Abstract

Protein function is largely dependent on coordinated and dynamic interactions of the protein with biomolecules including other proteins, nucleic acids and lipids. While powerful methods for global profiling of protein-protein and protein-nucleic acid interactions are available, proteome-wide mapping of protein-lipid interactions is still challenging and rarely performed. The emergence of bifunctional lipid probes with photoactivatable and clickable groups offers new chemical tools for globally profiling protein-lipid interactions under cellular contexts. In this review, we summarize recent advances in the development of bifunctional lipid probes for studying protein-lipid interactions. We also highlight how in vivo photocrosslinking reactions contribute to the characterization of lipid-binding proteins and lipidation-mediated protein-protein interactions.

Introduction

Lipids comprise the largest class of metabolites in cells with a huge diversity of chemical identities [1]. They are not only the essential structural components of biological membranes, but also involved in a wide variety of cellular functions from cell signaling to transcriptional regulation to protein trafficking and modification. Lipids often closely interact with proteins to fulfill their cellular functions, which regulates the subcellular localization and activity of proteins. For example, the specific interaction between phosphatidylinositol-(3,4,5)-trisphosphate (PIP3) and PH domain of Akt recruits the protein from cytoplasm to plasma membrane, leading to protein activation [2]. Notably, a large number of protein domains, such as PIP3-binding PH domain and diacylglcerol (DAG)-binding C1 domain, have evolved to bind specific lipid species [2]. In addition, dysregulation of lipid-mediated pathways is known to contribute to a series of pathological conditions [3-5], further underlying the functional importance of proteinlipid interactions. Therefore, elucidating protein-lipid interactions is crucial for understanding the functional roles of lipids and lipid-binding proteins in physiological and pathological conditions in biology.

Various biochemical and biophysical methods have been used to study proteinlipid interactions, including cosedimentation and coflotation assays, fluorescence spectroscopy, X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy and atomic force microscopy (AFM) [6,7]. Of particular interest is X-ray crystallography, which is able to provide complete structural insight of the lipid-binding site of a protein [8]. Several systematic screening methods have also been developed to profile protein-lipid interactions on a proteome-wide scale using microarrays [9,10] or affinity purification-mass spectrometry [11,12]. However, these methods are all conducted in vitro, when the native lipid environment required for retention of certain protein-lipid interactions, especially those between integral membrane proteins and lipids, is destroyed by detergents during cell lysis. Moreover, weak and transient protein-lipid interactions may also be disrupted and lost during in vitro studies.

The photocrosslinking strategy represents a powerful approach to overcome some of the challenges for studying protein-lipid interactions [13]. Once photoactivatable groups (Table 1) are introduced into the biomolecules of interest, irradiation with UV light can generate highly reactive species that can form covalent bonds with any neighboring molecules. The resulting stable complexes are then amenable to purification and further characterization. As the UV-induced crosslinking reaction can be conducted in live and intact cells, specific interactions between biomolecules in cellular contexts can be captured. Photocrosslinking methods are also useful for mapping weak and transient interactions between biomolecules. Indeed, in vivo photocrosslinking reactions have been receiving increasing attention for studying protein-protein interactions, which has been reviewed elsewhere [14].

Table 1.

Properties of commonly used photoactivatable groups. The structures, activated species, potential side-reactions upon photoactivation and general features for each photoactivatable group are summarized.

| Photoactivatable group | Reactive species | Less reactive species | Chemical properties |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

normally activated at 250 nm, small in size, easy for synthesis, easily convert to ketene imine. |

|

|

activated at 350 nm, generally less reactive, low reactivity to water, reversible, large in size. | |

|

|

|

activated at 350 nm, small in size, very reactive, more efficient in hydrophobic environments than in water. |

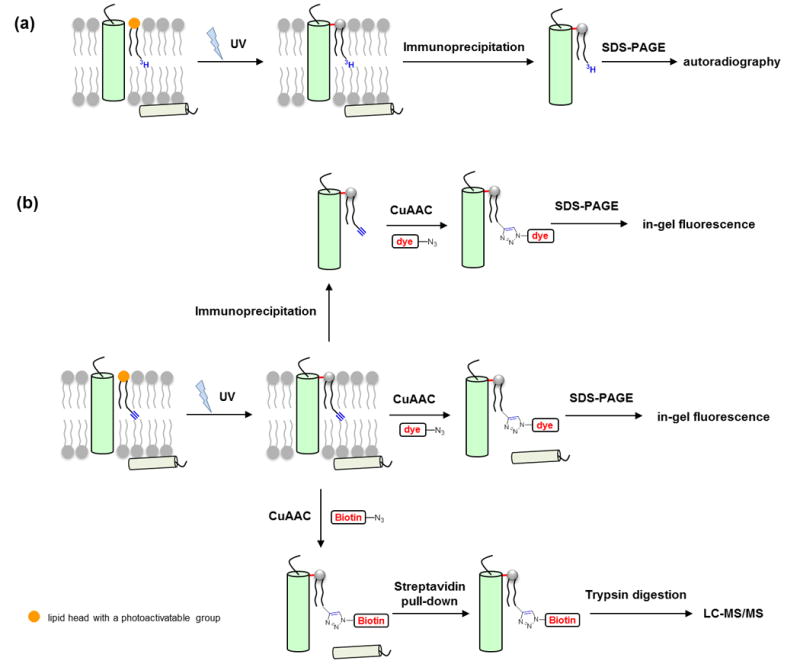

Photoactivatable lipid probes have been applied to study protein-lipid interactions (Figure 1a) for nearly 40 years [15], but have mostly been restricted to in vitro studies. Recently, the widespread application of bioorthogonal reactions for biological discovery [16] has inspired renewed interest in these classical lipid probes, especially for in vivo photocrosslinking. In this review, we begin with a brief overview of the practical aspects of photoactivatable lipid probes for studying protein-lipid interactions. Then we discuss the combination of photoactivatable lipid probes with clickable groups as a promising strategy for developing new bifunctional lipid probes. Next, we highlight recently described bifunctional lipid probes for in vivo photocrosslinking studies to characterize protein-lipid interactions and lipidation-mediated protein-protein interactions.

