Abstract

Purpose

The frequency of RAS mutations in chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML) suggests that activation of the MAPK pathway is important in CMML pathogenesis. Accordingly, we hypothesized that mutations in other members of the MAPK pathway might be overrepresented in RASwt CMML.

Methods

We performed next generation sequencing analysis on 70 CMML patients with known RAS mutation status using the TruSeq Amplicon Cancer Panel kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA).

Results

The study group included 37 men and 33 women with a median age of 67.8 years (range, 28–86 years). Forty patients were RASwt and 30 were RASmut; the latter included KRAS=17; NRAS=12; KRAS+NRAS=1. Next-generation sequencing showed 5 patients (7.1% of total group; 12.5% of RASwt group) with RASwt who had BRAF mutations. All BRAFmut patients had CMML-1; 2 (40%) with MPN-CMML and 3 with MDS-CMML. The BRAF mutations were of missense type and involved exon 11 in 1 patient and exon 15 in 4 patients. All BRAFmut patients had CMML-1 with low-risk cytogenetic findings, and none of the BRAFmut CMML cases were therapy-related. Two (40%) of the 5 patients with BRAFmut patients transformed to acute myeloid leukemia during follow up. Multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression modeling suggests that BRAFmut status is associated with overall survival (p=0.04). Additionally, the RASmut group tended to have worse OS compared to the RASwt group.

Conclusion

In summary, we demonstrate that a subset of patients with RASwt CMML harbors BRAF kinase domain mutations that are potentially capable of activating the MAPK signaling pathway.

Keywords: chronic myelomonocytic leukemia, next-generation sequencing, BRAF, KRAS, NRAS

INTRODUCTION

Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML) is a heterogeneous clonal myeloid neoplasm characterized by persistent absolute monocytosis in association with myelodysplastic (MDS) and/or myeloproliferative (MP) features.1 RAS mutations, especially KRAS and NRAS, are among the most common somatic mutations in CMML and are therefore believed to play an important role in its pathogenesis.2–4 Further supporting this hypothesis, oncogenic NRAS5–7 and KRAS8 mutations have been shown to initiate hematologic malignancies with features of CMML in murine models.

RAS proteins (HRAS, NRAS, and KRAS) are members of the small GTPases superfamily. They play a central role in cell signaling through dual activation of the RAS-RAF-MEK-MAPK-ERK (MAPK) pathway, an important regulator of cell proliferation, differentiation, and survival.9 RAF kinases, especially BRAF and CRAF, are potent transducers of RAS-dependent ERK activation. Regulation of BRAF activation is complex and modulated by a variety of conformational and post-translational factors.10,11 BRAF mutations have been identified in a variety of human malignancies, of which the most common is BRAFV600E in malignant melanoma.12,13 As in other kinases, BRAF mutations may lead to increased, low, or impaired kinase activity compared with wild-type BRAF. Notably, however, BRAF mutants with low or impaired kinase activity are capable of constitutive MAPK activation, often through CRAF simulation.14

Mutational analysis of CMML using next-generation sequencing (NGS) techniques has uncovered recurrent somatic mutations in a variety of gene families, primarily spliceosome genes15 and genes involved in epigenetic regulation16. A recent elegant study by Itzykson et al demonstrated that mutations in cell signaling genes seem to represent important secondary events acquired subsequent to an initiating ancestral stem cell event.17 In view of compelling data suggesting a critical role of RAS mutations in the pathogenesis of CMML5,6,8,18–20, we hypothesized that mutations in other members of the MAPK pathway might be contributing factors in RASwt CMML cases and could represent alternate routes to constitutive MAPK/ERK kinase (MEK) activation. Furthermore, identification of MEK activation mechanisms appears critically important for selection of MEK inhibitors as these have variant efficacies depending on whether MEK activation is mediated through RAS or RAF mutations.21

In this study, we assessed a group of CMML patients with and without RAS mutations for mutations in other members of the MAPK pathway using targeted NGS-based mutation analysis.

STUDY DESIGN

Study Group

A total of 71 patients diagnosed with CMML according to the World Health Organization classification criteria and with known RAS mutation status were included in this study. RAS mutation status was determined as part of routine clinical workup by PCR-based mutation analysis (codons 12, 13, and 61) as described previously.22 Demographic, laboratory, and clinical data were collected by chart review with emphasis on variables of demonstrated prognostic utility in CMML.23 Therapies were heterogeneous and included primarily hypomethylating agents. Karyotyping results were used to derive a CMML-specific cytogenetic risk score as described by Such et al.24 This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of The University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center.

