Exclusive breastfeeding also has significant impact on reducing infant morbidity and mortality. 8

Marketing by the baby food industry, lack of legislation to protect breastfeeding, inappropriate hospital practice of separating mother and baby in the immediate post-partum and programs distributing free samples of formula have all meant that by the end of the 1970s early weaning was increasing in Brazil. This had repercussions on infant mortality. Over the next three decades, various public policies were implemented in order to recover the practice of breastfeeding. The Brazilian Code of Marketing of Breast milk Substitutes came into force, the Brazilian Network of Human Milk Banks was set up and the right to 120 days maternity leave and 5 days paternity leave was included in the Constitution. The World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) launched the BabyFriendly Hospital Initiative at the beginning of the 1990s, and established the "Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding" with the aim of improving hospital practices. 19

The increase in breastfeeding due to these policies can be observed in national surveys. The prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding went from 38.6% in 2006 to 41.0% in 2008. 24 Exclusive breastfeeding in Brazilian state capitals and regions behaved heterogeneously. The highest prevalence was observed in the North (45.9%) and the lowest in the Northeast (37.0%), according to the II Survey of the Prevalence of Breastfeeding in the Brazilian State Capitals and the Federal District in 2008. a The state capital with the highest prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding was Belém, PA, Northern Brazil (56.1%); Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Southeastern Brazil, had a prevalence of 40.7%, and the lowest prevalence was in Cuiabá, MT, Midwest Brazil (27.1%). 24 Median duration of exclusive breastfeeding went from one month in 1996 to 42 days in 2006 b and 54.1 days in 2008. a Brazil is still far from the six months of exclusive breastfeeding recommended by the WHO. c

Aiming to improve these indicators, the Rio de Janeiro State Department of Health launched the Breastfeeding-Friendly Primary Care Initiative (IUBAAM), in 1999, seeking to make promotion, protection and support of breastfeeding part of primary care. This initiative proposed to implement the "Ten Steps to successful Breastfeeding" in primary health care units. These ten steps are the result of a systematic review of interventions developed in the antenatal stage and mother-baby monitoring which have been effective in extending breastfeeding duration. 14 The first Breastfeeding-Friendly Primary Care Unit was accredited in 2001, a Family Health Care Strategy Unit in the municipality of Volta Redonda, RJ, Southeastern Brazil. In 2005, this initiative was regulated by the Rio de Janeiro State Department of Health.d There are now more than 80 accredited units in the state of Rio de Janeiro, 20 of them in Barra Mansa, the municipality with the most accredited units.16 Despite high levels of adherence to this policy, there has so far been no evaluation of changes in the practice of exclusive breastfeeding in Barra Mansa.

This study aimed to analyze the prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding and the association with being cared for in a Breastfeeding-Friendly Primary Care Unit.

METHODS

This was a cross-sectional observational study. The source of the data used was the "Survey of feeding practices in the first year of life", conducted during the National Vaccination Campaign in 2003 and 2006 and based on experience from the Breastfeeding and Municipalities Project. e This project has been developed by the Sao Paulo Institute of Health since 1998, with the aim of monitoring baby feeding practices. 23,25 A database was produced by the Barra Mansa Municipal Department of Health, Integrated Women's, Children's and Adolescent's Health Care Program, for the 2003 and 2006 surveys.

The municipality of Barra Mansa, located in the Medium Paraiba region of the state of Rio de Janeiro, has a population of about 178 thousand, 99.0% of whom are resident in the urban area. The number of live births in the municipality in 2003 was 2,390, with an infant mortality rate of 12.9/1,000 live births. The coverage of the multi-vaccine campaign in the same year was 99.0%. In 2006 there were 2,342 live births, with an infant mortality rate of 10.6/1,000 live births and vaccine coverage of 96.0%, according to the Barra Mansa Municipal Department of Health. f

A representative sample was taken of mothers (or carers) of babies aged under one year at vaccination centers in order to survey feeding habits. For this study, the outcome of which was the practice of exclusive breastfeeding, babies aged under six months were included, giving a total of 589 interviewees in 32 vaccination centers in 2003 and 707 in 36 vaccination centers in 2006. The survey was developed using two-stage cluster sampling. As the children were not uniformly distributed throughout the various vaccination centers (clusters), two-stage sampling was adopted. In the first stage, the vaccination centers were selected, and the mothers at the centers in the second stage. Sampling plans were drawn up based on data on the number of vaccination centers in each health district and the estimated number of children less than one year old, provided by the Barra Mansa Municipal Department of Health. d This estimate was made based on the vaccination campaign spreadsheet from the previous year. The resulting sample was considered equiprobabilistic or self-weighted, avoiding the need to consider weighting in the statistical analysis. 25

