Abstract

Women bear a disproportionate burden of the HIV epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa and account for about 60% of all adults living with HIV in that region. Young women, including adolescent girls, unable to negotiate mutual faithfulness and/or condom use with their male partners are particularly vulnerable. In addition to the high HIV burden, women in Africa also experience high rates of other sexually transmitted infections and unwanted pregnancies. The development of technologies that can simultaneously meet these multiple sexual reproductive health needs would therefore be extremely beneficial in the African setting.

HIV epidemic in Africa

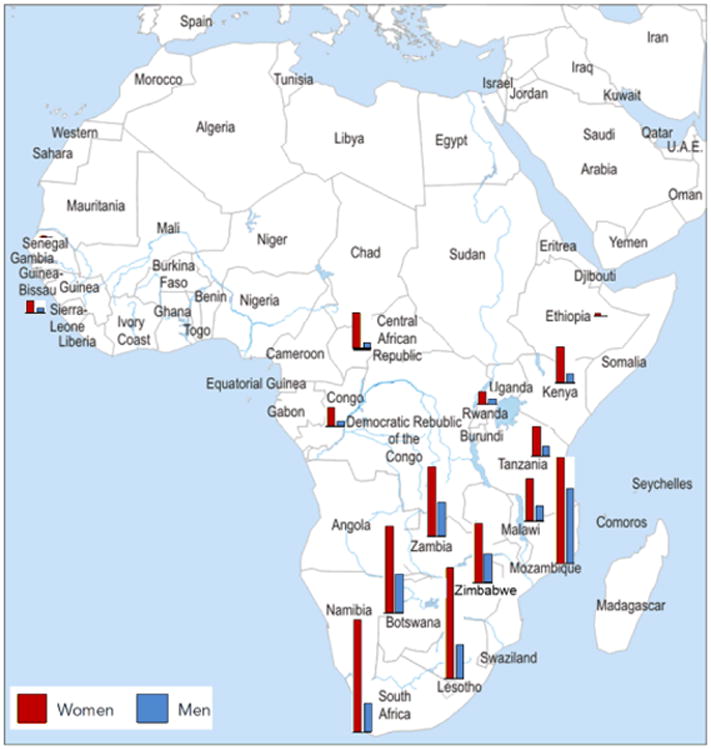

Africa is the worst AIDS affected region of the world, with eastern and southern Africa generally more severely affected than western and northern Africa (Figure 1). The HIV epidemic in Africa was identified in the early 1980s (1), but probably originated several decades before this (2).

Figure 1.

Trends in the a) HIV prevalence and b) number of infection in African between 1990 and 2010. The size of the red circles represents the proportion of people infected. Source: Adapted from UNAIDS AIDSinfo http://www.unaids.org/en/

While the emergence and magnitude of the HIV epidemic varies considerably between individual countries in Africa, the HIV-1 epidemic is now well established within the general population of sub-Saharan Africa where 5% of all adults are estimated to be living with HIV (3). Substantial progress has been made over the last decade in reducing the number of new HIV infections among adults and children and epidemiological trends indicate that most of the HIV epidemics in Africa are either stabilising or declining (3). However, these encouraging trends mask the continued spread of HIV in young women and sub-Saharan Africa still accounts for about 70% (25 million) of the 35.3 million people estimated to be infected with HIV globally in 2012(4). Countries like South Africa, Swaziland, Lesotho, and Malawi continue to experience unprecedented high HIV prevalence and incidence rates (3).

Access to antiretroviral drugs to treat AIDS patients and reduce vertical transmission of HIV has resulted in a 24% decline in AIDS-related mortality since 2005 and almost eliminated HIV infection in infants in some parts of the world. Despite these successes, the majority (70%) of AIDS-related deaths still occur in sub-Saharan Africa (3).

Burden of HIV among young women

Women bear a disproportionate burden of the HIV epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa and account for approximately 60% of all infections in this region (5). HIV-infected women between the ages of 15 and 24 years represent 76% of the total cases in that age group (6). The rapid spread of HIV among adolescent girls and young women in South Africa has been described as explosive (7). National, annual, anonymous seroprevalence surveys in pregnant women utilizing public sector health care facilities demonstrate that HIV prevalence has increased from 0.8% in 1990 to 30.2% in 2010 (8). Although the national HIV prevalence appears to be stabilising in South Africa, these data conceal geographical variations as well as age and gender differences in HIV prevalence and incidence. HIV prevalence among pregnant women, aged 15 to 49 years, is lowest in the Western Cape Province (18.2%) and highest in the KwaZulu-Natal Province, reaching 37.4% in 2011 (8). Five sub-districts within the KwaZulu-Natal Province have recorded HIV prevalence that exceeds 40% (8). Annual cross-sectional surveys of antenatal clinic attendees in one of these high burden sub-districts demonstrate a disturbing rise of HIV infection among young women below the age of 20 years, increasing from 16.6% in 2006 to a 20.8% in 2008 (9). A survey conducted among high school learners in this district shows that the HIV prevalence in girls was 6-fold higher than in boys. An age specific breakdown from this survey indicates that by age 18, 7.1 % of girls are infected with HIV and by age 25 this increases to 24% (9) (Table 1).

