Abstract

Peer pressure and general conformity to adult norms have been found to be strongly associated with alcohol use among adolescents; however there is limited knowledge about the sociocultural factors that might influence this relationship. Theory and research suggest that masculine norms might directly and indirectly contribute to alcohol use through peer pressure and general conformity to adult norms. Whereas being male is typically identified as a risk factor for alcohol use, masculine norms provide greater specificity than sex alone in explaining why some boys drinkmore than others. There is growing evidence that girls who endorse masculine norms may be at heightened risk of engaging in risky behaviors including alcohol use. Data were provided by adolescents living in a rural area in the Northeastern United States and were collected in 2006. This study demonstrated that masculine norms were associated with peer pressure and general conformity and alcohol use for both adolescent girls (n = 124) and boys (n = 138), though the relationship between masculine norms and alcohol use was stronger for boys. The study’s limitations are noted and theoretical and practical implications are discussed.

Keywords: masculine norms, alcohol, adolescents, peer pressure, general conformity, risk factor

INTRODUCTION

Underage drinking is a significant public health problem given the profound and negative impact it has on society (Collins, Ellickson, McCaffrey, & Hambarsoomians, 2007). Alcohol is the substance most commonly used by adolescents (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2009). Research suggests that the earlier the onset of alcohol use, the higher the likelihood adolescents will develop future alcohol use-related problems (Nelson & Wittchen, 1998) and engage in health compromising behaviors such as illicit substance use (Huurre, Lintonen, Kaprio, Pelkonen, Marttunen, & Avo, 2010) and risky sexual behavior (Bailey, Pollock, Martin, & Lynch, 1999). Therefore, it is essential to identify the etiological factors and mechanisms that increase adolescents’ risk of alcohol use.

Masculine Norms

Research indicates that adolescent boys generally engage in higher rates of alcohol use compared to girls (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2008; Song, Smiler, Champion, & Wolfson, 2012). However, despite the gender differences, theory and research suggest that masculine norms provide greater specificity than sex alone in explaining why certain individuals drink more than others (Huselid & Cooper, 1992; Iwamoto, Cheng, Lee, Takamatsu, & Gordon, 2011). Masculine norms reflect socially ascribed beliefs, expectations, and values of what it means to be a man (Mahalik et al., 2003). Masculine norms are formed at an early age and appear to shape and guide how one interacts and behaves with others (Courtenay, 2000). One promising approach operationalizing masculine norms is the Conformity to Masculine Norms Index (CMNI; Mahalik et al., 2003; Parent & Moradi, 2009; Smiler, 2006). This measure operationalizes masculinity in a multidimensional manner and provides distinct assessment of a variety of masculine norms, including the drive for multiple sexual partners (i.e., playboy), controlling and restricting expression of emotions (i.e., emotional control), the drive to win at all cost (i.e., winning), striving to appear heterosexual (i.e., heterosexual display), and engaging in risky behavior (i.e., risk-taking).

Theoretical models suggest that engaging in heavy drinking and the ability to consume large amounts of alcohol are an expression of masculinity (Courtenay, 2000; Young, Morales, McCabe, Boyd, & D’Arcy, 2005). Several studies among college students have found a strong relationship between the masculine norm of emotional control and binge drinking (Liu & Iwamoto, 2007); separately, playboy, risk-taking, and winning norms were associated with drinking to intoxication and alcohol use-related problems among ethnically diverse samples of college students, while controlling for well-established determinants of problem drinking (Iwamoto et al., 2011). However, it is unclear whether the masculine norms and alcohol use relationship operates similarly among adolescents.

