Introduction

There are undoubtedly very real disadvantages or barriers to accessing higher education (HE) and the medical profession for people from low socioeconomic backgrounds. Specifically designed widening access (WA) programmes can help overcome these barriers as well as increase student retention and progression, which can also be problematic for students from disadvantaged backgrounds.1,2 In a review of WA research, Gorard et al.1 suggested that the term ‘barrier’ may be misleading as it implies something tangible which can be removed and the associated problems will then automatically be resolved. In reality factors that are termed barriers are frequently more complexly ingrained both in the individual and in society. The review identified three key types of barrier which potentially disadvantage the student in accessing HE1: situational barriers which include cost, time and distance of the learning opportunity; institutional barriers that result from availability and flexibility of opportunities presented by institutions; and dispositional barriers that relate to the individual and their own attitudes and motivation towards education. Dispositional barriers can arise from a variety of factors, including previous educational experience and attainment, family and social influences, and the influence and level of support afforded by schools and colleges to entering HE.

The three key barriers all apply to HE but there are further barriers to professions such as medicine, which is still considered by some to be an elitist profession and has traditionally been seen to be a calling of the male, white, middle and higher classes.3,4 Mathers and Parry5 proposed the term ‘identity conflict’ resulting from cultural norms of working class families and schools which negatively impact on the expectations and self-identity of students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds. This resulted in students being unable to see themselves as members of the medical profession. The inhibitory effect of teachers on potential medical students has also been reported, where students from low socioeconomic backgrounds are told they are not ‘doctor material’.6

It is clear that such ingrained cultural beliefs and behaviours negatively influence students from low socioeconomic backgrounds regarding their access to this profession. These attitudes are factors in dispositional barriers that WA programmes have only a limited ability to address in the short term; however, increasing the number of doctors from under-represented groups may make the profession more accessible to such groups in the future.

Addressing the barriers to medicine

The BM6 programme at the University of Southampton, introduced in 2002, aims to widen access to medicine for students from low socioeconomic backgrounds. The programme has a bespoke recruitment and admissions process (detailed in the companion paper, part 1) to overcome many of the institutional and dispositional barriers to HE and the profession alongside a tailored curriculum.

Year 0 curriculum

The Year 0 curriculum is specifically designed to fill the attainment gap while developing confidence and other key skills, therefore, smoothing the transition to Year 1. The relatively small group of 30 students together with the teaching approach creates a culture of active and therefore deep learning, questioning and a range of delivery methods to prepare them for the rest of their programme.7–9 The teaching sessions are largely interactive with a number of weekly tutorials. The teaching and tutorial sessions frequently include case-based, group and pair-sharing learning.10 Students are given weekly preparatory research questions to increase confidence and encourage engagement in teaching sessions. Also due to the small number of key lecturers the students receive a personalised learning experience, academic and personal problems can often be identified early and appropriate support strategies can be put in place by working with the student and support services available.

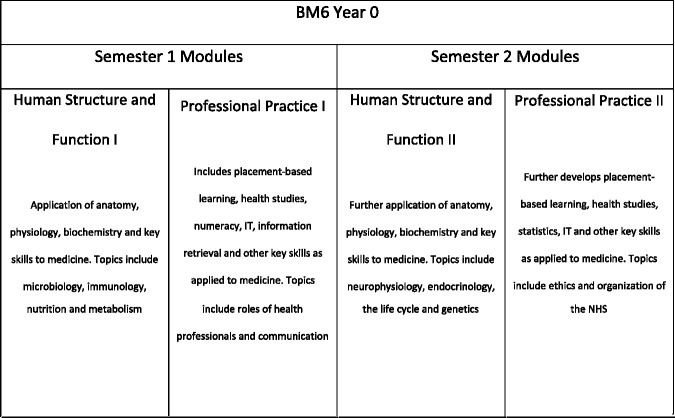

The BM6 curriculum is not a repeat of A levels, it is matched to the students’ academic entry criteria and provides learning relevant to the students’ diverse backgrounds. All the subjects covered are applied to medicine (Figure 1) and provide students with a good introduction to key undergraduate skills, mapped to the learning outcomes of the General Medical Council’s Duties of a Doctor.11 Student presentations are an important feature of BM6 as they enhance self-confidence and communication skills. The group presentations encourage modelling of team working and individual presentations allow the students to demonstrate their understanding of scientific topics and professional behaviours in more detail.

Figure 1.

An outline of the Year 0 curriculum. Year 0 of the BM6 programme is based on an academic year of two semesters, each consisting of two compulsory modules.

A unique aspect of the curriculum is the Professional Practice modules. All students experience a range of observational healthcare placements, in both primary and secondary care, enabling them to gain experience in environments that previously might have been inaccessible to them. Each student experiences three different healthcare settings, e.g. General Practice, hospital wards and Mental Health services, and undertakes a total of 11 placement sessions in Year 0. The placements provide students with a real insight into multidisciplinary team working and the patient experience, combining active and observational learning,12 which facilitates the development of professionalism and key skills of observation, reflection, recording and applying theory to practice.

