Abstract

Objectives:

We examined whether accordance to the DASH (Dietary Approach to Stop Hypertension) and Mediterranean diets is associated with slower cognitive decline in a prospective Chicago cohort study of older persons, the Memory and Aging Project.

Methods:

The sample comprised 826 Memory and Aging Project participants (aged 81.5 ± 7.1 years) who completed a 144-item food frequency questionnaire at baseline and 2 or more cognitive assessments over 4.1 years. Dietary scores were computed for accordance to the DASH diet (0–10) and the Mediterranean diet (MedDietScore) (0–55). For both, higher scores reflect greater accordance. Both patterns share at least 3 common food components. Cognitive function was assessed annually with 19 cognitive tests from which global cognitive scores and summary measures are computed.

Results:

The mean global cognitive score at baseline was 0.12 (range, −3.23 to 1.60) with an overall mean annual change in score of −0.08 standardized units. Only 13 participants had possible dementia. The mean DASH score was 4.1 (range, 1.0–8.5) and the MedDietScore was 31.3 (range, 18–46). In mixed models adjusted for covariates, a 1-unit difference in DASH score was associated with a slower rate of global cognitive decline by 0.007 standardized units (standard error of estimate = 0.003, p = 0.03). Similarly, a 1-unit-higher MedDietScore was associated with a slower rate of global cognitive decline by 0.002 standardized units (standard error of estimate = 0.001, p = 0.01).

Conclusions:

These findings support the hypothesis that both the DASH and Mediterranean diet patterns are associated with slower rates of cognitive decline in the same cohort of older persons.

Both the DASH (Dietary Approach to Stop Hypertension) diet and the Mediterranean-style diet have been shown to be protective against hypertension, obesity, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes.1–4 Many of these conditions also increase cognitive decline.5–7 We8 and others9,10 have observed that accordance to a Mediterranean diet (MedDiet) pattern is associated with slower cognitive decline, but others have not found such associations.11–14 Limited information is available on the relation of the DASH diet to cognitive decline. In the Exercise and Intervention for Cardiovascular Health Trial,15 124 overweight, sedentary, prehypertensive or hypertensive adults assigned to the DASH diet and weight management treatment experienced improvements in executive function, memory, learning, and perceptual speed after 4 months.

The Mediterranean-style diet has many interpretations with several features distinct from the DASH diet: the almost exclusive use of olive oil as the primary fat, high consumption of fish, and moderate consumption of wines with meals. The DASH diet specifies low consumption of saturated fat and commercial pastries and sweets, and higher consumption of dairy than in the Mediterranean pattern. In this study, we examined and compared the DASH and MedDiet pattern scores in relation to cognitive decline among older persons from a prospective cohort study with annual follow-up visits.

METHODS

Sample.

The sample largely comprised cognitively normal participants from the Memory and Aging Project (MAP), an ongoing cohort study of older persons living in Chicago retirement communities and subsidized housing that began in 1997.16 At the beginning, volunteers must be dementia-free and agree to annual clinical neurologic evaluations. The ongoing nutrition component to the MAP study began in 2004. Of the 1,555 individuals who have participated in MAP since 1997, 1,360 were alive and still actively participating when the nutritional component was instituted (80 were deceased and 115 had withdrawn participation). Of these, 951 (70%) agreed to be in the nutrition study and 826 participants had undergone 2 or more cognitive assessments and completed a valid food frequency questionnaire (FFQ).

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents.

The institutional review board of Rush University Medical Center approved the study. All participants gave written informed consent.

Dietary assessment.

The self-administered MAP FFQ is a modified 144-item version of the Chicago Health and Aging Project semiquantitative FFQ in which participants record the usual frequency of consumption of specified portions of various food items. The FFQ was completed at the first cognitive assessment and, once reviewed for completeness, the questionnaires are sent for optical scanning at Harvard University. Daily nutrient or dietary intakes were calculated as the product of frequency of the food consumed and nutrient amount of selected item, and summing these for all food items. Validation and reliability of the Chicago Health and Aging Project FFQ have been previously reported.17,18

Food items on the MAP FFQ were assigned to 7 DASH food groups, and 3 components, the proportion of energy from total fat, from saturated fat, and milligrams sodium per day, were computed using the Harvard nutrient database. The composite DASH diet accordance score (0–10) was calculated19 with further modifications20 (table e-1 on the Neurology® Web site at Neurology.org). The MedDiet score (MedDietScore)21 is based on intakes of alcohol and 10 food groups. The maximum number of points for MedDietScore is 55, where higher scores connote greater accordance. MedDiet component values (from 0 to 5) are assigned on the basis of a predefined number of servings for each point value based on the traditional Greek Mediterranean diet.21 In contrast, for the more popular Mediterranean score, the MeDi,22 point values (0 or 1) for each of the 9 components are assigned on the basis of meeting and/or exceeding the sex-specific population median of food component distribution.