Next-generation sequencing-based mutation analysis

Next-generation sequencing mutation analysis was performed on 250ng of DNA from unsorted bone marrow or peripheral blood patient samples using the TruSeq Amplicon Cancer Panel kit (TSACP) (Illumina, San Diego, CA). The TSACP interrogates 212 specific genomic areas spanning mutational hotspots in 48 cancer- related genes: AKT1, BRAF, FGFR1, GNAS, IDH1, FGFR2, KRAS, NRAS, PIK3CA, MET, RET, EGFR, JAK2, MPL, PDGFRA, PTEN, TP53, FGFR3, FLT3, KIT, ERBB2, ABL1, HNF1A, HRAS, ATM, RB1, CDH1, SMAD4, STK11, ALK, SRC, SMARCB1, VHL, MLH1, CTNNB1, KDR, FBXW7, APC, CSF1R, NPM1, SMO, ERBB4, CDKN2A, NOTCH1, JAK3, PTPN11, GNAQ and GNA11. Additionally, 7 probe pairs targeting DNMT3A, XPO1, KLHL6, MYD88 and EZH2 were designed by Illumina on request and spiked into the original TSACP pool.

Library preparation was carried out following the manufacturer’s instructions and was analyzed using the Agilent 2200 Tape Station Nucleic Acid System. Successful library preparation, confirmed by the presence of a distinct nucleic acid band at 310bp, was followed by purification using AMPure magnetic beads (Agentcourt, Brea, California) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. One patient sample failed library preparation and was excluded from this study. From each library, equal quantities of the library DNA were isolated and eluted using library normalization beads (TSACP kit) per manufacturer’s instructions. This ensures equal representation of the library from each sample during multiplexed sequencing. Paired end (bidirectional) sequencing was performed using the MiSeq Reagent Kit, V1 (300 cycles) on the MiSeq sequencer (Illumina). Libraries from 10 samples were multiplexed on each sequencing run. Base calling and sequencing run summary were obtained using Real Time Analysis Software (V1.14.23) (Illumina). Sequencing quality was evident by the Q30 scores (one error in 1,000 base pair sequence), and a cutoff of 85% sequence with Q30 score was used as an indication of successful sequencing.

Human genome build 19 (hg19) was used as the reference for sequence alignment. Alignment of the sequence to Human Genome Build 19 reference genome and variant calling was performed by MiSeq Reporter Software 1.3.17. Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) was used for visualization of read alignment, presence of variants, confirmation of variant call veracity, and checking for sequencing errors. Distinction between polymorphisms and mutations was conducted through query of annotated public databases (dbSNP and Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC), historical data on samples analyzed through our pipeline, and literature search. A sequencing coverage of 80× (bidirectional) and a variant frequency >5% in the background of wild type (WT) were used as cutoffs.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive data were compared using Fisher’s exact test for proportions and Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables. Patients with no event at the time of analysis were censored at date of last follow-up. OS curves were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Differences in survival time between groups of patients were tested using the log-rank test. Multivariate analysis was performed with a Cox proportional hazards regression model. The hazard ratio (HR) and its 95% CI were provided. Given the limited sample size, P=0.10 was set as the threshold for statistical significance. All analyses were performed using R version 2.15.2. Overall survival and time to acute myeloid leukemia (AML) transformation were calculated from the date of first bone marrow diagnosis or date of first presentation to our institution, whichever was earlier.

RESULTS

Study group characteristics

The study group included 70 patients who underwent successful NGS mutation analysis. The patients included 37 men and 33 women with a median age of 67.8 years (range, 28–86 years). At presentation, 36 patients had CMML (33 CMML-1, 3 CMML-2) with low blood counts, and 34 patients had CMML (25 CMML-1, 9 CMML-2) with high blood counts. These patient subsets have been classified by the French-American-British group as MDS-CMML and MPN-CMML, respectively.25 Patients with MDS-CMML had a median white blood count (WBC) of 6 × 103/μL while patients with MPN-CMML had a median WBC of 25.6 × 103/μL. Patients had a median follow up of 26 months (range, 2–109 months). The presenting clinical features and outcomes of the study group stratified according to RAS mutation status are summarized in Table 1. The study group included 40 CMML patients with RASwt and 30 CMML patients with RASmut cases.

Table 1.

Presenting clinical features and outcomes of patients with chronic myelomonocytic leukemia by RAS mutation status.

| Feature | RASmut Group | RASwt Group | p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| n=30 | n=40 | ||

| Age (years) | |||

| Median | 63.7 | 69.83 | 0.04 |

| Range | 49.4–79.1 | 46.7–86.2 | |

|

| |||

| Gender (%) | |||

| Male | 63 | 68 | 0.8 |

| Female | 37 | 32 | |

|

| |||

| WHO classification (n) | |||

| CMML-1 | 22 | 36 | 0.11 |

| CMML-2 | 8 | 4 | |

|

| |||

| Complete blood count | |||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.2 | 10.1 | 0.06 |

| White blood count (x103/μL) | 13.6 | 8.1 | 0.24 |

| Absolute neutrophil count (x103/μL) | 6.6 | 4.2 | 0.37 |

| Absolute lymphocyte count (x103/μL) | 2.0 | 1.7 | 0.40 |

| Absolute monocyte count(x103/μL) | 2.7 | 2.0 | 0.13 |

| Platelets (x103/μL) | 93 | 103 | 0.14 |

| Blasts (%) | 0 | 0 | 0.65 |

|

| |||

| Cytogenetic risk group† (%) | |||

| Low | 3.3 | 4.0 | 0.45 |

| Intermediate | 76.7 | 12.5 | |

| Poor | 20.0 | 67.5 | |

|

| |||

| AML transformation (%) | 23.3 | 20.0 | 0.26 |

|

| |||

| Overall survival (%) | 36.7 | 12.5 | 0.09 |

WHO: World Health Organization; AML: Acute myeloid leukemia.

