Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Reliable culturing methods for primary articular chondrocytes are essential to study the effects of loading and unloading on joint tissue at the cellular level. Due to the limited proliferation capacity of primary chondrocytes and their tendency to dedifferentiate in conventional culture conditions, long-term culturing conditions of primary chondrocytes can be challenging. The goal of this study was to develop a suspension culturing technique that not only would retain the cellular morphology but also maintain gene expression characteristics of primary articular chondrocytes.

METHODS

Three-dimensional culturing methods were compared and optimized for primary articular chondrocytes in the rotating wall vessel bioreactor, which changes the mechanical culture conditions to provide a form of suspension culture optimized for low shear and turbulence. We performed gene expression analysis and morphological characterization of cells cultured in alginate beads, Cytopore-2 microcarriers, primary monolayer culture, and passaged monolayer cultures using reverse transcription-PCR and laser scanning confocal microscopy.

RESULTS

Primary chondrocytes grown on Cytopore-2 microcarriers maintained the phenotypical morphology and gene expression pattern observed in primary bovine articular chondrocytes, and retained these characteristics for up to 9 days.

DISCUSSION

Our results provide a novel and alternative culturing technique for primary chondrocytes suitable for studies that require suspension such as those using the rotating wall vessel bioreactor. In addition, we provide an alternative culturing technique for primary chondrocytes that can impact future mechanistic studies of osteoarthritis progression, treatments for cartilage damage and repair, and cartilage tissue engineering.

Keywords: rotating wall vessel, chondrocytes, bioreactor, microcarrier, RWV

Introduction

Cartilage and bone tissues are constantly exposed to mechanical forces. Articular cartilage is exposed to a wide range of mechanical loads ranging from 5-6 megapascal (MPa) for walking gait and as high as 18MPa for other activities like running or jumping (6). When cartilage is exposed to higher loads that exceed physiological limits, the tissue may become injured and such injury may induce osteoarthritis (13). While moderate exercise has been shown to be beneficial for the synovial joint, excessive mechanical forces applied to the joint can disrupt homeostasis and trigger degradation of the cartilage tissue (22). Articular cartilage is the main load bearing tissue of the synovial joint, and mechanical forces are also important for the maintenance of the tissue. During space flight, astronauts experience a reduction in the applied mechanical force, which has a negative impact on load-bearing tissues including bone and skeletal muscle, and may also affect cartilage integrity and homeostasis (17).

Several ground analog experimental systems for space flight have been designed to study the effects of reduced mechanical load. The Rotating Wall Vessel (RWV) bioreactor, designed by NASA scientists at the Johnson Space Center, is a unique system in which to study the effects at the cell and molecular level (21). The RWV bioreactor consists of a cylindrical vessel that contains a flat silicone rubber gas transfer membrane for oxygenation (2,9). This system allows for solid body rotation around a horizontal axis, resulting in randomization of the gravitational vector, low shear stress, three-dimensional spatial freedom and oxygenation by diffusion of dissolved gases from the reactor chamber. During rotation of the vessel containing media and cells seeded on appropriate 3D carriers, the cells are exposed to a constant rotation, producing vector-averaged forces comparable with that of near-earth free fall orbit (9). The RWV system has been used by several investigators to study many different cell types including epithelial cells (19), Schwann cells (26), cells of the intervertebral disc (27), and trophoblast cells (28), as well as for tissue engineering studies (2) specifically for liver cells (8), bone cells (16,23), and elastic cartilage (25). To use the RWV bioreactor, cells must be in suspension. To study the effects of suspension culture, cells should not be subsequently centrifuged. Therefore, methods used to perform RNA and protein extraction must be performed quickly after taking the cells out of the vessel without centrifugation steps.

The aim of this study was to find a suspension culturing technique that would retain the characteristic cortical cytoskeletal arrangement and cell morphology and maintain gene expression patterns characteristic of primary articular chondrocytes. This study compares different culturing techniques used to grow primary chondrocytes extracted from bovine articular cartilage tissue in suspension using three commercially available microcarriers. Chondrocyte phenotype was assessed by RT-PCR and fluorescence microscopy and compared to primary chondrocytes freshly extracted from bovine cartilage tissue. The aim was to optimize culture conditions of primary articular chondrocytes for incubation in the RWV bioreactor to study the effects of low shear low turbulence conditions on chondrocytes.

Traditionally, chondrocytes are cultured either as a monolayer or in a three-dimensional environment using alginate beads or coated microspheres. A popular method for 3D culturing includes encapsulation of cells in alginate beads (1,14,15). This method allows the cells to retain their cortical actin cytoskeletal organization and to secrete and embed themselves in a cartilage-specific extracellular matrix. Chondrocytes can live in alginate beads for weeks without the need to passage the cells, and cells respond more accurately to chemical stimulation than those seeded as a monolayer culture (1). The cells can be recovered by dissociating the calcium-dependent cross-links in the alginate; however, this requires several washing and centrifugation steps. When experimental protocols require RNA isolation from these cells, several centrifugation steps are required to obtain a clean RNA sample. This presents a challenge when using the RWV bioreactor, because repeated washes and centrifugation steps expose the cells to excessive forces prior to cell lysis that may be experimentally incompatible with efforts to maintain the cells in the unique conditions afforded by the RWV bioreactor.

