Abstract

The knockdown of Pim-1 or inhibition of Pim-1 activity significantly increased c-H2A.X expression. The effect was correlated to apoptosis and was attributed to the inhibition of nonhomologous DNA-end-joining (NHEJ) repair activity supported by the following observations: (1) inhibition of ATM and DNA-PKcs activities, (2) down-regulation of Ku expression and nuclear localization and (3) decrease of DNA end-binding of both Ku70 and Ku80. The data suggest that Pim-1 plays a crucial role in the regula-tion of NHEJ repair. In the absence of Pim-1, the ability of DNA repair significantly decreases when exposed to paclitaxel, leading to severe DNA damage and apoptosis.

Keywords: Pim-1, Paclitaxel, H2A.X phosphorylation, NHEJ DNA repair, Prostate cancers

1. Introduction

Pim-1, a serine/threonine kinase, has been implicated in numer-ous biological functions, including cell migration and invasion, cell survival, proliferation and differentiation [1–3]. The crystal struc-ture of Pim-1 reveals that it is a constitutively active kinase [4]. Pim-1 is predominantly present in the cytoplasm and the nucleus, and has been identified to induce cell cycle progression and to inhibit cell death. Several cell cycle regulators have been reported to be phosphorylated by Pim-1, including CDC25A, CDC25C, p27Kip1 and p21Cip1/WAF1 [5–7]. Although Pim-1 is expressed in normal cells, a wide variety of human cancer cell lines have been identified to display a relatively high level of Pim-1 expression, such as lymphoid and myeloid cells, prostate cancer cells, colorectal carcinoma and gastric cancer cells [3,8]. Moreover, expression of Pim-1 is regulated by several growth factors, cytokines and cellular stres-ses, such as hypoxia and cancer chemotherapeutic drugs [3,9–12].

Pim-1 is over expressed in a number of cancer cells and is involved in numerous cellular signaling pathways that regulate cell cycle progression and cell survival. Several studies have analyzed the prognostic impact of the proto-oncogene Pim-1 in certain types of solid tumors. The evidence shows that up-regulation of Pim-1 might be a tumor maker for gastric cancer, prostate cancer and pancreatic cancer [13–15]. Accordingly, Pim-1 has been elucidated to serve as a target for cancer chemotherapeutic intervention. Re-cently, several ATP competitive small-molecule inhibitors of Pim-1 have been developed. Some of these inhibitors are initially known as the inhibitors on blocking other kinases – staurosporine (a broad-spectrum kinase inhibitor), LY333531 (a protein-kinase C inhibitor), LY294002 (a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitor) and quercetagetin (a flavonoid) for example [12,16–18]. Pim-1 inhibitors display effective inhibitory activity of cell growth against several human cancer cell types, including leukemia and several solid tumors [12,19]. The Pim-1-mediated mechanisms leading to its effects on cell survival, cell cycle progression and apoptosis are complicated. Pim-1 can phosphorylate Bad, a BH3-containing Bcl-2 family member protein, leading to this pro-apoptotic protein to be sequestered by 14-3-3 proteins and blocking the apoptotic effect [20]. Besides, the increase of anti-apoptotic proteins, Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL induced by Pim-1 has been suggested to be attributed to the cell survival [20,21]. Recently, Pim-1 has been implicated in the regulation of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) translational pathway through phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 protein [22] and PRAS40 (proline-rich Akt substrate 40 kDa) [23]. Moreover, Pim-1 may also regulate cell cycle progres-sion through modification of p21, p27 and Cdc25A and by phos-phorylating Cdc25C phosphatase [5–7,16].

A wide variety of intracellular survival pathways can be induced in cancer cells to cope with the imposed stresses caused by cancer chemotherapeutic drugs. Over expression of Pim-1 kinase is one of the examples of survival pathways. Pim-1 has been indicated to regulate cell survival after cytokine withdrawal [21,24] and expo-sure to cancer chemotherapeutic agents [25]. Because Pim-1 con-fers drug resistance [3,9,12], the associated induction of Pim-1 in cells when treated with anticancer drugs [9,12] becomes a major obstacle to be solved. Tubulin-binding drugs, such as docetaxel, have been widely used for the treatment of prostate cancers. Since Pim-1 kinase has been implicated in the progression of prostate cancers and to serve as a prognostic marker, the Pim-1-involved mechanism study in prostate cancers exposed to tubulin-binding drugs is particularly important. We present data in this study demonstrating that Pim-1 is highly involved in cellular DNA repair system. Knockdown of Pim-1 in human hormone-refractory prostate cancer cells largely facilitates apoptosis induced by tubulin-bind-ing drug through impairment of DNA repair system. The data may provide insight into anticancer approach targeting Pim-1 and tubulin in an impact in DNA repair mechanism.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

RPMI 1640 medium, fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin, streptomycin, and all other tissue culture reagents were obtained from GIBCO/BRL Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY). The following antibodies were used: anti-mouse and anti-rabbit IgGs, Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, Bax, Bid, Bad, PARP-1, nucleolin, cyclin B1, DNA-PK catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs), phospho-DNA-PKcsThr2609 and replication protein A 32 kDa subunit (RPA32) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA), a-tubulin, Ku70, Ku80, phospho-H2A.XSer139, ATM, phospho-ATMSer1981, Pim-1, phospho-STAT3Ser727 (signal transducer and activator of transcription 3), GAPGH, phospho-BadSer112 and actin (Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA) and MPM-2 (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY). Paclitaxel, vincristine, evodiamine, colchicine, quercetin, propidium iodide (PI), phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride (PMSF), leupeptin, dithiothreitol and rhodamine 123 were obtained from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Pim-1 siRNA was obtained from (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA).