Cognitive assessments.

In annual neurologic examinations, MAP participants' cognitive function was assessed with a battery of 19 cognitive tests summarized as a global measure of cognition and 5 separate summary measures including: (1) episodic memory (a composite score of the following 7 tests: logical memory [immediate], logical memory [delayed], Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease [CERAD] immediate word list recall, CERAD delayed word list recall, CERAD word list recognition, East Boston Story immediate, and East Boston Story delayed); (2) semantic memory (a composite score of 3 tests: verbal fluency from CERAD, 15-item version of the Boston Naming Test, and 15-item reading test); (3) working memory (a composite score of 3 tests: Digit Span subset Forward, Digit Span subset Backward, and Digit Ordering); (4) perceptual speed (4 tests: oral version of the Symbol Digit Modalities Test, Number Comparison, and 2 indices from the modified Stroop Neuropsychological Screening); and (5) visuospatial ability (2 tests, which include 15-item Judgment of Line Orientation, and 16-item of Standard Progressive Matrices).23 We computed composite scores of all 19 tests (global) and for each cognitive domain to minimize floor and ceiling effects and other sources of measurement error of the individual tests. Raw scores on each test were converted to z scores by using the baseline mean and SD, and then scores were averaged to form the composite measures.24

Other nondietary variables.

Other nondietary variables were acquired at the participants' baseline interviews. Age was computed from self-reported birth date and date of baseline cognitive assessment. Education was computed from self-reported years of education. An evaluation of depressive symptoms was made using the 10-item version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scale and was derived from the original 30-item version with acceptable reliability and similar factor structure to the original version.25 Presence or absence of diabetes was based on self-reported history or diabetic medication use (including insulin injections). Hypertension was defined by measured systolic/diastolic blood pressures exceeding 160/90 mm Hg or current use of antihypertensive medications at the time of FFQ completion. Presence or absence of stroke was defined on the basis of medical history and neurologic examination. A composite score ranging from 0 to 7 reflecting the frequency of participation in cognitive activities (e.g., reading newspapers) was constructed as described previously; higher scores indicate participation in more activities.26 A physical activity score reflects the sum of hours per week in 5 exercises (walking for exercise, yard work or gardening, calisthenics or general exercises, bicycling, and swimming), as adapted from the National Health Interview Survey. APOE genotyping (Agencourt Bioscience Corporation, Beverly, MA) was based on high-throughput sequencing assay.27

Statistical analyses.

Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). We used mixed-effects models to estimate the effect of accordance to the DASH and MedDiet patterns on the rates of within-person change in cognitive scores over time. The basic-adjusted model included terms for the diet pattern, age, sex, education, participation in cognitive activities, total energy intake (kcal), time, and the interaction between time and each covariate. Secondary models were also run that included the basic covariates as well as physical activity, APOE ε4 alleles, depression, and stroke. The interaction terms with time represent the effects of the variables on the rate of change in cognitive scores. The β coefficients for the diet scores represent the associations between diet scores and either baseline cognitive scores or rates of change in cognitive scores (interaction terms with time and dietary scores). A positive β coefficient for interaction terms with time and diet score reflects a decrease in the rate of decline with higher diet scores. Effect modification was examined by modeling 2- and 3-factor interaction terms among the covariates (presence or absence of APOE ε4 alleles, depression, stroke, hypertension, diabetes, as well as age and sex), diet score, and time. DASH and MedDiet scores were also modeled in tertiles with the lowest as the referent category to assess whether the influence on cognitive changes was driven by the highest scores. To determine whether DASH and MedDiet scores were related to some cognitive abilities but not others, an examination was made of their associations with separate summary measures of 5 different cognitive abilities. In an effort to ascertain whether these relations were attributable to participants who had the lowest global cognitive scores in the sample, we excluded those with the lowest scores (lowest 10% of global scores) and reran these models.

