Abstract

The immune system protects the organism from foreign invaders and foreign substances and is involved in physiological functions that range from tissue repair to neurocognition. However, an excessive or dysregulated immune response can cause immunopathology and disease. A 39-year-old man was affected by severe hepatosplenic schistosomiasis mansoni and by amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. One question that arose was, whether there was a relation between the parasitic and the neurodegenerative disease. IL-17, a proinflammatory cytokine, is produced mainly by T helper-17 CD4 cells, a recently discovered new lineage of effector CD4 T cells. Experimental mouse models of schistosomiasis have shown that IL-17 is a key player in the immunopathology of schistosomiasis. There are also reports that suggest that IL-17 might have an important role in the pathogenesis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. It is hypothesized that the factors that might have led to increased IL-17 in the hepatosplenic schistosomiasis mansoni might also have contributed to the development of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in the described patient. A multitude of environmental factors, including infections, xenobiotic substances, intestinal microbiota, and vitamin D deficiency, that are able to induce a proinflammatory immune response polarization, might favor the development of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in predisposed individuals.

1. Introduction

Schistosomiasis is a major tropical parasitic disease caused by blood-dwelling fluke worms of the genus Schistosoma. It is contracted by humans when wading in bodies of water contaminated with the free-swimming cercariae, the larval and infective form of the schistosomes, released from aquatic vector snails. Cercariae penetrate the skin, reach the blood circulation, and mature into adult worms and in the case of Schistosoma mansoni home to the mesenteric venous vasculature, where male and female mate and lay 100–300 eggs per day [1, 2]. The lifespan of an adult schistosome averages 3–5 years but can be as long as 30 years [3]. The eggs then exit the vasculature to enter the intestinal lumen and are set free in search of appropriate vector snails. However, many eggs embolize and are trapped mostly in the liver (hepatosplenic schistosomiasis), less frequently in the central nervous system (neuroschistosomiasis), where they precipitate an immune reaction of varying degree. Most individuals develop a relative mild “intestinal” schistosomiasis, whereas 5–10% suffer the severe hepatosplenic form of disease, in which there is progressive liver fibrosis, portal hypertension, splenomegaly, esophageal varicose veins, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, and death [4, 5].

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a fatal neurodegenerative disease characterized by progressive and selected loss of both upper and lower motor neurons. Patients experience signs and symptoms of progressive muscle atrophy and weakness and increased fatigue, which typically lead to respiratory failure and death. Median survival is 2–4 years from onset; only 1–10% of patients survive beyond 10 years. Less than 10% of ALS cases are familial with 20% of these cases linked to various mutations in the Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) gene [6, 7]. The etiology of ALS is unknown. A wide range of contributing factors including genetic mutations and polymorphisms, oxidative stress, and neuroinflammation have been identified; however the initiating or most relevant ones are unknown [6–12]. There were more than 2000 publications on ALS only in 2013. This growing knowledge will hopefully move towards the discovery of an effective treatment and prevention of this tragic disease. We report on a 39-year-old man who presented with progressive hemiparesis of unknown origin, lupus-like autoimmune phenomena, and a suspected reactivation of M. tuberculosis infection. He was subsequently diagnosed as suffering from severe hepatosplenic schistosomiasis mansoni and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. In an attempt to understand the diseases recent advances in immunology were reviewed and it may be that common pathogenic mechanisms might underlie the different diseases.

2. Case Report

A 39-year-old man from Ghana, who had been resident in Italy for five years, was admitted to hospital in April 2013 because of slowly progressive gait disturbances and right hemiparesis which had developed within the last two months. His past medical history was unremarkable. No cerebral vascular lesions were seen neither on magnetic resonance angiography or Doppler sonography. Instead, liver cirrhosis with portal hypertension, esophageal varicose veins, and splenomegaly was detected. He was a mild occasional alcohol drinker and viral hepatitis screening was negative (for laboratory values see Table 1). Hematologic malignancy and leishmaniasis were excluded by bone marrow examination. The presence of antinuclear antibodies, anticardiolipin antibodies detected by TLC immunostaining [13], and lupus anticoagulant, the decrease of the complement factors C3 and C4 were reminiscent of systemic lupus erythematosus (Table 1). Findings of apical scars and calcification of hilar lymph nodes of the right lung detected by computer tomography (CT) and a 15 mm cutaneous tuberculin reaction indicated a Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Therefore standard antituberculous therapy was initiated, considered also as chemoprophylaxis in the perspective of future corticosteroid treatment. 25-hydroxy-vitamin D 10,000 IU (250 μg) weekly was added to treatment. Sufficient criteria for the diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) would had been fulfilled [14]; however, such extreme liver and spleen changes as in this patient are not usually seen in SLE.