2.2. Cell culture

PC-3 cell line was from American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD). The cells were cultured in RPMI1640 medium with 10% FBS (v/v) and penicillin (100 units/ml)/streptomycin (100 lg/ml). Cultures were maintained in a humidi-fied incubator at 37 LC in 5% CO2/95% air.

2.3. Flow cytometry cell cycle analysis

After the treatment, the cells were harvested by trypsinization, fixed with 70% (v/v) alcohol at 4 LC for 30 min and washed with PBS. After centrifugation, cells were incubated in phosphate–citric acid buffer (0.2 M NaHPO4, 0.1 M citric acid, pH 7.8) for 30 min at room temperature. The cells were centrifuged and resus-pended with 0.5 ml PI solution containing Triton X-100 (0.1% v/v), RNase (100 lg/ ml) and PI (80 lg/ml). DNA content was analyzed with the FACScan and CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA).

2.4. DNA fragmentation assay

The DNA fragmentation was determined using the Cell Death Detection ELISA-plus kit (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). The assay was based on the quantitative in vitro determination of cytoplasmic histone-associated DNA fragments (mono-and oligonucleosomes) after induced cell death. After the treatment with the indi-cated agents, the cells were lysed and centrifuged, and the supernatant was used for the detection of nucleosomal DNA according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

2.5. Western blotting

After the treatment, the cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS and reaction was terminated by the addition of 100 ll ice-cold lysis buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM PMSF, 10 lg/ml aprotinin, 10 lg/ml leupep-tin, and 1% Triton X-100). The amount of proteins (40 lg) were separated by elec-trophoresis in a 10% or 15% polyacrylamide gel and transferred to a PVDF membrane. After an overnight incubation at 4 LC in PBS/5% nonfat milk, the mem-brane was washed with PBS/0.1% Tween 20 for 1 h and immuno-reacted with the indicated antibody for 2 h at room temperature. After four washings with PBS/ 0.1% Tween 20, the anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG (dilute 1:2000) was applied to the membranes for 1 h at room temperature. The membranes were washed with PBS/0.1% Tween 20 for 1 h and the detection of signal was performed with an enhanced chemiluminescence detection kit (Amersham Biosciences). The data were quantified using the computerized image analysis system ImageQuant (Amersham Biosciences).

2.6. Nuclear extraction

Nuclear extracts were prepared by sequential cell lysis and nuclear lysis. Cells were suspended in 30 ll buffer containing 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.9), 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol and 0.2 mM PMSF. The cells were subjected to vigorous vortex for 20 s, ice-cold treatment for 10 min, and centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 2 min. The pelleted nuclei were resuspended in buffer containing 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.9), 25% glycerol, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 420 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol and 0.2 mM PMSF. After 20 min on ice, the lysates were cen-trifuged at 15,000 rpm for 2 min. The supernatants containing the solubilized nu-clear proteins were used for Western blotting.

2.7. Immunofluorescence examination

After the treatment, the cells were fixed with 100% methanol at _20 LC for 5 min and incubated in 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) containing 0.1% Triton X-100 at 37 LC for 30 min. The cells were washed twice with PBS for 5 min and incu-bated with primary antibodies at 37 LC for 1 h. The cells were washed twice with PBS and the tetramethyl rhodamine isothiocyanate or fluorescein isothiocyanate conjugated secondary antibody was used. The nuclei were recognized by the stain-ing with DAPI (1 mg/ml). The labeled targets in cells were detected by a confocal laser microscopic system (Leica TCS SP2).

2.8. Detection of tubulin polymerization by cellular fractionation

After the treatment, the cells were harvested by trypsinization and collected by centrifugation. The cells were lysed with 0.1 ml of hypotonic buffer (1 mM MgCl2, 2 mM EGTA, 0.5% NP-40, 2 mM PMSF, 200 U/ml aprotinin, 100 lg/ml soybean tryp-sin inhibitor, 5.0 mM e-amino caproic acid, 1 mM bezamidine and 20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 6.8). The cytosolic and cytoskeletal fraction of cell lysate were separated by centrifugation at 16,000_g for 15 min. The supernatant contained cytosolic tubulin. The pellet representing the particulate fraction of polymerized tubulin was resus-pended in 0.1 ml hypotonic buffer. Tubulin contents in both fractions were detected by Western blotting.

2.9. Small interfering RNA (siRNA) transfection

The Pim-1 siRNA was obtained from Invitrogen (Invitrogen Stealth™ select 3 RNAi Set). The 3 RNAi Set against Pim-1 were 50 -UAU ACA CUC GGG UCC CAU CGA AGU C-30 , 50 -AGA ACA UCU UGC AUC CAU GGA UGG U-30 , and 50 -UUC UUC AGC AGG ACC ACU UCC AUG G-30 . The negative control sequence was 50 -GCC TAC CGT CAG GCT ATC GCG TAT C-30 . For transfection, PC-3 cells were seeded into 60-mm tissue culture dishes with 30% confluence and grown for 24 h to 50–60% con-fluence. Each dish was washed with serum-free Opti-MEM (Life Technologies, Ground Island, NY), and 2 ml of the same medium was added. Aliquots containing siRNA in serum-free Opti-MEM were transfected into cells using Lipofectamine 2000 following the manufacturer's instructions. After incubation for 6 h at 37 LC, cells were washed with medium and incubated in 10% FBS-containing RPMI-1640 medium for 48 h. Then, the cells were treated with or without paclitaxel for the indicated time and the subsequent experiments were performed.

