Abstract

Objective

To determine if applying change analysis to the narrative reports made by reviewers of hospital deaths increases the utility of this information in the systematic analysis of patient harm.

Design

Qualitative analysis of causes and contributory factors underlying patient harm in 52 case narratives linked to preventable deaths derived from a retrospective case record review of 1000 deaths in acute National Health Service Trusts in 2009.

Participants

52 preventable hospital deaths.

Setting

England.

Main outcome measures

The nature of problems in care and contributory factors underlying avoidable deaths in hospital.

Results

The change analysis approach enabled explicit characterisation of multiple problems in care, both across the admission and also at the boundary between primary and secondary care, and illuminated how these problems accumulate to cause harm. It demonstrated links between problems and underlying contributory factors and highlighted other threats to quality of care such as standards of end of life management. The method was straightforward to apply to multiple records and achieved good inter-rater reliability.

Conclusion

Analysis of case narratives using change analysis provided a richer picture of healthcare-related harm than the traditional approach, unpacking the nature of the problems, particularly by delineating omissions from acts of commission, thus facilitating more tailored responses to patient harm.

Keywords: preventable death, mortality review, problems in care, narrative accounts, content analysis

Introduction

Over the last decade, there has been a movement towards developing a more systematic understanding of causes of hospital mortality as part of a range of approaches that can be used to identify preventable harm, and so focus improvement efforts.1 Mortality has been the focus of attention of clinicians, the public and politicians following the well-publicised investigations at Bristol Royal Infirmary and Mid Staffordshire National Health Service (NHS) Foundation Trust, both prompted by standardised hospital death rates found to be outside the expected range.2,3 The Modernisation Agency,4 and subsequently the NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement,5 drawing upon the work of the US Institute for Healthcare Improvement,6 have advocated the use of retrospective case record review (RCRR) for this purpose. The approach is also recommended by NHS national safety campaigns in both England and Wales.7,8

RCRR can either be explicit (whereby healthcare professionals assess the quality of processes of care using a set of predetermined criteria) or implicit, allowing clinicians to make judgements using their knowledge and experience. Enhancements to the latter, such as the use of a structured review form and formal training, have been introduced over time in an effort to increase its reliability. Within the research sphere, RCRR, both implicit and explicit, has usually been orientated towards quantitative analyses of the prevalence of patient harm, and its underlying causes or the percentage of patients in which a particular process was satisfactorily undertaken. However, it has been recognised that preventable deaths are often a consequence of the interplay between factors and that omissions in care play an important role especially in frail elderly patients whose defences against such insults are not as robust as those of younger, fitter patients.9 Although the traditional RCRR method does involve delineating the nature of adverse events and contributory factors, usually captured as lists, this may not capture the complexity of how harm arises. Approaches that can capture the complexity of threats to patient safety can augment traditional RCRR.

RCRR has benefitted from the introduction of methods of incident analysis, derived from James Reason’s organisational accident model, and this can highlight both the chains of small events at the clinician/patient interface and wider organisational factors.10–12 These approaches involve in-depth analysis of patient harm and aim to discover root causes. Such tools might be usefully applied to the narrative reports made by reviewers of hospital deaths to increase the utility of this information in the systematic analysis of patient harm.

A large RCRR of 1000 deaths in acute hospitals has recently been conducted to provide a robust estimate of the proportion of preventable deaths in England. This has provided the opportunity to test the use of narrative reports and what they might contribute to traditional case record review.

Method

Details of an RCRR of 1000 hospital deaths in 2009 in 10 randomly selected acute hospitals have been described elsewhere.13 The method was based on previous similar studies.14–18 The reviews were undertaken by 17 recently retired physicians, all of whom had extensive experience as generalists, supported by training and expert reviewer advice. For each case, in addition to a structured set of questions, reviewers were asked to provide a brief narrative account (up to one A4 page) of the circumstances.

