Version Changes

Revised. Amendments from Version 1

Thank you to the reviewers for their time and thoughtful comments regarding our article. We have addressed each concern listed by the reviewers below: The statement regarding GLI1 being conserved from Drosophila to humans was corrected to “the GLI family of transcription factors is highly conserved and is required for developmental response via transcriptional regulation of target genes” in the Introduction. An additional figure was added to the review (Figure 1) to describe the various pathways that modulate GLI1 expression as discussed in the review. Figure 1 from the first version of this article was changed to Figure 2. “LET-dependent” was corrected to “β-catenin/LEF-TCF-dependent” in the “Hedgehog-Independent Mechanisms for GLI1 Expression in PDAC” section. We added additional considerations regarding other factors that may drive down GLI1 levels during PDAC progression to the “Discussion” section. Mechanisms included are activation of DYRK1B kinase, which promotes a shift from autocrine to paracrine signaling, which may lead to decreased GLI1 expression. Also, decreased HH signaling in advanced PDAC may allow for increased expression of GLI1 repressors. Additional considerations were added concerning the use of SMO inhibitors and downstream GLI-independent effects to the Discussion section. The following statement was added to the final paragraph of the Discussion section “Further studies are needed to fully understand the role of GLI1 in PDAC carcinogenesis. While there is evidence for a dual role of GLI1 in PDAC, this phenomenon has yet to be linked with other cancer types.”

Abstract

Aberrant activation of the transcription factor GLI1, a central effector of the Hedgehog (HH) pathway, is associated with several malignancies, including pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), one of most deadly human cancers. GLI1 has been described as an oncogene in PDAC, making it a promising target for drug therapy. Surprisingly, clinical trials targeting HH/GLI1 axis in advanced PDAC were unsuccessful, leaving investigators questioning the mechanism behind these failures. Recent evidence suggests the loss of GLI1 in the later stages of PDAC may actually accelerate disease. This indicates GLI1 may play a dual role in PDAC, acting as an oncogene in the early stages of disease and a tumor-suppressor in the late stages.

Keywords: GLI1, Pancreatic Cancer, Carcinogenesis, Hedgehog, HH, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, PDAC

Introduction

The protein GLI1, originally isolated in 1987 due to high levels of amplification in malignant glioma ( Kinzler et al., 1987), is a member of the GLI family of transcription factors. This family also includes GLI2 and GLI3. The GLI family of transcription factors is highly conserved and is required for developmental response via transcriptional regulation of target genes ( Dennler et al., 2007; Hui & Angers, 2011; Javelaud et al., 2012). The GLI proteins, including GLI1, are transcriptional mediators of Hedgehog (HH) signaling, and regulate multiple cellular processes such as cell fate determination, tissue patterning, proliferation and transformation, which give this transcription factor a significant role in carcinogenesis if deregulated ( Dennler et al., 2007; Hui & Angers, 2011; Javelaud et al., 2012). GLI1 is expressed in different human malignancies including pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) ( Eberl et al., 2012; Fiaschi et al., 2009; Goel et al., 2013; Hui & Angers, 2011; Mills et al., 2013; Rajurkar et al., 2012; Thayer et al., 2003). In PDAC, GLI1 is prevalently expressed in the stroma, in response to HH ligands secreted by the epithelial cells ( Yauch et al., 2008). However, lower epithelial expression of Gli1 has also been reported, possibly with non-canonical functions ( Nolan-Stevaux et al., 2009).