Wilcoxon test for all except Age (t-Test); Sex, WHO classification, Cytogenetic risk group (Log-rank test); Overall survival (Fisher exact test)

According to Such et al.24

RASmut group

The RAS mutations involved KRAS (n=17), NRAS (n=12), or both KRAS and NRAS (n=1) (Table 2). The TSACP interrogates KRAS exons 2 (codons 1–22), 3 (codons 38–63), and 4 (codons 103–147) and NRAS exons 2 (codons 1–18) and 3 (codons 38–62). KRAS and NRAS mutations in codons 12, 13, and 61 in CMML have been well-characterized.2,26 There was 99.98% concordance between RAS mutation status by PCR analysis and NGS analysis. One case with KRAS K117N by NGS had been missed by PCR analysis since codon 117 was not surveyed in the latter assay (included with RASmut group in Table 1).

Table 2.

KRAS, NRAS, and BRAF mutations in chronic myelomonocytic leukemia.

| ID | Gene | Mutation | Exon | Variant | Amino acids |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 | KRAS | NM_033360.2(KRAS):c.176_178del p.A59del | 3 | CAGG->G | n/a |

| 7 | KRAS | NM_033360.2(KRAS):c.179G>T p.G60V | 3 | G->T | Glycine>Valine |

| 1 | KRAS | NM_033360.2(KRAS):c.183A>T p.Q61H | 3 | A->T | Glutamine>Histidine |

| 3, 9, 12, 14, 63 | KRAS | NM_033360.2(KRAS):c.34G>A p.G12S | 2 | G->A | Glycine>Serine |

| 30, 33*, 36 | KRAS | NM_033360.2(KRAS):c.34G>C p.G12R | 2 | G->C | Glycine>Arginine |

| 22 | KRAS | NM_033360.2(KRAS):c.351A>T p.K117N | 4 | A->T | Lysine>Asparagine |

| 5, 8, 16, 25 | KRAS | NM_033360.2(KRAS):c.35G>A p.G12D | 2 | G->A | Glycine>Aspartate |

| 19 | KRAS | NM_033360.2(KRAS):c.35G>C p.G12A | 2 | G->C | Glycine>Alanine |

| 6 | KRAS | NM_033360.2(KRAS):c.38G>A p.G13D | 2 | G->A | Glycine>Aspartate |

| 62 | NRAS | NM_002524.4(NRAS):c.181C>G p.Q61E | 3 | C->G | Glutamine>Glutamate |

| 13, 64 | NRAS | NM_002524.4(NRAS):c.34G>A p.G12S | 2 | G->A | Glycine>Serine |

| 62 | NRAS | NM_002524.4(NRAS):c.34G>C p.G12R | 2 | G->C | Glycine>Arginine |

| 23, 27, 28, 32, 33*, 65, 74, 81 | NRAS | NM_002524.4(NRAS):c.35G>A p.G12D | 2 | G->A | Glycine>Aspartate |

| 32 | NRAS | NM_002524.4(NRAS):c.35G>T p.G12V | 2 | G->T | Glycine>Valine |

| 20 | NRAS | NM_002524.4(NRAS):c.38G>A p.G13D | 2 | G->A | Glycine>Aspartate |

| 18 | NRAS | NM_002524.4(NRAS):c.38G>T p.G13V | 2 | G->T | Glycine>Valine |

| 4 | BRAF | NM_004333.4(BRAF):c.1782T>A p.D594E | 15 | T->A | Threonine>Alanine |

| 11 | BRAF | NM_004333.4(BRAF):c.1782T>A p.D594E | 15 | T->A | Threonine>Alanine |

| 24 | BRAF | NM_004333.4(BRAF):c.1742A>G p.N581S | 15 | A->G | Alanine>Glycine |

| 58 | BRAF | NM_004333.4(BRAF):c.1790T>A p.L597Q | 15 | T->A | Threonine>Alanine |

| 82 | BRAF | NM_004333.4(BRAF):c.1397G>A p.G466E | 11 | G->A | Glycine>Alanine |

Dual KRAS/NRAS mutations.

Among the 17 KRASmut patients, 16 (94.1%) presented to our institution with CMML-1 and 1 with CMML-2; 7 (41.2%) had MPN-CMML and 10 had MDS-CMML. Among the 12 NRASmut patients, 7(58.3%) presented to our institution with CMML-1 and 5 had CMML-2; 7 (58.3%) had MPN-CMML and 5 had MDS-CMML. Four (23.5%) KRASmut and 3 (25%) NRASmut patients in the group transformed to AML during follow up. Three NRASmut patients and 1 KRASmut patients had therapy-related CMML (t-CMML).