Table 1.

Laboratory data.

| Analyte | Reference range | Month 1 | Month 4 | Month 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leukocyte count (×103/μL) | 4.3–11.0 | 1.30 | 1.50 | 1.70 |

| Lymphocytes (×103/μL) | 1.0–3.7 | 0.50 | 0.70 | 0.70 |

| CD4 T cells % | 31–60 | 50 | 53 | |

| CD4 T cells (/μL) | 410–1590 | 311 | 315 | |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 12–16 | 12.9 | 13.4 | 13.8 |

| Platelet count (×103/μL) | 140–450 | 36 | 33 | 51 |

| PT INR | <1.20 | 1.49 | 1.44 | 1.22 |

| PTT RATIO | <1.20 | 1.21 | 1.15 | 1.05 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | <0.50 | 1.4 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| γ-GT (U/L) | <60 | 157 | 246 | 100 |

| AST (IU/liter) | <40 | 56 | 33 | 19 |

| ALT (IU/liter) | <40 | 59 | 87 | 17 |

| Gamma-globulin (%) | 8–16.7 | 19.6 | 14.6 | 12.1 |

| IgE (IU/mL) | <120 | 81 | 175 | 63 |

| Vitamin B12 (pg/mL) | 191–663 | 1.057 | ||

| Folic acid (ng/mL) | 4.6–18.7 | 3.89 | ||

| 25-OH-vitamin D (ng/mL) | 31–100 | 14 | ||

| CPK (IU/liter) | 40–230 | 1,277 | 253 | 84 |

| ANA titer | <1 : 80 | 1 : 320 | 1 : 160 | 1 : 320 |

| C3 (mg/dL) | 79–152 | 68 | 73 | 78 |

| C4 (mg/dL) | 16–38 | 12 | 11 | 12 |

| Lupus anticoagulant panel | ||||

| aPTT-low phospholipid | <1.15 | 0.85 | 0.66 | |

| DRVVT ratio | <1.10 | 1.20 | 1.14 | |

| Anticardiolipin-Ab | positive | |||

| Schistosoma-Ab | positive |

HIV-Ab, HTLV-I/II-Ab, HAV-IgM, HBs-Ag, HCV-Ab, HEV-Ab, CMV-IgM, TPPA, Toxoplasma-Ab, EBV-DNA, Plasmodium falciparum-Ag, and emoscopy for plasmodia: all negative.

Values out of the reference range are in bold.

ALT: alanine transaminase; AST: aspartate transaminase; ANA: antinuclear antibodies; CPK: creatine phosphokinase; CRP. C-reactive protein; DRVVT: dilute viper venome time; γ-GT: γ-glutamyltransferase; PT: prothrombine time; HTLV-I/II: human T lymphotropic virus I/II; PTT: partial thromboplastine time; and TPPA: Treponema pallidum particle agglutination.

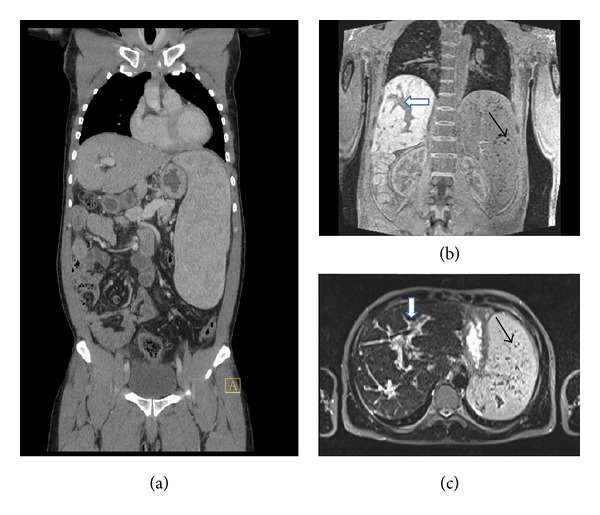

Indeed, a high titer of anti-Schistosoma antibodies was demonstrated. Retrospectively, the ultrasound-, CT-, and MR-imaging that showed the extensive periportal fibrosis of the liver and the huge spleen with a diameter of 24 cm and unusual spots (Figure 1) turned out to be characteristic for hepatosplenic schistosomiasis mansoni. Seven years earlier in the district of Dunkwa in Offin, Ghana, the patient had to wade through water for about 10 minutes daily for more than one year while going to work to cut large trees and requiring physical exertion. Praziquantel 60 mg/kg daily for three days, methyl-prednisolone 1 g daily for five days, and then prednisone 1 mg/kg, tapered in the next three months, were given [15]. Subsequently an improvement in the strength of the right arm was observed for only a few weeks, followed by a worsening of the movement disorder.

