Abstract

Both the posterior parietal cortex and the prefrontal cortex are associated with the control of eye movements and attention, but the specific contributions of each area are poorly understood. Here we compare the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) and the lateral intraparietal area (LIP) using a memory saccade task in which a salient distractor was flashed at a variable timing and location during the memory delay. We show that, while the two areas had similar responses to target selection, they had very different contributions to distractor suppression. Responses to the salient distractor were more strongly suppressed and more closely correlated with performance in the dlPFC relative to LIP. Consistent with these findings, reversible inactivation of the dlPFC produced much larger increases in distractibility relative to inactivation of LIP. Along with their shared contributions to eye movement control, the two areas also have important functional specializations and differences in their internal circuitry.

Introduction

To cope effectively with complex environments, organisms must be able to select relevant information and protect it from interference from irrelevant distractions. Achieving this goal requires balancing information processing based on top-down (task-related) and bottom-up (stimulus-related) factors. This balance depends critically on systems of attention and working memory implemented in the parietal and the frontal lobes1–7, and specifically in the lateral intraparietal area (LIP), the frontal eye field (FEF) and the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC)8–12.

Converging evidence in non-human primates shows that frontal and parietal areas contribute jointly to target selection for visual attention and eye movement control. Neurons in LIP, FEF and the dlPFC have spatially tuned activity that selects targets relative to distractors9–11, and microstimulation or reversible inactivation of all three areas affects visual attention and rapid eye movements (saccades)13–18. Although an earlier report has found that neural selection for a salient target arises earlier in LIP relative to the dlPFC19, this difference is not consistently replicated20, 21 suggesting that it may be sensitive to specific task conditions. Moreover, despite possible differences in the timing of their selection response, both LIP and dlPFC show significant target-related responses9–11 and increased oscillatory coherence during target selection19. These findings suggest that frontal and parietal areas have joint contributions and raise important questions about their specific functions.

To date, the studies that have compared LIP and dlPFC have relied on visual search tasks where monkeys must direct gaze to a target in an array of distractors. Although these studies vary the salience of the target and compare efficient with inefficient search (also referred to “bottom-up” versus “top-down” selection)19, 21, they share the property that the target is task-relevant and monkeys must direct gaze to it. However, it remains unknown how the frontal and the parietal lobe process salient distractors that are irrelevant and must be blocked from controlling action. An elegant study has recently shown that, if a salient distractor is flashed during the memory period of a delayed saccade task, monkeys transiently shift attention from the target to the distractor location, and these attention shifts are encoded in LIP22, 23. Importantly however such shifts of attention remain covet – affecting sensory thresholds but not overt saccades. This suggests that the brain possesses dissociable mechanisms for shifting attention and controlling actions, but the mechanisms of this dissociation have remained unknown.

To address this question we compared the LIP and dlPFC using a memory guided saccade task where a salient distractor was flashed at various timings and locations during the memory delay. We show that despite the similarity of their target-selection responses, the two areas had vastly different contributions to distractor suppression. Suppression was much stronger and extended over larger spatial and temporal scales in the dlPFC relative to LIP. Consistent with these results, reversible inactivation of the dlPFC produced much stronger increases in distractibility relative to inactivation of LIP. Despite their joint contributions to target selection, the LIP and dlPFC have significant differences in their internal circuitry and distinct roles in suppressing distractors.

RESULTS

Behavior

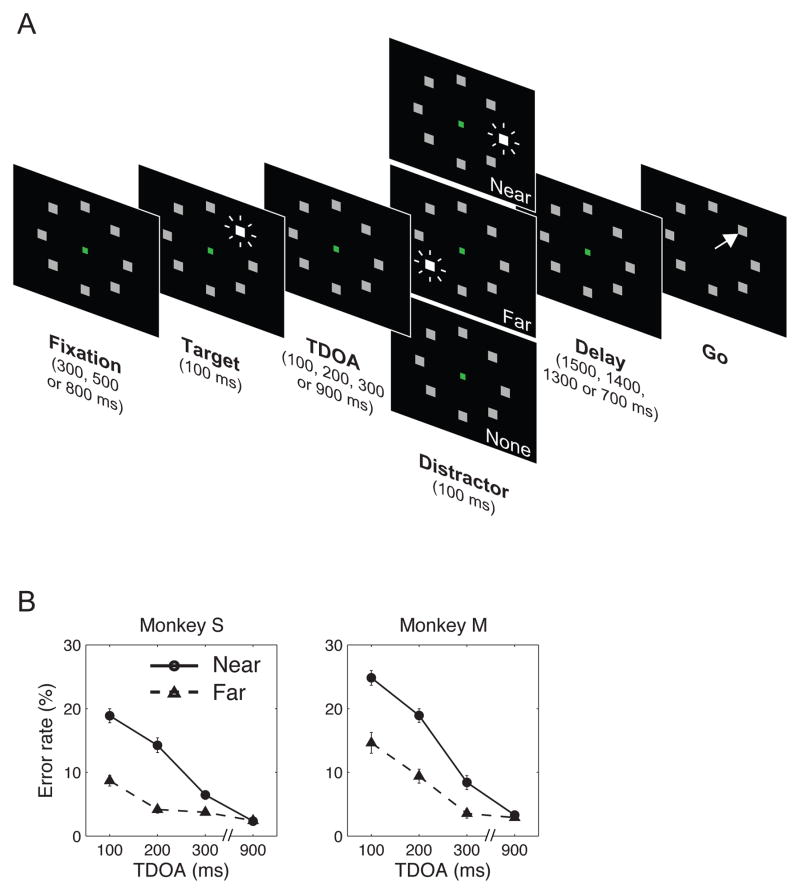

Two monkeys performed a modified version of an oculomotor memory task where they were presented with a 100 ms flash of a peripheral target and, after a 1600 ms delay period, made an eye movement to the remembered target location (Fig. 1A). On 2/3 of the trials a 100 ms distractor was flashed during the delay interval. The distractor onset could occur at target-distractor onset asynchronies (TDOA) of 100, 200, 300 or 900 ms, and at a location that was near the target (45° angular separation) or at a far location (135° or 180° separation). All trial conditions (distractor present/absent, TDOA and distance) were randomly interleaved in a block. The target and distractor were identical in appearance and duration, so that monkeys had to remember the location of the first stimulus and suppress the subsequent distractor.

Figure 1.

A. Task Task stages are shown with time running from left to right. An array of 8 placeholders remained continuously on the screen, and a trial began with a variable period of central fixation. This was followed by a 100 ms flash indicating the target location. After a variable target distractor onset asynchrony (TDOA) a distractor flashed after target presentation. The distractor was identical to the target in appearance and duration, but appeared either at a near-target location (angular separation of 45°) or at far locations (separations 135° or 180°). One third of trials (randomly interleaved) were no-distractor trials. After an additional delay (bringing the total delay period to 1600 ms) the fixation point disappeared (“Go”) and monkeys were rewarded for making a saccade to the target location. B. Performance for each monkey as a function of distractor distance and TDOA (mean and standard error across all recording sessions, n = 89 sessions in monkey S, 47 sessions in monkey M).