Table 1. HIV prevalence in learners in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Adapted from Kharsany et al (2012)(9).

| Age Group (Years) | HIV Prevalence in girls (95% CI) (N=258) | HIV Prevalence in boys (95% CI) (N=230) |

|---|---|---|

| 12-14 | 1.6 (0.1-9.8) | 5.0 (0.4-18.2) |

| 15-16 | 2.6 (0.5-10.1) | 1.1 (0.1-7.0) |

| 17-18 | 7.1 (2.7-16.6) | 0 (0.2-7.3) |

| 19-25 | 24.0 (13.5-36.5) | 0 (0.2-11.2) |

These exceptionally high HIV prevalence rates are being sustained by high HIV incidence rates among young women. Several cohort studies have been conducted in South Africa to measure HIV incidence (10-15). Results from one of these cohort studies conducted between 2002 and 2005 in preparation for a microbicide trial showed that the HIV incidence rate was 6.6 per 100 person-years. Factors that were associated most strongly with HIV seroconversion in this study included being below the age of 24 years, being single, and having an incident sexually transmitted infection (STI)(14). Exceptionally high HIV incidence rates of 14.8 per 100 person-years (95% CI 9.7, 19.8) in women aged 18-35 years (12) and 17.2 per 100 person-years (95% CI 2.1–62.2) in urban women below the age of 20 years have been recorded in certain districts of KwaZulu-Natal (16). More recent data from the CAPRISA 004 tenofovir gel trial, completed in 2010, show that the HIV incidence rate remains high and was 9.1 per 100 person-years among 18 to 40 year old women in the placebo gel arm (17).

One of the key features of the HIV epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa is the age-sex disparity in infection where young women acquire HIV infection much earlier than their male peers. This age-sex disparity was first documented in South Africa in the early 1990's (18) and more recent community based surveys (19) have demonstrated that the same gender disparities remain but the difference in HIV prevalence between young women and men has been exacerbated. Throughout eastern and southern Africa, the prevalence of HIV in adolescent girls far exceeds that of teenage boys, and South Africa has one of the largest absolute ratios between girls and boys (Figure 2).

Figure 2. HIV prevalence (%) among people 15–24 years old, by sex in selected African countries, 2008–2011 (5).

What makes young women more vulnerable to HIV?

Several factors contribute to the increased vulnerability of young women acquiring HIV in sub-Saharan Africa.

Biologically, women appear to be more susceptible to acquiring HIV than men. According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the risk of HIV infection is 1 per 2,000 contacts for the male partner compared to 1 per 1,000 contacts for the female partner in peno-vaginal sex (20). Hence, on average, women are twice as likely to become infected as men after a single sexual encounter (Table 2). Although the biological mechanisms that make women more vulnerable than men in acquiring HIV are not fully understood, inflammation in the female genital tract is emerging as an important risk factor for acquiring HIV (21). In the CAPRISA 004 trial, women with genital inflammation had an almost 3-fold higher risk of HIV acquisition (21).

Table 2. Estimated per-act probability of acquiring HIV from an infected source, by exposure act. Table adapted from (20).

| Type of Exposure | Risk per 10,000 exposures |

|---|---|

| Sexual | |

|

| |

| Receptive anal intercourse | 50 |

| Receptive penile-vaginal intercourse | 10 |

| Insertive anal intercourse | 6.5 |

| Insertive penile-vaginal intercourse | 5 |

| Receptive oral intercourse | Low |

| Insertive oral intercourse | Low |

|

| |

| Parenteral | |

|

| |

| Blood transfusion with infected blood | 9,000 |

| Needle-sharing during injection drug use | 67 |

| Percutaneous (needle-stick) | 30 |

The risk of acquiring HIV also increases with repeated exposure, co-infection with ulcerative STIs (22-24), genital immaturity, receptive anal sex, circumcision status of male sexual partner (25), stage of HIV infection (23, 26) and the susceptibility of the exposed individual.

