Abstract

Contemporary influenza B viruses are classified into two groups known as Yamagata and Victoria lineages. The co-circulation of two viral lineages in recent years urges for a robust and simple diagnostic test for detecting influenza B viruses and for lineage differentiation. In this study, a SYBR green-based asymmetric PCR assay has been developed for influenza B virus detection. Apart from identifying influenza B virus, the assay contains sequence-specific probes for lineage differentiation. This allows identifying influenza B virus and detecting influenza B viral lineage in a single reaction. The test has been evaluated by a panel of respiratory specimens. Of 108 Influenza B virus-positive specimens, 105 (97%) were positive in this assay. None of the negative control respiratory specimens were positive in the test (N=60). Viral lineages of all samples that are positive in the assay (N=105) can also be classified correctly. These results suggest that this assay has a potential for routine influenza B virus surveillance.

Keywords: Influenza B virus, RT-PCR, Yamagata, Victoria, Lineage differentiation

Introduction

Influenza viruses belong to the family Orthomyxoviridae and are divided into three genera A, B, and C (Wright et al., 2007). Influenza A and B viruses are responsible for the annual epidemics in humans (Hampson and Mackenzie, 2006). While the prevalence of Influenza B infection is generally lower than those caused influenza A viruses in most of the seasons, Influenza B virus also can cause significant morbidity and mortality to infants and children.

Contemporary influenza B viruses can be divided into two genetically and antigenically distinct lineages known as Victoria and Yamagata lineages (Kanegae et al., 1990; Rota et al., 1990; Hay et al., 2001). They were named after their first representatives, B/Victoria/2/87 and B/Yamagata/16/88, respectively. The divergence of HA1 domain of the viral HA gene is used to classify Influenza B strains into one of the two lineages (Wright, et al., 2007; Ambrose and Levin, 2012). In recent Influenza seasons, variants from these two lineages have circulated concurrently at varying levels. As trivalent vaccines for influenza only contain a single component for influenza B virus, an accurate and timely epidemiological data about the prevalence of these lineages would be important for determining vaccine composition.

Viral isolation followed by hemagglutination inhibition (HI) test is one of the traditional methods for detecting influenza B viruses and differentiating their lineages. This approach can isolate viruses for further characterization, but it is time consuming and labor intensive. In addition, virus isolation often requires fresh or properly stored specimens. RT-PCR followed by DNA sequencing is an alternative approach for influenza B virus detection and lineage differentiation, but additional post-PCR steps are required. Of these reasons, highly sensitive, specific and rapid real-time RT-PCR approach is considered to be another option for influenza B virus detection and lineage differentiation. Using lineage-specific hydrolysis probes specific for Victoria and Yamagata lineages, a number of real-time RT-PCR based assays were developed for the lineage differentiation (Biere et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2012). As the readouts of this approach depend entirely on the hydrolysis probes, some influenza B viruses that have major mismatches to these two probes might become negative in the assays. Thus, even the primer sets of these previous assays can react with these influenza B viruses, these influenza B positive specimens might be misdiagnosed as influenza B negative. In the current study, a novel Linear-after-the-exponential (LATE)-PCR based assay for simultaneous detection of influenza B virus and for lineage differentiation is developed to bridge this diagnostic gap.

Materials and methods

Clinical samples

A total of 168 retrospective clinical samples tested previously by direct immunofluorescent antibody staining were used for the evaluation, with 108 were Influenza B virus-positive and 60 were Influenza B virus-negative. The Influenza B virus-positive samples were mostly nasopharyngeal aspirate specimens and a few of these were throat swabs. The nasopharyngeal aspirate specimens were collected throughout 2006–2013 (2006–2010, N=40; 2011, N=57; 2012, N=2 and 2013, N=4) and the throat swab samples were collected from year 2009 (N=5). The Influenza B virus-negative samples were nasopharyngeal aspirate specimens collected throughout 2006–2011, in which 45 specimens were viral culture positive for non-Influenza B respiratory viruses such as Influenza A virus and respiratory syncytial virus, and 15 specimens were negative in virus isolation.