Peer Pressure and General Conformity to Adult Norms

Peer influence, including peer pressure and conforming to adult norms, has been found to be strongly associated with alcohol use among adolescents (Nash, McQueen, & Bray, 2004). Late adolescence represents a time in which parental monitoring decreases as peers become the individual’s primary socialization influence. Becoming a member of a peer group is an important developmental task for adolescents because they facilitate exploration of individual interests while building a sense of belongingness to others (Erikson, 1968; Santor, Messervey, & Kusumakar, 2000). However, being a member of a peer group comes with a “cost” given that being in a group requires the individual to conform to the values and behaviors of the peer group which may not be consistent with her/his own values. During this developmental period, there is an unusually strong social pressure to conform to peer norms (Arnett, 2000), known as “peer pressure” (Santor et al., 2000). Consistent with peer cluster theory (Oetting, & Beauvais, 1987), research has found that peer pressure among adolescents is a robust predictor of alcohol use (Santor et al., 2000; Trucco, Colder, Bowker, & Wieczorek, 2011).

Parents and other adults also provide some pressure to behave in a specific manner, known as “general conformity.” Theory suggests that individuals who endorse general conformity are more rule-abiding and are less likely to use alcohol or other drugs, given that these behaviors are perceived as deviant. Results suggest that adolescents who have higher general conformity beliefs are less likely to engage in alcohol use (Nash et al., 2004; Santor et al., 2000). Little work has delineated how either general conformity or peer pressure may mediate the relations between masculine norms and alcohol use.

Theoretical Framework

Hatzenbuehler’s (2009) Psychological Mediation Framework (PMF) offers a framework to understand the relationship between masculine norms, peer and adult influence, and alcohol use among adolescents. The PMF describes the interaction of internal factors, including masculine norms with the environment; it explains how gender socialization factors, including masculine norms, may influence one’s susceptibility to peer pressure and why individuals select into specific peer groups (see Figure 1). Moreover, drawing on Positive Reinforcement Theory (Cooper, Frone, Russell, & Mudar, 1995), individuals who adhere to masculine norms, such as winning or playboy, might seek out certain types of peers and be more influenced by peer groups where they fail to consider the negative effects of alcohol (Meir, Slutske, Arndt, & Cadoret, 2007).

FIGURE 1.

Psychological mediational framework (Hatezenbuehler, 2009.)

In addition to exploring how masculine norms and peer pressure is related to alcohol use among boys, we also explore these relationships for girls. Although psychological researchers have accepted the idea that boys and girls can demonstrate both masculinity and femininity since the 1970s (Bem, 1974; Smiler, 2004; Spence & Helmreich, 1978, 1980; Twenge, 1997), several reviewers have commented on the recent tendency to examine masculinity with all male samples (Smiler & Epstein, 2010; Whorley & Addis, 2006; Wong, Steinfeldt, Speight, & Hickman, 2010). Although there is ample evidence that males have higher mean scores than females on masculinity measures, there are few studies that assess whether relations between masculinity measures and other variables are consistent across sex. In one of the few studies to examine this, Smiler (2006) reported similar, but not identical, patterns of correlations between the CMNI Power over Women scale and two measures of sexism among males and females aged 18–83 as well as evidence that undergraduate men’s scores on other CMNI scales were related to sexism but undergraduate women’s scores did not show this pattern. In a similar vein, the CMNI-46 (Parent & Moradi, 2009) has been shown to demonstrate configural invariance but dissimilar scalar invariance for men and women, suggesting a similar factor structure but different levels of norm endorsement (Parent & Smiler, in press).

Like adolescent boys, adolescent girls who adhere to masculine norms may be at heightened risk of engaging in risky behaviors, including alcohol use; some females might adhere to certain masculine norms (i.e., risk taking, winning) in order to “fit in” with their peer group (Lyons & Willott, 2008). Young and colleagues’ (2005) qualitative study among college women suggested that many heavy drinking women did so in order to gain acceptance of their male peers by “drinking like a guy.” However, it is unclear if girls’ drinking behavior is driven by conformity to masculine norms, peer pressure, or both.

