Abstract

Background

Internationally, health care services are under increasing pressure to provide high quality, accessible, timely interventions to an ever increasing aging population, with finite resources. Extended scope roles for allied health professionals is one strategy that could be undertaken by health care services to meet this demand. This review builds upon an earlier paper published in 2006 on the evidence relating to the impact extended scope roles have on health care services.

Methods

A systematic review of the literature focused on extended scope roles in three allied health professional groups, ie, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and speech pathology, was conducted. The search strategy mirrored an earlier systematic review methodology and was designed to include articles from 2005 onwards. All peer-reviewed published papers with evidence relating to effects on patients, other professionals, or the health service were included. All papers were critically appraised prior to data extraction.

Results

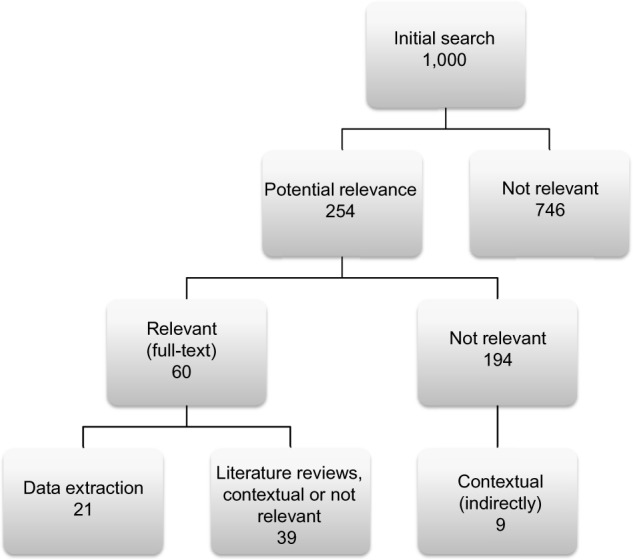

A total of 1,000 articles were identified by the search strategy; 254 articles were screened for relevance and 21 progressed to data extraction for inclusion in the systematic review.

Conclusion

Literature supporting extended scope roles exists; however, despite the earlier review calling for more robust evaluations regarding the impact on patient outcomes, cost-effectiveness, training requirements, niche identification, or sustainability, there appears to be limited research reported on the topic in the last 7 years. The evidence available suggests that extended scope practice allied health practitioners could be a cost-effective and consumer-accepted investment that health services can make to improve patient outcomes.

Keywords: allied health professionals, extended scope practice

Introduction

Worldwide there is a trend towards an ageing population.1 People are living longer, and subsequently there are higher levels of chronic disease.2–4 Health care services must operate with finite resources. Trends focused on funding increases are widely considered unsustainable.5,6 An international survey of eight industrialized countries described difficulties in terms of cost per patient and patient outcomes for each of the different health care systems. Due to the larger proportion of health funding for this age group, the survey focused on chronically ill patients. This research reported issues with access, care coordination, and efficiency (ie, duplication, patient perceptions of wasteful care), safety in terms of outside hospital errors, and processes to support patient self-management. It concluded that many of the participating countries were shifting resources from managing the traditional acute care to the more long-term chronic care required for the changing population demographic.4

Many foci for improvements around these issues have been reported in the literature, such as standardization of discharge and transition processes,2 technological innovations and their correlation with level of health care,7,8 and extended scope roles for non-medical practitioners.9–18

Traditional models of health service are generally managed around the needs and capabilities of individual disciplines, with medical practitioners considered the key decision-makers in aspects of referral, admission, and discharge. With limited specialist resources, this often equates to a long wait for service for patients, even for those patients who may benefit from early allied health input.15,18–21 Thus, allied health practitioners have been identified as possessing the key clinical skills and capability to bridge this service demand gap and act as the first point of contact within the patient’s health care journey.10,20–25 In essence, to improve patient access to timely health care, new extended scope allied health roles are being trialed with clinicians accessing specialized training outside the traditional scope of their discipline. This may involve identified tasks traditionally undertaken by medical, nursing, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, speech pathology, or other health professionals. A systematic review published in 2006 found variability in the use of terminology, and focused on proposing a working definition of extended scope of practice in terms of enhancement and substitution (enhancing job depth by adding skills within a profession and expanding job breadth by working across professional boundaries).15 In addition, this review highlighted that there was indeed support for introducing these roles; however, the majority of the publications at that time focused on reducing waiting times (and the burden on medical practitioners), with limited inclusions regarding the impact on patient outcomes, cost-effectiveness, training requirements, niche identification, or sustainability.

The aim of the current paper is to build on the aforementioned review by including recently published evidence relating to the effects these roles have on patient care, other professionals, and the health care service.