Nucleic acid extraction and reverse transcription

Total nucleic acid from clinical samples was extracted by the NucliSENS easyMAG platform (bioMérieux) using the off-board protocol according to manufacturer’s instructions. One hundred fifty microliters of clinical sample was added to 2 ml NucliSENS easyMAG lysis buffer (bioMérieux) and the mixture was incubated at room temperature for 10 minutes. The lysed sample was then transferred to a sample strip with 100 μl NucliSENS easyMAG magnetic silica solution (bioMérieux), followed by automatic magnetic separation. The extracted nucleic acid of each sample was eluted in 25 μl elution buffer.

A two-step RT-PCR approach was adapted in this study. For a typical reverse transcription reaction, 10 μl reaction containing 5.5 μl of purified RNA, 100 U of Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies), 2 μl of 5x FS (first-strand) buffer (Life Technologies), 0.1 μg of Uni12 (5′-AGCAAAAGCAGG-3′), 10 mmol/L of dithiothreitol, and 0.5 mmol/L of deoxynucleoside triphosphates was incubated at 42°C for 50 minutes, followed by a heat inactivation step (72°C for 15 minutes).

Preparation of Influenza B hemagglutinin plasmids as quantification standards

Plasmids containing the Influenza B Victoria or Yamagata lineage-specific sequences targeted by the genotypic assay were prepared for the quantification of gene copy number. In brief, cDNAs of one Victoria lineage sample and one Yamagata lineage sample were generated from viral RNA from the corresponding lineages. The two viral hemagglutinin (HA) genes were amplified by PCR using HA primers MDV-B5′ BsmBI-HA (5-TATTCGTCTCAGGGAGCAGAAGCAGAGCATTTTCTAATATC-3′) and MDV-B3′ BsmBI-HA (5′-ATATCGTCTCGTATTAGTAGTAACAAGAGCATTTTTC-3′) (Hoffmann et al., 2002). The amplicons were purified using a QIAquick gel purification kit followed by cloning into pCR2.1-TOPO Vector using the TOPO TA Cloning Kit (Life Technologies) according to manufacturer instructions. The plasmids were transformed into chemically competent E. coli DH5α cells and the sequence identities were confirmed by standard Sanger sequencing. The plasmids were quantified by NanoDrop fluorospectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Quantitative real-time PCR with LATE PCR-based genotypic assay

One microliter of undiluted cDNA sample was amplified in a 20-μl reaction containing 10 μl of Fast SYBR Green Master Mix (Life Technologies), 500 nM of forward primer FluB-326-F1, 50 nM of reverse primer FluB-495-R1, 500 nM of Victoria-LNA probe, and 500 nM of Yamagata-C3 probe. The reaction was performed in a 7500 Sequence Detection System (Life Technologies) with the following conditions: 20 sec at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 3 sec and 60°C for 30 sec. To determine the specificity of the assay, PCR products were subjected to a melting-curve analysis at the end of the amplification step (95°C for 15 sec, 55°C for 1 minute, and 95°C for 15 sec; Temperature increment: 1.5°C per minute). Diluted plasmids containing the full-length HA genes of Victoria lineage and Yamagata lineage were included in each run as standards to generate standard curves over a range of 101 to 108 copies per reaction. The use of asymmetric PCR approach is known to increase the amount of single stranded PCR templates available for the binding of hybridization probe in the melting curve analysis (Poulson and Wittwer, 2007)

Sequence analysis and primer design

Full-length HA sequences of human influenza B viruses uploaded in or before November 2013 were obtained from GeneBank. The downloaded 2201 full-length sequences were edited and aligned by BioEdit (http://www.mbio.ncsu.edu/BioEdit/bioedit.html). The primers target a conserved region of the Influenza B HA gene and are able to detect both the Victoria and Yamagata lineages. Primer and probe sequences specific for these two lineages are: forward primer HA-326-F (5′-GCTTTCCTATAATGCACGACAGAAC-3′), reverse primer HA-495-R (5′-CCAAGCCATTGTTGCRAARAATCCG-3), Victoria-LNA probe (5′-Cy5-GAGGATACGAACATATCAGG-BHQ2-3′, Cy5: cyanine 5; BHQ2: Black Hole Quencher 2; Underlined nucleotides: Locked nucleic acid-modified bases) and Yamagata-C3 probe (5′-GATCCTGAGGTTCCAAGTCTGTAGG-C3-3, C3: C3 spacer).

