Abstract

Patient: Male, 50

Final Diagnosis: Intracranial hemorrhage

Symptoms: —

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: Craniotomy

Specialty: Oncology

Objective:

Adverse events of drug therapy

Background:

Combination therapy with BRAF V600E inhibitor dabrafenib and MEK inhibitor trametinib significantly improves progression-free survival of patients with BRAF V600-positive metastatic melanoma, but their use can be associated with life-threatening toxicities. We report the case of a patient receiving dabrafenib and trametinib for metastatic melanoma who developed intracranial hemorrhage while on therapy.

Combination therapy with dabrafenib and trametinib improves progression-free survival of patients with BRAF V600-positive metastatic melanoma. Nevertheless, it is associated with an increased incidence and severity of any hemorrhagic event. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of intracranial hemorrhage with pathological confirmation.

Case Report:

We present the case of a 48-year-old man with metastatic melanoma of unknown primary site. He had metastases to the right clavicle, brain, liver, adrenal gland, and the right lower quadrant of the abdomen. He progressed on treatment with alpha-interferon. He was found to have a 4.5-cm mass in the left frontotemporal lobe and underwent gross total resection followed by adjuvant CyberKnife stereotactic irradiation. He was subsequently started on ipilimumab. Treatment was stopped due to kidney injury. He was then placed on dabrafenib and trametinib. He returned for follow-up complaining of severe headache and developed an episode of seizure. MRI showed a large area of edema at the left frontal lobe with midline shift. Emergency craniotomy was performed. Intracranial hemorrhage was found intra-operatively. Pathology from surgery did not find tumor cells, reported as organizing hemorrhage and necrosis with surrounding gliosis; immunohistochemistry for S100 and HMB45 were negative.

Conclusions:

This case demonstrates the life-threatening adverse effects that can be seen with the newer targeted biological therapies. It is therefore crucial to maintain a high index of suspicion when patients on this combination therapy present with new neurologic symptoms.

MeSH eywords: Drug-Related Side Effects and Adverse Reactions, Intracranial Hemorrhages, Melanoma

Background

Combination therapy with BRAF V600E inhibitor dabrafenib and MEK inhibitor trametinib significantly improves progression-free survival of patients with BRAF V600-positive metastatic melanoma [1], but they can be associated with life-threatening toxicities. We report the case of a patient receiving dabrafenib and trametinib for metastatic melanoma who developed intracranial hemorrhage while on therapy.