The Current Study

Accordingly, the purpose of this study was to advance the literature by examining howpeer influence, including peer pressure and conformity to adult norms, mediated the relationship between masculine norms and alcohol use among adolescent boys and girls. Our study is novel in that no studies to date have: (1) investigated the relationship between a multidimensional measure of masculine norms and alcohol use among an adolescent sample; (2) investigated the relationship between masculine norms and peer influence factors; (3) examined the relationship between masculine norms and alcohol use among women in particular; and (4) compared models for boys and girls.

METHOD

Participants

Data were provided by 124 female and 138 male high school seniors (mean age: 17.03; range: 16–19) who attended a rural public high school in a Northeastern U.S. state. The vast majority of participants were of European-American descent (74.1%), with others reporting Native-American (7.5%) or Latino (5.3%) descent; a substantial number did not report their ethnic background (11.8%). No other ethnic group was reported by more than 2.6% of the sample.

Measures

Conformity to Masculine Norms Inventory

Participants completed five subscales from the Conformity to Masculine Norms Inventory (CMNI) (Mahalik et al., 2003). Logistic concerns prevented deployment of the complete CMNI and shortened versions had not been published prior to data collection, so scales were chosen based on theoretical interest and examination of the intercorrelations among subscales (Mahalik et al., 2003). Scales assessed emotional control, winning, playboy, risktaking, and heterosexual display (originally disdain for homosexuals; see Parent & Moradi, 2009). A sample item is, “In general, I will do anything to win” (winning scale) and participants responded to all items on a four point scale anchored by “strongly disagree” (1) and “strongly agree” (4). Scales ranged in length from six to eleven items. Mean scores indicate greater conformity to that norm. Scale internal consistency estimates ranged from α = 0.81 to 0.88.

Peer Pressure and Conformity

Participants completed a measure of peer pressure developed by Santor, Messervey, and Kusumakar (2000). The scale includes two subscales: peer pressure, and general (adult) conformity. Scales vary in length from 7 to 12 items and a sample items include, “At times, I’ve broken rules because others have urged me to” (peer pressure scale) and “I usually obey my parents” (general conformity scale). Responses are provided on a five point scale anchored by “strongly disagree” (1) and “strongly agree” (5). The internal consistency estimate for the peer pressure and general conformity measures were α = 0.83 and 0.78, respectively.

Alcohol Use

Participants also reported the frequency with which they consume “beer, wine coolers, or hard cider.” Response options included never (1), a few times per year, a few times per month, once or twice a week, and three or more times per week (5).

Procedure

All surveys were administered during 12th grade English classes by one of the researchers or a member of the research team on a single day. Upon arriving in class, the teacher informed students they would have the opportunity to complete the study or work quietly at their desk (e.g., on homework). A member of the research team then asked students to participate in a study of “adolescents’ choices and beliefs” and informed them that every student who completed the study would be eligible to win one of four $25 gift certificates to the local mall. Students were also informed of their rights as research participants, then provided with consent forms and survey packets. Students who chose not to complete the study remained at their desks, and either completed other work or sat with their heads down.

Surveys were administered during the spring semester of participants’ senior year in high school and school records indicate >95% attendance for the senior class on that day. All participants provided consent/assent at the time of the survey. Less than ten adolescents refused to participate and were allowed to do other work quietly at their desks. Parents and guardians were notified of the survey approximately two weeks prior and were given information on how to prevent their child from participating; none did. However, three participants or their parents contacted the researcher within one week of the survey and revoked participation; these surveys were removed from the dataset.

Data Analytic Plan

The distributions of the variables were inspected prior to conducting the analyses, and their distributions including alcohol use were normal. Data analysis used structural equation modeling (SEM) to determine the relationships between masculine norms, peer pressure, general conformity, and alcohol use. SEM has multiple advantages over other approaches since it can test and model complex patterns of relationships, multiple mediators and can simultaneously test multiple outcome variables. To assess the fit of the structural models, the comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis fit index (TLI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) were utilized. The CFI and TLI values greater than 0.95 and RMSEA values less than 0.05 indicate near model-to-data fit (Quintana & Maxwell, 1999). Full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation was used to estimate the missing parameters in the model. FIML procedures do not input data but rather through expectation maximization (EM) procedure, estimates the standards and parameters in the model (Enders, 2001).