Results

Assay design

In this study, a SYBR green-based assay was developed for influenza B virus detection and lineage differentiation. The primer set was designed to cross react with both Victoria and Yamagata lineages and the desired PCR products could yield a major peak at about 76°C in the post-PCR melting analysis (see below). A locked nucleic acid (LNA) probe labeled with a Cy5 reporter at the 5′ end was used as a hydrolysis probe to detect viruses from the Victoria lineage during the amplification step (Johnson et al., 2004). A short oligo labeled with a C3 spacer at the 3′ end was used as a hybridization probe for detecting viruses of Yamagata lineage. The addition of C3 spacer in this probe can prevent the elongation of this oligo during the PCR amplification step (Dames et al., 2007). This probe could bind to Yamagata-specific PCR products and yielded a minor peak in the melting curve analysis (Tm≈64 °C, see below). In order to enhance the Yamagata-specific signal in the melting curve analysis, asymmetric PCR reactions with the reverse primer being 10-fold less than the forward primer were used in this study.

A total of 2201 full-length influenza B viral HA gene sequences consisting of 1226 Victoria and 975 Yamagata sequences were used in the primers and probes design. The primer set was designed to cross react with both viral lineages. Of the 2201 analysed HA sequences, 99.6% have ≤1 nucleotide mismatch with the forward primer (HA-326-F) and 99.9% have ≤1 nucleotide mismatch with the reverse primer (HA-495-R). As for the Victoria lineage-specific LNA probe, 99.3% of the 1226 Victoria HA sequences have ≤1 nucleotide mismatch with this probe, with 79.% of these sequences have a perfect match with the probe. Similarly, 99.1% of viral sequences from the Yamagata lineage have ≤1 nucleotide mismatch to the Yamagata-specific probe, with 89.7% of these sequences have a perfect match to the probe. Using the sequence dataset of our current study (n=2201), the specificity of primer and probe set developed in this study was compared to those reported by other previous studies (Biere, et al., 2010; Zhang, et al., 2012) (Supplementary Table S1). Overall, the primers and probes of this assay have a high chance of detection to influenza B viruses of both lineages.

Assay performances for influenza B virus detection and lineage differentiation

The performance of this assay for detecting influenza B viruses was first determined by using plasmids containing Victoria and Yamagata HA. This assay can detect both viral lineages with similar performances (Supplementary Figure S1A). The assay has a linear dynamic range from 101 to 108 gene copies/reaction. The assay was also tested for its reproducibility by using these DNA templates (N=6; Table 1). Reactions with ≥100 copies of the HA gene were all positive in the assay. Using probit regression analysis, the target concentration at which >95% of the assay could be expected to yield positive results for influenza B virus was 28.4 copies per reaction (Victoria lineage: 22.8 copies/reaction and Yamagata lineage: 30.3 copies/reaction). Intra-assay precision of the assay was determined by calculating the coefficient of variation (CV%) for each dilution point (Table 1). This assay achieved a high level of intra-assay precision as none of the dilution points have a CV% value higher than 3%.

Table 1.

Estimates of intra-assay precision by coefficient of variation (CV%) calculation

| Plasmid (Number of replicates) | HA plasmid concentration (copies/reaction) | Mean Ct | Standard deviation (Ct) | CV% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Victoria lineage HA (N=6) | 1.00E+08 | 13.048 | 0.323 | 2.475 |

| 1.00E+07 | 16.302 | 0.372 | 2.281 | |

| 1.00E+06 | 20.438 | 0.478 | 2.340 | |

| 1.00E+05 | 24.284 | 0.462 | 1.901 | |

| 1.00E+04 | 28.067 | 0.533 | 1.898 | |

| 1.00E+03 | 31.812 | 0.579 | 1.820 | |

| 1.00E+02 | 35.663 | 0.779 | 2.185 | |

| 1.00E+01* | 37.876 | 0.503 | 1.328 | |

| Yamagata lineage (N=6) | 1.00E+08 | 12.455 | 0.374 | 3.000 |

| 1.00E+07 | 15.646 | 0.288 | 1.842 | |

| 1.00E +06 | 19.701 | 0.301 | 1.530 | |

| 1.00E+05 | 23.499 | 0.386 | 1.643 | |

| 1.00E+04 | 27.023 | 0.499 | 1.848 | |

| 1.00E+03 | 30.890 | 0.729 | 2.359 | |

| 1.00E+02 | 34.793 | 0.492 | 1.415 | |

| 1.00E+01** | 37.119 | 0.815 | 2.196 |

4 out of 6 were positive, negative reactions were not included in the calculation for data of this table

