Abstract

Purpose of the review:

Although conjunctival goblet cells are a major cell type in ocular mucosa, their responses during ocular allergy are largely unexplored. This review summarizes recent findings that provide key insights into mechanisms by which their function and survival is altered during chronic inflammatory responses including ocular allergy.

Recent findings:

Conjunctiva represents a major component of the ocular mucosa that harbors specialized lymphoid tissue. Exposure of mucin secreting goblet cells to allergic and inflammatory mediators released by local innate and adaptive immune cells modulates proliferation, secretory function and cell survival. Allergic mediators like histamine, leukotrienes and prostaglandins directly stimulate goblet cell mucin secretion and consistently increase goblet cell proliferation. Goblet cell mucin secretion is also detectable in a murine model of allergic conjunctivitis. Additionally primary goblet cell cultures allow evaluation of various inflammatory cytokines with respect to changes in goblet cell mucin secretion, proliferation and apoptosis. These findings in combination with pre-clinical mouse models help understand goblet cell responses and their modulation during chronic inflammatory diseases including ocular allergy.

Summary:

Recent findings related to conjunctival goblet cells provide the basis for novel therapeutic approaches, including modulation of goblet cell mucin production, to improve treatment of ocular allergies.

Keywords: goblet cell, MUC5AC, histamine, cytokine, ocular allergy

Introduction

Ocular allergy, a type of chronic inflammation, is a complex disease involving multiple target tissues whose reactions are coordinated in response to allergens. The allergic stimulus, such as pollen in seasonal allergic conjunctivitis, interacts first with the corneal and conjunctival epithelial cells. The stimulus subsequently crosses the epithelium into the stroma where activation of immune cells including mast cells, eosinophils, dendritic cells, T cells and macrophages occurs. The responses of the different activated cells both in the epithelium and stroma contribute to the final symptomatic responses of ocular chemosis, conjunctival injection, tear production, and lid swelling. In severe types of allergy corneal damage can also occur.

Conjunctiva is a component of ocular mucosal surface that provides a barrier against the external environment. Similar to other mucosal surfaces the ocular surface is persistently exposed to allergens and commensal bacteria that pose a risk of inflammation and infection. The specialized epithelial cells, the stratified squamous and goblet cells, as well as conjunctival immune cells form a barrier that segregates host tissue from environmental factors. Both epithelial cells and immune cells together respond to external stimuli and provide protection by coordinating appropriate immune responses.

A major unexplored area in ocular allergy to be addressed by the present review is the response of a major cell type in the conjunctival epithelium, the goblet cells, to inflammatory and allergic mediators. We highlight research demonstrating that conjunctival goblet cells are a direct target of cytokines and chemokines produced during chronic inflammatory and allergic responses and that these cells respond by increasing production of the large gel forming mucin MUC5AC that functions to protect the ocular surface and remove allergens or other inflammatory stimuli from the tear film. Mucin produced by the goblet cells and secreted into the tears would be an additional symptom altered in chronic inflammation and allergic conjunctivitis contributing to the pathology.

Structure and Function of Conjunctival Goblet Cells

The conjunctiva consists of two major cell types, goblet cells and stratified squamous cells. Goblet cells occur singly or in clusters and are surrounded by stratified squamous cells. To date these two cell types differ in the types of mucins present and released into the tear film. Stratified squamous cell synthesize the membrane spanning mucins MUC1, MUC4, and MUC16 that are trafficked to the plasma membranes [1]. The mucin MUC4 predominates in the conjunctival stratified squamous cells [2]. In contrast to stratified squamous cells, goblet cells synthesize and secrete a large, gel forming mucin, the high molecular weight mucin MUC5AC. MUC5AC is secreted into the tear film where it is the scaffold forming the mucous layer that overspreads the glycocalyx and the underlying epithelium. Experimental evidence shows that this layer is a gel [3]. MUC5AC can trap ocular allergens including pollen and other airborne pathogens and remove them from the surface of the eye transporting them into the lacrimal drainage system. MUC5AC is very protective for the ocular surface as chronic inflammatory diseases in which goblet cells are depleted show corneal and conjunctival damage [4, 5].