Figure 1.

Photocrosslinking strategy for studying protein-lipid interactions. (a) Radiolabeled photoactivatable lipid probes are incorporated into biological membranes in vitro or in vivo. Photoirradiation induces crosslinking between the probe and interacting proteins. After immunoprecipitation, the protein of interest is analyzed by autoradiography. (b) Bifunctionalized photoactivatable and clickable lipid probes are incorporated into biological membranes in vitro or in vivo. Photoirradiation induces crosslinking between the probe and interacting proteins. The protein of interest is subjected to immunoprecipitation and a click reaction with azide-fluorophore, and then analyzed by in-gel fluorescence. Alternatively, the whole proteome is subjected to a click reaction with azide-fluorophore or azide-biotin for in-gel fluorescence detection or affinity enrichment, respectively. The enriched protein-lipid complexes are digested and identified by mass spectrometry. The lipid head with a photoactivatable group is shown in orange. Note that while the scheme only depicts the capture of integral membrane proteins, this strategy is also effective for crosslinking peripheral proteins that bind lipids.

Photoactivatable lipid probes for studying protein-lipid interactions

The development of photoactivatable lipid probes has a long history. The first photoactivatable lipids were reported by the Khorana group as early as 1975 [17]. Since then, a variety of photoactivatable lipids, including phospholipids, sphingolipids and sterols, have been described and applied to analyze protein-lipid interactions (Figure 1a). Readers are referred to a recent review [18•] for the repertoire of currently available photoactivatable lipid probes. These photoactivatable lipids differ in the positions and chemical structures of the photoactivatable groups. For instance, photoactivatable groups may be incorporated into phospholipids and glycolipids either at the polar heads or in the fatty acid chains for capturing peripheral or integral membrane proteins, respectively. Similarly, various photocrosslinking sterol probes have been described by attaching or integrating photoactive functionalities to the polar hydroxyl groups, the fused rings or hydrophobic tails of sterol.

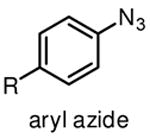

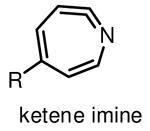

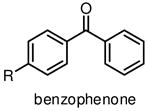

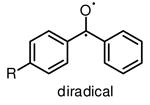

Among commonly used photoactivatable functionalities are aryl azides, benzophenones, and diazirines (Table 1), sharing the features of bioorthogonality, chemical stability and high reactivity upon photoactivation [13,15,18]. They also possess distinct advantages and drawbacks for photocrosslinking studies. Aryl azides crosslink with nearby molecules through formation of a highly reactive nitrene species upon photoirradiation with UV light at 250 nm. Aryl azides are small in size and detectable by bioorthogonal reactions [19], such as the Staudinger ligation [20] and copper(I) catalyzed azide–alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC) reaction [21], making them widely used for photocrosslinking studies. However, the short wavelength UV light used for activation of aryl azides may induce nonspecific crosslinking of proteins and DNA and may also cause photodamage to cells. Another drawback of using aryl azides as photoactivatable groups is that the highly reactive nitrene species can easily convert to ketenimine [22] (Table 1), which only reacts with nucleophiles, such as water, thereby resulting in decreased photocrosslinking efficiency and increased nonspecific crosslinking.

Benzophenones can be activated by relatively long wavelength UV light at 350 nm to produce reactive diradicals, which are known to be efficient hydrogen abstractor [15]. Interestingly, diradicals preferentially react with C-H bonds even in the presence of water [23], a unique characteristic for the utility of benzophenones in aqueous media or hydrophilic environments. Compared to nitrene and carbene, activated diradical is less reactive with a lifetime as long as 120 μs [23], and can convert back to benzophenone if no crosslink occurs. High photocrosslinking efficiency of benzophenone is therefore achieved by simply increasing the UV irradiation time, with potential risks of increased nonspecific crosslinking and photodamage to biological samples. Apparent drawbacks of benzophenone as photocrosslinking group include its large size and low reactivity of diradical.

