Abstract

Background

Since acute care surgery (ACS) was conceptualized a decade ago, the specialty has been adopted widely; however, little is known about the structure and function of ACS teams.

Methods

We conducted 18 open-ended interviews with ACS leaders (representing geographic [New England, Northeast, Mid-Atlantic, South, West, Midwest] and practice [Public/Charity, Community, University] diversity). Two independent reviewers analyzed transcribed interviews using an inductive approach (NVivo qualitative analysis software).

Results

All respondents described ACS as a specialty treating “time-sensitive surgical disease” including trauma, emergency general surgery (EGS), and surgical critical care (SCC); 11 of 18 combined trauma and EGS into a single clinical team; 9 of 18 included elective general surgery. Emergency orthopedics, emergency neurosurgery, and surgical subspecialty triage were rare (1/18 each). Eight of 18 ACS teams had scheduled EGS operating room time. All had a core group of trauma and SCC surgeons; 13 of 18 shared EGS due to volume, human resources, or competition for revenue. Only 12 of 18 had formal signout rounds; only 2 of 18 had prospective EGS data registries. Streamlined access to EGS, evidence-based protocols, and improved education were considered strengths of ACS. ACS was described as the “last great surgical service” reinvigorated to provide “timely,” cost-effective EGS by experts in “resuscitation and critical care” and to attract “young, talented, eager surgeons” to trauma/SCC; however, there was concern that ACS might become the “wastebasket for everything that happens at inconvenient times.”

Conclusion

Despite rapid adoption of ACS, its implementation varies widely. Standardization of scope of practice, continuity of care, and registry development may improve EGS outcomes and allow the specialty to thrive. (Surgery 2014;155:809-25.)

In 2006, the Institute of Medicine described our nation’s emergency system at a “breaking point,” burdened by overcrowded emergency departments (EDs), lack of specialty providers, and uncompen-sated care.1,2 One of the stressors described in the report was care for nontrauma surgical emergencies (NTSE). Although NTSEs include simple, prevalent diseases such as appendicitis, cholecystitis, and superficial abscess, as many as one-third of NTSEs represent complex intra-abdominal processes (33–36%) or necrotizing soft-tissue infections (4–22%) requiring urgent evaluation and intervention.3–7

Americans with these time-sensitive operative diseases typically present to their nearest hospital seeking emergency care. Up to 70% of them require an operation, and nearly half require intensive care.4,8,9 Furthermore, 20–48% undergo operations in the middle of the night.5,8,10 Unfortunately, patients with NTSEs may not always have access to a willing or able general surgeon to provide them timely and appropriate care.1,11–13 Thirty-seven percent of ED directors report inadequate emergency general surgery (EGS) coverage for NTSEs.14

The subspecialty of trauma surgery had largely developed in response to another Institute of Medicine report that described trauma as “the neglected disease of modern society” in 1966.15 In the ensuing decades, injured Americans experienced remarkable decreases in injury-related mortality as a result of trauma specialization and regionalization.1,16,17 However, by the early 2000s, simultaneous achievements in resuscitation, imaging, and prevention had rendered trauma surgery in many US locations a largely nonoperative, critical care specialty.18,19 Acute care surgery (ACS) was proposed as a subspecialty of general surgery in the last decade to both address the need for surgeons willing to take EGS call and to reimagine the profession of trauma and surgical critical care (SCC).18,19

Described as “a new strategy for the general surgery patients left behind,”20 ACS was envisioned to bring together the surgeons, resources, and infrastructure to provide round-the-clock care for NTSEs, much like has been done for the treatment of injuries. On the basis of published reports, many US hospitals have implemented ACS with generally positive results for NTSEs and without adverse outcomes for injured patients.3–10,21–33 However, the structure and process of ACS implementation are not well described in these studies. Therefore, we undertook this qualitative study to better understand how ACS is currently implemented in the United States across hospitals in varied geographic locations and practice settings.

METHODS

We created a semistructured interview using the principle of reflexivity (reflecting upon the effect of clinical experience, literature review, and ongoing research on attitudes and preconceptions to decrease bias in both interviewing and analyses).34 Interview questions explored ACS implementation (eg, infrastructure, team organization, call coverage) and the evolution/future of ACS (see Appendix). The interview was piloted on senior acute care surgeons at centers familiar to the investigator and altered in an iterative fashion.

A purposive sampling method was used to recruit respondents from diverse practice settings (Community, Public/Charity, University) in each of six regions (Mid-Atlantic, Midwest, New England, Northeast, South, and West). Potential respondents, selected from the ranks of national organizations or recommended by colleagues, were contacted by email to participate in a face-to-face interview about their hospital’s ACS program. Strict measures to ensure confidentiality were implemented and described and an agreed-upon date/time for the interview was considered a waiver of written informed consent. This study was deemed exempt by our Institutional Review Board.

Interviews were conducted between June 2011 and December 2011 by the senior investigator (H.P.S.). Fourteen respondents were current section/division chiefs of trauma and/or EGS, two were department chairs, and two were senior surgeons. All represented teaching hospitals, 14 with ACGME surgical critical care fellowships. Seventeen represented level-1 trauma centers. Interview questions were open-ended, and the interviewer asked for further clarification when needed. Interviews lasted between 19 and 84 minutes and were recorded digitally, transcribed, and imported into NVivo 10.0 (QSR International, Melbourne, Australia) for analysis.

Analysts were chosen according to theory of investigator triangulation (researchers from diverse backgrounds analyze the raw data to minimize personal or disciplinary bias of a single researcher).35,36 Two investigators (P.L.P. and C.E.C.) initially independently reviewed each transcript using principles of grounded theory.37 As concepts emerged from the data, specific lines of text were coded to corresponding themes (open coding). The analysts then jointly compared codes, resolved discrepancies, and developed a taxonomy of themes. They used the constant comparative method to compare coded segments, expand on existing concepts, and identify new themes.38 Codes were refined until reaching saturation with a final taxonomy of 50 themes. This final taxonomy was applied to all of the transcripts by the two analysts, after which there was found to be 98% intercoder agreement. The senior investigator (H.P.S.) then reviewed transcripts, and audio if needed, of disputed segments until reaching 100% agreement after which tag clouds, tree mapping and cluster analyses were performed as indicated to explore coded themes.

RESULTS

ACS model

All respondents described ACS as a specialty treating “time sensitive surgical disease,” including trauma, EGS, and SCC. Seventeen embraced the term “acute care surgery,” with 4 referring to “surgical hospitalists” or “in-house general surgeon.” However, one respondent disagreed stating, “we all went into this thing [surgery] ‘like I want to do the hairiest crap you can find me…people bleeding to death and dying and all that.’ I mean it couldn’t be further from this hospitalist word of let me mop up all your little inconveniences around the hospital.” ACS was uniquely described as “boutique…disaster surgery,” “critical care surgery,” “the last great general surgery service,” and “the last stand of real general general [sic] surgeons.” Hospitals with ACS programs were described as a “safety net for the sicker people who are…flunking out of other smaller hospitals,” with five respondents specifying ACS represented an opportunity to “regionalize” care.

