Abstract

PURPOSE

More than a decade ago the American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Family Physicians Foundation, American Board of Family Medicine, Association of Departments of Family Medicine, Association of Family Practice Residency Directors, North American Primary Care Research Group, and Society of Teachers of Family Medicine came together in the Future of Family Medicine (FFM) to launch a series of strategic efforts to “renew the specialty to meet the needs of people and society,” some of which bore important fruit. Family Medicine for America’s Health was launched in 2013 to revisit the role of family medicine in view of these changes and to position family medicine with new strategic and communication plans to create better health, better health care, and lower cost for patients and communities (the Triple Aim).

METHODS

Family Medicine for America’s Health was preceded and guided by the development of a family physician role definition. A consulting group facilitated systematic strategic plan development over 9 months that included key informant interviews, formal stakeholder surveys, future scenario testing, a retreat for family medicine organizations and stakeholder representatives to review strategy options, further strategy refinement, and finally a formal strategic plan with draft tactics and design for an implementation plan. A second communications consulting group surveyed diverse stakeholders in coordination with strategic planning to develop a communication plan. The American College of Osteopathic Family Physicians joined the effort, and students, residents, and young physicians were included.

RESULTS

The core strategies identified include working to ensure broad access to sustained, primary care relationships; accountability for increasing primary care value in terms of cost and quality; a commitment to helping reduce health care disparities; moving to comprehensive payment and away from fee-for-service; transformation of training; technology to support effective care; improving research underpinning primary care; and actively engaging patients, policy makers, and payers to develop an understanding of the value of primary care. The communications plan, called Health is Primary, will complement these strategies. Eight family medicine organizations have pledged nearly $20 million and committed representatives to a multiyear implementation team that will coordinate these plans in a much more systematic way than occurred with FFM.

CONCLUSIONS

Family Medicine for America’s Health is a new commitment by 8 family medicine organizations to strategically align work to improve practice models, payment, technology, workforce and education, and research to support the Triple Aim. It is also a humble invitation to patients and to clinical and policy partners to collaborate in making family medicine even more effective.

Keywords: primary health care, delivery of health care, health care economics and organizations, quality of health care, health services research

INTRODUCTION

The current state of health in the United States was recently summed up by the National Academies of Science: the US population leads shorter lives in poorer health compared with those in countries around the world.1 In fact, the United States continues to lose ground compared with other countries, and women in the Unites States are experiencing unprecedented declines in health outcomes. Despite spending more money per capita on medical care than any other country in the world, the United States has not developed effective and widespread systems to improve population health and prevent disease.2–4 In part, this crisis in US health is related to undervaluing primary care.5–10

It is well documented that health care systems based on primary care have better quality of care, better population health, greater equity, and lower cost.11–13 The effect of primary care is believed to be due to its local adaptability and the complex interaction of the tenets of primary care,5,14–17 which include the following:

Accessibility as the first contact with the health care system

Accountability for addressing a vast majority of personal health care needs (comprehensiveness)

Coordination of care across settings, and integration of care for acute and (often comorbid) chronic illnesses, mental health, and prevention, guiding access to more narrowly focused care when needed

Sustained partnership and personal relationships over time with patients known in the context of family and community

Among citizens, policy makers, and the healthcare industry, there is growing recognition of a needto move away from the status quo—a fragmented, depersonalized, unsustainable, and often ineffective US health care system—to a health care system that supports healthier people, families, and communities at a lower cost. Transformations in the way primary care is organized and delivered have shown early promise in meeting this need for integration, personalization, and sustainability.18,19 The patient-centered medical home has become a transitional step for an era of comprehensive primary care practice transformation.20,21 Family medicine has entered a period of experimentation and innovation in residency education and in primary care payment generally, and specifically in comprehensive payment models designed to support more robust primary care.22–28 These efforts to transform primary care, train new models of practice, and adequatelypay for more robust primary care are part of a larger effort among diverse stakeholders to achieve the Triple Aim—to create better health, better health care, and lower cost for patients and communities—and to create an important movement in which family medicine has an essential role.29

Foundational steps have been taken to transform primary care, and family medicine is now at an important crossroads—a moment of great collaborative opportunity for internal and external reform. The current challenge in widely implementing, disseminating, sustaining, and building on this early transformative work will require changes in the broader health care system, as well as partnerships with diverse stakeholders inside and outside health care. It will also require examination within family medicine about the changes needed in our own ways of working and contributing so that a new covenant with our patients and the public can be established.

Motivated by recent progress and an urgency to accelerate the pace of change, the 7 national family medicine organizations, joined by the American College of Osteopathic Family Physicians (ACOFP), issued a call to action and initiated a reexamination of how to best equip family medicine to take action to improve America’s health. This strategic planning process, called Family Medicine for America’s Health, was also fueled by growing recognition among policy makers that a strong primary care system is key to solving the US health care crisis and improving the nation’s health, including important recognition in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA). Family Medicine for America’s Health is also fueled by calls to make family medicine more comprehensive, particularly by integrating it with public health and mental health.1,7,30 This article outlines the new strategic plan, which was completed in the spring of 2014 and will launch the evolving efforts of the family medicine organizational agendas for the next 5 years, but with an important front-loading of effort, particularly with stakeholders. It also describes the impetus for this plan and the process for developing it, including important historical events and context. The implementation of the strategic plan and an accompanying communications initiative are underway, the first steps of which will be to refine the goals, tactics, and timelines for these high-level plans.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT: THE FUTURE OF FAMILY MEDICINE PROJECT