RESULTS

Preliminary Analyses

Means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations for all study variables are provided in Table 1. Descriptive results indicated that 79% of the sample had consumed alcohol in the past year, 31% of participants consumed alcohol a few times during the past year, 26% reported drinking alcohol a few times a month, and 22% indicated that they consumed one or more alcoholic beverage in a week. Boys and girls differed on all study variables. Boys reported significantly more alcohol use over the past year, F(1, 250),= 8.56, p = .004., higher peer pressure, F(1, 250), = 20.14, p = .001., greater endorsement of all masculine norms, and lower general conformity (Table 1). In order to examine where the models operated differently (invariance) for boy and girls, we conducted, multigroup SEM. The structural weights were constrained to be equal across groups, and the results suggested that the constrained model was a worse fit than unconstrained model, χ2 (21) = 39.74, p <.001. Given the differences between girls and boys, we conducted separate SEM analyses for each group.

TABLE 1.

Means, standard deviations, correlations for alcohol use, peer influence, and masculine norms subscales among adolescent boys and girls

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Alcohol use | — | .44** | −.30** | .31** | .10 | .19* | .40** | .29** |

| 2. Peer pressure | .38** | — | −.33** | .29** | −.15 | .15 | .23** | .13 |

| 3. General conformity | −.46** | −.27** | — | −.16 | −.03 | .06 | −.21* | −.22* |

| 4. Heterosexual | .12 | .09 | .00 | — | .15 | .36** | .22* | .05 |

| 5. Emotional control | .03 | .00 | .09 | .10 | — | .11 | .18* | .19* |

| 6. Winning | .05 | .19* | .00 | .23* | .00 | — | .18* | .21* |

| 7. Playboy | .11 | .16 | −.22** | −.07 | .20* | −.07 | — | .27** |

| 8. Risk taking | .35** | .15 | −.37** | −.10 | .03 | .27** | .16 | — |

| Means (boy/girls) | 2.71/2.31 | 2.63/2.26 | 3.49/3.7 | 2.88/2.56 | 2.61/2.32 | 2.71/2.3 | 2.12/1.64 | 2.86/2.58 |

| SD (boy/girls) | 1.09/1.07 | .69/.63 | .61/.61 | .50/.46 | .52/.52 | .60/.51 | .55/.41 | .48/.40 |

Note:

p < .05,

p < .01.

Correlations for boy are above the diagonal; girls are below the diagonal.

Structural Equation Modeling

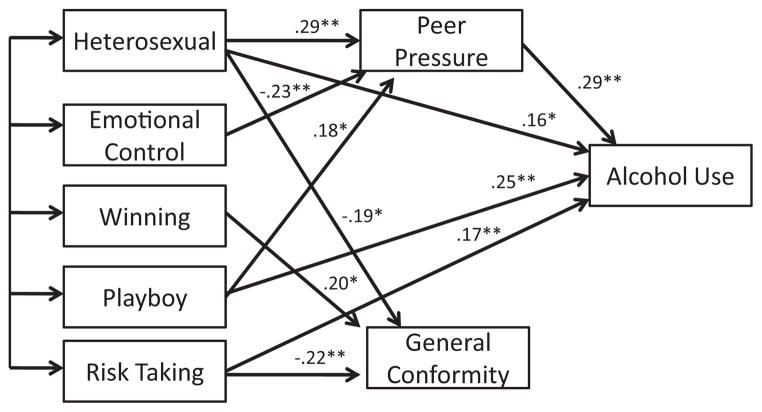

Boys

Fit indexes for the SEM boys model suggested that overall data fit the model well, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.00, RMSEA = 0.00 (Figure 2). Boys’ alcohol use was directly predicted by greater conformity to norms of heterosexual display, playboy, and risk taking. Greater susceptibility to peer pressure also predicted more alcohol use, and was implicated in indirect paths for the masculine norms of heterosexual display, (less) emotional control, and playboy. General conformity was unrelated to boys’ alcohol use, although it was related to less conformity to the norms of heterosexual display and risk taking, as well as greater conformity to the winning norm.