All patients with KRAS mutations harbored only one mutation. Two patients with NRAS mutation had two simultaneous NRAS mutations (G12D+G12V; Q61E+G12R) suggestive of the presence of two clones with different NRAS mutations. As described by others2, most RASmut CMML patients harbored a mutation in either KRAS or NRAS. Kohlman et al identified 3/81 (3.7%) patients with dual KRAS+NRAS mutations; 1 patient (1.4%) had a similar finding in our study group.

BRAFmut group

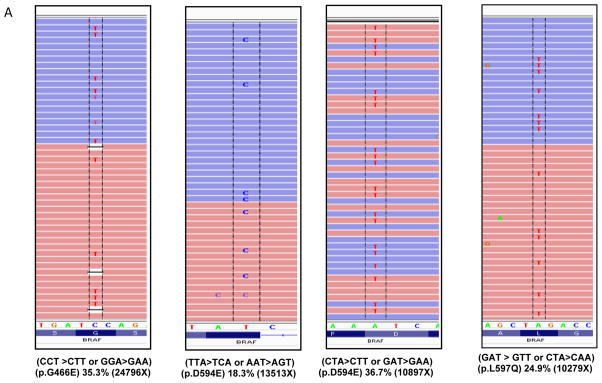

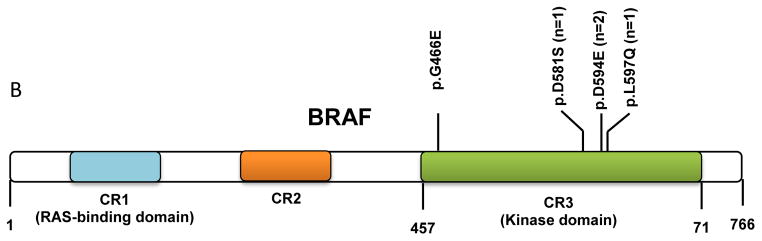

We identified 5 CMML patients with BRAF mutations (Table 2). This subset represented 7.1% of the total group and 12.5% of the RASwt subset. The TSACP interrogates BRAF hotspots in exons 11 (codons 439–471) and 15 (codons 581–606). All 5 mutations were of missense type with 4 involving exon 15 and 1 located in exon 11. The detection of these BRAF mutations in the aligned reads from sequencing results as visualized by IGV are shown in Figure 2A along with the corresponding depth of sequencing, nucleotide and amino acid changes. The mutation spots in the BRAF kinase domain are illustrated in Figure 2B.

Figure 2. BRAF mutations detected in chronic myelomonocytic leukemia cases.

(A) A total of 5 cases were found to be positive for mutations in the BRAF kinase domain. Representative images of the aligned sequencing reads (red=forward; blue=reverse) with the mutations are shown along with the respective percent variant allele frequency and the sequencing depth (X). (B) A schematic diagram depicting the position and number of mutations occurring in the kinase domain of BRAF. (CR: conserved regions)

All BRAFmut patients presented to our institution with CMML-1; 2 (40%) patients had myeloproliferative features (MPN-CMML) and 3 patients had low/normal count CMML (MDS-CMML). All 5 patients with BRAF mutations had low-risk cytogenetics and none had therapy-related CMML. Two BRAFmut patients in the group transformed to AML during the follow up interval.

CMML group with mutations other than RAS/BRAF

The majority of CMML patients in this group could be divided into two broad groups: one patient group associated with genes encoding kinases (n=6) and a second patient group associated with mutations in nonkinase oncogenes (n=5).

In the first group, FLT mutations were detected in 2 patients, one with D835Y and another with internal tandem duplication (ITD). The patient with FLT3D835Y also harbored an IDH1 mutation during the CMML (myelodysplastic-type) and subsequent AML transformation phase, of which the patient died. Another 2 patients in this group had JAK2V617F mutation. Two patients in this group had mutations in STK11, a serine threonine kinase that is also known as Liver Kinase B1 (LKB1). A third patient with STK11 mutation also had a KRAS mutation.

In the second group, with mutations involving nonkinase genes, isolated mutations were detected in TP53 (n=3), NPM1 (n=1), and IDH2 (n=1). Notably, 2 patients with TP53 mutation had an identical missense substitution at codon 163 in exon 5 resulting in replacement of the tyrosine residue with aspartate (c.487T>G p.Y163D). This mutation is located within the DNA-binding domain and has been described in other malignancies.27,28 A third patient with TP53 mutation, notable for a history of colorectal adenocarcinoma treated with chemotherapy and radiation therapy, had therapy-related CMML with intermediate risk cytogenetics and a missense substitution at codon 179 in exon 5 resulting in replacement of the histidine residue with arginine (c.536A>G p.H179R). This TP53 mutation has been demonstrated to correlate with progression to blast crisis in chronic myelogenous leukemia.29 Of note, Solomon and colleagues have shown that TP53H179R can promote a cancer-related gene signature through augmentation of RAS (HRAS) activity.30

CMML group with no detected mutations

No mutations in the genes/regions assessed by the targeted panel used in this study were detected in 26 patients (37.1%). In this subgroup, 1 patient (3.8%) presented with CMML-1 and 25 patients had CMML-2. These cases included 8 with MPN-CMML and 18 with MDS-CMML. Four (15.4%) patients had therapy-related CMML (t-CMML). Four (15.4%) patients in this group transformed to AML during follow up.

