Supplemental Digital Content is Available in the Text.

This study focuses on the existing public health workforce, with the results aiming at informing the revisions public health academic programs and standards are experiencing nationally.

Keywords: public health departments, workforce, workforce development

Abstract

Context:

Discipline-specific workforce development initiatives have been a focus in recent years. This is due, in part, to competency-based training standards and funding sources that reinforce programmatic silos within state and local health departments.

Objective:

National leadership groups representing the specific disciplines within public health were asked to look beyond their discipline-specific priorities and collectively assess the priorities, needs, and characteristics of the governmental public health workforce.

Design:

The challenges and opportunities facing the public health workforce and crosscutting priority training needs of the public health workforce as a whole were evaluated. Key informant interviews were conducted with 31 representatives from public health member organizations and federal agencies. Interviews were coded and analyzed for major themes. Next, 10 content briefs were created on the basis of priority areas within workforce development. Finally, an in-person priority setting meeting was held to identify top workforce development needs and priorities across all disciplines within public health.

Participants:

Representatives from 31 of 37 invited public health organizations participated, including representatives from discipline-specific member organizations, from national organizations and from federal agencies.

Results:

Systems thinking, communicating persuasively, change management, information and analytics, problem solving, and working with diverse populations were the major crosscutting areas prioritized.

Conclusions:

Decades of categorical funding created a highly specialized and knowledgeable workforce that lacks many of the foundational skills now most in demand. The balance between core and specialty training should be reconsidered.

Since July 2008, 91% of all state health agencies have experienced job losses through a combination of layoffs and attrition.1 Between 2007 and 2010, 10 000 state jobs have been lost in central, local, and regional offices from a total of 110 000; between 2010 and 2013, staffing remained relatively constant in aggregate nationally, despite increased demand for services.1,2 State health agencies are actively recruiting for only approximately 28% of vacant positions, and 25% of the state health agency workforce is projected to be eligible for retirement in fiscal year 2016.2 The impact of budget reductions is compounded by the uncertainty for the future of public health's collective roles and responsibilities due to the passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, as well as development of national standards for public health department accreditation. These initiatives are reshaping the skillset needed by the public health workforce. An integrative approach to protecting and promoting the health status of the individual and the community is now a systemwide focus requiring crosscutting skills that complement discipline-specific expertise.3

The 1988 Institute of Medicine Report, The Future of Public Health, called for broad, crosscutting skills and competencies for public health practitioners.4–7 In response, core competencies were developed for public health generally and for specific disciplines within the field of public health (eg, epidemiology, public health nursing, or preparedness) or specific degree types (eg, the master of public health).8–13 These competency-based models are used within academia and health agencies.14–16 Their proliferation has created expansive lists of needed skills, from which discerning priorities have proven difficult.17 In the past decade, scholars, practitioners, and policy makers alike have continued to call for a continued focus on systemwide workforce development.5–7,17–25

Public health worker organizations routinely identify workforce development as a priority.26 Surveys conducted by these membership organizations provide information about specific segments of the public health workforce.27–29 However, each organization collects information with different methods, at different times, and for different purposes. Therefore, the existing data cannot be easily combined to build a comprehensive understanding of the development and training needs of the entire public health workforce. Moreover, the skills needed most urgently have not been prioritized.

Public health workforce development reflects the multiple disciplines constituting the field of public health. Competency definition and competency-based training in the last decade attempted to address the deficit of crosscutting training in public health.7 However, systemwide assessment of the workforce needs remains significantly outdated.7,21,30

This project challenged national leadership groups representing the specific disciplines within public health to look beyond their discipline-specific priorities to assess the priorities, needs, and characteristics of the governmental public health workforce.

