Abstract

A sample of 189 Mexican-heritage seventh grade adolescents reported their substance use, while one of the child’s parents reported parent’s acculturation and communication, involvement, and positive parenting with his or her child. Higher levels of parental acculturation predicted greater marijuana use, whereas parent communication predicted lower cigarette and marijuana use among girls. A significant parent acculturation by parent communication interaction for cigarette use was due to parent communication being highly negatively associated with marijuana use for high acculturated parents, with attenuated effects for low acculturated parents. A significant child gender by parent acculturation by parent positive parenting interaction was found. For girls, positive parenting had a stronger association with lower cigarette use for high acculturated parents. For boys, positive parenting had a stronger association with reduced cigarette use for low acculturated parents. Discussion focuses on how acculturation and gender impact family processes among Mexican-heritage adolescents.

Keywords: acculturation, Mexican American adolescents, parenting, substance use

INTRODUTION

Parent Acculturation and Practices Effects on Substance Use

Mexican-heritage youth constitute the largest Latino adolescent subgroup within the United States, and they constitute the majority of out-of-school Latino adolescents (U.S. Census Bureau 2011). There exists only a modest understanding of the sociocultural processes, such as acculturation and family factors, that influence Latino youths’ use of alcohol and other drugs (Marsiglia, Kulis, Husseini, Nieri, & Becerra, 2010). Currently, Latino youth consistently report higher rates of alcohol and other drug use compared with youth from other ethnic backgrounds (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2008). In addition, Latino youth in eighth grade report greater frequencies of alcohol and illicit drug use (with the exception of amphetamines) compared with their Anglo, non-Hispanic counterparts (Johnston et al., 2008). The influences of acculturation also need to be considered. For example, data from the Add Health study indicate that first-generation immigrant Mexican and other Latino adolescents report lower alcohol use rates (6.3%) compared with second-generation (11.6%) or third-generation (7.5%) Latino youths (Hussey et al., 2007).

The current article reports the results of a study of Mexican and Mexican American parent-adolescent dyads, examining the effects of parental reports of their communications with their child, their involvement with this child, and their positive parenting because these factors affect their child’s substance use behaviors. These relationships are considered within the context of the parent’s level of acculturation. These adolescent Latino youths are at a stage of development where family influences are still strong (Tobler & Komro, 2010).

Ecodevelopmental Theory

The ecodevelopmental framework reported by Coatsworth et al. (2002) emphasizes the primary role that families play in the socialization of children, the multiple social contexts beyond the family that influence development, the interrelations among contexts, and the changing nature of these contexts and relations over time and how these elements heighten or decrease risk for the development of psychopathology. Ecodevelopmental theory proposes that the social domains for human development can be represented by a set of nested structures, organized into microsystems (family, school, peers), mesosystems (parent-school or parent-peer relationships), and macrosystems (culture or political climate). In this ecodevelopmental approach, acculturation effects are understood in terms of their interactions with processes in each of the nested ecological systems (Coatsworth et al., 2002). It is clear that the emphasis on the family is fundamental in interventions targeting such youth regarding substance use/abuse. Accordingly, the current study focuses on identifying the influences of parental acculturation and parenting factors because these may influence substance use behaviors in these Latino adolescents.

Parenting Practices and Substance Use

Studies have shown that certain parenting practices are significant predictors of adolescent substance use (Cota-Robles & Gamble, 2006; Pokhrel, Unger, Wagner, Ritt-Olson, & Sussman, 2008; Tobler & Komro, 2010) and that parenting remains a primary source of influence of adolescent behaviors (Steinberg, 2001). The phrase parenting practices refers to the goal-directed methods and styles of parenting that parents perform as an integral part of their parental duties (Darling & Steinberg, 1993). Particular aspects of parenting practices (e.g., parenting styles, parental communication about family rules and discipline, and parental closeness, support, and discipline) have been shown to influence youth substance use (Alvarez, Martin, Vergeles, & Martin, 2003; Barber, Stolz, & Olsen, 2005; Cleveland, Gibbons, Gerrard, Pomery, & Brody, 2005; Newman, Harrison, Dashiff, & Davies, 2008). Effective parental discipline and parental warmth are both specific aspects of parenting practices that influence the child’s psychological and social adjustment (Barber et al., 2005), as does parental monitoring and the quality of parent-child communications (Cota-Robles & Gamble, 2006; Pokhrel et al., 2008; Tobler & Komro, 2010). In addition to these positive aspects of parenting, poor and ineffective aspects of parenting also exert a significant influence youth behaviors. For example, lack of discipline, lack of parental monitoring (Gorman-Smith, Tolan, & Henry, 2000), and overly permissive parenting (Darling & Steinberg, 1993) have been linked to maladjustment and negative behavioral outcomes during adolescence. Parental influences are important factors that affect youth behaviors and their development throughout adolescence and into early adulthood, despite the adolescent’s growing orientations toward their peers (Collins & Laursen, 2004).

Parent Communication

Parent communication can be thought of as an important part of monitoring the child’s behaviors, and prior research has shown that better parent-child communication (Fang, Schinke, & Cole, 2009; Martyn et al., 2009; Pantin et al., 2009; Tobler & Komro, 2010) serves as a protective factor against substance use behaviors among Hispanic adolescents. For example, Tobler and Komro (2010) found that Hispanic youths who are exposed to low levels of parental monitoring and limited communications were at a significantly greater risk for engaging in alcohol and marijuana use during the past year and month and at a greater risk of having ever smoked a cigarette.

Parent Involvement

Similarly, Smith and Krohn (1995) found that level of parent-child involvement, defined as extent of parent-child communications and as amount of time that the youth spends with his or her parents, exhibited a significant negative association with delinquency. This effect was observed for Hispanic youths, although not for Anglo and African American youths. The specific effects of parent involvement, independent of communication and monitoring, are rarely studied, so whether such involvement by itself acts as a protective factor against adolescent substance use is debatable. In terms of comparing the effects of parent communication, parent involvement, and parent positive parenting, a review of the literature by Ryan, Jorm, and Lubman (2010) concluded that greater parent communication and support, but not involvement, were associated with reduced alcohol use in adolescents.

Positive Parenting

Youths who feel emotionally connected with their parents are more likely to actively avoid disappointing them (Cernkovich & Giordano, 1987) by engaging in delinquent behaviors. In addition, the positive emotional attachment that exists between parents and their children may also increase voluntary time that they spend together, thereby decreasing opportunities for youth delinquency. A specific aspect of parenting that may facilitate emotional attachment and the enforcement of discipline is the use of positive reinforcement; however, whether this aspect of parenting specifically acts to reduce problem behaviors in children is controversial, with some studies finding significant effects (e.g., Coombs & Landsverk, 1988) and others finding no effects (e.g., Tildesley & Andrews, 2008). A recent intervention study with Mexican American adolescents (Gonzales et al., 2012) found that boosting such parental positive reinforcement mediated program effects in reducing adolescent problem behaviors.