2.10. DNA end-binding activity of Ku proteins

Assessment of DNA end-binding activity of Ku proteins were carried out by using a Ku70/Ku80 DNA Repair kit (Active Motif). Briefly, equivalent amounts of nu-clear proteins (4 lg) were loaded into an oligonucleotide coated 96-well plate. Then, Ku proteins contained in nuclear extract specifically bound to this oligonu-cleotide. Ku proteins antibody provided by this kit detected DNA binding-Ku70 or Ku80. Addition of a secondary HRP-conjugated antibody provided a colorimetric readout quantified by spectrophotometry.

2.11. Pim-1 kinase assay

The assay was performed according to the supplier's protocol (Abnova Pim-1 Kinase Assay/Inhibitor Screening Kit, Heidelberg, Germany). Plates were pre-coated with a substrate corresponding to recombinant p21waf1 containing threonine resi-dues that could be efficiently phosphorylated by Pim-1. The detector antibody spe-cifically detected only the phosphorylated form of Thr145 residue on p21waf1.

2.12. Data analysis

The compound was dissolved in DMSO. The final concentration of DMSO exposed to cells was 0.1%. Data are presented as the mean ± SE of three independent experiments. Statistical analysis of the data was performed with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni t-test and p-values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Induction of Pim-1 up-regulation by tubulin-binding agents

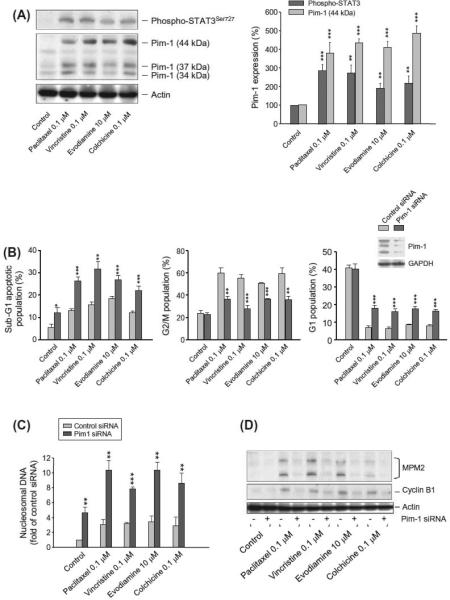

Tubulin-binding agents are widely used in cancer chemother-apy. The activation of STAT3 has been indicated to be associated to the cellular stress caused by tubulin-binding agents in prostate cancer cells [12]. Moreover, STAT3 can bind directly to the Pim-1 promoter and, therefore, is an important mediator for Pim-1 expression [9]. Several tubulin-binding agents were used in this study to examine the effect on STAT3 activity and Pim-1 expres-sion in human hormone-refractory prostate cancer PC-3 cells. The data demonstrated that all of these agents resulted in the acti-vation of STAT3 and a dramatic increase of Pim-1 expression (Fig. 1A). Because Pim-1 is implicated in cell survival and progres-sion of prostate carcinomas, the knockdown of Pim-1 was performed to study its role on intrinsic drug resistance of tubu-lin-binding agents. As a result, apoptotic cell death not only was significantly increased in Pim-1 knockdown cells but also was potentiated by the exposure to these agents (Fig. 1B and C). Furthermore, the mitotic arrest and the increased expression of cyclin B1 and MPM2, phosphorylation of mitosis-specific proteins, induced by tubulin-binding agents were significantly inhibited in the cells with Pim-1 knockdown (Fig. 1B and D).

Fig. 1.

Mutual regulation of tubulin-binding agents and Pim-1. (A) PC-3 cells were treated with or without the indicated agent for 8 h. The cells were harvested and lysed for the detection of protein expression by Western blot analysis. The expression was quantified using the computerized image analysis system ImageQuant. (B and C) PC-3 cells were transfected with or without Pim-1 siRNA. The cells were treated with the indicated agent for 18 or 6 h, respectively. The cell cycle progression (B) and expressions of MPM2 and cyclin B1 (D) were detected using flow cytometric analysis of propidium iodide staining and Western blot, respectively.* p < 0.05,** p < 0.01 and *** p < 0.001 compared with the respective control. (C) The cells were treated with or without the indicated agent for 8 h. The cells were harvested and lysed for the detection of DNA fragmentation using the Cell Death Detection ELISAplus system.