Materials and methods

This review updated and expanded on the evidence collected in a previously published systematic review by McPherson et al in 2006.15 Hence the search strategy was limited to the years 2005–2013 and followed the three-part PICO approach, ie, (P) patients/professions, (I) intervention, (O) outcome, omitting the (C) controls. The electronic databases PubMed, Embase, and CINAHL were searched using the full search terms described in the complete report by McPherson et al (see Supplementary material).16 Assistance from an experienced health librarian was used to ensure the strategy was implemented correctly. Following the initial computer-based search, there was one modification of the abstract screening process used by McPherson et al. The original review included five allied health groups based on the experience of the research team (physiotherapy, occupational therapy, speech pathology, paramedics, and radiography).15 Due to the perceived synergies of the roles within the health care system and patient contact point, only articles relating to physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and speech pathology were considered for inclusion in this current review. Paramedics and radiographers were excluded as these professions tended to work in more discrete patient contact areas, with extended scope relating almost exclusively to traditional medical roles. Therefore, only papers relating to extended scope practice (ESP) or advanced scope of practice for allied health practitioners (Adv HP), physiotherapy, occupational therapy, or speech pathology were screened. The other variance to the search strategy of McPherson et al was the exclusion “gray” literature, due to this literature not being able to progress to the critical appraisal point.15

All remaining titles and abstracts were screened for relevance by the first author; those abstracts then had their relevance confirmed or were deemed not relevant by the other two authors prior to full-text review and data extraction. Duplicate studies were excluded. Abstracts from conference proceedings were excluded (unless the published article was obtainable). Only English text versions were included. The full texts of 55 studies were retrieved and reviewed to confirm relevance and for possible data extraction. The reference lists and citations of these publications were hand-searched for further possible relevant articles. An additional five articles were included via this process.

Quality screening for data extraction followed the criteria outlined by McPherson et al (based on the Critical Skills Appraisal Skills Programme, the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination at York).16 Articles were screened for relevance and the presence of qualitative or quantitative data relating to ESP within the three professions by all three authors. All studies that reported data were included. Studies that were narrative with no data presented were excluded.

Studies that described traditional roles (not extended scope) were excluded. Evidence quality was designated based on the National Health and Medical Research Evidence Hierarchy.26 Due to the heterogeneity of the studies in both design and participant numbers, no meta-analysis was attempted.

An Excel spreadsheet for data extraction was compiled by the first author and subsequently reviewed and amended by two other authors.

Results

The initial search yielded 1,000 articles. Following abstract screening for potential relevance (n=254), the full texts of 55 articles were retrieved. An additional five articles were identified via searching of the reference lists or citations of the selected articles. Hence, a total of 60 full-text articles were reviewed for data extraction. Data extraction was not considered for 39 of these articles as these were literature reviews, duplicates, conference papers, editorials, commentaries, not relevant, or descriptive only (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Stages of search strategy results.

Most of the articles (including the reviews) related to physiotherapy ESP only (n=19), with five remaining articles including physiotherapy as part of a multiple discipline study. Only one article had data related to occupational therapy ESP. Data relating to ESP and speech pathology were found in the multiple discipline study and the systematic reviews. These articles are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of findings of articles selected for data extraction

| Reference | Study design | Level of evidence | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aiken et al20 | Cohort (n=76) | III-2 | Comparison of clinical impressions of orthopedic surgeons versus those of physiotherapists regarding future care in a postoperative outpatient setting using a standard scoring measure. Agreement was 78%–90%. Patient satisfaction scores did not differ significantly between the surgeon and physiotherapist. |

| Aiken et al21 | Cohort (n=107) | III-2 | Comparison of treatment by APP and three orthopedic surgeons, preoperatively, postoperatively, and by telephone over period of 1 year. Thirty-four percent of participants were non-surgical. Only one surgeon allowed the APP to triage and perform preoperative screening – his waitlist dropped from an average of 140 days to 40 days; surgery times changed from a minimum of 3 months for urgent to maximum of 6 months for all surgeries; his waitlist dropped from 200 to 59, and 16 additional days were available to spend in the operating theater (48 additional joint replacements). |

| Aiken et al27 | Cohort (n=38) | III-2 | Comparison between orthopedic surgeons and physiotherapists: rating as candidate for surgery, urgency, and recommendations for treatment. Patient perception of disability and satisfaction were reported, showing 100% agreement on surgery versus no surgery. Physiotherapists rated with a higher surgical priority than the orthopedic surgeons. Surgeons had a higher agreement level with patients regarding their disability level (78%) than the physiotherapists (52%). The physiotherapist recommended education or conservative treatment (97%) more than the surgeons (16%). Patients were satisfied or very satisfied with both professions. |

| Anaf and Sheppard47 | Qualitative (n=80) | III-3 | Survey of emergency room patients regarding the role of physiotherapy in emergency departments. NVivo software and manual techniques were used to analyze themes. Six key domains emerged, ie, sports injury management, musculoskeletal care, rehabilitation and mobility, pain management, respiratory care, and elderly patient management. Patients tended to perceive more traumatic or musculoskeletal skills as key roles for physiotherapists in the emergency room. |

| Boissonnault et al22 | Cohort (n=81) | III-3 | Comparison of patient care decisions by physical therapists and physician; 100% deemed appropriate by a physician chart reviewer. Only 10% of patients were referred for X-ray, and 4%–16% referred to physician for pain management or medical consultation. |

| Braund and Abbott37 | Survey (n=278) | III-3 | Survey of physiotherapists regarding their medicine recommendations to patients (out of scope); 81% sometimes or often recommend NSAIDs and 82% recommend paracetamol, 85% report they routinely provide information on possible side effects, and 65% on potential risks. |