As shown in Fig. 1B, both monkeys had near perfect performance if the distractor appeared at a late (900 ms) TDOA at near or far locations, consistent with previous reports23, 24. However, errors became increasingly more common as distractors became more similar to the target in both time and space. A 2-way ANOVA on the error rates revealed significant effects of distance and TDOA, and a significant interaction such that the steepest increase in errors was found for near-target distractors (all p < 0.001, for combined data and each monkey individually). Error saccades were virtually always directed to the distractor location and only rarely to unmarked locations in the display (<3% of trials), and this error pattern remained stable over the course of data collection. Therefore the monkeys’ errors were not due to visual masking or incomplete understanding of the task, but reflected the power of a distractor to interfere with the target-related saccade.

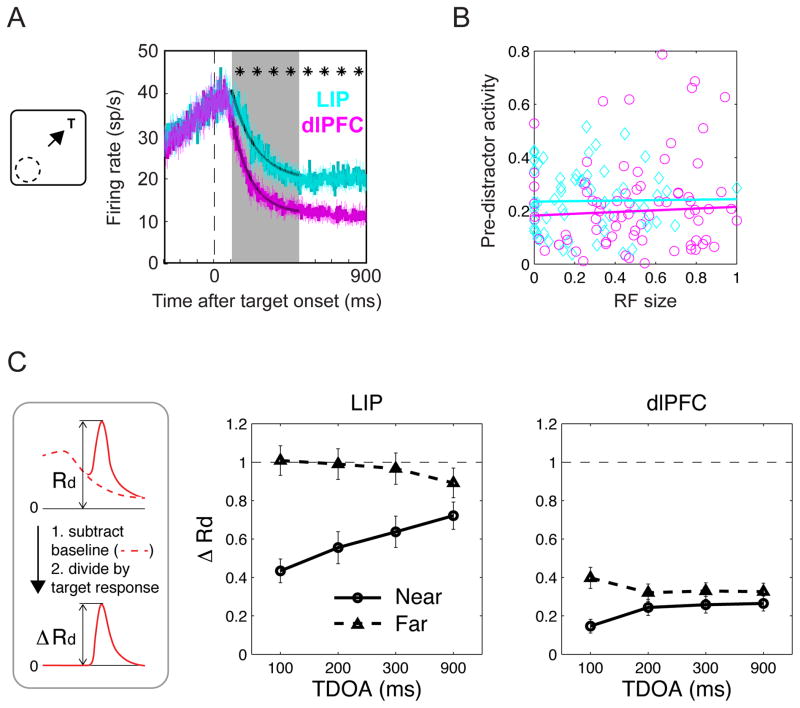

The dlPFC shows much weaker distractor responses relative to LIP

To understand the neural mechanisms mediating the distractor interference, we collected data from 77 spatially tuned neurons in the dlPFC (51 in monkey S, 26 in monkey M) and 59 neurons in LIP (38 in monkey S, 21 in monkey M). All the neurons selected for study had spatial receptive fields (RF) as determined by preliminary testing with the memory guided saccade task (see Methods). During the distractor task the placeholder array was scaled and rotated so that one placeholder fell in the estimated center of a cells’ RF. Therefore on different trials the target, the distractor, or neither stimulus fell onto the central RF location.

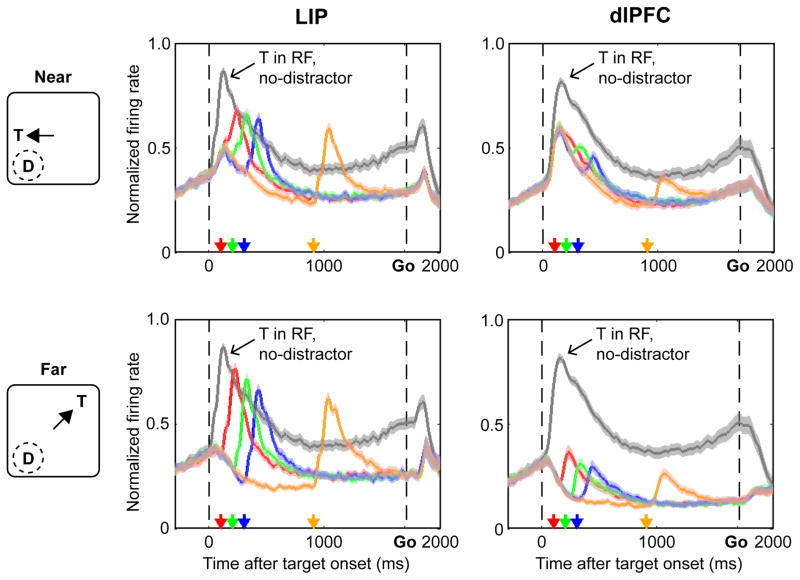

As shown in Fig. 2 (gray traces), neurons in LIP and the dlPFC had similar responses to the task-relevant target, showing a large transient visual response followed by a lower-level activity during the memory delay, consistent with previously-described attentional modulations9, 10, 25, 26. In both areas the sustained response to the target exceeded that at non-target locations, and the peak visual response to the target was stronger than the peak visual response to the onset distractor (1-way ANOVA followed by post-hoc paired tests, p < 0.001 for each distractor distance and TDOA, in each area, in both the combined data and individually in each monkey).

Figure 2. Neural responses in LIP and dlPFC.

Average normalized firing rates in each area aligned on the onset of the target and “Go” signal (times 0 and 1600 ms). The gray traces show trials in which the target (T) was in the RF and no distractor appeared. The colored traces show trials in which a distractor (D) appeared in the RF, at 100, 200, 300 or 900 ms TDOA (red, green, blue and orange arrows and traces). Raw firing rates are smoothed by convolving with a Gaussian kernel (15 ms SD). Firing rates were normalized by dividing each neurons’ activity by its peak target response (T in RF, no-distractor) and the normalized traces were averaged to obtain the population response. Shading shows SEM. As shown in the cartoons, distractor trials were sorted according to whether the target had appeared near the RF (top row) or far from the RF (bottom row).

However, despite their shared responses to target selection, the two areas had markedly different responses to the salient distractors (Fig. 2, colored traces). In the dlPFC the distractors evoked a very weak response even though they appeared in the RF center, while in LIP the distractors evoked a strong response that transiently surpassed the sustained response at the target location. In the following sections we first examine the peak distractor response and its relation with performance. We next compare two distinct mechanisms that determined the peak response: an anticipatory decline in firing that preceded the distractor itself, and a modulation of the additional response evoked by the distractor above the pre-existing rates.