In 2003, the Keystone III conference was convenedto “examine the soul of the discipline of family medicine—to take stock of the present and grapple with the future of family practice.”31 This important meeting led to the commissioning of a series of studies, “to develop an objective understanding of the contemporary situation of family medicine in the United States based on unbiased quantitative and qualitative research.” Spurredby Keystone III, the Future of Family Medicine project (FFM), a collaboration of the 7 major family medicine organizations, sought to address how the discipline should change as a result of growing frustration among family physicians, confusion of the public about the role of family physicians, and persistent inequity and inefficiency in the US health care system.32 FFM aimed to renew the specialty of family medicine to “meet the needs of people and society in a changing environment.” FFM was guided by a series of questions that focused on defining the core attributes of the specialty, strategies for the future, and the leadership role of family medicine. One outcome of FFM was a fundamental concern that, “unless there are changes in the broader health care system and within the specialty, the position of family medicine in the United States may be untenable in a 10- to 20-year time frame.”32

FFM generated specific task forces that produced recommendations (Table 1). These recommendations were then translated into specific commitments taken up by each of the family medicine organizations. The recommendations led to important outcomes and successes: leadership of the patient-centered medical home effort; formation of the Patient Centered Primary Care Collaborative; important residency training demonstration projects and a willingness by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education to support education innovation; leadership in maintenance of certification and movement of these lifelong learning tools into residency training; a rapid uptake of electronic health records by family physicians; and focused work on advancing the science of family medicine and research advocacy. Many goals were not attained, however. Payment reform lagged behind practice transformation efforts as private and government payers were slow to adopt new payment models; production of family physicians and other primary care physicians declined sharply; electronic health records failed to evolve as information management tools or to facilitate population health; and a robust, national communication plan about the valueof family medicine was not implemented. There was a lack of specificity about what leadership meant in some FFM strategies that led to lack of ownership or implementation. Further, there was no clear family physician role definition.

Table 1.

Task Forces of Future of Family Medicine

| Task Force 1. Identify the core attributes of family practice, reform family practice to meet consumer expectations, and determine systems of care to be delivered by family practice33 |

| Task Force 2. Determine the training needed for family physicians to deliver core attributes and system services34 |

| Task Force 3. Ensure that family physicians deliver core attributes and system services throughout their careers35 |

| Task Force 4. Determine strategies for communicating the role of family physicians within medicine and health care, as well as to purchasers and consumers36 |

| Task Force 5. Determine family practice’s leadership role in shaping the future health care delivery system37 |

| Task Force 6. Report on financing the new model of family medicine38 |

In 2012, the unfinished work of FFM was a focus of the semiannual meeting of the 7 national family medicine organizations and led to a call for what became Family Medicine for America’s Health. Not long after, a group of young family medicine leaders supported by thePisacano Leadership Foundation also reflected on FFM saying, “now is the time to refocus attention on facets of [FFM ] not yet realized and to identify key aspects missing from [FFM].”39

Family Medicine for America’s Health: Convergence of Concern and Opportunity

A decade after FFM, the ACA and other prominent efforts to achieve the Triple Aim have led to national recognition of the central role that primary care and specifically family medicine must play in supporting this goal.40 There is overwhelming evidence that primary care’s key features are associated with better outcomes at lower cost, and that primary care’s essential functions need to be made more robust.7,41–46 There is also evidence that family medicine’s particular delivery of primary care is associated with better outcomes.11,47–49 The opportunity for family physicians and other leaders in primary care to step into this role, however, remains constrained by delays in the development of new payment models and other crucial elements of infrastructure support.50 Despite the mounting evidence of primary care’s impact, the last decade has seen continued expansion of the physician income gap between primary care and subspecialty incomes, which contributes to the limited medical student interest in primary care careers.51–56 This income gap also limits the ability of family physicians and other primary care physicians to invest in and sustain practice transformation.4,57–59 On the other hand, early innovations and primary care transformation projects have demonstrated successful ways to improve primary care effectiveness and efficiency and, if done well, to return joy to practice.60–63 This convergence of concern and opportunity has produced the key questions that drove the evolution of Family Medicine for America’s Health:

Core attributes: What are the core attributes of family medicine today—and what do they need to be in the future—for our profession to achieve the Triple Aim in the service of our patients in the context of the larger health care landscape?

Evolving ecosystem: How should family medicine change to respond to the challenges of an evolving health care system to best meet the needs of the nation?

Education: What changes are needed in the continuum of education (from medical school, through residency, and into continuing professional development) to train family physicians needed in the new health care system?

Communicating value: How does family medicine best communicate to relevant stakeholders the value and benefits of family medicine and the important role family physicians play in meeting the health care needs of the US population?

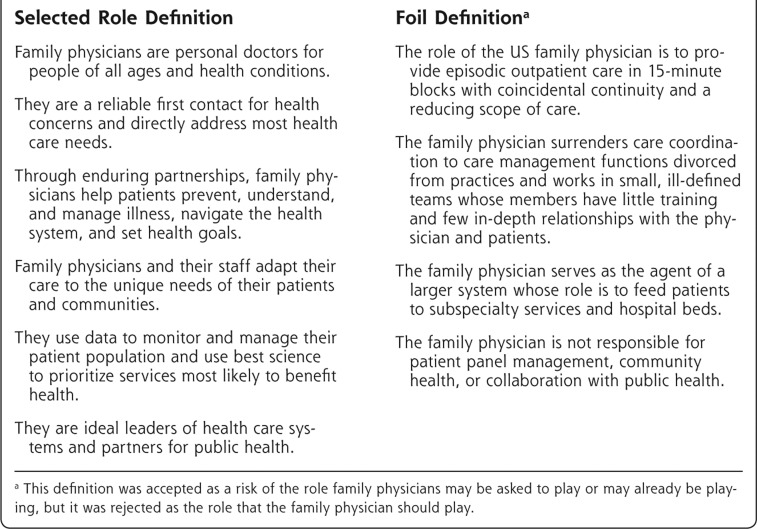

Family Medicine for America’s Health was preceded by a 3-month effort to create a 100-word role definition for the family physician (Figure 1) in the fall of 2012.64 The role definition process is detailed elsewhere, but it ultimately produced 2 definitions: an aspirational definition and a foil definition. The latter was crafted to emphasize “the role family medicine risked adopting without redirection”; it is not a desirable or beneficial role for the family physician.64

Figure 1.

