Abstract

Background

Psychosis prevention and early intervention efforts in schizophrenia have focused increasingly on sub-threshold psychotic symptoms in adolescents and young adults. Although many youth report symptom onset prior to adolescence, the childhood incidence of prodromal-level symptoms in those with schizophrenia or related psychoses is largely unknown.

Methods

This study reports on the retrospective recall of prodromal-level symptoms from 40 participants in a first-episode of schizophrenia (FES) and 40 participants at “clinical high risk” (CHR) for psychosis. Onset of positive and non-specific symptoms was captured using the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes. Frequencies are reported according to onset during childhood (prior to age 13), adolescence (13–17), or adulthood (18 +).

Results

Childhood-onset of attenuated psychotic symptoms was not rare. At least 11% of FES and 23% of CHR reported specific recall of childhood-onset of unusual or delusional ideas, suspiciousness, or perceptual abnormalities. Most recalled experiencing non-specific symptoms prior to positive symptoms. CHR and FES did not differ significantly in the timing of positive and non-specific symptom onset. Other than being younger at assessment, those with childhood onset did not differ demographically from those with later onset.

Conclusion

Childhood-onset of initial psychotic-like symptoms may be more common than previous research has suggested. Improved characterization of these symptoms and a focus on their predictive value for subsequent schizophrenia and other major psychoses are needed to facilitate screening of children presenting with attenuated psychotic symptoms. Accurate detection of prodromal symptoms in children might facilitate even earlier intervention and the potential to alter pre-illness trajectories.

Keywords: Child, Psychosis, Psychotic-like, SIPS, Prodrome, Early onset

1. Introduction

Schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders are serious disorders that can lead to long-term disability, particularly if untreated (Keshavan et al., 2003; Marshall et al., 2005; Frazier et al., 2007). Over the past 50 years, significant research effort has focused on the early detection of emerging psychosis in order to facilitate the identification of etiological mechanisms and earlier intervention. The examination of familial risk, based on presumed genetic contribution to psychotic disorders and accompanying neurodevelopmental markers, has made important progress (Keshavan et al., 2005). In recent years, efforts have expanded to consider clinical and behavioral high risk as well as familial risk, determined through symptom-based screening instruments such as the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes (SIPS, Miller et al., 1999; McGlashan et al., 2001). These instruments query the onset and severity of newly emerging or worsening symptoms that may suggest a possible prodrome to, or more conservatively “clinical high risk” (CHR) for, a psychotic disorder.

Most primary psychotic disorders onset in late adolescence and early adulthood, with peak onset between ages 15 to 25 in males and 20 to 29 in females (Castle et al., 1993; Häfner et al., 1993). Since the prodromal period is thought to precede illness onset by 1 to 6 years (Yung and McGorry, 1996; Häfner et al., 1998; Köhn et al., 2004), screening measures for identification of prodromal symptoms have been developed primarily for adolescents and young adults. The predictive validity of attenuated psychotic symptoms in younger cohorts has yet to be determined. Given the developmental normalcy of magical thinking, grandiose and fantastical beliefs, concrete and more loosely organized thinking in young children, and the lower frequency of truly psychotic thinking, child responses to adolescent and adult screening instruments should be interpreted with caution (e.g., Woolley et al., 2004; Bartels-Velthuis et al., 2011). Poorly worded questions that exceed a child’s comprehension can result in false positives (Breslau, 1987). That said, even carefully conducted screening and interviews have yielded high frequencies of psychotic-like experiences in children.

Indeed, Laurens et al. (2012) found that in a London community sample of 8000 children ages 9–11, almost two-thirds endorsed at least one “psychotic-like experience” (PLE). In a study by Yoshizumi et al. (2004), 21% of a Japanese general population sample of children ages 11–12 experienced hallucinations. Subgroups that experience PLEs in general adult populations share biological and environmental risk factors with schizophrenia (Kelleher et al., 2011a), suggesting a continuum of psychosis in the general population (van Os et al., 2008). Subclinical auditory hallucinations in childhood appear to be transitory in most cases, but similarly to PLEs in adults, correlate with developmental and behavioral problems, hinting that such a continuum may also be present in youth populations (Hlastala and McClellan, 2005; Bartels-Velthuis et al., 2010, 2011). Thus, accumulating evidence suggests that PLEs may be more common in childhood than previously recognized. Importantly, prevalence of PLEs does not equate with prevalence of prodromal syndromes. There is poor reliability between PLEs and prodromal syndromes identified through structured clinical interview with the SIPS and much lower prevalence rates of CHR syndromes relative to PLEs in both adults and children (Kelleher et al., 2011a, 2011b; Schultze-Lutter et al., 2013, 2014).

Childhood-onset schizophrenia is exceedingly rare, with an estimated prevalence rate of 1.8/10,000 (Häfner and Nowotny, 1995). Yet genetic, neuroanatomical, cognitive, motor, and social abnormalities during childhood have been repeatedly associated with adult onset of schizophrenia (Jones et al., 1994; Marenco and Weinberger, 2000; Rapoport et al., 2005; Woodberry et al., 2008; Thermenos et al., 2013). In retrospective research of the precursors to schizophrenia, Häfner et al. (1998) found that negative symptoms preceded positive symptoms in 70% of adult-onset cases. However, these early “premorbid” and “prodromal” abnormalities and symptom patterns tend to be nonspecific, associated with risk for mood disorders like depression or bipolar disorder as well as psychosis (Cannon et al., 1997; van Os et al., 1997). A better understanding of the predictive value of psychotic-like experiences (PLEs) during childhood may improve the specificity of risk identification in childhood cohorts and support earlier intervention efforts.