Acculturation and Substance Use

Acculturation has been defined as an ongoing process through which people from one culture adjust and adapt to another culture, including the social and psychological exchanges that take place when there is continuous contact and interaction between individuals from different cultures (Berry, Phinney, Sam, & Vedder, 2006). Recently immigrated Mexican Americans and their children need to cope with a variety of stressors as they adjust to their new communities. During the acculturation process, there is typically socialization into the host dominant culture and a desire to become a part of the new culture. At the same time, there are pressures and desires to retain one’s identity from one’s culture of origin (Berry et al., 2006; Marsiglia, Kulis, Wagstaff, Elek, & Dran, 2005). In addition to cultural changes, this process typically involves changes in attitudes and behaviors resulting from continuous first hand contact with elements of the new cultural environment (Berry, 2006; Redfield, Linton, & Herskovits, 1936).

Several studies have shown that greater levels of acculturation are associated with greater substance use in Mexican/Latino American adolescents (Epstein, Doyle, & Botvin, 2003; Gil, Wagner, & Vega, 2000; Myers et al., 2009; Unger et al., 2000, 2006). These studies utilized unidimensional measures of acculturation that examined English language use, percentage of peers/friends from other ethnic groups, years in the United States, or lack of adherence to values of Latino societies. Greater acculturation, as indicated by English language acquisition (frequency of use and linguistic proficiency) (Marin & Gamba, 1996), has been associated with higher levels of risk for substance use among some Mexican-heritage youth (Marsiglia, Kulis, Hussaini, Nieri, & Becerra, 2010). In terms of acculturation, English language acquisition may introduce and reinforce behaviors that are perceived to be acceptable by the mainstream U.S. culture, such as girls’ drinking, while introducing value conflicts with the culture of origin (Gilbert & Cervantes, 1986; Vega, Zimmerman, Warheit, Apospori, & Gil, 1997). In addition, English language acquisition may increase one’s acculturation stress as the youth attempts to resolve conflicting cultural issues. As a consequence, this acculturation stress may be maladaptively dealt with through drug use (Gil, Wagner, & Vega, 2000; Kulis, Marsiglia, & Nieri, 2009).

Gender, Parenting Practices, and Substance Use

Gender differences are an important factor in understanding substance use (Kulis, Yabiku, Marsiglia, Nieri, & Crossman, 2007; Dakof, 2000; Ellis, O’Hara, & Sowers, 2000; Freshman & Leinwand, 2000) and are key in understanding social phenomenon, such as drug offers and the resistance process (Moon, Hecht, Jackson, & Spellers, 1999). Both biological and socially constructed gender differences affect the developmental trajectory of adolescents, highlighting the unique risk and protective factors that lead to substance use (Guthrie & Low, 2000; The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse [NCASA], 2003).

Although girls progress more slowly than boys to drug use initiation, once girls begin to use, they progress faster to addiction than boys when using the same amount of substances (Kauffman, Silver, & Poulin, 1997; NCASA, 2003; Schinke, Fang, & Cole, 2008). On the other hand, recent data from the Monitoring the Future (Johnston et al., 2011) study indicate that although adolescent boys continue to report higher levels of illicit drug use than girls, adolescent girls have generally caught up with boys for alcohol and cigarette use. For example, Schinke, Fang, and Cole’s (2008) literature review suggested that adolescent girls are beginning to surpass adolescent boys in their substance use. Among eighth and tenth graders, girls drank more than their male counterparts, and girls were also more likely than boys to use inhalants and stimulants. Girls started smoking at younger ages, and they subsequently smoked more regularly than boys.

In turn, Cota Robles and Gamble (2006) also noted the importance of the effects of gender roles as possibly moderating the influence of Mexican American parents’ parenting practices. Hispanics who endorse traditional Hispanic and Mexican cultural values have been found to endorse more conventional attitudes toward gender roles, as contrasted with Hispanics who hold the more modern cultural values prevalent within mainstream U.S. culture (Castro, Stein, & Bentler, 2009; Kulis, Marsiglia, & Nagoshi, 2010). These conventional gender values are particularly evident among Mexican and Mexican American parents and tend to erode with increasing acculturation toward the more egalitarian gender role values of the dominant U.S. culture (Castro & Coe, 2007). The conventional belief that girls are more vulnerable and in greater need of protection (Archer & Lloyd, 2002) may prompt Hispanic parents to provide greater supervision of girls than boys, which in turn would be expected to increase the effect of parenting practices for girls compared with boys. Voisine, Parsai, Marsiglia, Kulis, and Nieri (2008) noted how Mexican American girls who are raised in a culture of traditional marianismo are taught that they have obligations to their home and family that often serve to restrict their social encounters. It would be expected that girls who live under these cultural expectations would experience a greater degree of effective parental control and low permissiveness because their social interactions are more limited to family and close friends, given the cultural and gender role expectations that emphasize the girl’s obligations to fulfill duties within the home and maintain nurturing of interpersonal relationships (Archer & Lloyd, 2002).

There may also be gender differences in the influences of parenting practices on delinquency and substance use. Cota-Robles and Gamble (2006) studied the roles of parental monitoring and parent-adolescent attachment in reducing the risks of delinquency among Mexican American youths and found that these parent-adolescent factors were associated with lower risks of youth delinquency. In Cota-Robles and Gamble’s study, gender differences moderated the relationship between mother-adolescent attachment and delinquency, such that this attachment was associated with a lower risk of delinquency among boys but not among girls. The effect of gender in moderating the influence of parenting practices on problem behaviors in Mexican American youth may be due to traditional gender role differences that promote more of a family orientation in girls than in boys (Kulis et al., 2010).

Parenting Practices, Acculturation, and Substance Use

Several studies have suggested that acculturation to American values and practices in Mexican American adolescents is related to problematic family functioning (Gil et al., 2000), behavioral problems (Ramirez et al., 2004), and substance use (Epstein, Botvin, & Diaz, 2001). Several researchers have proposed that one of the mechanisms by which acculturation may increase the risk for problem behaviors, including substance use, in immigrant-origin adolescents involves the adoption of American values and practices (Fosados et al., 2007; Sullivan et al., 2007). A theme that emerges from this research literature is that the acculturation of Hispanic youth, particularly a form of acculturation that leads to an assimilated rather than bicultural identity, tends to result in a reduction of the traditional values of familismo (Chun & Akutsu, 2003) and its family bonding, which may operate as a protective mechanism among Latino parents and their children. By contrast, bicultural adolescents— those who identify with both a maintain heritage and its culture practices while also identifying with their native cultural practices—report having the highest levels of parental involvement, positive parenting, and family support. This traditional family orientation tends to be accompanied by higher levels of parental monitoring and parental involvement with children (Denner, Kirby, & Coyle, 2001), which can be protective against substance use (Marsiglia, Parsai, & Kulis, 2009).