Table I shows respondents’ key quotations from their descriptions of ACS. There was agreement that the defining features of ACS are: patients with “physiologic acuity” similar to injured patients (15/18), “round-the-clock” presence (13/18), practitioners who “do not cherry pick” cases (11/18) and “public service” to at risk socioeconomic groups (9/18). Eight respondents expressed concern, however, regarding the specialty’s perceived role as the service picking up “less-desirable” work at “less-desirable” times. Four respondents noted that there is “no one-size-fits-all” model for ACS. Figure 1 is a word-frequency query of respondents’ descriptions of ACS.

Table I.

Descriptions of the ACS model from 18 key informants*

| Coded theme | Representative quotations |

|---|---|

| Round-the-clock availability | “We went in-house 24/7. And, I would submit to you that one of the markers of an acute care surgery service is in-house attending coverage.” |

| “Because until now, nobody can answer the question from me of why the biology of disease at two am is different from the biology of disease at two pm? And so our mantra is we provide the same quality of care at two am as we provide at two pm.” | |

| “We take all comers, we take them at all times, and they all get cared for quickly.” | |

| “You have to say you know what? I am as good as the colon guys if there is a perforation in colonoscopy. But I am ready to go because me and my guys are here and we can operate on him in 1 or 2 hours and not have to wait 6 hours until this colon surgeon finishes his or her clinic or disrupts the clinic.” | |

| Acuity similar to trauma | “I am a disaster surgeon. Because it does not matter where it comes from, I take care of the sickest patients….The patient is either broken badly — whether their colon has exploded or they are shot to pieces—or the situation is very disastrous or it is an emergency or something.” |

| “Our experience in critical care derives dramatically from our ability to care for really sick surgical patients. And that, see there are many innovations in trauma care that translate into very effective general surgery techniques under emergency conditions, for instance, the acute abdomen damage control” | |

| “The surgical emergencies like trauma tend to be those in which you do not have previous knowledge of a patient, they show up and you are dealing with them as best you can for the situation. So I think a lot of the emergency surgery principles really blend into trauma.” | |

| “Trauma surgeons somewhat naturally adopted acute care surgery since we are already in-house, we are already caring for the sick patients, and we have the critical care background.” | |

| Yes to all cases | “So we made it a service that. said no case too small, no hour too late.” “If you say I am here, I want it all, I will take it, I will do what you think and earn it, you are not going to be [relegating to being] a pus surgeon.” |

| “We pretty much take everything …it’s kind of the last great general surgery service.” | |

| “I said okay, I will do that. I will do anything you have…But it takes a little bit of effort to do that because you have got to say yes all the time.” | |

| Public service | “And when the uncompensated care is factored in, we just take everything, we don’t care, we don’t look, we just. whatever your insurance or lack of it is, we just. you come on to the service. And that’s one of the things I like about the service. It’s a very egalitarian service.” |

| “I like working with underserved populations and feeling like, .[I] sort of took a crack at whatever the worst things going on in society like violent crime or healthcare or whatever…. To actually have a job where you help sick, poor people. It’s nice.’ ‘ | |

| “People who go into this specialty are more altruistic than other physicians. I just am. And I get a great amount of satisfaction out of the fact that I do not have to be paid by the patient to take care of him and deliver really good care.” | |

| “This institution provides a huge amount of urgent emergent care because of the nature of the patient population that seeks a lot of their care urgently…it’s just that’s the nature of poverty in America and okay so what should we do so that – and that [ACS] helps us do a better job.” | |

| Service for all things less desirable | “But it’s hard sometimes—it sometimes just seems that we’re making the fancy elective surgeons happy.” |

| “…but the colorectal surgeon might turn to you and say ‘well, I do not need to see every…butt pus.’ I am like ‘Well, wait a minute. I cannot do the perforation diverticulum, but I can do butt pus?’ …this sort of call just is not appealing to any of them, you know what I mean?” | |

| “Some of it by default because nobody else wanted it. And so that is why I am struggling with defining it, because you hate to define something by exception… [but] a lot of what we do ends up being defined by what other people don’t do.” | |

| “Because by our schedule of having somebody here twenty-four seven it becomes very tempting to have us be a wastebasket for everything that happens at inconvenient times.” | |

| No one-size fits all | “So I think what you need to do is embrace the concept of trauma, emergency surgery, critical care, be flexible with how you define emergency surgery” |

| “I mean, one size does not fit all. We have got to recognize that. We have got to figure out. And to a certain extent, various institutions may or may not be able to embrace the model.” | |

| “We are taking what we have and we are reengineering it to the frequently locally defined set of pathologies that we are dealing with.” | |

| “Environment and the needs of your patient based on the local rules are what define what you do as an emergency surgeon” |

One respondent each representing geographic (New England, Northeast, Mid-Atlantic, South, West, Midwest) and practice (Public/Charity, Community, University) diversity among acute care surgery programs. ACS, Acute care surgery.

Fig 1.

Word-frequency query of respondents’ descriptions of ACS.

ACS program structure

Represented institutions had had an ACS program from <1 to 27 years of (mean 5.7 years [SD 6.2]; median 3.5 [interquartile range, IQR 2–7]). Six respondents answered they had “always” had an ACS program but the “label” was only recently attached. Programs had 4 to 9 core attending surgeons (mean of 6.8 [SD 1.5]; median of 7 [IQR 6–8]). Double board certification in general surgery and SCC was required of core surgeons with rare exceptions (age, foreign training). One program had core physiatry and psychiatry faculty.

All programs covered critical care separately from trauma and EGS. The majority (16/18) shared SCC coverage with nonsurgeon intensivists; however, one program’s core surgeons did not provide any critical care whereas another’s provided all of the SCC in the hospital. At 15 programs the in-house trauma surgeon would manage intensive care unit (ICU) patients overnight, if needed. However, one hospital had an in-house ICU attending, and another had an eICU to ensure round-the-clock SCC coverage.

For daytime care, 10 programs combined trauma and EGS into a single clinical team. The impetus for combination was “efficiencies of scale” (7/10) and “quality assurance” (6/10). Of combined teams, seven had two separate day attendings, one for rounding and another for new trauma/EGS activations/consults. One program had second attending from 7 am-noon to cover clinics and cases in addition to the attending assigned from 7 am to 7 pm. One combined program had four attendings on-service at any given time to cover patients based location (clinic, ward, stepdown, ICU) with the stepdown attending responding to any new trauma/EGS activations/consults. One respondent commented that a combined team “is so awkward that I have had to work very hard to rebrand our service so that when a patient who has had their gallbladder removed is referred to clinic, they don’t show up at a ‘trauma clinic,’ which obviously confuses everybody…I have had to get the residents to stop responding on the phone…by saying ‘trauma’ when somebody is calling for a Crohn’s consult or an OB-GYN is calling for assistance in the operating room…I have had to change the nomenclature for the operating room posting schedule.”

Meanwhile, eight programs maintained separate clinical teams for daytime care of injured patients and NTSE patients. The rationale for separation was “burdensome patient volume” (5/8) and “quality assurance” (1/8). One program with separate teams had a designated daily “officer in charge,” who was empowered to direct anyone from any team to assist in the care of injured or NTSE patients, even though the day-to-day patient care was separate.