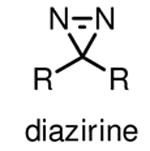

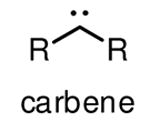

Diazirines refer to cyclopropene-like rings with two double-bonded nitrogen atoms. They are the smallest photoactive functionality, ensuring that the incorporation of diazirines causes minimal steric perturbation to molecules under investigation. Diazirines exhibit a characteristic UV absorbance at 350 nm, and can be efficiently activated by UV light at this wavelength to generate highly reactive carbenes [24]. The relatively long wavelength UV light required for activation of diazirines in principle minimizes the incidence of nonspecific photocrosslinking and photodamage to cells, thus making diazirines desirable for in-cell photocrosslinking studies. Carbenes are much more reactive than nitrenes and diradicals, typically with half-lifes in the nanosecond range [24], to any C-H, N-H, and O-H bonds in close proximity to form stable C-C, C-N, and C-O bonds, respectively. Concerns about diazirines as ideal photoactivatable groups include the fast reaction of carbenes with water and the rearrangement of diazirines into diazo isomers upon photoirradiation [25] (Table 1), both resulting in loss of photocrosslinking efficiency. Nonetheless, diazirines are currently considered as the most desirable photocrosslinking groups because of the small size, long wavelength UV activation and high crosslinking reactivity. Diazirines are especially suitable for capturing protein-lipid interactions, as carbenes imbedded in the hydrophobic areas of membrane crosslink with nearby molecules more efficiently than in water [18,26]. However, it is still worth mentioning that the selection of photocrosslinking group or lipid probe is crucial for specific applications. There is no single photoactivatable group or lipid which can be used for various protein-lipid binding events. It is therefore crucial to design and screen different lipid probes for a specific experiment on the basis of lipid structure, photocrosslinking efficiency and targets.

In most cases, photoactivatable lipid probes can be readily incorporated into biological membranes by directly incubating the probes with membrane samples or intact cells. Lipids usually have very low critical micellar concentrations and rapidly form micelles in aqueous media [18]. Thus lipid probes should be used at very low concentration, usually below the critical micellar concentrations, as micelle formation impedes the probe insertion into membranes and may give rise to nonspecific crosslinked products due to micelles sticking to peripheral membrane proteins [27]. For in vivo applications lipid probes should be cell membrane permeable or can be easily introduced into live cells. For instance, negatively charged phosphates of phospholipids may be chemically caged with labile esters to achieve membrane permeability [28]. Alternatively, hydrophobic lipid probes can be delivered into biological membranes by cyclodextrins [29•] or lipid binding proteins [27].

Following the incorporation of lipid probes into biological membranes and photocrosslinking process, the analysis and identification of photocrosslinked proteins have been historically challenging. Over the past decades, additional detection tags including radiolabel and fluorous tags have been incorporated into photoactive lipid probes for analysis of photocrosslinked proteins [18] (Figure 1a). For example, to examine whether a protein of interest is photocrosslinked with a photoactive and radiolabelled lipid probe, the protein of interest is immunoprecipitated with an appropriate antibody, separated with gel electrophoresis, and then analyzed by autoradiography (Figure 1a). These probes undoubtedly provide valuable information to investigate individual proteins of interest. However, they do not allow rapid and global identification of lipid-binding proteins on a proteome scale as they lack a handle for protein enrichment. Additionally, radiolabelling suffers from other disadvantages such as long acquisition time (often weeks to months) and radioactive hazards. Therefore, new enrichment and detection strategies are needed to facilitate the characterization of protein-lipid interactions.

Bifunctional lipid probes for in vitro applications

The last decade has witnessed the remarkable development of bioorthogonal reactions [19,30,31], which have allowed analysis of a variety of biological molecules in diverse biological contexts [16]. Among multiple bioorthogonal reactions the most frequently used is copper(I)-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition reaction (CuAAC) [21], as alkyne and azide are synthetically accessible and small enough to minimize possible perturbation to biomolecules in which they are incorporated. The extensive application of bioorthogonal reactions for tracking biomolecules has inspired new bifunctional lipid probes for studying protein-lipid interactions, which, in addition to photoactivatable groups, contain bioorthogonal functionalities such as alkyne or azide as chemical handles [27,32,33]. As illustrated in Figure 1b, following the insertion of a bifunctional lipid probe into biological membranes, UV irradiation activates the photoactivatable group and enables crosslinking of proximate proteins with the probe to form stable protein-lipid complexes. Then the alkyne or azide handle reacts with either a fluorescent dye or biotin bearing a counterpart handle through CuAAC for sensitive fluorescence detection or for affinity enrichment and proteomic analysis of the crosslinked proteinlipid complexes, respectively (Figure 1b). Individual proteins of interest can also be immunoprecipitated and then subjected to CuAAC with a fluorescent dye for in-gel fluorescence detection (Figure 1b).