Schwartz, Montgomery, & Briones (2006) discussed the parent-youth conflicts that emerge among Hispanic adolescents in the presence of the conservative traditional values inculcated by the Hispanic youth’s parents, in contrast with the permissive modernistic values that are endorsed by the Hispanic youth’s U.S.-born peers. The process of acculturation, and its differential patterns of change between Hispanic parents and their children, may predispose Hispanic families to conflict situations, communication difficulties, and the erosion of the importance of Hispanic family ties (Gil et al., 2000). Among Hispanic families, some consequences of these acculturative conflicts include youth behavioral problems and negative mental health outcomes (Berry et al., 2006; Fosados et al., 2007; Sullivan et al., 2007). Among Hispanic parents who immigrate as adults into U.S. ethnic enclaves, the acquisition and adoption of American cultural practices may not appear as a foremost priority and may not occur at all (Schwartz, Montgomery, & Briones, 2006). Under these forms of acculturation change, whether family functioning is compromised and whether adolescents from these families exhibit problematic behaviors may depend on the extent to which the adolescent values and retains their parents’ Hispanic cultural practices (Martinez, 2006).

It may be hypothesized that, for Mexican American adolescents and their families, the effect of parenting practices on substance use would be mediated by levels of acculturation or that the effect of acculturation on substance use may be mediated by certain parenting practices. This would be due to the effects of acculturation in eroding parental monitoring practices and effectiveness. However, a study of Hispanic adolescents by Pokhrel et al. (2008) and a study of Anglo and Hispanic adolescents by Ramirez et al. (2004) found that both parental monitoring and acculturation had significant independent effects in predicting substance use (i.e., that controlling for the effects of acculturation did not attenuate the effects of parental monitoring and vice versa). Such attenuation of effects between these predictors would be indicative of a mediating relationship among them. Moreover, Warner, Fishbein, and Kreb’s (2010) study of Mexican American adolescents found no effects for several indices of acculturation on alcohol use. In addition, they also found that a brief self-report measure of parent involvement/communication did not significantly predict alcohol use (Warner et al., 2010).

However, the effects of acculturation on substance use and the relationship of acculturation to parenting effects may be different from what would be expected from conventional ideas of acculturation, when Mexican American adolescents are drawn from an ethnic enclave of the Southwest United States. The current sample consists of parents and children from such enclaves, as indicated by the almost exclusively Hispanic representation (mean 89% across schools) of students in the sampled schools compared with the 41% representation of Hispanics in Phoenix, Arizona, as a whole (U.S. Census Bureau, 2011). In such enclaves, strong cultural values are often maintained despite linguistic acculturation. Macias (2006) noted the sparsity of research on multigenerational Mexican-heritage families in such enclaves, but his quantitative and qualitative research suggested that ongoing immigration and other factors act to increase the social distance between Anglos and Mexican-heritage individuals from these ethnic enclaves in the Southwest. It may be that acculturation moderates the effects of parental monitoring, such that parental effects are stronger in reducing substance use for low acculturated parents in families where traditional values of familismo are stronger.

In terms of the moderating effects of acculturation on parenting practices, Ramirez et al. (2004) found a significant interaction effect involving familism and parental monitoring on youth inhalant use. Here, parental monitoring effects were stronger in reducing inhalant use for adolescents also exhibiting strong familism, although the interaction of acculturation with parental monitoring was not significant. On the other hand, parental monitoring effects may be stronger in reducing substance use for high acculturated parents who are less embedded in a traditional cultural milieu that regulates social behaviors independently of individual family practices.

Almost all of the studies reviewed above assessed parenting practices based on reports from adolescents, which may be biased to justify problematic behavior. The current study extends these findings by assessing acculturation and parenting practices based on parents’ self-reports of their behaviors and then linking these reports to the adolescents’ reported substance use.

Hypotheses

The following hypotheses guided our study:

Greater parental acculturation would be associated with higher substance use rates in Mexican American adolescents.

Parent reports of greater communication, involvement, and positive parenting would be associated with lower adolescent substance use.

Based on the findings from the Ramirez et al. (2004) study, there would be significant moderating effects of parent acculturation on parental monitoring, thus reducing substance use.

Given the greater importance of familismo for girls than boys in traditional Mexican families, it was expected that the moderating effect of acculturation on parental monitoring in reducing substance use would be more pronounced in girls than boys.

Given the greater effect of acculturation on Mexican American girls than boys (Kulis et al., 2010), it would be expected that the moderating effect of acculturation on parenting effects would be greater for girls than boys.

METHODS

Sample

The data analyzed were drawn from a longitudinal study of the effectiveness of a supplemental Parent Education intervention (Principal Investigators Drs. Felipe González Castro and Flavio Marsiglia at Arizona State University). This intervention was a supplement to the established keepin’ it REAL (Marsiglia & Hecht, 2005) primary prevention intervention to prevent or delay youth adolescent substance use. The development of the curriculum through participatory activities with members of the involved communities and the schools and the implementation of the intervention are discussed in Parsai, Marsiglia, and Kulis (2010). Data for the current analyses were drawn from the preintervention wave 1 assessment of 223 (111 boys, 109 girls, 3 missing gender) youth participants in seventh grade. These analyses included the responses of one of each participating youth’s parents, where the participating parent was almost always the mother. These participating parent-youth dyads were recruited from nine local Phoenix area schools from two school districts that are populated with high percentages of Mexican and Mexican American families. These schools were located in enclaves of predominantly Mexican-heritage families, as indicated by the high proportions of Hispanic (school district classification) children in these 9 schools (range=71% to 99%; mean=89%). The schools, which are located in the heart of the city, are all Title I schools, which means that they provide free or reduced cost lunches to students whose family qualifies based on need criteria. Approximately 75% of the students qualified for this program, an indication that most families are from a low socioeconomic level. The analyses reported here are based on the 189 adolescents (102 boys, 87 girls) who reported their ethnicity as being Mexican or Mexican American. Mean age of the child sample was 12.23 years (SD=.49 years) at the time of initial testing in the Fall semester of their class attendance in the seventh grade. Mean age of the parents was 39.68 (SD=7.14 years) years. One hundred thirty-six of the children reported being born in the United States, whereas 51 reported being born in Mexico and 2 reported being born in an “other country.” Of the parents, 29 reported being born in the United States. Of those not born in the United States, 4 reported being in the United States less than 5 years, 25 for 5 to 10 years, 60 for 10 to 20 years, and the remainder for longer than 20 years.

Measures

The parent questionnaire was administered in either English or Spanish, whereas the child questionnaire was administered in English. The development of the parent curriculum, including issues of cultural sensitivity, are discussed in Bermudez Parsai, Castro, Marsiglia, Harthun, and Valdez (2011). It should be noted that the parenting measures, or similar ones, have been used in previous studies of parenting practices among Mexican-heritage parents (Pantin et al., 2009).