Another traditional method for 3D culture of primary articular chondrocytes involves the use of protein-coated microspheres such as polylactide (PLA) microspheres (7), or cytodex-1 (12) and cytodex-3 (24). These microcarriers are designed for anchorage-dependent cells, providing a protein surface for cells to adhere. One disadvantage of these beads is that they have limited surface area for the cells to bind, limiting the culturing period to a few days compared to the longer cultures possible with alginate beads. In this study, we used a protein-coated microcarrier with internal magnetic particles, which allows for easy recovery of the beads using a magnet, avoiding centrifugation steps. These commercially available microcarriers known as Global Eukaryotic Microcarriers (GEM) are available with specific protein coats including gelatin, fibronectin, collagen I, collagen IV, laminin, Matrigel and poly-D-lysine. These protein coats were evaluated in this study for primary articular chondrocytes.

The final microcarrier tested in this study was the cellulose macroporous Cytopore-2 microcarrier. Cytopore-2 allows the cells to adhere to the inner and outer surfaces of the bead. The microcarriers support a high cell density, are suitable for increasing growth for primary cells, and can protect against shear forces (3). In our hands, protein and RNA extraction was easily performed without washing or centrifugation steps, and therefore compatible with the RWV bioreactor. Results show that morphological and gene expression patterns were preserved when using the Cytopore-2 microcarriers for primary chondrocyte culture in the RWV bioreactor.

Methods

Experimental Procedures

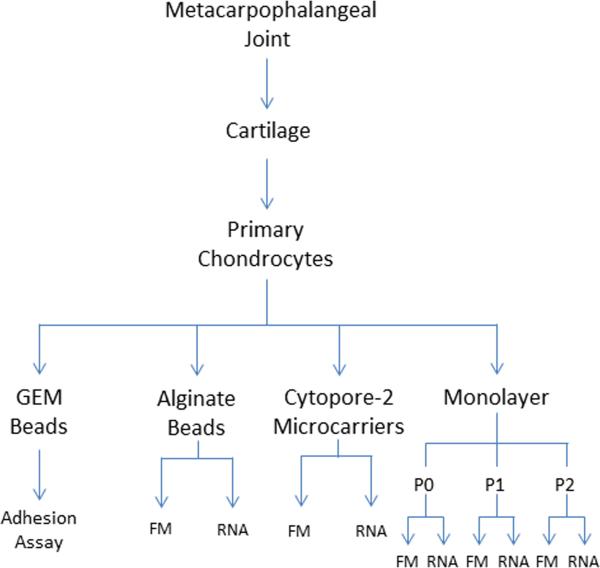

An overview of methods is shown in the flowchart in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Overview of the experimental design used in this study.

Primary chondrocytes were obtained from the metacarpophalangeal joint by aseptic technique and digestion using Pronase and collagenase sequentially. After filtering and washing chondrocytes, cells were counted and cultured either as a monolayer and monitored after successive passages (P0, P1, P2) or on a substrate that supported a 3D cell culture, Cytopore-2, alginate, or Global Eucaryotic Microcarriers (GEM) beads. Cells cultured on different substrates were analyzed for 1) adhesion to specific extracellular matrix molecules, 2) gene expression (RNA), and 3) cytoskeletal organization by fluorescence microscopy (FM).

Primary Chondrocyte Extraction and Culture

Hooves from 18-24 month old steers were obtained from a local butcher. Using aseptic technique, the articular cartilage was dissected from the exposed synovial capsule of the metacarpophalangeal joint. Cartilage explants were placed in 0.9% (w/v) sodium chloride until the end of the dissection. Tissue weight was measured, and the tissue was digested in a 0.4% pronase (w/v) (Sigma) solution prepared in serum-free Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium/F12 (DMEM/F12) containing 50μg/ml ascorbate-2-phosphate, 2% penicillin-streptomycin, and 0.1% gentamycin for one hour at 37°C in 5% CO2 environment with stirring. After pronase digestion, tissue explants were washed in serum-free medium twice and then digested in 0.025% collagenase overnight with stirring.

After collagenase digestion, the solution containing cells and residual tissue was strained through a 70 μm mesh to remove any undigested tissue, and cells were collected in a sterile 50 ml tube. Cells were collected by centrifugation for 10 minutes at 1,000 x g at 20°C and washed three times with serum-free medium. Between washes, chondrocytes were strained using a 40 μm mesh to isolate the chondrocytes from the remaining tissue. The cell pellet was resuspended in chondrocyte feeding medium (CFM), which was prepared in DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (Hyclone). Chondrocytes were counted using a hemocytometer and cultured using one of the culturing methods described in the following section -- monolayer culture, Global eukaryotic microcarriers, Cytopore-2 microcarriers, or alginate beads.