Peak distractor responses in the dlPFC but not in LIP, reflect the monkeys’ behavior

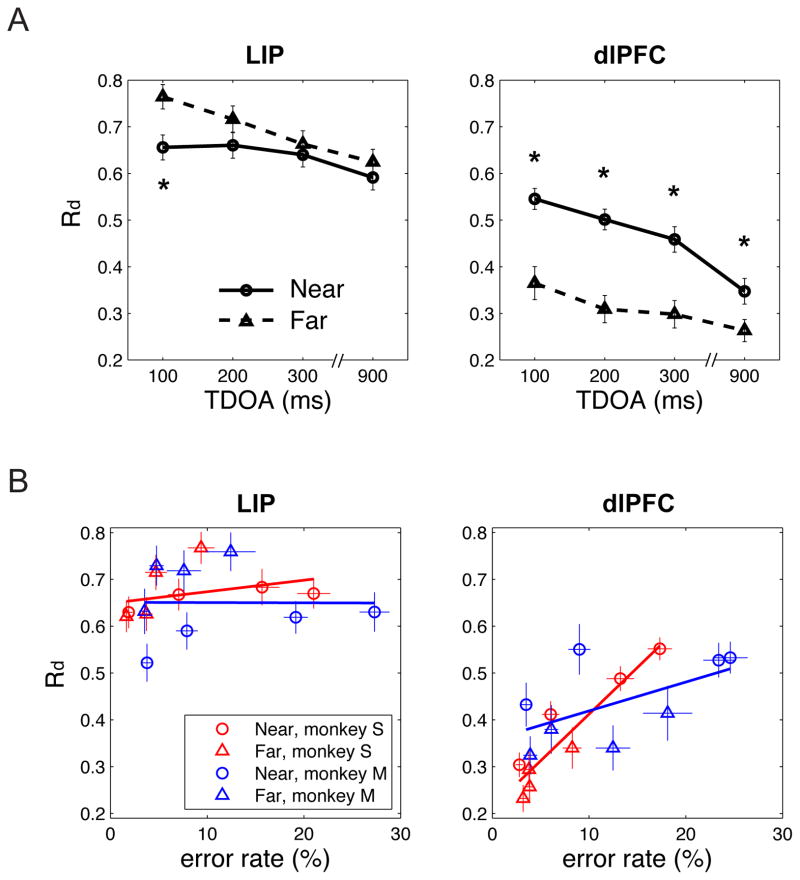

For each distractor distance and TDOA, the peak responses evoked by the distractor were significantly weaker in the dlPFC relative to LIP (1-way ANOVA followed by post-hoc tests, p<0.001 for each comparison). These differences held both in the entire sample (Fig. 2 and Fig. 3A, right vs. left panel) and individually in each monkey (Fig. S1), and remained robust when we examined the raw (not-normalized) firing rates.

Figure 3. Correspondence between distractor responses and error rates.

A The peak normalized response to the distractor (mean and SEM) as a function of distance and TDOA. Stars indicate significant difference between near and far distractors (paired t-test, p<0.001). B The correlation between distractor responses and error rates. Each point shows the fraction of errors and distractor response (mean and SEM) for a different monkey, distance and TDOA.

In addition being weaker, distractor responses in the dlPFC showed a spatio-temporal profile that was more closely correlated with the monkeys’ performance relative to that in LIP. Similar to the monkeys’ error rates, distractor responses in the dlPFC were highest for distractors that were close to the target in space and time (Fig. 3A, right, cf. Fig. 1B), and in a 2-way ANOVA showed significant effects of distance and TDOA, and a significant interaction (all p < 0.001 in the combined data and each monkey individually). Across the different conditions, the distractor responses in the dlPFC were positively correlated with the monkeys’ error rates (Fig. 3B, right; r = 0.31, p < 0.001; monkey S, r = 0.931, p = 0.001; monkey M, r = 0.562, p = 0.147). LIP neurons by contrast showed a different response profile that did not reflect error rates. LIP neurons tended to have stronger responses to the far relative to near distractors (Fig. 3A, left; p < 0.01 for 100 ms TDOA, not significant otherwise) even though the far distractors were more efficiently suppressed by the monkey (cf. Fig. 1B). Across the different conditions, there was no correlation between LIP responses and the monkeys’ error rates (Fig. 3B, left panel; r = 0.0435, p = 0.325; p = 0.405 for monkey S, p = 0.960 for monkey M).

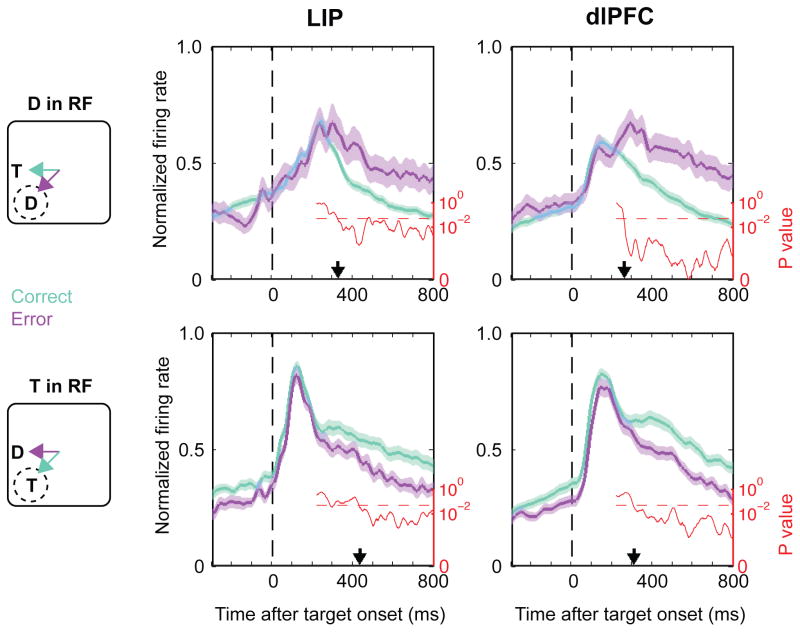

To gain additional insight into the mechanisms leading to an error we analyzed the time at which neurons reported the monkeys’ decision – i.e., discriminated between a correct and error saccade. We focused this analysis on trials with near distractors at 100 ms TDOA that provided the greatest number of errors, and analyzed separately the trials in which the distractor or the target was in the RF (top and bottom rows in Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Analysis of error trials.

Population responses preceding correct saccades (teal) and error saccades (purple) on trials with a near distractor at 100 ms TDOA. After an initial visual response, neural activity became stronger whenever the saccade was directed to the RF center. When a distractor was in the RF (top panels), activity was stronger for an error relative to a correct saccade (top panels). When a target was in the RF (bottom panels), activity was stronger for a correct relative to an error trial. The red trace and axes (log-scale) show the p-values resulting from a sliding window t-test comparing correct and error trials (window width, 1 ms, step size, 1 ms). The dashed line shows the p = 0.05 significance level and the black arrows on the x-axis show the time of consistent discrimination (when the p-values remained consistently below 0.05).