Whether combined or separate, 10 programs used an on-service model for daytime care 5–7 consecutive days, whereas eight programs had a shift model with 12-, 16-, or 24-hour shifts. Fourteen (of 17) programs provided all the night/weekend coverage of all trauma through their core group of surgeons, which was in-house coverage for all but one program. However, 13 of 18 shared night/weekend EGS coverage due to “volume/manpower imbalance” (5/13) or “competition for EGS call” from other general surgeons (8/13). Thirteen programs had in-house EGS coverage, but four programs reverted back to the home call model when a noncore surgeon was covering EGS. The monthly night/weekend call burden for core surgeons was 2–7 days (mean 4.7 days [SD 1.3]; median 4.5 days [IQR 4–5]). One program had a single attending covering Saturday/Sunday all year except for a month long vacation. Another had an attending night float Sunday-Thursday.

Regarding clinical scope beyond trauma, EGS, and SCC, nine programs included elective general surgery. However, although two respondents stated that their program emphasized elective general surgery, five respondents clearly stated that this was not a major focus of their practice. One program uniquely had a single attending among the core surgeons taking responsibility for all the elective volume of the core surgeons. A few respondents specified emergency orthopedics and neurosurgery (1/18), ED triage for all surgical divisions (described as “first-call work-up”; 1/18), endoscopy (1/18), complex abdominal wall repair (1/18) and nutrition service (1/18), difficult airway service (2/18), and feeding tube and tracheostomy service (2/18) as part of their program’s clinical scope.

Whether combined or separate, only two programs provided follow-up through the admitting attending whereas all other programs used a group model where the attending of the day/week provided follow-up. For clinical problems requiring highly specialized surgical approaches or coordinated long-term follow-up, nine programs routinely referred to subspecialists for assistance in the operating room or postoperatively. Regarding this philosophy of appropriate referral one respondent stated “the environment of the Acute Care practice…is never be ashamed to call an expert.” Another stated “You have got to recognize and be comfortable that you are the master of emergency. But 5%, 10% of that, you just have to have colleagues that will come help you.”

Respondents estimated that 0–33% of their EGS volume was referred from outlying hospitals (mean 14.8 % [SD 10.8]; median 16.3% [1–20]). Eight programs had a “just say yes” or “green light” policy on accepting transfers, and seven programs undertook community outreach to build their referral base. However, one respondent stated, “Sometimes we are a little bit frustrated with because we feel that those institutions do have board certified surgeons, but just refuse to take care of, for example, necrotizing fasciitis.” Although all respondents who represented a trauma center could estimate either their total annual trauma activations, only two could estimate their EGS volume. Said one respondent, “And, interestingly I know nothing about our emergency general surgery volumes.”

Nine programs (of 17) had a trauma crash room available 24/7 that was not typically used for EGS; one program did not have a designated trauma room. Seven programs had elective surgery block time ranging from 1–2 to 3 days/week that could be booked a day or more in advance. Eight programs had some “block” time for EGS cases, ranging from rooms set aside daily for half a day to a full day (eg, 7 am to 5 pm; 7/8) to a 24/7 dedicated EGS room (separate from a trauma crash room; 1/8) that could be booked in real time such that the acute care surgeon would be responsible for flow of cases through the room.

Twelve programs conducted formal daily signout rounds for patient handoffs. Only six included attending surgeons, and three included physician extenders or others such as bedside nurses, case managers, and physical therapists. All included residents. Signout rounds were described as the “safest way to ensure a clean hand-off” and as opportunities for “ensuring continuity” (9/12), “performance improvement” (4/12), and “resident education” (2/12).

Two programs were collecting prospective data on NTSE patients with another about to launch. Thirteen respondents agreed that they “really should be” maintaining a prospective EGS registry. Ten programs were trying to cover this gap by informally tracking data using existing quality improvement databases, case logs, and billing data. Respondents agreed that such registries would be imperative for performance improvement initiatives such as “comparing our outcomes to their [non-core general surgeons who cover EGS] outcomes” and “benchmarking for emergency surgery…like what the benchmarks are for an acute appendicitis or acute perforated [viscus]” One respondent stated, “In order to run a service right, you got to supervise the service. You got to fix what’s broke and do what you’ve been doing well, better. So the primary goal of prospective data collection is to look at our complication rates, to look at our hospital stay, our time from admission to the OR, our time from OR to home, ICU length of stay and these are all sort of things that you do perfunctorily on the trauma registry.”

Benefits

Table II shows respondents’ key quotations about the benefits of ACS. Fifteen commented that ACS “freed up elective surgeons.” Among core surgeons, respondents cited “job satisfaction” due to both camaraderie and increased operative volume (9/18) and better “lifestyle” (5/18) as key benefits. However, one respondent criticized lifestyle benefits as a rationale for ACS stating, “Acute Care Surgery can be practiced with the same practice pattern mentality of the surgeon–as any subspecialty, instead of fragmentation of care by involvement of multiple caregivers…It should not follow the model of Trauma Care. Instead it should follow a more concrete continuity of care, one surgeon based model like any other subspecialty…We are not doing this for our life style I hope.” Six respondents reported “increased revenue” streams both by allowing elective surgeons to mature their practices and increasing collections for EGS. Meanwhile, 12 noted that their programs enhanced “resident education” by fostering more “independent surgeons” (3/12), improving “critical care education” (4/12), and increasing “interest ACS” careers (3/12).

Table II.

Benefits of the ACS model from 18 key informants*

| Coded theme | Representative quotations |

|---|---|

| Frees up elective surgeons | “It [ACS] actually will relieve people, most of the surgeons of what they think is a very onerous duty, and that is emergency surgery, period. It gives us a lot of credence.” |

| “[ACS] allowed other subspecialty surgeons to pursue their practice without the burden and the urgency of having to deal with acute surgical problems. It’s a major, major impact in the department. In fact, it probably increased the productivity of other surgeons that way.” | |

| “It has allowed our elective general surgery surgeons to really focus on what they really want to do. there’s no chance when they have their elective day that they’re going to have to run down and do something.” | |

| “I think the biggest benefit…the surgeons in general that used to have to cover Emergency Surgery, they never want to be part of it again. And because they find it is totally disruptive and their RVUs are up, their office hour visits are up, and their operations are up. They love it.” | |

| Job satisfaction | “I think it keeps the staff busy, they’re doing what they like to do, they’re getting into the operating room a lot; it keeps them on their toes, it keeps them happy.” |

| “[My faculty are] now operating all the time every day as opposed to whenever they might be able to operate. So their level of satisfaction has gone up. So I think in terms of the distribution of work, faculty satisfaction it’s been a tremendous benefit to the department.” | |

| “In terms of professional development, it gives likeminded people that want to practice in one particular area the opportunity to grow with each other, collaborate both clinically and scientifically.” | |

| “We all have the same interest, which is trauma, which is emergency surgery, ICU and research and education. I think that is key. I think we all work well together, so we sign-out well, we are always there to cover each other, so there is always…you always have someone to help out if there is any problems. I think that is great.” | |

| Lifestyle | “And I think for us as a group it is beneficial because you have one person who is rounding on the service who is taking care, who has a responsibility at the service, so that sort of off-loads you for whether you are doing research or whether you have the weekend off, so I think that is extremely beneficial for the group.” |

| “We’ve been able to demonstrate that we’ve kind of taken the lifestyle problems out of it because it’s more shift work and that you don’t have to be in the hospital 24/7 to do this kind of work.” | |

| “This [ACS] is something that…worked very well for family life and it helps us address the lifestyle thing. And so basically, if you are on-call at night during the week, you have 8 hours of pre-call at home.” | |