The interviews were conducted by community health workers and undergraduate nursing students, trained by the Integrated Women's, Children's and Adolescent's Health Care Program team and supervised by nurses from the vaccination centers, under the coordination of the Food and Nutrition Technical Department. The interviewers were given guidance in applying the questionnaire and approaching the mothers waiting in line for the vaccination, informing them about the research, emphasizing that participation was voluntary and that verbal consent was needed to apply the questionnaire. The data collection instrument was mainly composed of closed questions on consumption in preceding 24hrs of: breast milk, water, tea, other liquids, types of milk and other foods (current status). It was then possible to typify the child as being exclusively breastfed in the 24 hrs preceding the interview, according to WHO definitions. a Data were collected on mothers and babies, aiming to analyze patterns of feeding according to characteristics of the population.

The composition of the population was analyzed by constructing frequency distribution of the mothers and their babies, according to the diverse exposure variables investigated, in order to compare the interviewees from 2003 and 2006. The homogeneity of distribution of these variables between 2003 and 2006 was assessed using the Chi-square test, with a 5% level of significance (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and reproductive characteristics of the mother, of the birth, of the baby and health care received by the baby, for babies under six months. Barra Mansa, RJ, Southeastern Brazil, 2003 and 2006.

| Characteristics | 2003 | 2006 | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |||

| Mother’s age (years) | 0.883 | |||||

| 13 to 19 | 83 | 16.6 | 104 | 17.0 | ||

| 20 to 46 | 416 | 83.4 | 509 | 83.0 | ||

| Student | 0.138 | |||||

| Yes | 32 | 6.4 | 62 | 8.7 | ||

| No | 467 | 93.6 | 648 | 91.3 | ||

| Mother’s schooling | < 0.001 | |||||

| Completed primary school | 277 | 55.7 | 310 | 45.1 | ||

| Completed high school and over | 220 | 44.3 | 378 | 54.9 | ||

| Paid work | < 0.001 | |||||

| Yes | 173 | 34.7 | 126 | 17.8 | ||

| No | 326 | 65.3 | 580 | 82.2 | ||

| Births | 0.129 | |||||

| First | 239 | 47.9 | 370 | 52.3 | ||

| Multiple | 260 | 52.1 | 337 | 47.7 | ||

| Municipality of birth | 0.003 | |||||

| Barra Mansa | 440 | 74.6 | 573 | 81.4 | ||

| Other | 150 | 25.4 | 131 | 18.6 | ||

| Born in the Baby-Friendly hospital | 0.001 | |||||

| No | 525 | 89.0 | 662 | 94.2 | ||

| Yes | 65 | 11.0 | 41 | 5.8 | ||

| Type of delivery | < 0.001 | |||||

| Cesarean | 352 | 59.9 | 494 | 70.2 | ||

| Vaginal | 236 | 40.1 | 210 | 29.8 | ||

| Sex | 0.996 | |||||

| Female | 291 | 49.7 | 351 | 49.6 | ||

| Male | 295 | 50.3 | 356 | 50.4 | ||

| Birth weight (g) | 0.333 | |||||

| < 2,500 | 59 | 10.2 | 60 | 8.6 | ||

| ≥ 2,500 | 519 | 89.8 | 636 | 91.4 | ||

| Baby’s age (months) | 0.353 | |||||

| 0 to 3 | 311 | 52.8 | 355 | 50.2 | ||

| 4 to 5 | 278 | 47.2 | 352 | 49.8 | ||

| Hospitalized | 0.055 | |||||

| Yes | 31 | 5.3 | 29 | 4.1 | ||

| No | 556 | 94.7 | 674 | 95.9 | ||

| Use of pacifier | 0.009 | |||||

| Yes | 299 | 50.9 | 308 | 43.6 | ||

| No | 289 | 49.1 | 399 | 56.4 | ||

| Vaccination center | 0.055 | |||||

| Rural | 13 | 2.2 | 29 | 4.1 | ||

| Urban | 576 | 97.8 | 678 | 95.9 | ||

| Monitored in a Breastfeeding-Friendly Primary Health Care Center | < 0.001 | |||||