FIGURE 2.

Path analysis for boys.

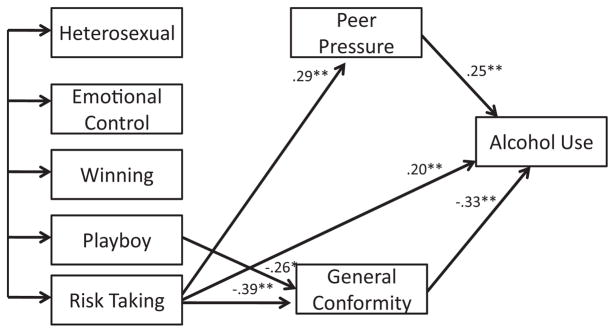

Girls

The fit indexes suggested that overall data fit the model well for the girls in our sample (Figure 3), CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.00, RMSEA = 0.01. Greater conformity to the risk-taking norm was related to greater alcohol use, echoing the boys’ results. Greater peer pressure was also related to greater alcohol use, including an indirect path for risk taking through peer pressure. Higher levels of general conformity were associated with lower levels of alcohol use for girls, including indirect paths for lower levels of both playboy and risk taking.

FIGURE 3.

Path analysis for girls.

DISCUSSION

Underage drinking among adolescents is a significant public health concern. The current findings advance the literature by identifying how masculine norms and peer norms jointly influence drinking behaviors of male and female adolescents. Specifically, masculine norms were found to be directly associated with alcohol use and also indirectly through peer norm mechanisms. Findings mostly differed for boys and girls, and indicated much closer connections between masculine norms and alcohol use, directly and indirectly, for boys. We believe, this is the first study that specifies the relations between masculine norms, peer norms and alcohol use among adolescents, and our findings suggest that masculine norms are important factors that should be considered in the development of alcohol reduction interventions and prevention efforts for both girls and boys, but especially boys.

Previous studies have identified a link between masculine norms and alcohol use among young adults, but only speculated about the potential mechanisms through which masculine norms may contribute to alcohol use. The current findings provide novel information about the ways masculine norms may contribute directly and indirectly to alcohol use through peer pressure and general conformity. Greater adherence to the masculine norms of heterosexual display, playboy, and risk taking, along with peer pressure, were all directly related to alcohol use among boys. These findings are generally consistent with the young adult alcohol literature (Iwamoto et al., 2011).

Masculine norms were also related to peer pressure and general conformity. Specifically, boys who reported greater conformity to the heterosexual display, winning, and playboy norms were also reported greater susceptibility to peer pressure, while boys who reported less emotional control were less likely to be influenced by peer pressure. These findings make theoretical sense given that many boys perceive a need to prove their masculinity (Levant, 1996). Displaying one’s heterosexuality (Messner, 1992; Tolman, Spencer, Harmon, Rosen-Reynoso, & Striepe, 2004) and being promiscuous (i.e., playboy; Crawford & Popp, 2003; Smiler, 2012) are norms that reflect how one is perceived by others, and suggest these individuals might be more externally-focused and thus more susceptible to peer pressure. At the same time, boys with greater risk taking and heterosexual display were less likely to conform in general, whereas boys with higher winning scores reported more general conformity. These findings echo Eckert’s (1989) analysis of the social groups favored and stigmatized by adults, including the tendency to overlook inappropriate behavior by some adolescents (i.e., “jocks”) while punishing others (i.e., “burnouts”) for the same behavior.

The findings for girls indicated that only the masculine norms of risk taking and playboy were important, and these appeared to have indirect effects through both peer pressure and general conformity. Similar to the boys, risk taking was related directly to alcohol use and indirectly through peer pressure; it was also related to lower levels of general conformity. However, general conformity was negatively associated with alcohol use for girls but not boys. This finding is conceptually consistent with the gender role literature: girls are generally expected to follow adults’ rules but boys are “expected” to misbehave (Bem, 1993; Mahalik et al., 2003; Levant 1996).