| “Probably where we concert most of our effort in trying to provide a good job that has a reasonable lifestyle. And it is abnormal to work at night and on weekends and nobody wants to do it. So in order to provide some lifestyle, we try to be efficient with our all coverage. So that allows us fewer people in the hospital at night and on the weekends.” | |

| Increase revenue | “An acute care surgery model…can be a very, very lucrative proposition. Because remember, you cannot hire that many faculty usually based on collections for acute care. And so if you have come up with some model or another that allows you to bring in more faculty and do more coverage, the department benefits greatly. The elective surgeons get more elective work done. This mass of other acute care surgeons we brought in helps a lot because eventually it generates enough business.” |

| “And, because the in-house guys are currently in-house, they capture a lot more charges…my other divisions didn’t go bankrupt, their actual volumes went up. So and the department benefits have been really, really good.” | |

| “I think the hospital likes us to get the business because I think that they get a bigger bite out of it because we’re already on salary so they just give us a little piece, a little incentive piece out of a gallbladder rather than John Q private surgeon taking all of the collections for that. So I think that there’s more profit in it for the hospital or more revenue at least when we do it. So they encourage the business.” | |

| “We are helping the department by helping the elective faculty and bringing in some additional revenue that was totally unrealized.” | |

| Resident education | “The breadth of the cases that we see is also a bonus, I think. So a very good educational experience for the residents and fellows just because it is a busy county hospital. That is what I would say.” |

| “I think…it’s a lot better for residents to have a group of people practicing emergency general surgery in sort of an organized, perhaps an evidence-based, way rather than just kind of being a scattered individual practice that they’re exposed to. So I think that the opportunity for us to treat EGS the same way we treat trauma in certain terms of having protocols and presenting papers on rounds and having an organized team is where a lot of things come through.” | |

| “I think that is really important for resident education… It is not that we do things better, I think it is that if you have a team approach with multi-disciplinary rounds…it benefits the resident education and it benefits us.” | |

| “The other thing I think from a residential standpoint is kind of beneficial because then you have all these emergencies on one service so when they are on that service they kind of get a more concentrated education on acute care surgery.” | |

| Interest in ACS | “[ACS serves as a] model for surgical trainees how to pursue a career in General Surgery and made General Surgical training a very attractive and viable option to our surgical trainees at the time of fragmentation and disintegration of their surgical training.” |

| “These [emergencies] were always cases we thought to be kind of the dregs of given the choice you want to an incarcerated hernia or do you want to a Whipple? Residents being residents they’re always going to choose the Whipple, but I think we’ve been able to show the residents that this [ACS] is really interesting stuff and this is a very interesting kind of career to have…” | |

| “I think one of the major ones, and I think is the exposure that the residents have to what acute care surgery can be or is evolving to be.” | |

| “I can say that that has opened the eyes of a number of our residents as to this is a potential career for us in the future, this is something that I would like to do as opposed to it used to be this is all private general surgeons and this is how it is.” | |

| Critical care education | “I think what disappoints me about the residents that I see here is that there is a lot of emphasis on doing complicated operations, but not as much on the ICU, the pre-op and the post-op management. I think one of the strengths of the ACS service is we have become the teaching service for the residents.” |

| “So we took, in order to skim the educational cream off the top, we pushed the residents way up to the front, resuscitation, operation, critical care, and step-down. That’s what they do.” | |

| “I think that we probably teach them more about the pre and post-operative and critical care then what they will find on other services…. We get our share of the disasters.” | |

| “I think having that comfort to be able to take care of critically ill patients that we have, being able to know when to operate in an emergency… I can say, over the last couple of years, that the residents that come out of our program do have a better idea.” | |

| Technical independence | “There is only so much you can learn actually just watching a case. There has to come a point in time where you are actually doing the case. I think that is one of the things that residents like about our service, they get to do a lot to the level that they are appropriate for their training.” |

| “Because our chiefs…They really needed more in terms of independent decision making and operating around even though we’re in every case…it really does give them a concentrated experience in emergency general surgery.” | |

| “I would tell you that, unfortunately, no matter where you go, most chief residents are not operating with the autonomy that they used to. So our graduating residents are either going to have to be stumbling around for the first two years or they are going to need some fellowship where they get that extra autonomy. It is one of the reasons why focus on keeping that year as close to the ACS here as possible.” | |

| “I think one of the strengths of the ACS service is we have become the teaching service for the residents. They get a lot more hands on operative experience with us. If somebody is doing a robotic whipple, that is not an intern case and it is not even a PGY-5 case.” | |

| Quality | “I think that is really important…. for care of the patients. It is not that we do things better, I think it is that if you have a team approach with multi-disciplinary rounds it benefits the patient.” |

| “I think that the idea of having an attending see a patient quickly rather than relying on over the phone judgment as to whether they should come in, I think that has to eventually amount to some benefit….in terms of responsiveness quality, up-to-dateness, evidence-base of care, and all that.” | |

| “When you have attendings that are…really directing the most important either definitive diagnostic study or definitive surgical procedure that needs to be done as opposed to a resident trying to figure it out in the middle of the night dead tired and stuff, I think it has actually affected the quality and the safety of the patients in the institution.” | |

| “The ability to function as a group…allows you to maintain the same level of competency and quality, night and day, in every setting” | |

| Expedites care | “Another huge advantage to the hospital is we have changed the landscape of the operating room. By doing the cases as they come in, we no longer load up the OR schedule the next day…OR efficiency improves” |

| “I think you having someone who is in-house who is taking care of emergency surgery problems, so there is really for the most part no delays in terms of seeing the patient, there is no delays in terms of getting therapy for the patient, there is no delays in taking them to the operating room and I think that is clear.” | |

| “It is extremely rare for us to see somebody in off hours and have to have them on a wait list to go to the operating room. Because we do it when we need to or we stage it so we take care of the emergency and then we bring them back for more definitive surgery…. It is also very rare for us to have a surgical problem in the emergency department waiting. We just do not do that. The reason is because attendings, like in trauma, are making the decisions within minutes of getting the consult with the residents.” | |

| Critical care expertise | “Well, I think when you have people who are more focused on one sort of physiology that they can do a better job….all general surgeons can do general surgery. So they can all take out gallbladders and do bowel obstructions but if you prefer a focus on the resuscitation of that particular patient who’s really sick then you have ICU and surgical ICU expertise, that makes it—that—those things are symbiotic so people do better.” |

| “I got a bunch of really, really sharp cookies. [who] like to operate and…know that they’re general surgeons first. Equate that to somebody who can take care of a really sick ICU patient and a trauma patient and a general surgery patient because they’re always working.” | |

| “For the average patient showing up having a—you basically have access to two surgeons—you have access to a nontrauma surgeon, but now they are like with a team that includes an intensivist and a second brain as well. So you effectively get access to two surgeons.” | |

| “By having everybody Boarded in Trauma Critical Care, the idea is that sickest of the sick patients are coming in for emergency surgery will have a surgical intensivist as part of their care.” | |

| Evidence-based standards | “It [ACS] puts the patients together and it gives you an opportunity to look at various things on patients that are on an individual service cared for by pretty much a homogenous team of faculty and with a pretty consistent management strategies and so on.” |