One strategy for understanding the potential implications of psychotic-like experiences in children is to identify the degree to which individuals with clinically significant psychotic-like symptoms or psychotic disorders report a childhood onset of these symptoms. Thus, the purpose of the current study was to identify the prevalence and pattern of prodromal-level symptom onset in childhood as reported by adolescents and adults either in a first episode of schizophrenia (FES) or with a CHR syndrome. Although we explored differences in childhood symptom onset between these two groups, the overall goal was to characterize childhood symptom onset in both groups to inform screening and early intervention efforts. To our knowledge, no previous studies have used the same method to query symptom onset in both groups.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

The study sample was recruited for the Boston Center for Intervention Development and Applied Research (CIDAR) study entitled, “Vulnerability to Progression in Schizophrenia” (www.bostoncidar.org). Individuals ages 13–45 in a first episode of schizophrenia (FES, including schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or schizophreniform disorder) or persons ages 13–35 meeting criteria for CHR were recruited from area hospitals, outpatient treatment settings, and the metropolitan Boston community through advertisements, formal outreach presentations, and word of mouth. Exclusion criteria included sensory-motor handicaps, neurological disorders, medical illnesses that significantly impair neurocognitive function, intellectual disability, education less than 5th grade if under 18 or less than 9th grade if 18 or older, lack of English fluency, DSM-IV-TR substance abuse in the past month or substance dependence, excluding nicotine, in the past 3 months, current suicide risk, and a history of electroconvulsive therapy within the prior 5 years.

CIDAR recruited a total of 44 FES and 45 CHR participants. Of these, we excluded from these analyses one CHR and four FES due to missing SIPS data, one CHR (from the CHR sample only) who converted to schizophrenia and was thus included in the FES sample, and three CHR who had no reported attenuated positive symptom onset (but were included in the CIDAR study on the basis of a presumed negative symptom syndrome or genetic risk and decline of functioning). Thus 40 CHR and 40 FES were included in these analyses. All participants provided written informed consent (or assent and parental consent in the case of minors). The institutional review boards at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Cambridge Health Alliance, Harvard Medical School, Massachusetts General Hospital, the Veteran Affairs Boston Healthcare System, Brockton campus, and Brigham and Women’s Hospital approved the study.

2.2. Clinical measures and procedures

FES status and clinical diagnoses for both groups were determined by diagnostic consensus based on a clinical interview with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM IV-TR (SCID, Research Version, First et al., 2002) and available medical records. Prodromal symptoms and symptom onset were assessed with the Structured Interview of Prodromal Syndromes (SIPS; Miller et al., 1999; McGlashan et al., 2001; see von Hohenberg et al., 2013 for details on CHR criteria used in the CIDAR study). All clinical interviewers were trained on the SIPS by Yale University trainers (Drs. Tandy Miller and/or Barbara Walsh), and had to achieve accurate identification of CHR status for two videotaped interviews. Final determination of CHR status was determined by diagnostic consensus based on the Criteria of Prodromal Syndromes (COPS).

For inclusion in these analyses, participants had to provide sufficient recall of positive (attenuated psychotic) and nonspecific (negative, disorganized, or general) symptom onset via the 19 item SIPS (see Supplemental Table 1). For CHR participants the SIPS was the primary clinical interview for determining both eligibility and onset of PLEs. For FES participants the SIPS was a secondary interview, eliciting retrospective account of the onset of prodromal-level symptoms both for symptoms that had subsequently reached a psychotic level and for symptoms currently experienced at a “prodromal-level.” Based on the difficulty eliciting retrospective self-report of symptom onset for which acutely psychotic patients might have little or no insight (e.g., P3 grandiosity and P5 disorganized speech), the CIDAR study decided to query only nine of the nineteen symptoms of the SIPS Version 4.0 in FES patients (see Supplemental Table 1). Only participants with data on at least 8 of these 9 symptoms, including an estimated onset date for at least one symptom in each symptom group (positive, nonspecific) reported to be in the prodromal range, were included.

Parental socioeconomic status was determined by the Hollingshead scale (Hollingshead, 1975), using occupational and income data from both parents whenever possible. The Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI, Wechsler, 1999) and the Wide Range Achievement Test-4 (WRAT4, Wilkinson and Robertson, 2006) Word Reading subtest were administered to all participants by trained research assistants, as part of a comprehensive neuropsychological battery. Similarly, two measures of functioning, the Global Functioning: Social and Role scales (Cornblatt et al., 2007) were administered to all participants by clinicians trained on these measures by the instrument developers.

2.3. Establishing age of onset

Consistent with standard administration of the SIPS, participants were asked to identify or estimate the date of onset of any symptom (positive or nonspecific) endorsed at a putatively prodromal level (rating ≥ 3). Childhood-onset was defined as onset prior to age 13. Adolescent onset was defined by onset between ages 13–17. Adult onset was defined as onset at or after age 18. Onsets that could not be clarified beyond, “as long as I can remember” or “my entire life” were coded as “Lifetime” and, when included in analyses, included as “childhood-onset.” Clinicians documented the onset as “could not be determined” when participants could not provide a reliable estimate. Hospitalization, prior assessment records, or parental reports were sometimes requested for diagnostic clarification. In a few cases, information from these sources was incorporated in estimating the developmental period of symptom onset. To account for the quality of data available, we reported the frequency of childhood-onset of positive symptoms separately 1) using only symptoms queried in both groups for which estimated onset dates were available, 2) also including symptoms queried in both groups and reported as present during the person’s entire “lifetime,” and 3) also including onset of grandiosity and disorganized communication (for CHR and one FES for whom the latter was the only positive symptom) and onset of acute psychosis for two FES with no preceding period of attenuated positive symptoms (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Frequency of initial positive symptom onset by age.