While young women and girls are possibly more biologically prone to infection, this can only partially explain the large gender differences in HIV prevalence. Discrimination against women and girls in terms of access to education, employment, health care, land and inheritance is common in many low- and middle-income countries (27). Many women, particularly those from impoverished backgrounds, form relationships with men for financial and social security (28). Data from several African countries have shown that young women who have sexual partners who are 5-10 years older than them are at an increased risk for acquiring HIV (29-32).

In addition to the intergenerational sexual coupling patterns, early sexual debut and sexual violence also impact on the vulnerability of young women in acquiring HIV infection in sub-Saharan Africa. On average, young people begin having sex in their teenage years and generally do not use condoms consistently. Studies from South Africa have shown that the likelihood of early sexual debut increases when the first sexual partners are older or if the sex is coerced (33). A younger age of first sexual intercourse is associated with subsequent sexual risk-taking behaviour, such as having multiple partners (34), and an increased risk of acquiring STIs including HIV infection (29, 35). Teenage girls who acquire HIV often drop out of school, which further perpetuates the vulnerability of young women as they transition to adulthood due to the limited economic options available or accessible to those who do not complete high school.

Women who have been subjected to intimate partner violence have also been shown to be at an increased risk for acquiring HIV (36) and often adopt behaviours that place them at an increased risk for acquiring HIV (5). Violence, the fear of violence and stigma and discrimination also discourage women from disclosing their HIV status.

Desperate economic circumstances also force some women to engage in commercial sex for survival, which places them at risk of contracting HIV and transmitting the virus to others. According to the World Health Organisation, prevalence of HIV among sex workers in sub-Saharan Africa is estimated to be 37%. The proportion of HIV prevalence in the general female adult population that is attributable to sex work has been estimated through modelling to be 15% in 2011 (37).

High burden of sexually transmitted infections

STIs are a major global public health problem, resulting in acute illness, severe medical complications, infertility, long-term disability and death in millions of women each year (38). The burden of these STIs is particularly severe in sub-Saharan Africa and especially in young women. The World Health Organisation estimates that 110 million new cases of Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhea, Treponema pallidum (syphilis) and Trichomonas vaginalis occurred in the African region in 2005 (38).

The presence of STIs, particularly those that cause genital ulceration or inflammation have been shown to play an important role in the transmission of HIV by increasing the infectiousness of HIV-infected individuals and the susceptibility of HIV-uninfected individuals (39-42). Herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) for example, which is a lifelong and incurable infection that can cause recurrent and painful genital sores, has been shown to be associated with a 2.8 and 3.4-fold increased risk of HIV acquisition in men and women, respectively, after adjustment for sexual behaviour (43). An estimated 536 million (16.5%) sexually active adults between the ages of 15 and 49 years were infected with HSV-2 in 2003 (44). The burden of HSV-2 infection is highest in sub-Saharan Africa where up to 80% of sexually active women and up to 50% of sexually active men are estimated to be infected (44-46).

Human Papillomaviruses (HPV), which include a highly diverse group of obligate mucosal pathogens capable of infecting and replicating in the genital epithelium, may also increase the risk of acquiring HIV (47). A systematic review of the association between HPV infection and HIV demonstrated that the risk of HIV infection doubled in the presence of HPV (48). In addition to the HIV risk, certain high-risk HPV types have been shown to cause cervical cancer (49). An effective vaccine against HPV has recently become available and could potentially reduce the risk of both HIV and cervical cancer.

Given the strong association between the presence of STIs and the increased risk of acquiring HIV, the treatment of curable STIs would seem like a logical HIV prevention tool. Unfortunately only one trial, which was conducted in Tanzania, has demonstrated a significant reduction in HIV incidence rates following the treatment of STIs (50). Nevertheless, the significant sexual and reproductive health challenge posed by the high burden of curable STIs warrants the scale up of known STI treatments, irrespective of its impact on HIV.

High rates of unintended pregnancies

Besides a high STI burden, women in low- and middle-income countries also experience high rates of unintended pregnancies. According to the Guttmacher Institute, of the 208 million pregnancies that occurred in 2008, about 86 million (41%) were unintended (51). About half (41 million) of these unintended pregnancies were terminated, often under unsafe conditions in non-health facility settings and especially in settings where termination of pregnancy is not legal (51). These non-spontaneous terminations of pregnancy, the majority of which occur in low- and middle-income countries, contribute to an estimated 70 000 maternal deaths and lead to serious complications that require medical treatment in a further 8 million women per year (52). About half of all maternal deaths each year occur in young African women (53). Maternal deaths in sub-Saharan Africa are being exacerbated by the HIV epidemic, making the strengthening of HIV services for pregnant women an urgent priority (54, 55).