Methods

We undertook a 3-part mixed-methods approach that included (1) key informant interviews, (2) small group work to develop content briefs for a prioritization process, and (3) an in-person prioritization meeting. For the key informant interview stage, we conducted semistructured interviews with participating organizations to identify challenges, needs, and priorities with respect to public health workforce development. The semistructured key informant interviews identified challenges, needs, and priorities for public health workforce development in the governmental sector. Ten areas were consistently mentioned as priorities in workforce development. Next, interview participants were separated into 10 groups and asked to develop a content brief for 1 of the 10 priority areas they had identified. These briefs were distributed prior to, and presented at, the in-person prioritization meeting. In April 2013, the top priorities were identified and prioritized. The key informant interview and the in-person consensus-building process occurred around professional assessment of the needs of the workforce; therefore, institutional review board approval was not necessary.

Participants

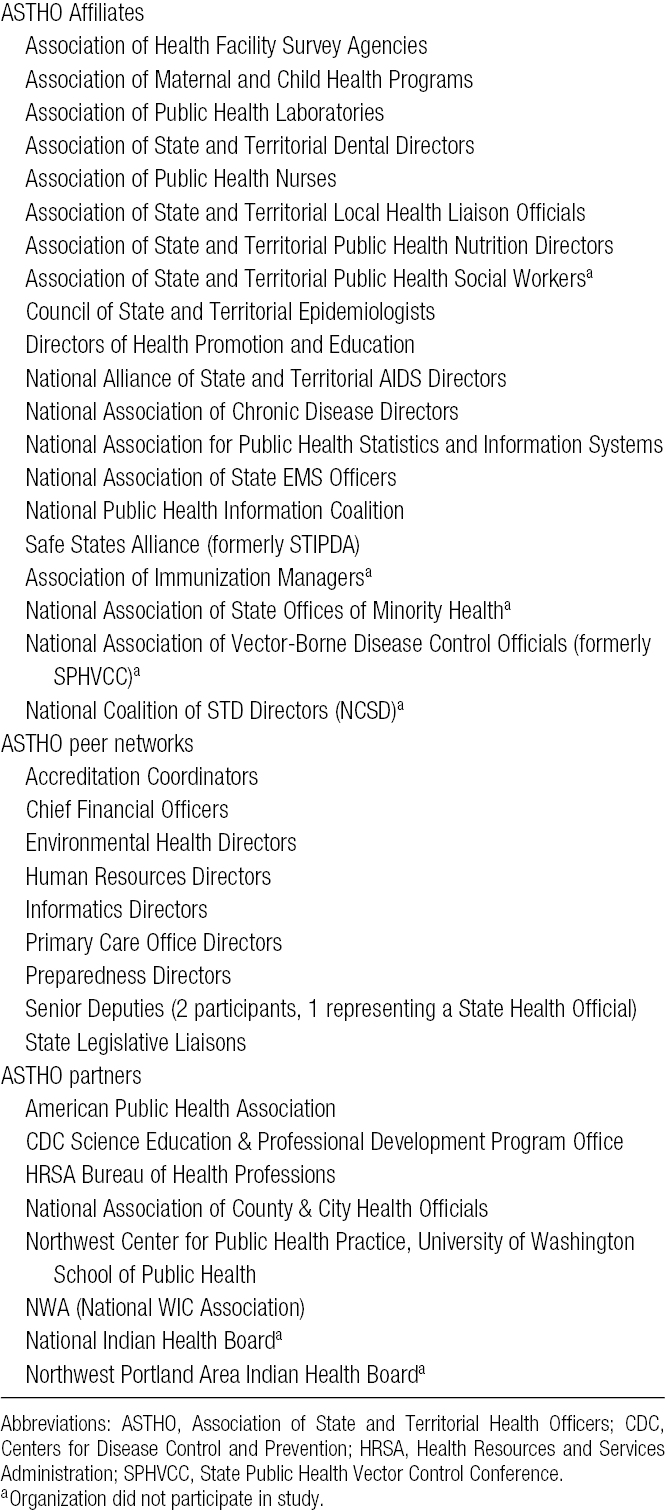

Thirty-seven organizations/groups were asked to participate (Table 1)—20 Association of State and Territorial Health Officers (ASTHO) affiliates, 9 peer networks, and 8 partner organizations and agencies. The ASTHO affiliates are independent 501(c)3 or 501(c)6 organizations that represent key workforce segments within state and territorial health departments that have applied for and been granted affiliation status with ASTHO. The peer networks (eg, human resource directors, IT directors) are similar but are supported in-house by ASTHO and do not have independent nonprofit status. In addition, we added groups active in governmental public health workforce issues but not affiliated with ASTHO. Thirty-one organizations/groups agreed to participate. Participation was entirely voluntary.

TABLE 1 •. Organizations Invited to Participate.