| Yes | 0 | 0.0 | 188 | 26.6 | ||

| No | 589 | 100.0 | 519 | 73.4 | ||

The 2006 survey became the base for estimating the association between the IUBAAM and the practice of exclusive breastfeeding. Data was analyzed using the SPSS17 program. The type of breastfeeding practiced in the first six months was verified (exclusive; predominant; complementary; not breastfed). g Bivariate analysis was developed for each dichotomously expressed exposure variable and the outcome (exclusive breastfeeding). The Chi-square test for independence was used and prevalence ratios (PR), with their respective 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) obtained. Exposure variables which proved to be associated with the outcome, with p ≤ 0.20 in the Chi-square test in the bivariate analysis were selected for the multiple analysis.

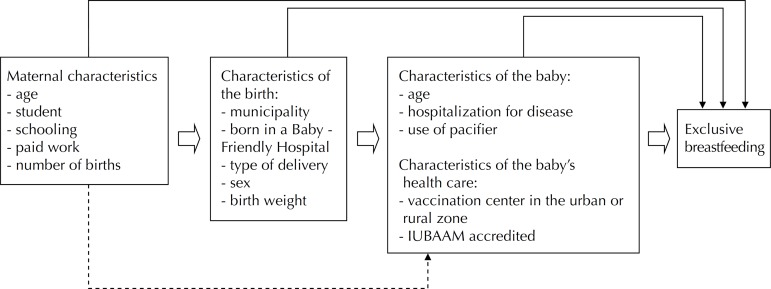

The adjusted prevalence ratios were obtained using a Poisson regression model with robust variance, as the outcome was highly prevalent. 7 The final model, used to estimate measures of association with the respective 95% confidence intervals, was composed of exposure variables with p ≤ 0.05 and the child's age as a continuous variable. The regression followed a hierarchical model, 26 considering the characteristics of the mother as distal, the characteristics of the birth as intermediary, and the characteristics of the baby and the health care unit as proximal (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Characteristics of the mother, birth, baby and health care unit affecting exclusive breastfeeding. Barra Mansa, RJ, Southeastern Brazil, 2006.

This study was not submitted to an Ethics Committee for evaluation of the risks involved to humans, as it used a database of secondary data, with no way of identifying individuals, as per Resolution 196/96.

RESULTS

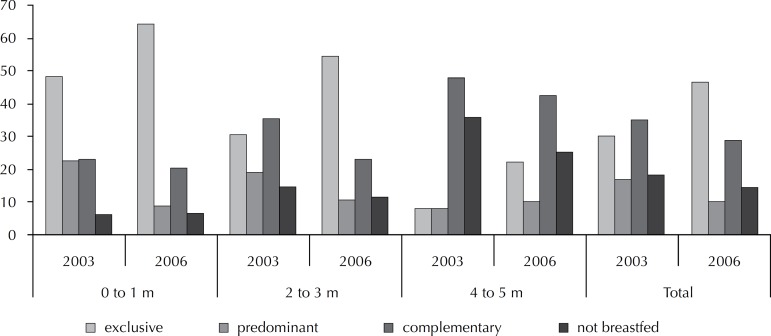

The prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding in babies aged under six months was 30.2% in 2003. Predominant breastfeeding occurred in 17.0% of cases, complementary breastfeeding in 34.8% and 18.1% were not breastfed. In 2006, exclusive breastfeeding was practiced in 46.7% of cases, predominant in 9.8%, complementary in 28.8% and 14.7% were not breastfed. Exclusive breastfeeding increased by 55.0% between 2003 and 2006. This increased with the child's age: 33.0% in the first two months, 79.0% in the third and fourth months and 178.0% in the fifth and sixth (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Distribution of prevalence of exclusive, predominant, complementary breastfeeding and not breastfed, according to age. Barra Mansa, RJ, Southeastern Brazil, 2003 and 2006.

The population interviewed in the two surveys had similar ages (17.0% of teenage mothers), proportions of mothers who were students and proportion of first time mothers. However, the mothers' level of schooling increased, whereas the numbers in paid work decreased in the period. The proportion of live births in the municipality increased, there was a decrease in the numbers born in the Baby-Friendly Hospital and the proportion of caesarean deliveries increased. The sex of the child, birth weight, proportion hospitalized with some disease and the percentage vaccinated in the rural zone did not change. The proportion of children using pacifiers decreased. In 2003, there were no babies monitored in an IUBAAM, whereas in 2006 around ¼ of the babies was monitored in a primary health care unit accredited by the initiative (Table 1).