Figure 1.

(a) Computerized tomography (CT) imaging showing the enlarged spleen (b) and (c) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrating the periportal fibrosis (white arrows) and the Gamna-Gandy bodies (siderotic nodules) in the spleen (black arrows).

Physical examination four months following his first hospitalization revealed muscle weakness also on the left side. There was increased muscle rigidity, hypotrophic thenar muscles of the right hand, hyperreflexia, and spontaneous and triggered muscle fasciculations. Spirometry showed evidenced deficits of the inspiratory and exspiratory musculature. The patient did not report neither sphincter dysfunction nor pain or sensitivity alterations. This pattern was indicative of motor neuron disease and of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, as were the electromyographic findings. Repeated MRI showed mild diffuse signal hyperintensities of the white matter in the centrum semiovale regions by FLAIR imaging. The gadolinium enhancement of the meninges at the vertebral level D4-D6 was compatible with a reaction to embolized ova of schistosome, but these alterations did not explain the neurological symptoms. Because praziquantel had been given without considering the interaction with rifampin [16], rifampin was stopped. One month later praziquantel was repeated at a dose of 80 mg/kg daily for three days considering the interaction with prednisone [17] at that time given at a dose of 25 mg daily. The movement disorder did not improve despite daily physiotherapy exercises. In the absence of any effective treatment for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis being available to the patient, he returned to Ghana in November 2013.

Thereafter IL-17 has been determined in four serum samples previously stored, which were taken at monthly intervals. IL-17 cytokine was assayed by human-specific ELISA kit (R&D Systems) at the Department of Experimental Medicine, Sapienza University, Rome. The first sample was taken before initiating treatment with praziquantel and high dose corticosteroids. The results were IL-17 672.2 pg/mL, 36.5 pg/mL, <10 pg/mL, and 32.9 pg/mL, respectively, (normal value <31.2 pg/mL).

3. Discussion

3.1. Diagnostic Considerations

According to the new SLICC classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) at least 4 out of 17 criteria are necessary for the diagnosis of SLE [14]. Of these 17 classification criteria the described patient satisfied the following 7 criteria: neurologic symptoms, leukopenia, lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia, antinuclear antibodies, antiphospholipid antibodies (anticardiolipin antibodies, lupus anticoagulant), and reduced complement C3, C4. But such extreme hepatosplenomegaly (Figure 1) is usually not seen in SLE. Indeed, the extensive periportal fibrosis, the marked hypertrophy of the left hepatic and caudate lobe, the marked hypotrophy of the right hepatic lobe, and the huge spleen with spots (siderotic nodules, Gamna-Gandy bodies), which was a pattern of abnormalities that had never been seen at the General Hospital of Bolzano, turned out to be characteristic for hepatosplenic schistosomiasis and allowed the distinction of hepatosplenic schistosomiasis from viral or alcohol induced liver cirrhosis [18–20]. Splenic Gamna-Gandy bodies can also be observed in sickle cell anemia [21]. In endemic areas these sonographic findings are used as a noninvasive diagnostic test, replacing invasive liver biopsy [18]. Because of the thrombocytopenia and the altered coagulation tests (Table 1), liver biopsy and lumbar puncture were not carried out in the patient.

The nonspecific mild diffuse white matter hyperintensities seen in the MR-FLAIR-imaging of the patient, can be seen in SLE [22], in neurologically asymptomatic hepatosplenic schistosomiasis mansoni [23], and in other cerebral small vessel disease [24], and are not indicative of motor neuron disease. The antiphospholipid antibodies might have caused cerebral microangiopathy and favored blood brain barrier disruption and neuroimflammation [25]. Schistosome eggs can reach the CNS trough retrograde venous flow in the valveless Batson vertebral venous plexus, which connects the portal venous system and the venae cavae to the spinal cord and cerebral veins [2]. The gadolinium enhancement of the meninges at the vertebral level D4-D6 of the patient might have reflected an immunoreaction to schistosome eggs but do not explain the selective motor neuron disease. Spinal neuroschistosomiasis of Schistosoma mansoni usually manifests with lumbar pain, lower limb radicular pain, muscle weakness, sensory loss, and bladder dysfunction [2, 14]. The question was whether there was a link between hepatosplenic schistosomiasis and ALS.