Case Report

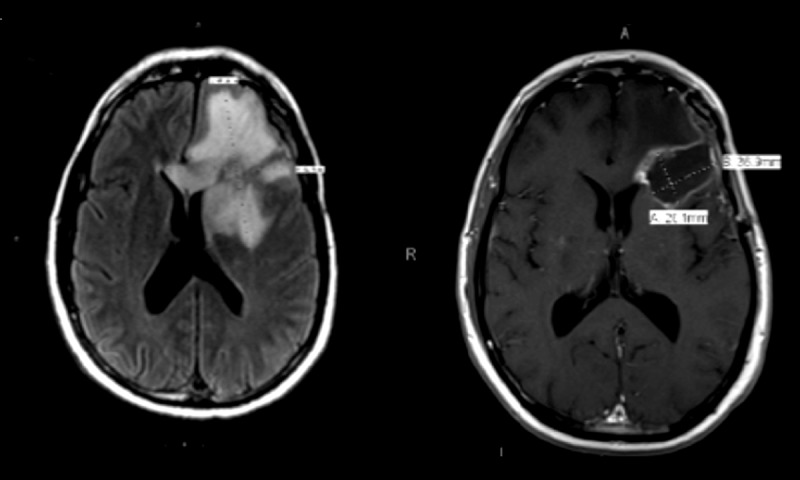

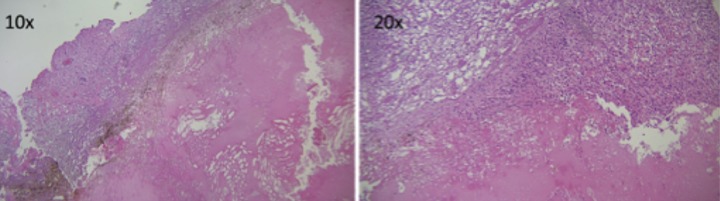

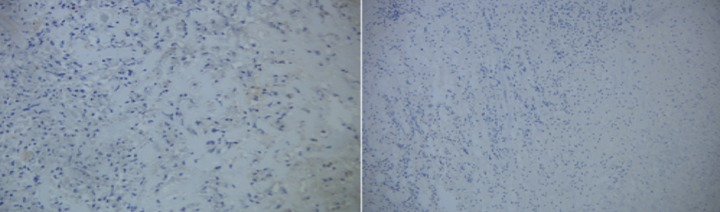

A 48-year-old man initially presented with a right clavicular node in 2001; pathology revealed metastatic melanoma. The primary site was unknown. He proceeded to have 1 full year of treatment with alpha-interferon. He presented in July 2013 with headaches and a CT of the brain revealed a 4.5-cm mass in the left frontotemporal lobe. He underwent gross total resection, with pathology demonstrating metastatic melanoma. He subsequently underwent adjuvant CyberKnife stereotactic irradiation. A PET scan at this time showed disease in the liver, left adrenal gland, and the right lower quadrant of the abdomen. He was started on treatment with ipilimumab in September 2013, which was stopped in October 2013 after 1 dose due to non-resolving kidney injury. He was then started on dabrafenib and trametinib in the same month. He reported mild nausea, vomiting, and fatigue with the initiation of targeted therapy. A PET scan in January 2014 showed post-surgical changes within the brain, interval improvement in hypermetabolic activity within the left adrenal and right lower quadrant mass, and heterogeneous liver uptake without focal area of hypermetabolism. There was a new hypermetabolic focus within the right distal tibia and a soft tissue lesion within the left gluteal muscle. MRI of the right lower extremity demonstrated a 4.4×1.6×1.0 cm intramedullary lesion in the distal tibial diaphysis, with imaging findings suggesting osteonecrosis or cartilaginous tumor. The lesion did not have the typical imaging characteristics of metastatic melanoma. In February 2014, he returned for follow-up, complaining of severe, new left frontal headache. He developed an episode of witnessed seizure at the office and was sent for an emergent MRI of the brain. Non-contrast MRI was performed due to impaired kidney function. The MRI showed a large area of edema in the left frontal lobe, with midline shift (Figure 1). Emergency craniotomy was performed and intracranial hemorrhage was found intra-operatively. Pathology from surgery did not find tumor cells, reported as organizing hemorrhage and necrosis (Figure 2) with surrounding gliosis. Immunohistochemistry is often used as an aid in the diagnosis of melanoma. S-100 remains the most sensitive marker of melanocytes. S-100 and the more specific HMB45 are the most frequently used antibodies in formulating a diagnosis of melanoma [2]. Immunohistochemistry for S100 and HMB45 were negative in our patient (Figure 3). The patient regained full neurologic function post-operatively. A repeat MRI of the brain a month later demonstrated interval resolution of blood products.

Figure 1.

Significant brain edema in the left frontal lobe, measuring 8.7 cm in AP diameter and 6.8 cm in transverse diameter, with a left-to-right midline shift of 2 mm. Post-operative MRI showing interval resolution of blood product and improvement in surrounding vasogenic edema.

Figure 2.

A 2×1×0.1 cm surgical specimen was submitted for histology. Multiple levels, including deeper sections, were evaluated as follows: 2 levels were evaluated during intra-operative consult (frozen section) and 3 levels were evaluated from the paraffin section. An additional 2 levels were stained negative for S100 and HMB45.

Figure 3.

A second 1.5×0.8 cm surgical specimen was submitted for histology. Four levels, including deeper sections, were evaluated microscopically. An additional 2 levels were stained negative for S100 and HMB45.

Discussion

Dabrafenib (BRAF inhibitor) and trametinib (MEK inhibitor) are approved for use as monotherapies and in combination at full monotherapy doses in BRAF-mutant metastatic melanoma.

Bleeding is an uncommon adverse effect, but the incidence and severity of any hemorrhagic event may be increased in combination therapy. In the initial clinical trial that investigated the combination of dabrafenib and trametinib, intracranial or gastric hemorrhage occurred in 5% (3/55) of patients in the combined therapy group, compared with none of the 53 patients treated with dabrafenib as a single agent [1]. Intracranial hemorrhage was fatal in 2 (4%) patients receiving the combination of dabrafenib and trametinib. Neither of the patients had pathologic examination of the hemorrhagic lesions, and this could have been due to brain metastases. This event was not considered to be related to the study drugs.

In our case report, the temporal relationship to dabrafenib and trametinib and the pathological examination of the brain suggest the hemorrhage may have been related to the drug(s). While it is possible that our patient may have had a small brain metastasis that bled and was the cause of the cerebral hemorrhage, no evidence of tumor was seen on pathological review of the brain lesion; there was only evidence of gliosis, most likely from the prior radiation therapy. Thus, the cerebral hemorrhage was most likely not due to tumor cells. Dabrafenib and/or trametinib were probably the cause of the cerebral hemorrhage. Therefore, clinicians should be aware of this rare but serious and potentially life-threatening adverse effect.

The mechanism behind these hemorrhagic events remains unclear. It is known that dabrafenib can penetrate farther into the brain than vemurafenib, another BRAF inhibitor [3] and dabrafenib has demonstrated activity in melanoma metastatic to the brain [4]. It is possible that the risk factors may include prior brain surgery and/or radiation therapy to the brain, as in our patient.

Conclusions

It is therefore crucial to maintain a high index of suspicion when patients on this combination therapy present with new neurologic symptoms.

These targeted therapies produce major responses, but drug resistance develops in virtually all patients and investigations are underway to circumvent this.

References:

- 1.Flaherty KT, Infante JR, Daud A, et al. Combined BRAF and MEK inhibition in melanoma with BRAF V600 mutations. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1694–703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1210093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruiter DJ, Brocker EB. Immunohistochemistry in the evaluation of melanocytic tumors. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1993;10:76–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mittapalli RK, Vaidhyanathan S, Dudek AZ, Elmquist WF. Mechanisms limiting distribution of the threonine-protein kinase B-RAF (V600E) inhibitior dabrafenib to the brain: implications for the treatment of melanoma brain metastases. J Pharmacol ExpDTher. 2013;344(3):655–64. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.201475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Azer MW, Menzies AM, Haydu LE, et al. Patterns of response and progression in patients with BRAF-mutant melanoma metastatic to the brain who were treated with dabrafenib. Cancer. 2014;120(4):530–36. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]