Table 2 shows the variables associated with exclusive breastfeeding in the bivariate analysis in 2006. Of the distal variables, risk factors for the outcome were: low levels of maternal schooling and paid work; of the intermediate variables, they were: being born in a health care unit not accredited as a "Baby-Friendly Hospital", cesarean delivery, low birth weight and being a female baby. The proximal variables shown to be risk factors were: using a pacifier and being vaccinated in a rural vaccination center. Being monitored by a breastfeeding- friendly primary care unit was a protection factor for exclusive breastfeeding.

Table 2.

Prevalence, unadjusted prevalence ratio and respective p for exclusive breastfeeding according to characteristics of the mother, of the birth, of the baby and health care received by the baby, for babies under six months. Barra Mansa, RJ, Southeastern Brazil, 2006.

| Characteristics | % EBF | PRb | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mother’s age (years) | 0.258 | |||

| 13 to 19 | 41.7 | 0.869 | ||

| 20 to 46 | 48.0 | 1 | ||

| Student | 0.297 | |||

| Yes | 40.3 | 0.846 | ||

| No | 47.6 | 1 | ||

| Mother’s schooling | 0.049 | |||

| Completed primary school | 42.9 | 0.849 | ||

| Completed high school and over | 50.5 | 1 | ||

| Paid work | 0.090 | |||

| Yes | 39.5 | 0.817 | ||

| No | 48.4 | 1 | ||

| Births | 0.544 | |||

| First | 45.6 | 0.952 | ||

| Multiple | 47.9 | 1 | ||

| Municipality of birth | 0.831 | |||

| Barra Mansa | 46.3 | 0.978 | ||

| Other | 47.3 | 1 | ||

| Born in the Baby-Friendly hospital | 0.168 | |||

| No | 46.0 | 0.819 | ||

| Yes | 56.1 | 1 | ||

| Type of delivery | 0.051 | |||

| Cesarean | 44.3 | 0.849 | ||

| Vaginal | 51.9 | 1 | ||

| Sex | 0.147 | |||

| Female | 44.0 | 0.889 | ||

| Male | 49.4 | 1 | ||

| Birth weight (g) | 0.132 | |||

| < 2,500 | 36.7 | 0.769 | ||

| ≥ 2,500 | 44.7 | 1 | ||

| Hospitalized | 0.264 | |||

| Yes | 34.6 | 0.738 | ||

| No | 46.9 | 1 | ||

| Use of pacifier | < 0.001 | |||

| Yes | 31.3 | 0.532 | ||

| No | 58.7 | 1 | ||

| Vaccination center | 0.130 | |||

| Rural | 31.0 | 0.655 | ||

| Urban | 47.4 | 1 | ||

| Monitored in a Breastfeeding-Friendly Primary Health Care Center | 0.090 | |||

| Yes | 51.6 | 1.156 | ||

| No | 45.0 | 1 | ||

EBF: Exclusive breastfeeding; PRb: Unadjusted prevalence ratio

Maternal schooling up to primary level (PR = 0.798), cesarean deliver (PR = 0.838), using a pacifier (PR = 0.589) and increasing age in days of the baby (PR = 0.992) were all risk factors for exclusive breastfeeding in the multiple model. The baby being monitored in an IUBAAM (PR = 1.193) was a protection factor for the outcome (Table 3).

Table 3.

Adjusted prevalence ratio for exclusive breastfeeding and respective p according to characteristics of the mother, of the birth, of the baby and health care received by the baby, for babies under six months. Barra Mansa, RJ, Southeastern Brazil, 2006.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Final model | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRa | p | PRa | p | PRa | p | PRa | p | 95%CI | ||

| Mother’s schooling | ||||||||||

| Completed primary school | 0.841 | 0.036 | 0.798 | 0.009 | 0.807 | 0.006 | 0.798 | 0.004 | 0.684;0.931 | |

| Completed high school and over | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Paid work | ||||||||||

| Yes | 0.821 | 0.096 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| No | 1 | |||||||||