As shown in Fig. 4, activity in both areas was not strictly yoked to the stimulus configuration but reflected the monkeys’ saccades. Activity was higher if the saccade would be directed to the RF center rather than to the adjacent location, whether that saccade was made correctly to the target in the RF (bottom row) or in error to a distractor in the RF (top row). The latency of this neural discrimination however was not stereotyped, but was shortest for the distractor response in the dlPFC. When a distractor was in the RF, dlPFC neurons showed a significant enhancement on an error relative to a correct trial at 259 ms after distractor onset (Fig. 4, top-right panel, arrow and p-values). When the target was in the RF, the neurons showed a significant suppression of the target-related response at 306 ms after distractor onset (Fig. 4, bottom right panel). The corresponding neural events were also reflected in LIP but with a longer time course – i.e., 324 ms for enhancement of the distractor response (Fig. 4, top left panel) and 430 ms for suppression of the target response before an erroneous saccade (Fig. 4, bottom left panel). As the reader may note, the neurons also showed slight differences in their baseline firing rates during the fixation epoch before stimulus presentation (time 0 in Fig. 4), which may have reflected fluctuations in covert attention, motivation or anticipation during the fixation period. These differences however were weak and statistically significant only when the target but not when a distractor was in the RF. Second and most importantly, the differences were no longer visible during the peak visual response (p > 0.1 for in each area and condition), showing that they could not explain the neuronal discrimination of saccade direction. Therefore the earliest consistent predictor of the monkeys’ choice was a failure of distractor suppression in the dlPFC; this was followed by reduction of the target-related response in this area and by the corresponding events in LIP.

Distinct components of distractor suppression

A closer inspection of Fig. 2 suggests that the peak distractor response that we analyzed in the previous section was shaped by two mechanisms. One mechanism was a gradual decrease in firing that developed before the appearance of the distractor itself (e.g., Fig. 2, far condition in the dlPFC, 900 ms TDOA). A second mechanism was a modulation of the additional response evoked by the distractor, which was independent of the pre-existing rates. We analyze each component in turn.

To quantitatively analyze the pre-distractor (anticipatory) suppression we selected trials with 900 ms TDOA and far-target distractors, which showed the strongest effect (Fig. 5A). Focusing on the pre-distractor response, we fitted the target-aligned firing rates with an exponential decay function:

where R are the raw (not normalized) firing rates, t is time (0–500 ms after target onset), R1 is the baseline firing rate (in a 50 ms window centered on target onset), and τ is a fitted time constant. The time constant τ was significantly higher in the dlPFC (9.11, 95% confidence intervals of [8.7629, 9.4613]) relative to LIP (7.13, [6.6663, 7.5941]), showing that response suppression was faster in the former area. Thus, at far distances relative to the target, the pre-distractor suppression was stronger and developed more quickly in the dlPFC relative to LIP.

Figure 5. Anticipatory and visual suppression.

A, Pre-distractor responses in LIP and dlPFC on trials when the target appeared opposite the RF and a distractor appeared at 900 ms TDOA (distractor responses not shown). Histograms show unsmoothed firing rates measured in 2 ms time bins. Black traces show the exponential fit of firing in the 100–500 ms interval indicated by shading. Stars denote 100-ms non-overlapping bins where firing rates differed significantly between LIP and dlPFC (p<0.05). B. Pre-distractor responses for near separations are unrelated to RF size Each point shows the average pre-distractor activity of one neuron for near distractors (800–900 ms after target onset, 900 ms TDOA) as a function of the neuron’s RF size. RF size is defined as the ratio of the magnitude of response to the target presented 45 degree away from the center of RF and in the RF center. Therefore, values close to 1 indicate a wide RF with equivalent responses at the center and adjacent location, while values close to 0 indicate a smaller RF. The lines are best-fit linear regressions. While RF sizes were larger in the dlPFC relative to LIP (p < 0.05) they were not consistently related to the pre-distractor response in either area. C. Visual distractor responses (mean and SEM across all neurons), computed as shown in the left panel. For each distance and TDOA, the additional distractor response (ΔRd) in dlPFC was significantly smaller than in LIP (all p<0.001).

Less suppression by contrast was found at near-target locations (compare Fig. 2, orange traces at near vs. far configurations). A 2-way ANOVA with distance and area as factors (800–900 ms after target onset, 900 ms TDOA) showed that pre-distractor responses were lower at far relative to near separations (p < 0.001 for main effect of distance; p < 0.005 in each monkey). Moreover, there was a significant area x distance interaction, such that the responses at far, but not at near separations were weaker in the dlPFC relative to LIP (p < 0.05 in combined data and each monkey individually). As seen in Fig. 2, in the near condition neurons had a small response to the target (e.g., top panels, short-latency response in the orange trace) suggesting that the target fell within the border of the RF. This early response was significantly stronger relative to the baseline response (p < 0.05) in 67/77 neurons in the dlPFC and 44/59 neurons in LIP. However, the level of this target-related response was not correlated with the neurons’ anticipatory pre-distractor activity (Fig. 5B; r = 0.009, p = 0.952 in LIP and r = 0.201, p = 0.103 in dlPFC). Thus anticipatory suppression is stronger at far relative to near separations independently of the size of the RF.

When the distractor appeared, it evoked an additional response above and beyond the pre-existing rates, which showed a distinct spatio-temporal pattern. To quantitatively measure this component we calculated for each cell the difference between its spike density histograms on distractor and no-distractor trials (cartoon in Fig. 5C). We then found the peak of this difference histogram and measured firing rates in a 100 ms window centered on its peak, and normalized this maximum response by dividing by the peak target response minus the pre-target baseline (the latter measured in the 100 ms window centered on target onset). This quantity, which we refer to as ΔRd, measures the additional response that is evoked by a distractor relative to the additional response evoked by the target, factoring out the neurons’ pre-existing firing rates.

As shown in Fig. 5C, ΔRd was modulated independently of the pre-distractor suppression. While the pre-distractor firing was highest at near separations, ΔRd was weakest at near-target locations. Moreover, at near separations ΔRd tended to increase with time, even as the pre-distractor firing gradually declined (Fig. 2, top panels). A 2-way ANOVA on ΔRd revealed that the effect of distance was significant in both the dlPFC and LIP (each p < 0.001). A significant effect of TDOA and a TDOA x distance interaction was found in LIP (p = 0.005 for each), showing that, at near separations, ΔRd increased significantly as a function of TDOA. In the dlPFC by contrast, there was no effect of TDOA or distance x TDOA interaction (both p > 0.05), showing that ΔRd remained low in all conditions. The low ΔRd at near separations and short TDOAs that was observed in both areas seems similar to the visual adaptation reported in other structures27. However, the fact that in the dlPFC ΔRd remained low even at long TDOAs – that is, outside the range of adaptation - suggests that in this area an additional mechanism suppresses distractor inputs on longer time scales.