Role definition and foil definition for the family physician.

METHODS

Upon completion of the role definitions, Family Medicine for America’s Health was launched, gestating 9 months to produce strategic and communication plans approved by all 8 organizations (the 7 original organizations plus the ACOFP) in May 2014. Consulting firms CFAR and APCO Worldwide were contracted toguide Family Medicine for America’s Health through the production of these plans. CFAR is a private management consulting firm that began as a research center at the Wharton School of Business (http://www.cfar.com/). APCO Worldwide is a global communication, stakeholder engagement, and business strategy firm (http://www.apcoworldwide.com/). The Family Medicine for America’s Health project was guidedby a steering committee and directly involved a core group, each of which comprised leaders from the 8 family medicine organizations. In addition, an insight group made up of students and residents and a young leader insight group were also engaged at key points to ensure that Family Medicine for America’s Health had multigenerational input.

CFAR Methods

In designing and facilitating the creation of family medicine’s strategic plan, CFAR used a systematic 3-phase planning process that it has developed over many years.

Phase 1 focused on creating a shared understanding of the current state of family medicine as a specialty. CFAR began with interviews of a wide range of family physicians and other stakeholders designed to bringto the surface issues critical to the current state ofthe specialty. These interviews informed the creation of a strategic assumptions and options questionnaire that asked survey respondents to describe issues of importance to family medicine and to provide guidance about its choices for the future. The resulting current-state analysis blended quantitative data about family medicine in the context of the current healthcare environment with the more qualitative data from CFAR’s interviews and survey. Taken together these data were used to explore strategic choices facing family medicine in the future.

In phase 2, CFAR facilitated an exploration of family medicine’s options for its future with a variety of different stakeholder groups. CFAR constructed 3 plausible scenarios for family medicine’s future, each featuring divergent strategic directions related to practice, payment, workforce, technology, research, and engagement of other health care professions, patients, and payers. Because health care is undergoing a great deal of rapid change, CFAR believed it was important for family medicine to explore multiple possible futures, but with an intention of identifying ways the specialty may need to adapt while staying true to its principles and chosen direction. This phase culminated in a strategy retreat, where internists, pediatricians, nurses, physician assistants, payers, patient advocates, family medicine residents, medical students, and family physicians from a variety of practice types, as well as academia, came together to evaluate the merits and challenges of the 3 scenarios. They also explored the risks that came with each before having to make final decisions. A secondary reason for the collection of stakeholders involved in the retreat was to test strategic options for the future with other groups that might be helpful allies in implementing the strategic plan.

In phase 3 of the project, CFAR met with the leadership of the 8 family medicine organizations to craft a single strategic plan that all could own as clearly stated commitments that family medicine’s leadership is making to patients and families, to family physicians, and to other health care professions.

The final part of phase 3 was to ensure the strategic objectives and commitments can be implemented by developing draft tactics and a structure for implementation that outlined roles and responsibilities. This final step created a bridge between strategy and implementation—a plan for the next phase of Family Medicine for America’s Health.

APCO Worldwide Study

In late 2013 and early 2014, APCO Worldwide interviewed 75 health care policy makers, 100 employers/purchasers, 75 health care payers, 800 patients, 400 physicians (250 family physicians, 150 other), and 300 residents and medical students, as well as 100 nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and other clinical team members. They asked each participant to rate the favorability of various physician specialties and other clinicians, to explain why they rated family physicians the way they did, and to compare physicians and clinicians for their impact on the health care system. They also asked them to rate family physicians’ effectiveness on a listof primary care characteristics, health care costs and utilization, work with other clinical team members, patient engagement and education, and technology use. APCO asked interview participants about the likelihood to choose or recommend a family physician and about their perceptions about family physicians’ authenticity, that is, whether their actions matched what they say they stand for. Participants were asked about attachment by means ofa series of questions about their understanding of family physicians’ capabilities, approachability, usefulness, and relevance; about their admiration of, identification with, and values shared with family physicians; about empowerment/confidence in health care resulting from having a family physician; and about pride in having a family physician. APCO asked whether family physicians added value to society and about family medicine’s perceived advocacy goals. Participants were asked about how family medicine should respond to changes in the health care system. Finally, participants were asked whether they had a family physician or other type of clinician. APCO also collected participant demographics for subanalyses.