3.2. Hepatosplenic Schistosmiasis mansoni and IL-17

In schistosomiasis the host mounts a pathogenic immune response against tissue-trapped parasite eggs. The CD4 T cell mediated granulomatous inflammation varies greatly in magnitude in humans and among mouse strains in experimental models [5]. Mouse strains which develop severe immunopathology show substantial Th17 as well as Th1 and Th2 cell responses; a solely Th2-polarized response is only observed in low-pathology strains such as the C57BL/6 mice [26]. The ability to mount pathogenic Th17 cell responses depends on the production of IL-23 and IL-1β by antigen presenting cells following recognition of egg antigens by pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) recognition receptors (PRRs) [27]. IL-1β contributes to the induction of Th17 cells and IL-23 is necessary for their maintenance and proliferation. Low-pathology C57BL/6 mice immunized subcutaneously with a soluble schistosome egg antigen preparation in complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA), that contains mainly heat killed M. tuberculosis, prior to and during infection with schistosomes, were shown to develop severe immunopathology. If in these mice the genes for p40 or p19, the two peptide components of IL-23 were knocked out, they became resistant to the induction of the severe immunopathology. Knocking out IL-12p35, a component of IL-12, did not prevent the severe schistosomiasis induced immunopathology. This indicates that an IL-17 producing T cell population, likely driven by IL-23, significantly contributes to the severe immunopatology in schistosomiasis [28]. T-helper 17 cells have been associated with pathology in Schistosoma haematobium-infected children [29].

In other experiments it was demonstrated that schistosome-specific IL-17 induction by dendritic cells from low-pathology C57BL/6 mice is normally inhibited by their induction of IL-10. In vitro, simultaneous stimulation of schistosome-exposed C57BL/6 dendritic cells with a heat-killed bacterium enables these cells to overcome IL-10 inhibition and to induce IL-17. This schistosome specific IL-17 was dependent on IL-6 production by the copulsed dendritic cells [30]. In vivo, coimmunisation of C57BL/6 animals with bacterial and schistosome antigens also resulted in schistosome-specific IL-17 production and this response was enhanced in the absence of IL-10 mediated immune regulation [30]. These experiments suggest that the balance of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines that determines the severity of pathology during schistosome infection can be influenced not only by the host and parasite, but also by concurrent bacterial or mycobacterial stimulation. On the other side, coinfection with intestinal nematodes was shown to reduce hepatic egg-induced immunopathology due to damping pathogenic Th17 cell responses by promoting regulatory mechanisms such as those afforded by alternatively activated macrophages and T regulatory cells [31]. It can be concluded that the pathological immune response to schistosome infection, represented by increased IL-17, is affected by multiple factors including intestinal parasite exposure, host variability, bacterial or mycobacterial infection, and commensal microbiota.

3.3. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and IL-17

There is compelling evidence that neuroinflammation is involved in the pathogenesis of ALS [32–34]. But neuroinflammation can exert both neuroprotective and neurodestructive effects, depending on the balance and timing of the different immune responses [32–34]. IL-17 was discovered to be a key player in the pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis (MS). P40 or p19 gene knockout mice are resistant to induction of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, the experimental model of multiple sclerosis [35]. As mentioned above, p40 and p19 are the two peptide components of IL-23, the cytokine necessary for maintenance and proliferation of Th17 cells [35].