3.2. Effect of Pim-1 on microtubule formation

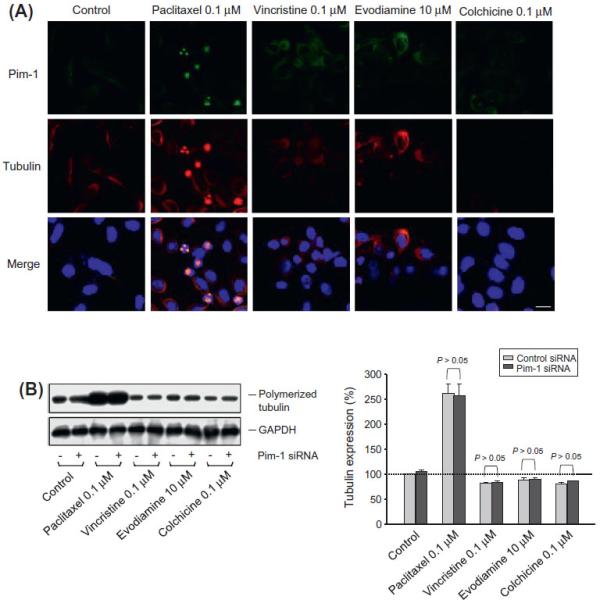

Confocal microscopic examination showed that Pim-1 was primarily located at the cytosol of PC-3 cells. After the exposure to paclitaxel, the microtubule was profoundly stabilized showing strong fluorescence intensity. Notably, Pim-1 localization was associated with the microtubule. Cells treated with the other anti-tubulin agents, vincristine and evodiamine, exhibited a more diffuse cytoplasmic tubulin staining pattern, and colchicine-trea-ted cells displayed almost a complete loss of tubulin staining, all of most probably indicating on tubulin de-polymerization induced by these agents (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, the tubulin polymerization assay in PC-3 cells showed that paclitaxel induced a dramatic in-crease of tubulin polymerization detected in particulate fraction; whereas, the other anti-tubulin agents inhibited the tubulin poly-merization. The knockdown of Pim-1 did not modify the effect of these agents on tubulin polymerizing activity (Fig. 2B), indicating that the induction and potentiation of apoptosis in Pim-1 knock- down cells (Fig. 1B) were not relevant to tubulin dynamics when exposed to these agents.

Fig. 2.

Effect of Pim-1 on cellular microtubule assembly and disassembly. (A) PC-3 cells were treated with the indicated agent for 9 h. The cells were fixed and the protein expression was detected using confocal microscopic examination. Areas of co-localization between Pim-1 and tubulin in the merged images are the yellow demonstration. DAPI was used for nuclear counterstains with blue fluorescence. Scale bar, 20 μm and (B) both parent and Pim-1 knockdown cells were treated with the indicated agent for 18 h. The cells were harvested and the particulate fractions were obtained for the detection of microtubule assembly by Western blot analysis. The tubulin expression was quantified using the computerized image analysis system ImageQuant. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3.3. Effect of paclitaxel on Bcl-2 family member proteins and DNA damage response

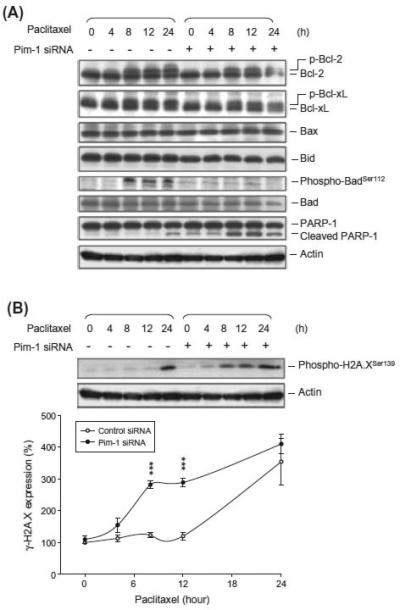

The Bcl-2 family of proteins plays a central role on the regula-tion of mitochondria-mediated apoptosis. Tubulin-binding agents are well identified to induce the phosphorylation and degradation of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family members, such as Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL. The data showed that paclitaxel induced a time-dependent phos-phorylation of Bcl-2, Bcl-xL and Bad (Fig. 3A). The knockdown of Pim-1 did not change the effect on Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL phosphoryla-tion. The Bad phosphorylation, however, was as expected to be completely abolished in Pim-1 knockdown cells since Bad was a di-rect substrate for Pim-1 [26] (Fig. 3A). H2A.X is required for DNA fragmentation and is phosphorylated at Ser139 when exposed to apoptotic stimuli [27,28]. Paclitaxel induced a dramatic increase of H2A.X phosphorylation after a 24-h treatment (Fig. 3B). The data were time correlated with the occurrence of cell apoptosis (supplementary Fig. 1). Moreover, Pim-1 knockdown also significantly accelerated paclitaxel-induced DNA damage response by comet as-say (supplementary Fig. 2). Of note, the apoptosis-associated H2A.X phosphorylation was significantly facilitated in Pim-1 knockdown cells (Fig. 3B). The data reveal that in the presence of paclitaxel, Pim-1 knockdown may trigger a mechanism that leads to an early onset of DNA damage response.

Fig. 3.

Effect of Pim-1 knockdown on the expression of γ-H2A.X and Bcl-2 family protein members in PC-3 cells. Both parent and Pim-1 knockdown cells were treated without or with paclitaxel (0.1 μM) for the indicated times. The cells were harvested for the detection of protein expression by Western blot analysis. The protein expression was quantified using the computerized image analysis system ImageQuant.*** p < 0.001 compared with the control.