RESULTS

Strategic Plan

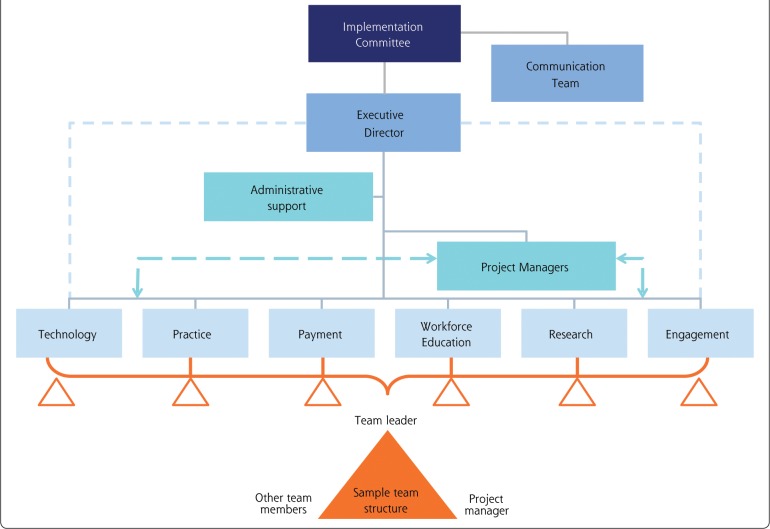

The strategic plan used the role definition that preceded Family Medicine for America’s Health as the basis for the expectations that patients should have of their family physician (Table 2). The core group recognized that this role definition was foundational but insufficient for describing the expectations that the public should have of its practices and the specialty. With CFAR’s help,the core group and steering committee further developed these expectations to guide the strategic planning that will come from the implementation plan (Tables 3 and 4). An implementation committee, composed of members of all 8 family medicine organizations, has been formed and has begun the task of implementation of Family Medicine for America’s Health (Figure 2), guided by the following 7 core strategies:

Family medicine’s leadership will collaborate with patients, employers, payers, policy makers, and other primary care professionals to show the value and benefits of primary care, as well as the contribution that family physicians make in meeting the health and health care needs of people throughout the United States.

Family medicine will work to ensure that every person in the United States understands the value of and has the opportunity to have a personal relationship with a trusted family physician or other primary care professional in the context of a medical home.

-

Family medicine will, in collaboration with our primary care partners, be accountable for increasing the value of primary care for the patients family physicians serve by putting into effect the following specific measures:

Lower the total cost of care for the patients family physicians serve

Continuously improve the health and quality of care of the patients family physicians serve

Continuously improve each patient’s experience of care as they define it, with an emphasis on access

Family medicine will collaborate with national stakeholders to reduce health disparities in the United States.

Family medicine will lead, through ongoing outcomes-based research, the continued evolution of the patient-centered medical home toensure that it is the best way to deliver comprehensive, patient-centered primary care to patients, families, and the communities family physicians serve.

Family medicine will work to ensure that the country has the well-trained primary care workforce it needs for the future through expansion and transformation of training from pipeline through practice.

To give patients the comprehensive and coordinated care and attention they deserve, family medicine commits to moving primary care reimbursement away from fee-for-service and toward comprehensive primary care payment as quickly as possible in coordination with its primary care colleagues.

Table 2.

What Patients Can Expect of a Family Physician

| Give patients the care they need when they are most vulnerable |

| Care for patients regardless of age and health conditions, and work to sustain an enduring and trusting relationship with them |

| Be each patient’s first contact for health concerns. Address all their health concerns, and resolve most of them |

| Help patients with preventing, understanding, and managing illness |

| Navigate the health system with patients, including coordinating with specialists and staying connected with patients before, during, and after time spent in a hospital |

| Set health goals that adapt to each patient’s needs as defined by them |

| With the care team, use data and best science to prioritize and coordinate services most likely to benefit patients’ health |

| Use technology to maintain and enhance access, continuity, and relationships, and to optimize patients’ care and outcomes |

Table 3.

What Patients Can Expect of Family Physicians’ Practices

| Provide the right care, at the right time, at the right cost |

| Ensure patients can be seen by their family physician or a member of the care team whenever needed |

| Assist patients with all of their health care needs |

| Coordinate patients’ care across settings; integrate care for acute and chronic illness, mental health and prevention; and guide access to specialist care when needed |

| Organize care within the care team to meet their patients’ needs and provide continuity of care across time |

| Use technology to maintain and enhance access, continuity, and relationships |

| Understand the effects of the community-level factors and social determinants of health on their patients’ well-being, and identify community resources available to meet their health needs |

| Care for patients in the context of their family and the ways in which the health of each family member affects the others |

Table 4.

What Patients Can Expect of the Discipline of Family Medicine

| Family medicine’s leadership will welcome collaboration with patients, employers, payers, policy makers, other primary care professionals, mental health clinicians, and public health to enhance the value and benefits of primary care, particularly the contribution that family physicians make, in meeting the health and health care needs of people throughout the United States |

| Family medicine will work to ensure that every person in the United States understands the value of and has the opportunity to have a personal relationship with a trusted family physician or other primary care professional in the context of a medical home |

Family medicine will, in collaboration with primary care partners, be accountable for increasing the value of primary care for the patients served, using specific measures to do the following:

|

| Family medicine will collaborate with national stakeholders to reduce health disparities in the United States |

| Family medicine will lead, through ongoing outcomes-based research, the continued evolution of the patient-centered medical home to ensure it is the best way to deliver comprehensive, patient-centered care to the patients, families, and the communities served |

| Family medicine will work to ensure that the country has the well-trained primary care workforce it needs for the future through expansion and transformation of training from pipeline through practice |

| To give patients the comprehensive and coordinated care and attention they deserve, family medicine commits to moving primary care reimbursement away from fee-for-service and toward comprehensive primary care payment as quickly as possible in coordination with its primary care colleagues |

Figure 2.

Implementation infrastructure of Family Medicine for America’s Health.

These 7 core strategies have been translated into 6 major tactics areas: technology, practice, payment, workforce education, research, and engagement. Six tactics teams will be formed to implement the tactics.As with FFM, the work will include external partners as well. It is recognized that family medicine cannot achieve meaningful reform without engaging other partners.