Prevention of HIV, STIs and pregnancy

HIV prevention options for women

Despite the greater vulnerability of women, the options available for reducing their risk of acquiring HIV infection are limited.

Since the beginning of the epidemic the most widely advocated HIV prevention methods have been the “ABCCC” campaigns promoting Abstinence, Be faithful, Condomize, Counseling and testing and later, Circumcision. However, because of gender power imbalances, women are often unable to successfully negotiate condom use with their male partners, insist on mutual monogamy, or convince their partners to have an HIV test (27, 33, 36, 56). Furthermore, medical male circumcision primarily benefits the male partner and does not seem to directly reduce the HIV-acquisition risk in women(57).

Since 2010, however, there have been a series of trials demonstrating the efficacy of antiretrovirals, as treatment (58) or oral/topical prophylaxis (17, 59-61), in reducing the risk of sexually transmitted HIV infections. These new findings have reinvigorated the HIV prevention field and the challenge now is to translate the clinical trial evidence into practice and public health impact.

Treatment as prevention has been shown to reduce HIV transmission in discordant couples by 96% (58), to control her own HIV risk. In order for a woman to benefit from this prevention strategy she would need to rely on her HIV positive discordant male partner to know his HIV status, to agree to be initiated on take ART even if he does not have AIDS and to adhere to lifelong ART treatment so that she can benefit by being protected from acquiring HIV infection. Given the reluctance of male partners to use already available prevention interventions, it is unlikely that he will agree to early treatment initiation to benefit his partner.

In contrast, oral and topical antiretrovirals, used as pre-exposure prophylaxis, enable women to directly control their own risk of acquiring HIV. Results from the Partners PrEP (60) and Botswana TDF2(61) studies have demonstrated that that oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is effective in preventing HIV in women. However, two additional studies, the VOICE trial (62) and the FemPrEP (63), showed no protective effect, primarily due to low levels of adherence in those trials. These findings suggest that oral prophylaxis is effective when used but may not be suitable in all populations and regions. Despite the potential impact of PrEP, thusfar only daily use of oral only the US FDA has officially approved Truvada has been approved as an HIV prevention option by the US FDA and guidelines have been developed for its use by the US Centers for Dsease Control (64, 65). Since Truvada has not been approved by medicines regulators in any other countries, country-specific individual patient guidelines and programmatic public health guidelines on the implementation of PrEP have not been developed.

Given that women bear a disproportionate burden of HIV, prevention options that they can use and control remains an important goal. The use of microbicides is one of the most promising female-controlled HIV prevention option in development. The candidate product in the most advances stages of testing is tenofovir gel, which was shown in the CAPRISA 004 trial to reduce the risk of HIV by 39% and HSV-2 by 51% in women (17) making it a MPT. It was widely anticipated that the VOICE (Vaginal and Oral Interventions to Control the Epidemic) trial, which was examining the safety and effectiveness of 1% tenofovir gel and two oral antiretroviral agents (tenofovir (TDF) and truvada [a combination of TDF and emtricitabine (FTC)] taken daily to reduce the risk of HIV acquisition in women, would confirm these results. Unfortunately, when the results were announced in 2013 they showed that none of the interventions provided protection against HIV. The lack of protective effect observed in the VOICE trial (62) is largely a consequence of suboptimal adherence; where only 23% of women assigned to the tenofovir gel arm had had detectable drug levels(62). Another phase 3 trial, FACTS 001 (66), is currently underway to confirm the findings from thr CAPRISA 004 trial. If successful, the FACTS 001 trial could provide the data needed for regulatory approval of tenofovir gel and pave the way for the introduction of the first microbicide.

Contraception

In contrast to limited prevention options for HIV, a multitude of safe and effective options are already available to prevent unwanted pregnancies. Despite the wide range of available products, many unplanned pregnancies continue to occur each year. Many of the undesired pregnancies could be avoided if the unmet need for contraception, estimated to be 25% in sub-Saharan Africa, was met (67). However, the inability to access contraception is not the only reason for high rates of unintended pregnancies. Even in the high-income countries like the US, where access to contraceptives is good, almost half of all pregnancies are unintended at the time of conception (68). Many individuals and couples simply struggle with consistent, correct and effective use of contraception.