| “We follow schedule protocols on how we are going to take care of things. So things should not be different from that standpoint. So hopefully, patient satisfaction, patient outcomes, length of stay will actually improve.” | |

| “I think that as a group, it has forced us to kind of sit down and look at an evidence-based medicine as to what are the good protocols that we can put together for that patient that has the perforated ulcer, the diverticulitis….” | |

| “It’s uncommon in most places to have there be a thriving evidence-based bickering about what to do about bowel obstructions. It’s been kind of a forgotten—all this incredibly common stuff has always been the stuff that’s most, I think, kind of sloppily dealt with or just by whatever tradition is. So I think it’s good to have the rigor of trauma saddled to emergency general surgery. I think it’s helpful for the practice of emergency general surgery.” | |

| Research | “The other strength that we have is we have got excellent research energy and interest. That is a super important part of our mission here in this institution.” |

| “Because any of these people [acute care surgeons] could get a grant and do a project and go out and drum up business.” | |

| “And there are always advantages for research because it does, it puts the patients together and it gives you an opportunity to look at various things on patients that are on an individual service cared for by pretty much a homogenous team of faculty and with a pretty consistent management strategies and so on.” | |

| “Again, and we have a number of resources available as critical care doctors for professional development and scientific investigation, including a core group of statisticians that works with our critical care group on a number of projects for clinical and scientific research.” | |

| Stand-by help | “The institution, we bring them so much standby help it is not even funny.” |

| “We are critical care-trained, we are available for this stuff. I get called for ridiculous things all over this hospital and stuff like that. We bring that standby. We are the face to the community for a lot of the stuff that goes on and there is a lot of tragedy” | |

| “And that is kind of how our hospital views us. By being 24/7, in-house, we guarantee them that there is a competent surgeon with a sharp knife, and a willing attitude.” | |

| “I think the benefit of the community is having the trauma center and I think that extends, you could argue that having that person in-house giving you that kind of safety net where that surgeon is always in-house available” | |

| Emergency department satisfaction | “It gets the patient out of the emergency department and admitted and worked up by someone that is in-house. So the emergency department is happy with that.” |

| “What the emergency docs will tell you is, man, I’m so glad you guys are covered down here. We’re there …. They call a trauma doc, they’re going to get somebody right away to see an appendix.” | |

| “It is a very busy emergency department, not just for sheer numbers but the acuity down there is just unbelievable. So that is very good. They love the Emergency Surgical service. I mean, they love it.” | |

| “The emergency department loves us. The reason they love us is because if we group all of the emergency general surgery up to one group, they see us all the time because we are here for traumas. They do not know any of the general surgeons.” | |

| Hospital reputation | “It doesn’t do bad for the institution to have a reputation that we take all comers, we take them at all times and they all get cared for quickly.” |

| “The institution as we grow is marketing us to the other community hospitals in ____, some of which have had trouble having general surgery coverage at night. We are becoming the feeder system for the gall bladders, the appendixes, the bowel obstructions that come in at night and those patients are coming in here, getting faster care, and better care.” | |

| “From the community point of view, let me tell you, the people in ____ know that we have an Emergency Surgical service because they do not go to the other institutions. For the outlying hospitals, meaning those in ____ and those in the fringe counties, they all know it is here. It is becoming one of the high referral services, just like Trauma used to be.” | |

| “we are hoping that they [outlying hospitals] will now see us a general surgical team to have referrals to” | |

| Access to emergency general surgery care | “But I do think that the fact that that surgeon being in-house and that institution being required to have the capability to operate and image and evaluate and get a patient to the ICU 24 hours a day seven days a week is a huge benefit to the community.” |

| “If you have a bad surgical problem, there’s a surgeon here waiting for you, you know. I think it’s about access and provides better access to emergency surgical care.” | |

| “I think the benefit of the community is having the trauma center and I think that extends, you could argue that having that person in-house giving you that kind of safety net where that surgeon is always in-house available, certainly benefits the community.” | |

| “I think for the community, I think you having someone who is in-house who is taking care of emergency surgery problems, so there is really for the most part no delays in terms of seeing the patient, there is no delays in terms of getting therapy for the patient, there is no delays in taking them to the operating room and I think that is clear.” | |

| Expedited referrals | “Provided surgeons in the community with an outlet and the resource for their complicated patients either preoperative or intraoperative or actually even more importantly postoperatively complicated patients. For immediate transfer without any difficulty and we provide continuity with care” |

| “Well, for the broader community you’ve got one number to call if you got a surgical emergency. It certainly streamlines the referral sources and gives us an easy way for people to contact us ‘cause we do a fair amount of community outreach.” | |

| “And so for the community they don’t have to wait for 6 hours until their surgeon gets out of the operating room for somebody to come and see them for an acute surgical emergency. So the community knows that we’re here and they know that they’re going to be seen in a timely manner.” |

One respondent each representing geographic (New England, Northeast, Mid-Atlantic, South, West, Midwest) and practice (Public/Charity, Community, University) diversity among acute care surgery programs. ACS, Acute care surgery; ICU, intensive care unit; OR, operating room.

All respondents noted that their programs improved “quality of care” by “expediting care” (17/18), leveraging “critical care expertise” (12/18), and “standardizing practice” (8/18). They also mentioned “satisfaction among ED colleagues” (7/18), “research” to drive evidence-based ACS practices (5/18), and “stand-by help” hospital-wide (3/18) as benefits of their programs. Fifteen respondents noted that “hospital reputation” improved in particular because their program improved “access to EGS care” (12/15) and “expedited referral” processes (6/15).

Challenges

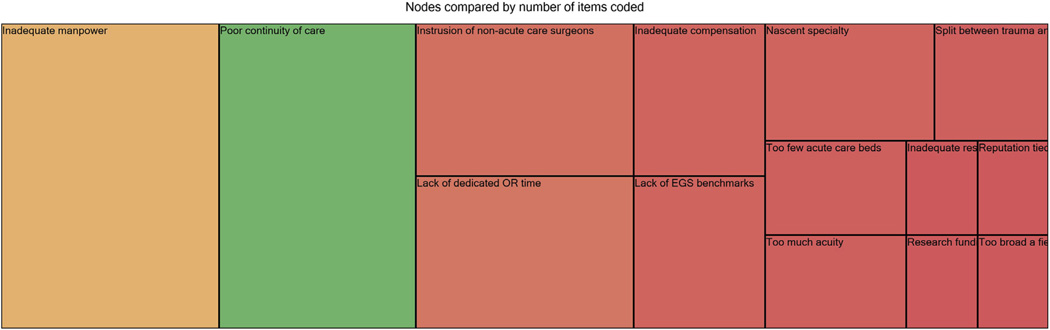

Figure 2 represents tree map coding for ACS challenges. When discussing the challenges (quotations shown in Table III) facing their programs, respondents exhibited more varied responses. Many cited “lack of manpower” (10/18) and “poor continuity” (9/18), fewer cited “lack of dedicated OR time” (5/18) and “intrusion of non-acute care surgeons” (5/18). However, three or fewer noted “lack of EGS benchmarks” (3/18), need to evolve a “nascent program” (3/18), “inadequate compensation” (3/18), “dividing care” of trauma and EGS patients (2/18), “too few acute care beds” (2/18), “too much acuity” (2/18), “inadequate resident support” (1/18), “group reputation” tied to individual surgeon behaviors (1/18), “lack of research funding” (1/18), and “too broad a clinical scope” (1/18) as challenges.