Each of the strategy tactics teams will include young physicians and physicians in small or solo practices. Family medicine will also look to engage residents and students, both of whom have responded well to education innovation and the resurgence of primary care. Trainees have the potential to be family medicine’s staunchest advocates even as they are the targets of our workforce strategies. Implementation of the strategic plan is anticipated to take at least 5 years.

Communication Plan

APCOWorldwide’s interviews across stakeholders led to a summary of findings that have guided their communication recommendations. These findings are summarized as follows:

Family physicians are viewed very favorably across all stakeholders, especially by patients.

Family physicians’ broad scope of knowledge, ability to treat entire families, and caring nature are key themes that define family physicians positively.

Family physicians are selected most frequently across every audience as the member of the primary care community who will have the biggest impact on the health care system.

Coordinating care, treating the whole person, and using technology to improve patient care are seen as the most exciting ways family physicians can capitalize on the new health care system.

At least 3 in 4 stakeholders across the audiences believe that family physicians should focus more on preventive and chronic care vs acute care.

Core strengths of family physicians are treating the whole person, being a patient advocate, and establishing patient rapport.

Key opportunities to strengthen reputation lie in serving as a health care resource advocate and providing cost-effective and affordable care.

Emotional dimensions important for family physicians are relevance—people find having a family physician useful and benefits them—and empowerment—family physicians help people to feel self-assured and confident about their health.

A campaign tone that helps demonstrate the pride that people feel about having a family physician will help strengthen the emotional connection to family physicians.

The communications campaign built around these findings was designed to address patients, the medical community, students, payers, and policy makers. The overall theme of the campaign will be Health is Primary, which resonated well with all groups. Health is Primary, meant to convey a linkage between health and primary care, implies that primary care is foundational to health even as it recognizes that health is key to well-being. Participants in the interviews believed that Health is Primary was a straightforward concept, easy to understand and agree with, and was an interesting play on words with primary care. Most felt that it conveyed an image of people involved in healthy activities, of healthy eating, and of happy people, with a positive outcome implied. One subspecialist reactedsaying, “If you have health, everything else follows.” A medical student said, “Health is foundational. It’s the base of the pyramid of life.”

The communication plan is anticipated to last at least 3 years, and it is designed both to reach an internal audience and to secure important external partnerships. The final communication plan has not been developed, but initial plans include a campaign launch, concurrent with the 2014 AAFP Assembly, that will announce campaign goals, kick off thought leadership and core campaign communications (website, print materials, mobile app for consumers), and provide resources for consumers. This launch will be followed by a city tour, with campaign events in 12 to 18 markets. The aim is to enlist local partners, drive coverage of campaign messages, brief national and local policy makers, and court corporate partners. There will also be a series of mini campaigns that focus on the 6 strategic plan themes.

DISCUSSION

The strategic and communication plans outlined here are part of a larger movement of which family medicine is only a part, but an essential part. This movement is about making US health care effective, equitable, sustainable, and linked to the social and environmental determinants that have a greater effect on the health of Americans than health care.

The components of Health is Primary: Family Medicine for America’s Health are designed to use the current wave of health reform to move the specialty of family medicine into position to best deliver on the Triple Aim. Family medicine was partially successful with FFM, but the difference now is that patients, payers, and policy makers are aligning in favor of improving the value they get from the US health care system. A decade ago, the United States was riveted by news that the nation had a “quality chasm” that killed nearly 100,000 people each year.65 A decade later, another landmark report from the Institute of Medicine reported that the United States is not only last among developed countries in health outcomes, but that women in the US are actually losing ground.1 Primary care, particularly family medicine, must ascend to its essential role, or the larger efforts are doomed to fail.

The first, if not the most difficult, community to convince will be ourselves. When the FFM report was written a decade ago, family medicine as a discipline was noted to have experienced an erosion in scope of practice.42,43 That erosion continues,66,67 fostered by the country’s dysfunctional payment system, and as a result, a more limited scope of practice has unfortunately been embraced by many practicing family physicians.68

It will be challenging to ask family physicians to consider expanding the services they provide and the settings they serve. Even if the desire to do so is there, many will need strong signals that this change will be rewarded by payers and patients.69 A recent study of innovative practices teaches us that much of the joy of practice is sapped when primary care physicians are doing tasks that keep them from doing what they are best trained to do.60 Family medicine becomes most effective, perhaps most enjoyable, when team members in the practice are working collaboratively at the top of their capabilities and training. Making primary care more robust is a major cognitive shift, and there are many good models to help us understand what it will look like.62 A change of this magnitude will be threatening and difficult for many, and family physicians must help each other to achieve these goals.

Family medicine is already experiencing a backlash from the larger health care system to the advancement of primary care as a necessary solution to failings in the US health system.47 Although challenging, this sign is good, because backlash means that the system itself is wrestling with the pressure to change. Even as family medicine makes its case, presenting evidence and pointing to improved outcomes, it also must look for ways to help the rest of American health care to see a path forward for themselves. Subspecialists and hospitals will need help understanding why they must transition to being cost centers and support systems for primary care and population health rather than being revenue centers at the top of the financial food chain.

The inherent value of a robust primary care system is to successfully reduce the need for more expensive and avoidable care through prevention, early treatment, and longitudinal care of chronic disease. Thus, the incentives in primary care run counter to those hospital systems that are sustained by the volume of patients which fill their beds. Family physicians who find themselves employed by hospital-based systems will face diverging incentives and loyalties if systems are supported by population-based payment models.

