The core principle of implementing healthy behavior change is making the healthy choice the easy choice. Putting this motto into practice requires removal of barriers to live a healthy lifestyle. It is important to look at the bigger picture when helping patients reach optimal health, looking closely at exercise levels and home life. Environmental factors cause strain and present challenges also. The Care Management Institute and Kaiser Permanente are changing default behaviors so optimal lifestyles become the norm, rather than the exception.

Abstract

The core principle of implementing healthy behavior change is making the healthy choice the easy choice. Putting this motto into practice requires us to remove the barriers that individuals face when trying to live a healthy lifestyle. It is important to look at the bigger picture when helping our patients reach optimal health, looking closely at exercise levels and home life. Environmental factors can cause strain and present challenges for people trying to develop and maintain good health. At the Care Management Institute and at Kaiser Permanente, we are making strides to change default behaviors so optimal lifestyles become the norm, rather than the exception.

The Healthy Choice

At the Care Management Institute, we pride ourselves on the work we do to “make the right thing easy to do.” One of the key tenets of putting this motto into practice is removing the barriers that make it difficult for us as an organization to initiate change—and a big part of that is looking at the whole picture. We’re not just trying to solve problems; we’re trying to identify the sources of the problems so that we can make necessary adjustments early on, and with greater success.

The same principles apply on an individual level. As a family practice physician, when I am sitting across from patients with high blood pressure, there are a number of questions I must ask. Their electronic health records (EHRs) prompt me with certain information about their family histories and body mass indexes and even remind me to measure exercise as a vital sign. However, there are so many more elements that I want to examine, beyond what the medical record can show me. To be successful in making my patients their healthiest selves, I need to have effective and constructive conversations before providing any advice.

Behaviors and Social Practice

Our EHR system doesn’t necessarily prompt us to look at behaviors and social factors that may be obstacles to achieving optimal health. For my patients with hypertension, I’m going to care about aspects of their daily lives that prevent them from exercising healthier practices. I care about their environment—where they live, what they eat during the day, and how many hours they spend sitting each day. I care about whether there’s a grocery store in their neighborhoods where they can access fresh fruits and vegetables. The things I care about when I’m meeting with my patients look a lot different from the list of questions that pops up in the EHR. Yet these factors are equally, if not more, important than anything else when I’m looking at the causes of my patients’ medical conditions.

A Positive Conversation

Once I have a better understanding of the total picture of my patients, there is a second set of considerations I must examine. Will my patients make the lifestyle and behavior changes needed to positively affect their health? Yes, I can tell them to eat better and exercise more, but if they work two jobs and don’t have access to a grocery store in their neighborhoods, they’re going to have a tough time with this. At this point, I might think back to the motivational interviewing training I received and think about how to frame the conversation with patients in the most constructive way. Motivational interviewing involves four stages of dialogue to help orient patients toward success with their change-related goals using support, advice, affirmation, and empathetic conversation. These stages include engaging with patients to help build rapport, focusing patients on the changes they want to make while offering advice and support, evoking the tools and desires they possess within them to effect change, and planning to implement the goals and next steps patients identified through the encounter.1 Supporting my patients’ awareness about their current behavior patterns, helping them become aware of the skills they already have, and respecting any initial resistance will be crucial to conducting a positive conversation.

Healthy Lifestyle Changes

Traditionally, the ability to achieve total good health has been dependent on an individual’s willingness to implement change in his or her everyday life. Behavioral design ultimately helps people find useful tools and tactics for making healthy lifestyle changes. It also helps determine how able and ready a person is to make a change, and what triggers are most likely to instigate that change. At times, if I’m unable to motivate my patients to change, I might need to enlist the expertise of others on my team and provide a referral. What kind of resources or outside referrals will be beneficial in helping my patients accomplish their goals? I may need to go beyond the exam room and look to what the community can offer. There may be diet- and exercise-tracking apps, free nutritional and wellness counseling, cooking classes, sports clubs, and even community or church groups that could help my patients to make positive lifestyle changes once they leave my exam room.

For individuals to sustain healthy lifestyle changes, we must make the healthy choice the easy choice. Something as simple as having well-lit and well-maintained stairwells in office buildings, having weekly walking meetings, or including healthy food choices at lunchtime meetings can make the difference for someone to implement healthy habits.