Fig 2.

Tree map coding for ACS challenges.

Table III.

Challenges of the ACS model from 18 key informants*

| Coded theme | Representative quotations |

|---|---|

| Not enough manpower | “I think the weakness is manpower. There’s just not enough of us and that’s an old story—I don’t know that there’s an institution in this country that has enough people, which is probably why well trained trauma surgeons can pick their jobs.” |

| “The problem is just it’s the staffing. You know it’s continuing to find people that are willing to do it and want to do it that can be compensated appropriately, and enough people to take calls so the call is not burdensome or excessively burdensome.” | |

| “We’re still running a traditional service where you’re trolling around— making rounds of fifty patients. You can’t really bond with them as much as you might like to. And, if the family’s not in the room when you go by it’s kind of not happening that day.” | |

| Poor continuity | “The weakness number one is I would say continuity of care…people and physicians, and referring physicians expectations that we have one surgeon, “I know my doctor, I know my surgeon. I am going to see this surgeon, preoperatively. He’ll do my operation and I’ll see him postop. We have to live up to this and we don’t.” |

| “I think that the downside of our practice pattern is the continuity at the attending level, which is, I think, a huge discussion nationally and a real ongoing challenge I think.” | |

| “I think the weaknesses don’t have the same degree of continuity of care as kind of the older system of care.” | |

| “If you are reinventing the wheel every day on rounds, things get lost.” | |

| Lack of OR availability | “I hope eventually we can get ourselves a real dedicated operating room so these things can move ahead more expeditiously—I think if someone comes in with an appendicitis and they have to wait 24 hours before it’s taken care I’m sure we don’t look too good…” |

| “What we don’t have is… one of the things we’ve talked about is we’d like to have a room to do add-ons.” | |

| “Our main problem, the gigantic problem is operating room time. We are fighting and struggling and have been for years. To have dedicated operating room time similar to trauma dedicated room times.” “It would be better—nice to have a little more access to the operating room” | |

| Intrusion of nonacute care surgeons | “Trust is difficult sometimes. It is not helped by a guy who thinks that being called for an emergency problem in the middle of the night is onerous and not what they like to do. I do not paint the other attendings as being evil. I just, again, people can tell when you do not embrace the problem or the situation. There is just no other way around it.” |

| “I think that we still struggle a little bit with the pluralistic model of private practice and full-time.” | |

| “The private surgeons still—for the most part—see us as the enemy. There is definitely, there was always that riff as oh, those are the employed surgeons and now those are those employed surgeons who do acute care surgery” | |

| “There are still some general surgeons who cover some, which is my other advice, is you would have to get rid of all those people on the call pool and make it the trauma critical care guys covering all that, that is my advice.” |

One respondent each representing geographic (New England, Northeast, Mid-Atlantic, South, West, Midwest) and practice (Public/Charity, Community, University) diversity among acute care surgery programs. OR, Operating room.

DISCUSSION

ACS has been theorized to improve productivity in an overburdened health care system, optimize outcomes, and increase the cost-effectiveness of EGS coverage.5–7,23–33,39–43 Our qualitative results from stakeholders at 18 hospitals with ACS programs show marked variability in the current implementation of ACS and suggest that, nearly a decade after the specialty first emerged, barriers may exist to realizing its benefits.

Greater quality care was resoundingly embraced by respondents as a benefit of ACS. Although programs were expediting care, leveraging critical care expertise, and establishing EGS protocols, lack of continuity was a persistent threat to quality across many programs. Despite the fact the rigorous face-to-face handoffs increasingly are recognized as crucial for continuity of care,44–50 only one-third of our respondents had formal face-to-face attending level handoff. Implementation of standardized handoff protocols and incentivizing attending presence may improve quality in ACS programs as has been demonstrated in the medical and critical care literature.46,51 In addition, various attending surgeons executing follow-up instead of single surgeon, was considered a significant threat to continuity. Since the model of a single surgeon following his/her patients appears incompatible with the ACS model of having surgeons function in multiple roles, programs may benefit from better surgeon-to-surgeon communication or having a single surgeon as the face of the program’s outpatient clinic as one of our respondent’s programs did.

Real-time evaluation of patient care data is paramount to continuous quality improvement and is mandated for trauma centers.52 Although the feasibility of extending this concept to EGS has been demonstrated,53 only two respondents’ programs had implemented prospective data collection despite nearly uniform agreement on its importance. Lack of resources was the main barrier to data collection. Currently, hospitals have no systems-based requirements to support such registries, even though they may ultimately result in quality improvement and cost-savings. Our results suggest that ACS programs are doing the best performance evaluation they can through available resources such a billing data or by creating less comprehensive databases. A few respondents noted that ACS lends itself to regionalization of care. Efforts at regionalization, if they come to fruition, may serve as an impetus for more rigorous, comprehensive data collection for NTSEs.

Our respondents also reported improved access to EGS and better relationships with ED physicians as ways their programs enhanced quality. More expeditious treatment of NTSEs, whether it be response to the ED or time to OR, has been reported as a benefit of ACS by others.6,7,24,27,30,32,43,54 However, lack of blocked OR time for EGS add-ons remained a significant stressor delaying care at many of our respondents’ hospitals. Furthermore, although most respondents agreed that in-house attending staff were integral to expediting care, nearly a third of our respondents others lamented lack of manpower to sustain round-the-clock coverage. Thus, although ACS has been proposed as a model to make up for the anticipated national shortage of 1,875 general surgeons in 2020 and 6,000 general surgeons in 2050, our findings suggest that the ACS workforce is suffering perhaps due to some of the same reasons as the general surgery workforce crisis, in particular the requirement for in-house call and 365 day a year coverage.55–59 Some respondents’ comments that their program is increasingly encouraging their trainees to consider such careers may ultimately ameliorate this workforce issue.

ACS programs have been reported to both increase departmental revenues and reduce hospital costs.6,29,43 Although we did not analyze financial data, our respondents largely agreed. Although there was some tension regarding disenfranchising general surgeons from their traditional role as providers for EGS call from home, freeing up elective general surgeons was a major theme among our respondents. Elective surgeons are then presumably able to develop and sustain revenue streams while acute care surgeons can increase their surgical billing as well. Furthermore, our results suggest that a formalized approach to EGS coverage appears to increase the potential of the hospital to serve as a safety net of NTSE patients at outlying hospitals thus also increasing this revenue stream.

Lack of access to EGS care represents a major public health issue that is expected to worsen as the US population ages.13,60,61 Our findings suggest that, despite lack of uniform practices even among presumably high-functioning ACS programs, the specialty of ACS may be able to meet this growing need for EGS coverage. If able to develop a sustainable infrastructure, both in terms of manpower and hospital resources, that addresses local needs, ACS has the potential to streamline costs and enhance revenue while optimizing outcomes for patients with NTSEs. It is notable, however, that respondents indicated frustration that, although trauma programs were well-resourced at the hospital level, EGS often was excluded from such benefits such as dedicated stand-by operating rooms, ED preparedness, and prospective data collection even though patients may be equally ill upon presentation. Thus, although ACS is modeled after trauma systems and their known benefits on injury outcomes,16,17 there is much progress to be made towards an agreed upon systematic, protocolized approach to the care of NTSE patients.