Interview methods

Key informant interviews were conducted by 1 of 2 authors (NJK or ML) between January and April 2013. Interviewees were queried about current and future challenges to public health and the opportunities for change that these challenges might stimulate.

Participants were asked 2 questions about specific areas of knowledge, skills, and attitudes (KSAs). One question was open-ended with the prompt: In your experience, what knowledge, skills, and attitudes does the public health workforce need the most and lack to meet the greatest challenges? We defined knowledge as possessing information and understanding how to use it, skills as ability to do things well, and attitudes as feelings about people or things (Supplemental Digital Content, Appendix Table 1, available at http://links.lww.com/JPHMP/A81).

The other question was a closed-ended question that used a 3-point Likert scale to rate each of 26 KSAs on the basis of crosscutting performance competencies for governmental program management and leadership. Participants were given the option to add additional KSAs and rate them on the same 3-point scale. The prompt for this question was as follows: I am going to read a list of KSAs that may help the overall public health workforce address the challenges of the future. For each, I'd like you to tell me whether you see these as low, medium, or high priority in strengthening the public health workforce. We defined low as being a lower tier priority or something the workforce already does well, medium as important to address, and high as the highest priority and not currently done well by the workforce.

Other questions explored respondent perceptions as to who is currently leading workforce development efforts for governmental public health, what stakeholders should be engaged, and what type of organizational structure would be needed to guide this work in the future. The range of length of interviews was approximately 45 to 90 minutes (averaging 60 minutes). Interview responses were directly entered into an electronic notes file for each interview.