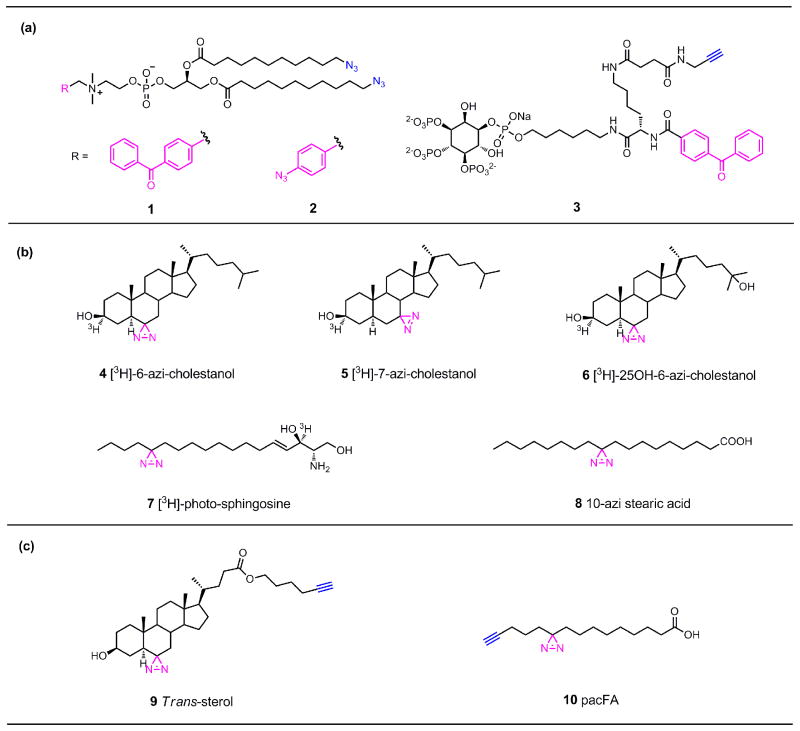

Notably, the concept of photocrosslinking followed with bioorthogonal detection of crosslinked products is one of the bases for activity-based protein profiling (ABPP), which has been extensively used to characterize protein functions in diverse biological contexts [34]. The initial demonstration of this strategy for characterization and identification of lipid-binding proteins was described by de Kroon and co-workers in 2009 [32,35••]. To identify proteins interacting with phosphatidylcholine (PC)headgroups at mitochondrial membrane interface, they synthesized bifunctional PC analogs (1, 2) containing clickable azides at both acyl chains as well as different photoactivatable groups (benzophenone, phenylazide, or diazirines) on the quaternary ammonium group of PC (Figure 2a). After being validated in a model membrane system, these lipid probes were employed for photocrosslinking experiments in the inner mitochondrial membrane from S. cerevisiae, followed by click reactions for fluorescent detection and enrichment of the photocrosslinked protein-lipid complexes. Interestingly, probes containing benzophenone and phenylazide as photoactivatable groups were found to give rise to distinct, albeit partially overlapping, photocrosslinking protein profiles, while the probe with diazirine as the photoactivatable group failed to provide significant crosslinking to proteins, strongly suggesting that selection of photoactivatable group is application-specific and needs proper optimization. Finally, mass spectrometry analysis of photocrosslinked proteins after biotinylation with a click reaction and affinity enrichment successfully identified both well-established and newly disclosed PC-interacting proteins.

Figure 2.

Representative photoactivatable lipid probes for studying protein-lipid interactions. (a) Bifunctional lipid probes for studying protein-phosphatidylcholine (1, 2) and protein-PI(3,4,5)P3 (3) interactions in vitro. (b) Tritium-labeled photoactivatable probes for capturing proteins that interact with cholesterols (4, 5, 6), sphingosine (7) and phosphatidylcholine (8) in vivo. (c) Bifunctional lipid probes for global detection and profiling of cholesterol-binding (9) and glycerolipid-binding (10) proteins in vivo.

The Best group also described bifunctional lipid probes corresponding to phosphatidic acid (PA) [36] and phosphatidylinositol polyphosphates (PIPns) [37-39], both of which are important signaling lipids in diverse biological processes. These bifunctional probes were able to bind with known PA or PIPns receptors even though bulky benzophenones and linkers bearing alkynes were introduced into the lipid headgroups [36,38••]. Notably, one of the bifunctional probes derived from PI(3,4,5)P3 (3) has been utilized for a proteomic photocrosslinking study in cell extracts [38••] (Figure 2a). The photolabeled proteins were detected by in-gel fluorescence after a click reaction with rhodamine and identified by mass spectrometry after biotinylation and affinity chromatography, yielding both known and new PI(3,4,5)P3-binding proteins with a total number of 265. In addition, to identify new phosphatidylserine (PS) receptor proteins Bong and coworkers described the synthesis of a series of bifunctional PS analogs with both benzophenones and alkynes installed at PS acyl chains [40].

Bifunctional lipid probes for in vivo photocrosslinking of protein-lipid interactions

Photoactivatable lipid probes, including diazirines-containing analogs of cholesterol, sphingosine and steric acid, have shown great potential for dissecting protein-lipid interactions in vivo, as they can be readily introduced into live cells and represent perfect mimics for natural lipids. For example, tritium-labeled diazirinecontaining cholesterol derivatives (4, 5, 6) have been used to photocrosslink synaptophysin [29•], caveolin [41], and oxysterol-binding protein-related proteins [42] in live cells (Figure 2b). Similarly, a tritium-labeled sphingosine analog with diazirine in the carbon chain, [3H]-photo-sphingosine (7), has been developed to capture sphingosineinteracting proteins such as caveolin [43•] and COPI machinery protein p24 [44•] in live cells (Figure 2b). Metabolic labeling of live cells with [3H]-choline and diazirinecontaining stearic acid (8) together allows biosynthetic generation of [3H]-photophosphatidylcholine, which was used to analyze protein-PC interactions [29] (Figure 2b).

Recently, bifunctional lipid probes have emerged as a powerful chemoproteomic tool for global profiling of lipid-binding proteins in native biological systems. Cravatt and coworkers described the first clickable and photoactivatable cholesterol probes (9) for mapping cholesterol-protein interactions on proteome scale directly in living cells [45••] (Figure 2c). These bifunctional cholesterol probes contain diazirines fused at the 6 position of the steroid core and alkyne functionalities incorporated into the hydrophobic alkyl tail. In-gel fluorescence analysis after in-cell photocrosslinking and click with aziderhodamine indicated that the probes crosslinked a subset of proteins in a UV-dependent manner. Following a click reaction with azide-biotin and enrichment using streptavidin chromatography, the proteins photocrosslinked with cholesterol probes were analyzed by quantitative mass spectrometry, which allowed the identification of over 250 highly confident cholesterol-binding proteins, including many known cholesterol binders such as Scap, caveolin, tetraspanin CD82, the sterol transport ARV1 and the sterol biosynthetic enzyme HMG-CoA reductase. In addition, many new cholesterol-binding candidates were also identified including cholesterol regulatory enzymes and proteins involved in vesicular transport and protein glycosylation.