| Davis et al48 | Case example | IV | Report of observations on a 5-month deployment regarding the workload division between physical therapists and orthopedic surgeons. More than 97% of musculoskeletal presentations were treated and returned to duty by the physical therapist alone. |

| Green et al36 | Survey (n=48, representation from each year over a 10-year period) | III-2 | Aimed to identify influence of postgraduate clinical master’s qualification on role extension. All respondents still working, with 83% having a clinical component to their role. Mean time from undergraduate to master’s qualification was 10.48 years; career pathway differed, with consultants achieving their post 8.7 years post qualification, 2.38 for lecturers; extended scope practitioners had their post on completion with clinical specialists 1 year prior. |

| Holdsworth et al12 | Survey (n=117) | III-2 | Survey regarding GP and physiotherapist perceptions of physiotherapy as first point of contact. High levels of confidence reported by GPs (96%) and physiotherapists (94%). Musculoskeletal referral patterns showed that 55% of physiotherapists reported an increase in referrals and 77% of GPs reported no change; 78% of all respondents reported definite benefits for musculoskeletal patients if physiotherapy involved in prescribing NSAIDs, issuing sick certificates, and requesting X-rays; 47% of physiotherapists felt that not all physiotherapists were experienced enough to be first point of contact. |

| Humphreys et al49 | Semistructured interviews (n=6) | III-3 | Collation of activities relevant to the consultant role. Five nurse consultants and one physiotherapy consultant participated in guided discussions to create an activity diary, which was then filled out for a period of 1 week. Activities grouped and hours totaled into expert practice (45.7%), leadership (28.8%), research (5.8%), and education (19.7%). |

| Kennedy et al31 | Cohort (n=123) | III-2 | Survey of patients post orthopedic surgery, comparing satisfaction with advanced practice physiotherapist and surgeon. Patient satisfaction (nine items) showed no significant difference in mean satisfaction scores between the orthopedic surgeon-led clinic versus the physiotherapy-led clinic. |

| Kilner and Sheppard42 | Survey (n=28) | IV | Survey of emergency department physiotherapists to determine roles, including ESP. The majority reported working in the ED for 1–2 years, did not hold additional qualifications, but had undertaken further training (ie, radiology education and plastering courses). Any additional qualifications were in the musculoskeletal area. Roles included assessment and treatment, education of other ED professionals, discharge planning, and organizational and role development. Opinions divided whether performing ESP tasks (ordering X-rays, plastering) or role not different from traditional role. |

| Li et al35 | Survey (n=258) | III-2 | Survey to understand physiotherapist’s practice in arthritis care, education needs, and views on emerging professional roles. The majority of participants reported adequate coverage in undergraduate training in history-taking, pathophysiology, and exercise prescription, care pre-post surgery, and prescription of mobility aids. Almost half of the respondents (41%–56%) indicated they were not interested in being a certified, specialized practitioner in arthritis. |

| Lineker et al29 | Retrospective cohort (n=58) | III-3 | Comparison of practice for extended role practitioners (physiotherapists, occupational therapists) and experienced therapists without extended role training in arthritis care. Random charts were retrospectively reviewed. Extended role therapists saw more moderate cases, were more likely to receive referrals for assessment (52% versus 14%), treat patients who did not have a confirmed diagnosis, record comorbidities, recommend physical activity, advocate with family, provide longer length of treatment in days than experienced but non-extended role trained therapists. |

| Lundon et al43 | Mixed methods, prospective (n=10) | III-3 | Comparison to evaluate participants’ learning and competency post completion of an academic program for arthritis care. Pre– points using a theory and practical skills assessment plus a structured interview found significant changes from baseline scores. |

| MacKay et al50 | Cohort (n=62) | III-2 | Comparison of recommendations of orthopedic surgeons versus physiotherapists for future treatment using a standardized form. Agreement was 91.8%. |

| McClellan et al38 | Survey (n=780) | III-3 | Survey of patient satisfaction seen by extended scope physiotherapy in ED (with soft tissue injury). Higher satisfaction with ESP (55%) compared with emergency nurse practitioners (39%) and doctors (36%). Improved posttreatment outcomes at 4 weeks trend observed. |

| Passalent et al32 | Survey (n=30) | III-2 | Longitudinal survey over a 2-year period surveys (every 3 months) to evaluate the extended role practitioner in arthritis care. Most respondents (89%) working in an extended role worked under a medical directive (75%), and ordered X-rays (82%), laboratory tests (64%), diagnostic ultrasounds (40%), recommending medication dosage changes (70%) and joint injections (90%). A small minority made medication changes independently (4%) or performed joint injections (5%). Longest median wait for service was 22 days. |

| Pearse et al51 | Cohort (n=150) | III-3 | Retrospective cohort audit of extended scope physiotherapist activity in an outpatient orthopedic clinic. ESP managed 66% independently, and 77% of patients were satisfied with clinic visit. A higher proportion of dissatisfied patients was found in the ESP only group when compared with the group seen by surgeons. |

| Rhon et al52 | Survey (n=107) | IV | Surveys to assess the perceptions of the impact of physiotherapists on the mission provided to physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and one dentist; 97% reported physiotherapists made a significant impact on the overall mission and 83% on patient prognosis, 92% regarded physiotherapists as experts in musculoskeletal problems, 74% felt a significant number of soldiers were able to remain in their on-site combat theater due to the presence of a physiotherapist rather than be sent home for conservative care. |

| Williamson et al45 | Focus group interviews (n=16) | III-3 | Focus group interviews of master’s program students for advanced practice roles to determine issues and concerns. Two main themes emerged, ie, opportunities for development and time pressure. Long-term benefits perceived from temporary hardship. |

Abbreviations: APP, advanced practice physiotherapist; ESP, extended scope practice; ED, emergency department; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; GP, general practitioner.