Monolayer Culture method

Chondrocytes were plated at high-density monolayer (2.0 x 106 cells/flask) in CFM on standard T-75 flasks for gene expression studies and on chamber slides (100,000 cells/well) for fluorescence microscopy. These cells were considered P0 for this study. Cells were passaged after three days of growth using 0.25% Trypsin-EDTA (Gibco) near full confluency to establish cell culture of passage one (P1). P1 cells reached confluency after three additional days, at which time cells were treated with trypsin-EDTA and passaged to establish passage two (P2).

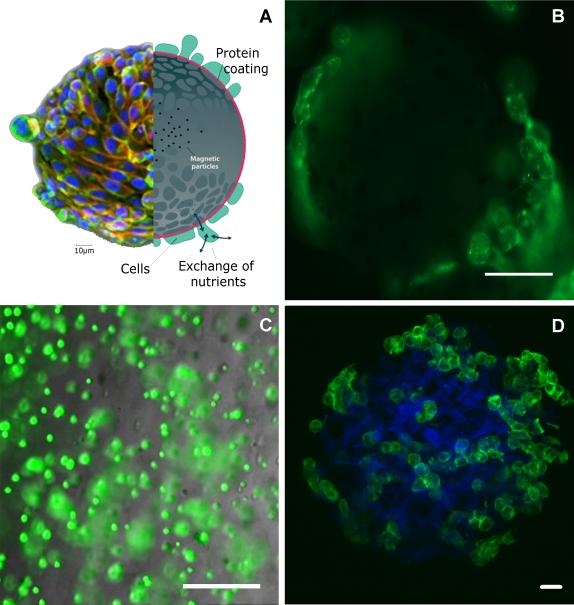

Global Eukaryotic Microcarriers culture method

Global Eukaryotic Microcarriers (GEM, Global Cell Solutions) are alginate microcarriers containing magnetic particles inside the bead, and coated with a molecular layer of protein covalently bound to the exterior surface (Figure 2A and 2B). The magnetic particles inside the beads allow for medium changes and collection of beads for protein/RNA extraction by using a magnet thus avoiding centrifugation steps. Several protein coated beads were compared in this study including collagen I, collagen IV, laminin, fibronectin and poly-D-lysine. An adhesion assay was performed to determine which protein coating was optimal for the chondrocytes. Following manufacturer's instructions, 50μL of each GEM bead was added to a 24-well plate and washed with media to remove storage buffer. Cell suspension (500μL containing 100,000 cells) and 450 μl of medium were added to each well. Cells were allowed to adhere to beads for 24 hours. To determine percentage of cells that did not adhere, a magnet was used to retain attached cells at the bottom of the well and 250 μL of medium was removed. Cells in the medium were counted with a hemocytometer.

Figure 2. Three dimensional culturing techniques.

The RWV bioreactor requires suspension cultures. A. Global Eukaryotic Microcarriers (GEM), magnetic beads coated with protein to create a substrate for the cells to attach (image adapted from Global Cell Solutions website). B. Fluorescence image of chondrocytes (green=phalloidin bound to the actin cytoskeleton) seeded on GEM beads. C. Epifluorescence image of chondrocytes encapsulated in an alginate bead (green=calcein-AM). D. Confocal image of a Cytopore-2 microcarrier (blue) seeded with chondrocytes (green= phalloidin bound to the actin cytoskeleton).Scale bar dimensions: B. 50μm; C. 100 μm; D. 20 μm.

Alginate Bead Culture method

Isolated chondrocytes were resuspended in 1.2% (w/v) alginate solution in 0.9% sodium chloride at a concentration of 4x106 cells/ml and transferred to a sterile 5 ml syringe. The alginate/cell mix was then passed through a 22-gauge needle into sterile 102 mM calcium chloride solution while slowly stirring. Beads were incubated in the calcium chloride solution for ten minutes and then washed twice with 0.9% (w/v) sodium chloride. Beads were then transferred to a culture dish containing CFM. To terminate experiments, alginate beads were dissolved by chelation of calcium in a dissociation solution containing 0.055M sodium citrate and 0.15 M NaCl at pH 6.8 to recover the cells. Removal of alginate for successful RNA extraction required at least five washes in PBS with centrifugation periods of 5 minutes at 1,000 x g between washes (Figure 2C).

Cytopore-2 Culture method

Cytopore-2 microcarriers (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) were rehydrated in PBS (0.5 mg Cytopore/ml PBS) and then autoclaved for sterilization. Microcarriers were then washed with PBS and resuspended in CFM for conditioning overnight prior to cell seeding. Chondrocytes were added to the microcarriers at a ratio of 400,000 cells per 1 mg of Cytopore-2, and cells were allowed to associate with the microcarrier for 24 hours at 37°C and 5% CO2 before initiating experiments in the RWV bioreactor. The macroporous microcarrier beads made of cellulose have a surface topology compatible with establishment of a 3D culture environment (Figure 2D).