To visualize and profile protein-lipid interactions in vivo, Haberkant and coworkers synthesized a diazirine- and alkyne-functionalized 15-carbon fatty acid [46••], pacFA (10), which can be metabolically incorporated into all major classes of glycerolipids as well as into proteins as fatty acylation in live cells (Figure 2c). As indicated by in-gel fluorescence analysis after a click reaction with azide-Alexa488, the bifunctional fatty acid, pacFA, photolabeled a distinguishable subset of proteins compared to the labeling profile without UV irradiation, indicating that pacFA was able to photocrosslink proteins in a native context. CuAAC with azide-biotin followed by affinity purification and mass spectrometry analysis of pacFA-photocrosslinked proteins revealed that majority of these proteins resided in endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and mitochondria, involving in lipid metabolism, protein biosynthesis and membrane trafficking. In addition, pacFA was also utilized to visualize photocrosslinked proteins in cells and C. elegans, which were fed pacFA, UV irradiated, fixed in methanol, extracted with chloroform and subjected to a click reaction with azide-Alexa488 for fluorescence imaging, showing selective staining of ER in cells and intestinal epithelial cells as well as muscle cells in worms. Collectively, these studies have demonstrated that clickable and photoactivatable lipid probes represent exciting and efficient chemical tools for robust visualization and large-scale profiling of lipid-interacting proteins in diverse biological contexts.

In vivo photocrosslinking of lipidation-mediated protein-protein interactions

In eukaryotes, a wide range of proteins are covalently modified with lipids, prominently as S-prenylation, S-palmitoylation and N-myristoylation. Lipid modifications of proteins regulate their membrane affinity, localization, and protein-protein interactions [47,48]. The analysis of protein-protein interactions of lipidated membrane proteins can be challenging, as the native membrane environment required for retaining these interactions is often destroyed during cell lysis and difficult to reconstitute in vitro. The photocrosslinking strategy provides a powerful approach to solve this problem.

Indeed, photoactivatable isoprenoids have been utilized to investigate the roles of S-prenylation in mediating protein-protein interactions in vitro. Protein S-prenylation, involving the alkylation of C-terminal cysteine residue on CaaX or CC motifs with an isoprenoid group, is an essential form of lipidation required by most small GTPases for their membrane targeting and activity in cells [47]. Distefano and coworkers described photoactivatable prenylcysteine analogs as a mimic of the C-terminus of S-prenylated proteins [49,50]. These probes have been shown to photocrosslink Rho GDPdissociation inhibitor (RhoGDI), a protein specifically recognizing isoprenoid moieties of Rho proteins in vitro. A variety of peptides containing photoactivatable isoprenoid moieties as well as photoactivatable farnesyl diphosphate analogs have also been developed for studying isoprenylcysteine carboxyl methyltransferases (Icmts) [51] and farnesyl diphosphate utilizing enzymes [52], respectively.

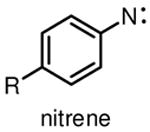

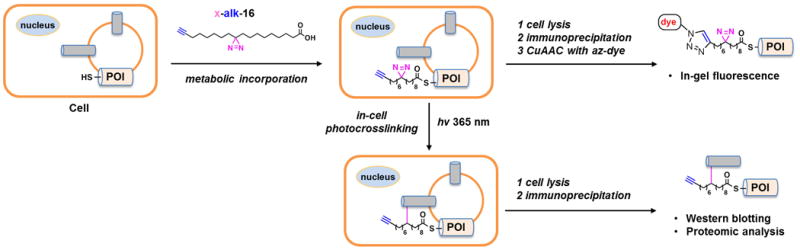

Our group has been particularly interested in protein S-palmitoylation, a reversible posttranslational modification on cysteine residues with a palmitate group controlling the proper localization and functions of many membrane proteins [48,53]. To explore the role of S-palmitoylation in regulating protein-protein interactions in cells, we synthesized a bifunctional 18-carbon palmitic acid analog x-alk-16 [54••], which contains an internal diazirine and a terminal alkynyl (Figure 3). As revealed by in-gel fluorescence after CuAAC with azide-rhodamine, the palmitic acid analog was shown to be metabolically incorporated into key cysteine residues of known S-palmitoylated proteins including H-Ras as well as IFITM3 [55,56] (Figure 3). Upon in-cell photoactivation x-alk-16 efficiently induced crosslinking of IFITM3 dimerization in an Spalmitoylation dependent manner as detected by western blotting, highlighting the importance of S-palmitoylation in stable IFITM3 oligomerization in vivo. Importantly, combination of this in-cell photocrosslinking strategy with immunoprecipitation and mass spectrometry analysis allowed the identification of 43 IFITM3 interacting candidates (Figure 3), most of which are membrane-associated and involved in sterol metabolism and protein transport. These results suggest that this in-cell photocrosslinking strategy will be an exciting and efficient approach for the characterization of S-palmitoylated membrane protein complexes under native contexts and will also help to reveal the functional importance of S-palmitoylation on proteins of interest.

Figure 3.

In-cell photocrosslinking strategy for capturing palmitoylation-mediated protein-protein interaction by using bifunctional fatty acid x-alk-16. Bifunctional fatty acid x-alk-16 is first incubated with live cells. The incorporation of x-alk-16 into Spalmitoylated proteins of interest (POI) is detected by in-gel fluorescence after immunoprecipitation and CuAAC with azide-fluorophore (az-dye). In-cell photocrosslinking enables formation of covalent complexes between x-alk-16-modified POI and interacting partners. After immunoprecipitation the crosslinked complexes are characterized by western blotting or mass spectrometry.