Conjunctival Immune Cells

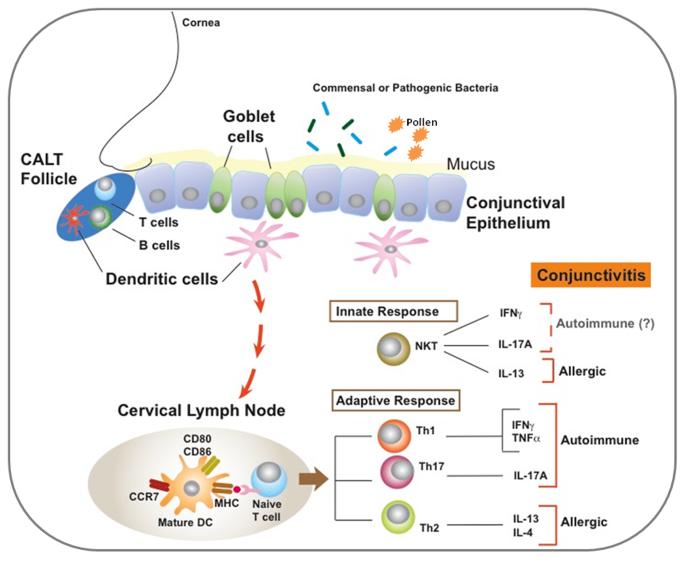

Along with antimicrobial peptides in the tears, innate cells within the conjunctiva like macrophages, mast cells, neutrophils and NKT cells afford protection by responding to allergens or microbes. Moreover adaptive immune cells like T and B lymphocytes are present in the conjunctiva either diffusely distributed through epithelial or stromal layers or in loosely organized follicular structures, together forming Conjunctiva Associated Lymphoid Tissue (CALT). The presence of such CALT has been reported in both rodents and humans [6-8]. While CALT is a normal and non-inflammatory component of the ocular surface in human conjunctiva, in mice CALT is detected in response to antigenic challenge. Organized follicles of mouse CALT contain T and B lymphocytes and follicular dendritic cells (Figure 1) [6]. Similar to gastric and airway mucosa CD11b+ and CD103+ subsets of dendritic cells are detected in murine conjunctiva [9] and contribute significantly to local immune response. Cells of CALT are believed to facilitate transport of antigenic matter across the conjunctival epithelial barrier [8]. Indeed CD11c+ DCs in the conjunctiva are capable of carrying topically applied soluble antigen to the draining cervical lymph nodes [10]. Additionally conjunctival epithelial cells respond to microbial stimuli via their toll-like receptors [11, 12]. Close proximity of CALT persistently exposes epithelial cells to immune mediators released in response to external stimuli. Exposure to different mediators or stimuli alters the secretory function of epithelial cells leading to changes in their barrier function.

Figure 1.

Epithelial and immune cells in the ocular mucosal tissue and immune responses associated with conjunctival inflammation.

Conjunctival epithelial and especially goblet cell responses to chronic inflammatory mediators including those produced in ocular allergy are the focus of the present review.

Responses to Chronic Inflammation

As a part of immune surveillance tissue innate immune cells induce an acute inflammatory response to clear offending agents and activate local antigen presenting cells to initiate adaptive immune responses in local draining lymph nodes. Under normal conditions such an acute response is followed by a resolution phase involving anti-inflammatory immune responses that facilitate restoration of normal physiological function of the tissue. However, unresolved acute inflammatory responses lead to persistent and sub-clinical inflammation over a prolonged period of time, resulting in a chronic disease. Chronic inflammation of the conjunctiva results from persistent allergies, bacterial or viral infections or autoimmune diseases. Although several inflammatory cytokines have been identified as associated with such chronic diseases [10, 13-15] very few studies have assessed their effect on the survival and function of the epithelial cells [12, 16].

a. Cytokines expressed in the conjunctiva

Both innate and adaptive immune cells are capable of expressing inflammatory cytokines. Ligation of toll like receptors on innate cells and/or epithelial cells by allergens or microbes induces secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, TNF-α and IL-6 as evidenced in a rodent model of LPS-mediated conjunctivitis [17]. Increased expression of TNF-α and IL-6 is also reported in chronic conjunctival inflammation associated with autoimmune Sjögren’s syndrome [10]. Following infections at mucosal sites γδ T cells, RORγt+ NK cells, and neutrophils are reported to express IL-17A [18]. Stressed epithelial cells can also induce local secretion of IFN-γ by γδ T cells [19]. Expression of IL-13 by NKT cells at mucosal surfaces is detected during autoimmune responses [16]. Under normal conditions these cytokines are part of protective responses that enhance anti-microbial activity, expression of chemokines that induce recruitment of neutrophils and mucin secretion [18, 19]. When left unresolved, such innate responses contribute to chronic conjunctivitis associated with diseases like allergic Vernal Keratoconjunctivitis (VKC) or autoimmune Steven-Johnson syndrome or Sjögren’s syndrome [10, 20, 21]. Cytokines like IFN-γ (Th1), IL-17 (Th17) and IL-13 (Th2) are also associated with corresponding adaptive immune effector subsets detected during allergic or mucosal autoimmune responses [22]. However, the exact cellular source of these cytokines in the conjunctiva remains to be determined.