Implications

Our findings provide further evidence that masculine norms function differently for girls than for boys (Parent & Smiler, in press; Smiler, 2006). This indicates that although girls and women may adhere to these norms at similar levels to (some) boys and men, the implications of their adherence to masculine norms differ. At the theoretical level, it suggests the abstract construct known as masculinity may function differently for females than for males (for further discussion, see Spence & Helmreich, 1980). At the practical level, these findings suggest that gender-neutral interventions designed to minimize risk taking may be of limited use because the pattern of correlates and predictors differed notably for boys and girls.

Limitations

Despite the study’s strengths and contribution to the literature, there are several limitations that are worth noting. The current study design was cross-sectional, hence temporal relationships between the variables and meditational effects are not definitive. Additionally, these results may not generalize to other locations, particularly those with low rates of alcohol misuse. Our sample consisted of European-American adolescents living in a rural area in the Northeastern United States that had been supported by industry (i.e., manufacturing) and tourism through the early and mid-20th Century; findings from our study may not be applicable to other ethnic groups or other residential locations, including other types of rural areas. A more comprehensive measure of daily/monthly alcohol use and related problems might have better captured this behavior. Additionally, we have defined risk very narrowly, as elevated levels of alcohol consumption. Our analysis did not examine other or broader indicators of adolescent functioning and wellbeing, nor do we have information regarding adolescents’ history of drinking or lessons they have learned from adverse experiences.

Some critics have argued that masculine norms such as risk taking may overlap with personality factors such as disinhibition or sensation seeking (Moore & Stuart, 2005). However, Parent and colleagues (2011) revealed that masculine norms, as assessed by the CMNI-46, appear to be empirically distinct and independent constructs from Big Five personality dimensions (Costa & McCrae, 1992).

Overall, the study provided a greater understanding of the link between masculinity, peer influence, and alcohol use among rural adolescents. Our examination of masculine norms, and not simply gender differences, has great potential to extend the empirical research on adolescent risk behaviors by delineating the relevant mechanisms as well as identifying the boys at greatest risk. The examination of girls’ conformity to masculine norms also reflects the importance of specification beyond gender differences, especially given that female youth’s scores on measures of masculinity have risen over the last several decades (Twenge, 1997).

GLOSSARY

- General Conformity to Adult Norms

Pressure by parents and other adults to behave in a specific manner

- Peer Pressure

Social pressure by peers to conform to peer norms

- Masculine Norms

It reflects socially ascribed beliefs, expectations, and values of what it means to be a man

Biographies

Derek Iwamoto, PhD, is a Research Assistant Professor at the University of Maryland, College Park, MD, in the Center for Addictions, Personality and Emotion Research. The aim of his research is to address health disparities experienced by traditionally underserved and understudied groups such as Asian Americans and African Americans by (1) identifying sociocultural factors (masculine and feminine norms) and mechanisms that influence the development of substance abuse and related problems, and (2) conducting translational research to inform and augment substance abuse treatment and interventions targeting at-risk ethnic and racial minorities.

Derek Iwamoto, PhD, is a Research Assistant Professor at the University of Maryland, College Park, MD, in the Center for Addictions, Personality and Emotion Research. The aim of his research is to address health disparities experienced by traditionally underserved and understudied groups such as Asian Americans and African Americans by (1) identifying sociocultural factors (masculine and feminine norms) and mechanisms that influence the development of substance abuse and related problems, and (2) conducting translational research to inform and augment substance abuse treatment and interventions targeting at-risk ethnic and racial minorities.