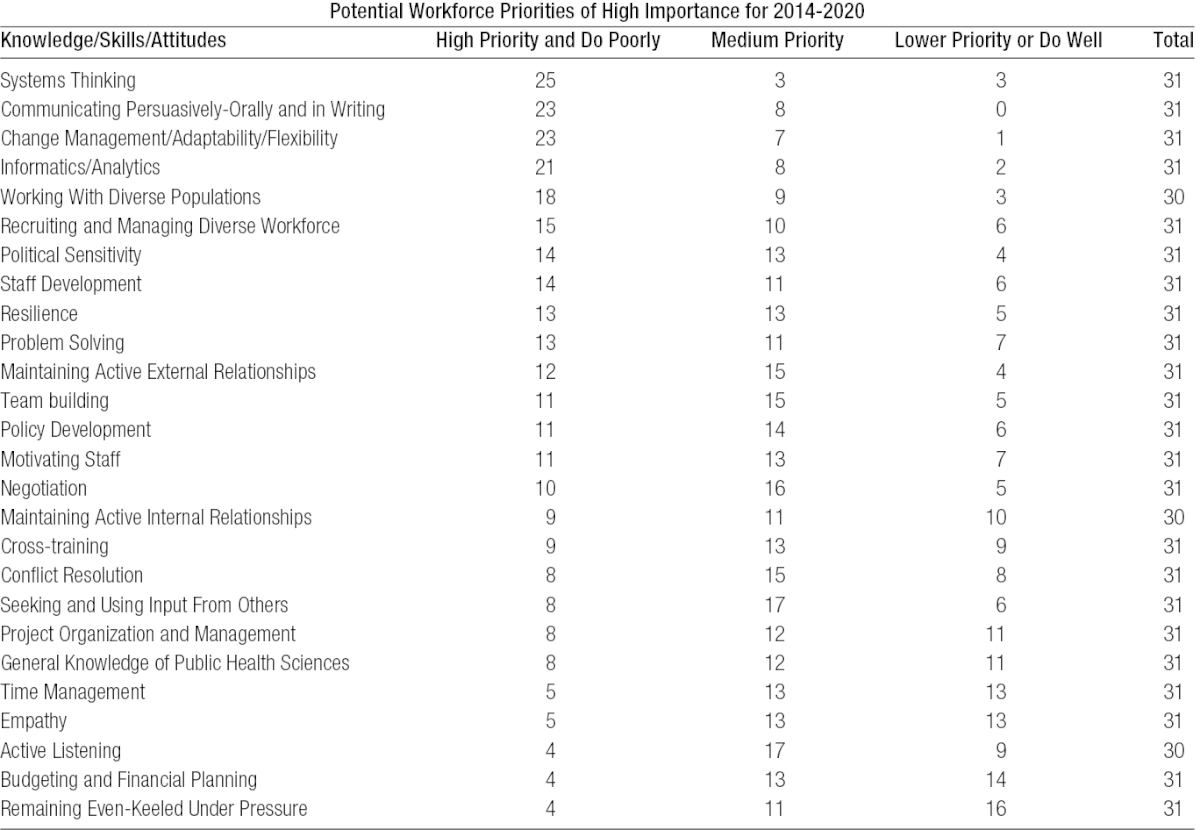

Following the interviews, the responses were reviewed and checked for accuracy, consistent with common ethnographic interviewing field note procedures.31 Open-ended question responses were then coded and categorized by the lead author and confirmed by another author (IRK). Following coding, response counts for each question were determined. The Likert-scale ranking of 26 KSAs was analyzed descriptively by calculating frequencies and percentages of high-medium-low rankings for each KSA separately among the total respondents ranking each attribute (Table 2).

TABLE 2 •. Knowledge, Skills, and Attitude Priority Likert-Scale Rankings.

Creation of content briefs

A list of 10 priority areas in workforce development emerged from these interview data. Representatives from the 31 organizations/groups who would be participating in the in-person meeting were divided into ten 3- to 4-person subgroups. Information from the key informant interviews was used to select a subgroup leader and members who were reasonably knowledgeable of their assigned topic. When necessary, other members were assigned randomly. A 2- to 3-page content brief was created by each subgroup for its assigned priority area. The briefs included background information on the workforce challenge, opportunities to address the challenge, current efforts underway, activities and tools that could improve the priority area, findings from the literature, and likely partners.

Deliberative selection of public health workforce priority areas

The briefs informed a deliberative priority setting 1.5-day convening that took place in April 2013 in Arlington, Virginia. Forty-three people attended, representing the ASTHO affiliate organizations and peer networks, invited national and federal partners, and staff from ASTHO and the de Beaumont Foundation. The content briefs were sent to each attendee before the meeting. Each subgroup appointed a member to present its brief to the wider group and engage the group in a discussion about its priority. After discussion of all top 10 priorities during the meeting, an anonymous prioritization exercise (1 vote allocated per respondent organization) culled the number of topics from 10 to 6 priorities. Next, small groups worked to improve the activities and potential partners sections of the briefs for the 6 priorities remaining; participants then voted a second time to develop a preliminary ordering of these 6 priorities. The full group engaged in a critique of each topic and later conducted a third vote to finalize the prioritized list.

Results

Prioritization of crosscutting workforce development needs

Approximately half of the participants reported more than 10 years of workforce development experience in public health, with 40% saying that they had more than 20 years' experience in the area. Overall, key informant interview data suggested a convergence on KSA priorities. Analysis of responses to the Likert scale question resulted in 10 KSAs rated as most important to address (medium or high tiers), as shown in Table 2. Systems thinking was ranked as most important by 25 of 31 respondents closely followed by communicating persuasively orally and in writing (n = 23/31). Change management, adaptability, and flexibility were combined into 1 measure because participants did not differentiate among the 3 and saw them as the same concept (n = 23/31). Informatics and data analysis for evidence-based decision making also garnered significant support (n = 21/31), as did working with diverse populations (n = 18/30).