| Based on onset date (39 CHR, 35 FES) | Including “lifetime” onset (39 CHR, 37 FES) | Based on all available data (40 CHR, 40 FES) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHR | Childhood | 9 (23.1%) | 11 (28.2%) | 14 (35.0%) |

| Adolescence | 15 (38.5%) | 14 (35.9%) | 14 (35.0%) | |

| Adulthood | 15 (38.5%) | 14 (35.9%) | 12 (30.0%) | |

| FES | Childhood | 4 (11.4%) | 7(18.9%) | 7 (17.5%) |

| Adolescence | 11 (31.4%) | 10 (27.0%) | 12 (30.0%) | |

| Adulthood | 20 (57.1%) | 20 (54.1%) | 21 (52.5%) | |

| Chi-square | 3.045, p = 0.218 | 2.564, p = 0.278 | 4.942, p = 0.085 |

CHR = clinical high risk; FES = first episode schizophrenia. Counts for first two columns are based only on the 3 positive symptoms consistently queried in both groups: unusual thought content (P1), suspiciousness/persecutory ideas (P2), and perceptual abnormalities (P4); based on onset date: count based only on symptoms for which a date of onset could be estimated; including “lifetime” onset: counts include P1, P2, and P4 onsets reported as “Lifetime” or “As long as I can remember” as childhood-onsets; based on all available data: counts include grandiosity (P3) and disorganized communication (P5) onset data for CHR, age of onset of fully psychotic symptoms in the case of FES reporting no period of attenuated positive symptoms/prodrome, and one FES reporting the only positive symptom to be disorganized speech (P5) that onset in adulthood. There were no significant group differences in distributions by developmental period.

2.4. Statistical analyses

We conducted data analyses in SPSS version 18. We tested between group differences of parametric continuous data with independent samples t tests and repeated measures ANOVAs and repeated the ANOVAs covarying for age, given group differences. We tested between group differences of non-parametric, ordinal, or categorical data with Chi-square, Fisher’s exact, and Mann-Whitney U tests as appropriate.

3. Results

3.1. Sample characteristics

As is shown in Table 1, both FES and CHR samples were racially diverse (37–45% non-Caucasian), with a slightly higher proportion of males, and estimated IQon the higher end of the average range. On average, participants had at least a high school education. Except for age and percent Hispanic/Latino (the FES sample was older, as expected, with a higher percentage of Hispanic participants), groups did not differ significantly on demographic variables.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics.

| CHR (n = 40)

|

FES (n = 40)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Test statistic | p | |

| Age | 19.8 (3.8) | 21.9 (4.5) | t(48) = −2.25 | 0.03 |

| Years of education | 12.5 (2.8) | 13.2 (2.6) | t(78) = 1.13 | 0.26 |

| WASI | 113.4 (14.8) | 109.8 (12.9) | t(78) = 1.09 | 0.28 |

| WRAT-4 reading | 110.2 (16.5) | 110.7 (16.6) | t(78) = −0.13 | 0.90 |

| n (%) | n (%) | Test statistic | p | |

|

| ||||

| Male | 21 (52) | 27 (68) | χ2(1) = 1.88 | 0.17 |

| Caucasian | 22 (55) | 25 (63) | χ2(1) = 0.46 | 0.50 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 2 (5) | 8 (20) | FET = 0.09 | 0.04 |

| Median, mean (SD) |

Median, mean (SD) |

|||

|

| ||||

| PSES | 2, 2.10 (1.03) | 2, 2.42 (1.13) | U = 664 | 0.17 |

CHR = clinical high risk; FES = first episode schizophrenia; WASI = Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (current IQ estimate based on Vocabulary and Block Design subtests); WRAT-4 = Wide Range Achievement Test-4 (premorbid IQ estimate based on Reading subtest); PSES = parental socioeconomic status, Hollingshead score (1–5 scale, 1 highest); FET = Fisher’s exact test; U = Mann–Whitney U test. Tests significant at p < 0.05 are in bold. Groups did not differ on education or IQ estimate even when age was included as a covariate.

FES participants met DSM-IV-TR criteria for schizophreniform disorder (n = 4, 10%), and schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type (n = 5, 13%) and depressed type (n = 9, 23%), and schizophrenia, disorganized type (n = 2, 5%), paranoid type (n = 11, 28%), and undifferentiated type (n = 9, 23%). Thirty-six (90%) of CHR participants met criteria for at least one DSM-IV-TR Axis I diagnosis, with many meeting criteria for multiple comorbid Axis I disorders. These included anxiety (n = 22, 55%), depressive (n = 16, 40%), behavioral (n = 9, 23%), bipolar (n = 9, 23%), developmental (n = 2, 5%), eating (n = 2, 5%), pain, (n = 1, 3%), and dissociative disorders (n = 1, 3%).

3.2. Frequency of childhood-onset of attenuated psychotic symptoms

Participant recall in response to SIPS queries suggested that childhood-onset of attenuated psychotic symptoms was not rare (see Table 2). Using all available data, nearly one-fifth of FES participants and over one-third of CHR identified initial onset of attenuated positive symptoms in childhood. Even excluding symptoms that people reported experiencing as long as they could remember (“lifetime” onset), 11% of FES and 23% of CHR reported childhood-onset of positive symptoms. The two groups did not differ significantly in rates of childhood-onset (χ2(1) = 1.03, p = 0.23, including “lifetime”; χ2(1) = 1.87, p = 0.14, excluding “lifetime”).