Results by discipline

Physiotherapy

The majority of literature related to physiotherapy ESP, which is similar to the findings of McPherson et al; however, there were no randomized controlled trials as originally recommended. The literature included cohort studies,20–22,27–31 surveys reporting tasks undertaken,12,32–38 and a number of systematic reviews relating to orthopedic outpatients13,18,39 or inflammatory conditions.40 Only one article reported on a pre–post impact that included patient outcomes.28 This described physiotherapists working within an orthopedic clinic, recommending conservative management for non-surgical patients, and reported improvements in patient outcome scores (chronic disease self-efficacy scores); however, no comparison was made with the surgical patient group or non-surgical patients who received no physiotherapist intervention (only orthopedic consultation). Further, there is no clarity in this article as to whether this outcome constitutes ESP for physiotherapy or merely full scope of practice? Indeed, one review conducted by Stanhope et al as a follow-up on ESP physiotherapy practice in orthopedics reported a lack of clear differentiation between extended scope and full scope practice, a continued paucity of research into the area, and that most studies are of a lower quality on the National Health and Medical Research Council.18 Further, Anaf and Sheppard proposed in their 2007 review that in the emergency department context, the reported tasks undertaken are within scope and are there for “advanced” (or full scope) and not “extended” scope of practice.41

A number of studies described tasks undertaken by ESP physiotherapists, including: triaging, referral to other services (including medical specialists), requesting investigations (radiology, pathology), educational resources, diagnostic ultrasounds, medication (limited prescription, monitoring, dosage changes), joint injections (recommend or perform), removing K-wires, simple suturing, and prescribing conservative management/treatment/exercises.12,13,15,18,29,37,40

Some of these tasks are not ESP in all contexts, with some performed under the oversight of a medical officer, some relating to funding restrictions dependent on legislation, and others related to uptake of policy.12,15,21,22,41,42 Indeed, as some authors have pointed out, due to legislative changes, what was once considered ESP for a profession becomes within scope, hence adding to the difficulty in definition of ESP for research purposes.11,15

It appears that physiotherapy ESP research is focused on direct access for musculoskeletal conditions (USA and Scotland), inflammatory conditions (Canada and Australia), and orthopedics (UK, Canada, and Australia). There are some studies relating to physiotherapy practice in the emergency department; however the consensus appears to be that this is not ESP, merely a different context.23,41,42

Occupational therapy

Similar to the findings of McPherson et al, studies relating to occupational therapy extended practice that met the criteria included both physiotherapists and occupational therapists. Three of these articles centered on a specific program for arthritis care.29,32,43 The studies explored the change in clinician knowledge following training, initially utilizing a practical skills assessment in addition to theory testing. This was followed up via a survey for 2 years to evaluate the impact of the training on practice and the tasks undertaken. It was reported that whilst the majority worked in extended scope roles and were able to order X-rays, laboratory tests, and ultrasounds, three quarters still worked under a medical directive.32 Patient outcomes were explored in terms of type of referral, treatment provided, and length of treatment. No data were reported on patient improvement or reduced waiting time to treatment. In addition, the study numbers were relatively small (n=58, n=30, and n=10) in comparison with the physiotherapy data (see Table 1).

One article related directly to occupational therapy ESP that did not make data extraction was a military case study that described the training, credentialing process, and tasks undertaken by an ESP.44 The training process included formal coursework coupled with a period of internship, ie, a model similarly described for ESP within other professions. Tasks included direct access, limit duty, referral to specialist clinics, triaging, and conservative management/treatment. The article aptly describes the role as a “force multiplier”, an underpinning objective stated for all ESP roles.

Speech pathology

Speech pathology ESP was included in articles surveying perceptions of professionals undertaking postgraduate studies, and within other published systematic reviews.15,45 No further specific studies were found outlining speech pathology extended scope trials that were included for data extraction. One article described the tasks and training undertaken by speech pathologists working within a neonatal intensive care unit; however, no data were included.46 This may indicate the infancy of this profession in extended scope role development.