RESULTS

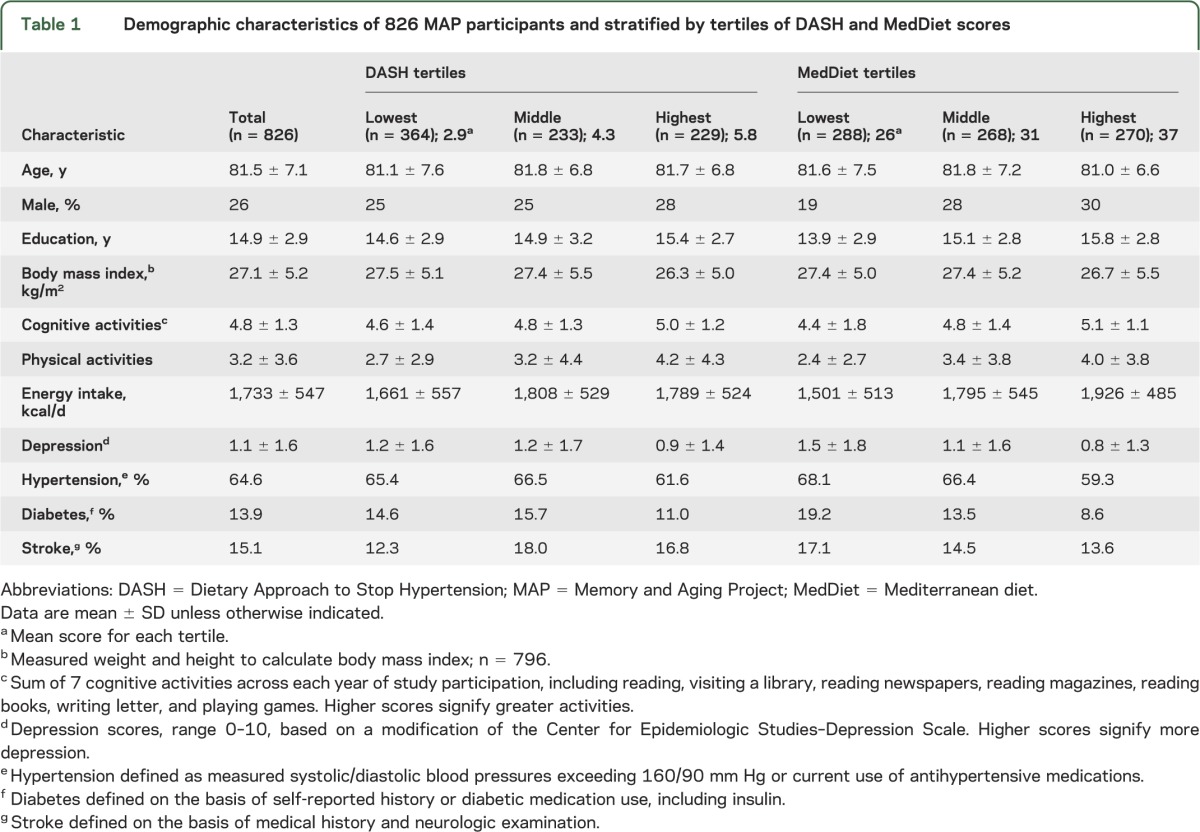

The average age of MAP participants was 81.5 ± 7.1 years with no remarkable differences in age among those categorized into DASH score or MedDietScore tertiles (table 1). Participants were mostly female with 14.9 years of education; approximately one-fifth had at least one APOE ε4 allele. Average daily energy was 1,733 ± 547 kcal with 30% ± 6% energy from total fat, 10% ± 2% from saturated fat, and 2,335 ± 822 mg sodium per day. Because annual cognitive assessments are performed, 17.4% of the sample had 2 cognitive assessments, nearly a quarter (21.5%) had 5 assessments, and 12.4% had 8. The average follow-up of MAP participants in this analysis was 4.1 years, with a range of 1 to 10 years.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of 826 MAP participants and stratified by tertiles of DASH and MedDiet scores

No one received a perfect DASH or MedDiet score. The average DASH score of participants was 4.1 ± 1.4 with a range of 1.0 to 8.5, and for MedDietScore, 31.3 ± 5.1, range, 18 to 46. DASH and MedDiet scores were correlated (r = 0.51, p < 0.0001). An assessment of food group servings and dietary estimates that constitute the basis for DASH and MedDiet scoring are shown in table e-1. For the DASH scoring, the number of grain servings was exceptionally low with only 1.3% achieving the target frequency amount of 7 servings per day. Only 35% reported consuming 4 or more servings of vegetables per day and even less. Although a large proportion of MAP participants consumed 2 or fewer daily servings of meat, fish, or poultry, relatively few met targets (limits) for intakes of saturated fat or sweets. More than half reported consuming less than 2,400 mg sodium per day. For MedDietScores, only 5.8% received a perfect score for the MedDiet vegetable component, meaning those participants had consumed more than 33 vegetable servings per week. Few met targets for potatoes (0.1%), olive oil (4.3%), or fish (0.2), although 46.4% did meet the optimal intakes of alcohol in this group.