Andrew Smiler, PhD, is the author of “Challenging Casanova: Beyond the stereotype of promiscuous young male sexuality” (Jossey-Bass, Fall, 2012). He is a visiting Assistant Professor of Psychology at Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, NC. His sexuality research focuses on normative aspects of sexual development, such as age and perception of first kiss, first “serious” relationship, and first intercourse among 15–25-year olds. He also studies variations in the definitions of masculinity, including “jocks,” “rebels,” and “nerds.” Follow him @AndrewSmiler

Andrew Smiler, PhD, is the author of “Challenging Casanova: Beyond the stereotype of promiscuous young male sexuality” (Jossey-Bass, Fall, 2012). He is a visiting Assistant Professor of Psychology at Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, NC. His sexuality research focuses on normative aspects of sexual development, such as age and perception of first kiss, first “serious” relationship, and first intercourse among 15–25-year olds. He also studies variations in the definitions of masculinity, including “jocks,” “rebels,” and “nerds.” Follow him @AndrewSmiler

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

References

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist. 2000;55(5):469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey SL, Pollock NK, Martin CS, Lynch KG. Risky sexual behaviors among adolescents with alcohol use disorders. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1999;25:179–181. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bem SL. The measurement of psychological androgyny. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1974;42:155–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bem SL. The lenses of gender. New Haven, CT: Yale University press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Ellickson PL, McCaffrey D, Hambarsoomians K. Early adolescents exposure to alcohol advertising and its relationship to underage drinking. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2007;40:527–534. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Frone MR, Russell M, Mudar P. Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:990–1005. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.69.5.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, McCrae RR. Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Courtenay WH. Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men’s well-being: A theory of gender and health. Social Science & Medicine. 2000;50:1385–1401. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00390-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford M, Popp D. Sexual double standards: A review and methodological critique of two decades of research. Journal of Sex Research. 2003;40:13–26. doi: 10.1080/00224490309552163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckert P. Jocks and burnouts: Social categories and identity in the high school. New York: Teachers College Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK. A primer on maximum likelihood algorithms available for use with missing data. Structural Equation Modeling. 2001;8:128–141. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH. Identity: Youth and crisis. New York: W. W. Norton; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler M. How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological mediation framework. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135:707–730. doi: 10.1037/a0016441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huselid RF, Cooper ML. Gender roles as mediators of sex differences in adolescent alcohol use and abuse. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1992;33:348–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huurre T, Lintonen T, Kaprio J, Pelkonen M, Marttunen M, Avo H. Adolescent risk factors for excessive alcohol use at age 32 years. A 16-year prospective follow-up study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2010;45:125–134. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0048-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto DK, Cheng A, Lee C, Takamatsu S, Gordon D. Maning Up: Masculine norms, drinking to intoxication and alcohol use-related problems. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36:906–911. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings (NIH Publication No. 09-7401) Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Levant R. The new psychology of men. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 1996;27:259–265. [Google Scholar]

- Liu WM, Iwamoto DK. Conformity to masculine norms, Asian values, coping strategies, peer group influences and substance use among Asian American men. Psychology of Men and Masculinity. 2007;8:25–39. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons AC, Willott SA. Alcohol consumption, gender identities and women’s changing social positions. Sex Roles. 2008;59:694–712. [Google Scholar]

- Mahalik JR, Locke BD, Ludlow LH, Diemer MA, Scott RPJ, Gottfried M, et al. Development of the Conformity to Masculine Norms Inventory. Journal of Men and Masculinity. 2003;4:3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Meir MH, Slutske WS, Arndt S, Cadoret RJ. Positive alcohol expectancies partially mediate the relation between delinquent behavior and alcohol use: Generalizability across age, sex, and race in a cohort of 85,000 Iowa schoolchildren. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21:25–34. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messner MA. Power at play: Sports and the problem of masculinity. Boston: Beacon Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Moore TM, Stuart GL. A review of the literature on masculinity and partner violence. Psychology of Men and Masculinity. 2005;6(1):46–61. [Google Scholar]