3.4. Effect of Pim-1 knockdown on DNA repair system

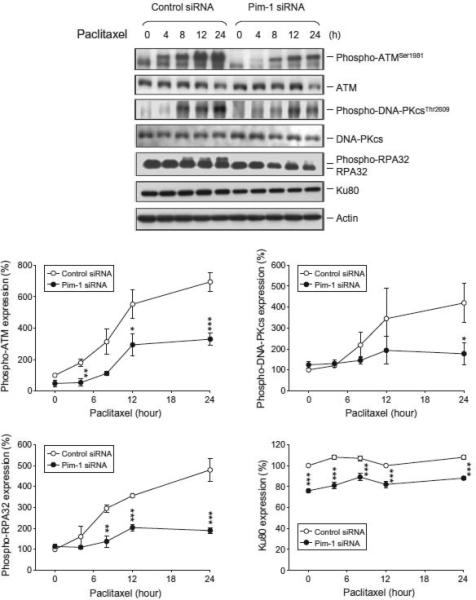

ATM plays a central role in DNA damage checkpoint. It is acti-vated in response to DNA damage, particularly in the presence of double-strand breaks (DSBs). Ku proteins and DNA-PK also play crucial roles in DNA repair, participating in the nonhomologous DNA-end-joining (NHEJ) repair for repairing DSBs [29]. Paclitaxel induced a time-dependent increase of the phosphorylation of ATM, DNA-PK and RPA32 (serving as a DNA-PK substrate), indicat-ing the formation of DNA breaks and processing of DNA repair as a result to paclitaxel action (Fig. 4). However, the activity of these DNA repair kinases was significantly inhibited in Pim-1 knock-down cells. Furthermore, Pim-1 knockdown induced a modest but statistically significant decrease of Ku80 expression (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Effect of Pim-1 knockdown on several protein expressions in PC-3 cells. Both parent and Pim-1 knockdown cells were treated without or with paclitaxel (0.1 μM) for the indicated times. The cells were harvested for the detection of protein expression by Western blot analysis. The protein expression was quantified using the computerized image analysis system ImageQuant.* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.001 and *** p < 0.001 compared with the respective control siRNA.

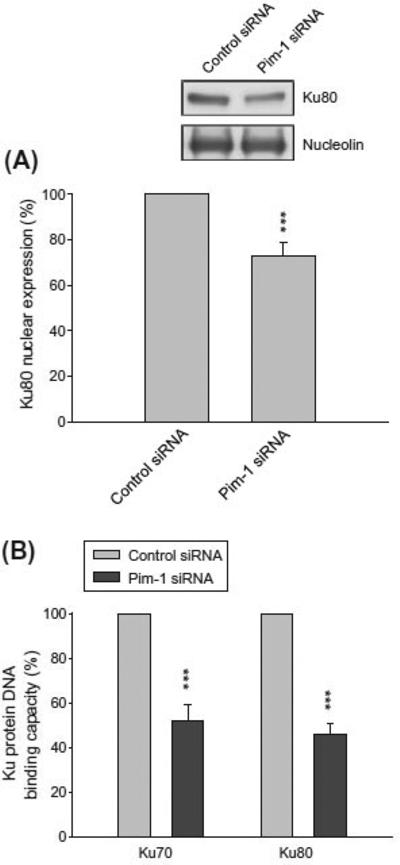

3.5. Effect of Pim-1 knockdown on nuclear localization and DNA binding of Ku proteins

Ku proteins work in nuclei for functional DNA repair. However, several studies have reported cytoplasmic localization of Ku pro-teins [30]. To determine the nuclear localization of Ku proteins, the nuclei were separated from PC-3 cells after the Pim-1 knock-down or not. As a consequence, the nuclear Ku80 was significantly decreased in Pim-1 knockdown cells (Fig. 5A). Besides, the assessment of DNA end-binding activity of Ku proteins was also carried out. The data demonstrated that the Pim-1 knockdown dramati-cally decreased the DNA end-binding of both Ku70 and Ku80 (Fig. 5B). The data were highly correlated with the Pim-1 knock-down-induced reduced activity of the DNA repair kinases de-scribed above (Fig. 4).

Fig. 5.

Effect of Pim-1 knockdown on nuclear localization and DNA binding of Ku proteins in PC-3 cells. Both parent and Pim-1 knockdown cells were harvested. The nuclei were separated and collected for the detection of protein expression by Western blot analysis (A) or for the assessment of DNA end-binding activity of Ku proteins described in Section 2. *** p < 0.001 compared with the respective control.

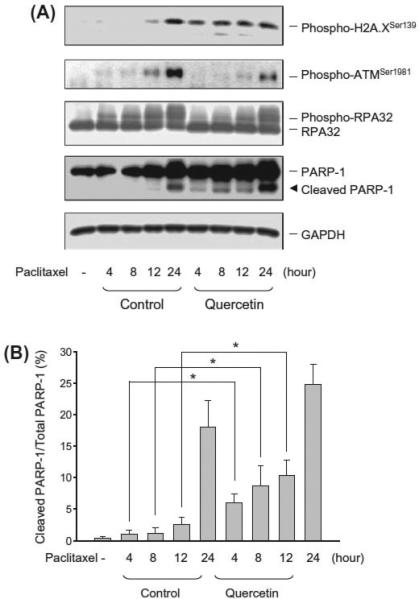

3.6. Effect of Pim-1 inhibitors on DNA repair system

To examine if the inhibition of Pim-1 kinase activity by Pim-1 inhibitors exhibits similar effect to Pim-1 knockdown, the pharmacological inhibitor quercetin was used. The quercetin-mediated inhibitory activity of Pim-1 was determined using recombinant Pim-1 kniase and an in vitro kinase assay. The half maximal inhib-itory concentration (IC50) was 0.17 ± 0.2 lM (n = 4, supplementary Fig. 3). However, a high concentration of 30 lM was used in the PC-3 cell model because the high lipophilicity made the quercetin hard to get to the target [31]. The data showed that in the presence of quercetin, paclitaxel-induced H2A.X phosphorylation and PARP-1 cleavage were facilitated, which was associated with the inhibi-tion of ATM phosphorylation as well as RPA32 phosphorylation (Fig. 6). The data confirm the impact of Pim-1 knockdown on DNA repair activity.