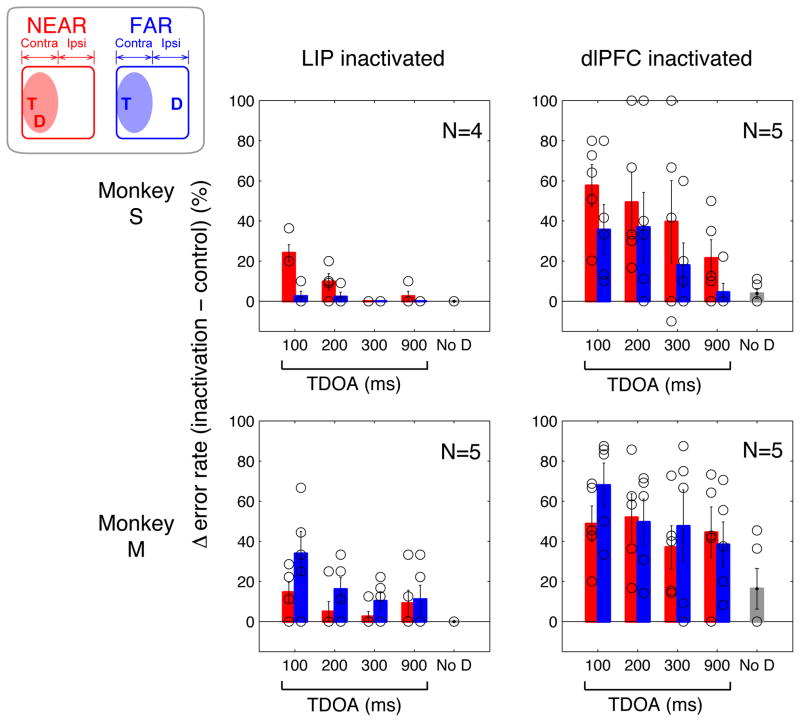

Reversible inactivation

As an additional test of each area’s role in distractor suppression we examined the effects of local reversible inactivation using the GABA-A receptor agonist muscimol 15, 16. At the end of neural recording sessions we made infusions of muscimol (5 mg/ml) at locations where we had previously recorded neurons. A volume of 1 μl of muscimol was injected at 10 sites in the dlPFC (5 in monkey M), and volumes or 3 or 8 μl were injected at 9 sites in LIP (4 in monkey M). Control performance was recorded on interleaved days that had no inactivation.

In trials in which the target was in the hemifield contralateral to the inactivation site (Fig. 6) inactivation of the dlPFC produced a marked increase in errors in each behavioral session (p < 0.001 in each condition). The increase in error rates was larger on distractor relative to no-distractor trials (p = 0.002; p = 0.050 for monkey S, p = 0.014 for monkey M), suggesting that the inactivation particularly impaired the monkeys’ ability to suppress distractors. However if a distractor appeared the increase in errors was similar across distractor conditions (2-way ANOVA, effect of TDOA, p = 0.069 in monkey S, p = 0.479 in monkey M; effects of distance and interaction, all p > 0.05). These widespread inactivation effects are consistent with the neural results showing that dlPFC distractor suppression was strong at all distances and TDOAs. In addition to increasing the rate of distractor directed saccades, dlPFC inactivation produced an increase in the frequency of fixation breaks both before and after target presentation (Supplementary Fig. 2; 1-way ANOVA inactivation vs. control, p < 0.05 for monkey S, p < 0.001 for monkey M).

Figure 6. Effects of reversible inactivation of LIP and dlPFC.

As shown in the cartoon at the top left, in the trials shown here the target was in the hemifield contralateral to the inactivation site (shading) and was accompanied either by a near distractor (shown in red) or by a far distractor (blue). In the data panels each circle shows the difference in error rate between a single inactivation and control session. The bars show the average and SEM. In both monkeys for all TDOAs and distances, dlPFC inactivation induced more errors than LIP inactivation. The deficits were larger on trials that did, relative to those that did not contain a distractor (no-D, gray bars).

Inactivation of LIP (Fig. 6, left) also produced a significant increase in error rates if the target was in the contralateral field (p < 0.001 overall; monkey S, p = 0.003, monkey M, p < 0.001). These deficits were comparable to those described previously on visual search tasks13–15, showing that the inactivation procedures were effective. These deficits however were much milder relative to those obtained in the dlPFC (Fig. 6, left vs right panels, 1-way ANOVA, p < 0.001 for effect of area in each monkey). This result could not be explained by injection size as larger muscimol amounts were consistently injected in LIP (3–8 μl) relative to dlPFC (1μl).

In addition monkey S, who received only the larger 8 μl injections, tended to show a milder behavioral deficit relative to monkey M, who received both 3 and 8 μl injections (top vs. bottom panels; p < 0.07 for effect of monkey). As for the dlPFC, LIP inactivation produced no errors on no-distractor trials, but in contrast with the dlPFC, the increase in error rates after LIP inactivation did show a small dependence on timing, such that larger deficits occurred at short TDOAs (2-way ANOVA for distance and TDOA, p < 0.001 for monkey S, p < 0.05 for monkey M for main effect of TDOA), and had an inconsistent dependence on distance (monkey S, larger effects for far, p < 0.001; monkey M, larger effects for near, p < 0.05). Also in contrast with the dlPFC, LIP inactivation did not affect the number of fixation breaks (Supplementary Fig. 2; all p > 0.05). These findings suggest that LIP has a moderate contribution to distractor suppression that is restricted to distractors at short TDOAs.

Consistent with the neurons’ contralateral RF, inactivation did not impair performance on trials in which the target was ipsilateral to the inactivated hemisphere (Supplementary Fig. 3). Interestingly in monkey S a significant improvement in performance was seen after inactivation of dlPFC (lower error rates, p < 0.001) as well as LIP (p = 0.046; the effects were not replicated in monkey M: dlPFC, p = 0.91, LIP, p = 0.41). This apparently counterintuitive result may reflect the fact that inactivation further reduced the distractor response on these trials, arguing against the possibility that distractor responses inhibited remote structures (see Discussion).

DISCUSSION

We show that, despite the similarity in their target selection response, the LIP and dlPFC have vastly different contributions to distractor suppression. Distractor evoked responses were weaker and more tightly correlated with performance in the dlPFC relative to LIP. Consistent with these findings, reversible inactivation of the dlPFC produced much greater impairment in distractor suppression relative to inactivation of LIP. Along with their shared contributions to target selection, the LIP and dlPFC also have important functional dissociations and differences between their internal circuitries.

