Abstract

Dysregulation of neuronal zinc homeostasis plays a major role in many processes related to brain aging and neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer's disease (AD). Yet, despite the critical role of zinc in neuronal function, the cellular mechanisms underpinning its homeostatic control are far from clear. We reported that the cellular prion protein (PrPC) is involved in the uptake of zinc into neurons. This PrPC-mediated zinc influx required the metal-binding octapeptide repeats in PrPC and the presence of the zinc permeable AMPA channel with which PrPC directly interacted. Together with the observation that PrPC is evolutionarily related to the ZIP family of zinc transporters, these studies indicate that PrPC plays a key role in neuronal zinc homeostasis. Therefore, PrPC could contribute to cognitive health and protect against age-related zinc dyshomeostasis but PrPC has also been identified as a receptor for amyloid-β oligomers which accumulate in the brains of those with AD. We propose that the different roles that PrPC has are due to its interaction with different ligands and/or co-receptors in lipid raft-based signaling/transport complexes.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, AMPA receptor, amyloid, cholesterol, prion protein, zinc

Zinc homeostasis and alzheimer's disease

Zinc is a trace element that is essential for life and whose importance to the function of the central nervous system is increasingly being appreciated. Zinc serves as a cofactor for >300 enzymes that regulate a variety of cellular processes and signaling pathways, and is also a key structural component of numerous other proteins (Frederickson et al., 2005; Sensi et al., 2009). In the brain, which has one of the highest zinc contents with respect to other organs, zinc-containing axons are particularly abundant in the hippocampus and cortex (Toth, 2011). Zinc is predominantly, but not exclusively, localized within synaptic vesicles at glutamatergic nerve terminals [sometimes referred to as gluzinergic neurons (Mocchegiani et al., 2005)]. During neuronal activity, zinc is released along with glutamate into the synaptic cleft where it affects the activity of various receptors. In addition, zinc is itself a signaling molecule, and within the neuron it regulates the activity of multiple enzymes and plays a critical role in the formation and stabilization of the postsynaptic density (Beyersmann and Haase, 2001; Grabrucker et al., 2011; Wilson et al., 2012). Both intracellular and extracellular zinc concentrations must be tightly maintained within narrow optimal ranges for the correct functioning of the nervous system. An excess influx of zinc can damage postsynaptic neurons (Plum et al., 2010) and zinc deficiency affects neurogenesis and increases neuronal apoptosis, which can lead to learning and memory deficits (Szewczyk, 2013). Under normal circumstances, zinc homeostasis is maintained by the coordinated actions of a range of different proteins involved in its uptake, efflux, and intracellular storage and trafficking. Zinc enters neurons through members of the ZIP (Zrt/Irt-like Protein; SLC39) family of zinc transporters, as well as through activated voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazoleproprionate (AMPA) receptors, and N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors (Cousins et al., 2006; Sensi et al., 2009). Zinc exporters, members of the zinc transporter (ZnT; SLC30) family transport zinc from the cytosol to the lumen of intracellular organelles or out of the cell (Sensi et al., 2009).

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the most prevalent form of dementia, affecting millions of individuals world-wide. With currently no cure, the economic and social costs associated with the disease are set to increase dramatically with our aging population. AD is characterized by the deposition in the brain of extracellular plaques of amyloid-β (Aβ) peptide and intracellular inclusions of tau protein. Aβ is proteolytically cleaved from the larger amyloid precursor protein (APP), and both Aβ and APP have binding sites for zinc (Watt et al., 2010; Wong et al., 2014). Zinc, particularly that released from glutamatergic nerve terminals, has a crucial role to play in the aggregation of Aβ into neurotoxic oligomers and fibrils (Bush et al., 1994; Esler et al., 1996; Deshpande et al., 2009), and is also co-localized with Aβ in amyloid plaques (Dong et al., 2003). The activity of the zinc transporter ZnT-3 is required for the transport of zinc into the glutamate-containing presynaptic vesicles. Key evidence for a link between zinc and amyloid pathology in AD comes from the crossing of ZnT-3 knockout mice with Tg2576 mice, a commonly used transgenic mouse model of AD. The crossed mice had minimal synaptic zinc and as a consequence both brain plaque load and amyloid angiopathy were significantly reduced (Lee et al., 2002; Friedlich et al., 2004). Furthermore, in a separate study of aged ZnT-3 knockout mice, there were marked differences in learning and memory observed compared to wild type mice, supporting a requirement for zinc in memory function and the maintenance of synaptic health upon aging (Adlard et al., 2010).