The narrative accounts from the 52 deaths judged preventable were transcribed from the review form. Of the range of root cause analysis tools available for qualitative analysis of causes and contributory factors underlying harm, we chose ‘change analysis’ as the most suitable tool. The approach enabled specification and categorisation of problems in care within the narratives using a constant comparison approach between theoretical ‘problem free’ care and what actually happened in practice. The categories were based on those developed by Woloshynowych et al.19 In addition, the Contributory Factor Classification Framework (developed by Charles Vincent and colleagues) was used to categorise contributory factors into nine major groups: patient, staff, task, communication, equipment, work environment, organisational, education and training, and team. Underlying subcategories were also used.12

The method was applied to five cases by two independent reviewers (HH and FH). They then discussed any discrepancies in their findings and made adjustments to the process before all 52 cases were reviewed by HH. One-third of cases were also reviewed by FH to test inter-rater reliability. Reviewers agreed on problems in care in 71% of cases (Kappa coefficient = 0.64 indicating substantial agreement) and on contributory factors in 64% (Kappa coefficient = 0.56 indicating moderate agreement).

The problems in care and contributory factors coded under each of the categories and subcategories were summed to give an indication of relative distributions.

Results

Identifying multiple problems in care

Using the process of change analysis enabled multiple problems in care that cluster in broad categories to be identified, thus defining the nature of the problem more precisely, particularly delineating omissions from acts of commission.

For instance, in Case 1 (Table 1), using the traditional RCRR approach, the original physician reviewer checked the following problem category boxes on the structured review form: other, drugs and fluids, and diagnosis. Our method shows that there were three discrete problems in the ‘Other’ category and two in the ‘Drugs and Fluids’ category. The case also illustrates how multiple problems can be more easily linked to the stage of care at which they occur. Importantly, the change analysis enables connection of contributory factors to specific problems, highlighting the interplay between them.

Table 1.

Case 1.

| Original narrative | A man in his early 70s with known dementia who required considerable help from family and who frequently wandered, was found in a confused state on a bus. Taken by ambulance to hospital. In A&E observations, urinalysis and blood tests showed no abnormality. The patient was admitted to a medical ward and because he was restless, aggressive and confused on the ward he was sedated. Assessments commenced to determine whether he would be able to return to his home situation. Two weeks later his condition deteriorated suddenly when he developed coughing, tachycardia and reduced oxygen saturations. The working diagnosis was aspiration pneumonia and intravenous fluids and antibiotics were started along with physiotherapy. The patient was transferred to the High Dependency Unit for external respiratory support. Respiratory team review recommended a CTPA which he had next day. It showed bilateral pulmonary embolism and left lower lobe consolidation. No evidence was found that the patient had been given venous thromboembolism prophylaxis up to this point. Anticoagulants were added to his regime. Once stabilised he was transferred to a care of the elderly ward. He deteriorated again three days later and it was decided that as the current ward was unable to provide ‘full care’ active treatment was stopped and the end of life pathway commenced. | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Problem in care | Inappropriate admission | Sedation used to control patients behaviour | Failure to provide thromboprophylaxis | Discharge delayed by social factors | Pulmonary embolus misdiagnosed as aspiration | Move to end of life care predicated on ward’s ability to cope with the necessary intensity of treatment | |||||||

| Problem category | Other | Drugs and fluids | Drugs and fluids | Other | Diagnosis | Other | |||||||

| Contributory factors | Availability of alternatives | Effectiveness of communication across health and social care | Risk awareness | Admission to an acute medical ward | Risk awareness | Adherence to protocols | Availability of alternatives | Use of all available information during the diagnostic process | Staff skill mix | Nursing work load | |||

| Contributory factor: subcategory | Organisation: structure | Communication: partnership working | Education and training: knowledge | Environment: staffing | Education and training: knowledge | Task: guidelines, policies and proce dures | Organisation: structure | Work environment system design | Communication: partnership working | Staff: cognitive expectation/confirmation bias | Education and training: knowledge | Environment: skill mix and workload | Organisation: safety priorities |

Identifying problems in care across the admission

Cases 2 and 3 (Tables 2 and 3) illustrate how the approach can identify the accumulation of harm across the admission. In addition, it helps identify how harm generated prior to the admission can be compounded by further poor care once the patient is in hospital. For example, poor monitoring of warfarin with subsequent bleeding was the most common monitoring problem originating prior to admission and two-thirds of these patients encountered a further problem related to anticoagulation which contributed to their deaths. Similarly, among surgical patients, interaction between failure to monitor preoperative clinical observations and thus optimise status before the procedure was compounded by poor management of postoperative fluids contributing to one-third of preventable surgical deaths.