3.3. First symptoms recalled

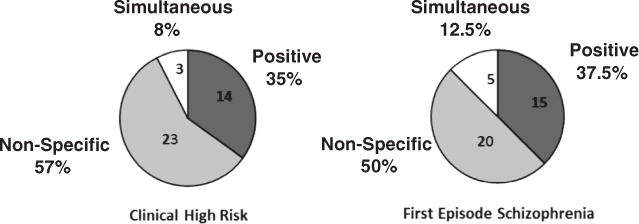

We examined whether participants recalled first experiencing positive or non-specific symptoms (see Fig. 1). Overall, more individuals identified experiencing non-specific symptoms (negative, disorganized, or general symptoms) before positive symptoms (unusual thought content, suspiciousness, perceptual abnormalities) in both groups. A few identified simultaneous onset of positive and non-specific symptoms (see also Supplemental Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Initial symptom onset. Number and percent of each sample for whom the indicated symptom type was experienced first. Only the 9 SIPS symptoms are included (when all19 symptoms are included, for CHR participants only, CHR percentages change to 55% non-specific and 10% simultaneous.).

3.4. Timing of onset of initial symptoms including non-specific symptoms

When age of onset of both positive and non-specific symptoms was considered, CHR and FES groups reported significantly different rates of first symptom onset by developmental period (see Table 3). Similar numbers of CHR participants identified childhood-onset as adolescent-and adulthood-onset, but with nearly half identifying childhood-onset of at least one symptom and a third or less reporting first symptom onset in adulthood. By contrast, nearly half of FES participants reported adult onset of positive and non-specific symptoms, although over a third of FES identified childhood-onset of at least one symptom.

Table 3.

Timing of initial positive and non-specific symptom onset.

| Positive symptoms (39 CHR, 37 FES) | Non-specific symptoms (38 CHR, 37 FES) | First symptom (either) (40 CHR, 40 FES) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHR | Childhood | 11 (28.2%) | 14 (38.9%) | 19 (47.5%) |

| Adolescence | 14 (35.9%) | 13 (36.1%) | 14 (35.0%) | |

| Adulthood | 14 (35.9%) | 9 (25.0%) | 7 (17.5%) | |

| FES | Childhood | 7(18.9%) | 13 (35.1%) | 15 (37.5%) |

| Adolescence | 10 (27.0%) | 8 (21.6%) | 8 (20.0%) | |

| Adulthood | 20 (54.1%) | 16 (43.2%) | 17 (42.5%) | |

| Chi-Square | 2.564, p = 0.278 | 3.174, p = 0.204 | 6.274, p = 0.043 |

CHR = clinical high risk; FES = first episode schizophrenia. Counts represent the frequency of participants for whom the given symptom type was reported to have onset within the specified developmental stage (counting only 9 core SIPS symptoms for the first two columns and in column 3, including all 19 symptoms for CHR and acute and P5 onset for FES). “Lifetime” onsets counted as childhood for all columns. Twenty-six (65%) of FES and 20(50%) of CHR reported positive and non-specific symptom onsets within the same developmental period. Differences in distributions by group of p < 0.05 are in bold.

3.5. Positive symptom onset by specific symptom

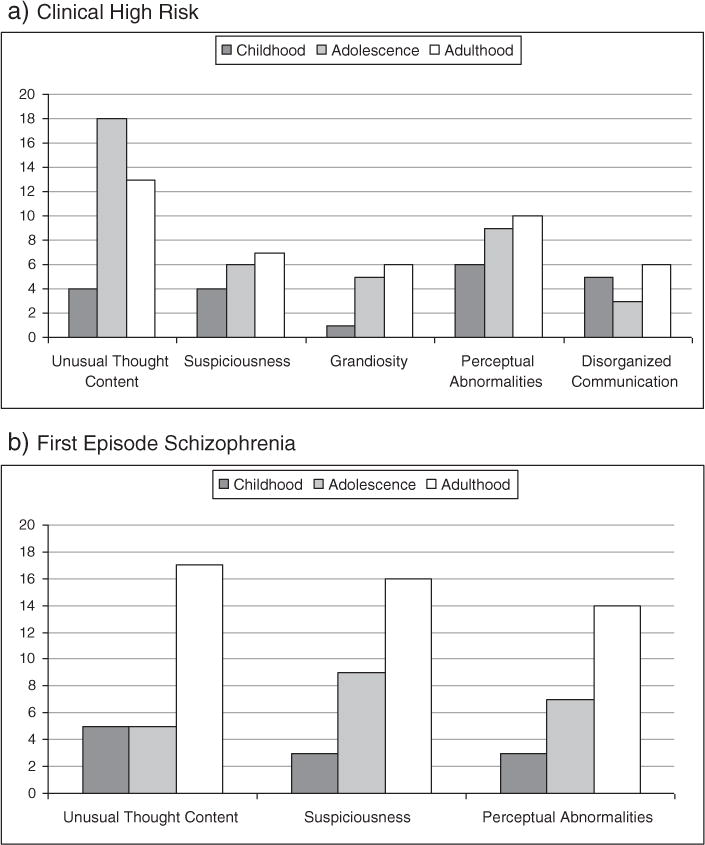

Some childhood-onset was reported for all positive (P) symptoms, with the frequencies of specific P symptom onset by developmental period shown in Fig. 2. There was no evidence that childhood-onset was specific to one type of positive symptom (e.g., hallucinations). Both groups reported the highest frequency of P symptom onset in adulthood, with the exception of unusual thought content (P1) in CHR. However, there were no statistically significant differences by group or symptom in developmental period of onset. Childhood-onset of grandiosity (P3) was reported by only one CHR individual.

Fig. 2.

Frequency of onset by specific positive symptom and age group. Individuals are counted multiple times if they endorsed multiple P symptoms. “Lifetime” onset was counted as childhood-onset. Groups did not differ significantly in developmental period of onset for any P symptom.