Clinical implications of detected mutational status

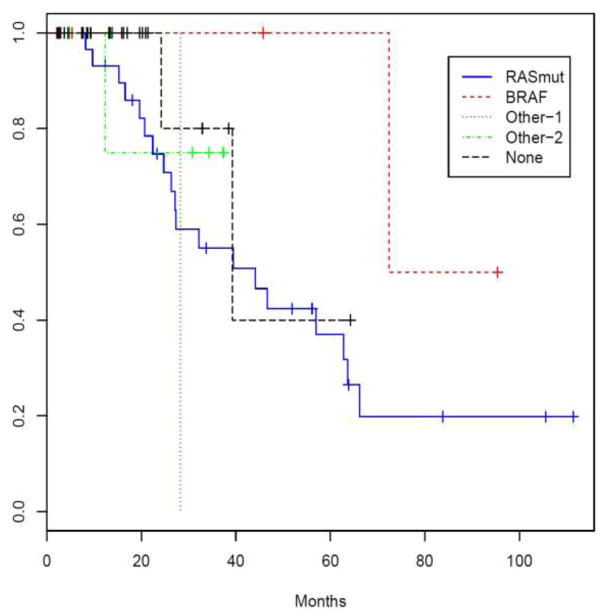

When the RASmut and BRAFmut were grouped together on the basis of presumptive pathogenic MAPK perturbations (MAPKmut, n=36) and compared to the remaining cases (MAPKwt, n=34), the groups had a significant difference in percentage of bone marrow blasts (p=0.02) and age at diagnosis (p=0.03). We then categorized cases on the basis of NGS findings into five broad categories: (1) RASmut, (2) BRAFmut, (3) cases with mutations in genes encoding kinases, (4) cases with mutations in nonkinase oncogenes, and (5) cases without mutations. Categorized as such, with limitations of sample size in some of the groups notwithstanding, there was a significant difference in time to AML transformation (p=0.016, Log-rank test). Additionally, multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression modeling demonstrated that BRAFmut status is associated with OS in this study group (p=0.04). (Table 3) Finally, Kaplan-Meier analysis suggests that even though there is no apparent difference in OS among the mutation groups (p=0.429), the BRAFmut group seems to have a favorable OS. (Figure 3) There was no significant difference in the length of time to AML transformation among the mutation groups.

Table 3.

Multivariate cox proportional hazards regression analysis

| Parameter | HR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| BRAF mutations | −2.53 | (0.007,0.916) | 0.04 |

| Mutations in genes encoding kinases | −0.99 | (0.031,4.483) | 0.44 |

| Mutations in genes encoding nonkinase oncogenes | −1.37 | (0.018,3.469) | 0.30 |

| No detected mutations | −1.70 | (0.025,1.327) | 0.09 |

| Gender | 0.63 | (0.377,9.369) | 0.44 |

| Age | 0.06 | (0.985,1.137) | 0.12 |

| Hemoglobin | −0.34 | (0.488,1.036) | 0.08 |

| White blood count | −0.05 | (0.679,1.336) | 0.78 |

| Absolute neutrophil count | 0.02 | (0.678,1.550) | 0.91 |

| Absolute lymphocyte count | −0.14 | (0.561,1.358) | 0.55 |

| Absolute monocyte count | 0.16 | (0.730,1.891) | 0.51 |

| Platelets | 0.00 | (0.990,1.007) | 0.66 |

| Peripheral blood blast % | −3.60 | (0.001,1.041) | 0.05 |

| Bone marrow blast % | 0.04 | (0.920,1.175) | 0.54 |

Figure 3. Overall survival analysis.

Patients in the BRAF mutation group tended to have a better overall survival whereas patients in with mutations in genes encoding kinases (“Other-1”=FLT3, JAK2, JAK3, MET, STK11, GNA11, FGFR3) had a worse overall survival. The “Other-2” category includes cases with mutations in nonkinase oncogenes (TP53, NPM1, IDH1, IDH2, EZH2).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we compared mutation analysis data in RASmut and RASwt CMML patients and show that a subset of the latter group harbor mutations in other genes that play an important role in the activating the MAPK pathway. These data further support murine models and previous reports highlighting the importance of upregulated MAPK activation in the pathogenesis of CMML.2,3,5–8 Yet, while the most common mechanism of the MAPK activation in CMML is through activating mutations in either KRAS or NRAS, we showed for the first time that BRAF mutations and mutations in genes such as STK11 with demonstrated impact on the MAPK pathway are overrepresented in RASwt CMML. These mutations likely function as obligatory secondary mutations that contribute to constitutive activation of the MAPK pathway. Importantly, since RASmut and BRAFmut tumors appear to regulate MEK activation through distinct mechanisms21, distinguishing such subsets in CMML will likely have implications for the selection of MEK inhibitors as part of targeted therapy.