GLI1 as an Oncogene in PDAC

GLI1 plays a key role in PDAC initiation by modulating the activity of two different cellular compartments, the epithelium and stroma. Rajurkar et al. demonstrated that targeted overexpression of GLI1 in the pancreas epithelium accelerates PDAC initiation by KRAS, a small GTPase mutated in more than 90% of PDAC cases ( Rajurkar et al., 2012). Through use of a mouse model with simultaneous activation of oncogenic KRAS and inhibition of GLI1 in the pancreas epithelium, this group also demonstrated that decreased GLI1 activity reduced the incidence of KRAS-driven PDAC precursor lesions (pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasias or PanINs) and PDAC. Similarly, Mills and colleagues using a mouse model for pancreas-specific oncogenic KRAS expression (KC mice) bred on a Gli1 null background (GKO/KC) defined a key role for GLI1 on PDAC initiation through the modulation of the activity of fibroblasts ( Mills et al., 2013). The KC mice developed PanIN lesions with 100% penetrance and PDAC in advanced age, while the GKO/KC mice did not develop PDAC and had increased survival rate when compared to KC mice. Histopathological analysis of the pancreata showed KC mice developed PanIN lesions and PDAC, while 80% of GKO/KC had normal pancreata.

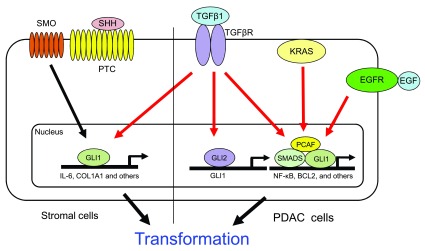

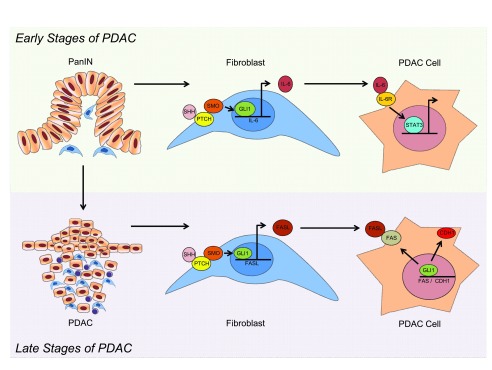

Analysis of the molecular mechanism underlying this phenomenon reveals that GLI1 both regulates different target genes and is modulated by different signaling pathways depending on the cellular compartment. For instance, GLI1 activity is mainly modulated by the canonical HH signaling in fibroblasts ( Figure 1) ( Yauch et al., 2008). This cascade is activated by binding of the ligand to the receptor Patched (Ptch), resulting in activation of the G-coupled receptor, Smoothened (Smo) ( Javelaud et al., 2012; Yauch et al., 2008). Once activated, Smo induces GLI1 activation and upregulation of its target genes ( Hui & Angers, 2011; McMahon et al., 2003). The HH ligand, Sonic Hedgehog (SHH), and components of the HH signaling pathway, including Ptch and Smo, are undetectable in the normal pancreas but overexpressed in PanINs and PDAC ( Thayer et al., 2003). Inhibition of the HH pathway in PDAC cell-based xenograft models through Smo inhibition has been shown to reduce GLI1 activity and tumor growth ( Feldmann et al., 2007; Thayer et al., 2003; Yauch et al., 2008). In addition, genomic sequencing of human pancreatic cancer samples revealed widespread mutations consistent with activation of the Hedgehog signaling pathway ( Jones et al., 2008). While the association between HH activity and pancreatic cancer has been described over a decade ago, there is still uncertainty as to the downstream effect of HH activation in this disease. Mills et al. identified the cytokine IL-6 as a HH/GLI1 target gene in pancreatic fibroblasts ( Mills et al., 2013). Increased IL-6 expression in the stromal compartment induces activation of STAT3 in the neighboring cancer cells, an essential molecular event for the progression of premalignant lesions in PDAC ( Figure 2).

Figure 1. Schematic Representation of Pathways Modulating GLI1-expression/activity in Cancer.