| Born in the Baby-Friendly hospital | ||||||||||

| No | 0.828 | 0.187 | – | – | – | – | – | |||

| Yes | 1 | |||||||||

| Type of delivery | ||||||||||

| Cesarean | 0.779 | 0.004 | 0.832 | 0.018 | 0.838 | 0.023 | 0.719;0.976 | |||

| Vaginal | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Birth weight (g) | ||||||||||

| < 2,500 | 0.760 | 0.125 | – | – | – | – | – | |||

| ≥ 2,500 | 1 | |||||||||

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Female | 0.891 | 0.154 | – | – | – | – | – | |||

| Male | 1 | |||||||||

| Baby’s age | ||||||||||

| Age in days | 0.992 | < 0.001 | 0.992 | < 0.001 | 0.991;0.994 | |||||

| Vaccination center | ||||||||||

| Rural | 0.637 | 0.086 | – | – | – | |||||

| Urban | 1 | |||||||||

| Use of pacifier | ||||||||||

| Yes | 0.589 | < 0.001 | 0.589 | < 0.001 | 0.495;0.701 | |||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Monitored in a Breastfeeding-Friendly Primary Health Care Center | ||||||||||

| Yes | 1.204 | 0.020 | 1.193 | 0.027 | 1.020;1.395 | |||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

PRa: Adjusted prevalence ratio

DISCUSSION

In 2006, almost half of babies aged under six months in Barra Mansa were exclusively breastfed, a higher prevalence than that found the same year in the municipality of Rio de Janeiro (33.3%) 5 or in Bauru, SP, Southeastern Brazil (24.2%). 17 Between 2003 and 2006, a significant increase in the prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding in babies under six months in Barra Mansa was noted, higher than that found in Rio de Janeiro (42.9%) 5 or in Bauru (37.5%), 17 in the same period. However, in this study the 2003 and 2006 populations were not totally comparable. The increase observed in the period may have been encouraged by the increased levels of schooling on the parts of the mothers and by the decrease in those doing paid work, factors which may contribute to exclusive breastfeeding. A municipal maternity hospital was established in Barra Mansa in 2005, reducing the proportion of babies born in the Baby-Friendly Hospital in the neighboring municipality of Volta Redonda, and increasing the number of cesarean deliveries. The evolution in natal care does not appear to have contributed to the practice of exclusive breastfeeding. The evolution in socioeconomic and hospital related factors seemed to act in the opposite way, while the improvement in primary health care in the municipality over the period with the implementation of the IUBAAM, seemed to encourage exclusive breastfeeding and reduce use of pacifiers.

The association of the IUBAAM with the practice of exclusive breastfeeding is clearly shown in the multiple analysis of the data from the 2006 survey of feeding practices: the prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding was 19.0% higher in babies monitored in accredited units. This result was consistent with that found in other circumstances in Brazil. A study evaluating the effectiveness of the IUBAAM "ten steps", in the state of Rio de Janeiro, 15 found that the prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding was higher in blocks with regular performance (38.6%) than in blocks with poor performance (23.6%) (p < 0.001). The pre- and post-certification IUBAAM stages were compared in an investigation carried out in a primary health care unit in the east zone of the city of Rio de Janeiro. The prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding at < 4 months increased from 68.0% to 88.0%, and for babies aged between 4 and 5.9 months, from 41.0% to 82.0% (p < 0.0001). Health outcomes were analyzed in babies under four months in this study. An increase in check-ups (asymptomatic) and a decrease in appointments with complaints of diarrhea (from 11.0% to 3.4%) (p < 0.05) was observed after certification. 4 Caldeira et al 2 carried out a controlled intervention study of 20 randomly selected family health care program teams in the municipality of Montes Claros, in 2006, evaluating the impact of the IUBAAM. The median exclusive breastfeeding length went from 104 days to 125 days in the intervention group (p = 0.001) and remained unchanged in the control group. 2

In the multiple analysis, the prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding was found to be 20.0% lower in mothers with low levels of schooling. In studies in Joinville, SC, 12 in Pernambuco, 3 in the city of Rio de Janeiro, 5,18 in Cuiabá 9 and in municipalities in the state of Sao Paulo, 23 low levels of schooling was found to be associated with stopping exclusive breastfeeding. This may be because mothers with more schooling have more access to information on the advantages of this type of breastfeeding and more self-confidence in persisting with this practice in the baby's first months.