Behavior Change Conversations

However, to sustain healthy lifestyle changes, we must address them not only in communities but also in clinical settings. Clinicians and physicians are a crucial element to bridging the gap between individuals knowing what needs to change and actually implementing those lifestyle changes. Physicians are in a position to help educate patients about the importance of healthy behavior change and to guide them to resources that may aid them in living healthier lives. Training in motivational interviewing is one useful tool that can aid clinicians to have productive conversations about behavior change with their patients. One resource used in Northern California is the Motivational Interviewing Toolkit: www.kphealtheducation.org; however, there are many ways to approach behavior change conversations with patients. Discussions about behavior change help individuals understand healthy living in the context of preexisting goals they may have and to view overall health as a community issue, rather than as a medical condition.

Unhealthy Habits

The prevalent and growing obesity epidemic in the US initially stemmed, in part, from negative systematic change. New communities today are frequently designed around unhealthy habits: Suburban housing developments require people to drive to everyday destinations, and fast food restaurants make unhealthy food the most convenient option. This has created an unmet need for systematic changes in the opposite direction—changes that will help us to climb out of the unhealthy routine and to redesign for optimal default behaviors. Since 1994, there has been a dramatic increase in obesity in the US.2 According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 35.7% of US adults and approximately 17%—or 12.5 million—of children and adolescents aged 2 to 19 years are obese.3 Obesity can lead to more serious chronic diseases such as heart disease and diabetes. Obesity is a problem that begins by affecting communities and eventually spreads to a national level. Awareness campaigns such as HBO’s The Weight of the Nation (developed in partnership with Kaiser Permanente) are attempting to reach individuals in their communities and warn them of the severe and adverse effects of being overweight or obese.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also reports, through the Diabetes Prevention Program national study, that intensive lifestyle change and intervention can prevent diabetes caused by obesity. The multicenter clinical research study aimed to discover whether modest (5% to 7%) weight loss through dietary changes and increased physical activity (150 minutes/week) could prevent or delay the onset of type 2 diabetes in study participants. The Diabetes Prevention Program ultimately found that participants who lost a modest amount of weight through dietary changes and increased physical activity sharply reduced their chances of developing diabetes.4

Since Kaiser Permanente’s (KP’s) inception, the importance of prevention has always influenced our work and our values, and we have remained on the leading edge. Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) data show that KP’s Georgia and Southern California Regions are ranked first and second, respectively, in the nation for adult body mass index screening, with other KP Regions not far behind.5

Exercise as Vital Sign

Last year, we determined the validity of asking our patients how many minutes per week they exercise and recording this number as a vital sign. This was a progressive step toward achieving optimal behavior design in a clinical setting, and toward achieving total good health. It was also our first foray into creating a clinical measure that determines how a patient’s lifestyle can directly translate into the prevention of the leading causes of death in our country. According to a KP study published in the journal Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, establishing a systematic method for recording patients’ physical activity in their EHRs ultimately helps clinicians better treat and counsel patients about their lifestyles.6

Healthy Habits

Although recognizing exercise as a vital sign is a step in the right direction for healthy behavior change, there is still work to be done. Addressing exercise as a vital sign certainly opens the door to a larger conversation about healthy habits, but what keeps us from fully engaging with our patients is the fact that we don’t completely understand how to measure environmental determinants, or how to talk to patients about them. We must find a way to effectively relate to each patient individually to ascertain how they can fit healthy habits into their everyday routines. First, we must determine what changes each individual is willing to make. Then we must simplify these changes and guide patients through how to monitor their actions against an overall goal. We also must be aware that some patients may be initially resistant to change. Instead of challenging this resistance, we should respect it and encourage patients to drive toward their own goal-oriented solutions.

Karen J Coleman, PhD, research scientist at the KP Southern California Department of Research and Evaluation and lead author of the study examining exercise as a vital sign, stated, “Given that health care providers have contact with the majority of Americans, they have a unique opportunity to encourage physical activity among their patients through an assessment and brief counseling.”7 She added, “embedding questions about physical activity in the electronic medical record provides an opportunity to counsel millions of patients during routine medical care regarding the importance of physical activity for health.” 7

Prescribing Success

To focus on total health at a personal level with individuals, it is important to enlist the clinical community to help us prescribe success, rather than just prescribing medical interventions. A crucial question to ask ourselves is, “As a physician, am I equipped to prescribe success for my patient?” Although we, as physicians, have a role to play in the continued health of our patients, barriers to achieving this goal are inevitable.