Parent questionnaire

Parental acculturation was measured by the 6-item revised version of the General Acculturation Index (Balcazar, Castro, & Krull, 1995; Castro & Gutierrez, 1997), which included 3 items on language usage that ranged from speaking entirely Spanish to speaking entirely English and items regarding the language used in reading and in mass media usage, television, and radio. Items were responded to on a 5-point scale that ranged from 1 (only Spanish [or another non-English language]) to 5 (only English). Two items assessed interpersonal relations and asked about the ethnic identities of friends and of neighbors, which was assessed on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (almost all Hispanics/Latinos) to 5 (almost all White Americans). One item asked about the respondent’s self-assessed level of ethnic pride, which was assessed on a 5-point dimension ranging from 1 (very proud) to 5 (ashamed). The Cronbach’s α coefficient of internal reliability of this scale for the current sample was .86. The acculturation scale score was calculated as the mean score for these six items, with higher scores indicative of higher levels of acculturation. This acculturation measure takes a unidimensional approach to acculturation in terms of linguistic acculturation and social assimilation.

Parental communications was measured by a 14-item scale (α=0.78 for the current sample) that was developed in a prior study from Barnes and Olson (1985). Example items include the following: “It is easy to express my true feelings to my child” and “My child is always a good listener.” Items were responded to on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), with the calculated scale score being the mean score for these 14 items, such that higher scores represent better parental communication.

Parental involvement was assessed using a 9-item scale (α=.66 for the current sample) drawn from the Pittsburgh Youth Survey (Thornberry, Huizinga, & Loeber, 1995). Example items include the following: “I know what my child is doing when we are both home” and “I talk about how my child is doing in school.” Items were responded to on a 3-point scale ranging from 1 (almost never) to 3 (almost always). Scale scores were the mean for these 14 items, with higher scores indicating greater levels of parental involvement with their child.

Parent positive parenting was assessed with a 4-item scale (α=.64 for the current sample), which was also drawn from the Pittsburgh Youth Survey (Thornberry et al., 1995). Example items include the following: “I give affection (hugs) to my child” and “I give special privileges (such as staying up late) to my child.” Items were responded to on the same 3-point scale used for parental involvement. The scale score was the mean of these four items, with higher scores indicating greater levels of positive parenting.

Child questionnaire

Child control variables included age, school grades (coded from 1 [mostly F’s] to 9 [mostly A’s]), and whether the student was receiving the federal school lunch program (coded 1 [free lunch], 2 [reduced lunch], and 3 [neither]; receiving a free lunch is indicative of low-income status).

Youth substance use was measured by three questions that asked the youth about the number of times the youth had used alcohol, cigarettes, or marijuana. Items were responded to on the following scale: 1 (0 times), 2 (1–2 times), 3 (3–5 times), 4 (6–9 times), 5 (10–19 times), 6 (20–39 times), 7 (40 times or more). Given the low rates of substance use at this age, any early use is a risk factor for later substance use problems.

Data Analyses

Separate hierarchical multiple regression analyses were performed to predict lifetime alcohol, cigarette, or marijuana use. The first block of the model included child gender, the second block added parent acculturation, the third block entered one of the three parent parenting variables (separate regressions were thus conducted for parent communication, involvement, and positive parenting), the fourth block entered the two-way interactions (child gender by parent acculturation, child gender by parent parenting variable, parent acculturation by parent parenting variable), and the final block entered the three-way interaction term. The interaction terms were computed by centering the child gender, parent acculturation, and relevant parenting scores and then multiplying the centered terms. Control variables were considered as covariates for the multiple regression analyses, but none were significantly correlated with the substance use dependent variables (DVs). Means for these control variables are presented in Table 1 to provide additional information on the characteristics of the sample.

TABLE 1.

Means and Standard Deviations of Study Variables by Child Gender

| Scale | Boys

|

Girls

|

t | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Parent variables | |||||

| Acculturation (1–5)a | 2.01 | 0.85 | 1.98 | 0.84 | 0.24 |

| Communication (1–5) | 4.01 | 0.59 | 3.87 | 0.53 | 1.45 |

| Involvement (1–3) | 2.58 | 0.28 | 2.64 | 0.23 | −1.32 |

| Positive parenting (1–3) | 2.53 | 0.38 | 2.50 | 0.36 | 0.60 |

| Child variables | |||||

| Age | 12.27 | 0.51 | 12.21 | 0.46 | 0.85 |

| Grades in school (1–3) | 3.26 | 1.50 | 3.02 | 1.67 | 1.03 |

| School lunch program (1–3) | 1.18 | 0.50 | 1.20 | 0.53 | −0.29 |

| Lifetime alcohol use (1–7) | 1.97 | 1.51 | 1.63 | 1.23 | 1.67 |

| Lifetime cigarette use (1–7) | 1.34 | 1.00 | 1.24 | 0.76 | 0.78 |

| Lifetime marijuana use (1–7) | 1.50 | 1.47 | 1.11 | 0.44 | 2.36* |

Scale endpoints in parentheses.

p < .05.

RESULTS

For the lifetime substance use variables, 39.1% of the sample reported having used alcohol, 15.9% had used cigarettes, and 11.1% had used marijuana at least once.

Table 1 presents the means and standard deviations for the parental acculturation, communication, involvement, positive parenting, and child control variables and lifetime use of alcohol, cigarettes, and marijuana separately by child gender. The only significant gender difference on these variables was greater lifetime marijuana use for boys than girls.

Table 2 presents the correlation matrix of the child lifetime substance use and parental acculturation, communication, involvement, and positive parenting variables separately by child gender. The parenting variables were not significantly correlated with parental acculturation. For both boys and girls, parental involvement was significantly correlated with parent positive reinforcement, but parent communication was correlated with parental involvement and positive parenting only for boys. Higher parental acculturation was associated with a higher lifetime use of alcohol and cigarettes just for girls. The parenting variables were not significantly correlated with lifetime substance use for boys, but higher levels of parental communication were associated with lower lifetime cigarette and marijuana use among girls.

TABLE 2.

Correlation Matrix of Study Variables by Child Gendera

| Variables | Alcohol use | Cigarette use | Marijuana use | Acculturation | Communication | Involvement | Positive parenting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child alcohol use | – | .63*** | .44*** | .23* | −.17 | −.14 | −.05 |

| Child cigarette use | .26** | – | .61*** | .32** | −.35** | −.06 | −.05 |

| Child marijuana use | .40*** | .48*** | – | .21 | −.31** | .07 | −.09 |

| Parent acculturation | −.19 | .02 | .19 | – | −.02 | −.06 | .04 |

| Parent communication | −.19 | −.14 | −.17 | .15 | – | .09 | .05 |

| Parent involvement | −.07 | .08 | .03 | .11 | .46*** | – | .32** |

| Parent positive parenting | −.09 | −.02 | −.02 | .14 | .22* | .36*** | – |

Boys are below the diagonal. Girls are above the diagonal.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