Fig. 6.

Effect of quercetin and paclitaxel on several protein expressions. (A) PC-3 cells were treated with or without paclitaxel (0.1 μM) in the absence or presence of quercetin (30 μM) for the indicated times. The cells were harvested for the detection of protein expression by Western blot analysis and (B) the protein expression was quantified using the computerized image analysis system ImageQuant.* p < 0.05 compared with quercetin-free control.

4. Discussion

Pim-1 has been implicated in the development and progression of hematopoietic malignancies and also in prostate carcinomas by promoting cell survival/proliferation and antagonizing cell apopto-sis. In cancers, STAT3 activity is critical for the transcriptional and translational regulation of Pim-1. However, STAT3 by itself is susceptible to a wide variety of cellular stresses, including the insult by anticancer drugs. Accordingly, the increased STAT3 and Pim-1 kinase activity may contribute to the intrinsic resistance of cancer chemotherapeutic drugs. The data presented in this study showed that tubulin-binding agents induced an increase of STAT3 activity and Pim-1 expression in prostate cancer PC-3 cells. Zemskova and the colleagues [12] have also reported that docetaxel (100 nM) can activate STAT3 and Pim-1 kinase in human prostate epithelial cell line RWPE-2 and prostate cancer cell line DU145. On the contrary, paclitaxel of high concentrations (1.75–7 lM) has been reported to inhibit STAT3 activity in breast cancer cell lines [32]. Although it needs further investigation to clarify the dis-crepancy between these studies, the data raise the resistance issue in patients when tubulin-binding drugs are used for the treatment of prostate cancers.

The knockdown of Pim-1 significantly potentiated the apoptotic cell death caused by tubulin-binding agents. Because the increased expression of Pim-1 by these agents in Pim-1 wild-type cells was tightly associated with tubulin/microtubule, one of the possibili-ties for the potentiated apoptosis was to act on the tubulin/micro-tubule dynamics. However, neither the paclitaxel-induced microtubule stabilization nor the tubulin de-polymerization caused by anti-tubulin agents was modified in Pim-1 knockdown cells. Thus, the possibility that Pim-1 affects tubulin/microtubule dynamics can be excluded as a cause for Pim-1 knockdown-poten-tiated apoptosis.

Mitochondria-dependent signaling pathway contributes a ma-jor part of cell apoptosis induced by tubulin-binding agents. The Bcl-2 family members play a central role in controlling the mito-chondria integrity. A large body of evidence suggests that the phos-phorylation of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL caused by tubulin-binding agents disrupts the mitochondria integrity, leading to the release of cyto-chrome c and activation of caspase cascades [25]. The data in the present study showed that Pim-1 knockdown did not change the phosphorylation state of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL, indicating that Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL were not downstream mediators of Pim-1 kinase. In contrast, the phosphorylation of the pro-apoptotic protein Bad was completely abolished in Pim-1 knockdown cells. Pim-1 has been identified to directly phosphorylate Bad at serine 112, a crit-ical site for its inactivation [26]. Bad phosphorylation is, therefore, suggested to be one of the mechanisms that explain Pim-1-medi-ated pro-survival activity. Nevertheless, the Bad involved mecha-nism could not fully explain the Pim-1 knockdown facilitation of paclitaxel-mediated DNA damage and apoptosis (please see below).

The phosphorylation of histone variant H2A.X at serine 139, also named cH2A.X, has been extensively used as a marker for DSBs, the most lethal form of DNA damage. DSBs can be induced by a lot of events, such as ultraviolet and ionizing radiation, anti-cancer drugs, free radicals and some other apoptotic stimuli [27]. Normally, cells initiate DNA repair mechanism when DNA DSBs oc-cur. Similar effect is also present in paclitaxel-induced cellular DNA damage by which the DNA repair mechanism follows [33]. NHEJ and homologous recombination are two predominant repair path-ways. In response to DSBs, cH2A.X is rapidly formed by several ki-nases, including ATM, ATR and DNA-PKcs [27]. Interestingly, the present data showed that the activation of ATM and DNA-PKcs (at a 4-h and 8-h treatment, Fig. 4) occurred much earlier than the formation of cH2A.X (at a 24-h treatment, Fig. 3B) in cells responsive to paclitaxel. In other words, paclitaxel induced a cH2A.X-independent mechanism of DNA damage response during a 4-h to 12-h treatment. It has been suggested that cH2A.X is dis-pensable for the initial recognition of DNA breaks [34]. The mild defects in DNA damage signaling and DNA repair also have been detected in H2A.X-deficient cells and animals [27,35]. Our data also indicated that cH2A.X-independent while ATM- and DNA-PKcs activated event might provide a mechanism promoting cell survival because paclitaxel did not cause apoptosis during the time of the event. The evidence that ATM and DNA-PKcs promote cell survival has also been reported by Guo and the colleagues [36]. However, Pim-1 knockdown largely facilitated paclitaxel-induced cH2A.X formation and apoptosis, revealing that in the absence of Pim-1 paclitaxel could trigger a rapid DNA damage, leading to apoptotic cell death. The effect was attributed to the inhibition of NHEJ repair activity supported by the following observations: (1) the significant inhibition of ATM and DNA-PKcs activities, (2) the significant down-regulation of Ku protein expression and its nucle-ar localization and (3) the decrease of the DNA end-binding of both Ku70 and Ku80. The Pim-1knockdown-mediated inhibition of DNA repair and potentiation of cell apoptosis are particularly critical in prostate cancers because it has been extensively identified that Pim-1 plays a crucial role in survival of prostate cancers [12]. Pim-1 also serves as a resistance factor in prostate cancers exposed to tubulin-binding drugs [12,37]. To substantiate the role played by Pim-1, the pharmacological Pim-1 inhibitor quercetin was used to mimic the knockdown of Pim-1. As expected, quercetin inhibited ATM activation, facilitating the formation of cH2A.X and cell apop-tosis. There is evidence showing that prostate cancers are over-ex-pressed with ATM [38]. It indicates that ATM may play a central role in DNA repair of prostate cancers. The report correlates with the present study that both Pim-1 knockdown and quercetin-med-iated Pim-1 inhibition block ATM-involved DNA repair system, leading to the sensitization of apoptosis caused by paclitaxel.