The last strategy of the strategic plan, and the most important, is that of a reformed payment model for primary care. Stand-alone fee-for-service produces over-utilization within the health care system and creates incentives in direct opposition to the role and function of family physicians.70 If primary care is intended to improve the health of the nation, a payment model is needed that incentivizes primary care physicians to maximize their relationship and effectiveness to the patients for whom they provide care. Such a payment model represents a substantial investment in primary care transformation. In our American model of health care, the United States currently spends less than 5% of the total health care dollar to support primary care.4 The Arkansas Surgeon General, Dr Joseph Thompson, recently told an audience that primary care receives only 2% of that state’s Medicaid spending.71 Rhode Island, on the other hand, mandated an increase in primary care spending from 5.4% to 8.0% between 2007 and 2011.72 The Rhode Island Insurance Commissioner reported that a 23% increase in primary care spending was associated with an 18% reduction in total spending—a 15-fold return on investment. The Commonwealth Fund modeling of maintenance of the 10% primary care incentive payment suggests a 6-fold return on total spending reduction.73 Other countries that spend more on maintaining a robust primary care infrastructure realize a slower rise in health care spending.45 It has been suggested that the United States should aim for primary care to reach 10% to 12% of total health care spending to have a maximum effect on reducing overall health care spending.4 Payment reform is critical to successful system reform. Without it, none of the core strategies of the plan will be resourced sufficiently to succeed, nor will the incentives of primary care be aligned with the desired outcomes of the Triple Aim.

Health is Primary: Family Medicine for America’s Health is now a $20 million commitment by the specialty to develop family physicians’ potential and to partner with diverse others to leverage that potential for the health of the American people. This combined cost estimate is for the strategic plan and communications campaign, and all the family medicine organizations have pledged substantial contributions to their budgets in meeting this target. It is an important investment in navigating a movement for health system change that family medicine did not create, but one that the discipline’s investment a decade ago definitely helped to stimulate. Even so, the money is less important than the commitments family medicine makes to change our practices, our communities, and our nation’s health care system. The outcomes of our effort will be measured in part by a number of factors:

Growth in the number of students choosing family medicine careers

Adoption of non–fee-for-service payment models by private and government payers that represent true investments in primary care as a larger part of health care spending while the total cost of care improves as a return on those investments

Expansion in the nation’s primary care capacity

Enhancement of family medicine practices to better use technology in delivering on the Triple Aim

A reversal of erosion of family medicine’s scope of practice and comprehensiveness

Improved satisfaction for family physicians and other members of the family medicine team

Improved satisfaction for patients in their health care experiences and relationships in family medicine

A Convergence of Concern and Opportunity

Ten years after FFM, family medicine is on stronger footing, but the US health care system is still undergoing changes needed to realize its full potential and viability. A decade ago, the most recent wave of opportunity for primary care had passed, and the specialty’s future was an open question. Family medicine is now perched atop a new wave of change that may have less chance of collapse. Unlike FFM, after which the nation saw the worst reduction in primary care workforce production in our nation’s history, Family Medicine for America’s Health is focused on how to ride a swell of enthusiasm and new policies that favor primary care. Eight family medicine organizations have made major financial and staffing commitments to long-term strategy and communication implementation. These organizations are open to welcoming other partners and are committed to helping the discipline adapt and serve. The stakes are high, but so is family medicine’s commitment—to our patients, our families, our communities, and our nation. Family medicine calls upon patients, government, policy makers, employers, payers, and others to join with us in moving from today’s inefficient and costly health care enterprise to a health care system based on family medicine and primary care, a system that does deliver on the Triple Aim.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr Sam Jones, Chair of the Family Medicine for America’s Health Steering Committee, Mal O’Conner and Chris Hugill of CFAR, and Ann Saybolt and Kirsten Thistle of APCO International. We would also like to thank the Family Medicine for America’s Health Core Group, Steering Committee, the Young Leader Insight Group, residents and students, and stakeholders for the considerable work and success that are reflected in this article.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors have a variety of potential conflicts of interest in that they are leaders in one or more family medicine organizations that may have competing interests. In addition to being leaders of family medicine organizations, many authors are also leaders in health care systems and academic centers. Authors have identified other potential conflicts of interest in their individual authorship forms. We have tried to mitigate potential conflicts by recruiting a broad authorship group, by holding all listed authors to a standard of meaningful contribution, and by subjecting the article to 12 external reviews.