Distinct frontal and parietal contributions to attention control

The central finding we report is that relative to LIP, the dlPFC had a much more critical role in suppressing an irrelevant distractor and preventing it from generating inappropriate actions. Importantly however, the suppressive function we describe is distinct from previously described motor inhibition mechanisms. While these mechanisms used excitatory responses to inhibit motor structures, distractor suppression in our task was implemented locally within the dlPFC.

One important mechanism of saccadic control is mediated by fixation neurons (in the substantia nigra, superior colliculus and the frontal lobes) that are tonically active during stationary fixation and can inhibit the activation of saccade movement cells unless (or until) a saccade becomes appropriate28–30. A second mechanism is mediated by a set of so-called “don’t look” cells that have been described in the pre-supplementary motor area31 and at prefrontal sites more posterior to the ones we investigate32, and which generate transient bursts of excitation when monkeys must cancel a pre-planned saccade.

The dlPFC results we report are inconsistent with both mechanisms. In a clear contrast with fixation cells, dlPFC neurons were not tonically active during sustained fixation but responded in spatially specific manner to the target and distractor locations. In clear contrast with the “don’t look” cells, the neurons responded very weakly to the salient distractors, and had even weaker responses when the saccade was successfully suppressed (i.e., on correct relative to error trials), inconsistent with the idea that they provide an inhibitory drive. Additional evidence supporting this conclusion comes from the inactivation results. While inactivation of an inhibitory mechanism is expected to elevate error rates by reducing the inhibitory drive at the distractor location31, we found that inactivation had no effect or even improved performance when the distractor was in the affected field (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Taken together these considerations show that the suppression we report was implemented locally within the dlPFC without inhibition of remote structures. This distinct form of suppression is most likely explained by our task demands. In studies of saccade inhibition monkeys have strong incentive to plan a saccade and only occasionally must cancel or redirect this saccade, maximizing the need for motor inhibition. In the present task by contrast the distractor was always task-irrelevant and monkeys were never rewarded for making a saccade to it. This provides maximal incentive to generate anticipatory suppression that curtails the earliest component of a distractor response33, as we found in the dlPFC (e.g., Fig. 2, 3). Such anticipatory suppression therefore, which reduces the visual response to an irrelevant distractor, depends on intrinsic frontal mechanisms.

The manipulations we have used - the planning of a memory-guided saccade and an abrupt onset distractor - are powerful attentional cues34, 35 and it is likely that, in addition to involving saccade planning, our task recruited covert (perceptual) attention. Supporting this idea, a previous study that used a similar paradigm shows that covert attention – defined as a reduction in contrast thresholds – shifted between the target and distractor locations according to the balance of activity in LIP22, 23. Similar with this study we find that LIP neurons had stronger responses at the target relative to distractor locations throughout most of the delay period, but the balance shifted transiently after distractor onset, suggesting that attention was transiently focused on the distractor location22, 23. We also note that despite their relatively strong distractor responses, LIP did show the expected attentional effects: neurons had stronger responses to the target relative to the distractors (measured in the peak firing rates, pre-distractor responses and additional response evoked by the distractor, Fig. 2,3,5) and, upon reversible inactivation produced a modest deficit13–15. These considerations suggest that both LIP and the dlPFC were involved in visual selection but played different roles. While LIP reflected covert shifts of attention between the target and the distractor locations, the dlPFC had a determining influence on how the stimuli influenced action.

Similar to LIP, dlPFC neurons had strong response to the target location, and these responses could have contributed to the top-down attentional drive36. However, as we have discussed in relation to motor mechanisms, it is unlikely that the dlPFC directly inhibited a visual distractor response. To the extent that feedback from the frontal lobe produces distractor suppression36 this suppression is likely to arise indirectly – e.g., through an enhancement of a target representation followed by competition in the posterior areas - rather than through a direct inhibitory mechanism. This conclusion is consistent with the recent anatomical finding that frontal projections to V4 and LIP terminate overwhelmingly onto spiny (excitatory) cells37.

Implications for attractor models and local circuitry

In addition to implying functional specializations, the distinct response patterns we observe suggest that the LIP and dlPFC differ in their local circuitry. A leading computational model of spatial working memory is based on attractor networks, which generate persistent activity by virtue of local recurrent excitation balanced by global inhibition to remote neuronal pools38. Our findings are consistent with the idea that an attractor architecture is implemented in the dlPFC but not in LIP.

Computational models of attractor networks make several predictions that were confirmed in the dlPFC. One important prediction of an attractor architecture is a similarity effect whereby distractors that are more similar to the target generate stronger interference (because they activate a population of cells that overlaps with that responding to the target and are more weakly suppressed)39. A similarity effect was seen in the monkeys’ performance, with the largest fraction of errors being triggered by distractors located at near relative to far-target locations. This proximity effect was reflected in the peak responses in the dlPFC, which were stronger at near relative to far distractor locations (Fig. 3A, right). In LIP however we obtained the opposite result, with neurons tending to show stronger responses for far-target distractors, at odds with an attractor regime (Fig. 3A, left).

A second defining feature of an attractor network is the critical role of distractor suppression. Because a strong bottom-up input will force the network to transition to a new attractor state, suppressing this input is critical for protecting the integrity of a memory trace40, 41. Consistent with this prediction we found that distractor responses in the dlPFC were strongly suppressed, and a failure of suppression was the earliest event predicting an error (Fig. 4). In stark contrast however, LIP neurons maintained their target-evoked responses even while responding strongly to the salient distractor. This phenomenon had been noted previously for distant target and distractor locations (when the two stimuli are encoded in opposite hemispheres)23, 24, 42, but here we show that it generalizes to near-target locations. One possibility is that LIP implements an attractor network but uses a different gating mechanism for governing the transition from transient to sustained activity. This seems unlikely because inactivation of LIP had only a weak effect on behavioral distractibility, suggesting that its sustained target-related response was not critical for correct performance. A more parsimonious interpretation is that LIP does not generate sustained activity through an attractor mechanism, but derives its sustained response through feedback from the frontal lobe.

Finally, consistent with the strong long-range inhibition in an attractor regime, our findings show that the dlPFC implemented several inhibitory mechanisms that acted on longer spatial and temporal scales. One such mechanism was an anticipatory reduction in the neurons’ firing rates that was strongest at far distractor locations, and was stronger in the dlPFC relative to LIP. This anticipatory suppression may be produced by parvalbumin-reactive basket cells that form extensive terminal plexi on the cell bodies of pyramidal cells and may curtail the spiking output of neurons at remote locations43, 44.