Recently, increased levels of IL-17 have been found in the blood and in the CSF of the majority of patients affected by ALS [35–37]. But there are only few reports on IL-17 in ALS. Fiala and colleagues reported that the IL-17 serum level was increased above the highest observed level in control subjects of 40 pg/mL in 65% of 32 patients with ALS and in 4 of 4 patients with autoimmune disease [37]. In the described patient the IL-17 serum level was 672.2 pg/mL in the first blood sample, which was taken before treatment with praziquantel, and high dose corticosteroids were initiated. The normalization of the IL-17 values observed in the following three samples may be a consequence of treatment with high dose corticosteroids, with praziquantel, or a consequence of other unknown reasons. In vitro, mononuclear cells treated with superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) aggregates, misfolded SOD1, oxidized SOD1, or with mutant SOD1 produced IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-23, the cytokines that induce IL-17 [37, 38]. Stimulation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells by mutant SOD1 induced higher transcripts of IL-1α and IL-6, but lower transcripts of IL-10 in mononuclear cells of ALS patients as compared to controls [37]. This suggests that the vulnerability to ALS may be linked to the mode of the immune response. In the transgenic mouse model CNS-targeted production of IL-17 induces activation of astrocytes and microglia, microvascular pathology and enhances the neuroinflammatory response to systemic endotoxemia [39].

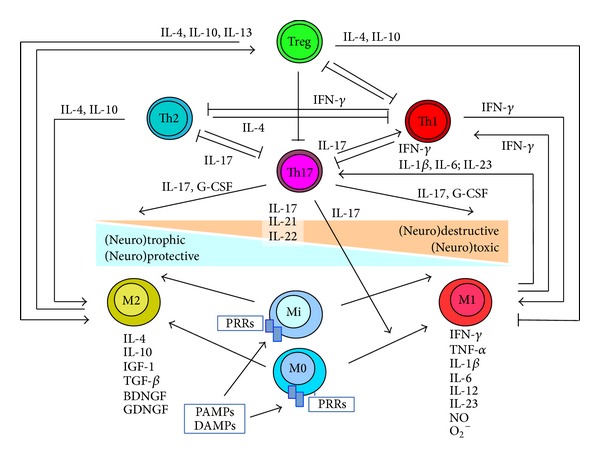

3.4. IL-17

IL-17, produced also by non-Th17 cells, functions as a first line of defense and represents a bridge between innate and adaptive immune response (for immune cell interaction see Figure 2) [40–43]. IL-17 protects the host from bacterial and fungal infections, particularly at the mucosal surfaces. IL-17 has also potent inflammatory potential and was shown to be the “superstar” in chronic inflammatory conditions [40–44]. Multiple pathogen associated molecular pattern (PAMP) recognition receptors (PRRs), for example, Toll-like receptors, NOD-like receptors, C-type lectins, on macrophages and other innate immune cells sense pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), xenobiotic substances, and endogenous “danger” associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) (e.g. aggregated, misfolded, oxidized, or mutant SOD1), and activate the immune response. Disease susceptibility or disease outcome may result from exposure to one or multiple infectious pathogens, xenobiotic substances (e.g. heavy metals), and/or endogenous “danger” associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) [44]. Polarization towards a proinflammatory immune response may lead to immunopathology, to infectious, allergic, or autoimmune disease (Figure 2). An already infection-arouse immune system may be more reactive to subsequent exogenous and endogenous immune stimulation [44].

Figure 2.

Simplified hypothetical model of immune cell interaction. ↑ = activation, induction; T = inhibition, reduction; BDNF = brain derived neurotrophic factor; DAMP = danger associated molecular pattern; G-CSF = granulocyte-colony stimutating factor; GDGF = glial-cell-derived neurotrophic factor; IGF-1 = insulin-like growth factor; IL = interleukin; Mi = microglia; M0 = nonactivated macrophages; M1 = classically activated macrophages; M2 = alternatively activated macrophages; PAMP = pathogen associated molecular pattern; PRRs = PAMP recognition receptors; and TGF-β = transforming growth factor-β.

Therefore it is possible that in the described patient the M. tuberculosis infection due to stimulation of PRRs contributed to the severe pathology of hepatosplenic schistosomiasis mansoni and that both M. tuberculosis and schistosome infection might have contributed to the development of ALS. Interestingly, the increased levels of IL-17 observed in individuals with latent M. tuberculosis infection compared to patients with tuberculosis were suggested to have a protective effect against tuberculosis [45]. The complete Freund's adjuvant, that consists of heat killed M. tuberculosis, has for long time been known to enhance the immune response. Other potential environmental triggers like vitamin D deficiency [46–48], a hypothetical loss of intestinal helminths after his transfer from Ghana to Italy [31], a hypothetical decreased induction of oral immune tolerance due to a reduced amount oral antigens [49], a possible induction of IL-17 due to changes of the intestinal flora [50–52], might have promoted a proinflammatory immune response polarization, thus contributing to ALS development in the described patient. Increased IL-17 levels have been detected in the circulation and tissues of human and murine lupus [53]. It was demonstrated that IL-17 promotes B cell survival and differentiation into antibody producing cells. Therefore IL-17 is suspected to promote humoral immunity against self-antigens [53]. It is possible that increased IL-17 has contributed to the development of autoantibodies detected in the described patient.