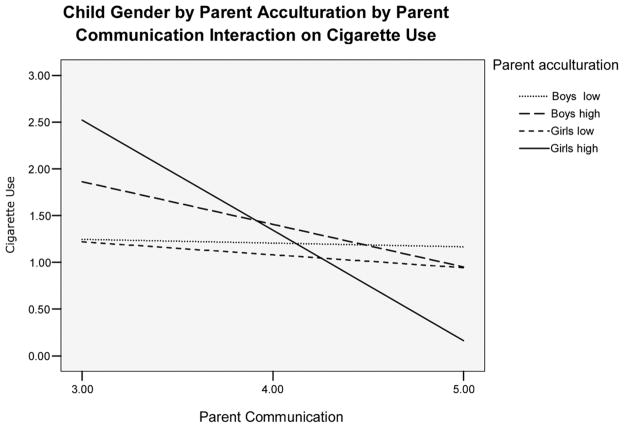

Table 3 presents the hierarchical multiple regression results for child life-time use of alcohol, cigarettes, and marijuana for the five-block model including the following: (a) child gender (b) parent acculturation; (c) parent communication; (d) the interactions of child gender by parent acculturation, child gender by parent communication, and parent acculturation by parent communication; and (e) the three-way interaction of child gender by parent acculturation by parent communication. Over and above the effects of child gender, greater parent acculturation predicted greater marijuana use. Over and above the effects of parent acculturation, parent communication was significantly negatively associated with all three lifetime substance use variables. There was a significant parent acculturation by parent communication interaction for lifetime cigarette use, but this was subsumed by a near-significant three-way interaction (Figure 1). Parent communication was strongly negatively associated with cigarette use for boys and girls with high acculturated parents, whereas parent communication effects were essentially zero for boys and girls with low acculturated parents. The near-significant three-way interaction results from the above effect were stronger for girls. Separate multiple regression analyses indicated that the parent acculturation by parent communication interaction on cigarette use was nonsignificant for boys but highly significant for girls (F change [1, 65]=12.51, p<0.001). The near-significant three-way interaction for lifetime alcohol use was similar to the one for cigarette use.

TABLE 3.

Hierarchical Multiple Regressions of Child Alcohol, Cigarette, and Marijuana Use on Child Gender by Parent Acculturation and Communication

| Alcohol

|

Cigarettes

|

Marijuana

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| βa | ΔR2 | β | ΔR2 | β | ΔR2 | |

| Child gender | −.14+ | .02 | −.04 | .00 | −.21* | .03* |

| Parental acculturation | −.04 | .00 | .09 | .02+ | .17* | .03* |

| Parental communication | −.21* | .04* | −.34*** | .07*** | −.23** | .04* |

| Child gender by parental communication | .12 | .07 | −.14 | |||

| Child gender by parental communication | −.02 | −.19* | .05 | |||

| Parental acculturation by parental communication | −.11 | .04 | −.26** | .10*** | −.09 | .02 |

| Gender by acculturation by communication | −.16+ | .02+ | −.15+ | .02+ | −.03 | .00 |

β for full model.

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

FIGURE 1.

Interaction of child gender by parental acculturation by parental communication on cigarette use.

Table 4 presents the hierarchical multiple regression analyses with parent involvement as the parenting variable. There were no significant main effects or interactions of parent involvement in predicting child lifetime substance use.

TABLE 4.

Hierarchical Multiple Regressions of Child Alcohol, Cigarette, and Marijuana Use on Child Gender and Parent Acculturation and Involvement

| Alcohol

|

Cigarettes

|

Marijuana

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| βa | ΔR2 | β | ΔR2 | β | ΔR2 | |

| Child gender | −.08 | .01 | .01 | .00 | −.17* | .03* |

| Parental acculturation | .00 | .00 | .19* | .03* | .19* | .04* |

| Parental involvement | −.12 | .02 | .02 | .00 | .03 | .00 |

| Child gender by parental acculturation | .19* | .11 | −.11 | |||

| Child gender by parental involvement | −.04 | −.06 | .01 | |||

| Parental acculturation by parental involvement | .02 | .04 | .04 | .02 | .04 | .01 |

| Gender by acculturation by involvement | −.06 | .00 | −.02 | .00 | −.04 | .00 |

β for full model.

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

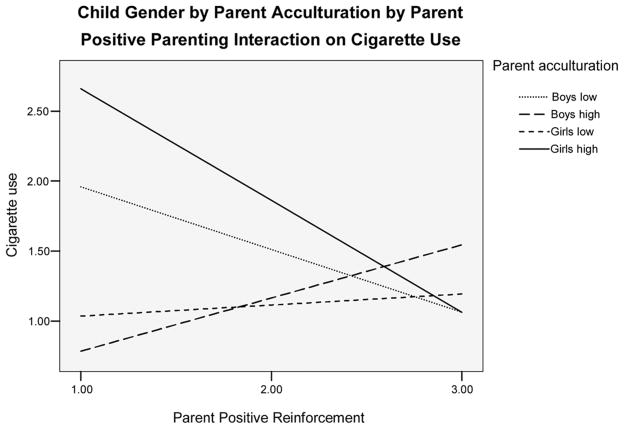

Table 5 presents the hierarchical multiple regression analyses with parent positive parenting as the parenting variable. Although there were no significant main effects of parent positive parenting in predicting child lifetime substance use, there was a significant child gender by parent acculturation by parent positive parenting interaction for lifetime cigarette use. As can be seen in Figure 2, for girls the pattern of the interaction was similar to the parent communication effect shown in Figure 1. Parent positive parenting was associated with lower cigarette use for girls with high acculturated parents, but such parenting was associated with somewhat higher cigarette use for girls with low acculturated parents. However, for boys the pattern was reversed, with parent positive parenting associated with lower cigarette use for boys with low acculturated parents and higher cigarette use for boys with high acculturated parents. Separate multiple regression analyses indicated that the interactions of parent acculturation by parent positive parenting were near-significant for both girls (F change [1, 71]=3.24, p<.09) and boys (F change [1, 85]=3.43, p<.07).

TABLE 5.

Hierarchical Multiple Regressions of Child Alcohol, Cigarette, and Marijuana Use on Child Gender and Parent Acculturation and Positive Parenting

| Alcohol

|

Cigarettes

|

Marijuana

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| βa | ΔR2 | β | ΔR2 | β | ΔR2 | |

| Child gender | −.10 | .01 | −.01 | .00 | −.19* | .03* |

| Parental acculturation | −.03 | .00 | .10 | .02+ | .15+ | .03* |

| Parental positive parenting | −.10 | .01 | −.07 | .00 | −.09 | .01 |

| Child gender by parental acculturation | .18* | .11 | −.10 | |||

| Child gender by parental positive | −.03 | −.08 | .01 | |||

| Parental acculturation by parental positive parenting | .06 | .04+ | .03 | .02 | −.02 | .01 |

| Gender by acculturation by positive parenting | −.09 | .01 | −.21* | .04* | −.08 | .01 |

β for full model.

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

FIGURE 2.

Interaction of child gender by parental acculturation by parental positive parenting on cigarette use.