PrPC and neuronal zinc uptake

Recently we reported that PrPC facilitates the uptake of zinc into neuronal cells (Watt et al., 2012). PrPC is infamous because of its conformational conversion into PrPSc being responsible for the fatal transmissible spongiform encephalopathies, such as Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. PrPC is a glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored protein located on the surface of neurons, at both pre- and post-synaptic sites. It is found throughout the central nervous system and is particularly abundant in the hippocampus and frontal cortex (Sales et al., 1998). Using two zinc specific fluorescent dyes (Newport green and Zinpyr-1) we showed that PrPC enhanced the uptake of zinc into human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells and rat primary hippocampal neurons (Watt et al., 2012). This PrPC-mediated zinc influx required the metal-binding octapeptide repeat region in PrPC but not its endocytosis. We then used selective channel antagonists to identify that AMPA receptors were involved in the PrPC-mediated zinc uptake, and that PrPC interacted with both GluA1 and GluA2 AMPA receptor subunits as shown by co-immunoprecipitation. Intracellular protein tyrosine phosphatase activity, which is potently inhibited by zinc (Brautigan et al., 1981; Wilson et al., 2012), was increased in the brains of PrPC null mice, providing evidence of a physiological consequence of altered zinc uptake in the absence of PrPC. These observations provided the first mechanistic explanation for the reduced zinc in the hippocampus and other brain regions of PrPC null mice (Pushie et al., 2011) and indicate that PrPC is a key player in neuronal zinc uptake.

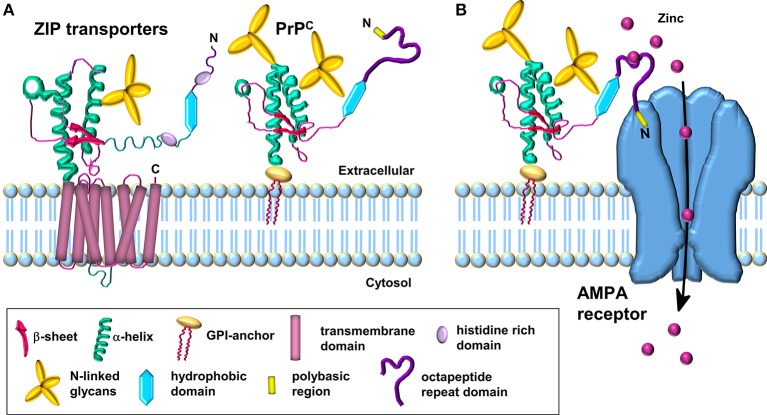

Interestingly, during the course of our work showing that PrPC mediates neuronal zinc uptake, the protein was reported to be evolutionarily related to a subset of the ZIP family of zinc transporters (Schmitt-Ulms et al., 2009). Bioinformatic analysis revealed that the N-terminal extracellular domain of a distinct sub-branch of the LIV-1 subfamily of ZIPs that includes ZIPs 5, 6, and 10 had sequence similarity to the C-terminal globular domain of PrPC. These three ZIPs are also equipped with histidine-rich sequences N-terminal to their “prion-like” domain, capable of divalent metal binding, which is reminiscent of the octapeptide repeat domain of PrPC (Figure 1A). Interestingly, the orientation and distance of the “prion-like” domain to the respective membrane attachment sites in both PrPC and the ZIPs are similar (Figure 1A), and the primary sequence of the first transmembrane domain in the ZIPs and the GPI anchor attachment sequence of PrPC are also comparable, providing further evidence that PrPC is evolutionarily related to members of the ZIP family (Schmitt-Ulms et al., 2009).

Figure 1.

Schematic comparison of ZIP transporters and the PrPC-AMPA receptor zinc transporter. (A) Model of the LIV-1 subfamily of ZIPs with a prion-like ectodomain which is coupled to the C-terminal transmembrane domain. PrPC is structurally similar to the ectodomain of the ZIP transporter. (B) PrPC acts as a sensor for zinc in the extracellular space and coordinates the low affinity binding of zinc to the octapeptide repeats. The N-terminal polybasic region of PrPC interacts with the AMPA receptor subunits; this interaction facilitates the transport of zinc through the AMPA receptor which forms a channel across the membrane for the uptake of zinc in a manner similar to the C-terminal region of the ZIP transporter. Modified from Watt et al. (2013).

As PrPC is a GPI-anchored protein residing in the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane, in order to correlate a function for PrPC in the transport of zinc across the lipid bilayer, we proposed that PrPC requires the assistance of the channel properties of another protein(s), such as AMPA receptors, in order to achieve zinc transport (Figure 1B) (Watt et al., 2012). The octapeptide repeats in the GPI-anchored PrPC act as a zinc sensor/scavenger in the extracellular environment which then presents the metal to the transmembrane channel for uptake of the zinc into the cell (Watt et al., 2013). Interestingly, not all ZIP family members have an extracellular N-terminal extension that may function in zinc sensing: for example ZIPs 1, 2, 3, 9, and 11 have minimal N-terminal extensions on the first transmembrane domain. This raises the intriguing possibility that the two properties (zinc sensing and zinc channel) present together in certain ZIPs (e.g., ZIPs 6 and 10) reside in separate proteins in those ZIPs with minimal N-terminal extensions. It will be interesting to see if PrPC acts as the zinc sensor in combination with certain ZIPs, similar to the situation we have proposed for PrPC and the AMPA receptor (Figure 1B) (Watt et al., 2012, 2013). Such PrPC-based zinc sensing modules may be restricted to higher eukaryotes in which PrPC with the octapeptide metal binding repeats is present.