4. Conclusion

Because ALS is not a disease of infancy, it is probable that contributing factors have to accumulate over time and/or have to combine with each other in order to overcome the various physiologic compensation-, and repair-mechanisms, and cause disease. Besides the genetic background, environmental factors such as infections, xenobiotic substances, changes in the gut microbiota and vitamin D deficiency, may contribute to shift the balance of the immune response from a protective to a more destructive one [54]. Autoimmune disease associations with ALS raise the possibility of shared genetic or environmental risk factors [55]. Recent progress in immunology suggests that in the described patient an increased IL-17 level may have been a common pathogenic feature of the different diseases. If we consider ALS as a common outcome of a multitude of different risk factors, so in the future we have to learn to recognize and differentiate the various combinations of the contributing factors or subcategories of the disease. This will be a precondition for a combined therapeutic approach from different fronts and for interventions of immune modulation without abrogation of the protective part of the immune response. The reported clinical case suggests that the analytic methods of immunology, for example, measuring of cytokines and chemokines, will have to be introduced into daily clinical practice in order to progress towards better understanding and towards an effective treatment and prevention of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Pittella JEH. Neuroschistosomiasis. Brain Pathology. 1997;7(1):649–662. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1997.tb01080.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ross AG, McManus DP, Farrar J, Hunstman RJ, Gray DJ, Li Y. Neuroschistosomiasis. Journal of Neurology. 2012;259(1):22–32. doi: 10.1007/s00415-011-6133-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gryseels B, Polman K, Clerinx J, Kestens L. Human schistosomiasis. The Lancet. 2006;368(9541):1106–1118. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69440-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bica I, Hamer DH, Stadecker MJ. Hepatic schistosomiasis. Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. 2000;14(3):583–604. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(05)70122-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Larkin BM, Smith PM, Ponichtera HE, Shainheit MG, Rutitzky LI, Stadecker MJ. Induction and regulation of pathogenic Th17 cell responses in schistosomiasis. Seminars in Immunopathology. 2012;34(6):873–888. doi: 10.1007/s00281-012-0341-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gordon PH. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: an update for 2013 clinical features, pathophysiology, management and therapeutic trials. Aging and Disease. 2013;4(5):295–310. doi: 10.14336/AD.2013.0400295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ravits J, Appel S, Baloh RH, et al. Deciphering amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: what phenotype, neuropathology and genetics are telling us about pathogenesis. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Frontotemporal Degeneration. 2013;14(supplement 1):5–18. doi: 10.3109/21678421.2013.778548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turner MR, Hardiman O, Benatar M, et al. Controversies and priorities in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. The Lancet Neurology. 2013;12(3):310–322. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70036-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rao SD, Weiss JH. Excitotoxic and oxidative cross-talk between motor neurons and glia in ALS pathogenesis. Trends in Neurosciences. 2004;27(1):17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li YR, King OD, Shorter J, Gitler AD. Stress granules as crucibles of ALS pathogenesis. The Journal of Cell Biology. 2013;201(3):361–372. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201302044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim SM, Kim H, Lee JS, et al. Intermittent hypoxia can aggravate motor neuronal loss and cognitive dysfunction in ALS mice. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081808.e81808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luong KV, Nguyễn LT. Roles of vitamin D in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: possible genetic and cellular signaling mechanisms. Molecular Brain. 2013;6, article 16 doi: 10.1186/1756-6606-6-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conti F, Alessandri C, Sorice M, et al. Thin-layer chromatography immunostaining in detecting anti-phospholipid antibodies in seronegative anti-phospholipid syndrome. Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 2012;167(3):429–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2011.04532.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petri M, Orbai AM, Alarcón GS, et al. Derivation and validation of the systemic lupus international collaborating clinics classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2012;64(8):2677–2686. doi: 10.1002/art.34473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferrari TCA, Moreira PRR, Cunha AS. Clinical characterization of neuroschistosomiasis due to Schistosoma mansoni and its treatment. Acta Tropica. 