Cesarean delivery reduced the prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding by 16.0%, in this study. Cesarean delivery is a risk factor for breastfeeding at birth. 20 However, the association with the length of exclusive breastfeeding needs to be better investigated. There have been several studies that showed no association between these two factors. 3,11,17 A study in Itapira, SP, 1 found an association between cesarean delivery and stopping exclusive breastfeeding.

Using a pacifier was the main risk factor in stopping exclusive breastfeeding, reducing prevalence by 41.0%. This finding is consistent with others studies in different parts of Brazil. Less time of exclusive breastfeeding was found in children who used pacifiers (RR = 1.49) in Itaúna, MG, Southeastern Brazil. 6 Using a pacifier doubled the prevalence of stopping exclusive breastfeeding in the first six months in Bauru, SP, Southeastern Brazil, 17 and increased the prevalence of stopping by 69.0% in Joinville, SC, Southern Brazil. 12 Children who used a pacifier were twice as likely to not breastfeed exclusively in Londrina, PR, Southern Brazil; 22 whereas their use implied a three times greater chance in Cuiabá, 9 MT, Midwestern Brazil, and four times greater chance in Pelotas, RS, Southern Brazil, 11 similar to the finding in Itapira, SP. 1 Using a pacifier is a widespread cultural habit in Brazil. It is detrimental to breastfeeding as it reduces the frequency of feeds, decreasing milk production and causing nipple confusion by the different tongue positions needed when feeding from the breast or from the bottle. This use may reflect difficulties on the part of the mother, such as anxiety, insecurity and problems managing breastfeeding. 10

The prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding declines with the increasing age of the baby. This reduction, although gradual and starting in the first month of life, becomes more accentuated between four and six months, possibly due to the influence of health care professional guidance, or by the cultural habit of the early introduction of other liquids and foods, as fewer than 1/5 of mothers work outside the home. This more accentuated decrease in exclusive breastfeeding between four and six months was similar to that found in the city of Rio de Janeiro, RJ, 18 and in Joinville, SC. 12 However, the highest increase in exclusive breastfeeding was in the four to six months period, suggesting that adequate nutritional guidance and support are capable of at least partially preventing the early introduction of other liquids and foods.

Surveys in vaccination campaigns allow data to be obtained quickly and cheaply. However, there may be some limitations regarding the sampling plan in the field, given the type of survey. This may have produced selection bias in the discrepancies in the proportions of working mothers and mothers with low levels of schooling between 2003 and 2006.

The study of the determinants of exclusive breastfeeding only used data from the 2006 survey, and the multiple hierarchized analysis 26 used to measure the weight of distal maternal characteristics, of intermediate birth characteristics and of proximal characteristics of the care the baby received has been shown to be able to provide evidence of the different variables associated with exclusive breastfeeding at different levels.

It was concluded that IUBAAM contributed to the practice of exclusive breastfeeding. This initiative should be established in the primary health care network, so that all mothers and babies cared for by the Brazilian Unified Health System receive guidance and support in exclusively breastfeeding for six months.

It is recommended that the IUBAAM be articulated with the "Stork Network", an innovative Brazilian Ministry of Health strategy (Ordinance no. 1,459, 24/6/2011) created to implement a network of pregnancy, birth and child growth and development care, so that these activities, together, have a synergetic effect on the practice of exclusive breastfeeding in the first six months.

HIGHLIGHTS

Levels of exclusive breastfeeding in Brazil are still low.

The prevalence and median of exclusive breastfeeding has been gradually increasing due to the creation of the National Breastfeeding Policy in 1981, although levels are still below those recommended by the World Health Organization and the Brazilian Ministry of Health: six months of exclusive breastfeeding.

In the state of Rio de Janeiro, Southeastern Brazil, the Breastfeeding-Friendly Primary Care Unit Initiative was launched in 1999, proposing to establish "Ten Steps to Breastfeeding Success" in primary care units, making the promotion, protection and support of breastfeeding part of primary care.

In Barra Mansa, the municipality in the state with the most primary care units accredited by the initiative (n = 20), the prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding increased from 30.2% in 2003 to 46.7% in 2006. Monitoring babies in units accredited by the program increased the prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding by 19.0% (PR = 1.19; 95%CI 1.02;1.40).

The Breastfeeding-Friendly Primary Care Unit Initiative can complement the "Brazilian Breastfeeding Strategy", launched by the Ministry of Health in 2012, collaborating with the National Breastfeeding Policy in increasing rates of exclusive breastfeeding.