In canonical HH signaling in stromal cells, binding of the SHH ligand to Patched (PTC) activates the Smoothened (SMO) receptor, which induces GLI1 activation of its target genes, including IL-6 and COL1A1 (Martin E Fernandez-Zapico unpublished observation), leading to pre-malignant lesions. SMO-independent mechanisms for regulation of GLI1 in PDAC include KRAS, TGFβ, and EGFR. GLI1 has been shown to regulate the NF-κB pathway in a HH-independent manner downstream of KRAS, leading to pancreatic epithelial transformation. TGFβ promotes GLI2 expression in PDAC through Smad3 and β-catenin/LEF-TCF-dependent upregulation of GLI2 independent of HH signaling. TGFβ induced GLI2 expression, and subsequent GLI1 activation, is associated with EMT, tumor growth, and metastasis. TGFβ can also modulate GLI1 activity by promoting the formation of a transcriptional complex with the TGFβ-regulated transcription factors, SMAD2 and 4, and PCAF, at the BCL2 promoter in cancer cells to regulate TGFβ-induced gene expression. EGFR signaling is aberrantly activated in a majority of PDACs. EGFR and HH have been demonstrated to act synergistically to promote cancer cell initiation and growth by modulation of gene expression of distinct novel pathways through a GLI1-dependent mechanism.

Figure 2. Working Model of the Dual Role of GLI1 at Different Stages of Pancreatic Carcinogenesis.

During the early stages of PDAC, GLI1 is activated in the fibroblasts through canonical HH signaling. GLI1 promotes expression of the cytokine IL-6, which stimulates expression of STAT3 in neighboring cancer cells, promoting the progression of PanIN lesions to PDAC. In the later stages of PDAC, GLI1 binds the FASL promoter and regulates the expression of this ligand in the fibroblast, leading to lower levels of apoptosis in these tumors. In addition, in cancer cells, GLI1 induces the expression of FAS and CDH1 expression, leading to a tumor protective effect.

Hedgehog-Independent Mechanisms for GLI1 Expression in PDAC

While dysregulation of HH-GLI1 signaling has been shown to play an important role in PDAC formation, several studies have demonstrated that GLI1 expression can be activated through HH-independent mechanisms in PDAC, particularly in the epithelial compartment ( Dennler et al., 2007; Eberl et al., 2012; Goel et al., 2013; Ji et al., 2007; Nolan-Stevaux et al., 2009; Nye et al., 2014). Nolan-Stevaux et al. demonstrated that deletion of Smo receptor in pancreatic epithelium had no effect on KRAS induced tumor formation, nor on GLI1 expression in epithelial cells ( Nolan-Stevaux et al., 2009). This indicates a Smo-independent mechanism for GLI1 regulation in PDAC cells downstream of KRAS. In fact, Ji et al. demonstrated that KRAS is a modulator of GLI1 activity and requires the transcription factor for PDAC growth in vitro ( Ji et al., 2007). In the epithelial compartment, GLI1 is regulated in a HH-independent manner, downstream of KRAS. Accordingly, Ji et al., showed that Gli1 protein degradation is blocked in a MAPK-dependent manner. Furthermore, Rajurkar et al. showed a role for GLI1 in the regulation of the NF-κB pathway, a signaling cascade linked to PDAC development ( Algül et al., 2002; Ougolkov et al., 2005; Pan et al., 2008; Wang et al., 1999), downstream of KRAS ( Figure 1) ( Rajurkar et al., 2012). This group has identified the I-kappa-B kinase epsilon (IKBKE)/NF-κB pathway as a direct target of the GLI1 mediating KRAS-dependent pancreatic epithelial transformation in vivo (Junhao Mao, University of Massachusetts and Martin E. Fernandez-Zapico personal communication).

PDAC is characterized by a dense desmoplastic reaction associated with the primary tumor. The abundance of connective tissue is due to an increase in growth factor production in the tumor microenvironment through autocrine and paracrine oncogenic signaling pathways ( Mahadevan & Von Hoff, 2007). Oncogenic KRAS activates SHH production, but HH ligands do not activate the HH pathway in tumor epithelial cells in an autocrine manner ( Lauth et al., 2010; Mills et al., 2013; Yauch et al., 2008). HH signaling in PDAC occurs in a paracrine fashion where HH signaling from PDAC cells to stromal cells has been shown to promote desmoplasia ( Yauch et al., 2008). Lauth et al. demonstrated that this shift from autocrine to paracrine signaling is through activation of the RAS effector dual specificity tyrosine phosphorylated and regulated kinase 1B (DYRK1B) ( Lauth et al., 2010). The authors proposed this is achieved through DYRK1B inhibition of GLI2 function and promotion of the repressor GLI3, and subsequent inhibition of GLI1, in PDAC cells.