DISCUSSION

The current findings offer an important extension to prior research that has examined the effects of acculturation and parenting practices on the substance use of Mexican heritage adolescents. Whereas previous studies have had to rely on the possibly biased self-reports of the adolescent to measure the behaviors of parents (Pokhrel et al., 2008; Ramirez et al., 2004; Warner et al., 2009), the current study assessed parents’ own perceptions of their level of acculturation and parenting practices. Consistent with previous research (Epstein et al., 2003; Gil et al., 2000; Myers et al., 2009; Unger et al., 2006) and the current study’s hypotheses, higher levels of parental acculturation were found in the current study to be associated with higher rates of marijuana use among these Mexican heritage adolescents.

The current findings confirm the importance of parenting practices in reducing the likelihood of substance use in Mexican American, but also highlight how cultural factors, including those related to gender, can strengthen or attenuate these parenting effects. Rodriguez and Zayas (1990) noted how Mexican culture instills less freedom, more deference, and more structure in social interactions, sheltering women from situations involving antisocial behavior. For example, alcohol use in Latino families may be normative at family gatherings or as a rite of passage into adulthood (Perea & Slater, 1999). These differences for boys and girls across different substances suggest that there may be cultural aspects associated with their link to acculturation and the parenting variables. This effect may be particularly salient for girls as they become more acculturated and move away from the traditional family values associated with certain environments in Mexico, such as rural and more traditional communities (Castro et al., 2009). These traditional values, or familismo, focus on family as a collective unit. As girls become more acculturated to the norms of mainstream U.S. society, they may shift to more individualistic attitudes toward family, where these girls may push away from the expected strong family ties.

In terms of specific parenting practices, the current findings are consistent with previous findings (reviewed by Ryan et al., 2010) that, although greater parent communication and positive parenting are predictive of reduced adolescent problem behaviors, parent involvement by itself is not predictive. However, in terms of gender differences, the current findings are not consistent with those from the study by Cota-Robles and Gamble (2006), which found that parental, particularly mothers’ monitoring and parent- adolescent attachment, reduced the risk for delinquency among Mexican American boys, with lesser effects among girls. Besides the use of child reports of parenting behaviors in the Cota-Robles and Gamble (2006) study, another explanation for the seemingly attenuated effects of parenting practices in the current study is the need to consider neighborhood contextual factors on parenting strategies, particularly in the case of Mexican American families drawn from ethnically homogeneous enclaves (Macias, 2006). Meanwhile, the finding that parent positive parenting is associated with greater cigarette use for boys with high acculturated parents echoes the findings of Fagan, Van Horn, Antaramian, and Hawkins (2011), where in some cases greater parent attachment was associated with greater substance use, as well as previous studies finding inconsistent relationships of positive parenting with offspring problem behaviors (Tildesley & Andrews, 2008).

A study by Ceballo and Hurd (2008) may explain why parent communication and positive parenting effects were stronger for high acculturated parents in reducing cigarette use in Mexican American adolescent girls. For their subsample of Latina mothers, Ceballo and Hurd (2008) found that the level of acculturation was positively related to parental sense of self-efficacy and efficacy in psychological control strategies. An alternative explanation is that the low acculturated parents may have children who are considerably more acculturated than the parents, thus creating an acculturation gap that disrupts parent-child communications and parental monitoring, which would be expected to increase the risks of child problem behaviors. A study of Mexican American adolescents by Marsiglia, Kulis, FitzHarris, and Becerra (2009) found that the relationship between the extent of the parent-child acculturation gap and externalizing behaviors was mediated by family conflict. However, previous research on the effects of the parent-offspring acculturation gap on Mexican American adolescent functioning has yielded mixed findings (Lau et al., 2005; Schofield, Kim, Parke, & Coltrane, 2008; Smokowski, Rose, & Bacallao, 2008).

Limitations and Future Research

It should be noted that this randomized intervention study sample was drawn only from predominantly Mexican neighborhoods in the central and southern areas of a large Southwestern city. The participants may not be representative of all Mexican Americans in the city, the Southwest, or the nation. This sample was also self-selected to participate in a preventive intervention, which may also limit the generalizability of the findings. Due to the crosssectional design of this study, causal pathways and directionality of effects cannot be established. Future research should include a larger sample size and a longitudinal design that allows for the analysis of temporal relationships and the ability to detect whether the moderating effects of acculturation on parenting practices change over time and the extent to which parent acculturation and previous substance use explain current parenting behavior. Because the parent questionnaire was completed by mostly mothers, future studies should include both mothers and fathers to examine parent-child effects that may differ by the gender of the parent. In addition, for immigrant families, future research might also assess the effects of years of residency within the United States, which has been shown generally to decrease amounts of parental monitoring as the adolescent adopts more mainstream American values and norms. Future research should also consider studying the acculturation gap between parents and youths, given its relevance in acculturation and substance use. Additional measures that are related to acculturation, such as generation status, ethnic identification, bidimensional acculturation strategies, and acculturation stress, should also be considered. It would also be useful to directly measure the extent to which parents and youths adhere to traditional Mexican values of familismo and respeto, as was done in the studies by Ramirez et al. (2004) and Smokowski et al. (2008). It is clear that interventions targeting parental practices to decrease substance use in Mexican American adolescents need to consider the cultural context within which these families operate.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) of the National Institutes of Health (P20MD002316-07; PI: Flavio F. Marsiglia), funding the Southwest Interdisciplinary Research Center. This study was also funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (F31 DA005629; PI: Julie Nagoshi).

Footnotes

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views the NIMHD, NIDA, or the NIH.

Contributor Information

FLAVIO F. MARSIGLIA, Southwest Interdisciplinary Research Center, School of Social Work, Arizona State University, Phoenix, Arizona

JULIE L. NAGOSHI, Southwest Interdisciplinary Research Center, Arizona State University, Phoenix, Arizona, and School of Social Work, University of Texas at Arlington, Arlington, Texas

MONICA PARSAI, Southwest Interdisciplinary Research Center, Arizona State University, Phoenix, Arizona.

FELIPE GONZÁLEZ CASTRO, Southwest Interdisciplinary Research Center, Arizona State University, Phoenix, Arizona, and Department of Psychology, University of Texas at El Paso, El Paso, Texas.