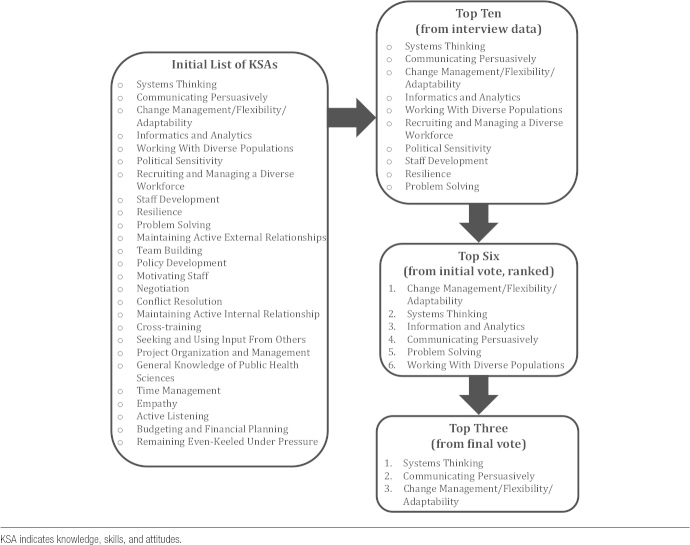

Content briefs on the top 10 priorities were presented, followed by a 3-stage voting exercise (Figure 1). This resulted in 3 top priorities in rank order:

Systems thinking

Communicating persuasively orally and in writing

Change management/flexibility/adaptability

FIGURE 1 •.

Three-Stage Voting Process to Prioritize Identified Workforce Needs

Key findings from key informant interviews

From the key informant interview data, 3 themes emerged as common goals for workforce development and principles underling future training efforts:

preparing for the future of public health for the next decade,

attracting and keeping talent by maintaining a quality workforce that finds satisfaction in their current jobs while understanding opportunities for professional growth; and

ensuring that public health has the right number of people in the right jobs, with the necessary skills and attitudes to keep Americans healthy.

Half of the participating organizations indicated that they had a staff member or contractor assigned to workforce development, with one-quarter engaging a volunteer member or committee. Most organizations (n = 23) reported doing no routine capacity assessments, while one-fifth of respondents indicated that they rely on information from ASTHO and National Association of County & City Health Officials profiles every 2 to 3 years to inform their organization's workforce development efforts.

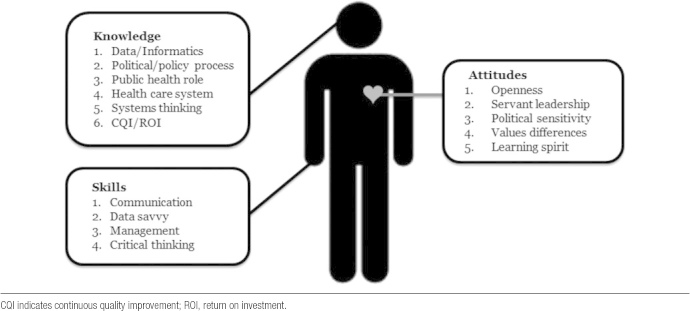

KSAs for the “ideal” public health worker

Fifteen independent attributes emerged from answers to the open-ended question about the most needed KSAs. These are detailed in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2 •.