In addition to its role in zinc metabolism, PrPC also plays a role in the homeostasis of other metals such as iron and copper (Kozlowski et al., 2010; Singh et al., 2014). PrPC expression alters regional zinc, copper and iron content in the mouse brain (Pushie et al., 2011) and there appears to be crosstalk between the different metals, with zinc modulating copper coordination to the octapeptide repeats (Stellato et al., 2011). In addition, PrPC modulates NMDA receptor activity in a copper-dependent manner (Stys et al., 2012), suggesting that multiple receptors/channels may be regulated by PrPC in a ligand/metal-dependent manner.

A cell-surface, lipid raft-based complex involved in the regulation of zinc uptake

The GPI-anchored PrPC is localized in cholesterol-rich, detergent-resistant lipid rafts at the cell surface (Taylor et al., 2005) and it has been proposed that PrPC functions as a key scaffolding protein for the dynamic assembly of cell surface signaling modules (Linden et al., 2008). PrPC, along with the microdomain-forming flotillin or caveolin proteins, may lead to the local assembly of membrane protein complexes at sites involved in cellular communication, such as cell-cell contacts, focal adhesions, the T-cell cap and synapses (Solis et al., 2010). Lipid rafts are essential for synapse development, stabilization and maintenance and caveolin-1 organizes and targets synaptic components to rafts (Hering et al., 2003; Willmann et al., 2006; Guirland and Zheng, 2007). Interestingly, when ZIP1 and ZIP3 were stably expressed in HEK293 cells, the punctate cell surface staining observed led the authors to suggest that they were localized to lipid rafts (although no experimental evidence for this was provided) (Wang et al., 2004). Furthermore, treatment of the HEK293 cells with methyl-β-cyclodextrin, which sequesters cholesterol and disrupts cholesterol-rich lipid rafts, resulted in a more diffuse surface staining (Wang et al., 2004), reminiscent of what is observed for PrPC and other GPI-anchored proteins (Parkin et al., 2003; Taylor et al., 2005). We also have disrupted rafts in neuronal cells using methyl-β-cyclodextrin and observed a reduction in zinc uptake, an effect exacerbated when the cells also expressed PrPC (Watt and Hooper, unpublished). In contrast, it has been reported that ZIP10 only partially colocalizes with PrPC in N2a cells and is not detected in detergent-resistant rafts (Ehsani et al., 2012). These data raise the intriguing possibility that a cell-surface, lipid raft-based complex, possibly stabilized by PrPC, regulates the cell surface expression of certain zinc transporters and thus zinc uptake.

PrPC is a cell surface receptor for Aβ oligomers

In 2009, PrPC was identified as a high-affinity receptor for Aβ oligomers, the primary neurotoxic species in AD (Lauren et al., 2009). The presence of PrPC in hippocampal slices was shown to be responsible for the Aβ oligomer-mediated inhibition of long-term potentiation (LTP) (Lauren et al., 2009). PrPC was also required for the manifestation of memory impairments in an AD mouse model (Gimbel et al., 2010), which were reversed by intra-cerebral infusion of an anti-PrPC monoclonal antibody (Chung et al., 2010). Immuno-targeting of PrPC was shown to block completely the LTP impairments caused by Aβ oligomers derived from human AD brain extracts (Barry et al., 2011; Freir et al., 2011). Aβ oligomers bound to PrPC activate the non-receptor tyrosine kinase Fyn (Um et al., 2012; Rushworth et al., 2013) and results in pathological changes in tau (Larson et al., 2012). Although there is general consensus that PrPC can bind oligomeric forms of Aβ, some studies dispute a role for PrPC in mediating Aβ toxicity (Calella et al., 2010; Kessels et al., 2010).