Each professional practice module has three topics that students cover through lectures in professional studies and health studies (psychology and sociology as applied to healthcare) and placements. One topic is ‘ethical issues in health care’; its aim is to enable students to consider how ethical issues are presented and addressed in practice. Underpinning theory is delivered in the lectures in preparation for observational experience on placements. The specific learning outcomes for this topic are ‘identify possible ethical issues in health care’ and ‘assess how ethical challenges are addressed by health professionals’. Students are given suggestions for observational/enquiry-based evidence gathering, which include questions such as: ‘what are common examples of ethical issues encountered in the placement and less common ones?’, ‘what examples are there of patient choice and autonomy in treatment and care?’ and ‘what examples are there on placement of how consent to treatment is handled?’

Placement facilitators are informed of the suggestions for the evidence gathering given to the students and therefore can prepare for discussions and provide access to relevant healthcare examples where possible. This particular topic is assessed through an individual presentation on an ethical issue related to placements which forms a part of their portfolio for this module.

The professional practice modules focus on the core features of professionalism with greater emphasis and time than is often possible in later years. This is important in a group of students who are less likely to have many role models of a professional in their family and also less likely to have a culture of continuous life-long learning. The experience of shadowing health professionals on placement also allows students to confirm or otherwise their motivation for the medical profession and to be exposed to the core features of professional behaviour.

Each module is assessed by coursework and examinations and the assessment methods are similar to those used in Years 1–3 of the programme, again with the aim of smoothing transition and increasing confidence.

Particular emphasis is given to frequent, timely and constructive feedback to individual students on their performance in coursework, on placements and in examinations. Students’ evaluations of the programme are overwhelmingly positive. The placements, applied nature of the curriculum and support, are particularly valued. In addition, the programme’s development over the years owes much to suggestions and ideas from BM6 students themselves.

The curriculum content and design is aimed not only at increasing knowledge and traditional key skills but also at raising confidence through a variety of methods including active learning and problem solving, numerous individual and group presentations and early contact with patients and healthcare professionals on placements. Year 0 also helps students to develop essential life skills such as self-discipline, responsibility and organisation. This is achieved through a high level of group work, peer assessment, placement preparation and attendance as well as preparation for the formative and summative assessments alongside weekly research tasks and directed lecture preparation. All of these skills greatly help students overcome many dispositional barriers and to integrate and succeed in the following five years at medical school.

Student support

A key feature of the BM6 Year 0 is the high level of support provided. Keeping the group small enables the students to have a personalised learning experience. The staff know the students well and can closely monitor their academic and pastoral needs which, because of their backgrounds, can be particularly challenging requiring high levels of support.2,13 Peer support is also excellent within the group and between cohorts. In order to facilitate integration of BM6 students into Year 1 they are eligible for University accommodation in Year 0 and Year 1. The Faculty of Medicine also provides each BM6 student with a non-repayable £1000 bursary in their Year 0.

Many of the additional challenges faced by BM6 students, which often result from family responsibilities or financial and work-related pressures, cannot be fully addressed by a WA scheme even with high levels of support and these challenges remain with the students in to the successive years. A possible weakness of the BM6 programme is that the high level of support is only offered in Year 0, which may make the successive years more difficult and disadvantage the students in their progression.

Diversifying the workforce and increasing social mobility

The main aim of the BM6 Year 0 is to prepare students to succeed in Years 1–5 of the medical degree programme. The average progression rate from Year 0 to Year 1 of the 290 students enrolled on the BM6 programme between 2002 and 2012 is 90%. Of those students who entered Year 1 between 2003 and 2007 and excluding students who are still studying on the programme, 85% have successfully graduated with a medical degree, 5% have been awarded an exit degree and 3% have received a Diploma of Higher Education. The percentage of BM6 students reaching graduation is lower than traditional and graduate entry programmes at Southampton, for example 95% of students who entered Year 1 of the BM5 programme in 2002 and 2003 successfully graduated with a medical degree. The lower progression figures for BM6 may be a reflection of the key barriers identified earlier in this article, which do not only apply to entry but also to progression in HE.