Attributes Needed Among Public Health Workers

Barriers to KSA improvement

We asked about the factors with the greatest influence in the improvement of the KSAs. Leadership engagement (encouragement and time for career development), learning by doing (in-place learn and apply cycles with coaching and mentoring), a supportive work environment (stability, caring supervisors, trust, credibility, and adjustment for different learning styles), in-person training with follow-up on demand technical assistance, networking with peers internally and externally, and public recognition (feeling valued and appreciated for work) were most commonly cited. More broadly, we also asked respondents about what systematic challenges they saw in this space. The 5 greatest challenges to advancing a workforce development agenda were

- funder inflexibility (n = 17/31);

- including feelings of frustration, wastes of time and funding, and training siloed by profession or program area;

time constraints caused by increased workloads and burnout (14/31);

Dwindling support from leaders as they see positions and programs cut (9/31);

Travel restrictions and cuts in training dollars (9/31); and

Need for improved content, structural and delivery mechanisms for distance-based learning (5/31).

Training delivery methods

Although workforce development activities come in many forms, those that appealed most to the respondents were in-person immersion training/continuing education, distance learning on demand, creating peer networks, webinars, and mentoring. In the current economic environment, some of these were perceived by respondents as less feasible, and respondents recommended using the Internet for self-paced distance learning modules and online learning collaborative networks. Bringing trainers into a state or agency was also recommended, as were “train-the-trainers” programs. For creating affordable lasting changes, the respondents suggested rethinking combinations of strategies, such as in-person training with follow-up application of learning at the worksite, a learning collaborative of peers within and outside the home agency, and self-paced learning and technical assistance available just-in-time to be used on the job.

Coordination of workforce efforts

Confusion exists among respondents as to who is leading workforce development for public health. Half of the respondents could not identify a lead entity. The participants favored creating a collaborative for bringing key workforce partners together and holding them accountable for improving workforce development efficiently. This would require a coordinated, consortium approach. It would be a vehicle to communicate the needs of the front line of public health worker to national partners and funders.

Interviewees expressed a strong preference for a consortium model to bring key stakeholders to the table (n = 24/31) and called for creation of a convener organization staffed by professionals dedicated to workforce development. In the course of this line of questioning, respondents consistently recommended “bottom-up planning,” starting with a small number of workforce priorities to work on together initially as a consortium, with the eventual goal of 1 “go-to” Web site for information and links to resources, and perhaps later consideration for creating a separate 501(c)3.

Discussion

Public health is silo-driven without a unified, consistent identity. Instead of a unified position, competition among public health specialty areas such as chronic disease or emergency preparedness (ie, the “silos” mentioned previously) for legislative and public attention and categorical funding has nurtured silos rather than addressed the crosscutting needs common to all public health workers. Efforts to produce core competencies for public health generally and within specific disciplines further complicate workforce development efforts by creating expansive lists of needed skills from which it is difficult to discern priorities. This project provides a prioritization of skills needed among all public health workers as identified by leaders from 31 national organizations/groups. These priorities should be considered when developing workforce standards, creating or refining competencies, and prioritizing workforce training needs.

This project prioritized a set of KSAs, which is one approach to understanding workforce development needs. The development of core competencies is another. The Council on Linkages between Academia and Public Health Practice defined the core competencies for public health professionals (core competencies).16 With more than half of all state and local health departments using the core competencies to define workforce training needs,14,15 it is important to understand how the priorities identified in this study align with the core competencies and how they could suggest revisions.

Systems thinking, communicating persuasively, informatics and data analysis, and working with diverse populations align well with the core competencies. However, the core competencies' leadership and systems thinking domain includes only 12 of the 25 tier-specific competencies that apply to systems thinking. This study should be relevant to a future revision of the core competencies by separating systems thinking into a specific domain with increased detail.

Change management was the second crosscutting public health priority need identified in this project, not surprising given a decade of challenge and change in public health systems. However, change management is not a specific domain within the core competencies. It is addressed in one competency for all levels of public health professionals with an additional competency for senior managers (external systems change) and executive level staff (organizational change). However, the workforce is constantly assessing and reacting to change. It must be ready to adapt to current and future needs. Therefore, future revisions of the core competencies may consider including change management as a new domain or increase the number of competencies that focus on change management across the existing domains.