BRAF mutations in CMML are heterogeneous and include mutations that lead to increased (BRAFL597Q), low (BRAFG466E), or impaired (BRAFD594) kinase activity.14,31–34 Among the 5 cases with BRAF mutations (4 in exon 15 and 1 in exon 11) in our study group, 2 cases harbored the BRAFD594E mutation while the other three mutations were seen in 1 case each. Although mutations involving aspartame-594 residues are common among BRAF mutations12, to our knowledge the BRAFD594E mutation has not been described. Mutations at this site (BRAFD594A and BRAFD594V) have been shown to result in an inactive kinase protein that is capable of promoting cancer progression through CRAF deregulation.32 Similarly, BRAFG466E has been shown to result in constitutive MEK activation through CRAF activation despite having a lower kinase activity compared with BRAFwt.14,34 The BRAFL597Q mutation, on the other hand, has been shown to result in a functional oncogene in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia.31,33 The BRAFN581S mutation has been reported as a rare event in human malignancies including ovarian and colorectal carcinoma and malignant melanoma.35–37 Notably, none of the BRAFmut cases in our group had concurrent RAS mutations suggesting that such mutations might be mutually exclusive in CMML.

In this study, we also show that a small subset of CMML patients had STK11 mutations. The significance of this finding remains to be fully elucidated. Mutations of the tumor suppressor gene STK11 result in the autosomal dominant Peutz-Jeghers syndrome that is characterized by gastrointestinal hamartomas and an increased risk of epithelial and non-epithelial malignancies.38,39 Inactivating somatic mutations in STK11 have been shown to play an important role in sporadic malignancies including lung cancer40 and melanoma41 by enhancing metastatic potential. Interestingly, the oncogenic effects of BRAF mutations appear to be potentiated through negative regulation of STK11.42 One of the CMML patients with STK11 mutation in this study also had a novel KRASK117N mutation. Interestingly, KRASK117N has been demonstrated to be functional and associated with constitutive activation of the MAPK pathway in a primary melanoma cell line with BRAFV600E and resistance to vemurafenib.43 Additionally, the oncogenic effects of STK11 function loss are significantly augmented in the presence of activating KRAS mutations.15,41 While additional studies are needed, the finding of BRAF and STK11 mutations in patients with RASwt CMML suggest that neoplastic clones harboring such mutations might be propagated, at least in part, by the proliferative and antiapoptotic effects of MEK activation.

The role that somatic mutations play in the pathogenesis and clonal evolution of CMML is complex and likely underlies the phenotypic heterogeneity of the disease. Itzykson et al recently suggested that selection of TET2mut progenitor clones in CMML is accomplished through acquisition of secondary mutations affecting cell signaling genes such as KRAS and NRAS during myeloid differentiation.17 Based on our data, non-RAS mutations such as BRAF and STK11 are likely capable of conferring a growth advantage analogous to RASmut. Investigation of the effect of MAPK inhibitors in such cases would be warranted.

In this study group, mutation analysis appears to have clinical relevance. Notably, RASmut CMML tended to be associated with worse OS as reported by others44, whereas cases with isolated BRAF mutation tended to be associated with a more favorable OS. Interestingly, we identified differences among KRASmut and NRASmut patients in terms of WHO- and FAB-based disease classifications, findings that warrant additional investigation as they suggest a differential impact of KRAS and NRAS mutations on the progression of CMML.

Some limitations are acknowledged in this retrospective study. Namely, NGS was performed on unsorted samples selected based on availability of RAS mutation status and availability of residual DNA. As such, the frequency of some mutations seen in the present study group might not reflect their broad incidence in CMML. Additionally, since our institution is a tertiary cancer center, a selection bias towards more aggressive disease cannot be excluded. Additional investigation of the functional role of some of the mutations discovered in this study are warranted and being pursued.

In summary, we demonstrate that RASwt CMML harbors other mutations that are potentially capable of perturbing the MAPK signaling pathway. Although the scope and mechanisms by which non-RAS mutations that affect the MAPK pathway impact CMML pathobiology remain to be further elucidated, our findings suggest that there are a number of potential therapeutic targets for subversion of MEK activation in patients with CMML.