3 out of 6 were positive, negative reactions were not included in the calculation for data of this table

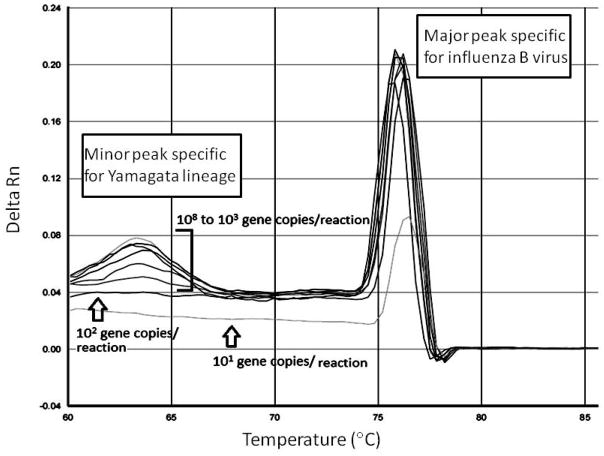

The Victoria lineage-specific probe yielded consistently positive results in reactions containing ≥ 100 copies of its target (N=6; Supplementary Figure S1B). By contrast, the Yamagata lineage specific probe only detected consistently its target at a concentration of 1000 copies per reaction (N=6; Figure 1). The signals from these two probes were associated positively with the copy number of their targets, but these two probes did not give the desired signals in reactions containing viral sequences derived from the other lineage.

Figure 1.

Melting curve analysis of PCR products of Yamagata lineage. Signals from reactions with various concentrations of positive controls (108 to 10 copies per reaction) are indicated. The x-axis denotes the temperature (°C), and the y-axis denotes the change of fluorescence intensity (Delta Rn). Positive signals represent influenza B virus and Yamagata lineage are shown as indicated.

Influenza B virus detection and lineage differentiation using primary clinical specimens

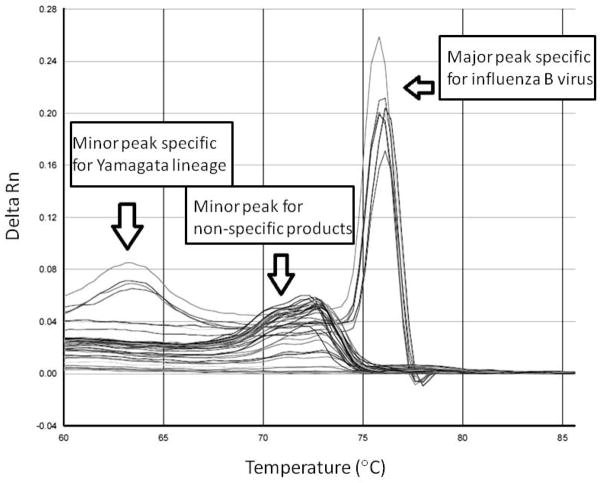

A panel of nasopharyngeal aspirate and throat swab samples confirmed previously to be positive for influenza B virus (n=108) were tested by the assay. Plasmids with HA derived from Yamagata and Victoria lineages were used as positive controls in each run. Test results were considered to be positive when the quantitated copy number is within the reportable range of the assay (102–108 copies/reaction) and the presence of influenza B-specific peak (~76°C) in the melting curve analysis (Figure 2). Of the 108 Influenza B virus-positive specimens, 103 were tested positive by this assay with a quantitation from 298 to 5.28×107 copies/reaction. Five samples were initially negative in this test. By doubling the viral RNA input in the reaction, 2 of these negative specimens became positive in the assays, suggesting that the amount of viral RNA in these 2 samples were close to the detection limit of the assay.

Figure 2.

Melting curve analysis of PCR products of studied clinical specimens. The x-axis denotes the temperature (°C), and the y-axis denotes the change of fluorescence intensity (Delta Rn). Signals represent influenza B virus, Yamagata lineage and non-specific PCR products are shown as indicated.