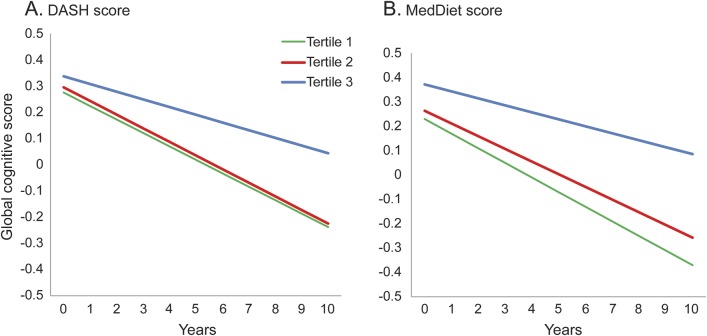

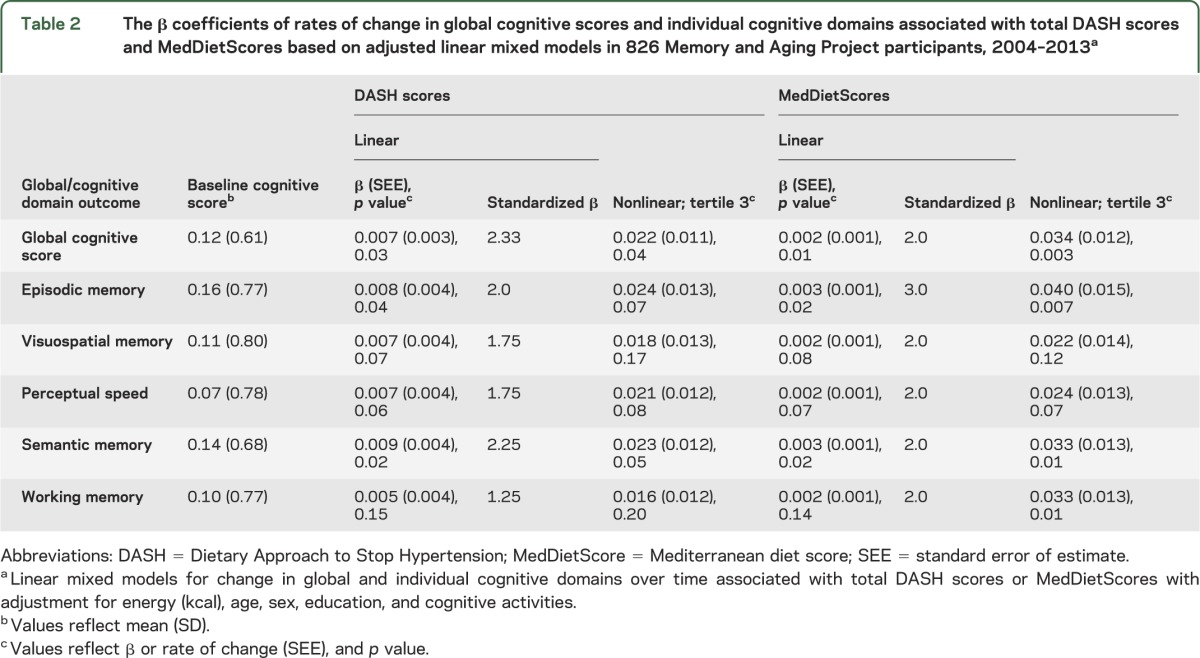

The mean global cognitive score at baseline was 0.12 (range, −3.23 to 1.60), and the overall mean change in score per year was a decline of −0.08 standardized units. As shown in table 2, there was a positive association between global cognitive scores over time and total DASH score reflecting a reduction in the rate of decline in cognitive scores. Per 1-unit-higher DASH score, the decline rate was slower by 0.007 standardized units (standard error of estimate [SEE] = 0.003, p = 0.03). Models were repeated using tertiles of the diet scores in place of the total DASH or MedDiet score. As shown in the figure, only the top tertile (DASH scores with a mean of 5.8) reduced the rates of cognitive decline (β = 0.022, SEE = 0.011, p = 0.04). Results were not changed with additional adjustment for depressive symptoms, the presence of APOE ε4 alleles, stroke, hypertension, or diabetes (table e-2). In addition, there was no evidence of effect modification by age, sex, presence of APOE ε4 alleles, stroke, hypertension, or diabetes (p values for interaction were each >0.10). Similar associations were also noted for global cognitive changes over time and the total MedDietScores; for 1-unit-higher MedDietScore, the rate of cognitive decline was slower by 0.002 standardized units (SEE = 0.001, p = 0.01). Only the upper tertile of MedDietScores was associated with rates of global cognitive change (β = 0.034, SEE = 0.012, p = 0.003). When we examined whether the associations with MedDietScores and cognitive decline differed by age, sex, presence of APOE ε4 alleles, stroke, hypertension, or diabetes, no significant interactions were found (p values for interaction were each >0.10). When total DASH scores were regressed on rates of changes in each of the cognitive domains, the scores were associated with 2 of the 5 domains (episodic memory and semantic memory) (table 2). For MedDietScores, the rates of change in episodic memory and in semantic memory were also slower. Standardized regression coefficients are also provided in table 2. Based on a comparison of standardized β coefficients from the basic-adjusted models, DASH scores (2.33) were as predictive of cognitive decline as those of MedDietScores (2.00) in this cohort. DASH scores in the top tertile were significantly associated with reduced rates of change for not only global scores but also semantic memory. MedDietScores in the upper tertile were associated with slower decline rates in episodic, semantic, and working memory domains.

Table 2.

The β coefficients of rates of change in global cognitive scores and individual cognitive domains associated with total DASH scores and MedDietScores based on adjusted linear mixed models in 826 Memory and Aging Project participants, 2004–2013a

Figure. Cognitive change over time by DASH scores and MedDietScores.