Discussion

There continues to be high levels of interest in extended scope roles; however, the quality of evidence relating to their impact remains low and not inclusive of areas highlighted for future research by McPherson et al in 2006. The highest number of published articles by far was within the physiotherapy profession, with almost all relating to the treatment of orthopedic patients or those with inflammatory arthropathy. A number of systematic reviews have been published for specific physiotherapy areas of practice, with all discussing the low level of evidence found.13,15,18,39,40 In comparison, the occupational therapy and speech pathology professions appear to be in their infancy of extended scope roles, with only a few published articles identified and suitable for inclusion.15,43–45

It appears that the majority of the articles that describe outcomes in terms of reduced waiting times, do not consistently specify to which point in the patient journey – the Adv HP role or the medical profession or indeed both. Neither do they comment specifically on the proportion of patients who do not progress to medical specialist appointments following input from the Adv HP. One article mentioned that a percentage of patients did not need to see the surgeon.21 Both of these measurements would be integral in measuring cost-effectiveness, in terms of the health organization and the patient. Reduced cost to the patient in terms of travel to the health care facility, time away from work, and changes in quality of life related to earlier intervention. The most commonly cited method for measurement of cost-effectiveness at an organizational level relates to differences in wages paid to treat a patient (eg, Adv HP AU$58 versus medical specialist AU$128).18,22,39 The potential cost savings encompassing the impact on reducing the number of appointments is often not factored; frequently, the medical specialist orders tests and/or treatment from an allied health professional and then books a review with the patient.20 Additionally, the benefits to the health service may be realized further afield, in terms of increased medical specialist availability to acutely ill patients, surgical lists, or highly complex cases.12,20,21,27,48,52 By changing the way a patient enters the service, ie, having the Adv HP request routine information (pathology, radiology, treatment) ready for the first medical specialist appointment, may achieve cost benefits for both the health service and the patient in terms of a reduced number of appointments overall. The same may hold true for collection of routine follow-up information. Indeed, one study by Aiken et al in 2009 quantified this in terms of additional 16 days in the operating theater performing an additional 48 joint replacement procedures.21

Practical implications and future directions of research

Internationally, a number of innovative workforce redesign projects have explored the ability of allied health professionals to extend their scope of practice beyond traditional boundaries, for example, physiotherapists in an emergency department, physiotherapists in orthopedic clinics, physiotherapists and occupational therapists in arthritis care, occupational therapists in upper extremity management, and speech pathologists in fiber optic endoscopy.13,15,18,32,39–41,44 Reports of additional skills acquired include increased clinical reasoning, ordering and interpretation of diagnostics (radiology, ultrasound and pathology), limited medication management (prescription, dosage changes, monitoring), and procedures (joint injections, passing endoscopes, removing K-wires, applying plaster of Paris, simple suturing). Changes to health care practice included first point of contact (direct access), additional context of care (emergency department, orthopedic triage), and an increased role in education of both patients and other clinicians.12,22,27,29,36,38,41,49 The majority of these extended scope roles were implemented in the context of increasing patient demand, with varying levels of evaluation and use of terminology to describe the role. It appears that the majority of the literature focuses on reducing patient waiting times to medical specialist appointments (particularly for surgery) and comparing the categorization of these patients by advanced or extended scope allied health practitioners with that of their medical colleagues.20,21,27,30,48,50 There remains limited evidence as to the true impact in terms of overall patient waiting times. In fact, the majority of the literature describes these comparisons in terms of a retrospective audit or as a simultaneous clinical pathway. This appears to be the “groundwork” to convince health care professionals and managers that roles can be substituted. Only one study reported on the difference between one model of care and another. It found that the surgeon’s waitlist dropped from 140 to 40 days, his overall waitlist dropped from 200 to 59, and an additional 16 days were available to operate, with 48 additional surgeries performed.21

There was rudimentary discussion relating to the cost benefits this created for the health care service or the patients. All of the studies reporting on patient satisfaction found no difference between the allied health profession and the medical practitioner.20,21,27,31 In fact, one study reported patients valuing the additional time allied health practitioners spent in comparison with their medical colleagues.47 However, one study reported that although patient satisfaction was 77%, a higher proportion of dissatisfied patients were in the group seen by an extended scope practitioner only.51

Some of these roles have been described as advanced practice or practice in a non-traditional context, rather than as extended scope. Strong images of these roles on a continuum, such as the “skills escalator” described by Gilmore et al, as practitioners gain skills within their discipline to a highly skilled or “advanced level” then undertake training to develop additional skills to extend their scope of practice.11 Another strong image comes from the military context, where acquiring skills outside traditional roles through structured training and credentialing programs are described as a “force multiplier”.44

There appears to be emerging agreement regarding particular tasks that are considered extended scope, such as ordering and interpreting of plain film X-rays, limited prescribing rights, limited ordering of pathology tests, and specific injection tasks.13,15,18,40

Additionally, clarity around the context in which care is delivered does not necessarily mean the role involves extended scope practice. It is becoming more common to see these context-dependent roles described as advanced scope practice, such as physiotherapists working within musculoskeletal, orthopedic, and emergency pathways of care, and occupational therapists or physiotherapists working with arthritis. 21,23,25,28,38,40,42

Nine systematic literature reviews were found using the search strategy, the majority related to physiotherapy practice. All authors commented on the low quality of the research (with hierarchy ranging from II to IV) and a lack of improvement in the research over time.11,13,15,18,39–41,53 Initial searches reported varying numbers of articles, from approximately 150 to over 1,000; however, in all literature reviews, the majority of these were not included, in general less than 12. All authors commented on the positive reports, and outlined tasks performed by the roles, a high level of patient satisfaction, and impacts on process measures such as waiting times; however, they highlighted a lack of “robust data” in terms of patient outcomes, including effectiveness and information on specific training programs. The training programs described include ad hoc “on the job” training, specialized training programs with credentialing, and the development of more formalized tertiary masters level courses. It appears clear that the consensus is for a structured training environment with regular ongoing support, whilst maintaining a strong focus on independent practice.