b. Goblet cell responses

Although contribution of goblet cell hyperplasia and mucus hypersecretion to mucosal tissue pathology has been examined extensively in pulmonary and gastric mucosa, there is a paucity of knowledge regarding conjunctival goblet cell responses. A typical clinical sign of a chronic disease like vernal keratoconjunctivitis is thick mucoid discharge, however, there are few studies detailing its correlation with conjunctival goblet cell numbers and their mucous production [23, 24]. Similarly in autoimmune Sjögren’s syndrome significantly reduced expression of goblet cell derived mucin, MUC5AC, has been correlated with the observed decline in conjunctival goblet cell number, but exact changes induced by acute and chronic inflammatory stimuli are not clear.

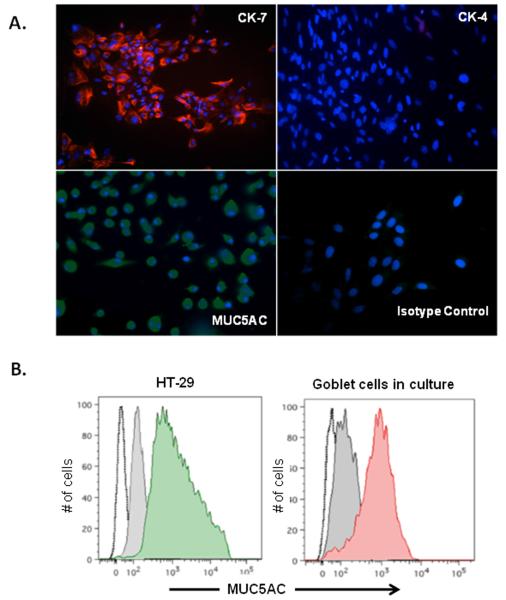

One of the primary reasons for lack of this information is the unavailability of homogenous conjunctival goblet cells cultures until recently. In the past year an adaptation of an original protocol developed by Dartt et al. [25] helped generate mouse goblet cell cultures [16] which like colonic goblet cell line HT-29, express MUC5AC (figure 2). These primary cultures also express cytokeratin -7 (CK-7) specifically associated with goblet cells, but not CK-4 found in stratified squamous epithelium of conjunctiva, confirming their homogeneity. Moreover, cultured cells also respond to cholinergic stimulation by carbachol by increasing their secretion of MUC5AC and express receptors for inflammatory cytokines such as IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-17A and IL-13 thereby facilitating assessment of effects of inflammatory mediators (figure 3).

Figure 2.

Immunohistochemical and flowcytometric characterization of mouse conjunctiva derived primary goblet cell cultures. Reproduced with permission from reference 16 (Contreras-Ruiz et al., Mediator Inflamm. 2013;2013:636812. doi: 10.1155/2013/636812).

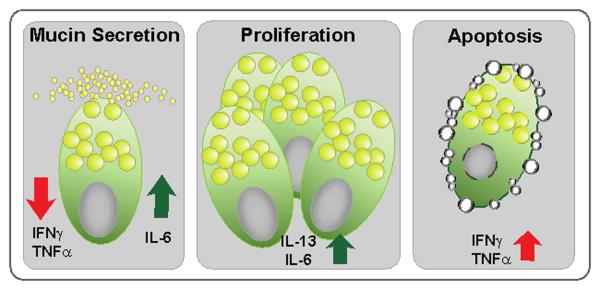

Figure 3.

Mouse goblet cell responses to inflammatory cytokines summarized.