TGFβ has been shown to promote GLI1 expression in pancreatic cancer cells ( Nolan-Stevaux et al., 2009). TGFβ induces the expression of GLI1 through Smad3 and β-catenin/LEF-TCF-dependent upregulation of GLI2 independent of HH signaling ( Dennler et al., 2007; Dennler et al., 2009). Nye et al. demonstrated that TGFβ, in addition to controlling GLI1 expression, can also modulate its activity by promoting the formation of a transcriptional complex with the TGFβ-regulated transcription factors, SMAD2 and 4, and the histone acetyltransferase, PCAF, at the BCL2 promoter in cancer cells to regulate TGFβ-induced gene expression ( Figure 1) ( Nye et al., 2014). Activation of TGFβ induced GLI2 expression, and subsequent GLI1 activation, is associated with epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT), tumor growth, and metastasis ( Javelaud et al., 2012).

In addition to TGFβ and KRAS activation, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling, a cascade aberrantly activated in the majority of PDACs, has been demonstrated to play a critical role in HH/GLI1-regulated tumor-initiating pancreatic cancer cells ( Eberl et al., 2012). Eberl and colleagues demonstrated EGFR and HH act together to promote cancer cell proliferation by modulating gene expression through a GLI1-dependent mechanism ( Figure 1). This suggests HH/GLI1 signaling works synergistically through distinct novel pathways during tumor initiation and growth.

Clinical Trials Targeting the Hedgehog/GLI1 axis in PDAC

The concept that HH/GLI1 signaling might be required for PDAC growth, hence a suitable therapeutic target, has been first validated in a genetically engineered mouse model of pancreatic cancer that combines expression of oncogenic Kras with mutation of the tumor suppressor p53, the KPC mouse ( Hingorani et al., 2005). Treatment of KPC mice with a Smo inhibitor in combination with gemcitabine led to a moderate but significant increase in survival ( Feldmann et al., 2008; Olive et al., 2009). A preclinical study of the HH inhibitor, saridegib (IPI-926), co-administered with gemcitabine, produced a transient increase in vascular density, increased chemotherapy drug delivery, and improved disease stabilization in pancreatic cancer cells ( Olive et al., 2009). Based on these results, phase II clinical trials were approved evaluating saridegib and an additional Hh inhibitor, vismodegib (GDC-0449), for treatment of pancreatic cancer. Surprisingly, the clinical trial for both vismodegib and saridegib showed a higher rate of progressive disease when compared to placebo ( Catenacci et al., 2013). Similar findings were seen in a separate phase I trial of vismodegib in 8 patients with pancreatic cancer ( LoRusso et al., 2011). Although hedgehog inhibitors have been successful for treating basal cell carcinoma and medulloblastoma, they do not appear to have the same effect in advanced pancreatic cancer.

These disappointing results left investigators questioning the molecular mechanism responsible for these failed clinical trials. Although there is overwhelming evidence that GLI1 plays an important role in tumor initiation and progression of several kinds of malignancies, these results suggest the transcription factor may have a tumor protective role in the later stages of certain cancers. In fact, recent studies investigating GLI1 expression in PDAC have revealed GLI1 may switch from a tumor promoting to a tumor protective molecule in the later stages of PDAC.