References

- 1.National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. U.S. Health in International Perspective: Shorter Lives, Poorer Health: Panel on Understanding Cross-National Health Differences Among High-Income Countries. Washington, DC: National Acadamies Press; 2013 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woolf SH, Aron LY. The US health disadvantage relative to other high-income countries: findings from a National Research Council/Institute of Medicine report. JAMA. 2013;309(8):771–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Starfield B. Is US health really the best in the world? JAMA. 2000; 284(4):483–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Phillips RL, Jr, Bazemore AW. Primary care and why it matters for US health system reform. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(5):806–810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donaldson MS, Yordy KD, Lohr KN, Vanselow NA, eds. Primary Care: America’s Health in a New Era. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Macinko J, Starfield B, Shi L. The contribution of primary care systems to health outcomes within Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries, 1970–1998.Health Serv Res. 2003;38(3):831–865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Institute of Medicine. Primary Care and Public Health: Exploring Integration to Improve Population Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2012 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goroll AH. The future of primary care: reforming physician payment. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(20):2087, 2090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Starfield B. Primary care and equity in health: the importance of effectiveness and equity of responsiveness to people’s needs. Humanity Soc. 2009;33:56–73 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83(3):457–502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Starfield B, Shi L, Grover A, Macinko J. The effects of specialist supply on populations’ health: assessing the evidence. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;(Suppl Web Exclusives):W5-97–W5-107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baicker K, Chandra A. Medicare spending, the physician workforce, and beneficiaries’ quality of care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2004;W4 (Suppl Web Exclusives):W4-184-97. http://content.healthaffairs.org/cgi/reprint/hlthaff.w4.184v1?maxtoshow=&HITS=10&hits=10&RESULTFORMAT=&author1=baicker&andorexactfulltext=and&searchid=1&FIRSTINDEX=0&resourcetype=HWCIT. Accessed Jul 6, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Macinko J, Starfield B, Shi L. Quantifying the health benefits of primary care physician supply in the United States. Int J Health Serv. 2007;37(1):111–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Starfield B. Primary Care: Balancing Health Needs, Services, and Technology. Rev ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 15.McWhinney IR, Freeman T. Textbook of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stange KC, Nutting PA. Miller WL, et al. Defining and measuring the patient-centered medical home. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(6): 601–612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stange KC, Jaén CR, Flocke SA, Miller WL, Crabtree BF, Zyzanski SJ. The value of a family physician.J FamPract. 1998;46(5):363–368 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nielsen M, Langner B, Zema C, Hacker T, Grundy P. Benefits of Implementing the Primary Care Patient-Centered Medical Home: A Review of Cost & Quality Results. Washington, DC: Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative; 2012. http://www.pcpcc.org/sites/default/files/media/benefits_of_implementing_the_primary_care_pcmh.pdf. Accessed Jan 24, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phillips RL, Jr, Bronnikov S, Petterson S, et al. Case study of a primary care-based accountable care system approach to medical home transformation. J Ambul Care Manage. 2011;34(1):67–77. 10.1097/JAC.1090b1013e3181ffc1342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Academy for State Health Policy. Medical Home & Patient-Centered Care.2012; Project tracking site. http://www.nashp.org/med-home-map. Accessed Jan 19, 2013

- 21.Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative. Joint Principles of the Patient-Centered Medical Home. 2007. http://www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/practice_management/pcmh/initiatives/PCMH-Joint.pdf. Accessed Jan 24, 2013

- 22.Leach DC, Batalden PB. Preparing the personal physician for practice (P4): redesigning family medicine residencies: new wine, new wineskins, learning, unlearning, and a journey to authenticity. JABFM. 2007;20(4):342–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scherger JE. Preparing the personal physician for practice (P4): essential skills for new family physicians and how residency programs may provide them. JABFM. 2007;20(4):348–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Green LA, Jones SM, Fetter G, Pugno PA. Preparing the personal physician for practice: changing family medicine residency training to enable new model practice.Acad Med. 2007;82(12):1220–1227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carek PJ. The length of training pilot: does anyone really know what time it takes? Fam Med. 2013;45(3):171–172 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jain S, Shrank W. The CMS Innovation Center: delivering on the promise of payment and delivery reform. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(9):1221–1223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iglehart JK. Primary care update—light at the end of the tunnel? N Engl J Med. 2012;366(23):2144–2146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baron RJ, Davis K. Accelerating the adoption of high-value primary care—a new provider type under Medicare? N Engl J Med. 2014;370 (2):99–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stephens GG. Family medicine as counterculture. 1979. Fam Med. 1998;30(9):629–636 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Research Council. Improving the Quality of Health Care for Mental and Substance-Use Conditions: Quality Chasm Series. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Special Dedication Issue: The Keystone Papers: formal discussion papers from Keystone III. In: Green LA, Graham R, Stephens GG, Frey JJ, eds. Family Medicine. Vol 33 2001. http://www.stfm.org/FamilyMedicine/Vol33Issue4 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martin JC, Avant RF, Bowman MA, et al. The Future of Family Medicine Project Leadership Committe. The future of family medicine: a collaborative project of the family medicine community. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(Suppl 1): S3–S32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Task Force 1 Writing Group Green LA, Graham R, Bagley B, Kilo CM, Spann SJ, Bogdewic SP. Task Force 1. Report of the Task Force on Patient Expectations, Core Values, Reintegration, and the New Model of Family Medicine. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(suppl 1): S33–S50 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bucholtz JR, Matheny SC, Pugno PA, David A, Bliss EB, Korin EC. Task Force Report 2. Report of the Task Force on Medical Education.Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(suppl 1): S51–S64 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jones WA, Avant RF, Davis N, Saultz J, Lyons P. Task Force Report 3. Report of the Task Force on Continuous Personal, Professional, and Practice Development in Family Medicine. Ann Fam Med. 2004; 2(suppl 1): S65–S74 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dickinson JC, Evans KL, Carter J, Burke K. Task Force Report 4. Report of the Task Force on Marketing and Communications. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(suppl 1): S75–S87 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roberts RG, Snape PS, Burke K. Task Force Report 5. Report of the Task Force on Family Medicine’s Role in Shaping the Future Health Care Delivery System. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(suppl 1):S88–S99 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spann SJFuture of Family Medicine Task Force 6. Report on Financing the New Model of Family Medicine. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(suppl 3):S1–S21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Doohan NC, Duane M, Harrison B, Lesko S, DeVoe JE. The future of family medicine version 2.0: reflections from Pisacano Scholars. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine: JABFM. 2014;27(1): 142–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fleming C. Berwick brings the ‘Triple Aim’ to CMS. Health Affairs Blog.2010. http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2010/09/14/berwick-brings-the-triple-aim-to-cms/