References

- Alvarez JLM, Martin AF, Vergeles MR, Martin AH. Substance use in adolescence: Importance of parental warmth and supervision. Psicothema. 2003;15:161–166. [Google Scholar]

- Archer J, Lloyd B. Sex and gender. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Balcazar H, Castro FG, Krull JL. Cancer risk reduction in Mexican American women: The role of acculturation, education, and health risk factors. Health Education Quarterly. 1995;22:61–84. doi: 10.1177/109019819502200107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK, Stolz HE, Olsen JA. Parental support, psychological control, and behavioral control: Assessing relevance across time, culture, and method. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2005;70(4):1–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2005.00365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes HL, Olson DH. Parent-adolescent communication and the Circumplex Model. Child Development. 1985;56:438–447. [Google Scholar]

- Bermudez Parsai M, Castro FG, Marsiglia FF, Harthun ML, Valdez H. Using community based participatory research to create a culturally grounded intervention for parents and youth to prevent risky behaviors. Prevention Science. 2011;12:34–47. doi: 10.1007/s11121-010-0188-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW. In: Immigrant youth in cultural transition: Acculturation, identity, and adaptation across national contexts. Berry JW, Phinney JS, Sam DL, Vedder P, editors. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Castro FG, Coe K. Traditions and alcohol use: A mixed-methods analysis. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2007;13:269–284. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.4.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro FG, Gutierres S. Drug and alcohol use among rural Mexican Americans. In: Robertson EB, Sloboda Z, Boyd GM, Beatty L, Kozel NJ, editors. Rural substance abuse: State of knowledge and issues. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 1997. pp. 498–533. NIDA Research Monograph No. 168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro FG, Stein JA, Bentler PM. Ethnic pride, traditional family values, and acculturation in early cigarette and alcohol use among Latino adolescents. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2009;30:265–292. doi: 10.1007/s10935-009-0174-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceballo R, Hurd N. Neighborhood context, SES, and parenting: Including a focus on acculturation among Latina mothers. Applied Developmental Science. 2008;12:176–180. [Google Scholar]

- Cernkovich SA, Giordano PC. Family relationships and delinquency. Criminology. 1987;25:295–319. [Google Scholar]

- Chun KM, Akutsu PD. Acculturation among ethnic minority families. In: Chun KM, Balls Organista P, Marin G, editors. Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement, and applied research. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2003. pp. 95–119. [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland MJ, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Pomery EA, Brody GH. The impact of parenting on risk cognitions and risk behavior: A study of mediation and moderation in a panel of African American adolescents. Child Development. 2005;76:900–916. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coatsworth JD, Pantin H, McBride C, Briones E, Kurtines W, Szapocznik J. Ecodevelopmental correlates of behavior problems in young Hispanic females. Applied Developmental Science. 2002;6:126–143. [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA, Laursen B. Parent-adolescent relationships and influences. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of adolescent psychology. 2. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons; 2004. pp. 331–362. [Google Scholar]

- Coombs RH, Landsverk JL. Parenting styles and substance use during childhood and adolescence. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1988;50:473–482. [Google Scholar]

- Cota-Robles S, Gamble W. Parent-adolescent processes and reduced risk for delinquency: The effect of gender for Mexican American adolescents. Youth Society. 2006;37:375–392. [Google Scholar]

- Dakof GA. Understanding gender differences in adolescent drug abuse: Issues of comorbidity and family functioning. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2000;32:25–32. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2000.10400209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling N, Steinberg L. Parenting style as context: An integrative model. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;113:487–496. [Google Scholar]

- Denner J, Kirby D, Coyle K, Brindis C. The protective role of social capital and cultural norms in Latino communities: A study of adolescent births. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2001;23:3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis RA, O’Hara M, Sowers KM. Profile-based intervention: Developing gender-sensitive treatment for adolescent substance abusers. Research on Social Work Practice. 2000;10:327–347. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein JA, Botvin GJ, Diaz T. Linguistic acculturation associated with higher marijuana and polydrug use among Hispanic adolescents. Substance Use and Misuse. 2001;36:477–499. doi: 10.1081/ja-100102638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein JA, Doyle M, Botvin GJ. A mediational model of the relationship between linguistic acculturation and polydrug use among Hispanic adolescents. Psychological Reports. 2003;93:859–866. doi: 10.2466/pr0.2003.93.3.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan AA, Van Horn ML, Antaramian S, Hawkins JD. How do families matter? Age and gender differences in family influences on delinquency and drug use. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice. 2011;9:150–170. doi: 10.1177/1541204010377748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang L, Schinke SP, Cole KC. Underage drinking among young adolescent girls: The role of family processes. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23:708–714. doi: 10.1037/a0016681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fosados R, McClain A, Ritt-Olson A, Sussman S, Soto D, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Unger JB. The influence of acculturation on drug and alcohol use in a sample of adolescents. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2990–3004. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freshman A, Leinwand C. The implications of female risk factors for substance abuse prevention in adolescent girls. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community. 2000;21:29–51. doi: 10.1300/J005v21n01_03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gil AG, Wagner EF, Vega WA. Acculturation, familism, and alcohol use among Latino adolescent males: Longitudinal relations. Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28:443–458. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert MJ, Cervantes RC. Patterns and practices of alcohol use among Mexican Americans: A comprehensive review. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1986;8:1–60. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, Dumka LE, Millsap RE, Gottschall A, McClain DB, Wong JJ, Kim SY. Randomized trial of a broad preventive intervention for Mexican American adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80:1–16. doi: 10.1037/a0026063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman-Smith D, Tolan PH, Henry DBB. A developmentalecological model of the relation of family functioning to patterns of delinquency. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 2000;16:169–198. [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie BJ, Low LK. A substance use prevention framework: Considering the social context for African American girls. Public Health Nursing. 2000;17:363–373. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1446.2000.00363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussey JM, Hallfors DD, Waller MW, Iritani BJ, Halpern CT, Bauer DJ. Sexual behavior and drug use among Asian and Latino adolescents: Association with immigrant status. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2007;9:85–94. doi: 10.1007/s10903-006-9020-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings, 2007. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2008. NIH Publication No. 08–6418. [Google Scholar]

- Kauffman SE, Silver P, Poulin J. Gender differences in attitudes toward alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs. Social Work. 1997;42:231–241. doi: 10.1093/sw/42.3.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulis S, Marsiglia FF, Nagoshi JL. Gender roles, externalizing behaviors, and substance use among Mexican-American adolescents. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions. 2010;10:283–307. doi: 10.1080/1533256X.2010.497033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulis S, Marsiglia FF, Nieri T. Perceived ethnic discrimination versus acculturation stress: Influences on substance use among Latino youth in the southwest. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2009;50:443–459. doi: 10.1177/002214650905000405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulis S, Yabiku S, Marsiglia FF, Nieri T, Crossman A. Differences by gender, ethnicity, and acculturation in the efficacy of the keepin’ it REAL model prevention program. Journal Drug Education. 2007;37:123–144. doi: 10.2190/C467-16T1-HV11-3V80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau AS, McCabe KM, Yeh M, Garland AF, Wood PA, Hough RL. The acculturation gap-distress hypothesis among high risk Mexican American families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19:367–375. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.3.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macias T. Mestizo in America: Generations of Mexican ethnicity in the suburban southwest. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Marin G, Gamba RJ. A new measurement of acculturation for Latinos: The Bidimensional Acculturation Scale for Latinos (BAS) Latino Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1996;18:297–316. [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Hecht ML. Keepin’ it REAL: An evidence-based program. Santa Cruz, CA: ETR Associates; 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Kulis S, FitzHarris B, Becerra D. Acculturation gaps and problem behaviors among U.S. southwestern Mexican youth. Social Work Forum 42. 2009;43:6–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Kulis S, Hussaini SK, Nieri TA, Becerra D. Gender differences in the effect of linguistic acculturation on substance use among Mexican-origin youth in the southwest United States. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2010;9:40–63. doi: 10.1080/15332640903539252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Kulis S, Wagstaff DA, Elek E, Dran D. Acculturation status and substance use prevention with Mexican and Mexican-American youth. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions. 2005;5:85–111. doi: 10.1300/J160v5n01_05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Parsai MB, Kulis S. Effects of familism & family cohesion on problem behaviors among adolescents in Mexican immigrant families in the southwest U.S. Journal of Ethnicity & Cultural Diversity in Social Work. 2009;18:203–220. doi: 10.1080/15313200903070965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez CR., Jr Evidence of differential family acculturation on Latino adolescent substance use. Family Relations. 2006;55:306–317. [Google Scholar]