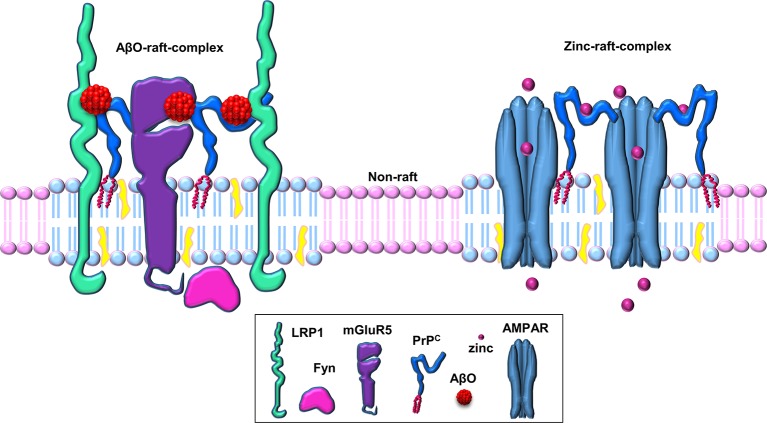

It has been hypothesized that a putative transmembrane co-receptor is required to connect the binding of Aβ to the GPI-anchored PrPC on the outer surface of the plasma membrane with downstream effects inside the cell (Cisse and Mucke, 2009; Lauren et al., 2009). The transmembrane low-density lipoprotein-receptor related protein-1 (LRP1) is highly expressed in neuronal cells (Nykjaer and Willnow, 2002), facilitates the endocytosis of PrPC (Taylor and Hooper, 2007) and has been implicated in the neuronal uptake of Aβ (Fuentealba et al., 2010; Kanekiyo et al., 2011). We hypothesized, therefore, that LRP1 may play a role in the PrPC-mediated action of Aβ oligomers (Figure 2). We showed that LRP1 is required for the binding of Aβ oligomers to cells, as well as for their subsequent internalization and cytotoxicity (Rushworth et al., 2013). In parallel with our work on LRP1, Strittmatter and colleagues identified the metabotropic glutamate receptor, mGluR5, as a co-receptor with PrPC for Aβ oligomers and was required to activate Fyn (Um et al., 2013). Furthermore, antagonists of mGluR5 reversed the deficits in learning, memory and synapse density in AD transgenic mice (Um et al., 2013). In addition, the Aβ-PrPC-mGluR5 interplay is involved in mediating both long-term depression facilitation and LTP inhibition (Hu et al., 2014). Thus, both LRP1 and mGluR5 appear to be transmembrane co-receptors in the Aβ-PrPC interaction, which are required for the PrPC-mediated action of Aβ oligomers. Whether both LRP1 and mGluR5 reside in the same complex with PrPC or in separate signaling complexes is currently unclear.

Figure 2.

Schematic of PrPC-based cell-surface, raft-based complexes involved in zinc uptake and Aβ binding. PrPC acts as a hub for cell surface, lipid raft-based signaling/transport complexes. PrPC associates with various transmembrane proteins (such as AMPA receptors, LRP1, mGluR5, etc.) in these multi-protein complexes in a ligand-dependent manner (here shown for the ligands zinc and Aβ oligomers within separate raft-based complexes).

A cell-surface, lipid raft-based signaling complex involved in Aβ oligomer action

Cell surface cholesterol-rich, detergent-resistant lipid rafts are intimately involved in the production, aggregation and toxicity of Aβ (Rushworth and Hooper, 2010; Di Paolo and Kim, 2011). For example, these membrane microdomains have been linked with Aβ toxicity via Fyn, and rafts are involved in the neuronal internalization of Aβ (Williamson et al., 2008; Lai and McLaurin, 2010). We investigated whether the integrity of lipid rafts is required for the binding of Aβ oligomers and the subsequent activation of Fyn. Treatment of cells with methyl-β-cyclodextrin caused the re-localization of PrPC and Fyn from detergent-resistant rafts to detergent-soluble, non-raft regions of the membrane as analyzed by sucrose density gradient centrifugation in the presence of Triton X-100. Surprisingly, disruption of the rafts with methyl-β-cyclodextrin significantly reduced (by 80.6%) the cell surface binding of the Aβ oligomers, even though the cell surface expression of PrPC was unaffected, and prevented the Aβ oligomers from activating Fyn (Rushworth et al., 2013). Thus, raft localization of PrPC is required for the binding of Aβ oligomers, and the integrity of rafts and/or other raft-localized proteins are required for the Aβ-mediated activation of Fyn. These observations suggest that there is a cell-surface, raft-based signaling complex that is key to the binding of Aβ oligomers and the subsequent generation of cellular responses.

Aβ oligomers caused mGluR5 receptors to manifest reduced lateral diffusion as they became aberrantly clustered (Renner et al., 2010). Antibodies against PrPC and the NR1 subunit of NMDA receptors had a similar inhibitory effect on Aβ oligomer binding as the antibody against mGluR5, but there was not an additive effect of the individual antibodies, suggesting that mGluR5, PrPC, and NR1 may be in proximity to each other as well as the Aβ oligomer binding site (Renner et al., 2010). Interestingly, addition of Aβ oligomers to neurons caused a large increase of mGluR5 in the Triton-resistant fraction (Renner et al., 2010), although no link to its possible redistribution into detergent-resistant lipid rafts was made. In another study, disruption of lipid rafts by cholesterol depletion reduced the interaction of Aβ with α-7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (Khan et al., 2010). These observations are consistent with multiple (co)receptor proteins for Aβ oligomers residing in cell-surface, raft-based complex(es).