The assay was evaluated by testing a panel of 60 Influenza B-negative specimens. With an exception of one sample (see below), none of these control specimens were tested positive in this assay. Although roughly half of the assay reactions had non-specific amplification, these non-specific products were distinguished easily from the desired products in the melting curve analysis (Figure 2). More importantly, this non-specific peak had never been found in influenza B positive samples. A specimen which was found previously to be positive for respiratory syncytial virus had a positive melting curve signal in the assay, suggesting this was a case co-infected by two different viruses. The presence of influenza B virus in this particular sample was confirmed by using an independent RT-PCR protocol for influenza B virus detection (http://www.who.int/influenza/resources/documents/molecular_diagnosis_influenza_virus_humans_update_201108.pdf; data not shown).

Of 105 samples that were PCR positive for influenza B viruses, lineage-specific signals were detected in all specimens, in which 59 were of Victoria lineage and 46 were of Yamagata lineage. None of these specimens were positive for both lineages. To validate these results, the HA gene in each of these samples were amplified by manual RT-PCR and all the desired PCR products were analyzed by standard Sanger sequencing. The sequencing results agreed perfectly with those observed from the lineage differentiation tests.

Discussion

In this study a LATE-PCR based assay was developed to detect influenza B virus and to differentiate two major influenza B viral lineages in a single reaction. This novel assay aims to provide a high-throughput, rapid and convenient alternative for detection and lineage differentiation in a single PCR. It should be noted that the approach can detect signals from influenza B virus, Yamagata lineage and Victoria lineage in a single reaction. In the scenario when the targeted sequence has several major mismatches to the probes, the tested sample can still be reported to be influenza B positive by this assay.

Traditional asymmetric PCR is known to lower the amplification efficiency and sensitivity in product-based detection methods such as SYBR Green, as the limited primer concentration on one side forces the amplification to go linear and produce much less double-stranded products (Poddar, 2000; Sanchez et al., 2004). Asymmetric PCRs are often at 60–70% efficiency while most symmetric PCR has over 90% (Sanchez, et al., 2004). However, the single-stranded DNAs in abundance favor signal detection by hybridization probes and molecular beacons (Poddar, 2000; Sanchez, et al., 2004). By employing the simple primer design criteria of LATE-PCR, asymmetric reactions now have comparable replication efficiency as traditional PCR. The asymmetric reaction in this study has achieved 0.863–0.871, which is close to 90%. Further optimization of LATE PCR methods have been reported by modifying primer Tm to TmLimiting − TmExcess ≥5°C, and bringing the TmExcess closer to the Tm of the double stranded amplicon (Pierce et al., 2005). While a stronger hybridization signal could be achieved with this approach, these further modifications lead to difficulties in designing primers and probes for this study because of limited sequence variations between these two lineages (Chen and Holmes, 2008; Zhang, et al., 2012).

Using plasmid DNA as standards, the Yamagata probe was found to be less sensitive than the one for Victoria lineage. However, all clinical samples that were PCR positive for influenza B virus could yield accurate lineage identification results in the same test, indicating the sensitivity issue might not have a great impact on the assay performance for clinical application. Nonetheless, samples that are positive for influenza B virus, but negative for both viral lineages, should be retested with increased amount of viral RNA input in the test. If the tested samples were positive consistently for influenza B virus, but negative for both viral lineages, further characterizations of these samples are recommended to exclude the possibility of detecting novel or atypical influenza B viral strains. In addition, samples that are positive for influenza B virus do not exclude the possibility of multiple respiratory viruses co-infections.

In this study, the assay was designed to use two different detection channels to detect signals from 3 targets (F1: SYBR Green for influenza B virus and Yamagata lineage; F2: Cy5: for Victoria lineage). Theoretically, it is possible to use an additional hydrolysis probe (e.g. Vic-labeled probe) to replace the C3-labelled short oligo for detecting virus of Yamagata lineage. But the use of dual hydrolysis probes in the assay would have to occupy 3 detection channels for detection. It is therefore believed that the current approach is more flexible if one considers to include other targets for clinical diagnosis (e.g. a housekeeping gene as an internal control). In addition, C3-labelled probes are about 10 times more economical than hydrolysis probe.