GLI1 as a Tumor Suppressor in PDAC

In contrast to the current paradigm for GLI1 expression and tumor progression, one study found GLI1 expression may actually decrease cell motility in advanced PDAC ( Joost et al., 2012). Joost et al. demonstrated that GLI1 regulates epithelial differentiation through transcriptional activation of the cell adhesion molecule, E-Cadherin (CDH1), in PDAC cells. Lowered expression of GLI1 in PDAC cells lead to a loss of CDH1 expression and promotion of EMT. The transition from epithelial to motile mesenchymal cells is thought to be a critical event for metastasis of carcinomas. Decreased expression of CDH1 is associated with increased metastasis and invasion, while increased expression is associated with lower tumor malignancy ( Seidel et al., 2004; von Burstin et al., 2009). PDAC is strongly associated with early invasion and metastasis. Loss of GLI1 was also shown to decrease expression of additional important epithelial marker genes, including Keratin 19 ( KRT19) and adherens junctions components EVA1 and PTPRM, leading to increased cell motility. This indicates that as PDAC progresses, lower GLI1 levels may actually prime tumor cells towards an EMT program, which would be associated with metastasis and advanced stages of the disease.

Mills et al. examined the role of GLI1 expression in the later stages of PDAC using a mouse model for advanced pancreatic cancer ( Mills et al., 2014). In this study, the loss of GLI1 actually accelerated PDAC progression during the later stages of tumorigenesis. PDAC mice lacking GLI1 showed reduced survival when compared to GLI1 wild type littermates. While both cohorts of mice displayed the common features of advanced PDAC, loss of GLI1 was associated with decreased survival and increased tumor burden. Analysis of the mechanism revealed the pro-apoptotic FAS/FASL axis as a potential mediator for this phenomenon. Loss of GLI1 was associated with a significant decrease in expression of FAS/FASL, leading to lower apoptosis levels and increased tumor progression ( Figure 2).

In agreement with these findings, two recent studies demonstrated that the deletion of the GLI1 inducer SHH, using a mouse model for PDAC, led to more aggressive tumors ( Lee et al., 2014; Rhim et al., 2014). Interestingly, Rhim’s study reported the occurrence of poorly differentiated tumors, with increased vascularity, and significantly reduced stromal content. In contrast, the Lee paper only described a modest reduction in the stromal compartment. The current paradigm for PDAC is that the tumor stroma plays an important role in promotion of neoplastic growth and progression since PDAC is typically associated with a dense desmoplastic reaction. However, the Rhim study shows that tumors with reduced stroma may display a more aggressive behavior than those with an extensive stromal compartment. This concept is further supported by a recent report demonstrating that tumor stroma restrains pancreatic cancer progression and that pharmacological HH pathway activation in stromal cells can actually slow down in vivo tumorigenesis ( Lee et al., 2014). The complexity of these findings reflects our incomplete understanding of the precise biological role of HH/GLI1 signaling in pancreatic cancer. In fact, the level of activation of HH signaling might induce different biological responses during the carcinogenesis process, as commonly observed during embryonic development. Manipulation of the membrane mediators of HH to reduce HH signaling leads to an increase of angiogenesis with low HH levels, but not with complete inhibition. Intriguingly, the Rhim and Lee studies generated a low HH signaling environment by eliminating SHH, but not IHH, another HH ligand expressed in pancreatic cancer. Similarly, studies altering the expression of Gli1 leave intact the other mediators of HH signaling, GLI2 and GLI3 (the latter mainly an inhibitor of HH target genes). It remains to be seen if manipulating GLI1 levels within the epithelial tumor compartment in later stages of disease is of any therapeutic value. Based on work from Fendrich et al. on HH signaling and acinar cell differentiation, it might even be provocatively proclaimed that increasing GLI1 levels could drive terminal differentiation and thus result in lower tumorigenicity ( Fendrich et al., 2008).