Future research

As evidence is building, albeit at a low level from an academic perspective, it appears that patient access to care is improving, patients are satisfied with the care provided, and health care decision-makers are continuing to invest in establishing and trialing these new roles. It is acknowledged that there may be studies that were not found through this search or pragmatic evidence contained in the gray literature that contributes to this dialog. The challenge remains in terms of legislative barriers and inconsistencies. These barriers feed into maintaining the status quo, with a power differential towards the medical fraternity, with most extended scope practitioners still requiring a direct physician referral or to work under a “medical directive”.21,22,32,42 This exact bottleneck of all patients requiring specialist medical consultation prior to receiving care in conjunction with overworked junior doctors10,13,15 in addition to a shortage25,27,35 was described as a precursor to the implementation of trials of extended scope health practitioners.

So it seems that allied health practitioners can undertake training to appropriately learn and perform new skills outside the traditional scope of their practice, this improves patient access, is inferred to improve patient outcomes through earlier intervention in their health condition, releases medical specialist time (to perform surgeries or see complex patients), and no adverse outcomes have been reported, yet the defensiveness around scope creep remains. In a health care system that is increasingly stretched while purporting to be patient-focused, these legislative barriers appear to be based on historical perspectives rather than looking forward to enabling the health care industry to use “force multipliers” effectively.

Conclusion

Despite many literature reviews indicating a lack of high-quality research into the area of ESP for allied health professionals, and clear recommendations on evidence or study design required, little improvement has been noted between 2005 and 2013. Many studies have outlined tasks considered to be expanded scope, training frameworks, implementation processes, highlighted potential barriers and provided preliminary evidence in relation to positive effects in terms of ability to perform extended scope tasks, patient outcomes, patient satisfaction, and cost benefits. If one were to take a Bayesian perspective when reviewing the evidence thus far, it appears that ESP allied health practitioners could be a cost-effective, consumer-accepted investment that health services can make to improve patient outcomes.

Supplementary material

Search terms list

advanc* practi* OR consultant therapist* OR cross boundar* OR current role* OR enhan* practice* OR enhan* scope* OR existing role* OR existing scope* OR exp* practice* OR expan* scope* ORext* scope* OR exten* practice* OR interdisciplinary collaboration OR joint practice* OR multi* task* OR new role* OR new scope* OR physician exten* OR physician assist* OR profession* boundar* OR role* boundar* OR role* chang* OR role* collaborati* OR role* cross* OR role* defin* OR role* demarcation* OR role* ehan* OR role* expan* OR role* exten* OR role* interdisciplin* OR role* interprofessional* OR role* modern* OR role* overlap* OR role* professional* OR role* redefin* OR role* shar* OR role* shift* OR scope of practice OR shar* competenc* OR shift* boundar* OR skill interdisciplin* OR skill* overlap* OR skill* shar* OR specialist practitioner* OR traditional role* OR transdisciplinary practice* OR consultant practitioner* OR clinical specialist* OR int??disciplinary competenc* OR int??disciplinary practice*

Exercise therap* OR kinesiotherap* OR manual therap* OR physiotherapy OR physical therap* OR physio OR physios OR physiotherapy* OR ergotherap* OR occupational therap* OR recreational therap* audiolog* OR auditory rehabilitation OR language therap* OR logopaed* OR rehabilitation of speech and language disorders OR speech and language OR speech and language pathologist* OR speech and language rehabilitation OR speech language pathologist* OR speech language therap* OR speech pathology* OR speech rehabilitation OR speech therap* OR speech train*

Nuclear medicine OR radiographer* OR radiography OR radiologic* technician* OR radiologic* technologist* OR radiology personnel OR technology radiologic OR technology-radiologic OR air ambulance* OR ambulance paramedic* OR ambulance personnel OR ambulance staff* OR ambulance technician* OR crisis intervention OR critical care OR emergenc* medic* OR emergency care OR emergency health OR emergency personnel OR emergency service* OR emergency treatment* OR first aid* OR paramedic* OR rapid response* OR resuscitation OR urgent transport* OR d?spatch* OR priority d?spatch

Allied health OR generic therapist* OR health manpower OR health occupation* OR health personnel OR multiprofessional* OR profession* allied to health OR profession* allied to medicine OR rehabilitati*

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this research.