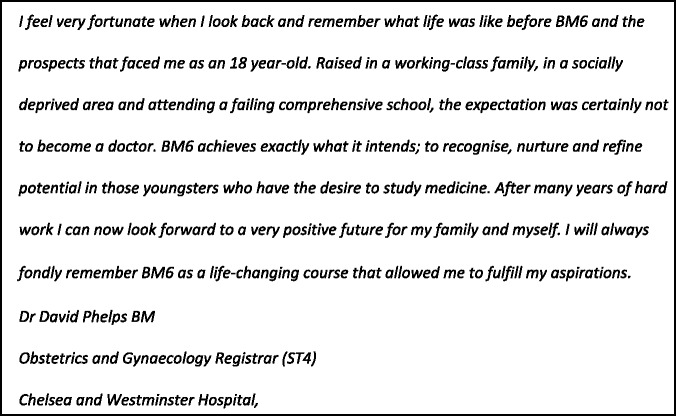

Currently, 110 BM6 students have graduated and qualified as doctors. As a model of good practice, the BM6 programme has been shown to be achieving its aims by raising aspirations and increasing social mobility (Figure 2) while creating a more diversified workforce and addressing the fair access gap identified in the 2012 report ‘university challenge’ and the 2013 report ‘the fair access challenge’.14,15

Figure 2.

A BM6 graduate’s view.

Discussion

A successful WA to medicine programme should not only focus on recruitment and admissions but also on curriculum and supporting students in developing the skills and confidence that will help them succeed in their studies and future careers. The success of the specifically designed BM6 programme is demonstrated by its progression rates, which have contributed to the University of Southampton meeting access agreement targets on state educated students for the Russell Group Universities in England and increasing the numbers of students from low socioeconomic background.15

The total numbers of students from low socioeconomic backgrounds that graduate annually still represent a very small percentage of the total number of new doctors qualifying in the UK. However, each year the BM6 programme adds to the number of doctors from such backgrounds and hence meets its aims. The BM6 programme also successfully meets the aims of the Medical Schools Council,16 the General Medical Council17 and the national agenda14,15 by increasing social mobility and WA to the medical profession.

Declarations

Competing interests

None declared

Funding

None declared

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required for this study. Due consideration was given and advice was sought from the Faculty Ethics Committee.

Guarantor

SC

Contributorship

SC and CB made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work, the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data. CP and LT contributed to the article. All authors were involved in critical revisions and gave final approval of the version to be published

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Professor Jen Cleland for her advice and guidance regarding the structure and presentation of the article.

Provenance

Not commissioned; peer-reviewed by Karen Foster.

References

- 1. Gorard S, Smith E, May H, Thomas L, Adnett N and Slack K. Review of widening participation research: addressing the barriers to participation in higher education. 2006, http://www.ulster.ac.uk/star/resources/gorardbarriers.pdf (accessed December 2013)

- 2.Gorard S, Adnett N, May H, Slack K, Smith E, Thomas L. Overcoming Barriers to Higher Education, Stoke-on-Trent: Trentham Books, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boursicot K, Roberts T. Widening participation in medical education: challenging elitism and exclusion. High Educ Pol 2009; 22: 19–36 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mathers JM, Sitch A, Marsh J, Parry J. Widening access to medical education for under-represented SEC groups: population based cross sectional analysis of UK data, 2002–2006. BMJ 2011; 341: d918–d918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mathers J, Parry J. Why are there so few working-class applicants to medical schools? Learning from the success stories. Med Educ 2009; 43: 219–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McHarg J, Mattick K, Knight LV. Why people apply to medical school: implications for widening participation activities. Med Educ 2007; 41: 815–821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crosby J. Learning in small groups. Med Teach 1996; 18: 189–202 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graffam B. Active learning in medical education: strategies for beginning implementation. Med Teach 2007; 29: 38–42. http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01421590601176398 (2007, accessed December 2013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grant J. Principles of Curriculum Design, Edinburgh: Association for the study of medical education, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cox S. Guide to Using Case Studies for Active Learning. Published by HEA, http://www.heacademy.ac.uk/assets/hlst/documents/resources/ssg_cox_active_learning.pdf (2008, accessed April 2014)

- 11. General Medical Council. Tomorrow’s Doctors: outcomes and standards for undergraduate medical education, http://www.gmc-uk.org/education/undergraduate/tomorrows_doctors_2009_outcomes3.asp (2009, accessed October 2013)

- 12.Fryling MJ, Johnston C, Hayes LJ. Understanding observational learning: an interbehavioral approach. Anal Verbal Behav 2011; 27: 191–203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garlick PB, Brown G. Widening participation in medicine. BMJ 2008; 336: 1111–1113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Milburn A. University Challenge: How Higher Education Can Advance Social Mobility. A progress report by the Independent Reviewer on Social Mobility and Child Poverty, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/independent-reviewer-s-report-on-higher-education (2012, accessed October 2013)

- 15. Social Mobility and Child Poverty Commission. Higher Education: The fair Access Challenge, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/higher-education-the-fair-access-challenge (2013, accessed October 2013)

- 16. Medical Schools Council. Widening Participation, http://www.medschools.ac.uk/AboutUs/Projects/Widening-Participation/Pages/WideningParticipation.aspx (accessed October 2013)

- 17. General Medical Council. Student Selection, http://www.gmc-uk.org/information_for_you/21880.asp (2013, accessed October 2013)