Changes in global cognitive scores over time as a function of (A) DASH score tertiles (left) and (B) MedDietScore tertiles (right). All mixed models included covariable adjustments by age, sex, education, energy, and late-life cognitive activities. Change rates in global cognitive scores of Memory and Aging Project participants were significantly associated in the highest tertiles of either score—DASH (β = 0.022, SEE = 0.011, p = 0.04) or MedDiet (β = 0.034, SEE = 0.012, p = 0.003)—but not for those whose DASH scores (β = −0.001, SEE = 0.010, p = 0.95) or MedDietScores (β = 0.01, SEE = 0.011, p = 0.37) were in the second tertiles. DASH = Dietary Approach to Stop Hypertension; MedDiet = Mediterranean diet; MedDietScore = Mediterranean diet score; SEE = standard error of estimate.

When we repeated analyses excluding participants whose baseline global cognitive scores were in the bottom 10% of the distribution, the multiple adjusted estimates for total DASH score changed very little (β = 0.01, SEE = 0.003, p = 0.01, n = 741). When such analyses were run for MedDietScores, the estimates also were minimally affected (β = 0.002, SEE = 0.001, p = 0.01). Additional sensitivity analyses were run excluding those persons with possible dementia at baseline; there were minimal changes in the cognitive rates of change.

DISCUSSION

In the MAP community cohort of older persons, accordance to both the DASH and MedDiet dietary patterns was associated with slower rates of cognitive decline. For a 1-unit-higher DASH score, rates of cognitive decline were 0.007 standardized units slower or equivalent to at least 4.4 years younger age. These findings were not wholly unexpected because many of the food components that constitute the selected diet scores are those we have previously observed to be related to cognitive change,8,28–30 as have other groups.31 Similar components of DASH and Mediterranean-style diet scores among Cache County cohort participants were also associated with cognitive decline over an 11-year period; these included 3 DASH components (whole grains, vegetables, and nuts plus legumes) and 2 Mediterranean components (legumes and vegetables).9 In the Women's Health Study participants, investigators14 observed that higher monounsaturated-to-saturated ratios were related to more favorable cognitive trajectories, although total scores (the alternate MeDi) were not associated with cognitive change. The present study findings also confirm those of the 4-month randomized trial of a DASH diet intervention with or without a weight management program vs usual care in middle-aged, hypertensive adults; executive memory and learning functions improved in the DASH plus weight group while psychomotor function improved in both DASH interventions regardless of weight strategies.15 It is intriguing to note that in this older, largely hypertensive MAP population, accordance to either diet pattern—not an active dietary intervention—was associated with improvements in cognitive domains over a period of 4 years. Similar findings from studies with different research designs and duration suggest that the cognitive effects from this dietary pattern may be rapid. There are 2 other reports from observational cohorts of older persons in the United States that support the associations of Mediterranean-style diet scores with cognitive decline.8,9