Fluorescence Microscopy

Cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde for 30 minutes at 4°C and incubated with 1% bovine serum albumin (Sigma) in PBS for 30 minutes at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. Cells were then permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 minutes at room temperature and then washed twice with PBS. The actin cytoskeleton was stained using AlexaFluor-488 phalloidin (AF488-phalloidin) (Invitrogen) overnight at 4°C (1:150 dilution in PBS) and then washed twice with PBS.

After the last wash, cells were resuspended in mounting media containing nuclear stain diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), and visualized using a Zeiss LSM 510 Meta system combined with the Zeiss Axiovert Observer Z1 inverted microscope and ZEN 2009 imaging software (Carl Zeiss, Inc., Thornwood, NY). Images were acquired utilizing a 63X Plan-Apochromat oil-immersion objective (NA1.4), a diode laser (405nm) with a band pass of 420-480nm for the detection of DAPI and an Argon laser (488 nm) with an emission band pass of 505-530nm for the detection AF488-phalloidin.

RNA Extraction and Reverse Transcription-PCR

RNA was obtained from cells maintained in monolayer prior to passaging (P0), after one passage (P1), and after two passages (P2) using Trizol reagent (Life Technologies). Chondrocytes seeded on Cytopore-2 microcarriers were transferred to a sterile 15 ml conical tube until all microcarriers settled to the bottom of the tube. Medium was removed and Trizol reagent was added to the cells bound to the microcarriers. Cells encapsulated in alginate beads were released from the alginate in 10 ml of dissociation buffer containing 0.055M sodium citrate and 0.15 M NaCl at pH 6.8 for ten minutes. Released chondrocytes were then centrifuged and washed five times with PBS before adding Trizol reagent to the cell pellet. All samples were incubated in Trizol for 3 hours at room temperature.

After incubation, 200 μl of chloroform was added to each 1 ml of Trizol/cell mixture and centrifuged for 15 minutes at 12,000 x g at 4°C. The aqueous phase was collected and 0.5 ml of 91% isopropanol was added to precipitate the RNA during a 10 minute incubation at room temperature. RNA was centrifuged for 10 minutes at 12,000 x g at 4°C and pellet was washed in 1 ml of 4M lithium chloride. RNA was centrifuged again for 10 minutes at 12,000 x g at 4°C. Pellet was washed in 1 ml of 75% ethanol and centrifuged for 10 minutes at 12,000 x g at 4°C. Finally, the pellet was allowed to air dry for 10 minutes at room temperature. The pellet was resuspended in 20 μl of DEPC-treated water and the concentration was determined by spectroscopy. Gene expression was assessed by RT-PCR using the primers shown in Table I.

Table I.

Primer sequences used in this study

| Gene | Forward Sequence | Reverse Sequence | Tm | Base pair |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Col1a1 | TGGACCTCAAGGTATTGCTGGACA | ATTGGCATCATCAGCCCGGTAGTA | 60 | 820 |

| Col2a1 | AACTGATGGAATCCCTGGAGCCAA | TCACCATCTTTGCCAGGAAGACCT | 60 | 678 |

| Aggrecan | TTGGTGGAATCTGTAACCCAGGCT | TCATGGAAGGTGGAGGTGGTTTCA | 60 | 581 |

| Beta Actin | GAATCCTGCGGCATTCACGAAACT | TGTACAATCAAGTCCTCGGCCACA | 60 | 550 |

Results

Primary articular chondrocytes detached from protein-coated beads in RWV bioreactor

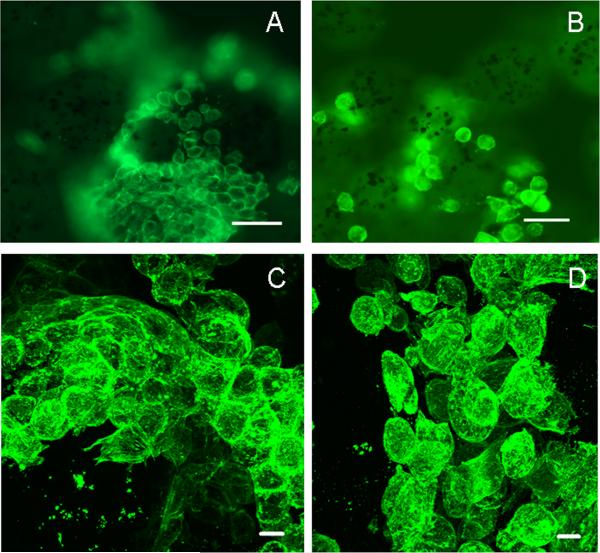

Global Eukaryotic Microcarriers (GEM) are similar to other available microcarriers such as cytodex-1 and 3, and polylactide (PLA) microspheres in the sense that the cells depend on anchorage to the protein coat. There are several GEM protein-coated microcarriers available including collagen I, collagen IV, laminin, basement membrane, fibronectin and poly-D-lysine. An adhesion assay was performed to determine which protein coat was optimal for the primary bovine chondrocytes. The majority of chondrocytes adhered to most protein coatings during 24 hours of growth (Table II). However, after two days in the RWV bioreactor, the cells detached from the protein coating of the GEM beads (Figure 3). It was difficult to recover the cells and therefore, while GEM beads may be useful for growing primary chondrocytes in suspension under normal gravity conditions, they may present challenges when using the RWV bioreactor.