Experience has shown that many men and women have a negative attitude towards condoms, which represents a significant barrier to their effective use. In the context of HIV prevention, risk perception also impacts on willingness to use condoms; individuals who do not perceived themselves to be at risk appear less likely to wear condoms (69-71). Furthermore, in relationships where effective forms of contraception like the oral pill or injectable is being used, the use of condoms will be less likely. Likewise, in relationships where pregnancy is desired, or where subordination of women limits their ability to negotiate safer sex practices, condom use will be low (72). Female condoms also face additional challenges of higher cost, lower availability and low acceptability, although new products being developed and marketed strive to ameliorate some of these challenges.

Multipurpose prevention technologies

Although STIs and unintended pregnancies are distinct sexual and reproductive health problems, they are inextricably linked. Women who are at risk for unintended pregnancies are also those who are at risk of acquiring STIs, and vice-versa. Given the high rates of both STIs and unwanted pregnancies and the strong association between HIV and maternal mortality in Africa, the development of technologies that can simultaneously address these sexual and reproductive health needs would be extremely beneficial.

Multipurpose prevention technologies (MPTs), often referred to as “combination” or “dual” technologies, are innovative products currently under development that are configured for at least two sexual and reproductive health (SRH) prevention indications. The products are intended to simultaneously prevent unintended pregnancy, and STIs, including HIV, and / or reproductive tract infections (RTIs) (73). MPTs in development include combinations of devices and drugs, combinations of drugs or vaccines, and other novel approaches (74). Barrier devices like male and female condoms and diaphragms are already available and address multiple SRH needs. A multitude of new MPT candidates are also in development and focus on the development or improvement of physical barriers, chemical barriers, and physical / chemical barrier combinations. By targeting multiple SRH needs simultaneously, MPTs potentially offer a cost effective approach to addressing an important public health need, which could result in social and economic benefits to women and their families worldwide. MPTs also include programmatic combination of existing technologies that individually meet multiple SRH needs as part of an integrated service.

Conclusion

Young women in the reproductive age group in sub-Saharan Africa bear a disproportionate burden of HIV infection, unwanted pregnancies and STIs, which are reversing gains made in Millennium Development goals 4, 5 and 6. Keeping young women in this region uninfected with HIV and free of STIs and unwanted pregnancies have enormous individual and population-level health and development benefits. Yet, investment in technologies and programmes to address their needs remain limited. There is an urgent need for technologies including multi-purpose technologies to meet the sexual reproductive health needs of women in sub-Saharan Africa. In addition to the individual benefits of preventing HIV and or pregnancy or STIs, the enhancement of HIV acquisition in the presence of STIs makes prevention of both STIs and HIV particularly important for the synergistic benefits of MPTs. However, as with the development of the individual technologies, the development of MPTs remain challenging

Acknowledgments

Funding: All authors are supported by CAPRISA, which was created with funding from the US National Institutes for Health's (NIH) Comprehensive International Program of Research on AIDS (CIPRA grant # AI51794).

Footnotes

Disclosure of Interests: None

References

- 1.Serwadda D, Mugerwa RD, Sewankambo NK, Lwegaba A, Carswell JW, Kirya GB, et al. Slim disease: a new disease in Uganda and its association with HTLV-III infection. Lancet. 1985;2(8460):849–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(85)90122-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tebit DM, Arts EJ. Tracking a century of global expansion and evolution of HIV to drive understanding and to combat disease. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11(1):45–56. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70186-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.UNAIDS. Global report: UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic 2012. Geneva, Switzerland: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.UNAIDS. Geneva, Switzerland: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; [Accessed: 25 September 2013]. 2013. Global report: UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic 2013. Available from: http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/epidemiology/2013/gr2013/UNAIDS_Global_Report_2013_en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.UNAIDS. Geneva, Switzerland: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS); [accessed 14 February 2014s]. 2012. Together we will end AIDS. Available from: http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/campaigns/togetherwewillendaids/ [Google Scholar]