2008;108(2-3):89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ridtitid W, Wongnawa M, Mahatthanatrakul W, Punyo J, Sunbhanich M. Rifampin markedly decreases plasma concentrations of praziquantel in healthy volunteers. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2002;72(5):505–513. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2002.129319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vazquez ML, Jung H, Sotelo J. Plasma levels of praziquantel decrease when dexamethasone is given simultaneously. Neurology. 1987;37(9):1561–1562. doi: 10.1212/wnl.37.9.1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manzella A, Ohtomo K, Monzawa S, Lim JH. Schistosomiasis of the liver. Abdominal Imaging. 2008;33(2):144–150. doi: 10.1007/s00261-007-9329-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lambertucci JR, Silva LCDS, Andrade LM, et al. Imaging techniques in the evaluation of morbidity in schistosomiasis mansoni. Acta Tropica. 2008;108(2-3):209–217. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bezerra ASDA, D'Ippolito G, Caldana RP, et al. Differentiating cirrhosis and chronic hepatosplenic schistosomiasis using MRI. The American journal of roentgenology. 2008;190(3):W201–207. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Piccin A, Rizkalla H, Smith O, et al. Composition and significance of splenic γ-Gandy bodies in sickle cell anemia. Human Pathology. 2012;43(7):1028–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2011.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Appenzeller S, Faria AV, Li ML, Costallat LTL, Cendes F. Quantitative magnetic resonance imaging analyses and clinical significance of hyperintense white matter lesions in systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Annals of Neurology. 2008;64(6):635–643. doi: 10.1002/ana.21483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manzella A, Borba-Filho P, Brandt CT, Oliveira K. Brain magnetic resonance imaging findings in young patients with hepatosplenic schistosomiasis mansoni without overt symptoms. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2012;86(6):982–987. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.11-0419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Debette S, Markus HS. The clinical importance of white matter hyperintensities on brain magnetic resonance imaging: systematic review and meta-analysis. British Medical Journal. 2010;341(7767) doi: 10.1136/bmj.c3666.c3666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horstman LL, Jy W, Bidot CJ, et al. Antiphospholipid antibodies: paradigm in transition. Journal of Neuroinflammation. 2009;6, article 3 doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-6-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rutitzky LI, Stadecker MJ. Exacerbated egg-induced immunopathology in murine Schistosoma mansoni infection is primarily mediated by IL-17 and restrained by IFN-γ . European Journal of Immunology. 2011;41(9):2677–2687. doi: 10.1002/eji.201041327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shainheit MG, Lasocki KW, Finger E, et al. The pathogenic Th17 cell response to major schistosome egg antigen is sequentially dependent on IL-23 and IL-1β . Journal of Immunology. 2011;187(10):5328–5335. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rutitzky LI, Bazzone L, Shainheit MG, Joyce-Shaikh B, Cua DJ, Stadecker MJ. IL-23 is required for the development of severe egg-induced immunopathology in schistosomiasis and for lesional expression of IL-17. The Journal of Immunology. 2008;180(4):2486–2495. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mbow M, Larkin BM, Meurs L, et al. T-helper 17 cells are associated with pathology in human schistosomiasis. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2013;207(1):186–195. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perona-Wright G, Lundie RJ, Jenkins SJ, Webb LM, Grencis RK, MacDonald AS. Concurrent bacterial stimulation alters the function of helminth-activated dendritic cells, resulting in IL-17 induction. Journal of Immunology. 2012;188(5):2350–2358. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bazzone LE, Smith PM, Rutitzky LI, et al. Coinfection with the intestinal nematode Heligmosomoides polygyrus markedly reduces hepatic egg-induced immunopathology and proinflammatory cytokines in mouse models of severe schistosomiasis. Infection and Immunity. 2008;76(11):5164–5172. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00673-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Appel SH, Beers DR, Henkel JS. T cell-microglial dialogue in Parkinson's disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: are we listening? Trends in Immunology. 2010;31(1):7–17. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Philips T, Robberecht W. Neuroinflammation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Role of glial activation in motor neuron disease. The Lancet Neurology. 2011;10(3):253–263. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70015-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Appel SH, Zhao W, Beers DR, Henkel JS. The microglial-motoneuron dialogue in ALS. Acta Myologica. 2011;30(1):4–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhu S, Qian Y. IL-17/IL-17 receptor system in autoimmune disease: mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Clinical Science. 