DASH scores (mean of 4.1) observed in the present study are similar to those of other American adult population samples. Others reported DASH scores ranging from 3.6 to 3.9 among Exercise and Intervention for Cardiovascular Health Trial participants20; this group used a DASH scoring system similar to that used in the present study. In a much larger cohort—more than 20,993 Iowa Women's Health Study participants in 1986—DASH scores averaged 4.2 with a considerable range from 0.5 to 10; no one had a perfect accordance score of 11.19 Examination of reported MedDietScores of participants in several US cohorts is more tenuous, because of different scoring paradigms and different analytic approaches.

The mechanism(s) underlying the associations between these 2 dietary patterns on cognition or cognitive decline is mostly unknown but may involve inflammatory processes. Inflammation is generally believed to be the key process contributing to cerebrovascular pathology, stroke, and heart disease. In a 24-year follow-up of participants in the Nurses' Health Study, DASH scores were associated with reduced risk of stroke (p < 0.002 for trend), and reduced levels of inflammatory markers.32 Similarly, based on the findings from a recent clinical trial of 2 MedDiet interventions against a control low-fat treatment, the MedDiets over a 5-year period reduced cardiovascular events—in particular, incident stroke.3 Reduced levels of circulating inflammatory markers and improved endothelial function have been shown when participants adopt this dietary pattern.33 Alternatively, antioxidant protection afforded by many of the DASH and Mediterranean food components (vegetables, nuts, legumes) that are enriched in tocopherols, omega-3 fatty acids, thiamin, lutein, other carotenoids, vitamin K, folate, and certain polyphenols may be responsible for the relations to cognitive decline.34–36 Perhaps the presence of such foods in the gut may favor certain bacteria that, in turn, facilitate maintenance of factors that are neuroprotective.37 It is possible that these foods may influence β-amyloid or tau metabolism; evidence for these mechanisms are largely from animal studies38,39 and require further assessment and confirmation. Moreover, the literature is even more limited for the influence of these dietary patterns on individual cognitive domains. Many groups use different series of cognitive tests to examine cognitive domains. There is considerable overlap in tests selected and how these domains are described as discussed recently.40

Strengths of the present study include the prospective design, a community sample, use of a well-validated dietary questionnaire, use of DASH and MedDiet scoring tools that have been applied to other population samples, and use of multiple tests to measure cognitive function longitudinally. Moreover, the present analyses included adjustment for many confounders. Some of the limitations include relatively few items reflecting nonrefined grains (only 3 items), few fish items (particularly regarding preparation), and less specific information on type of olive oils on the MAP FFQ. Because of the observational study design, we must caution against a causal interpretation of findings. Furthermore, this cohort may not be representative of the diverse older population in the United States.

These findings attest to the need for more research to determine whether a food-based approach can attenuate neurocognitive decline in older populations at risk of Alzheimer disease or vascular cognitive impairment. A food-based clinical trial for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease has been fruitful (i.e., PREDIMED3). The need for similar efforts is critical in the face of the growing number of aging adults who are at risk of dementias.

Supplementary Material

GLOSSARY

- CERAD

Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease

- DASH

Dietary Approach to Stop Hypertension

- FFQ

food frequency questionnaire

- MAP

Memory and Aging Project

- MedDiet

Mediterranean diet

- MedDietScore

Mediterranean diet score

- SEE

standard error of estimate

Footnotes

Supplemental data at Neurology.org

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Dr. Tangney: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Ms. Li and Dr. Wang: analysis and interpretation of data. Dr. Barnes: study concept and design, interpretation of data, and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; other contribution: study supervising or coordination. Dr. Schneider: study concept and design, interpretation of data, and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; other contribution: acquisition of data. Dr. Bennett: study concept and design, interpretation of data, and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; other contribution: study supervising or coordination. Dr. Morris: study concept and design, interpretation of data, and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

STUDY FUNDING

Supported by the National Institute on Aging (R01AG031553 and R01AG17917).