- 6.UNAIDS. Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; [Accessed 11 February 2014]. 2010. UNAIDS Report on the global AIDS Epidemic 2010. Available from: http://www.unaids.org/globalreport/ [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abdool Karim S, Abdool Karim Q. The evolving HIV epidemic in South Africa. Int J of Epidemiology. 2002;31:37–40. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Department of Health. National HIV and Syphilis sero-prevalence survey of women attending public antenatal clinics in South Africa. Pretoria: Department of Health; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kharsany AB, Mlotshwa M, Frohlich JA, Yende Zuma N, Samsunder N, Abdool Karim SS, et al. HIV prevalence among high school learners - opportunities for schools-based HIV testing programmes and sexual reproductive health services. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:231. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramjee G, Kapiga S, Weiss S, Peterson L, Leburg C, Kelly C, et al. The value of site preparedness studies for future implementation of phase 2/IIb/III HIV prevention trials: experience from the HPTN 055 study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;47(1):93–100. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31815c71f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nel A, Louw C, Hellstrom E, Braunstein SL, Treadwell I, Marais M, et al. HIV prevalence and incidence among sexually active females in two districts of South Africa to determine microbicide trial feasibility. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(8):e21528. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nel A, Mabude Z, Smit J, Kotze P, Arbuckle D, Wu J, et al. HIV incidence remains high in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: evidence from three districts. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(4):e35278. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feldblum PJ, Latka MH, Lombaard J, Chetty C, Chen PL, Sexton C, et al. HIV incidence and prevalence among cohorts of women with higher risk behaviour in Bloemfontein and Rustenburg, South Africa: a prospective study. BMJ Open. 2012;2(1):e000626. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramjee G, Wand H, Whitaker C, McCormack S, Padian N, Kelly C, et al. HIV incidence among non-pregnant women living in selected rural, semi-rural and urban areas in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2012 Oct;16(7):2062–71. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0043-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abdool Karim Q, Kharsany AB, Frohlich JA, Werner L, Mashego M, Mlotshwa M, et al. Stabilizing HIV prevalence masks high HIV incidence rates amongst rural and urban women in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40(4):922–30. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abdool Karim Q, Kharsany AB, Frohlich JA, Werner L, Mlotshwa M, Madlala BT, et al. HIV incidence in young girls in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa--public health imperative for their inclusion in HIV biomedical intervention trials. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(7):1870–6. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0209-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abdool Karim Q, Abdool Karim SS, Frohlich JA, Grobler AC, Baxter C, Mansoor LE, et al. Effectiveness and Safety of Tenofovir Gel, an Antiretroviral Microbicide, for the Prevention of HIV Infection in Women. Science. 2010;329:1168–74. doi: 10.1126/science.1193748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abdool Karim Q, Abdool Karim SS, Singh B, Short R, Ngxongo S. Seroprevalence of HIV infection in rural South Africa. AIDS. 1992;6:1535–9. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199212000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shisana O, Rehle T, Simbayi LC, Zuma K, Jooste S, Pillay-van-Wyk V, et al. South African National HIV Prevalence, Incidence, Behaviour and Communication Survey 2008: A turning tide among teenagers? Cape Town: HSRC Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention. HIV Transmission Risk. [Accessed: 20 September 2013];2013 Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/policies/law/risk.html.