References

- 1.ONU World population ageing 1950–2050. 2002. Available from: www.un.org/esa/population/publications/worldageing19502050/

- 2.Pieper C, Kolankowska I. Health care transition in Germany – standardization of procedures and improvement actions. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2011;4:215–221. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S22035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lubitz J, Cai L, Kramarow E, Lentzner H. Health, life expectancy, and health care spending among the elderly. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1048–1055. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa020614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schoen C, Osborn R, How SK, Doty MM, Peugh J. In chronic condition: experiences of patients with complex health care needs, in eight countries, 2008. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28:w1–w16. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.w1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goss JR. Projection of Australian health care expenditure by disease, 2003 to 2033. Canberra, Australia: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2008. [Accessed August 18, 2014]. Available from: http://www.aihw.gov.au/publications/hwe/pahced03-33/pahced03-33.pd. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . Public health expenditure in Australia 2008–2009. Canberra, Australia: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2011. [Accessed August 18, 2014]. Available from; http://www.aihw.gov.au/publication-detail/?id=10737418329&tab=1. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gill PS. Technological innovation and its effect on public health in the United States. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2013;6:31–40. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S34810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gray LC, Wright OR, Cutler AJ, Scuffham PA, Wootton R. Geriatric ward rounds by video conference: a solution for rural hospitals. Med J Aust. 2009;191:605–608. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2009.tb03345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chopra M, Munro S, Lavis JN, Vist G, Bennett S. Effects of policy options for human resources for health: an analysis of systematic reviews. Lancet. 2008;371:668–674. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60305-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duckett SJ. Health workforce design for the 21st century. Aust Health Rev. 2005;29:201–210. doi: 10.1071/ah050201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gilmore LG, Morris J, Murphy K, Grimmer-Somers K, Kumar S. Skills escalator in allied health: a time for reflection and refocus. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2011;3:53–58. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holdsworth LK, Webster VS, McFadyen AK. Physiotherapists’ and general practitioners’ views of self-referral and physiotherapy scope of practice: results from a national trial. Physiotherapy. 2008;94:236–243. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kersten P, McPherson K, Lattimer V, George S, Breton A, Ellis B. Physiotherapy extended scope of practice – who is doing what and why? Physiotherapy. 2007;93:235–242. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kersten SG, Lattimer V, Ellis B. Briefing paper: Extending the practice of allied health professionals in the NHS. Available from: http://www.nets.nihr.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/81248/BP-08-1203-031.pdf.