Table 2.

Case 2.

| Original narrative | A female in her early 80s on warfarin developed an infected finger. Her GP prescribed two antibiotics (flucloxacillin and sodium fusidate) The patient was admitted when the condition failed to improve. On admission the finger was found to be draining pus and an X-ray confirmed osteomyelitis. Flucloxacillin was switched to intravenous. Clotting status was not checked for next 2 days while warfarin continued at normal dose. On day 3, ‘blood in the stools’ was noted by nursing staff. In the evening of day 4 the patient’s level of anticoagulation was found to be well above the therapeutic range (INR 10). Reversal was not commenced until 3 hours after the nurses received this result. It was recorded at the time that no beriflex was available on the ward and the patient received fresh frozen plasma and Vitamin K. Despite treatment including transfusion of blood she continued to bleed and died. | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Problem in care | Prescription of antibiotics known to interact with warfarin by GP without close monitoring of warfarin levels | Failure to assess the risk of drug interaction on admission | Failure to monitor warfarin levels for the first 2 days after admission | Anticoagulation levels not known to medical team for more than 24 h after bleeding first noted | First choice medication not available on ward overnight | ||||

| Problem category | Drugs and fluids | Inappropriate/inadequate assessment | Clinical monitoring | Inappropriate/inadequate assessment | Clinical monitoring | Drugs and fluids | |||

| Contributory factors | Risk awareness | Risk awareness | Narrow versus wholistic approach to assessment | Use of monitoring plans | Admission to orthopaedic ward | Communication among clinical team | Medicine management policies | ||

| Contributory factor: subcategory | Education and training: lack of knowledge | Education and training: lack of knowledge | Education and training: supervision | Team: leadership decision-making | Task: guidelines, policies and procedures | Work environment: staffing: inappropriate skill mix | Communication: ineffective information flows | Organisation: safety priorities | Work environment |

Table 3.

Case 3.

| Original narrative | Elderly female admitted by ambulance after waking distressed, breathless, coughing yellow sputum. Chest X-ray (and signs) consistent with left lower lobe pneumonia. Her urea was 9.7 and creatinine 107 indicating fluid depletion. The next day a CT scan showed left lung consolidation and dilated oesophagus with food residue. Patient diagnosed with achalasia and put nil by mouth. Treated with appropriate antibiotics leading to improvement. A swallowing review 2 days later confirmed dysphagia (attributed to previous CVAs) and suggested the patient stay nil by mouth. Three days later she tripped over drip stand while going to toilet and fractured the right neck of femur. The following day a right dynamic hip screw was inserted under general anaesthetic. The day after her operation she became oliguric leading to acute renal failure. Despite fluid challenges there was no improvement in urine output nor in low BP. Decision taken not to start haemofiltration because more likely to be burden than a benefit. Patient noted to have received 7 L of fluid over the 6 days prior to surgery. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Problem in care | Fluid balance was not adequately monitored | Speech and Language team left no clear plan for management of dysphagia | Failure to prescribe fluid replacement | Fall over drip stand leading to fracture | |

| Problem category | Clinical monitoring | Inadequate/incomplete assessment | Drugs and fluids | Other | |

| Contributory factors | Use of monitoring plans | Adherence to guidelines | Communication among clinical teams | Understanding of fluid loss during acute illness | Identification and mitigation of falls risk |

| Contributory factor: subcategory | Team: leadership-decision making | Task: guidelines, policies and procedures | Communication: ineffective information flows | Education and training: lack of knowledge | Task: guidelines policies and procedures |