Professor Rita de Cássia Barradas Barata

Scientific Editor

Footnotes

Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde. Departamento de Ações Programáticas e Estratégicas. II Pesquisa de Prevalência de Aleitamento Materno nas Capitais Brasileiras e Distrito Federal. Brasília (DF); 2009.

Ministério da Saúde. Pesquisa Nacional de Demografia e Saúde da Criança e da Mulher – PNDS 2006: dimensões do processo reprodutivo e da saúde da criança. Brasília (DF); 2006.

World Health Organization. The optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding. Report of an Expert Consultation. Geneva; 2001.

Secretaria de Estado de Saúde. Implanta a Iniciativa Unidade Básica Amiga da Amamentação no Estado do Rio de Janeiro e dá outras providências. Regulamentada pela Secretaria de Estado de Saúde do Rio de Janeiro em 2005 por meio da Resolução SES Nº 2673 de 2 de março de 2005. Republicada no D.O. de 28.6.2005.

Instituto de Saúde de São Paulo. Amamentação e Municípios. São Paulo; 1998 [cited 2013 Jan 22]. Available from: http://www.saude.sp.gov.br/instituto-de-saude/homepage/acesso-rapido/arquivo-de-noticias/2013/amamunic

Annual Report of the Coordination of Epidemiological Surveillance, Barra Mansa Municipal Health Department, 2006.

World Health Organization. Indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices. Part 1: definitions. conclusions of a consensus meeting held 6–8 November 2007 in Washington D.C., USA. Geneva; 2008.