Acknowledgments

The research reported in this publication was in part supported by the University of Massachusetts Clinical Scholar Award (H.P.S.) through the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers UL1RR031982, 1KL2RR031981-01, and UL1TR000161. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The authors are grateful to Drs Lee Hargraves, Timothy A. Emhoff, L. D. Britt, and George C. Velmahos for their input on the initial interview template

APPENDIX

ACUTE CARE SURGERY SPECIALTY

-

1.

Do you consider Acute Care Surgery a specialty within surgery?

If not, ask the following:

-

1a.

How do you consider it?

-

1a.

-

2.

How do you define Acute Care Surgery as a surgical specialty [or whatever used above]?

-

3.

Describe the evolution of Acute Care Surgery as a specialty [or whatever used above].

ACUTE CARE SURGERY TEAM

-

4.

How long has your institution had an Acute Care Surgery team?

-

5.

What clinical problems does your Acute Care Surgery team provide care for?

If trauma and non-trauma surgical emergencies are grouped into a single team ask the following:-

5a–combinedWhat is the rationale for a combined trauma and emergency surgery team?

If trauma is a separate team from the team for non-trauma surgical emergencies ask:-

5a–separate.What is the rationale for separate teams of trauma and non-trauma surgical emergencies?

Also ask the following:-

5b.What is your institution’s approximate volume of trauma cases and non-trauma surgical emergencies annually using 2010 as a reference point?

-

5a–combined

-

6.

Describe how your institution’s Acute Care Surgery Team is structured?

If not answered above ask the following:-

6a.Who makes up the team?

-

6b.What are their qualifications/credentials?

-

6c.How many such individuals are there on the team?

-

6d.What other responsibilities do they have?

-

6e.Describe how residents function on the team.

-

6a.

-

7.

How is call structured? (ask for copy of last 3 month call schedule as an example)

ACUTE CARE SURGERY INFRASTRUCTURE

-

8.

What are your institutional resources for caring for Acute Care Surgery patients?

If not answered above ask the following:-

8a.What is your operating room availability for non-traumatic surgical emergencies?

-

8b.What is your surgical ICU capacity?

-

8c.Describe your ancillary and subspecialty support?

-

8a.

-

9.

Is your institution a designated level 1 trauma center?

If yes, ask the following:-

9a–yes.How, if at all, do you leverage resources from the trauma center infrastructure for Acute Care Surgery?

If no, ask the following:-

9a–no.If you had a Level I trauma center, how would you imagine leveraging resources from the trauma center infrastructure for Acute Care Surgery?

-

9a–yes.

-

10.

Do you collect data for your Acute Care Surgery patients? If so, how and why?

ACUTE CARE SURGERY MODEL

Okay, now that you’ve described your Acute Care Surgery model, consisting of the team and the institutional resources…

-

11.

How do you facilitate communication in this model, both within the team and between the team and its partners across the institution?

-

12.

What benefits does your Acute Care Surgery model provide at the departmental level, at the institutional level and to the broader community that you serve?

If not answered above ask the following:-

12a.Approximately what proportion of your Acute Care Surgery patients are referred from outlying hospitals?

-

12a.

-

13.

What do you think are the strengths and weaknesses of your Acute Care Surgery model?

-

14.

Do you think that the Acute Care Surgery model is financially viable? How so?

ACUTE CARE SURGERY GENERALIZATIONS

-

15.

Why do you practice Acute Care Surgery?

-

16.

What kind of training should residents who also hope to practice Acute Care Surgery have?

If not answered above ask the following:-

16a.Do you believe that Acute Care surgeons need specialized fellowship training?

-

16a.

-

17.

If you could have unlimited resources for an ideal Acute Care Surgery model, how would you design it?

-

18.

What do you think the future holds for Acute Care Surgery as a specialty [or whatever used above]?

Footnotes

H.P.S. was a member of the RWJ Clinical Scholars Program, Chicago, IL, 2003–2005.