A second class of mechanism produced a specific reduction in the additional distractor response (ΔRd in Fig. 5C). This input-specific suppression had a local, transient component that reduced ΔRd at near-target locations at short TDOA, and acted in both LIP and in the dlPFC. This form of suppression may be explained by cell-intrinsic adaptation as has been proposed previously for the superior colliculus and the FEF27, 45. In the dlPFC however, ΔRd remained low even at long TDOAs - outside of the time window of transient adaptation – and at near-separations – outside the range of pre-distractor suppression. This suggests that the dlPFC implements an additional form of suppression that acts specifically on a visual input and on longer time-scales. This mechanism may be mediated by inhibitory synapses on pyramidal dendrites from calbindin-positive interneurons or somatostatin-expressing Martinotti cells43, 46, 47, that may be particularly prevalent in the dlPFC.

Materials and Methods

Two adult male rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) weighing 8–10 kg were tested with standard behavioral and neurophysiological techniques as described previously48. All methods were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committees of Columbia University and New York State Psychiatric Institute as complying with the guidelines within the Public Health Service Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Data were analyzed offline using Matlab (MathWorks). Visual stimuli were displayed on an MS3400V XGA high-definition monitor (62.5X46.5 cm viewing area; CTX International) located 57 cm in front of the monkeys’ eyes. The time of all visual transients was measured by means of a photodiode mounted on the screen that indicated the onset of a vertical refresh.

Electrode tracks were aimed based on stereotactic coordinates and structural MRI. For LIP, tracks were aimed to the lateral bank of the intraparietal sulcus and for the dlPFC, they targeted the posterior portion of the principal sulcus just anterior to the pre-arcuate region from which saccades are elicited with low-threshold microstimulation (FEF) 49. Neurons were tested further if they had spatially tuned activity on a standard memory-guided saccade task 50. Post-hoc testing showed that all neurons had spatial tuning during the visual epoch and the vast majority maintained this tuning during the memory delay (800–1200 ms after target onset; 33/46 neurons in LIP, 68/77 in dlPFC; p < 0.05; 1-way ANOVA for spatial tuning).

To measure distractor responses (Fig. 2 and 3) firing rates were smoothed with a Gaussian filter (15 ms standard deviation) and normalized for each cell by dividing by the peak target-evoked response (T in RF, no-distractor). Because individual cells showed consistent visual latencies (as can be appreciated in the sharp onset of the population response) we measured visual responses in a 100 ms time window that remained constant across cells. In one analysis method we centered the window on the latency of the peak population response to the target (gray trace in Fig. 2) and at the corresponding latency for each distractor TDOA. In a second method we centered the window on the peak distractor response for each TDOA. These methods yielded equivalent findings, and for simplicity only the former is reported in the text. Baseline firing rates were measured in a 100 ms window centered on the target onset, except when computing ΔRd, when we subtracted the neural response on no-distractor trials as described for Fig. 5C.

Because different cells were tested with “far” distractors that had either a 135 or a 180 degree angular separation, we could further examine whether suppression differed when the target and distractor were in the same or in opposite hemifields. We separated neurons into 3 distinct classes: neurons tested with same-hemifield-135 degree distractors (n = 19 in LIP, 25 in dlPFC), with opposite-hemifield-135 degree distractors (n = 20 in LIP, 25 in dlPFC) and with 180-degree distractors (all opposite hemifield; n = 20 in LIP, 24 in dlPFC). We found no significant difference of these distractor conditions in any area or monkey and for any TDOA (all p > 0.1), suggesting that the suppression of remote distractors was equivalent within and across the different hemifields.

Muscimol injections were targeted to recording coordinates that yielded reliable visuospatial tuning during the recording sessions in both dlPFC and LIP (in the right hemisphere in monkey M and left hemisphere in monkey S). Muscimol (Sigma) was dissolved in PBS, pH~7, to concentrations of 5.0 mg/ml and immediately before an experiment, was backfilled into a 10 μl Hamilton syringe (Recording Micro Syringe MRM-S02; Crist Instruments). To limit damage to neural tissue, we performed a single needle track in each experiment and infused muscimol at a single depth along the track. When possible, we confirmed the presence of spatially tuned activity before injection and the silencing of this activity after the injection by multiunit recording through an electrode attached to the Hamilton syringe. Infusion depths ranged between 2 and 6 mm (mean±SD, 3.8±1.1 mm) below the cortical surface. To avoid pressure damage, injections were made in small steps of 0.5 μl at 2–3 min intervals. The total volume injected was 1 μl for dlPFC and between 3 and 8 μl for LIP, corresponding to a total amount of 5 μg of muscimol for dlPFC and 15–40 μg for LIP. Behavioral testing was completed within 2.5 h after the muscimol infusion. Control data were obtained on alternate days without inactivation, using precisely the same tasks, presentation order, and parameters as during the inactivation session. During 4 injections of physiological saline injection (one in each area in each monkey) we found no significant difference between no-injection and post-injection data, showing that the effects could not be explained by nonspecific tissue damage produced by injection pressure.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Swiss National Science Foundation Fellowship (PBELB-120948) and a Human Frontier Science Program Cross-Disciplinary Fellowship to M.S. (LT00934/2008-C).

Footnotes

Disclosure statement:

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Badre D, Wagner AD. Left ventrolateral prefrontal cortex and the cognitive control of memory. Neuropsychologia. 2007;45:2883–2901. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corbetta M, Shulman GL. Control of goal-directed and stimulus-driven attention in the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:201–215. doi: 10.1038/nrn755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Egeth HE, Yantis S. Visual attention: control, representation, and time course. Annu Rev Psychol. 1997;48:269–297. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bays PM, Singh-Curry V, Gorgoraptis N, Driver J, Husain M. Integration of goal- and stimulus-related visual signals revealed by damage to human parietal cortex. J Neurosci. 2010;30:5968–5978. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0997-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klingberg T. Development of a superior frontal-intraparietal network for visuo-spatial working memory. Neuropsychologia. 2006;44:2171–2177. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2005.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doyle AE. Executive functions in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:21–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown GG, Thompson WK. Functional brain imaging in schizophrenia: selected results and methods. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2010;4:181–214. doi: 10.1007/7854_2010_54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gottlieb J. From thought to action: the parietal cortex as a bridge between perception, action, and cognition. Neuron. 2007;53:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chafee MV, Goldman-Rakic PS. Inactivation of parietal and prefrontal cortex reveals interdependence of neural activity during memory-guided saccades. J Neurophysiol. 2000;83:1550–1566. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.3.1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chafee MV, Goldman-Rakic PS. Matching patterns of activity in primate prefrontal area 8a and parietal area 7ip neurons during a spatial working memory task. J Neurophysiol. 1998;79:2919–2940. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.6.2919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldman-Rakic PS. Cellular basis of working memory. Neuron. 1995;14:477–485. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90304-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller EK, Cohen JD. AN INTEGRATIVE THEORY OF PREFRONTAL CORTEX FUNCTION. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:167–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wardak C, Olivier E, Duhamel JR. A deficit in covert attention after parietal cortex inactivation in the monkey. Neuron. 2004;42:501–508. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00185-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wardak C, Olivier E, Duhamel JR. Saccadic target selection deficits after lateral intraparietal area inactivation in monkeys. J Neurosci. 2002;22:9877–9884. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-22-09877.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Balan PF, Gottlieb J. Functional significance of nonspatial information in monkey lateral intraparietal area. J Neurosci. 2009;29:8166–8176. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0243-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sawaguchi T, Iba M. Prefrontal cortical representation of visuospatial working memory in monkeys examined by local inactivation with muscimol. J Neurophysiol. 2001;86:2041–2053. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.4.2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wardak C, Ibos G, Duhamel JR, Olivier E. Contribution of the monkey frontal eye field to covert visual attention. J Neurosci. 2006;26:4228–4235. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3336-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moore T, Armstrong KM. Selective gating of visual signals by microstimulation of frontal cortex. Nature. 2003;421:370–373. doi: 10.1038/nature01341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buschman TJ, Miller EK. Top-down versus bottom-up control of attention in the prefrontal and posterior parietal cortices. Science. 2007;315:1860–1862. doi: 10.1126/science.1138071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schall JD, Pare M, Woodman GF. Comment on “Top-down versus bottom-up control of attention in the prefrontal and posterior parietal cortices”. Science. 318:44. doi: 10.1126/science.1144865. author reply 44 (2007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katsuki F, Constantinidis C. Early involvement of prefrontal cortex in visual bottom-up attention. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:1160–1166. doi: 10.1038/nn.3164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bisley JW, Goldberg ME. Neural correlates of attention and distractibility in the lateral intraparietal area. J Neurophysiol. 2006;95:1696–1717. doi: 10.1152/jn.00848.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bisley JW, Goldberg ME. Neuronal activity in the lateral intraparietal area and spatial attention. Science. 2003;299:81–86. doi: 10.1126/science.1077395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Powell KD, Goldberg ME. Response of neurons in the lateral intraparietal area to a distractor flashed during the delay period of a memory-guided saccade. J Neurophysiol. 2000;84:301–310. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.84.1.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bisley J, Goldberg M. Attention, intention, and priority in the parietal lobe. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2010;33:1–21. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-060909-152823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katsuki F, Constantinidis C. Unique and shared roles of the posterior parietal and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in cognitive functions. Front Integr Neurosci. 2012;6:17. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2012.00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mayo JP, Sommer MA. Neuronal adaptation caused by sequential visual stimulation in the frontal eye field. J Neurophysiol. 2008;100:1923–1935. doi: 10.1152/jn.90549.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Purcell BA, Schall JD, Logan GD, Palmeri TJ. From salience to saccades: multiple-alternative gated stochastic accumulator model of visual search. Journal of Neuroscience. 2012;32:3433–3446. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4622-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schall JD, Purcell BA, Heitz RP, Logan GD, Palmeri TJ. Neural mechanisms of saccade target selection: gated accumulator model of the visual-motor cascade. Eur J Neurosci. 2011;33:1991–2002. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07715.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lo CC, Wang XJ. Cortico-basal ganglia circuit mechanism for a decision threshold in reaction time tasks. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:956–963. doi: 10.1038/nn1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Isoda M, Hikosaka O. Switching from automatic to controlled action by monkey medial frontal cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:240–248. doi: 10.1038/nn1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hasegawa RP, Peterson BW, Goldberg ME. Prefrontal neurons coding suppression of specific saccades. Neuron. 2004;43:415–425. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ruff CC, Driver J. Attentional preparation for a lateralized visual distractor: behavioral and fMRI evidence. J Cogn Neurosci. 2006;18:522–538. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2006.18.4.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kowler E, Anderson E, Dosher B, Blaser E. The role of attention in the programming of saccades. Vision Res. 1995;35:1897–1916. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(94)00279-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Theeuwes J. Top-down and bottom-up control of visual selection. Acta Psychol (Amst) 2010;135:77–99. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moore T, Armstrong KM. Selective gating of visual signals by microstimulation of frontal cortex. Nature. 2003;421:370–373. doi: 10.1038/nature01341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anderson JC, Kennedy H, Martin KA. Pathways of attention: synaptic relationships of frontal eye field to V4, lateral intraparietal cortex, and area 46 in macaque monkey. J Neurosci. 2011;31:10872–10881. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0622-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang XJ. Attractor Network Models. In: Squire LR, editor. Encyclopedia of Neuroscience. Academic Press; Oxford: 2009. pp. 667–679. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Furman M, Wang XJ. Similarity effect and optimal control of multiple-choice decision making. Neuron. 2008;60:1153–1168. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brunel N, Wang XJ. Effects of neuromodulation in a cortical network model of object working memory dominated by recurrent inhibition. J Comput Neurosci. 2001;11:63–85. doi: 10.1023/a:1011204814320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Compte A, Brunel N, Goldman-Rakic PS, Wang XJ. Synaptic mechanisms and network dynamics underlying spatial working memory in a cortical network model. Cereb Cortex. 2000;10:910–923. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.9.910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ganguli S, et al. One-dimensional dynamics of attention and decision making in LIP. Neuron. 2008;58:15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang XJ, Tegner J, Constantinidis C, Goldman-Rakic PS. Division of labor among distinct subtypes of inhibitory neurons in a cortical microcircuit of working memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:1368–1373. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305337101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kisvarday ZF, et al. One axon-multiple functions: specificity of lateral inhibitory connections by large basket cells. J Neurocytol. 2002;31:255–264. doi: 10.1023/a:1024122009448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boehnke SE, et al. Visual adaptation and novelty responses in the superior colliculus. Eur J Neurosci. 2011;34:766–779. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07805.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Somogyi P, Tamas G, Lujan R, Buhl EH. Salient features of synaptic organisation in the cerebral cortex. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1998;26:113–135. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(97)00061-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Silberberg G, Markram H. Disynaptic inhibition between neocortical pyramidal cells mediated by Martinotti cells. Neuron. 2007;53:735–746. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oristaglio J, Schneider DM, Balan PF, Gottlieb J. Integration of visuospatial and effector information during symbolically cued limb movements in monkey lateral intraparietal area. J Neurosci. 2006;26:8310–8319. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1779-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bruce CJ, Goldberg ME, Stanton GB, Bushnell MC. Primate frontal eye fields. II. Physiological and anatomical correlates of electrically evoked eye movements. J Neurophysiol. 1985;54:714–734. doi: 10.1152/jn.1985.54.3.714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barash S, Bracewell RM, Fogassi L, Gnadt JW, Andersen RA. Saccade-related activity in the lateral intraparietal area. I. Temporal properties; comparison with area 7a. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1991;66:1095–1108. doi: 10.1152/jn.1991.66.3.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.