Summary and future directions

Over the past four decades, photoactivatable lipid probes have greatly facilitated our understanding of specific protein-lipid interactions and the underlying functions of these interactions. Yet the considerable advances in bioorthogonal reactions during the past decade are breathing new lives into these classical probes. The integration of bioorthogonal tags into photoactivatable lipid probes opens up a new avenue for characterizing a wide range of lipid-interacting proteins in a variety of biological systems, as the bioorthogonal tags such as alkyne or azide allow versatile attachment of any reporter molecules through CuAAC for robust fluorescence detection and imaging or global profiling of lipid-interacting proteins, which are not possible previously by using mono-functionalized photoactivatable probes.

In principle, this strategy can be generalized to any lipid components. Thus, various bifunctional lipid probes are expected in future from different contributions, which will enable a global search of proteins which bind specific lipids. In addition to identifying new lipid-interacting proteins, bifunctional lipid probes can also be utilized for mapping the lipid binding sites of these proteins, which has been challenging for traditional mono-functionalized probes. Meanwhile, there are still potential concerns, including that the introduction of two functional groups into lipid molecules may impair some protein-lipid interactions, and that the reactivity and position of photoactivatable groups may affect the photocrosslinking results. To overcome these two problems, a set of probes with varying structures and properties should be prepared and compared. Moreover, the lipid probes could be metabolized into other lipid components in vivo, thus complicating analysis of the photocrosslinking results and identification of the actual crosslinked lipids. In this regard, non-metabolized lipid probes are more desirable for probing specific protein-lipid interactions. Otherwise, lipidomic analysis may complement the determination of exact crosslinked lipid components.

Photoactivatable fatty acid analogs may also be applied for capturing lipidation-mediated protein-protein interactions in vivo, as they could be readily incorporated into lipidated proteins through post-translational or co-translational modifications and then induce covalent photocrosslinking of lipidated proteins with any neighboring proteins in live cells. This new strategy has been established by utilizing a bifunctional palmitic acid analog x-alk-16 to capture interacting partners of S-palmitoylated IFITM3 and provides new opportunities for studying the functional roles of protein lipidation and specific S-palmitoylated proteins.

While large scale proteomic analysis is able to provide invaluable information about protein-lipid or protein-protein interactions, extensive studies are still required to further validate these interactions at both biochemical and cellular levels. Following that the biggest challenge is to address the biological functions of each interaction. Although structural studies of membrane proteins with lipids are becoming increasingly more accessible, new tools are still needed to explore these interactions in living cells. The development and application of photoactive lipid probes summarized here should facilitate the detailed characterization of protein-lipid and lipidated protein-protein interactions.

Acknowledgments

H.C.H. acknowledges support from NIH-NIGMS R01 GM087544 grant and Starr Cancer Consortium I7-A717. X.Y. is supported by the Tri-Institutional Program in Chemical Biology at The Rockefeller University.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as