- Martyn KK, Loveland-Cherry CJ, Villarruel AM, Gallegos Cabriales E, Zhou Y, Ronis DL, Eakin B. Mexican adolescents’ alcohol use, family intimacy, and parent-adolescent communication. Journal of Family Nursing. 2009;15:152–170. doi: 10.1177/1074840709332865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon DG, Hecht ML, Jackson KM, Speller RE. Ethnic and gender differences and similarities in adolescent drug use and refusals of drug offers. Substance Use & Misuse. 1999;34:1059–1083. doi: 10.3109/10826089909039397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers R, Chou CP, Sussman S, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Pachon H, Valente TW. Acculturation and substance use: Social influence as a mediator among Hispanic alternative high school youth. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2009;50:164–179. doi: 10.1177/002214650905000204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse. The formative years: Pathways to substance abuse among girls and young women ages 8–22. New York, NY: National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Newman K, Harrison L, Dashiff C, Davies S. Relationships between parenting styles and risk behaviors in adolescent health: An integrative literature review. Review of Latin American Enfermagem. 2008;16:142–150. doi: 10.1590/s0104-11692008000100022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantin H, Prado G, Lopez B, Huang S, Tapia MI, Schwartz SJ, Branchini J. A randomized controlled trial of Familias Unidas for Hispanic adolescents with behavior problems. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2009;71:987–995. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181bb2913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsai M, Marsiglia FF, Kulis S. Parental monitoring, religious involvement and drug use among Latino and Non-Latino youth in the southwestern United States. British Journal of Social Work. 2010;40:100–114. doi: 10.1093/bjsw/bcn100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perea A, Slater MD. Power distance and collectivist/individualist strategies in alcohol warnings: Effects of gender and ethnicity. Journal of Health Communication. 1999;4:295–310. doi: 10.1080/108107399126832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokhrel P, Unger JB, Wagner KD, Ritt-Olson A, Sussman S. Effects of parental monitoring, parent-child communication and parent’s expectation of the child’s acculturation on the substance use behaviors of urban Hispanic adolescents. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2008;7:200–213. doi: 10.1080/15332640802055665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez JR, Crano WD, Quist R, Burgoon M, Alvaro EM, Granpre J. Acculturation, familism, parental monitoring, and knowledge as predictors of marijuana and inhalant use in adolescents. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18:3–11. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redfield R, Linton R, Herskovits MJ. Memorandum for the study of acculturation. American Anthropologist. 1936;38:149–152. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez O, Zayas LH. Hispanic adolescents and antisocial behavior: Sociocultural factors and treatment implications. In: Stiffmann AR, Davis LE, editors. Ethnic issues in adolescent mental health. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1990. pp. 147–171. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan SM, Jorm AF, Lubman DI. Parenting factors associated with reduced adolescent alcohol use: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;44:774–783. doi: 10.1080/00048674.2010.501759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schinke SP, Fang L, Cole KCA. Substance use among early adolescent girls: Risk and protective factors. The Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;43:191–194. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield TJ, Parke RD, Kim Y, Coltrane S. Bridging the acculturation gap: Parent-child relationship quality as a moderator in Mexican American families. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:1–5. doi: 10.1037/a0012529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Montgomery MJ, Briones E. The role of identity in acculturation among immigrant people: Theoretical propositions, empirical questions, and applied recommendations. Human Development. 2006;49:1190–1194. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Pantin H, Sullivan S, Prado G, Szapocznik J. Nativity and years in the receiving culture as markers of acculturation in ethnic enclaves. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2006;37:345–353. doi: 10.1177/0022022106286928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C, Krohn MD. Delinquency and family life among male adolescents: The role of ethnicity. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1995;24:69–93. [Google Scholar]

- Smokowski PR, Rose R, Bacallao ML. Acculturation and Latino family processes: How cultural involvement, biculturalism, and acculturation gaps influence family dynamics. Family Relations. 2008;57:295–308. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. We know some things: Parent-adolescent relationships in retrospect and prospect. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2001;11:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan S, Schwartz SJ, Prado G, Huang S, Pantin H, Szapocznik J. A bidimensional model of acculturation for examining differences in family functioning and behavior problems in Hispanic immigrant adolescents. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2007;27:405–430. [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry TP, Huizinga D, Loeber R. The prevention of serious delinquency and violence: Implications from the program of research on the causes and correlates of delinquency. In: Howell JC, Krisberg B, Hawkins JD, Wilson JJ, editors. Sourcebook on serious, violent, and chronic juvenile offenders. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1995. pp. 213–237. [Google Scholar]

- Tildesley EA, Andrews JA. The development of children’s intentions to use alcohol: Direct and indirect effects of parent alcohol use and parenting behaviors. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:326–339. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.3.326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobler AL, Komro KA. Trajectories of parental monitoring and communication and effects on drug use among urban young adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;46:560–568. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger JB, Cruz TB, Rohrbach LA, Ribisl KM, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Chen X, Johnson CA. English language use as a risk factor for smoking initiation among Hispanic and Asian American adolescents: Evidence for mediation by tobacco-related beliefs and social norms. Health Psychology. 2000;19:403–410. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.19.5.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger JB, Shakib S, Gallaher P, Ritt-Olson A, Mouttapa M, Palmer PH, Johnson CA. Cultural/interpersonal values and smoking in an ethnically diverse sample of southern California adolescents. Journal of Cultural Diversity. 2006;13:55–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. The Hispanic population: 2010 census brief. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-04.pdf.

- Vega WA, Zimmerman RS, Warheit GJ, Apospori E, Gil AG. Acculturation strain theory: Its application in explaining drug use behavior among Cuban and other Hispanic youth. Substance Use & Misuse. 1997;32:1943–1948. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voisine S, Parsai M, Marsiglia FF, Kulis S, Nieri T. Effects of parental monitoring, permissiveness, and injunctive norms on substance use among Mexican and Mexican American adolescents. Families in Society. 2008;89:264–273. doi: 10.1606/1044-3894.3742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner TD, Fishbein DH, Krebs CP. The risk of assimilating? Alcohol use among immigrant and U.S.-born Mexican youth. Social Science Research. 2010;39:176–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]