- 21.Roberts L, Passmore JA, Williamson C, Little F, Naranbhai V, Sibeko S, et al. Genital Tract Inflammation in Women Participating in the CAPRISA Tenofovir Microbicide Trial Who Became Infected with HIV: A Mechanism for Breakthrough Infection?; Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; Boston. 2011. Abstract# 991. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Padian NS, Shiboski SC, Glass SO, Vittinghoff E. Heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in northern California: results from a ten-year study. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;146(4):350–7. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gray RH, Wawer MJ, Brookmeyer R, Sewankambo NK, Serwadda D, Wabwire-Mangen F, et al. Probability of HIV-1 transmission per coital act in monogamous, heterosexual, HIV-1-discordant couples in Rakai, Uganda. Lancet. 2001;357(9263):1149–53. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04331-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hayes RJ, Schulz KF, Plummer FA. The cofactor effect of genital ulcers on the per-exposure risk of HIV transmission in sub-Saharan Africa. The Journal of tropical medicine and hygiene. 1995;98(1):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siegfried N, Muller M, Deeks JJ, Volmink J. Male circumcision for prevention of heterosexual acquisition of HIV in men. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(2):CD003362. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003362.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wawer MJ, Gray RH, Sewankambo NK, Serwadda D, Li X, Laeyendecker O, et al. Rates of HIV-1 transmission per coital act, by stage of HIV-1 infection, in Rakai, Uganda. J Infect Dis. 2005;191(9):1403–9. doi: 10.1086/429411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.UNAIDS. Geneva, Switzerland: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS); [Accessed: 18 September 2013]. 2010. Fact sheet - Women, girls, gender equality and HIV. Available from: http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/factsheet/2012/20120217_FS_WomenGirls_en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abdool Karim Q. Barriers to preventing human immunodeficiency virus in women: experiences from KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Journal of the American Medical Women's Association. 2001 Fall;56(4):193–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gregson S, Nyamukapa CA, Garnett GP, Mason PR, Zhuwau T, Carael M, et al. Sexual mixing patterns and sex-differentials in teenage exposure to HIV infection in rural Zimbabwe. Lancet. 2002;359(9321):1896–903. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08780-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kelly RJ, Gray RH, Sewankambo NK, Serwadda D, Wabwire-Mangen F, Lutalo T, et al. Age differences in sexual partners and risk of HIV-1 infection in rural Uganda. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;32(4):446–51. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200304010-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.MacPhail C, Williams BG, Campbell C. Relative risk of HIV infection among young men and women in a South African township. International journal of STD & AIDS. 2002;13(5):331–42. doi: 10.1258/0956462021925162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pettifor AE, Rees HV, Kleinschmidt I, Steffenson AE, MacPhail C, Hlongwa-Madikizela L, et al. Young people's sexual health in South Africa: HIV prevalence and sexual behaviors from a nationally representative household survey. AIDS. 2005;19(14):1525–34. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000183129.16830.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pettifor A, O'Brien K, Macphail C, Miller WC, Rees H. Early coital debut and associated HIV risk factors among young women and men in South Africa. International perspectives on sexual and reproductive health. 2009;35(2):82–90. doi: 10.1363/ifpp.35.082.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wand H, Ramjee G. The relationship between age of coital debut and HIV seroprevalence among women in Durban, South Africa: a cohort study. BMJ Open. 2012;2(1) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Duncan ME, Peutherer JF, Simmonds P, Young H, Tibaux G, Pelzer A, et al. First coitus before menarche and risk of sexually transmitted disease. Lancet. 1990;335(8685):338–40. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90617-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jewkes RK, Dunkle K, Nduna M, Shai N. Intimate partner violence, relationship power inequity, and incidence of HIV infection in young women in South Africa: a cohort study. Lancet. 2010;376(9734):41–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60548-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pruss-Ustun A, Wolf J, Driscoll T, Degenhardt L, Neira M, Calleja JM. HIV due to female sex work: regional and global estimates. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(5):e63476. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.WHO. Prevalence and incidence of selected sexually transmitted infections, Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, syphilis and Trichomonas vaginalis: methods and results used by WHO to generate 2005 estimates. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organisation; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rottingen JA, Cameron DW, Garnett GP. A systematic review of the epidemiologic interactions between classic sexually transmitted diseases and HIV: how much really is known? Sex Transm Dis. 2001;28(10):579–97. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200110000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wald A, Link K. Risk of human immunodeficiency virus infection in herpes simplex virus type 2-seropositive persons: a meta-analysis. J Infect Dis. 2002;185(1):45–52. doi: 10.1086/338231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wasserheit JN. Epidemiological synergy. Interrelationships between human immunodeficiency virus infection and other sexually transmitted diseases. Sex Transm Dis. 1992;19(2):61–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van de Perre P, Segondy M, Foulongne V, Ouedraogo A, Konate I, Huraux JM, et al. Herpes simplex virus and HIV-1: deciphering viral synergy. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8(8):490–7. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70181-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Glynn JR, Biraro S, Weiss HA. Herpes simplex virus type 2: a key role in HIV incidence. AIDS. 2009;23(12):1595–8. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832e15e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Looker KJ, Garnett GP, Schmid GP. An estimate of the global prevalence and incidence of herpes simplex virus type 2 infection. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2008;86(10):805–12. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.046128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith JS, Robinson NJ. Age-specific prevalence of infection with herpes simplex virus types 2 and 1: a global review. J Infect Dis. 2002;186(Suppl 1):S3–28. doi: 10.1086/343739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.World Health Organisation. Global strategy for the prevention and control of sexually transmitted infections: 2006–2015. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organisation; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith-McCune KK, Shiboski S, Chirenje MZ, Magure T, Tuveson J, Ma Y, et al. Type-specific cervico-vaginal human papillomavirus infection increases risk of HIV acquisition independent of other sexually transmitted infections. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(4):e10094. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Houlihan CF, Larke NL, Watson-Jones D, Smith-McCune KK, Shiboski S, Gravitt PE, et al. Human papillomavirus infection and increased risk of HIV acquisition. A systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS. 2012;26(17):2211–22. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328358d908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schiffman M, Castle PE, Jeronimo J, Rodriguez AC, Wacholder S. Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. Lancet. 2007;370(9590):890–907. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61416-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grosskurth H, Mosha F, Todd J, Mwijarubi E, Klokke A, Senkoro K, et al. Impact of improved treatment of sexually transmitted diseases on HIV infection in rural Tanzania: randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 1995;346(8974):530–6. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91380-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Singh S, Sedgh G, Hussain R. Unintended pregnancy: worldwide levels, trends, and outcomes. Studies in family planning. 2010;41(4):241–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2010.00250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Singh S, Wulf R, Hussain R, Bankole A, Sedgh G. Abortion Worldwide: A Decade of Uneven Progress. New York: The Guttmacher Institute; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hill K, Thomas K, AbouZahr C, Walker N, Say L, Inoue M, et al. Estimates of maternal mortality worldwide between 1990 and 2005: an assessment of available data. Lancet. 2007;370(9595):1311–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61572-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moodley J, Pattinson RC, Baxter C, Sibeko S, Abdool Karim Q. Strengthening HIV services for pregnant women: an opportunity to reduce maternal mortality rates in Southern Africa/sub-Saharan Africa. Br J Obstet Gynae. 2011;118(2):219–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Abdool Karim Q, Abouzahr C, Dehne K, Mangiaterra V, Moodley J, Rollins N, et al. HIV and maternal mortality: turning the tide. Lancet. 2010;375(9730):1948–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60747-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Boer H, Mashamba MT. Gender power imbalance and differential psychosocial correlates of intended condom use among male and female adolescents from Venda, South Africa. British journal of health psychology. 2007 Feb;12(Pt 1):51–63. doi: 10.1348/135910706X102104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weiss HA, Hankins CA, Dickson K. Male circumcision and risk of HIV infection in women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009 Nov;9(11):669–77. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70235-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(6):493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, McMahan V, Liu AY, Vargas L, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2587–99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, Mugo NR, Campbell JD, Wangisi J, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):399–410. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thigpen MC, Kebaabetswe PM, Paxton LA, Smith DK, Rose CE, Segolodi TM, et al. Antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis for heterosexual HIV transmission in Botswana. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):423–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Microbicide Trials Network. Press release: Daily HIV prevention approaches didn't work for African women in the VOICE Study. 2013 [5 March 2013]; Available from: http://www.mtnstopshiv.org/node/4877.