- 41.Auerbach DI, Chen PG, Friedberg MW, et al. Nurse-managed health centers and patient-centered medical homes could mitigate expected primary care physician shortage. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(11):1933–1941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Phillips RL, Jr, Bazemore AM, Peterson LE. Effectiveness over efficiency: underestimating the primary care physician shortage. Med Care. 2014;52(2):97–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen PG, Mehrotra A, Auerbach DI. Do we really need more physicians? Responses to predicted primary care physician shortages. Med Care. 2014;52(2):95–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leleu H, Minvielle E. Relationship between longitudinal continuity of primary care and likelihood of death: analysis of national insurance data. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e71669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kringos D, Boerma W, Bourgueil Y, et al. The strength of primary care in Europe: an international comparative study. Br J GenPract. 2013;63(616):e742–e750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roetzheim RG, Gonzalez EC, Ramirez A, Campbell R, van Durme DJ. Primary care physician supply and colorectal cancer. J FamPract. 2001;50(12):1027–1031 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Phillips RL, Dodoo MS, Green LA, et al. Usual source of care: an important source of variation in health care spending. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28(2):567–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Campbell RJ, Ramirez AM, Perez K, Roetzheim RG. Cervical cancer rates and the supply of primary care physicians in Florida. Fam Med. 2003;35(1):60–64 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chetty VK, Culpepper L, Phillips RL, Jr, et al. FPs lower hospital readmission rates and costs. Am Fam Physician. 2011;83(9):1054–1054 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Through the Looking Glass: A New Perspective on Population Management. UHC Member Board of Directors Meeting. 2014. https://www.uhc.edu/19657

- 51.Bodenheimer T. Primary care—will it survive? N Engl J Med. 2006; 355(9):861–864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bodenheimer T, Pham HH. Primary care: current problems and proposed solutions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(5):799–805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Landon BE, Roberts DH. Reenvisioning specialty care and payment under global payment systems.JAMA. 2013;310(4):371–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen C, Petterson SM, Phillips RL, Mullan F, Bazemore AW, O’Donnel SD. Towards graduate medical education accountability: measuring the outcomes of GME institutions. Acad Med. In press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kruse J. Income ratio and medical student specialty choice: the primary importance of the ratio of mean primary care physician income to mean consulting specialist income. Fam Med. 2013;45(4):281–283 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Council on Graduate Medical Education. 20th Report: Advancing Primary Care. Rockville, MD: Department of Health and Human Services; 2010: http://www.hrsa.gov/advisorycommittees/bhpradvisory/cogme/Reports/twentiethreport.pdf. Accessed May 8, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Goroll A, Berenson R, Schoenbaum S, Gardner L. Fundamental reform of payment for adult primary care: comprehensive payment for comprehensive care. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(3):410–415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Goroll A, Bagley B, Harbrecht M, Kirschner N, Kenkeremath N. Payment Reform to Support High-Performing Practice. A report from the Payment Reform Task Force. Washington, DC: Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative; 2010. http://www.pcpcc.org/sites/default/files/media/paymentreformpub.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 59.Robert Graham Center. The Patient Centered Medical Home: History, Seven Core Features, Evidence and Transformational Change. Washington, DC: The Robert Graham Center; 2007. http://www.graham-center.org/online/etc/medialib/graham/documents/publications/mongraphs-books/2007/rgcmo-medical-home.Par.0001.File.tmp/rgcmo-medical-home.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sinsky CA, Willard-Grace R, Schutzbank AM, Sinsky TA, Margolius D, Bodenheimer T. In search of joy in practice: a report of 23 high-functioning primary care practices. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(3):272–278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shipman SA, Sinsky CA. Expanding primary care capacity by reducing waste and improving the efficiency of care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(11):1990–1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bodenheimer T, Ghorob A, Willard-Grace R, Grumbach K. The 10 building blocks of high-performing primary care.Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(2):166–171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Maeng DD, Graham J, Graf TR, et al. Reducing long-term cost by transforming primary care: evidence from Geisinger’s medical home model. Am J Manag Care. 2012;18(3):149–155 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Phillips RL, Brundgardt S, Lesko SE, et al. The future role of the family physician in the United States: a rigorous exercise in definition. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(3):250–255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Berwick DM. A user’s manual for the IOM’s ‘Quality Chasm’ report. Health Aff (Millwood). 2002;21(3):80–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Phillips WR, Haynes DG. The domain of family practice: scope, role, and function. Fam Med. 2001;33(4):273–277 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bazemore AW, Petterson S, Johnson N, et al. What services do family physicians provide in a time of primary care transition? The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine: JABFM. 2011;24(6):635–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Petterson S, Bazemore AW, Phillips RL, et al. Rewarding family medicine while penalizing comprehensiveness? Primary care payment incentives and health reform: the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA). The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine: JABFM. 2011;24(6):637–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Goldberg DG, Mick SS, Kuzel AJ, Feng LB, Love LE. Why do some primary care practices engage in practice improvement efforts whereas others do not? Health Serv Res. 2013;48(2 Pt 1)(2pt1):398–416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schroeder SA, Frist W. Phasing out fee-for-service payment. NEJM. 2013;368(21):2029–2032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Thompson J. Arkansas’ innovative approach to Medicaid expansion. Keynote address at: 10th Annual AAMC Health Workforce Research Conference. Washington, DC. May 1, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 72.Health Insurance Commissioner State of Rhode Island. Primary Care Spending in Rhode Island: Health Insurer Compliance & Initial Policy Effects. Office of the Rhode Island Health Insurance Commissioner; September, 2012. http://www.ohic.ri.gov/documents/Insurers/Reports/2012%20Primary%20Care%20Spend/Primary%20Care%20Report_FINAL.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 73.Reschovsky JD, Ghosh A, Stewart K, Chollet D. Paying more for primary care: can it help bend the Medicare cost curve? Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2012;March;5:1–14, 1–12 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]