3.6. Demographics of childhood vs. later onset of positive symptoms

Overall, individuals reporting childhood-onset of positive symptoms did not differ significantly on gender, race, ethnicity, social, role, or global functioning, or estimated IQ (Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence, Wechsler, 1999, or single word reading measured by the Wide Range Achievement Test 4, Word Reading, Wilkinson and Robertson, 2006) from those who reported later onset. However, those with childhood onset of positive symptoms were significantly younger at the time of assessment (t = 2.02, p = 0.047) and had completed less education (t = 2.07, p = 0.042). The difference in age was not significant for either CHR or FES group alone, although the CHR group showed the strongest trend for younger age in those reporting childhood positive symptom onset. CHR reporting childhood-onset based on all 5 positive symptoms were significantly younger than those reporting later onset (t = 2.45, p = 0.019). This group was also predominantly male (11 of 14, χ2(1) = 5.87, p = 0.015) and had higher total positive symptom scores on the SIPS (13.9 vs. 11.5, F[1,39] = 4.31, p = 0.045). The FES participants with childhood-onset differed from FES with later onset only in Global Assessment of Functioning scores (40.7 vs. 51.3, respectively, F[1,37] = 4.91, p = 0.033).

4. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine the frequency of childhood-onset of attenuated psychotic symptoms in adolescents and adults identified with FES or CHR syndromes. In contrast to a significant literature suggesting that childhood-onset of psychotic and psychotic-like symptoms is rare even in schizophrenia samples (e.g., Thomsen, 1996), 11–19% of the FES sample and 23–35% of the CHR sample reported childhood-onset of attenuated psychotic symptoms. These higher rates are more consistent with the emerging literature from recent epidemiological and longitudinal birth cohort studies that suggest that PLEs may not only be relatively common in children ages 11–13, but that PLEs reported at age 11 signal substantially increased risk of schizophreniform disorder (and not mood disorders) at age 26 (Poulton et al., 2000; Kelleher et al., 2011a, 2011b). Whereas the rates of childhood-onset of prodromal-level psychotic symptoms reported by FES may be more directly relevant to understanding precursors specific to schizophrenia than those reported by CHR, these latter rates support the association of attenuated psychotic symptoms in childhood with increased risk for a psychotic disorder, including non-schizophrenia psychoses and schizophrenia spectrum disorders.

The pattern of positive relative to non-specific symptom onset is also informative in understanding pathways to schizophrenia and psychosis more broadly. Although roughly half of both FES and CHR participants reported the onset of non-specific symptoms prior to the onset of positive symptoms, another half reported onset of positive symptoms either prior to or simultaneously with the onset of non-specific symptoms. This frequency appears to be higher than in prior reports (e.g., Häfner et al., 1998). The difference may reflect differences in sample selection and diagnostic criteria, the type of symptom queries (e.g., SIPS probes used in this study are designed to elicit prodromal as well as psychotic symptoms), and/or the degree to which family observations were solicited and included in estimating onset (these were systematically solicited in the Häfner study, but not in this study). Self-report of internal states is likely to differ from observable behavior or inferred changes for a number of reasons, including the degree of participant self-understanding and/or self-disclosure, the quality of family observation, and the quality and reliability of both participant and family recall.

For decades, clinical case report and research into the etiology of schizophrenia have identified a number of warning signs already evident during childhood, long before the onset of acute psychosis (e.g., Sullivan, 1927; Alaghband-Rad et al., 1995; Catts et al., 2013; Seidman et al., 2013). Yet the fact that these early signs have been largely non-specific to psychosis outcomes has limited their utility for prospectively identifying children at highest risk for serious mental illness. The extent of attenuated positive symptom onset during childhood associated with later schizophrenia raises the possibility of improved childhood detection, and with it the possibility for enhanced and timelier protective interventions. Research highlighting the long delays between psychosis onset and treatment, the association of delays to poorer outcome, and the potential of earlier intervention to improve outcomes is motivating early identification efforts and service system reforms worldwide (McGorry et al., 2003; Frazier et al., 2007; Lloyd-Evans et al., 2011; Fusar-Poli et al., 2012). Of course, additional prospective and retrospective research studies are needed to confirm these findings and their relevance to these efforts.

The findings reported here, in conjunction with research suggesting that childhood psychotic symptoms may be both heritable and associated with non-specific problems typical of psychotic illnesses (Polanczyk et al., 2010), support the need to expand psychosis risk assessment to children under the age of 13 (e.g., Kelleher et al., 2011a; Fux et al., 2013). Based on the age distributions of initial positive symptom onset (see Supplemental Fig. 1), screening children ages 10–12 might be particularly fruitful. In addition to specialized psychosis risk screening, standard childhood behavior screening instruments might be improved by including items that capture these experiences. Greater clarification of population base rates and the predictive values of different symptoms and symptom combinations will be needed to balance the benefits and risks of such an effort.

For instance, recent studies of children in Ireland and Greater London found that children’s questionnaire endorsement of hallucinations (e.g., “yes, definitely” to the question “Have you ever heard voices or sounds that no one else can hear?”) was associated most closely with a latent psychosis construct, and had the highest predictive power for psychotic-like symptoms on interview (Kelleher et al., 2011a; Laurens et al., 2012). Yet, the retrospective report of symptoms by FES participants in the current study suggests that their childhood experience of attenuated psychotic symptoms was not dominated by hallucinatory experiences; delusional and persecutory ideas were just as common. The specificity of queries (e.g., probing a wide enough range of delusional ideas), varying capacities for self-reflection, particularly with age, and the differences between prospective and retrospective judgments of the uniqueness of one’s experience are all likely to play a role in evaluating the significance and predictive value of symptom reports.