Both IFN-γ and TNF-α exposure of cultured mouse goblet cells inhibit their carbachol-stimulated MUC5AC secretion and induce apoptotic cell death. These changes in goblet cell responses in vitro explain the pathologic mechanism underlying reduced conjunctival goblet cell density and secreted tear MUC5AC levels during autoimmune Sjögren’s syndrome in mice and humans [10, 13]. Primary goblet cell culture exposure to cytokines IL-6 and IL-13 induced their proliferation, however interestingly only the former enhanced MUC5AC secretion. Thus IL-6 expressed in response to microbial stimuli may indeed facilitate microbial clearance as a part of normal defense mechanism. Moreover, it is also apparent that in allergic diseases IL-13 may be associated only with goblet cell hyperplasia and not mucin hypersecretion. These observations further suggest potential efficacy of anti-IL-6 or anti-IL-13 treatment in relieving clinical signs of ocular allergies resulting from goblet cell hyperplasia.

Increased expression of IL-13 was also noted in the ocular mucosa in a mouse model of Sjögren’s syndrome similar to that reported in other mucosal autoimmune disease [16]. The significant decline in conjunctival goblet cells in this model as seen in Sjögren’s patients, precedes a period of goblet cell hyperplasia with no corresponding increase in tear MUC5AC levels. The in vitro responses of cultured goblet cells, now lend a plausible explanation to such pathology. While elevated IL-13 expression in the conjunctiva may induce goblet cell proliferation and increase their numbers, the concomitantly increased expression of IFN-γ and TNF-α may induce goblet cell death and therefore a sharp decline in their numbers in chronic diseases like Sjögren’s syndrome. Based on these observations anti-IL-13 or anti-IL-6 therapeutic approaches can be speculated to be ineffective in autoimmune conjunctivitis. This example illustrates how preclinical mouse models of conjunctivitis and availability of primary mouse goblet cell culture provide opportunity to evaluate and understand goblet cell responses to acute and chronic inflammation in the conjunctiva.

Responses to Allergic Mediators

Conjunctival goblet cell mucin (MUC5AC) production is dependent upon the rate of mucin synthesis, mucin secretion, goblet cell proliferation, and goblet cell apoptosis. Allergic mediators could directly interact with goblet cells to increase the amount of mucin on the ocular surface by increasing mucin synthesis and secretion as well as by increasing cell proliferation and decreasing apoptosis.

a. Mucin Synthesis and Secretion

There have been no published studies on the regulation of conjunctival goblet cell mucin synthesis in ocular allergy either in vivo or in cell culture. In health activation of corneal afferent sensory nerves stimulates goblet cell secretion by activation of efferent parasympathetic nerves that release cholinergic and VIPergic neurotransmitters [26]. [27, 28]. Exogenous addition of agonists of muscarinic and VIP receptors also elevate secretion [28-30]. In allergic conjunctivitis both dromic activation of nerves and antidromic release of neurotransmitters could stimulate goblet cell secretion. As itch and pain are two neurally-mediated symptoms of allergic conjunctivitis, activation of corneal or conjunctival sensory nerves by allergic mediators to cause a reflex stimulation of goblet cells via the efferent parasympathetic nerves could be a mechanism by which goblet cell secretion could be increased in allergic conjunctivitis. In addition, the neurotransmitters Substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) could be released from the corneal and conjunctival sensory nerve endings by neurogenic inflammation and could interact directly with the goblet cells. To understand the role of goblet cell secretion in ocular allergy, the role of sensory nerves and their neurotransmitters is critical to investigate.

An important pathway shown to stimulate goblet cell secretion is release of mediators and cytokines from infiltrating immune cells such as mast cells, eosinophils, neutrophils, T cells, and macrophages [31]. The most thoroughly studied allergic mediator is histamine that can be released by mast cells and basophils. All four histamine receptors (H1-H4) are present in both rat and human goblet cells [32]. Histamine itself and agonists of all four histamine receptors each stimulate goblet cell secretion and antagonists block histamine-stimulated goblet cell secretion [32]. Histamine induces mucin secretion by increasing the intracellular [Ca2+] and activating extracellular regulated kinase (ERK1/2) [33, 34]. Thus goblet cells are a direct target of one of the important allergic mediators, histamine.