Discussion

These studies demonstrating GLI1 may act as a tumor suppressor in the late stage of PDAC give insight into the disappointing results of clinical trials testing HH inhibitors in metastatic PDAC patients. While the Olive experiments reported acute administration of IPI-926 increased survival due to decreased stromal content and increased vascularity, the HH inhibitor performed poorly in pancreatic cancer clinical trials in patients. One explanation for this discrepancy may be the short duration of treatment (3 weeks) in the Olive’s experiments, which may have not accurately detected disease progression following HH inhibition. This indicates that as PDAC progresses, the initial positive effects of HH inhibition may be eliminated as GLI1 levels decrease.

It is unclear why GLI1 levels decrease during PDAC progression in vivo. As previously discussed, one potential mechanism for lowered GLI1 expression in advanced PDAC may be due to activation of the kinase DYRK1B, which inhibits GLI1 expression through expression of the repressor GLI3 ( Lauth et al., 2010). Activation of DYRK1B promotes a shift from autocrine to paracrine signaling in PDAC. This shift may lead to a decrease in GLI1 expression in PDAC cells. In addition, HH signaling promotes GLI1 expression in part through inhibition of GLI1 repressors ( Stecca & Ruiz, 2010). Decreased HH signaling in advanced PDAC may allow for increased expression of GLI1 repressors, such as GLI3 and Suppressor of Fused (Sufu), leading to decreased GLI1 expression and activity ( Stecca & Ruiz, 2010).

An alternative explanation for clinical trial failures of HH inhibitors in treatment of advanced PDAC may be due to GLI-independent effects of SMO inhibition, not necessarily due to a decrease in GLI1. Not all HH signaling responses are mediated by GLI transcription factors. SMO has been demonstrated to play a role in several cellular functions, including actin stress fiber formation, endothelial tubulogenesis, fibroblast migration, and regulation of glucose uptake independent of GLI transcription ( Brennan et al., 2012; Chinchilla et al., 2010; Teperino et al., 2014). The failure of HH inhibition in PDAC could potentially be due to the loss of these GLI-independent SMO downstream effectors, while modulation of GLI1 expression may only be a secondary effect. In Rhim’s study, the authors discovered that SHH and GLI1 deficient tumors were more aggressive, poorly differentiated, and exhibited increased vascularity ( Rhim et al., 2014). This suggests HH/GLI1 pathway inhibition may have a proangiogenic effect. Due to the increase in vascularity of the SHH deficient mice tumors, the authors investigated the effect of angiogenesis inhibition by administering anti-VEGF to tumor-bearing SHH deficient mice. This therapy led to a significant improvement in the overall survival of mice with undifferentiated tumors. Based on this response, the subset of PDAC patients with undifferentiated tumors may benefit from anti-angiogenic therapy.

In summary, due to the high complexity of PDAC initiation and progression, a personalized strategy for treatment should be considered. Under this strategy, PDAC should be analyzed before treatment to determine expression of GLI1 and upstream regulators in order to better define therapeutic options. Further studies are needed to fully understand the role of GLI1 in PDAC carcinogenesis. While there is evidence for a dual role of GLI1 in PDAC, this phenomenon has yet to be linked with other cancer types.

Acknowledgements

We thank Emily Porcher and Pam Becker for secretarial assistance.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant CA136526, Division of Oncology Research (Mayo Clinic), Mayo Clinic Pancreatic SPORE P50 Grant CA102701 and Mayo Clinic Center for Cell Signaling in Gastroenterology Grant P30 DK84567 (to M.E.F.-Z.).

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

[version 2; referees: 3 approved]