4.1. Limitations

The primary limitation of this study is its reliance on retrospective self-report, with its well-known vulnerability to low reliability and validity and the influence of current mood and contextual factors (Brewin et al., 1993; Hardt and Rutter, 2004). It is worth noting, however, that studies of retrospective recall in women with schizophrenia found a bias toward under- rather than over-reporting of past events (obstetric complications, Buka et al., 2000), suggesting caution in assuming that self-reports err in the direction of over-reporting. Moreover, there is evidence that lack of reliability of retrospective self-reports in the context of psychopathology has been exaggerated (Brewin et al., 1993). Importantly, self-report remains the only measure of internal experiences such as mild delusional beliefs or odd perceptual experiences.

Another limitation is the lack of established reliability or validity in the use of the SIPS for eliciting retrospective recall of prodromal symptoms in a FES sample. Gauging when a symptom reached a prodromal level is particularly challenging with individuals who have limited insight into their symptoms, both current and past. This challenge also contributes to a significant amount of missing data, including dates that “could not be determined,” and symptoms that were queried for CHR but not FES participants. Although CHR and FES counts were compared only for symptoms queried in both samples, the lack of data on the onset of some symptoms, such as grandiosity and disorganized communication, in FES may contribute to an underestimate of childhood symptom onset in this sample. The fact that younger participants reported higher rates of childhood psychotic-like symptoms might simply reflect an association between earlier symptom onset with earlier detection and referral. It might also speak to easier recall of childhood in adolescents than adults (e.g., Rubin and Schulkind, 1997) or reflect higher levels of insight into the nature of their experiences. Alternatively, childhood onset of positive symptoms may be a more common precursor to non-schizophrenia psychosis than schizophrenia, and thus be more frequent in the younger and more diagnostically inclusive CHR sample than the FES sample. Methodologically sound longitudinal studies obtaining both prospective and retrospective reports of childhood PLEs are needed to better clarify the relationship between symptom onset, help-seeking, referral patterns, and diagnostic and functional outcomes.

Although clinicians took available parental observations and medical record reports into account in estimating symptom onsets, this was not conducted in a systematic way or for all participants. To account for this, we reported the frequency of childhood-onset of positive symptoms separately according to three different methods of counting (see Methods and Table 2). Finally, without long-term follow-up data, the degree to which the CHR participants were clinically comparable to the FES participants during a prodromal phase is unknown.

4.2. Conclusion

The knowledge that a substantial minority of individuals with schizophrenia and enhanced risk for major psychotic disorders report childhood-onset of psychotic-like symptoms may prompt a pediatrician or school psychologist to seek specialized consultation for a 10 year old with mild but developmentally atypical delusional thinking or suspiciousness of others. More broadly, we hope this knowledge will prompt further development of psychosis-screening questions and strategies in children. Given the higher frequency in children than in adolescents and adults of at least some psychotic-like symptoms, attention and response to these symptoms will require sensitivity to a number of developmental issues. These include the role of cognitive and language development in the recognition and reporting of symptoms (e.g., Caplan et al., 2000), base rates of different symptoms in clinical and general populations at different ages, and the reliability and validity of different screening questions, self-report measures, and child and parent interviews for eliciting and distinguishing symptoms of concern from benign childhood experience. The ultimate goal is the development of age-appropriate interventions that maximize protective factors (e.g., stress-reduction) while minimizing stigma, side effects, hopelessness, and other potential negative consequences.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all subjects for their participation in the study. We also thank the clinical, research assistant, and data management staff from the Boston CIDAR study, including Ann Cousins, PhD, APRN, Michelle Friedman-Yakoobian, PhD, Janine Rodenhiser-Hill, PhD, Andréa Gnong-Granato, MSW, Lauren Gibson, EdM, Sarah Hornbach, BA, Julia Schutt, BA, Kristy Klein, PhD, Maria Hiraldo, PhD, Grace Francis, PhD, Corin Pilo, LMHC, Reka Szent-Imry, BA, Shannon Sorenson, BA, Grace Min, EdM, Alison Thomas, BA, Chelsea Wakeham, BA, Caitlin Bryant, BS, and Molly Franz, BA. Finally, we are grateful for the hard work of many research volunteers, including Zach Feder, Elizabeth Piazza, Julia Reading, Devin Donohoe, Sylvia Khromina, Alexandra Oldershaw, and Olivia Schanz.

Role of funding source

Funding was provided by Veterans Affairs Merit Awards to M.E.S. and R.W.M., Veterans Affairs Schizophrenia Center to R.W.M. and M.E.S., the National Institutes of Health (P50 MH 080272 to R.W.M.; UO1 MH081928 to L.J.S.), the Commonwealth Research Center of the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health (SCDMH82101008006 to L.J.S.), National Alliance for Research in Schizophrenia and Depression Distinguished Investigator Award to M.E.S., University of Massachusetts (IDDRC P30HD0004147 to J.A.F.), Clinical Translational Science Award (UL1RR025758) and General Clinical Research Center Grant (M01RR01032) from the National Center for Research Resources to Harvard University and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, the National Center for Research Resources (P41RR14075), and Shared Instrumentation Grants (1S10RR023401, 1S10RR019307, 1S10RR023043). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2014.05.017.

Contributors

R.W.M., L.J.S., R.M.G., M.E.S., J.M.G., and J.A.F. designed the CIDAR study. K.A.W. raised the questions addressed by this article and with R.A.S., and S.B.H. cleaned the data, conducted analyses, and wrote the first draft of the article. R.M.G., J.D.W., A.J.G., and K.A.W. provided the clinical training and supervision of staff and conducted many of the clinical assessments. All authors contributed to and have approved the final article.