Other pro-inflammatory mediators produced by infiltrating immune cells, in addition to histamine, stimulate goblet cell secretion. Mast cells and eosinophils can produce the cysteinyl leukotrienes (LT) LTC4, LTD4, and LTE4. The receptors for the cysteinyl leukotrienes Cys-LT1 and Cys-LT2 are both present on conjunctival goblet cells [35]. LTC4, LTD4 and LTE4 each stimulate conjunctival goblet cell secretion. LTD4 and to some extent LTE4 use the Cys-LT1 receptor. In addition, the leukotriene LTB4 and the pro-inflammatory prostaglandin D2 also stimulate goblet cell secretion, but their mechanisms of action have yet to be determined.

b. Goblet Cell Proliferation and Apoptosis

Conjunctival goblet cells are able to proliferate both in vivo [36] and in cell culture. Evidence shows that the growth factor epidermal growth factor (EGF) stimulates goblet cell proliferation in culture [37-40]. Preliminary data from an in vivo mouse model of ocular allergy [41] supports a role for allergic mediators in goblet cell proliferation (Saban D. and Dartt D. personal communication 2014). The number of filled conjunctival goblet cells was increased in the challenged compared to naïve mice suggesting that allergic mediators stimulate goblet cell proliferation. Although the effects of histamine, leukotrienes, and prostaglandins on goblet cell proliferation in culture have yet to be tested, as discussed previously the Th2 cytokine IL-13 increases mouse conjunctival goblet cell proliferation [16] and IL-13 knock out mice have a decrease in conjunctival goblet cells [42].

Alteration in conjunctival goblet cell apoptosis could also change mucin production. As discussed previously Contreas-Ruiz [16] found that the Th2 cytokine IL-13 decreased goblet cell apoptosis. Thus IL-13 has a coordinated effect on conjunctival goblet cells to increase mucin production by stimulating cell proliferation and inhibiting cell apoptosis. It is important to investigate the effect of other allergic mediators on goblet cell proliferation and apoptosis to determine if in ocular allergy there is a multipronged, coordinated regulation of goblet cell mucin production by increasing mucin synthesis and secretion along with increasing cellular proliferation and decreasing apoptosis similarly to the effect of cytokines in mouse model of Sjogren’s syndrome.

Conclusions

Conjunctiva with its specialized goblet cells and lymphoid tissue is a major, critical component in the response of the ocular surface to controlling chronic inflammation including ocular allergy. Goblet cell production of the secretory mucin MUC5AC protects the ocular surface and is a target of regulation by allergic and inflammatory mediators produced by local innate and adaptive immune cells. These mediators alter goblet cell proliferation, secretion, and cell survival. Allergic mediators including histamine, leukotrienes, and prostaglandins directly stimulate goblet cell secretion. Inflammatory cytokines can regulate secretion, proliferation, and apoptosis of these cells. In particular the opposing effects of IL-13, TNFα, and IFNγ on goblet cell survival control the changes in goblet cell number and tear MUC5AC that occur over time in chronic inflammatory diseases of the ocular surface. Preclinical mouse models of ocular surface inflammation and allergy along with conjunctival goblet cell culture provide a unique opportunity to evaluate and understand goblet cell responses to acute and chronic inflammation in the conjunctiva.

KEYPOINTS.

Conjunctival goblet cell secretion, proliferation, and survival are direct targets of allergic and inflammatory mediators.

Preclinical mouse models of ocular allergy and chronic inflammation along with conjunctival goblet cells in culture provide a unique opportunity to study goblet cells responses during these chronic ocular surface diseases.

Cytokines like IFN-γ, IL-17A and IL-13 are produced by both innate and adaptive immune effectors as a part of protective mucosal immunity and when unresolved contribute to chronic disease pathology.

Acute inflammatory responses involving cytokine IL-6 may induce goblet cell hyperplasia and mucin hypersecretion but chronic inflammation involving IFN-γ and TNF-α is associated with loss of goblet cells and mucin secretion.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH EY019470, EY022415 (DAD) and NIH EY015472 (SM). The authors thank Robin Hodges and Bruce Turpie for their editorial assistance.