References

- Algül H, Adler G, Schmid RM: NF-kappaB/Rel transcriptional pathway: implications in pancreatic cancer. Int J Gastrointest Cancer. 2002;31(1–3):71–78. 10.1385/IJGC:31:1-3:71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan D, Chen X, Cheng L, et al. : Noncanonical Hedgehog signaling. Vitam Horm. 2012;88:55–72. 10.1016/B978-0-12-394622-5.00003-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catenacci D, Bahary N, Nattam SR, et al. : Final Analysis of a phase IB/randomized phase II study of gemcitabine (G) plus placebo (P) or vismodegib (V), a hedgehog (Hh) pathway inhibitor, in patients (pts) with metastatic pancreatic cancer (PC): A University of Chicago phase II consortium study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(suppl; abstr 4012). Reference Source [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinchilla P, Xiao L, Kazanietz MG, et al. : Hedgehog proteins activate pro-angiogenic responses in endothelial cells through non-canonical signaling pathways. Cell Cycle. 2010;9(3):570–579. 10.4161/cc.9.3.10591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennler S, André J, Alexaki I, et al. : Induction of sonic hedgehog mediators by transforming growth factor-beta: Smad3-dependent activation of Gli2 and Gli1 expression in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res. 2007;67(14):6981–6986. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennler S, André J, Verrecchia F, et al. : Cloning of the human GLI2 Promoter: transcriptional activation by transforming growth factor-beta via SMAD3/beta-catenin cooperation. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(46):31523–31531. 10.1074/jbc.M109.059964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberl M, Klingler S, Mangelberger D, et al. : Hedgehog-EGFR cooperation response genes determine the oncogenic phenotype of basal cell carcinoma and tumour-initiating pancreatic cancer cells. EMBO Mol Med. 2012;4(3):218–233. 10.1002/emmm.201100201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldmann G, Dhara S, Fendrich V, et al. : Blockade of hedgehog signaling inhibits pancreatic cancer invasion and metastases: a new paradigm for combination therapy in solid cancers. Cancer Res. 2007;67(5):2187–2196. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldmann G, Habbe N, Dhara S, et al. : Hedgehog inhibition prolongs survival in a genetically engineered mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Gut. 2008;57(10):1420–1430. 10.1136/gut.2007.148189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fendrich V, Esni F, Garay MV, et al. : Hedgehog signaling is required for effective regeneration of exocrine pancreas. Gastroenterology. 2008;135(2):621–631. 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.04.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiaschi M, Rozell B, Bergström A, et al. : Development of mammary tumors by conditional expression of GLI1. Cancer Res. 2009;69(11):4810–4817. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goel HL, Pursell B, Chang C, et al. : GLI1 regulates a novel neuropilin-2/α6β1 integrin based autocrine pathway that contributes to breast cancer initiation. EMBO Mol Med. 2013;5(4):488–508. 10.1002/emmm.201202078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingorani SR, Wang L, Multani AS, et al. : Trp53 R172H and Kras G12D cooperate to promote chromosomal instability and widely metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in mice. Cancer Cell. 2005;7(5):469–83. 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.04.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui CC, Angers S: Gli proteins in development and disease. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2011;27:513–537. 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javelaud D, Pierrat MJ, Mauviel A: Crosstalk between TGF-β and hedgehog signaling in cancer. FEBS Lett. 2012;586(14):2016–2025. 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji Z, Mei FC, Xie J, et al. : Oncogenic KRAS activates hedgehog signaling pathway in pancreatic cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(19):14048–14055. 10.1074/jbc.M611089200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones S, Zhang X, Parsons DW, et al. : Core signaling pathways in human pancreatic cancers revealed by global genomic analyses. Science. 2008;321(5897):1801–6. 10.1126/science.1164368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joost S, Almada LL, Rohnalter V, et al. : GLI1 inhibition promotes epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2012;72(1):88–99. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinzler KW, Bigner SH, Bigner DD, et al. : Identification of an amplified, highly expressed gene in a human glioma. Science. 1987;236(4797):70–73. 10.1126/science.3563490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauth M, Bergström A, Shimokawa T, et al. : DYRK1B-dependent autocrine-to-paracrine shift of Hedgehog signaling by mutant RAS. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17(6):718–725. 10.1038/nsmb.1833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JJ, Perera RM, Wang H, et al. : Stromal response to Hedgehog signaling restrains pancreatic cancer progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(30):E3091–3100. 