•of special interest

• •of outstanding interest

- 1.van Meer G, de Kroon AIPM. Lipid map of the mammalian cell. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:5–8. doi: 10.1242/jcs.071233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lemmon MA. Membrane recognition by phospholipid-binding domains. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:99–111. doi: 10.1038/nrm2328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wymann MP, Schneiter R. Lipid signalling in disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:162–176. doi: 10.1038/nrm2335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Di Paolo G, Kim TW. Linking lipids to Alzheimer's disease: cholesterol and beyond. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12:284–296. doi: 10.1038/nrn3012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Santos CR, Schulze A. Lipid metabolism in cancer. FEBS J. 2012;279:2610–2623. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2012.08644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao H, Lappalainen P. A simple guide to biochemical approaches for analyzing protein–lipid interactions. Mol Biol Cell. 2012;23:2823–2830. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-07-0645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Contreras FX, Ernst AM, Wieland F, Brügger B. Specificity of Intramembrane Protein–Lipid Interactions. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3:a004705. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a004705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hunte C, Richers S. Lipids and membrane protein structures. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2008;18:406–411. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu H, Bilgin M, Bangham R, Hall D, Casamayor A, Bertone P, Lan N, Jansen R, Bidlingmaier S, Houfek T, et al. Global Analysis of Protein Activities Using Proteome Chips. Science. 2001;293:2101–2105. doi: 10.1126/science.1062191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saliba AE, Vonkova I, Ceschia S, Findlay GM, Maeda K, Tischer C, Deghou S, van Noort V, Bork P, Pawson T, et al. A quantitative liposome microarray to systematically characterize protein-lipid interactions. Nat Meth. 2014;11:47–50. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li X, Gianoulis TA, Yip KY, Gerstein M, Snyder M. Extensive In Vivo Metabolite-Protein Interactions Revealed by Large-Scale Systematic Analyses. Cell. 2010;143:639–650. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maeda K, Anand K, Chiapparino A, Kumar A, Poletto M, Kaksonen M, Gavin AC. Interactome map uncovers phosphatidylserine transport by oxysterolbinding proteins. Nature. 2013;501:257–261. doi: 10.1038/nature12430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tanaka Y, Bond MR, Kohler JJ. Photocrosslinkers illuminate interactions in living cells. Mol BioSyst. 2008;4:473–480. doi: 10.1039/b803218a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pham ND, Parker RB, Kohler JJ. Photocrosslinking approaches to interactome mapping. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2013;17:90–101. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2012.10.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brunner J. New Photolabeling and Crosslinking Methods. Annu Rev Biochem. 1993;62:483–514. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.62.070193.002411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grammel M, Hang HC. Chemical reporters for biological discovery. Nat Chem Biol. 2013;9:475–484. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chakrabarti P, Khorana HG. New approach to the study of phospholipid-protein interactions in biological membranes. Synthesis of fatty acids and phospholipids containing photosensitive groups. Biochemistry. 1975;14:5021–5033. doi: 10.1021/bi00694a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18•.Xia Y, Peng L. Photoactivatable Lipid Probes for Studying Biomembranes by Photoaffinity Labeling. Chem Rev. 2013;113:7880–7929. doi: 10.1021/cr300419p. This is a comprehensive review which summarizes all photoactivatable lipid probes reported in literature and highlights their applications. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prescher JA, Bertozzi CR. Chemistry in living systems. Nat Chem Biol. 2005;1:13–21. doi: 10.1038/nchembio0605-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saxon E, Bertozzi CR. Cell Surface Engineering by a Modified Staudinger Reaction. Science. 2000;287:2007–2010. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5460.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Q, Chan TR, Hilgraf R, Fokin VV, Sharpless KB, Finn MG. Bioconjugation by Copper(I)-Catalyzed Azide-Alkyne [3 + 2] Cycloaddition. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:3192–3193. doi: 10.1021/ja021381e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schrock AK, Schuster GB. Photochemistry of phenyl azide: chemical properties of the transient intermediates. J Am Chem Soc. 1984;106:5228–5234. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dorman G, Prestwich GD. Benzophenone photophores in biochemistry. Biochemistry. 1994;33:5661–5673. doi: 10.1021/bi00185a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Das J. Aliphatic Diazirines as Photoaffinity Probes for Proteins: Recent Developments. Chem Rev. 2011;111:4405–4417. doi: 10.1021/cr1002722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brunner J, Senn H, Richards FM. 3-Trifluoromethyl-3-phenyldiazirine. A new carbene generating group for photolabeling reagents. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:3313–3318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blencowe A, Hayes W. Development and application of diazirines in biological and synthetic macromolecular systems. Soft Matter. 2005;1:178–205. doi: 10.1039/b501989c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haberkant P, van Meer G. Protein-lipid interactions: paparazzi hunting for snapshots. Biol Chem. 2009;390:795–803. doi: 10.1515/BC.2009.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neef AB, Schultz C. Selective fluorescence labeling of lipids in living cells. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:1498–1500. doi: 10.1002/anie.200805507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29•.Thiele C, Hannah MJ, Fahrenholz F, Huttner WB. Cholesterol binds to synaptophysin and is required for biogenesis of synaptic vesicles. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:42–49. doi: 10.1038/71366. Photoactivatable cholesterol and glycerophospholipids were described in this paper to study in vivo protein-lipid interactions that contribute to the biogenesis of regulated secretory vesicles. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sletten EM, Bertozzi CR. From Mechanism to Mouse: A Tale of Two Bioorthogonal Reactions. Acc Chem Res. 2011;44:666–676. doi: 10.1021/ar200148z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lang K, Chin JW. Bioorthogonal Reactions for Labeling Proteins. ACS Chem Biol. 2014;9:16–20. doi: 10.1021/cb4009292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gubbens J, de Kroon AIPM. Proteome-wide detection of phospholipid-protein interactions in mitochondria by photocrosslinking and click chemistry. Mol BioSyst. 2010;6:1751–1759. doi: 10.1039/c003064n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haberkant P, Holthuis JCM. Fat & fabulous: Bifunctional lipids in the spotlight. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2014.01.003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbalip.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Cravatt BF, Wright AT, Kozarich JW. Activity-based protein profiling: from enzyme chemistry to proteomic chemistry. Annu Rev Biochem. 2008;77:383–414. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.101304.124125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35••.Gubbens J, Ruijter E, de Fays LEV, Damen JMA, de Kruijff B, Slijper M, Rijkers DTS, Liskamp RMJ, de Kroon AIPM. Photocrosslinking and Click Chemistry Enable the Specific Detection of Proteins Interacting with Phospholipids at the Membrane Interface. Chem Biol. 2009;16:3–14. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.11.009. This is probably the first demonstration of bifunctional lipid probes for detection and identification of phospholipid-interacting proteins in vitro. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith MD, Sudhahar CG, Gong D, Stahelin RV, Best MD. Modular synthesis of biologically active phosphatidic acid probes using click chemistry. Mol BioSyst. 2009;5:962–972. doi: 10.1039/b901420a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gong D, Bostic HE, Smith MD, Best MD. Synthesis of Modular Headgroup Conjugates Corresponding to All Seven Phosphatidylinositol Polyphosphate Isomers for Convenient Probe Generation. Eur J Org Chem. 2009;2009:4170–4179. [Google Scholar]