In conclusion, the data suggest that Pim-1 plays a crucial role in the regulation of DNA repair in human prostate cancers. Under cel-lular stress, Pim-1 may promote cell survival through ATM-, DNA-PKcs- and Ku protein-involved DNA repair pathway. In the absence of Pim-1, the capability of DNA repair significantly decreases in PC-3 cells in response to paclitaxel, leading to severe DNA damage and apoptosis. The data provide evidence supporting that Pim-1 may serve as a potential target for the treatment of hormone-refractory prostate cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support provided by the National Science Council of the Republic of China (NSC99-2323-B-002-002) and by the National Taiwan University (99R71429).

References

- 1.Wang Z, Bhattacharya N, Weaver M, Petersen K, Meyer M, Gapter L, Magnuson NS. Pim-1: a serine/threonine kinase with a role in cell survival, proliferation, differentiation and tumorigenesis. J. Vet. Sci. 2001;2:167–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen LS, Balakrishnan K, Gandhi V. Inflammation and survival pathways: chronic lymphocytic leukemia as a model system. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2010;80:1936–1945. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.07.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shah N, Pang B, Yeoh KG, Thorn S, Chen CS, Lilly MB, Salto-Tellez M. Potential roles for the PIM1 kinase in human cancer – a molecular and therapeutic appraisal. Eur. J. Cancer. 2008;44:2144–2151. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qian KC, Wang L, Hickey ER, Studts J, Barringer K, Peng C, Kronkaitis A, Li J, White A, Mische S, Farmer B. Structural basis of constitutive activity and a unique nucleotide binding mode of human PIM1 kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:6130–6137. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409123200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bachmann M, Kosan C, Xing PX, Montenarh M, Hoffmann I, Moroy T. The oncogenic serine/threonine kinase Pim-1 directly phosphorylates and activates the G2/M specific phosphatase Cdc25C. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2006;38:430–433. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Z, Bhattacharya N, Mixter PF, Wei W, Sedivy J, Magnuson NS. Phosphorylation of the cell cycle inhibitor p21Cip1/WAF1 by Pim-1 kinase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2002;1593:45–55. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(02)00347-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morishita D, Katayama R, Sekimizu K, Tsuruo T, Fujita N. Pim kinases promote cell cycle progression by phosphorylating and down-regulating p27Kip1 at the transcriptional and posttranscriptional levels. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5076–5085. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valdman A, Fang X, Pang ST, Ekman P, Egevad L. Pim-1 expression in prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and human prostate cancer. Prostate. 2004;60:367–371. doi: 10.1002/pros.20064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bachmann M, Möröy T. The serine/threonine kinase Pim-1. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2005;37:726–730. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aho TL, Lund RJ, Ylikoski EK, Matikainen S, Lahesmaa R, Koskinen PJ. Expression of human PIM family genes is selectively up-regulated by cytokines promoting T helper type 1, but not T helper type 2, cell differentiation. Immunology. 2005;116:82–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2005.02201.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Le QT, Denko NC, Giaccia AJ. Hypoxic gene expression and metastasis. Cancer Metast. Rev. 2004;23:293–310. doi: 10.1023/B:CANC.0000031768.89246.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zemskova M, Sahakian E, Bashkirova S, Lilly M. The PIM1 kinase is a critical component of a survival pathway activated by docetaxel and promotes survival of docetaxel-treated prostate cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:20635–20644. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709479200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Warnecke-Eberz U, Bollschweiler E, Drebber U, Metzger R, Baldus SE, Hölscher AH, Mönig S. Prognostic impact of protein overexpression of the protooncogene PIM-1 in gastric cancer. Anticancer Res. 2009;29(11):4451–4455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reiser-Erkan C, Erkan M, Pan Z, Bekasi S, Giese NA, Streit S, Michalski CW, Friess H, Kleeff J. Hypoxia-inducible proto-oncogene Pim-1 is a prognostic marker in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2008;7:1352–1359. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.9.6418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu Y, Zhang T, Tang H, Zhang S, Liu M, Ren D, Niu Y. Overexpression of PIM-1 is a potential biomarker in prostate carcinoma. J. Surg. Oncol. 2005;92:326–330. doi: 10.1002/jso.20325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brault L, Gasser C, Bracher F, Huber K, Knapp S, Schwaller J. PIM serine/ threonine kinases in the pathogenesis and therapy of hematologic malignancies and solid cancers. Haematologica. 2010;95:1004–1015. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.017079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holder S, Zemskova M, Zhang C, Tabrizizad M, Bremer R, Neidigh JW, Lilly MB. Characterization of a potent and selective small-molecule inhibitor of the PIM1 kinase. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2007;6:163–172. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fedorov O, Marsden B, Pogacic V, Rellos P, Muller S, Bullock AN, Schwaller J, Sundström M, Knapp S. A systematic interaction map of validated kinase inhibitors with Ser/Thr kinases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:20523–20528. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708800104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin YW, Beharry ZM, Hill EG, Song JH, Wang W, Xia Z, Zhang Z, Aplan PD, Aster JC, Smith CD, Kraft AS. A small molecule inhibitor of Pim protein kinases blocks the growth of precursor T-cell lymphoblastic leukemia/ lymphoma. Blood. 2010;115:824–833. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-233445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Macdonald A, Campbell DG, Toth R, McLauchlan H, Hastie CJ, Arthur JS. Pim kinases phosphorylate multiple Bcl-XL. BMC Cell Biol. 2006;7:1–14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-7-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lilly M, Sandholm J, Cooper JJ, Koskinen PJ, Kraft A. The PIM-1 serine kinase prolongs survival and inhibits apoptosis-related mitochondrial dysfunction in part through a bcl-2-dependent pathway. Oncogene. 1999;18:4022–4031. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen WW, Chan DC, Donald C, Lilly MB, Kraft AS. Pim family kinases enhance tumor growth of prostate cancer cells. Mol. Cancer Res. 2005;3:443–451. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-05-0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang F, Beharry ZM, Harris TE, Lilly MB, Smith CD, Mahajan S, Kraft AS. PIM1 protein kinase regulates PRAS40 phosphorylation and mTOR activity in FDCP1 cells. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2009;8:846–853. doi: 10.4161/cbt.8.9.8210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lilly M, Kraft A. Enforced expression of the Mr 33,000 Pim-1 kinase enhances factor-independent survival and inhibits apoptosis in murine myeloid cells. Cancer Res. 1997;57:5348–5355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xie Y, Xu K, Dai B, Guo Z, Jiang T, Chen H, Qiu Y. The 44 kDa Pim-1 kinase directly interacts with tyrosine kinase Etk/BMX and protects human prostate cancer cells from apoptosis induced by chemotherapeutic drugs. Oncogene. 2006;25:70–78. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aho TL, Sandholm J, Peltola KJ, Mankonen HP, Lilly M, Koskinen PJ. Pim-1 kinase promotes inactivation of the pro-apoptotic Bad protein by phosphorylating it on the Ser112 gatekeeper site. FEBS Lett. 2004;571:43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yuan J, Adamski R, Chen J. Focus on histone variant H2AX: to be or not to be. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:3717–3724. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stewart GD, Nanda J, Katz E, Bowman KJ, Christie JG, Brown DJ, McLaren DB, Riddick AC, Ross JA, Jones GD, Habib FK. DNA strand breaks and hypoxia response inhibition mediate the radiosensitisation effect of nitric oxide donors on prostate cancer under varying oxygen conditions. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2011;81:203–210. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Allen C, Ashley AK, Hromas R, Nickoloff JA. More forks on the road to replication stress recovery. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011;3:4–12. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjq049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seluanov A, Danek J, Hause N, Gorbunova V. Changes in the level and distribution of Ku proteins during cellular senescence. DNA Repair (Amst) 2007;6:1740–1748. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Casagrande R, Georgetti SR, Verri WA, Jr., Jabor JR, Santos AC, Fonseca MJ. Evaluation of functional stability of quercetin as a raw material and in different topical formulations by its antilipoperoxidative activity. AAPS Pharm. Sci. Technol. 2006;7:E10. doi: 10.1208/pt070102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walker SR, Chaudhury M, Nelson EA, Frank DA. Microtubule-binding chemotherapeutic agents inhibit signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) signaling. Mol. Pharmacol. 2010;78:903–908. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.066316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Branham MT, Nadin SB, Vargas-Roig LM, Ciocca DR. DNA damage induced by paclitaxel and DNA repair capability of peripheral blood lymphocytes as evaluated by the alkaline comet assay. Mutat. Res. 2004;560:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2004.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Celeste A, Fernandez-Capetillo O, Kruhlak MJ, Pilch DR, Staudt DW, Lee A, Bonner RF, Bonner WM, Nussenzweig A. Histone H2AX phosphorylation is dispensable for the initial recognition of DNA breaks. Nat. Cell Biol. 2003;5:675–679. doi: 10.1038/ncb1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yuan J, Chen J. MRE11–RAD50–NBS1 complex dictates DNA repair independent of H2AX. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:1097–1104. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.078436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guo L, Liu X, Jiang Y, Nishikawa K, Plunkett W. DNA-PK and ATM promote cell survival in response to NK314, a topoisomerase II-alpha inhibitor. Mol. Pharmacol. 2011;80:321–327. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.057125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mumenthaler SM, Ng PY, Hodge A, Bearss D, Berk G, Kanekal S, Redkar S, Taverna P, Agus DB, Jain A. Pharmacologic inhibition of Pim kinases alters prostate cancer cell growth and resensitizes chemoresistant cells to taxanes. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2009;8:2882–2893. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Angèle S, Falconer A, Foster CS, Taniere P, Eeles RA, Hall J. ATM protein overexpression in prostate tumors: possible role in telomere maintenance. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2004;121:231–236. doi: 10.1309/JTKG-GGKU-RFX3-XMGT. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.