Nature of problems in care and contributory factors

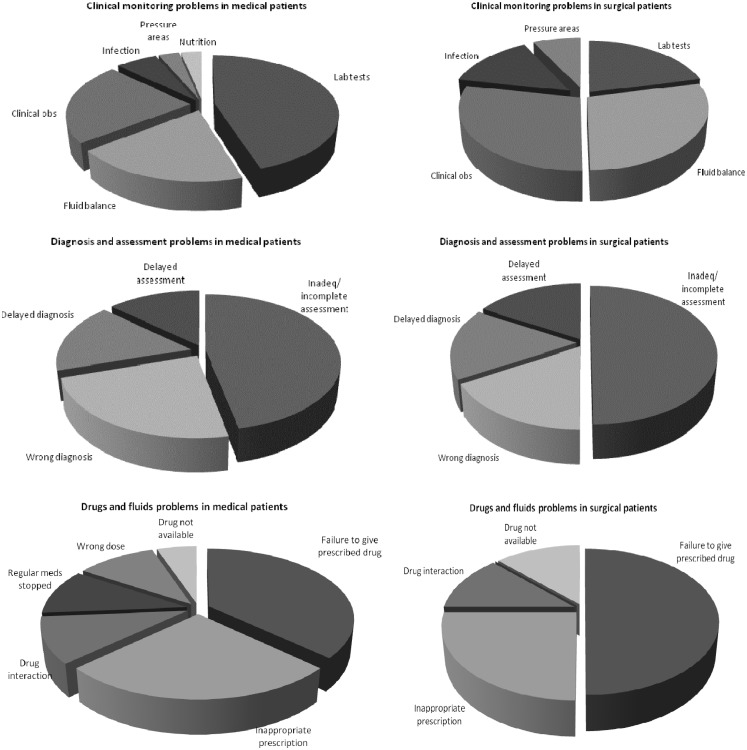

Analysing the narrative accounts led to an average of three (range, 1–8) problems in care associated with preventable death per case being identified with over 70% of these being related to omissions in care. Figure 1 shows how the distribution of problem subcategories differed between medical and surgical patients. For instance, issues with laboratory tests accounted for a larger proportion of clinical monitoring problems in medical patients than surgical patients, while drug omissions formed a larger proportion of drug and fluid problems in surgical than in medical patients.

Figure 1.

Pie charts showing the distribution of problem in care subtypes across medical and surgical preventable deaths.