DISCLOSURE

C. Tangney has no relevant disclosures. She is paid for her contributions to 4 chapters in UpToDate. She serves on the editorial board of Journal of Nutrition in Gerontology and Geriatrics, American Journal of Health Behaviors, and Journal of Neurology & Translational Neuroscience, and is supported by grants from the NIH AG031553, R21ES021290, R01HL117804, D09HP25915, and R03 CA178843-01 (consultant). H. Li and Y. Wang report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. L. Barnes serves as an editorial board member of the Journal of Aging and Health and is funded by NIH grants R01AG022018, P30AG010161, R13 AG044140 (consultant), and P20MD006886. J. Schneider has served on an advisory board for Genentech and GE Healthcare and was a consultant for AVID Pharmaceuticals, and is funded by NIH grants (R01AG042210, R01AG039478, R01AG022018, P30AG010161, R01AG017917, R01AG015819, R01AG036042, R01AG036836, R01AG046152). D. Bennett has no relevant disclosures. He is supported by grants from the NIH (R01AG017917, P30AG010161, R01AG015819, U01AG46152, R01AG036042), and Nutricia, Inc. Dr. Bennett serves on the editorial board of Neurology®, Current Alzheimer's Research, and Neuroepidemiology; has received honoraria for nonindustry-sponsored lectures; serves on the adjudication committee for Takeda, Inc., and has served as a consultant to Nutricia, Inc., Eli Lilly, Inc., Gerson Lehrman Group, Double Helix, and Enzymotec, Ltd. M. Morris received funding from the NIH (AG031553 and R21ES021290) to investigate dietary relations to neurodegenerative diseases and serves as paid consultant to Nutrispective (an informational Web site on nutrition and disease) and Abbott Nutrition. Dr. Morris serves on the editorial board of the Journal on Nutrition Health and Aging and Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Appel LJ, Brands MW, Daniels SR, et al. Dietary approaches to prevent and treat hypertension: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertension 2006;47:296–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ard JD, Grambow SC, Liu D, Slentz CA, Kraus WE, Svetkey LP. The effect of the PREMIER interventions on insulin sensitivity. Diabetes Care 2004;27:340–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvado J, et al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1279–1290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bullo M, Garcia-Aloy M, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, et al. Association between a healthy lifestyle and general obesity and abdominal obesity in an elderly population at high cardiovascular risk. Prev Med 2011;53:155–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saczynski JS, Jonsdottir MK, Garcia ME, et al. Cognitive impairment: an increasingly important complication of type 2 diabetes: the age, gene/environment susceptibility—Reykjavik Study. Am J Epidemiol 2008;168:1132–1139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kivipelto M, Ngandu T, Fratiglioni L, et al. Obesity and vascular risk factors at midlife and the risk of dementia and Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 2005;62:1556–1560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gorelick PB. Role of inflammation in cognitive impairment: results of observational epidemiological studies and clinical trials. Ann NY Acad Sci 2010;1207:155–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tangney CC, Kwasny MJ, Li H, Wilson RS, Evans DA, Morris MC. Adherence to a Mediterranean-type dietary pattern and cognitive decline in a community population. Am J Clin Nutr 2011;93:601–607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wengreen H, Munger RG, Cutler A, et al. Prospective study of Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension- and Mediterranean-style dietary patterns and age-related cognitive change: the Cache County Study on Memory, Health and Aging. Am J Clin Nutr 2013;98:1272–1281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scarmeas N, Stern Y, Tang MX, Mayeux R, Luchsinger JA. Mediterranean diet and risk for Alzheimer's disease. Ann Neurol 2006;59:912–921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cherbuin N, Anstey KJ. The Mediterranean diet is not related to cognitive change in a large prospective investigation: the PATH Through Life Study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2012;20:635–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vercambre M, Grodstein F, Berr C, Kang JH. Mediterranean diet and cognitive decline in women with cardiovascular disease or risk factors. J Acad Nutr Diet 2012;112:816–823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Samieri C, Okereke OI, E Devore E, Grodstein F. Long-term adherence to the Mediterranean diet is associated with overall cognitive status, but not cognitive decline, in women. J Nutr 2013;143:493–499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Samieri C, Grodstein F, Rosner BA, et al. Mediterranean diet and cognitive function in older age. Epidemiology 2013;24:490–499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith PJ, Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, et al. Effects of the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension diet, exercise, and caloric restriction on neurocognition in overweight adults with high blood pressure. Hypertension 2010;55:1331–1338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Buchman AS, Barnes LL, Boyle PA, Wilson RS. Overview and findings from the Rush Memory and Aging Project. Curr Alzheimer Res 2012;9:646–663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morris MC, Tangney CC, Bienias JL, Evans DA, Wilson RS. Validity and reproducibility of a food frequency questionnaire by cognition in an older