We must incorporate behavior change as part of the total health framework that physicians advocate and model for their patients and that individuals implement in their lives and communities. As an integrated health care system, we should aim to change the course of how to approach and encourage healthier behaviors to prevent disease, as well as consider what fundamental elements encourage people to change their behavior, and sustain that change, understanding that personal behavior is a major contributor to overall health.

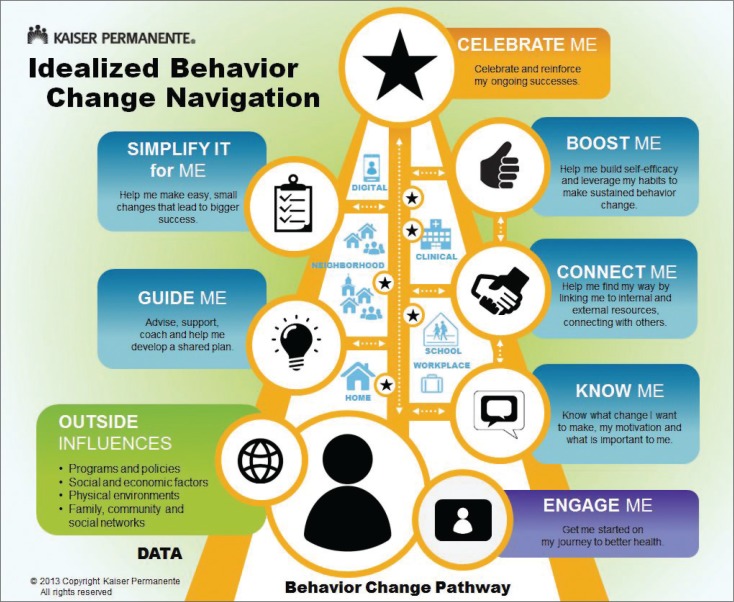

As the behavior change pyramid suggests, it is crucial to bridge the gap between the medical model of the physician’s office and the individual’s experience in the community (Figure 1). Because healthy behavior change begins at home, it’s important for primary care physicians to connect and engage patients on a personal level and to determine what matters the most to patients and what changes they are willing to make, so we can ultimately set them up for success in sustaining those changes. It’s equally important to reinforce ongoing successes once individuals do implement healthy habits in their everyday lives. Again, personal behavior is a major contributor to overall health.

Figure 1.

The Behavior Change Pathway.

Reprinted with permission from Kaiser Permanente.

One way to engage individuals in improving their health is to show them how healthy behavior changes can be major contributors to preventing or delaying the onset of disease or personal injury. Health care leaders are increasingly recognizing healthy behaviors as factors in the improvement of overall health. For example, studies indicate that there is a clear link between good emotional health and healthier behaviors.

In 1994, KP created the bone density screening program for osteoporosis prevention in Southern California. As part of this innovative initiative, we identified members with a higher risk of osteoporosis, and we performed bone density screenings on this population. We were also able to recommend calcium supplements, exercise, and other lifestyle changes that could help prevent fractures later on. By 2002, the fully integrated Healthy Bones program was in place at all Medical Centers in the organization’s Southern California Region. Since then, the Healthy Bones program has reduced the number of fragility fractures among Southern California members by 15%. The program has expanded to all KP Regions.8

This is just one example of how early intervention combined with lifestyle and behavior change successfully altered the course of health history for a significant number of our members with the potential for bone disease. With this example in mind, it seems logical that, as a delivery system, we should consider our role in addressing intensive lifestyle change to prevent other diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and lung disease.

Mood and Sleep

Increased physical activity can directly and positively affect mood in individuals who experience depression. Physical activity has been examined as an adjunctive treatment strategy for major depressive disorder.9 This type of evidence can help patients see the positive effects of physical activity on not only their weight and blood pressure, but also on more serious emotional issues, such as depression and anxiety.

Similarly, lack of sleep has been directly linked to obesity. According to a new University of California, Berkeley study, something as simple as getting a good night’s sleep could be a habit that directly affects an individual’s weight.10 The study found that not only did sleep-deprived individuals crave unhealthy choices, but their brain behaved differently as well. Ultimately, the brain impairment that occurs when sleep deprivation occurs leads to unhealthy food choices and can eventually cause obesity. However, on the other side of the coin, this means that getting enough sleep is a factor that can help promote weight loss in overweight patients, as long as we can share relevant information with them and engage them to implement this healthy change.10,11

Advertising Unhealthy Habits

Some environmental factors such as television advertising are beyond individual control, making it even more difficult to break unhealthy habits. Furthermore, advertisements also become a contributing factor to poor eating choices, creating a vicious cycle of bad behavior that is difficult to break. Advertisements are a telling example of environmental factors that individuals face in their daily lives that they cannot change or control. Television marketing increased by 8.3% for children ages 2 to 5 years and by 4.7% for children ages 6 to 11 years from 2009 to 2011, reversing declines in previous years, according to Lisa Powell, PhD, of the University of Illinois at Chicago School of Public Health, and colleagues.12 In addition, by examining television analytics data, the researchers found that teens’ exposure to food ads increased by 9.3%.