- 38••.Rowland MM, Bostic HE, Gong D, Speers AE, Lucas N, Cho W, Cravatt BF, Best MD. Phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-Trisphosphate Activity Probes for the Labeling and Proteomic Characterization of Protein Binding Partners. Biochemistry. 2011;50:11143–11161. doi: 10.1021/bi201636s. Bifunctional probes derived from PI(3,4,5)P3 were described in this paper. One of these probes was utilized for a proteomic photocrosslinking study in cell extracts to identify PI(3,4,5)P3-interacting proteins. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Best MD, Rowland MM, Bostic HE. Exploiting Bioorthogonal Chemistry to Elucidate Protein–Lipid Binding Interactions and Other Biological Roles of Phospholipids. Acc Chem Res. 2011;44:686–698. doi: 10.1021/ar200060y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bandyopadhyay S, Bong D. Synthesis of Trifunctional Phosphatidylserine Probes for Identification of Lipid-Binding Proteins. Eur J Org Chem. 2011;2011:751–758. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cruz JC, Thomas M, Wong E, Ohgami N, Sugii S, Curphey T, Chang CCY, Chang TY. Synthesis and biochemical properties of a new photoactivatable cholesterol analog 7,7-azocholestanol and its linoleate ester in Chinese hamster ovary cell lines. J Lipid Res. 2002;43:1341–1347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suchanek M, Hynynen R, Wohlfahrt G, Lehto M, Johansson M, Saarinen H, Radzikowska A, Thiele C, Olkkonen VM. The mammalian oxysterol-binding protein-related proteins (ORPs) bind 25-hydroxycholesterol in an evolutionarily conserved pocket. Biochem J. 2007;405:473–480. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43•.Haberkant P, Schmitt O, Contreras FX, Thiele C, Hanada K, Sprong H, Reinhard C, Wieland FT, Brugger B. Protein-sphingolipid interactions within cellular membranes. J Lipid Res. 2008;49:251–262. doi: 10.1194/jlr.D700023-JLR200. This paper describes a photoactivatable sphingolipid analog for studying sphingolipidinteracting proteins in vivo. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44•.Contreras FX, Ernst AM, Haberkant P, Bjorkholm P, Lindahl E, Gonen B, Tischer C, Elofsson A, von Heijne G, Thiele C, et al. Molecular recognition of a single sphingolipid species by a protein's transmembrane domain. Nature. 2012;481:525–529. doi: 10.1038/nature10742. This paper demonstrates application of the photoactivatable sphingolipid analog reported in [43] leading to discovery of a specific and functional interaction between COPI subunit p24 and sphingomyelin. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45••.Hulce JJ, Cognetta AB, Niphakis MJ, Tully SE, Cravatt BF. Proteome-wide mapping of cholesterol-interacting proteins in mammalian cells. Nat Methods. 2013;10:259–264. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2368. The paper demonstrates the full power of bifunctional cholesterol probes for proteome-wide identification of cholesterol-binding proteins in vivo. The authors utilized cholesterol analogs bearing diazirine and alkyne groups for capturing and isolating cholesterol-interacting proteins, and integrated quantitative mass spectrometry analysis for protein identification. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46••.Haberkant P, Raijmakers R, Wildwater M, Sachsenheimer T, Brügger B, Maeda K, Houweling M, Gavin AC, Schultz C, van Meer G, et al. In Vivo Profiling and Visualization of Cellular Protein–Lipid Interactions Using Bifunctional Fatty Acids. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2013;52:4033–4038. doi: 10.1002/anie.201210178. The authors utilized a bifunctional fatty acid analog bearing a diazirine and alkyne to globally identify lipid-binding proteins. The fatty acid analog was metabolically incorporated into glycerolipids and crosslinked with lipid-binding proteins upon photoactivation. The alkyne group allowed the authors to enrich these proteins for identification as well as image them in cells and worms. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Resh MD. Trafficking and signaling by fatty-acylated and prenylated proteins. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:584–590. doi: 10.1038/nchembio834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hang HC, Linder ME. Exploring protein lipidation with chemical biology. Chem Rev. 2011;111:6341–6358. doi: 10.1021/cr2001977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kale TA, Raab C, Yu N, Dean DC, Distefano MD. A Photoactivatable Prenylated Cysteine Designed to Study Isoprenoid Recognition. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:4373–4381. doi: 10.1021/ja0012016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kale TA, Distefano MD. Diazotrifluoropropionamido-Containing Prenylcysteines: Syntheses and Applications for Studying Isoprenoid–Protein Interactions. Org Lett. 2003;5:609–612. doi: 10.1021/ol026752a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vervacke JS, Funk AL, Wang YC, Strom M, Hrycyna CA, Distefano MD. Diazirine-Containing Photoactivatable Isoprenoid: Synthesis and Application in Studies with Isoprenylcysteine Carboxyl Methyltransferase. J Org Chem. 2014;79:1971–1978. doi: 10.1021/jo402600b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vervacke JS, Wang YC, Distefano MD. Photoactive Analogs of Farnesyl Diphosphate and Related Isoprenoids: Design and Applications in Studies of Medicinally Important Isoprenoid- Utilizing Enzymes. Curr Med Chem. 2013;20:1585–1594. doi: 10.2174/0929867311320120008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hang HC, Wilson JP, Charron G. Bioorthogonal chemical reporters for analyzing protein lipidation and lipid trafficking. Acc Chem Res. 2011;44:699–708. doi: 10.1021/ar200063v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54• •.Peng T, Hang HC. Bifunctional Fatty Acid Chemical Reporter for Analyzing Spalmitoylated Membrane Protein-Protein Interactions in Mammalian Cells. J Am Chem Soc. 2014 doi: 10.1021/ja502109n. Submitted. This paper demonstrates that a bifunctional fatty acid with an internal diazirine and a terminal alkyne is readily incorporated into S-palmitoylated proteins and induces photocrosslinking of S-palmitoylated proteins with their interacting partners in vivo. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yount JS, Moltedo B, Yang YY, Charron G, Moran TM, López CB, Hang HC. Palmitoylome profiling reveals S-palmitoylation–dependent antiviral activity of IFITM3. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6:610–614. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yount JS, Karssemeijer RA, Hang HC. S-Palmitoylation and Ubiquitination Differentially Regulate Interferon-induced Transmembrane Protein 3 (IFITM3)-mediated Resistance to Influenza Virus. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:19631–19641. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.362095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]