PrPC and rafts are dysregulated in aging

Zinc homeostasis plays a major role in many processes related to brain aging. For example, mouse models of accelerated aging, such as senescence-accelerated mouse prone 10 (SAMP10) mice display a low total zinc concentration in synaptic vesicles that is associated with brain atrophy and defects in learning and memory (Saito et al., 2000), and dietary zinc deficiency influences hippocampal learning and memory in an age-dependent manner (Mocchegiani et al., 2005; Szewczyk, 2013). ZIP6 expression has been reported to be decreased in an age-dependent manner (Wong et al., 2013), although nothing has been reported about the expression, subcellular localization or function of any other ZIP in the aged brain. Caveolin-1 has been identified as a novel control point for healthy neuronal aging, with the localization of caveolin-1, PSD95, and AMPA receptors in lipid rafts being decreased in aged (>18 months) mice compared with young (3–6 month) mice (Head et al., 2010). Furthermore, in an aging series (age 20–88 years) of human brains we reported that PrPC was reduced in the hippocampus with increasing age (Whitehouse et al., 2010). Preliminary data indicate that there is a significant reduction of both ZIP1 and ZIP3 in the hippocampus of old (79–88 years) compared with young (20–26 years) individuals (Watt and Hooper, unpublished). These observations suggest that alterations to the structure and function of the cell-surface, raft-based zinc transporter complex may occur in aging and contribute to the age-related dysregulated zinc homeostasis.

Aging is the greatest risk factor for AD and recently the REST protein was reported to have a central role in protecting aging neurons from degeneration (Lu et al., 2014). There is a close relationship between lipid rafts, cholesterol, and the age-associated decline and dysregulation of cellular signaling pathways (Ohno-Iwashita et al., 2010). A key component of a subset of rafts, caveolin-1, was identified as a novel control point for both Aβ-based neurodegeneration and healthy neuronal aging (Head et al., 2010), and caveolin-1 expression is altered in AD (Gaudreault et al., 2004). In addition, the level of PrPC is altered in both the AD and aging brain (Whitehouse et al., 2010, 2013; Larson et al., 2012). Thus, dysregulation of the structure and function of cell-surface, raft-based signaling complexes may occur in, and contribute to, both AD and aging.

Conclusion

PrPC appears to be involved in multiple physiological and pathological processes, including as highlighted here, neuronal zinc uptake and Aβ oligomer binding and toxicity. We propose that PrPC acts as a hub for cell surface, lipid raft-based signaling/transport complexes, and that the different roles that the protein has are due to the selective interaction of PrPC with different ligands (such as zinc or Aβ oligomers) and/or co-receptors (such as AMPA receptors, LRP1, mGluR5) in these multi-protein complexes (Figure 2). It is likely that these complexes are relatively transient in nature, being stabilized upon binding of a particular ligand for a limited time period before dissociation or endocytosis terminates the signaling or transport process. The use of more sophisticated techniques, such as super resolution light microscopy, should enable the molecular details of these different lipid raft-based signaling/transport complexes to be determined and provide a clearer picture of the role of PrPC and lipid rafts in neuronal zinc transport and Aβ action in AD. It will also be interesting to determine how the interplay between PrPC, zinc, and Aβ may underlie aging and age-related diseases.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the financial support of the Medical Research Council of Great Britain (G0802189).