Article based on the master's dissertation of Alves A.L.N., entitled: "Evolução da prática do aleitamento materno exclusivo em Barra Mansa entre 2003 e 2006 e análise dos fatores associados à sua prática em 2006, em especial a implantação da Iniciativa Unidade Básica Amiga da Amamentação", presented to the Postgraduate Program in Collective Health, Instituto de Saúde da Comunidade, in 2012.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Audi CAF, Corrêa MAS, Latorre MRDO. Alimentos complementares e fatores associados ao aleitamento materno e ao aleitamento materno exclusivo em lactentes até 12 meses de vida em Itapira, São Paulo, 1999. Rev Bras Saude Matern Infant. 2003;3(1):85–93. doi: 10.1590/S1519-38292003000100011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caldeira AP, Fagundes GC, Aguiar GN. Intervenção educacional em equipes do Programa de Saúde da Família para promoção da amamentação. Rev Saude Publica. 2008;42(6):1027–1033. doi: 10.1590/S0034-89102008005000057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caminha MFC, Batista M, Filho, Serva VB, Arruda IKG, Figueiroa JN, Lira PIC. Time trends and factors associated with breastfeeding in the state of Pernambuco, Northeastern Brazil. Rev Saude Publica. 2010;44(2):240–248. doi: 10.1590/S0034-89102010000200003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cardoso LO, Vicente AST, Damião JJ, Rito RVVF. J Pediatr. 2. Vol. 84. Rio J: 2008. Impacto da implementação da Iniciativa Unidade Básica Amiga da Amamentação nas prevalências de aleitamento materno e nos motivos de consulta em uma unidade básica de saúde; pp. 147–153. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castro IRR, Engstrom EM, Cardoso LO, Damião JJ, Rito RVF, Gomes MASM. Tendência temporal da amamentação na cidade do Rio de Janeiro: 1996-2006. Rev Saude Publica. 2009;43(16):1021–1029. doi: 10.1590/S0034-89102009005000079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaves RG, Lamounier JA, César CC. J Pediatr. 3. Vol. 83. Rio J: 2007. Fatores associados com a duração do aleitamento materno; pp. 241–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coutinho LMS, Scazufca M, Menezes PR. Métodos para estimar razão de prevalência em estudos de corte transversal. Rev Saude Publica. 2008;42(6):992–998. doi: 10.1590/S0034-89102008000600003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Escuder MML, Venâncio SI, Pereira JCR. Estimativa de impacto da amamentação sobre a mortalidade infantil. Rev Saude Publica. 2003;37(3):319–325. doi: 10.1590/S0034-89102003000300009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.França GVA, Brunken GS, Silva SM, Escuder MM, Venâncio SI. Determinantes da amamentação no primeiro ano de vida em Cuiabá, Mato Grosso. Rev Saude Publica. 2007;41(5):711–718. doi: 10.1590/S0034-89102007000500004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jaafar SH, Jahanfar S, Angolkar M, Ho JJ. Effect of restricted pacifier use in breastfeeding term infants for increasing duration of breastfeeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;7: doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007202.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mascarenhas MLW, Albernaz EP, Silva BS, Silveira RB. J Pediatr. 4. Vol. 82. Rio J: 2006. Prevalência de aleitamento materno exclusivo nos 3 primeiros meses de vida e seus determinantes no Sul do Brasil; pp. 289–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nascimento MBR, Reis MAM, Franco SC, Issler H, Ferraro AA, Grisi SJFE. Exclusive breastfeeding in southern brazil: prevalence and associated factors. Breastfeed Med. 2010;5(2):79–85. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2009.0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Newburg DS. Neonatal protection by an innate immune system of human milk consisting of oligosaccharides and glycans. J Anim Sci. 2009;87(13):26–34. doi: 10.2527/jas.2008-1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oliveira MIC, Camacho LAB, Tedstone AE. Extending breastfeeding duration through primary care: a systematic review of prenatal and postnatal interventions. J Hum Lact. 2001;17(4):326–343. doi: 10.1177/089033440101700407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oliveira MIC, Camacho LAB, Tedstone AE. A method for the evaluation of primary health care units' practice in the promotion, protection and support of breastfeeding: results from the State of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. J Hum Lact. 2003;19(4):365–373. doi: 10.1177/0890334403258138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oliveira MIC, Rito RVVF, Barbosa GP. Carvalho MR, Tavares LAM. Amamentação: bases científicas. 3. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Guanabara Koogan; 2010. Iniciativa Unidade Básica Amiga da Amamentação: histórico e desafios; pp. 293–299. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parizoto GM, Parada CMGL, Venancio SI, Carvalhaes MABL. J Pediatr. 3. Vol. 85. Rio J: 2009. Tendência e determinantes do aleitamento materno exclusivo em crianças menores de 6 meses; pp. 201–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pereira RSV, Oliveira MIC, Andrade CLT, Brito AS. Fatores associados ao aleitamento materno exclusivo: o papel do cuidado na atenção básica. Cad Saude Publica. 2010;26(12):2343–2354. doi: 10.1590/S0102-311X2010001200013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rea MF. Reflexões sobre a amamentação no Brasil: de como passamos a 10 meses de duração. Cad Saude Publica. 2003;19(1):537–545. doi: 10.1590/S0102-311X2003000700005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silveira RB, Albernaz E, Zuccheto LM. Fatores associados ao início da amamentação em uma cidade do sul do Brasil. Rev Bras Saude Matern Infant. 2008;8(1):35–43. doi: 10.1590/S1519-38292008000100005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Toma TS, Rea MF. Benefícios da amamentação para a saúde da mulher e da criança: um ensaio sobre as evidências. Cad Saude Publica. 2008;24(2):235–246. doi: 10.1590/S0102-311X2008001400009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vannuchi MTO, Thomson Z, Escuder MML, Tacia MTGM, Venozzo KMK, Castro LMCP, et al. Perfil do aleitamento materno em menores de um ano no município de Londrina, Paraná. Rev Bras Saude Matern Infant. 2005;4(2):143–150. doi: 10.1590/S1519-38292005000200003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Venancio SI, Escuder MML, Kitoko P, Rea MF, Monteiro CA. Freqüência e determinantes do aleitamento materno em municípios do Estado de São Paulo. Rev Saude Publica. 2002;3(3):313–318. doi: 10.1590/S0034-89102002000300009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Venancio SI, Escuder MML, Saldiva SRDM, Giugliani E. J Pediatr. 4. Vol. 86. Rio J: 2010. A prática do aleitamento materno nas capitais brasileiras e Distrito Federal: situação atual e avanços; pp. 317–324. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Venancio SI, Monteiro CA. Individual and contextual determinants of exclusive breast feeding in São Paulo, Brazil: a multilevel analysis. Public Health Nutr. 2006;9(1):40–46. doi: 10.1079/PHN2005760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Victora CG, Huttly SR, Fuchs SC, Olinto MTA. The role of conceptual frameworks in epidemiological analysis: a hierarchical approach. Int J Epidemiol. 1997;26(1):224–227. doi: 10.1093/ije/26.1.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]