Overall, the prioritized KSAs mirror recent studies that have been conducted within states or specific silos and disciplines.32–35 One exception was financial management; financial management was not identified as a high priority for workforce development in this project. While this area has been identified as a need in previous studies and assessments,32 respondents in this study believed that the workforce's financial management skills were ‘better off’ than their skills in other prioritized areas.

While the focus of this study was the existing public health workforce, these results may help inform the revisions public health academic programs and standards are experiencing nationally. Efforts to refine public health education would benefit from introducing the concepts of systems thinking, change management, and communicating persuasively while in formal academic training so that new graduates have a foundation upon which to build once in practice. Attention to these concepts by the public health academic community may lead to better definition of the KSA areas and instructional methods for these key concepts.

Limitations

Representatives from 7 of the 38 national member organizations invited did not participate—4 did not respond to e-mail invitations and 3 did not succeed in finding a representative to participate.

Their experiences with workforce development may differ from those who participated. Nonrespondents tended to be either from organizations (1) representing smaller sectors of the public health workforce with fewer staffing resources or (2) with new staff or a vacancy limiting their ability to participate fully. Other limitations relate to the self-reported nature of this study and include participants' judgments on the basis of their own and their organizations' experiences, which may or may not be representative of all practitioners represented by said organization; a logistical need to limit the number and selection of KSAs to allow respondents to differentially rank them in the final exercise; and the concept that KSAs may be differently experienced or important for different roles within a discipline (eg, line vs management staff). Four participants did not feel knowledgeable enough to rate all KSAs in the initial interviews and were allowed to skip those (each participant elected to skip 1 KSA, as noted in Table 2). As this effort focuses on governmental public health and not private entities working in the space of public health, transferability of results may be limited.

We addressed these limitations by asking about KSAs in both an open-ended and rating format, allowing for participants to add to the KSAs initially identified by the research team. In addition, input was gathered via 3 methods—interviews, participation in small group development of content briefs for the top priorities, and presentation and thorough discussion of these options in person at the retreat before final voting on priorities occurred.

Conclusion

Decades of categorical funding created a highly specialized and knowledgeable public health workforce that unfortunately lacks many of the foundational skills now most in demand. Change is needed to at least create a balance between core and specialty training. To accomplish this federal and nongovernment funders will need to realign priorities and pool funds across categorical silos with the purpose of supporting crosscutting workforce development that improves knowledge, skills, and attitudes for keeping our country healthy. Identifying the KSAs that public health requires to fulfill its crucial responsibilities is one step in that direction.

Footnotes

This work was funded through a grant from the de Beaumont Foundation.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citation appears in the printed text and is provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's Web site (http://www.JPHMP.com).