Conflict of interest

J.A.F. has received research support from Glaxo Smith Kline, Pfizer, Inc., Neuren, Roche, and Seaside Therapeutics. She serves on a data safety monitoring board for a Forest Pharmaceuticals study. All other authors deny conflicts of interest in relation to the subject of this study.

References

- Alaghband-Rad J, Mckenna K, Gordon CT, Albus KE, Hamburger SD, Rumsey JM, Frazier JA, Lenane MC, Rapoport JL. Childhood-onset schizophrenia: the severity of premorbid course. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34:1273–1283. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199510000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels-Velthuis AA, Jenner JA, van de Willige G, van Os J, Wiersma D. Prevalence and correlates of auditory vocal hallucinations in middle childhood. BJP. 2010;196:41–46. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.065953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels-Velthuis AA, van de Willige G, Jenner JA, van Os J, Wiersma D. Course of auditory vocal hallucinations in childhood: 5-year follow-up study. BJP. 2011;199:296–302. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.086918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N. Inquiring about the bizarre: false positives in Diagnostic Interview Schedule Children (DISC) ascertainment of obsessions, compulsions, and psychotic symptoms. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1987;26:639–644. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198709000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin CR, Andrews B, Gotlib IH. Psychopathology and early experience: a reappraisal of retrospective reports. Psychol Bull. 1993;113:82–98. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.113.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buka SL, Goldstein JM, Seidman LJ, Tsuang MT. Maternal recall of pregnancy history: accuracy and bias in schizophrenia research. Schizophr Bull. 2000;26:335–350. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon M, Jones P, Gilvarry C, Rifkin L, McKenzie K, Foerster A, Murray RM. Premorbid social functioning in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: similarities and differences. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:1544–1550. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.11.1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan R, Guthrie D, Tang B, Komo S, Asarnow RF. Thought disorder in childhood schizophrenia: replication and update of concept. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:771–778. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200006000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castle DJ, Wessely S, Murray RM. Sex and schizophrenia: effects of diagnostic stringency, and associations with and premorbid variables. BJP. 1993;162:658–664. doi: 10.1192/bjp.162.5.658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catts VS, Fung SJ, Long LE, Joshi D, Vercammen A, Allen KM, Fillman SG, Rothmond DA, Sinclair D, Tiwari Y, Tsai SY, Weickert TW, Shannon Weickert C. Rethinking schizophrenia in the context of normal neurodevelopment. Front Cell Neurosci. 2013;7 doi: 10.3389/fncel.2013.00060. http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2013.00060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornblatt BA, Auther AM, Niendam T, Smith CW, Zinberg J, Bearden CE, Cannon TD. Preliminary findings for two new measures of social and role functioning in the prodromal phase of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:688–702. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition. Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Frazier JA, McClellan J, Findling RL, Vitiello B, Anderson R, Zablotsky B, Williams E, McNamara NK, Jackson JA, Ritz L, Hlastala SA, Pierson L, Varley JA, Puglia M, Maloney AE, Ambler D, Hunt-Harrison T, Hamer RM, Noyes N, Lieberman JA, Sikich L. Treatment of early-onset schizophrenia spectrum disorders (TEOSS): demographic and clinical characteristics. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46:979–988. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e31807083fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusar-Poli P, Bonoldi I, Yung AR, Borgwardt S, Kempton MJ, Valmaggia L, Barale F, Caverzasi E, McGuire P. Predicting psychosis: meta-analysis of transition outcomes in individuals at high clinical risk. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69:220–229. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fux L, Walger P, Schimmelmann BG, Schultze-Lutter F. The Schizophrenia Proneness Instrument, Child and Youth version (SPI-CY): practicability and discriminative validity. Schizophr Res. 2013;146:69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Häfner H, Nowotny B. Epidemiology of early-onset schizophrenia. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1995;245:80–92. doi: 10.1007/BF02190734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Häfner H, Maurer K, Loffler W, Riecher-Rossler A. The influence of age and sex on the onset and early course of schizophrenia. BJP. 1993;162:80–86. doi: 10.1192/bjp.162.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Häfner H, Maurer K, Löffler W, an der Heiden W, Munk-Jørgensen P, Hambrecht M, Riecher-Rössler A. The ABC Schizophrenia Study: a preliminary overview of the results. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1998;33:380–386. doi: 10.1007/s001270050069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardt J, Rutter M. Validity of adult retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences: review of the evidence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004;45:260–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hlastala SA, McClellan J. Phenomenology and diagnostic stability of youths with atypical psychotic symptoms. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2005;15:497–509. doi: 10.1089/cap.2005.15.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. Four Factor Index of Social Status. 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Jones P, Murray R, Jones P, Rodgers B, Marmot M. Child developmental risk factors for adult schizophrenia in the British 1946 birth cohort. Lancet. 1994;344:1398–1402. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90569-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher I, Harley M, Murtagh A, Cannon M. Are screening instruments valid for psychotic-like experiences? A validation study of screening questions for psychotic-like experiences using in-depth clinical interview. Schizophr Bull. 2011a;37:362–369. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher I, Murtagh A, Molloy C, Roddy S, Clarke MC, Harley M, Cannon M. Identification and characterization of prodromal risk syndromes in young adolescents in the community: a population-based clinical interview study. Schizophr Bull. 2011b;38:239–246. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshavan MS, Haas G, Miewald J, Montrose DM, Reddy R, Schooler NR, Sweeney JA. Prolonged untreated illness duration from prodromal onset predicts outcome in first episode psychoses. Schizophr Bull. 2003;29:757–769. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshavan MS, Diwadkar VA, Montrose DM, Rajarethinam R, Sweeney JA. Premorbid indicators and risk for schizophrenia: a selective review and update. Schizophr Res. 2005;79:45–57. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhn D, Niedersteberg A, Wieneke A, Bechdolf A, Pukrop R, Ruhrmann S, Schultze-Lutter F, Maier W, Klosterkötter J. Early course of illness in first episode schizophrenia with long duration of untreated illness — a comparative study. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr. 2004;72:88–92. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-812509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurens KR, Hobbs MJ, Sunderland M, Green MJ, Mould GL. Psychotic-like experiences in a community sample of 8000 children aged 9 to 11 years: an item response theory analysis. Psychol Med. 2012;1:1–10. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711002108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd-Evans B, Crosby M, Stockton S, Pilling S, Hobbs L, Hinton M, Johnson S. Initiatives to shorten duration of untreated psychosis: systematic review. BJP. 2011;198:256–263. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.075622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marenco S, Weinberger DR. The neurodevelopmental hypothesis of schizophrenia: following a trail of evidence from cradle to grave. Dev Psychopathol. 2000;12:501–527. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400003138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall M, Lewis S, Lockwood A, Drake R, Jones P, Croudace T. Association between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in cohorts of first-episode patients: a systematic review. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:975–983. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.9.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGlashan TH, Miller TJ, Woods SW, Rosen JL, Hoffman RE, Davidson L. Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes. PRIME Research Clinic, Yale School of Medicine; New Haven, CT: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- McGorry PD, Yung AR, Phillips LJ. The “close-in” or ultra high-risk model: a safe and effective strategy for research and clinical intervention in prepsychotic mental disorder. Schizophr Bull. 2003;29:771–790. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller TJ, McGlashan TH, Woods SW, Stein K, Driesen N, Corcoran CM, Davidson L. Symptom assessment in schizophrenic prodromal states. Psychiatry Q. 1999;70:273–287. doi: 10.1023/a:1022034115078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polanczyk G, Moffit TE, Arseneault L, Cannon M, Ambler A, Keefe RSE, et al. Etiological and clinical features of childhood psychotic symptoms: results from a birth cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:328–338. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulton R, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Cannon M, Murray R, Harrington H. Children’s self-reported psychotic symptoms and adult schizophreniform disorder: a 15-year longitudinal study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:1053–1058. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.11.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport JL, Addington AM, Frangou S, Psych MRC. The neurodevelopmental model of schizophrenia: update 2005. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10:434–449. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DC, Schulkind MD. The distribution of autobiographical memories across the lifespan. Mem Cogn. 1997;25:859–866. doi: 10.3758/bf03211330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultze-Lutter F, Michel C, Ruhrmann S, Schimmelmann BG. Prevalence and clinical significance of DSM-5-attenuated psychosis syndrome in adolescents and young adults in the general population: The Bern Epidemiological At-Risk (BEAR) study. Schizophr Bull. 2013 doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt171. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbt171 (sbt171) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Schultze-Lutter F, Renner F, Paruch J, Julkowski D, Klosterkötter J, Ruhrmann S. Self-reported psychotic-like experiences are a poor estimate of clinician-rated attenuated and frank delusions and hallucinations. Psychopathology. 2014;47:194–201. doi: 10.1159/000355554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidman LJ, Cherkerzian S, Goldstein JM, Agnew-Blais J, Tsuang MT, Buka SL. Neuropsychological performance and family history in children at age 7 who develop adult schizophrenia or pipolar psychosis in the New England family studies. Psychol Med. 2013;43:119–131. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712000773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan HS. The onset of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1927;84:105–134. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.6.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thermenos HW, Keshavan MS, Juelich RJ, Molokotos E, Whitfield-Gabrieli S, Brent BK, Makris N, Seidman LJ. A review of neuroimaging studies of young relatives of individuals with schizophrenia: a developmental perspective from schizotaxia to schizophrenia. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2013;162B:604–635. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen PH. Schizophrenia with childhood and adolescent onset — a nationwide register-based study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1996;94:187–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1996.tb09847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Os J, Jones P, Lewis G, Wadsworth M, Murray R. Developmental precursors of affective illness in a general population birth cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:625–631. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830190049005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Os J, Linscott RJ, Myin-Germeys I, Delespaul P, Krabbendam L. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the psychosis continuum: evidence for a psychosis proneness-persistence-impairment model of psychotic disorder. Psychol Med. 2008;39:179. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708003814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Hohenberg CC, Pasternak O, Kubicki M, Ballinger T, Vu MA, Swisher T, Green K, Giwerc M, Dahlben B, Goldstein JM, Woo TUW, Petryshen TL, Mesholam-Gately RI, Woodberry KA, Thermenos HW, Mulert C, McCarley RW, Seidman LJ, Shenton ME. White matter microstructure in individuals at clinical high risk of psychosis: a whole-brain diffusion tensor imaging study. Schizophr Bull. 2013 doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt079. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbt079 (sbt079) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI) Harcourt Assessment; San Antonio, TX: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson GS, Robertson GJ. Wide Range Achievement Test—Fourth Edition. Psychological Assessment Resources; Lutz, FL: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Woodberry KA, Giuliano AJ, Seidman LJ. Premorbid IQ in schizophrenia: a meta-analytic review. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:579–587. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07081242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolley JD, Boerger EA, Markman AB. A visit from the Candy Witch: factors influencing young children’s belief in a novel fantastical being. Dev Sci. 2004;7:456–468. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2004.00366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshizumi T, Murase S, Honjo S, Kaneko H, Murakami T. Hallucinatory experiences in a community sample of Japanese children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:1030–1036. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000126937.44875.6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yung AR, McGorry PD. The prodromal phase of first-episode psychosis: past and current conceptualizations. Schizophr Bull. 1996;22:353–370. doi: 10.1093/schbul/22.2.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.