The current assay can be converted into 1-step RT-PCR format. This might help to reduce sample handling time and risk of cross contamination. At the time of revising this manuscript, we have tested the feasibility of applying this approach in 1-step RT-PCR assay for influenza B virus detection. The preliminary findings are promising, but further assay optimizations and evaluation will be needed. In addition, further assay optimizations for eliminating the non-specific peak observed in the melting curve analysis will be needed.

Overall, the present study has reported a novel real-time assay for the detection and differentiation of Influenza B lineages using LATE-PCR approach. The sensitivity and specificity of this assay enables its usage for influenza B detection, as well as for the surveillance of influenza B viruses.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This project is supported by National Institutes of Health (NIAID contract HSN266200700005C) and Area of Excellence Scheme of the University Grants Committee (Grant AoE/M-12/06).

References

- Ambrose CS, Levin MJ. The rationale for quadrivalent influenza vaccines. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2012;8:81–88. doi: 10.4161/hv.8.1.17623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biere B, Bauer B, Schweiger B. Differentiation of influenza B virus lineages Yamagata and Victoria by real-time PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:1425–1427. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02116-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R, Holmes EC. The evolutionary dynamics of human influenza B virus. J Mol Evol. 2008;66:655–663. doi: 10.1007/s00239-008-9119-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dames S, Margraf RL, Pattison DC, Wittwer CT, Voelkerding KV. Characterization of aberrant melting peaks in unlabeled probe assays. [Evaluation Studies] The Journal of molecular diagnostics : JMD. 2007;9:290–296. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2007.060139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampson AW, Mackenzie JS. The influenza viruses. Med J Aust. 2006;185:S39–43. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay AJ, Gregory V, Douglas AR, Lin YP. The evolution of human influenza viruses. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2001;356:1861–1870. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2001.0999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann E, Mahmood K, Yang CF, Webster RG, Greenberg HB, Kemble G. Rescue of influenza B virus from eight plasmids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:11411–11416. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172393399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MP, Haupt LM, Griffiths LR. Locked nucleic acid (LNA) single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genotype analysis and validation using real-time PCR. Nucleic acids research. 2004;32:e55. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnh046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanegae Y, Sugita S, Endo A, Ishida M, Senya S, Osako K, Nerome K, Oya A. Evolutionary pattern of the hemagglutinin gene of influenza B viruses isolated in Japan: cocirculating lineages in the same epidemic season. J Virol. 1990;64:2860–2865. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.6.2860-2865.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce KE, Sanchez JA, Rice JE, Wangh LJ. Linear-After-The-Exponential (LATE)-PCR: primer design criteria for high yields of specific single-stranded DNA and improved real-time detection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:8609–8614. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501946102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poddar SK. Symmetric vs asymmetric PCR and molecular beacon probe in the detection of a target gene of adenovirus. Mol Cell Probes. 2000;14:25–32. doi: 10.1006/mcpr.1999.0278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulson MD, Wittwer CT. Closed-tube genotyping of apolipoprotein E by isolated-probe PCR with multiple unlabeled probes and high-resolution DNA melting analysis. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural] BioTechniques. 2007;43:87–91. doi: 10.2144/000112459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rota PA, Wallis TR, Harmon MW, Rota JS, Kendal AP, Nerome K. Cocirculation of two distinct evolutionary lineages of influenza type B virus since 1983. Virology. 1990;175:59–68. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90186-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez JA, Pierce KE, Rice JE, Wangh LJ. Linear-after-the-exponential (LATE)-PCR: an advanced method of asymmetric PCR and its uses in quantitative real-time analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:1933–1938. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305476101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright PF, Neumann G, Kawaoka Y. Fields virology. In: Fields BN, Knipe DM, Howley PM, editors. Orthomyxoviruses. 5. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. pp. 1692–1740. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N, Fang S, Wang T, Li J, Cheng X, Zhao C, Wang X, Lv X, Wu C, Zhang R, Cheng J, Xue H, Lu Z. Applicability of a sensitive duplex real-time PCR assay for identifying B/Yamagata and B/Victoria lineages of influenza virus from clinical specimens. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012;93:797–805. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3710-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.