References

- Adlard P. A., Parncutt J. M., Finkelstein D. I., Bush A. I. (2010). Cognitive loss in zinc transporter-3 knock-out mice: a phenocopy for the synaptic and memory deficits of Alzheimer's disease? J. Neurosci. 30, 1631–1636. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5255-09.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry A. E., Klyubin I., McDonald J. M., Mably A. J., Farrell M. A., Scott M., et al. (2011). Alzheimer's disease brain-derived amyloid-β-mediated inhibition of LTP in vivo is prevented by immunotargeting cellular prion protein. J. Neurosci. 31, 7259–7263. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6500-10.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyersmann D., Haase H. (2001). Functions of zinc in signaling, proliferation and differentiation of mammalian cells. Biometals 14, 331–341. 10.1023/A:1012905406548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brautigan D. L., Bornstein P., Gallis B. (1981). Phosphotyrosyl-protein phosphatase. Specific inhibition by Zn. J. Biol. Chem. 256, 6519–6522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush A. I., Pettingell W. H., Multhaup G., d Paradis M., Vonsattel J. P., Gusella J. F., et al. (1994). Rapid induction of Alzheimer Aβ amyloid formation by zinc. Science 265, 1464–1467. 10.1126/science.8073293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calella A. M., Farinelli M., Nuvolone M., Mirante O., Moos R., Falsig J., et al. (2010). Prion protein and Aβ-related synaptic toxicity impairment. EMBO Mol. Med. 2, 306–314. 10.1002/emmm.201000082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung E., Ji Y., Sun Y., Kascsak R. J., Kascsak R. B., Mehta P. D., et al. (2010). Anti-PrPC monoclonal antibody infusion as a novel treatment for cognitive deficits in an Alzheimer's disease model mouse. BMC Neurosci. 11:130. 10.1186/1471-2202-11-130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cisse M., Mucke L. (2009). Alzheimer's disease: a prion protein connection. Nature 457, 1090–1091. 10.1038/4571090a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cousins R. J., Liuzzi J. P., Lichten L. A. (2006). Mammalian zinc transport, trafficking, and signals. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 24085–24089. 10.1074/jbc.R600011200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshpande A., Kawai H., Metherate R., Glabe C. G., Busciglio J. (2009). A role for synaptic zinc in activity-dependent Aβ oligomer formation and accumulation at excitatory synapses. J. Neurosci. 29, 4004–4015. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5980-08.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Paolo G., Kim T.-W. (2011). Linking lipids to Alzheimer's disease: cholesterol and beyond. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 12, 284–296. 10.1038/nrn3012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong J., Atwood C. S., Anderson V. E., Siedlak S. L., Smith M. A., Perry G., et al. (2003). Metal binding and oxidation of amyloid-β within isolated senile plaque cores: Raman microscopic evidence. Biochemistry 42, 2768–2773. 10.1021/bi0272151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehsani S., Salehzadeh A., Huo H., Reginold W., Pocanschi C. L., Ren H., et al. (2012). LIV-1 ZIP ectodomain shedding in prion-infected mice resembles cellular response to transition metal starvation. J. Mol. Biol. 422, 556–574. 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esler W. P., Stimson E. R., Jennings J. M., Ghilardi J. R., Mantyh P. W., Maggio J. E. (1996). Zinc-induced aggregation of human and rat β-amyloid peptides in vitro. J. Neurochem. 66, 723–732. 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.66020723.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederickson C. J., Koh J. Y., Bush A. I. (2005). The neurobiology of zinc in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 6, 449–462. 10.1038/nrn1671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freir D. B., Nicoll A. J., Klyubin I., Panico S., McDonald J. M., Risse E., et al. (2011). Interaction between prion protein and toxic amyloid β assemblies can be therapeutically targeted at multiple sites. Nat. Commun. 2, 336. 10.1038/ncomms1341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedlich A. L., Lee J. Y., van Groen T., Cherny R. A., Volitakis I., Cole T. B., et al. (2004). Neuronal zinc exchange with the blood vessel wall promotes cerebral amyloid angiopathy in an animal model of Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurosci. 24, 3453–3459. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0297-04.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentealba R. A., Liu Q., Zhang J., Kanekiyo T., Hu X., Lee J. M., et al. (2010). Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1) mediates neuronal Aβ 42 uptake and lysosomal trafficking. PLoS ONE 5:e11884. 10.1371/journal.pone.0011884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudreault S. B., Dea D., Poirier J. (2004). Increased caveolin-1 expression in Alzheimer's disease brain. Neurobiol. Aging 25, 753–759. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2003.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimbel D. A., Nygaard H. B., Coffey E. E., Gunther E. C., Lauren J., Gimbel Z. A., et al. (2010). Memory impairment in transgenic Alzheimer mice requires cellular prion protein. J. Neurosci. 30, 6367–6374. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0395-10.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabrucker A. M., Knight M. J., Proepper C., Bockmann J., Joubert M., Rowan M., et al. (2011). Concerted action of zinc and ProSAP/Shank in synaptogenesis and synapse maturation. EMBO J. 30, 569–581. 10.1038/emboj.2010.336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guirland C., Zheng J. Q. (2007). Membrane lipid rafts and their role in axon guidance. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 621, 144–155. 10.1007/978-0-387-76715-4_11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Head B. P., Peart J. N., Panneerselvam M., Yokoyama T., Pearn M. L., Niesman I. R., et al. (2010). Loss of caveolin-1 accelerates neurodegeneration and aging. PloS ONE 5:e15697. 