REFERENCES

- 1.Future of emergency care: hospital-based emergency care at the breaking point. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Future of emergency care: emergency medical services at the crossroads. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim PK, Dabrowski GP, Reilly PM, Auerbach S, Kauder DR, Schwab CW. Redefining the future of trauma surgery as a comprehensive trauma and emergency general surgery service. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;199:96–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Austin MT, Diaz JJ, Jr., Feurer ID, Miller RS, May AK, Guilla-mondegui OD, et al. Creating an emergency general surgery service enhances the productivity of trauma surgeons, general surgeons and the hospital. J Trauma. 2005;58:906–910. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000162139.36447.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garland AM, Riskin DJ, Brundage SI, Moritz F, Spain DA, Purtill M-A, et al. A county hospital surgical practice: a model for acute care surgery. Am J Surg. 2007;194:758–764. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maa J, Carter JT, Gosnell JE, Wachter R, Harris HW. The surgical hospitalist: a new model for emergency surgical care. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;205:704–711. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Britt RC, Weireter LJ, Britt LD. Initial implementation of an acute care surgery model: implications for timeliness of care. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;209:421–424. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.06.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scherer LA, Battistella FD. Trauma and emergency surgery: an evolutionary direction for trauma surgeons. J Trauma. 2004;56:7–12. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000108633.77585.3B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cherry-Bukowiec JR, Miller BS, Doherty GM, Brunsvold ME, Hemmila MR, Park PK, et al. Nontrauma emergency surgery: optimal case mix for general surgery and acute care surgery training. J Trauma. 2011;71:1422–1426. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318232ced1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rubinfeld I, Thomas C, Berry S, Murthy R, Obeid N, Azuh O, et al. Octogenarian abdominal surgical emergencies: not so grim a problem with the acute care surgery model? J Trauma. 2009;67:983–989. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181ad6690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis R. Shortage of surgeons pinches US hospitals. USA Today. 2008 Feb 26; [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwab CW. The future of emergency care for America: in crisis, at peril and in need of resuscitation! J Trauma. 2006;61:771–773. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200610000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Division of Advocacy, Health Policy. A growing crisis in patient access to emergency surgical care. Bull Am Coll Surg. 2006;91:8–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Malley AS, Draper DA, Felland LE. Hospital emergency on-call coverage: is there a doctor in the house? Issue Brief Cent Stud Health Syst Change. 2007:1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Accidental death and disability: The neglected disease of modern society. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 1966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.MacKenzie EJ, Rivara FP, Jurkovich GJ, Nathens AB, Frey KP, Egleston BL, et al. A national evaluation of the effect of trauma-center care on mortality. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:366–378. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa052049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Celso B, Tepas J, Langland-Orban B, Pracht E, Papa L, Lottenberg L, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis comparing outcome of severely injured patients treated in trauma centers following the establishment of trauma systems. J Trauma. 2006;60:371–378. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000197916.99629.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Acute care surgery: trauma, critical care, and emergency surgery. J Trauma. 2005;58:614–616. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000159347.03278.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rotondo MF, Esposito TJ, Reilly PM, Barie PS, Meredith JW, Eddy VA, et al. The position of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma on the future of trauma surgery. J Trauma. 2005;59:77–79. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000171848.22633.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ball CG, Hameed SM, Brenneman FD. Acute care surgery: a new strategy for the general surgery patients left behind. Can J Surg. 2010;53:84–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ciesla DJ, Moore EE, Moore JB, Johnson JL, Cothren CC, Burch JM. The academic trauma center is a model for the future trauma and acute care surgeon. J Trauma. 2005;58:657–661. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000159241.62333.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yaghoubian A, Kaji AH, Ishaque B, Park J, Rosing DK, Lee S, et al. Acute care surgery performed by sleep deprived residents: are outcomes affected? J Surg Res. 2010;163:192–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pryor JP, Reilly PM, Schwab CW, Kauder DR, Dabrowski GP, Gracias VH, et al. Integrating emergency general surgery with a trauma service: impact on the care of injured patients. J Trauma. 2004;57:467–471. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000141030.82619.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Earley AS, Pryor JP, Kim PK, Hedrick JH, Kurichi JE, Minogue AC, et al. An acute care surgery model improves outcomes in patients with appendicitis. Ann Surg. 2006;244:498–504. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000237756.86181.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ekeh AP, Monson B, Wozniak CJ, Armstrong M, McCarthy MC. Management of acute appendicitis by an acute care surgery service: is operative intervention timely? J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207:43–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lehane CW, Jootun RN, Bennett M, Wong S, Truskett P. Does an acute care surgical model improve the management and outcome of acute cholecystitis? ANZ J Surg. 2010;80:438–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2010.05312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lau B, Difronzo LA. An acute care surgery model improves timeliness of care and reduces hospital stay for patients with acute cholecystitis. Am Surg. 2011;77:1318–1321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stawicki SP, Brooks A, Bilski T, Scaff D, Gupta R, Schwab CW, et al. The concept of damage control: extending the paradigm to emergency general surgery. Injury. 2008;39:93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ciesla DJ, Cha JY, Smith JS, 3rd, Llerena LE, Smith DJ. Implementation of an acute care surgery service at an academic trauma center. Am J Surg. 2011;202:779–785. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qureshi A, Smith A, Wright F, Brenneman F, Rizoli S, Hsieh T, et al. The impact of an acute care emergency surgical service on timely surgical decision-making and emergency department overcrowding. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;213:284–293. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Santry HP, Janjua S, Chang Y, Petrovick L, Velmahos GC. In-terhospital transfers of acute care surgery patients: a plea for regionalization of care. World J Surg. 2011;35:2660–2667. doi: 10.1007/s00268-011-1292-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Britt RC, Bouchard C, Weireter LJ, Britt LD. Impact of acute care surgery on biliary disease. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210:595–599. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matsushima K, Cook A, Tollack L, Shafi S, Frankel H. An acute care surgery model provides safe and timely care for both trauma and emergency general surgery patients. J Surg Res. 2011;166:e143–e147. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2010.11.922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Malterud K. Qualitative research: standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet. 2001;358:483–488. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05627-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Giacomini MK, Cook DJ. Users’ guides to the medical literature: XXIII. Qualitative research in health care B. What are the results and how do they help me care for my patients? Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 2000;284:478–482. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.4.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Giacomini MK, Cook DJ. Users’ guides to the medical literature: XXIII. Qualitative research in health care A. Are the results of the study valid? Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 2000;284:357–362. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.3.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res. 2007;42:1758–1772. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine Publishing Company; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jurkovich GJ. Acute care surgery: The trauma surgeon’s perspective. Surgery. 2007;141:293–296. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reilly PM, Schwab CW. Acute care surgery: the academic hospital’s perspective. Surgery. 2007;141:299–301. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rotondo MF. At the center of the “perfect storm”: the patient. Surgery. 2007;141:291–292. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gandy RC, Truskett PG, Wong SW, Smith S, Bennett MH, Parasyn AD. Outcomes of appendicectomy in an acute care surgery model. Med J Aust. 2010;193:281–284. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2010.tb03908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cubas RF, Gomez NR, Rodriguez S, Wanis M, Sivanandam A, Garberoglio CA. Outcomes in the management of appendicitis and cholecystitis in the setting of a new acute care surgery service model: impact on timing and cost. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;215:715–721. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.06.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Philibert I. Use of strategies from high-reliability organisations to the patient hand-off by resident physicians: practical implications. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18:261–266. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2008.031609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zendejas B, Ali SM, Huebner M, Farley DR. Handing over patient care: is it just the old broken telephone game? J Surg Educ. 2011;68:465–471. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arora VM, Manjarrez E, Dressler DD, Basaviah P, Halasya-mani L, Kripalani S. Hospitalist handoffs: a systematic review and task force recommendations. J Hosp Med. 2009;4:433–440. doi: 10.1002/jhm.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Riesenberg LA, Leitzsch J, Massucci JL, Jaeger J, Rosenfeld JC, Patow C, et al. Residents’ and attending physicians’ handoffs: a systematic review of the literature. Acad Med. 2009;84:1775–1787. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181bf51a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Telem DA, Buch KE, Ellis S, Coakley B, Divino CM. Integration of a formalized handoff system into the surgical curriculum: resident perspectives and early results. Arch Surg. 2011;146:89–93. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2010.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sanfey H, Stiles B, Hedrick T, Sawyer RG. Morning report: combining education with patient handover. Surgeon. 2008;6:94–100. doi: 10.1016/s1479-666x(08)80072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stiles BM, Reece TB, Hedrick TL, Garwood RA, Hughes MG, Dubose JJ, et al. General surgery morning report: a competency-based conference that enhances patient care and resident education. Curr Surg. 2006;63:385–390. doi: 10.1016/j.cursur.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Emlet LL, Al-Khafaji A, Kim YH, Venkataraman R, Rogers PL, Angus DC. Trial of shift scheduling with standardized sign-out to improve continuity of care in intensive care units. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:3129–3134. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182657b5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Selden NR. American College of Surgeons trauma center verification requirements. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;216:167. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Becher RD, Meredith JW, Chang MC, Hoth JJ, Beard HR, Miller PR. Creation and implementation of an emergency general surgery registry modeled after the National Trauma Data Bank. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;214:156–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gunter OL, Guillamondegui OD, May AK, Diaz JJ. Outcome of necrotizing skin and soft tissue infections. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2008;9:443–450. doi: 10.1089/sur.2007.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Williams TE, Jr., Ellison EC. Population analysis predicts a future critical shortage of general surgeons. Surgery. 2008;144:548–554. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2008.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fischer JE. The impending disappearance of the general surgeon. JAMA. 2007;298:2191–2193. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.18.2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Polk HC, Jr., Bland KI, Ellison EC, Grosfeld J, Trunkey DD, Stain SC, et al. A proposal for enhancing the general surgical workforce and access to surgical care. Ann Surg. 2012;255:611–617. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31824b194b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sheldon GF. Access to care and the surgeon shortage: American Surgical Association forum. Ann Surg. 2010;252:582–590. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181f886b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stitzenberg KB, Sheldon GF. Progressive specialization within general surgery: adding to the complexity of workforce planning. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;201:925–932. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.06.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liu JH, Etzioni DA, O’Connell JB, Maggard MA, Ko CY. The increasing workload of general surgery. Arch Surg. 2004;139:423–428. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.139.4.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Etzioni DA, Liu JH, Maggard MA, Ko CY. The aging population and its impact on the surgery workforce. Ann Surg. 2003;238:170–177. doi: 10.1097/01.SLA.0000081085.98792.3d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]