Abbreviations

- NKT cells

natural killer T cells

- CALT

conjunctiva associated lymphoid tissue

- CGRP

calcitonin gene-related peptide

- ERK 1/2

extracellular regulated kinase 1/2

- CysLT

cysteinyl leukotriene

- IL

interleukin

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor α

- IFNγ

interferon γ

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- TSP-1

thrombospondin-1

- CK

cytokeratin

- EGF

epidermal growth factor

- OVA

ovalbumin

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Hattrup CL, Gendler SJ. Structure and function of the cell surface (tethered) mucins. Annu Rev Physiol. 2008;70:431–457. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Inatomi T, Spurr-Michaud S, Tisdale AS, et al. Expression of secretory mucin genes by human conjunctival epithelia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996;37:1684–1692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paulsen FP, Berry MS. Mucins and TFF peptides of the tear film and lacrimal apparatus. Prog Histochem Cytochem. 2006;41:1–53. doi: 10.1016/j.proghi.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dartt DA. Control of mucin production by ocular surface epithelial cells. Exp Eye Res. 2004;78:173–185. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mantelli F, Argueso P. Functions of ocular surface mucins in health and disease. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;8:477–483. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e32830e6b04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **6.Siebelmann S, Gehlsen U, Huttmann G, et al. Development, alteration and real time dynamics of conjunctiva-associated lymphoid tissue. PLoS One. 2013;8:e82355. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **. In depth description of CALT and associated cells in mice.

- 7.Knop N, Knop E. Conjunctiva-associated lymphoid tissue in the human eye. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:1270–1279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reinoso R, Martin-Sanz R, Martino M, et al. Topographical distribution and characterization of epithelial cells and intraepithelial lymphocytes in the human ocular mucosa. Mucosal Immunol. 2012;5:455–467. doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *9.Khandelwal P, Blanco-Mezquita T, Emami P, et al. Ocular mucosal CD11b+ and CD103+ mouse dendritic cells under normal conditions and in allergic immune responses. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64193. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *. In this paper authors identify CD11b+ and CD103+ dendritic cells in the conjuctiva similar to those described at other mucosal surfaces.

- *10.Contreras-Ruiz L, Regenfuss B, Mir FA, et al. Conjunctival inflammation in thrombospondin-1 deficient mouse model of Sjogren's syndrome. PLoS One. 2013;8:e75937. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *. In this paper authors describe chronic inflammatory cytokines associated with mouse model of autoimmune Sjögren’s syndrome.

- 11.Kojima K, Ueta M, Hamuro J, et al. Human conjunctival epithelial cells express functional Toll-like receptor 5. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92:411–416. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2007.128322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGilligan VE, Gregory-Ksander MS, Li D, et al. Staphylococcus aureus activates the NLRP3 inflammasome in human and rat conjunctival goblet cells. PLoS One. 2013;8:e74010. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caffery BE, Joyce E, Heynen ML, et al. Quantification of conjunctival TNF-alpha in aqueous-deficient dry eye. Optom Vis Sci. 2014;91:156–162. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0000000000000133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Venza I, Visalli M, Cucinotta M, et al. NOD2 triggers PGE2 synthesis leading to IL-8 activation in Staphylococcus aureus-infected human conjunctival epithelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;440:551–557. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.09.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vichyanond P, Pacharn P, Pleyer U, et al. Vernal keratoconjunctivitis: A severe allergic eye disease with remodeling changes. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2014;25:314–322. doi: 10.1111/pai.12197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **16.Contreras-Ruiz L, Ghosh-Mitra A, Shatos MA, et al. Modulation of conjunctival goblet cell function by inflammatory cytokines. Mediators Inflamm. 2013;2013:636812. doi: 10.1155/2013/636812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **. Authors describe primary culture of mouse conjunctiva derived goblet cells and changes to their function and survival in response to their exposure to inflammatory cytokines.