REFERENCES

- 1.Association of State and Territorial Health Officials. Budget Cuts Continue to Affect the Health of Americans. May 2011 update. Arlington, VA: Association of State and Territorial Health Officials; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Association of State and Territorial Health Officials. ASTHO Profile of Health. Vol 3. Atlanta, GA: Association of State and Territorial Health Officials; 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tulchinsky TH, Varavikova EA. New Public Health. Waltham, MA: Academic Press Incorporated; 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lichtveld MY, Cioffi JP, Baker EL, Jr, et al. Partnership for front-line success: a call for a national action agenda on workforce development. J Public Health Manage Pract. 2001;7(4):1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lichtveld MY, Cioffi JP. Public health workforce development: progress, challenges, and opportunities. J Public Health Manage Pract. 2003;9(6):443–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gebbie K, Merrill J, Tilson HH. The public health workforce. Health Aff. 2002;21(6):57–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tilson H, Gebbie KM. The public health workforce. Annu Rev Public Health. 2004;25:341–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allegrante JP, Moon RW, Auld ME, Gebbie KM. Continuing-education needs of the currently employed public health education workforce. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(8):1230–1234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calhoun JG, Ramiah K, Weist EM, Shortell SM. Development of a core competency model for the master of public health degree. J Inform. 2008;98(9):1598–1607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gebbie K, Merrill J. Public health worker competencies for emergency response. J Public Health Manage Pract. 2002;8(3):73–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gebbie KM, Qureshi K. Emergency and disaster preparedness: core competencies for nurses: what every nurse should but may not know. AJN Am J Nurs. 2002;102(1):46–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barry MM, Allegrante JP, Lamarre M, Auld ME, Taub A. The Galway Consensus Conference: International collaboration on the development of core competencies for health promotion and health education. Glob Health Promot. 2009;16(2):5–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Markenson D, DiMaggio C, Redlener I. Preparing health professions students for terrorism, disaster, and public health emergencies: core competencies. Acad Med. 2005;80(6):517–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Association of State and Territorial Health Officials. ASTHO Profile of Health. Vol. 2. Arlington, VA: Association of State and Territorial Health Officials; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Association of County & City Health Officials. National Profile of Local Health Departments. Washington, DC: National Association of County & City Health Officials; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 16.The Council on Linkages Between Academia and Public Health Practice. Core Competencies for Public Health Professionals. Washington, DC: The Council on Linkages Between Academia and Public Health Practice; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gebbie KM, Turnock BJ. The public health workforce, 2006: new challenges. Health Aff. 2006;25(4):923–933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gebbie K, Rosenstock L, Hernandez LM. Who Will Keep the Public Healthy?: Educating Public Health Professionals for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Institute of Medicine (US); Committee on Assuring the Health of the Public in the 21st Century. The Future of the Public's Health in the 21st Century. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gebbie KM. The Public Health Work Force: Enumeration 2000. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Bureau of Health Professions, National Center for Health Workforce Information and Analysis; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cioffi JP, Lichtveld MY, Tilson H. A research agenda for public health workforce development. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2004;10:186–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bureau of Health Professions. Public Health Workforce Study. Rockville, MD: Bureau of Health Professions; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perlino CM. The public health workforce shortage: left unchecked, will we be protected?. Am Public Health Assoc Issue Brief. 2006:1–12 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baker EL, Stevens RH. Linking agency accreditation to workforce credentialing: a few steps along a difficult path. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2007;13:430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ogolla C, Cioffi JP. Concerns in workforce development: linking certification and credentialing to outcomes. Public Health Nurs. 2007;24:429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.ASTHO. About ASTHO's affiliates. http://www.astho.org/About/Affiliates/ Accessed August 30, 2013.

- 27.Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists. Epidemiology Enumeration Assessment. Atlanta, GA: Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boulton M, Beck A. National Laboratory Capacity Assessment, 2011: Findings and Recommendations for Strengthening the U.S. Workforce in Public Health, Environmental and Agricultural Laboratories. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boulton M, Beck A. Enumeration and Characterization of the Public Health Nurse Workforce. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan; 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lenaway D, Halverson P, Sotnikov S, Tilson H, Corso L, Millington W. Public health systems research: setting a national agenda. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(3):410–413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Creswell JW. Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Place J, Edgar M, Sever M. Assessing the needs for public health workforce development. 2012

- 33.Wisconsin Center for Public Health Education and Training. Wisconsin Local Public Health Department and Tribal Health Center Workforce Training Needs Assessment 2012-2013 Results. Madison, WI: Wisconsin Center for Public Health Education and Training; 2012-2013. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Northwest Regional Training Center. Training needs assessment regional brief. http://www.nwcphp.org/documents/communications/news/training-needs-assessment-regional-brief-2013 Accessed February 19, 2014.

- 35.Neuberger JS, Montes JH, Woodhouse CL, Nazir N, Ferebee A. Continuing educational needs of APHA members within the Professional Public Health Workforce [published online ahead of print October 4, 2013]. J Public Health Manage Pract. 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3182a9c0f5. [DOI] [PubMed]