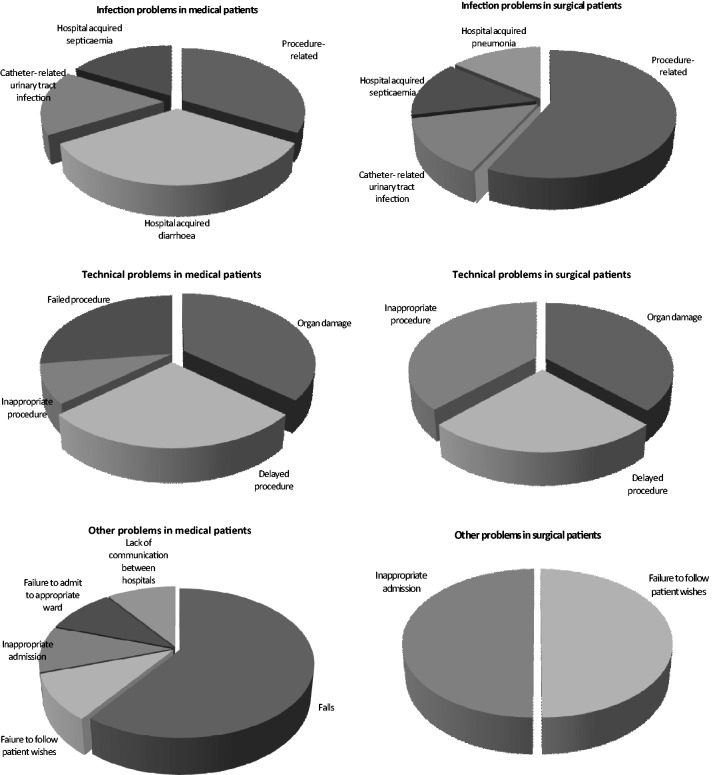

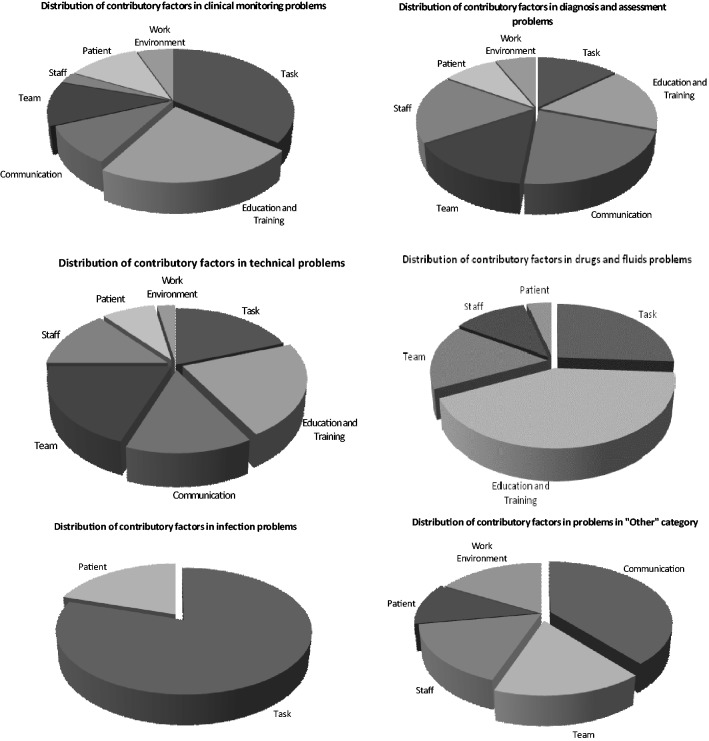

An average of five (range, 1–10) contributory factors were identified per patient (Figure 2) with subtypes differing across the different problem categories.

Figure 2.

Pie charts showing the distribution of contributory factors across different categories of problems in care.

Change analysis can identify other aspects of the quality of healthcare. For example, Case 1 (Table 1) highlights issues with end of life management, and in Case 4 (Table 4) a cancer diagnosis led to an increased risk of misdiagnosis.

Table 4.

Case 4.

| Original narrative | A middle-aged diabetic with renal impairment with a previous history of bladder carcinoma treated with radiotherapy 8 months before this admission. He had experienced a myocardial infarct following intractable haematuria during treatment of the cancer. All had settled down with no evidence of progression. Referred by GP with persistent anaemia (Hb 9.10) increased breathlessness, leg oedema and ascites. GP suggested a diagnosis of left ventricular failure. On the post-take ward round examination JVP noted to be ‘up’ and gross oedema. Primary working diagnosis was malignant ascites and a diagnostic tap was undertaken. Four days after admission a further 12 L of ascitic fluid was drained (over 7 hours) by SpR and replaced with 20% albumen. The same night the patient had a myocardial infarction and went on to develop multiorgan failure over next few days. No malignant cells were found in the ascitic fluid. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Problem in care | Indications of cardiac failure did not trigger further investigations | Working diagnosis of malignant ascites was made despite indications of heart failure | Ascitic drainage performed although working diagnosis not confirmed | Excessive volume of fluid drained | |||

| Problem category | Inadequate/incomplete assessment | Wrong diagnosis | Inappropriate procedure | Inappropriate procedure | |||

| Contributory factors | Weight given to different assessment findings | Communication of concerns across primary/secondary care interface | ‘Diagnostic overshadowing’ from cancer history | Working diagnosis seen as actual diagnosis | Lack of awareness of risks | No clear plan for monitoring output or observations | Performed on a ward unfamiliar with ascites drains |

| Contributory factor: subcategory | Education and training | Communication: ineffective information flows | Staff: cognitive-expectation/confirmation bias | Team: lack of shared understanding | Education and training | Team: leadership decision-making | Work environment |

Discussion

Principal findings and interpretation

Change analysis, a tool developed for root cause analysis, was used to mine case narratives from previous case record-based mortality review to provide a richer picture of the nature of harm associated with preventable deaths than traditional RCRR approaches. The approach was feasible for use on the relatively short narratives that accompany mortality reviews and was time efficient (15–20 min per case). It was sufficiently robust in identifying problems and contributory factors, with good inter-rater reliability.