biracial sample. Am J Epidemiol 2003;158:1213–1217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tangney CC, Bienias JL, Evans DA, Morris MC. Reasonable estimates of serum vitamin E, vitamin C, and beta-cryptoxanthin are obtained with a food frequency questionnaire in older black and white adults. J Nutr 2004;134:927–934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Folsom AR, Parker ED, Harnack LJ. Degree of concordance with DASH diet guidelines and incidence of hypertension and fatal cardiovascular disease. Am J Hypertens 2007;20:225–232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Epstein DE, Sherwood A, Smith PJ, et al. Determinants and consequences of adherence to the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension diet in African-American and white adults with high blood pressure: results from the ENCORE trial. J Acad Nutr Diet 2012;112:1763–1773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Panagiotakos DB, Pitsavos C, Arvaniti F, Stefanadis C. Adherence to the Mediterranean food pattern predicts the prevalence of hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes and obesity, among healthy adults: the accuracy of the MedDietScore. Prev Med 2007;44:335–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trichopoulou A, Kouris-Balzo A, Wahlqvist ML, et al. Diet and overall survival in elderly people. BMJ 1995;311:1457–1460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aggarwal NT, Wilson RS, Beck TL, Bienias JL, Bennett DA. Mild cognitive impairment in different functional domains and incident Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2005;76:1479–1484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilson RS, Beckett LA, Barnes LL, et al. Individual differences in rates of change in cognitive abilities of older persons. Psychol Aging 2002;17:179–193 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kohout FJ, Berkman LF, Evans DA, Cornoni-Huntley J. Two shorter forms of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression) depression symptoms index. J Aging Health 1993;5:179–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buchman AS, Boyle PA, Wilson RD, Fleischman DA, Leurgans S, Bennett DA. Association between late-life social activity and motor decline in older adults. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:1139–1146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buchman AS, Boyle PA, Wilson RS, Beck TL, Kelly JF, Bennett DA. Apolipoprotein E e4 allele is associated with more rapid motor decline in older persons. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2009;23:63–69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morris MC, Evans DA, Tangney CC, Bienias JL, Wilson RS. Associations of vegetable and fruit consumption with age-related cognitive change. Neurology 2006;67:1370–1376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morris MC, Evans DA, Tangney CC, Bienias JL, Wilson RS. Fish consumption and cognitive decline with age in a large community study. Arch Neurol 2005;62:1849–1853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morris MC, Evans DA, Bienias JL, et al. Dietary fats and the risk of incident Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 2003;60:194–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kang JH, Ascherio A, Grodstein F. Fruit and vegetable consumption and cognitive decline in aging women. Ann Neurol 2005;57:713–720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fung TT, Chiuve SE, McCullough ML, Rexrode KM, Logroscino G, Hu FB. Adherence to a DASH-style diet and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke in women. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:713–720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mena MP, Sacanella E, Vazquez-Agell M, et al. Inhibition of circulating immune cell activation: a molecular antiinflammatory effect of the Mediterranean diet. Am J Clin Nutr 2009;89:248–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kastorini CM, Milionis HJ, Esposito K, Giugliano D, Goudevenos JA, Panagiotakos DB. The effect of Mediterranean diet on metabolic syndrome and its components: a meta-analysis of 50 studies and 534,906 individuals. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;57:1299–1313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morris MC, Evans DA, Bienias JL, et al. Dietary intake of antioxidant nutrients and the risk of incident Alzheimer disease in a biracial community study. JAMA 2002;287:3230–3237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morris MC, Evans DA, Bienias JL, et al. Dietary folate and vitamin B12 intake and cognitive decline among community-dwelling older persons. Arch Neurol 2005;62:641–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Daulatzai MA. Obesity and gut's dysbiosis promote neuroinflammation, cognitive impairment, and vulnerability to Alzheimer's disease: new directions and therapeutic implications. J Mol Genet Med 2014;S1:5 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fernández-Fernández L, Comes G, Bolea I, et al. LMN diet, rich in polyphenols and polyunsaturated fatty acids, improves mouse cognitive decline associated with aging and Alzheimer's disease. Behav Brain Res 2012;228:261–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grossi C, Rigacci S, Ambrosini S, et al. The polyphenol oleuropein aglycone protects TgCRND8 mice against Aβ plaque pathology. PLoS One 2013;8:e71702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.de Jager CA, Dye L, de Bruin EA, et al. Cognitive function: criteria for validation and selection of cognitive tests for investigating the effects of foods and nutrients. Nutr Rev 2014;72:162–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.