10.1371/journal.pone.0015697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hering H., Lin C. C., Sheng M. (2003). Lipid rafts in the maintenance of synapses, dendritic spines, and surface AMPA receptor stability. J. Neurosci. 23, 3262–3271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu N.-W., Nicoll A. J., Zhang D., Mably A. J., O'Malley T., Purro S. A., et al. (2014). mGlu5 receptors and cellular prion protein mediate amyloid-β-facilitated synaptic long-term depression in vivo. Nat. Commun. 5:3374. 10.1038/ncomms4374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanekiyo T., Zhang J., Liu Q., Liu C.-C., Zhang L., Bu G. (2011). Heparan sulphate proteoglycan and the low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 constitute major pathways for neuronal amyloid-β uptake. J. Neurosci. 31, 1644–1651. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5491-10.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessels H. W., Nguyen L. N., Nabavi S., Malinow R. (2010). The prion protein as a receptor for amyloid-β. Nature 466, E3–E4; discussion: E4–E5. 10.1038/nature09217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan G. M., Tong M., Jhun M., Arora K., Nichols R. A. (2010). β-Amyloid activates presynaptic α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors reconstituted into a model nerve cell system: involvement of lipid rafts. Eur. J. Neurosci. 31, 788–796. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07116.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowski H., Luczkowski M., Remelli M. (2010). Prion proteins and copper ions. Biological and chemical controversies. Dalton Trans. 39, 6371–6385. 10.1039/c001267j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai A. Y., McLaurin J. (2010). Mechanisms of amyloid-β peptide uptake by neurons: the role of lipid rafts and lipid raft-associated proteins. Int. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2011:548380. 10.4061/2011/548380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson M., Sherman M. A., Amar F., Nuvolone M., Schneider J. A., Bennett D. A., et al. (2012). The complex PrPc-Fyn couples human oligomeric Aβ with pathological Tau changes in Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurosci. 32, 16857–16871. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1858-12.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauren J., Gimbel D. A., Nygaard H. B., Gilbert J. W., Strittmatter S. M. (2009). Cellular prion protein mediates impairment of synaptic plasticity by amyloid-β oligomers. Nature 457, 1128–1132. 10.1038/nature07761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. Y., Cole T. B., Palmiter R. D., Suh S. W., Koh J. Y. (2002). Contribution by synaptic zinc to the gender-disparate plaque formation in human Swedish mutant APP transgenic mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 7705–7710. 10.1073/pnas.092034699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden R., Martins V. R., Prado M. A., Cammarota M., Izquierdo I., Brentani R. R. (2008). Physiology of the prion protein. Physiol. Rev. 88, 673–728. 10.1152/physrev.00007.2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu T., Aron L., Zullo J., Pan Y., Kim H., Chen Y., et al. (2014). REST and stress resistance in ageing and Alzheimer's disease. Nature 507, 448–454. 10.1038/nature13163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mocchegiani E., Bertoni-Freddari C., Marcellini F., Malavolta M. (2005). Brain, aging and neurodegeneration: role of zinc ion availability. Prog. Neurobiol. 75, 367–390. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nykjaer A., Willnow T. E. (2002). The low-density lipoprotein receptor gene family: a cellular Swiss army knife? Trends Cell Biol. 12, 273–280. 10.1016/S0962-8924(02)02282-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno-Iwashita Y., Shimada Y., Hayashi M., Inomata M. (2010). Plasma membrane microdomains in aging and disease. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 10 Suppl. 1, S41–S52. 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2010.00600.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkin E. T., Tan F., Skidgel R. A., Turner A. J., Hooper N. M. (2003). The ectodomain shedding of angiotensin-converting enzyme is independent of its localisation in lipid rafts. J. Cell Sci. 116, 3079–3087. 10.1242/jcs.00626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plum L. M., Rink L., Haase H. (2010). The essential toxin: impact of zinc on human health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public health 7, 1342–1365. 10.3390/ijerph7041342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pushie M. J., Pickering I. J., Martin G. R., Tsutsui S., Jirik F. R., George G. N. (2011). Prion protein expression level alters regional copper, iron and zinc content in the mouse brain. Metallomics 3, 206–214. 10.1039/c0mt00037j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renner M., Lacor P. N., Velasco P. T., Xu J., Contractor A., Klein W. L., et al. (2010). Deleterious effects of amyloid beta oligomers acting as an extracellular scaffold for mGluR5. Neuron 66, 739–754. 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.04.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushworth J. V., Griffiths H. H., Watt N. T., Hooper N. M. (2013). Prion protein-mediated toxicity of amyloid-β oligomers requires lipid rafts and the transmembrane LRP1. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 8935–8951. 10.1074/jbc.M112.400358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushworth J. V., Hooper N. M. (2010). Lipid rafts: linking Alzheimer's amyloid-β production, aggregation, and toxicity at neuronal membranes. Int. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2011, 603052. 10.4061/2011/603052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito T., Takahashi K., Nakagawa N., Hosokawa T., Kurasaki M., Yamanoshita O., et al. (2000). Deficiencies of hippocampal Zn and ZnT3 accelerate brain aging of Rat. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 279, 505–511. 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sales N., Rodolfo K., Hassig R., Faucheux B., Di Giamberardino L., Moya K. L. (1998). Cellular prion protein localization in rodent and primate brain. Eur. J. Neurosci. 