Change analysis identified multiple components underlying single problems, the balance between acts of omission and commission and the interplay between contributory factors. The nature of harm generation across the admission and at the interface between healthcare providers could be gauged. The collation of findings from the analysis can be used to demonstrate how distributions of problems and their contributory factors vary across different patient groups.

We found that problems generated when processes of care go wrong accumulated across admissions. Most commonly, problems related to clinical monitoring, to assessment and diagnosis, and to drugs and fluid problems combined and led to preventable deaths. Contributory factors shed light on the issues underlying these problems in care and varied in distribution according to problem subcategories.

Strengths and limitations

Examining the narratives of deaths judged to be preventable allowed a deeper understanding of the nature of problems in care underlying such deaths and was particularly good at identifying multiple omissions across the care pathway. There are, however, three potential limitations. First, the narratives were short, ranging from one paragraph to one sheet of A4. Missing details are likely to have led to a failure to identify some problems and their contributory factors. Even with the availability of the full admission record, it is unlikely that retrospective review can find the full spectrum of hospital-related patient harm.

Second, clinicians are more likely to record clinical details than factors related to organisational policies and processes; therefore, reviews of records are more likely to identify clinical–technical aspects of care, especially those related to human error, rather than system-wide issues.20,21 For the same reasons, contributory factors are often not explicitly recorded and factors such as a lack of knowledge have to be inferred from the nature of the problem itself. And third, we knew we were reviewing narratives of patients who had experienced a preventable death and such hindsight bias may have led us to identifying problems, even if the evidence for these was scant.

Implications and conclusions

As the majority of patients who die in acute hospitals are elderly and frail with multiple co-morbidities, hospital death reviews provide a window on how well healthcare is delivered to those with complex conditions. Their care tests the safety of hospital systems, with fragmented and poorly coordinated care increasing the opportunity for omissions and ensuing harm, especially in those with fragile health states.3 Our findings confirm those from previous large RCRR studies, both in the predominance of omissions as a major factor in serious harm and the nature of the problems in care underpinning preventable deaths.15,18,22 Our findings are also consistent with the work of James Reason, who showed how system-level factors such as poor communication, team work or task design enable problems at the patient–clinician interface to occur.

Mortality reviews can highlight key areas of risk thus allowing more focused targeting of actions to reduce these risks. Such reviews, based on retrospective review of medical records are increasingly used as a quality and safety improvement tool in NHS hospitals. Some hospitals in England are reviewing all deaths, while others are using samples derived in a variety of ways. As increasing proportions of deaths undergo review, it is important to consider how to maximise the potential for learning. Categorisation of problems using traditional RCRR does not provide a sufficiently precise picture of the nature of the problems within in any given category, how these problems link together and how they are associated with specific contributory factors. While useful for monitoring trends over time, the information generated has limited value for understanding the complex nature of harm evolution and the influence of multiple interacting contributory factors. Although root cause analysis was developed for this purpose, such an in-depth multidisciplinary approach is not feasible for assessing large numbers of cases.

Applying change analysis to case narratives identifies the scope of problems in care and their linked contributory factors across the admission, offering the opportunity to identify high-risk areas and better targeting of appropriate interventions. Drawing as precise a picture as possible of the nature of harm makes mortality review a powerful tool for improving quality, especially if this information can be efficiently gathered across multiple cases. Further research will be required to determine the acceptability of this approach among NHS staff undertaking mortality reviews and to determine the impact of the analyses on quality and safety improvement. Given that problems in care span initial assessment through to complex treatment, resulting improvements have the potential to provide safer environments for all patients.

Declarations

Competing interests

None declared

Funding

The work was supported by the National Institute of Health Research – Research for Patient Benefit Programme (PB-PG-1207-15215). The funders had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or composition of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. The sponsor was London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

Ethical approval

Ethics approval was received from the UK National Research Ethics Service via the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery and the Institute of Neurology joint multi-centre research ethics committee (09/H0716/33) and research governance approval was granted by each participating Trust.