Table II.

Cell adhesion study in normal gravity with primary bovine chondrocytes

| Protein Coating | % Adhered | % Non-adhered |

|---|---|---|

| Poly-D-Lysine | 84 | 16 |

| Matrigel | 90 | 10 |

| Collagen I | 94 | 6 |

| Collagen IV | 89 | 11 |

| Fibronectin | 82 | 18 |

| Laminin | 93 | 7 |

Primary chondrocytes adhered to the greatest extent to collagen I (94%), laminin (93%), and Matrigel (90%).

Figure 3. Chondrocytes detached from protein-coated beads during culture in RWV bioreactor.

A. Chondrocytes attached to protein-coated magnetic bead in conventional culturing conditions by epifluorescence microscopy. B. Chondrocytes detached from same beads as shown in A, but under culture conditions using the RWV bioreactor. C. Chondrocytes shown in A at higher magnification. D Chondrocytes shown in B. at higher magnification. Scale bar dimensions: A. and B. 50μm; C. and D. 20 μm.

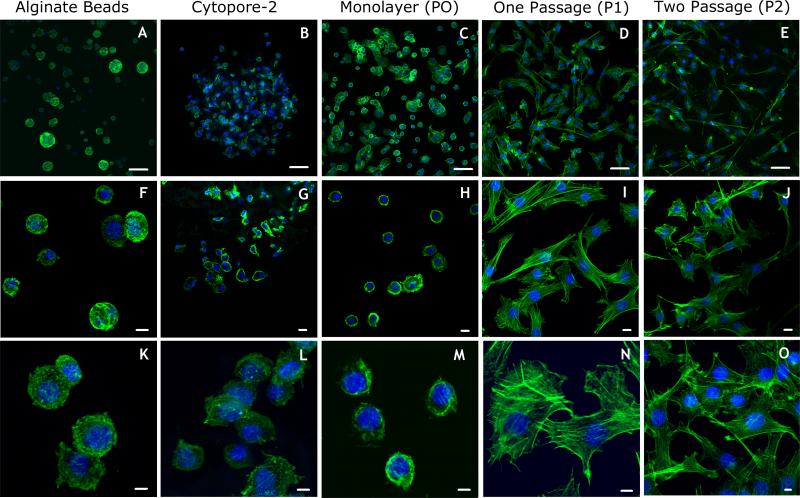

Changes in cytoskeletal morphology of primary articular chondrocytes under specific culture conditions

Chondrocytes may lose the cortical actin distribution and develop cellular processes extending from the plasma membrane, becoming more fibroblast-like under certain culturing conditions (11,18). Interestingly, a similar morphological change has been associated in osteoarthritic chondrocytes (5). Importantly, these morphological changes have been associated with changes in gene expression, including decrease in collagen type II, SOX 9 and aggrecan expression, with concomitant increase in collagen type I expression as the cells become more fibroblast-like (18).

A suspension culturing technique that retains the cortical cytoskeletal cell morphology, and also maintains gene expression characteristic of primary chondrocytes is essential. Chondrocytes seeded in alginate beads and Cytopore-2 microcarriers retained a round cellular morphology observed in nonpassaged primary chondrocyte cultures (P0), as observed using AlexaFluor488-phalloidin to label the actin cytoskeleton. As the monolayer cultures were passaged from P0 to P1 and P2, the cells developed elongated processes similar to fibroblasts (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Primary bovine chondrocyte morphology using different culture techniques.

A. Chondrocytes seeded in alginate. B. Chondrocytes seeded on Cytopore-2 microcarriers. C. Primary chondrocytes plated on tissue culture plastic for three days as a monolayer (P0). D. Chondrocytes from C, after trypsin-EDTA treatment and passage onto new tissue culture plastic, grown for three additional days (P1). E. Chondrocytes from D, after an additional trypsin-EDTA treatment and passaged again onto new tissue culture plastic, grown for three additional days (P2). F. and K. Higher magnifications of cells shown in A. G. and L. Higher magnification of cells shown in B. H. and M. Higher magnification of cells shown in C. I. and N. Higher magnification of cells shown in D. J. and O. Higher magnification of cells shown in E. All cells were fixed and stained with AlexaFluor488-phalloidin (green=phalloidin bound to the actin cytoskeleton) to observe changes in the cytoskeletal and cellular morphology. Typical cortical localization of actin and morphology of primary chondrocytes was retained in alginate beads and Cytopore-2 microcarriers as well as chondrocytes prior to trypsin-EDTA treatment and passage (see A, B, and C). Cells became more fibroblast-like in subsequent passages, consistent with dedifferentiation. Scale bar dimensions: A-E, 50 μm; F-J, 10 μm; K-O, 5 μm.