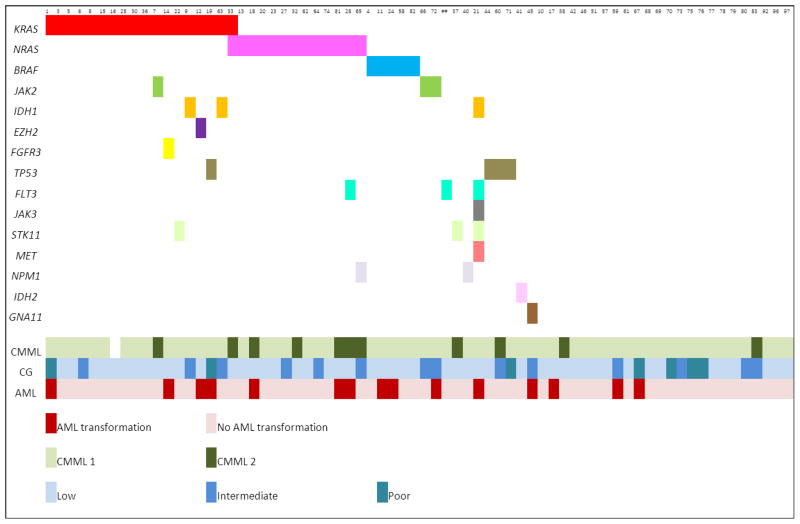

Figure 1. Summary of mutations detected in chronic myelomonocytic leukemia cases.

The top row indicates case number for each of the samples with mutations identified by next-generation sequencing mutation analysis. The bottom rows represent, respectively, the World Health Organization classification category, cytogenetic risk category, and transformation status to acute myeloid leukemia. Abbreviations: CMML=chronic myelomonocytic leukemia; CG=cytogenetics; AML=acute myeloid leukemia.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge outstanding technical support by members of The University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center Molecular Diagnostics Laboratory.