“Teens’ exposure to food-related TV advertising has continued to increase steadily since 2003, reaching almost 16 ads per day in 2011,” the authors wrote in the American Journal of Preventative Medicine.12 Challenges such as the advertising of unhealthy habits are an inherent problem for individual communities—which makes it more crucial for physicians to connect with individuals, better understand where they come from and the challenges they face, and effectively motivate them to change their lifestyles.

Invest in People in Community

In the end, for the medical community, including KP, to be successful in helping individuals implement healthy behavior change, it is crucial to approach prevention in a different way. To ultimately produce good health, we must make investments in the personal lives of our patients —understanding the communities they live in and what intersection is needed between the clinical system and changes that are easily supported by communities. As a health care system, we know that there is no more important relationship than the one between physician and patient. We have reached a point where we have an opportunity to help the primary care system prescribe success among individuals, empowering them to restore and maintain healthy lifestyles, and we have tools available to help us guide the necessary conversations to effect change. Recognizing exercise as a vital sign is one step forward in this process, and we will continue to engage physicians and patients to ultimately change the way healthy behavior change is approached and perceived.

Acknowledgments

Leslie E Parker, ELS, provided editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

The author(s) have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Helping people change. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Guildford Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fryar CD, Carroll MD, Ogden CL. NCHS health e-stat: Prevalence of overweight, obesity, and extreme obesity among adults: United States, trends 1960–1962 through 2009–2010 [Internet] Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2012. Sep 13, [cited 2014 Jul 28]. Available from: www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/obesity_adult_09_10/obesity_adult_09_10.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity in the United States, 2009–2010. NCHS Data Brief No. 82 [Internet] Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2012. Jan, [cited 2014 Jun 2]. Available from: www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db82.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knowler WC1, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al. Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group Reduction in the incidence of Type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002 Feb 7;346(6):393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.2013 Reports (2012 Performance Year) HEDIS [Internet] Washington, DC: National Committee for Quality Assurance; c2012. [last reviewed 2014 Apr 2; cited 2014 Jun 2]. Available from: http://store.ncqa.org/index.php/performance-measurement.html. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coleman KJ, Ngor E, Reynolds K, et al. Initial validation of an exercise “vital sign” in electronic medical records. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012 Nov;44(11):2071–6. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182630ec1. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182630ec1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaiser Permanente study finds efforts to establish exercise as a vital sign prove valid [press release; Internet] Oakland, CA: Kaiser Permanente; 2012. Oct 17, [cited 2014 Jul 28]. Available from: http://share.kaiserpermanente.org/article/kaiser-permanente-study-finds-efforts-to-establish-exercise-as-a-vital-sign-prove-valid/. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bone health: a lifelong challenge [press release; Internet] Pasadena, CA: Kaiser Permanente; 2013. May 2, [cited 2014 Jun 2]. Available from: http://xnet.kp.org/newscenter/pressreleases/scal/2013/050213-osteoporosis-month.html. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaiser Permanente Care Management Institute . Diagnosis and treatment of depression in adults: 2012 clinical practice guideline [Internet] Rockville, MD: National Guideline Clearinghouse, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2012. Jun, [cited 2014 Jun 2]. Available from: www.guideline.gov/content.aspx?id=39432. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greer SM, Goldstein AN, Walker MP. The impact of sleep deprivation on food desire in the human brain. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2259. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3259. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anwar Y. Sleep deprivation linked to junk food cravings [Internet] Berkeley, CA: UC Berkeley News Center; 2013. Aug 6, Available from: http://newscenter.berkeley.edu/2013/08/06/poor-sleep-junk-food/. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Powell LM, Harris JL, Fox T. Food marketing expenditures aimed at youth: Putting the numbers in context. Am J Prev Med. 2013 Oct;45(4):453–61. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.06.003. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]