10.1073/pnas.1411679111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LoRusso PM, Rudin CM, Reddy JC, et al. : Phase I trial of hedgehog pathway inhibitor vismodegib (GDC-0449) in patients with refractory, locally advanced or metastatic solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(8):2502–2511. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahadevan D, Von Hoff DD: Tumor-stroma interactions in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6(4):1186–1197. 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon AP, Ingham PW, Tabin CJ: Developmental roles and clinical significance of hedgehog signaling. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2003;53:1–114. 10.1016/S0070-2153(03)53002-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills LD, Zhang L, Marler R, et al. : Inactivation of the transcription factor GLI1 accelerates pancreatic cancer progression. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(23):16516–25. 10.1074/jbc.M113.539031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills LD, Zhang Y, Marler RJ, et al. : Loss of the transcription factor GLI1 identifies a signaling network in the tumor microenvironment mediating KRAS oncogene-induced transformation. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(17):11786–11794. 10.1074/jbc.M112.438846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan-Stevaux O, Lau J, Truitt ML, et al. : GLI1 is regulated through Smoothened-independent mechanisms in neoplastic pancreatic ducts and mediates PDAC cell survival and transformation. Genes Dev. 2009;23(1):24–36. 10.1101/gad.1753809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nye MD, Almada LL, Fernandez-Barrena MG, et al. : The transcription factor GLI1 interacts with SMAD proteins to modulate transforming growth factor β-induced gene expression in a p300/CREB-binding protein-associated factor (PCAF)-dependent manner. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(22):15495–506. 10.1074/jbc.M113.545194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olive KP, Jacobetz MA, Davidson CJ, et al. : Inhibition of Hedgehog signaling enhances delivery of chemotherapy in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Science. 2009;324(5933):1457–1461. 10.1126/science.1171362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ougolkov AV, Fernandez-Zapico ME, Savoy DN, et al. : Glycogen synthase kinase-3beta participates in nuclear factor kappaB-mediated gene transcription and cell survival in pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65(6):2076–2081. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan X, Arumugam T, Yamamoto T, et al. : Nuclear factor-kappaB p65/relA silencing induces apoptosis and increases gemcitabine effectiveness in a subset of pancreatic cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(24):8143–8151. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajurkar M, De Jesus-Monge WE, Driscoll DR, et al. : The activity of Gli transcription factors is essential for Kras-induced pancreatic tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(17):E1038–1047. 10.1073/pnas.1114168109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhim AD, Oberstein PE, Thomas DH, et al. : Stromal elements act to restrain, rather than support, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2014;25(6):735–747. 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.04.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidel B, Braeg S, Adler G, et al. : E- and N-cadherin differ with respect to their associated p120 ctn isoforms and their ability to suppress invasive growth in pancreatic cancer cells. Oncogene. 2004;23(32):5532–5542. 10.1038/sj.onc.1207718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stecca B, Ruiz I Altaba A: Context-dependent regulation of the GLI code in cancer by HEDGEHOG and non-HEDGEHOG signals. J Mol Cell Biol. 2010;2(2):84–95. 10.1093/jmcb/mjp052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teperino R, Aberger F, Esterbauer H, et al. : Canonical and non-canonical Hedgehog signalling and the control of metabolism. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2014;33:81–92. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thayer SP, di Magliano MP, Heiser PW, et al. : Hedgehog is an early and late mediator of pancreatic cancer tumorigenesis. Nature. 2003;425(6960):851–856. 10.1038/nature02009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Burstin J, Eser S, Paul MC, et al. : E-cadherin regulates metastasis of pancreatic cancer in vivo and is suppressed by a SNAIL/HDAC1/HDAC2 repressor complex. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(1): 361–371, 371.e1–5. 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Abbruzzese JL, Evans DB, et al. : The nuclear factor-kappa B RelA transcription factor is constitutively activated in human pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5(1):119–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yauch RL, Gould SE, Scales SJ, et al. : A paracrine requirement for hedgehog signalling in cancer. Nature. 2008;455(7211):406–410. 10.1038/nature07275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]