- 15.McPherson K, Kersten P, George S, et al. A systematic review of evidence about extended roles for allied health professionals. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2006;11:240–247. doi: 10.1258/135581906778476544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McPherson K, Kersten P, George S, et al. Extended roles for allied health professionals in the NHS. 2004. Available from: http://www.nets.nihr.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0019/64342/FR-08-1203-031.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Sibbald B, Shen J, McBride A. Changing the skill-mix of the health care workforce. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2004;9(Suppl 1):28–38. doi: 10.1258/135581904322724112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stanhope J, Grimmer-Somers K, Milanese S, Kumar S, Morris J. Extended scope physiotherapy roles for orthopedic outpatients: an update systematic review of the literature. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2012;5:37–45. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S28891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lundon K, Shupak R, Sunstrum-Mann L, Galet D, Schneider R. Leading change in the transformation of arthritis care: development of an inter-professional academic-clinical education training model. Healthc Q. 2008;11:62–68. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2008.19858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aiken AB, Atkinson M, Harrison MM, Hope J. Reducing hip and knee replacement wait times: an expanded role for physiotherapists in orthopedic surgical clinics. Healthc Q. 2007;10:88–91. doi: 10.12927/hcq..18807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aiken AB, Harrison MM, Hope J. Role of the advanced practice physiotherapist in decreasing surgical wait times. Healthc Q. 2009;12:80–83. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2013.20881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boissonnault WG, Badke MB, Powers JM. Pursuit and implementation of hospital-based outpatient direct access to physical therapy services: an administrative case report. Phys Ther. 2010;90:100–109. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20080244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crane J, Delany C. Physiotherapists in emergency departments: responsibilities, accountability and education. Physiotherapy. 2013;99:95–100. doi: 10.1016/j.physio.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McPherson KM, Reid DA. New roles in health care: what are the key questions? Med J Aust. 2007;186:614–615. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb01075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robarts S, Kennedy D, MacLeod AM, Findlay H, Gollish J. A framework for the development and implementation of an advanced practice role for physiotherapists that improves access and quality of care for patients. Healthc Q. 2008;11:67–75. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2008.19619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Merlin T, Weston A, Tooher R. Extending an evidence hierarchy to include topics other than treatment: revising the Australian ‘levels of evidence’. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2009;9(1):34. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-9-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aiken AB, Harrison MM, Atkinson M, Hope J. Easing the burden for joint replacement wait times: the role of the expanded practice physiotherapist. Healthc Q. 2008;11:62–66. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2008.19618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.MacKay C, Davis A, Mohamed N, Badley E. Physical therapists working in expanded roles in orthopaedic clinics: impact on non-surgical patients with arthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2012;20:S166. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lineker SC, Lundon K, Shupak R, Schneider R, Mackay C, Varatharasan N. Arthritis extended-role practitioners: impact on community practice (an exploratory study) Physiother Can. 2011;63:434–442. doi: 10.3138/ptc.2010-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grimmer-Somers K, Morris J, Murphy K. Multidisciplinary musculoskeletal triage clinic: outcomes 12 months on; Scientific poster RHPA-P3 presented at the Australian Rheumatology Association annual meeting; May 12–15, 2012; Canberra, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kennedy DM, Robarts S, Woodhouse L. Patients are satisfied with advanced practice physiotherapists in a role traditionally performed by orthopaedic surgeons. Physiotherapy Canada. 2010;62(4):298–305. doi: 10.3138/physio.62.4.298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Passalent LA, Kennedy C, Warmington K, et al. System integration and clinical utilization of the Advanced Clinician Practitioner in Arthritis Care (ACPAC) program-trained extended role practitioners in Ontario: a two-year, system-level evaluation. Healthc Policy. 2013;8:56–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rhon DI. A physical therapist experience, observation, and practice with an infantry brigade combat team in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom. Mil Med. 2010;175:442–447. doi: 10.7205/milmed-d-09-00097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kilner E. What evidence is there that a physiotherapy service in the emergency department improves health outcomes? A systematic review. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2011;16:51–58. doi: 10.1258/jhsrp.2010.009129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li LC, Westby MD, Sutton E, Thompson M, Sayre EC, Casimiro L. Canadian physiotherapists’ views on certification, specialisation, extended role practice, and entry-level training in rheumatology. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:88. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Green A, Perry J, Harrison K. The influence of a postgraduate clinical master’s qualification in manual therapy on the careers of physiotherapists in the United Kingdom. Man Ther. 2008;13:139–147. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Braund R, Abbott JH. Recommending NSAIDs and paracetamol: a survey of New Zealand physiotherapists’ knowledge and behaviours. Physiother Res Int. 2011;16:43–49. doi: 10.1002/pri.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McClellan C, Greenwood R, Benger J. Effect of an extended scope physiotherapy service on patient satisfaction and the outcome of soft tissue injuries in an adult emergency department. Emergency Medicine Journal. 2006;23(5):384–387. doi: 10.1136/emj.2005.029231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Desmeules F, Roy J-S, MacDermid JC, Champagne F, Hinse O, Woodhouse LJ. Advanced practice physiotherapy in patients with musculoskeletal disorders: a systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13:107. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-13-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stanhope J, Beaton K, Grimmer-Somers K, Morris J. The role of extended scope physiotherapists in managing patients with inflammatory arthropathies: a systematic review. Open Access Rheumatology: Research and Reviews. 2012. [Accessed August 19, 2014]. Available from: http://www.dovepress.com/the-role-of-extended-scope-physiotherapists-in-managing-patients-with--peer-reviewed-article-OARRR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Anaf S, Sheppard LA. Physiotherapy as a clinical service in emergency departments: a narrative review. Physiotherapy. 2007;93:243–252. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kilner E, Sheppard L. The ‘lone ranger’: a descriptive study of physiotherapy practice in Australian emergency departments. Physiotherapy. 2010;96:248–256. doi: 10.1016/j.physio.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lundon K, Shupak R, Reeves S, Schneider R, McIlroy JH. The Advanced Clinician Practitioner in Arthritis Care program: an interprofessional model for transfer of knowledge for advanced practice practitioners. J Interprof Care. 2009;23:198–200. doi: 10.1080/13561820802379987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Amaker RJ, Brower KA, Admire DW. The role of the upper extremity neuromusculoskeletal evaluator at peace and at war. J Hand Ther. 2008;21:124–128. doi: 10.1197/j.jht.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Williamson GR, Webb C, Abelson-Mitchell N, Cooper S. Change on the horizon: issues and concerns of neophyte advanced health care practitioners. J Clin Nurs. 2006;15:1091–1098. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2005.01462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mathisen BA, Carey LB, O’Brien A. Incorporating speech-language pathology within Australian neonatal intensive care units. J Paediatr Child Health. 2012;48:823–827. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2012.02549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Anaf S, Sheppard LA. Lost in translation? How patients perceive the extended scope of physiotherapy in the emergency department. Physiotherapy. 2010;96:160–168. doi: 10.1016/j.physio.2009.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Davis S, Machen MS, Chang L. The beneficial relationship of the colocation of orthopedics and physical therapy in a deployed setting: Operation Iraqi Freedom. Mil Med. 2006;171:220–223. doi: 10.7205/milmed.171.3.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Humphreys A, Richardson J, Stenhouse E, Watkins M. Assessing the impact of nurse and allied health professional consultants: developing an activity diary. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19:2565–2573. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.MacKay C, Davis AM, Mahomed N, Badley EM. Expanding roles in orthopaedic care: a comparison of physiotherapist and orthopaedic surgeon recommendations for triage. J Eval Clin Pract. 2009;15:178–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2008.00979.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pearse E, Maclean A, Ricketts D. The extended scope physiotherapist in orthopaedic out-patients – an audit. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2006;88:653. doi: 10.1308/003588406X149183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rhon DI, Gill N, Teyhen D, Scherer M, Goffar S. Clinician perception of the impact of deployed physical therapists as physician extenders in a combat environment. Mil Med. 2010;175:305–312. doi: 10.7205/milmed-d-09-00099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bethel J. The role of the physiotherapist practitioner in emergency departments: a critical appraisal. Emerg Nurse. 2005;13:26–31. doi: 10.7748/en2005.05.13.2.26.c1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]