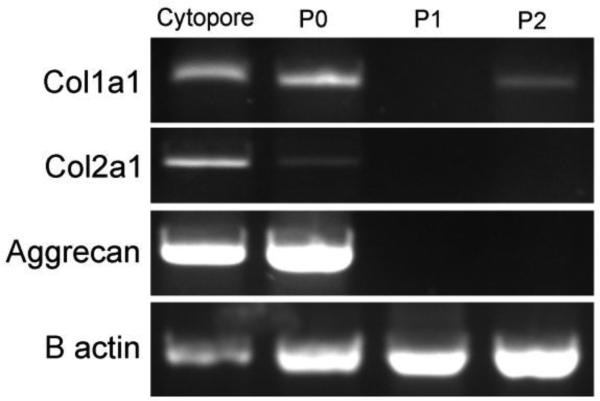

Gene expression patterns of chondrocytes seeded on Cytopore-2 microcarriers was compared to non-passaged cells (P0) as well as cells after 1 and 2 passages (P1 and P2 respectively). Gene expression of cells seeded on Cytopore-2 microcarriers was similar to those of non-passaged primary articular chondrocytes, suggesting that the use of Cytopore-2 microcarriers provides a reliable alternative technique for culturing primary articular chondrocytes in suspension.

We analyzed gene expression to compare the characteristics of cells in alginate beads and on Cytopore-2 microcarriers. To extract RNA from the chondrocytes encapsulated in alginate beads, the alginate was treated with citrate to chelate the calcium, then washed five times to completely remove the alginate. Gene expression patterns of cells in alginate were similar to cells on Cytopore-2 microcarriers and non-passage cells (Figure 5).

Figure 5. RT-PCR.

RNA was extracted from chondrocytes cultured on Cytopore-2 microcarriers or monolayers before passaging with trypsin-EDTA (P0) or after a single (P1) or double passage (P2). Col1a1, Col2a1, aggrecan, and beta actin were detected by RT-PCR. Characteristic gene expression of primary chondrocytes was retained in chondrocytes seeded on Cytopore-2 microcarriers. Chondrocytes grown in a monolayer with no passages (P0) showed a slight decrease in Col2a1 signal while cells in P1 and P2 lost expression of the characteristic markers of chondrocytes.

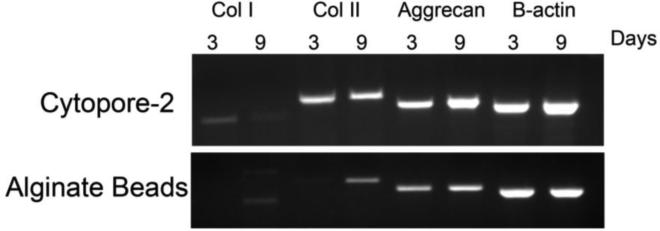

We compared the RNA yield and purity between chondrocytes seeded on Cytopore-2 microcarriers and alginate beads. The final yield for cells seeded on Cytopore-2 microcarriers after 3 and 9 days was 350 and 1350 ng/μl respectively, and for cells in alginate beads the concentrations were 40 and 200 ng/μl. RT-PCR was performed to assess gene expression of collagen type I, collagen type II and aggrecan expression after 3 and 9 days in culture (Figure 6). Cells seeded on Cytopore-2 microcarriers had higher collagen II expression after 3 days when compared to cells in alginate beads, and higher aggrecan expression after 3 and 9 days. This data suggests that bovine primary articular chondrocytes retain their cortical morphology when seeded on Cytopore-2 microcarriers, and express chondrocyte-specific genes throughout Cytopore-2 culture when compared to cells grown in alginate beads. Cells cultured on Cytopore-2 microcarriers were easier to work with for protein and RNA extractions after culturing in the RWV bioreactor.

Figure 6. RT-PCR of chondrocytes grown in alginate beads vs. Cytopore-2 microcarriers for 3 and 9 days.

RNA extracted from chondrocytes cultured in alginate beads and Cytopore-2 microcarriers after 3 days and 9 days in culture. Expression of Col1a1, Col2a1, aggrecan, and beta actin were detected by RT-PCR at 3 and 9 days in culture in Cytopore-2 microcarriers and alginate beads.

Discussion

Culturing primary chondrocytes for extended periods of time is a challenge due to the limited proliferation capacity and tendency to dedifferentiate after passages in monolayer. Three-dimensional methods are preferred for long-term cultures and tissue engineering, and as a result, several novel techniques have been developed over the past few years. Culturing cells in a RWV bioreactor brings an additional challenge to researchers as RWV bioreactor cultures need to be maintained in suspension. RNA and protein extractions must be performed shortly after removal of the cells from the RWV bioreactor, and cells should not experience forces of centrifugation after culturing in the RWV bioreactor.