2012;122(11):487–511. doi: 10.1042/CS20110496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rentzos M, Rombos A, Nikolaou C, et al. Interleukin-17 and interleukin-23 are elevated in serum and cerebrospinal fluid of patients with ALS: a reflection of Th17 cells activation? Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. 2010;122(6):425–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2010.01333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fiala M, Chattopadhay M, La Cava A, et al. IL-17A is increased in the serum and in spinal cord CD8 and mast cells of ALS patients. Journal of Neuroinflammation. 2010;7, article 76 doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-7-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu G, Fiala M, Mizwicki MT, et al. Neuronal phagocytosis by inflammatory macrophages in ALS spinal cord: inhibition of inflammation by resolvin D1. American Journal of Neurodegenerative Disease. 2010;1(1):60–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zimmermann J, Krauthausen M, Hofer MJ, Heneka MT, Campbell IL, Müller M. CNS-targeted production of IL-17A induces glial activation, microvascular pathology and enhances the neuroinflammatory response to systemic endotoxemia. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057307.e57307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miossec P, Korn T, Kuchroo VK. Interleukin-17 and type 17 helper T cells. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;361(9):888–898. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0707449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Khader SA, Gaffen SL, Kolls JK. Th17 cells at the crossroads of innate and adaptive immunity against infectious diseases at the mucosa. Mucosal Immunology. 2009;2(5):403–411. doi: 10.1038/mi.2009.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hirota K, Ahlfors H, Duarte JH, Stockinger B. Regulation and function of innate and adaptive interleukin-17-producing cells. EMBO Reports. 2012;13(2):113–120. doi: 10.1038/embor.2011.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bedoya SK, Lam B, Lau K, Larkin J., III Th17 cells in immunity and autoimmunity. Clinical and Developmental Immunology. 2013;2013:16 pages. doi: 10.1155/2013/986789.986789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hemdan NY, Abu El-Saad AM, Sack U. The role of T helper (TH )17 cells as a double-edged sword in the interplay of infection and autoimmunity with a focus on xenobiotic-induced immunomodulation. Clinical and Developmental Immunology. 2013;2013:13 pages. doi: 10.1155/2013/374769.374769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bandaru A, Devalraju KP, Paidipally P, et al. Phosphorylated STAT3 and PD-1 regulate IL-17 production and IL-23 receptor expression in Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. European Journal of Immunology. 2014;44(7):2013–2024. doi: 10.1002/eji.201343680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kamen DL, Tangpricha V. Vitamin D and molecular actions on the immune system: modulation of innate and autoimmunity. Journal of Molecular Medicine. 2010;88(5):441–450. doi: 10.1007/s00109-010-0590-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bruce D, Yu S, Ooi JH, Cantorna MT. Converging pathways lead to overproduction of IL-17 in the absence of vitamin D signaling. International Immunology. 2011;23(8):519–528. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxr045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ooi JH, Chen J, Cantorna MT. Vitamin D regulation of immune function in the gut: why do T cells have vitamin D receptors? Molecular Aspects of Medicine. 2012;33(1):77–82. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2011.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moling O, Mian P. Induction of oral tolerance as treatment or prevention of chronic diseases associatet with Chlamydia pneumoniae infection: hypothesis. Medical Science Monitor. 2003;9(5):HY15–HY18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ivanov II, Atarashi K, Manel N, et al. Induction of intestinal Th17 cells by segmented filamentous bacteria. Cell. 2009;139(3):485–498. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sczesnak A, Segata N, Qin X, et al. The genome of Th17 cell-inducing segmented filamentous bacteria reveals extensive auxotrophy and adaptations to the intestinal environment. Cell Host and Microbe. 2011;10(3):260–272. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Scher JU, Sczesnak A, Longman RS, et al. Expansion of intestinal Prevotella copri correlates with enhanced susceptibility to arthritis. eLife. 2013;2 doi: 10.7554/eLife.01202.e01202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shin MS, Lee N, Kang I. Effector T-cell subsets in systemic lupus erythematosus: update focusing on Th17 cells. Current Opinion in Rheumatology. 2011;23(5):444–448. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e328349a255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vojdani A. A potential link between environmental triggers and autoimmunity. Autoimmune Diseases. 2014;2014:18 pages. doi: 10.1155/2014/437231.437231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Turner MR, Goldacre R, Ramagopalan S, Talbot K, Goldacre MJ. Autoimmune disease preceding amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: an epidemiologic study. Neurology. 2013;81(14):1222–1225. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a6cc13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]