- 17.Fernandez-Robredo P, Recalde S, Moreno-Orduna M, et al. Azithromycin reduces inflammation in a rat model of acute conjunctivitis. Mol Vis. 2013;19:153–165. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khader SA, Gaffen SL, Kolls JK. Th17 cells at the crossroads of innate and adaptive immunity against infectious diseases at the mucosa. Mucosal Immunol. 2009;2:403–411. doi: 10.1038/mi.2009.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Girardi M. Immunosurveillance and immunoregulation by gammadelta T cells. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:25–31. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams GP, Tomlins PJ, Denniston AK, et al. Elevation of conjunctival epithelial CD45INTCD11b(+)CD16(+)CD14(−) neutrophils in ocular Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:4578–4585. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-11859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oray M, Toker E. Tear cytokine levels in vernal keratoconjunctivitis: the effect of topical 0.05% cyclosporine a therapy. Cornea. 2013;32:1149–1154. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31828ffdf8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fuss IJ, Heller F, Boirivant M, et al. Nonclassical CD1d-restricted NK T cells that produce IL-13 characterize an atypical Th2 response in ulcerative colitis. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1490–1497. doi: 10.1172/JCI19836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dogru M, Asano-Kato N, Tanaka M, et al. Ocular surface and MUC5AC alterations in atopic patients with corneal shield ulcers. Curr Eye Res. 2005;30:897–908. doi: 10.1080/02713680500196715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu Y, Matsumoto Y, Dogru M, et al. The differences of tear function and ocular surface findings in patients with atopic keratoconjunctivitis and vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Allergy. 2007;62:917–925. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shatos MA, Rios JD, Tepavcevic V, et al. Isolation, characterization, and propagation of rat conjunctival goblet cells in vitro. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:1455–1464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kessler TL, Mercer HJ, Zieske JD, et al. Stimulation of goblet cell mucous secretion by activation of nerves in rat conjunctiva. Curr Eye Res. 1995;14:985–992. doi: 10.3109/02713689508998519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dartt DA, Kessler TL, Chung EH, et al. Vasoactive intestinal peptide-stimulated glycoconjugate secretion from conjunctival goblet cells. Exp Eye Res. 1996;63:27–34. doi: 10.1006/exer.1996.0088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kanno H, Horikawa Y, Hodges RR, et al. Cholinergic agonists transactivate EGFR and stimulate MAPK to induce goblet cell secretion. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2003;284:C988–998. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00582.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rios JD, Zoukhri D, Rawe IM, et al. Immunolocalization of muscarinic and VIP receptor subtypes and their role in stimulating goblet cell secretion. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:1102–1111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hodges RR, Bair JA, Carozza RB, et al. Signaling pathways used by EGF to stimulate conjunctival goblet cell secretion. Exp Eye Res. 2012;103:99–113. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2012.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McDermott AM, Perez V, Huang AJ, et al. Pathways of corneal and ocular surface inflammation: a perspective from the cullen symposium. Ocul Surf. 2005;3:S131–138. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hayashi D, Li D, Hayashi C, et al. Role of histamine and its receptor subtypes in stimulation of conjunctival goblet cell secretion. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:2993–3003. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li D, Carozza RB, Shatos MA, et al. Effect of histamine on Ca(2+)-dependent signaling pathways in rat conjunctival goblet cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:6928–6938. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-10163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **34.Li D, Hodges RR, Jiao J, et al. Resolvin D1 and aspirin-triggered resolvin D1 regulate histamine-stimulated conjunctival goblet cell secretion. Mucosal Immunol. 2013;6:1119–1130. doi: 10.1038/mi.2013.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **. The authors discovered the molecular mechanism by which proresolution mediators terminate histamine stimulated conjunctival goblet cell secretion.

- 35.Dartt DA, Hodges RR, Li D, et al. Conjunctival goblet cell secretion stimulated by leukotrienes is reduced by resolvins D1 and E1 to promote resolution of inflammation. J Immunol. 2011;186:4455–4466. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wei ZG, Cotsarelis G, Sun TT, et al. Label-retaining cells are preferentially located in fornical epithelium: implications on conjunctival epithelial homeostasis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995;36:236–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gu J, Chen L, Shatos MA, et al. Presence of EGF growth factor ligands and their effects on cultured rat conjunctival goblet cell proliferation. Exp Eye Res. 2008;86:322–334. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shatos MA, Gu J, Hodges RR, et al. ERK/p44p42 mitogen-activated protein kinase mediates EGF-stimulated proliferation of conjunctival goblet cells in culture. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:3351–3359. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shatos MA, Hodges RR, Oshi Y, et al. Role of cPKCalpha and nPKCepsilon in EGF-stimulated goblet cell proliferation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:614–620. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *40.Li D, Shatos MA, Hodges RR, et al. Role of PKCalpha activation of Src, PI-3K/AKT, and ERK in EGF-stimulated proliferation of rat and human conjunctival goblet cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:5661–5674. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-12473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *. Description of cellular signaling pathways that stimulate conjunctival goblet cell proliferation.

- 41.Lee HS, Schlereth S, Khandelwal P, et al. Ocular allergy modulation to hi-dose antigen sensitization is a Treg-dependent process. PLoS One. 2013;8:e75769. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.De Paiva CS, Raince JK, McClellan AJ, et al. Homeostatic control of conjunctival mucosal goblet cells by NKT-derived IL-13. Mucosal Immunol. 2011;4:397–408. doi: 10.1038/mi.2010.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]