Our goal for this study was to compare several three-dimensional culturing techniques for primary articular chondrocytes that would be compatible with protein and RNA extraction for studies of cells grown in the RWV bioreactor. We used two different commercially available microcarriers: GEM magnetic beads and Cytopore-2 microcarriers, as well as alginate beads, which encapsulate thousands of cells inside of an individual bead. The GEM beads are protein-coated microcarriers that allow the cells to anchor to the bead surface, similar to other commercially available microcarriers such as cytodex and PLA microbeads. They have small magnetic particles inside the beads, which allows for easy collection of the beads using a magnet, avoiding centrifugation steps. Primary chondrocytes anchored to most of the protein coats available, but after incubating the cells in the RWV bioreactor, most of the cells detached from the protein surface. Therefore the GEM beads may be a useful method for suspension cultures of primary chondrocytes, however, not for cells grown in the RWV bioreactor.

Alginate beads have been traditionally used for many years as a three-dimensional culturing technique for primary chondrocytes. Cells can be maintained inside alginate for several weeks without losing the chondrocyte phenotype. However, in order to extract protein or RNA, the beads must be dissolved to recover the cells. Alginate interferes with the RNA extraction, so several washes are required to obtain a clean RNA extraction, and residual alginate can decrease RNA yield. Large polysaccharide fragments found in alginate that may be present after sample digestion can entrap nucleic acids physically during centrifugation and may be discarded during phase separation, thus leading to a low yield (20). Moreover, small polysaccharide fragments can partition into the aqueous phase during phase separation and co-precipitate with RNA in the RNA precipitation step, which interferes with downstream applications (4, 10). Alginate beads represent a good method for long term culture of primary chondrocytes and for tissue engineering; however, alginate is not ideal for studies in the RWV bioreactor.

The porous Cytopore-2 microcarriers were the preferred method for culture of primary articular chondrocytes in the RWV bioreactor in our hands. Cytopore-2 may be a promising novel technique for tissue engineering applications as well. Cytopore-2 microcarriers are composed of cellulose macroporous matrix that allows nutrients to reach the cells and also provides the cells with protection from shear forces. The macroporosity of the microcarriers provide a large surface area to volume, which allows for high density and long-term cultures. Protein and RNA extraction were facilitated by the ease of handling of cells seeded on the Cytopore-2 beads. Additionally, cytoskeletal morphological characteristics were maintained while associated with the Cytopore-2 microcarriers.

This study optimized suspension culture techniques for bovine primary articular chondrocytes for use in the RWV bioreactor. Our findings show that Cytopore-2 microcarriers were the optimal culturing technique for use in the RWV bioreactor.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the National Space Biomedical Research Institute through NASA NCC9-58, Idaho Space Grant Consortium, NASA (NNX10AN29A), the Arthritis Foundation, the NIH/NIAMS Grants R01AR047985 and K02AR48672, NIH/NCRR Grant P20RR016454, NIH/NIGMS P20GM103408, the National Science Foundation (0619793, 0923535), M. J. Murdock Charitable Trust, Idaho State Board of Education Higher Education Research Council for support of the Musculoskeletal Research Institute.