10, 2464–2471. 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00258.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt-Ulms G., Ehsani S., Watts J. C., Westaway D., Wille H. (2009). Evolutionary descent of prion genes from the ZIP family of metal ion transporters. PLoS ONE 4:e7208. 10.1371/journal.pone.0007208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sensi S. L., Paoletti P., Bush A. I., Sekler I. (2009). Zinc in the physiology and pathology of the CNS. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 10, 780–791. 10.1038/nrn2734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh N., Haldar S., Tripathi A. K., McElwee M. K., Horback K., Beserra A. (2014). Iron in neurodegenerative disorders of protein misfolding: a case of prion disorders and Parkinson's disease. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 21, 471–484. 10.1089/ars.2014.5874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solis G. P., Malaga-Trillo E., Plattner H., Stuermer C. A. (2010). Cellular roles of the prion protein in association with reggie/flotillin microdomains. Front. Biosci. 15, 1075–1085. 10.2741/3662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stellato F., Spevacek A., Proux O., Minicozzi V., Millhauser G., Morante S. (2011). Zinc modulates copper coordination mode in prion protein octa-repeat subdomains. Eur. Biophys. J. 40, 1259–1270. 10.1007/s00249-011-0713-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stys P. K., You H., Zamponi G. W. (2012). Copper-dependent regulation of NMDA receptors by cellular prion protein: implications for neurodegenerative disorders. J. Physiol. 590, 1357–1368. 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.225276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szewczyk B. (2013). Zinc homeostasis and neurodegenerative disorders. Front. Aging Neurosci. 5:33. 10.3389/fnagi.2013.00033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor D. R., Hooper N. M. (2007). The low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1) mediates the endocytosis of the cellular prion protein. Biochem. J. 402, 17–23. 10.1042/BJ20061736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor D. R., Watt N. T., Perera W. S., Hooper N. M. (2005). Assigning functions to distinct regions of the N-terminus of the prion protein that are involved in its copper-stimulated, clathrin-dependent endocytosis. J. Cell Sci. 118, 5141–5153. 10.1242/jcs.02627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth K. (2011). Zinc in neurotransmission. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 31, 139–153. 10.1146/annurev-nutr-072610-145218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Um J. W., Kaufman A. C., Kostylev M., Heiss J. K., Stagi M., Takahashi H., et al. (2013). Metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 is a coreceptor for Alzheimer Aβ oligomer bound to cellular prion protein. Neuron 79, 887–902. 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.06.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Um J. W., Nygaard H. B., Heiss J. K., Kostylev M. A., Stagi M., Vortmeyer A., et al. (2012). Alzheimer amyloid-β oligomer bound to postsynaptic prion protein activates Fyn to impair neurons. Nat. Neurosci. 15, 1227–1235. 10.1038/nn.3178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F., Dufner-Beattie J., Kim B. E., Petris M. J., Andrews G., Eide D. J. (2004). Zinc-stimulated endocytosis controls activity of the mouse ZIP1 and ZIP3 zinc uptake transporters. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 24631–24639. 10.1074/jbc.M400680200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt N. T., Griffiths H. H., Hooper N. M. (2013). Neuronal zinc regulation and the prion protein. Prion 7, 203–208. 10.4161/pri.24503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt N. T., Taylor D. R., Kerrigan T. L., Griffiths H. H., Rushworth J. V., Whitehouse I. J., et al. (2012). Prion protein facilitates uptake of zinc into neuronal cells. Nat. Commun. 3, 1134. 10.1038/ncomms2135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt N. T., Whitehouse I. J., Hooper N. M. (2010). The role of zinc in Alzheimer's disease. Int. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2011:971021. 10.4061/2011/971021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehouse I. J., Jackson C. D., Turner A. J., Hooper N. M. (2010). Prion protein is reduced in aging and in sporadic but not in familial Alzheimer's disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 22, 1023–1031. 10.3233/JAD-2010-101071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehouse I. J., Miners J. S., Glennon E. B., Kehoe P. G., Love S., Kellett K. A., et al. (2013). Prion protein is decreased in Alzheimer's brain and inversely correlates with BACE1 activity, amyloid-β levels and Braak stage. PLoS ONE 8:e59554. 10.1371/journal.pone.0059554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson R., Usardi A., Hanger D. P., Anderton B. H. (2008). Membrane-bound β-amyloid oligomers are recruited into lipid rafts by a Fyn-dependent mechanism. FASEB J. 22, 1552–1559. 10.1096/fj.07-9766com [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willmann R., Pun S., Stallmach L., Sadasivam G., Santos A. F., Caroni P., et al. (2006). Cholesterol and lipid microdomains stabilize the postsynapse at the neuromuscular junction. EMBO J. 25, 4050–4060. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson M., Hogstrand C., Maret W. (2012). Picomolar concentrations of free zinc(II) ions regulate receptor protein-tyrosine phosphatase β activity. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 9322–9326. 10.1074/jbc.C111.320796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong B. X., Hung Y. H., Bush A. I., Duce J. A. (2014). Metals and cholesterol: two sides of the same coin in Alzheimer's disease pathology. Front. Aging Neurosci. 6:91. 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong C. P., Magnusson K. R., Ho E. (2013). Increased inflammatory response in aged mice is associated with age-related zinc deficiency and zinc transporter dysregulation. J. Nutr. Biochem. 24, 353–359. 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2012.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]