Footnotes

Authorship Contributions: JDK: Conception and design of study, data analysis, and manuscript preparation. LZ and RS: Data collection, data analysis, and manuscript preparation. FS: Statistical analysis. KPP, MR, MJY, RNM, JC, HMK, LJM and RL: Data analysis and manuscript preparation.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: None of the authors has declared competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Orazi A, Bennett JM, Germing U, et al. Chronic Myelomonocytic Leukemia. In: Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al., editors. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon: IARC; 2008. pp. 76–79. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kohlmann A, Grossmann V, Klein HU, et al. Next-generation sequencing technology reveals a characteristic pattern of molecular mutations in 72.8% of chronic myelomonocytic leukemia by detecting frequent alterations in TET2, CBL, RAS, and RUNX1. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3858–65. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parikh SA, Tefferi A. Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia: 2012 update on diagnosis, risk stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2012;87:610–9. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Callahan MK, Rampal R, Harding JJ, et al. Progression of RAS-mutant leukemia during RAF inhibitor treatment. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2316–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1208958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang J, Liu Y, Li Z, et al. Endogenous oncogenic Nras mutation initiates hematopoietic malignancies in a dose- and cell type-dependent manner. Blood. 2011;118:368–79. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-326058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang J, Liu Y, Li Z, et al. Endogenous oncogenic Nras mutation promotes aberrant GM-CSF signaling in granulocytic/monocytic precursors in a murine model of chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. Blood. 2010;116:5991–6002. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-281527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang J, Kong G, Liu Y, et al. NrasG12D/+ promotes leukemogenesis by aberrantly regulating hematopoietic stem cell functions. Blood. 2013;121:5203–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-12-475863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braun BS, Archard JA, Van Ziffle JA, et al. Somatic activation of a conditional KrasG12D allele causes ineffective erythropoiesis in vivo. Blood. 2006;108:2041–4. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-01-013490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pylayeva-Gupta Y, Grabocka E, Bar-Sagi D. RAS oncogenes: weaving a tumorigenic web. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:761–74. doi: 10.1038/nrc3106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roring M, Herr R, Fiala GJ, et al. Distinct requirement for an intact dimer interface in wild-type, V600E and kinase-dead B-Raf signalling. EMBO J. 2012;31:2629–47. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.An L, Jia W, Yu Y, et al. Lys63-linked polyubiquitination of BRAF at lysine 578 is required for BRAF-mediated signaling. Scientific reports. 2013;3:2344. doi: 10.1038/srep02344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature. 2002;417:949–54. doi: 10.1038/nature00766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schubbert S, Shannon K, Bollag G. Hyperactive Ras in developmental disorders and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:295–308. doi: 10.1038/nrc2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wan PT, Garnett MJ, Roe SM, et al. Mechanism of activation of the RAF-ERK signaling pathway by oncogenic mutations of B-RAF. Cell. 2004;116:855–67. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00215-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kar SA, Jankowska A, Makishima H, et al. Spliceosomal gene mutations are frequent events in the diverse mutational spectrum of chronic myelomonocytic leukemia but largely absent in juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia. Haematologica. 2013;98:107–13. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2012.064048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jankowska AM, Makishima H, Tiu RV, et al. Mutational spectrum analysis of chronic myelomonocytic leukemia includes genes associated with epigenetic regulation: UTX, EZH2, and DNMT3A. Blood. 2011;118:3932–41. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-311019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Itzykson R, Kosmider O, Renneville A, et al. Clonal architecture of chronic myelomonocytic leukemias. Blood. 2013;121:2186–98. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-06-440347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Braun BS, Tuveson DA, Kong N, et al. Somatic activation of oncogenic Kras in hematopoietic cells initiates a rapidly fatal myeloproliferative disorder. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:597–602. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307203101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parikh C, Subrahmanyam R, Ren R. Oncogenic NRAS rapidly and efficiently induces CMML- and AML-like diseases in mice. Blood. 2006;108:2349–57. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-08-009498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Q, Haigis KM, McDaniel A, et al. Hematopoiesis and leukemogenesis in mice expressing oncogenic NrasG12D from the endogenous locus. Blood. 2011;117:2022–32. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-280750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hatzivassiliou G, Haling JR, Chen H, et al. Mechanism of MEK inhibition determines efficacy in mutant KRAS- versus BRAF-driven cancers. Nature. 2013 doi: 10.1038/nature12441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zuo Z, Chen SS, Chandra PK, et al. Application of COLD-PCR for improved detection of KRAS mutations in clinical samples. Mod Pathol. 2009;22:1023–31. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2009.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Onida F, Kantarjian HM, Smith TL, et al. Prognostic factors and scoring systems in chronic myelomonocytic leukemia: a retrospective analysis of 213 patients. Blood. 2002;99:840–9. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.3.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Such E, Cervera J, Costa D, et al. Cytogenetic risk stratification in chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. Haematologica. 2011;96:375–83. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2010.030957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bennett JM, Catovsky D, Daniel MT, et al. Proposals for the classification of the myelodysplastic syndromes. Br J Haematol. 1982;51:189–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tyner JW, Erickson H, Deininger MW, et al. High-throughput sequencing screen reveals novel, transforming RAS mutations in myeloid leukemia patients. Blood. 2009;113:1749–55. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-152157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rossi D, Trifonov V, Fangazio M, et al. The coding genome of splenic marginal zone lymphoma: activation of NOTCH2 and other pathways regulating marginal zone development. J Exp Med. 2012;209:1537–51. doi: 10.1084/jem.20120904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hodis E, Watson IR, Kryukov GV, et al. A landscape of driver mutations in melanoma. Cell. 2012;150:251–63. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ashur-Fabian O, Adamsky K, Trakhtenbrot L, et al. Apaf1 in chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) progression: reduced Apaf1 expression is correlated with a H179R p53 mutation during clinical blast crisis. Cell cycle. 2007;6:589–94. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.5.3900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Solomon H, Buganim Y, Kogan-Sakin I, et al. Various p53 mutant proteins differently regulate the Ras circuit to induce a cancer-related gene signature. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:3144–52. doi: 10.1242/jcs.099663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hou P, Liu D, Xing M. The T1790A BRAF mutation (L597Q) in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia is a functional oncogene. Leukemia. 2007;21:2216–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kamata T, Hussain J, Giblett S, et al. BRAF inactivation drives aneuploidy by deregulating CRAF. Cancer Res. 2010;70:8475–86. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gustafsson B, Angelini S, Sander B, et al. Mutations in the BRAF and N-ras genes in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Leukemia. 2005;19:310–2. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garnett MJ, Rana S, Paterson H, et al. Wild-type and mutant B-RAF activate C-RAF through distinct mechanisms involving heterodimerization. Mol Cell. 2005;20:963–9. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature. 2011;474:609–15. doi: 10.1038/nature10166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Board RE, Ellison G, Orr MC, et al. Detection of BRAF mutations in the tumour and serum of patients enrolled in the AZD6244 (ARRY-142886) advanced melanoma phase II study. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:1724–30. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suehiro Y, Wong CW, Chirieac LR, et al. Epigenetic-genetic interactions in the APC/WNT, RAS/RAF, and P53 pathways in colorectal carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:2560–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hemminki A, Markie D, Tomlinson I, et al. A serine/threonine kinase gene defective in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Nature. 1998;391:184–7. doi: 10.1038/34432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jenne DE, Reimann H, Nezu J, et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is caused by mutations in a novel serine threonine kinase. Nat Gen. 1998;18:38–43. doi: 10.1038/ng0198-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ji H, Ramsey MR, Hayes DN, et al. LKB1 modulates lung cancer differentiation and metastasis. Nature. 2007;448:807–10. doi: 10.1038/nature06030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu W, Monahan KB, Pfefferle AD, et al. LKB1/STK11 inactivation leads to expansion of a prometastatic tumor subpopulation in melanoma. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:751–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.03.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zheng B, Jeong JH, Asara JM, et al. Oncogenic B-RAF negatively regulates the tumor suppressor LKB1 to promote melanoma cell proliferation. Mol Cell. 2009;33:237–47. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Su F, Bradley WD, Wang Q, et al. Resistance to selective BRAF inhibition can be mediated by modest upstream pathway activation. Cancer Res. 2012;72:969–78. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ricci C, Fermo E, Corti S, et al. RAS mutations contribute to evolution of chronic myelomonocytic leukemia to the proliferative variant. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:2246–56. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]