Guarantor

HH

Contributorship

HH, CV and FH were responsible for the original study idea and design. HH and FH refined the change analysis approach. HH applied it to all case narratives and FH undertook double review of a third of these. All authors contributed to the data interpretation. HH drafted the manuscript and all authors contributed to its revision.

Acknowledgements

We thank the 10 English acute hospital Trusts and the PRISM case record reviewers for supplying the background data for this study. We also thank the National Institute of Health Research, Research for Patient Benefit Programme for funding.

Provenance

Not commissioned; peer-reviewed by Trisha Greenhalgh

References

- 1.Sari AB, Sheldon TA, Cracknell A, et al. Extent, nature and consequences of adverse events: results of a retrospective casenote review in a large NHS hospital. Qual Saf Health Care 2007; 16: 434–439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Department of Health. Learning from Bristol: The Report of the Public Enquiry into Children's Heart Surgery at the Bristol Royal Infirmary 1984–1995, London: HMSO, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Francis R. Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry, London: The Stationary Office, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Modernisation Agency. A Matter of Life and Death. Increasing Reliability and Quality to Reduce Hospital Mortality and Improve End of Life Care, London: Department of Health, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 5.NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement. Reducing Avoidable Deaths (Medical Directors), London: Department of Health, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Move Your Dot. Measuring, Evaluating and Reducing Hospital Mortality Rates. Innovation Series 2003, Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 7.1000 Lives Plus. Providing Assurance, Driving Improvement. Learning from Mortality and Harm Reviews in NHS Wales. Improving Healthcare White Paper Series Number 10, Cardiff: 1000 Lives Plus, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patient Safety First Campaign. Patient Safety First 2008 to 2010. The Campaign Review, London: National Patient Safety Agency, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mold JW, Stein HF. The cascade effect in the clinical care of patients. N Engl J Med 1986; 314: 512–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spath P. Error Reduction in Healthcare: A Systems Approach to Improving Patient Safety, Washington, DC: AHA Press, 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reason JT. Human Error, New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990 [Google Scholar]

- 12. Taylor-Adams S and Vincent C. Systems analysis of clinical incidents: the London protocol. London: Imperial College London, 2004.

- 13.Hogan H, Healey F, Neale G, Thomson R, Vincent C, Black N. Preventable deaths due to problems in care in English acute hospitals: a retrospective case record review study. BMJ Qual Saf 2012; 21: 737–745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brennan TA, Leape LL, Laird NM, et al. Incidence of adverse events and negligence in hospitalized patients. Results of the Harvard medical practice study I. N Engl J Med 1991; 324: 370–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilson R, Runciman W, Gibberd R, Harrison B, Hamilton J. Quality in Australian health care study. Med J Aust 1995; 163: 472–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vincent C, Neale G, Woloshynowych M. Adverse events in British hospitals: preliminary retrospective record review. BMJ 2001; 322: 517–519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayward R, Hofer T. Estimating hospital deaths due to medical error – Preventability is in the eye of the reviewer. JAMA 2001; 286: 415–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zegers M, De Bruijne MC, Wagner C, et al. Adverse events and potentially preventable deaths in Dutch hospitals: results of a retrospective patient record review study. Qual Saf Health Care 2009; 18: 297–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Woloshynowych M, Neale G, Vincent C. Case record review of adverse events: a new approach. Qual Saf Health Care 2003; 12: 411–415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smits M, Zegers M, Groenewegen PP, et al. Exploring the causes of adverse events in hospitals and potential prevention strategies. Qual Saf Health Care 2010; 19: e5–e5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bates D, Cullen D, Laird N. Incidence of adverse drug events and potential adverse drug events. Implications for prevention. JAMA 1995; 274: 29–34 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leape LL, Brennan TA, Laird N, et al. The nature of adverse events in hospitalized patients. Results of the Harvard medical practice study II. N Engl J Med 1991; 324: 377–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]