- 63.Van Damme L, Corneli A, Ahmed K, Agot K, Lombaard J, Kapiga S, et al. Preexposure Prophylaxis for HIV Infection among African Women. N Eng J Med. 2012;367:411–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1202614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim guidance: preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in men who have sex with men. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011 Jan 28;60(3):65–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim Guidance for Clinicians Considering the Use of Preexposure Prophylaxis for the Prevention of HIV Infection in Heterosexually Active Adults. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(31):586–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.CONRAD. FACTS 001: Safety and Effectiveness of Tenofovir Gel in the Prevention of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV-1) Infection in Young Women and the Effects of Tenofovir Gel on the Incidence of Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV-2) Infection. [last accessed 20 September 2013];2011 Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01386294.

- 67.Sedgh G, Hussain R, Bankole A, Singh S. Women with an Unmet Need for Contraception in Developing Countries and Their Reasons for Not Using a Method. New York: The Guttmacher Institute; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Barot S. The Need for a Revitalized National Research Agenda On Sexual and Reproductive Health. Guttmacher Policy Review. 2011;14(1):16–22. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hendriksen ES, Pettifor A, Lee SJ, Coates TJ, Rees HV. Predictors of condom use among young adults in South Africa: the Reproductive Health and HIV Research Unit National Youth Survey. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(7):1241–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.086009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Civic D. College Students' Reasons for Non use of Condoms Within Dating Relationships. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. 2000;26:95–105. doi: 10.1080/009262300278678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lotfi R, Ramezani Tehrani F, Yaghmaei F, Hajizadeh E. Barriers to condom use among women at risk of HIV/AIDS: a qualitative study from Iran. BMC Women's Health. 2012;12:13. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-12-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bedimo AL, Bennett M, Kissinger P, Clark RA. Understanding barriers to condom usage among HIV-infected African American women. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 1998;9(3):48–58. doi: 10.1016/S1055-3290(98)80019-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Indian Council of Medical Research. Multipurpose Prevention Technologies for Reproductive Health. International Symposium on Accelerating Research on Multipurpose Prevention Technologies for Reproductive Health; New Delhi, India. [Accessed 27 August 2013]. 2012. Report available from: http://icmr.cami-health.org/docs/ICMRReport.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Coalition Advancing Multipurpose Technologies. Multipurpose Technologies. [Accessed 27 August 2013];2012 Available from: http://www.cami-health.org/mpts/