- Nash SG, McQueen A, Bray JH. Pathways to adolescent alcohol use: Family environment, peer influence, and parental expectations. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2004;37:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson CB, Wittchen H-U. DSM-IV alcohol disorders in a general population sample of adolescents and young adults. Addiction. 1998;93:1065–1077. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.937106511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oetting ER, Beauvais F. Peer cluster theory, socialization characteristics, and adolescent drug use: A path analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1987;34:205–213. [Google Scholar]

- Parent MC, Moradi B. Confirmatory factor analysis of the Conformity to Masculine Norms Inventory and development of the CMNI-46. Psychology of Men and Masculinity. 2009;10:175–189. [Google Scholar]

- Parent MC, Moradi B, Rummell CM, Tokar DM. Evidence of construct distinctiviness for conformity to masculine norms. Psychology of Men and Masculinity. 2011;12:354–367. doi: 10.1037/a0023837. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parent MC, Smiler AP. Metric invariance in the Conformity to Masculine Norms Index-46 among women and men. Psychology of Men and Masculinity in press. [Google Scholar]

- Quintana SM, Maxwell SE. Implications of recent developments in structural equation modeling for counseling psychology. The Counseling Psychologist. 1999;27:485–527. [Google Scholar]

- Santor DA, Messervey D, Kusumakar V. Measuring peer pressure, popularity, and conformity in adolescent boys and girls: Predicting school performance, sexual attitudes and substance abuse. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2000;29:163–182. [Google Scholar]

- Smiler AP. Thirty years after gender: Concepts and measures of masculinity. Sex Roles. 2004;50:15–26. [Google Scholar]

- Smiler AP. Conforming to masculine norms: Evidence for validity among adult men and women. Sex Roles. 2006;54:767–775. [Google Scholar]

- Smiler AP, Epstein M. Measuring gender: Options and issues. In: Chrisler JC, McCreary DR, editors. Handbook of Gender Research in Psychology. New York: Springer Science+Business Media, LCC; 2010. pp. 133–157. [Google Scholar]

- Song EY, Smiler AP, Champion H, Wolfson M. Everyone says it’s OK: Adolescents’ perceptions of peer, parent, and community norms, alcohol consequences, and alcohol-related consequences. Substance Use & Misuse. 2012;47:86–98. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2011.629704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spence JT, Helmreich RL. Masculinity and femininity: Their psychological dimensions, correlates and antecedents. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Spence JT, Helmreich RL. Masculine instrumentality and feminine expressiveness: Their relationships with sex role attitudes and behaviors. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1980;5:147–163. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Office of applied studies results from the 2007 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2008. (DHHS Publication No. SMA 08–4343, NSDUH Series H-34) [Google Scholar]

- Tolman DL, Spencer R, Harmon T, Rosen-Reynoso M, Striepe M. Getting close, staying cool: Early adolescent boys’ experiences with romantic relationships. In: Way N, Chu J, editors. Adolescent boys: Exploring diverse cultures of boyhood. New York: New York University press; 2004. pp. 235–255. [Google Scholar]

- Trucco EM, Colder CR, Bowker JC, Wieczorek W. Interpersonal goals and susceptibility to peer influence: Risk factors for intentions to initiate substance use during early adolescents. The Journal of Early Adolescents. 2011;31:526–547. doi: 10.1177/0272431610366252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twenge JM. Changes in masculine and feminine traits over time: A meta-analysis. Sex Roles. 1997;36:305–325. [Google Scholar]

- Whorley M, Addis ME. Ten years of research on the psychology of men and masculinity in the United States: Methodological trends and critique. Sex Roles. 2006;55:649–658. [Google Scholar]

- Wong YJ, Steinfeldt JA, Speight QL, Hickman SJ. Content analysis of psychology of men masculinity (2000–2008) Psychology of Men and Masculinity. 2010;11:170–181. [Google Scholar]

- Young AM, Morales M, McCabe SE, Boyd CJ, D’Arcy H. Drinking like a guy: Frequent binge drinking among undergraduate women. Substance Use & Misuse. 2005;40:241–267. doi: 10.1081/ja-200048464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]