Footnotes

Authors have no financial or commercial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ab-Rahim S, Selvaratnam L, Raghavendran HR, Kamarul T. Chondrocyte-alginate constructs with or without TGF-beta1 produces superior extracellular matrix expression than monolayer cultures. Mol Cell Biochem. 2013 Apr;376(1-2):11–20. doi: 10.1007/s11010-012-1543-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barzegari A, Saei AA. An update to space biomedical research: tissue engineering in microgravity bioreactors. Bioimpacts. 2012;2(1):23–32. doi: 10.5681/bi.2012.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Connelly JT, Vanderploeg EJ, Levenston ME. The influence of cyclic tension amplitude on chondrocyte matrix synthesis: experimental and finite element analyses. Biorheology. 2004;41(3-4):377–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dellacorte C. Isolation of nucleic acids from the sea anemone Condylactis gigantea (Cnidaria: Anthozoa). Tissue Cell. 1994;26(4):613–9. doi: 10.1016/0040-8166(94)90013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gefen O, Gabay C, Mumcuoglu M, Engel G, Balaban NQ. Single-cell protein induction dynamics reveals a period of vulnerability to antibiotics in persister bacteria. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105(16):6145–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711712105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hodge WA, Fijan RS, Carlson KL, Burgess RG, Harris WH, Mann RW. Contact pressures in the human hip joint measured in vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1986;83(9):2879–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.9.2879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hong Y, Gao C, Xie Y, Gong Y, Shen J. Collagen-coated polylactide microspheres as chondrocyte microcarriers. Biomaterials. 2005;26(32):6305–13. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ishikawa M, Sekine K, Okamura A, Zheng YW, Ueno Y, Koike N, et al. Reconstitution of hepatic tissue architectures from fetal liver cells obtained from a three-dimensional culture with a rotating wall vessel bioreactor. J Biosci Bioeng. 2011;111(6):711–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2011.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jin L, Feng G, Reames DL, Shimer AL, Shen FH, Li X. The effects of simulated microgravity on intervertebral disc degeneration. Spine J. 2013;13(3):235–42. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2012.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kansal R, Kuhar K, Verma I, Gupta RN, Gupta VK, Koundal KR. Improved and convenient method of RNA isolation from polyphenols and polysaccharide rich plant tissues. Indian J Exp Biol. 2008;46(12):842–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ludwiczek O, Vannier E, Moschen A, Salazar-Montes A, Borggraefe I, Fabay C, et al. Impaired counter-regulation of interleukin-1 by the soluble IL-1 receptor type II in patients with chronic liver disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008;43(11):1360–5. doi: 10.1080/00365520802179925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malda J, van Blitterswijk CA, Grojec M, Martens DE, Tramper J, Riesle J. Expansion of bovine chondrocytes on microcarriers enhances redifferentiation. Tissue engineering. 2003;9(5):939–48. doi: 10.1089/107632703322495583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakamura S, Arai Y, Takahashi KA, Terauchi R, Ohashi S, Mazda O, et al. Hydrostatic pressure induces apoptosis of chondrocytes cultured in alginate beads. J Orthop Res. 2006;24(4):733–9. doi: 10.1002/jor.20077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakashima K, Nakatsuka K, Yamashita K, Kenichi K, Taro H. An in vitro model of cartilage degradation by chondrocytes in a three-dimensional culture system. Int J Biomed Sci. 2012;8(4):249–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakatsuka K, Kurita K, Hayakawa T, Nakashima K, Yamashita K, Hoshino T, et al. Histomorphometric Evaluation of Cartilage Degradation using Rabbit Articular Chondrocytes Cultured in Alginate Beads -Effects of Hyaluronan. Int J Biomed Sci. 2010;6(2):103–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nishi M, Matsumoto R, Dong J, Uemura T. Engineered bone tissue associated with vascularization utilizing a rotating wall vessel bioreactor. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2013;101(2):421–7. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Niu H-J, Wang Q, Wang Y-X, Li A, Sun L-W, Yan Y, et al. The study on the mechanical characteristics of articular cartilage in simulated microgravity. Acta Mech Sin. 2012;28(5):1488–93. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pongratz C, Yazdanpanah B, Kashkar H, Lehmann MJ, Krausslich HG, Kronke M. Selection of potent non-toxic inhibitory sequences from a randomized HIV-1 specific lentiviral short hairpin RNA library. PloS one. 2010;5(10):e13172. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Radtke AL, Herbst-Kralovetz MM. Culturing and applications of rotating wall vessel bioreactor derived 3D epithelial cell models. J Vis Exp. 2012;(62) doi: 10.3791/3868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salter MG, Conlon HE. Extraction of plant RNA. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;362:309–14. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-257-1_21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwarz RP, Goodwin TJ, Wolf DA. Cell culture for three-dimensional modeling in rotating-wall vessels: an application of simulated microgravity. Journal of tissue culture methods : Tissue Culture Association manual of cell, tissue, and organ culture procedures. 1992;14(2):51–7. doi: 10.1007/BF01404744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharma L, Chang A. Overweight: advancing our understanding of its impact on the knee and the hip. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(2):141–2. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.059931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Song K, Wang H, Zhang B, Lim M, Liu Y, Liu T. Numerical simulation of fluid field and in vitro three-dimensional fabrication of tissue-engineered bones in a rotating bioreactor and in vivo implantation for repairing segmental bone defects. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2013;18(2):193–201. doi: 10.1007/s12192-012-0370-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Surrao DC, Khan AA, McGregor AJ, Amsden BG, Waldman SD. Can microcarrier-expanded chondrocytes synthesize cartilaginous tissue in vitro? Tissue engineering Part A. 2011;17(15-16):1959–67. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2010.0434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takebe T, Kobayashi S, Kan H, Suzuki H, Yabuki, Mizuno M, et al. Human elastic cartilage engineering from cartilage progenitor cells using rotating wall vessel bioreactor. Transplantation proceedings. 2012;44(4):1158–61. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2012.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Valmikinathan CM, Hoffman J, Yu X. Impact of Scaffold Micro and Macro Architecture on Schwann Cell Proliferation under Dynamic Conditions in a Rotating Wall Vessel Bioreactor. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2011;31(1):22–9. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang X, Wang D, Hao J, Gong M, Arlet V, Balian G, et al. Enhancement of matrix production and cell proliferation in human annulus cells under bioreactor culture. Tissue engineering Part A. 2011;17(11-12):1595–603. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2010.0449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zwezdaryk KJ, Warner JA, Machado HL, Morris CA, Honer zu Bentrup K. Rotating cell culture systems for human cell culture: human trophoblast cells as a model. J Vis Exp. 2012;(59) doi: 10.3791/3367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]